Abstract

One of the distinctive features of Slavic verbs is their aspectual morphology: typically each finite and non-finite form of a verb has a constant aspectual value: either perfective (PFV) or imperfective (IPFV). Nevertheless, in all Slavic languages, besides these prototypical verbs with only one assigned aspectual value, there are also verbs with underspecified aspectual value, usually called biaspectual verbs (BVs).

As argued in the literature, on the sentence level such verbs have the potential to express both aspectual values, PFV and IPFV, without any further aspectual affixation. However, some scholars assert that the intended aspectual value of such verbs can rarely be unambiguously signaled. To resolve the ambiguous aspectual value, native speakers often provide additional context signals or derive a new aspectually defined verb to indicate the intended aspectual value. The latter possibility has been addressed in numerous papers, but mainly with the goal of detecting the (most common) prefixes used in this process.

This study aimed to examine the patterns behind BV prefixation in Croatian. In order to detect factors with a statistically significant impact on prefixation of BVs in Croatian, a random stratified sample of 237 Croatian BVs (BVs of Slavic origin and biaspectual borrowings) was compiled. The data regarding the existence of perfective derivatives were extracted from three different corpora of contemporary Croatian and one subcorpus: the Croatian National Corpus, the Croatian Language Repository, and the Croatian Web Corpus and its subcorpus Forum, and afterwards analyzed using R software with the help of the lme4 package.

The results obtained with the generalized linear mixed model revealed five factors statistically significant for prefixation of BVs in Croatian, which can be attributed to the lexical (semantical), morphological and sociolinguistic domains.

Аннотация

Славянские глаголы отличаются аспектной морфологией: обычно каждая форма глагола во всех славянских языках обладает или совершенным, или несовершенным аспектом. Однако, помимо подобных прототипичных глаголов только с одним аспектом, в языках славянской группы, также существуют глаголы с неопределенным аспектом, так называемые двувидовые глаголы.

Как утверждается в литературе, в предложениях такие глаголы совсем без ограничения могут выражать оба аспекта как совершенный, так и несовершенный даже без аспектной аффиксации, т.е. без формирования аспектной пары. Однако существует альтернативная точка зрения, что на уровне предложения аспект этих глаголов редко может быть однозначен. Чтобы устранить двузначность аспектного значения, носители языка часто пользуются дополнительным контекстом или формируют новые аспектно-однозначные глаголы. Во многих статьях формирование именно новых аспектно-однозначных глаголов рассматривается в основном с целью обнаружения (наиболее распространенных) префиксов, используемых в этом процессе.

Целью данной статьи является изучение закономерностей, связаных с префиксацией двувидовых глаголов в хорватском языке. Для выявления факторов, оказывающих статистически значимое влияние на префиксацию двувидовых глаголов в исследуемом языке, была произведена случайная стратифицированная выборка 237 хорватских двувидовых глаголов (37 двувидовых глаголов славянского происхождения и 200 заимствованных двувидовых глаголов). Данные о существовании производных глаголов совершенного вида были собраны из трёх корпусов современного хорватского языка и одного подкорпуса: Хорватского национального корпуса, Репозитория хорватского языка, а также Хорватского веб-корпуса и его подкорпуса Форум. Собранные данные проанализированы с помощью программы R, т.е. пакета lme4.

Статистический анализ данных при помощи обобщённой линейной смешанной регрессии выявил пять статистически значимых факторов, оказывающих влияние на префиксацию двувидовых глаголов в хорватском языке, которые можно определить как лексические (семантические), морфологические и социолингвистические факторы.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

As well as actionality,Footnote 1 which seems to be a common feature of all languages (cf. Breu, 1980: 115; Lehmann, 1992), Slavic languages additionally have verbal aspect as a grammatical category. The two interact in a rather complicated way.Footnote 2 On the morphological level, a given verb has an inherent PFV or IPFV aspect, obligatorily expressed by all finite and non-finite forms of that verb (cf. Janda, 2007a: 608). For example, based on its actional properties the lexical meaning ‘to voluntarily let someone have something free of charge’ is morphologically coded as PFV, i.e. dati. In contrast, the lexical meaning ‘prepare food on the stove or on the fire in a pot with boiled water’ is, according to its actional properties, coded as IPFV on the morphological level, i.e. kuhati. Nevertheless, in principle every lexical meaning can be expressed with both PFV and IPFV verbs. The examples in (1) illustrate how this is done in Croatian.Footnote 3

-

(1a)

dati

→

davati

give.pfv.inf

give.ipfv.inf

‘to voluntarily let someone have something free of charge’

-

(1b)

kuhati

→

skuhati

cook.ipfv.inf

cook.pfv.inf

‘prepare food on the stove or on the fire in a pot with boiled water’

Prototypically this possibility of expressing the same lexical meaning with verbs whose aspectual values are opposed is provided by aspectual (grammatical) derivation (Lehmann, 2009: 2, 7). Nevertheless, in addition to verbs that have an inherent PFV or IPFV aspect, in all Slavic languages there are verbs with underspecified aspectual value. In simple terms, these verbs lack the morphological distinctions that most verbs have: different forms for PFV and for IPFV aspectual value (cf. Janda, 2007a: 636–637). This may be seen for the Croatian verb analizirati ‘to analyze’, as presented in (2).

-

(2)

analizirati

analyze.(i)pfv.inf

‘to analyze’

In the aspectological tradition these verbs are usually called biaspectual verbs (BVs).Footnote 4 It is assumed that on the sentence level they have the potential to express both aspectual values, PFV and IPFV, without any further aspectual affixation (cf. Stevanović, 1952: 304; Babić, 2002: 554).Footnote 5,Footnote 6 Further to this, scholars (e.g. Isačenko, 1960: 143–144; Avilova, 1968: 66; Galton, 1976: 294; Čertkova, 1996: 100–109; Zaliznjak & Šmelëv, 2000: 10; Silić & Pranjković, 2007: 49) have repeatedly argued that the resolution of (I)PFV aspectual value occurs with the help of context. They have asserted that on the sentence level only one of the two opposing aspectual values is realized. Since the hallmark of BVs is the absence of morphologically distinct PFV and IPFV forms, it is usually other verbs, adverbials, the verbal category of tense, conjunctions, and to some extent the combination of clauses in coordination and subordination that serve as cues for determining the realized aspectual value. To illustrate, in (3) the temporal adverbial satima ‘for hours’ signals that the BV analizirati ‘to analyze’ is being used in the progressive function and has IPFV aspectual value.

-

(3)

To

smo

satima

analizirali…

that

be.1pl

hours

analyze.ipfv.ptcp.pl.m

‘We were analyzing that for hours.’

(hrWaC)

However, some scholars (e.g. Veselý, 2010: 121) argue that the intended aspectual value of such verbs can rarely be signaled unambiguously. In other words, there are many cases in which both aspectual values, PFV or IPFV, can be attributed to a single instance, like in (4).

-

(4)

Kako

ću

ovo

s

guštom

analizirati,

mmmmmm.

how

fut.1sg

this

with

pleasure

analyze.(i)pfv.inf

mhmmmm

‘With what pleasure I will analyze/will be analyzing this.’

(hrWaC)

It is not very easy to determine the intended aspectual value of the BV analizirati ‘to analyze’ in (4), since in Croatian the future tense allows the use of both aspectual values, as do some other tenses. In such a case, given a lack of context or discourse signals, both aspectual values can be attributed to a single instance. Therefore, the instance in (4) can be interpreted as either concrete-factual or progressive, in other words as either PFV or IPFV.

Cases where the intended aspectual value can stay hazy is exactly where things get interesting. Namely, in such a case, native speakers in principle have three possibilities. First, they can ignore the blurred aspectual value and leave the utterances as they are, as illustrated in (4). Secondly, they can give an additional context signal as in (5), where the nominal phrase cijelu situaciju ‘the whole situation’ syntactically indicates perfectivity.Footnote 7,Footnote 8

-

(5)

[...]

krizni

stožer

koji

će

analizirati

crisis

headquarters

which

fut.3sg

analyze.pfv.inf

cijelu

situaciju.

whole

situation

‘[…] crisis headquarters, who will analyze the whole situation.’

(hrWaC)

The third possibility is to form a new, aspectually defined verb with the same meaning, as in (6). In (6) the prefix pro- is a morphological signal of perfectivity.

-

(6)

Sjest

ćemo

i

proanalizirati

situaciju.

sit.pfv.inf

fut.1pl

and

analyze.pfv.inf

situation

‘We will sit down and analyze the situation.’

(hrWaC)

This study aims to examine the third option empirically. Section 2 summarizes the state of the art in biaspectuality research with a focus on aspectual affixation of BVs. Section 3 presents the research questions, while Section 4 explains the data collection process. Section 5 describes the results in detail, and is followed by the final Section 6, which draws conclusions from the main results and offers a suggestion for future research.

2 Biaspectual verbs: state of the art

2.1 The most common topics of biaspectual verbs and their affixation

Biaspectuality is a lexically limited phenomenon. However, besides having a small number of BVs of Slavic origin (mostly inherited from Proto-Slavic), Slavic languages are continuously acquiring BVs via language borrowing. Therefore, given the relative share of such verbs as well as their general semantic, morphological and syntactic properties, biaspectuality certainly plays an important part in the riddle that is Slavic aspect (cf. Mučnik, 1966: 65, 73). However, grammar books and other descriptions of Slavic aspect have devoted relatively little space to the phenomenon (cf. Jászay, 1999: 169).

A review of the rather scarce and scattered information in aspectological literatureFootnote 9 shows that the following issues are addressed in the majority of scholarly works on BVs and biaspectuality in Slavic languages:

-

classification of verbs as biaspectual and discrepancies between different dictionaries,

-

diagnosing biaspectuality (detecting and defining BVs),

-

number of BVs in a given Slavic variety,

-

BV prefixation and suffixation, relative frequencies and functions of the processes and affixes involved, as well as pleonastic and other stylistic characteristics of aspectually marked derivatives formed from base BVs,

-

perseverance of biaspectuality following the emergence of aspectually defined derivatives,

-

differences in degrees to which verbs are biaspectual,

-

biaspectual or aspectless status of such verbs (whether they convey aspectual value at all).

As may be seen, the literature addresses various topics regarding BVs. Nevertheless, the main focus is on aspectual affixation, and more precisely on inventorying the prefixes and suffixes used to derive new (aspectually defined) verbs from BVs.

2.2 Predictions on factors contributing to aspectual affixation of biaspectual verbs

As mentioned in Sect. 1, if a BV is not communicationally transparent with respect to the intended aspectual value, native speakers can draw on aspectual affixation. This allows them to derive an overtly marked PFV or IPFV verb from a base BV to resolve aspectual vagueness (for Russian see Avilova, 1968: 66, for Croatian see Silić & Pranjković, 2007: 49, for Czech see Veselý, 2010: 121; for OCS see Kamphuis, 208–212); for an illustration see the example presented in (6). Nonetheless, it seems that only a limited number of BVs can undergo aspectual affixation. According to the literature (e.g. Mučnik, 1966: 65), less than 1/3 of all BVs in Russian form new overtly aspectually marked derivatives. Moreover, it seems that prefixation is the more common derivation method. Although, as shown in the previous subsection, in works regarding BVs in Slavic the main focus is on aspectual affixation, only some authors touch on the factors that contribute to this process. In a more detailed literature review morphological, semantic and other factors such as the sociolinguistic enter the picture.

Morphological factors that block or foster affixation of BVs appear mainly in literature on Russian aspect. Some scholars (e.g. Mučnik, 1966: 65–66) assume that biaspectual borrowings would fit more easily into the Russian aspectual system if they were formed only with the suffix -ova- (e.g. arendovat’ ‘to rent’, atakovat’ ‘to attack’). In that vein, Avilova (1967: 85; 1968: 69–71) claims that from the end of the 18th century to the 1830s, Russian biaspectual borrowings with the suffix -ova- (e.g. arendovat’ ‘to rent’, raportovat’ ‘to report’) were more prone to prefixation than those containing the suffix -irova- (e.g. bal’zamirovat’ ‘to embalm’, meblirovat’ ‘to furnish’). Building on these lines of thought, one could speculate that in Croatian BVs of Slavic origin and biaspectual borrowings might differ when it comes to prefixation. In Croatian these two types of BVs actually differ strongly in morphological structure. While the majority of biaspectual borrowings have the suffix -ira- (e.g. analizirati ‘to analyze’, fotografirati ‘to photograph/to take photos’), BVs of Slavic origin are built with various suffixes (e.g. vidjeti ‘to see’, savjetovati ‘to counsel’, čestitati ‘to congratulate’, noćiti ‘to spend the night’).

Further, the recent literature on Russian aspect indicates the presence (or lack) of synchronically visible prefixes as a morphological factor in the prefixation of BVs. Namely, Piperski (2018: 117–118) claims that Russian BVs that have a synchronically visible prefix (e.g. ispol’zovat’ ‘to use’) are very unlikely to be prefixed. Similar observations were made by the Croatian linguist Babić (1978: 74; 2002: 537), who claimed that prefixation of prefixed verbs is a very rare phenomenon. In Croatian many BVs have either a diachronically or a synchronically distinguishable prefix (e.g. doručkovati ‘to have breakfast’, objedovati ‘to have lunch’, poštovati ‘to respect’, razumjeti ‘to understand’, savjetovati ‘to counsel’, uzrokovati ‘to cause’). Therefore, there is good reason to accept Piperski’s claims (2018) and assume that in Croatian, prefixation of base BVs that have a synchronically and/or diachronically distinguishable prefix will be less probable than prefixation of BVs with no such prefix.

As already mentioned, scholars working on Russian aspect have recognized that biaspectual borrowings with different suffixes are not equally prone to prefixation. Morphological constraints on aspectual affixation of BVs have also been observed for South Slavic languages. Reportedly, in Croatian and Serbian -ira- BVs (e.g. markirati ‘to mark’, konstatirati ‘to state’) do not undergo suffixation (cf. Magner, 1963: 628). It has been argued that suffixation of BVs with this suffix is blocked because -ira- is actually an imperfectivizing suffix of native verbs (cf. Magner, 1963: 628).Footnote 10 The same problem occurring with the suffixation of -ira- BVs has also been noticed in Slovenian (cf. Plotnikova, 1971: 35). Nevertheless, corpora of contemporary Croatian language suggest that some -ira- BVs (e.g. instalirati ‘to instal’, organizirati ‘to organize’) in Croatian do have suffixed derivatives (e.g. instaliravati, organiziravati). One justifiable way of thinking would be to treat these suffixed derivatives of BVs as morphological signs of the instability of biaspectuality. Accordingly, if these BVs are unstable enough to form suffixed derivatives, there is good reason to assume that they build prefixed derivatives too.

A few scholars (e.g. Avilova, 1968: 66–68; Šeljakin, 1983: 149) recognize the semantics of base BVs as a factor contributing to prefixation of BVs in Russian. Avilova (1968: 67–68) believes that biaspectual lexical bases like arendovat’ ‘to rent’ and atakovat’ ‘to attack’ that are less polysemous, i.e. have fewer meanings, go hand in hand with prefixation.Footnote 11 Apparently, there is a greater probability that such perfective derivatives will not differ in their lexical meaning from their base BVs. Therefore, such perfective derivatives are ideal candidates for what is called “true aspectual pairs” in traditional Slavic aspectology.Footnote 12 In view of this it may be suspected that polysemy also plays an important role in the prefixation of BVs in Croatian.

Although, as far as I am aware, there have been no comprehensive sociolinguistic studies of BVs in any Slavic language, some sociolinguistic factors regarding derivatives of BVs do appear in the literature. It appears that a speaker’s age has a crucial role in the acceptance of derivatives of BVs. Young and middle-aged native speakers of Russian, Serbian and probably Croatian are more likely to accept derivatives that, until recently, have been rejected in the norm (cf. Jászay, 1999: 174; Lazić, 1976: 58). Prefixal derivatives of biaspectual verbs are particularly visible in Russian colloquial uncodified language (Potechina, 2007: 115). In relation to this, it is worth noting that in the middle of the last century the Russian linguist Isačenko (1960: 145) observed that some BVs did not form aspectually marked suffixed derivatives because of the conservative nature of the functional registers in which they were used. Moreover, some Serbian and Croatian linguists (e.g. Car, 1934; Stevanović, 1952; Kovačević, 2011; Hudeček et al., 2011: 54) label derivatives of BVs as pleonasms and exclude them from the norm. Having this in mind, it could be assumed that different corpora of contemporary Croatian could be a good start in looking for differences between registers. More precisely, corpora of standard Croatian might be more conservative and reflect the norm, while web corpora such as hrWaC and its user-generated subcorpus Forum might allow for broader derivation and usage of derivatives of BVs.

3 Research questions (hypotheses)

As already stated in Sect. 1, the aim of this paper is to give an empirical account of BV prefixation in Croatian. Section 2, which reviews previous studies on BVs in Slavic languages, showed that not all BVs can form new aspectually defined derivatives to the same extent. Therefore, the goal of this study is to investigate and determine empirically which factors affect the prefixation of BVs. Based on the summarized theoretical facts and predictions outlined in the previous section, the following 5 research questions were formulated:

- RQ1::

-

Do base BVs of Slavic origin and biaspectual borrowings behave differently with respect to prefixation (cf. Mučnik, 1966: 65–66; Avilova, 1967: 85; Avilova, 1968: 69–71)?

- RQ2::

-

Are base BVs with a synchronically and/or diachronically distinguishable prefix less prone to prefixation than BVs that do not begin with such a prefix (cf. Piperski, 2018: 117–118)?

- RQ3::

-

Are base BVs with attested suffixed derivatives more prone to prefixation than BVs without such derivatives?

- RQ4::

-

Does the number of meanings of a base biaspectual lemma influence its prefixation (cf. Avilova, 1968: 67–68)?

- RQ5::

-

Are prefixed derivatives of base BVs equally present in different corpora of the Croatian language, i.e. corpora reflecting standard and colloquial language use (cf. Isačenko, 1960: 145; Jászay, 1999: 174; Lazić, 1976: 58; Hudeček et al., 2011)?

These research questions were operationalized as the following null-hypotheses:

- H0.1::

-

Base BVs of Slavic origin and biaspectual borrowings do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation.

- H0.2::

-

Base BVs with a synchronically and/or diachronically distinguishable prefix and base BVs without such a prefix do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation.

- H0.3::

-

Base BVs with suffixed derivatives attested in corpora of the Croatian language and base BVs without such derivatives do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation.

- H0.4::

-

Base BVs with different numbers of meanings do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation.

- H0.5::

-

The same base BVs do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation when data from different corpora of the Croatian language are compared.

4 Data extraction and methodology

4.1 Study design and operationalization of variables

For the purpose of this study, a fully crossed factorial design allowing the examination of the relationship between the dependent variable (prefixation of BV) and the five independent variables was developed. The information on the variables, i.e. their class, type, levels and coding, is summarized in Table 1 below, and a concise description of their operationalization follows beneath it.

The study design comprised one dependent and five independent variables, reflecting the research questions presented in the previous section. The dependent variable was the prefixation of the BV, with two levels: 0 (no prefixed derivative attested) and 1 (prefixed derivative attested in corpora of Croatian).

The first independent variable was the origin of the base biaspectual lemma, with two levels: slav (e.g. poštovati ‘to respect’, častiti ‘to invite/to respect’) and irati (e.g. karakterizirati ‘to characterize’, analizirati ‘to analyze’). As may be seen in the examples in brackets, the code slav corresponds to BVs of Slavic origin and the code irati corresponds to biaspectual borrowings with the -ira- suffix.

The second independent variable was the presence of a synchronic and/or diachronic prefix within the base BV, which had two levels: 0 (synchronic and/or diachronic prefix not present in the base BV) and 1 (synchronic and/or diachronic prefix present in the base BV).

The third independent variable was the existence of a suffixed derivative of the base BV, with two levels: 0 (suffixed derivative of the base BV not attested) and 1 (suffixed derivative of the base BV attested in corpora of Croatian). To check if suffixed derivatives of BVs are attested in Croatian, the CNC, RepositoryFootnote 13 and hrWaC were queried and the results obtained from these corpora were merged.

The fourth independent variable was the number of meanings of the base biaspectual lemma. As might be assumed, this variable is the most problematic and definitely the most difficult to operationalize in a sensible way. As will be shown, this measure can never be entirely reliable, no matter how it is operationalized. In this study it was operationalized as a numerical variable in the following way. The number of meanings was extracted from two dictionaries (for more information see Sect. 4.3). Since the number of meanings ascribed to lemmas varied between these dictionaries, first all the meanings in Matasović & Jojić (2002) were copied to an Excel table. Next, they were compared and supplemented with the meanings from Jojić et al. (2015). Finally, each biaspectual lemma was ascribed a number corresponding to the sum of its meanings (1, 2, 3, …). Bear in mind that meaning variants were also counted as separate meanings.Footnote 14 Alternatively, data on the number of meanings could have been extracted from corpora. Although Croatian corpora do not contain semantic annotation, data on the meanings of each lemma could have been extracted indirectly. One option would have been to analyze the meanings of the lemmas used in a vast number of sentences, i.e. different contexts, and to annotate them manually. Moreover, possible automatic alternatives include application of word sense disambiguation, word sense induction or potentially vector semantics.Footnote 15 However, in the case of the latter methods, pulling out information on the number of meanings, i.e. operationalizing the variable in question, would be too time consuming and require a separate study. Therefore, given a lack of guarantee that the application of word sense disambiguation, word sense induction or vector semantics would actually result in significant improvement of the measure, i.e. after cost-benefit analysis, consulting dictionaries seemed the most reasonable option.Footnote 16

The first four independent variables were introduced as between-items factors (as one base BV cannot belong to different types, i.e. it can either have a Slavic origin or be a biaspectual borrowing; likewise it can either have or not have a suffixed derivative, etc.).

Finally, corpus was introduced as the fifth independent variable, with four levels (CNC, Repository, hrWaC and Forum). This variable was introduced as a within-item factor. To establish whether prefixation of BVs varies between different corpora of contemporary Croatian language, it was necessary to allow comparison of prefixation scores of the same item, i.e. BV, in four different corpora of Croatian.

In order to find out which factors affect the prefixation of BVs in Croatian, corpus linguistic methods and data extraction from dictionaries were employed. The following subsections present item selection (the sample of BVs) as well as the data sources in more detail.

4.2 Item selection: sample of biaspectual verbs for the purpose of the study

The list included in the doctoral dissertation Dvovidni glagoli u hrvatskome i slovenskome jeziku (Smailagić, 2011) suggests that there are more than a thousand BVs in Croatian. Nevertheless, Smailagić (2011) does not offer an exact number of BVs in Croatian. Furthermore, the list itself nicely corroborates what aspectological literature has already reported as a general problem: dictionaries provide contradictory information on the (bi)aspectual values of some lemmas (for Russian see Maslov, 1963: 96–97; Čertkova & Čang, 1998: 24–25; Jászay, 1999: 169; Janda, 2007b: 14, for Czech see Kopečný, 1962: 42; Chromý, 2014: 89, for Bulgarian see Ivančev, 1971: 175).

Although the literature reviewed does not provide information about the exact number of BVs in Croatian, it definitely indicates that there are several distinct groups of BVs in terms of morphological configuration and origin:

-

BVs of Slavic origin (e.g. ručati ‘to have lunch’, vidjeti ‘to see’, poštovati ‘to respect’, častiti ‘to invite/to respect’). These BVs constitute a closed class and belong to various conjugation types.

-

Biaspectual borrowings with the -ira- suffix (e.g. karakterizirati ‘to characterize’, garantirati ‘to guarantee’). This open class is by far the largest group of BVs in Croatian.

-

Non-standard variants of biaspectual borrowings with the -isa- or the -ova- suffixes (e.g. karakterisati, ‘to characterize’, garantovati ‘to guarantee’). This is a closed class of BVs. Corresponding standard variants have -ira- suffixes: compare examples in the second and third group. Some examples of these non-standard variants can still be found in corpora of contemporary standard Croatian due to the presence of older texts, primarily those written in the Yugoslav period.

-

Regionally restricted biaspectual borrowings with the -isa- suffix (e.g. kurtalisati se ‘to get rid of’, uvarisati ‘to score’). Unlike BVs from the previous group, this closed class of regionally restricted BVs does not have -ira- counterparts in standard Croatian.

-

Biaspectual borrowings with various suffixes, many of which are regionally restricted or used exclusively in the colloquial register (e.g. apšisati ‘to fade/to lose color’, barketati ‘to prank’, duplati ‘to double’, hasniti ‘to be useful/to earn’, linčovati ‘to lynch’, lobati ‘to lob’). Although also an open class, this group of BVs is considerably smaller than the second group.

Since RQ1 “Do base BVs of Slavic origin and biaspectual borrowings behave differently with respect to prefixation?” was formulated with reference to Mučnik’s (1966: 65–66) and Avilova’s (1967: 85; 1968: 69–71) assumptions that the morphological structure of BVs influences their prefixation, only verbs from the first two groups were considered to be of interest in this study. BVs from the third and fourth group were not taken into consideration due to their generally low appearance rate in corpora of contemporary Croatian and because it would be difficult to find enough representative items, i.e. base BVs, which would be attested in all the corpora used in this study. Biaspectual borrowings from the last group were not taken into consideration since they are, just like BVs of Slavic origin, formed with various suffixes, and because many of them are regionally restricted and a good portion of them are used mainly in the colloquial register.

This study does not aspire to compile a genuine, novel list of all BVs in Croatian with the help of corpus linguistic methods. This would require a separate study. Instead, it is limited to analyzing samples of verbs that have been recognized as biaspectual by previous scholars.Footnote 17 Before any further data collection, two subsamples of BVs were drawn from the list in Smailagić (2011). The first group contained 37 BVs of Slavic origin. The second group contained 200 biaspectual borrowings. Only lemmas labelled as biaspectual in the two largest dictionaries of contemporary Croatian, Jojić et al. (2015) and Matasović & Jojić (2002), were included in the subsamples.Footnote 18

First, BVs of Slavic origin were taken from the list of BVs in Smailagić (2011) to form the first subsample. Next, as stated above, the biaspectuality of these BVs was additionally checked in the two largest dictionaries of contemporary Croatian. This step was employed to eliminate BVs with debatable biaspectual status from the sample. The check led to the elimination of a total of 20 BVs from the list.Footnote 19 However, during the extraction process it turned out that Smailagić’s (2011) list lacks some BVs of Slavic origin, such as daniti ‘to spend the day/to dawn’, noćiti ‘to spend the night’, poštovati ‘to respect’, zavjetovati se ‘to make a vow’. Therefore, the subsample was supplemented with BVs of Slavic origin found in grammar books and other relevant works.Footnote 20 The problem of representativeness was not a particular consideration in the compilation of this subsample. It comprises 37 BVs of Slavic origin whose biaspectual status was consistently recognized in the dictionaries and grammar books reviewed, see Table 5. Although this might give the impression that the subsample is almost identical to the entire population of BVs of this type,Footnote 21 it is still possible that some Croatian BVs of this type have been overlooked. No list of BVs, including those of Slavic origin, can ever be complete or entirely uncontroversial.

The second subsample (200 biaspectual borrowings, see Table 6)Footnote 22 was formed as a stratified random sample,Footnote 23 as described in the following. Biaspectual -ira- verbs were selected from the list contained in Smailagić (2011) proportionately to the number of BVs given under each letter of the alphabet. Before potential candidates were integrated into the subsample, their biaspectuality was additionally checked in the two dictionaries of contemporary Croatian as described above. Further checks were carried out to ensure that there was enough data for all independent variables of interest.Footnote 24 It is nevertheless possible that the data gathered for this study contain some margin of error. However, the large number of BVs and the stratification of the sample should minimize any distortion error that might have been introduced.

4.3 Corpora of contemporary Croatian and other data sources

In the second step, to empirically answer RQ5 “Are prefixed derivatives of base BVs equally present in different corpora of the Croatian language, i.e. corpora reflecting standard and colloquial language use?” data on prefixation (dependent variable) of the 237 biaspectual items mentioned in the previous subsection were extracted from the three corpora and one subcorpus of contemporary Croatian language that were introduced in the study design as independent variables. Moreover, to meet the requirements of RQ3 “Are base BVs with attested suffixed derivatives more prone to prefixation than BVs without such derivatives?” data on the suffixation of 237 BVs from the sample were also extracted from these corpora. Table 2 below gives basic information about the corpora used in this study.

Two publicly available and electronically stored corpora of standard Croatian, the CNC (Tadić, 1998, 2002) and the Repository (Ćavar & Brozović Rončević, 2012; Brozović Rončević et al., 2018), were used as data sources in this study. Although both corpora represent language strongly influenced by normative prescription, in a way each of them represents at best only a part of the Croatian standard language. Even though both of these corpora are well-known for their rigorous selection of texts, which cover written language from various functional domains and genres, they were compiled at different institutions by different experts with (partly) different visions of what Standard Croatian language is and what it should be like. Thus for example in contrast to the CNC, the Repository also contains translated literature by outstanding Croatian translators. Moreover, unlike the CNC, which features texts from the 1990s onwards, the Repository contains texts dating from the second half of the 19th century to the beginning of the 21st century.Footnote 25 In addition to the two corpora of standard language, the hrWaC and its subcorpus Forum (Ljubešić & Klubička, 2014) were used for data collection. While the Forum subcorpus is composed exclusively of user-generated non-edited content (without external proofreading), the hrWaC contains both standard Croatian (proofread language material) and colloquial Croatian (i.e. non-proofread texts).Footnote 26,Footnote 27 All the corpora used have been automatically lemmatized and morphosyntactically annotated.Footnote 28 Moreover, they are available via the NoSketchEngine interface, which allowed relatively fast data collection.

As already mentioned, it was not possible to extract all data from the corpora. The first obstacle faced was the limitation in annotation. To fill the gap that emerged in the data needed, Matasović & Jojić (2002) and Jojić et al. (2015)Footnote 29 were used as additional data sources. These dictionaries were used to double-check the aspectual value of verbs from both samples, origin of the base BVs (RQ1 “Do base BVs of Slavic origin and biaspectual borrowings behave differently with respect to prefixation?”),Footnote 30 existence of synchronic and/or diachronic prefixes within the base BV (RQ2 “Are base BVs with a synchronically and/or diachronically distinguishable prefix less prone to prefixation than BVs that do not begin with such a prefix?”),Footnote 31 and the number of meanings ascribed to the base biaspectual lemmas (RQ4 “Does the number of meanings of a base biaspectual lemma influence its prefixation?”).

5 Results and discussion

The independent variables outlined in Sect. 4.1. should help to shed light on factors that enable or block prefixation of BVs in Croatian. To test whether the prefixation of the 237 analyzed Croatian BVs is influenced by the origin of the base biaspectual lemma, the presence of a synchronic and/or diachronic prefix within the base BV, the existence of a suffixed derivative of the base BV, the number of meanings of the base biaspectual lemma, and corpus, a generalized linear mixed regression model was designed.Footnote 32 The test was conducted in R (R Core Team, 2020) using the lme4 package (Bates et al., 2015). The code for this model in the R statistical software package is:

The empirical study showed that all of the independent variables contribute in a statistically significant way. Table 3 presents the results of the statistical analysis performed.Footnote 33

The results in Table 3 reveal that all five independent variables have a statistically significant influence on prefixation of BVs in Croatian. The most significant factors were the presence of a diachronic and/or synchronic prefix within a base BV (OrigPf) and the corpus (Corpus), followed by the number of meanings of a base biaspectual lemma (Sem). The two factors that were the least statistically significant for prefixation of BVs in Croatian were the origin of the base biaspectual lemma (Type) and the existence of a suffixed derivative of the base BV (Suf).

Table 4 presents the results of a post hoc test, which tested how exactly the individual levels of independent variables influence prefixation.Footnote 34

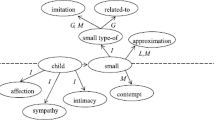

These results are also illustrated in Fig. 1, whose purpose is to enable a better understanding of the discussion.

Some Russian aspectologists (e.g. Mučnik, 1966: 65–66; Avilova, 1967: 85; Avilova, 1968: 69–71) noticed that biaspectual borrowings with certain morphological properties, such as the suffix -ova- (e.g. rekomendovat’ ‘to recommend’, patentovat’ ‘to protect by patent’), are more prone to prefixation. Following these lines of thought this study compared prefixation rates of biaspectual borrowings (with the suffix -ira-) and of BVs of Slavic origin (with various suffixes). As may be seen in Tables 3–4 and in Fig. 1, the origin of the base biaspectual lemma has a statistically significant impact as a factor on prefixation. BVs of Slavic origin (e.g. ručati ‘to have lunch’, savjetovati ‘to counsel’, večerati ‘to dine’, vezati ‘to bind’) are more likely to be prefixed than biaspectual borrowings (e.g. akceptirati ‘to accept’, alarmirati ‘to alarm’, deportirati ‘to deport’, ekranizirati ‘to film’, ekshumirati ‘to exhume’, mumificirati ‘to mummify’, pasterizirati ‘to pasteurize’, sistematizirati ‘to systematize’). In other words, the results obtained with the generalized linear mixed model suggest that the null-hypothesis H0.1 “Base BVs of Slavic origin and biaspectual borrowings do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation” should be rejected. Instead, for the time being an alternative hypothesis should be accepted: Croatian BVs of Slavic origin and biaspectual borrowings differ significantly as to prefixation.

The Russian scholar Piperski (2018: 117–118) raised the question of prefixation of BVs with a synchronically visible prefix (e.g. ispol’zovat’ ‘to use’). He stated that such BVs are very unlikely to be prefixed, but offered no empirical data to support this claim. Building on his ideas, in this study the generalized linear mixed model was applied to test whether in Croatian BVs with and without a synchronically and/or diachronically visible prefix (e.g. doručkovati ‘to have breakfast’, objedovati ‘to have lunch’, savjetovati ‘to counsel’, dezinficirati ‘to disinfect’, reproducirati ‘to reproduce’ vs ručati ‘to have lunch’, večerati ‘to dine’, grupirati ‘to group’, kastrirati ‘to castrate’, marinirati ‘to marinate’) differ significantly as to prefixation. The results of the statistical analysis unambiguously indicate that the null-hypothesis H0.2 “Base BVs with a synchronically and/or diachronically distinguishable prefix and base BVs without such a prefix do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation” should be rejected: see Table 3. Therefore, for the time being the following alternative hypothesis will be accepted: prefixation of BVs that have a distinguishable synchronic and/or diachronic prefix and prefixation of BVs that do not have such a prefix do differ significantly. As the results presented in Tables 3–4 and in Fig. 1 reveal, having a synchronic and/or diachronic prefix has a negative impact on BV prefixation (which is consistent with Babić, 1978: 74; Babić, 2002: 537; Piperski, 2018: 117–118).

Theoretical aspectological literature points out that some BVs are less stable than others. Additionally, there are claims that some BVs have not only prefixed, but also suffixed derivatives. However, the interplay of these processes has never been explicitly empirically linked. Therefore, this study tested whether Croatian BVs for which suffixed derivatives were attested in the corpora of Croatian (e.g. ručati ‘to have lunch’, večerati ‘to dine’, vezati ‘to bind’, instalirati ‘to instal’, organizirati ‘to organize’, parkirati ‘to park’) are more susceptible to prefixation. The results presented in Tables 3–4 and in Fig. 1 strongly suggest that BVs for which suffixed derivatives were attested are more prone to prefixation. In other words, the generalized linear mixed model indicates that the null-hypothesis H0.3 “Base BVs with suffixed derivatives attested in corpora of the Croatian language and base BVs without such derivatives do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation” should be rejected, see Table 3. Instead, for the time being an alternative hypothesis will be accepted: there are significant differences in the prefixation of BVs for which suffixed derivatives were attested in the corpora of Croatian and of BVs for which no such derivatives were attested.

The Russian aspectologist Avilova (1968: 67–68) put forward the hypothesis that prefixation of BVs in Russian is influenced by the polysemy of a base BV. She argued that BVs with fewer meanings (e.g. arendovat’ ‘to rent’, atakovat’ ‘to attack’) should be more prone to prefixation. The results obtained with the generalized linear mixed model and presented in Table 3 demonstrate that the null-hypothesis H0.4 “Base BVs with different numbers of meanings do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation” should be rejected. Moreover, the empirical results obtained for prefixation of Croatian BVs suggest quite the opposite of what Avilova (1968: 67–68) assumed for Russian BVs. That is, prefixation of BVs with more meanings (e.g. častiti ‘to invite/to respect’, vezati ‘to bind’, cementirati ‘to cement’, generirati ‘to generate’, maskirati ‘to mask’) is more prevalent than prefixation of BVs with fewer meanings (e.g. čestitati ‘to congratulate’, opetovati ‘to do something repeatedly’ asfaltirati ‘to asphalt’, lektorirati ‘to proofread’, sistematizirati ‘to systematize’). Therefore, it is clear that the null-hypothesis H0.4 should be rejected. For the time being the following alternative hypothesis will be accepted: base BVs with different numbers of meanings do differ significantly with respect to prefixation. As already discussed in Sect. 4.1 the independent variable of the number of meanings of the base biaspectual lemma was difficult to operationalize in a completely reliable way. Nevertheless, the results obtained revealed a very interesting fact: the more polysemous BVs seem to be more prone to prefixation. One of the logical explanations could be that this is caused by a disambiguation technique. For instance, the BV vezati ‘to bind’ has 11 meanings (cf. Matasović & Jojić, 2002: 1420; Jojić et al., 2015: 1675) and is attested with 24 different (combinations of) prefixes. Some derivatives (e.g. odvezati ‘to untie’, podvezati ‘to tie up/to lift’, razvezati ‘to untie’) are clearly lexical (also known as specialized perfectives in Janda’s 2007a: 609 terms). Others seem to be aspectual pairs (natural perfectives in Janda’s 2007a: 609 terms) for certain meanings. The following lines present several examples of the latter. The biaspectual lemma vezati in its meaning ‘to impose a legal or contractual obligation on’ has the PFV derivative obvezati as its natural perfective. The meaning ‘to fix together and enclose (the pages of a book) in a cover’ of the same biaspectual lemma has the PFV derivative uvezati as its natural perfective. The PFV derivatives zavezati and svezati serve as natural perfectives for the meanings ‘to wrap something tightly’, ‘to restrain someone or something by tying’ and ‘to fasten with a knot’. The PFV derivative povezati (se) is the natural perfective for the meaning ‘to establish a relationship or link with someone based on shared feelings, interests, or experiences’.

Some scholars connect a fair number of sociolinguistic factors to the usage of BVs and their derivatives (e.g. some derivatives are labelled colloquial; prefixed derivatives are more acceptable to younger speakers, etc.). In this respect, in this study it was assumed that the different corpora of Croatian could reflect the importance of some of the (socio)linguistic factors mentioned in the literature. I conjectured that corpora of Croatian that were compiled from texts written in standard Croatian would have fewer prefixed derivatives of BVs than corpora that contain colloquial texts and texts that have not been proofread and corrected in order to meet the norm. As the results obtained with the generalized linear mixed model presented in Tables 3–4 and in Fig. 1 clearly demonstrate, the null-hypothesis H0.5 “The same base BVs do not differ significantly with respect to prefixation when data from different corpora of the Croatian language are compared” should be rejected. Instead, an alternative hypothesis will be accepted for the time being: corpora of Croatian (the texts from which they are compiled) do influence the prefixation of BVs. In other words, prefixation of BVs is more frequent in corpora that contain colloquial and unproofread texts than in corpora that were compiled from texts written in the standard Croatian variety. For instance, while BVs such as specijalizirati ‘to specialize’, rezervirati ‘to make a reservation’, šokirati ‘to shock’, reproducirati ‘to reproduce’, negirati ‘to deny’ and operirati ‘to operate’ have perfective derivatives in the hrWaC and Forum, i.e. corpora that contain colloquial and unproofread texts, their PFV derivatives have not been attested in the Croatian Language Repository and in the Croatian National Corpus, i.e. corpora that were compiled from texts written in the standard Croatian variety. This can be clearly observed in Fig. 1 by comparing prefixation rates in the hrWaC corpus and its subcorpus Forum on the one hand with prefixation rates in the Croatian Language Repository and the Croatian National Corpus on the other.

6 Conclusions and further perspectives

This study addressed five research questions concerning prefixation of BVs in Croatian. In terms of the methodology applied, it is the first such survey of BVs not only in Croatian, but also in Slavic aspectology in general. In total, five factors that affect the prefixation of BVs in Croatian were identified.

As this paper demonstrates, prefixation of BVs is not a random process, but quite the opposite. The empirical study of BVs on the morphological level has confirmed the presence of unquestionable regularities in the process of prefixation. That is, the process is influenced by a range of factors. Some of them can be attributed to the lexical level, such as number of meanings of a biaspectual lemma (RQ4 “Does the number of meanings of a base biaspectual lemma influence its prefixation?”), and some are related to the morphological level, such as presence of a synchronic and/or diachronic prefix within a base BV (RQ2 “Are base BVs with a synchronically and/or diachronically distinguishable prefix less prone to prefixation than BVs that do not begin with such a prefix?”) and the existence of a suffixed derivative of a base BV (RQ3 “Are base BVs with attested suffixed derivatives more prone to prefixation than BVs without such derivatives?”). In this study, the impact of the origin of the base BV on its prefixation was also linked to its morphological structure. The studied sample of 237 Croatian BVs contained 37 BVs of Slavic origin formed with various suffixes and 200 biaspectual borrowings with the suffix -ira- (RQ1 “Do base BVs of Slavic origin and biaspectual borrowings behave differently with respect to prefixation?”). Moreover, as different rates of prefixed derivatives in the four examined corpora of the Croatian language indicate, prefixation of BVs in Croatian is affected by sociolinguistic factors as well (RQ5 “Are prefixed derivatives of base BVs equally present in different corpora of the Croatian language, i.e. corpora reflecting standard and colloquial language use?”).

The post hoc test helped to detect how exactly individual levels of each independent variable influence prefixation of BVs in Croatian. We now know that BVs of Slavic origin are more likely to be prefixed than biaspectual borrowings (RQ1). Further, a synchronic and/or diachronic prefix within a base BV has a negative impact on the prefixation of such verbs (RQ2). In contrast, BVs from which suffixed derivatives have been formed are more likely to be prefixed (RQ3). Lastly, the post hoc test revealed that prefixation of BVs is more frequent in corpora with colloquial texts (RQ5).

Finally, it should be noted that the same factors or a part of them could be relevant for the prefixation of imperfective verbs in Croatian, but this has yet to be proven empirically. It would definitely be interesting to compare whether there is a difference in how the prefixation of BVs and imperfective verbs is affected by the aforementioned factors.

Notes

Actionality, also often referred to as lexical aspect or situation aspect, concerns the inherent semantic properties of a verbal situation that denote the absence or presence of 1) some kind of limit or boundary, 2) duration and 3) dynamic in the lexical structure (cf. Comrie, 1976: 41–51; Filip, 2012: 721). This phenomenon is sometimes also called Aktionsart, which should be avoided since it can be confused with the Russian sposoby glagol’nogo dejstvija.

Many scholars (e.g. Maslov, 1948; Breu, 1985, 1994; Dickey, 2000; Lehmann, 1999, 2009; Sasse, 2002, 2006; Tatevosov, 2002; Filip, 2012; Plungjan, 2016) recognize that aspect and actionality interact. Detailed descriptions of how exactly they interact are the subject of a vast amount of aspectological literature, and lie beyond the scope of this article.

In this article, all verbs will be glossed as PFV for perfective, IPFV for imperfective and (I)PFV for biaspectual regardless of whether the aspectual value is inherent and related to the original actional properties or whether the aspectual value and actional properties have changed as a result of aspectual derivation.

Some aspectologists refer to them as verbs of undetermined aspect (Karcevski, 1927; Mršić, 1999) or aspectually neutral verbs (Grubor, 1953: 162; Kravar, 1980: 10). There are also scholars (e.g. Koschmieder, 1934: 11; Forsyth, 1972; Amse-de Jong, 1974; Bermel, 1997; Mønnesland, 2003; Timberlake, 2004; Lehmann, 2013; Kamphuis, 2020) who treat these verbs as anaspectual or aspectless. Kamphuis (2020: 55) underlines that the terms are not always synonymous and that in some cases different terminology implies different views on aspect, or on the nature of the aspect system in a language. The treatment of such verbs as anaspectual or aspectless is usually down to formal (there are no aspectual correlates) and functional (such verbs are used in sentential functions of both aspects) criteria (cf. Lehmann, 2013: 3). For simplicity and without any theoretical agenda I use the traditional term biaspectual verbs in this article. The question as to whether these verbs are biaspectual, aspectually neutral or aspectless is a separate research question, which I cannot pursue here.

As Slavic verbs are usually assumed to form aspectual pairs, some linguists (for Croatian see Gojmerac, 1980: 67; for Russian see Mučnik, 1966: 61; Maslov, 1984: 69; Zaliznjak & Šmelëv, 1997: 62; Janda, 2011: 17; for Czech see Veselý, 2010: 121) believe that BVs form homonymous aspectual pairs or that they are examples of syncretic aspectual pairs, as in izolirovat’(i)pfv = izolirovat’ipfv – izolirovat’pfv ‘to isolate’. This presupposes so-called zero derivation of aspectual pairs, resulting in two homonymous verbs, one of which is PFV and the other IPFV (Gojmerac, 1980: 67). In contrast to linguists who consider BVs to be homonymous aspectual pairs, Bunčić (2013) uses the conative reading test (was/were V-ing, but not V-ed) to prove that BVs do not form pairs of homonymous verbs with different aspectual values. However, whether BVs form homonymous aspectual pairs or not, it is obvious that in comparison to other verbs they lack a basic morphological distinctive feature, i.e. two distinct forms, one PFV and one IPFV do not exist (cf. Avilova, 1968: 66; Janda, 2007a: 636–637; Janda, 2007b: 89; Kamphuis, 2020: 54–57).

Bear in mind that BVs are not the only verbs in Slavic languages that lack distinct forms in both the PFV and IPFV aspects. There are also so-called perfectiva and imperfectiva tantum verbs, which are coded, based on their actional properties, on the morphological level either as PFV or IPFV. Moreover, these actional properties block the derivation of a verb with the same lexical meaning, but opposing aspectual value. There are two crucial differences between tantum verbs and BVs. First, the actional properties of the latter do not block derivation of verbs with the same lexical meaning but morphologically specified PFV or IPFV aspectual value (or at least not in the same sense as in the case of the former). Secondly, according to current understanding, a BV can be used in both PFV and IPFV aspectual sentential functions, i.e. contexts, whereas a tantum verb can appear only in a PFV or in an IPFV context, like any other PFV or IPFV verb.

In this case the context disambiguates the BV lemma analizirati as PFV. Leaving aside the discussion about whether the context truly makes the verb PFV, I will just comment that I do not see anything wrong with glossing it as PFV, just as I would gloss selima ‘villages’ as either dative, locative or instrumental, relying not only on the morphology (ending) but also (and more importantly) on the syntax.

One of the two anonymous reviewers asked if a minimal pair of the sentence provided in (5) with the PFV verb proanalizirati would reveal a difference in meaning between analizirati and proanalizirati. I consulted other native speakers and they confirmed my assumption that there is no difference in meaning. The lexical meaning is identical. Even if one assumes that in contrast to the telic proanalizirati, analizirati has underspecified telicity like verbs to make, to sing etc., the context clearly makes the verbal situation telic (cf. Comrie, 1976: 44–46). Note, however, that according to the state of the art (e.g. Lehmann, 2009: 31; Janda, 2007b, 2011: 20) BVs are assumed to be telic.

For more detailed information the reader can consult, among others, Car (1934), Stevanović (1952), Brabec et al. (1952), Belić (1955–1956), Maslov (1956, 1963, 1984), Grickat (1957), Horecký (1957), Isačenko (1960), Smiešková (1961), Kopečný (1962), Magner (1963), Ivanova (1964), Kravar (1964, 1980), Mučnik (1966), Avilova (1967, 1968), Forsyth (1970, 1972), Donchenko (1971), Ivančev (1971), Plotnikova (1971), Korošec (1972), Galton (1976), Lazić (1976), Švedova et al. (1980), Gladney (1982), Babić et al. (1991), Čertkova (1996), Čertkova & Čang (1998), Raguž (1997), Jászay (1999), Zaliznjak & Šmelëv (2000), Anderson (2002), Nübler (2002), Timberlake (2004), Janda (2007a, 2007b), Gorobec (2008), Veselý (2010), Berger (2011), Kovačević (2011), Hudeček et al. (2011), Smailagić (2011), Dickey (2012), Bunčić (2013), Lehmann (2013), Chromý (2014), Zinova & Filip (2015), Pavlova (2017), Horiguti (2017), Horiguchi (2018), Piperski (2018), and Kamphuis (2020).

Magner (1963: 28) gives the verb izabrati – izabirati ‘to select/to choose’ as an example. Although the sequence -ira- does appear in the imperfective derivative in question, the perfective base verb is not imperfectivized by the suffix -ira-. Some Croatian authors (e.g. Tafra & Košutar, 2009: 95) believe that in such examples the infix -\(i\)- is present. I, however, follow the analysis proposed by Marković (2012: 61): the example in question contains an ablaut, i.e. an alternation of the base.

Here one of the two anonymous reviewers asks if this could be related to the large aspectual potential of the verb in question, i.e. its ability to be used in both telic and atelic predicates (for more information on aspectual potential see Kamphuis, 2020: 26–30). As Sect. 5 shows, based on empirical data presented in this paper, at least in Croatian, the relation to the number of meanings is opposite to the one suggested by Avilova (1968: 67–68). The question whether the actional properties of the base have any influence on aspectual affixation has been addressed by Kolaković (2018, 2022a, forthcoming, 2022b, forthcoming). The results presented there suggest that actional properties differ significantly between morphologically stable BVs, i.e. those with no attested PFV or IPFV derivatives, and morphologically unstable BVs, i.e. those with attested PFV, IPFV or both PFV and IPFV derivatives.

As in other Slavic languages, there is a very controversial debate on aspectual pairs in Croatian: see Kolaković (2020) for an overview.

Also known as the Riznica Croatian Language Corpus (https://www.clarin.si/noske/all.cgi/corp_info?corpname=riznica&struct_attr_stats=1&subcorpora=1).

Based on her many years of research experience in the field of semantics, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Dušica Filipović Đurđević from the Department of Psychology, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Belgrade (p.c.) recommended counting meaning variants as separate meanings as a better solution for statistical analysis.

For basic information on word sense disambiguation, word sense induction and vector semantics see Jurafsky & Martin (draft).

Stefanowitsch (2020: 96–97) claims with respect to the different meanings of one word that “the most common operationalization strategy found in corpus linguistics is reference to a dictionary or lexical database” although he acknowledges that it is problematic that “[w]e are relying on someone else’s decisions about which uses of a word constitute different senses”. Moreover, he argues that although we have the option of coming up with our own set of senses, working with an established set of meanings proposed by dictionaries has the advantage that it is maximally transparent to other researchers and that we cannot subconsciously make it fit our own preconceptions, thus distorting our results in the direction of our hypothesis (Stefanowitsch, 2020: 97–98).

As one of the anonymous reviewers noted, the identification of BVs is to a certain degree questionable if we rely on other scholars’ criteria and their identification of verbs as biaspectual. This is primarily because very often we do not know the exact criteria applied. Whenever data is collected, a certain amount of trade-off is inevitably involved in the process itself, and this study was typical in that respect. Since due to high time and human costs not all data could be collected from corpora by myself, I chose to consult dictionaries and reference works. Still, efforts have been made to collect data as objectively as possible and information from multiple sources was compared to eliminate at the outset any data for which the consulted sources provide contradictory information.

This criterion was an additional reason for not including biaspectual borrowings with various suffixes (the last BV group) in this study. Because they are regionally or stylistically restricted, many of them are not present in Jojić et al. (2015), which is a dictionary of standard Croatian.

Verbs were excluded from the sample not only when these two dictionaries offered contradictory information on their aspectual values, but also if the verbs were not noted as lemmas in both dictionaries. This was for instance, the case with znamenovati ‘to determine’ and prorokovati ‘to prophesize’, which were present only in Jojić et al. (2015). Furthermore, the auxiliary/copula biti ‘to be’ and the modal moći ‘can’ were also excluded from the list due to their synsemantic status.

Of all the Croatian grammar books and other relevant works, Babić et al. (1991: 670) offer the most exhaustive description and list of BVs.

According to standards in the social sciences, the samples needed to accurately represent a population are: 30% for a small population (under 1 000), 10% for moderately large populations (10 000), and 1% for large populations (over 150 000) (cf. Neuman, 2007: 162; Buchstaller & Khattab, 2013: 82). Although information on the exact number of biaspectual -ira- borrowings in Croatian cannot be found, it is more than reasonable to assume that their number is well below 150 000 and that it probably lies somewhere between 1 000 and 10 000. For comparison, the Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics (p.c. Ivana Brač) has a database of verbs that contains 24 000 verbs in total, of which 2 320 are BVs. Accordingly, the sample of 200 biaspectual borrowings should in terms of size be representative enough for this type of BV in Croatian.

As defined in Buchstaller & Khattab (2013: 78–79).

In this subsection I have shown how much effort was invested in sample construction. Nevertheless, I am aware that even with the greatest efforts to make a sample representative, i.e. to compile a sample that would reflect the characteristics of an entire population, ultimately the sample itself is rarely a perfect replica of the statistical distribution of all the subgroups of a population (cf. Buchstaller & Khattab, 2013: 75).

According to the official description (e.g. Ćavar & Brozović Rončević, 2012: 52), the corpus was compiled from texts from the period of the standardization of Croatian onward. However, some texts from previous centuries, such as Planine by P. Zoranić, or Judita by M. Marulić, may be encountered while querying.

For more extensive argumentation on this matter, see Kolaković et al. (2019: 511–512) and references therein.

There were two reasons for including not only the hrWaC, but also its subcorpus Forum in the study. First, normativist views that prefixed and suffixed derivatives of BVs are mere pleonasms have relatively little influence on how native speakers write their posts on forum.hr. Second, the hrWaC might contain more derivatives not only because of the colloquial texts featured, but also due to its size. From Table 2 above it is clear that the hrWaC is considerably larger than the two mentioned corpora of standard Croatian, while its subcorpus Forum is comparable to the CNC with respect to size.

The estimated accuracy of morphosyntactic annotation for the hrWaC and Riznica is 92.5% (Ljubešić et al., 2016: 4269; Nikola Ljubešić p.c.) and 86.05% for the CNC (Agić et al., 2008: 449–450). In order to avoid any significant data loss, aspectually marked derivatives were searched for as stems of BVs combined with metacharacters that stood for possible affixes on both sides (e.g. .*kopir.* for both PFV and IPFV derivatives of kopirati ‘to copy’).

Veliki rječnik hrvatskoga standardnog jezika (Jojić et al., 2015) is the largest dictionary of contemporary Croatian. Nevertheless, Hrvatski enciklopedijski rječnik (Matasović & Jojić, 2002), aka Hrvatski jezični portal, is the largest dictionary of modern Croatian searchable online, and is continuously being upgraded with new lemmas with the help of the CNC. Both dictionaries contain not only standard Croatian lexemes, but also jargon and dialectal and colloquial expressions. In addition to those two dictionaries, Školski rječnik hrvatskoga jezika (Birtić et al., 2013), the only normative dictionary of contemporary Croatian, now definitely also figures as an important dictionary. However, in comparison to the two above-mentioned dictionaries it has quite a limited number of lemmas. Moreover, many BVs from the sample are not present in it. Therefore, Birtić et al. (2013) was not consistently used as a complementary source of data.

One of the two anonymous reviewers asked whether this should not be clear anyway since all -irati BVs are in the first group, and others are in the second group (Slavic origin). First, caution is required during sampling as suffixes other than -irati do not automatically signal that the BV in question is of Slavic origin: see Sect. 4.2. Second, there are some problematic BVs with a seemingly Slavic root and the -irati suffix such as lažirati ‘to fake/to counterfeit’. However, dictionary entries indicate that the verb in question is a borrowing from French (lâcher) crossed with the Slavic word laž ‘lie’ (cf. Jojić et al., 2015: 654).

Data on the existence of a synchronic and/or diachronic prefix within the base BV was also supplemented by information in Skok (1971−1974) and in p.c. with Tomislava Bošnjak Botica, Lucija Turkalj and Antonietta Ulivieri Moretti.

The dataset is published in Kolaković (2021).

The first column indicates the research question that addresses the analyzed factor, the second column lists the code of the analyzed factor, the third presents χ2 values, the fourth gives information on degrees of freedom, and the fifth shows \(p\)-values. The stars in the sixth column indicate statistically significant factors, and the number of stars specifies the strength of statistical significance: three stars stand for the strongest statistical significance.

The first column refers to the research question that addressed the analyzed factor, the second column lists the analyzed factors in bold, and below each factor the levels that are being compared with respect to prefixation are shown. The third and fourth column contain Estimate (estimation of the growth strength of the curve) and standard error (SE) values respectively, while the fifth column gives the \(p\)-value. Negative values in the Estimate column indicate that the correlation between the first level of a given factor and the prefixation of BVs verbs is negative.

References

Agić, Ž., Dovedan, Z., & Tadić, M. (2008). Improving Part-of-Speech tagging accuracy for Croatian by morphological analysis. Informatica, 32(4), 445–451.

Amse-de Jong, T. H. (1974). The meaning of the finite verb forms in the Old Church Slavonic Codex Suprasliensis: A synchronic study. The Hague: De Gruyter Mouton.

Anderson, C. (2002). Biaspectual verbs in Russian and their implications on the category of aspect. Honor thesis. University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. http://www.academia.edu/292389/Biaspectual_Verbs_In_Russian_and_Their_Implications_on_the_Category_of_Aspect. Accessed 12 March 2020.

Avilova, N. S. (1967). Slova internacional’nogo proischoždenija v russkom literaturnom jazyke novogo vremeni. Moskva: Izdatel’stvo Nauka.

Avilova, N. S. (1968). Dvuvidovye glagoly s zaimstvovannoj osnovoj v sovremennom russkom jazyke. Voprosy jazykoznanija, 5, 66–78.

Babić, S. (1978). Imperfectivization and the types of prefix-derivation. In R. Filipović (Ed.), Contrastive analysis of English and Serbo-Croatian (Vol. 2, pp. 71–100). Zagreb: Institute of Linguistics, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Zagreb.

Babić, S. (2002). Tvorba riječi u hrvatskome književnom jeziku. Zagreb: HAZU/Globus.

Babić, S., Brozović, D., Moguš, M., Pavešić, S., Škarić, I., & Težak, S. (1991). Glasovi i oblici hrvatskoga književnog jezika. Zagreb: HAZU/Globus.

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, 67(1), 1–48.

Belić, A. (1955–1956). O glagolima sa dva vida. Južnoslavenski filolog, 21, 1–13.

Berger, T. (2011). Perfektivierung durch Präfix im Tschechischen, vermeintliche und tatsächliche Besonderheiten. Wiener Slawistischer Almanach, 67, 33–52.

Bermel, N. (1997). Context and the lexicon in the development of Russian aspect. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Birtić, M., Blagus Bartolec, G., Hudeček, L., Jojić, Lj., Kovačević, B., Lewis, K., Matas Ivanković, I., Mihaljević, M., Miloš, I., Ramadanović, E., & Vidović, D. (2013). Školski rječnik hrvatskoga jezika. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Brabec, I., Hraste, M., & Živković, S. (1952). Gramatika hrvatskoga ili srpskoga jezika. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Breu, W. (1980). Semantische Untersuchungen zum Verbalaspekt im Russischen. München: Verlag Otto Sagner.

Breu, W. (1985). Handlungsgrenzen als Grundlage der Verbklassifikation. In W. Lehfeldt (Ed.), Slavistische Linguistik 1984 (pp. 9–34). München: Otto Sagner.

Breu, W. (1994). Interactions between lexical, temporal and aspectual meanings. Studies in Language, 18(1), 23–44.

Brozović Rončević, D., Ćavar, D., Ćavar, M., Stojanov, T., Štrkalj Despot, K., Ljubešić, N., & Erjavec, T. (2018). Croatian language corpus Riznica 0.1. Slovenian language resource repository CLARIN.SI. http://hdl.handle.net/11356/1180.

Buchstaller, I., & Khattab, G. (2013). Population samples. In R. J. Podesva & D. Sharma (Eds.), Research methods in linguistics (pp. 74–95). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bunčić, D. (2013). Biaspektuelle Verben als Polyseme: über Homonymie, Aspektneutralität und die konative Leseart. Welt der Slaven, 58(1), 36–53.

Car, M. (1934). Antologija ružnoga. Naš jezik, 2, 9–12.

Chromý, J. (2014). Impact of tense on the interpretation of bi-aspectual verbs in Czech. Studie z aplikované lingvistiky, 2, 87–97.

Comrie, B. (1976). Aspect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Čertkova, M. J. (1996). Grammatičeskaja kategorija vida v sovremennom russkom jazyke. Moskva: Izdatel’stvo Моskovskogo universiteta.

Čertkova, M. J., & Čang, P. Č. (1998). Ėvoljucija dvuvidovych glagolov v sovremennom russkom jazyke. Russian linguistics, 22, 13–34.

Ćavar, D., & Brozović Rončević, D. (2012). Riznica: The Croatian language corpus. Prace filologiczne, 63, 51–65.

Dickey, S. M. (2000). Parameters of Slavic aspect: A cognitive approach. Stanford: CSLI.

Dickey, S. M. (2012). Orphan prefixes and the grammaticalization of aspect in South Slavic. Jezikoslovlje, 13(1), 71–105.

Donchenko, A. K. (1971). Biaspectual -ovat’ verbs in Russian. University of Minnesota. Ph.D. Michigan: University Microfilms. A XEROX Company.

Filip, H. (2012). Lexical aspect. In R. I. Binnick (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of tense and aspect. (pp. 721–751). New York: Oxford University Press.

Forsyth, J. (1970). A grammar of aspect. Usage and meaning in the Russian verb. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Forsyth, J. (1972). The nature and development of the aspectual opposition in the Russian verb. Slavonic and East European Review, 50(121), 493–506.

Galton, H. (1976). The main functions of Slavic verbal aspect. Skopje: Macedonian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Gladney, F. Y. (1982). Biaspectual verbs and the syntax of aspect in Russian. The Slavic and East European Journal, 26(2), 202–215.

Gojmerac, M. (1980). Glagolski vid u hrvatskom ili srpskom i njemačkom jeziku. Doktorska disertacija. Sveučilište u Zagrebu. Filozofski fakultet.

Gorobec, E. A. (2008). Dvuvidovye glagoly v sovremennom russkom jazyke. Problemy statusa i klassifikacii. Dissertacija na soiskanie učënnoj stepeni kandidata filologičeskih nauk. Kazanʼ: Kazanskij gosudarstvennyj universitet IM. V. I. Ulʼjanova Lenina.

Grickat, I. (1957). O nekim vidskim osobenostima srpskohrvatskoga glagola. Južnoslavenski filolog, 22, 65–128.

Grubor, Đ. (1953). Aspektna značenja II. In Rad JAZU (Vol. 295, pp. 81–284). Zagreb: JAZU.

Horecký, J. (1957). O tvorení slovies predponami. Slovenská reč, 22(3), 141–155.

Horiguchi, D. (2018). Imperfektivacija zaimstvovannych glagolov v russkom jazyke. Russian Linguistics, 42, 345–356.

Horiguti, D. (2017). Metajazykovaja refleksija v zerkale prefiksacii zaimstvovannych glagolov v russkom jazyke. In V. I. Ìŭčankav (Ed.), Stylìstyka: mova, maŭlenne ì tėkst. Zbornìk navukovyh prac. (pp. 306–312). Mìnsk: Adukacyja ì vychavanne.

Hudeček, L., Lewis, K., & Mihaljević, M. (2011). Pleonazmi u hrvatskome standardnom jeziku. Rasprave Instituta za hrvatski jezik i jezikoslovlje, 37(1), 41–72.

Isačenko, A. V. (1960). Grammatičeskij stroj russkogo jazyka v sopostavlenii s slovackim. Čast’ vtoraja: morfologija. Bratislava: Izdatel’stvo Slovackoj akademii nauk.

Ivanova, K. (1964). Kăm văprosa za prefiksacijata na dvuvidovite glagoli ot čužd proizchod v săvremennija bălgarski ezik. In L. Andrejčin, V. Georgijev, K. Mirčev, & S. Stojkov (Eds.), Izvestija na Instituta za bălgarski ezik. (Vol. 11, pp. 245–251). Sofija: Izdatelstvo na Bălgarskata akademija na naukite.

Ivančev, S. (1971). Problemi na aspektualnostta v slavjanskite ezici. Sofia: Izdalestvo na Bălgarskata akademija na naukite.

Janda, L. A. (2007). Aspectual clusters of Russian verbs. Studies in Language, 31(3), 607–648.

Janda, L. A. (2007). What makes Russian bi-aspectual verbs special. In D. Divjak & A. Kochanska (Eds.), Cognitive paths into the Slavic domain. (pp. 83–109). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Janda, L. A. (2011). Completability and Russian aspect. In M. Grygiel & L. A. Janda (Eds.), Slavic linguistics in a cognitive framework. (pp. 13–35) Vienna: Peter Lang.

Jojić, Lj., Nakić, A., Vajs Vinja, N., & Zečević, V. (2015). Veliki rječnik hrvatskoga standardnog jezika. Zagreb: Školska knjiga.

Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. H. (draft). Speech and language processing (3rd edn.). https://web.stanford.edu/~jurafsky/slp3/. Accessed 14 March 2021.

Jászay, L. (1999). Vidovye korreljaty pri dvuvidovych glagolach. Studia Russica, 17, 169–177.

Kamphuis, J. (2020). Verbal aspect in Old Church Slavonic. Leiden: Brill.

Karcevski, S. (1927). Système du verbe russe: essai de linguistique synchronique. Prag: Legiografie.

Kolaković, Z. (2018). Dvoaspektni glagoli – razlike između (p)opisa u priručnicama i stanja u korpusu s posebnim osvrtom na uporabu izvornih govornika. Ph.D Thesis. University of Regensburg/University of Zagreb.

Kolaković, Z. (2020). Par – nepar – aspektni par. Jezikoslovlje, 21(2), 103–147. https://doi.org/10.29162/jez.2020.5.

Kolaković (2021). Factors contributing to prefixation of biaspectual verbs in Croatian Dataset. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4729675.

Kolaković, Z. (2022a, forthcoming). Actionality and affixation of biaspectual verbs in Croatian in the light of formal-functional theory of verbal aspect. Suvremena lingvistika.

Kolaković, Z. (2022b, forthcoming). Glagolski vid i dvoaspektni glagoli u hrvatskome jeziku: formalno-funkcionalni pristup. Zagreb: Institut za hrvatski jezik i jezikoslovlje.

Kolaković, Z., Jurkiewicz-Rohrbacher, E., & Hansen, B. (2019). Clitic climbing, the raising-control dichotomy and diaphasic variation in Croatian. Rasprave: Časopis Instituta za hrvatski jezik i jezikoslovlje, 45(2), 505–522.

Kopečný, F. (1962). Slovesný vid v češtině. Praha: Nakladatelství Československé akademie věd.

Korošec, T. (1972). Nekateri slovenski nedovršni glagoli v dovršni funkciji. Seminar slovenskega jezika, literature in kulture, 8, 202–215.

Koschmieder, E. (1934). Nauka o aspektach czasownika polskiego w zarysie. Próba syntezy. Wilno: Towarzystwo Przyjaciól. Nauk.

Kovačević, M. (2011). Pleonastička upotreba prefiksa u srpskome jeziku. In M. Kovačević (Ed.), Gramatička pitanja srpskoga jezika (pp. 81–101). Beograd: Jasen.

Kravar, M. (1964). Aspektne osobitosti modalnih glagola (Na srpsko-hrvatskom materijalu). Radovi Filozofskog fakulteta u Zadru, 5, 35–49.

Kravar, M. (1980). Neke suvremene dileme oko glagolskoga vida (na građi hrvatskosrpskoga jezika). In R. Radić (Ed.), Jugoslavenski seminar za strane slaviste (Vol. 31, pp. 5–17). Beograd: Štampa Minerva Subotica.

Lazić, M. (1976). Prefixation of borrowed verbs in Serbocroatian. The Slavic and East European Journal, 20(1), 50–59.

Lehmann, V. (1992). Grammatische Zeitkonzepte und ihre Erklärung. Kognitionswissenschaft, 2, 156–170. http://www.subdomain.verb.slav-verb.org/resources/VL.Zeitkonzepte.1992.pdf. Accessed 12 March 2020.

Lehmann, V. (1999). Aspekt. In H. Jachnow & S. Dönninghaus (Eds.), Handbuch der sprachwissenschaftlichen Russistik und ihrer Grenzdisziplinen (pp. 214–242). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

Lehmann, V. (2009). Formal-funktionale Theorie des russischen Aspekts. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1yoJRTeEd2rrP5nQHMTdHPitzEhD8rbe20oeafSJxsKM/edit?pli=1#. Accessed on 12 March 2020.

Lehmann, V. (2013). Aspektlose Verben. https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ibZeINLsoarXqIcCKcj9USiGW7iPlutsVW-QKy-Coss/edit. Accessed 12 March 2020.

Ljubešić, N., & Klubička, F. (2014). {bs,hr,sr}WaC – Web corpora of Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian. In F. Bildhauer & R. Schäfer (Eds.), Proceedings of the 9th Web as Corpus Workshop (WaC-9), Gothenburg (pp. 29–35).

Ljubešić, N., Klubička, F., Agić, Ž., & Jazbec, I.-P. (2016). New inflectional lexicons and training corpora for improved morphosyntactic annotation of Croatian and Serbian. In N. Calzolari, K. Choukri, T. Declerck, S. Goggi, M. Grobelnik, B. Maegaard, J. Mariani, H. Mazo, A. Moreno, J. Odijk, & S. Piperidis (Eds.), Proceedings of the tenth international conference on language resources and evaluation, LREC’ 2016 (pp. 4264–4270). Paris: ELRA.

Magner, T. F. (1963). Aspectual variations in Russian and Serbo-Croatian. Language, 39(4), 621–630.

Marković, I. (2012). Uvod u jezičnu morfologiju. Zagreb: Disput.

Maslov, J. S. (1948). Vid i leksičeskoe značenie glagola v sovremennom russkom literaturnom jazyke. Izvestija Akademii nauk SSSR. Otdelenie literatury i jazyka, 7(4), 303–316.

Maslov, J. S. (1956). Očerk bolgarskoj grammatiki. Moskva: Izdatel’stvo literatury na inostrannych jazykach.

Maslov, J. S. (1963). Morfologija glagol’nogo vida v sovremennom bolgarskom literaturnom jazyke. Moskva: Izdatel’stvo Akademii nauk SSSR.

Maslov, J. S. (1984). Očerki po aspektologii. Leningrad: Izdatel’stvo Leningradskogo universiteta.

Matasović, R., & Jojić, Lj. (2002). Hrvatski enciklopedijski rječnik. Zagreb: Novi Liber.

Mršić, T. (1999). Dubinska dihotomija trenutačno: protežno i glagolski vid. Filologija, 32, 145–155.

Mučnik, I. P. (1966). Razvitie sistemy dvuvidovych glagolov v russkom jazyke. Voprosy jazykoznanija, 1, 61–75.