Abstract

Maximize Presupposition! (MP), as originally proposed in Heim (Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung, pp. 487–535, 1991) and developed in subsequent works, offers an account of the otherwise mysterious unassertability of a variety of sentences. At the core of MP is the idea that speakers are urged to use a sentence ψ over a sentence ϕ if ψ contributes the same new information as ϕ, yet carries a stronger presupposition. While MP has been refined in many ways throughout the years, most (if not all) of its formulations have retained this characterisation of the MP-competition. Recently, however, the empirical adequacy of this characterisation has been questioned in light of certain newly discovered cases that are infelicitous, despite meeting MP-competition conditions. This has led some researchers to broaden the scope of MP, extending it to competition between sentences which are not contextually equivalent (Spector and Sudo in Linguistics and Philosophy 40(5):473–517, 2017) and whose presuppositions are not satisfied in the context (Anvari in Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory 28, pp. 711–726, 2018; Manuscript, IJN-ENS, 2019). In this paper, we present a body of evidence showing that these formulations of MP are sometimes too liberal, sometimes too restrictive: they overgenerate infelicity for a variety of felicitous cases while leaving the infelicity of minimally different cases unaccounted for. We propose an alternative, implicature-based approach stemming from Magri (PhD dissertation, MIT, 2009), Meyer (PhD dissertation, MIT, 2013), and Marty (PhD dissertation, MIT, 2017), which reintroduces contextual equivalence and presupposition satisfaction in some form through the notion of relevance. This approach is shown to account for the classical and most of the novel cases. Yet some of the latter remain problematic for this approach as well. We end the paper with a systematic comparison of the different approaches to MP and MP-like phenomena, covering both the classical and the novel cases. All in all, the issue of how to properly restrict the competition for MP-like phenomena remains an important challenge for all accounts in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

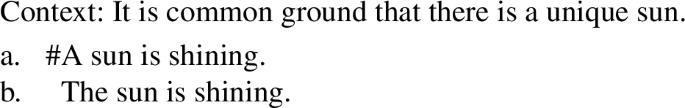

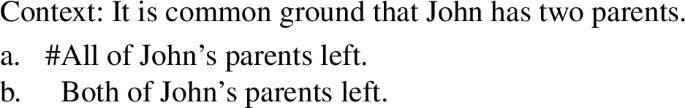

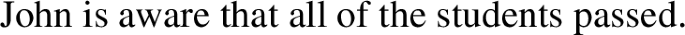

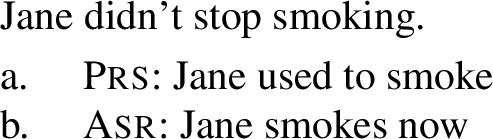

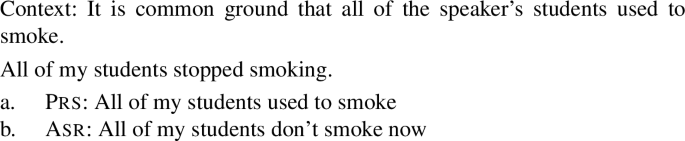

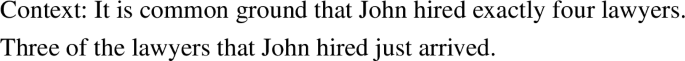

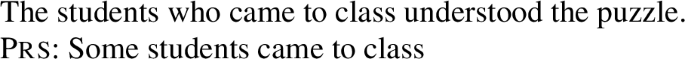

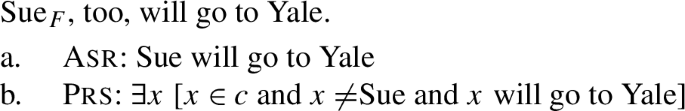

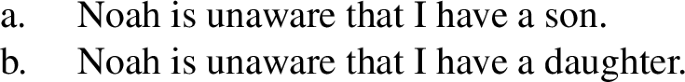

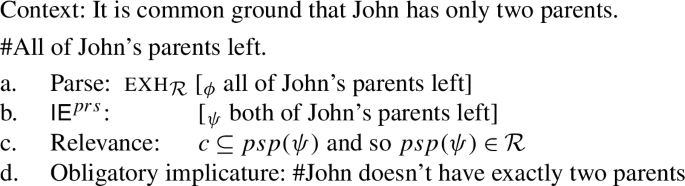

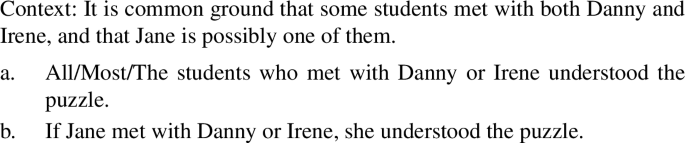

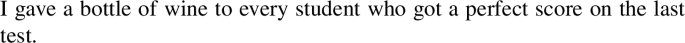

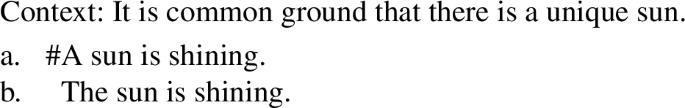

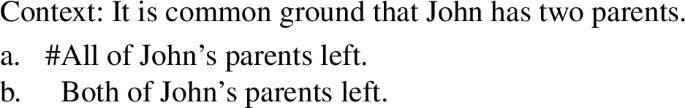

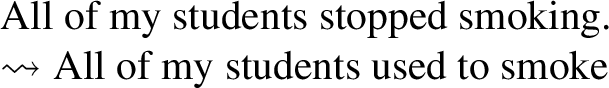

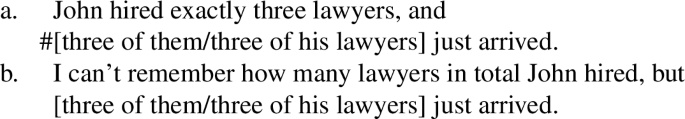

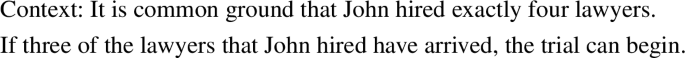

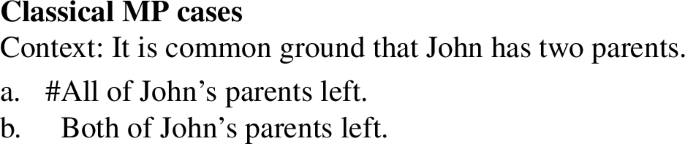

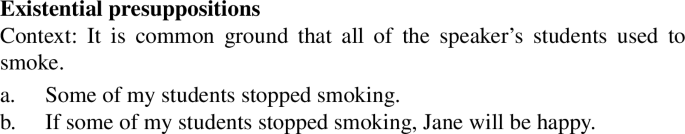

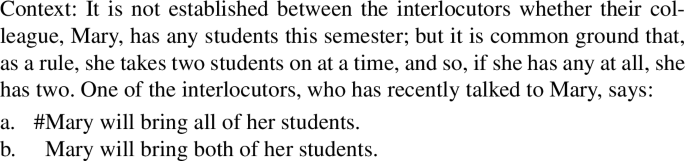

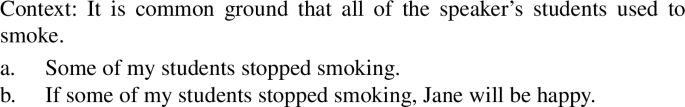

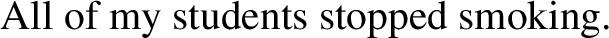

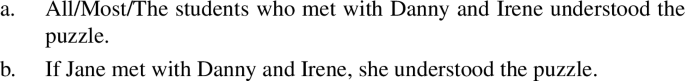

The minimal pairs in (1)-(2) exemplify the long-standing observation originating in Heim (1991) that the utterance of a sentence ϕ is infelicitous in a context c if ϕ has a presuppositionally stronger competitor ψ whose presupposition is already common ground at c, i.e., mutually accepted by the interlocutors in c, and makes the same contribution as ϕ at c.

-

(1)

-

(2)

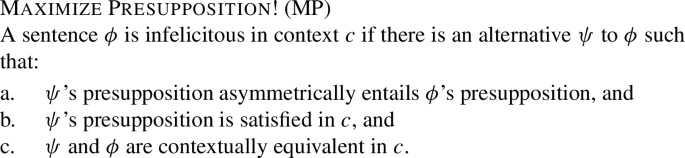

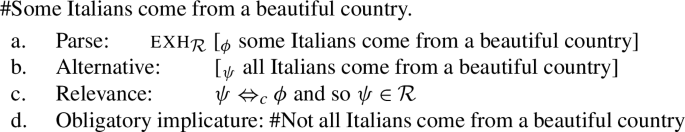

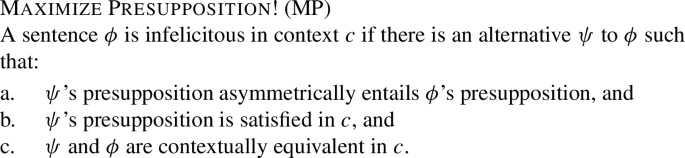

Heim (1991) proposed to derive such contrasts from a general principle of language use which has come to be known as Maximize Presupposition! (MP henceforth), exhorting speakers to make their conversational contributions by ‘presupposing as much as possible.’ Since Heim’s formulation of MP, many researchers have contributed to describing and refining the formal aspects of the competition at work in examples like (1)-(2), together with the contextual conditions on which this competition effectively leads to infelicity effects. A somewhat standard formulation of MP is given in (3).

-

(3)

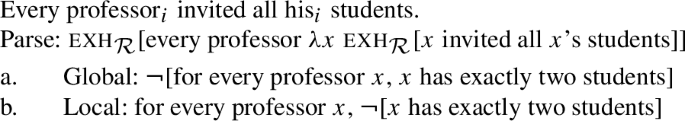

At the core of MP is the idea that cooperative speakers are urged to use a sentence ψ over a sentence ϕ if, in the context of use, ψ contributes the same new information as ϕ, yet carries a stronger presupposition. This principle accounts for the contrasts in (1)-(2): in these examples, the (a)-sentences are deemed infelicitous by MP because they compete with the minimally different (b)-sentences, which convey the same information as their (a)-counterparts but carry stronger presuppositions that are satisfied in the relevant contexts. Thus, MP offers an account of the otherwise mysterious (un)assertability of a variety of sentences against given contextual information. Since the initial analysis of the motivating cases in (1)-(2), MP has been successfully applied to a variety of phenomena, and the classical picture sketched above has been extended and implemented in different versions (a.o., Percus 2006, 2010; Sauerland 2008; Chemla 2008; Schlenker 2012; Katzir and Singh 2013; Rouillard and Schwarz 2017; Magri 2009; Marty 2017; Anvari 2019). Crucially, most (if not all) of its reformulations thus far have retained the three key ingredients of the classical formulation in (3). Recently, however, some new data have been brought to light that put these basic tenets in doubt. These data appear very similar to the ones licensed by MP on the received view, yet they are unexpectedly infelicitous. To accommodate these data, some researchers have proposed to relax the restrictions on the scope of phenomena MP was held to apply to: on their view, the competition in question should be extended to sentences which are not contextually equivalent (Spector and Sudo 2017) and whose presuppositions are not satisfied in the context (Anvari 2018, 2019).

In this paper, we present a body of evidence showing that these novel proposals are sometimes too liberal, sometimes too restrictive: they overgenerate infelicity for a variety of felicitous cases, while leaving the actual infelicity of seemingly similar cases unaccounted for. After presenting the challenges for MP and how the novel proposals address them in Sect. 2, we show in Sect. 3 that, despite their immediate successes, these proposals overgenerate specifically in cases involving (1) environments giving rise to existential presuppositions, (2) cardinal partitives, and (3) the restrictor of definites, universal quantifiers, which-phrases, and the antecedent of conditionals. In addition, we show that they undergenerate by not capturing the infelicity of infelicitous sentences carrying disjunctive presuppositions, building on cases observed by Spector and Sudo (2017). We argue that the culprit is precisely the fact that these novel principles drop or weaken some of the main ingredients of MP above, in particular the requirement of contextual equivalence. We move in Sect. 4 to propose an alternative approach based on implicatures, stemming from Magri 2009, Marty 2017, 2019b, and Marty and Romoli 2021, which reintroduces contextual equivalence in some form through the broader notion of relevance. This approach can account for the classical cases and, once combined with Meyer’s (2013) approach to ignorance implicatures, it can also address the presupposed ignorance challenge in full, including the original cases by Spector and Sudo (2017) and the variants that we present below. As we will discuss, while Meyer’s (2013) proposal is also compatible with competing approaches, the resulting systems still fail to achieve the same results. Finally, this approach captures some of the overgenerating cases mentioned above, while some other cases remain problematic for it as well. We end the paper with a synthetic comparison of the different approaches to MP and MP-like phenomena vis-a-vis the old and novel cases. All in all, the issue of how to properly restrict the competition for MP-like phenomena, accounting for the classical and the novel cases, remains an important challenge for all accounts in the literature.

2 Background

2.1 The challenge to contextual equivalence

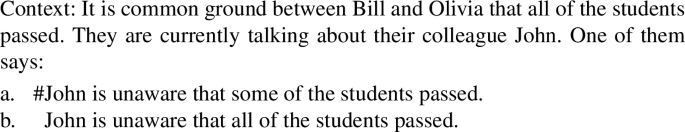

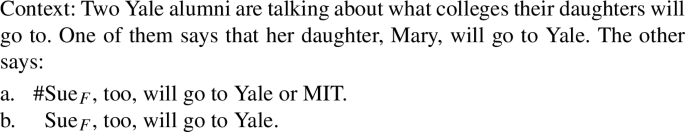

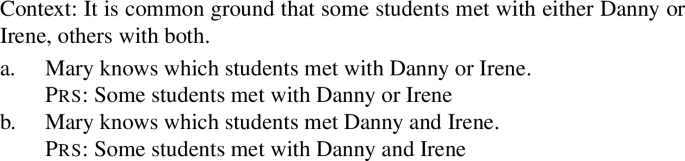

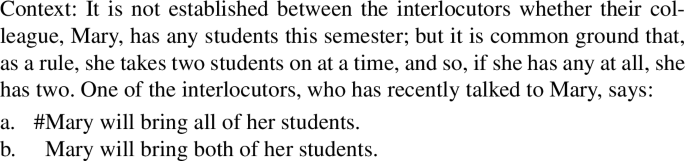

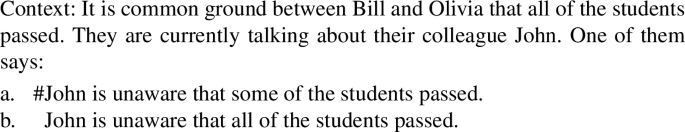

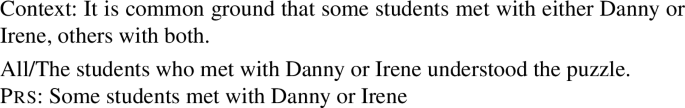

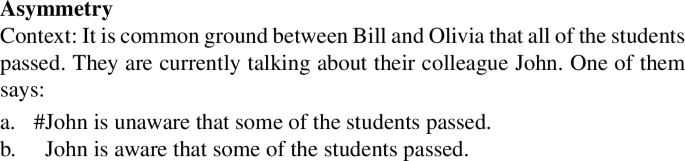

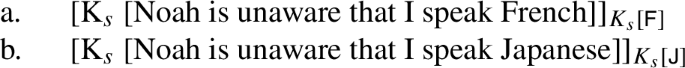

A recent line of work has investigated cases like (4) and (5), which are often treated together with the classical ones above (a.o., Sharvit and Gajewski 2008; Gajewski and Sharvit 2012; Spector and Sudo 2017; Marty and Romoli 2021):Footnote 1

-

(4)

-

(5)

Given the similarities between (4)-(5) and the classical cases in (1)-(2), it is tempting to try and subsume the effects in (4)-(5) under MP as well. However, as Sharvit and Gajewski (2008) and Spector and Sudo (2017) discuss, cases like (4) and (5) are beyond the scope of application of MP: although the competing (b)-sentences carry stronger presuppositions which are met in context, they are not contextually equivalent to the (a)-sentences and therefore the third condition in (3c) is not met.

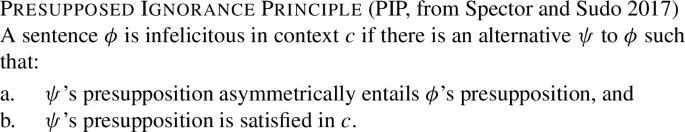

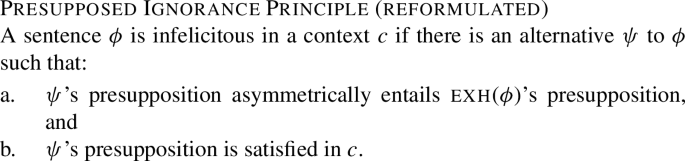

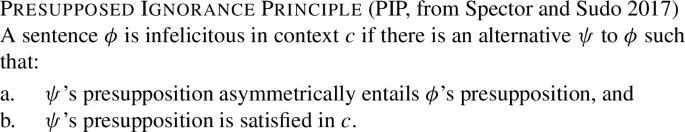

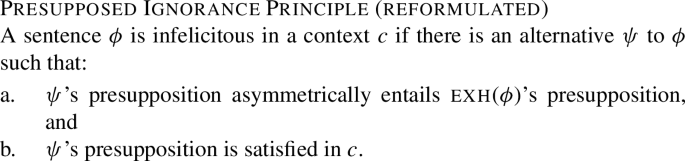

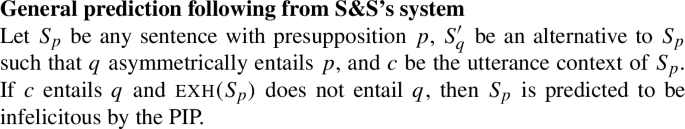

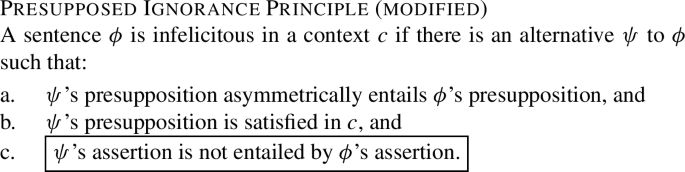

To account for these cases, Spector and Sudo (2017) (S&S henceforth) extend the classical MP approach above by dropping the contextual equivalence requirement, and propose a system based on two distinct forms of scalar strengthening, which operate independently but interact with one another. First, they adopt a regular theory of scalar implicatures that operates at the assertion level and allows the presuppositions of the negated alternatives to project. Second, in place of MP, they propose the pragmatic principle in (6), a generalised version of MP, which they call the Presupposed Ignorance Principle (PIP henceforth).

-

(6)

In short, the formulation of the PIP parallels that of MP up to one critical stage: the PIP leaves out the MP-requirement in (3c) that the presuppositional competitors to a given sentence be contextually equivalent to that sentence, allowing in principle more presuppositional competitors than MP. This minimal amendment allows S& S to capture the cases in (4)-(5), where contextual equivalence does not obtain, while preserving the classical ones in (1)-(2). Finally, S&S argues that the interaction between the PIP and the computation of scalar alternatives can account for contrasts like the one between (4a) and its positive counterpart in (7).

-

(7)

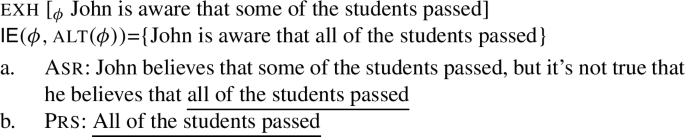

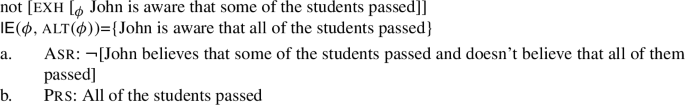

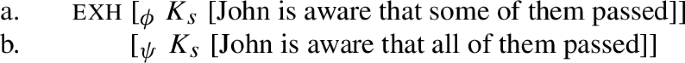

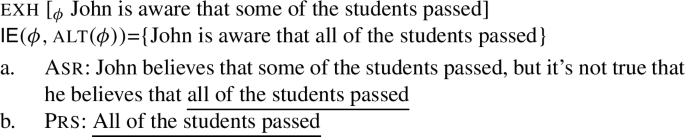

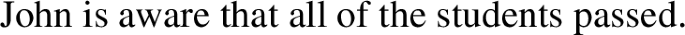

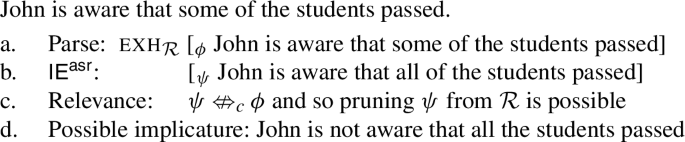

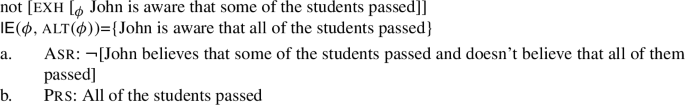

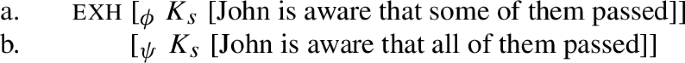

Just like (4a), (7) has a presuppositionally stronger alternative whose presupposition is met in context, namely John is aware that all of the students passed. However, as we discuss in detail below, the meaning of (7), unlike that of (4a), can be strengthened by computing the scalar implicature associated with this alternative – that is, by negating this alternative and subsequently letting its presupposition project up. As a result, (7) together with its scalar implicature presupposes in fact that all of the students passed, and therefore the application of the PIP becomes vacuous in this case (i.e., there is no alternative with a stronger presupposition), hence the felicity of (7).

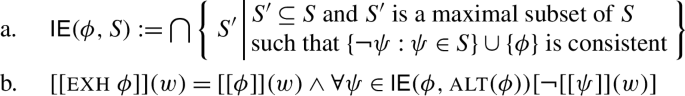

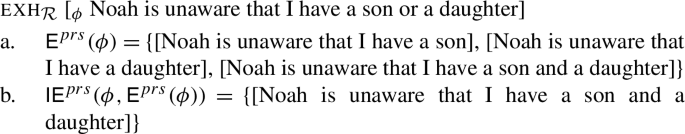

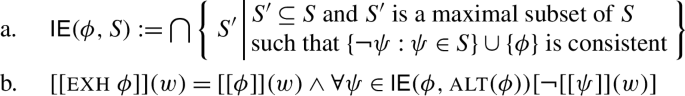

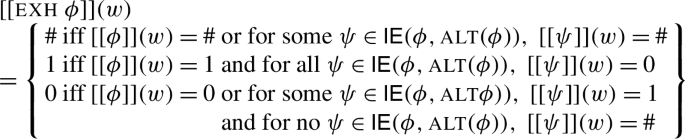

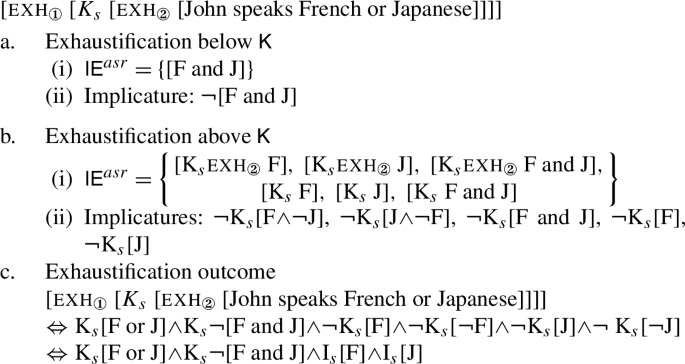

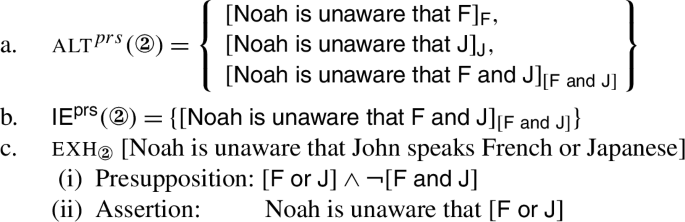

To illustrate in further detail, the system put forward by Spector and Sudo (2017) is based on the following ingredients: (i) the Presupposed Ignorance Principle (PIP) in (6), which operates at the presupposition level, (ii) a mechanism for computing implicatures at the assertion level, and (iii) the interaction between the mechanisms in (i) and (ii). At the presupposition level, the PIP essentially requires that among a set of alternative sentences, one should use the one(s) with the strongest presupposition(s) satisfied in context, regardless of whether it makes the same contribution in the context as the other alternatives (i.e., regardless of whether the considered alternatives are contextually equivalent). Consequently, whenever a sentence has an alternative with a logically stronger presupposition satisfied in context, the PIP predicts that sentence to be infelicitous. At the assertion level, scalar strengthening proceeds in standard ways. For concreteness, S&S assume that scalar implicatures are computed by applying a covert exhaustivity operator, notated by ‘exh.’ Adopting Fox’s (2007) notion of Innocent Exclusion (IE) given in (8a), this operator can be defined as in (8b), where ϕ is any sentence and alt(ϕ) the set of formal alternatives to ϕ. In short, applying exh to a sentence ϕ outputs the conjunction of ϕ and the negation of all of ϕ’s alternatives that are innocently excludable, i.e., those alternatives to ϕ that can be consistently negated simultaneously without contradicting ϕ or entailing the truth of other alternatives.

-

(8)

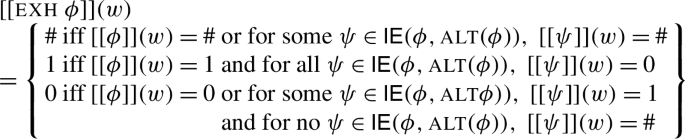

In addition, S&S refine the scalar strengthening mechanism above to account for its interaction with presuppositions. Specifically, adopting a trivalent semantics for presuppositions, S&S propose to adjust the bivalent definition of exh in (8) to a trivalent setting so as to let exh pass up the presuppositions of the alternatives it excludes, just like negation passes up the presuppositions of the sentence it negates. Excludable alternatives are thus negated in a strong sense: the negation of an alternative ψ with presupposition p is true if and only if p is true and ψ is false. In short, S&S’s adjustments are twofold: first, the notion of Innocent Exclusion in (8a) is redefined by making use of strong negation, and second, exh is defined so as to behave as a ‘presupposition hole’ with respect to the presupposition of the alternatives. In other words, [[exh ϕ]](w) is undefined if any of its alternatives is undefined. The novel definition of exh from Spector and Sudo (2017, (63)) is given in (9).

-

(9)

The PIP can be now more explicitly formulated as in (10), by taking into account the potential role of exh. That is, a sentence ϕ is infelicitous if it has an alternative ψ, the presupposition of which is satisfied in the context and asymmetrically entails the presupposition of the strengthened meaning of ϕ.

-

(10)

Given the assumptions about exh, the PIP, and their interplay, the system by S&S can account for the infelicity of cases like (4)-(5) and for the contrast between (4a) and (7), which are not covered by the classical MP approach. First, when (7) is strengthened by exh, the presupposition of the negated all-alternative projects to the whole sentence. In other words, exhaustification strengthens the meaning of exh’s prejacent in two related ways: (i) by negating the assertion of its all-alternative, and subsequently (ii) by passing up the (stronger) presupposition of that alternative. As a result, the application of the PIP becomes vacuous, which accounts for the felicity of (7) in the relevant context.

-

(11)

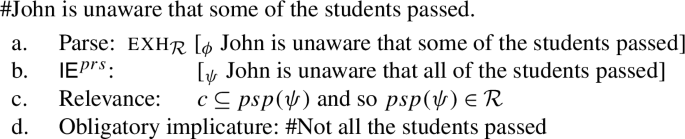

By contrast, in negative cases like (4a), the corresponding all-alternative is not excludable, and so exhaustification is vacuous and the PIP effectively applies, giving rise to a conflicting inference. That is, by application of the PIP, an utterance of (4a) triggers the presupposed ignorance inference ¬CG(all of the students passed). This makes the sentence contradictory with common ground, accounting for its infelicity.

-

(12)

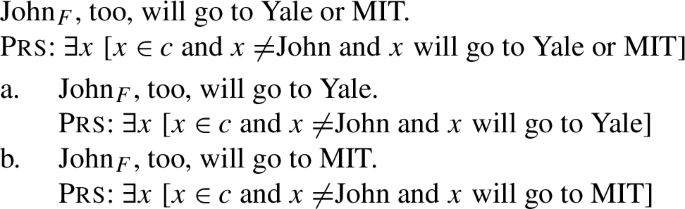

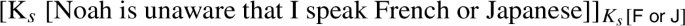

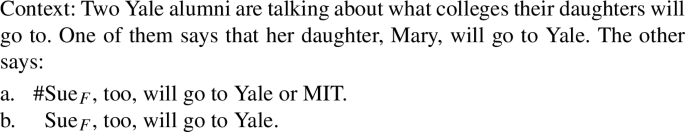

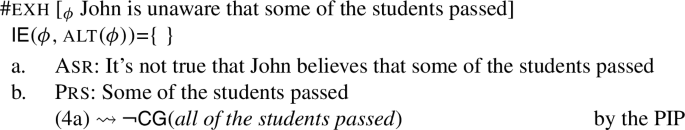

Through the PIP, S&S’s system can also account for the infelicity of (5a). Indeed, the sentence in (5a) has, among others, the formal alternatives in (11a) and (11b), each of which carries a stronger presupposition than the disjunctive presupposition of (5a).Footnote 2 Thus, by application of the PIP, an utterance of (5a) is predicted to give rise to the inferences that neither the content of (11a)’s presupposition nor that of (11b)’s presupposition is common ground. As is easy to verify, the presupposed ignorance inference associated with (11a) conflicts with common ground since it was previously mentioned that Mary will go to Yale and therefore (11a)’s presupposition is satisfied in the suggested context.

-

(13)

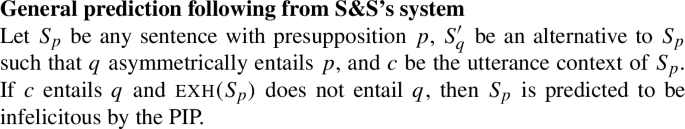

To summarise, Spector and Sudo (2017) propose two forms of scalar strengthening, operating at different levels and interacting with each other. At the assertion level, exh negates the assertion of certain alternatives and passes up their presuppositions. At the presupposition level, the PIP derives weaker inferences about what is common ground. Importantly, the scope of application of the PIP can be tempered by the effect of exhaustification: scalar strengthening via exh can sometimes ‘rescue’ a sentence from the infelicity that would otherwise arise from applying the PIP directly to the plain meaning of that sentence, like for instance in the analysis of (7) above. The interaction between these two scalar strengthening mechanisms is thus at the heart of S&S’s account of the asymmetry between (4a) and (7). This gives rise to the general prediction in (12).

-

(14)

The prediction in (12) holds because, in the absence of a bleeding relation between exh and the PIP relative to the presupposition q — a relation where q does not end up presupposed as a result of applying exh — if q is satisfied in c, then the PIP will generate the conflicting ignorance inference ¬ CG(q), from which infelicity should follow. In the next subsection, we turn to the challenge to presupposition satisfaction and the proposal by Anvari (2018, 2019).

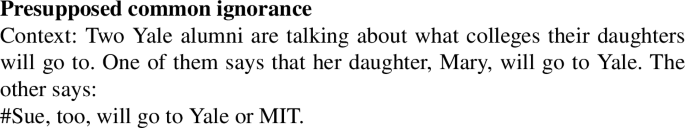

2.2 The challenge to presupposition satisfaction

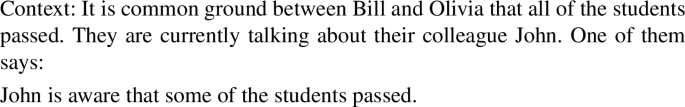

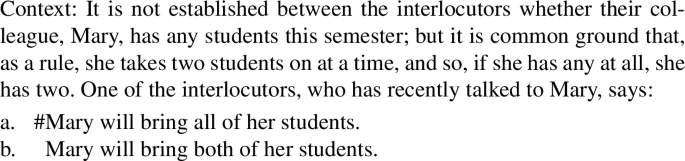

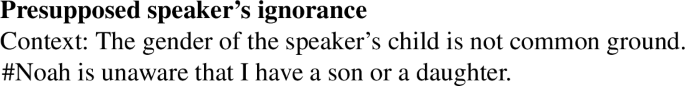

Another challenge comes from the observation that MP-like effects may arise even though the stronger presupposition of the competing alternative is not satisfied in context, an observation originally from Percus 2010 and recently extended in Anvari 2018, 2019. This observation directly challenges another key ingredient of MP, the requirement that the presupposition of the competitor be satisfied in the context. To illustrate, consider the case in (13) from Percus 2010. While the two sentences at hand are contextually equivalent, the stronger presupposition of the (b)-sentence is not satisfied in the given context. Yet the (a)-sentence is intuitively infelicitous, which is not expected by MP or by the PIP.

-

(15)

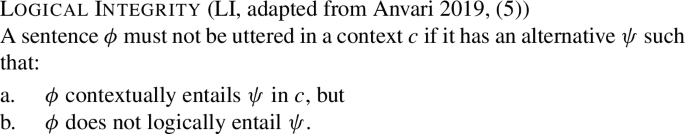

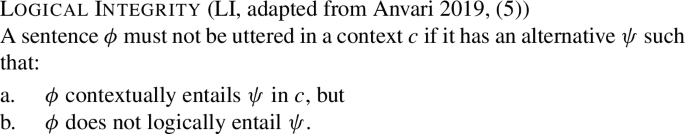

On the basis of cases like (13), among others, Anvari (2019) proposes to replace MP with a different principle, which he dubs Logical Integrity (LI henceforth). In fact, LI is a generalisation which aims at capturing the unacceptability of a variety of sentences, some of which were previously captured by MP or the PIP. The gist of this generalisation is that a sentence ϕ is deemed infelicitous if it has an alternative ψ that is logically non-weaker, yet contextually entailed by ϕ. In other words, LI forces the logical relation between a sentence and its alternatives to be preserved once contextual information is considered, hence the name ‘logical integrity’. We will consider the formulation of this principle in (14) and assume that a sentence is infelicitous if any part of it violates (14).Footnote 3

-

(16)

Note that LI doesn’t include the contextual equivalence ingredient of MP (replaced by contextual entailment), nor the requirement about presupposition satisfaction. As a result, LI can handle cases like (13), for it applies regardless of whether the presupposition of the competitor is satisfied in the context: (13a) is predicted to be infelicitous by LI because (13a) contextually entails (13b) but does not logically entail it. Moreover, as Anvari (2019) shows, LI can account for the classical MP cases and the asymmetry with factives. To illustrate, consider first the sentence in (1). The definite competitor to (1a) in (1b) is not logically entailed by (1b) (the former can be undefined when the latter is true). In the given context, however, if (1a) is true, then so is its definite-alternative. Hence, we have contextual but not logical entailment, and consequently (1a) violates LI in this context. Next, consider the contrast in (4): the all-alternative to (4a) in (4b) is not logically entailed by (4a), but when we add the assumed contextual information that all of the students passed, (4b) becomes contextually entailed by (4a). Thus, (4a) is correctly predicted to be infelicitous by LI. On the other hand, (7) is neither logically nor contextually entailed by its all-alternative in (15) and so, unlike (4a), (7) does not violate LI. Therefore, the contrast between (4a) and (7) is also nicely captured by this approach.

-

(17)

It is worth noting, however, that unlike the PIP approach, the LI approach does not capture the contrast in (5), i.e., the presupposed ignorance case from S&S. The reason for that is that the formal alternatives to (5a) in (11) are neither logically nor contextually entailed by (5a), and therefore they do not qualify as competing alternatives to (5a) in light of LI. In the absence of such competitors, the infelicity of (5a) is left unexplained by LI.

2.3 Summary

Some of the key ingredients of MP have been challenged in the recent literature. The requirement of contextual equivalence has been challenged by cases like (4a), while that of presupposition satisfaction has been challenged by cases like (13). In response to the first challenge, Spector and Sudo (2017) have put forward a more general principle, the PIP. In response to the second challenge, Anvari (2019) has proposed that we replace MP with a novel principle, LI, which also weakens the requirement of contextual equivalence.

In the next section, we evaluate the empirical adequacy of the PIP and LI with respect to a set of novel cases. The results of this investigation are challenging for both approaches, and specifically for the idea that contextual equivalence can be harmlessly eliminated from the set of conditions restricting the set of presuppositional competitors to a given sentence. We will mostly focus on the requirement of contextual equivalence for now, but we will go back to presupposition satisfaction in Sect. 4. The cases to be discussed involve, among others, environments giving rise to existential presuppositions, cardinal partitives, the restrictor of universal quantifiers and the antecedent of conditionals, and a variant of S&S’s presupposed ignorance case.Footnote 4

3 Problems: Overgenerating and undergenerating infelicity

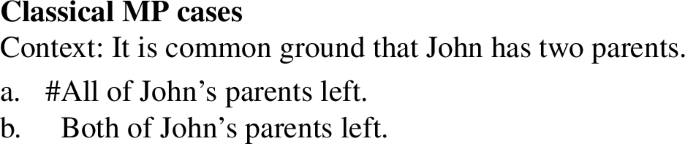

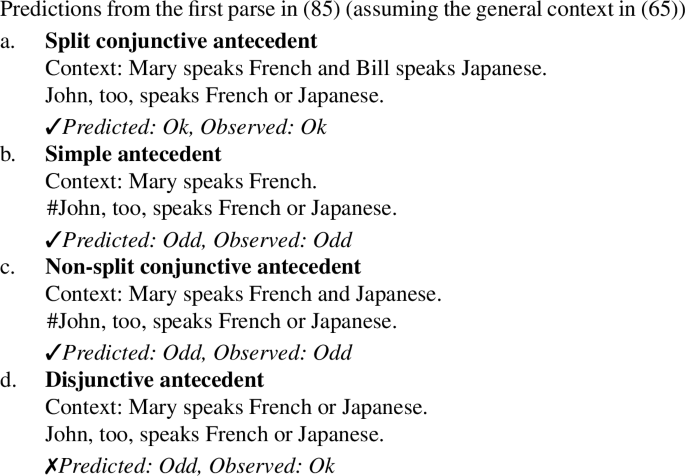

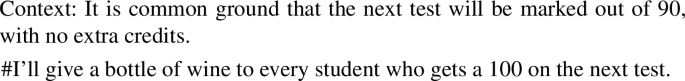

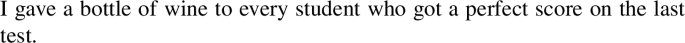

This section presents in turn four cases which are problematic for both S&S’s and Anvari’s proposals. In the first three cases, we will see that the PIP and LI overgenerate in predicting infelicity for sentences which are intuitively felicitous; in the last one, we will see that they undergenerate by not predicting the infelicity of intuitively infelicitous sentences. But before going on, some methodological considerations are in order.

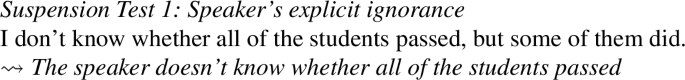

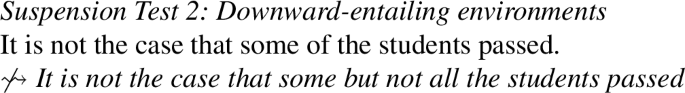

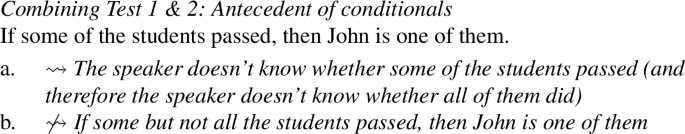

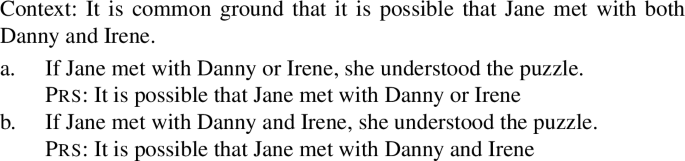

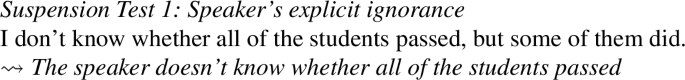

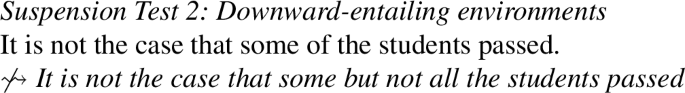

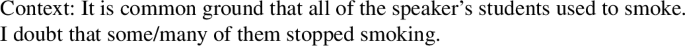

A simple way of testing the prediction of the PIP in (12) is to consider cases which do not involve exhaustification, given the general properties of the context or the properties of the linguistic environment in question. There are at least two ways to do that. First, we can consider the possible implicatures that a sentence may give rise to and verify that the presuppositions of those implicatures do not affect the subsequent application of the PIP. Second, we can rely on linguistic contexts that render the application of exh vacuous in the first place. This can be done for instance by setting up the surrounding context so as to force implicature suspension, as in (16), or by embedding the relevant sentence in a downward-entailing (DE) environment (e.g., under negation), as in (17). Interestingly, conditionals combine both advantages: the antecedent of conditionals is a DE-environment (or at least non-UE) and conditionals give rise to an ignorance inference about their antecedent, as illustrated in (18) (a.o., Gazdar 1979).

-

(18)

-

(19)

-

(20)

We will use both these verification strategies whenever applicable to assess the possible effects of exhaustification and provide additional controls for our test cases.

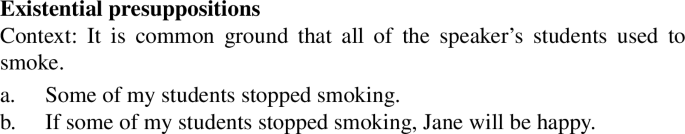

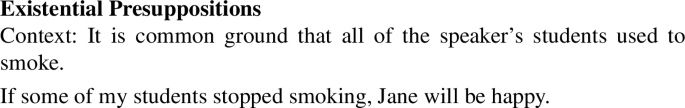

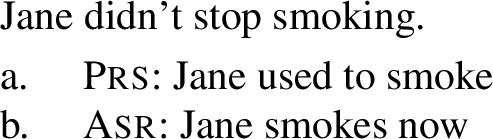

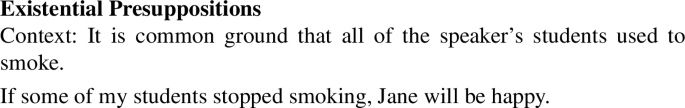

3.1 Case 1: Existential presuppositions

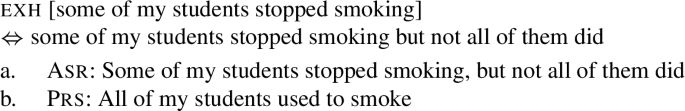

Consider a sentence with a presuppositional predicate like (19). We can paraphrase the presupposition of this sentence as in (19a) and its asserted content as in (19b).

-

(21)

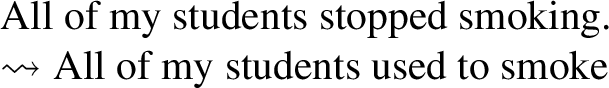

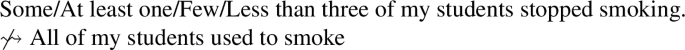

Consider now embedding stop in the scope of a quantifier, as in (20) and (21). Intuitively, while the presupposition of stop projects universally in the scope of all, it doesn’t do so in the scope of existential quantifiers like those in (21).Footnote 5

-

(22)

-

(23)

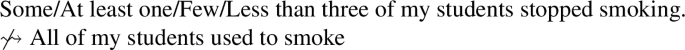

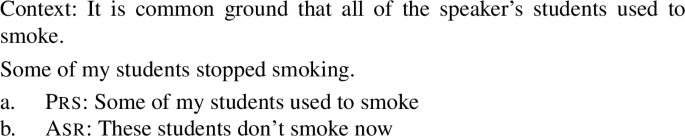

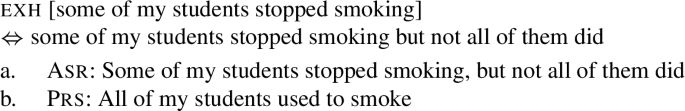

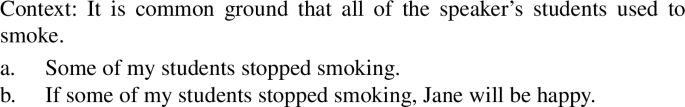

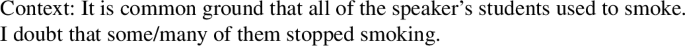

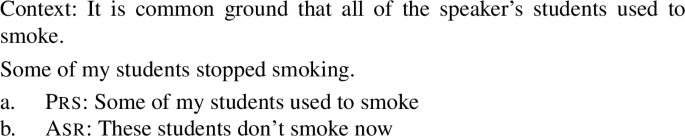

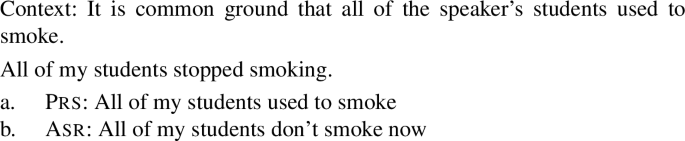

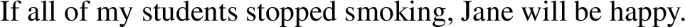

In the following, we will use the quantifier and scalar item some and assume for simplicity that the presupposition of (21) is an existential presupposition, i.e., Some of my students used to smoke. We note, however, that all that is needed for creating the problem below is simply that the presupposition be weaker than universal. Against this background, consider again the sentence in (21), with its presupposition in (21a) and its asserted content in (21b). Importantly for our purposes, (21) can be felicitously uttered in a context in which it is known that all of my students used to smoke.

-

(24)

Note, however, that (21) has (22) as a presuppositionally stronger alternative, the presupposition of which is also satisfied in those contexts. If the PIP were to apply on the basis of the competition between (21) and (22), it would incorrectly predict (21) to be infelicitous.

-

(25)

S&S’s system, however, does not make this unwarranted prediction. Since (22) is also assertively stronger than (21), the meaning of (21) can be first strengthened by computing the implicature associated with (22), the presupposition of which then projects to the whole sentence, as shown in (23). This strengthening operation renders the application of the PIP vacuous, since (23) and (22) are now presuppositionally equivalent. As a result, the sentence in (21) is in fact expected to be felicitous in the context above on its strengthened meaning.

-

(26)

This result is intuitively correct and, in fact, such cases could even be taken as an argument for S&S’s proposal regarding the interactions between exh and the PIP. There is, however, an immediate expectation that follows from the general prediction in (12): in contexts in which (22)’s presupposition is satisfied but the ‘rescuing’ implicature in (23) gets suspended, the PIP should apply in a non-vacuous fashion, and therefore infelicity should follow. This expectation can be tested using the suspension tests outlined above.

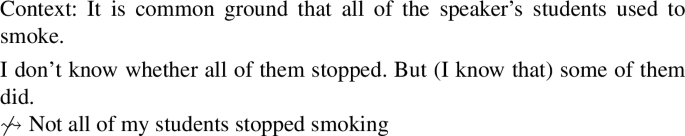

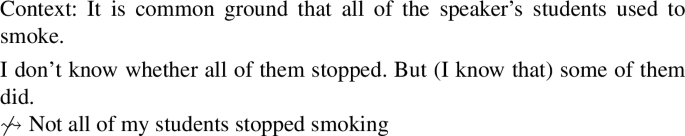

Consider first a case like (24), where the speaker explicitly asserts that he is ignorant about the all-alternative in (22). This short discourse is felicitous, and the fact that it is tells us that, in that context, the implicature in (23) is suspended, for otherwise the continuation in (24) would give rise to a contextual contradiction. But precisely in the absence of this implicature, one would expect the PIP to apply and, therefore, the second sentence in (24) to be infelicitous, contrary to facts.

-

(27)

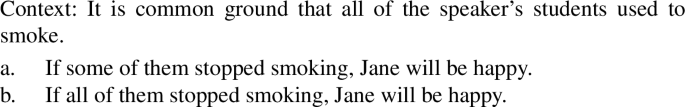

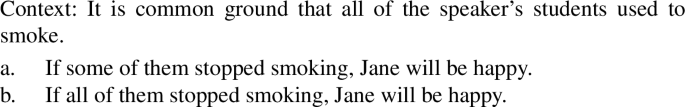

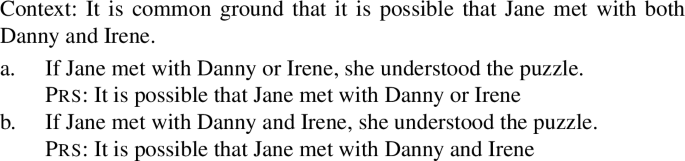

In response to (24), one could try to make use of a notion of relevance to explain why the stronger all-alternative is considered neither by exh nor by the PIP in such cases. For instance, one could hypothesize that an alternative ψ to a sentence ϕ cannot take part in any strengthening operation affecting ϕ’s meaning if the speaker is known to be ignorant about ψ. This explanation, however, does not extend to our second way of testing implicature suspension. Consider for instance the sentences in (25), where (21) and (22) are now embedded in the antecedent of conditionals:Footnote 6

-

(25)

Intuitively, (25a) conveys its plain (i.e., non-strengthened) meaning, compatible with that of (25b). And indeed, the computation of a not-all implicature in this environment is generally disfavoured as it would weaken (rather than strengthen) the global meaning of (25a). In the absence of an implicature, the PIP should thus apply on the basis of the competition between (25a) and (25b), predicting (25a) to be felicitous only if it is not common ground that all the students used to smoke. But this prediction is incorrect since (25a) is in fact felicitous in the context above.Footnote 7,Footnote 8

Note that it could be argued that exh applies in (25a) nonetheless, precisely because its application is needed to rescue the sentence from infelicity. Yet this explanation faces two serious issues. First, it does not align with speakers’ intuitions about the meaning of (25a): speakers accept (25a) as felicitous in the absence of the not-all implicature. Second, if we were to assume that exh nonetheless applies in DE-environments like (25a), we would lose S&S’s explanation for the asymmetry between (4a) and (7), since exh could then be applied in (4a) too, preventing the PIP from applying and thus rescuing that sentence from infelicity.Footnote 9 Similar data can be reproduced with other presuppositional triggers (e.g., another, again, definite descriptions), and other downward entailing contexts.Footnote 10

In sum, one crucial feature of S&S’s system is the interaction between exh and the PIP, where the application of the former takes precedence and may lead to a vacuous application of the latter. The cases we just presented are problematic for this architecture because they are cases where exh does not apply and the conditions of application of the PIP are met, and therefore they are incorrectly predicted to be infelicitous.

Turning now to the LI approach, it is easy to show that it encounters the same overgeneration issues as the PIP. To illustrate, consider again the case of existential presuppositions in (21). Anvari’s proposal has no problem with this particular case, since the all-alternative in (20) is not contextually entailed by (21) even when we consider the contextual information that all of my students used to smoke. That is, in the relevant cases, (20) is neither logically nor contextually entailed by (21). However, if we move to the minimal variant of (21) in (25a), the situation changes: the all-alternative to (25a) in (25b) is not logically entailed by (25a), yet if we add the contextual information above, contextual entailment now obtains. Therefore, LI incorrectly predicts (25a) to be infelicitous.Footnote 11

In sum, LI replaces the notion of contextual equivalence with that of contextual entailment and, in so doing, it successfully covers the novel cases by S&S discussed above. The examples in this subsection, however, are challenging for this proposal because, while the competitors are not contextually equivalent, the asserted sentences do contextually entail their competitors and are therefore incorrectly predicted to be infelicitous by LI.

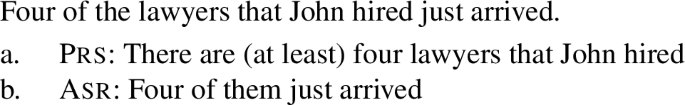

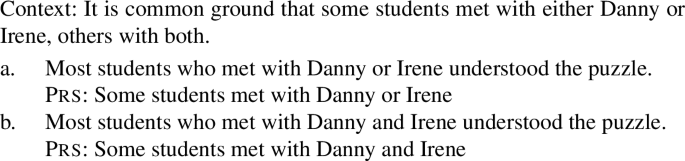

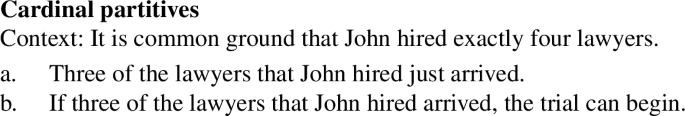

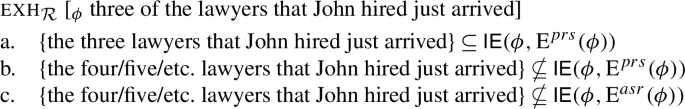

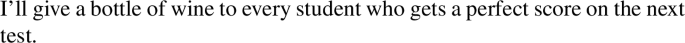

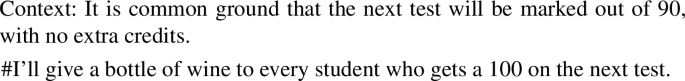

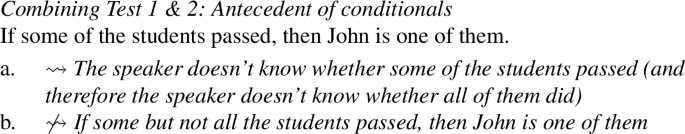

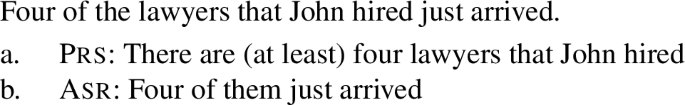

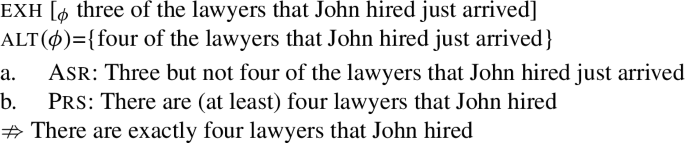

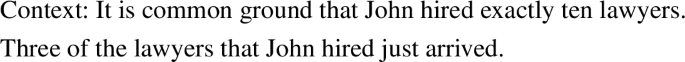

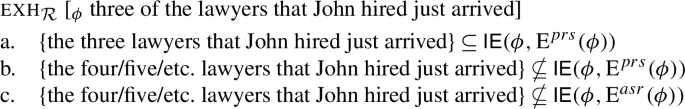

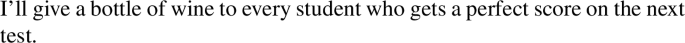

3.2 Case 2: Cardinal partitives

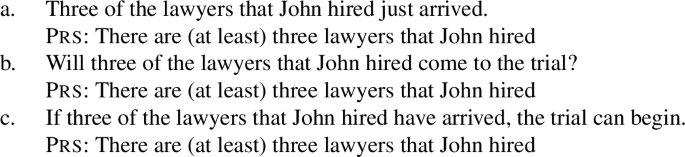

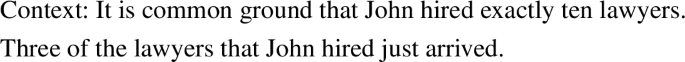

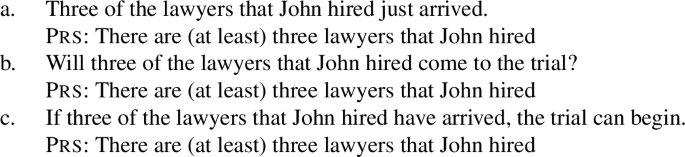

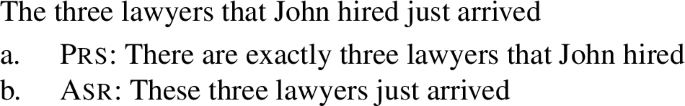

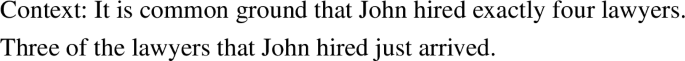

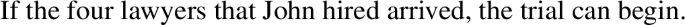

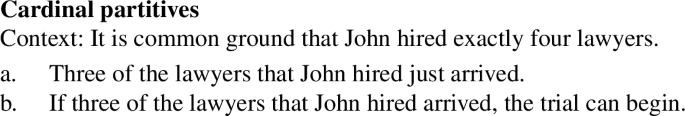

Consider the sentences in (26), each of which involves the cardinal partitive phrase three of the lawyers that John hired associated with the existential presupposition that there are at least three individuals that are lawyers and that John hired.

-

(26)

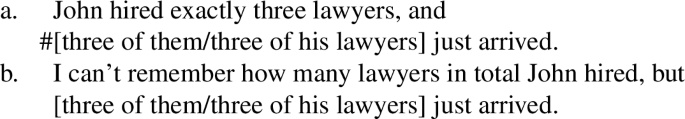

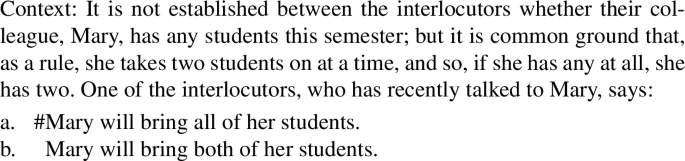

It has long been observed that the use of cardinal partitives is subject to an anti-maximality requirement (a.o., Jackendoff 1977; Hoeksema 1984; Barker 1998; Zamparelli 1998; Sauerland and Yatsushiro 2004, 2017; Marty 2017, 2019b). That is, the sentences in (26) can be felicitously used in a conversation only if it is not common ground that John hired exactly three lawyers. This observation can be further exemplified by the contrast in (27), adapted from Marty (2019b, (23)).

-

(27)

In (27a), the speaker makes it common ground that John hired exactly three lawyers, and this prevents the subsequent use of the partitive phrase three of John’s lawyers from being felicitous. By contrast, in (27b), the speaker is ignorant as to whether John hired exactly three or more lawyers, and the use of this same phrase is felicitous.

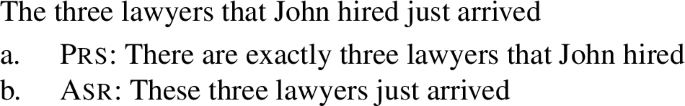

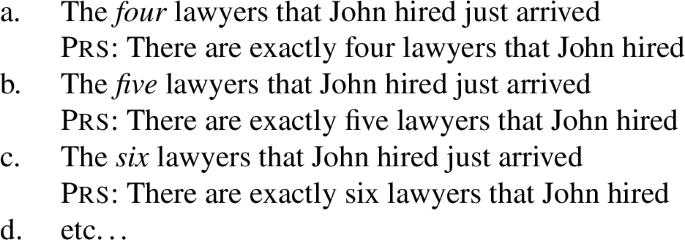

It has been proposed in Marty (2017, 2019b) that the anti-maximality condition on the use of those partitives follows from the general competition between indefinite phrases and their presuppositionally stronger definite alternatives, which has been traditionally subsumed under the scope of MP (cf. Heim 1991). In short, cardinal partitives like three of the lawyers that John hired are indefinite phrases headed by a silent indefinite determiner and compete with their definite cardinal variants, e.g. the three lawyers that John hired. Thus, a sentence like (26a) has the sentence in (28) as an alternative. This alternative carries a stronger presupposition but is equivalent, in its assertion part, to (26a) (i.e., in every context in which the presuppositions of (26a) and (28) are satisfied, the two sentences are equivalent).

-

(28)

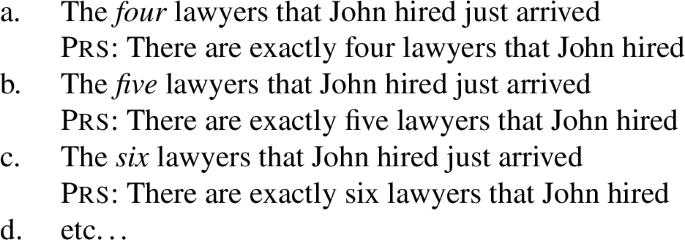

By MP, an utterance of (26a) is thus predicted to be felicitous only in contexts in which the presupposition of (28) is not satisfied, that is, if it is not common ground that John hired exactly three lawyers. It is worth noting here that MP does not impose any further requirement. In particular, note that the hypothetical alternatives to (26a) in (29), although similar in structure to (28) and presuppositionally stronger than (26a), are not contextually equivalent to (26a), and therefore they do not qualify as presuppositional competitors to (26a) in regard to MP.

-

(29)

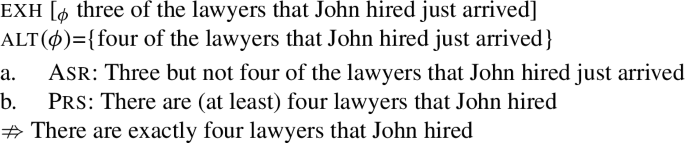

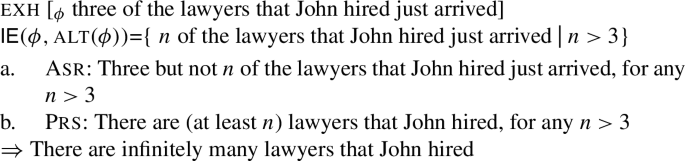

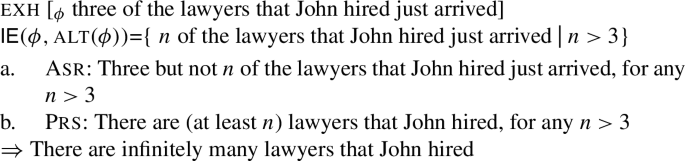

The situation changes, however, if one adopts the PIP in place of MP here: if we are to eliminate the condition on contextual equivalence, then all the definite alternatives to (26a) above are now expected to compete with (26a). Applying the PIP to (26a) on the basis of these alternatives amounts to generating, for each of these alternatives, an ignorance inference targeting their presuppositional content (e.g., ¬ CG(exactly three) & ¬CG(exactly four) & ¬ CG (exactly five), etc.). Summing up these inferences gives rise in the end to the following prediction: (26a) should be felicitous only if (a) it is common ground that John hired at least three lawyers (i.e., the plain presupposition of (26a)), but (b) it is not common ground how many lawyers John exactly hired (i.e., by application of the PIP). This prediction is, however, incorrect, as (26a) is fully felicitous in a context where the number of lawyer hired by John is known by the interlocutors.

-

(30)

Could it be then that the application of the PIP is blocked here by the application of exh? In the above case, it would be so for instance if there was an innocently excludable alternative to (26a) against which the meaning of (26a) could be exhaustified so as to add the presupposition that John hired exactly four lawyers, blocking in effect the application of the PIP. As we will now see, however, there is no such alternative to fulfil this role.

Consider first the formal alternatives to (26a) in (29). Those definite alternatives are all logically stronger than (26a) and, taken independently, any of these alternatives can be negated consistently with the plain meaning (26a). For instance, negating the four-alternative to (26a) in (29a) would give rise to the implicature that the four lawyers that John hired didn’t arrive, which would then add to (26a)’s presupposition the presupposition of interest, namely that John has exactly four lawyers. However, those alternatives cannot all be negated at the same time consistently with the plain meaning (26a) since the presuppositions associated with those alternatives are logically inconsistent with one another (i.e., John has exactly four lawyers, John has exactly five lawyers, John has exactly six lawyers, etc.). As a result, the definite alternatives to (26a) in (29) are not innocently excludable, and thus cannot be used to prompt scalar reasoning and block the application of the PIP.

Next, we note that sentences like (26a) also have indefinite cardinal alternatives such as (30), which are also logically stronger than them, both at the presupposition and at the assertion level:

-

(30)

Yet adding those alternatives to the picture does not solve the issue at hand. First, while exhaustifying the plain meaning of (26a) against the alternative in (30) would strengthen (26a)’s presupposition, as shown in (31), the representation resulting from this strengthening would still be presuppositionally weaker than the definite four-alternative in (29a), and therefore would not prevent the PIP from applying.

-

(31)

Second, while we illustrated the point above with four for simplicity, sentences like (26a) have in fact infinitely many indefinite alternatives of that sort, all of which are innocently excludable (e.g., five of the lawyers that John hired just arrived, six of the lawyers that John hired just arrived, etc.). Thus, the reasoning in (31) should apply in principle to any numeral n larger than three, in which case we would have exh negating all alternatives of the form n of the lawyers John hired arrived, for any n larger than three. Adding the presupposition of each of those negated alternatives, i.e. John hired at least 4, 5, 6, 7, … lawyers, is now going to entail that John hired infinitely many lawyers; this entailment is certainly not an inference that people draw upon hearing sentences like (26a).

-

(32)

In light of our discussion, one may still wonder whether a solution for this problem in S&S’s system would not be to stipulate that numerals may only compete with their immediate ‘neighbours’. On this view, the alternatives for ‘three’ would just be ‘two’ and ‘four’. Another way to formulate that idea would be to state that the closer a numeral is to the one used in exh’s prejacent, the more likely it is to contribute to alternatives (we thank Benjamin Spector for pointing this possibility out to us). That assumption, prima facie, would indeed permit one to account, for instance, for the case in (26a) by singling out the potential role of the definite four-alternative in (29a): if we are to preserve only the ‘two’ and ‘four’ alternatives to ‘three’, then the four-alternative in (29a) would become innocently excludable and its exclusion would block the PIP successfully.

As it stands, however, the above stipulation would face serious issues beyond the mere absence of an independent motivation. First, it cannot account for variants of (29a) such as (33). In order for the PIP to be blocked by scalar reasoning, the domain of exh would need here to include the definite alternative for ‘ten’, which is quite distant from ‘three’, and crucially to include only that definite alternative since, if other alternatives of the same sort were in exh’s domain (e.g., all alternatives up to ‘ten’), then that alternative would no longer be innocently excludable.

-

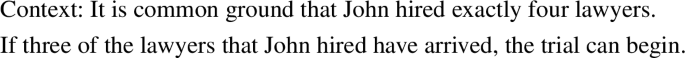

(33)

Second, the problem for Spector and Sudo (2017) would re-emerge in DE-environments. As before, embedding (26a) in a DE-environment as in (26c) does not change the picture: a sentence like (26c) can be felicitously used if it is common ground that John hired exactly n lawyers, for any n>3. Crucially, note that, as expected, the natural reading of (26c) does not have an embedded implicature; (26c) does not suggest that if three but not four/five/six/etc. of the lawyers that John hired arrived, the trial can begin.

-

(34)

The same observations hold for LI. The felicity of (26a) is unproblematic for LI since the definite alternatives in (29) are neither logically nor contextually entailed by (26a) in the given context. Yet the variant of (26a) in (26c) recreates the same problem for LI as above: (26c) does not logically entail the definite four-alternative in (34), but it does contextually entail it in contexts in which it is common ground that John hired exactly four lawyers. (26c) is therefore predicted to be infelicitous by LI, contra speakers’ intuitions.

-

(35)

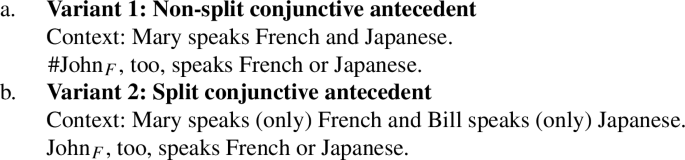

We now turn to a third set of overgenerating cases, which involve the restrictor of universal quantifiers and the restrictor of which-phrases, and the antecedent of conditionals.

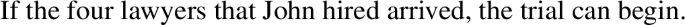

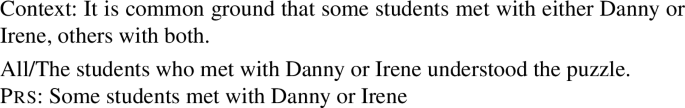

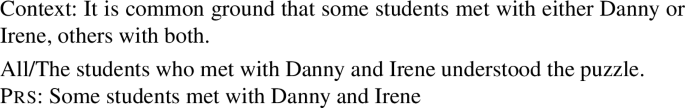

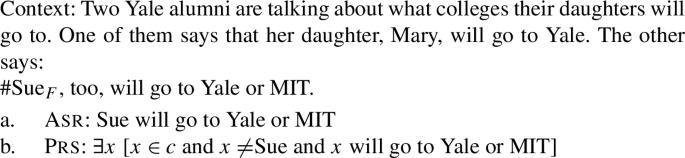

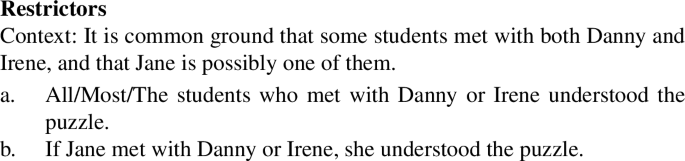

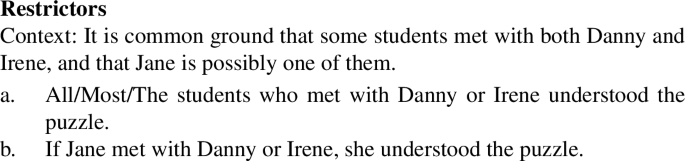

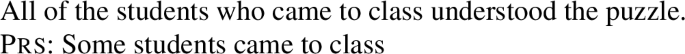

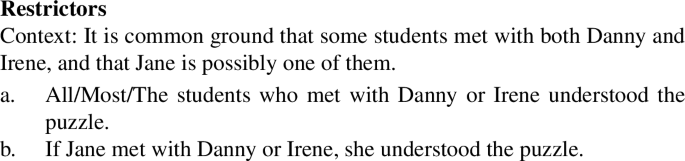

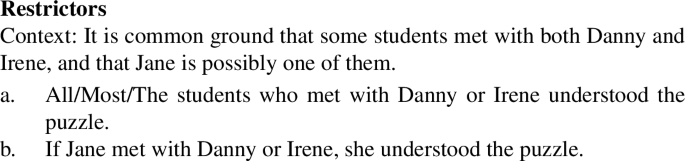

3.3 Case 3: Restrictors

A common assumption in the literature is that universally quantified sentences like (35), or definite descriptions like (36), require that their restrictor be non-empty. That is, (35) and (36) presuppose that there is at least one individual who is a student and came to class (see Heim and Kratzer 1998, Ch. 6, and references therein).

-

(36)

-

(37)

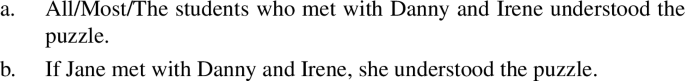

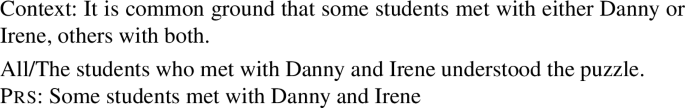

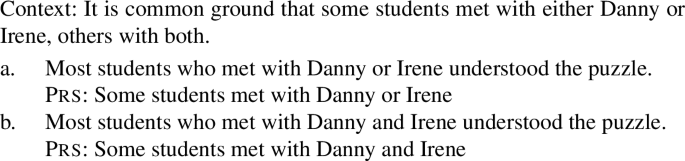

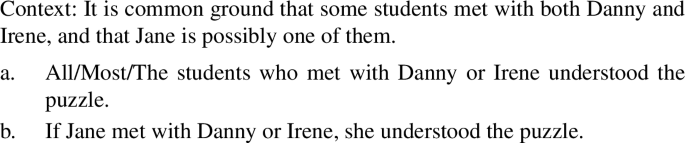

Consider now the variant in (37), which contains a disjunction in the restrictor of all/the:Footnote 12

-

(38)

(37) has the alternative in (38), which is assertively weaker and presuppositionally non-weaker than (37). Thus, according to the PIP, (37) should be felicitous only in contexts where the presupposition of (38) is not satisfied, that is, where it is not common ground that some student(s) met with both Danny and Irene. Yet this prediction is not borne out: as evidenced above, (37) is in fact felicitous in such contexts. Crucially, note that exhaustification cannot help in this case either: exh is vacuous if applied globally (i.e., at root level), and it would lead to an intuitively wrong meaning if applied locally (i.e., in the restrictor of all/the).

-

(39)

Similar data can be reproduced with the antecedent of conditionals, as shown in (39).Footnote 13 Thus for instance, (39a) has the alternative in (39b) which, in a way similar as above, is assertively weaker but presuppositionally stronger than (39a). Contra the predictions of the PIP, however, (39a) can be felicitously uttered in a context where (39b)’s stronger presupposition is met.

-

(40)

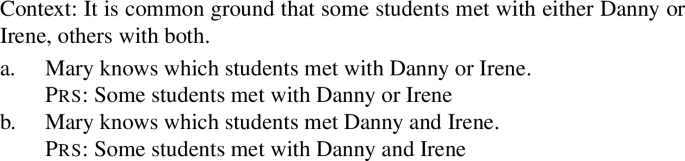

And the very same problem arises with the restrictor of which-phrases:

-

(41)

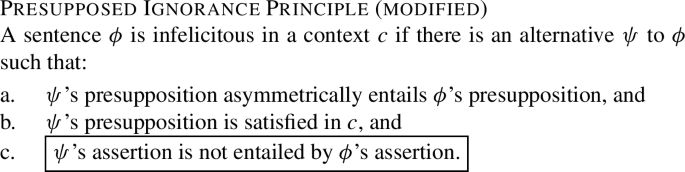

One could hope to address the issues above by restricting the scope of application of the PIP, for instance by restricting its application to alternatives whose assertive content is not entailed by the assertion of the base sentence, as suggested in (41).

-

(42)

The additional restriction in (41c) would take care of the universal quantifier cases above and, under certain assumptions about the semantics of conditionals and embedded questions, it might extend to those cases as well. However, the restrictor of the definite determiner the is a non-monotonic context and so, in contrast to the other cases, the presuppositionally stronger alternative is not entailed; in those cases, the same issue would thus arise even on the modified version of the PIP in (41). Similar data can be reproduced with other non-monotonic contexts, like the restrictor of most, as exemplified in (42). Here again, the problem is that the presuppositionally stronger alternative to (42a) in (42b) is not entailed by (42a), and so the issue re-emerges.

-

(43)

For similar reasons, LI makes incorrect predictions for these cases as well. This is because, in the given context, the sentences in (37), (39a), (40a), and (42a) contextually entail their and-alternatives, but do not logically entail them (i.e., these alternatives can be undefined given their presuppositions). Therefore, they are predicted to be infelicitous by LI; once again, this prediction is incorrect.

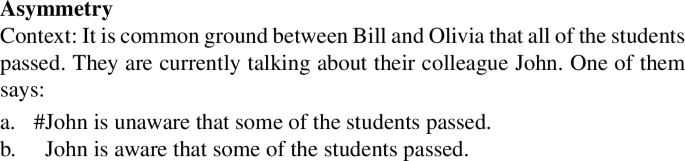

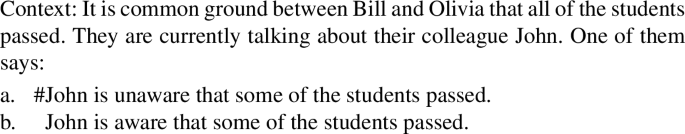

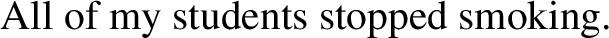

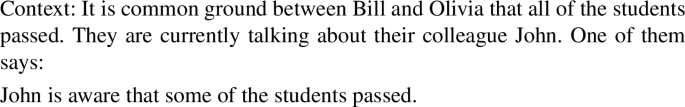

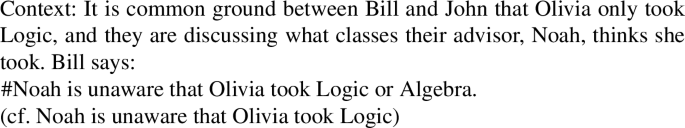

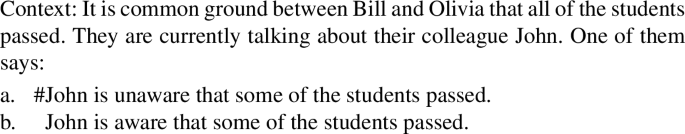

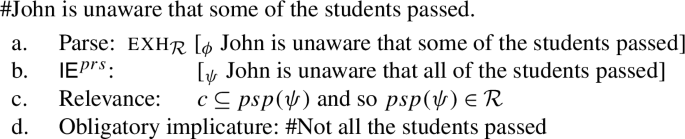

3.4 Case 4: Speaker-oriented ignorance

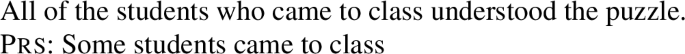

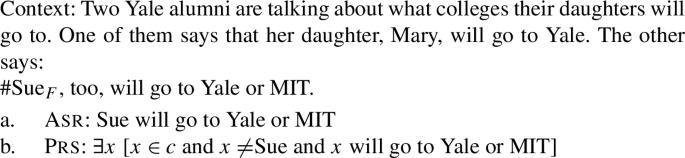

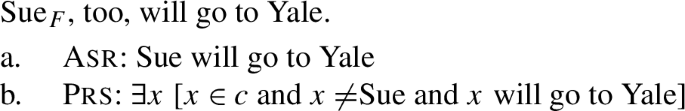

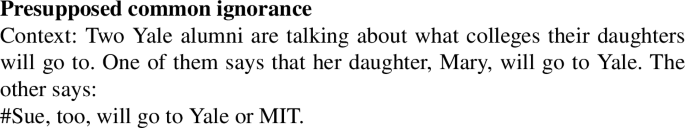

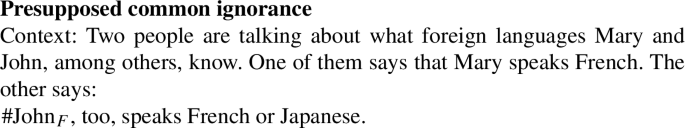

Our fourth and last set of cases shows that, when it comes to presupposed ignorance, S&S’s and Anvari’s proposals also face undergeneration issues. As a starting point, consider the example in (5a), which corresponds to the second case motivating S&S’s departure from contextual equivalence in favour of the PIP.

-

(44)

As we discussed, the infelicity of (5a) is left unexplained by MP or LI while it is accounted for by the PIP. The reason for that is that, unlike MP or LI, the PIP allows (5b) to be a presuppositional competitor to (5a). Hence, (5a) is expected to give rise through the PIP to the presupposed ignorance inference that it is not common ground that some contextually salient individual other than Sue, namely Mary, will go to Yale. This inference contradicts the common ground, since the interlocutors know that Mary will go to Yale, accounting for the infelicity of (5a).

-

(45)

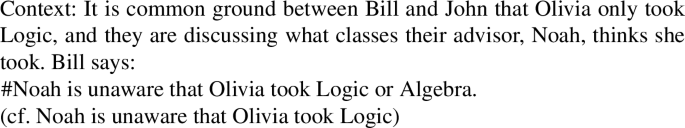

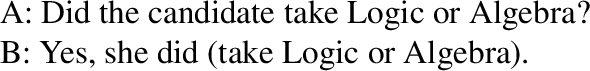

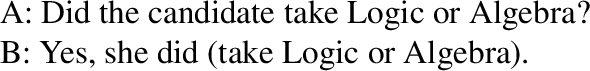

However, Marty and Romoli (2021) observe that the PIP fails to account for minimally different versions of (5a), which also involve disjunctive presuppositions. To illustrate, consider first the example in (43), which offers a different instance of the same problem:

-

(43)

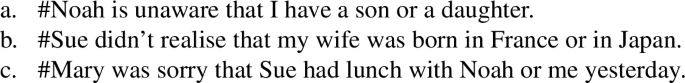

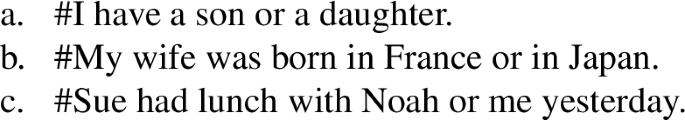

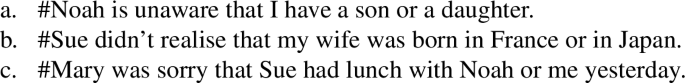

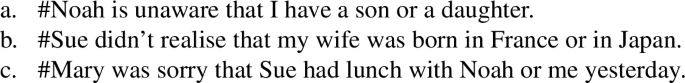

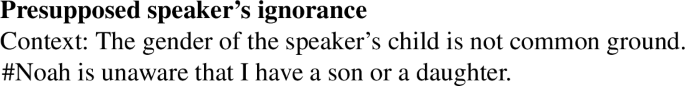

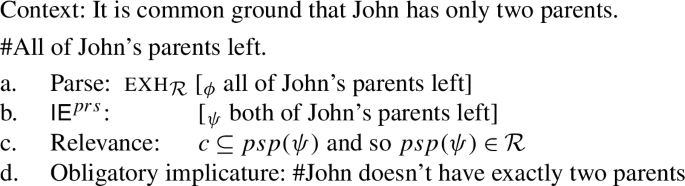

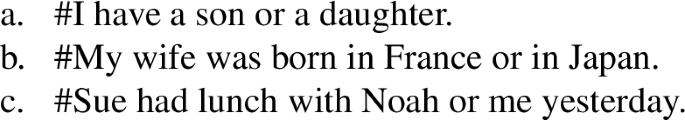

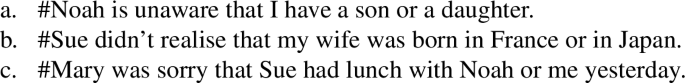

The observation here is simply that (43) cannot be felicitously uttered in a context in which it is established between the interlocutors that Olivia took Logic (or, alternatively, that Olivia took Algebra). It is easy to see that the PIP can account for this observation through the exact same reasoning as before: an utterance of (43) is infelicitous in the suggested context because, by application of the PIP, it gives rise to two inferences, ¬CG(Olivia took Logic) and ¬CG(Olivia took Algebra), one of which contradicts the common ground. Yet as Marty and Romoli (2021) argue, the explanatory challenge surrounding presupposed ignorance is more general. Specifically, they observe that similar infelicity effects reproduce in cases like (44), even though neither of the embedded disjuncts are common ground among the interlocutors. Thus for instance, in run-of-the-mill contexts, (44a) is infelicitous even if it is not common ground whether the speaker has children.Footnote 14

-

(44)

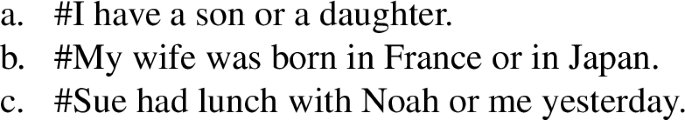

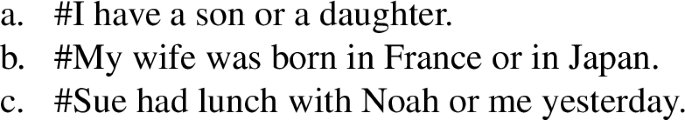

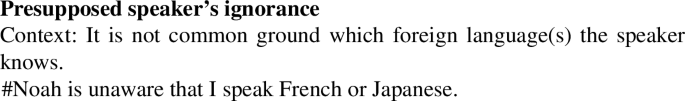

The infelicity effects at hand in these examples are in fact similar to those previously observed for their non-embedded, non-presuppositional variants in (45) (a.o., Gazdar 1979; Fox 2007; Singh 2008, 2010; Fox and Katzir 2011).

-

(45)

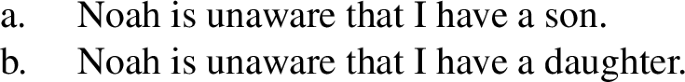

Taken at face value, all these examples appear to be infelicitous because they give rise to speaker-oriented ignorance inferences that stand in contradiction with common assumptions about what any speaker should know generally. That is, a sentence like (44a), just like its unembedded variant in (45a), sounds odd because it conveys that the speaker herself is ignorant about the gender of her child, and this piece of information conflicts with the common assumption that people are normally knowledgeable about such personal facts.Footnote 15 The problem, however, is that the PIP is not designed to mandatorily generate such speaker-oriented ignorance inferences. In fact, the PIP only generates for (44a) the inference that the gender of the speaker’s child is not common ground; the issue is that this inference is and remains compatible with the common ground as long as this information is not mutually shared by the interlocutors (e.g., if this information is not known to the speaker’s addressee). In sum, Spector and Sudo’s (2017) proposal only offers a partial solution to the empirical challenge of presupposed ignorance: it accounts for the infelicity effects in (5a) but leaves those of the variants in (44) unexplained.Footnote 16

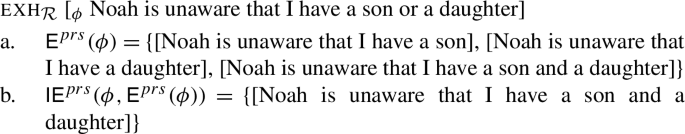

For completeness, we note that, for similar reasons, LI does not capture our variants of (5a) in (44): in a context in which it is not known whether the speaker has a son or a daughter, the formal alternatives to (44a) in (46) are neither logically nor contextually entailed by (44a). Hence, the LI approach does not account for the infelicity effects in (44) either.

-

(46)

3.5 Intermediate summary

We have presented several problematic cases for S&S’s and Anvari’s proposals. In the first three cases, we showed that both the PIP and LI overgenerate in predicting infelicity for felicitous sentences. In the fourth and last case, we showed that they also undergenerate by not capturing the infelicity of infelicitous sentences carrying disjunctive presuppositions. These findings leave us with the following dilemma at this point. On the one hand, none of the overgeneration cases that we discussed (Cases 1–3) are problematic for MP, for none of them involves a competition between contextually equivalent alternatives; but the scope of application of MP is too restrictive to capture S&S’s and Anvari’s novel cases and our variants above, including Case 4. On the other hand, the PIP and LI generalise MP by dropping or weakening the condition on contextual equivalence and successfully account for the asymmetry with factives unveiled by S&S; but their broader scope of application now leads to systematic overgeneration issues in Cases 1–3 above while, at the same time, undergenerating in Case 4, just like MP.

As a possible way out of this dilemma, we turn in the next sections to an alternative approach to MP, which proposes to broaden its scope of application while maintaining relatively strict conditions on competing alternatives. This approach is the implicature-based approach stemming from Magri 2009 and further developed in Marty 2017, 2019b, which, among other things, extends the application of exh to presuppositional competitors and subsumes the condition on contextual equivalence under the broader notion of relevance. As we explain below, that condition is further extended to the presuppositional level in the version in Marty 2019b and Marty and Romoli 2021. This approach also aims at capturing a broad class of unacceptable sentences, starting with the classical MP-cases. For space reasons, however, we will evaluate its empirical coverage only with regard to the target cases discussed in this paper: classical MP cases like (47), the PIP-motivating examples from S&S in (48) and (49) (which we call the ‘asymmetry’ and ‘presupposed common ignorance’ cases, respectively, for convenience), and our four new cases in (50)-(53).

-

(47)

-

(48)

-

(49)

-

(50)

-

(51)

-

(52)

-

(53)

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 4 introduces the implicature-based approach. By reintegrating the notion of contextual equivalence in some form, this approach can deal with one of our novel cases (the case of cardinal partitives in (52)), in addition to the classical MP ones and the asymmetry with factives; however, the cases in (51) and (53) still remain problematic for this approach, which is also insufficient by itself to account for the presupposed ignorance cases in (49)-(50). In Sect. 5, we show however that this latter limitation can be overcome: once we consider the grammatical approach to ignorance implicatures from Meyer 2013, the implicature-based approach offers a satisfying solution to the presupposed ignorance challenge (see also Marty and Romoli 2021). As we discuss, while Meyer’s (2013) proposal is also compatible with the PIP and LI, the resulting systems are unable to address the presupposed ignorance challenge in its full generality.

4 Moving to relevance

We will start by outlining the implicature-based approach to MP effects, building on Magri (2009) and Marty (2017, 2019b). We will refer to this approach as the M&M system. This system integrates contextual equivalence within a notion of relevance, allowing it to account for the classical MP-cases in the same way as the original MP approach, and further applies that notion of relevance at the presupposition level. The resulting approach accounts for the asymmetry in (48) as well as for the case of cardinal partitives in (52). Yet the existential presuppositions and restrictor cases will be shown to remain problematic for this approach as well.

4.1 The proposal in brief

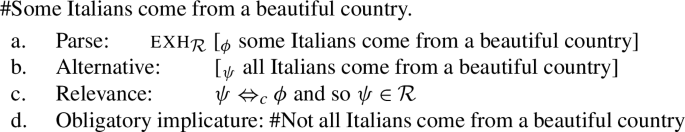

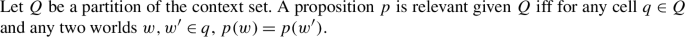

On the theory of implicatures developed in Magri 2009, 2011, 2013, the infelicity of a sentence like (54) is hypothesized to result from the mandatory computation of a mismatching implicature, that is, an obligatory implicature which contradicts the common ground.

-

(54)

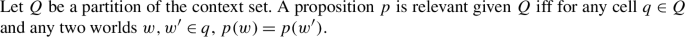

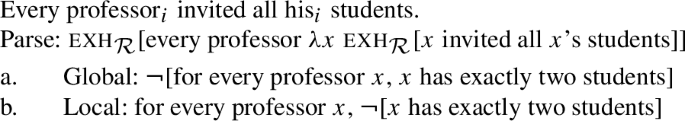

The gist of Magri’s theory is that a sentence like (54) must be parsed with an exhaustivity operator, (54a). Just like any other quantifier, the domain of this operator is taken to be restricted by a contextually assigned relevance predicate ℛ; the exhaustivity operator with its restriction is written ‘exh\(_{\mathcal{R}}\)’. The denotation of ℛ is assigned by the context of exh’s prejacent and thus varies across contexts, accounting for the context-dependency of implicatures, i.e., for the possibility of suspending an implicature in certain contexts but also for the impossibility of doing so in others.Footnote 17 In particular, since relevance is assumed to be closed under contextual equivalence, if the prejacent ϕ of exh\(_{\mathcal{R}}\) in (54a) is relevant, then so is its all-alternative ψ in (54b), since ψ and ϕ are contextually equivalent relative to ϕ’s context (corresponding here to the global context c). As a result, the implicature associated with ψ becomes mandatory in this case, resulting in a representation that contradicts the common ground (i.e., \(c\cap \textsc {exh}_{\mathcal{R}}(\phi)=c\cap(\phi\wedge\neg\psi)=\emptyset\)). In addition to relevance considerations, the domain of quantification of exh is also regulated by general economy considerations (a.o., Fox and Spector 2009; Magri 2011; Spector and Sudo 2017; Fox and Spector 2018): since the computation of an implicature must lead to meaning strengthening, an alternative that can be pruned from the domain of exh must effectively be pruned if the implicature associated with that alternative would weaken or leave unaffected the global meaning of the sentence.

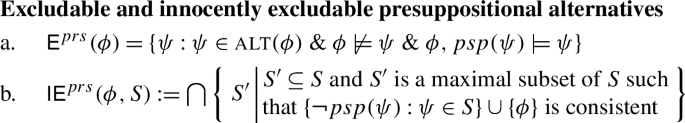

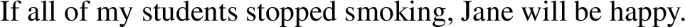

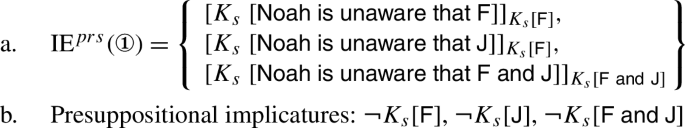

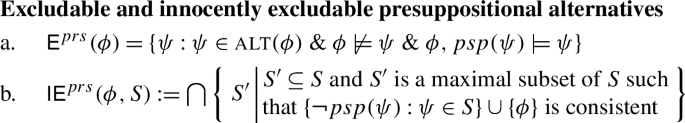

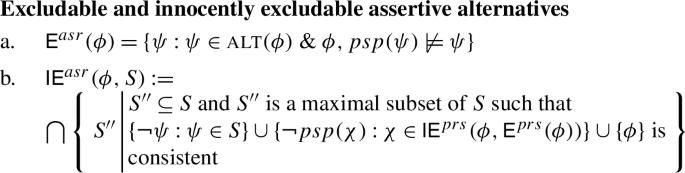

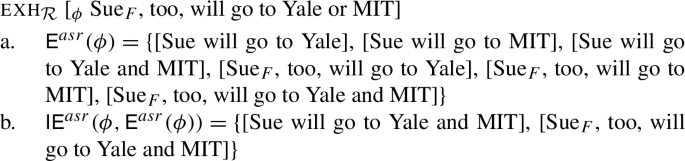

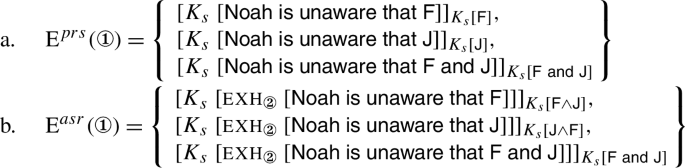

Building on Magri’s insights, Marty (2017) proposes to extend this theory to presuppositional effects.Footnote 18 In essence, Marty (2017) argues that, when computing the implicatures of a sentence ϕ, speakers entertain two sets of alternatives that are mutually exclusive and distinguished on the basis of Strawson-entailment: (i) a set of presuppositional alternatives, comprising the formal alternatives to ϕ that can only be undefined when ϕ is true (i.e., those alternatives that are Strawson-entailed), as in (55a) below, and (ii) a set of assertive alternatives, comprising the formal alternatives to ϕ that can be false when ϕ is true (i.e., those alternatives that are not Strawson-entailed), as in (56a).Footnote 19 As Marty (2017) discusses, on this proposal, we need exclusion to be performed innocently on both sets of alternatives. For presuppositional alternatives, we adopt the procedure of innocent exclusion (\(\mathsf{IE}^{prs}\)) proposed in Marty (2017), shown in (55b), which applies Fox’s (2007) notion to the presuppositional domain. For assertive alternatives, we follow Marty and Romoli (2021) in assuming that innocent exclusion (\(\mathsf{IE}^{asr}\)) is computed as shown in (56b), by taking all maximal sets of assertive alternatives that can be negated consistently with the prejacent and the negation of the presupposition of all \(\mathsf{IE}^{prs}\) alternatives. This second definition slightly departs from Marty (2017) in that \(\mathsf{IE}^{asr}\) is computed on the basis of \(\mathsf{IE}^{prs}\) rather than independently.

-

(55)

-

(56)

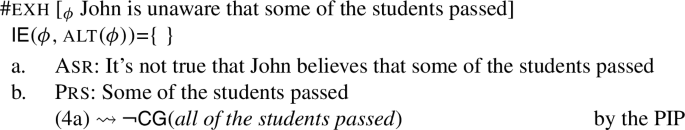

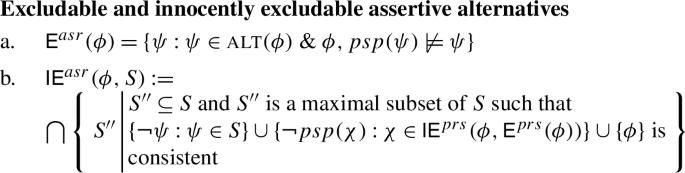

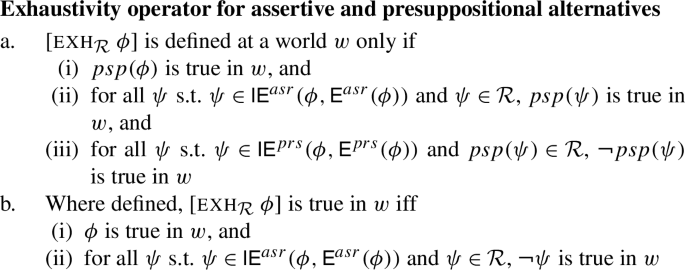

Following this characterisation of assertive and presuppositional alternatives, Marty (2017) proposes that the exhaustivity operator be defined as in (57).

-

(57)

In this framework, applying exh to a sentence ϕ can strengthen ϕ’s presupposition in one of two ways.Footnote 20 First, in a way similar to Spector and Sudo’s (2017) proposal, presupposition strengthening can happen indirectly upon projection of the presupposition of \(\mathsf{IE}^{asr}\) alternatives: \(\textsc {exh}_{\mathcal{R}}\) passes up to the whole sentence the presuppositions of the negated \(\mathsf{IE}^{asr}\) alternatives to the prejacent, as shown in (57a). Second, presupposition strengthening can happen as a direct result of an implicature: here too, \(\textsc {exh}\) passes up to the whole sentence the negation of the relevant presuppositions of the \(\mathsf{IE}^{prs}\) alternatives to its prejacent, as in (57a).

Finally, M&M’s system inherits from Magri’s original system the idea that exh’s domain is modulated both by relevance and economy considerations. In particular, with respect to relevance, if the prejacent ϕ of exh is relevant, then any assertive alternative to ϕ that is contextually equivalent to ϕ is also relevant (Magri 2009, 2011). Conversely, if ϕ is not relevant to begin with, then \(\textsc {exh}(\phi)\) is infelicitous. This logic is extended in Marty 2019b and Marty and Romoli 2021 to presuppositional alternatives by assuming that, for those alternatives, speakers assess relevance by considering the relevance of their presuppositional contribution.Footnote 21 For our immediate purposes, it is enough to observe that, given the way the notion of relevance is usually defined in the literature, if a proposition is entailed by the context, then that proposition trivially counts as relevant. As a result, if the prejacent ϕ of exh is assertable in a context c (i.e., if c entails ϕ’s presupposition), then ϕ’s presupposition is relevant in c and so are the presuppositions of ϕ’s presuppositional alternatives that are contextually equivalent to ϕ’s presupposition. Conversely, if ϕ is not assertable to begin with, e.g., ϕ’s presupposition isn’t met prior to utterance and fails to be accommodated, then \(\textsc {exh}(\phi)\) is infelicitous. Crucially, if an assertive alternative or the presupposition of a presuppositional alternative is deemed relevant in that sense, it cannot be pruned from ℛ and thus from the domain of exh; consequently, any assertive or presuppositional implicature associated with such an alternative is predicted in M&M’s system to be mandatory.

4.2 Good predictions

First, M&M’s system readily accounts for the classical MP effects. To illustrate, consider the sentence in (47a), which is parsed with an occurrence of the exhaustivity operator at matrix level, as shown below. The presuppositional both-alternative to exh’s prejacent is innocently excludable and, since its presupposition is satisfied in the suggested context, its presupposition counts as relevant and thus must be excluded. In a way similar to what we saw in (54), the mandatory computation of this implicature results in a contextually contradictory representation; infelicity follows.Footnote 22

-

(58)

On certain assumptions, M&M’s system can also account for variants such as (13), repeated below, which have been pointed out as a challenge to presupposition satisfaction:

-

(59)

In fact, a solution to this challenge preserving the original formulation of MP has already been put forward in Marty 2019a. This solution starts from the observation that, in order for (13a) to be felicitous, two requirements must be met: (i) for the informative presupposition of (13a) to be satisfied, the context must be adjusted so as to entail that Mary has students (e.g., by presupposition accommodation), and (ii) for MP to be obeyed, the local context to which (13a) is added should not entail (13b)’s stronger presupposition that Mary has exactly two students. As Marty 2019a observes, however, these felicity conditions cannot be met altogether in cases like (13): if (i) is met, then it follows that (ii) isn’t, and so infelicity ensues by MP; alternatively, if (ii) is met, then it follows that (i) isn’t, and so infelicity ensues due to presupposition failure. This solution can easily be integrated with M& M’s system as well as with the PIP. Thus for instance, on this solution, (13a) is predicted to be infelicitous in M&M’s system because either (13a)’s presupposition is accommodated, in which case the presupposition of (13b) is relevant in the context of evaluation and a mismatching presuppositional implicature arises, or else (13a)’s presupposition fails to be accommodated, in which case (13a) suffers from presupposition failure.

Second, M&M’s system offers a simple solution to the issue raised by cardinal partitives: of all the definite alternatives to indefinite partitives of the form ‘n of the NPs’, only the one of the form ‘the n NPs’ qualifies as a presuppositional alternative by the definition given in (55). All other definite alternatives qualify instead as assertive alternatives and are not innocently excludable since negating them all upon exhaustification would project presuppositions that are mutually inconsistent (e.g., John has exactly 4 and exactly 5 lawyers). Consequently, in a way similar to MP, M&M’s system correctly predicts (52a) and (52b) to be infelicitous only in those contexts in which John is known to have hired exactly 3 lawyers, i.e., in contexts in which the presupposition of their definite three-alternative is satisfied.

-

(60)

Finally, the M&M approach accounts for the asymmetry with factives from Spector and Sudo (2017). Consider again the contrast in (48), repeated below for convenience:

-

(61)

In M&M’s system, this contrast stems from the different status of the target all-alternatives in both cases. In (48a), the target all-alternative is a presuppositional alternative to exh’s prejacent: upon exhaustification, the negation of its (stronger) presupposition can be added to the plain presupposition of exh’s prejacent. In the present case, since the presupposition of the presuppositional all-alternative to exh’s prejacent is satisfied, this strengthening is mandatory and results in a contextual contradiction, hence the infelicity of (48a).

-

(62)

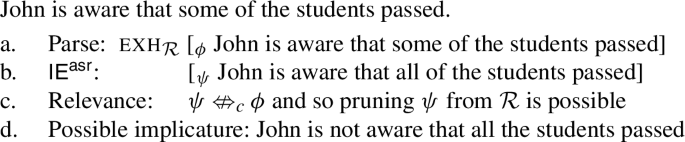

In (48b), by contrast, the corresponding all-alternative is an assertive alternative to exh’s prejacent: upon exhaustification, its presupposition and the negation of its (stronger) assertion can be added to the plain meaning of exh’s prejacent. Note that, in the absence of contextual equivalence, this strengthening process is predicted to remain optional.

-

(63)

M&M’s account of the contrast in (48) is therefore similar to Spector and Sudo’s (2017). In particular, both accounts predict the sentence in (48a) to be odd due to the mandatory generation of some conflicting inference (attributed to the working of the PIP in one case, and to the working of exh in the other), while no such conflict need to arise in (48b).

In closing, we note that the two accounts nonetheless make different predictions regarding two issues surrounding the felicity conditions of (48b). The first issue has to do with focus sensitivity: S&S argue that, in a context in which it is common ground that all of the students passed, the scalar term some needs to be stressed in order for (48b) to be felicitous. That is, while (58a) is felicitous in such contexts, (58b) isn’t:

-

(58)

On S&S’s approach, this contrast follows if one assumes that prosodic prominence on the scalar term strongly correlates with the presence of exh. In (58a), since some is stressed, scalar strengthening happens and the sentence is predicted to be felicitous. In (58b), by contrast, some isn’t stressed and, in the absence of scalar strengthening, the sentence is predicted to be infelicitous through the PIP. On M&M’s approach, on the other hand, the implicature is predicted to remain optional in this case, given the absence of contextual equivalence with the target assertive alternative. This approach can thus account for the fact that stress on some, signalling the active work of exh, is the most natural choice in the given context. It can also account for why (58b) is felicitous in a context in which it is not common ground that all of the students smoke. However, it does not readily account for the robust infelicity of (58b). The contrast in (58) seems therefore to favour S&S’s approach.

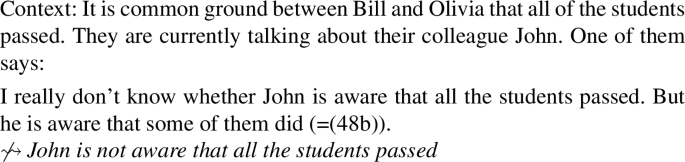

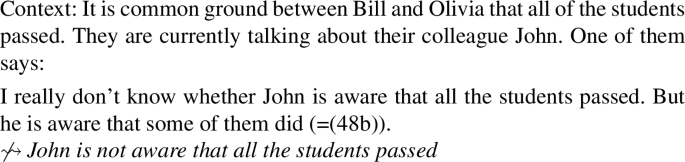

The second issue also pertains to the obligatoriness vs. optionality of the implicature associated with (48b). This time, however, it is the M&M approach which appears to make the right prediction. In particular, Spector and Sudo’s (2017) account predicts that, in order for (48b) to be felicitous in the context at hand, an implicature must be computed to avoid the PIP from generating a contextual contradiction. By contrast, M&M’s account predicts (48b) to be felicitous in that same context independently from such a strengthening process. With this in mind, consider the example in (59):

-

(59)

As before, the context at hand is one in which it is common ground that all of the students passed. However, the speaker is now explicitly stating that he is ignorant as to whether John is aware that all the students passed, and this information subsequently leads one to suspend the implicature previously associated with (48b). Crucially, we observe here that the suspension of that implicature leaves the felicity of (48b) unaffected. This is directly in line with M&M’s predictions but problematic at first sight for Spector and Sudo (2017): in the absence of the target implicature, the PIP should apply just like in (48a), and therefore the discourse in (59) should be perceived as infelicitous, contra speakers’ intuitions.Footnote 23

In sum, the two issues above have to do with the obligatoriness vs. optionality of the implicature associated with sentences like (48b), in a context in which the presupposition of the alternative is or is not satisfied. The first issue suggests a strong correlation between the presence of focus, the generation of the target implicature, and the felicity of (48b), while the second reveals that (48b) can be felicitous also in the absence of that implicature. S&S’s approach easily accounts for the former but not the latter issue, while M&M’s approach easily accounts for the latter but not the former.

4.3 Presupposed ignorance unexplained

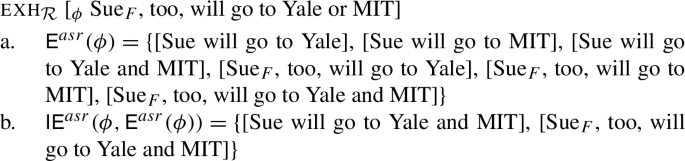

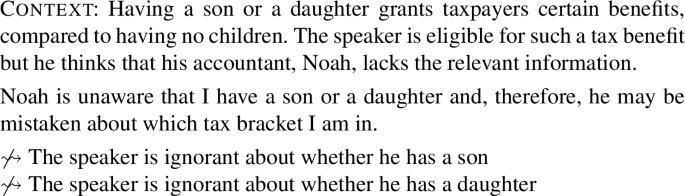

Without further assumptions, the M&M approach cannot account for the presupposed ignorance cases in (49)-(50). To illustrate, consider the example in (49), which is parsed on this approach as shown in (60): of all the excludable assertive alternatives to (49), only the two conjunctive alternatives qualify as innocently excludable alternatives. Neither of those assertive alternatives is contextually equivalent to their base disjunctive sentence and, more to the point, neither of the implicatures associated with those alternatives has the potential to give rise to a contextual contradiction.

-

(60)

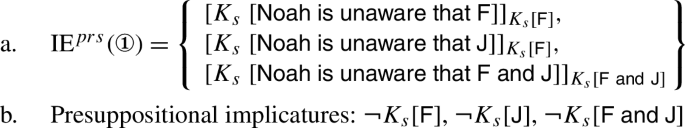

Similar observations hold of the speaker-oriented variant in (50), as illustrated in (61): of the three excludable presuppositional alternatives to (50), only the (presupposition of the) conjunctive one is innocently excludable. The resulting presupposed implicature (i.e., that the speaker doesn’t have both a son and a daughter) is not in conflict with the common ground and cannot, therefore, account for the infelicity of (50).

-

(61)

For now, the presupposed ignorance cases constitute a challenge for M& M’s system, which is not equipped to operate on scalar alternatives involving independent disjuncts. We will see in Sect. 5 that this limitation can yet be overcome by combining M&M’s system with Meyer’s (2013) grammatical approach to ignorance implicatures.

4.4 Remaining overgeneration problems

While M&M’s system can account for the case of cardinal partitives, it encounters similar overgeneration issues as the PIP and LI for the other two cases. Consider first the case of existential presuppositions, repeated from above:

-

(62)

Like the other two approaches, M&M’s system can readily account for the felicity of (51a): the all-alternative to (51a) in (62) is an assertive alternative to (51a), and that alternative is not contextually equivalent to (51a). As a result, the meaning of (51a) may but need not be exhaustified on the basis of (62): (51a) is correctly predicted to be felicitous either way.

-

(63)

However, the minimal variant of (51a) in (51b) is problematic for this approach as well. To understand why, consider the all-alternative to (51b) in (63). First, we verify that (63) is logically non-weaker, yet Strawson-entailed by (51b); therefore, it counts in M&M’s system as a presuppositional alternative to (51b). Second, the presupposition of (63) (i.e., all of my students used to smoke) and that of (51b) (i.e., some of my students used to smoke) are satisfied in the suggested context; therefore, the computation of the presupposed implicature associated with (63) is predicted to be mandatory.Footnote 24 Since the resulting implicature (i.e., not all of my students used to smoke) conflicts with the context, M&M’s system predicts (51b) to be infelicitous, which is incorrect.

-

(64)

A similar problem arises when we move to the case of restrictors:

-

(65)

Consider the alternatives to (53a) and (53b) in (64a) and (64b), respectively. In M&M’s system, those alternatives count as presuppositional alternatives and, moreover, their presuppositions are satisfied in the context at hand. As a result, the presupposed implicatures associated with those alternatives are predicted to be obligatory and, since those implicatures conflict with the contextual assumptions, both (53a) and (53b) are incorrectly predicted to be infelicitous.

-

(66)

To summarise, M&M’s approach can account for the original MP cases, for the factive asymmetry from Spector and Sudo (2017), as well as for the case of cardinal partitives. However, it leaves presupposed ignorance unaccounted for at this point, and it faces the same problems as the PIP and LI with existential presuppositions and restrictors. While the first issue can be remedied by enriching M&M’s approach, as we shall now see, the latter will remain a problem.

5 Extension to presupposed ignorance

In this section, we go back to the various challenges posed by presupposed ignorance, by investigating in more detail the common and speaker-oriented ignorance cases as well as further variants. We show that a unified solution to all of these cases can be given by integrating Meyer’s (2013) grammatical view on ignorance implicatures with the M&M approach. As we discuss, while Meyer’s (2013) proposal is also compatible with the PIP and LI, the resulting systems are unable to account for all the cases of presupposed ignorance as they stand.

5.1 The challenge in more detail

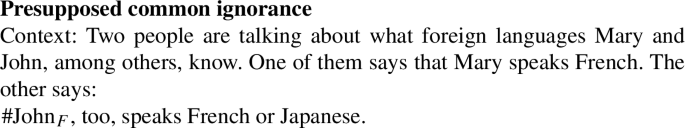

Consider first the case in (65), which illustrates what we have referred to as presupposed common ignorance (e.g., (49)):

-

(67)

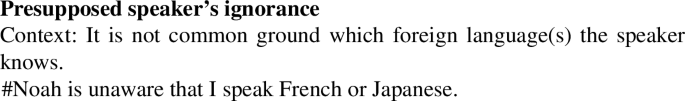

As we discussed, of all the approaches we considered, only the approach by S&S can account for the infelicity of such sentences. However, just like the other approaches, it fails to account for the speaker-oriented variant of (65) in (66).

-

(68)

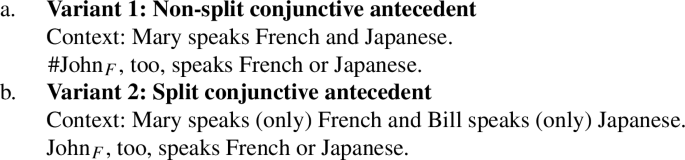

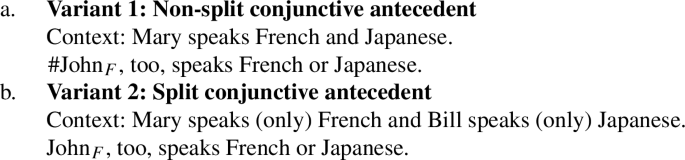

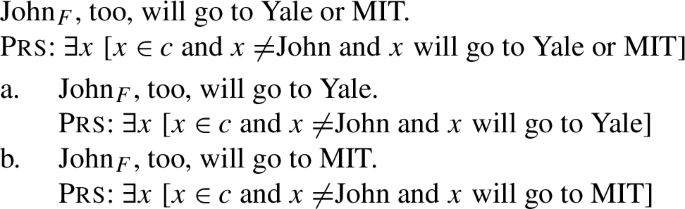

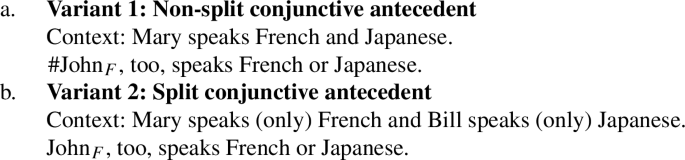

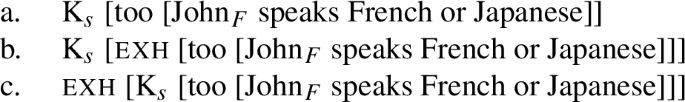

In this subsection, we add the observation that the S&S approach also runs into problems with minimally different versions of (65). Consider for instance the following two variants, which are to be read in a general context similar to the one in (65):Footnote 25

-

(67)

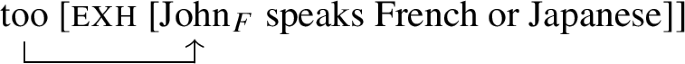

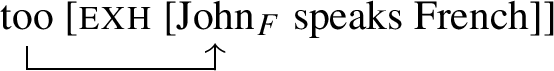

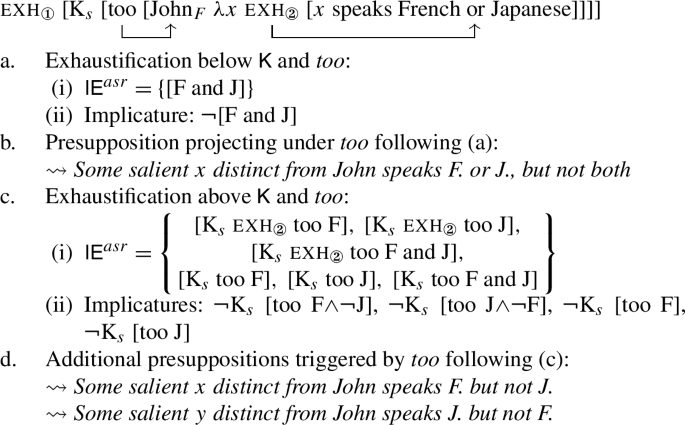

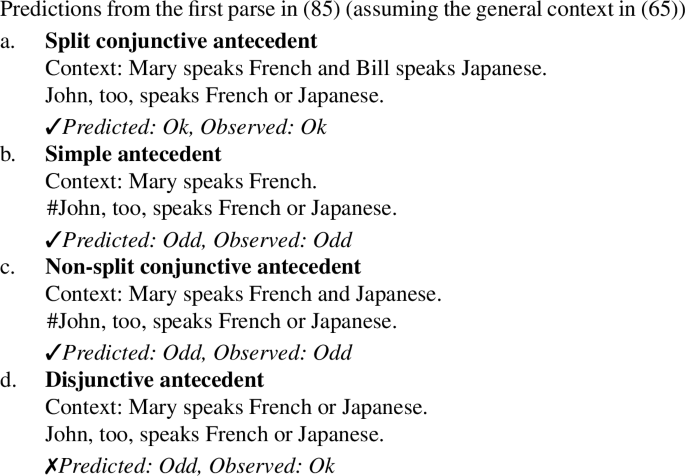

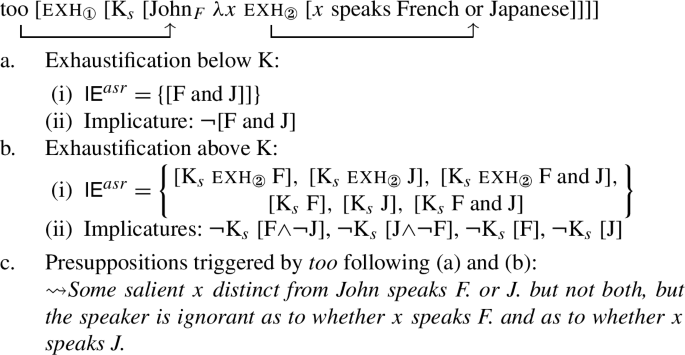

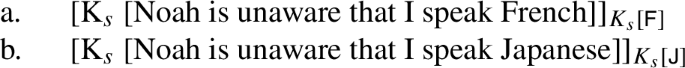

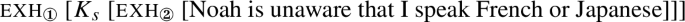

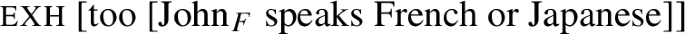

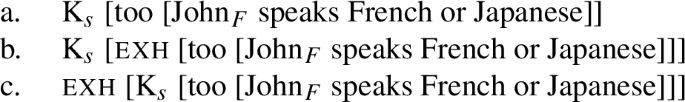

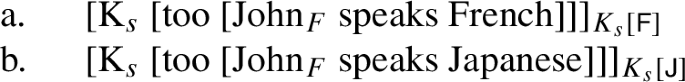

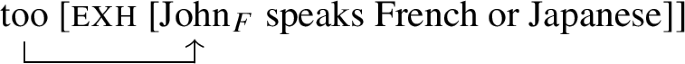

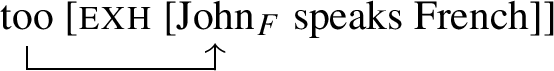

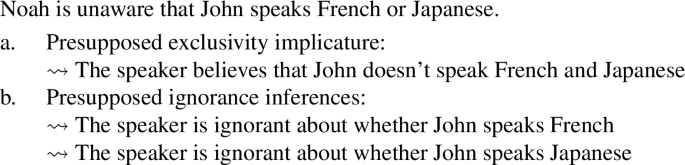

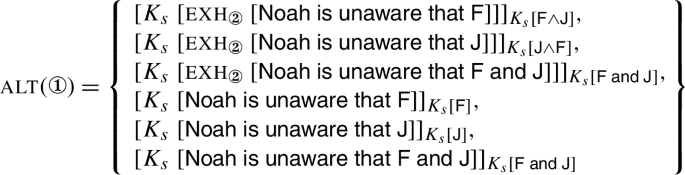

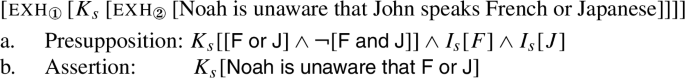

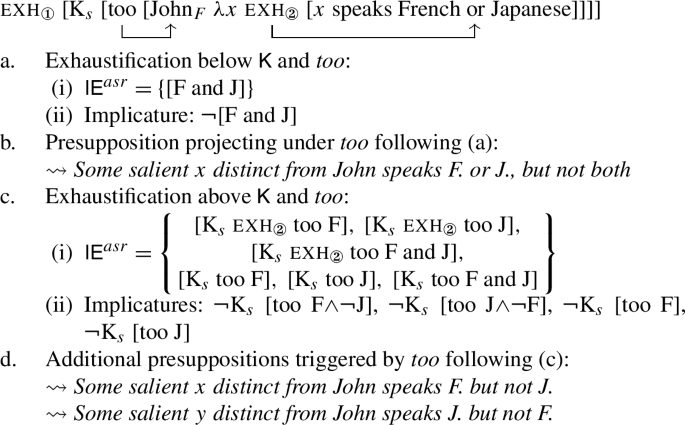

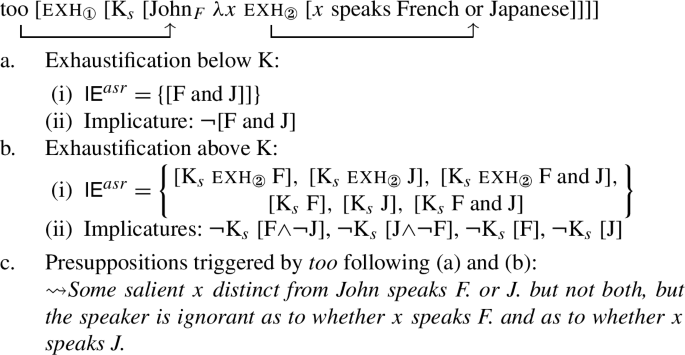

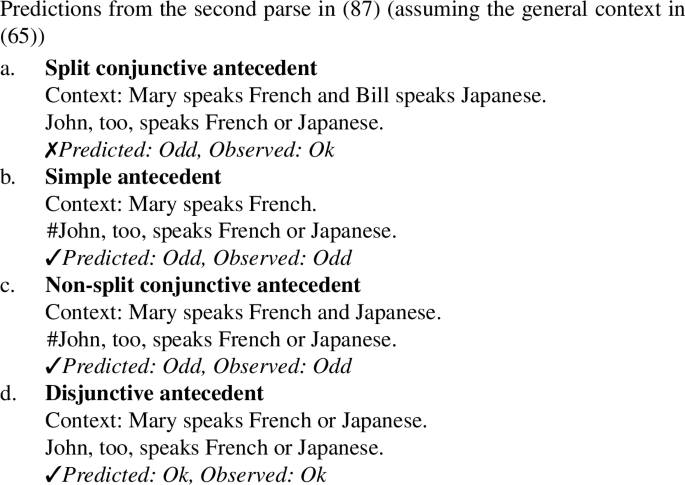

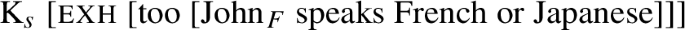

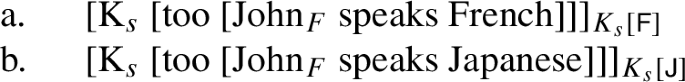

As S&S themselves discuss, their approach does not capture the infelicity effect in (67a) in that it predicts (67a) to be infelicitous under certain parses, but not others. Specifically, if (67a) is parsed without any occurrence of exh, it is predicted to be infelicitous by the PIP because the alternatives (i) JohnF, too, speaks French and Japanese, (ii) JohnF, too, speaks (only) French, and (iii) JohnF, too, speaks (only) Japanese all have stronger additive presuppositions that are met in context. Similarly, if (67a) is parsed with an occurrence of exh taking scope below too, as in (68), the predicted presupposition is that there is a salient x other than John such that x speaks French or Japanese, but not both. As one can verify, this presupposition is false in the suggested context since the only salient x is Mary and, by assumption, she is known to speak both languages.

-

(68)

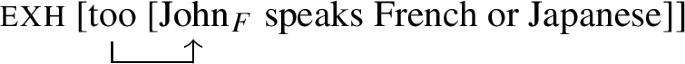

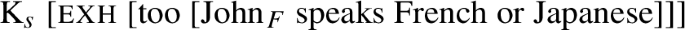

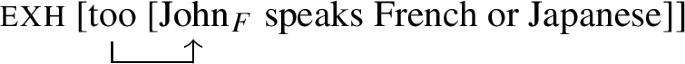

The problem is that there is also a possible parse for (67a), namely (69), under which the sentence is predicted to implicate that John speaks one language or the other but not both, while presupposing that there is some salient x other than John which speaks both (i.e., the presupposition of the negated alternative JohnF, too, speaks French and Japanese). Since this presupposition is also satisfied in the suggested context, (67a) is incorrectly predicted to be felicitous under this parse (see Spector and Sudo 2017, Sect. 6.4).

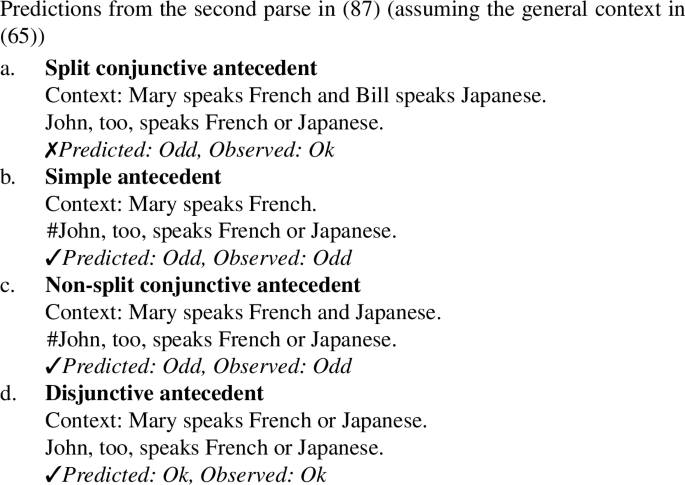

-

(69)

The variant in (67b) raises another non-trivial issue for S&S, because their approach incorrectly predicts (67b) to be infelicitous, on all relevant parses. First, if (67b) is parsed without any occurrence of exh, it is predicted by the PIP to be infelicitous for the same reasons as above. Next, if we assume the parse in (69), then the predicted presupposition is, as before, that someone other than John speaks both languages; this time, however, this presupposition is false in the given context, since neither Mary nor Bill speaks both languages. Finally, if we assume the parse in (68), the predicted presupposition is that somebody other than John speaks French or Japanese, but not both. This presupposition is satisfied in the context, no matter whether this somebody is understood to be Mary or Bill. However, regardless of the choice of the antecedent, (67b) has on this parse certain alternatives whose presuppositions are logically stronger and are satisfied in the context. Thus for instance, the alternative in (70) presupposes that some salient individual other than John has the property of speaking only French, a property that Mary is known to have in the given context. Therefore, the PIP shall apply in this case, incorrectly predicting the sentence in (67b) to be infelicitous.Footnote 26

-

(70)

In sum, S&S’s approach accounts for the basic case in (65), but it fails to extend to its speaker-oriented variants and to account for its variants in (67a) and (67b), by incorrectly predicting the former to be felicitous and the latter to be infelicitous (at least under certain assumptions; see fn. 26 for discussion). In light of those data, in the following we propose an alternative account of (65) and of its variants that extends a proposal by Meyer (2013) and integrates it with the M&M approach.

5.2 An exhaustivity-based solution

5.2.1 A grammatical epistemic layer

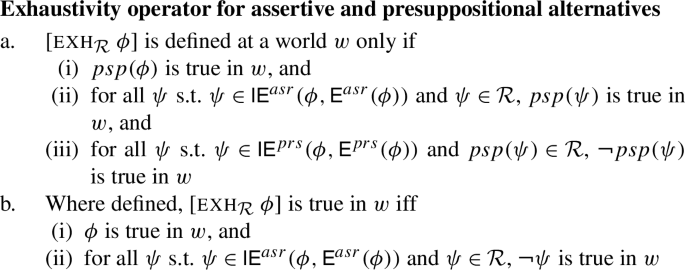

One common way to account for ignorance inferences is to conceive them as implicatures derived from additional Gricean principles (a.o., Gazdar 1979; Sauerland 2004; Fox 2007, 2016). Meyer (2013) proposes instead that ignorance inferences are derived in the grammar through the interaction of the exhaustivity operator with another covert operator representing the speaker’s beliefs (see also Meyer 2014; Buccola and Haida 2019). At the core of Meyer’s proposal is the assumption — called the Matrix K Axiom — that assertively used sentences contain a covert doxastic operator K, which is adjoined at the matrix level at LF (cf. Chierchia 2006; Alonso-Ovalle and Menéndez-Benito 2010). Much like the attitude verb believe, the Matrix K operator universally quantifies over the speaker’s doxastic alternatives, as shown in (71). The subscript x refers to the doxastic source, i.e., the individual whose beliefs K is quantifying over. In the cases that we will be concerned with, x will always be the speaker, hence the notation \(K_{s}\).Footnote 27

-

(71)

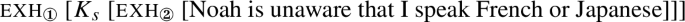

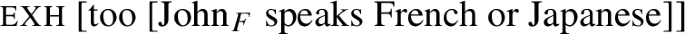

Meyer shows that the Matrix K Axiom, together with the possible adjunction of exh at any propositional node (i.e., below and above K), derives speaker-oriented ignorance inferences. To illustrate, consider the simple disjunctive sentence in (72):

-

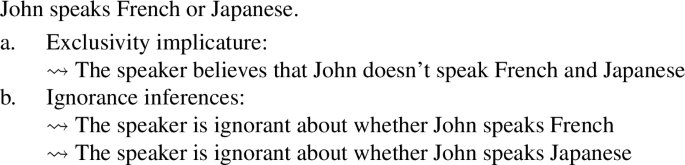

(72)

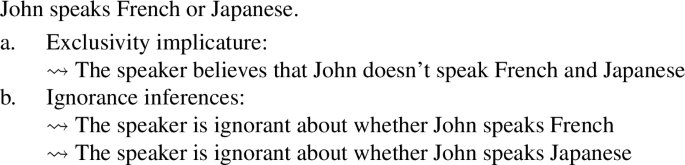

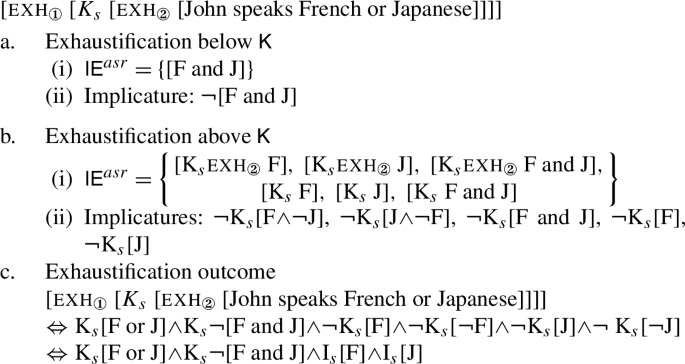

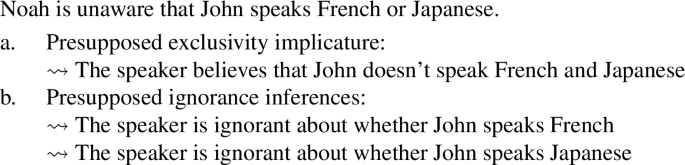

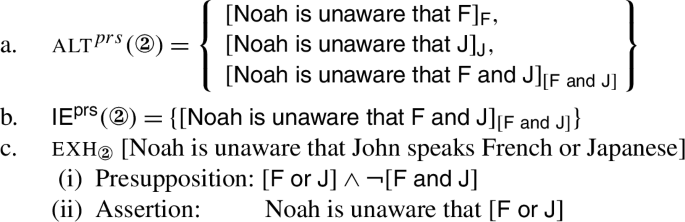

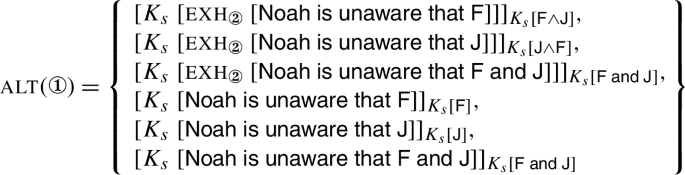

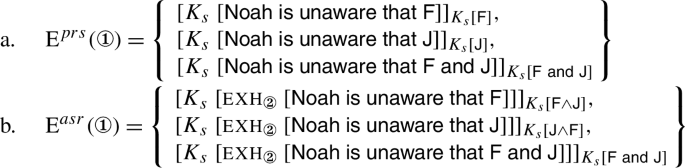

Sentences like (72) are typically understood as conveying that (a) the speaker believes that John doesn’t speak both French or Japanese, and (b) the speaker is ignorant about whether John speaks French and about whether John speaks Japanese. The inference in (a) corresponds to the genuine exclusivity implicature arising from the basic competition between disjunction and conjunction. The inferences in (b) are called ignorance inferences and are generally derived on the basis of the competition between the whole disjunction and its independent disjuncts: a disjunction ‘ϕ∨ψ’ generates speaker-oriented ignorance inferences about ϕ and about ψ (e.g., Gazdar 1979). As Meyer shows, the pattern of inferences in (72) can be derived on her proposal with the parse given in (73).Footnote 28,Footnote 29

-

(73)

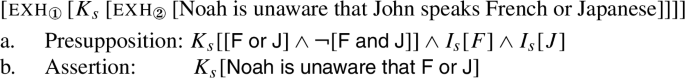

On the parse in (73), exhaustification is performed at two distinct levels, below K and above K. Exhaustification below K gives us the classic not-and implicature: this implicature obtains as usual by negating the conjunctive alternative to exh②’s prejacent, which is the only innocently excludable alternative at that level of the structure. Exhaustification above K now gives us the speaker-oriented ignorance inferences we were interested in: these ignorance inferences obtain by computing the implicatures associated with the formal alternatives to exh①’s prejacent, which correspond roughly to its independent disjuncts (with and without exh②), all of which are innocently excludable. The resulting outcome, (73c), delivers the pattern of inferences we were after, (72).

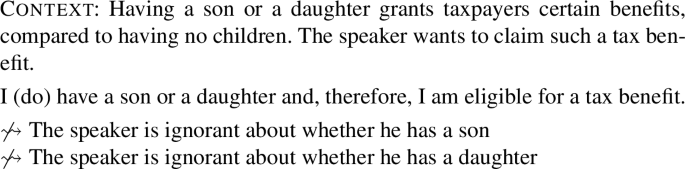

As Marty and Romoli (2021) show, integrating Meyer’s (2013) proposal into M&M’s system predicts the implicatures in (73b) and, consequently, the ignorance inferences following from them to be mandatory in certain contexts. The reason is that, in M&M’s system, the only way an implicature can be avoided is if the alternative it is based on can be pruned from the set of relevant propositions ℛ. Disjunctive sentences are well known to be subject to additional discourse conditions. In particular, it is generally the case that for a disjunction to be felicitous its disjuncts have to be understood as relevant alternatives (Simons 2001; see also Fox 2007; Singh 2008; Fox and Katzir 2011; Marty and Romoli 2021 for discussion). In other words, as a rule of thumb, whenever a disjunction is relevant, so are its disjuncts (i.e., neither of the disjuncts can be pruned from ℛ if the whole disjunction is itself in ℛ).Footnote 30 We adopt this line of explanation to account for the general observation that disjunctions give rise to ignorance inferences in ordinary conversations, and in particular for the observation that examples like those in (45) are infelicitous in run-of-the-mill contexts.

-

(74)

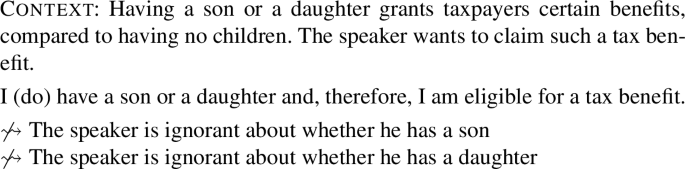

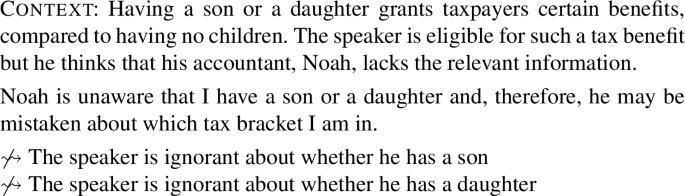

It is worth emphasising, however, that the description above is but a rule of thumb, one that aims at capturing speakers’ interpretive preference (or bias) in run-of-the-mill contexts. As such, this rule of thumb need not be applied in more specific circumstances (see fn.30 for discussion and fn.14 for examples). Specifically, on the present approach, the sentences in (45) are predicted to be acceptable if, instead, the context of utterance makes it so that neither of the independent disjuncts is immediately relevant to the topic of conversation, thus suspending the ignorance implicatures that would otherwise be drawn from them. As shown in (74), this prediction is indeed borne out: a sentence like (45a) becomes felicitous in a context where all it matters to know is whether or not the speaker qualifies for a child tax benefit, and where, therefore, the actual gender of the speaker’s children becomes irrelevant.

-

(74)

We will now see that this line of explanation extends to disjunctive presuppositions, accounting for our novel cases of presupposed speaker’s ignorance.

5.2.2 Presupposed speaker’s ignorance

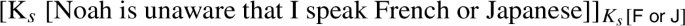

Given some natural assumption about the Matrix K operator, Meyer’s (2013) proposal can be integrated into the M&M system so as to account for the presuppositional variants of (72). In Marty and Romoli (2021), this is done by refining the semantics of K as shown in (75), so as to offer a proper treatment of presuppositions. In a nutshell, (75) states that presuppositions project universally under K.Footnote 31 As Marty and Romoli (2021) note, this refinement simply corresponds to what is predicted by standard accounts of presupposition projection under attitude predicates (see Heim 1992, among others).

-

(75)

With this refinement in place, we turn to show that a similar explanation as that given above for (72) extends to speaker-oriented presupposed ignorance cases like (76):

-