Abstract

Individuals hold beliefs about what causes poverty, and those beliefs have been theorized to explain policy preferences and ultimately cross-country variations in welfare states. However, there has been little empirical work on the effects of poverty attributions on welfare state attitudes. We seek to fill this gap by making use of Eurobarometer data from 27 European countries in the years 2009, 2010 and 2014 to explore the effects of poverty attributions on judgments about economic inequality as well as preferences regarding the welfare state. Relying on a four-type typology of poverty attribution which includes individual fate, individual blame, social fate and social blame as potential explanations for poverty, our analyses show that these poverty attributions are associated with judgments about inequality and broadly defined support for the welfare state, but have little or no effect on more concrete policy proposals such as unemployment benefits or increase of social welfare at the expense of higher taxes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Why are some people poor? Most of us have opinions on what causes poverty. As a matter of fact, these “lay explanations for poverty” (as the early literature called them, to stress the distinction with experts’ accounts of poverty) are highly variable from one individual to the next. This variation depends on each individual’s personal life experiences, exposure to economic hardship, deeply ingrained values and ideology, exposure to elite and media framing of the poverty issue, and embeddedness in specific political cultures. However, research undertaken since the 1970s (e.g., Feagin, 1972; van Oorschot & Halman, 2000) has established that the various explanations of poverty can be clustered into a small number of “types” structured along a few meaningful dimensions.

Importantly, this literature has postulated that personal explanations for poverty bring to bear on judgments about inequality and on welfare policy preferences (e.g., Bullock, 1999; Kluegel & Smith, 1986; Tagler & Cozzarelli, 2013). It opens up a welcome line of inquiry, which may reinvigorate research on the formation of attitudes toward the welfare state. This research has mainly focused on objective reasons to support the welfare state (such as income and education), and more recently on subjective reasons such as political values, political and social trust, and the perceived deservingness of specific welfare recipient groups (e.g., Arts & Gelissen, 2001; Jaeger, 2008; Kulin & Meuleman, 2015; Roosma et al., 2016; van Oorschot et al., 2017).

Admittedly, explanations for poverty share some predictive capacity with these subjective variables, because they are also related to ideas about social stratification, trust, and deservingness of the poor (see Sect. "Covariates of Poverty Attributions"). However, as conceived in the strand of research inspiring our analysis, explanations for poverty have a unique feature. Namely, these explanations are distinguished according to whether poverty is assumed to have individual or social origins, and according to whether poverty is assumed to result from failure or from fatality—a blame versus fate distinction. Combining these two dimensions yields a four-category typology comprising “individual blame,” “social blame,” “individual fate,” and “social fate” explanations for poverty (see Sect. "A (Not So) New Construct"). In turn, this typology of explanations for poverty is thought to have consequences for the formation of welfare policy preferences (e.g., Bullock et al., 2003; Schneider & Castillo, 2015). To take just one example, research has shown systematic differences between the USA (where a majority of survey respondents explain poverty with individualistic causes) and Europe (where individuals are more likely to see poverty as having social causes), which could explain cross-continental differences in support for (and actual levels of) redistribution (e.g., Alesina et al., 2001; Bénabou & Tirole, 2006). Thus, as mechanisms rooted in both individual- and culture-specific worldviews, poverty attributions provide a complementary perspective to the usual predictors of welfare state support mentioned above (e.g., self-interest, personal experiences of poverty, or values).

In this article, we study the effect of explanations for poverty on welfare attitudes using data from the Eurobarometer series, which to the best of our knowledge is the only international survey to simultaneously include measures for all relevant concepts in several recent waves. For data availability reasons, we focus on the three last surveys in which questions about causes of poverty were asked (2009, 2010, and 2014). Our analyses show that poverty explanations are indeed related to welfare attitudes. As compared to respondents who believe that poverty is due to laziness (individual blame), respondents believing that poverty is related to social injustice (social blame) are on average more concerned about social inequalities, more supportive of state intervention for mitigating unemployment, and more likely to believe that the state (rather than the individual) is responsible for welfare. However, poverty attributions are not directly related to support for the welfare state when guaranteeing social protection is said to be conditional on an increase in individual taxes. This variation between different measurements of welfare state support shows that poverty attributions might shape individuals’ policy preferences but also their willingness to contribute to these policies. Robustness checks show that these findings hold even after controlling for the effects of deservingness judgments, social trust, trust in government, ideology, and personal experiences of poverty.

Theoretical Framework

Welfare Policy Preferences

Preferences regarding social policies have attracted much scholarly attention in the past decades (e.g., Andress & Heien, 2001; Häusermann & Walter, 2010; Kangas, 1997; Kulin & Svallfors, 2013; Rehm, 2009; Roosma et al., 2013; Svallfors, 2003). This interest is related to the fact that these preferences are expected to influence individuals’ electoral choices and thus to be linked with public policy. As a result, citizens’ preferences are perceived as important for understanding cross-country differences or temporal evolution in the shape or size of welfare states in democracies (e.g., Svallfors, 1997, 2003).

Early work on the topic has considered individual self-interest as a main driver for individuals’ preferences with regard to redistribution (Meltzer & Richard, 1981). Following that logic, individuals’ support for redistributive policies largely depends on whether they are net contributors or beneficiaries of the welfare state. However, while self-interest certainly influences individual attitudes, research has also established that current income can only explain a small part of the variation in preferences between individuals. Accordingly, recent studies have begun to incorporate other aspects less directly related to self-interest, such as individuals’ risk profiles (Kananen et al., 2006; Rehm et al., 2012; Rueda, 2005), their expectations about the future (Bénabou & Ok, 2001), their unemployment experiences (Naumann et al., 2016), or “externalities of inequality” (Rueda & Stegmueller, 2016).

Likewise, subjective experiences of poverty, including feelings of relative deprivation (e.g., Kreidl, 2000) and direct exposure to poverty in one’s surroundings (e.g., Hopkins, 2009), have been shown to affect people’s thinking about social inequality and their welfare attitudes. Going one step further, research has stressed the importance of normative orientations which are only dimly related to self-interest—including inequality aversion (e.g., Munro, 2017), personal and political values (e.g., Arikan & Bloom, 2015), ideology (e.g., Jaeger, 2008), or perceptions of the deservingness of the poor (e.g., van Oorschot, 2006).

A (Not So) New Construct: Explanations for Poverty

In comparison with the variables reviewed above, there has been relatively little interest in the effect of explanations for poverty on policy preferences. As we explain in more detail below, this neglect is somewhat surprising. Ever since it was first proposed by Feagin (1972) in the early 1970s, the construct of “lay explanations for poverty” has been obviously related to matters of social inequalities and welfare policy. (The terms “explanations for poverty” and “poverty attributions” convey the same meaning and are used interchangeably in this article.) For one thing, unlike “expert” approaches to socioeconomic inequalities, “lay” poverty attributions are the explanations provided by ordinary people to account for the existence and persistence of poverty in contemporary societies. Although these attributions are certainly reflective of elite debates, media framing and policy changes (e.g., Bullock et al., 2001; Iyengar, 1990; Kangas, 2003; Wacquant, 1999), they also constitute an independent source to understand the ebbs and flows of welfare policy support. Likewise, they may be useful to measure the convergence between attitudes of elites and mass public attitudes. Thus, for example, when some countries took austerity measures including shrinkage of social services in the wake of the 2008 crisis, this was at odds with a surge of the “social blame” attribution of poverty in the years 2009‒2014 (Marquis, 2020), which may help explain the social turmoil arising in this period.

At first sight, poverty can be seen to have a variety of sources. Accordingly, the literature on popular explanations for poverty has come up with various measurements and typologies. One strand of research, following in the footsteps of Feagin’s initial proposal, has elaborated a three-category typology of “individual,” “social,” and “fatalistic” explanations (e.g., Feather, 1974; Smith & Stone, 1989; see also Furnham, 2003; Hunt & Bullock, 2016). The empirical validity of the three-category typology has not remained unquestioned, though. For example, in his analysis of explanations for unemployment in Britain, Furnham (1982) recognized the relevance of two types of fatalistic explanations: one stressing the incompetence of industrial management and one stressing “outside influence” (also including, interestingly, the item “just bad luck”). Van Oorschot and Halman (2000) took notice of Furnham’s (and others’) suggestion and tried to provide a more systematic account of all possible explanations of poverty. They made clear that a fourth type should be added to Feagin’s three-type classification, namely a “social fate type.”

As shown in Table 1, the four categories of the typology correspond to the combination of (1) judgments regarding the location of the explanation for poverty at the individual level or at the social level, and (2) the perception that individuals/society are responsible for poverty (“blame”) or that poverty arises from circumstances and events beyond control of individuals or social institutions (“fate”). Table 1 summarizes the four-type typology, and the way each attribution type is usually operationalized in opinion surveys, including in the Eurobarometer which we use in our analysis. The standard text indicates the label given to each attribution type (see van Oorschot & Halman, 2000) and in italics the response to the following survey question: Why in your opinion are there people who live in poverty? Here are four opinions: which is closest to yours?

Admittedly, the diffusion of the four-category typology in academic research was favored (or directly inspired) by its inclusion in international surveys readily available to scholars (Lepianka et al., 2009: 427). Next to the Eurobarometer series which will be analyzed in this article, the four-type typology also features in the European Values Study (waves 2‒4), in the British Social Attitudes Survey (until 2010), and in the World Values Survey (waves 2‒5). Accordingly, the measurement of poverty attributions pursued in the current study has been validated by its use in many studies yielding similar findings (e.g., Kainu & Niemelä, 2014; Kallio & Niemelä, 2014; Lepianka et al., 2010; Marquis, 2020; Niemelä, 2008).

Still, this measurement approach is essentially data-driven, and it is important to remember that a significant part of research on poverty attributions has gone down different paths. For example, especially after the influential contribution by Kluegel and Smith (1986), American research on poverty attributions has tended to favor a two-type measurement of poverty attribution, based on factor analyses of items suggesting the presence of individualistic and structuralist dimensions (e.g., Hunt, 2002, 2004; Merolla et al., 2011). Although a third, “fatalistic” factor emerged in some of these studies, it was usually discarded because of the dearth or “unpopularity” of items tapping the fatalistic dimension (Hunt, 1996: 318; Hunt, 2016: 394; Hunt & Bullock, 2016) or because both fatalistic and structuralist items loaded on this additional factor (Bullock, 1999; Bullock et al., 2003). Let us note that the two/three-type approach has also been applied in Europe, for example in Germany (Schneider & Castillo, 2015) or in the 11 European countries which participated in the International Social Justice Project (e.g., Kluegel et al., 1995; Kreidl, 2000; Kluegel & Mason, 2004). As a matter of fact, however, most of the surveys using the four-type typology shown in Table 1 center on European countries, which may explain part of the difference between European and American research traditions and empirical results.

Explanations for Poverty and Welfare Policy Preferences

In fact, popular explanations of poverty have often been analyzed as dependent variables to be explained, more rarely as independent variables to explain political attitudes and behaviors. More often than not, the links between poverty attributions, welfare state preferences and voting are taken for granted. Possibly one of the reasons for this lack of interest in the effect of poverty attributions on political preferences is the rather obvious link between the two. Harper (1996) is more critical toward this neglect, pointing out “a startling lack of curiosity about what effects and functions these kinds of explanations [for poverty] might have. (…) In ignoring such difficulties, traditional attributional research on poverty explanations has been essentially conservative in its theory and methodology and has failed to deliver findings which might be of use in acting politically and socially against poverty” (Harper, 1996: 252). Another contentious point which might have restrained scholars from investigating the political consequences of popular explanations for poverty is the issue of causality. In particular, there have been suggestions that poverty attributions are ex-post rationalizations of individuals’ ideological orientation or welfare preferences. For example, Paugam et al. (2017) suggest that affluent people tend to justify poverty on the basis of preexisting neoliberal and meritocratic ideological principles, while other scholars uncritically assume that causality runs from welfare attitudes to poverty attributions (e.g., Niemelä, 2008). In their seminal study, Kluegel and Smith (1986: 267–270) have argued against that viewpoint, emphasizing that sources of poverty attributions lie, for the most part, outside the political realm (see also Iyengar, 1990; Gilens, 1999: 85–89). This argument is buttressed by studies showing that beliefs about poverty are acquired early in life, before political socialization per se occurs (e.g., Bullock, 2006; Chafel, 1997; Chafel & Neitzel, 2005; Leahy, 1990). This does not mean, of course, that poverty attributions are exclusively determined by childhood experiences; as a matter of fact, all available evidence shows that explanations of poverty can change over time according to macro-level and personal circumstances. But the point is that the existence of political preferences is neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition for popular explanations of poverty to develop at the individual level.

How do poverty attributions affect social policy preferences? The relationship may seem obvious but it has seldom been subjected to theoretical analysis. It thus seems necessary to reconcile research traditions which, “despite evident conceptual links,” have tended to develop “parallel agendas” (Schneider & Castillo, 2015: 264). To begin with, the legitimacy of welfare institutions and policies is deeply rooted in well-entrenched social norms such as equity, fairness, solidarity, distributive justice, and reciprocity (e.g., Aalberg, 2003; Deutsch, 1985; Kangas, 2003; Kluegel & Smith, 1986; Mau, 2004; Miller, 1992; Nozick, 1973; Rawls, 1971; Rothstein, 1998). Welfare policies tend to enjoy wide support as long as the actors involved in redistributive mechanisms (i.e., contributors and recipients of welfare policies, but also welfare institutions themselves) are perceived to conform to these social norms (Bowles & Gintis, 2000; Fong et al., 2005). In contrast, when these norms are obviously violated, a breakdown of the pro-welfare consensus is likely to ensue. With respect to anti-poverty programs, “people are willing to help the poor, but they withdraw support when they perceive that the poor cheat or fail to cooperate by not trying hard enough to be self-sufficient and morally upstanding” (Fong et al., 2005: 279). This withdrawal of support closely corresponds to the endorsement of the “individual blame” category in the poverty attribution typology presented above. When the poor are deemed responsible for their own fate, feelings of reciprocity and “moral obligations” to the poor seem to dissolve, thus undermining the legitimacy of welfare policies (Kangas, 2003).

In this article, we subscribe to the common argument that this blame mechanism extends to other sectors of state intervention. As Kluegel and Smith (1986: 164) put it, “antiwelfare sentiment seems to be linked to a ‘victim-blaming’ view of the poor as lazy, lacking thrift and good morals, etc.: the items representing individual explanations for poverty.” As a matter of fact, several studies have empirically explored the link between poverty attributions and a wide array of welfare policy preferences (Alston & Dean, 1972; Bullock, 1999; Burgoyne et al., 1999; Bradley & Cole, 2002; Bullock et al., 2003; Bullock, 2004; Feagin, 1972; Fong, 2001; Hasenfeld & Rafferty, 1989; Habibov et al., 2017; Iyengar, 1990; Kluegel & Smith, 1986; Mau, 2003; Stephenson, 2000; Tagler & Cozzarelli, 2013; Williamson, 1974; Zucker & Weiner, 1993). Virtually all of these studies have established significant relationships between poverty attributions and welfare preferences. Interestingly, poverty attributions were also found to affect the degree to which economic inequalities are perceived as just or unjust (Schneider & Castillo, 2015). In sum, poverty attributions seem to have a pervasive influence on how people conceive the legitimacy of the social stratification at large and, in turn, on their welfare attitudes.

For our present purposes, it is unfortunate that this strand of research has mostly focused on the distinction between individual attributions (above all “laziness”) and structural attributions. With few exceptions, it has failed to take into account the agency dimension—are individuals or social institutions to blame for poverty, or is the problem beyond control of individuals and institutions? Thus, to take the perspective of Table 1, the “blame” and “fate” rows have been conflated within the “individual” and “structural” columns of the typology. Hence, we need to develop more definite expectations about the influence of the four attributional types. Following the general argument formulated above, people endorsing the “individual blame” and “social blame” categories should be the least and the most likely to support redistributive policies, respectively. The two fatalistic categories are expected to fall in between (for a similar analysis, see Halman & van Oorschot, 1999: 4–5; van Oorschot & Halman, 2000: 21–23; Da Costa & Dias, 2014: 1410). First, “individual fate” attributions (e.g., bad luck) should elicit willingness to help the poor (e.g., public relief services) and thus should foster some support for redistribution. However, since poverty is seen as stemming from fatality rather than from structural inequalities, there should be no real impetus for supporting “preventive” policies designed to fight the causes of poverty (unemployment, low education, insufficient pensions, etc.), which should be more popular among people endorsing a “social blame” attribution of poverty. Second, “social fate” attributions ascribe poverty to a normal state of affairs—poverty is determined by impersonal and uncontrollable social forces, so the “modern world” argument goes. According to the social fate attribution type, poverty is here to stay because it is a natural consequence of the capitalist system. However, social policies may be seen as a necessary tool to maintain the system in the long run. By dealing with social inequalities and by meeting demands for social protection, social policies can be seen to fulfill a social control function designed to keep disadvantaged groups quiescent and to prevent social unrest (Armour & Coughlin, 1985; Brisman, 2012; Kim, 2007; Piven & Cloward, 1971; Schneider & Ingraham, 1984; Soss et al., 2011; but see Dodenhoff, 1998). Of course, we do not assume that all people attributing poverty to “social fate” are keen supporters of the capitalist system. In this regard, a detailed analysis of the four-category typology, where 16 specific causes of poverty are related to the four general attributions, indicates that the social fate type is the most heterogeneous and the most uneasy to interpret (Lepianka et al., 2009). This “all-embracing character of the modern world category” (2009: 430) seems to result from the blending of constitutive elements of the “individual fate” and “social blame” categories; in contrast, the key element of the “individual blame” category (i.e., laziness) is rarely mentioned by those who choose the social fate type. Overall, then, people who attribute poverty to social fate are expected to display more support for welfare policies than people blaming poverty on the poor themselves, but less support than people endorsing a “social blame” explanation.

Covariates of Poverty Attributions

By covariates, we mean variables which are supposedly related to explanations of poverty, our main independent variables, and which might also be important for the formation of welfare attitudes, our dependent variables. Accordingly, the influence of poverty attributions on welfare preferences may be confounded with the influence of these covariates, and we will try to disentangle the effects of independent variables and covariates in a series of robustness checks (see Appendix). In the following discussion, we identify four covariates of poverty attributions: (1) deservingness judgments; (2) political and social trust; (3) political ideology; and (4) personal experience of poverty.

First, the perceived deservingness of actual or potential welfare state beneficiaries has been identified as an important antecedent of welfare policy preferences (e.g., Delton et al., 2018; Feather, 1994, 1999; Hansen, 2019; Koster, 2018; Larsen, 2006: chap. 4; Mau, 2003; Raven, 2012; Roosma et al., 2016; Slothuus, 2007; van Oorschot, 2000, 2006, 2008; Van Oorshot & Meuleman, 2014; van Oorschot et al., 2017). In a nutshell, empirical research shows that the support for various social policies is conditional on the degree to which different groups are considered “really worthy” of social protection. While certain groups like the elderly, disabled people, or children from needy families are widely recognized as legitimate beneficiaries of welfare assistance, other groups like unemployed people and immigrants typically enjoy much less support (Jensen & Petersen, 2017; Larsen, 2006; Petersen, 2012; Petersen et al., 2010; Sirovátka et al., 2002; van Oorschot, 2006). It can be argued that poverty attributions have a direct conceptual link with deservingness through the “individual blame” response option. The depiction of the poor as “lazy” or “lacking willpower” implies that they could change their situation and that, therefore, they are potentially undeserving or illegitimate recipients of welfare benefits. In contrast, if society is mainly responsible for poverty or if the poor owe their condition to “bad luck”, it does not follow that welfare recipients are undeserving—even though they might be judged undeserving for other, independent, reasons. Accordingly, there is strong evidence that poverty attributions and deservingness judgments are empirically related, though the nature of the relationship is unclear (e.g., Aarøe & Petersen, 2014; Appelbaum, 2001; Gilens, 1999; Hansen, 2019; Jensen & Petersen, 2017; Petersen, 2012; Skitka & Tetlock, 1993; Sniderman et al., 1991).

In sum, although deservingness judgments and poverty attributions seem to have similar consequences for welfare policy preferences, we argue that they are not one and the same thing. As a more general concept, poverty attributions enable us to make broader predictions regarding policy preferences. At the same time, unlike deservingness judgments, they do not allow to focus on specific disadvantaged groups. Thus, our approach will be to model the effects of both poverty attributions and deservingness judgments on welfare policy preferences, and to estimate the residual effect of poverty attributions controlling for stereotypical and affective reactions toward specific welfare recipient groups.

A second possible covariate of poverty attributions which may have a confounding effect on welfare policy preferences is trust. As argued above, support for redistributive policies hinges on trust relationships between taxpayers and welfare recipients, but it may also depend on how much these two groups trust welfare institutions themselves. On the one hand, at least some of the individuals who hold society responsible for poverty may not rely on society for solving it either, and hence they may not be particularly supportive of social policy. On the other hand, many individuals will support social policies as long as their participation to the financing of welfare programs (through taxes and social security contributions) is perceived as fair and efficient. This requires, among other things, that other taxpayers contribute equally (no tax evasion; see Cerqueti et al., 2019; Scholz, 1998), that welfare recipients do not abuse the system (e.g., Habibov et al., 2017; Kumlin et al., 2017; Mau, 2003; Roosma et al., 2016), that the welfare system does not encourage idleness and dependency, thus reducing poverty rather than perpetuating it (Schmidtz & Goodin, 1998; Mau, 2003: 123–126; van Oorschot et al., 2012), or that government is perceived as impartial, uncorrupted and competent (Edlund, 2006; Rothstein et al., 2012; Svallfors, 2013).

A handful of empirical studies (each focusing on a particular subset of the arguments presented above) has examined whether and how welfare policy preferences depend on trust attitudes. In this research, two variables stand out: trust in government (e.g., Edlund, 1999, 2006; Hetherington & Husser, 2011; Kuziemko et al., 2015; Svallfors, 1999, 2002; Yamamura, 2014) and generalized social trust, i.e., the belief that “most people” (in contrast to “particular others” one identifies with) can be trusted (e.g., Algan et al., 2016; Bergh & Bjørnskov, 2014; Nannestad, 2008; Scholz, 1998; Sturgis & Smith, 2010; Uslaner, 2000; Warren, 2017). Overall, these studies suggest that higher levels of government and social trust are beneficial for welfare state support, even though the patterns of findings are not entirely consistent across national and time contexts (Svallfors, 1999, 2002). More importantly, however, it is likely that the effects of trust on welfare policy preferences are not completely distinct from the effects of poverty attributions—for example, if “social blame” explanations are premised on beliefs about the government’s inefficiency or anti-welfare bias, or if “individual blame” explanations are based on beliefs that most other people are untrustworthy. Hence, to disentangle the effect of poverty attributions and trust variables, both types of variables should be used simultaneously to predict welfare policy preferences.

To better delineate the effects of poverty attributions, a third check consists in considering the role of political ideology. This variable has been shown to affect both welfare policy preferences (e.g., Arts & Gelissen, 2001; Gonthier, 2017; Jacoby, 1994; Jaeger, 2006, 2008; Naumann, 2014; Wilson & Breusch, 2003) and poverty attributions (e.g., Furnham, 1982; Hunt, 2004; Hunt & Bullock, 2016; Pandey et al., 1982; Weiner et al., 2011; Zucker & Weiner, 1993). As it turns out, then, political ideology is an exogeneous variable that influences both the independent (endogenous) variable (i.e., poverty attributions) and the dependent variable (i.e., welfare policy preferences) in similar ways—for example, left-wing orientations tend to foster “social blame” explanations of poverty and pro-welfare stances, which are themselves related (see Sect. "Explanations for Poverty and Welfare Policy Preferences"). Therefore, part of the influence of political ideology might be unduly ascribed to poverty attributions if ideology is left out of the predictive model of welfare policy preferences. Our strategy will be to include ideology in our predictive model and thus to provide a rather conservative test of the effect of poverty attributions.

Besides, political ideology may be helpful to control, at least in part, for the unobservable effect of general orientations toward individualism and collectivism (see Triandis, 1995). Both at the individual level and at the cultural/country level, individualism and collectivism have been shown to influence the propensity of individuals to make internal or external attributions in general (e.g., Carpenter, 2000; Morris & Peng, 1994; Oyserman et al., 2002; Triandis et al., 1988), but also more specifically in relation to poverty attributions (e.g., Bray & Schommer-Adkins, 2016; but see Nasser & Abouchedid, 2006). Interestingly, research has demonstrated that individualism and collectivism are linked in various ways to left–right ideology. For example, studies have suggested that individualism/collectivism and left–right positions are correlated (e.g., Radkiewicz, 2017), causally related (e.g., Bréchon, 2021), “aligned” (i.e., have similar effects on social policy preferences; e.g., Yoon, 2015) or interact in predicting welfare attitudes (e.g., Toikko & Rantanen, 2020). Thus, left–right positions may serve as a proxy for orientations toward individualism and collectivism. For example, it should control for the fact that right-wing individuals have a more individualistic profile (Bréchon, 2021) and are more likely to make individual attributions of poverty.

Finally, a fourth covariate of poverty attributions is the personal experience of poverty. To be sure, people from underprivileged backgrounds may differ from their more affluent counterparts in how they explain the causes of their own misfortune, but also in their views of what social policies should be implemented to alleviate their problems. However, the intuitive expectations that poor people attribute poverty to social injustice (or at least reject the individual blame explanation) and demand more social protection from the state are not always borne out by empirical research.Footnote 1 In part, this is because “feeling poor” is a matter of both objective circumstances (e.g., struggling to “make ends meet”, being a welfare recipient) and subjective evaluations (e.g., feeling comparatively disadvantaged against peers). On the objective side, “those who have economic problems are less inclined to support the individualistic explanation than those who have never experienced financial problems” (Kallio & Niemelä, 2014: 123; see also Bullock, 1999; Lepianka, 2007; Morçöl, 1997; Niemelä, 2008). However, “the evaluation of one’s circumstances has a more pronounced influence on poverty attributions than the objective circumstances” (Lepianka, 2007: 91; see also Lepianka et al., 2010; Nilson, 1981). The enhanced influence of subjective assessments has been analyzed, in particular, in the “relative deprivation” literature. Relative deprivation is usually defined as comparative financial resources, either in relation to what one would need to “make ends meet” or in relation to what other people have (Kreidl, 2000: 157; see also Halleröd, 2006; Pedersen, 2004; Walker and Smith, 2002). Deprivation does predict attitudes toward inequalities and poverty; more specifically, it tends to be positively correlated with structuralist attributions and negatively correlated with individualistic attributions (Kreidl, 2000). Finally, “social stigma appears to be an important element within the experience of poverty” (Hirschl et al., 2011: 366; see also Garthwaite, 2016; Patrick, 2014; Walker, 2014). In turn, feelings of shame are sometimes related to poverty attributions. At least in contexts characterized by strong resentment against “scroungers” (e.g., Britain), needy people who are shameful of their condition tend to dissociate themselves from “the poor” and to put the blame on them (Shildrick, 2018; Shildrick & MacDonald, 2013). Against this background, we will test the effect of objective and subjective measures of poverty in one of our robustness checks (see Table A6).

Hypotheses

Based on the above discussion, we can now summarize our main expectations about the effects of poverty attributions on welfare policy preferences. First, we expect that individuals endorsing a social blame explanation of poverty will be the most supportive of state intervention to reduce social inequalities. Second, individuals endorsing an individual blame explanation are expected to be the least supportive of social welfare policies. Third, individuals attributing poverty to fatalistic causes (“individual fate” or “social fate”) do not put the blame on the poor themselves, neither do they hold the social system responsible for poverty. In other words, “the fatalistic view of poverty can lead to society’s resignation towards poverty as it has no social responsibility for the phenomenon” (Da Costa & Dias, 2014: 1410). Yet, based on our discussion at the end of Sect. "Explanations for Poverty and Welfare Policy Preferences", individuals endorsing fatalistic views of poverty should demand some degree of social protection to reduce glaring social inequalities and to prevent a breakdown of the social system, but without aiming to solve the (supposedly unsolvable) problem of poverty. Accordingly, fatalistic individuals are expected to fall in between the two previous types, i.e., they should be mildly supportive of social protection. Fourth, controlling for the influence of the covariates of poverty attributions reviewed in Sect. "Covariates of Poverty Attributions" may well reduce the effect of poverty attributions on welfare policy preferences, but this effect should not fade altogether. Formally, we formulate the following hypotheses:

H1

Individuals attributing poverty to individual blame are less supportive of social policy than those providing other types of explanations for poverty.

H2

Individuals attributing poverty to social blame are more supportive of social policy than those attributing poverty to other types of explanations.

H3

Individuals attributing poverty to fatalistic causes (i.e., individual fate and social fate) are more supportive of social policy than those attributing poverty to individual blame and less supportive than those attributing poverty to social blame.

H4

The previous hypotheses hold even after controlling for the effects of deservingness judgments, trust, ideology, and personal experience of poverty.

To be sure, some of these hypotheses are not entirely new to research on poverty attributions. Various measures and typologies have been used to predict social preferences (see Sect. "Explanations for Poverty and Welfare Policy Preferences"). However, to the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to use the full four-type typology of poverty attributions as a main predictor of social preferences.

Measurements

Empirical Data

Our empirical analysis is based on the Eurobarometer, which is one of the few international surveys which at least in some rounds includes questions on both explanations for poverty and social policy preferences. This survey series, initiated in 1973 by the European Commission, has included a standard question on explanations for poverty in eight surveys spanning a period of nearly 40 years (1976–2014). Unfortunately, only one of the survey waves includes all dependent, independent, and control variables; two other waves only lack some of the covariates of poverty attributions, which will restrict the time range of some robustness checks. Therefore, the present analysis will focus on the three latest relevant EB surveys for the years 2009 (EB 72.1), 2010 (EB 74.1), and 2014 (EB 81.5). The survey was run in all EU member countries. Our analyses focus on the 27 countries that were EU members throughout the period between 2009 and 2014.

The Eurobarometer surveys cover the resident population of EU member states aged 15 years and more. In each state, a sample is drawn using a multi-stage random sampling procedure, with stratification by administrative regional unit and type of area (metropolitan/urban/rural). All interviews were conducted face-to-face at the respondents’ place of residence.

Dependent Variables: Welfare Attitudes

For convenience reasons, we will refer to the four dependent variables in our empirical analyses as “welfare attitudes,” even though they relate to welfare issues to varying degrees.

The first item is related to judgments about the level of economic inequality. Respondents were asked the extent to which they agree with the statement: “Nowadays in (OUR COUNTRY) income differences between people are far too large.” Response categories ranged from totally agree to totally disagree. Answers exhibited a very skewed distribution, with 56% of respondents who “totally agree,” 33% who “tend to agree,” and only 12% in all other categories. Given this strong asymmetry, we chose to make the variable comparable to the other outcome variables and to dichotomize it—“totally agree” answers were assigned a value of 1 and contrasted with the remaining four categories, coded as 0 (“tend to agree,” “disagree,” “strongly disagree,” and “don’t know”).

The second item is related to the role of the state versus private sector in mitigating unemployment. The question reads: “People think differently on what steps should be taken to help solving social and economic problems in (OUR COUNTRY). I’m going to read you two contradictory statements on this topic. Please tell me which one comes closest to your view.” The three answer categories are: “It is primarily up to the (NATIONALITY) Government to provide jobs for the unemployed”; “Providing jobs should rest primarily on private companies and markets in general” and “It depends (SPONTANEOUS).” We have recoded the three potential answer categories into two, where 1 corresponds to the first statement showing clear support for the state intervention whereas the other two statements were coded zero.

The third item is the allocation of responsibility for welfare, asking respondents whether “Government should take more responsibility to ensure that everyone is provided for” or “People should take more responsibility to provide for themselves.” Similar to the previous items, responses are dichotomized, with a score of 1 for answers calling for more responsibility to be taken by the government and a score of 0 for all other answers.

The last item is the prioritization of social protection over taxes. It stems from the question asking respondents for their preference between two statements: “Higher level of health care, education and social spending must be guaranteed, even if it means that taxes might increase,” or “Taxes should be decreased even if it means a general lower level of health care, education and social spending.” A preference for social protection over taxes is contrasted (score = 1) with both preferences for tax decreases and the spontaneous indication that “it depends” (score = 0).

Overall, the four dependent measures of welfare attitudes are weakly interrelated, thus excluding the possibility of creating a compound scale of respondents’ attitudes (for more detail, see Supplementary Information). Besides, as our empirical analyses will show, the causal structure of factors affecting each dependent measure is heterogenous, making the creation of a single variable undesirable.

Independent Variables: Poverty Attributions

The question asking respondents for their explanations for poverty was asked in the following way: “Why in your opinion are there people who live in poverty? Here are four opinions: which is closest to yours?” [Figures in brackets report the EU-27 (i.e., without Croatia) average percentage of each poverty attribution for the years 2009, 2010, and 2014, respectively.]

-

1.

Because they have been unlucky (individual fate) [13.6/13.9/14.0]

-

2.

Because of laziness and lack of willpower (individual blame) [17.3/16.1/14.3]

-

3.

Because there is much injustice in our society (social blame) [47.3/47.4/49.0]

-

4.

Because it’s an inevitable part of progress (social fate) [17.0/16.9/14.9]

A fifth category (in addition to DKs) was created for respondents who spontaneously claimed that “none of these” options reflected their true opinion on the question [4.9/5.7/7.9].

Overall, nearly one respondent in two attributes poverty to social injustice (social blame), which makes it by far the most popular explanation. The other half of answers are distributed rather evenly among the other explanations (individual fate, individual blame and social fate), each of which gets slightly more or less than 15 percent of responses. The average values are relatively stable between the three years, even though more variation can be observed at the country level—for example, the frequency of social blame attributions soared by 15–20% points in some Southern and Eastern countries like Spain, Cyprus or Slovakia between 2009/2010 and 2014.

Interestingly, less than a third of European respondents, on average, expressed individualistic poverty attributions. This stands in stark contrast with the findings usually obtained in other contexts like the USA, where individualistic explanations prevail (Hunt & Bullock, 2016). In part, this discrepancy between research findings probably reflects true cultural differences between Europe and other contexts. Britain, as a society akin to the American individualistic culture, is one of only two countries where individualistic attributions exceed 40 percent in all three survey waves, which lends support to the cultural interpretation; the other case is Denmark, where unlike Britain, the social fate explanation is clearly more popular than the social blame explanation.

Of course, differences in research methods and measurements may also play a role and, therefore, the results obtained with our typology may not be strictly comparable to the results of studies using different methodologies. To be sure, like any method for measuring poverty attributions, the four-type typology can be assessed from several perspectives. For one thing, the typology is a cost-effective alternative to longer lists of items from which separate subscales of poverty explanations are usually extracted via factor analysis. Studies using the four-category typology have confirmed its relevance for spatial and temporal comparison (e.g., Marquis, 2020; van Oorschot & Halman, 2000), though sometimes with reservations about the interpretation of the social fate category (e.g., Kainu & Niemelä, 2014; Lepianka et al., 2009). At the same time, unlike the factor-analytic method, the typology is premised on mutually exclusive response categories and thus precludes investigation into the ambivalence of poverty explanations (see footnote 1). In contrast, one major drawback of factor analysis and other exploratory methods is that, depending on the circumstances of the population surveyed or the criteria used for factor extraction, each separate study can come up with additional “meaningful” dimensions or with different interpretations of existing dimensions (e.g., Cozzarelli et al., 2001; Bullock, 2004; da Costa & Dias, 2014; Panadero & Vázquez, 2008). For comparative purposes, then, the four-type typology of poverty attributions seems to have some advantages over alternative measurement methods.

Control Variables

Our analyses also include a number of control variables. All definitions and descriptive information about these variables are detailed in the Supplementary Information available online.

First, we control for structural variables determining individuals’ position in society. These allow to grasp respondents’ self-interest in relation to the welfare state by measuring their economic assets (income), skills (education) as well as specific location in the job market (occupation), which have all been found to affect individual demands for the welfare state (e.g., Iversen & Soskice, 2001). We further control for gender and age (including age squared and age cubic to account for possible nonlinear effects of age; see Supplementary Information for more information).

We also include a variable measuring respondents’ exposure to poverty based on a question on how often they encounter poor people in their daily life. This variable can be expected to influence social preferences in two ways. First, the direct exposure to poverty in one’s immediate environment probably elicits demands for social protection in favor of one’s relatives, friends or intimate social groups—and probably also for oneself. In fact, ingroup favoritism in the formation of welfare policy preferences is a well-known phenomenon, whereby poor people “like us” are perceived to be more deserving of welfare support (e.g., Bloemraad et al., 2019; Everett et al., 2015; Kootstra, 2017; Magni, 2020). Thus, frequent exposure to poverty in one’s surroundings may prime social identities and enhance the conflict between haves and have-nots (Costa-Font & Cowell, 2014; Sumino, 2018). Second, exposure to poverty has sometimes been analyzed as a cause of explanations for poverty (e.g., Wilson, 1996: 422; Hopkins, 2009; Hunt & Bullock, 2016: 104–105), and it may thus have an indirect effect on social preferences. In our view, however, both exposure to poverty and explanations of poverty can be considered as antecedents of welfare attitudes. By testing the effects of both variables in the same model (as well as other relevant control variables such as income or occupation; see above), we ensure that the explanatory capacity of poverty attributions is not significantly conflated with self-interest or group interests. The four levels of exposure to poverty will be entered separately (as dummy variables) in our model to account for a possible nonlinear relationship with welfare attitudes.

Finally, as a special kind of control variables, the covariates of poverty attributions discussed in Sect. "Covariates of Poverty Attributions" will be included in our predictive model insofar as relevant data are available from the Eurobarometer series. Interpersonal trust and trust in government were assessed in all three waves (2009, 2010, and 2014) on a 10-point scale where higher values indicate higher degrees of trust in others and in government. In contrast, questions about the deservingness of specific groups were asked only in the 2009 and 2010 surveys. The measures are dummy variables indicating whether a given group “should be prioritized in receiving social assistance” or not (coded 1 and 0, respectively). Nine groups were taken into account in these deservingness questions: single parents, immigrants, people suffering from addictions (e.g., alcohol, drugs), homeless people, abandoned or neglected children, young offenders, disabled people, unemployed people, and elderly people. As for ideology, left–right self-placements were assessed only in the 2010 survey on a 1 (extreme left) to 10 (extreme right) scale. Finally, personal experiences of poverty were measured in 2009 and 2010 by four indicators: (a) being a user of social services (dummy variables for none, one, two to five); (b) subjective income, i.e., the extent to which one’s total monthly (household) income is enough “to make ends meet” (1‒6 scale ranging from “very easily” to “with great difficulty”); (c) comparative income, i.e., an evaluation of one’s actual income in comparison with the income necessary “to have a minimum acceptable standard of living” (1‒5 scale ranging from “much higher” to “much lower”); (d) a subjective evaluation of one’s household situation (1‒10 scale ranging from “very poor” to “very wealthy”).

Empirical Results

Overall Findings

Given the hierarchical nature of the dataset with each survey (country × year) including several hundreds of individuals, we model this data using multilevel models. In these 2-level models, individuals are nested in countries; thus, the models take into account the shared variance at the country level. We run separate models for each of the years for which we have data. We use a logistic model given the binary nature of our dependent variables: judgments about inequality, about unemployment, attribution of responsibility for welfare to the government, and prioritization of social policy over taxes.

Results of these models are displayed in Table 2. For poverty attributions, the reference category is individual blame (i.e., laziness, lack of willpower). Hence the effects of the four other categories are to be read in contrast to the individual blame explanation. The model includes the “none of these” attribution (6.4% of cases), for which we have no expectation and whose effects are highly variable across welfare attitudes and years. Hence, we refrain from interpreting results related to this category, but we keep it to ensure sample representativeness. (As shown by additional analyses, taking out those respondents from the models does not change our results.)

Consistent with our expectations, we find that explanations for poverty have a significant effect on welfare state attitudes. The patterns differ, however, to some extent across the four dependent variables. A pattern consistent with expectations emerges in relation to judgments about inequality, unemployment, and welfare responsibility. In all three cases, attributing poverty to social blame, social fate or individual fate tends to increase the probability of favoring state intervention. The magnitude of the effect is particularly large for the social blame attribution and more moderate (or inexistent in some cases) for the social fate and individual fate attributions.

As regards the prioritization of social protection over taxes, we find positive effects of social fate attributions. In substance, these small (but statistically significant) effects mean that individuals who view poverty as an inevitable consequence of the “modern world” are more willing to expand social protection (be it through higher taxes) than individuals who attribute poverty to individual failure. In contrast, individuals providing social blame and individual fate explanations are not different from individuals who blame poverty on the poor themselves. An exception to this pattern is that social blame explanations were also related to higher demands for social protection in 2009, but not anymore in the following years—perhaps as a result of austerity policies being implemented in many countries, instilling fears that higher taxes may afflict underprivileged classes already impoverished by the crisis.

Importantly, the models are remarkably similar across years, suggesting that the effects of poverty attribution on welfare attitudes remained rather stable over the period considered. In Fig. 1, we examine the magnitude of these various effect by means of predicted probabilities of supporting each of the four welfare attitudes, conditional on poverty attributions (and all other variables being kept at their observed values). Table A2 in the Supplementary Information lists the contrasts between predicted probabilities for each of the four poverty attributions, together with their statistical significance, allowing us to test our hypotheses more systematically.

Figure 1 shows that the absolute level of support for pro-welfare positions declines over time. For instance, for each of the poverty attributions support for unemployment is lower in 2014 than in previous years. In contrast, the substantial effects of poverty attributions on support for social policy do not change substantially over time—instead, these effects vary markedly according to policy type. Regarding inequality, unemployment, and the role of government for social welfare, attributing poverty to social blame (injustice) is associated with a higher probability of supporting the welfare state, compared to other poverty attributions. The gap is particularly large with respect to individuals attributing poverty to individual blame. It is, however, also substantial compared to respondents attributing poverty to individual or social fate. To give an example, the predicted probability of supporting social welfare is about 14% points higher for those respondents who attribute poverty to social blame than those who attribute it to social or individual fate. The gap reaches about twenty percentage points when comparing those respondents who attribute poverty to social blame with those who attribute it to individual blame. On these first three welfare attitudes, the ordering of the various explanations for poverty is similar between cases and support our hypotheses. Social blame is associated with the highest support for social policy, followed by both types of fatalistic explanations.

At the other end of the spectrum, individual blame is associated with the lowest probability to support social policy. Although the pattern is similar across the three welfare attitudes, the magnitude of the effect of poverty attributions is larger in the case of broad attitudes regarding inequality and responsibility of social welfare than in the case of the more concrete item asking about responsibility for mitigating unemployment.

The results concerning these first three welfare attitudes (judgments about inequality, unemployment, and social welfare) contrast starkly with the results regarding the question on the prioritization of welfare policies above taxes. There, we find hardly any differences between different poverty attributions, except for a (modest) overemphasis on social protection among individuals endorsing a “social fate” view of poverty. In sum, this analysis of the main effects of poverty attributions on welfare attitudes shows that these effects differ between our four measures of welfare attitudes. Broadly speaking, it seems that the explanatory factors for judgments about inequality, assigning unemployment and welfare responsibility to the state are similar. In contrast, the determinants of preferences for social protection (over taxes) are different. In that case, poverty attributions hardly play any role in explaining preferences. When asked about the role of the state in a general fashion, individuals who attribute responsibility for poverty to social injustice are particularly likely to support welfare. However, when this comes with a trade-off and increased taxes, they are not more likely than other respondents to support the welfare state. Nevertheless, the results for other items make clear that poverty attributions are important predictors of welfare attitudes, above and beyond the effects of the many predictors related to individuals’ self-interest included in the analysis. In line with our expectations, attributing poverty to laziness and lack of willpower (individual blame) is associated with low demands for social policy. On the other hand, the most common explanation for poverty in European countries—social injustice—is associated with more demand for social policy. Overall, Hypotheses 1–3 are confirmed by our empirical analysis.

Robustness Checks

Our next set of analyses provides a number of important robustness checks. For reasons of brevity, the tables reporting our results (Tables A3-A9) are included in the online Supplementary Information. The first additional analysis concerns contextual variation in the effects of poverty attributions. As shown in Fig. 1, there are indeed some differences across years. But how significant are these differences across both years and countries? To answer this question, we tested a three-level model in which country × year observations are nested in countries, and where a random intercept and random slopes for each poverty attribution are estimated at both higher levels (see Table A2 in the Supplementary Information). Findings reveal that there is variation in the four welfare attitudes across both time and space, as indicated by significant random intercept variances for each attitude. Interestingly, models also suggest that contextual variation in the effects of poverty attributions tend to concentrate on the social blame vs. individual blame contrast, as variance components (random slopes) are significant for most (though not all) effects of the social blame attribution, but not for other attributions. In other words, there is evidence that the effects of social blame attributions vary across time (inequalities), across space (unemployment, welfare vs. taxes), or across both (social welfare). Finally, and most importantly, this (rather small) share of variance in the effects of poverty attributions that can be accounted for at the aggregate level does not change anything substantial to the fixed effects of attributions computed at the individual level—all coefficients retain their magnitude, sign, and statistical significance. As an exception, the marginally significant (and positive) effect of the social blame explanation (p = 0.07) for the welfare vs. taxes statement merely reflects the fact that this effect is only significant (and positive) for the year 2009 (see Table 2).

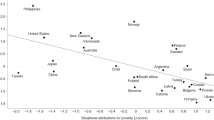

To investigate further the differences in the validity of the general model summarized in Fig. 1, we tested separate models for each country in each survey wave and for each dependent variable. Drawing on the findings from Table A2, we focused our attention on the effects of social blame attributions. Figure 2 displays regression coefficients for the social blame poverty attribution (with individual blame as the reference category). Overall, the country-specific models uncover a good deal of causal heterogeneity related to particular circumstances of the various European countries. More importantly, however, they strongly confirm the two main results of our analysis. First, the way in which people conceptualize the causes of poverty underlies some of their social attitudes. Second, this relationship is conditional on the type of social attitudes we focus on: It is strong for perceptions of social inequalities and for general welfare attitudes, and it is weaker—or arguably more context-dependent—for attitudes on the unemployment and “taxes versus social protection” issues. As a matter of fact, drawing on the 81 models (27 countries × 3 survey waves) tested for each of the four social attitudes, it appears quite clearly that the share of significant effects of social blame attributions varies considerably between social welfare attitudes (86% significant) and perceptions of inequalities (78%), on the one hand, and attitudes on unemployment (42%) and taxes (22%), on the other hand. This overall difference between the two groups of attitudes is more or less constant across countries (see Fig. 2).

Logistic regression coefficients for the social blame explanation by country and year (95% confidence intervals). Notes: Country codes: 1: Austria; 2: Belgium; 3: Bulgaria; 4: Cyprus; 5: Czech Republic; 6: Denmark; 7: Estonia; 8: Finland; 9: France; 10: Germany; 11: Greece; 12: Hungary; 13: Ireland; 14: Italy; 15: Latvia; 16: Lithuania; 17: Luxembourg; 18: Malta; 19: Netherlands; 20: Poland; 21: Portugal; 22: Romania; 23: Slovakia; 24: Slovenia; 25: Spain; 26: Sweden; 27: United Kingdom

Second, we want to test whether the results regarding the effect of poverty attributions on welfare state preferences are robust to the inclusion of covariates that could drive the results. We focus on four categories of covariates discussed in Sect. "Covariates of Poverty Attributions". Specifically, we assume that welfare preferences are dependent on poverty attributions, but also on other individual characteristics such as respondents’ levels of trust (interpersonal and institutional), their perception of the deservingness of welfare state recipients, their political ideology, and/or their personal experience of poverty. Because poverty attributions may be related to each of these variables, their effects on welfare attitudes may be confounded with those of trust, deservingness judgments, ideology, and personal experiences.

Accordingly, we run four types of models that include measurements of these additional variables, first separately, and then all included at once. In the first set of models (Table A4 in the Supplementary Information), we add variables controlling for social trust as well as trust in government. We then focus on deservingness and run models that include controls for perceived deservingness for the years 2009 and 2010 for which these variables are available in the Eurobarometer data (see Table A5). In Table A6, we report results controlling for left–right ideology—as this variable is only present in the 2010 Eurobarometer data, we focus on that year. Next, we include controls for the personal experience of poverty, which are only available for the years 2009 and 2010 (see Table A7 in the Supplementary information). Finally, the full models including all variables simultaneously are reported in Table A8.

In summary, each of the additional control variables has some effect on the outcome variables. There is a strong positive association between welfare preferences and perceiving some groups as deserving of public assistance. There is also a clear effect of ideology on these preferences, with left-wing respondents being more likely to support welfare policy. The effects of interpersonal trust and trust in government are also significant in most of the models, though the direction of these effects differs across attitudes and years. However, even with these controls, the effect of poverty attributions on welfare preferences remains strong. These results provide strong evidence that there is a direct effect of poverty attribution on welfare state preferences that cannot be attributed to trust, perceptions of deservingness, ideology, or personal experiences.

Arguably, the most conservative test of our model is provided in Table A8 in the Supplementary Information. This test focuses on the year 2010, because this is the only Eurobarometer survey containing all control variables. Nevertheless, this most comprehensive account of the causes of social preferences confirms the main findings obtained in earlier tests. As shown in Fig. 3, predictive margins for the four welfare attitudes allow us to reach two main conclusions (see also Table A9 in the Supplementary Information for detailed differences between each poverty attribution). First, in general, individuals endorsing a social blame explanation of poverty are the most supportive of the welfare state, and individuals endorsing an individual blame explanation are the least supportive. Second, there are notable exceptions to this general pattern: (a) Poverty attributions are poorly discriminant for opinions on the welfare vs. taxes issue, and (b) the effect of the individual blame explanation of poverty is hardly different from either the individual or social fate explanations for the inequality and unemployment attitudes. Overall, preferences on the social welfare item (i.e., deciding whether the state or the individual is responsible for everyone’s welfare) provide the strongest support for our hypotheses.

Conclusion

Popular explanations for poverty have been at the heart of sociological work on the welfare state in the 1970s and 1980s, but interest in the topic has somewhat dwindled since then. In particular, research has only seldom addressed the effect of explanations for poverty on actual policy preferences, assuming rather than studying the link. This link becomes particularly relevant in the post economic crisis period which saw the first major shift in explanations for poverty since the 1970s. We argue that poverty attributions inform about individuals’ perceptions of deservingness of welfare state beneficiaries as well as about their views regarding the ability of society to curb poverty and therefore should be closely related to policy preferences.

Our analysis of Eurobarometer survey data from 27 EU countries shows the relevance of these arguments. Looking at the impact of poverty attributions on welfare attitudes (judgments about inequality, unemployment, responsibility for welfare, and the social protection vs. taxes trade-off), we find that those respondents attributing poverty to individual blame (laziness and lack of willpower) are less likely to support state intervention. The contrast is particularly striking with those individuals who attribute poverty to social blame (injustice). Individuals who attribute poverty to individual or social fate are found somewhere in between these two extremes when asked about their preferences regarding the welfare state. However, these effects are substantial only for questions regarding general preferences about the welfare state. There are no systematic differences between individuals attributing poverty to different explanations in relation to their support of welfare state if this means increased taxes.

These results are significant in several ways. First, they show the importance of poverty attribution in the formation of broad policy preferences, something that has been overlooked in the empirical literature in recent years. Second, they also show that poverty attributions only impact preferences on some broad dimensions regarding the role of the state in the economy but not on more specific preferences related to taxation. To some extent, this might explain the puzzling observation that despite a change in overall poverty attributions in the last decade, support for redistribution or the share of left parties’ supporters has hardly increased in European countries. Future research should pay more attention to the cross-country variations in the effect of poverty attribution on the various types of policy preferences.

Notes

In the USA, for instance, many citizens have been found to be deeply ambivalent toward issues of redistribution and social justice (e.g., Hochschild, 1979, 1981; Kluegel & Smith, 1986), in the sense that they tend to ascribe poverty to both individual (e.g., laziness) and structural (e.g., social discrimination) causes. This phenomenon of “split consciousness” (Kluegel et al. 1995) or “dual consciousness” (Bullock & Waugh, 2005; Godfrey & Wolf, 2016; Hunt, 1996, 2016; Merolla et al., 2011) is widespread, but it tends to be concentrated among disadvantaged groups such as racial minorities, whereas it is less prevalent among well-educated and high-income groups. Such ambivalence among underprivileged people may be explained by the fact that their inner feelings of injustice are counterbalanced by their commitment to the “dominant ideology” (Kluegel & Smith, 1986) of economic individualism and responsibility—other designations found in the literature all point to the same phenomenon, whether it be “meritocracy” (Godfrey & Wolf, 2016), the “American ethos” (McClosky & Zaller, 1984), the “metatheory” of individualism (Smith & Stone, 1989), or a “belief in the American Dream” (Schlozman & Verba, 1979).

References

Aalberg, Toril. (2003). Achieving justice: comparative public opinion on income distribution. Brill.

Aarøe, L., & Petersen, M. B. (2014). Crowding out culture: Scandinavians and Americans agree on social welfare in the face of deservingness cues. Journal of Politics, 76(3), 684–697.

Alesina, A., Glaeser, E., & Sacerdote, B. (2001). Why doesn’t the US have a European-type welfare state? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 2(2001), 187–277.

Algan, Y., Cahuc, P., & Sangnier, M. (2016). Trust and the welfare state: The twin peaks curve. The Economic Journal, 126, 861–883.

Alston, J. P., & Imogene Dean, K. (1972). Socioeconomic factors associated with attitudes toward welfare recipients and the causes of poverty. Social Service Review, 46(1), 13–23.

Andress, H.-J., & Heien, T. (2001). Four worlds of welfare state attitudes? A Comparison of Germany, Norway, and the United States. European Sociological Review, 17(4), 337–356.

Appelbaum, L. D. (2001). The Influence of perceived deservingness on policy decisions regarding aid to the poor. Political Psychology, 22(3), 419–442.

Arikan, G., & Bloom, P.-N. (2015). Social values and cross-national differences in attitudes towards welfare. Political Studies, 63, 431–448.

Armour, P. K., & Coughlin, R. M. (1985). Social control and social security: Theory and research on capitalist and communist nations. Social Science Quarterly, 66(4), 770–788.

Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2001). Welfare states, solidarity and justice principles: Does the type really matter? Acta Sociologica, 44, 283–299.

Benabou, R., & Ok, E. A. (2001). Social mobility and the demand for redistribution: The POUM hypothesis. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116(2), 447–487.

Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Belief in a just world and redistributive politics. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 699–746.

Bergh, A., & Bjørnskov, C. (2014). Trust, welfare states and income inequality: Sorting out the causality. European Journal of Political Economy, 35, 183–199.

Bloemraad, I., Kymlicka, W., Lamont, M., & Leanne, S. S. H. (2019). Membership without social citizenship? Deservingness and redistribution as grounds for equality. Dædalus, 148(3), 73–104.

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (2000). Reciprocity, self-interest, and the welfare state. Nordic Journal of Political Economy, 26, 33–53.

Bradley, C., & Cole, D. J. (2002). Causal attributions and the significance of self-efficacy in predicting solutions to poverty. Sociological Focus, 35(4), 381–396.

Bray, S. S., & Schommer-Aikins, M. (2016). Health professions students’ ways of knowing and social orientation in relationship to poverty beliefs. Psychology Research, 6(10), 579–589.

Bréchon, P. (2021). Individualisation rising and individualism declining in France: How can this be explained? French Politics: Advance Publication. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-020-00139-1

Brisman, A. (2012). Ritualized degradation in the twenty-first century: A revisitation of piven and cloward’s regulating the poor. Seattle Journal for Social Justice, 10(2), 793–814.

Bullock, H. E. (2004). From the front lines of welfare reform: An analysis of social worker and welfare recipient attitudes. Journal of Social Psychology, 144(6), 571–590.

Bullock, H. E. (1999). Attributions for poverty: A comparison of middle-class and welfare recipients attitudes. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(10), 2059–2082.

Bullock, H. E., & Waugh, I. M. (2005). Beliefs about poverty and opportunity among mexican immigrant farm workers. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 35(6), 1132–1149.

Bullock, H. E., Wyche, K. F., & Williams, W. R. (2001). Media images of the poor. Journal of Social Issues, 57(2), 229–246.

Bullock, H. E., Williams, W. R., & Limbert, W. M. (2003). Predicting support for welfare policies: The impact of attributions and beliefs about inequality. Journal of Poverty, 7(3), 35–56.

Bullock, H. (2006). Justifying inequality: A social psychological analysis of beliefs about poverty and the poor. National Poverty Center Working Paper Series #06–08.

Burgoyne, C. B., Routh, D. A., & Sidorenko-Stephenson, S. (1999). Perceptions, attributions and policy in the economic domain: A theoretical and comparative analysis. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 40(1), 79–93.

Carpenter, S. (2000). Effects of cultural tightness and collectivism on self-concept and causal attributions. Cross-Cultural Research, 34(1), 38–56.

Cerqueti, R., Sabatini, F., & Ventura, M. (2019). Civic capital and support for the welfare state. Social Choice and Welfare, 53, 313–336.

Chafel, J. A. (1997). Society images of poverty: Child and adult beliefs. Youth & Society, 28(4), 432–463.

Chafel, J. A., & Neitzel, C. (2005). Young children’s ideas about the nature, causes, justification, and alleviation of poverty. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 20(4), 433–450.

Costa-Font, J., & Cowell, F. (2014). Social identity and redistributive preferences: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 29(2), 357–374.

Cozzarelli, C., Wilkinson, A. V., & Tagler, M. J. (2001). Attitudes toward the poor and attributions for poverty. Journal of Social Issues, 57(2), 207–227.

Da Costa, L. P., and Dias, J. G. (2014). Perceptions of Poverty Attributions in Europe: A Multilevel Mixture Model Approach. Quality and Quantity, 48(3), 1409‒1419.

Delton, A. W., Petersen, M. B., DeScioli, P., & Robertson, T. E. (2018). Need, compassion, and support for social welfare. Political Psychology, 39(4), 907–924.

Deutsch, M. (1985). Distributive justice: A social-psychological perspective. Yale University Press.

Dodenhoff, D. (1998). Is welfare really about social control? Social Service Review, 72(3), 310–336.

Edlund, J. (1999). Trust in government and welfare regimes: Attitudes to redistribution and financial cheating in the USA and Norway. European Journal of Political Research, 35, 341–370.

Edlund, J. (2006). Trust in the capability of the welfare state and general welfare state support: Sweden 1997–2002. Acta Sociologica, 49(4), 395–417.

Everett, J. A. C., Nadira, S. F., & Molly, C. (2015). Preferences and beliefs in ingroup favoritism. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2015.00015

Feagin, J. R. (1972). Poverty: We still believe that god helps those who help themselves. Psychology Today, 6(6), 101–129.

Feather, N. T. (1994). Human values and their relation to justice. Journal of Social Issues, 50(4), 129–151.

Feather, N. T. (1999). Values, achievement, and justice: Studies in the psychology of deservingness. NewYork: Kluwer Academic.

Feather, N. T. (1974). Explanations of poverty in Australian and American samples: The person, society, or fate? Australian Journal of Psychology, 26(3), 199–216.

Fong, C. M., Samuel, B., & Herbert, G., et al. (2005). Reciprocity and the welfare state. In H. Gintis (Ed.), Moral sentiments and material interests the foundations of cooperation in economic life (pp. 277–302). MIT Press.

Fong, C. (2001). Social preferences, self-interest, and the demand for redistribution. Journal of Public Economics, 82, 225–246.

Furnham, A. (1982). Why are the poor always with us? Explanations for poverty in Britain. British Journal of Social Psychology, 21, 311–322.

Furnham, A. (2003). Poverty and wealth. In C. C. Stuart & S. S. Tod (Eds.), Poverty and psychology: From global perspective to local practice (pp. 163–183). Springer.

Garthwaite, K. (2016). Stigma, shame and ‘people like us’: An ethnographic study of foodbank use in the UK. Journal of Poverty and Social Justice, 24(3), 277–289.

Gilens, M. (1999). Why Americans hate welfare: Race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. University of Chicago Press.

Godfrey, E. B., & Wolf, S. (2016). Developing critical consciousness or justifying the system? A qualitative analysis of attributions for poverty and wealth among low-income racial/ethnic minority and immigrant women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22(1), 93–103.

Gonthier, F. (2017). Parallel publics? Support for income redistribution in times of economic crisis. European Journal of Political Research, 56(1), 92–114.

Habibov, N., Cheung, A., & Auchynnikava, A. (2017). Does trust increase willingness to pay higher taxes to help the needy? International Social Security Review, 70(3), 3–30.

Halleröd, B. (2006). Sour Grapes: Relative Deprivation, Adaptive Preferences and the Measurement of Poverty. Journal of Social Policy, 35(3), 371‒390.

Halman, L., & van Oorschot, W. (1999). Popular perceptions of poverty in Dutch society. WORC paper Vol. 99.11.01. Tilburg University, Work and Organization Research Centre.

Hansen, K. J. (2019). Who cares if they need help? The deservingness heuristic, humanitarianism, and welfare opinions. Political Psychology, 40(2), 413–430.

Harper, D. J. (1996). Accounting for poverty: From attribution to discourse. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 6, 249–265.

Hasenfeld, Y., & Rafferty, J. A. (1989). The determinants of public attitudes toward the welfare state. Social Forces, 67(4), 1027–1048.

Häusermann, S., & Walter, S. (2010). Restructuring swiss welfare politics: Post-industrial labor markets, globalization, and welfare values. In Hug S. & K. Hanspeter (Eds.), Value change in Switzerland (pp. 137–161). Lexington Book.

Hetherington, M. J., & Husser, J. A. (2011). How trust matters: The changing political relevance of political trust. American Journal of Political Science, 56(2), 312–325.

Hirschl, T., Rank, M., & Kusi-Appouh, D. (2011). Ideology and the experience of poverty risk: Views about poverty within a focus group design. Journal of Poverty, 15(3), 350–370.

Hochschild, J. L. (1981). What’s fair? American beliefs about distributive justice. Harvard University Press.

Hochschild, J. L. (1979). Why the dog doesn’t bark: Income, attitudes and the redistribution of wealth. Polity, 11(4), 478–511.

Hopkins, D. J. (2009). Partisan reinforcement and the poor: The impact of context on explanations for poverty. Social Science Quarterly, 90(3), 744–764.