Abstract

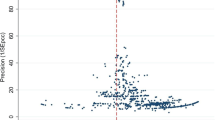

This paper examines whether autocracy is a gamble. Using robust variance tests and other analyses, we find that long-term growth varies more across autocracies than across democracies. This remains true even when richer countries are excluded from the sample. We also investigate channels, to see if the higher variance of growth outcomes across autocracies can be traced to a higher variance in investment ratios or productivity growth. Overall, the paper’s findings suggest that growth prospects are more uncertain for autocracies than democracies, and especially for closed autocracies. From the viewpoint of a domestic population, autocracy remains a gamble.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, for example, Sah (1991) or Gandhi (2008, pp. 139–140). Related research includes (Knutsen 2015) and Sylwester (2015). Earlier work by Gasiorowski (2000) found that democracies grow more slowly; results may conflict because the cross-section variance of outcomes depends on regime type, which is the hypothesis we consider in this paper. An alternative argument is that long-term democracy is what matters; see (Gerring et al. 2005) and (Persson and Tabellini 2009).

Note that, throughout the paper, we use the idea of an ‘autocratic gamble’ in this loose metaphorical sense, rather than as a well-defined decision problem for a specific set of decision-makers. In a similar spirit, Knutsen (2018) describes democracy as providing a ’safety net’ that makes the worst outcomes less likely.

This is based on the V-Dem classification of autocracies, discussed later in the paper. The importance of discriminating between types of regime was stressed by Gandhi (2008), Gleditsch and Ward (1997) and Vreeland (2008). In future work, it might be especially interesting to ask whether the variance of outcomes depends on the strength of parties; see Bizzarro et al. (2018).

It is possible that the number of decision-makers is smallest in closed autocracies, on average, but that is only a conjecture.

See Chapter XI of Aristotle’s Politics: a Treatise on Government.

The earlier empirical literature was inconclusive; see the meta-analysis in Doucouliagos and Ulubaşoğlu (2008).

We have also used classifications based on Polity V, Marshall et al. (2020). Those results, which are consistent with those reported here, are available on request.

Note that we are interested in the cross-section variance; we do not study growth rate volatility, but rather how distributions of long-term growth rates compare across different types of regime.

References

Acemoglu D, Naidu S, Restrepo P, Robinson JA (2019) Democracy does cause growth. J Polit Econ 127(1):47–100

Almeida H, Ferreira D (2002) Democracy and the variability of economic performance. Econ Polit 14:225–257

Anckar C, Fredriksson C (2019) Classifying political regimes 1800–2016: a typology and a new dataset. Eur Polit Sci 18:84–96

Anscombe FJ, Glynn WJ (1983) Distribution of the Kurtosis Statistic \(b_2\) for Normal Samples. Biometrika 70(1):227–234

Besley T, Kudamatsu M (2008) Making Autocracy Work. In: Helpman E (ed) Institutions and economic performance. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Bizzarro F, Gerring J, Knutsen CH, Hicken A, Bernhard M, Skaaning S-E, Coppedge M, Lindberg SI (2018) Party strength and economic growth. World Polit 70(2):275–320

Boix C, Miller M, Rosato S (2013) A complete data set of political regimes, 1800–2007. Comp Polit Stud 46(12):1523–1554

Box GEP (1953) Non-normality and tests on variances. Biometrika 40(3/4):318–335

Brown MB, Forsythe AB (1974) Robust tests for the equality of variances. J Am Stat Assoc 69(346):364–367

Cheibub JA, Gandhi J, Vreeland JR (2010) Democracy and dictatorship revisited. Public Choice 143:67–101

Collier D, Levitsky S (1997) Democracy with adjectives: conceptual innovation in comparative research. World Polit 49(3):430–451

Coppedge M, Gerring J, Knutsen CH, Lindberg SI, Teorell J, Altman D, Bernhard M, Fish MS, Glynn A, Hicken A, Lührmann A, Marquardt KL, McMann K, Paxton P, Pemstein D, Seim B, Sigman R, Skaaning S-E, Staton J, Cornell A, Gastaldi L, Gjerløw H, Mechkova V, von Römer J, Sundtröm A, Tzelgov E, Uberti L, Wang Y, Wig T, Ziblatt D (2020) V-Dem Codebook v10 Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project

D’Agostino RB, Belanger A, D’Agostino RB Jr (1990) A suggestion for using powerful and informative tests of normality. Am Stat 44(4):316–321

Diamond L (2002) Thinking about hybrid regimes. J Democr 13(2):21–35

Diamond L (2015) Facing up to the democratic recession. J Democracy 26(1):141–155

Doucouliagos H, Ulubaşoğlu MA (2008) Democracy and economic growth: a meta-analysis. Am J Polit Sci 52(1):61–83

Eberhardt M (2019) Democracy Does Cause Growth: Comment. CEPR discussion paper no. 13659

Fagiolo G, Napoletano M, Roventini A (2008) Are output growth-rate distributions fat-tailed? Some evidence from OECD countries. J Appl Econom 23:639–669

Feenstra RC, Inklaar R, Timmer MP (2015) The next generation of the Penn World Table. Am Econ Rev 105:3150–3182

Gandhi J (2008) Political institutions under dictatorship. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Gasiorowski MJ (2000) Democracy and macroeconomic performance in underdeveloped countries: an empirical analysis. Comp Polit Stud 33(3):319–349

Geddes B, Wright J, Frantz E (2014) Autocratic breakdown and regime transitions: A new data set. Perspect Polit 12(2):313–331

Gerring J, Bond P, Barndt WT, Moreno C (2005) Democracy and economic growth: a historical perspective. World Polit 57(3):323–364

Gerring J, Thacker SC, Alfaro R (2012) Democracy and human development. J Polit 74(1):1–17

Glaeser E, La Porta R, Lopez-de-Silanes F, Shleifer A (2004) Do institutions cause growth? J Econ Growth 9:271–303

Gleditsch KS, Ward MD (1997) Double take: a reexamination of democracy and autocracy in modern polities. J Conflict Resolut 41(3):361–383

Gründler K, Krieger T (2019) Should we care (more) about data aggregation? Evidence from the democracy-growth-nexus. CESifo Working Paper Series no. 7480, CESifo Group Munich

Haggard S, Kaufman RR (2016) Democratization during the third wave. Annu Rev Polit Sci 19:125–144

Jones BF, Olken BA (2005) Do leaders matter? National leadership and growth since World War II. Quart J Econ 120(3):835–864

Knutsen CH (2015) Why democracies outgrow autocracies in the long run: civil liberties, information flows and technological change. Kyklos 68:357–384

Knutsen CH (2018). Autocracy and variation in economic development outcomes. V-Dem Working Paper, 80

Levene H (1960) Robust tests for equality of variances. In: Olkin I, Ghurye SG, Hoeffding W, Madow WG, Mann HB (eds) Contributions to probability and statistics: essays in honor of Harold Hotelling. Stanford University Press, Stanford

Levitsky S, Way LA (2002) Elections without democracy: the rise of competitive authoritarianism. J Democracy 13(2):51–65

Luo Z, Przeworski A (2019) Why are the fastest growing countries autocracies? J Polit 81(2):663–669

Lührmann A, Tannenberg M, Lindberg SI (2018) Regimes of the World (RoW): opening new avenues for the comparative study of political regimes. Polit Govern 6(1):1–18

Markowski CA, Markowski EP (1990) Conditions for the effectiveness of a preliminary test of variance. Am Stat 44:322–326

Marshall MG, Gurr T, Jaggers K (2020). Polity V project. Political regime characteristics and transitions, 1800–2018. Dataset Users’ Manual

Olson M (1993) Dictatorship, democracy, and development. Am Polit Sci Rev 87(3):567–576

Paltseva E (2010) Autocracy, Democratization and the Resource Curse, Manuscript, Stockholm

Persson T, Tabellini G (2009) Democratic capital: the nexus of political and economic change. Am Econ J: Macroecon 1(2):88–126

Przeworski A, Alvarez ME, Cheibub JA, Limongi F (2000) Democracy and development: political institutions and well-being in the world, 1950–1990. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK

Rodrik D (1997) Democracy and Economic Performance. Manuscript, Harvard

Rodrik D (2008) One economics, many recipes: globalization, institutions, and economic growth. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Sah RK (1991) Fallibility in human organizations and political systems. J Econ Perspect 5(2):67–88

Sah RK, Stiglitz JE (1991) The quality of managers in centralized versus decentralized organizations. Quart J Econ 106(1):289–295

Schedler A (2002) Elections without democracy: the menu of manipulation. J Democracy 2:36–50

Shapiro SS, Wilk MB (1965) An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 52(3/4):591–611

Stigler SM (2010) The changing history of robustness. Am Stat 64(4):277–281

Treier S, Jackman S (2008) Democracy as a latent variable. Am J Polit Sci 52:201–217

Treisman D (2020) Democracy by mistake: how the errors of autocrats trigger transitions to freer government. Am Polit Sci Rev 114(3):792–810

Vreeland JR (2008) The effect of political regime on civil war: unpacking autocracy. J Conflict Resolut 52(3):401–425

Weede E (1996) Political regime type and variation in economic growth rates. Const Polit Econ 7:167–176

Wilson MC (2014) A discreet critique of discrete regime type data. Comp Polit Stud 47(5):689–714

Wilson MC, Wright J (2017) Autocratic legislatures and expropriation risk. Br J Polit Sci 47(1):1–17

Wright J (2008) Do authoritarian institutions constrain? How legislatures affect economic growth and investment. Am J Polit Sci 52:322–343

Acknowledgements

Corres. author: Fabio Monteforte. We are grateful to Paddy Carter, Adeel Malik, James Rockey, Nicolas Van de Sijpe and two anonymous referees for helpful comments, but the usual disclaimer applies. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

In this appendix, we report robust variance tests using a range of datasets on political regimes.

See Tables 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Monteforte, F., Temple, J.R.W. The autocratic gamble: evidence from robust variance tests. Econ Gov 21, 363–384 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-020-00245-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-020-00245-4