Abstract

Despite an increasing number of studies identifying factors that influence the internationalization process for early internationalizing firms (EIFs), it remains unclear which of these numerous factors could play a strategic role and, more specifically, when. This paper develops a new conceptual framework anchored in the resource-based view to identify strategic resources that can explain EIFs’ internationalization process accurately over time. Building on a systematic literature review based on 102 papers covering a period of 29 years, we methodically present a phase-by-phase observation of EIFs’ internationalization process to identify the strategic relevance of different influential resources. The results highlight the importance of the shift from individual to organizational resources, which occurs at a critical phase of transition from the entry to the post-entry phase. Studying the evolution of strategic resources along four phases allows us to determine that the progress of EIFs through the phases of their internationalization process is closely linked to their resources’ development process. This study suggests some promising research avenues, at theoretical and methodological levels, and results in a series of concrete recommendations intended for entrepreneurs and/or managers of EIFs.

Résumé

Malgré le nombre croissant de publications sur les facteurs influençant le processus d’internationalisation des entreprises à internationalisation précoce (EIP), il reste difficile de déterminer lesquels pourraient jouer un rôle stratégique, et surtout à quel moment du processus. Cet article développe un modèle conceptuel novateur ancré dans la théorie basée sur les ressources permettant d’identifier précisément les ressources stratégiques qui favorisent la soutenabilité du processus d’internationalisation des EIP dans le temps. À l’aide d’une revue systématique comprenant 102 papiers couvrant une période de 29 ans, nous identifions les ressources stratégiques à la progression des EIP à travers les quatre phases caractérisant leur processus d’internationalisation. Les résultats montrent également l’importance du passage des ressources individuelles aux ressources organisationnelles en phase de transition, située entre la phase d’entrée à l’international et la phase de post-entrée. En portant l’accent sur le lien étroit entre le développement de certaines ressources et la progression des EIP à travers le processus d’internationalisation, cet article propose des pistes de recherches futures prometteuses, tant au niveau théorique que méthodologique, et aboutit à une série de recommandations concrètes à destination des entrepreneurs et/ou des managers d’EIP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Summary Highlights

Contributions of the paper: Building on a systematic literature review over 29 years, this paper contributes to a better understanding of the factors, and especially strategic resources, that influence early internationalizing firms’ (EIFs’) internationalization process, in response to recent calls in EIF literature.

Research questions/purpose: What are the strategic resources associated with each phase of the EIF internationalization process?

Methodology: Using the resource-based view as a theoretical framework, a systematic review of the literature in the field of international entrepreneurship was performed to identify strategic resources that can explain EIFs’ internationalization process over time.

Data base/information: The systematic literature review located 102 papers published between 1989 and 2018 that constituted the corpus and main data for this paper.

Results/findings: The results provide a clear identification of the strategic resources associated with the four distinct phases (pre-founding phase and start-up period, entry-stage and early internationalization phase, transition period from the entry to the post-entry phase, post-entry phase) that shape the EIF internationalization process. They also show the importance of the shift from individual to organizational resources, which occurs at a critical phase of transition from the entry to the post-entry phase

Limitations: The main limitation of this research is that it does not consider any contextual influence. However, it provides a common unified conceptualization of the internationalization process for all types of EIFs.

Managerial/theoretical implications: The proposed conceptual framework complements previous research on the factors influencing the EIF internationalization process by specifying the strategic resources associated with each phase. It also shows that the EIF internationalization process is clearly linked to their resources’ development process. By identifying the strategic resources associated with each phase, this research provides useful managerial recommendations.

Recommendations for further research: Promising avenues for further research pertain to the EIF internationalization process and its influencing factors, and especially we insist on the need for further investigations on the transition period from entry to post-entry phases, and on the post-entry phase.

Practical implications and recommendations: This paper discusses a series of concrete recommendations, which could help entrepreneurs and/or managers of EIFs manage their internationalization process over time. More specifically, it details how to incorporate the temporal component to help EIFs’ decision makers.

Public policy recommendation: Our recommendations with regard to international support services focus on the need to locate the phase in which the EIF finds itself. This will help entrepreneurs or managing teams identify and capture the strategic resources that will allow their business to grow.

Introduction

Early internationalizing firms (EIFs) are an increasingly popular subject of study in the international entrepreneurship literature (Jiang et al. 2020; Servantie et al. 2016). They constitute a specific class of international firms given their unique property of beginning their international activities soon after founding (Rialp et al. 2005; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2019; Zucchella et al. 2007). The term EIF encompasses several types of international firms, such as international new ventures (Oviatt and McDougall 1994), born global (Rennie 1993), and global start-ups (Oviatt and McDougall 1995), which have been extensively conceptualized in extant literature. An important body of research focuses on the factors driving EIFs’ early-phase internationalization or short-term international growth (Jones et al. 2011; Keupp and Gassmann 2009; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2019). However, studies exploring the factors explaining the internationalization process of EIFs over time are still lacking (Jones et al. 2011; Øyna and Alon 2018; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2019). Although the international behavior and initial success of EIFs is encouraging, their long-term growth is far from assured, because they continue to encounter difficulties with surviving (Almor et al. 2014; Li and Deng 2017; Meschi et al. 2017; Puig et al. 2018). Rialp et al. (2005) point out the lack of exploration of “driving forces” of the internationalization of EIFs, suggesting the need to consider these factors closely and over time (Øyna and Alon 2018; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2019). Romanello and Chiarvesio (2019, p. 41) call on scholars to “try to summarize the results that have emerged so far and propose a new conceptual development on the drivers of survival and growth of EIFs,” indicating more specifically that researchers “should investigate the drivers of performance across the growth phases of EIFs” (p. 34).

In response to this call, we propose a resource-based view (RBV) framework to identify strategic resources in relation to each phase of the EIF internationalization process. The RBV framework has three advantages. First, it allows us to analyze the EIF internationalization process in various evolutionary phases, in line with previous research on EIFs (Gabrielsson et al. 2008, 2014; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017; Trudgen and Freeman 2014). These phases differ from those cited in conventional stage models, such as those experienced by traditional small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), with regard to the specific challenges they encounter (Bilkey and Tesar 1977; Gabrielsson et al. 2008; Johanson and Vahlne 1977, 2009). Second, in a dynamic setting, the RBV also helps identify the strategic resources characterized by particular properties, which are sources of competitive advantage (Barney 1991; Barney et al. 2001), and how they develop over time (Helfat and Peteraf 2003). Third, the lens of the RBV allows a multilevel analysis by considering individual, organizational, and environmental factors (Clelland et al. 2006; Westhead et al. 2001). With this foundation, we aim to identify the strategic resources at the different levels needed to navigate the EIF internationalization process by addressing the following question: What are the strategic resources associated with each phase of the EIF internationalization process?

We conducted a systematic review of literature on the factors explaining the EIF internationalization process to address this research question. An initial analysis of 102 papers published between 1989 and 2018 allowed us to identify the factors influencing each phase. This analysis provided an exhaustive list of factors but does not reveal how strategic resources evolve over time and how they can sustain and foster the passage from one phase to the next. Therefore, in line with our theoretical RBV framework, we reread the papers, focusing on strategic resources for EIFs. This second analysis provides powerful insights to explain the sources of heterogeneity for the EIFs in which the resources and capabilities reside.

This research thus moves toward a better understanding of the EIF internationalization process. Our key contributions are threefold. First, anchored in the RBV, this framework goes further than previous literature reviews (Jiang et al. 2020; Keupp and Gassmann 2009) and fills a gap identified by prior literature (Romanello and Chiarvesio 2019) by specifying a set of strategic resources (Jones et al. 2011; Øyna and Alon 2018) that EIFs require to reach each phase and move forward in their internationalization process. In so doing, our analysis determines that the EIF internationalization process is closely linked to the resources’ development process. Second, we contribute to reducing “the considerable variety and disparity of the results usually found in terms of those factors mostly characterizing successful internationalization of early internationalizing firms” (Rialp et al. 2005, p. 160). Unlike works based on a “holistic perspective” (Crick and Spence 2005) that combines different theories to create a comprehensive list of explanatory factors, we contribute to the development of the RBV in the field of international entrepreneurship by explicitly integrating the temporal aspects associated with EIF internationalization (Evers et al. 2019; Peng 2001; Priem and Butler 2001). Third, we develop theoretical and methodological avenues for further research in relation to the EIF internationalization process and its driving forces. To establish these contributions, in the next section, we explain our systematic review methodology and then present the findings. Next, we develop the proposed conceptual framework and its propositions. We conclude by discussing implications, limitations, and avenues for further research.

Theoretical framework

The RBV provides a solid theoretical basis for understanding the phenomenon of early internationalization. As Peng (2001) argues, it solved a “key puzzle” by explaining how some new and small firms can succeed abroad rapidly without going through the different phases described by the traditional approach. From this view, the sequence and speed of the internationalization process are no longer determined by the extent to which companies can gradually accumulate knowledge about foreign locations (Johanson and Vahlne 1977, 2009). New and small firms possess resources that enable earlier internationalization. Barney (1991, p. 101) describes these resources as “all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information, knowledge, etc. controlled by a firm that enables the firm to conceive of and implement strategies that improve its efficiency and effectiveness.” Some of these resources are considered strategic in that they are most likely to lead to competitive advantage, notably in the case of early internationalization (Coviello and McAuley 1999). Strategic resources have special proprieties. They are valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and not substitutable (Barney 1991; Barney et al. 2001). The link between strategic resources of EIFs and the early nature of their internationalization process has been shown in several studies (Freeman and Cavusgil 2007; Kumar 2012; Weerawardena et al. 2007). They shed light on a series of resources related to the characteristics of entrepreneurs and firms as well as their external environment (see Jiang et al. 2020 for a review). However, studies on EIF internationalization still pay insufficient attention to process- and implementation-related issues (Peng 2001). As Schu et al. (2016, p. 734) note, “the majority of studies conceptualize internationalization speed as uniform throughout the entire internationalization process (i.e., in a single figure) or merely focus on the length of time from inception to the first internationalization step.”

While incorporating time remains a challenge for RBV scholars (Priem and Butler 2001), especially in international entrepreneurship (Evers et al. 2019), a more dynamic model of the RBV may provide powerful insights. First, the dynamic capabilities approach (Teece et al. 1997) shows the importance of analyzing change in resources and capabilities over time because firms’ choices about resources are influenced by past choices. “This path [of resource development] not only defines what choices are open to the firm today, but it also puts bounds around what its internal repertoire is likely to be in the future” (Teece et al. 1997, p. 515). Thus, the definition of strategic resources we retain in this study encompasses all dynamic, knowledge-/process-based aspects of resources (Foss 1997) owned or controlled by a firm to sustain its competitive advantage over time. Second, following Helfat and Peteraf (2003), the path of resources and capabilities development can be viewed according to a three-stage life cycle (i.e., founding, development, and maturity). From this view, speed cannot be reduced to the time between a company’s foundation and its first international activity or be summarized in an overall observation. The time frame between two consecutive events in different stages within the whole internationalization process must be taken into account (Casillas and Acedo 2013; Van de Ven and Pool 1995). Consequently, we consider that a process-based approach that embraces the entire process of internationalization can help explain the sources of heterogeneity for the EIFs in which the resources and capabilities reside.

Accordingly, we follow previous research that suggests the EIF internationalization process can be analyzed in evolutionary phases (Gabrielsson et al. 2008, 2014; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017; Trudgen and Freeman 2014) that featuring unique characteristics in terms of obstacles and opportunities (Johanson and Martín Martín 2015). Scholars such as Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson (2013) and Oxtorp (2014) concur that EIFs face challenges all along their internationalization process. Johanson and Martín Martín (2015, p.493) specify that “each phase requires its specific combination of organization, competence, and resources.” It is thus a necessity to understand what is at stake in each phase to help them manage crises successfully and evolve over time. In general, and despite some extensive considerations, the question of how EIFs behave over time across their growth phases has remained understudied, and our understanding of their decision making is limited (Cavusgil and Knight 2015). Although previous research has demonstrated that factors influencing EIF internationalization process likely evolve over time and along phases (Efrat and Shoham 2012; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017), these phases are not the same as those described in the Uppsala approach (Johanson and Vahlne 1977, 2009). The EIF internationalization process deviates considerably from that followed by traditional internationalizing SMEs, especially in the first stage. McDougall et al. (1994) emphasize the imprinting influence of an early initiation of internationalization for later development. However, few EIF internationalization studies address the process of internationalization after the inception, probably because these phases are not easily operationalized (Gabrielsson et al. 2008). Extant models include two to five phases, from pre–start-up to consolidation and break-out phases (Gabrielsson et al. 2008; Trudgen and Freeman 2014), as well as a potential transition from early international entry to post-entry phases (Turcan and Juho 2014). In the absence of consensus about the exact phases in practice, adopting an RBV phase-based approach can provide a better understanding of EIFs’ growth by identifying the strategic resources needed to get through its various phases over time.

Research method

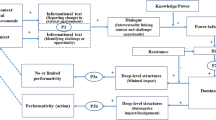

We seek to synthesize relevant research on the factors influencing EIF internationalization processes to develop a framework that clearly identifies the strategic resources associated with each stage of the process. Our systematic review aims to collect “all evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimizing bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drown and decisions made” (Higgins and Green 2011, p. 6). Accordingly, it consists of five steps (Denyer and Tranfield 2009): (1) formulation of the research question, (2) location of relevant studies, (3) selection and evaluation of studies, (4) analysis and synthesis the data, and (5) report the results. This protocol ensures a clear description of the steps taken and also helps ensure the rigor and transparency of the process. In addition, we specify the settings for our review (keywords, databases, time spans, and languages) and the procedure used select the studies, using consecutive exclusion and inclusion criteria. Fig. 1 provides a summary of the protocol.

Location of relevant studies

In line with Denyer and Tranfield (2009), we started by formulating the research question that guides and shapes the review protocol: What are the strategic resources associated with each phase of the EIF internationalization process? Then, we proceeded to locating relevant studies. A preliminary literature review identified key concepts and keywords, which formed the basis of our database search. For completeness, we decided to review studies written in English and French (Hesping and Schiele 2015). We established two keyword lists, one in English (Group A) and one in French (Group B); for each, we divided the keywords into two subgroups (see Appendix 1 (Table 2)). In the English list, Group A1 contains 38 keywords or full expressions that describe EIFs (e.g., international new venture, born global, global start-up), along with phrases such as “SME and internationalization,” because some articles discuss EIFs in the broader context of small firm internationalization (e.g., comparative studies of various types of small firms). We drew this list from Servantie’s (2007) exhaustive list of 48 terms. The two most commonly used terms to refer to EIFs (Øyna and Alon 2018) are international new venture (INV) (Oviatt and McDougall 1994) and born global (Rennie 1993), which frequently are used interchangeably, despite their distinct definitions (Romanello and Chiarvesio 2019). In line with recent reviews (Bembom and Schwens 2018; Rialp et al. 2005; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2019) and to avoid confusion, we maintain the broader term, EIFs, to refer to all firms that internationalize soon after their inception. Then Group A2 includes 14 keywords that describe the EIF internationalization process. We selected these keywords by analyzing recent contributions (Hagen and Zucchella 2014; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017; Turcan and Juho 2014). We then combined each keyword in Group A1 with each keyword in Group A2, to create 532 search strings for the database search in English. We repeated this process for the French version (Groups B1 and B2).

We conducted the searches at the end of 2017 on Google Scholar, Business Source Premier, EconLit, Science Direct, and Cairn databases and implemented electronic alerts for 2018. We elaborated different settings depending on the capacities of each database.Footnote 1 This screening process produced 2052 references.Footnote 2 We used Mendeley software to check for duplicates, which decreased the total number of references to 1878.

Selection and evaluation of studies

We set several exclusion and inclusion criteria. As recommended by Jones et al. (2011) and Servantie et al. (2016), we considered every article published after 1989, noting that McDougall (1989) is the first study of international entrepreneurship. We excluded studies published in edited books, conference proceedings, editorials, commentaries, and case studies (e.g., for teaching purposes), due to the potential lack of peer review processes. Although this criterion excludes non-journal publications, it still provides an accurate representation of the state of current literature on the explanatory factors of EIF internationalization processes. To control for study quality, we selected only articles published in journals ranked by the Academic Journal Guide (AJG)Footnote 3 (2018) or CNRSFootnote 4 (2018). These exclusion criteria reduced the number of references to 995. We then read the 995 abstracts to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria.

At this point, we chose to consider the features of the firms (e.g. EIFs, SMEs) studied in each article. We selected papers focusing on EIFs only, except for papers providing information on EIF internationalization process by comparing them with traditional SMEs. After we removed unavailable references and performed another check for duplicates, the number of references dropped to 134. The percentage of selection at this stage is 13.47%, which is equivalent to other systematic reviews (Baier-Fuentes et al. 2018; Ellwood et al. 2017; Hesping and Schiele 2015). We added 13 references after manually searching for articles in the most relevant international entrepreneurship academic journalsFootnote 5 and 5 references by using a snowball approach. Ultimately, we read 151 articles in their entirety and found 95 to be relevant for our study. The 56 articles that we deleted mostly focused on SMEs without specific output about EIFs. We added 7 articles in 2018, which we identified by the electronic alerts preivously implemented, leading to 102 references for analysis. Three journals contribute the most entries: International Business Review (AJG: 3; CNRS: 2) with 20 publications, Journal of International Entrepreneurship (AJG: 1; CNRS: 3) with 14 publications, and Journal of World Business (AJG: 4; CNRS: 2) with 10 publications. Together, they represent 43.1% of the corpus.

Analysis and synthesis

Consistent with the purpose of a systematic review, we first used an inductive approach that allowed the research findings to emerge from dominant themes inherent in the raw data by building causal networks (Miles et al. 2013). To code the 102 papers, we imported them into ATLAS.ti 8 software. Following Saldaña (2015), we divided the coding into two cycles. In the first cycle, we developed a short coding sheet with general information about every article (e.g., publication year, journal, theoretical framework, methodology). Other codes emerged while reading the papers, so we identified phases that shape EIF internationalization, along with numerous associated factors. In the second cycle of coding, we grouped previously identified codes “into a smaller number of categories, themes, or constructs,” known as “pattern codes” (Miles et al. 2013, p. 86). We then divided the data analysis into three steps.

First, we analyzed the various models of EIF internationalization process within the corpus and identified the phases that shape the process. From the 102 papers, we found 16 models of EIF internationalization process, containing between two and five phases (Appendix 2 (Table 3)). The two- and three-phase models appear too limited to capture the complete EIF internationalization process, due to the clear importance of the transition phase (from entry to post-entry) (Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017; Turcan and Juho 2014). We also determined that the two models that feature five phases are too broad (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2017; Laurell et al. 2017), considering that the new venture creation phase tends to be very short when EIFs internationalize (Luostarinen and Gabrielsson 2006). Thus, we consider merging the pre-founding and new venture creation phases. In reviewing the commonalities and differences among these 16 models, we considered Romanello and Chiarvesio’s (2017) version as a good summary of all the important features described by other dynamic models. In brief, these authors assert that EIFs undergo four distinct phases: (1) the pre-founding phase and start-up period, which starts before the firm creation and ends before its entry into a foreign market; (2) the entry stage and early internationalization phase, starting when the firm enters its first foreign market; (3) the transition period from the entry to the post-entry phase, which begins when the firms’ foreign market portfolios increase to the extent that they suffer organizational problems, such as an inability to fill orders or supply human resources; and (4) the post-entry phase, when EIFs commit to many foreign markets and their growth is dominated by international sales. This evolutionary internationalization process is not linear, which distinguishes it from the Uppsala Model (Johanson and Vahlne 1977, 2009). It is characterized by recursivity, highlighted by the transition phase, during which EIFs might deinternationalize or reinternationalize (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2017; Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson 2013). Last, similar to the Uppsala model, the time spent in each phase varies across firms.

Second, we classified the plethora of factors that can influence the internationalization process, according to the 102 papers. This step generated distinct categories of factors (i.e., individual, organizational, and environmental) according to the principles of aggregation. Building on Romanello and Chiarvesio’s (2017) four phases, we used precise coding to associate the identified factors with the phase they influenced.

Third, using the theoretical framework anchored in the RBV, we conducted a rereading step of the identified factors to capture the strategic resources and capabilities that facilitate the efficient, effective development and implementation of a strategy that generates superior performance over time (Barney and Arikan 2001; Helfat and Peteraf 2003). This step allows a fine-grained analysis by identifying these strategic resources according to their special characteristics (i.e., valuable, rare, imperfectly imitable, and not substitutable) as well as their effect on a firm’s competitive advantage or other performance measures relative to its competitors. By way of example, the resources identified as strategic resources were described as “difficult to imitate” (Sharma and Blomstermo 2003) or “costly to imitate or to substitute” (Coviello and Cox 2006) in the 102 papers. We also included as strategic resources those considered a source of “competitive advantage” (Bloodgood et al. 1996; Freeman et al. 2006) and “superior performance” (Musteen et al. 2010) for the EIF, as well as those that explicitly have a “strategic role” (Mort and Weerawardena 2006) for its growth.

Findings

Factors explaining the EIF internationalization process

Our coding process identified 49 explanatory factors of EIF internationalization. Following the principles of aggregation, we generated 12 categories, according to frequency of citation, reflecting three levels of analysis: individual (4 categories), organizational (5 categories), and environmental (3 categories) (see Appendix 3 (Table 4)).

At the individual level, we identified 11 factors related to entrepreneurs, which we can group into 4 categories. Entrepreneurs’ previous experience refers to their international experience (Baronchelli and Cassia 2014), experience in the same industry (Evers 2010), or previous entrepreneurial work (Symeonidou et al. 2017). Entrepreneurs’ networks, a real resource pool for the firm (Kocak and Abimbola 2009; Lindstrand et al. 2011), have a significant positive effect on internationalization (Manolova et al. 2014). Furthermore, entrepreneurs’ cognitive characteristics, including self-efficacy (Evald et al. 2011) and global mind-set (Gabrielsson et al. 2008; Lin et al. 2016), can influence the success of their international operations (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2016). Finally, entrepreneurs’ personal characteristics, such as age (Cannone et al. 2014) and family background (McAuley 1999), are relevant.

At the organizational level, the 28 factors we identify can be aggregated into 5 categories, representing the main firm resources (Kellermanns et al. 2016). This segmentation allows us to consider the full range of organizational factors and resources present in EIFs: human capital (Ughetto 2016), relationship capital (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998), organizational capital (Khan and Lew 2018), physical capital (Andersson et al. 2014; Colovic and Lamotte 2014), and financial capital (Laanti et al. 2007; Trudgen and Freeman 2014) resources.

Finally, on the environmental level, we gathered the 10 factors into 3 categories. Worldwide technological evolutions can lead to the creation and increased development of EIFs (Bloodgood et al. 1996; Zucchella et al. 2007). The characteristics of the home market can either foster or hinder EIFs’ internationalization (Knight et al. 2004; Madsen and Servais 1997). Finally, industry factors can have substantial effects on EIFs’ internationalization, by either impeding or promoting it (Oviatt and McDougall 1994; Porter 1979, 1980).

After identifying the exhaustive list of 49 factors, we reduced the scope of analysis to strategic resources only. The previous list, albeit informative, does not help us understand what actually matters during the internationalization process for EIFs. Considering the strong support for the importance of resource-based factors for predicting internationalization (Freeman et al. 2010; Hitt et al. 2006; Li 2018), as well as Barney and Arikan”s (2001) argument that internationalization strategies that exploit strategic resources outperform those that exploit other resources, we conducted a rereading through the prism of the RBV. Doing so allowed us to clearly identify the strategic resources associated with each phase of the internationalization process. Strategic resources belong to all three levels previously identified—individual, organizational, and environmental—and are hereafter presented according to the phase with which they are associated. As a summary, Table 1 highlights relevant strategic resources associated with the four phases of the Romanello and Chiarvesio's (2017) model. Our findings clearly show the imbalance in research attention: Studies of the two first phases (pre-founding and start-up period, entry, and early internationalization phase) are plentiful, but research on the latter two (transition from entry to post-entry phase and post-entry phase) is lacking. In response to many calls, research on the post-entry phase has begun to emerge (Sleuwaegen and Onkelinx 2014; Khan and Lew 2018). Moreover, and as by Romanello and Chiarvesio (2019) point out, many studies do not indicate whether the factors they study relate to entry or post-entry phases, which prevents any clear link of a single factor to a single phase. Next, we highlight how EIFs navigate along the four phases of their internationalization process with a focus on strategic resources.

Strategic resources during the pre-founding phase and start-up period

The pre-founding phase and start-up period is characterized by a focus on concept generation (Coviello and Cox 2006; Laurell et al. 2017) and a clear intention to internationalize (Coviello and Munro 1997). At some point, the EIF is officially founded. One or more founding entrepreneurs leverage their previous experience and networks, as resource pools, to operate in this phase (Freeman et al. 2006; Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson 2013). These two categories of individual factors (entrepreneurs’ previous experience and networks) are strategic resources (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2016; Ughetto 2016). Entrepreneurs’ previous experience (Kocak and Abimbola 2009; Weerawardena et al. 2007) includes international experience (Khan and Lew 2018) or previous entrepreneurial or industrial experience (Ughetto 2016), which provide them with specific knowledge and skills (e.g., international, managerial, technological) (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2016; Kumar 2012). Such experience fosters early and rapid internationalization (Oviatt and McDougall 1994) and also determines firms’ internationalization trajectories (Madsen and Servais 1997). Entrepreneurs with more experience can identify foreign market opportunities (due to better knowledge of foreign markets), which can likely enhance firm success in foreign markets (Kumar 2012; Zahra and George 2002). Furthermore, a global mind-set often originates from previous experience, and this feature, especially in the early phase (Gabrielsson et al. 2014), influences the success of international operations by encouraging openness (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2016). Entrepreneurs’ networks provide both financial resources (Lindstrand et al. 2011) and experiential knowledge (Michailova and Wilson 2008), generate social capital (Kocak and Abimbola 2009), reveal foreign opportunities (Oviatt and McDougall 1994; Vasilchenko and Morrish 2011), and sometimes facilitate business contracts (Ibeh and Kasem 2011). Scholars agree that EIFs rely on the richness and diversity of their entrepreneurs’ networks (Dominguez and Mayrhofer 2016; Freeman and Cavusgil 2007).

Environmental factors emerge as critical in this phase and the next one. Studies identified changing international environments (Muralidharan and Pathak 2017), including worldwide technological evolutions (Madsen and Servais 1997), as a factor that facilitates the internationalization of small firms (Bloodgood et al. 1996). Concerning the characteristics of home markets (Ibeh and Kasem 2011), academics argue that the size of domestic markets influences EIF internationalization (Knight et al. 2004): specifically, being in small domestic markets fosters early internationalization (Madsen and Servais 1997). Scholars who study the effect of the institutional context on the EIF internationalization process find that institutional context influences reliance on networks, innovativeness, and establishment of foreign partnerships (Kiss and Danis 2008). Furthermore, informal institutions (North 1991) strongly affect the pursuit of entrepreneurship as a career choice, because these institutions determine whether this choice is “socially desirable and legitimate” (Muralidharan and Pathak 2017, p. 290). The industries in which EIFs operate can have major effects on their internationalization (Oviatt and McDougall 1994; Porter 1979, 1980) by either impeding or promoting internationalization (Andersson et al. 2014). Some global industries require an international presence (Bloodgood et al. 1996; McAuley 1999). The structure (Andersson et al. 2014), competition (Oviatt and McDougall 2005), life cycle (Andersson et al. 2014), and knowledge intensity (Zucchella et al. 2007) of industry all influence the internationalization and long-term survival of EIFs. These environmental factors might be considered external resources that firms potentially leverage though (Westhead et al. 2001).

Strategic resources during the entry stage and early internationalization phase

The entry stage and early internationalization phase starts when an EIF enters its first foreign market. Studies anchored in the RBV stress the continued importance of individual factors, including entrepreneurs’ previous experience and networks. As Zettinig and Benson-Rea (2008) argue, knowledge is the critical resource in this phase, so entrepreneurs’ previous experience is a strategic resource. They possess “unique” knowledge, gained from their previous experiences, which facilitates their firms’ entry into multiple countries (Pellegrino and McNaughton 2015). Their networks also help the firms identify opportunities and acquire missing resources (Trudgen and Freeman 2014).

In contrast with previous research arguing that organizational factors begin to play a role at the transition phase (Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017), results emerging from the corpus evoked the importance of beginning to accumulate organizational resources as soon as the second phase. Relationship and organizational capital again emerge from the corpus, along with human capital as a strategic resource in this phase. Onkelinx et al. (2016, p. 360) cite the need “to have the most talented employees on-board,” which requires EIFs to recruit diverse, highly skilled people to enhance their human capital. Many EIFs suffer from resource shortfalls in this phase and mainly rely on networks to acquire necessary resources (Chetty and Campbell-Hunt 2004; Gabrielsson et al. 2008; Rialp-Criado et al. 2010). This need to acquire missing resources establishes networks as strategic resources (Coviello and Cox 2006; Freeman and Cavusgil 2007). Regarding organizational capital, product innovation allows EIFs to penetrate niche markets more quickly (Baum et al. 2015; Knight et al. 2004). The firm’s reputation and stable leadership also are important resources, which can send positive signals to employees, customers, distributors, and other partners, as well as generate new business ( Khan and Lew 2018; Kumar 2012). Organizational learning, especially international explorative learning, is essential to helping EIFs discover opportunities and acquire foreign-market knowledge (Gabrielsson et al. 2014).

Strategic resources during the transition period from entry to post-entry phases

The transition period begins when the firms’ foreign market portfolios increase to the extent that they begin to suffer organizational problems, such as an inability to fill orders or supply human resources (Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson 2013). At this point, the firm does not possess a solid enough organizational structure, which can generate crises. It marks a shift in the EIF internationalization process; entrepreneurs move aside and let organizational resources and capabilities take over (Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017). Although Turcan and Juho (2014) do not consider it a defined phase, they recognize it as a “made-it” point, at which EIF management shifts from entrepreneurial to professional. During this transition, the firm must develop resources and capabilities at the organizational level to continue its internationalization smoothly. Firms must develop the resources they began to acquire during the second phase. This represents a clear shift of strategic resources that transitioned from the individual to the organizational level. Therefore, EIFs rely heavily on export and marketing managers because their firms’ growth is about to be consolidated.

Human capital resources are strategic resources for fostering the development of EIFs. This term refers to a “range of skills developed over time through both education and work experience,” which “contribute to the creation of the tacit and codified knowledge that is the basis of firms’ capabilities and that in turn, generate superior performance” (Ughetto 2016, p. 840). Through these resources, firms can acquire foreign market, technological, and international knowledge (Efrat and Shoham 2012; Fletcher and Harris 2012). Diversity in the workforce and the number of employees can be key resources (Loane et al. 2007; Welbourne and De Cieri 2001) that help EIFs widen their knowledge bases and expand their networks, including internationally. During this phase, it becomes paramount to invest in training to help employees develop diverse competencies and skills (Kumar 2012). Then, the firm can expand its portfolio of international, marketing, and technical knowledge and progress to the next phase. In parallel, entrepreneurs seek to recruit highly skilled people to complement or replace them in some way (Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017). Regarding relationship capital, firms’ networks can be mobilized to ease the transition phase through their acquisition, development, and mobilization of resources. Firms’ networks not only are relevant but also can generate further resources (Coviello and Cox 2006). In line with Romanello and Chiarvesio (2017), EIFs look to develop their resource pools and invest in specific firm capabilities. Organizational learning focuses on exploitative learning (Gabrielsson et al. 2014). In this phase, characterized by a consolidation of growth in foreign markets, seizing capabilities related to technological, marketing, and management skills is critical.

Strategic resources during the post-entry phase

The post-entry phase begins when the firm has managed its transition and needs to stabilize its presence in different foreign markets after a period of early, rapid internationalization. At this point, EIFs have committed to multiple foreign markets, and their growth is dominated by international sales (Coviello and Munro 1997). To continue to access knowledge, technology, and products, EIFs may proceed to acquisition, especially technological acquisition (Øyna and Alon 2018). Overall, organizational factors, including human, organizational, and relationship capital, are strategic resources at this phase. For example, organizational learning and networking still encourage EIF internationalization, as they have throughout all phases (Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson 2013). Human capital resources remain decisive; notably, Khan and Lew (2018) find that firms that succeed in this phase have promoted diversity within their workforces in the previous phase. Beyond the list of organizational capital resources relevant in the transition phase, reconfiguring capabilities also appear central, to renew or transform the organizational resources and capabilities already present within the firm (Khan and Lew 2018). After EIFs have managed the transition and the deployment of organizational resources, the ability to grow, cultivate, and reconfigure these resources and capabilities are decisive for post-entry performance (Puig et al. 2018; Sadeghi et al. 2018).

During this phase, EIFs also might reach a breakout point, at which they become “normal” SMEs or multinationals and “leverage on the organizational learning effort they have been deployed and the experience accumulated from demanding global customers” (Gabrielsson et al. 2008, p. 397). However, Trudgen and Freeman (2014) argue that not every firm manages to accomplish this status, as evidenced by the high failure rate of EIFs (Khan and Lew 2018). Although the factors allowing EIFs to reach the break-out phase are still unknown, we see some evidence that a strong entrepreneurial orientation during this phase could be detrimental (Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson 2013; Gabrielsson et al. 2014).

Discussion

This article draws on recent literature in international entrepreneurship to contribute to a better understanding of the growth process of EIFs, which are still the subject of many failures (Li and Deng 2017; Meschi et al. 2017; Puig et al. 2018). Although a few authors have made significant progress in identifying the (specific) phases of this process over time (e.g., Gabrielsson et al. 2008, 2014; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017; Trudgen and Freeman 2014) and/or the associated factors (Efrat and Shoham 2012; Jiang et al. 2020; Zucchella et al. 2007), none have focused on the strategic resources of EIFs and their development during the different stages. The RBV theory posits that these strategic resources are likely to explain the heterogeneity of EIFs’ performance over time (Helfat and Peteraf 2003; Rumelt 1984; Teece et al. 1997; Wernerfelt 1984). Adopting the RBV in a dynamic framework and relying on a systematic analysis, we propose a typology of strategic resources according to individual, organizational, and environmental levels and according to the four phases of EIFs internationalization process (i.e., the pre-founding and start-up period, the entry-stage and early internationalization phase, the transition period, and the post-entry phase). The RBV makes it possible to link the development of strategic resources more closely to the process of internationalization of EIFs. By incorporating the temporal component (Priem and Butler 2001), our findings also lead to a set of concrete recommendations for EIFs and the organizations in charge of their international development.

Strategic resources driving the evolution of EIFs during their internationalization process

Our RBV framework depicts the EIF internationalization process and characterizes the evolution of strategic resources according to four phases. Two points merit further discussion. First, our study reaffirms the importance of the entrepreneur, in that it emphasizes the importance of the firm’s initial resource endowment for EIFs’ later development, recalling the “path-dependence of competence development” mentioned by McDougall et al. (1994). In the first two phases (i.e., the pre-founding and start-up phase and the entry-stage and early internationalization phase), the entrepreneur is the central decision maker and clearly influences the set of resource endowments within the firm (McDougall et al. 1994; Oviatt and McDougall 1994), especially concerning human and social capital (e.g., previous experience, networks). Although other team members also have a role to play in accessing new resources (e.g., technology), access to these resources will depend on the individual members’ ability to obtain these resources (Burton et al. 2002). In addition, though the entrepreneur solicits the members of his or her team and also recruits new talent, the type of endowment depends on the characteristics of those whose decisions, going forward, affect the resource development path. In particular, our analysis shows that when entering the transition phase, the influence of individual factors diminishes and is replaced by organizational factors, whose presence depends on the entrepreneurs’ actions in previous phases. This shift is far from being automatic, and the transition phase thus reflects the potential for forward and backward momentum (Bell 1995). Entrepreneurs need to be willing to manage this transition, which can present a certain difficulty (Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017). This systematic review supports Romanello and Chiarvesio’s (2017) proposition to include a transition phase that identifies the shift from the individual to the organizational level. Building on their study, our analysis confirms that this transition phase can be particularly discriminating for EIFs in determining success or failure. This study goes further by highlighting strategic resources needed during this phase. We confirm the importance of entrepreneurs’ resources and capabilities to develop the necessary foundations for organizational learning to be effective, especially stable leadership. Recruiting key talent and the training the workforce appears fundamental here. In addition, after acquiring and mobilizing diverse resources during the first phase, the firm must develop these resources to build a solid resource base. These resources will be the basis for dynamic capabilities development, which can facilitate post-entry growth.

Second, the EIF internationalization process, as characterized herein, is useful in identifying new sources of heterogeneity between EIFs in terms of their resources and capabilities. As such, our findings echo the resource and capability life cycle (Helfat and Peteraf 2003) based on three initial phases (i.e., founding, development, and maturity). At the founding stage, which represents the creation of a new capability of a new-to-the-world organization, the heterogeneity occurs essentially at the individual level “in the attributes of the individuals, the teams, their leadership, and the available inputs” (Helfat and Peteraf 2003, p. 1001). This phase covers the first two stages of the EIF internationalization process, in which the individual level predominates to a large extent. In the development stage of Helfat and Peteraf's (2003) model, resources and capabilities develop depending on the conditions at founding (e.g., prior experience that the team brings with it, initial alternatives chosen). During this phase, “capability development entails improvement over time in carrying out the activity as a team” (Helfat and Peteraf 2003, p. 1002). This phase corresponds to the critical phase of transition during the EIF internationalization process, in which organizational (rather than individual) learning must be an integral part of the process. This phase is reminiscent of Greiner’s (1972, p. 38) model, which posits that firms go through period of revolution constituting a “substantial turmoil in organization life.”

In contrast to Romanello and Chiarvesio (2017), our analysis of the corpus reveals that organizational resources are already present in the second phase, but their insufficiency leads to the enter in this transition phase. Here, the entrepreneur remains the leading actor as coordinator and supervisor (Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017).

Finally, in the maturity phase, development no longer occurs; rather, maintenance of organizational routines emerges. However, not all resources and capabilities may reach the maturity phase. Given the evolutionary nature of the EIF internationalization process (Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017), internal (e.g., managerial decisions) and external (e.g., changes in demand, science and technology, availability of raw materials, government policies) selection events may affect the current trajectory of a resource by reinforcing it or branching into another stage of the life cycle.Footnote 6 Our findings show that EIF growth is largely explained by their organizational capacity to reconfigure their resources in the post-entry stage (Teece et al. 1997). Indeed, reconfiguring capabilities appears central, to renew or transform the organizational resources and capabilities already present within the firm (Khan and Lew 2018). After having managed the transition and the deployment of organizational resources, the firm possesses a solid base of capabilities that enable it to grow, cultivate, and reconfigure diverse resources and capabilities. This phase is decisive for post-entry performance (Puig et al. 2018; Sadeghi et al. 2018).

Incorporating the temporal component to help EIFs’ decision makers

Although researchers have developed several conceptualizations of the EIF internationalization process, they have been criticized for their lack of a theoretical basis, which makes it difficult to clearly delineate the boundaries between the stages (Gabrielsson et al. 2008; Jones and Coviello 2005). Moreover, extant research does not address how EIFs behave over time, and our understanding of their decision making is limited (Cavusgil and Knight 2015). We posit that, by incorporating the temporal component, the RBV approach goes beyond this limitation. The typology of strategic resources drawn from our systematic review shows significant differences according to the four phases. Such a typology can serve as a useful decision-making tool for both the leaders of EIFs and the organizations in charge of their development. In that regard, we provide recommendations using a processual approach.

Regarding the pre-founding phase and start-up period, this review reveals the central role of the entrepreneur as the key decision maker. Entrepreneurs’ attributes play an essential role during the first two phases, as they can significantly affect the firm’s initial resources endowment as well as its evolutionary path. Entrepreneurs must be aware of the strategic resources they should possess before considering creating an EIF. Beyond the classical recommendations on the importance of their individual resources (e.g., importance of entrepreneurs’ previous experiences, global mind-set and networks), entrepreneurs will also need to mobilize resources (through their network) and develop shared competencies (i.e., foreign-market knowledge) within their organization. To rely exclusively on their own knowledge or competencies would be a mistake (Coviello 2015). Entrepreneurs need to mobilize their networks and be open to external opportunities and resources.

The second phase, the entry stage and early internationalization phase, shares some similarities with the first one. In addition to strategic resources being at the individual level and thus deeply connected to the entrepreneur the recruitment of new talent, especially in the management team, is a prerequisite. We recommend that entrepreneurs build a diversified team with complementary skills to expand the firm’s resource base. Similarly, diversifying networks will allow the company to capture new resources. Thus, as Helfat and Peteraf (2003, p. 1001) suggest, “the social capital and external ties that individual team members bring with them may constitute important endowments of the founding team.” At the same time, to take full advantage of this diversity entrepreneurs must begin thinking about how to motivate and set the bar for their employees; at this point, strategically implementing organizational learning is critical.

These first two phases correspond to the initial resource endowment shaped by entrepreneurs. Whereas they require strategic resources at the individual level, the last two phases require anchoring (i.e., the transition phase) and maintaining (i.e., the post-entry phase) these resources at the organizational level.

By gradually freeing themselves from operational tasks related to the international development of their firms and relying on highly skilled people, entrepreneurs can concentrate on their vision and start structuring their organization accordingly. Thus, the transition period must be managed for the development and anchoring of organizational resources. Entrepreneurs must invest in their employees’ training and offer them a fair remuneration to retain and motivate them at this crucial turning point. They also need to be able to upgrade their skills and those of their team in certain areas by, for example, developing marketing and managerial capabilities. Indeed, “improvements in the functioning of a capability derive from a complex set of factors that include learning-by-doing of individual team members and of the team as a whole” (Helfat and Peteraf 2003, p. 1002). This transition period is the time for entrepreneurs to shape their firms’ organizational structure. On the one hand, entrepreneurs must cut the umbilical cord with their venture by trusting and relying on their team, and on the other hand, they must be able to put in place ways to improve the team’s skills. They must act as a mentor and a leader. As Romanello and Chiarvesio (2017) suggest, managing this turning point is fundamental for the survival and growth of EIFs. Going further, we suggest that research should not ignore the importance of further deepening the understanding of capacity development to move from the individual to the organizational level.

The post-entry phase is the time for entrepreneurs and their teams to focus on consolidating organizational capital resources. Typically, EIFs use their organizational capabilities to reconfigure their resources; this phase echoes SME literature (Liao et al. 2003) that argues that the maturity stage entails capability maintenance. In conjunction with the stabilization of strategic resources, entrepreneurs and their team must be able to transform and renew existing capabilities. They have to develop resources that enable the firm to change growth strategies over time (Nason and Wiklund 2018). Finally, this last phase is also time to consider various growth possibilities and acquisition strategies (Øyna et al. 2018). In a sense, the company must focus on the dynamic capabilities that will enable it to reach maturity.

Our recommendations with regard to international support services focus first on the need to locate the phase in which the firm finds itself to help entrepreneurs or managing teams identify and capture the strategic resources that will allow their business to grow. Thus, during the first two phases, support services could at first propose a program focusing on coaching entrepreneurs to help them realize their own value and provide occasion to teach them how to take advantage of their networks and previous experiences. During the last two phases, support services could then offer programs helping EIFs sustain their growth abroad, by, for example, giving them advice on creating a stable organizational structure. In summary, international support service programs should not be limited to providing operational assistance in accessing foreign markets, and they should pay more attention to the transition period by helping entrepreneurs transition from the individual level to the organizational level by setting up organizational resources.

Conclusion

This analysis of selected papers permits the identification of various phases of the EIF internationalization process and its strategic resources; however, we acknowledge it has some limitations. The first relates to context. The 102 selected papers include samples from high-tech and low-tech industries, as well as mature and emerging economies, which might influence how factors evolve from one phase to another. Continued studies should identify any such contextual influences. Empirical research might validate our conceptual framework and specify it according to the type of EIF. We did not take a contrasted view of resources; for example, we might have considered positive and negative resources (Arend 2004; Weppe et al. 2013), though the data available from the 102 papers did not permit such considerations. Finally, despite our precautions, the selection process might suffer from possible omissions; we propose only one possible interpretation of the relevant corpus.

Beyond efforts to address the limitations, continued research could pursue a meaningful agenda pertaining to the EIF internationalization process and its explanatory factors. First, though each of the four phases described herein is crucial for the development of EIFs, marked by its own challenges and opportunities (Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson 2013), we call specifically for further research on the third and fourth phases (transition and post-entry phases). Although some literature points to the factors and strategic resources associated with them (Øyna and Alon 2018), further study is needed to understand the evolution of EIFs over time (Li and Deng 2017; Sleuwaegen and Onkelinx 2014; Ughetto 2016) and on the basis of more precise indicators of performance and survival. By focusing on the post-entry phase and its strategic resources, researchers could equip EIF managers with more effective tools to improve their survival rates and increase their chances of reaching the breakout point and becoming multinational enterprises (Gabrielsson et al. 2008).

Second, many factors have been identified, but we lack studies that link all of them to different phases. Thus, our conceptual framework is limited, in that we can only include factors and strategic resources that already have been assigned to a phase. Further investigation is needed to specify when other factors exert influences (e.g., growth orientation, market orientation, leadership). For example, the influence of environmental factors in the transition and post-entry phase has not yet been studied, while it could be crucial. Similarly, some resources that have clear strategic relevance remain unlinked to phases (e.g., diversity among the founding team, top management team international experience and understanding of human resource value), which may signal that these resources are strategic throughout all phases of the process—a supposition that needs to be tested. Regarding human capital resources and workforce diversity, the current study offers an original, promising perspective for further research. Prior research suggests that the diversity of founding teams (Sasi and Arenius 2008; Hagen and Zucchella 2014), workforces (Lindstrand et al. 2011; Kumar 2012), and networks (Musteen et al. 2010; Hagen and Zucchella 2014) can encourage EIF internationalization. However, no studies address the potential effect workforce diversity could have among EIFs, although it several studies included in the systematic review mention it (Hagen and Zucchella 2014; Khan and Lew 2018; Kumar 2012;; Lindstrand et al. 2011; Loane et al. 2007).

To conclude our consideration of resources, and following Evald et al. (2011) and Li et al. (2015), we call for research on their complementarity, which may be a crucial driver of performance (Ennen and Richter 2010). According to Stieglitz and Heine (2007, p. 3), “assets or activities are mutually complementary if the marginal return of an activity increases in the level of the other activity.” Ennen and Richter (2010) also find that complementarity is likely among the numerous factors that constitute complex systems. Ciravegna et al. (2018) delve into the multiple configurations of resources that might foster early internationalization and uncover three, though their focus remains on the early internationalization phase. We predict that resources’ complementarity may persist across phases, as resource bundles (Dutta 2013).

Finally, our suggestions for further research also include methodological extensions. For example, by diversifying samples, continued research might derive a generalizable model of EIF growth and internationalization (Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson 2013; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017) that spans different types of EIFs (Oxtorp 2014), at different age ranges (Fernhaber and Li 2013), and from different industries and countries (Deligianni et al. 2015; Ughetto 2016). Scholars frequently call for longitudinal approaches to capture the dynamics at work during the growth of EIFs (Johanson and Martín Martín 2015; Oxtorp 2014; Trudgen and Freeman 2014). Finally, few quantitative studies address the growth of EIFs (Gabrielsson and Gabrielsson 2013; Gabrielsson et al. 2014).

Because EIFs, and SMEs more broadly, contribute substantially to the creation of new jobs and other benefits that support regional and national economies, understanding their internationalization process and factors influencing it is important. In this effort, our main theoretical contribution is to clarify and specify factors influencing the EIF internationalization process over time. In doing so, we reinforce existing literature that analyzes the EIF internationalization process according to various phases (Gabrielsson et al. 2008, 2014; Romanello and Chiarvesio 2017; Trudgen and Freeman 2014). By tightening the analysis and anchoring our research in the RBV, we contribute to a better understanding of the EIF internationalization process and identify strategic resources associated with each phase. By studying the evolution of strategic resources along four phases, we were also able to determine that the EIF internationalization process is clearly linked to the resources’ development process. As an extension, we suggest key theoretical and methodological avenues for research on EIFs. This paper also results in a series of concrete recommendations, which could help entrepreneurs and/or managers of EIFs to manage the necessary transition from individual to organizational resources to ensure their growth.

Notes

In Google Scholar, with its cross-discipline coverage and elementary research criteria, we searched only the titles for keywords. In contrast, in the Cairn database, we searched for keywords in entire articles. In Business Source Premier and EconLit, we searched titles and abstracts; in Science Direct, we searched titles, abstracts, and keywords.

Google Scholar, Business Source Premier together with EconLit, Science Direct, and Cairn respectively provided 277, 1186, 582, and 7 references.

The AJG was established by the Chartered Association of Business Schools; see https://charteredabs.org/

The CNRS (National Centre for Scientific Research) is France’s official evaluation academy; see http://www.cnrs.fr/index.php

Namely, Journal of Business Venturing, Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice; Journal of International Business Studies; Journal of World Business; Management International Review; International Business Review; International Marketing Review; Journal of International Marketing; Academy of Management Journal; Academy of Management Review; and Journal of International Entrepreneurship (Servantie et al. 2016).

Examples of these events are retirement (death), retrenchment, renewal, replication, redeployment, and recombination (Helfat and Peteraf 2003).

References

Almor T, Tarba SY, Margalit A (2014) Maturing, technology-based, born-global companies: Surviving through mergers and acquisitions. Manag Int Rev 54:421–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-014-0212-9

Andersson S, Evers N, Kuivalainen O (2014) International new ventures: rapid internationalization across different industry contexts. Eur Bus Rev 26:390–405

Arend RJ (2004) The definition of strategic liabilities, and their impact on firm performance. J Manag Stud 41:1003–1027. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2004.00464.x

Baier-Fuentes H, Merigó JM, Amorós JE, Gaviria-Marín M (2018) International entrepreneurship: a bibliometric overview. Int Entrep Manag J 15:385–429. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-017-0487-y

Barney J, Wright M, Ketchen DJ (2001) The resource-based view of the firm: Ten years after 1991. J Manage 27:625–641. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(01)00114-3

Barney JB (1991) Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. J. Manage. 17:99–120

Barney JB, Arikan AM (2001) The resource-based view: Origins and implications. In: Rabin J, Mille GJ, Hildreth WB (eds) Handbook of strategic management. Routledge, New-York, pp 124–188

Baronchelli G, Cassia F (2014) Exploring the antecedents of born-global companies’ international development. Int Entrep Manag J 10:67–79

Baum M, Schwens C, Kabst R (2015) A latent class analysis of small firms’ internationalization patterns. J World Bus 50:754–768

Bell J (1995) The internationalization of small computer software firms. Eur J Mark 29:60–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090569510097556

Bembom M, Schwens C (2018) The role of networks in early internationalizing firms: A systematic review and future research agenda. Eur Manag J 36:679–694. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.03.003

Bilkey WJ, Tesar G (1977) The export behavior of smaller-sized Wisconsin manufacturing firms. J Int Bus Stud 8:93–98. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490783

Bloodgood JM, Sapienza HJ, Almeida JG (1996) The internationalization of new high-potential U.S. ventures: Antecedents and outcomes. Entrep Theory Pract 20:61–76

Burton M, Sørensen JB, Beckman CM (2002) Coming from good stock: Career histories and new venture formation. In: Lounsbury M, Ventresca MJ (eds) Social Structure and Organizations Revisited. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp 229–262

Cannone G, Pisoni A, Onetti A (2014) Born global companies founded by young entrepreneurs. A multiple case study. Int J Entrep Innov Manag 18:210–232

Casillas JC, Acedo FJ (2013) Speed in the internationalization process of the firm. Int J Manag Rev 15:15–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00331.x

Cavusgil ST, Knight G (2015) The born global firm: An entrepreneurial and capabilities perspective on early and rapid internationalization. J Int Bus Stud 46:3–16. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.62

Chetty S, Campbell-Hunt C (2004) A strategic approach to internationalization: A traditional versus a “born-global” approach. J Int Mark 12:57–81. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.12.1.57.25651

Ciravegna L, Kuivalainen O, Kundu SK, Lopez LE (2018) The antecedents of early internationalization: A configurational perspective. Int Bus Rev 27:1200–1212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.05.002

Clelland IJ, Douglas TJ, Henderson DA (2006) Testing resource-based and industry factors in a multi-level model of competitive advantage creation. Acad Strateg Manag J 5:1–24

Colovic A, Lamotte O (2014) The role of formal industry clusters in the internationalization of new ventures. Eur Bus Rev 26:449–470

Coviello N (2015) Re-thinking research on born globals. J Int Bus Stud 46:17–26. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2014.59

Coviello N, McAuley A (1999) Internationalisation and the smaller firm: A review of contemporary empirical research. Manag Int Rev 39:223

Coviello N, Munro H (1997) Network relationships and the internationalisation process of small software firms. Int Bus Rev 6:361–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-5931(97)00010-3

Coviello NE, Cox MP (2006) The resource dynamics of international new venture networks. J Int Entrep 4:113–132

Crick D, Spence M (2005) The internationalisation of “high performing” UK high-tech SMEs: A study of planned and unplanned strategies. Int Bus Rev 14:167–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2004.04.007

Deligianni I, Voudouris I, Lioukas S (2015) Growth paths of small technology firms: The effects of different knowledge types over time. J World Bus 50:491–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2014.08.006

Denyer D, Tranfield D (2009) Producing a systematic review. In: The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Research Methods. SAGE Publications, Thousans Oaks, CA, pp 671–689

Dominguez N, Mayrhofer U (2017) Internationalization stages of traditional SMEs: Increasing, decreasing and re-increasing commitment to foreign markets. Int Bus Rev 26:1051–1063

Dominguez N, Mayrhofer U (2016) “Il n’est jamais trop tard pour entreprendre” : l’internationalisation des born-again globals. Rev l’Entrepreneuriat 15:61. https://doi.org/10.3917/entre.151.0061

Dutta DK (2013) Path dependence, VRIN resource endowments, and managers: towards an integration of resource-based theory and upper echelons theory. J Bus Theory Pract 1:109. https://doi.org/10.22158/jbtp.v1n1p109

Efrat K, Shoham A (2012) Born global firms: The differences between their short- and long-term performance drivers. J World Bus 47:675–685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2012.01.015

Ellwood P, Grimshaw P, Pandza K (2017) Accelerating the innovation process: A systematic review and realist synthesis of the research literature. Int J Manag Rev 19:510–530. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12108

Ennen E, Richter A (2010) The whole is more than the sum of its parts- or is it? A review of the empirical literature on complementarities in organizations. J Manage 36:207–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309350083

Evald MR, Klyver K, Christensen PR (2011) The effect of human capital, social capital, and perceptual values on nascent entrepreneurs’ export intentions. J Int Entrep 9:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-010-0069-3

Evers N (2010) Factors influencing the internationalisation of new ventures in the Irish aquaculture industry: An Exploratory Study. J Int Entrep 8:392–416

Evers N, Gliga G, Rialp-Criado A (2019) Strategic orientation pathways in international new ventures and born global firms—Towards a research agenda. J Int Entrep 17:287–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-019-00259-y

Fernhaber SA, Li D (2013) International exposure through network relationships: Implications for new venture internationalization. J Bus Ventur 28:316–334. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.002

Fletcher M, Harris S (2012) Knowledge acquisition for the internationalization of the smaller firm: Content and sources. Int Bus Rev 21:631–647

Foss NJ (1997) Resources and strategy: A brief overview of themes and contributions. In: A Resource-based view of the firm. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 5–17

Freeman S, Cavusgil ST (2007) Toward a Typology of Commitment States Among Managers of Born-Global Firms: A Study of Accelerated Internationalization. J Int Mark 15:1–40

Freeman S, Edwards R, Schroder B (2006) How Smaller Born-Global Firms Use Networks and Alliances to Overcome Constraints to Rapid Internationalization. J Int Mark 14:33–63. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.14.3.33

Freeman S, Hutchings K, Lazaris M, Zyngier S (2010) A model of rapid knowledge development: The smaller born-global firm. Int Bus Rev 19:70–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2009.09.004

Gabrielsson M, Gabrielsson P, Dimitratos P (2014) International Entrepreneurial Culture and Growth of International New Ventures. Manag Int Rev 54:292–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-014-0213-8

Gabrielsson M, Kirpalani VHM, Dimitratos P et al (2008) Born globals: Propositions to help advance the theory. Int Bus Rev 17:385–401

Gabrielsson P, Gabrielsson M (2013) A dynamic model of growth phases and survival in international business-to-business new ventures: The moderating effect of decision-making logic. Ind Mark Manag 42:1357–1373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2013.07.011

Greiner LE (1972) Evolution and revolution as organizations grow. Harv Bus Rev 76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.1997.00397.x

Hagen B, Zucchella A (2014) Born Global or Born to Run? The Long-Term Growth of Born Global Firms. Manag Int Rev 54:497–525. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11575-014-0214-7

Helfat CE, Peteraf MA (2003) The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strateg Manag J 24:997–1010. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.332

Hesping FH, Schiele H (2015) Purchasing strategy development: A multi-level review. J Purch Supply Manag 21:138–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pursup.2014.12.005

Higgins J, Green S (2011) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention. Wiley, New-York

Hitt MA, Bierman L, Uhlenbruck K, Shimizu K (2006) The importance of resources in the internationalization of professional service firms: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Acad Manag J 49:1137–1157. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.23478217

Ibeh K, Kasem L (2011) The network perspective and the internationalization of small and medium sized software firms from Syria. Ind Mark Manag 40:358–367

Jiang G, Kotabe M, Zhang F et al (2020) The determinants and performance of early internationalizing firms: A literature review and research agenda. Int Bus Rev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2019.101662

Johanson J, Vahlne J-E (1977) The Internationalization Process of the Firm—A Model of Knowledge Development and Increasing Foreign Market Commitments. Int Bus 8:23–32. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315199689-9

Johanson J, Vahlne J-EJE (2009) The Uppsala internationalization process model revisited: From liability of foreignness to liability of outsidership. J Int Bus Stud 40:1411–1431. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.24

Johanson M, Martín Martín O (2015) The incremental expansion of Born Internationals: A comparison of new and old Born Internationals. Int Bus Rev 24:476–496

Jones MV, Coviello N, Tang YK (2011) International entrepreneurship research (1989-2009): A domain ontology and thematic analysis. J Bus Ventur 26:632–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.04.001

Jones MV, Coviello NE (2005) Internationalisation: Conceptualising an entrepreneurial process of behaviour in time. J Int Bus Stud 36:284–303. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400138

Kellermanns F, Walter J, Crook TR et al (2016) The Resource-Based View in Entrepreneurship: A Content-Analytical Comparison of Researchers’ and Entrepreneurs’ Views. J Small Bus Manag 54:26–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12126

Keupp MM, Gassmann O (2009) The past and the future of international entrepreneurship: A review and suggestions for developing the field. J Manage 35:600–633. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308330558

Khan Z, Lew YK (2018) Post-entry survival of developing economy international new ventures: A dynamic capability perspective. Int Bus Rev 27:149–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.06.001

Kiss AN, Danis WM (2008) Country institutional context, social networks, and new venture internationalization speed. Eur Manag J 26:388–399

Knight GA, Madsen TK, Servais P (2004) An inquiry into born-global firms in Europe and the USA. Int Mark Rev 21:645–665

Kocak A, Abimbola T (2009) The effects of entrepreneurial marketing on born global performance. Int Mark Rev 26:439–452

Kumar N (2012) The Resource Dynamics of Early Internationalising Indian IT Firms. J Int Entrep 10:255–278

Laanti R, Gabrielsson M, Gabrielsson P (2007) The globalization strategies of business-to-business born global firms in the wireless technology industry. Ind Mark Manag 36:1104–1117

Laurell H, Achtenhagen L, Andersson S (2017) The Changing Role of Network Ties and Critical Capabilities in an International New Venture’s Early Development. Int Entrep Manag J 13:113–140

Li L, Qian G, Qian Z (2015) Speed of Internationalization: Mutual Effects of Individual- and Company- Level Antecedents. Glob Strateg J 5:303–320

Li Q, Deng P (2017) From international new ventures to MNCs: Crossing the chasm effect on internationalization paths. J Bus Res 70:92–100

Li T (2018) Internationalisation and its determinants: A hierarchical approach. Int Bus Rev 27:867–876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2018.01.009

Liao J, Welsch H, Stoica M (2003) Organizational Absorptive Capacity and Responsiveness: An Empirical Investigation of Growth-Oriented SMEs. Entrep Theory Pract 28:63–86

Lin S, Mercier-Suissa C, Salloum C (2016) The Chinese born globals of the Zhejiang Province: A study on the key factors for their rapid internationalization. J Int Entrep 14:75–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10843-016-0174-z

Lindstrand A, Melén S, Nordman ER (2011) Turning social capital into business: A study of the internationalization of biotech SMEs. Int Bus Rev 20:194–212