Abstract

Transformational leadership, a type of leadership commonly promoted within higher education, has been shown to positively affect performance, collaborative behavior, and goal accomplishment. Such skills may correlate with the level of job responsibility one has been given and the technical, human, and conceptual skills needed for one to be successful. This study sought to bridge a research gap by exploring correlations between transformational leadership and skills-approach leadership with an exploration of the role of gender within perceptions. An unexpected result based on gender was found: As females achieve higher roles within the Land-Grant University System, the perception of their transformational leadership decreases while that of males increases. Transformational leadership and skills-approach leadership is discussed within the context of gender.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Higher education has always been faced with challenges and opportunities that prompt the field to seek progressive, mission-critical ways to move forward. Worldwide, colleges and universities have faced challenges such as competition for funding and students (Vieira da Motta & Bolan, 2008). Recent global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic and demands for racial equality and inclusion have required higher education to be more flexible and innovative than ever before. Institution closures and re-openings along with heightened reliance on technology for online instruction and communication require faculty and staff to adapt and “[be] ready for anything” (Major, 2020 p. 266). Challenges that existed prior to recent events, such as those related to institutional finances, public scrutiny, and the impact of federal decisions and economic issues, have magnified. In a time when vision, direction, and trust is needed, the case for strong leadership within higher education administration continues to be vital. In fact, “the selection and training of good administrators is widely recognized as one of American industry’s most pressing problems” (Katz, 1955 p. 33). Though this observation was made in 1955, its sentiment still rings true today and for every country.

Leadership is predicted to remain the top human resource challenge through the year 2025 at minimum (Society for Human Resource Management, 2015). Though there are a plethora of individuals working in higher education, administration and leadership challenges exists because there is a dearth of individuals who specifically possess enhanced leadership skills and competencies that twenty-first century educational institutions demand and need. Transformational leadership is a theory and practice known for helping fill the gap between leadership pipeline issues and well-qualified future leaders (e.g. Lamm et al., 2016). It is a well-studied, multi-dimensional theory consisting of attitudes and behaviors that inspire followers to reach improved levels of determination and commitment for the betterment of the whole, leading to overall improved performance (Ayman & Korabik, 2010; Bass & Avolio, 1993). Perceived as a bureaucratic and professional organization (Nica, 2013), higher education may benefit from having more employees emanate this type of leadership (Lamm et al., 2016). However, not all administrative positions have the same span of control nor expectations associated with them. Therefore, a more nuanced approach may be warranted. Specifically, Katz (1955) proposed the skills approach model whereby differing levels of leadership responsibility may require different areas of focus. Leadership development researchers and practitioners have an obligation to continue exploring how skill development should be facilitated and at what stage in an individual’s career the development of certain competencies should be encouraged, which can aid in one’s development of transformational leadership.

Within the higher education leadership literature, the role of gender, and gender experiences has been established (e.g. Dunn et al., 2014), yet, “very little research examines gender differences in [higher education] leadership styles in any systematic way” (Madden, 2011 p.63). Furthermore, there remains a need to more empirically examine higher educator leader perceptions of leadership from a gender-based perspective. For example, Dunn et al. (2014) state “Future research is needed to systematically compare the experiences of female leaders in various types of academic institutions to inform how gender impacts leadership experiences” (p. 17).

The study at hand investigates the perception higher education leaders have of their own transformational leadership capacity and whether that perception is related to other characteristics, specifically gender and/or administrative level held at their respective college or university. Podsakoff et al. (1990) model of transformational leadership is applied to this topic and Katz’s (1955) model of skills-based leadership is used to organize and analyze data to explore new leadership insights.

Conceptual framework

Training leaders through leadership development programming has been found to increase transformational leadership capacity in faculty within the Land-Grant University System (Lamm et al., 2016). The Land-Grant University System is a group of higher education institutions in the United States federally established by law beginning in 1862 to provide education for citizens in each state (Association of Public & Land-Grant Universities, 2016). Congruent with the goals of this study, exploring how transformational leadership aligns with the skills-based approach can aid leadership theory and development efforts for the benefit of current and future leaders in higher education.

Transformational leadership

Podsakoff et al.’s (1990) transformational leadership conceptualization is helpful in identifying leaders who, “transform or change the basic values, beliefs, and attitudes of followers so that they are willing to perform beyond the minimum levels specified by the organization” (p. 108). More specifically, these types of leaders were considered through the lens of the Transformational Leadership Inventory (TLI). This multi-dimensional inventory measures transformational leadership capacity within leadership development program participants (Lamm et al., 2016) through four dimensions of transformational leadership: (1) core transformational leadership behaviors, (2) individualized support, (3) intellectual stimulation, and (4) high performance expectations (Podsakoff et al., 1990).

By acknowledging that each follower is unique (Bass & Riggio, 2006), transformational leaders show respect (Podsakoff et al., 1990) by providing individualized support catered to each individual’s growth and goals (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Bono & Judge, 2004). Intellectual stimulation fosters creativity and new ideas (Bono & Judge, 2004) when followers are encouraged to think outside the box and challenge their own assumptions about how to accomplish work goals (Podsakoff et al., 1990). Additionally, setting high expectations raises the standard of excellence and can generate enthusiasm among followers (Bass & Riggio, 2006; Bono & Judge, 2004; Podsakoff et al., 1990), which helps them exceed beyond what they originally thought could be accomplished.

Skills-based leadership

In his seminal Harvard Business Review (HBR) article, Katz (1955) proposed that effective administration rests on three basic skills which vary in importance depending upon one’s level of administrative responsibility within an organization. Levels of responsibility are categorized as low, middle, and top. Due to the popularity and influence of Katz’s (1955) work, the article was reprinted in 1974 and 1986 (Peterson & Van Fleet, 2004). Katz’s definition of administrator can be akin to that of a leader: “…one who (a) directs the activities of other persons and (b) undertakes the responsibility for achieving certain objectives through these efforts” (Katz, 1955 p. 34). Thus, for the purposes of this study, academic administrators will be referred to synonymously as administrators and leaders. The three foundational skills of an administrator, or leader, are categorized as: technical, human, and conceptual and are recognized as being simultaneously valuable as independent and interdependent, as each complements the others (Katz, 1955).

Technical skills relate to specific, field-related work-tasks and an understanding of the processes and methods underlying such tasks (Katz, 1955). Due to technical skills being necessary for an organized entity, such as a university, to produce the products and services it has been created for (Northouse, 2013), these skills are the most concrete and identifiable; they involve, “specialized knowledge, analytical ability within that specialty, and facility in the use of the tools and techniques of the specific discipline” (Katz, 1955 p. 34).

Human skills are seen as important for employees on all foundational, middle, and top levels of an organization (Katz, 1955; Northouse, 2013) and refer to the ability to communicate and interact with others effectively and cooperatively, which includes resolving conflict and being a contributing member of a team (Peterson & Van Fleet, 2004). Human skill is connected to how an individual interacts with everyone, no matter how the person they are interacting with is categorized in the hierarchical structure.

When an individual reaches an administrative role in an organization that requires competencies beyond technical and human skills, “conceptual skill becomes increasingly more important with the need for policy decisions and broad-scale action.” (Katz, 1955 p. 37). Thus, conceptual skills require one to envision how sub-sets and functions of organizations are interdependent and how the organization or institution as a whole fit within larger environmental contexts such as an industry, a community, and a society (Katz, 1955).

Benefits of Katz’s (1955) theory are the recognition that anyone can be a leader and that taking an inventory of a person’s skills helps with the selection and placement of leaders (Katz, 1955). Northouse (2013) notes the alignment of the skills approach with the majority of leadership education curricula and the usefulness of how it frames what is taught in leadership development programs.

Literature review

Transformational leadership has been promoted for leadership development initiatives specifically oriented toward higher education leaders (e.g. Turnbull & Edwards, 2005). Additionally, a more in-depth look at career development needs for different levels of leadership and gender-specific experiences have also been promoted as necessary avenues of continued research (Dopson et al., 2019; Turnbull & Edwards, 2005).

Transformational leadership

The effectiveness of transformational leadership has been specifically studied in the field of higher education through topics such as diversity management perception (Brown et al., 2019), organizational culture and performance (Hambali & Idris, 2020), workplace engagement and spirituality (Arokiasamy & Tat, 2020), academic research (Hung et al., 2019), and quality management (Argia & Ismail, 2013). Regarding administrative role responsibility in particular, research advises higher education leaders to: establish a vision for their units, departments, and/or institutions; treat those who report to them with fairness and inclusivity; promote shared leadership and collaboration; and steward organizational values (Berson et al., 2016; Gigliotti, 2017; Pearce et al., 2018). Such characteristics relate to Podsakoff et al.’s (1990) description of transformational leadership’s prioritization of innovation and relationships. Higher education literature suggests that there is not only a shift to this type of leadership, but that leadership development efforts should be reconceptualized to include these competencies (Dopson et al., 2019).

Those who demonstrate transformational leadership behavior have been found to be rated as the most effective employees by both subordinates and superiors (Burke & Collins, 2001). Additionally, transformational leadership has been found to transcend different cultures (Carless, 1998) and aid in the transformation of higher education’s academic cultures (Thomas et al., 2015). Transformational leaders benefit organizations by helping with adaption to change (Kearns et al., 2015) and introducing new ideas and improving existing ones (Anthony & Schwartz, 2017). These transformational leaders “communicate powerful narratives about the future,” and “develop a road map before disruption takes hold” (Anthony & Schwartz, 2017 para. 25–29). Research shows that transformational leaders: have and exercise self-awareness; can work independently and across silos; build positive cultures; are willing to collaborate and see situations from different perspectives; build trust and can be trusted; are humble and ask for help when it is needed; make decisions with timeliness and purpose; and challenge, inspire, and empower others (Anthony & Schwartz, 2017; Thompson, 2012). Moreover, “[t]ransformational leaders articulate a vision, use lateral or nontraditional thinking, encourage individual development, give regular feedback, use participative decision-making, and promote a cooperative and trusting work environment” (Carless, 1998 p. 888). It has also been found that employees benefit from such characteristics by experiencing enhanced performance, well-being, and motivation (Fernet et al., 2015; Limsila & Ogunlana, 2008). While both transactional and transformational leadership have been measured in leadership behavior (e.g. Megheirkouni et al., 2018), “leaders who are more satisfying to their followers and who are more effective as leaders are more transformational and less transactional” (Bass, 1999 p. 11). Thus, even in higher education, it is suggested that leadership development efforts should be designed to emphasize transformational, rather than transactional, leadership models (Turnbull & Edwards, 2005).

Connecting transformational leadership and skills-based leadership

Higher education leadership influences every level of a college or university, including the strategic direction of the institution, the culture shared by faculty and staff, and the academic success of students (Nica, 2013). As highlighted in a higher education leadership development program design literature review by Dopson et al. (2019) found “[institutional] leadership is a contextual, processual, relational, social, political and temporal phenomenon” (p. 225). Therefore, it is also suggested that attention is paid to the unique needs leaders experience at different levels of seniority in the higher education hierarchy (Dopson et al., 2019; Turnbull & Edwards, 2005). Furthermore, promotion to a new level based on technical skills rather than human and conceptual skills has been observed in higher education as faculty are sometimes promoted to administrator levels based solely on their teaching or research experience; it is assumed they will be good leaders and will know how to self-correct their leadership methods (Vieira da Motta & Bolan, 2008). Promoting employees that have yet to acquire certain skills can be costly (Benson et al., 2018), with consequences of the leader’s impact possibly not observed until after the transition to the new administrative role (Dopson et al., 2019).

Though the Katz’s (1955) skills-based leadership theory has been used to study specific skills of ground-level leaders in manufacturing companies (Petkevičiūtė & Giedraitis, 2013) and the adequate preparation of on-line learning instructors (Muldrow, 2014), limited empirical efforts have been made to directly connect Katz’s (1955) theory with transformational leadership. Based on Podsakoff et al.’s (1990) description of transformational leadership, the present study conceptually links transformational leadership with the human and conceptual components of skills-based leadership. In the Chronicle of Higher Education, Maimon (2018) highlights this notion by explaining that:

Transformative leadership is more focused on relationships, open to multiple interpretations, adaptable to new situations, and more flexible in adjusting to new environments. The transformative leader is readier to multitask and capable of paying attention both to goals and to the process for achieving them. (para. 3)

Katz (1955) highlights the importance of human and conceptual components on the middle and top management leadership levels. The study at hand answers the call for leadership research within higher education and the Land-Grant University System to focus more on human and conceptual components rather than just technical skills (Lamm et al., 2016).

Leadership and gender

In addition to requiring specific competencies, transformational leaders must understand the value of diversity and how, in “promot[ing] diversity in academic leadership, the college or university should be a microcosm of the total society” (Nica, 2013 p. 192). The relationship between the diversity aspect of gender and leadership has received considerable analysis (e.g. Anim & Shotte, 2020; Bass, 2008). Leadership styles and experiences of women as well as development programs specifically designed for women have been studied in the context of higher education (see Dopson et al., 2019). Additionally, in the U.S. alone, it was observed that in 1972 only 17% of leadership positions were held by women (Bass, 2008) and in 2015 39.2% of such positions were held by women, including 65.7% of education administrators (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). Despite observable shifts of gender representation within the workforce, recent research still indicates persistent differences between genders (Badura et al., 2018). In higher education, women remain underrepresented in leadership roles (Anim & Shotte, 2020; Nica, 2013) despite making up nearly half of all faculty roles and obtaining more than half of the undergraduate degrees earned in the U.S. (Judson et al., 2019). These trends are represented in countries outside the U.S. as well (e.g. Anim & Shotte, 2020). Moreover, though the significance was small, Baker et al. (2019) found that women were less likely to seek department chair roles, positions that are springboards into higher level administrative positions within higher education.

In a recent meta-analysis of predictors and moderators of motivation to lead, the relationship between gender and leadership outcomes was again observed (Badura et al., 2019). The authors suggested, “[p]art of succession planning is being able to identify future leaders so that they can receive additional training and experiences before they are called upon to fill leadership vacancies” (Badura et al., 2019 p. 17). It has been documented that for females in higher education there may exist barriers limiting access to networking, developmental opportunities, and subsequent recruitment for high level administrative positions (Bagilhole & White, 2008). There remains a gap in the literature specifically identifying what characteristics are valued within perceptions of leadership emergence therefore providing an entry into further developmental opportunities (Badura et al., 2018).

Katz’s (1955) skills-based approach has been applied to gender in a number of empirical studies with many using the Style Inventory Survey (Northouse, 2010) to measure technical, human, and conceptual skill. Research findings of such studies found that samples of female leaders in India scored very high on technical and human skill while their male counterparts scored high on conceptual skills (Kaifi & Mujtaba, 2010). A similar study involving Afghan leaders showed opposite results; males had high technical and human skills while females had higher conceptual skills (Mujtaba & Kaifi, 2011). Despite conflicting findings, a mixture of all three skills are needed at each level of administrative responsibility (Katz, 1955; Peterson & Fleet, 2004).

Research objectives

The purpose of this study was to explore relationships between academic leaders’ perceived transformational leadership capacity, corresponding administrative level, and self-reported gender. The study was guided by the following objectives:

-

(1)

Describe the self-perceived transformational leadership capacity of faculty members and administrators participating in a leadership development program for higher education.

-

(2)

Determine whether administrative role categories were statistically significantly related to self-perceived transformational leadership capacity.

-

(3)

Determine whether self-reported gender categories were statistically significantly related to self-perceived transformational leadership capacity.

-

(4)

Determine whether administrative role categories, by gender, were statistically significantly related to self-perceived transformational leadership capacity.

Methods

The following information expounds upon this study’s sample and data analysis process.

Sample

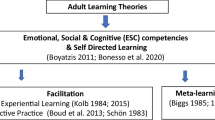

The sample for this study were participants in the LEAD21 leadership development program, which focuses on capacity-building in the areas of communication, conflict management, collaboration, and leading change (LEAD21, n.d.). Participants are associated with the Land-Grant University System and its affiliated organizations such as the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) or Non-Land-Grant Agricultural and Renewable Resources Universities, as well as strategic partners who work alongside institutions to connect academic research with outreach efforts and the needs of the general public (LEAD21, n.d.). Representing various U.S. states and territories, participants were nominated for the program by their institution based on their leadership potential within the Land-Grant University System, with role titles ranging from assistant professor to dean. LEAD21 caters to emerging and top Land-Grant University System administrators and uses adult learning theory to help participants connect program content to their past work experience, which also aligns with what Katz (1955) believed was necessary for effective skill development. The program consisted of three seminars, ranging from four to six days, conducted over the course of nine months. LEAD21 participants also participate in periodic check-in calls and activities between seminars. All data were collected prior to the start of the program to serve as a pre-program baseline value.

The study at hand expounds upon Lamm et al.’s (2016) finding that LEAD21 develops self-assessed transformational leadership capacity within participants by an average of 7%. It further analyzes transformational leadership by answering the call to study multiple classes of LEAD21 participants rather than just one class (Lamm et al., 2016). Four classes of LEAD21 participants were included, creating an overall convenience sample of 340 respondents. The sample consisted of 84 members from the 2015 to 2016 cohort, 85 members from the 2016 to 2017 cohort, 80 members from the 2017 to 2018 cohort, and 91 members from the 2018 to 2019 cohort. Individuals were asked to self-report their gender; 195 individuals identified as male, 143 individuals identified as female, and two individuals did not provide a response.

Data analysis

Respondents were also asked to provide their professional appointment percentages amongst the following categories: academic (teaching), research, Extension (outreach), and administration. For the purposes of this study administrative appointment percentage served as a proxy for Katz’s (1955) role typologies. There were 11 participants that did not respond to the administrative appointment question, therefore these individuals were not included in subsequent analysis. Of the remaining 329 respondents, administrative appointments ranged from 0 to 100% with a mean of 41.4% (SD = 36.2). To establish administrative categories, z-scores were calculated where the score represented the number of standard deviations away from the observed mean score (Lewis-Beck et al., 2003). A negative z-score was associated with the low category (low) (n = 45), a z-score of zero was associated with the middle category (middle) (n = 189), and a positive z-score was associated with the top category (top) (n = 76). Additional details are presented in Table 1.

Transformational leadership scores were calculated using the scoring key related to the TLI, which consists of 14 Likert-type items using a five point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree). The scale had an observed Cronbach Alpha of 0.77 (Podsakoff et al., 1990). Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.

Results

According to the first study objective, overall TLI descriptive statistics were calculated. The observed data resulted in a minimum transformational leadership score of 2.79 and a maximum score of 5.00 (M = 3.78, SD = 0.38). Next, an ANOVA test between cohort groups was conducted, no statistically significant differences were observed when transformational leadership was analyzed by cohort group [F(3, 294) = 1.22, p = 0.30]. As no statistically significant relationships between classes were observed, data were considered to be statistically equivalent for subsequent analysis and considered as a single group to improve analytical power.

Next, to address the second research objective TLI scores were analyzed relative to administrative groupings. The low group had an observed mean score of 3.73 (SD = 0.35), the middle group had an observed mean score of 3.79 (SD = 0.40), and the top group had an observed mean score of 3.78 (SD = 0.33). An ANOVA test between administrative groups was conducted, no statistically significant differences were observed when transformational leadership was analyzed by administrative group [F(2, 288) = 0.55, p = 0.58].

To analyze research objective three, TLI scores were then analyzed based on self-reported gender. Overall females reported a higher self-reported level of transformational leadership (M = 3.82, SD = 0.40) than did men (M = 3.76, SD = 0.37). However, when the observed differences were analyzed using an ANOVA test, no statistically significant differences between groups were observed [F(1, 295) = 1.74, p = 0.19].

For the fourth and final research objective, TLI observations were compared between gender groups at each of the three administrative levels. At the low and middle administrative levels females reported a higher mean TLI score than did men; however, at the top administrative level men reported a higher mean TLI score. Additional details are presented in Table 2. The three pairs of data were further analyzed using an ANOVA test. For the low administrative level, a statistically significant 0.25-point difference between gender mean TLI scores was observed [F(1, 38) = 5.89, p = 0.02]. At the middle administrative level, the 0.06-point difference was not found to be statistically significantly different [F(1, 174) = 0.98, p = 0.32]. Finally, at the top administrative level, the 0.06-point difference was not found to be statistically significantly different [F(1, 72) = 0.54, p = 0.47]. A graphical representation of the data is provided in Fig. 1 to visually represent the trends observed.

Discussion

Gender differences were the main findings among males and females who perceive themselves differently depending on the level of administrative responsibility they have achieved. The study contributes to literature on gender and leadership by showing that progressions of increased or decreased transformational leadership perception may occur as leaders are promoted. Findings not only align with past studies where females rated themselves higher than males on the use of transformational leadership (e.g. Burke & Collins, 2001; Carless, 1998), but the data also expands the discourse by illuminating how perceptions can shift over time based on administrative responsibility and leadership status. The acknowledgement of possible perception changes, based on time passed and position acquired, adds to the process of learning the idiosyncrasies of higher education leadership in general and gendered transformational leadership factors in particular.

Despite the novel nature of the findings, there are a number of limitations which should be acknowledged. First, though personal perceptions and self-reported data can be impactful in guiding researcher understanding of a phenomenon, it is important to note that it does not reflect actual leadership behavior and that responses may potentially be inflated by participants (Burke & Collins, 2001). Therefore, the use and interpretation of the data should be done with care. Specifically, self-reported transformational leadership data were used in the study. A recommendation would be to replicate the present study using a more objective measure of transformational leadership, such as external reviewer (subordinate, peer, supervisor) data. A second limitation is the context in which the study was conducted. As participants in a leadership development program, it is likely the individuals involved are not necessarily representative of all higher education faculty or administrators. The individuals participating in the program were generally identified based on their leadership potential. Therefore, a second recommendation would be replicate the study with a random sample of faculty within higher education more generally. Nevertheless, the current study is intended to provide a foundation upon which future research may benchmark and expand upon present findings.

Although participants of leadership development programs are generally already competent and successful in their respective job functions, leadership educators can help them move from mastering technical skills to developing human and conceptual competencies (Lamm et al., 2016). While the purpose of this study was not to assess whether LEAD21 helped participants develop human and conceptual skills, participants did perceive themselves to have these competencies in some capacity. In addition, participation in the program is based on nomination procedures, indicating that participants’ supervisors believed in the leadership capacity of the participant. Such information indicates that one’s perception of their own capacity to be a transformational leader can shift even if they, and others, initially believe their level of capacity is already high.

Results indicating that a decrease can occur in females’ confidence of their transformational leadership capacity are also interesting given that feminine leadership qualities (e.g. collaboration) have been associated with transformational leadership, leading scholars to posit that, “females and males may differ in their use of certain transformational leadership behaviors” (Carless, 1998 p. 890). A synthesis of research indicates the following female leadership attributes are more closely aligned with transformational leadership: a focus on interpersonal versus task success, empathy (rather than sole evaluation) while helping others, and group dynamics and harmony (as compared to solely reviewing individual performance) (Bass, 2008). Such sentiments referring to effective female leadership attributes have been noted in higher education-specific literature and dialogues (e.g. Nica, 2013). Transformational leadership has been “associated with a pattern of personality including high levels of pragmatism, nurturance, feminine attributes, and self-confidence, and low levels of criticalness and aggressiveness” (Bass, 1999 p. 28).

Previous research indicates women are perceived as more transformational leaders and men are perceived as more transactional leaders; even in women’s transactional leadership style, there is more compassion in situational and corrective circumstances (Bass, 2008). Bass (1999) points out that findings on gender differences could be attributed to the competencies females have to show more of to reach the same levels of leadership as men. For example, the glass ceiling concept, indicating barriers to advancement for females, does not only occur in corporate settings, but in higher education as well (Gunluk-Senesen, 2009). Bagilhole and White (2008) acknowledge that females remain excluded from top leadership positions at colleges and universities due to issues relating to “career mobility, experience outside academia, selection processes, and gender stereotyping” (abstract). This is a global phenomenon and higher education institutions are aware of such barriers, but have yet to fully address systematic structures and organizational cultures that continue this trend (Özkanlı et al., 2009). Although prior research has indicated females may receive more direct leadership development assistance than males (Burke & Collins, 2001), results from this study imply that higher education can do more (e.g. mentoring, promotion of educational associations, gender-specific leadership development initiatives) to provide specific support in helping females maintain their perception of their own transformational leadership effectiveness once they reach top administrative levels at their institution. With awareness and continued study, leadership development efforts can assist with this task. For example, in their review of leadership development literature, Dopson et al. (2019) point to the potential effectiveness of leadership development programming regarding promotion challenges faced by women by noting: “formalised leadership and skill‐based programmes may be more helpful in unblocking…unconscious gendered views rather than experiential methods which do not shift these gendered notions” (p. 223).

Factors such as socialized gender roles, gendered tasks, societal expectations, and challenges females face in leadership and promotion processes (Ayman & Korabik, 2010; Badura et al., 2018; Baker et al., 2019; Bass, 1999; Eagly & Karau, 1991; Judson et al., 2019; Nica, 2013) could possibly affect the decrease in female perceptions of their transformational leadership capacity, but more research should be done to gain a better understanding of the source of change and should include other factors such as organizational aspects. Also in future studies, inviting subordinate and/or superiors to rate their perception of leaders’ behavior could offset the biases and limitations self-reporting can create. Furthermore, the study at hand only looks at relationships between Katz’s (1955) administration levels (low, middle, and high) and the perception of transformational leadership skills; past studies review Katz’s (1955) technical, human, and conceptual skill levels as they relate to gender. Future research is recommended to study the perception of transformational leadership skills against Katz’s (1955) skill categories. Although the literature would indicate the human skill component of Katz’s (1955) theory best aligns with transformational leadership, future research could further examine the relationship combining the three administration levels, the three skills, transformational leadership, and/or gender factors into a single study. Also, due to there being a dearth of studies connecting Katz’s (1955) theory and gender future research may provide additional societal and cultural context (as they relate to gender) to complement the findings in the study at hand, particularly as it relates to leadership and administration within higher education around the globe. Lastly, few studies explore the long-term impact and outcomes of higher education leadership development programs (Dopson et al., 2019). Therefore, specific leadership development factors possibly contributing to any observed changes is a worthwhile response to a call in the literature for more outcome- and longitudinal-based empirical research (Dopson et al., 2019).

Contributions to the literature

The results of the study and subsequent discussion provide an overview of the study and the relationship to the previous research. Nevertheless, from a tactical perspective, the current study provides a series of contributions to the higher education leadership literature. First, the study provides a framework for considering different higher education role types based on administrative appointment.

Second, from an application perspective the preliminary results, before applying the role level and gender variables, are representatives of the risk associated with aggregating groups without appreciating the nuance and unique characteristics associated with different role types and individuals within the roles. Although the transformational leadership results provide a baseline and set of average scores among a sample of higher education leaders, the utility and practical value of the results is somewhat limited. Perhaps the use of better attuned models appears warranted.

Third, the results of the study indicate the role of gender within higher education leadership may not be limited to simply demographic identification. Instead, the results imply the need to consider interaction effects between demographics variables, such as gender, and less proximal role related variables, such as level of leadership role. These contributions specifically address the need for systemic analysis of the role of gender within higher education leadership.

Contributions to practice

The results also contribute to practice and discourse related to higher education leadership. Specifically, the results of the transformational leadership analysis are simultaneously expected and unexpected from a gender and role perspective. From a gender point of view the higher mean scores associated with individuals who self-identified as female is consistent with expectations. Similarly, the increase in mean scores moving from the low administrative group to the middle and top groups is also expected. However, the divergence in observations when overlaying gender and role administrative group is where specific implications for practice may emerge. Specifically, within the low administrative group, self-reported females had statistically significantly higher levels of transformational leadership than their male counterparts.

The results may indicate that initial leadership emergence identification may be associated with individuals fulfilling expected gender roles. However, when transitioning to higher levels of administrative responsibility, the gap between males and females narrows considerably at the middle levels of administrative responsibility as males take on the characteristics of transformational leaders. Concurrently, females appear to adapt their transformational leadership style to match expectations of top-level administrators by modulating aspects of transformational leadership.

Based on these findings, the potential for gender role expectations to influence perceptions of leadership capacity should be noted during the initial stages of leadership identification. Previous researchers have identified that, “women and men who are effective leaders are expected to demonstrate different behaviors and leadership styles” (Dunn et al., 2014, p. 10). Therefore, leadership potential across a range of criteria, both observed and potentially developed, should be considered to ensure individuals are provided opportunities to develop accordingly.

Second, throughout the leadership development process, it is important to acknowledge the role of context and to provide a variety of examples of successful leadership from both males and females, with varying levels of transformational leadership. As previous scholars have found, “The underrepresentation of women in academic administration suggests that masculine practices and leadership norms function to exclude women” (Dunn et al., 2014, p. 9). Finding opportunities and exemplars of success across genders and leadership styles has the potential to inspire more individuals, of both genders, to pursue higher education leadership roles.

Conclusion

The development of leadership skills continues to be one of the most important investments an organization, including higher education, can make in its employees (Badura et al., 2019). Transformational leadership, in particular, has been shown to be an effective and necessary response to meet present and future challenges (Kezar et al., 2019). Therefore, studying the transformational capacity of leaders at varying levels of leadership in higher education domains is a worthwhile venture. The study at hand sought to explore transformational leadership as it relates to administrative roles, possibly being the first to do so and to also connect gender to both topics in the same study. The TLI, an instrument not typically applied to skills-based studies, was used and the use of four LEAD21 leadership development classes gives the study the benefit of comparing multi-year information as well as improved statistical power within which to analyze trends. Also, the study itself provides updated information that can influence the direction of future research surrounding leadership in general and gendered transformational leadership in particular within higher education contexts. Leaders must be educated on how to lead effectively within the sphere of higher education (Dopson et al., 2019; Pearce et al., 2018); findings from this study can be included in such critical development efforts.

Data availability

The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request pending confidentiality requirements associated with Institutional Review Board approval of the research.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Anim, M. N., & Shotte, G. (2020). Leadership roles, women and higher education: Lessons from the University of Buea, Cameroon. Bulgarian Comparative Education Society, 18, 148–155.

Anthony, S. D. & Schwartz, E. I. (2017). What the best transformational leaders do. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved May 8, 2017, from https://hbr.org/2017/05/what-the-best-transformational-leaders-do

Argia, H. A. A., & Ismail, A. (2013). The influence of transformational leadership on the level of TQM implementation in the higher education sector. Higher Education Studies, 3(1), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v3n1p136

Arokiasamy, A. R. A., & Tat, H. H. (2020). Exploring the influence of transformational leadership on work engagement and workplace spirituality of academic employees in the private higher education institutions in Malaysia. Management Science Letters, 10(4), 855–864. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.10.011

Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities. (2016). Land-Grant University FAQ. Retrieved April 22, 2016, from https://www.aplu.org/about-us/history-of-aplu/what-is-a-land-grant-university/#:~:text=A%20land%2Dgrant%20college%20or,1862%2C%201890%2C%20and%201994.&text=The%20first%20Morrill%20Act%20provided,federal%20lands%20to%20each%20state

Ayman, R., & Korabik, K. (2010). Leadership: Why gender and culture matter. American Psychologist, 65(3), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018806

Badura, K. L., Grijalva, E., Galvin, B. M., Owens, B. P., & Joseph, D. L. (2019). Motivation to lead: A meta-analysis and distal-proximal model of motivation and leadership. Journal of Applied Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000439

Badura, K. L., Grijalva, E., Newman, D. A., Yan, T. T., & Jeon, G. (2018). Gender and leadership emergence: A meta-analysis and explanatory model. Personnel Psychology, 71(3), 335–367. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12266

Bagilhole, B., & White, K. (2008). Towards a gendered skills analysis of senior management positions in UK and Australian universities. Tertiary Education Management, 14, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583880701814124

Baker, V. L., Lunsford, L. G., & Pifer, M. J. (2019). Patching up the “leaking leadership pipeline”: Fostering mid-career faculty succession management. Research in Higher Education, 60(6), 823–843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9528-9

Bass, B. M. (1999). Two decades of research and development in transformational leadership. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8(1), 9–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/135943299398410

Bass, B. M. (2008). The Bass handbook of leadership: Theory, research, and managerial applications (4th ed.). Free Press.

Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1993). Transformational leadership: A response to critiques. In M. M. Chemers & R. Ayman (Eds.), Leadership theory and research: Perspectives and directions (pp. 49–80). Academic Press.

Bass, B. M., & Riggio, R. E. (2006). Transformational leadership. Psychology Press.

Benson, A., Li, D., & Shue, K. (2018). Promotions and the peter principle. The National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/papers/w24343

Berson, Y., Waldman, D. A., & Pearce, C. L. (2016). Enhancing our understanding of vision in organizations: Toward an integration of leader and follower processes. Organizational Psychology Review, 6(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386615583736

Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.901

Brown, M., Brown, R. S., & Nandedkar, A. (2019). Transformational leadership theory and exploring the perceptions of diversity management in higher education. Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice, 19(7), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.33423/jhetp.v19i7.2527

Burke, S., & Collins, K. M. (2001). Gender differences in leadership styles and management skills. Women in Management Review, 16(5), 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1108/09649420110395728

Carless, S. A. (1998). Gender differences in transformational leadership: An examination of superior, leader, and subordinate perspectives. Sex Roles, 39(11–12), 887. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018880706172

Dopson, S., Ferlie, E., McGivern, G., Fischer, M. D., Mitra, M., Ledger, J., & Behrens, S. (2019). Leadership development in higher education: A literature review and implications for programme redesign. Higher Education Quarterly, 73(2), 218–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12194

Dunn, D., Gerlach, J. M., & Hyle, A. E. (2014). Gender and leadership: Reflections of women in higher education administration. International Journal of Leadership and Change, 2(1), 2, 9–18. http://digitalcommons.wku.edu/ijlc/vol2/iss1/2

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (1991). Gender and the emergence of leaders: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 685–710. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.5.685

Fernet, C., Trépanier, S.-G., Austin, S., Gagné, M., & Forest, J. (2015). Transformational leadership and optimal functioning at work: On the mediating role of employees’ perceived job characteristics and motivation. Work & Stress, 29(1), 11–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2014.1003998

Gigliotti, R. A. (2017). An exploratory study of academic leadership education within the association of American Universities. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 9(2), 196–210. https://doi.org/10.1108/JARHE-11-2015-0080

Gunluk-Senesen, G. (2009). Glass ceiling in academic administration in Turkey: 1990s versus 2000s. Tertiary Education Management, 15, 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583880903335480

Hambali, M., & Idris, I. (2020). Transformational leadership, organizational culture, quality assurance, and organizational performance: Case study in Islamic higher education institutions (IHEIS). Jurnal Aplikasi Manajemen, 18(3), 572–587. https://doi.org/10.21776/ub.jam.2020.018.03.18

Hung Vu, T., Thu Vu, M., & Hoang, V. N. (2019). The impact of transformational leadership on promoting academic research in higher educational system in Vietnam. Management Science Letters, 10(3), 585–592. https://doi.org/10.5267/j.msl.2019.9.022

Judson, E., Ross, L., & Glassmeyer, K. (2019). How research, teaching, and leadership roles are recommended to male and female engineering faculty differently. Research in Higher Education, 60(7), 1025–1047. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-09542-8

Kaifi, B. A., & Mujtaba, B. G. (2010). A study of management skills with Indian respondents: Comparing their technical, human and conceptual scores based on gender. Journal of Applied Business & Economics, 11(2), 129–138.

Katz, R. L. (1955). Skills of an effective administrator. Harvard Business Review, 33(1), 33–42.

Kearns, K. P., Livingston, J., Scherer, S., & McShane, L. (2015). Leadership skills as construed by nonprofit chief executives. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 36(6), 712–727. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-11-2013-0143

Kezar, A., Dizon, J. P. M., & Scott, D. (2019). Senior leadership teams in higher education: What we know and what we need to know. Innovative Higher Education, 45, 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-09491-9

Lamm, K. W., Sapp, L. R., & Lamm, A. J. (2016). Leadership programming: Exploring a path to faculty engagement in transformational leadership. Journal of Agricultural Education, 57(1), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.5032/jae.2016.01106

LEAD21. (n.d.). Program overview. http://lead21.org/program-overview/

Lewis-Beck, M., Bryman, A. E., & Liao, T. F. (2003). The Sage encyclopedia of social science research methods. Sage Publications.

Limsila, K. & Ogunlana, S. O. (2008). Linking personal competencies with transformational leadership style evidence from the construction industry in Thailand. Journal of Construction in Developing Countries, 13(1), 27–50. http://web.usm.my/jcdc/vol13_1_2008/2_Kedsuda%20Limsila%20(p.%2027-50).pdf

Madden, M. (2011). Gender stereotypes of leaders: Do they influence leadership in higher education? Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies, 9, 55–88.

Maimon, E. P. (2018). A Checklist for Transformative Leaders. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved January 7, 2018, from https://www.chronicle.com/article/A-Checklist-for-Transformative/242167

Major, C. (2020). Innovations in teaching and learning during a time of crisis. Innovative Higher Education, 45(4), 265–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09514-w

Megheirkouni, M., Amaugo, A., & Jallo, S. (2018). Transformational and transactional leadership and skills approach: Insights on stadium management. International Journal of Public Leadership, 14(4), 245–259. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPL-06-2018-0029

Mujtaba, B., & Kaifi, B. (2011). Management skills of Afghan respondents: A comparison of technical, human and conceptual differences based on gender. Journal of International Business and Cultural Studies, 4(1), 1–14.

Muldrow, M. (2014). Online learning and post-secondary expectations: Bridging the gap from academic leaders to instructors. Academic Leadership Journal in Student Research, 2, 1–12.

Nica, E. (2013). The importance of leadership development within higher education. Contemporary Readings in Law & Social Justice, 5(2), 189–194.

Northouse, P. G. (2010). Leadership: Theory and practice (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

Northouse, P. G. (2013). Leadership: Theory and practice (6th ed.). Sage Publications.

Özkanlı, Ö., de Lourdes Machado, M., White, K., O’Connor, P., Riordan, S., & Neale, J. (2009). Gender and management in HEIs: Changing organisational and management structures. Tertiary Education Management, 15, 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583880903073008

Pearce, C. L., Wood, B. G., & Wassenaar, C. L. (2018). The future of leadership in public universities: Is shared leadership the answer? Public Administration Review, 78(4), 640–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12938

Peterson, T., & Van Fleet, D. (2004). The ongoing legacy of R.L. Katz. Management Decision, 42(10), 1297–1308. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740410568980

Petkevičiūtė, N., & Giedraitis, A. (2013). Leadership skills formation in workgroup of the first level managers in manufacturing companies. Management of Organizations: Systematic Research, 67, 69–82. https://doi.org/10.7720/MOSR.1392-1142.2013.67.5

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Moorman, R. H., & Fetter, R. (1990). Transformational leader behaviors and their effects on followers’ trust in leader, satisfaction, and organizational citizenship behaviors. The Leadership Quarterly, 1(2), 107–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/1048-9843(90)90009-7

Society for Human Resource Management. (2015). SHRM research overview: Leadership development. https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/special-reports-and-expert-views/Documents/17-0396%20Research%20Overview%20Leadership%20Development%20FNL.pdf

Thomas, N., Bystydzienski, J., & Desai, A. (2015). Changing institutional culture through peer mentoring of women STEM faculty. Innovative Higher Education, 40, 143–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-014-9300-9

Thompson, J. (2012). Transformational leadership can improve workforce competencies. Nursing Management, 18(10), 21–24.

Turnbull, S., & Edwards, G. (2005). Leadership development for organizational change in a new UK university. Advances in Developing Human Resources, 7(3), 396–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/1523422305277178

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2016). 39 percent of managers in 2015 were women. Retrieved August 1, 2016, from https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2016/39-percent-of-managers-in-2015-were-women.htm

Vieira da Motta, M., & Bolan, V. (2008). Academic and managerial skills of academic deans: A self-assessment perspective. Tertiary Education Management, 14, 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1080/13583880802481740

Funding

This work was supported by the LEAD21 organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

This research is sponsored by the LEAD21 organization in which we have a professional relationship. We have disclosed those interests fully to Springer, and have in place an approved plan for managing any potential conflicts arising from this arrangement.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lamm, K.W., Sapp, L.R., Randall, N.L. et al. Leadership development programming in higher education: an exploration of perceptions of transformational leadership across gender and role types. Tert Educ Manag 27, 297–312 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-021-09076-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-021-09076-2