Abstract

Mandarin universal terms such as mei-NPs in preverbal positions usually require the presence of dou ‘all/even’. This motivates the widely accepted idea from Lin (Nat Lang Semant 6:201–243, 1998) that Mandarin does not have genuine distributive universal quantifiers, and mei-NPs are disguised plural definites, which thus need dou—a distributive operator (or an adverbial universal quantifier in Lee (Studies on Quantification in Chinese. Ph. D. thesis, UCLA), Pan (in: Yufa Yanjiu Yu Tansuo [Grammatical Study and Research], vol 13, pp 163-184. The Commercial Press)—to form a universal statement. This paper defends the opposite view that mei-NPs are true universal quantifiers while dou is not. Dou is truth-conditionally vacuous but carries a presupposition that its prejacent is the strongest among its alternatives (Liu in Linguist Philos 40(1):61–95, 2017b). The extra presupposition triggers Maximize Presupposition (Heim in: Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenssischen Forschung, pp 487-535. de Gruyter, Berlin, 1991), which requires [dou S] block [S] whenever dou’s presupposition is satisfied. This explains the mei-dou co-occurrence, if mei-NPs are universal quantifiers normally triggering individual alternatives (thus stronger than all the other alternatives). The proposal predicts a more nuanced distribution of obligatory-dou, not limited to universals and sensitive to discourse contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 The puzzle and Lin’s decompositional solution

Mandarin universal terms such as mei/suoyou-NPs in preverbal positions usually have to co-occur with the famous multi-functional adverb dou, often glossed as ‘all’ in this environment. This is puzzling. If mei/suoyou-NPs are universal quantifiers like English every/all-NPs, it is unclear why an additional all is needed (or even possible), as shown by the impossibility of combining every/all-NP with another all in (2b) and the contrast between (2a) and (2b)Footnote 1

A well-known solution proposed in Lin (1998) and recently advocated by Zhang and Pan (2019) denies the status of mei/suoyou-NPs as genuine universal quantifiers (of type \(\langle et,t \rangle \)), and takes them to be referential (of type e), synonymous with plural definites. Concretely, mei-ge san-nianji xuesheng, according to Lin, denotes (by referring to) \(\oplus \textsc {third.grade.student}\)—the maximal mereological sum of all entities in the third.grade.student set, as in the classical analysis of plural definite description (Sharvy 1980; Link 1983), and mei is a (generalized) sum operator Footnote 2Footnote 3. To illustrate, in context \(c_1\), where there are exactly three third-grade students Zhangsan, Lisi and Wangwu, and the speaker is pointing at them, mei-ge san-nianji xuesheng and the plural definite zhexie san-nianji xuesheng ‘these third-year students’ receive, according to this view the same denotation, both referring to the sum \(\textsc {zs}\oplus \textsc {ls}\oplus \textsc {ww}\). This equivalence between mei-NPs and plural definites is explicitly stated in Lin (1998: 241) “summarizing, I have proposed to account for the cooccurrence between dou and universal NPs with mei by treating the latter as denoting the same kind of entity as NPs of the form the N”.

Next, Lin takes dou to be a distributive operator (5), similar to English each, citing (6) as evidence where dou forces a distributive reading.

When combined with a mei-NP, dou quantifies over the atomic parts of the maximal sum referred to by the mei-NP, and together they deliver (7) as the meaning of (2a), capturing its equivalence in meaning with the English universal statement every third-grade student came.

Since mei-NP’s are not quantificational, they need the aid of dou—a quantificational element—to express a quantificational meaning, and hence the co-occurrence is expected. Lin’s analysis is decompositional, in the sense that universal quantification is decomposed into maximization over NP and distributivity over VP. However, since maximization and distributivity are two independent operations, assigning mei-NPs a plural definite semantics (maximization) does not really explain why dou (distributivity) is needed: there is nothing in the semantics that prevents \(\oplus \textsc {third.grade.student}\) (of type e) from combining with \(\lambda x.\textsc {came}(x)\) (an et predicate). Lin is aware of the problem and offers a syntactic solution. Following Beghelli and Stowell (1997), he proposes that dou is the head of a Distributive Phrase (DistP), and universal DPs such as mei-NPs carry a Q feature and must move to Spec of DistP to check it. The syntactic requirement explains the mei-dou co-occurrence (see Lin 2020b for refinements).

This paper (focusing on mei-NPs) discusses two types of problems for this line of analysis. First, there is ample evidence that mei-NPs are genuine distributive universal quantifiers (see also Liu 2017b) and cannot be reduced to plural definites. Second, explaining the mei-dou co-occurrence as a syntactic-semantic requirement of mei is both too strong and too weak. It is too strong since many occurrences of mei-NPs in preverbal positions do not need (or even cannot have) dou (Huang 1996; Chen and Liu 2019; Liu 2019a), suggesting that the co-occurrence might not be the result of a strict grammatical requirement. It is also too weak because the phenomenon of obligatory-dou goes beyond mei-NPs: in suitable contexts, a conjunction of proper names also requires dou. Crucially, this illustrates that obligatory-dou is sensitive to discourse contexts, a fact overlooked in the previous literature.

A pragmatic explanation is offered. Mei-NPs are true universal quantifiers while dou is not. Dou is truth-conditionally vacuous but carries a presupposition that its prejacent is the strongest (in terms of likelihood or entailment) among its alternatives (Liu 2017b). The presupposition triggers Maximize Presupposition (MP, Heim 1991), which requires that [dou S] block its counterpart [S] without dou whenever dou’s presupposition is satisfied. This explains the obligatory presence of dou with mei in ordinary contexts, if we assume that mei-NPs are universal quantifiers triggering individual alternatives (cf. Zeijlstra 2017): since these alternatives are all weaker than the universal prejacent, dou’s presupposition is satisfied and the blocking of mei-dou over mei enforced by MP. Importantly, since the blocking effect does not rely on particular properties of mei, the proposal predicts that obligatory-dou is not restricted to universals. Finally, since what count as alternatives may be subject to contextual manipulation, there might be cases where the individual alternatives triggered by a mei-NP are irrelevant and thus missing for the evaluation of dou, and dou is expected to be absent. Overall, the proposal predicts a more nuanced distribution of obligatory-dou, not restricted to universal DPs and sensitive to discourse contexts.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 offers evidence that mei-NPs are not plural definites but similar to standard universal quantifiers like English every-NPs. This suggests that dou might not be an entity-level quantificational element. Section 3 presents the non-quantificational (over entities) analysis of dou in Liu (2017b), and highlights dou’s presuppositional contribution. Section 4 introduces Maximize Presupposition and demonstrates how it can be used to explain among a large array of obligatory presupposition effects the co-occurrence of mei-NPs with dou. It then shows how the explanation leads to the prediction that obligatory-dou is not limited to mei-NPs and sensitive to discourse contexts. Finally, Sect. 5 discusses some remaining issues.

2 Mei-NPs are quantificational

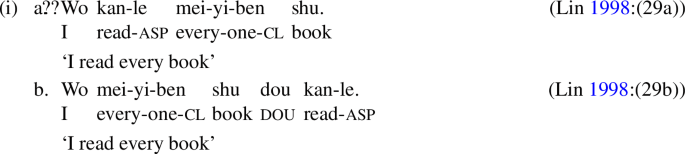

This section compares mei-NPs and plural definites, in view of the proposed equivalence between the two under Lin’s (1998) analysis. It shows, however, that regardless of whether dou is present (e.g. no dou for post-verbal mei-NPs), the two are significantly different.

2.1 Mei-NPs without dou in post-verbal positions

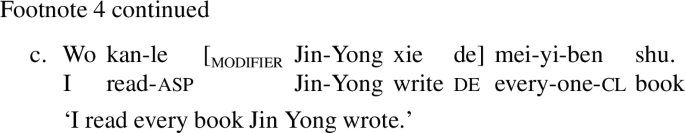

Post-verbal mei-NPs do not occur with douFootnote 4, presumably for the syntactic reason that dou is a VP-external adverb that associates only to its left (see Sect. 5 for relevant discussion). We can use this feature to test whether mei-NPs indeed have a plural-definites semantics as Lin (1998) proposes, by comparing mei-NPs and real plural definites (such as demonstrative phrases and plural pronouns in Mandarin) in this environment. Since dou is absent in both cases, if the two show divergences, they must be attributed to an inherent difference between the two, and may well suggest that mei-NPs cannot be reduced to plural definites.

2.1.1 Non-homogeneous and maximal

Consider (10a) first. Its most salient reading (and the only reading for most speakers) is \(\lnot >\forall \), and this shows that, under negation, a mei-NP without dou still retains its universal quantificational force. By contrast, plural definites such as the demonstrative phrase in (10b) are interpreted existentially under negation, due to a well-known property of plural definites—homogeneityFootnote 5 (Löbner 2000, a.o.). In other words, (10a) is true as long as there was a third-grade student to whom the speaker did not tell the news, while (10b) can only be true when the speaker told the news to none (\(\approx \) not any, any being existential) of the third-grade students.

The contrast clearly shows that mei-NPs are not plural definites. The fact that they lack homogeneity under negation and still retain their universal force even without dou suggests that they are universal quantifiers by themselves.

This contrast between every-NPs and plural definites is fully general. (11) exhibits distinct behaviors of the two under nobody. In a scenario where everyone will invite some but not all third-grade students, (11a) is true while (11b) is false.

(12) shows the same contrast: (12a) is interpreted as only scoping over universal while (12b) is interpreted as only scoping over existential. (12a) is true iff Lisi invited every third-grade student but others did not invite them all, while (12b) requires Lisi to invite some of the third-grade students while others didn’t invite any.

It is interesting to note in this connection that suoyou-NPs behave like mei-NPs: they do not exhibit homogeneity and retain their universal force in negative environments without dou as in (13a), unlike their demonstrative phrase and plural pronoun counterparts in (12b) and (13b). This suggests that suoyou-NPs cannot be treated as plural definites either.

Next, non-maximality is another property of predication with plural definites (Malamud 2012, a.o.). In a scenario where the speaker is pointing at all the contextually salient third-grade students and using zhe-xie san-nianjie xuesheng ‘these third-grade students’ to refer to them, (14b) can still be true if some of the third-grade students being referred to were not invited by Lisi. That is, predication with plural definites allows for exceptions. This is impossible for the mei/suoyou-NP in (14a). For (14a) to be true, Lisi had to invite every third-grade student in the context, without exceptions.

A reviewer reports that s/he and other two speakers find the non-maximal reading of (14b) unavailable. Note however that non-maximal readings are context-dependent (Krifka 1996; Malamud 2012) and one might need to look for suitable contexts to make them salient. Imagine a context where these third-grade students have tested positive for Covid-19, and the health department wants to find out who has been in contact with them. Lisi just heard the news and exclaims: “Damn! wo zuotian qing-le zhe-xie san-nianji xuesheng” ‘Yesterday I invited these third-grade students’. Lisi’s utterance is felicitous and true, even though he actually only invited 5 out of the 8 third-grade students. On the other hand, Lisi cannot use mei-yi-ge/suoyou san-nianji xuesheng in this case, illustrating again that they are always maximal, regardless of contexts. The contrast can also be demonstrated by considering the announcement made by the health department in this scenario: if you have contacted zhexie third-grade students, you need to report to us vs. if you have contacted mei-yi-ge/suoyou third-grade students,.... Only the former is an appropriate announcement. See (Xiang 2008: Sect. 4.1) for relevant discussion of non-maximal readings of Mandarin plural definites without dou.

To summarize, a comparison between mei-NPs and plural definites in post-verbal positions, where dou is absent, suggests the two are very different. A mei-NP does not exhibit homogeneity and non-maximality, two well-known properties of plural definites across languages, and it always retains its maximal universal force, in both positive and negative contexts, just like its English counterpart every-NP.

2.1.2 Quantifier-sensitive expressions

There are quantifier-sensitive expressions that require the presence of a quantificational element in their host sentence, for instance exceptives but/except (von Fintel 1993) and approximatives almost (Penka 2006), both of which have been used as tests for the quantificational force of a DP (Carlson 1981; Kadmon and Landman 1993). In (15), we see a standard universal quantifier is compatible with but/almost, but a plural definite is not, illustrating the ability of a Q-sensitive expression to distinguish the two.

Returning to Mandarin, (16a) shows post-verbal mei-NPs without dou are compatible with exceptives chule ‘except’ and (16b) shows they are fine with approximatives jihu ‘almost’. The two nevertheless reject plural definites, as (17) exhibits. An obvious explanation in view of (15) is that chule and jihu need the presence of a universal quantifier in the sentence, and mei-NPs – even in the absence of dou – contribute such a universal quantifier.

Similar to mei-NPs, suoyou-NPs without dou are also compatible with the two Q-sensitive expressions as in (18), suggesting they too are quantificational by themselves.

A reviewer points out that Q-sensitive expressions are fine with plural definites if dou is added, as in (19). This does not affect the conclusion based on (16)–(17) that mei-NPs are quantificational on their own and thus can license Q-sensitive expression in the absence of dou. (19), on the other hand, suggests that dou in combination with a plural definite contributes a quantificational element. This in fact supports the analysis of dou to be presented in Sect. 3: although dou is not an entity-level quantifier, its presence with a plural definite necessitates a covert distributivity operator (essentially a universal quantifier) at LF, and thus Q-sensitive expressions can be licensed.

The position of jihu ‘almost’ adds support to the above view. In the case of definite-dou, jihu needs to appear after the definite and immediately before dou, as in (19b). Putting it before the definite in (20a) is not allowed (Li 2014: (12a)). By contrast, for mei-dou, speakers strongly prefer to put jihu immediately before the mei-NP as in (20b). The contrast supports the view that mei-NPs, differing from plural definites, are true universals: assuming that jihu needs to precedes the universal it modifies, we predict its appearance before mei-NP, for the latter is the true universal quantifierFootnote 6. As for definite-dou, if we take the position of jihu as indicating the position of the underlying semantic \(\forall \), the contrast between (19b) and (20a) is expected under the account hinted at above, where the source of \(\forall \) comes from a covert distributivity operator adjacent to dou (to be discussed in detail in Sect. 3).

2.2 Mei-NPs with dou

As the discussion of mei-NPs without dou in the previous subsection has shown, mei-NPs are significantly different from plural definites, unexpected under the line of analysis following Lin (1998) that treats the two on a par. This subsection turns to mei-NPs with dou, which as we will see again, exhibit properties distinct from their plural definite counterparts.

2.2.1 Partitives

Since a plural definite is referential and denotes the maximal plural individual that satisfies the NP denotation, we can use a partitive construction to predicate over only a sub-part of its referent. (21) shows that an English plural definite is compatible with partitives, while an every-NP is not (see the Partitive Constraint in Jackendoff 1977). Without going into a detailed discussion of partitives (see Ladusaw 1982 for a proposal, among others), the point to note is that an every-NP, being a universal quantifier, is unable to provide the plural individual that is needed for a partitive construction.

Turning now to Mandarin, (22a-b) show that plural definites, even co-occurring with dou, are still compatible with partitivesFootnote 7, while mei-NPs never are. The contrast confirms that plural definites but not mei-NPs are referential sum-denoting expressions, suggesting the latter are in fact quantificational elements.

It is worth noting that suoyou-NPs also resist partitives as in (23). The contrast between (19) and (22a) and the parallel between (19) and (22b) indicates suoyou-NPs are also quantificational.

2.2.2 Scope

Now we turn to the scope facts discussed in Liu (2017b). Liu reports that in the case of mei-NPs, it is the surface position of the mei-NP—rather than dou—that determines the scope of the underlying semantic \(\forall \), and concludes that it must be the mei-NP that contributes the \(\forall \). The relevant facts are in (24). (24a) shows that in the case of mei-NPs with negation, to obtain a negation scoping over universal construe (\(\lnot >\forall \)), the negation needs to appear before the mei-NP, not just before dou as in (24b) (Huang 1995; Li 1997: 154; Shyu 2004: (21))Footnote 8.

Conversely, for plural definites with dou, a wide scope negation can be put either before or after the definite (but before dou), as in (25)Footnote 9.

The contrast between (24) and (25) can be better understood if the standard distinction between referential and quantificational terms is maintained in Mandarin, with plural definites being non-quantificational while mei-NPs are scope-taking universals. Since Mandarin is a highly scope-isomorphic language (Huang 1982), it is the surface position of the mei-NP that determines its semantic scope, and thus to obtain a \(\lnot >\forall \) construe, the negation needs to appear above the mei-NP.

Concretely, I assume with Li (1997); Lin (1998); Wu (1999); Constant and Gu (2010) and many others that dou heads a functional projection, requiring its associate to move from below dou to its specifier position, and further dislocation between dou and its associate can be achieved via topicalization of the latter (Lin 1998: 218; Constant and Gu 2010: fn. 2). Next, I assume that a topicalized associate needs to reconstruct to Spec-dou to get interpretedFootnote 10. The two assumptions, together with the General Condition on Scope Interpretation proposed in Huang (1982), offer an explanation why (24b) is ungrammatical while (25b) is not.

In (24b), the mei-NP is topicalized across negation and needs to reconstruct to Spec-dou for interpretation; this however violates (26), since at SS the mei-NP c-commands negation while at LF it is the other way around; consequently, (24b) is predicted to be bad. On the other hand, (25b) is predicted to be well-formed: a plural definite, being referential, can be reconstructed across negation without violating (26). Finally, (25a) is also expected to be fine, a nice result for the speakers who find (25a) grammatical (though see fn. 10).

The above explanation is supported by the following four types of facts. First, non-quantificational expressions (such as the proper name subject in (27)) generally do not incur intervention between a mei-NP and dou, as is illustrated by (27b). This is predicted, for reconstruction of a mei-NP across a non-quantificational element does not violate (26).

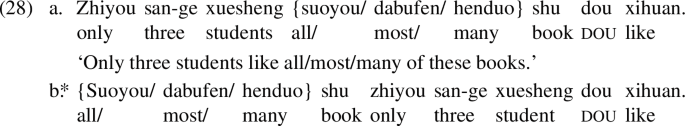

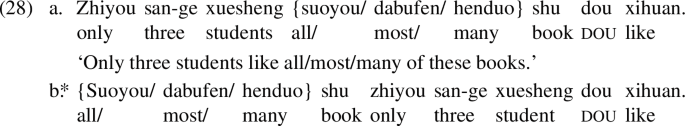

Second, similar to negation, other quantificational expressions (such as the only-phrase in (28)) cannot appear between dou and a mei-NP, for the same reason that negation causes intervention. Again, this contrasts with plural definites, illustrated by (29b) where zhiyou ‘only’ is fine between zhe-xie shu ‘these books’ and dou. This is again expected: since plural definites do not take scope, moving them around never violates (26).

Third, to have a mei-NP scope above another scope-bearing element at LF, the latter has to be positioned after dou, as in (30). This is predicted by the current story. Since a mei-NP always occupies Spec-dou at LF, anything scoping under it must be lower than the head.

Finally, the difference between mei-dou and definite-dou with respect to scope reveals a general distinction between quantificational and referential associates of dou (Li 2014). The expressions that are intuitively quantificational (in the sense that they correspond to English items that are standardly treated as quantificational) such as suoyou ‘all’, dabufen ‘most’, and henduo ‘many’ all pattern with mei. (31)-(32) show that when associated with dou, these items do not allow another Q-element between the two, suggesting that they are indeed quantificational. As for other types of associates, wh-items, renhe ‘any’ and minimizers behave like mei, while bare nouns (under both definite and generic readings) pattern with plural definites (examples not exhibited due to constraints of space). This is again expected under the assumptions that wh-items, renhe and minimizers are underlyingly existential quantifiers (Liao 2011; Liu 2019c; Xiang 2020), while bare nouns denote kinds and are referential (e.g. Chierchia 1998).

In view of the above facts, it seems incorrect to say that dou always determines scope (of the semantic \(\forall \)), as is usually assumed in the literature and predicted by Lin (1998). Instead, a more accurate description seems to be that “QPs in Chinese, even when they are paired with dou, are still scope-bearing elements, entering into scope relations with other elements, just as in other languages. At the same time, dou also bears scope” (Li 2014: 229). The above discussion on the scope of mei ‘every’ offers a concrete proposal as to how a QP and dou together determine scope: the QP is the real (entity-level) scope-bearer, but it needs to appear next to dou (at its specifier) at LF, and thus the surface position of dou plays a role in revealing the LF position of the QP. In combination with the scope-isomorphic property of the language, the account captures correct scopal behaviors of quantificational associates of dou.

2.2.3 Quantifier-internal anaphora

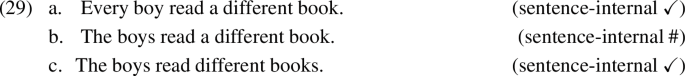

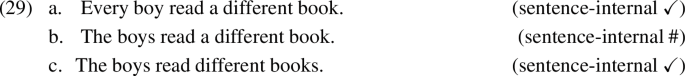

In English only genuine distributive universals license sentence-internal readings of singular different (Carlson 1987; Brasoveanu 2011; Bumford 2015). We observe in Mandarin these readings are easily found with mei-dou but are hard to obtain with definite-dou, and thus the former but not the latter make good candidates for true universals. Crucially, since dou is present in both cases and yet a difference is observed, we conclude it is the mei-NPs (but not dou) that contribute the true distributive universal force.

Consider English facts first. (34a) shows that every licenses sentence-internal readings of singular different, in the sense that the books that are being compared are all present within the sentence, in this case introduced by different boysFootnote 11. In contrast to every-NPs, plural definites do not license sentence-internal singular different, as in (34b). To get the sentence-internal reading, the NP that combines with different has to be plural, as in (34c).

The same pattern is found in Mandarin, between mei-dou and definite-dou. (36a), with mei-dou scoping over a (semantically) singular indefinite containing butong ‘different’ (singularity indicated by the numeral yi ‘one’ followed by a classifier), has a salient sentence-internal reading, under which for any two students a and b, a’s book is different from b’s. By contrast, it is hard (or even impossible) to get this reading for the corresponding (36b) with definite-dou; the most natural interpretation for (36b) is a sentence-external one where the students all bought a book different from the contextually salient one(s). To bring back the sentence-internal reading to salience, the numeral yi ‘one’ and the classifier need be removed to turn the different-DP into a semantically non-singular one, as in (36c)Footnote 12.

In view of the generalization exhibited by (34) that sentence-internal readings of singular different generally need licensing from a true distributive universal (see Brasoveanu 2011 for corpus data and cross-linguistic evidence), the contrast between (36a) and (36b) demonstrates that mei-dou, but not definite-dou, behaves more like genuine distributive universals. Since dou alone does not seem to have the full capacity of this licensing effect (or (36b) would have a salient sentence-internal reading), it is the mei that is the true universal.

Let me offer further evidence. First, adding a distributive expression such as gezi ‘each’ to (36b) is felicitous (Xiang 2020: (15)) and gives rise to a salient sentence-internal reading, as in (37a). In fact, simply replacing the dou in (36b) with ge ‘each’ has the same effect (see Lee et al. 2009 on ge). This is similar to English where overt distributivity operators such as each license sentence-internal singular different. The fact that dou alone (with plural definites) does not easily licence sentence-internal singular different while gezi/ge do (with or without dou) suggests again that the latter are distributivity operators while dou is not.

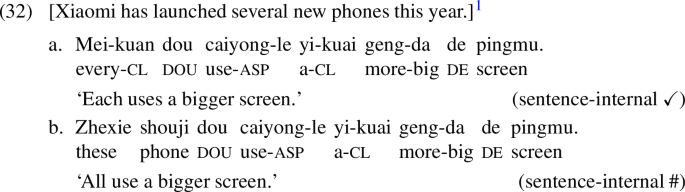

Second, sentence-internal readings of singular different involve quantifier/distributivity-internal anaphora, in the sense that the distributive universal could introduce two discourse referents within its nuclear scope (Brasoveanu 2011; Bumford 2015), the values of which are needed for the evaluation of a sentence-internal singular different. Internal interpretations of certain comparatives also belong to this category and are only permitted when under a distributive universal (Beck 2000; Brasoveanu 2011; Bumford 2015). This is again true in Mandarin. The next two examples illustrate that while mei-dou licenses internal readings of comparatives such as geng-da ‘bigger’ and xin ‘new’, the corresponding definite-dou does not.

The fact that mei-dou in general licenses quantifier/distributivity-internal anaphora while definite-dou does not, shows that the two, though they may have equivalent truth-conditions, involve different types of distributivity/quantification. Indeed, singular different according to Brasoveanu (2011) is a distributivity-dependent item and can be used to reveal the nature of the distributivity it is associated with. Without going into the technical details of modeling different varieties of distributivity/quantification (see Brasoveanu 2011 and Bumford 2015 for implementations in dynamic semantics), the contrast suggests that mei but not dou contributes the kind of universal quantification/distributivity English every conveys, and thus is the prime candidate for universal quantifier in Mandarin.

Summary A large array of facts have been discussed, all pointing to the conclusion that Mandarin mei-NPs are true universal quantifiers. The facts are summarized below.

With mei-NPs being quantificational, we need a non-quantificational (over-entities) story of dou to avoid the double quantification/requantification problem (Yuan 2012; Xu 2014; Wu and Zhou 2019). The next section introduces such an analysis of dou, based on Liu (2017b).

3 Non-quantificational dou (at the entity-level)

Mandarin dou draws a lot of attention in the literature (Lee 1986; Cheng 1995; Shyu 1995; Huang 1996; Lin 1998; Hole 2004; Pan 2006; Xiang 2008; Liao 2011; Yuan 2012; Xu 2014; Liu 2017b; Wu and Zhou 2019; Xiang 2020). The current paper, following recent development on the topic, takes dou to be an alternative sensitive operator (Liao 2011; Liu 2017b; Xiang 2020). Specifically, we take dou to be a strongest-prejacent operator as defined in (53a): it is truth-conditionally vacuous but carries a presupposition that its prejacent is the strongest among its contextually relevant alternatives (the C in (53a); cf. Karttunen and Peters’s (1979) analysis of English evenFootnote 14 and the idea of intensifier in Xu 2014; Wu and Zhou 2019.). Distinct ‘uses’ of dou are then analyzed by conceptualizing strength differently: even-dou corresponds to being the strongest in terms of likelihood (\(\prec _{likely}\)), while distributive-dou in terms of entailment (\(\subset \)). In the former case, dou presupposes that its prejacent is the most unlikely one in the context; in the latter case, dou requires its prejacent entail all the relevant alternativesFootnote 15.

To illustrate the analysis, consider two widely discussed uses of dou: its even-use in (43a), and its use as a distributivity operator similar to English each in (43b). The two uses correspond to two ways of understanding strength between propositions: (un)likelihood vs. entailment.

In (43a) with prosodic focus on Lisi, dou presupposes that the prejacent Lisi bought 5 books is less likely than all the other alternative propositions (such as Zhangsan bought 5 books), and this straightforwardly explains the observed even-flavorFootnote 16. (43b) with stress on dou involves setting strength to entailment, and dou presupposes that its prejacent entails all the other alternatives. Assume that the alternatives to the prejacent are Zhangsan bought 5 books and Lisi bought 5 books; the requirement can be satisfied only if the prejacent is understood distributively (Zhangsan and Lisi each bought 5 books \(\subset \) Zhangsan/Lisi bought 5 books). In other words, entailment-based dou forces distributive readings of plural predication (cf. Szabolcsi’s (2015: 181–182) explanation of the distributivity effect associated with mo-style particles), giving rise to the appearance that dou is a distributivity operatorFootnote 17.

Let me now turn to a question raised by a reviewer concerning this analysis of dou. The reviewer asks how scope is established in (44), and in general “how dou as a semantically vacuous item affects sentence meanings”. Note however dou is not semantically vacuous. It is truth-conditionally vacuous (vacuous in assertion), but has a semantic contribution at the level of presupposition. The presupposition often forces a sentence to be interpreted in specific ways to meet its requirement. Crucially, dou’s surface position indicates at which point the presupposition is evaluated (the scope of dou). Thus putting dou at different positions leads to distinct presuppositions, which may have truth-conditional repercussions.

Consider (44). In (44a) the scope of dou does not include negation and thus distributivity is forced below negation, giving rise to a \(\lnot >\forall \) interpretation. In (44a) negation is within the scope of dou, and as we will see immediately, the presuppositon can only be satisified with construing distributivity above negation (\(\forall > \lnot \)).

To implement the above idea, we need to be specific about how distributivity is forced by the presupposition of dou. I will assume that distributive readings are conveyed by a covert distributivity operator Dist (Liu 2017b), as in (45) (cf. the semantics of dou in Lin 1998).

The existence of covert Dist in Mandarin is evidenced by (46). As an answer to (46Q), (46A) (where no dou is present) is strongly preferred to be read distributively (Liu 2017b).

With Dist, the fact that entailment-based dou (associated with definites) forces distributive readings is equivalent to the requirement that dou forces a Dist within its scope.

Next, as Shyu (2018) observes, Mandarin dou on its even-interpretation ([lian...dou], see fn. 14), in contrast to English even, never scopes over a higher negative element. The difference is most clearly illustrated in (47). In (47a), even conveys that Syntactic Structures (SS) is an easy book to understand. This can be analyzed as even scoping over nobody at LF (see the scope theory in Karttunen and Peters 1979; cf. the lexical ambiguity theory in Rooth 1985), triggering the presupposition that it is less likely for nobody to understand SS than for nobody to understand any other book—equivalently, it is most likely for somebody to understand SS. This presupposition explains the perception that (47a) presents SS as an easy book. By contrast, the corresponding (47b) in Mandarin, in which mei-you ren—roughly ‘nobody’—appears above dou and its associate at the surface, does not have this reading. Instead, it conveys that SS is a hard book, which can only be obtained by interpreting dou under nobody. To obtain the easy-reading, nobody needs to appear within the surface scope of dou, as in (47c).

It is natural to assume that dou on its different readings shares the same scopal property. Consequently, the dou in (44a) also scopes below negation and has its presupposition evaluated there. The presupposition requires that the prejacent they got 100 points entail all other alternatives such as John got 100 points, and this can only be satisfied by inserting Dist to the VP below dou (and thus below \(\lnot \)). This explains the \(\lnot >\forall \) readingFootnote 18.

Finally consider (44b). Negation now appears below dou at the surface and thus the prejacent that dou evaluates includes negation. In other words, dou requires they didn’t get 100 points entail alternatives such as John didn’t get 100 points. This can only be met by inserting Dist below dou but above negation, and thus the \(\forall > \lnot \) reading is obtained.

To sum up, the above discussion illustrates how dou can be assigned a truth-conditionally vacuous meaning and yet still seems to incur truth-conditional effects and determine scope at the entity-level when associated with a plural definite. Crucially, the presupposition of dou can force a covert Dist within its scope, and it is the Dist that affects the truth-conditions (by contributing \(\forall \)). Since the surface position of dou determines where its presupposition is evaluated, it indicates where Dist is inserted and thus reveals the scope of \(\forall \).

Besides offering a conceptually simple way of understanding dou’s various uses, the present analysis brings together two prominent accounts of dou proposed in the literature: the distributivity operator approach that takes dou to be a distributivity operator similar to English each (Lin 1998; Chen 2008), and the maximality operator approach that takes dou to be \(\iota \) (or \(\sigma \) as in Sharvy 1980; Link 1983) that encodes maximality/uniqueness, similar to English definite article the (Giannakidou and Cheng 2006; Xiang 2008; Cheng 2009). Consider (48) (with stress on dou, see fn. 17), which illustrates both of dou’s maximality and distributivity effects. In (48), the bare numeral subject associated with dou is interpreted as a definite, indicated by the in the gloss (see Cheng and Sybesma 1999, (57b) and Constant and Gu 2010, (16) a.o. for the observation), and the VP following dou has a distributive construe marked by each in the gloss. Obviously, neither the distributivity operator approach (motivated by and thus only capturing each) nor the maximality operator approach (motivated by and thus only capturing the) accounts for the full range of dou’s effects exhibited in (48).

Taking the dou in (48) as an operator that evaluates strength at the level of propositions (based on entailment in this case) predicts both effects. As an entailment-based strongest-prejacent operator, dou presupposes that its prejacent (3 students bought five books, 3 being at least 3) entails all the other alternatives such as 2/1 students bought five books (recall that dou associates to its left and thus san ‘three’ triggers alternatives here). The entailment from the prejacent to the alternatives goes through only if the VP is interpreted distributively (3 students each bought five books \(\subset \) 2/1 students each bought five books), but not collectively/cumulatively. This explains the distributivity effect, in parallel with the explanation of (43b) discussed above.

Furthermore, for the prejacent of (48) to entail all the other alternatives, there have to be exactly three students in the context. This can be illustrated by comparing (49) and (50). With exactly three students in the context, propositions of the form n students each bought five books with \(n>3\) would be excluded from the relevant set of alternatives under discussion, for it makes no sense to consider a proposition like 4 students each bought five books if we already know there could only be three students. As a results the prejacent indeed entails all the other alternatives, as illustrated in (49). (50) is different. In this case, there are more than 3 students (say 4) in the context and thus there is a proposition (4 students each bought five books) in the alternative set (asymmetrically) entailing the prejacent; consequently, dou’s strongest-prejacent presupposition cannot be satisfied and the sentence is infelicitous in such a context. In other words, the analysis of dou in (53a) as a strongest-prejacent operator predicts (48) to carry a presupposition that there are exactly three students in the context, and this is exactly the maximality/definiteness effect.

In sum, taking dou to be a strongest-prejacent operator (based on likelihood or entailment, and in this particular case entailment) accounts for both distributivity and maximality of dou: the former is required to ensure entailment among alternatives while the latter is needed so that the prejacent can entail all the other alternatives (in schematic words, strongest = distributivity + maximality). In this sense, the current analysis inherits insights from both the distributivity operator analysis and the maximality operator analysisFootnote 19.

The paper adopts this analysis of dou as a strongest-prejacent operator. Since dou is non-quantificational at the entity-level, it is compatible with the facts presented in Sect. 2 that suggest the mei is the genuine universal quantifier in mei du

Before ending the section, I would like to emphasize that the contribution of dou is a presupposition, as presuppositions will turn out to be crucial in the explanation of the mei-dou co-occurrence. A well-known property of presuppositions is that they project. The following examples illustrate that the contribution of dou projects across polar questions, possibility modals, negation and conditional antecedents. In particular, all the sentences in (51) convey that Lisi is the least likely one to buy 5 books , while all the sentences in (52) (with stress on dou, see fn. 17) convey that there are exactly 3 students in the contextFootnote 20.

In sum, dou is truth-conditionally vacuous but carries a presupposition that its prejacent is the strongest among its contextually relevant alternatives. With this independently motivated semantics of dou, we now turn to an explanation of the mei-dou co-occurrence.

4 Obligatory dou as obligatory presupposition

Taking dou to be a presupposition trigger allows us to reduce obligatory dou to the general phenomena of obligatory presupposition (Amsili and Beyssade 2009), attested independently for a wide class of presupposition triggers across different languages. As we will see in this section, the new proposal predicts that obligatory dou is not limited to mei-dou and sensitive to discourse contexts.

4.1 Explaining mei-dou co-occurrence via obligatory presupposition

The effects of obligatory presupposition refer to the pragmatic phenomena where a class of presupposition triggers gives rise to obligatory presence when their presupposition is satisfied. Relevant examples discussed in the literature (Kaplan 1984; Heim 1991; Chemla 2008; Amsili and Beyssade 2009; Eckardt and Fränkel 2012, see also Bade 2016; Aravind and Hackl 2017) are offered in (53).

To illustrate, consider (53b). The trigger is again, which presupposes that the event described by its modified VP happened at a previous time. In (53b) it presupposes that the event of swimming by Mary happened before, and the requirement is locally satisfied by the first clause in (53b), and hence again is obligatory. Consider next (53d). Since the carries an extra uniqueness presupposition which is always satisfied by the world knowledge that there is one and exactly one sun, the presupposition trigger the is obligatory in (53d), and blocks the version of the sentence with a. Similarly, both blocks all in (53e) by its duality presupposition satisfied by the NP hands, and know blocks believe when its complement is already known to be true as in (53f), by its factive presupposition.

The same effects are observed in Mandarin, illustrated below from (54a) to (54f), to which the above remarks also apply.Footnote 21

Obligatory presupposition can be explained by the pragmatic principle Maximize Presupposition in (55), proposed in Heim (1991).

MP mandates that a speaker choose among sentences with identical assertive information the one that has more presuppositions, when the presuppositions are satisfied. Consider (53a). Here too is truth-conditionally vacuous but carries an additive presupposition that an alternative proposition to its prejacent is true; the presupposition is satisfied in its local context; thus MP favors [Bill went to the party too] over [Bill went to the party] where the two have the same assertion but the former has an extra presupposition, and too is obligatoryFootnote 22.

Returning to the puzzle of obligatory dou with mei, I propose that the co-occurrence of mei-NPs and dou is an instance of obligatory presupposition regulated by MP. Consider the universal sentence in (56a). We have established in Sect. 2 that mei-NPs are true universal quantifiers, so the prejacent of dou is a universal statement, as in (56b). Next, dou is truth-conditionally vacuous but presupposes that its prejacent is stronger than all the other contextually relevant alternatives. Suppose the alternatives to a universal statement are its individual instantiations, as in (56c) . Dou’s prejacent in this case entails all of its alternatives and its presupposition is automatically satisfied. MP is then triggered and requires [mei.ge student dou came] block its dou-less version [mei.ge student came], and dou is obligatory with mei as a result.

An important ingredient in the above explanation is the idea that mei-NPs activate individual alternatives. Let me elaborate on this assumption and make it a bit more precise. First, these individual alternatives actually belong to the type of domain alternatives of generalized quantifiers—alternative generalized quantifiers with (only) their domain of quantification different from (usually smaller than) the one in the prejacentFootnote 23. (57) spells out the domain alternatives of mei and the corresponding propositional alternatives of the sentence in (56a). Note that \(\forall x[x\in \{\textsc {a}\}\rightarrow \textsc {came}(x)]\) is just student A came in (56c), and (56c) in fact equivalent to (57c) if the former contains propositions involving plural individuals (\(\forall x[x\in \{\textsc {a,b}\}\rightarrow \textsc {came}(x)]\) is student a and b came).

Domain alternatives are usually associated with disjunctions and indefinites in the literature (Kratzer and Shimoyama 2002; Sauerland 2004; Katzir 2007). An influential line of thinking also argues that polarity items such as any are simply existential quantifiers obligatorily triggering domain alternatives (among other ones) (Krifka 1995; Chierchia 2013). Given existential quantifiers can trigger domain alternatives, it is a small step to extend the idea to universal quantifiers (see e.g. the formal definitions in Chierchia 2013: 138; Xiang 2020: (25)). Indeed, Zeijlstra (2017), based on some of the positive polarity properties of Dutch iedereen ‘everybody’ (it can appear under negation, but cannot reconstruct below negation once it is above it at the surface, unlike English everybody), claims that it is a universal quantifier that obligatorily triggers domain alternatives.

The idea that universal quantifiers trigger domain alternatives is in fact hard to avoid in the structure-based theory of alternatives (Katzir 2007; Fox and Katzir 2011). In this theory, alternatives of an expressions can be formally defined, as in (58). Assuming the domain argument D is a syntactic variable at LF (von Fintel 1994), whose interpretation depends on the index of the variable, the domain alternatives of a quantifier are simply transformed from the quantifier by replacing the index of the domain variable with other indices.

We adopt Katzir’s (2007) general view of how formal alternatives are generated. Furthermore, to capture the fact that alternatives are also contextually constrained, we assume following (Fox and Katzir 2011), and Katzir (2014) that the set of alternatives eventually operated by an alternative sensitive operator is the intersection of both the set of formally determined alternatives ALT(\(\phi \)) and a second set of alternatives C that represents contextual relevance (cf. the idea behind C in Rooth 1992). This is explicitly stated for dou in (59).

Consequently, for cases of mei-NPs that require the presence of dou, such as (56), the individual alternatives are both formally defined (in \(\{\llbracket S' \rrbracket \mid S'\in \text {ALT}(S)\}\)) and contextually relevant (in C). This seems natural given that contextually relevant alternatives are usually taken to represent the current Question Under Discussion (QUD in Roberts 2012; Büring 2003), and an immediate QUD for a universal statement is whether the universal statement is true (the least subject matter in Lewis 1988), which in turn is reduced to the question of whether each individual instantiation is true. Intuitively, to evaluate the truth of a universal statement such as the one in (56), each individual alternative needs to be checked. It is in this sense that the individual alternatives of (56) are relevant.

To summarize, we have shown that the individual alternatives we posit for mei-NPs belong to the domain alternatives of generalized quantifiers and are commonly assumed for various purposes in recent literature. Building on Katzir (2007) and Fox and Katzir (2011), we have distinguished formal alternatives and contextually relevant ones, and propose that dou makes reference to their intersection. The distinction is useful, since it predicts that when the individual alternatives triggered by the mei-NP are not relevant, dou is not needed (for the intersection would be a singleton set with no non-trivial alternatives for dou to operate on). The next subsection shows that this is a correct prediction.

4.2 A more nuanced characterization of obligatory-dou

4.2.1 Irrelevance of individual alternatives and dou’s absence

Mei-NPs sometimes do not need dou, and this could happen when the individual alternatives of a mei-NP are contextually irrelevant. Consider the discourse in (60). We find a sharp contrast between the two occurrences of the same mei-sentence. When mei-ben mai $10 ‘every-cl sells-for $10’ is first uttered in (60), dou is not needed (and, in fact, better not to appear), while in its second occurrence dou is obligatory. This suggests that the mei-dou co-occurrence is sensitive to discourse contexts—an aspect of the phenomenon overlooked by the previous literature.

Contexts can affect dou’s presence in the current analysis, by manipulating the QUD that determines the shape of C needed for the interpretation of dou. Concretely, in (60a) when the owner first uttered mei-ben mai $10, her focus was on $10 (indicated by the stress perceived on shi ‘ten’), and it is naturally understood that she, as the owner of the bookstore, was assuming that every book was sold at the same price and the QUD is how much IS a book?. In such a context, the individual books are intuitively not relevant to the QUD, and do not figure in C. As a result, the set of alternatives evaluated by dou if dou were present (the intersection of the formal alternatives triggered by mei-NP and C) would be the singleton set that only contains dou’s prejacent. Assuming that dou, like other alternative sensitive operators, needs to be associated with a non-singleton set of alternatives (see the non-vacuity presupposition of dou in Xiang 2020), its absence here is correctly predicted.

By asking about a particular book in (60b), John shifted the QUD to which books are $10?. In the new context, individual books are clearly relevant (this comic book sells for $10 for instance is simply a member of the Hamblin denotation of the new QUD), and the C now contains propositions of the form x sells for $10. As a result, the intersection of the formal alternatives and C is just the set of salient individual instantiations of the universal statement. Since all the alternatives in this set are entailed by the universal prejacent, dou’s presupposition is satisfied and its obligatory presence required by MP in (60c).

It might be worth comparing the current view with Huang’s (1996) influential generalization regarding optional-dou, according to which an indefinite noun phrase within the scope of a mei-NP renders dou optional. The generalization however is inaccurate in view of (60): the same mei-ben mai $10, which arguably has an indefinite object, cannot take dou in its first occurrence but requires it in the second; that is, in neither case is dou optional.

Consider next (61), based on which (among other similar examples) Huang (1996) forms her generalization. In (61), an indefinite object appears under the mei-NP, and according to Huang’s judgement dou is not needed in the sentence, supporting the generalization.

It turns out however that sentences like (61) need extra contextual support. This is clearly stated in Cheng (2009: 62) “It should be noted that native speakers tend to consider the variant without dou incomplete (and should be preceded by statements such as ‘our restaurant has a policy’)”. While Cheng (2009) does not explain why contextual support is necessary, contexts obviously play a key role in the pragmatic explanation. To sharpen the intuition, consider some other contexts where (61) sounds natural. For example, (61) can be used in a context where the speaker is calculating the total number of dishes, and she either assumes every chef will make the same number as in (62a), or just ignores the differences between individual chefs, as in (62b) with pingjun ‘on average’. (61) can also be used as a command to the entire group of chefs (without paying attention to the individual ones) in an imperative (62c) (similar to the restaurant-policy context offered by Cheng (2009)). In all these cases, the intuition seems to be that the idiosyncrasies between chefs are ignored. According to the account of (60) above, this means the individual alternatives of the mei-NP are not in C and dou is hence not present.

Another significant fact is that contexts can also force dou to be present in cases like (61). Specifically, we can construct a context where individual chefs are clearly relevant, and dou is then predicted to be obligatory by the pragmatic account. This seems a correct prediction. Consider (63). Both questions explicitly ask about individual chefs, and answering either of them with (61) requires dou. This is unexpected for proposals that try to explain the mei-dou co-occurrence in terms of certain syntactic-semantic requirements of mei, which can be satisfied either by dou or by an indefinite within the VP (Huang 1996,Lin 2020b).

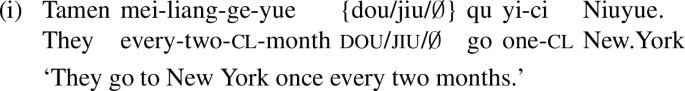

That irrelevance of individual alternatives can lead to dou’s absence is further supported by the observation reported in Liu (2019a) that mei-NPs with a classifier that describes a standard unit of measurement (e.g. mi ‘meter’, sheng ‘litter’, ...) usually do not appear with dou. Examples are in (64). Here again, individual alternatives are intuitively not relevant—in typical scenarios where rice is sold in big bags, a particular 500-gram bag of rice is no different from another 500-gram bag of rice in terms of its price, and thus the set of alternatives operated by dou would only contain the prejacent. Consequently, dou’s presupposition is not met and it is absentFootnote 24.

4.2.2 Over-generation?

A reviewer worries that the pragmatic account might over-generate, and offers (65) as a challenge. According to the reviewer, (65) is (categorically) ungrammatical; in other words, it should always be ill-formed, regardless of what context it is in. In particular, simply putting “a focus on gui..., intending that every book has the same property and that the individual price of books is not what the speaker cares about” does not save (65). The reviewer then asks: “what then determines the difference between this example and (60a)? Is the difference grammatical or pragmatic?”.

The reviewer is correct that simply adding a focus somewhere within the VP often does not make dou optional with mei. On the other hand, one of the main points of the paper is to suggest that a purely grammatical view to the mei-dou occurrence is inadequate. I now offer examples involving (65) to show that discourse contexts can indeed help improve the sentence, and manipulate the presence of dou in a similar way as they do in (60). Consider (66) and (67). Both contain [mei-ben (shu) hen gui] without dou and sound natural to me and my informants, unexpected on a purely syntactic-semantic viewFootnote 25.

From the pragmatic perspective proposed in the paper, (66)-(67) are easy to understand. (66) indicates a context where the bookstore is under discussion and prices of the individual books not so relevant. This context can be modeled as having a QUD (C) for the last clause that does not involve individual alternatives of mei-ben shu. Dou is then predicted to be absent. (67) is similar. Here the matrix zhi “only” is associated with hen gui\(_F\) “expensive” (or with the entire embedded clause with \(_F\)). Again, the focus particle and its associated focus reveal that the QUD is not about the individual books, and thus dou can be absent.

Just as in (60)/(63), dou’s obligatory presence can be brought back by contexts. Imagine that the owner of the bookstore overheard you uttering (67) or (68) to your friend. She asked (68Q) unpleasantly. Now you can respond with (68A). Crucially, dou is obligatory, as the owner activates the relevance of individual books with an explicit question.

The parallel between (60) and (66)–(68) suggests my answer to the reviewer’s question: there is no fundamental difference between [mei-ben shu hen gui] and [mei-ben shu mai $10]. Dou’s presence in both cases can be manipulated by discourse contexts, specifically by the QUDs, which are reflected by focus and focus particles.

That focus and focus particles could in general affect the presence of dou is reported in Li (2014). Li offers (69) to show that the focus marker shi ‘be’ can make dou optional. Let me add (70). In (70a) dou is required, but adding zhi ‘only’ in (70a) obviates the requirement.

From the pragmatic perspective, (69)–(70) are no different from (66)–(67). In all these cases there is no indefinite in the VP (recall Huang’s (1996) generalization) and yet focus/focus particles could manipulate the presence of dou. The fact that the mei-dou co-occurrence is sensitive to focus/focus particles and ultimately to the underlying QUD, supports the pragmatic analysis. Under the current proposal, an additional focus particle and its associated focus could indicate contextually salient alternatives other than the individual ones formally triggered by the mei-NP. These alternatives (strictly speaking their intersection with the individual alternatives) do not necessarily satisfy dou’s presupposition and thus dou can be absent. In (70b) for instance, the focus associated with only is the modifier, indicating a contextually salient set of alternatives {every student who did the homework got a high score, every student who didn’t do the homework got a high score}. Dou’s presupposition clearly is not satisfied with this set and thus does not appear in (70b).

Let me make two final remarks. First, in (66), (67), (69) and (70b), dou can be added back. This is compatible with the pragmatic analysis, as there could be multiple QUDs in a particular context and QUDs can have complex structures (Büring 2003). In a context where the main point of the discussion is not about the individual alternatives of the mei-NP, dou can be truly optional and its presence depends on whether the speaker treats the question concerning these individual alternatives as an additional sub-question.

Second, there is also a difference between [mei-ben shu hen gui] and [mei-ben shu mai $10]. Specifically, in the second case a plain focus is sufficient to make dou disappear while an additional focus particle is needed for the first. I would like to suggest that the difference is due to (i) the fact that there is a numeral in the VP in the second case, and numerals can easily attract focus and become the main point of discussion, and (ii) the world knowledge that things can be sold in kilos/meters/pieces, with one kilo/meter/piece not different from another with respect to the price. Thus it is easier for the second to have a dou-less mei.

I admit the current paper is unable to offer an explicit theory of relevance that can construct, combining different factors (focus, focus particles, features of discourse and world knowledge), an explicit Roberts-style discourse structure for every mei-sentence. The best the paper can do (as is done) is to add a syntactic variable C whose value is contextually determined and depends on the QUD. Despite this vague aspect, the proposal makes two clear predictions. First, a connection between focus/focus particles and mei-dou co-occurrence is predicted. Second, when it is clear that the individual alternatives of the mei-NP are relevant, as in (60b-c), (63) and (68) where an explicit question is asked about these individuals, dou is obligatory. Both predictions can be empirically tested, and as far as I can tell, are correct.

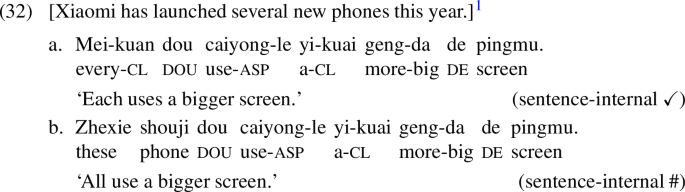

4.2.3 Obligatory dou with conjunction

The pragmatic account also predicts that the phenomenon of obligatory dou goes beyond mei-NPs and other universals, because obligatory dou is not explained by some unique properties of Mandarin universal noun phrases, but via satisfaction of dou’s presupposition and the general pragmatic principle MP. As long as the relevant set of alternatives satisfies dou’s presupposition, MP will enforce the presence of dou.

Consider (72). Since smile is an inherently distributive predicate (a and b smiled iff a smiled and b smiled), (72a) and (72b) would be equivalent in meaning if the contribution of dou is just truth-conditional. The two, however, sound different. In particular, to answer the question in (71a), (72a) but not (72b) can be used. In other words, when (72a) is used as an answer to (71a), dou is obligatory and we have an instance of obligatory dou with conjunction.

The current account straightforwardly explains the obligatory dou in (72a) as an answer to (71a). The wh-question in (71a) explicitly establishes Zhangsan smiled and Lisi smiled as the only two relevant alternatives. Since Zhangsan and Lisi smiled entails both, the presupposition of dou is satisfied, and MP requires the obligatory presence of dou.

Interestingly, to answer the question in (71b), (72b) can be used. This is again predicted. Since in the new context with three relevant individuals, not every alternative is entailed by Zhangsan and Lisi smiled (consider Wangwu smiled), dou’s presupposition is not satisfied, and it is predicted to be absentFootnote 26.

A reviewer asks how the account handles answers to polar questions like (73). According to the reviewer’s judgment, both (72a) and (72b) are fine as answers to (73).

That (72b) is a felicitous answer to (73) follows naturally from the current account. The polar question establishes {ZS and LS smiled, ZS and LS didn’t smile} as the QUDFootnote 27. With the prejacent being ZS and LS smiled, dou’s presupposition cannot be non-trivially met with this QUD (or its intersection with any set), and its absence is thus explained. Meanwhile, that (72a) can answer (73) can be explained by assuming that in this case a new question exactly who among the two smiled? is accommodated and (72a) targets the new QUD.

5 Conclusion and remaining issues

The paper has defended the view that mei-NPs are true universal quantifiers while dou is not, based on a large array of novel facts. Dou is truth-conditionally vacuous but carries a presupposition that its prejacent is the strongest among its alternatives. A pragmatic explanation of the mei-dou co-occurrence has been offered: in most contexts where a mei-NP is used, its individual alternatives are relevant, and thus the universal prejacent entails all the other alternatives and dou’s strongest-prejacent-presupposition is satisfied; Maximize Presupposition then mandates that a speaker choose mei-dou instead of mei without dou, for the former carries more presuppositions. As we have seen, the proposal predicts a more nuanced picture of obligatory-dou, beyond mei-NPs and sensitive to discourse contexts.

There are many open issues within this pragmatic account that remain to be explored. In this section I will mention two.

Other quantificational DPs Two reviewers ask about DPs other than universals. This subsection sketches how to extend the account to dabufen ‘most’, henduo ‘many’, yixie ‘some’, henshao ‘few’ and “negative quantifiers”. I take the basic pattern to be: while the former two optionally occur with douFootnote 28, the latter three and dou are incompatible (Chen 2008: Sect. 2.1).

The fact that dabufen ‘most’ can optionally co-occur with dou is compatible with the current proposal. Assume that the alternatives of dabufen are its scale-mates on a Horn scale \(\langle \)yixie, henduo, dabufen, quanbu/suoyou\( \rangle \) ‘\(\langle \)some, many, most, all\( \rangle \)’ (see fn. 23 on scalar alternatives). Dabufen is possible with dou if the more informative quanbu is not relevant (not in C), or to use Chierchia’s (2013) term, the scale is “truncated” to \(\langle \)yixie, henduo, dabufen\( \rangle \). This is plausible given Ariel’s (2004) conclusion based on a corpus study of English most that “it is a rare case that the difference between a strong but nonmaximal expression (such as most) and a maximal one (all) matters for the current purposes of the exchange” (Ariel 2004: 668).

Henduo ‘many’ can be analyzed in a similar manner. There could be contexts where the difference between henduo and dabufen/quanbu is not relevant. Henduo then becomes the most informative one on the scale and is predicted to be compatible with dou.

Yixie ‘some’ is different. As the bottom of its (positive) Horn scale, yixie can never become the top element unless all of its scale-mates are truncated, which however would violate the non-vacuity constraint that requires an alternative set to be a non-singleton (Xiang 2020). It is thus correctly predicted yixie is incompatible with dou.

Neither is henshao ‘few’ compatible with dou (Liu 1997; Chen 2008). On the assumption that \(\langle \)few, no\(\rangle \) form a (negative) Horn scale (Horn 1989) and no is more informative than few, Henshao, just like yixie, does not have a chance of occupying the top element of a non-trivial scale, and thus is predicted to be incompatible with dou.

Next, consider “negative quantifiers”. Given that (74a) and (75) below are unacceptable, one may conclude that they are incompatible with dou and thus a problem for the current account (for a negative statement entails all its subdomain alternatives). However, it is very likely that mei-you ‘not-have’ does not form a full-fledged negative DP with its adjacent NP. Indeed, Huang (2003), based on the fact that mei-you-NPs do not appear post-verbally in (76a) or as the object of a preposition, proposes that mei-you is a head in the TP domain (say the head of NegP) and Mandarin “negative quantifiers” are syntactically derived from an underlying [mei-you ...renhe-NP] string ‘not...any-NP’ under adjacency. Specifically, when the renhe-NP appears pre-verbally, it is adjacent to mei-you and the two can conflate (or be reanalyzed) into mei-you-NP by a local rule, as indicated in (76b).

Under this view, (75) can be explained by assuming that (i) when dou is merged into the sentence, it needs to appear above mei-you (see Sect. 3 on the scope of dou), and (ii) the renhe-NP, being dou’s associate, has to move to its left (Lin 1998, a.o.). After movement however, the renhe-NP is not adjacent to mei-you, no conflation happens and renhe has to be pronounced, as in (76c), which is indeed grammatical. In short, dou is incompatible with “negative quantifiers”, for there is no genuine negative quantifier in Mandarin.

Finally, a reviewer asks about the difference between henduo/dabufen on the one hand and mei on the other. Specifically, the reviewer wonders why dou is completely optional in (77a) but somehow required in (77b) (examples and judgment from the reviewer).

Let me first point out that a distinction is already made between the two in the current account. While additional contextual restrictions are needed for dou’s absence in the case of mei (by pruning the individual alternatives), they are responsible for dou’s presence with henduo/dabufen (by pruning the more informative alternatives). It is not implausible to assume that contextual manipulations of the second kind are more natural and frequent than the first, for speakers tend to care more about the individual instantiations when a universal statement is uttered. Consequently, in natural contexts, mei always co-occurs with dou but for henduo/dabufen it is entirely optional, depending on whether the speaker takes the more informative alternatives as relevant. Finally, there is also the possibility that there are syntactic features (strong or weak) in the grammar that regulate whether an expression obligatorily triggers alternatives (Chierchia 2013); mei but not henduo/dabufen could bear one such strong feature (cf. the strong Q-feature in Lin 1998). I leave this option open.

Summing up, the current proposal, together with some reasonable assumptions, predicts that dou is compatible with dabufen and henduo, and incompatible with yixie, henshao and mei-you-NPsFootnote 29. I think these are all welcome results. Meanwhile, let me emphasize that the above discussion is only preliminary and “quantifiers need to be approached on a case by case basis” (Nouwen 2010). The interested reader is referred to Lin (2020a) for a recent discussion of the interaction between dou and different quantificational DPs.

Object mei Mei-NPs in object positions do not occur with dou. This is compatible with our proposal. For syntactic reasons, dou only associates with items to its left and thus (78b) is syntactically ill-formed. Consequently, (78b) cannot block (78a) via MP (competition and blocking only happens between grammatical sentences), even if the every-NP in (78a) could trigger individual alternatives. This is very different from the case of pre-verbal mei-NPs, where both [mei-NP dou VP] and [mei-NP VP] are grammatical (the latter indeed surface in special contexts), and the former could block the latter via MP in ordinary contexts.

A reviewer then wonders what happens to the individual alternatives of an object mei-NP. I will assume that they are still activates but are taken care of by one of the many covert alternative sensitive operators proposed in the literature, e.g. Chierchia’s O or Rooth’s \(\sim \). I leave the options open but would like to point out adding these operators does not affect pre-verbal mei-NPs, as [mei-NP dou VP] contains more presuppositions than the version with O/\(\sim \), and thus MP still favors the sentence with dou.

Notes

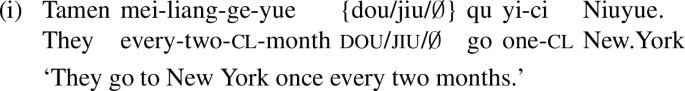

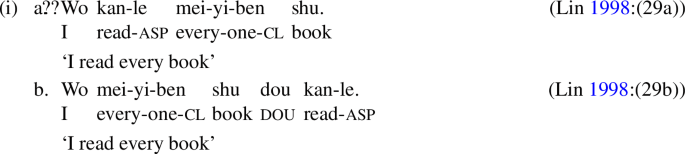

Two notes on mei-NPs. First, a classifier such as the ge in (2a) is required between mei and the NP. This paper discusses the meaning of mei-NP as a whole and ignores its internal composition and the role of the classifier. Correspondingly, mei ge xuesheng ‘every cl student’ is presented and glossed as mei-ge xuesheng ‘every student’, following Lin (1998). Second, numerals can appear between mei and the classifier. If the numeral is yi ‘one’, it is optional: mei-yi-ge san-nianji xuesheng can be substituted for mei-ge san-nianji xuesheng in (2a) with no discernible semantic effect. With numerals other than yi, a reviewer notes that the resulting mei-NPs might have restricted distribution (often used as non-arguments) and seem immune to the mei-dou requirement—in (i), dou is optional and using another focus particle jiu is also fine. This paper focuses on mei-NPs with yi ‘one’ and leaves to another occasion extending the proposed account to cases like (i). See also Solt (2009: 263–266) on every-n.

The entry of mei in (4b) looks different from the one in Lin (1998), since Lin uses sets to model plural individuals while this paper following more recent literature uses sums.

The current paper focuses on mei ‘every’. A detailed discussion of other universal determiners such as suoyou (similar to English all) and a comparison between them is left to another occasion.

Lin (1998) seems to take sentences with post-verbal mei-NPs as degraded, indicated by the “??” he assigns to sentences like (ia) (see Cheng 2009 for similar judgement). Thus post-verbal mei-NPs for Lin are required to move out of the VP with dou inserted, as in (ib). Indeed, my consultants agree that (ia)—while not entirely ungrammatical (Lee 1986: 105)—is less natural than (ib). However, if the mei-NP is modified or simply prosodically heavy as in (ic), it becomes perfect in post-verbal positions. In this paper, all the post-verbal mei-NP such as mei-yi-ge san-nianji xuesheng ‘every third-grade student’, are modified or prosodically heavy.

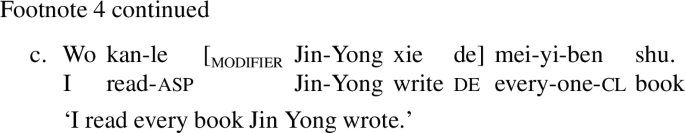

Homogeneity refers precisely to this property of plural definites: they give rise to (quasi)-universal force in affirmative sentences but receive existential interpretation in the scope of negation, as the contrast between (ia) and (ib) shows. Crucially, the reading of (ib) is not the result of a wide scope plural definite interpreted as \(\forall \) over \(\lnot \), since the same reading obtains in (ic) when the plural definite contains a bound variable and thus cannot take wide scope. See Križ and Spector (2020); Bar-Lev (2020) for recent proposals.

Some consultants, while agreeing that (20b) is better than (20c), still accept (20c). This can be explained by assuming the mei-NP in (20c) moves from somewhere adjacent to dou to its surface position, and that jihu modifies the mei-NP before it moves and thus is left behind. See the discussion on the scope of mei below.

While henduo and daduo are treated as quantificational adverbs in Liu (2017b), they are taken to be part of a partitive construction here, roughly [\(_{\text {NP}}\) tamen (zhong) henduo] ‘many among them’. Let me offer two pieces of evidence for the current view. First, henduo/daduo behave more or less like English Q-adjective many. In particular, they combine with nouns to form noun phrases (e.g. henduo/daduo xuesheng ‘many students’), and thus do not seem adverbial. Second, unlike real quantificational adverbs such a tongchang ‘usually’, henduo/daduo cannot bind singular indefinites: a quadratic equation tongchang/\(*\)henduo/\(*\)daduo has 2 solutions. A detailed syntax and semantics of henduo/daduo has to be left to another occasion (see Jin 2018 on Mandarin partitive constructions). But regardless of how these expressions are analyzed, the contrast between (22a) and (22b) clearly demonstrates that mei-NPs are distinct from plural definites, even with dou present for both.

Li (2014) claims that mei and dou can be intervened by sentential negation bu(-shi) (Li 2014: 225; fn. 21). However, the examples she offers (Li 2014: (44a), (54)) all involve rhetorical questions. It is currently unclear to me why negation is good between mei and dou in rhetorical questions, and I set this use of negation aside.

Some speakers I consulted prefer (25b) over (25a), and for them, (25a) has only a negated cleft interpretation, such as ‘it’s not these students that all like Jin Yong’. On the other hand, one reviewer finds (25a) grammatical with an ordinary wide-scope negation reading. The explanation to be given in the text below is fully compatible with the reviewer’s judgement, and the preference some speakers have can be treated as a preference for topicalizing a plural definite across negation (see below for discussion), presumably because Mandarin is a topic-prominent language and negation does not make a good topic. Finally, let me point out that the status of (25a) is not crucial to our purpose at hand, as the distinction between mei-NPs and plural definites is already established by the contrast between (24b) and (25b).

This can be derived from the requirement that dou (and alternative sensitive operators in general) needs to scope over its associate, (implicitly) assumed by several recent alternative-based analyses of dou, including this paper (Liao 2011; Liu 2017b; Xiang 2020). In particular, reconstruction to Spec-dou amounts to scoping below dou if we adopt a two-place semantics of dou (fn. 15; Liu 2019c, cf. Wagner 2006) and use movement—specifically, to the specifier of the operator (Drubig 1994)—for focus/alternative-association. Let me also mention that this association-from-Spec-dou idea represents one of the several attempts within the alternative-based approaches to reconcile the assumption that dou needs to scope over its associate and the fact that the latter actually appears above dou at the surface. Other means proposed so far include movement of dou (Liu 2017b) and positing covert even at a higher position (Liao 2011). Xiang 2020 uses reconstruction below dou to handle minimizers but is not explicit about how the other LFs (where dou clearly scopes over its associates) are derived. The idea presented here can be seen as generalizing Xiang’s reconstruction proposal to all types of dou’s associates (in a restricted way, in the sense that the associate does not always reconstruct to its base position). More work is needed to decide between these different syntactic implementations.

Compare (34a) with (i) below, which involves a sentence-external different: the other book needed for evaluation of different is external to its host sentence; that is, The Raven.

While some speakers accept the sentence-internal reading of (36b), they all agree that under the relevant reading the sentence is less natural than (36a) and (36c). In addition, roughly half of my consultants (7 out of 13) find the internal reading of (36b) entirely impossible. There are also examples such as (i) below where the internal reading is absent for everyone. The judgement given in (36b) reflects this variation between speakers and examples. Overall, the claim is that there is indeed a contrast between mei-dou and definite-dou with respect to their ability to license sentence-internal readings of singular different.

Some speakers find it difficult to get the relevant internal readings without an explicit bi-phrase (‘than’-phrase); in other words, they prefer (i) over (38a). This does not affect the point we are making here, since adding the same bi-phrase to (38b) still does not activate the internal reading.

Let me clarify that dou is not English even, which according to Karttunen and Peters (1979) presupposes that its prejacent is the most unlikely proposition among its alternatives. Dou is more abstract. It presupposes that its prejacent is the strongest among its alternatives, with strength unspecified (Liu 2017a). When dou expresses a even reading, an additional particle lian is often used to form the [lian...dou] construction (lian is always optional). We can think of lian as a marker for strength based on likelihood; in other words, in [lian...dou], dou requires its prejacent to be the strongest, and lian indicates that the strength is based on likelihood. Together, they form the presupposition that the prejacent of [lian...dou] is the most unlikely one among its alternatives.

Here is the two-place semantics of dou mentioned in fn. 10: \(\llbracket \text {dou } \rrbracket \)=\(\lambda B\lambda F\lambda w: \forall F'\in C[B(F)\subseteq B(F') ].B_w(F)\), where F is the denotation of dou’s associate and B the denotation of the rest (Liu 2019c).

It is worth mentioning at this point, as suggested by a reviewer, a line of analysis that assigns an existential presupposition to even-like particles (e.g. Kay 1990; Xiang 2020). According to Xiang 2020, the dou in (43a) conveys that Lisi is less likely than some contextually salient individual to buy 5 books. Due to constraints of space, I have to assume without argument a universal presupposition, simply following (i) previous researchers on [lian...dou] that it presents a sentence as the extreme/least likely case (see Yuan 2012: chapter 7 and references cited there), and (ii) the common wisdom that dou is somehow related to universality.

To clarify, (43b) is ambiguous. It can also mean ZS and LS together bought 5 books, which is unlikely. This reading can be captured by setting strength to likelihood and comparing the prejacent ZS and LS (as a group) bought 5 books with alternatives like ZS, LS and John as a group bought 5 books. A similar ambiguity exists in (48) below (with the additional reading being ‘a group of 3 students bought 5 books, which is unlikely’) and the same story applies there. Finally, as hinted in the text, stress (indicated by CAPITAL letters when necessary) can disambiguate. Entailment-based dou in association with a definite is often stressed (though not always, see fn. 26), while for even-dou stress always falls on dou’s associate. The prosodic pattern has been observed for a long time and yet no concrete proposal is currently available.

Other examples with embedded dou, about which the same reviewer wonders, can be analyzed analogously. In general, the surface position of dou determines where its presupposition is evaluated. See fn. 10 on how the associate of dou gets evaluated within its scope.