Abstract

In “Must ...stay ...strong!” (von Fintel and Gillies in Nat Lang Semant 18:351–383, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-010-9058-2), we set out to slay a dragon, or rather what we called The Mantra: that epistemic must has a modal force weaker than expected from standard modal logic, that it doesn’t entail its prejacent, and that the best explanation for the evidential feel of must is a pragmatic explanation. We argued that all three sub-mantras are wrong and offered an explanation according to which must is strong, entailing, and the felt indirectness is the product of an evidential presupposition carried by epistemic modals. Mantras being what they are, it is no surprise that each of the sub-mantras have been given new defenses. Here we offer them new problems and update our picture, concluding that must is (still) strong.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To be sure, different theories can and do instantiate W1–W3 in different ways.

The examples are all from von Fintel and Gillies (2010).

We noted a similar point for must in premises:

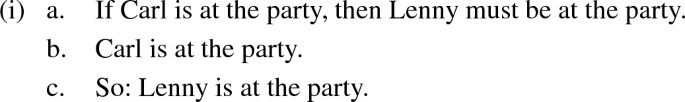

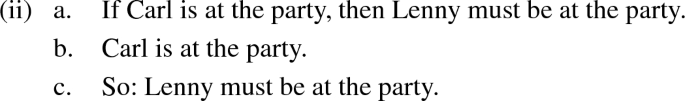

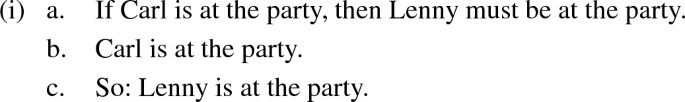

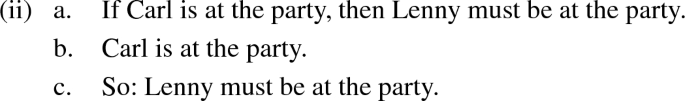

W1 and W2 together predict that (ic) isn’t entailed by the premises (ia) and (ib). Our judgment goes the other way. Lassiter (2016, 139–141) is unmoved by this, arguing that this should be explained away: (ic) only seems to be entailed by (ia) and (ib) when it is really only nearly-entailed. Our point is that there is no relevant difference between (i) and (ii):

A theory that says there is a difference but explains it away by insisting that we are systematically mistaken about it is dispreferred to one that embraces the non-difference and predicts it.

K for kernel (not knowledge) and B for base (not belief). Formally, kernels are Kratzerian modal bases but we use their structure in a novel way. This definition, like Definition 4 in von Fintel and Gillies (2010), treats all information as either direct enough or as following from what is direct enough. This is a simplification and can be removed. Here’s what we said about it before: “It is an optional extra and our story is officially agnostic on it. To remove its trace: introduce an upper bound \(U \subseteq W\) representing the not-direct-but-not-inferred information in the context and relativize all our definitions to this upper bound instead” (p. 371).

It has been suggested that maybe this must isn’t an epistemic must but alethic, truth-in-all-possible-worlds must (Giannakidou 1999; Goodhue 2017; Giannakidou and Mari 2018). The question is: why not epistemic? If the answer is because there is no weakness, then the suggestion is unmotivated. If the answer is instead more along the lines of the argument we consider in the main text, then that would be principled but, as we’ll argue, still not convincing.

One reviewer disagreed with our judgment and found no significant contrast between (9) and (10). It is tempting to despair over such disagreements between speakers with vested interests. We note that Del Pinal and Waldon ’s (2019) experiments corroborated that there is a significant contrast in this case.

That’s not quite what we promised wouldn’t happen. In any case, we (of course) welcome data wherever it can be found: the lab, the wild, and the armchair. What we don’t agree with is some of the surrounding rhetoric that the examples collected from the wild are somehow more probative than intuitive judgments about homegrown examples because the latter are “mere intuitions” (Lassiter 2016, 139). In the end Lassiter relies on his judgment that the examples from his corpus search are coherent and sensible and invites us (collectively) to share that judgment. So it’s “mere intuitions” all around or nowhere. We prefer to call it all data. And as we discuss in the text, we think there is a clear and motivated explanation for such data compatible with S1–S3.

Del Pinal and Waldon (2019) provide further corroboration that these conjunctive passages are acceptable to some significant degree.

As Dan Lassiter put it at a workshop at the Ohio State University.

To forestall confusion: this is not the same thing as saying that speakers shouldn’t be willing to utter or assent to such conjunctions. We’ll return to this point below.

We note that both reviewers disagreed with our judgment that there is a difference in acceptability in A’s replies.

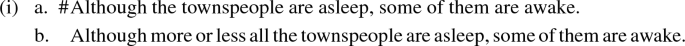

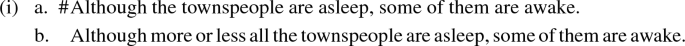

The although device is borrowed from an interesting argument by Kroch (1974, 190–191), who used it to show that definite plurals, even though in some sense they allow exceptions, behave like universal quantifiers in controlled conjunctions:

See Lasersohn (1999, 523) and Križ (2015, 4) for some discussion.

Again, there is disagreement about this judgment from the reviewers.

There are coherent readings of x is not certain that \(\phi \) but \(\textit{must} \, \phi \) where there are multiple bodies of information (one for x and one for us). But because of the multiplicity of bodies of information such readings don’t speak directly to whether \(\textit{must} \, \phi \) is compatible with expressions that \(\phi \) might not be true. Note that this kind of differential targeting isn’t possible in (17) and (18).

For once, it is pleasing to note that both reviewers agree with our judgments in these cases.

We borrow the ‘many-subject’ vs. ‘few-subject’ terminology from Jacobson (2018).

Our assessment has since been confirmed in an experiment reported at the 2020 CUNY Sentence Processing conference by Ricciardi et al. (2020), who found that in a within-subject design, Lassiter’s results do not persist.

A reviewer finds that can’t is stronger than must not. We don’t share that judgment.

For the record: we have the same judgments in (21) and (22) with it’s possible replaced by perhaps/maybe/might.

There is a similar worry expressed in Sherman (2018).

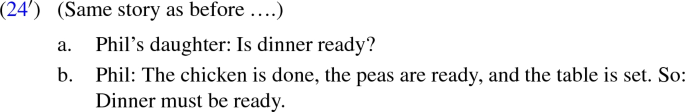

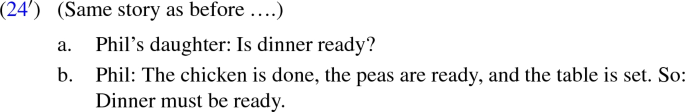

We note that a ‘#’ in (24a) is a little harsh, since minor adjustments can help a lot. For instance:

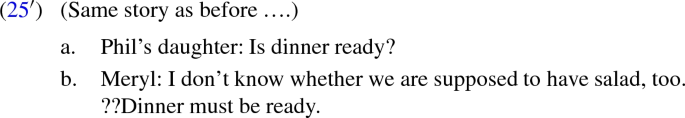

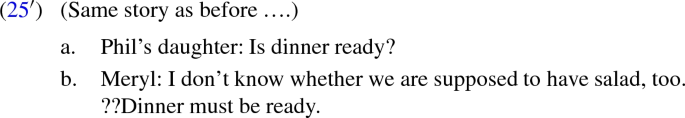

Similarly, we’re not so sure Meryl is in the clear in (25b). For instance, if she vocalizes her uncertainty about a salad:

Goodhue talks about a theory according to which having “identical perceptions” means having the same direct enough information. We take it this is just an example of a (doomed) analysis of direct enough information.

Compare von Fintel and Gillies (2010, 370, fn.29).

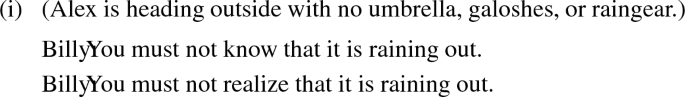

A reviewer suggests that with the addition of for sure, Alex’s response is improved. This may be so, but Billy’s sticking to her guns is still off.

Above we noted that the spectrum of non-borderline and borderline uses of must makes sense. Those reasons also cut against the thesis that must is only felicitous if the prejacent is unknown. Here’s why. Presented with collection \(C_{i+1}\) out of the blue, it’s definitely weird to say It must be a heap. But being presented with \(C_{i+1}\) and being told that \(C_i\) is a heap, it is fine to say that \(C_{i+1}\) must be a heap. If must required anti-knowledge it would then follow that while you know that \(C_i\) is a heap (because you were told), you don’t know that \(C_{i+1}\) is. This is exactly backwards from what makes vagueness hard: all those little bridge conditionals If \(C_i\) is a heap then \(C_{i+1}\) is a heap between adjacent collections seem obviously true (and known).

We could at this point insist that our version of a strong must does not in fact say that must-claims entail knowledge and certainty claims. Our gloss of must carefully used impersonal phrases such as it follows from the information that or worlds compatible with what is known. This is because of the widely known (but largely orthogonal to Karttunen’s Problem) feature of epistemic modality that it isn’t constrained to be speaker-ego-centric. We have commented on this phenomenon in our other work on epistemic modals (in particular von Fintel and Gillies 2007 and von Fintel and Gillies 2011). This interacts in interesting ways with the fact that must entails its prejacent, but we set these issues aside here.

We like to call this “Shatner’s Razor” for reasons we’re happy to reveal over a drink.

A reviewer notes that Ippolito (2018, 610–611) attempts to show that at least in the case of might, the evidential presupposition does not project as our theory would predict. We acknowledge that there is more to be said.

Whether this is achieved by invoking knowledge as the norm of assertion or some other way doesn’t matter for us.

Mandelkern goes on to argue that the novel pragmatic constraint requiring a mutually salient argument is itself amenable to a pragmatic derivation (via a manner implicature) and that the argument for that predicts that \(\textit{must} \, \phi \) amounts to a proposal to add \(\llbracket {\phi }\rrbracket \) to the common ground on the basis of a shared and mutually available argument. As an aside, we are skeptical about tying the upshot of \(\textit{must} \, \phi \) so closely to trying to coordinate everyone on \(\phi \). Some uses of \(\textit{must} \, \phi \) manifestly do not have this coordinating effect but even in such uses the evidential signal of indirectness remains.

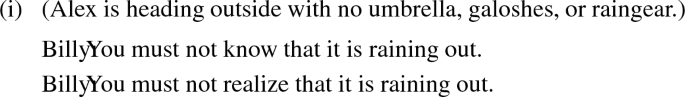

Billy is not trying to make it common ground between Alex and Billy that Alex doesn’t know that it is raining. In fact, the opposite. So drawing attention to a mutually salient and available argument in support of it would be self-defeating. Perhaps, as suggested to us by Angelika Kratzer, the official proposal can be amended by carefully balancing the time at which Alex doesn’t know that it is raining and the time at which the common ground is updated. Maybe so, but it seems tricky.

But wait, just because Holmes uses the contents of the notebook to rule out the gardener and narrow in on the butler and the driver, can’t his can’t and must point to a different argument? For instance, one that is constructable-on-the-fly to his audience that relies on the fact that Holmes consulted his notebook and used must? No. First, because the proposed pragmatic derivation requires that the argument is the speaker’s best evidence and not one based on the hearers trusting that the speaker has some private evidence for the prejacent. Second, because such on-the-fly arguments are too easily constructed, threatening to predict the acceptability of must in situations where it isn’t—including, for instance, in reporting Patch’s antics in (31b). (Thanks again to Angelika Kratzer for input on this.)

We note that Swanson (2008) (see esp. fn.14) argues that hardwiring the evidential signal may not be so bad after all. We’re not sure we agree with his particular reasons, but hey, we appreciate the support. Finally, we note that Matthewson and Truckenbrodt (2018) show subtle differences between English must and German müssen, which according to them argue in favor of a semantic hardwiring of the evidential requirement.

References

Del Pinal, Guillermo, and Brandon Waldon. 2019. Modals under epistemic tension. Natural Language Semantics 27 (2): 135–188. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-019-09151-w.

von Fintel, Kai. 2001. Counterfactuals in a dynamic context. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 123–152. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

von Fintel, Kai, and Anthony S. Gillies. 2007. An opinionated guide to epistemic modality. In Oxford studies in epistemology, vol. 2, ed. Tamar Szabó Gendle and John Hawthorne, 32–62. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

von Fintel, Kai, and Anthony S. Gillies. 2008. CIA leaks. The Philosophical Review 117 (1): 77–98. https://doi.org/10.1215/00318108-2007-025.

von Fintel, Kai, and Anthony S. Gillies. 2010. Must...stay...strong! Natural Language Semantics 18: 351–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-010-9058-2.

von Fintel, Kai, and Anthony S. Gillies. 2011. ‘Might’ made right. In Epistemic modality, ed. Andy Ega and Brian Weatherson, 108–130. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 1999. Affective dependencies. Linguistics and Philosophy 22 (4): 367–421. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005492130684.

Giannakidou, Anastasia, and Alda Mari. 2018. A unified analysis of the future as epistemic modality. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 36 (1): 85–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9366-z.

Gillies, Anthony S. 2007. Counterfactual scorekeeping. Linguistics and Philosophy 30 (3): 329–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-007-9018-6.

Goodhue, Daniel. 2017. Must\(\phi \) is felicitous only if \(\phi \) is not known. Semantics & Pragmatics 10 (14): 1–27. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.10.14.

Grice, Paul. 1967. Logic and conversation. Lecture Notes for William James lectures at Harvard University, published in slightly revised form in H.P. Grice, *Studies in the way of words*, pp. 1–43, Harvard University Press, 1989. 1–143.

Groenendijk, Jeroen A.G., and Martin J.B. Stokhof. 1975. Modality and conversational information. Theoretical Linguistics 2 (1/2): 61–112. https://doi.org/10.1515/thli.1975.2.1-3.61.

Ippolito, Michela. 2018. Constraints on the embeddability of epistemic modals. Sinn und Bedeutung (SuB) 21: 605–622.

Jacobson, Pauline. 2018. What is—or, for that matter isn’t—‘experimental’ semantics? In The science of meaning: Essays on the metatheory of natural language semantics, 46–72, ed. Derek Ball and Brian Raburn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1972. Possible and must. In Syntax and semantics, vol. 1, ed. John P. Kimball, 1–20. New York: Academic Press.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. Modality. In Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, ed. Arnim von Stechow and Dieter Wunderlich, 639–650. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Križ, Manuel. 2015. Homogeneity, non-maximality, and all. Journal of Semantics. https://doi.org/10.1093/jos/ffv006.

Kroch, Anthony. 1974. The semantics of scope in English. PhD thesis, MIT. 1721.1/13020.

Lasersohn, Peter. 1999. Pragmatic halos. Language 75 (3): 522–551. https://doi.org/10.2307/417059.

Lassiter, Daniel. 2016. Must, knowledge, (in)directness. Natural Language Semantics 24: 117–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-016-9121-8.

Lewis, David. 1979. Counterfactual dependence and time’s arrow. Noûs 13 (4): 455–476. https://doi.org/10.2307/2215339.

Lyons, John. 1977. Semantics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mandelkern, Matthew. 2016. A solution to Karttunen’s problem. Sinn und Bedeutung 21. http://users.ox.ac.uk/sfop0776/KarttSuB.pdf.

Mandelkern, Matthew. 2019. What must adds. Linguistics and Philosophy 42 (3): 225–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-018-9246-y.

Matthewson, Lisa, and Hubert Truckenbrodt. 2018. Semantic building blocks: Evidential epistemic modals in English, German and St’át’imcets. In Thoughts on mind and grammar: A festschrift in honor of Tom Roeper (UMOPL 41), ed. Bart Hollebrandse, Jaieun Kim, Ana T. Pérez-Leroux, and Petra Schulz, 89–100. Amherst, MA: GLSA.

Ricciardi, Giuseppe, Rachel Ryskin, and Edward Gibson. 2020. Epistemic must p is literally a strong statement. Poster presented at CUNY Sentence Processing Conference. https://osf.io/rwpag.

Sherman, Brett. 2018. Open questions and epistemic necessity. The Philosophical Quarterly 68 (273): 819–840. https://doi.org/10.1093/pq/pqy025.

Swanson, Eric. 2008. Modality in language. Philosophy Compass 3 (6): 1193–1207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1747-9991.2008.00177.x.

Veltman, Frank. 1985. Logics for conditionals. PhD thesis, University of Amsterdam. https://www.illc.uva.nl/cms/Research/Publications/Dissertations/HDS-02-Frank-Veltman.text.pdf.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We presented this material at the Ohio State Workshop on Modality on March 23, 2016, where our commentator Dan Lassiter provided useful pushback. Comments from students in an advanced semantics class at MIT helped immensely with some of our central arguments. We thank the two reviewers and the editors for incisive and valuable advice.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

von Fintel, K., Gillies, A.S. Still going strong. Nat Lang Semantics 29, 91–113 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09171-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09171-x