Abstract

Mood selection properties of desire verbs provide a rich source of evidence regarding the semantics of propositional attitudes. This paper approaches the topic by providing an analysis of crosslinguistic variation in the selection patterns of the desire verbs ‘want’ and ‘hope’, focusing on Spanish and French. There is no evidence that the meanings of ‘hope’ and ‘want’ differ between these languages, and yet in Spanish esperar ‘hope’ and querer ‘want’ both take subjunctive, while in French only vouloir ‘want’ selects subjunctive and espérer ‘hope’ strongly prefers the indicative. The inclination of ‘hope’ toward the indicative is manifest also in other Romance languages. Previous theories tie mood selection tightly to the verb’s modal backgrounds and do not anticipate such variation. We explain the consistency in mood selection with ‘want’ versus the variation with ‘hope’ in terms of two key ideas: (i) moods are modal operators that encode different degrees of modal necessity, and (ii) modal backgrounds can be manipulated by the grammar. In terms of (i), we argue, building on the comparison-based theory of mood, that the indicative is a strong necessity operator, while the subjunctive encodes a weaker necessity. Regarding (ii), we propose that two backgrounds may function as one under certain well-defined circumstances. Our proposal supports the decompositional approach to attitude verbs, where mood is responsible for the quantificational force traditionally attributed to the verb.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Verbal mood is not necessarily marked with verbal morphology; for example, the particle na in Greek is often considered a subjunctive marker. The term ‘mood’ is also applied to categories of sentences classified by the type of speech act they are conventionally associated with, categories like declarative, interrogative, and imperative. These are more precisely labeled as ‘sentence moods’, and are closely related to the more syntactic concept of clause types. See Portner (2018) for discussion of these notions and their relation to verbal moods.

In this paper, we focus on selected moods in French and Spanish. We do not discuss selected infinitives which substitute for a mood-marked clause when there is subject control, polarity subjunctives, or other non-selected subjunctives such as those triggered by ‘before’ and ‘if’. We also set aside uses of mood which are not attested in these languages, such as the reportative subjunctive of German. See Portner (2018) for an overview of these types and references to the literature on these phenomena.

Our description is based on work with a small number of native speaker informants, most of whom are professional linguists or language instructors. The target sentences were as described in the text, with ‘be happy’ as the embedded predicate, though other predicates were sometimes discussed over the course of an interview. The numbers of primary informants were as follows: French (3), Italian (3), Spanish (3), Catalan (2), Portuguese (3), Romanian (3). We also acquired additional Catalan data indirectly, as one of our primary informants consulted with other speakers in their network, and we asked additional speakers for judgments of the critical data in French described below. When we use the % symbol, this indicates a confirmed difference in judgment between speakers on the sentences tested. Because of the small number of consultants and their different backgrounds, we do not conclude that these differences reveal a dialect difference. Rather, these contrasts should be seen as potential targets for further study.

We have not taken into account sociolinguistic factors that might affect mood choice in language use, and we do not mean to imply (or rule out) a broader difference in dialect (Poplack 1992; Poplack et al. 2013, and Poplack et al. 2018 have conducted a valuable series of studies of the sociolinguistics of mood choice in Quebec French and in Romance more generally).

The speakers we consulted are from France; we have not examined varieties spoken in other parts of the world.

Specifically, the imperfect subjunctive (e.g., f\(\hat{u}\)t ‘be.subj.imperf’) is not productive with the speakers we consulted.

We have consulted speakers from Spain, Chile, and Venezuela. There is extensive dialectal variation in Spanish, so we would not rule out that other varieties would show different patterns.

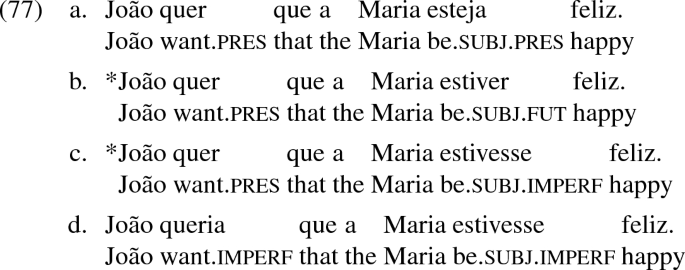

Though it is rejected by our primary consultants, present subjunctive under imperfect, as in (7d), has been reported to be possible in certain contexts for some speakers (Suñer and Padilla-Rivera 1987; Quer 1998). Its acceptability may also be subject to dialect variation (Sessarego 2010; Rio and Claudia 2014; Guajardo 1997).

Spanish has two conjugations of the imperfect, but we only show the ra form in the examples. Also note that while Spanish has a future subjunctive, it is obsolete. For simplicity, we only present examples with one of the ‘be’-verbs, estar. In some cases there appears to be an interaction between the inferences due to the choice of copula and the inferences generated by the tense and mood combinations. These interactions do not affect the pattern we show; the same moods are possible with either verb.

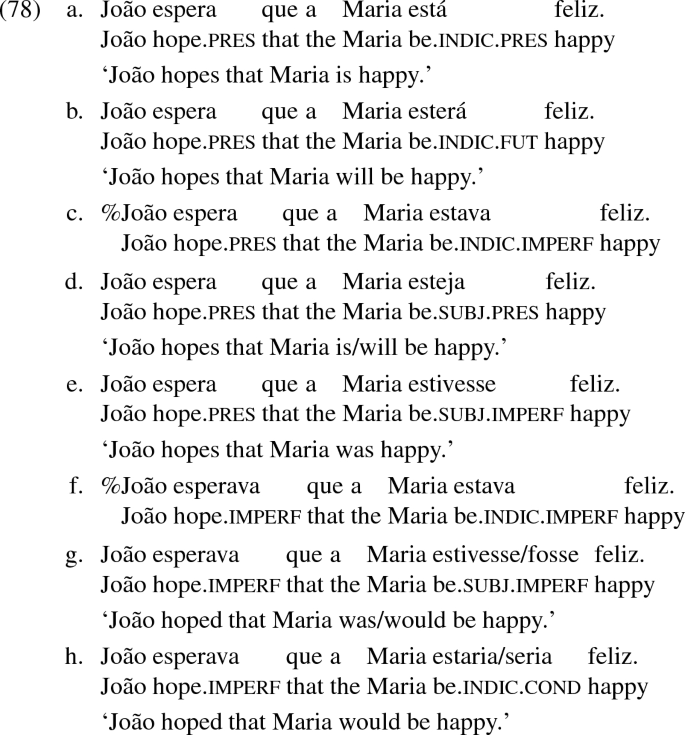

We occasionally find espero ‘I hope’ with future (indicative). While the parameters for allowing the future are unclear, from what we can tell, it typically (perhaps exclusively) happens with first person singular. This suggests that some kind of special pragmatics is involved, and we set it aside. We thank Tris Faulkner and Elena Herburger for discussing this point.

Esperar is ambiguous, with another meaning ‘expect’. In this meaning, it takes indicative (Villalta 2008). It is sometimes difficult to separate the two meanings (for example, ‘I hope/expect that you have done your homework’, spoken by parent to child).

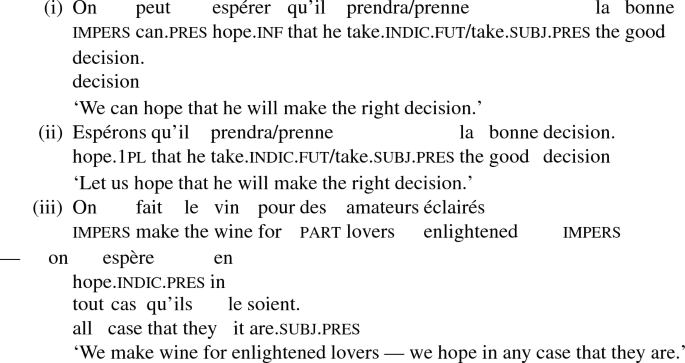

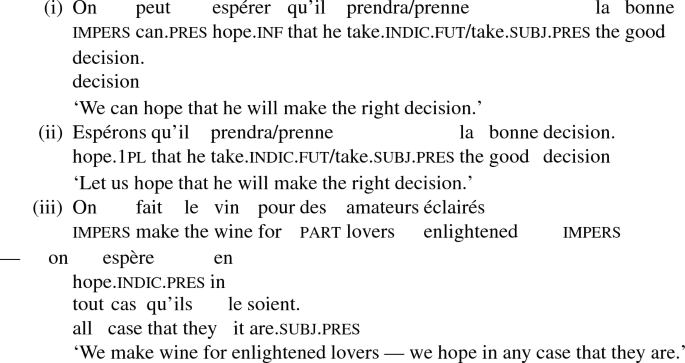

Godard (2012) points out the following examples of French ‘hope’ with subjunctive (p. 12):

We are not sure if these cases should count as examples of subjunctive with future-oriented ‘hope’ of the same sort as (5d). Examples (i)-(ii) are clearly future oriented, while (iii) is unclear. Godard describes them as cases in which the subjunctive is connected to the presence of additional material in the clause, in particular a possibility modal in (i), the exhortative in (ii), and the impersonal construction in (i) and (iii). Godard also notes that these examples convey reduced commitment on the part of the subject (p. 142), a point which connects to our ideas (see Sect. 4). We set this set of facts aside until further investigation can untangle what precisely is responsible for the subjunctive.

Farkas’s earlier work highlights the roles of several factors in mood selection, including assertiveness, epistemic commitment, truth in an individual’s ‘reality’, future-orientation and comparison (Farkas 1992). The central idea of this theory is that indicative is selected when a predicate is ‘extensional’ (in the sense that it entails that the mood-marked clause is true in the world of the reality of a designated individual). This part of her proposal lays the foundation for Giannakidou’s closely related analysis based on veridicality.

We use the term ‘premise semantics’ to refer to the Kratzerian framework with modal base and ordering source, and the term ‘similarity semantics’ for the counterfactual approach from Stalnaker and Heim. This terminology might be somewhat confusing, because the similarity approach can use a premise set to establish the buletic ordering, but the term ‘premise semantics’ is well established for Kratzer’s system (Lewis 1981). It’s possible our analysis could be recast in a simpler ordering semantics not based on premise sets, but we do not pursue this option here.

One could discuss the exact status of the diversity condition (for example, is it a presupposition or some other type of not-at-issue meaning? Does it come from the verb or the complement? Is it part of the modal semantics or independent?). Such issues are not our focus here, and we adopt the position of Heim and von Fintel that it is indeed a presupposition associated with the content of the verb.

We think of this modal force as a type of necessity, since it requires p to be entailed by a local maximum in the ordering.

It is felt that ‘John doesn’t want to buy the couch’ could be true on its own, if the modal base \(dox^+\) excludes worlds where he gets such a big discount. But when getting the discount is explicitly mentioned as in (17), the diversity condition requires that it be compatible with the modal base.

We follow previous work in suggesting a modal background for ‘say’ that is a reported common ground (Giorgi and Pianesi 1997; Farkas 2003). The simple proposal that the reported common ground entails p has problems, since we can report something as having been said even if it never is accepted into the common ground. A more accurate statement of the semantics might be the following: given a saying event e, the rpg is the common ground shared by the reported interlocutors just before e, plus what was proposed for addition to this background in e. We thank an anonymous reviewer for noting the need to clarify this point.

Matthewson (2010) argues that the St’át’imcets desire verb xát’min’ corresponds to ‘hope’ rather than ‘want’, and thus (following Portner 1997) involves universal quantification based on a single buletic background. She uses this to explain the fact that it does not take subjunctive. While as it stands her analysis depends on the problematical assumption that ‘hope’ has the semantics in (23), her broader approach may be compatible with the ideas developed in this paper. Specifically, one could build on our proposal for why French ‘hope’ takes indicative.

Recall that the statement that French ‘hope’ takes indicative is a simplification. As we develop our analysis in this section, we set aside the exceptions to concentrate on the broader pattern; we briefly return to the case of subjunctive under ‘hope’ in French in Sect. 3.4.

Anand and Hacquard’s analysis is given in terms of the similarity semantics rather than the premise semantics approach, so DES is not technically an ordering source. However, it plays the role in the similarity semantics which corresponds to an ordering source, and is associated with subjunctive in the similarity-based version of the comparison-based theory of mood.

The simpler condition \(\bigcap bul^c(s)\ne \emptyset \) would not work, because \(bul^c(s)\) could be consistent in itself, but not consistent with dox(s). For example, consider \(dox(s) = \{p\vee q, \lnot (p \wedge q)\}, bul^c(s) = \{p, q\}.\) With the simpler condition, local necessity predicts that the experiencer hopes p and that the experiencer hopes q.

Their formal analysis is somewhat more complicated because it is designed to capture the interaction between ‘hope’ and epistemic modals in its complement; specifically, their semantics of ‘hope’ implies that when \(\phi \) is a necessity statement \(\square \psi \), the doxastic assertion can only be true if \(\lnot \phi \) is incompatible with the attitude holder’s beliefs, thus conflicting with the presupposition. Since we are focusing on mood selection and not the distribution of epistemic modals, we will not present further details of their semantics for ‘hope’ here.

Thanks to Chloé Tahar both for help with the French data and for discussion.

It should be noted that the reading of ‘hope’ with the infinitive described below, while very common, does not always obtain. It can be cancelled in (35), for example with ‘I am really not interested in competition.’ We also note that the effect may be prominent to different degrees in different languages. In Hebrew, for example, the at-issue meaning of belief seems to require the addition of an adverb (be’emet ‘really’, preferably focused); this is true both with negation and in questions. As we show below, the availability of a belief meaning correlates with the type of complement ‘hope’ takes in a sentence. With finite clausal complements, Hebrew behaves just like English and French do in (36)-(37).

These are contexts that license the polarity subjunctive, so we expect subjunctive to be possible in the complement clause. (In fact, gagne is ambiguous as to its mood.) We have not yet investigated the meaning differences that arise from using subjunctive vs. (selected) indicative in contexts like these.

In our formal fragment, tense both assigns a temporal relation to the situation argument and introduces the world variable. We continue to leave the temporal relations of tense out of subsequent derivations.

The idea that modal quantification comes from the complement clause rather than the attitude verb has been pursued by Portner (1997), Kratzer (2006), and Moulton (2009), among others. In these earlier works, modal force is introduced in C, rather than by mood as we will propose. However, as stated in Appendix B, we assume that mood raises to C to take scope over the entire complement clause, and so our analysis can actually be seen as an extension of these earlier proposals.

To be technically precise, we need to provide explicit denotations of \(\theta _{indic}\) and \(\theta _{subj}\) which make clear what goes wrong when their first argument is a tuple of the wrong number of backgrounds. We give the official definitions in Appendix B.

Frank (1996) was the first to pursue the idea that modal backgrounds can be unified, as part of an argument that ordering sources are not a necessary component of modal semantics. Rubinstein (2012, (2014) uses unification of modal backgrounds to explain the difference between strong and weak necessity. In Sect. 4 we connect our analysis of mood with these proposals about modal semantics.

At this point (and in the formal system in Appendix B), the fact that the beliefs and desires associated with a wanting situation are not necessarily consistent is the reason that simplification fails. In Sect. 4, we will consider what may be a deeper reason for this failure.

There may of course be interesting historical reasons why the languages differ in the way they do. If so, this is completely consistent with our semantic description.

Quer (1998) and Giannakidou (2009) discuss interactions between tense and mood, and there is an extensive literature in syntax on tense-mood interaction focusing on sequence of tense and opacity (e.g., Suñer and Padilla-Rivera 1987). However, these works do not address the effects of temporal semantics on mood selection.

There are other syntactic patterns which can express these concepts, for example a nominal complement avoir l’intention que ‘have the intention that’ and a prepositional complement s’attendre à ce que ‘expect that’, but mood may be determined differently in these cases. Note that the noun espoir ‘hope’, while it allows the indicative, also allows the subjunctive even for those speakers who require indicative with the verb espérer.

-

(i)

Pierre a l’espoir que Marie sera/soit heureuse.

Pierre have the hope that Marie be.indic.fut/be.subj heureuse happy ‘Pierre has the hope that Marie will be happy.’

This indicates that mood with nouns works differently from with verbs. Thanks to Philippe Schlenker for this observation.

-

(i)

The original example we used to test for consistency was with the verb se marier ‘marry’. We give the relevant variants for completeness in (i) and (ii). However, se marie in (i) is ambiguous between present subjunctive and indicative, and so does not clearly show the correlation between consistency and mood choice.

-

(i)

J’envisage qu’il se marie avec Marie et J’envisage qu’il se

I envisage that he refl marry.subj with Marie and I envisage that he refl

marieavec Danielle

marry.subj with Danielle

‘I contemplate him marrying Marie and I contemplate him marrying Danielle.’

-

(iia)

??J’envisage qu’il va se marier avec Marie et j’envisage qu’il

I envisage that he go.indic.pres refl marry.inf with Marie and I envisage that he

va se marier avec Danielle. go.indic.pres refl marry.inf with Danielle

‘??I envisage that he is going to marry Marie and I envisage that he is going to marry

Danielle.’

-

(iib)

??J’envisage qu’il se mariera avec Marie et j’envisage qu’il se

I envisage that he refl marry.indic.fut with Marie and I envisage that he refl

mariera avec Danielle.

marry.indic.fut with Danielle

‘??I envisage that he will marry Marie and I envisage that he will marry Danielle.’

-

(i)

While casting this difference as a lexical ambiguity is sufficient for making the point here, it is worth exploring the possibility of analyzing the two readings of envisager as resulting not from an ambiguity, but from the independent contribution of mood.

The upcoming discussion is relevant for other cases of variation in mood marking that are accompanied with ambiguity in verb meaning. As mentioned in footnote 10, esperar in Spanish is a case in point: it means ‘hope’ when it governs the subjunctive, but ‘expect’ when it governs the indicative. We leave a closer investigation of this and other test cases to future research.

Proposals that stay within a Kratzerian framework and add to it include von Fintel and Iatridou (2008), (Rubinstein 2012, 2014), Portner and Rubinstein (2016), and Silk (2018). For analyses of ‘ought’ that assume a probabilistic and utility-based approach to modality, see Goble (1996), Yalcin (2010), Lassiter (2011, 2017).

The merge operation that is used in (66) is Frank’s (1996) compatibility-restricted union, which allows combination of inconsistent modal backgrounds. It reduces to our operation unify when the backgrounds are consistent.

Since deontic ka is a variable force modal, it is translated as ‘should’. Formally, what’s happening in (67) is that the subjunctive enforces a weakening. See Matthewson’s paper for details.

In this paper, we will not be able to explore the broader implications of our analysis for the St’át’imcets data. A central question is what makes attitude verbs in this language compatible with only one mood, the indicative, according to Matthewson (2010). One theoretical possibility is that St’át’imcets attitude verbs only express consistent backgrounds that can be simplified by spl. Another possibility is that St’át’imcets attitude verbs can simplify all modal backgrounds, even when they contain inconsistencies (relevant operations of simplification have been developed in the modality literature and have been tied to graded necessity; see Frank 1996; Rubinstein 2012, 2014). We also note a possible relation to differences in mood marking observed in Romance between attitude verbs and attitude nominals (see footnote 34).

The subjunctive mood would be compatible with committed backgrounds, as it is in Spanish with ‘hope’, and also with potentially non-committed backgrounds, as it is in both Spanish and French with ‘want’. This discussion may be related to the proposal by Portner (1997) and Schlenker (2005) that the subjunctive is the default mood, and that only indicative is contentful. Also, see Condoravdi and Lauer (2016) for relevant discussion of the meaning of ‘want’ and its compatibility with a wide range of preferences, including realistic and consistent ones (what they call “effective preferences”).

The following are some relevant quotes:

-

“[Notional mood] concerns the speaker’s commitment about the truth of the sentence in the actual world.” (Giorgi and Pianesi 1997, p. 210)

-

“Hooper [1975]... note[s] that assertives commit the subject of the matrix or the speaker to the truth of the complement, while nonassertives do not. Although there obviously is something right in the claim that the indicative is connected to complements that are taken to be true, and the subjunctive is connected to complements that are not ...” (Farkas 1992, p. 76)

-

“negation affects mood government only in case it is connected to change in type of epistemic commitment ...” (Farkas 1992, p. 71)

-

“If an attitude verb expresses such a commitment, it will be veridical and select the indicative; if not, it will be nonveridical and select the subjunctive.” (Giannakidou 2011, p. 9)

-

Formal details aside, Silk (2018) proposes an analysis in this spirit for French.

To be more precise, Silk’s (2018) view is that commitment is a relation between the “overall state of mind ... characterizing the event described by the predicate” and the relevant modal backgrounds (p. 143).

Silk (2018) claims that the infelicity of ‘hope’ in the bishop scenario (70) is due not to the status of the desire that the bishop be killed, but to failure of the verb’s diversity condition (recall (31) above) given that its modal background is the unaltered dox. This claim rests on the assumption that the king’s belief worlds (relative to the past situation being described) are uniform in his desire, i.e., that he saw no possibility that the bishop not be killed (Silk 2018, 150). We find this assumption implausible given that the scenario stresses the king’s unhappiness about the killing.

We have not yet attempted to explain the pattern of embedded epistemics discussed by Anand and Hacquard (2013), and so we cannot yet say that this difference is an advantage.

The distinction between the two be-verbs ésser and estar is not entirely clear in our investigation, and one of our consultants prefers the imperfect subjunctive form of ésser, fos, even to express meanings which would be expressed with estar in the present. Likewise, speakers differed in whether they prefer the definite article with all names. These complexities do not affect the conclusions about mood selection, but we mention them for completeness.

We have only consulted two Brazilian and one European speaker so far, and so we cannot attribute any of the language-internal variation we find to a difference between varieties.

Initial descriptions of the interpretation of ‘want’+indicative are not consistent. Thanks to Andrea Beltrama and Alda Mari for comments. As mentioned, other speakers find indicative completely ungrammatical. Given the sharp difference in judgments, a more thorough investigation would be required before settling on a description of the facts.

We call the composed form să fi fost the ‘past subjunctive’, but it appears to be a subjunctive perfect, not an imperfect subjunctive like the ones discussed in connection with some of the other languages described above.

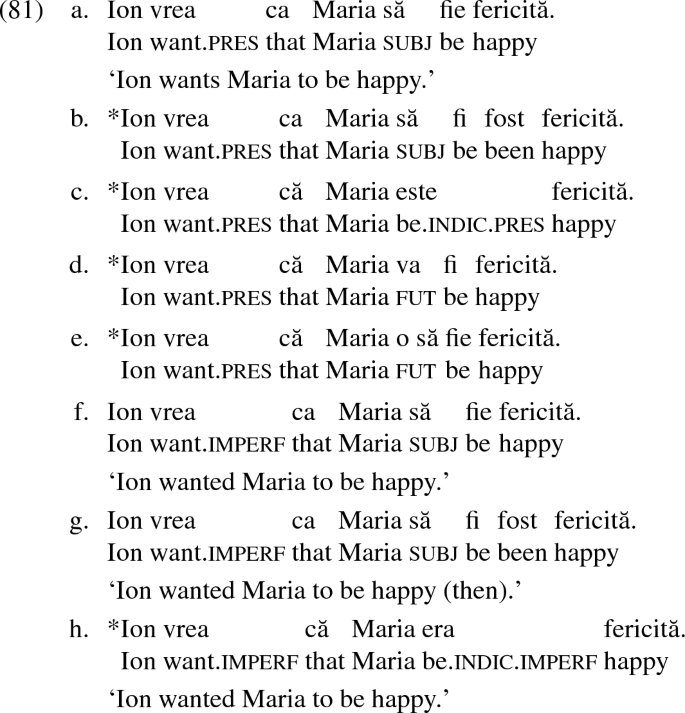

We present examples with two of the forms glossed as future, both of which pattern with indicatives. Note that Romanian has several complementizers, including ca and că, that correlate with mood and clause type (Hill 2002).

We would assume that indicative in the root clause expresses simple necessity, just as it does in a complement. The denotation of \([\theta _{indic}\ Mary\ runs]\) would be roughly (i). Assuming that the content of an utterance situation where an assertion takes place is the common ground (for type consistence, actually \(\lambda s[\mathrm {the common ground in } s]\)), the pragmatics of assertion would be a proposal to minimally adjust the common ground so that (i) applied to the utterance situation returns the value ‘true’.

-

(i)

\(\lambda s[sn( \{w : Mary\ runs\ in\ w\},content(s),s\})]\)

This approach to assertion is reminiscent of Charlow’s (2011) treatment of the directive update of imperatives.

-

(i)

This definition is based on Heim (1992), but assumes that there is a unique p world most similar to v.

Our version has some commonalities with Villalta’s (2008), but we do not adopt the comparison of multiple focus alternatives which is central to her proposal. See Rubinstein (2012, (2017) for an argument against the need for multiple alternatives and Harner (2016) for an argument against the analysis based on focus alternatives.

References

Anand, Pranav and Valentine Hacquard. 2013. Epistemics and attitudes. Semantics and Pragmatics 6: 1–59.

Brandner, Ellen. 2012. Syntactic microvariation. Language and Linguistics Compass 6: 113–130.

Charlow, Nathan. 2011. Practical language: Its meaning and use. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Michigan.

Condoravdi, Cleo and Sven Lauer. 2016. Anankastic conditionals are just conditionals. Semantics and Pragmatics 9: 1–69.

Crnič, Luka. 2011. Getting even. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

Davis, Henry, Lisa Matthewson, and Hotze Rullmann. 2009. “Out of control” marking as circumstantial modality in St’át’imcets. In Cross-linguistic semantics of tense, aspect, and modality, ed. Lotte Hogeweg, Helen de Hoop, and Andrej Malchukov, 205–244. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

del Rio, Claudia Crespo. 2014. Tense and mood variation in Spanish nominal subordinates: The case of Peruvian Spanish. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Falaus, Anamaria. 2010. Alternatives as sources of semantic dependency. In Proceedings of SALT 20, ed. Nan Li and David Lutz, 406–427. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications.

Farkas, Donka F. 1992. On the semantics of subjunctive complements. In Romance languages and modern linguistic theory, ed. Paul Hirschbüeler and E. F. K. Koerner, 69–104. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Farkas, Donka F. 2003. Assertion, belief, and mood choice. Paper presented at the Workshop on Conditional and Unconditional Modality, Vienna.

von Fintel, Kai. 1999. NPI licensing, Strawson entailment, and context dependency. Journal of Semantics 16: 97–148.

von Fintel, Kai. 2018. On the monotonicity of desire ascriptions. Manuscript, MIT.

von Fintel, Kai and Sabine Iatridou. 2008. How to say ought in foreign: The composition of weak necessity modals. In Time and modality, ed. Jacqueline Guéron and Jacqueline Lecarme, 115–141. Berlin: Springer. Available at: http://mit.edu/fintel/www/ought.pdf.

Frank, Anette. 1996. Context dependence in modal constructions. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Stuttgart.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1994. The semantic licensing of NPIs and the modern Greek subjunctive. In Language and cognition 4: Yearbook of the research group for theoretical and experimental linguistics, 55–68. Groningen: University of Groningen.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1995. Subjunctive, habituality, and negative polarity items. In Proceedings of SALT 5 ed. Mandy Simons and Teresa Galloway, 94–111. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1997. The landscape of polarity items. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Groningen.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1999. Affective dependencies. Linguistics and Philosophy 22: 367–421.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2009. The dependency of the subjunctive revisited: Temporal semantics and polarity. Lingua 119: 1883–1908.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2011. Nonveridicality and mood choice: subjunctive, polarity, and time. In Tense across languages, ed. Renate Musan and Monika Rathert. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Giorgi, Alessandra and Fabio Pianesi. 1997. Tense and aspect: From semantics to morphosyntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Goble, Lou. 1996. Utilitarian deontic logic. Philosophical Studies 82: 317–357.

Godard, Danièle. 2012. Indicative and subjunctive mood in complement clauses: from formal semantics to grammar writing. In Empirical issues in syntax and semantics 9, ed. Christopher Piñón, 129–148. Available at: http://www.cssp.cnrs.fr/eiss9/index_en.html.

Guajardo, Gustavo. 1997. Subjunctive and sequence of tense in three varieties of Spanish: Corpus and experimental studies of change in progress. Doctoral Dissertation, University of California San Diego.

Hacquard, Valentine. 2006. Aspects of modality. Doctoral Dissertation, MIT.

Hacquard, Valentine. 2010. On the event-relativity of modal auxiliaries. Natural Language Semantics 18: 79–114.

Harner, Hillary. 2016. The modality of desire predicates and directive verbs. Doctoral Dissertation, Georgetown University.

Heim, Irene. 1992. Presupposition projection and the semantics of attitude verbs. Journal of Semantics 9: 183–221.

Heim, Irene and Angelika Kratzer. 1998. Semantics in generative grammar. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hill, Virginia. 2002. Complementizer phrases (CP) in Romanian. Italian Journal of Linguistics 14: 223–248.

Hintikka, Jaakko. 1961. Modality and quantification. Theoria 27: 110–128.

Iatridou, Sabine. 2000. The grammatical ingredients of counterfactuality. Linguistic Inquiry 31: 231–270.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1974. Presupposition and linguistic context. Theoretical Linguistics 1: 181–194.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1977. What “must” and “can” must and can mean. Linguistics and Philosophy 1: 337–355.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1981. The notional category of modality. In Words, worlds and contexts, ed. Hans-Jürgen Eikmeyer and Hannes Rieser, 38–74. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. Modality. In Semantik/Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, ed. Arnim von Stechow and Dieter Wunderlich, 639–650. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2006. Decomposing attitude verbs. Talk at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem honoring Anita Mittwoch on her 80th birthday. Available at http://www.semanticsarchive.net/Archive/DcwY2JkM/attitude-verbs2006.pdf.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2012. Modal and conditionals: New and revised perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2013. Constructing domains for deonic (and other) modals. Slides for a talk given at the USC Deontic Modality Workshop, May 2013.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2019. Situations in natural language semantics. In The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy, ed. Edward N. Zalta. Available at: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/situations-semantics/.

Lassiter, Daniel. 2011. Measurement and modality: The scalar basis of modal semantics. Doctoral Dissertation, New York University.

Lassiter, Daniel. 2017. Graded modality: Qualitative and quantitative perspectives. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lewis, David K. 1981. Ordering semantics and premise semantics for counterfactuals. Journal of Philosophical Logic 10: 217–234.

Mari, Alda and Paul Portner. 2018. Mood variation with belief predicates: Modal comparison in semantics and the common ground. Manuscript, ENS and Georgetown University.

Matthewson, Lisa. 2010. Cross-linguistic variation in modality systems: The role of mood. Semantics and Pragmatics 3: 1–74.

Matthewson, Lisa, Hotze Rullmann, and Henry Davis. 2007. Evidentials as epistemic modals: Evidence from St’at’imcets. The Linguistic Variation Yearbook 7: 201–254.

Moulton, Keir. 2009. Clausal complementation and the wager-class. In Proceedings of NELS 38, ed. Anisa Schardl, Martin Walkow, and Muhammad Abdurrahman, volume 2, 165–178. Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Poplack, Shana. 1992. The inherent variability of the French subjunctive. In Theoretical analyses in Romance linguistics, ed. Christiane Laeufer and Terrell Morgan, 235–263. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Poplack, Shana, Rena Torres Cacoullos, Nathalie Dion, Rosane de Andrade, Salvatore Digesto Berlinck, Dora Lacasse, and Jonathan Steuck. 2018. Variation and grammaticalization in Romance: A cross-linguistic study of the subjunctive. In Manuals in linguistics: Romance sociolinguistics, ed. Wendy Ayres-Bennett and Janice Carruthers, 217–252. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Poplack, Shana, Allison Lealess, and Nathalie Dion. 2013. The evolving grammar of the French subjunctive. Probus 25: 139–195.

Portner, Paul. 1992. Situation theory and the semantics of propositional expressions. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Portner, Paul. 1997. The semantics of mood, complementation, and conversational force. Natural Language Semantics 5: 167–212.

Portner, Paul. 2018. Mood. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Portner, Paul and Aynat Rubinstein. 2012. Mood and contextual commitment. In Proceedings of SALT 22 ed. Anca Chereches, 461–487. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications. Available at: https://journals.linguisticsociety.org/proceedings/index.php/SALT/article/view/2642.

Portner, Paul and Aynat Rubinstein. 2016. Extreme and non-extreme deontic modals. In Deontic modals, ed. Nate Charlow and Matthew Chrisman. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quer, Josep. 1998. Mood at the interface. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics.

Quer, Josep. 2010. Mood in Catalan. In Mood in the languages of Europe, ed. Rolf Thieroff and Björn Rothstein, 221–236. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Rubinstein, Aynat. 2012. Roots of modality. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Rubinstein, Aynat. 2014. On necessity and comparison. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 95: 512–554.

Rubinstein, Aynat. 2017. Straddling the line between attitude verbs and necessity modals. In Modality across syntactic categories, ed. Ana Arregui, María Luisa Rivero, and Andreś Salanova, 109–131. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rubinstein, Aynat. to appear. Weak necessity. In Companion to semantics, ed. Daniel Gutzmann, Lisa Matthewson, Cécile Meier, Hotze Rullmann, and Thomas Ede Zimmermann. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

Rullmann, Hotze, Lisa Matthewson, and Henry Davis. 2008. Modals as distributive indefinites. Natural Language Semantics 16: 317–357.

Scheffler, Tatjana. 2008. Semantic operators in different dimensions. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Schlenker, Philippe. 2005. The lazy Frenchman’s approach to the subjunctive (speculations on reference to worlds and semantic defaults in the analysis of mood). In Romance languages and linguistic theory 2003: Selected papers from “Going Romance”, ed. Twan Geerts, Ivo van Ginneken, and Haike Jacobs, 269–310. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Sessarego, Sandro. 2010. Temporal concord and Latin American Spanish dialects: A genetic blueprint. Revista Iberoamericana de Lingüística 5: 137–169.

Silk, Alex. 2018. Commitment and states of mind with mood and modality. Natural Language Semantics 26: 125–166.

Smirnova, Anastasia. 2012. The semantics of mood in Bulgarian. In Proceedings of the Chicago Linguistics Society 48, 547–561. Chicago, MA: CLS.

Stalnaker, Robert. 1984. Inquiry. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Suñer, Margarita and J. Padilla-Rivera. 1987. Sequence of tenses and the subjunctive, again. Hispania 70: 634–642.

Villalta, Elisabeth. 2006. Context dependence in the interpretation of questions and subjunctives. Doctoral Dissertation, Universität Tübingen.

Villalta, Elisabeth. 2008. Mood and gradability: An investigation of the subjunctive mood in Spanish. Linguistics and Philosophy 31: 467–522.

Yalcin, Seth. 2010. Probability operators. Philosophy Compass 5: 916–937.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We would like to thank our consultants: Delphine Kanyandekwe, Pascal Moyal, Valentine Hacquard, Chloé Tahar, Isabelle Charnavel, Héctor Campos, Paula Menéndez-Benito, Elena Herburger, Alda Mari, Raffaella Zanuttini, Andrea Beltrama, Michael Ferrara, Marco Alves, Ricardo Cyncynates, Armanda Ulldemolins Subirats, David Ginebra, Mihaela Baicoianu, Donka Farkas, and Carla Baricz. We received extremely helpful feedback from many colleagues, in particular Alda Mari, Elena Herburger, Philippe Schlenker, Paula Menéndez-Benito, Kai von Fintel, and Luka Crnič, as well audiences at Bar-Ilan University, the École normale supérieure, and Georgetown University. This research was supported by a Senior Faculty Research Fellowship from Georgetown University and a visiting professorship from the Institut Jean Nicod, ENS, to Paul Portner and a research grant from the Mandel Scholion Research Center at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem to Aynat Rubinstein. We also thank our reviewers and the editors at Natural Language Semantics for helping us to focus the argument and polish its final presentation.

Appendices

Appendix A: Preliminary data on mood selection in other Romance languages

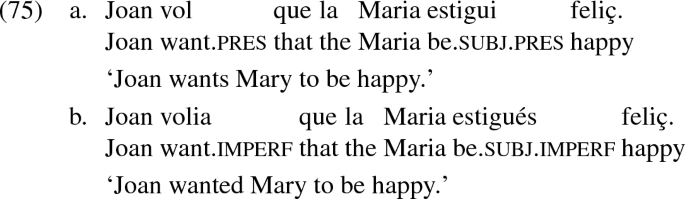

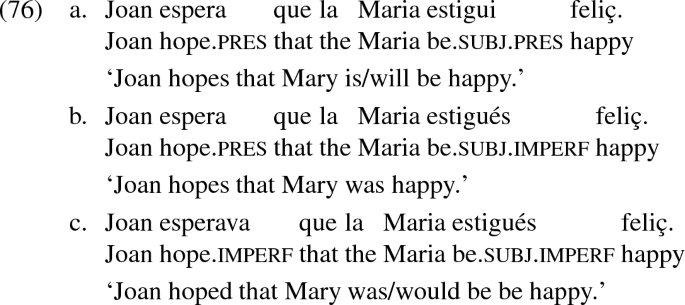

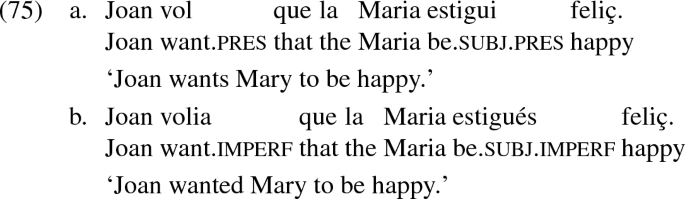

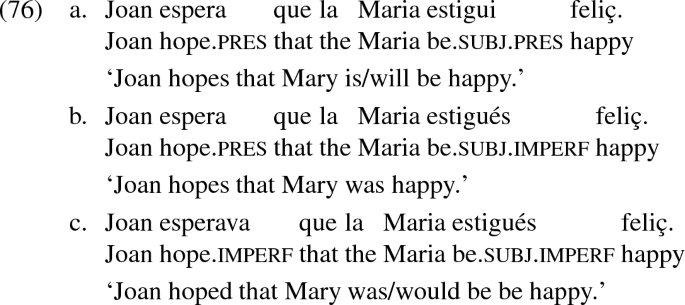

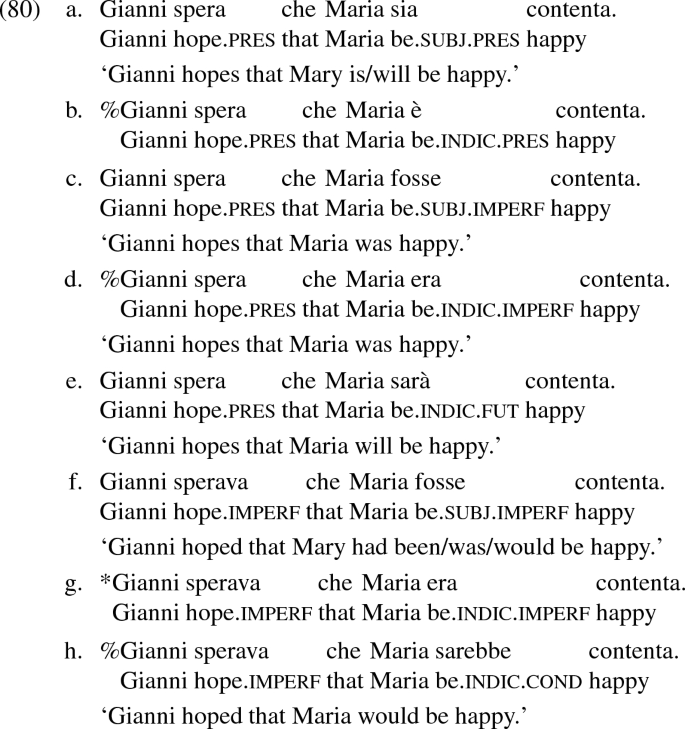

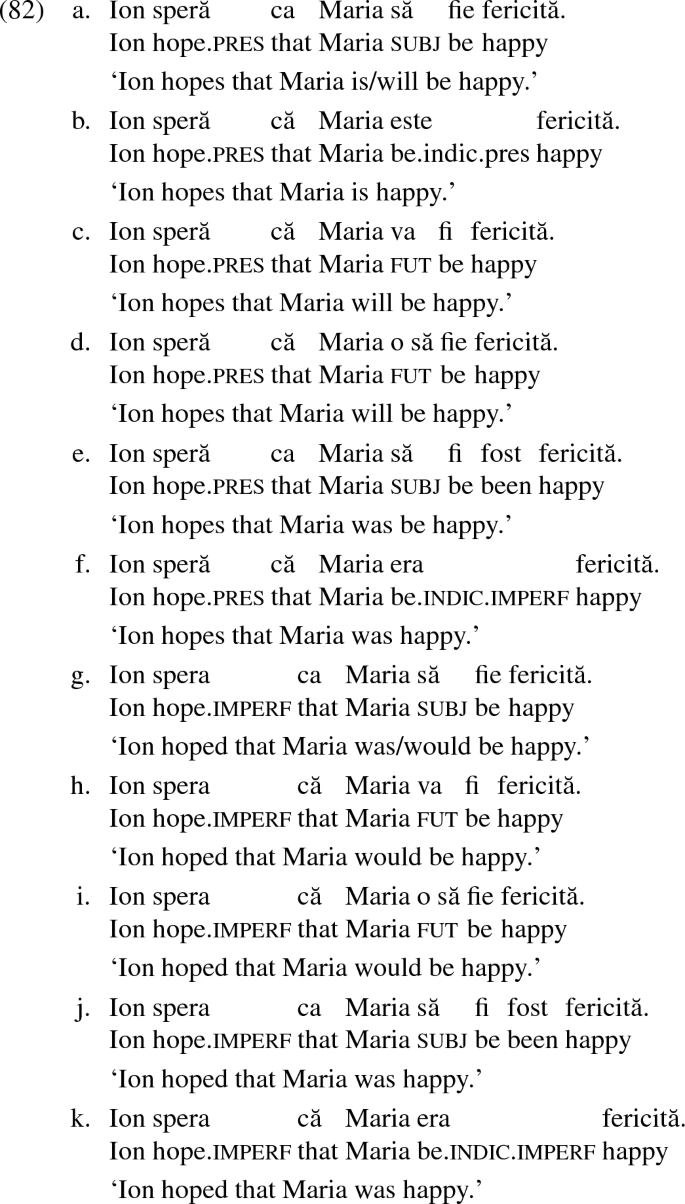

In this Appendix, we give a bit more detail on our preliminary findings concerning mood selection with ‘want’ and ‘hope’ in Catalan, Italian, Portuguese, and Romanian.

-

1.

Catalan allows only subjunctive with both ‘want’ and ‘hope’ across tenses.Footnote 48Voler (‘want’) is non-past oriented.

Esperar (‘hope’) allows both future and present orientation with present subjunctive under a present tense matrix, and it allows past orientation (i.e., backshifting) with the imperfect under present tense. However, imperfect under imperfect does not seem to allow backshifting; a perfect form is required for that meaning.

-

2.

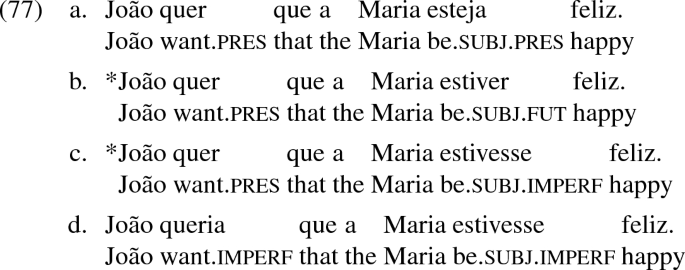

Portuguese requires subjunctive with quer ‘want’, like French, Spanish, and Catalan, but shows a high degree of freedom of mood choice with esperar ‘hope’. Present tense ‘want’ requires present subjunctive, with either simultaneous or future orientation; the incompatibility with past orientation rules out the imperfect, and while Portuguese has a future subjunctive, it is not used for future orientation in this context. Past tense ‘want’ only allows imperfect subjunctive.Footnote 49

‘Hope’ allows both indicative and subjunctive, but there are two interesting facts: first, imperfect under present is ruled out for one of our consultants; this suggests that present tense esperar is non-past oriented for some speakers, like ‘want’ (note that it can also mean ‘wait for’). Second, indicative imperfect is not allowed under imperfect for one of our speakers. In contrast, the other speakers continued the pattern of both moods being allowed under ‘hope’ even into the past. Imperfect subjunctive under imperfect allows backshifted, simultaneous, and future-oriented temporal relations. The future-oriented interpretation sometimes has a counterfactual inference (and our consultants differed in terms of which be-verb, estar or ser, they preferred here); the backshifted reading is easier to access with an eventive predicate.

The situation in Portuguese is complex, and the differences in judgment among our small group of speakers suggest that there is much to be discovered in a more thorough investigation of this language. Neverthess, as far as mood choice goes, the pattern is in line with our expectations.

-

3.

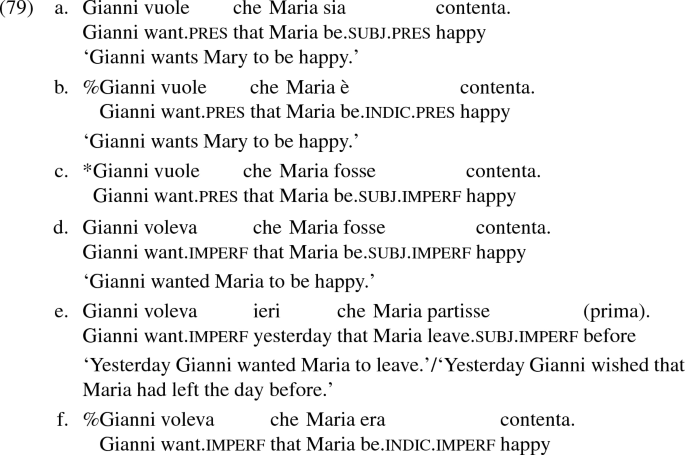

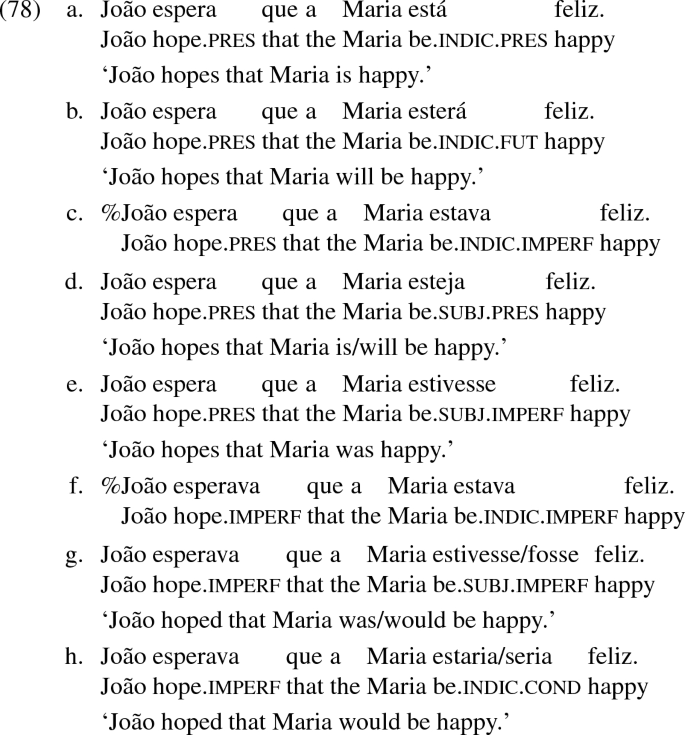

In Italian, many speakers only accept subjunctive with volere ‘want’, but some speakers also allow a tense-matching indicative with simultaneous interpretation and a distinct meaning which we have not yet investigated ((79b) and (79f)).Footnote 50 Unlike in French and Spanish, ‘want’ allows past orientation with imperfect in both the matrix and subordinate clause, at least with an event verb as in (79e); this pattern is described as having a counterfactual interpretation similar to ‘wish’, but more study is clearly required.

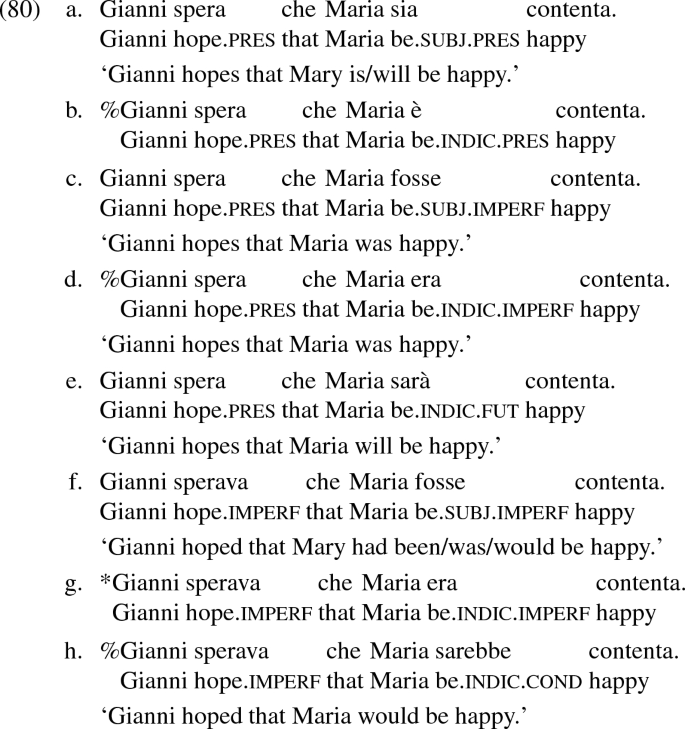

Our consultants for Italian showed two patterns with regard to mood choice with sperare ‘hope’, one more like Portuguese in allowing both indicative and subjunctive in many cases, and one more like Spanish and Catalan, allowing only subjunctive. ‘Hope’ allows past orientation in both the present and past.

As with Portuguese, the facts for Italian are complex and in need of much futher investigation.

-

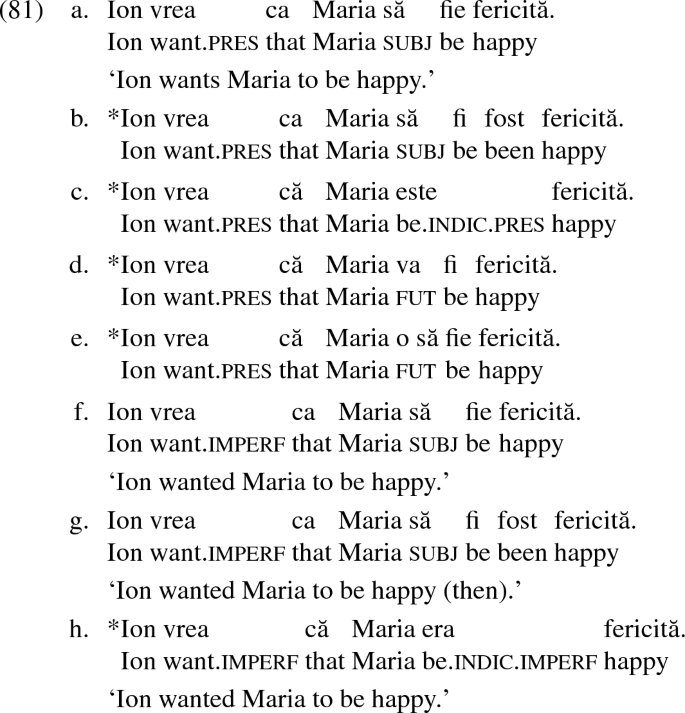

4.

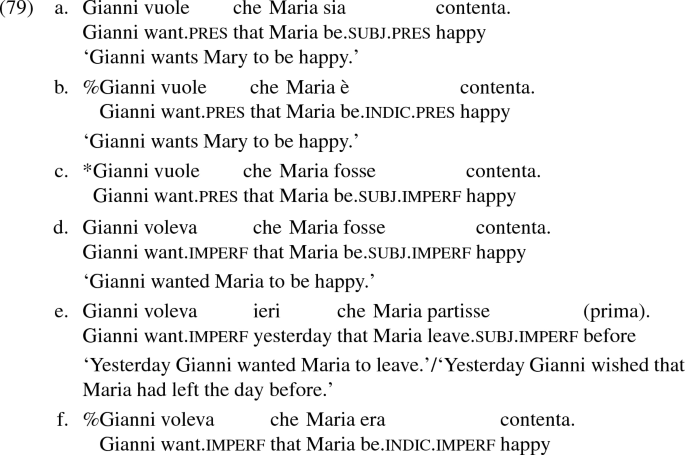

Romanian vrea ‘want’ selects subjunctive, as in the other languages, with present subjunctive allowed under matrix present or past, expressing simultaneous or future orientation. Past subjunctive is only possible under matrix past, with a simultaneous interpretation.Footnote 51\(^{,}\)Footnote 52

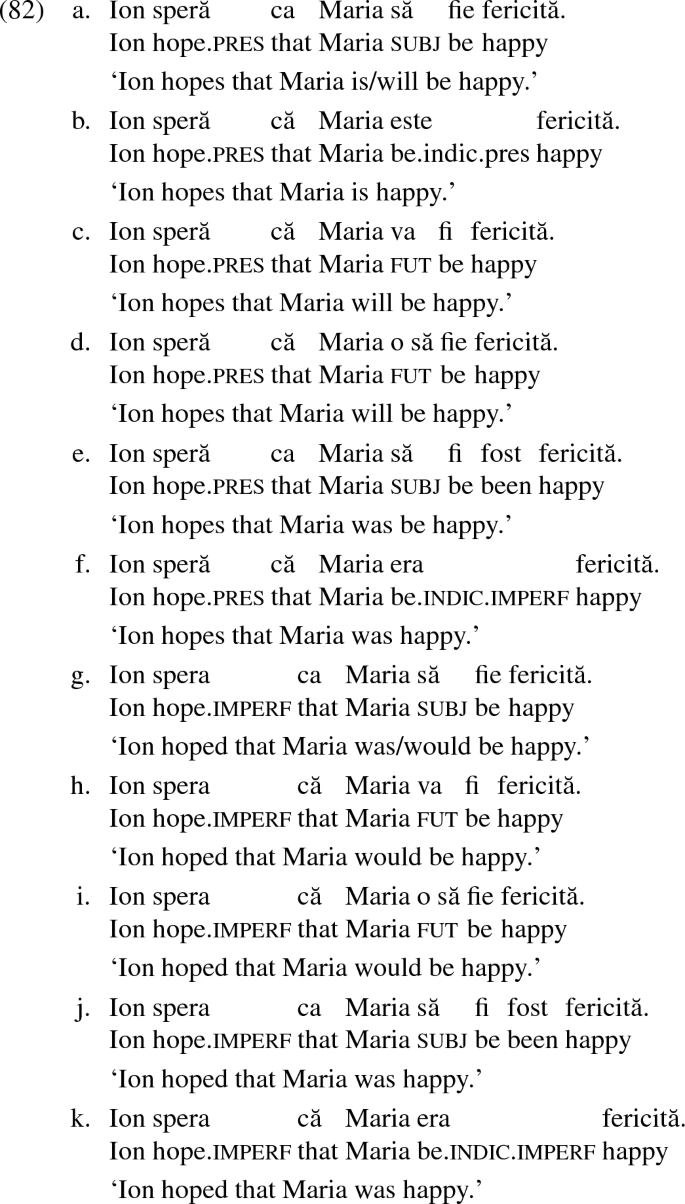

Spera ‘hope’ freely allows both indicative and subjunctive across all tenses. This consistent flexibility means that Romanian is likely to be an important case study for future work on mood selection with desire verbs. Mood and tense interact in ways we do not describe fully here. For example, according to our preliminary investigation, subjunctive under imperfect (82g) allows past, simultaneous, and future orientation, while the imperfect indicative under imperfect (82k) allows only past or simultaneous orientation; future is used for future orientation with the indicative.

Appendix B: Formal systems

In this Appendix we present our analyses of Spanish and French in a compositional way. We specify the semantics by giving meanings in an English-based metalanguage of the kind presented in Heim and Kratzer (1998). Note that the only difference between the languages is found in the meanings of the mood thematic relations (see the entries for \(\theta _{indic}\) and \(\theta _{subj}\) in Semantics: Lexicon below).

1.1 B.1 Version 1: Premise semantics

Syntax: Phrase structure For this demonstration fragment, we interpret lexicalizations of (83). We assume that M raises to C from somewhere within TP in order to take scope over TP.

For simplicity, we label verbs as having either an experiencer or an agent subject, but we would assume that there is a better syntactic/semantic explanation for the assignment of thematic roles to nominal arguments. Because we are focusing on selected mood, we do not consider the mood marker in the root clause.Footnote 53

Syntax: Lexicon Single quotes indicate that the entries represent lexical items in each relevant language.

-

1.

N: ‘John’, ‘Mary’

-

2.

V\(_{exp}\): ‘believes’, ‘wants’, ‘hopes’

-

3.

C: ‘that’

-

4.

\(\Theta \): \(\theta _{exp}\), \(\theta _{agent}\)

-

5.

M: \(\theta _{indic}\), \(\theta _{subj}\)

-

6.

T: present

-

7.

V\(_{agent}\): ‘leaves’

Semantics: Lexicon (premise semantics) Functional meanings are expressed in a predicate logic-like metalanguage. For example, \(\lambda s[believing(s)]\) is the function that is defined for any situation s; it is true of s if s is a believing situation, and false of s otherwise. Variables are implicitly sorted as \(x\in \) Individuals, \(s\in \) Situations, \(w\in \) Worlds.

-

1.

\([[{`\mathsf John'}]] = john\)

-

2.

\([[{`\mathsf Mary'}]] = mary\)

-

3.

\([[{`\mathsf believes'}]] = \lambda s[believing(s)]\)

-

4.

\([[{`\mathsf wants'}]] = \lambda s[wanting(s)]\)

-

5.

\([[{`\mathsf hopes'}]] = \lambda s[hoping(s)]\)

-

6.

\([[{`\mathsf leaves'}]] = \lambda s[leaving(s)]\)

-

7.

\([[{`\mathsf that'}]] = \lambda m\in D_{\langle \langle s,t\rangle , \langle s, t\rangle \rangle }[m]\).

-

8.

\([[{present}]] = \lambda p \lambda w \exists s[s<w \wedge s\circ now \wedge p(s)]\)

-

9.

\([[{\theta _{agent}}]] = \lambda x \lambda s[Agent(s,x)]\)

-

10.

\([[{\theta _{exp}}]] = \lambda x \lambda s[Experiencer(s,x)]\)

-

11.

\([[{\theta _{indic}}]]\) =

-

Spanish: \(\lambda p\lambda s[sn(p,content(s),s)]\)

-

French: \(\lambda p\lambda s[sn(p,\) spl(content(s)), s)]

-

12.

\([[{\theta _{subj}}]] =\)

-

Spanish: \(\lambda p\lambda s[ln(p,content(s),s)]\)

-

French: \(\lambda p\lambda s[ln(p,\) spl(content(s)), s)]

Semantics: Composition rules

-

1.

For any subtree \([_{\alpha }\ \beta ]: [[{\alpha }]] = [[{\beta }]], \mathrm{unless} \,{{\alpha }} =\) Root

-

2.

For any subtree \([_{\alpha }\ \beta ]\): if \(\alpha \) = Root, then \([[{\alpha }]] = \exists w[[[{\beta }]](w)]\)

-

3.

For any subtree \([_{\alpha }\ \beta \ \gamma ]\): if \([[{\beta }]]\) is a function with \([[{\gamma }]]\) in its domain, then \([[{\alpha }]] = [[{\beta }]]([[{\gamma }]])\)

-

4.

For any subtree \([_{\alpha }\ \beta \ \gamma ]\): if both \([[{\beta }]]\) and \([[{\gamma }]]\) are the characteristic functions of sets of situations, then \([[{\alpha }]] = \lambda s[[[{\beta }]](s) \wedge [[{\gamma }]](s)]\)

Important metalanguage functions (premise semantics)

-

1.

content(s) is only defined if s is a content-bearing situation. For any content-bearing situation s, content(s) is a modal background or pair of modal backgrounds representing the cognitive or informational content borne by s. Specifically:

-

(a)

If s is a believing situation, then \(content(s)=dox\)

-

(b)

If s is a wanting situation, then \(content(s)=\langle bul,dox^{+}\rangle \)

-

Diversity property: \(\forall s[wanting(s) \rightarrow \bigcap second(content(s))\cap p\ne \emptyset \) and \(\bigcap second(content(s))\backslash p\ne \emptyset ]\)

-

-

(c)

If s is a hoping situation, then \(content(s)=\langle bul^c,dox\rangle \)

-

Diversity property: \(\forall s[hoping(s) \rightarrow \bigcap second(content(s))\cap p\ne \emptyset \) and \(\bigcap second(content(s))\backslash p\ne \emptyset ]\)

-

Consistency property: \(\forall s[hoping(s)\rightarrow \bigcap (bul^c(s)\cup dox(s))\ne \emptyset ]\).

-

-

(a)

-

2.

sn(p, B, s) is only defined if p is a proposition, B is a single modal background, s is a content-bearing situation, and B(s) is defined. When defined, sn(p, B, s) is true iff \(\bigcap B(s)\subseteq p\).

-

3.

ln(p, B, s) is only defined if p is a proposition, B is a pair of modal backgrounds \(\langle g, f\rangle \), s is a content-bearing situation, and f(s) and g(s) are both defined. When defined, ln(p, B, s) is true iff \(\exists b[b \in BestSets(g,f,s) \wedge b\subseteq p]\).

-

4.

\(BestSets(g,f,s) = \{X : \forall w\forall v[(w\in X \wedge v\in X) \leftrightarrow (\{p\in g(s) : w\in p\}=\{p\in g(s) : v\in p\}\wedge w\in Best(g,f,s) \wedge v\in Best(g,f,s)\}\)

-

5.

\(Best(g,f,s) = \{w : w\in \bigcap f(s) \wedge \lnot \exists v[v\in \bigcap f(s) \wedge v <_{g(s)} w]\}\)

-

6.

Unify\((\langle g, f\rangle )\) is only defined if M is a pair of modal backgrounds and \(\forall s[s\in domain(f)\rightarrow (s\in domain(g) \wedge \bigcap (g(s)\cup f(s))\ne \emptyset )]\). When defined, \({\textsf {unify}}(\langle g, f\rangle ) = [\lambda s:\ s\in domain(f)\ .\ g(s)\cup f(s)]\).

-

7.

spl(M) is only defined if M is a sequence of modal backgrounds. When defined, spl\((M) {=} \) unify(M) if \({\textsf {unify}}(M)\) is defined; otherwise, spl\((M) {=} M\).

-

Equivalence of ln and sn after unification: If \(\textsf {unify}(\langle g,f\rangle )\) is defined, \(sn(p,\textsf {unify}(\langle g,f\rangle ),s) = ln(p,\langle g,f\rangle ,s)\) (for every proposition p and situation \(s\in domain(f)\)).

-

Proof

Assume that \({\textsf {unify}}(\langle g, f\rangle )\) is defined; therefore \(\bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\ne \emptyset \) for every s in the domain of f. Assume that s is in the domain of f.

The essence of the proof is that, when \(f(s)\cup g(s)\) is consistent, \(\bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\) is the sole member of BestSets(g, f, s), and so \(\bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\subseteq p\) iff \(\exists b[b\in BestSets(g,f,s) \wedge b\subseteq p]\).

(1) First we show that \(\bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\in BestSets(g,f,s)\). This requires that \(\forall w\forall v[(w\in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s)) \wedge v\in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))) \leftrightarrow (\{p\in g(s) : w\in p\}=\{p\in g(s) : v\in p\}\wedge w\in Best(g,f,s) \wedge v\in Best(g,f,s))\).

-

Left to right. Suppose we have a \(w\in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\) and a \(v\in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\). Then \(w\in Best(g,f,s)\). To see this, assume \(w\not \in Best(g,f,s)\); then either \(w\not \in \bigcap f(s)\), or \(\exists q\in g(s)\) such that for some \(u\in \bigcap f(s)\), \(u\in q \wedge w\not \in q\). But since \(w\in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\), \(w\in \bigcap f(s)\), and there is no such u or q. (Similarly for v.)

Next, show that \(\{p\in g(s) : w\in p\}=\{p\in g(s) : v\in p\}\). Suppose the contrary. Then there must be a \(q\in g(s)\) such that either \(w\in q \wedge v\not \in q\) or \(w\not \in q \wedge v\in q\). Neither of these can be because \(w,v\in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\).

-

Right to left. Suppose we have w and v such that \(\{p\in g(s) : w\in p\}=\{p\in g(s) : v\in p\}\wedge w\in Best(g,f,s) \wedge v\in Best(g,f,s)\) but \(w\not \in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\) or \( v\not \in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s)\). Since \(w\in Best(g,f,s)\) and \(g(s)\cup f(s)\) is consistent, \(w\in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\), and similarly for v. To prove this, assume the contrary; then there is some \(q\in f(s)\cup g(s)\) such that \(w\not \in q\). If \(q\in f(s)\), then \(s\not \in Best(g,f,s)\), contradicting the assumption that \(w\in Best(g,f,s)\); and if \(q\in g(s)\), then there is a \(u\in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\) such that \(u<_{g(s)}) w\), contradicting the assumption. (Similarly for v.)

(2) Next we show that there is no other member of BestSets(g, f, s) than \(\bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\). Suppose that there were some other such set X. Then there is either a world u such that \(u\in X\) but \(u\not \in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\) or vice versa.

Assume there exists a u such that \(u\in X\) but \(u\not \in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\). Then either \(u\not \in \bigcap f(s)\) or \(u\not \in \bigcap g(s)\). If the former, then \(u\not \in Best(g,f,s)\), and so \(u\not \in X\), contradicting the assumption. If the latter, then there is some \(q\in g(s)\) such that \(u\not \in q\). Let \(u'\) be a world such that \(u' \in q\) and \(u' \in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\). In this case, \(u' <_{g(s)} u\), and so \(u\not \in Best(g,f,s)\), and so not in X, contradicting our assumption.

Alternatively, assume that there is a u such that \(u\in \bigcap (f(s)\cup g(s))\) but \(u\not \in X\). Unless \(X=\emptyset \), there is a world \(u'\in X\) such that \(u'\ne u\) and \(u'\in Best(g,f,s)\). If \(u'\in \bigcap g(s)\), then \(\{p\in g(s) : u'\in p\}=\{p\in g(s) : u\in p\}\), contrary to our assumption that \(u\not \in X\). Otherwise, there is a \(q\in g(s)\) such that \(u'\not \in q\). But then \(u <_{g(s)} u'\), contrary to our assumption that \(u'\in Best(g,f,s)\).

-

8.

first(X) and second(X) are only defined if X is an ordered pair. When defined, first(X) is the first member of X and second(X) is the second member of X.

1.2 B.2 Version 2: Similarity semantics

The fragment which uses similarity semantics is largely the same as the premise semantics version. The only differences are in the entries for the subjunctive theta role (Semantics: Lexicon 12, redefined below), and associated definitions.

Semantics: Lexicon (similarity semantics)

-

12.

\([[{\theta _{subj}}]] =\)

-

Spanish: \(\lambda p\lambda s[\leadsto ^{second(content(s))(s)}_{p}\subseteq <_{first(content(s))(s)}]\)

-

French: \(\lambda p\lambda s[\leadsto ^{second(\mathsf{spl}(content(s))(s)}_{p}\subseteq <_{first(\mathsf{spl}(content(s))(s)}]\)

-

Important metalanguage functions (similarity semantics) The similarity semantics relies on the definition of \(\leadsto \):

-

9.

For any proposition p and world v, SIM(p)(v) is the world \(w\in p\) which is most similar to v; hence if \(v\in p\), \(v=w\).Footnote 54

-

10.

For any worlds w and v, premise set B and proposition p, \(w \leadsto ^{B}_{p} v\) if and only if either (i) \(w\in p\cap (\bigcap B)\) and \(v=SIM(\lnot p)(w)\) or (ii) \(v\in \lnot p\cap (\bigcap B)\) and \(w=SIM(p)(v)\).

To see how these definitions work, consider a Spanish subjunctive clause with denotation \(\lambda s[\leadsto ^{second(content(s))(s)}_{p}\subseteq <_{first(content(s))(s)}]\). When applied to a wanting situation s, \(\leadsto ^{second(content(s))(s)}_{p}\) forms the set of pairs \(\langle w,v\rangle \) where either w is a p world in \(dox^+(s)\) and v is the most similar \(\lnot p\) world, or where v is a \(\lnot p\) world in \(dox^+(s)\) and w is the most similar p world. These are the similarity pairs which differ in the truth value of p and at least one member of which is a belief(+) world. If the set of such pairs is a subset of \(<_{bul(s)}\), this is to say that each p world is more-desired than its most similar \(\lnot p\) world.

In French, the definition of subjunctive contains spl. When s is a hoping situation, and so the two components of content(s) can be unified, \(second(\textsf {spl}(content(s)))\) is not defined because spl\({\text{(content(s)) }}\) is a singleton. Thus, when the subjunctive is used with ‘hope’ in French, the derivation fails at the point when the subjunctive-marked clause is combined with the verb.

Comments on the similarity analysis. In the version of our analysis which builds on the similarity semantics, we do not predict equivalence between French ‘hope’+indicative and Spanish ‘hope’+subjunctive. More precisely, the following two sentences would not have the same truth conditions (even assuming that Pierre and Pedro refer to the same person and Fido court and Fido corra denote the same proposition).

Because unification is successful, the semantics for the French case would be the same as under the premise semantics; it is true iff all of the most desirable worlds compatible with Peter’s beliefs are ones in which Fido runs. In contrast, the Spanish counterpart could be false even if all of the most desirable worlds compatible with Peter’s beliefs are ones in which Fido runs, for example if for one such world, the most similar world in which Fido doesn’t run is more preferable (and not a belief world). A case which brings the difference out more clearly would be (85).

The example is true in this scenario, but arguably, for some belief world w in which I pay $1, the most similar world in which I don’t pay $1 is one in which I pay $.50 and not $300. If so, ‘I hope to pay a dollar to enter the show’ will be false in Spanish according to the definitions above.

Because the notion of similarity is vague and it is not clear how the particular beliefs and desires of the experiencer factor into it, we can’t prove that this scenario or another like it is a problem. We also can’t prove it is not a problem, and thus conclude that the similarity-based approach cannot be shown to predict the equivalence between the French and Spanish counterpart ‘hope’ sentences. Given that the sentences are equivalent, as far as we know, there is reason to prefer the premise semantics approach, where the equivalence follows directly.

Heim (1992) considered a variant of the similarity approach which is like ours,Footnote 55 but in her official version both members of each similarity pair are required to be belief worlds. It is worth noting that, even with this assumption, simplification is not necessarily meaning preserving. In Spanish (without simplification), (84b) is true if each world within the set of belief worlds in which Fido runs is better than its most similar counterpart (also a belief world), and each world within the set of belief worlds where Fido does not run is worse than its most similar counterpart (also a belief world). These truth conditions require that (i) the very best belief worlds are ones in which Fido runs, and also that (ii) non-ideal belief worlds where Fido runs are better than their most similar not-running counterparts. In contrast, for French (84a) with simplification and a simple necessity semantics, only condition (i) holds. In other words, the similarity semantics with the assumption that the relevant comparisons involve pairs of belief worlds predicts that ‘hope’ sentences have weaker truth conditions in French. This point has been made by von Fintel (2018); he argues that meanings for desire sentences assigned by the similarity semantics are not just stronger, but in fact too strong. If he is correct in this, that is already a sufficient reason to prefer the premise semantics approach.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Portner, P., Rubinstein, A. Desire, belief, and semantic composition: variation in mood selection with desire predicates. Nat Lang Semantics 28, 343–393 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09167-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09167-7