Abstract

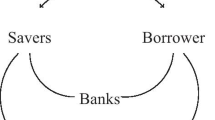

Survey evidence regularly shows that bank customers view bankers as less ethical or honest than other professions. This article sheds light on one potential origin of these misgivings that has been until now unaddressed. The legal system endows certain rights to banks without altering the duties obliged of depositors. By categorizing rights according to their corresponding duties we show that a conflict exists between: (1) depositors with an on-demand right to their deposited sum, and (2) depositories (banks) that are given the legal right to make use of these deposited funds at any time. Using a legal-economic analysis, we demonstrate that the latter right held by the bank is misplaced. Rectifying this erroneous assignment of rights removes the conflict apparent in the contract. Clarifying banking rights also aids in avoiding many of the misunderstandings seemingly inherent in the banking industry. Addressing this legal inconsistency removes one source of ire directed at bankers during banking crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Stöckl [41] offers a different explanation for the experiment’s results. Bankers do not behave dishonestly per se, but rather in accordance with the professional requirements of the banking industry. This interpretation raises the further question of why the professional requirements of the banking industry would promote behavior viewed by outsiders as ethically deficient, while few other industries seem to suffer the same affliction.

This general concept can be applied to other depositories. Since we deal specifically with the banking industry we make use of the terms “banks” and “depositories” interchangeably.

But be mindful not to reverse the proposition—an obligation to someone does not necessarily create a right [33]: 375).

We refer here to Hohfeld’s [19] distinction between claim rights and liberty rights.

Kant considers two shipwrecked men with one plank between them, but of sufficient size to only save one of them. Does either have a right to fight the other off and in essence kill him, while he saves himself? Kant’s denial of such a right was the first reasoned defense of the decision, although both Pufendorf and Hobbes had briefly considered the conflict previously.

Indeed, in a deposit contract it is the depositor that would pay the depository for these safekeeping services. In many circumstances today, depositors do not pay a fee in part because banks waive it to entice business, and also, as we shall see, because banks treat the deposited funds as loans.

We know of the depositor´s intent because there are financial products commonly used (e.g., investment accounts, time deposits, etc.) that are not made for safekeeping or availability purposes. The fact that the depositor does not make use of these alternatives suggests a different intention which the bank deposit fulfills.

This does not imply that the depository cannot place constraints on these withdrawals out of practical convenience or necessity (e.g., business hours). It means that the depositor can access his funds within the limits as set out in the contract, and that the depository must also abide by this requirement. For example, if the deposit stipulates that withdrawals are available during business hours only, the depository cannot deny the depositor’s right to his funds during these hours. Furthermore, the full availability of the deposit has an economic definition that differs from the legal requirement, namely, that nothing can be done to impinge on the availability of the good (see [6]).

The difficulty inherent in the bank returning the deposit on demand is complicated by the fact that not only does it not know when this deposit will be requested, but also that the depositor himself lacks this knowledge. As money and deposits are held to provide insurance against an unknown future event, it is impossible to predict when this future event will occur, as well as in what amount the required funds will be.

The dual claim nature of the fractional-reserve demand deposit contributes to a wealth affect whereby more than one party is feels wealthier than would otherwise be the case as they (depositor and bank) each deem ownership of the deposit to reside with them. (In fact, legal ownership solely lies with the bank notwithstanding the general consumer perception that the depositor owns the deposit.) To the extent that lending against fractional reserves is now a primary function of banks, the undue creation of credit and debt contributes to the “normalization” of debt found in Peñaloza and Barnhart [37]. It is the duality of ownership claims to the FRDD that Hoppe et al. [21] find problematic, both economically and ethically, with the contract.

This is similar to the historical use of an “option clause” on deposits that gave a bank to the ability to not redeem the depositor’s funds on demand if constrained by liquidity. In a similar manner to the modern notice of withdrawal waiver, these clauses solved the apparent problem of an impossible to honor conflict of rights while creating another conflict by altering the rights of the depositor and forcibly converting him into a lender.

Holding “safer” investments to sell in the event of a withdrawal that cannot be met through the bank’s liquid reserves will not solve this problem. All non-money financial assets are exposed to some degree of risk inherent from either their fluctuating market values or the timing of their availability. Since the withdrawals of deposits are not forecastable, there is no way for a bank to ensure that a safer portfolio of assets will provide better collateral against its deposit base than will a riskier portfolio. Recent complications during banking crises (e.g., between 2008 and 2012 in Belgium, Cyprus, Iceland, Ireland, the United Kingdom, United States and Spain) all exposed the fallacy that a sufficiently safe or liquid portfolio could protect banks against a critical mass of withdrawals. This outcome stems from the uncertainty of holding an asset that is valued on a market or available after only some period, an outcome that does not exist if the bank held money in reserve. In any case, holding safer assets does nothing to rectify the conflict of rights inherent in the fractional-reserve deposit contract.

It is not even clear that the economic problem is fully solved by deposit insurance. Evidence already points to financial instability by extending deposit insurance in the United States to products such insurance was not designed for. With such overreach, financial stability can be enhanced by removing insurance from some of these products [23, 24].

References

Bagus, P., Gabriel, A., & Howden, D. 2016. Reassessing the Ethicality of Some Common Financial Practices. Journal of Business Ethics, 136/3: 471–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2525-9.

Bagus, P., and D. Howden. 2009. The Legitimacy of Loan Maturity Mismatching: A Risky, but Not Fraudulent, Undertaking. Journal of Business Ethics 90(3): 399–406.

Bagus, P., and D. Howden. 2011. Still unanswered quibbles with fractional reserve free banking. The Review of Austrian economics 25(2): 159–171.

Bagus, P., and D. Howden. 2012. The Continuing Continuum Problem of Deposits and Loans. Journal of Business Ethics 106(3): 295–300.

Bagus, P., and D. Howden. 2013. Some ethical dilemmas of modern banking. Business Ethics (Oxford, England) 22(3): 235–245.

Bagus, P., and D. Howden. 2016. The economic and legal significance of “full” deposit availability. European Journal of Law and Economics 41(1): 243–254.

Bagus, P., D. Howden, and W. Block. 2013. Deposits, Loans, and Banking: Clarifying the Debate. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 72(3): 627–644.

Bagus, P., A. Gabriel, and D. Howden. 2016. Reassessing the ethicality of some common financial practices. Journal of Business Ethics 136: 471–480.

Bagus, P., D. Howden, and A. Gabriel. 2015. Oil and Water Do Not Mix, or: Aliud Est Credere, Aliud Deponere. Journal of Business Ethics 128(1): 197–206.

Cobden Centre. 2010. Public Attitudes Toward Banking. Retrieved from www.cobdencentre.org/?dl_id=67.

Cohn, A., E. Fehr, and M.A. Maréchal. 2014. Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry. Nature (London) 516(7529): 86–89.

Edelman. 2015. Edelman Trust Baramoter. http://www.edelman.com.

Feinberg, J. (1973). Social Philosophy. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs.

Fisher, I. 1936. 100 % Money. New York: Adelphi.

Galbraith, J.K. 1975. Money: Whence it Came, Where it Went. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Gallup. 2014. Honesty/Ethics in Professions. http://www.gallup.com/poll/1654/honesty-ethics-professions.aspx.

Hayek, F. 1973. Law, Legislation and Liberty: Volume 1—Rules and Order. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Henry, P. C. 2010. ‘How Mainstream Consumers Think about Consumer Rights and Responsibilities’, The Journal of Consumer Research, 37/4: 670–87. Oxford: The University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.1086/653657.

Hohfeld, W.N. 1919. Fundamental Legal Conceptions as Applied in Judicial Reasoning: And Other Legal Essays. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hoppe, H.-H. 1994. How is fiat money possible? ? Or, the devolution of money and credit. The Review of Austrian Economics 7(2): 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf01101942.

Hoppe, H.-H., J.G. Hülsmann, and W. Block. 1998. Against fiduciary media. Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 1(1): 19–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12113-998-1001-8.

Howden, D. 2014. A pre-history of the Federal Reserve. In: The Fed at one hundred (D. Howden & J. Salerno, Eds.) pp. 9–21. London: Springer.

Howden, D. 2015. ‘Money in a World of Finance’, Journal of Prices and Markets, Papers and Proceedings of the 3rd Annual International Conference of Prices and Markets, Toronto, ON, Nov. 6–7, 3/2: 13–20.

Howden, D. 2015. Rethinking deposit insurance on brokered accounts. Journal of Banking Regulation 16(3): 188–200.

Huerta de Soto, J. 2012. Money, bank credit and economic cycles. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Inst.

Jansen, David-Jan., Robert H. J. Mosch, and Carin A. B. van de Cruijsen. 2015. When does the general public lose trust in banks? Journal of Financial Services Research 48: 127–141.

Kant, I. 1991. Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Knell, Markus, and Helmut Stix. 2015. Trust in Banks during normal and crisis times—Evidence from survey data. Economica 82(1): 995–1020.

Leoni, B. 1961. Freedom and the Law. D. Van Nostrand Company: Princeton.

Lynch, J.J. 1994. Banking and finance: Managing the moral dimension. Cambridge: Gresham.

Mises, L. von. (1949). Human Action: A Treatise on Economics. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Mises, L. von (1971). The theory of money and credit. Irvington-on-Hudson: Foundation for Economic Education.

Montague, P. 1980. Two Concepts of Rights. Philosophy and Public Affairs 9(4): 372–384.

Montague, P. 1984. Rights and Duties of Compensation. Philosophy and Public Affairs 13(1): 79–88.

Montague, P. 2001. When rights conflict. Legal Theory 7(3): 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352325201073037.

Morgan, G. 2010. Legitimacy in financial markets: Credit default swaps in the current crisis. Socio-Economic Review 8(1): 17–45. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwp025.

Peñaloza, L., and M. Barnhart. 2011. Living U.S. Capitalism: The Normalization of Credit/Debt. The Journal of Consumer Research 38(4): 743–762. https://doi.org/10.1086/660116.

Rothbard, M. 2008. The Mystery of Banking. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Rothbard, M. N. 1994. Theœ case against the Fed. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Steiner, H. 1994. An essay on rights. Oxford [u.a.]: Blackwell. Retrieved from unknown.

Stöckl, T. 2015. ‘Dishonest or professional behavior? Can we tell? A comment on: Cohn et al. 2014, Nature 516, 86–89, “Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry”’, Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 8: 64–7. Elsevier B.V. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbef.2015.10.003.

Zingales, L. 2015. ‘Presidential Address: Does Finance Benefit Society? The Journal of Finance 70(4): 1327–1363. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12295.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bagus, P., Howden, D. Consumer rights and banking contracts. J Bank Regul 24, 105–114 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41261-021-00185-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41261-021-00185-x