Abstract

Background

Evangelical Christian college students navigate campus buoyed by Christian privilege but may encounter silencing or othering tied to their religious beliefs, a feeling of incompatibility with their campus climate, and conflations of their religious and political beliefs that are inaccurate and discouraging. Unsupportive campus climates can discourage evangelical students from having productive exchanges across difference and deepening their own worldview commitments, which is concerning due to their general lack of interfaith participation that challenges stereotypes and unnuanced assumptions.

Purpose

This study explores how evangelical Christians perceive their campus climates and whether those perceptions are different based on other social identity intersections with gender, race, sexuality, and political affiliation. In addition to individual characteristics, how the campus environment and various curricular and co-curricular experiences moderate evangelical students’ perceptions of the worldview climate is examined.

Methods

A sample of 1235 evangelical college students was examined via means, standard deviations, and ranges for six campus climate measures, one-way ANOVAs to examine whether those measures differed by different identity dimensions, and then multilevel modeling to better understand the role of campus experiences in evangelicals’ perceptions of their campus climate.

Results

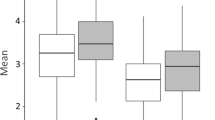

Evangelical students’ campus climate perceptions were generally positive; more provocative encounters were reported by women than men and evangelical Asian students indicated more divisiveness, more insensitivity, and less space for support than their peers. Political affiliation also revealed several significant differences in perceived campus climate. Interfaith engagement through pre-college activities, formal and informal activities, and friendships were connected to perceptions of campus climate, with those reporting more engagement being more likely to have productive encounters across difference and to report insensitivity or divisiveness. Religious affiliation was the most significant institutional characteristic.

Conclusions and Implications

This study illuminates how collegiate experiences and campus environments exacerbate or attenuate evangelical Christian students’ perceptions of the campus climate, and the results indicate that effective teaching practices where true interfaith experiences happen and that create inclusive space for evangelical students in the classroom are key to fostering development, especially in light of the social status ambiguity evangelical college students may be experiencing during their college years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Sample item includes: “In general, people in this group make positive contributions to society”; see Mayhew et al. (2017).

Sample items for each dependent measure include: Divisiveness on campus (“There is a great deal of conflict among people of different religious and nonreligious perspectives on this campus” & “Religious and nonreligious differences create a sense of division on this campus”), Space for support and spiritual expression (“This campus is a safe place for me to express my worldview” & “There is a place on this campus where I can express my personal worldview”), Insensitivity on campus (“While you have been enrolled at your college or university, how often have you been mistreated on campus because of your worldview?” & “On this campus, how often have you heard/read insensitive comments about your worldview from friends or peers?”), Coercion on campus (“While … enrolled at your college or university, how often have you felt pressured by others on campus to change your worldview?; …felt pressured to keep your worldview to yourself?”), Provocative encounters with worldview diversity ( “While … enrolled at your college or university, how often have you had class discussions that challenged you to rethink your assumptions about another worldview?, …heard critical comments from others about your worldview that made you question your worldview”); Negative interworldview engagement (“While … enrolled at your college or university, how often have you felt silenced from sharing your own experiences with prejudice and discrimination?, …had tense [or] somewhat hostile interactions?”). These measures are fully described in Online Resource 2.

This approach allows for testing whether all groups differ significantly from the overall sample mean and additionally enables researchers to retain more information in their analytic models given that parameter estimates for each categorical covariate can be offered in the predictive models (Mayhew and Simonoff, 2015).

The continuum for political leaning is represented by smaller values for very conservative and larger values for very liberal.

Full descriptive results including ANOVA test, and Scheffe Post-Hoc test results are available from the authors by request.

As described earlier, the coefficients and significance tests for effect-coded variables indicate the difference between a particular group and the unweighted average value for that construct. Additionally, because the continuous variables are standardized, the HLM coefficients are analogous to standardized regression coefficients.

Detailed HLM results by block for each outcome are available from the authors by request.

References

Ahmadi, S., and D. Cole. 2015. Engaging religious minority students. In Student engagement in higher education: Theoretical perspectives and practical approaches for diverse populations, ed. S.J. Quaye and S.R. Harper, 171–186. New York, NY: Routledge.

Balmer, R. 2004. Evangelical. Encyclopedia of evangelicalism: Revised and expanded edition. Waco, TX: Baylor University Press.

Beaman, L.G. 2003. The myth of pluralism, diversity, and vigor: The constitutional privilege of Protestantism in the United States and Canada. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 43: 311–325.

Blumenfeld, W.J., G.N. Weber, and S. Rankin. 2016. In our own voice: Campus climate as a mediating factor in the persistence of LGBT students, faculty, and staff in higher education. In Queering classrooms: Personal narratives and educational practices to support LGBTQ youth in schools, ed. P. Chamness Miller and E. Mikulec. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing Inc.

Bowman, N.A., and J.L. Small. 2010. Do college students who identify with a privileged religion experience greater spiritual development? Exploring individual and institutional dynamics. Research in Higher Education 51 (7): 595–614.

Brookfield, S. 2003. Racializing criticality in adult education. Adult Education Quarterly 53 (3): 154–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713603251212.

Bryant, A.N. 2007. A portrait of evangelical Christian students in college. Brooklyn, NY: Social Science Research Council.

Bryant, A.N. 2008. The developmental pathways of evangelical Christian students. Religion and Education 35 (2): 1–26.

Bryant, A.N. 2011. The impact of campus context, college encounters, and religious/spiritual struggle on ecumenical worldview development. Research in Higher Education 52 (5): 441–459.

Bryant Rockenbach, A.N., and M.J. Mayhew. 2013. How the collegiate religious and spiritual climate shapes students’ ecumenical orientation. Research in Higher Education 54: 461–479.

Carter, D.F., and S. Hurtado. 2007. Bridging key research dilemma: Quantitative research using a critical eye. New Directions for Institutional Research 133: 25–35.

Cohen, J., P. Cohen, S.G. West, and L.S. Aiken. 2003. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences, 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cole, D., and S. Ahmadi. 2003. Perspectives and experiences of Muslim women who veil on college campuses. Journal of College Student Development 44 (1): 47–66.

Cole, D., and S. Ahmadi. 2010. Reconsidering campus diversity: An examination of Muslim students’ experiences. The Journal of Higher Education 81 (2): 121–139.

Crandall, R.E., J.T. Snipes, A. Staples, A.N. Rockenbach, M.J. Mayhew, and Associates. 2016. IDEALS narratives: Incoming Evangelical students. Chicago, IL: Interfaith Youth Core.

Cress, C.M., and E.K. Ikeda. 2003. Distress under duress: The relationship between campus climate and depression in Asian American college students. NASPA Journal 40 (2): 74–97.

Dunne, G. 2015. Beyond critical thinking to critical being: Criticality in higher education and life. International Journal of Educational Research 71: 86–99.

Eckel, P., Hill, B., Green, M., and Mallon, B. (1999). Taking charge of change: A primer for colleges and universities. On Change Occasional Paper, No. 3. Washington, DC: American Council on Education.

Edwards, S. 2018. Critical reflections on the interfaith movement: A social justice perspective. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education 11 (2): 164–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000053.

Edwards, S. 2020. Building solidarity with religious minorities: A Reflective practice for aspiring allies, accomplices, and coconspirators. Religion and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/15507394.2020.1815933.

Joshi, K.Y. 2020. White Christian privilege: The illusion of religious equality in America. NYU Press.

Gloria, A.M., and S.E. Robinson Kurpius. 1996. The validation of the cultural congruity scale and the university environment scale with Chicano/a students. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Science 18: 533–550.

Hall, R. M., & Sandler, B. R. (1984). Out of the classroom: A chilly campus climate for women? Washington, D.C.: Project on the Status and Education of Women, Association of American Colleges.

Hammond, P.E., and J.D. Hunter. 1984. On maintaining plausibility: The worldview of evangelical college students. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 23 (3): 221. https://doi.org/10.2307/1386038.

Hurtado S. A., Clayton-Pedersen, A. R., Allen, W. R. Milem, J. F. (1998) Enhancing campus climates for racial/ethnic diversity: Educational policy and practice. The Review of Higher Education 21(3) 279-302 10.1353/rhe.1998.0003

Kendi, I.X. 2016. Stamped from the beginning: The definitive history of racist ideas in America. Hachette, UK.

Lee, J.J. 2002. Changing worlds, changing selves: The experience of the religious self among Catholic collegians. Journal of College Student Development 43 (3): 341–356.

Love, P.G. 1998. Cultural barriers facing lesbian, gay, and bisexual students at a Catholic college. The Journal of Higher Education 69 (3): 298–323.

Lowery, J.W. 2004. Understanding the legal protections and limitations upon religion and spiritual expression on campus. The College Student Affairs Journal 23 (2): 146–157.

Magolda, P. & Ebben Gross, K. (2009). It’s all about Jesus! Faith as an oppositional subculture. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Marsden, G.M. 1994. The soul of the American university: From protestant establishment to established nonbelief. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mayhew, M.J. 2012. A multi-level examination of college and its influence on ecumenical worldview development. Research in Higher Education 53 (3): 282–310.

Mayhew, M.J., and M.E. Engberg. 2010. Diversity and moral reasoning: How negative diverse peer interactions affect the development of moral reasoning in undergraduate students. The Journal of Higher Education 81 (4): 459–488.

Mayhew, M.J., N.A. Bowman, and A.B. Rockenbach. 2014. Silencing whom?: Linking campus climates for religious, spiritual, and worldview diversity to student worldviews. The Journal of Higher Education 85 (2): 219–245.

Mayhew, M.J., and A.N. Bryant Rockenbach. 2013. Achievement or arrest? The influence of the collegiate religious and spiritual climate on students’ worldview commitment. Research in Higher Education 54: 63–84.

Mayhew, M.J., A.N. Rockenbach, N.A. Bowman, M.A. Lo, M. Starke, and T. Riggers-Piehl. 2017. Expanding perspectives on evangelicalism: How non-evangelical students appreciate evangelical Christianity. Review of Religious Research 59 (2): 207–230.

Mayhew, M.J., A.N. Rockenbach, N.A. Bowman, T.A. Seifert, G.C. Wolniak, E.T. Pascarella, and P.T. Terenzini. 2016. How college affects students: 21st century evidence that higher education works, 3rd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mayhew, M.J., A.N. Rockenbach, and L.S. Dahl. 2020. Owning faith: First-year college-going and the development of students’ self-authored worldview commitments. The Journal of Higher Education 91 (6): 977–1002. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2020.1732175.

Mayhew, M.J., and J.S. Simonoff. 2015. Non-white, no more: Effect coding as an alternative to dummy coding with implications for higher education researchers. Journal of College Student Development 56 (2): 170–175. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2015.0019.

Moran, C.D. 2007. The public identity work of evangelical Christian students. Journal of College Student Development 48 (4): 418–434.

Moran, C.D., D.J. Lang, and J. Oliver. 2007. Cultural incongruity and social status ambiguity: The experiences of evangelical Christian student leaders at two midwestern public universities. Journal of College Student Development 48 (1): 23–38.

Nielsen, J.C., and J.L. Small. 2019. Four pillars for supporting religious, secular, and spiritual student identities. Journal of College and Character 20 (2): 180–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/2194587X.2019.1591285.

Park, J.J. 2018. Race on campus: Debunking myths with data. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

Park, J.J., and J.P.M. Dizon. 2017. Race, religion and spirituality for Asian American students. New Directions for Student Services 2017 (160): 39–49.

Peterson, M.W., and M.G. Spencer. 1990. Understanding academic climate and culture. New Directions for Institutional Research 1990 (68): 3–18.

Raudenbush, S.W., and A.S. Bryk. 2002. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods, 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Riggers-Piehl, T.A., and K.J. Lehman. 2016. Modeling the relationship between campus spiritual climate and the sense of belonging for Christian, Muslim, and Jewish students. Religion & Education 43 (3): 247–270.

Rockenbach, A.N., T.D. Hudson, M.J. Mayhew, B.P. Correia-Harker, S. Morin, and Associates. 2019. Friendships matter: The role of peer relationships in interfaith learning and development. Chicago, IL: Interfaith Youth Core.

Rockenbach, A.N., M.J. Mayhew, B.P. Correia-Harker, S. Morin, L. Dahl, and Associates. 2018. Best practices for interfaith learning and development in the first year of college. Chicago, IL: Interfaith Youth Core.

Rockenbach, A. N., M.J. Mayhew, B.P. Correia-Harker, S. Morin, L. Dahl, and Associates. 2017. Navigating pluralism: How students approach religious difference and interfaith engagement in their first year of college. Interfaith Youth Core.

Sanford, N. 1967. Where colleges fail: A study of the student as a person. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Seifert, T.A. 2007. Understanding Christian privilege: Managing the tensions of spiritual plurality. About Campus 12: 10–17.

Shapses-Wertheim, S. 2014. From a privileged perspective: How white undergraduate students make meaning of cross-racial interaction (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). New York, NY: New York University.

Smidt, C. 2007. Evangelical and mainline protestants at the turn of the millennium. In From pews to polling places: Faith and politics in the American religious mosaic, ed. J.M. Wilson, 29–51. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Smidt, C. 2019. Reassesing the concept and measurement of evangelicals: The case for the RELTRAD approach. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58 (4): 833–823.

Smith, K. (2021). Wheaton College faculty condemn 'abuses of Christian symbols' at Capitol siege. Daily Herald (Arlington Heights, IL). https://www.dailyherald.com/news/20210112/wheaton-college-faculty-condemn-abuses-of-christian-symbols-at-capitol-siege.

Speck, B.W. 1997. Respect for religious differences: The case of Muslim students. New Directions for Teaching and Learning 70: 39–46.

Weber, J. (2017). Evangelical vs. Born Again: A survey of what Americans say and believe beyond politics. Christianity Today. Retrieved from https://www.christianitytoday.com.

Acknowledgements

The Interfaith Diversity Experiences and Attitudes Longitudinal Survey (IDEALS) is a national study made possible by funders including The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the Fetzer Institute, and the Julian Grace Foundation. The authors thank the interdisciplinary writing group in the UMKC School of Education for their feedback and support on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Riggers-Piehl, T., Dahl, L.S., Staples, B.A. et al. Being Evangelical is Complicated: How Students’ Identities and Experiences Moderate Their Perceptions of Campus Climate. Rev Relig Res 64, 199–224 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-021-00472-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-021-00472-z