Abstract

In most cases, a wh-question calls for an answer that names an entity in the set denoted by the extension of the wh-complement. However, evidence from questions with necessity modals and questions with collective predicates argues that sometimes a wh-question must be interpreted with a higher-order reading, in which this question calls for an answer that names a generalized quantifier. This paper investigates the distribution and compositional derivation of higher-order readings of wh-questions. First, I argue that the generalized quantifiers that can serve as semantic answers to wh-questions must be homogeneously positive. Next, on the distribution of higher-order readings, I observe that questions in which the wh-complement is singular-marked or numeral-modified can be answered by elided disjunctions but not by conjunctions. I further present two ways to account for this disjunction–conjunction asymmetry. In the uniform account, these questions admit disjunctions because disjunctions (but not conjunctions) may satisfy the atomicity requirement of singular-marking and the cardinality requirement of numeral modification. In the reconstruction account, the wh-complement is syntactically reconstructed, which gives rise to local uniqueness and yields a contradiction for conjunctive answers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Elided disjunctions are scopally ambiguous relative to this commitment, as described in (i). This paper considers only the reading (ia). The other reading can be derived by accommodating the presupposition locally.

-

(i)

-

a.

Andy and Billy are math professors, and one of them left the party at midnight.

-

b.

Either Andy or Billy is a math professor who left the party at midnight.

-

a.

-

(i)

Disjunctions over set-denoting expressions are standardly treated as unions ‘\(\cup \)’. This idea follows a more general schema defined in Partee and Rooth (1983). Since entities are not sets, to be disjoined, they have to be first type-shifted into GQs of a conjoinable type \(\langle et, t\rangle \) via Montague-lift. Hence, in a disjunction of two referential DPs, or combines with two Montagovian individuals and returns their union (Keenan and Faltz 1985: Part 1A).

-

(i)

For any meaning \(\alpha \) of type \(\tau \), the Montague-lifted meaning is \(\alpha ^{\Uparrow }\) (of type \(\langle \tau t, t\rangle \)) such that \(\alpha ^{\Uparrow } =_{\text {df}} \lambda m_{\langle \tau , t\rangle }. m(\alpha )\).

The conjunctive and is commonly treated ambiguously as either an intersection operator ‘\(\cap \)’ (for combining sets, in analogy to the union meaning of or) or a summation operator ‘\(\oplus \)’ (for combining entities) (Link 1983; Hoeksema 1988). Another view is to interpret and uniformly and attribute the ambiguity to covert operations. For example, Winter (2001) and Champollion (2016b) treat and unambiguously as an intersection operator and use covert type-shifting operations to derive the summation-like reading.

-

(i)

For any \(\pi \) of type \(\langle \tau t, t\rangle \) and set A of type \(\langle \tau , t\rangle \), where \(\tau \) is an arbitrary type, we say that \(\pi \) lives on A if and only if for every set B: \(\pi (B) \Leftrightarrow \pi (B \cap A)\) (Barwise and Cooper 1981), and that \(\pi \) ranges over A if and only if A is the smallest live-on set (smlo) of \(\pi \) (Szabolcsi 1997). For example, the smallest live-on set of some/every/no student is the set of atomic students. These notions will be crucial for discussions on constraining what types of GQs should or should not be included in a Q-domain (see Sect. 3).

The definition of the combinatory operation ‘\(\bullet \)’ varies by the semantic type of the function \(\theta \). Let the GQ \(\pi \) be of type \(\langle \tau t, t\rangle \), where \(\tau \) is an arbitrary type. We then have the following: (i) if \(\theta \) is of type \(\langle \tau tt, t\rangle \), ‘\(\bullet \)’ stands for Forward Functional Application; (ii) if \(\theta \) is of type \(\langle \tau , t\rangle \), ‘\(\bullet \)’ stands for Backward Functional Application; (iii) if \(\theta \) cannot compose with a GQ directly, then either ‘\(\bullet \)’ involves a type-shifting operation or \(\theta \bullet \pi \) is undefined.

A predicate P is quantized if and only if whenever P holds for x, P does not hold for any proper subpart of x (Krifka 1997). Formally: \(\forall x \forall y [P(x) \wedge P(y) \rightarrow [x\le y \rightarrow x = y]]\). Defining predicates as sets of events, Champollion (2016a) argues that distributive readings are not available with quantized phrasal predicates because the extension of a quantized verbal phrase is not closed under summation formation.

The view of treating plurals as sets ranging over not only sums but also atomic elements is called the ‘inclusive’ theory of plurality (Sauerland et al. 2005, among others), as opposed to the ‘exclusive’ theory, which defines plurals as denoting sets consisting of only non-atomic elements. Whether plurals are treated as inclusive or exclusive is not crucial in this paper. The following presentation follows the inclusive theory.

Drawing on facts from Spanish quién ‘who.sg’, which is singular-marked but does not trigger uniqueness (Maldonado 2020), Elliott et al. (2020) by contrast propose that quién-questions admit also higher-order readings, in which the yielded Q-domain ranges over a set of Boolean conjunctions over atomic elements. Alonso-Ovalle and Rouillard (2019) argue against this view: as seen in (i), quién ‘who.sg’ can be used to combine with a stubbornly collective predicate like formó un grupo ‘formed.sg a group’, and the resulting question calls for the specification of the component members of one or more groups.

-

(i)

Quién formó un grupo?

who.sg formed.sg a group

‘Who formed a group?’

-

a.

Los estudiantes.

‘The students.’

-

b.

Los estudiantes y los profesores.

‘The students and the professors.’

-

a.

Answer (ib) has the conjunction reading that the students formed a group and the professors formed a group. The felicity of this answer shows that the quién-question admits answers naming Boolean conjunctions over non-atomic elements. Alonso-Ovalle and Rouillard thus conclude that quién is number-neutral in meaning and is semantically ambiguous: it ranges over either a set of atomic and non-atomic individuals or a set of Boolean conjunctions and disjunctions.

-

(i)

In contrast to my analysis, Fox (2020) assumes higher-order pluralities to account for the data in (22)/(28). He proposes to get rid of Dayal’s presupposition and accounts for the observed uniqueness effects based on his Question Partition Matching (QPM) principle. According to this principle, a singular-marked wh-question is only acceptable in context sets where its uniqueness presupposition is satisfied. Moreover, Fox argues that QPM can better account for the unavailability of higher-order readings in questions with a negative island, as well as for the modal obviation effects of higher-order readings in those questions.

-

(i)

Question Partition Matching (Fox 2018, 2020)

For any question with a Hamblin set Q, if it induces a partition P in a context set A, this question is acceptable in A if and only if: (i) every cell in P is identical to the exhaustification of a proposition in Q; and conversely (ii) every proposition p in Q is such that the exhaustification of p is identical to a cell in P.

The QPM principle, however, predicts that the wh-phrase in any non-modalized question cannot range over GQs. For example, if the question Who left? admits a higher-order reading, its Hamblin set should contain plain disjunctions such as

, which cannot be paired with any partition cell by exhaustification, violating QPM. To account for the absence of uniqueness in Which children formed a team?, Fox assumes that here which children ranges over a set of higher-order pluralities, not over a set of GQs. For example, in Fox’s account, the conjunctive answer \(a+b\) and \(c+d\) is interpreted as \(\{\{a, b\}, \{c, d\}\}\), not as \((a\oplus b)^{\Uparrow } \cap (c\oplus d)^{\Uparrow }\).

, which cannot be paired with any partition cell by exhaustification, violating QPM. To account for the absence of uniqueness in Which children formed a team?, Fox assumes that here which children ranges over a set of higher-order pluralities, not over a set of GQs. For example, in Fox’s account, the conjunctive answer \(a+b\) and \(c+d\) is interpreted as \(\{\{a, b\}, \{c, d\}\}\), not as \((a\oplus b)^{\Uparrow } \cap (c\oplus d)^{\Uparrow }\).-

(i)

Monotonicity of GQs is defined as follows:

-

(i)

For any \(\pi \) of type \(\langle et, t\rangle \):

-

a.

\(\pi \) is increasing if and only if \(\pi (A) \Rightarrow \pi (B)\) for any sets of entities A and B: \(A\subseteq B\);

-

b.

\(\pi \) is decreasing if and only if \(\pi (A) \Leftarrow \pi (B)\) for any sets of entities A and B: \(A\subseteq B\);

-

c.

\(\pi \) is non-monotonic if and only if \(\pi \) is neither increasing nor decreasing.

-

a.

-

(i)

The issues and proposals in Sect. 4 and Sect. 5 are independent from the findings in this section. Readers may choose to jump to the interim summary in Sect. 3.4.

The completeness-based test does not aim to fully characterize the truth conditions of a question-embedding sentence or to exhaustively determine what can or cannot be included in a Q-domain. First, this test is only concerned with one aspect of the truth conditions of question-embedding sentences, namely, the completeness condition. In addition to completeness, question-embeddings are also subject to a false-answer sensitivity condition. (Klinedinst and Rothschild 2011; George 2013; Cremers and Chemla 2016; Uegaki 2015; Xiang 2016a, b; Theiler et al. 2018; among others) For example, for sentence (34b) to be true, Sue can be ignorant about whether John should read any Russian novels, but she cannot have the false belief that John should read some Russian novel(s).

-

(i)

‘x knows Q’ is true if and only if

-

a.

x knows a/the complete true answer of Q; (Completeness)

-

b.

x does not have any false belief relevant to Q. (False-answer sensitivity)

-

a.

Second, the completeness-based test can only be used to determine what meanings should be excluded from a Q-domain, not what meanings should be included in a Q-domain. A bi-conditional characterization, namely, ruling in all the short answers that are not filtered out by the completeness-based test, could yield conflicting predictions. As I will show in Sect. 3.3, the completeness-based test shows that the higher-order Q-domain of the question What does John have to read? contains the non-monotonic quantifier exactly three books but not the decreasing quantifier less than four books, even though the propositional answer yielded by the former (i.e., John has to read exactly three books) asymmetrically entails the propositional answer yielded by latter (i.e., John has to read less than four books).

-

(i)

Strikingly, in contrast to (34b), the following two sentences with a concealed question or a definite description do imply that Sue knows both of John’s summer reading obligations listed in (34a).

-

(i)

-

a.

Sue knows what John’s summer reading obligations are.

-

b.

Sue knows John’s summer reading obligations.

-

a.

-

(i)

The illustration of the completeness-based test in (i) considers two more cases that involve GQ-disjunctions (underlined). This test further confirms that Boolean disjunctions involving a decreasing GQ-disjunct must be excluded from a Q-domain.

-

(i)

-

a.

Context: John’s summer reading obligations consist of the following:

-

i.

He has to read no leisure book or more than two math books. (In other words, John has to read more than two math books if he reads any leisure book.)

-

ii.

He has to read none or all of the Harry Potter books (because Harry Potter books must be rented in a bundle, and it would be a waste of money if he rents the entire series but only reads part of it).

-

i.

-

b.

Sue knows which books John has to read in the summer.

Sue knows (a-i)/(a-ii).

Sue knows (a-i)/(a-ii).

-

a.

-

(i)

The embedded question which cards John has to play also has a reading in which it admits all of the listed GQs, regardless of whether they are increasing, non-monotonic, or even decreasing. This reading is similar to what I observe with concealed questions and definite descriptions, as witnessed in footnote 13.

I call a GQ ‘simplex’ if it can be expressed as a single ‘D+NP’ phrase and ‘complex’ otherwise. For example, the GQ-coordination at least two books but no more than five books is simplex because it can be equivalently expressed as two to five books.

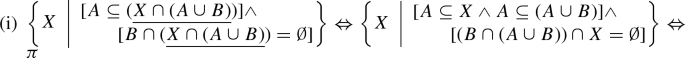

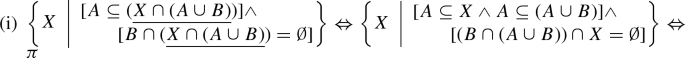

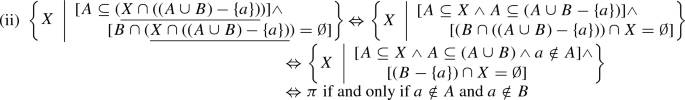

The following explains why \(A \cup B\) is the smallest live-on set of \(\pi \), where \(\pi = \{X \mid A \subseteq X \wedge B \cap X = \emptyset \}\). First, the equivalence in (i) shows that \(A \cup B\) is a live-on set of \(\pi \): replacing X with \(\underline{X \cap (A\cup B)}\) in the set description does not change the set.

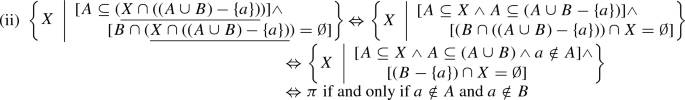

Next, the equivalence in (ii) shows that \(A \cup B\) is the smallest live-on set: for any a, replacing X with \(\underline{X \cap (A\cup B -\{a\})}\) in the set description makes no change to the set being defined if and only if \(a \not \in A \cup B\).

In an earlier version (Xiang 2019), treating positiveness and homogeneity as two separate conditions, I incorrectly claimed that any \(\pi \) of type \(\langle et, t\rangle \) can be decomposed into a conjunction \(\pi ^{+} \cap \pi ^{-}\) and proposed that \(\pi \) is homogeneous if \(\pi \) is monotonic or if \(\pi ^{+}\) and \(\pi ^{-}\) range over the same set. However, as pointed out by Lucas Champollion (pers. comm.), the equation \(\pi = \pi ^{+} \cap \pi ^{-}\) does not hold for disjoined GQs such as an even number of cards and two or four cards.

If a GQ \(\pi \) is unbound, then one or both of the strongest GQs retrieved from \(\pi \) are trivial (viz., equivalent to \(D_{\langle e,t\rangle }\)), ranging over the discourse domain \(D_{e}\). In particular, increasing GQs are upper-unbound, and decreasing GQs are lower-unbound.

-

(i)

-

a.

If \(\pi \) is upper-unbound, i.e., \(\forall P [P \in \pi \rightarrow \exists P'\in \pi [P'\supseteq P]]\), then \(\pi ^{-} = D_{\langle e, t\rangle }\). Examples: at least two books, an even number of books, less than two or more than four books

-

b.

If \(\pi \) is lower-unbound, i.e., \(\forall P [P \in \pi \rightarrow \exists P'\in \pi [P'\subseteq P]]\), then \(\pi ^{+} = D_{\langle e, t\rangle }\). Examples: less than two or more than four books, at most four books

-

a.

-

(i)

A puzzle arises with non-monotonic GQ-coordinations such as some book but no leisure book, where the set that the coordinated decreasing GQ ranges over (viz., the set of leisure books) is a proper subset of the set that the coordinated increasing GQ ranges over (viz., the set of books). In (i), telling John that he has to read a book is clearly insufficient — John might incorrectly think that reading a leisure book suffices for his reading requirement. It is appealing to say that the question-embedding sentence (i) entails both (ia) and (ib), and that the complete answer to the embedded question names the GQ-coordination some book but no leisure book. However, this GQ-coordination is not homo-positive: it does not entail existence with respect to the set of leisure books.

-

(i)

(Context: John has to read a book, but he is not allowed to read any leisure books.) Sue will tell John what he has to read.

-

a.

Sue will tell John that he has to read a book.

-

b.

Sue will tell John that he cannot read any leisure books.

-

a.

I argue that the Homo-Positive-GQ Constraint still holds here. In the given scenario, the completeness condition of the embedding sentence (i) should be (ic), which is stronger than (ia) and weaker than the conjunction of (ia) and (ib). The GQ that serves as the complete true short answer to what John has to read is some non-leisure book, which is homo-positive.

-

(i)

-

c.

Sue will tell John that he has to read a non-leisure book.

-

c.

-

(i)

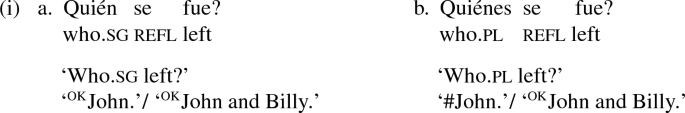

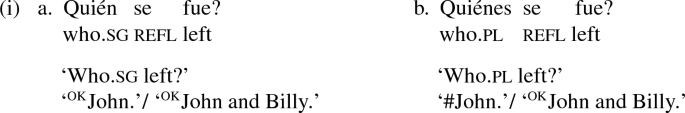

This claim holds regardless of whether plurals are treated inclusively or exclusively. I also assume that the bare wh-words who and what have a structure similar to which people/things. Alternatively, one can treat [pl] as a predicate restrictor that asserts/presupposes/anti-presupposes non-atomicity (see also footnote 6). The latter option is more suited for languages in which plural-marking is not vacuous. For example, Spanish bare wh-words can be singular-marked or plural-marked. Interestingly, as seen in (i), while the singular form admits both atomic and non-atomic answers (see also footnote 7), the plural form admits only non-atomic answers (Maldonado 2020). For languages with non-vacuous plural-marking, it is plausible to assume that the the singular morpheme is semantically neutral, while the plural morpheme asserts/presupposes non-atomicity (Alonso-Ovalle and Rouillard 2019; cf. Elliott et al. 2020).

The conjunctive continuation in (54a) is intuitively more acceptable than the conjunctive continuation in (53a), as pointed out by Gennaro Chierchia (pers. comm.). A reviewer of Natural Language Semantics also reported that they found no clear contrast between (54a) and (54b). One possible explanation of the improvement in (54a) is that the numeral modifier two alone can be reconstructed to the nucleus, which yields a simple plural-marked question roughly read as ‘Which books are two books that John has to read?’.

Fox (2020) disagrees with Gentile and Schwarz’s conjecture. He argues that how many-phrases can range over higher-order conjunctions of degrees/intervals, in light of the following data:

-

(i)

How high are we not allowed to fly?Below 50 meters (too low) and above 2000 meters (too high). (\({ and} \gg \lnot \gg \Diamond \))

I don’t think the above example can knock down Gentile and Schwarz’s conjecture. The information conveyed by the above conjunctive answer can even more preferably be expressed as a narrow-scope disjunction, namely, below 50 meters or above 2000 meters (\(\lnot \gg \Diamond \gg { or}\)). To argue against Gentile and Schwarz (2018), one would have to find a case where the strongest true answer can and must be expressed as a higher-order conjunction over degrees/intervals. For example, in a context where the only group work constraint is that we cannot have two students work together while simultaneously another three students work together, the strongest true answer to the following negative \(\Diamond \)-question, if available, would have to be a narrow-scope conjunction. However, as seen in (ii), this conjunctive answer does not appear felicitous.

-

(ii)

How many students are not allowed solve this problem together?# Two and three.(Intended: ‘It is not allowed that [two students solve the problem together and simultaneously (another) three students solve this problem together].’)

-

(i)

Witness sets are defined in terms of the living-on property as follows (Barwise and Cooper 1981): if a GQ \(\pi \) lives on a set B, then A is a witness set of \(\pi \) if and only if \(A \subseteq B\) and \(\pi (A)\). For example, given a discourse domain including three students a,b,c, the universal quantifier every student has a unique minimal witness set \(\{a, b, c\}\), while the singular existential quantifier some student has three minimal witness sets \(\{a\}\), \(\{b\}\), and \(\{c\}\), each of which consists of one atomic student.

Given that it is possible to account for the uniqueness effects with singular-marked and numeral-modified wh-phrases while assuming a higher-order reading, one might propose that wh-questions do not have first-order readings at all. At this point I do not see any direct evidence for first-order readings of questions. However, denying their existence outright would lead to the prediction that the application of the h-shifter is mandatory, which is conceptually problematic. The presence of the h-shifter should be independent from the wh-determiner since it is applied locally to the root nP; thus if the h-shifter were mandatory, we would expect that any NP has only a higher-order reading. However, in the student for example, the complement of the has to be interpreted as a set of entities, not as a set of GQs.

Luis Alonso-Ovalle (pers. comm.) points out that the assumed local uniqueness inference might be too strong for \(\Box \)-questions. For example, the question–answer pair in (i) can be felicitously uttered in a context where it is taken for granted that to win the game, one needs a pair of matching cards—either red aces or black aces—but this alone does not guarantee a win.

-

(i)

Which two cards do you need to win the game?The two red aces or the two black aces.

I argue that the local uniqueness inference in (i) is assessed dynamically relative to an updated context, namely, the context where the player has a bunch of cards in hand and only needs two more cards to close the game.

-

(i)

One might have concerns with the assumed syntax for reconstruction. On the one hand, the assumed the-insertion and variable insertion are similar to the operations of determiner replacement and variable insertion used in trace conversion (Fox 2002), especially backward trace conversion (Erlewine 2014). On the other hand, in trace conversion, the-insertion and determiner replacement are locally applied to the moved DP which book, while in my proposal, the-insertion and variable insertion apply to a larger constituent DP+VP which book John read. I admit that the structure used for such derivation is unconventional, but this is not necessarily a problem for considering (76) as the structure that derives the ‘conjunction-rejecting’ reading. As seen in Sect. 5.1, this reading itself is a bit unnatural. It is much harder to obtain than the conjunction-admitting reading, especially in question-embeddings (see (53), (54), and (57)). Thus it is likely that the derivation of this reading requires abnormal operations, and it is possible that the structure used for deriving this reading is not the real LF of the question under discussion.

I assume a locality constraint to the effect that the variable introduced by variable insertion has to be directly bound by the wh-phrase. With this assumption, in the LF for the higher-order reading, variable insertion introduces a higher-order variable \(\pi \). By contrast, the structure in (i), where variable insertion (underlined) introduces an individual variable x bound by the higher-order wh-trace, is ruled out.

-

(i)

*[ whP \(\lambda \pi _{\langle et, t\rangle }\) [ have-to [ \(\pi \) \(\lambda x_{e}\) [ \(\underline{\lambda y. x = y}\) [ the [ which book John read ]]]]]

This constraint avoids unattested split-scope readings of conjunctive answers to questions with an existential quantifier. Observe that the singular-marked question in (ii) cannot be felicitously responded to by a conjunction. The infelicity of the conjunctive answer suggests that this answer cannot be interpreted with a split-scope reading such as ‘For a math problem \(x_1\), Andy is the unique student who solved \(x_1\), and for a math problem \(x_2\), Billy is the unique student who solved \(x_2\)’ (\({ and} \gg \exists \gg \iota \)). The unavailability of this reading suggests ruling out the LF in (iib) where the existential quantifier a math problem takes scope between the higher-order trace \(\pi \) and the inserted the.

-

(ii)

Which student solved a math problem?# Andy and Billy. (\(\textit{and} \gg \iota \gg \exists \))

-

a.

[ whP \(\lambda \pi _{\langle et, t\rangle }\) [ \(\underline{\lambda y. \pi (\lambda x.x = y)}\) [ the [ which student solved a math problem ]]]]

-

b.

*[ whP \(\lambda \pi _{\langle et, t\rangle }\) [ \(\pi \) \(\lambda x_{e}\) [ a-math-problem \(\lambda z\) [ \(\underline{\lambda y. x = y}\) [ the [ which student solved z ]]]]]]

-

a.

-

(i)

In both structures, an exhaustivity operator ‘O’ (\(\approx \) only) is inserted under the possibility modal and is associated with the individual wh-trace x.

-

(i)

\(O_{C} =\lambda p \lambda w. p(w) = 1 \wedge \forall q \in C [p \not \subseteq q \rightarrow q(w) = 0]\) (Chierchia et al. 2012)(For any proposition p and world w, \(O_{C}(p)\) is true if and only if p is true in w, and any proposition in C that is not entailed by p is false in w.)

In Xiang 2016b, I propose that the MS-reading arises if the higher-order wh-trace \(\pi \) scopes below the possibility modal. The local O-operator is assumed to account for the facts that MS-answers are always mention-one answers, and that any answer that names one feasible option is a possible MS-answer. These issues are beyond the scope of this paper.

-

(i)

There is a rich literature on the semantics of dou, but very few analyses can account for the widely discussed distributor use and the even-like use of dou while also explaining its free-choice-triggering effect in declarative sentences. Besides the account of Xiang (2016b, 2020) adopted here, another possible candidate is Liu 2016. Although Liu (2016) does not discuss free-choice disjunctions in particular, his analysis predicts the mandatory use of pre-/recursive exhaustifications in the presence of dou. See Xiang 2020 for a review.

References

Alonso-Ovalle, Luis, and Vincent Rouillard. 2019. Number inflection, Spanish bare interrogatives, and higher-order quantification. In Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 49, ed. Maggie Baird, and Jonathan Pesetsky, 25–38. Amherst, MA: GLSA. http://people.linguistics.mcgill.ca/~luis.alonso-ovalle/papers/AlonsoOvalle_Rouillard.pdf.

Barwise, Jon, and Robin Cooper. 1981. Generalized quantifiers and natural language. Linguistics and Philosophy 4(2): 159–219.

Champollion, Lucas. 2016a. Covert distributivity in algebraic event semantics. Semantics and Pragmatics 9: 1–65.

Champollion, Lucas. 2016b. Ten men and women got married today: Noun coordination and the intersective theory of conjunction. Journal of Semantics 33(3): 561–622.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2006. Broaden your views: Implicatures of domain widening and the “logicality” of language. Linguistic Inquiry 37 (4): 535–590.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 2013. Logic in grammar: Polarity, free-choice, and intervention. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chierchia, Gennaro, Danny Fox, and Benjamin Spector. 2012. The grammatical view of scalar implicatures and the relationship between semantics and pragmatics. In An international handbook of natural language meaning, ed. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner, 2297–2332. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Cremers, Alexandre, and Emmanuel Chemla. 2016. A psycholinguistic study of the exhaustive readings of embedded questions. Journal of Semantics 33(1): 49–85.

Cresti, Diana. 1995. Extraction and reconstruction. Natural Language Semantics 3: 79–122.

Dayal, Veneeta. 1996. Locality in WH quantification: Questions and relative clauses in Hindi. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Elliott, Patrick D, Andreea C Nicolae, and Uli Sauerland. 2020. Who and what do who and what range over cross-linguistically. Manuscript, ZAS Berlin (Leibniz-Center of General Linguistics). https://ling.auf.net/lingbuzz/003959.

Erlewine, Michael Yoshitaka. 2014. Movement out of focus. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Fox, Danny. 2002. Antecedent-contained deletion and the copy theory of movement. Linguistic Inquiry 33 (1): 63–96.

Fox, Danny. 2013. Mention-some readings. MIT seminar notes. http://lingphil.mit.edu/papers/fox/class1-3.pdf.

Fox, Danny. 2018. Partition by exhaustification: Comments on Dayal 1996. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 22, ed. Uli Sauerland and Stephanie Solt, 403–434. Berlin: Leibniz-Centre General Linguistics. https://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/jQ5MTcyZ/.

Fox, Danny. 2020. Partition by exhaustification: Towards a solution to Gentile and Schwarz’s puzzle. Manuscript, MIT. https://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/TljZGNjZ/

Gentile, Francesco, and Bernhard Schwarz. 2018. A uniqueness puzzle: How many-questions and non-distributive predication. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 21, ed. Robert Truswell, Chris Cummins, Caroline Heycock, Brian Rabern, and Hannah Rohde, 445–462. University of Edinburgh. https://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/DRjNjViN/SuB21.pdf.

George, B.R. 2013. Knowing-‘wh’, mention-some readings, and non-reducibility. Thought: A Journal of Philosophy 2: 166–177.

Groenendijk, Jeroen, and Martin Stokhof. 1984. On the semantics of questions and the pragmatics of answers. Varieties of Formal Semantics 3: 143–170.

Harbour, Daniel. 2014. Paucity, abundance, and the theory of number. Language 90(1): 185–229.

Hausser, Roland R. 1983. The syntax and semantics of English mood. In Questions and answers, ed. Ferenc Kiefer, 97–158. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Hausser, Roland, and Dietmar Zaefferer. 1979. Questions and answers in a context-dependent Montague grammar. In Formal semantics and pragmatics for natural languages, ed. Franz Guenthner and Siegfried J. Schmidt, 339–358. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Heim, Irene. 1994. Interrogative semantics and Karttunen’s semantics for know. In The Proceedings of the 9th Annual Conference of the Israel Association for Theoretical Linguistics (IATL) and of the Workshop on Discourse, ed. Rhonna Buchalla and Anita Mitwoch, volume 1, 128–144. Jerusalem: IATL. https://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/jUzYjk1O/Interrogative%2094.pdf.

Hirsch, Aron, and Bernhard Schwarz. 2019. Singular which, mention-some, and variable scope uniqueness. Poster presented at the 29th Semantics and Linguistic Theory, University of California, Los Angeles, May 2019.

Hirsch, Aron, and Bernhard Schwarz. 2020. Singular which, mention-some, and variable scope uniqueness. In Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory 29, ed. Katherine Blake, Forrest Davis, Kaelyn Lamp, and Joseph Rhyne, 748–767. Washington, D.C.: LSA. https://journals.linguisticsociety.org/proceedings/index.php/SALT/article/view/29.748.

Hoeksema, Jack. 1988. The semantics of non-Boolean “and”. Journal of Semantics 6(1): 19–40.

Jacobson, Pauline. 2016. The short answer: Implications for direct compositionality (and vice versa). Language 92(2): 331–375.

Keenan, Edward L., and L.M. Faltz. 1985. Boolean semantics for natural language. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Klinedinst, Nathan, and Daniel Rothschild. 2011. Exhaustivity in questions with non-factives. Semantics and Pragmatics 4: 1–23.

Krifka, Manfred. 1997. The expression of quantization (boundedness). Presentation at the Workshop on Cross-linguistic Variation in Semantics. LSA Summer Institute, Cornell University.

Link, Godehard. 1983. The logical analysis of plurals and mass terms: A lattice-theoretical approach. In Meaning, use, and interpretation of language, ed. Christoph Schwarze, Rainer Bäuerle, and Arnim von Stechow, 302–323. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Liu, Mingming. 2016. Varieties of alternatives: Mandarin focus particles. Linguistics and Philosophy 40: 61–95.

Maldonado, Mora. 2020. Plural marking and d-linking in Spanish interrogatives. Journal of Semantics 37 (1): 145–170.

Partee, Barbara, and Mats Rooth. 1983. Generalized conjunction and type ambiguity. In Meaning, use, and interpretation of language, ed. Rainer Bäuerle, Christoph Schwarze, and Arnim von Stechow, 334–356. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Rullmann, Hotze. 1995. Maximality in the semantics of wh-constructions. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Rullmann, Hotze, and Sigrid Beck. 1998. Presupposition projection and the interpretation of which-questions. In Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory 8, ed. Devon Strolovitch and Aaron Lawson, 215–232. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications. https://journals.linguisticsociety.org/proceedings/index.php/SALT/article/view/2811.

Sauerland, Uli. 2003. A new semantics for number. In Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory 13, ed. Robert B. Young and Yuping Zhou, 258–275. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications. https://journals.linguisticsociety.org/proceedings/index.php/SALT/article/view/2898.

Sauerland, Uli, Jan Anderssen, and Kazuko Yatsushiro. 2005. The plural is semantically unmarked. In Linguistic evidence: Empirical, theoretical, and computational perspectives, ed. Stephan Kepser and Marga Reis, 413–434. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Scontras, Gregory. 2014. The semantics of measurement. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University.

Sharvy, Richard. 1980. A more general theory of definite descriptions. The Philosophical Review 89(4): 607–624.

Spector, Benjamin. 2007. Modalized questions and exhaustivity. In Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory 17, ed. M. Gibson and T. Friedman, 282–299. Ithaca, NY: CLC Publications. https://journals.linguisticsociety.org/proceedings/index.php/SALT/article/view/2962.

Spector, Benjamin. 2008. An unnoticed reading for wh-questions: Elided answers and weak islands. Linguistic Inquiry 39(4): 677–686.

Srivastav, Veneeta. 1991. WH dependencies in Hindi and the theory of grammar. Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1997. Background notions in lattice theory and generalized quantifiers. In Ways of scope taking, ed. Anna Szabolcsi, 1–27. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Theiler, Nadine, Floris Roelofsen, and Maria Aloni. 2018. A uniform semantics for declarative and interrogative complements. Journal of Semantics 35(3): 409–466.

Uegaki, Wataru. 2015. Interpreting questions under attitudes. Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Uegaki, Wataru. 2018. On the projection of the presupposition of embedded questions. In Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory 28, ed. Sireemas Maspong, Brynhildur Stefánsdóttir, Katherine Blake, and Forrest Davis, 789–808. Washington, D.C.: LSA. https://journals.linguisticsociety.org/proceedings/index.php/SALT/article/view/28.789.

Uegaki, Wataru. 2020. The existential/uniqueness presupposition of wh-complements projects from the answers. Linguistics and Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-020-09309-4.

Winter, Yoad. 2001. Flexibility principles in Boolean semantics: The interpretation of coordination, plurality, and scope in natural language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Xiang, Yimei. 2016a. Complete and true: A uniform analysis for mention-some and mention-all. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 20, ed. Polina Berezovskaya Nadine Bade and Anthea Schöller, 815–830. University of Tüebingen. https://semanticsarchive.net/sub2015/SeparateArticles/Xiang-SuB20.pdf.

Xiang, Yimei. 2016b. Interpreting questions with non-exhaustive answers. Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University.

Xiang, Yimei. 2019. Two types of higher-order readings of wh-questions. In Proceedings of the 22nd Amsterdam Colloquium, ed. Julian J. Schlöder, Dean McHugh, and Floris Roelofsen, 417–426. Amsterdam: ILLC. http://events.illc.uva.nl/AC/AC2019/uploaded_files/inlineitem/Xiang_Two_types_of_higher-order_readings_of_wh-ques.pdf.

Xiang, Yimei. 2020. Function alternations of the Mandarin particle dou: Distributor, free-choice licensor, and ‘even’. Journal of Semantics 37(2): 171–217.

Acknowledgements

This paper significantly expands on Xiang 2019, published in Proceedings of the 22nd Amsterdam Colloquium. For helpful discussions, I thank Luis Alonso-Ovalle, Lucas Champollion, Gennaro Chierchia, Danny Fox, Michael Glanzberg, Manuel Križ, Floris Roelofsen, Vincent Rouillard, Benjamin Spector, Bernhard Schwarz, and the audiences at the Spring 2019 Rutgers Seminar, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Ecole Normale Supérieure, and the 22nd Amsterdam Colloquium. I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers of Natural Language Semantics, whose comments led to notable improvements, and to Christine Bartels for her masterful editorial work. All errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Xiang, Y. Higher-order readings of wh-questions. Nat Lang Semantics 29, 1–45 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09166-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11050-020-09166-8

, which cannot be paired with any partition cell by exhaustification, violating QPM. To account for the absence of uniqueness in Which children formed a team?, Fox assumes that here which children ranges over a set of higher-order pluralities, not over a set of GQs. For example, in Fox’s account, the conjunctive answer

, which cannot be paired with any partition cell by exhaustification, violating QPM. To account for the absence of uniqueness in Which children formed a team?, Fox assumes that here which children ranges over a set of higher-order pluralities, not over a set of GQs. For example, in Fox’s account, the conjunctive answer  Sue knows (a-i)/(a-ii).

Sue knows (a-i)/(a-ii).