Beatriz Eugenia Navarro Cira, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo, Mexico

Isabel Carrillo López, Universidad Autonoma de Queretaro, Mexico.

Navarro Cira, B. E., & Carillo López, I. (2020). COVID-19, a breakthrough in educational systems: Keeping the development of language learners’ autonomy at Self-Access Language Centres. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 11(3), 220–234. https://doi.org/10.37237/110309

Abstract

This article presents two flexible operational process models (OPM) that could serve as guidelines for a self-access language centre (SALC) in the provision of advising services and workshops not only at difficult times such as the one caused by COVID-19, but also on a regular basis. The aim of the models is to provide a vision to plan, monitor, evaluate and improve the processes involved in the provision of the above mentioned services which have been described by a number of authors as approaches to fostering autonomy in language learners. Tassinari (2010) sees these two approaches at SALCs as a way to offer support and guidance for learners on their path towards autonomy. The OPMs presented in this paper include a reconsideration of the relationships between the implementation of a quality management system (QMS) offered by the International Organization for Standardization (IOS) and the processes involved in the planning, monitoring and eventually evaluating the steps involved in the enhancement of learner autonomy and language learner competence in a SALC. Keeping in mind that if a SALC opts to implement a quality approach in the provision of their services, it will require a fundamental transformation in its managerial strategies, not only to obtain a quality award, but also if they choose to improve their management processes related to the provision of its services as well.

Keywords: quality management system, learner autonomy, language competence

A novel coronavirus or COVID-19 has transformed the lives of millions. New social, educational, and economic rules were set in order to preserve the lives of millions—one of these measures has impacted educational systems. Governments around the world have temporarily closed educational institutions in an attempt to contain the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. 143 countries have completely closed their schools from pre-primary to tertiary education levels. Nationwide closures have impacted over 60% of the world’s student population, affecting around 1,184,126,508 learners (UNESCO, 2020). In response to school closures and to minimise the disruption of education, UNESCO (2020) recommended the use of distance learning programs endorsing the use of applications and platforms that can be used remotely to assure that students at any level should continue receiving classes, then homes needed to be adapted as schools.

We never could have imagined that in the 21st century, a series of dramatic restrictions such as “stay-home” imposed by the governments around the world to prevent countless deaths would have provided the opportunity for many of the SALCs in Mexico to re-think, re-plan, and re-do its working methodology to keep providing services at the centres. For instance, Escuela Nacional de Lenguas Lingüistica y Traducción (ENALLT, 2020) organised a virtual conference with the purpose of sharing experiences on how different SALCs in Mexico have faced COVID-19 challenges.

The information presented in this article is part of an ongoing doctoral research study analysing the impact of a quality management system (QMS) applied to a SALC. The study assesses quality assurance in the processes involved in the provision of at least two of the services delivered at a SALC to enhance autonomy in language learners as well as improve their language competence. The main aim of this paper is to propose two dedicated and flexible operational process models (OPMs) appropriate to the needs of a SALC which could be used and adapted by other SALCs according to their particular context. These OPMs will be supported by International Organization for Standardization (IOS) QMS principles—specifically a system called ISO 9001:2015—thus permitting the identification of the processes associated with the development of language learner autonomy in support of language learning in a SALC environment.

These OPMs intend to provide any SALC with a series of guidelines that allow them to plan the activities, to face uncertainties, and to consider the risks which could impede the delivery of the services in a SALC. Mainly, this paper aims to present two models that were designed to fit into the ongoing work at a SALC in the provision of two of its main services: advisory sessions and learning workshops.

Background

This research takes place at Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, a large state university in the western part of Mexico to the south of Mexico City. This paper is an ongoing case study taking place in the university’s SALC. This SALC provides services to students enrolled in the languages department as well as the university community in general. The centre offers a variety of learning materials on different languages which includes Arabic, Chinese, English, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Latin, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish L2 and the indigenous mother tongue from Michoacán called P’urhépecha. At the centre, some regular practices include an orientation session at the beginning of each academic term, advising sessions and workshops.

A quality assurance programme has regulated the services provided at this SALC. For more than a decade, the IOS (ISO 9000) standards and principles have underpinned the organisation of the centre. This paper presents the two flexible OPMs which are aimed at serving as a reference for establishing or updating the services provided at the SALC and that might potentially be adapted by other centres. The two models presented here were designed to cope with the urgent need of providing and accompanying SALC users with online activities to maintain the SALC as an option to improve their autonomous learning skills and to enhance their language learner competence.

Literature Review

Autonomy in Language Learning

The concept of autonomy has been extensively discussed since Holec (1981) first presented the concept of learner autonomy as “the ability to take charge of one’s learning” (p. 7) and that people succeed as autonomous learners when they can freely select their learning objectives to set goals. Since then many authors have made contributions to enriching the scope of the concept (e.g., Benson, 1997; Gardner & Miller, 1999; Holec, 1981; Little, 1999; Morrison, 2002; Mynard, 2011; Nunan, 1997; Oxford, 1990; Reinders, 2010; Scharle & Szabó, 2001).

According to Riley (1987) autonomy is “the capacity to initiate and successfully manage one’s own learning programme” (p. 35). For him, autonomy also incorporates the learner’s ability to identify learning needs, define objectives, obtain materials, select study techniques, and evaluate progress; in other words, to learn how to learn. Everhard (2018) also discusses the concept of autonomy to the extent of knowing how to learn and which resources and strategies learners are to use, such as thinking deeply about their learning process; working and communicating with others, and managing their motivation and emotional states. Additionally, Huang (2009) considers that learner autonomy should be analysed from several standpoints, such as technological, psychological, socio-cultural and political. Benson (2001) concludes that learner autonomy is a multidimensional capacity which could “take different forms for different individuals and even for the same individual in different contexts or at different times” (p. 47).

E-learning

As Hartshorne and Haya (2009) have pointed out, the move towards e-learning has provided important channels of communication for both teachers and learners. During the COVID-19 pandemic, this has proven to be especially important given the restrictions around avoiding personal contact in the classroom. The OECD (2005) defines the inclusion of e-learning in higher education as a mixture of teaching-learning method since it could include the usage of information through the utilisation of technology to enhance online learning or as a complement to traditional classrooms. This definition has opened the debate around the accuracy of the definition. To Hartshorne and Haya (2009), e-learning embraces the use of the internet to produce teaching and learning materials, while to Fry (2001), it could help to regulate courses in an organisation. Wentling et al. (2000) refer to e-learning as the use of knowledge that is predominantly facilitated and distributed by electronic means. Similarly, DeBlois and Maltz (2005) refer to e-learning as the use and distribution of materials for online-distance learning as well as hybrid learning. One of the models introduced in this paper refers to the use of online activities as a learning resource in virtual learning environments.

Quality in Education

Quality is a term that is present in many different fields for various purposes, and education is no exception. UNESCO (2005), Peters and Waterman (1992), and Doherty (1994) claim that quality is not limited to one sector; its approach can be applied to other fields such as health care, non-profit organisations, government, and education.

Several authors, such as Feingenbaum (1983), Crosby (1984), Gilmore (1974), Parasuraman et al. (1985), and Doherty (1994) have made significant contributions to reaching a standardised definition of quality in education. They see the quality in higher education as a way to pursue excellence, values, and requirements.

Even though QMS can be seen as a bureaucratic systematisation of educational processes, Twigg (2001) states that although they are not perfect, and they can certainly be improved, they work reasonably well for many institutions, states, and federal governments. The concept of quality in this research is aligned with the ISO 9000 standard which sees quality as a resource that provides confidence in the organization’s ability to provide products that fulfil customer needs and expectations (IOS, 2012). Hoyle (2009) describes the purpose of ISO 9000 standards as to assist organizations of all types to implement and operate effective quality management systems.

An Action Plan for the SALC in Times of COVID-19

This section presents the two models designed and implemented at this SALC—the site of the research—in order to keep offering two of the main services which are regularly provided at the centre. As stated in the centre’s mission statement:

We contribute to the essential formation of our university students and the society in general, through a process of self-directed language learning. We offer a quality service through the inclusion of new technologies, materials, equipment and academic support, which encourage the learner to build their knowledge in an active, responsible, and independent way.

Keeping this mission statement in mind, offering a quality service through the inclusion of new technologies and academic support, the SALC implemented an e-learning methodology to maintain a virtual presence in order to ensure that the Centre could be part of this sudden new teaching-learning approach, whereas for this SALC at least, all main activities had always been done face to face. As the centre maintains quality by ISO 9000 standards, it was necessary to design a model which copes with the regulations of the QMS and also to serve academic purposes.

Advising Model

One of the services usually offered at SALCs is language advising. Carson and Mynard (2012) and Kato and Mynard (2016) describe this process as a one-to-one intentional dialogue between a teacher/advisor and a learner and the purpose is to promote deep reflection on learning and, ultimately, learner autonomy. Mozzon-McPherson (2001) and Reinders (2008) define language advising as to the process in which the main goal is the development of learner autonomy which includes fostering the ability in learners to identify language needs by selecting appropriate resources, planning, monitoring and evaluating.

Therefore, considering the importance language advising has in promoting the development of learner autonomy and as a result of the restriction of personal contact due to the COVID19 pandemic, it was decided to keep providing advising sessions. This enabled us to make students feel that, in times of turbulence, there was still an opportunity for them to continue working. Sheerin (1997) states that the process of becoming autonomous does not necessarily happen in isolation and teachers have a crucial role in helping students to become more autonomous. This is likely to include the use of SALCs which are places that provide opportunities for learners to explore language and develop their own learning strategies (Gardner & Miller, 1999).

The following flow chart (Figure 1) was designed and adapted as an emergent model based on a main OPM and the principles established by the ISO: 9001:2015. As has been previously explained, the ISO 9001 is an international standardised set of regulations or QMS which has the intention of helping organisations to analyse, control and improve their internal processes. This is the reason why the advising model and the online activities model considered the principles and policies established in ISO 9001:2015 the norm. These policies present a series of protocols which are to be considered when establishing the process to provide a service which includes: resources, support, service provision, evaluation, processes improvement. In addition, it accounts for potential risks that might prevent the organisation, in this case a SALC, from providing services. Figure 1 describes the process advisors from the SALC needed to follow in order to keep providing the advising service.

Figure 1

Advising Model

The first step was to define the input and output. In this case, the input and the output refer to the understanding of the needs and expectations of the interested parties (students, advisors, and managerial staff). Then it was necessary to set the objective of this activity which was to keep providing advising and to keep helping students to reflect on the advantages of being an autonomous learner. At this point, it is important to mention that the person in charge of organising the SALC activities (manager, coordinator, administrator, etc.) is responsible for planning and leading the proposed activities, to assure quality of the provided services, but overall to lead and support all the people involved in the provision of the services (advisors and staff).

The management process and the service realization were the ones which were set to fully provide the service. The interested parties, quality assurance committee team and the advisors will meet to discuss and analyse the results of the implemented methodology in the centre, and if necessary, to make changes to the processes in order to improve the quality of the services.

Online Activities

According to Mynard and Sorflaten (2003), there are different ways a teacher can motivate and facilitate autonomous learning through learner training in class. They also state that, more than making students work independently, students should be assisted to develop skills that could help them to become good learners, to take responsibility for their learning and to be able to apply these skills into any new learning situation. Alongside this, Mozzon-McPherson (1999) mentions that students are responsible for their practice. On the other hand, it is the advisors’ responsibility to facilitate the learner-specific and more generic language learning strategies, such as time management, communication strategies and goal setting, and to encourage students to become more effective and more autonomous language learners (Carson & Mynard, 2012). In this sense, Holmes and Gardner (2006) state that e-learning in education focuses more on learners by way of interactivity, cultural diversity and globalization, and eradicating boundaries of place and time.

Online Activities Alignments (see Table 2)

The model presented in the next flowchart (Figure 2) might serve as a guideline to plan and design the proposed learning activities.

- The activities must be planned to encourage the development of linguistic competences and enhance learner autonomy.

- Advisors can choose three ways to plan the support materials:

- The advisor can record a video clip or use a recorded PowerPoint presentation of no more than 5 minutes, where he/she explains the objective of the activity, the activities suggested for the user and a link to access the designed materials. The user will be invited to leave a comment about their experience when carrying out the activity.

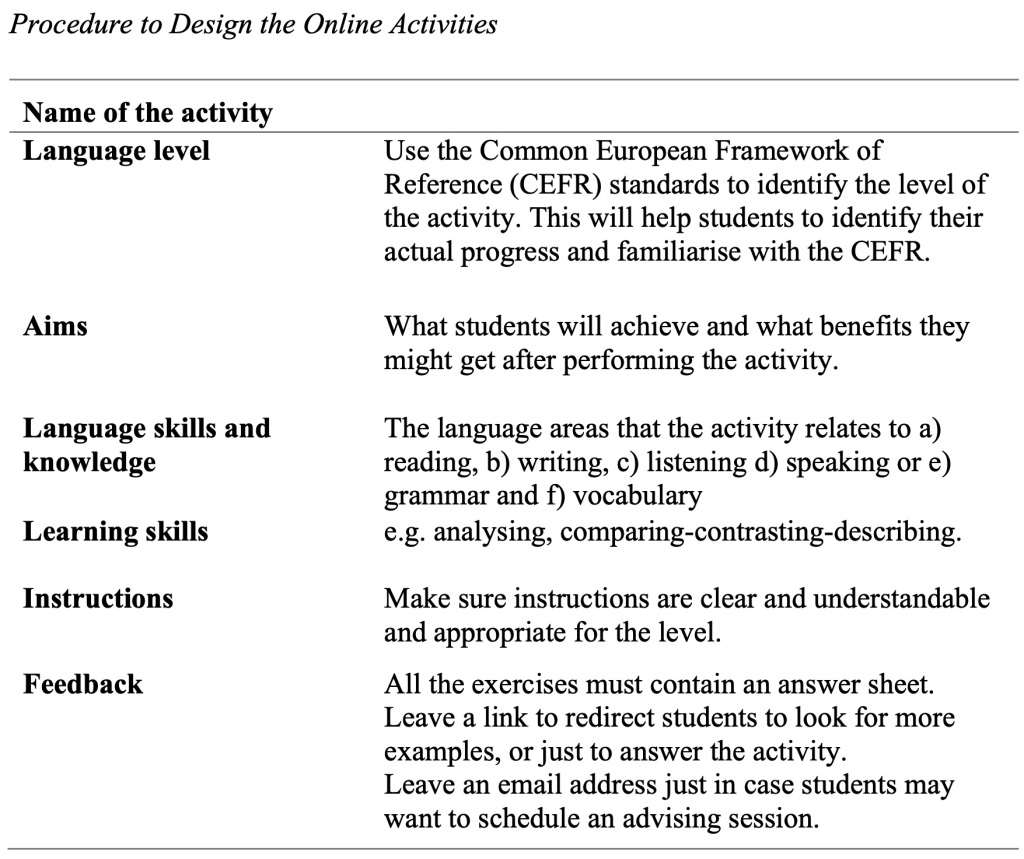

- The advisor must complete a format where the activity is explained (see Table 1). It must contain the objective of the activity, the suggested activities for the user, or a link where users can refer to more exercises. The user will be invited to leave or send a comment to the advisor about their experience when carrying out the activity.

- With the Facebook live webinars, advisors will be able to schedule webinars on topics like culture, literature, cinema or learning strategies, or any other topic they consider relevant for learning or the development of learner autonomy. These sessions will be scheduled within their SALC schedule or upon request.

- The activities planned by the advisors must be sent to the Coordinator individually. If they are approved, they will be published. If they are not approved, activities are then returned to the advisor with indicated corrections to be made. This working methodology will be in place until face-to-face work is authorised.

- Advisors must keep their logs with the contents of the material.

- The activities will be evaluated through the service satisfaction survey to know the reactions of the users to this new modality of the online activities. The comments that users leave on the different publication sources will also be considered when evaluation takes place.

Figure 2

The Design of Online Activities

Table 1

Procedure to Design the Online Activities

Conclusions

As discussed in the previous paragraphs, this challenging situation (COVID-19) has urged different educational contexts worldwide to reconsider their educational methodologies and SALCs were no exception. Many SALCs in Mexico faced the necessity of rethinking their mission and vision, probably changing their objectives, and reorganising their working systems to keep providing services at their centres due to the risks of having activities face-to-face. To overcome this problematic situation, this SALC needed to overcome at least two more challenges. Firstly, the centre needed to keep applying the statutory and regulatory requirements from ISO 9001:2015 to assure quality in the provision of the services. Secondly, to encourage SALC users to start using the facilities offered online, the course teachers needed to promote their use by encouraging them to choose e-learning materials according to their needs, in the same way as they had chosen resources in the SALC before the pandemic.

This article set out to demonstrate the versatility of the models presented which can be adapted to different situations, such as revising managerial processes at a SALC or even facing up to the challenging situation in which educational institutions have been obliged to adapt and adopt new teaching methodologies due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The models introduced in this paper were proposed as a reference for establishing or updating the services provided at a SALC under the principles of a QMS and hoping that these OPMs might potentially be adapted by others in the future. SALCs have valued the opportunity to demonstrate to their users the benefits of taking control of their learning to decide how to learn and which resources to use to become more autonomous language learners.

Notes on the Contributors

Beatriz Eugenia Navarro Cira is an ELT Professor at Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolas de Hidalgo, Mexico. She has an MA in ELT (University of Southampton, UK) and is a PhD Candidate in Applied Linguistics—also at the University of Southampton. Her field of research focuses on quality and autonomy at self-access language centres.

Isabel Carrillo López is an ELT Professor at Universidad Autonoma de Queretaro, Mexico. She has an MA in Enseñanza del Inglés como Lengua Extranjera [teaching English as a foreign language] from the University of Guadalajara. Her field of research mainly focuses on developing language acquisition in senior citizens of Mexico.

References

Benson, P. (1997). The philosophy and politics of learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 18–34). Addison Wesley Longman. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315842172-3

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Addison Wesley Longman.

Carson, L., & Mynard, J. (2012). Introduction. In J. Mynard & L. Carson (Eds.), Advising in language learning: Dialogue, tools and Context (pp. 3-15). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315833040

Crosby, P. B. (1984). Quality is free: Art of making quality certain. McGraw-Hill.

DeBlois, P., & Maltz, L. (2005). Current IT issues, 2005. EDUCAUSE Review, 40(3), 14–29. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2005/1/current-it-issues-2005

Doherty, G. D. (1994). The concern of quality in developing quality systems in education (1st ed.). Routledge.

ENALLT. (2020). Reunión virtual de centros de autoacceso en tiempos de COVID-19 [Online virtual meeting of self-access centres in times of COVID-19] [Facebook group]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/groups/289243688918750/

Everhard, C. J. (2018). Re-exploring the relationship between autonomy and assessment in language learning: A literature overview. Relay Journal, 1(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.37237/relay/010102

Feingenbaum, A. V. (1983). Total quality control. McGraw Hill.

Fry, K. (2001). E-learning markets and providers: some issues and prospects. Education Training, 43(4/5), 233–239. https://doi.org/10.1108/eum0000000005484

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Gilmore, H. L. (1974). Product conformance. Quality Progress, 7(5), 16–19.

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy and foreign language learning. Pergamon Press.

Holmes, B., & Gardner, J. (2006). E-Learning: Concepts and practice. Sage.

Hoyle, D. (2009). ISO 900. Quality systems handbook (6th ed.). Routledge.

Huang, J. (2009). Autonomy, agency and identity in foreign language learning teaching. [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Hong Kong.

International Organization for Standardization (IOS). (2012). Moving from ISO 9001:2008 to ISO 9001:2015.

Kato, S., & Mynard, J. (2016). Reflective dialogue: Advising in language learning. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315739649

Little, D. (1999). Developing learner autonomy in the foreign language classroom: A social-interactive view of learning and three fundamental pedagogical principles. Revista Canaria de Estudios Ingleses, 38, 77–88.

Morrison, B. (2002). The trouble process of mapping and evaluating a self-access language centre. In P. Benson & S. Toogood (Eds.), Learner autonomy 7: Challenges to research and practice (pp. 70–84). Authentik.

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (1999). An analysis of the skills and functions of language learning advisers. Links & Letters, 7, 111–126.

Mozzon-McPherson, M. (2001). Language advising: Towards a new discursive world. In M. Mozzon-McPherson & R. Vismans (Eds.), Beyond language teaching: Towards language advising (pp. 7–22). Centre for Information on Language Teaching and Research.

Mynard, J. (2011, January). The role of the learning advisor in promoting autonomy. Learner autonomy in language learning. AILA RenLA.

Mynard, J., & Sorflaten, R. (2003) Independent learning in your classroom. Teachers, Learners and Curriculum, 1(1), 34–38.

Nunan, D. (1997). Designing and adapting materials to encourage learner autonomy. In P. Benson & P. Voller (Eds.), Autonomy and independence in language learning (pp. 192–203). Addison Wesley Longman. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315842172-16

OECD (2005). E-learning in tertiary education. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264009219-en

Oxford, R. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Heinle & Heinle.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model for service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224298504900403

Peters, T. J., & Waterman, R. H. (1992). In search of excellence. Harper and Row.

Reinders, H. (2008). The what, why, and how of language advising. MexTESOL, 32(2), 13–22.

Reinders, H. (2010). Towards a classroom pedagogy for learner autonomy: A framework of independent language learning skills. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 35, 40–55. http://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2010v35n5.4

Hartshorne, R., & Haya, A. (2009). Examining student decision to adopt Web 2.0 technologies: Theory and empirical tests. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 21(3), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12528-009-9023-6

Riley, P. (1987). From self-access to self-direction. In J. A. Coleman & R. Towell (Eds.), The advanced language learner (pp. 75–88). Centre for Information on Language Teaching and Research.

Scharle, A., & Szabo, A. (2001). Learner autonomy (1st. ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Sheerin, S. (1997). Self-access. Language Teaching, 24(3), 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0261444800006315

Tassinari, M. G. (2010). Autonomes fremdsprachenlernen: Komponenten, kompetenzen, strategien [Autonomous foreign language learning: Components, skills, strategies]. Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/b17580

Twigg, C. A. (2001). Innovations in online learning: Moving beyond no significant difference. Center for Academic Transformation.

UNESCO (2005). Guidelines for quality provision in cross-border higher education. http://doi.org/10.1787/9789264065994-ru

UNESCO. (2020). COVID-19 response. https://uil.unesco.org/covid-19-response-0

Wentling T. L., Waight, C., Gallagher, J., La Fleur, J., Wang, C., & Kanfer, A. (2000). E-learning: A review of literature. Knowledge and Learning Systems Group NCSA 9, 1–73.