Abstract

This paper reviews the Banking and Other Financial Institutions Act (BOFIA) 2020 in Nigeria in the light of regulatory theories and extant empirical evidences, with a view to predicting its potential effects on financial system stability in Nigeria, domestic stakeholders and international investors. Our review shows that the new law attains a higher level of clarity in presentation of banking rules and regulations, tightens the incentive structures for compliance, widens regulatory breadth of financial sector coverage, penalises banks’ office holders more severely for regulatory breaches, emphasises banks’ compliance with prudential ratios, and improves banks’ disclosure. Empirical evidence in the literature that suggests these improvements may enhance financial system stability is corroborated by analytical statistics of banking sector data over 1983–2020 period. Our findings show that financial and prudential performance of Nigerian banks significantly improved after regulatory reforms of 2004 and 2009, suggesting that their codification in BOFIA 2020 has a strong potential to enhance financial system stability in Nigeria to the benefits of all stakeholders. These merits may, however, be undermined by inherent pitfalls in the Act such as reduction in the roles of other financial safety-net participants, negative market signals of such reduction, weak harmonisation with other Acts governing relevant banking issues, and concentration of supervisory power in a single regulatory authority with its inclination for regulatory capture, among others.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Effective banking regulation is vital to economic growth and development [3, 11, 17, 75] of any emerging market economies like Nigeria [48] where the banking sector plays a predominant role in the financial system [61]. The implications of a well-designed banking regulation are not particular to developing economies alone. Irrespective of whether their financial systems are bank-based or market driven, most developed economies like the USA, the UK, Japan and Germany benefit a great deal from banking regulation because of the role of banking sector in the payment system and their effects on economic performance [24, 39, 69].

Banking regulation as the set of laws governing the activities of banking industry participants, procedures for enforcement of the laws, and operationalisation of such procedures [6, 37, 47, 59] is a financial industry phenomenon often anchored by the relevant government agencies.Footnote 1 Its objectives range from promoting healthy competition, protecting market integrity, fostering depositor protection [55, 58, 67] reducing information asymmetry, to aligning the social cost of failure with private cost, with the sole target of engendering financial system stability and economic growth [6, 50, 54].

In Nigeria, a most notable banking regulation, coded into the law, is the Banking and Other Financial Institution Act (BOFIA). BOFIA 2020 is the latest Act that regulates banking in Nigeria, enacted on 13th October 2020 and signed into law by the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria on 17th November, 2020. The new Act appears overdue in the light of several amendments made to the its 1991 predecessor, and the age of the last preceding version, BOFIA 2004. The amendments reflect the dynamism of the Nigerian Banking System which plays a dominant role in the financial system service delivery. BOFIA 2020, like its previous editions, seeks to provide a suitable, contemporaneously relevant legal framework for banking activities in Nigeria. To achieve topical relevance and address the gaps in the previous versions, BOFIA 2020 extensively reviewed the existing legislations and introduces new ones deemed important. The Act is not only an overhauled version of the old BOFIAs, it can be said to represent some departure from the previous Acts.

This paper is motivated by three rationales. First, any policy—economic, financial or otherwise—needs to be evaluated for performance appraisal, and for the purpose of subsequent reviews and updates. The appraisal need not only be ex post: it can be ex ante or predictive as a means of proactively minimising errors and maximising the desirables, prior or during implementation. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is the first to present a comprehensive, not necessarily exhaustive, analysis of BOFIA 2020 for predictive purpose. On the basis of our analytical findings, and empirical evidence from other studies, this paper predicts the likely impact of the BOFIA 2020 on the economy, the Nigerian financial system and their stakeholders. Secondly, the stakeholders need to be informed of the potential impact of the legislation for timely feedback, and if possible early review, for optimisation of policy outcomes. In this light, this paper seeks to apprise stakeholders in the banking industry and other relevant sectors of the economy, with potential impact of BOFIA 2020. Third, any policy review is aided if there is a guidance. This paper aims at providing such guidance by highlighting the strengths and pitfalls of the Act, as well their implications for financial system stability, investors, other stakeholders, and the economy in general.

Our review shows that BOFIA 2020, compared to the previous editions, is more comprehensive in addressing contemporaneous developments in the banking sector that render the old BOFIAs inadequate. Some of its strengths include, but limited to, clarity of legislation, strengthened incentives for regulatory and prudential compliance, reduction of legal obstacles to failure resolution, internalisation of failure/distress resolution cost and improved disclosure, among others. Although the inherent pitfalls such as reduced roles of other safety-net participants and concentration of regulatory/supervisory power in a single authority may undermine these strengths, our findings show that BOFIA 2020 has a strong potential to have positive effects on financial system stability to the benefit of all stakeholders, given the improvement in the financial and prudential performance of Nigerian banks in the wake of regulatory reforms of 2004 and 2009, subsequently codified in BOFIA 2020.

This paper is organised into seven sections. Following the introduction, Stylised facts: BOFIA 2020 vs previous versions—an overview Section presents the stylised facts on BOFIA 2020. It highlights the structure of the Act in comparison with the old BOFIAs. Brief literature review Section presents a brief literature review where the theoretical expectation of banking regulations, as well as empirical effects of such legislations, are documented. The strengths and pitfalls of the Act are highlighted in BOFIA 2020: improvements, strength and pitfalls Section, while Banking sector reforms and banking sector performance: implications of codified reform-induced regulations in BOFIA 2020 for financial system stability Section provides empirical evidence on the potential effects of BOFIA 2020. Implications of BOFIA 2020 Section discusses the implications of BOFIA 2020 on the financial system and relevant stakeholders, while Sect. 7 rounds off with concluding remarks, discusses the summary and offers useful recommendations.

Stylised facts: BOFIA 2020 vs previous versions—an overview

BOFIA 2020 is a complete overhaul of its preceding versions (BOFIA 1991, as amended 1997, 1998, 1999 and 2002; as well as BOFIA 2004). The new Act is significantly different from the older Acts in many respects, both structurally and in regulatory perspectives.

Structurally, BOFIA 2020 comprises five chapters (Chapters A–E) arranged across nine parts (Parts I–IXFootnote 2). The preceding versions of the BOFIA are not, however, organised into Chapters but into three parts, Parts 1–III. The first six parts in BOFIA 2020, Part 1–VI (placed under Chapter A) are breakdowns of Part I in the BOFIA 1991 as amended and BOFIA 2004. Chapters B, C, D have a part each, namely Part VII, Part VIII and Part IX, respectively, with Chapter E having no Part designated. Part VII under Chapter B in BOFIA 2020 is equivalent to Part II in BOFIA 1991/2004, while BOFIA 2020 appears to have discarded Part III in in BOFIA 1991/2004.

Were the BOFIA 1991 as amended and BOFIA 2004 to be have been arranged in parts like BOFIA 2020, they would have had eight parts, with the last part (Miscellaneous and Supplementary) not represented in the latest BOFIA. Effectively, BOFIA 2020 includes additional three parts (Parts VIII and Part IX, comprising 11 sections and 28 sections, respectively, as well as undesignated/unnamed Part X under Chapter E with 31 sections). These inclusions, as well as moderation and significant adjustments to existing parts, represent an overhaul, a departure from the previous Acts.

Chapter A themed ‘Banks’ has six parts as indicated earlier, with Part I labelled ‘Licensing and Operation of Banks’. This part has 14 sections named with the same title as corresponding category in BOFIA 1991 and BOFIA 2004 which have 15 sections. BOFIA 2020 deleted Sect. 14 ‘non-compliance with capital ratio requirement’ as this has been subsumed as subsections 5–7 under Sect. 13 ‘minimum capital ratio requirement’.

Part II (Duties of Banks) in BOFIA 2020 has the same number of sections as the corresponding category in BOFIA 1991 and 2004, but the ‘display of interest rate’ in Sect. 23 in BOFIA 1991 and 2004 is replaced with ‘display of information’ in BOFIA 2020 (now in Sect. 22), suggesting a broader category of financial and nonfinancial data required to be displayed by banks under the new Act.

Part III (Books and Records of Account) in BOFIA 2020 has 11 sections, compared to 7 in the corresponding category ‘Books of Account’ in BOFIA 1991 and 2004. BOFIA 2020 retains the first six section of this category in the old/earlier versions (BOFIA 1991/2004), deletes the old Sect. 30 ‘relationship with specialised banks and financial houses’ and adds five new sections. Three of these additional sections were taken from the next category ‘Supervision’ in the old versions.

Part IV of the BOFIA 2020 labelled ‘Failing Banks and Rescue Tools’ is a total departure from the corresponding category in the old BOFIA ‘Supervision’. This change of name of the category is well placed because the category ‘Supervision’ in the old BOFIA does not fully reflect its content which largely focus on the resolution of failing banks. The category’s name derives only from the first three sections in its content which are not directly related to the bulk of the category’s content. That informed transfer of these sections to the preceding category and proper renaming of the category from ‘Supervision’ to ‘Failing Banks and Rescue Tools’ as Part IV in BOFIA 2020. Rather than focusing on liquidation processes such as licence revocation, sections in Part IV dwell largely on tools for rescuing failing banks such as ‘bail-in certificates’, as well as ‘moratorium and regulation on eligible bail-in instruments’ among others.

Part V, ‘General and Supplemental Provisions’ of BOFIA 2020 retains the name of the corresponding category in the old BOFIA, as well as the number of sections. It, however, takes out the section ‘power of the President to proscribe a trade union’ and insert ‘offences by companies, servants, agents’ taken from the next section ‘Miscellaneous’. It also broadens the scope of closure of banks during a strike to include ‘closure in the time of epidemic or pandemic’, in cognizance of the impacts of the unforeseen COVID-19 pandemic and possibility of similar events in the future.

Like Part V, Part VI ‘Miscellaneous’ of BOFIA retains the name of the corresponding category in BOFIA 1991/2004, but not the number of sections. Part VI has 8 sections, while the category in the old BOFIA has 10. The difference is accounted for by the transfer of the first section from the ‘Miscellaneous’ category to the preceding category, replacement of the section on ‘exception’ with ‘netting’ and elimination of the ‘application of NDIC Act, Cap N102’ section from Part VI BOFIA 2020 Act.

Chapter B of the BOFIA 2020 and the encapsulated Part VII replicates Part II of BOFIA 1991 and BOFIA 2004 without any significant changes. They only broaden application to banks to include financial institutions and specialised banks, change ‘application of the Act to other Financial Institutions’ to ‘application of Chapter A of the Act to specialised banks and other financial institutions’, and broaden the section ‘control of failing other institutions’ to ‘management and control of failing specialised banks and other financial institutions.

The new BOFIA significantly differs from the old versions in its legislation of new items that were not in the old BOFIA. Besides doing away with the Part III ‘Miscellaneous and Supplementary’ in the old BOFIA on the plausible accounts of obvious repetition, BOFIA 2020 introduces additional 70 sections, categorically distributed across Chapters C, D and E.

Chapter C, ‘General Regulatory Powers’ contains Part VIII ‘Other Regulatory Powers of the Banks’ which presents 11 sections on the Central Bank’s regulatory intervention on several issues that affects banks in contemporaneous world, ranging from money laundering, corporate governance, and cybersecurity, among others. Chapter D, ‘Resolution Fund’ and the embedded Part IX, ‘Resolution Fund and Resolution Tools’ contain 28 sections. They touch on the establishment of the resolution fund and resolution tools, and the management of these mechanism for financial system stability management.

Chapter E, ‘Special Tribunal for the Enforcement and Recovery of Eligible Loans’ is the last chapter of the Act. It comprises 31 sections, not placed under any designated Part, that border on judicial matters regarding failing bank resolution and other relevant matters.

Besides structural differences, BOFIA 2020 presents a paradigm shift in regulatory perspectives, especially in the aspect of failure resolution, when compared to BOFIA 1991 as amended, and BOFIA 2004. The scope of bank failure resolution in BOFIA 1991 as amended, and BOFIA 2004, is much larger than that of BOFIA 2020. While the earlier BOFIAs provide for bank failure resolution through the use of both open bank resolution (OBR) options and closed bank resolution (CBR) alternatives, BOFIA 2020 appears to lean more towards CBR.

Sections 36–38 of BOFIA 1991 as amended and BOFIA 2004 allows for the appointment of NDIC as an administrator/conservator, while Sects. 40 and 42 provide for the NDIC to serve as a liquidator of a failed Bank. Section 36 (Control of Failing Bank), Sect. 37 (Power over Significantly Under-Capitalized Bank) and Sect. 38 (Management of Failing Bank) allow NDIC as an administrator or conservator to use many rescuing tools to resolve a bank failure when the bank still has a chance to survive. These sections, which have been removed from BOFIA 2020, limit the scope of bank failure resolution in Nigeria, with possible implications for financial system stability.

The resolution approaches in BOFIA 1991 as amended and BOFIA 2004 are similar to those adopted in USA where the powers of FDIC as a conservator (as codified in United States Codes 1821 and such other Acts as Competitive Equality Banking Act (CEBA) of 1987) were as extensive. According to the Banking Acts in USA, the FDIC is empowered may take any necessary action to resolve a bank and this includes restoring solvency and soundness of a failing bank, ensuring continuity of banking function and services of a failing bank while preserving and conserving its assets [74]. This option may optimise benefits of failure resolution if the net present value of the bank is higher under conservatorship (when managed by an administrator) than in liquidation (when assets are sold off to defray liabilities). Outcomes of bank liquidation or any other CBR option may even be improved if preceded by conservatorship.

The resolution options provided for by the BOFIA 1991 as amended and BOFIA 2004 are also akin to special resolution regime (SRR) code of practice in the United Kingdom’s Banking Act of 2009 and its subsequent amendments. Under this Act, there are several stabilisation programmes designed to achieve the SRR objectives, and these include ensuring the continuity of critical banking functions/services, engendering financial system stability through promoting public confidence, and protecting public funds by minimising its use for resolutions among others. While stabilisation programs such as transfer to a private sector purchaser, transfer to a bridge entity, the asset management vehicle tool and transfer to temporary public sector ownership may be CBR, the use of bail-in tool and the financial assistance to a bank by Her Treasury may be OBR. All these options add more value to bank failure resolution aspect of regulation, than does by reliance on solely the liquidation.

Notwithstanding its benefits, conservatorship and provisional administration have been identified by the IMF to suffer certain weaknesses. These include possible abuse by powerful shareholders who use political pressure on authorities to adopt administrative order to delay eventual liquidation for personal benefits. Another abuse involves the use of tactics by a deposit insurer to avoid embarrassment when it does not have sufficient fund to pay off depositors. These are likely to exacerbate financial conditions of the banks and increase resolution costs to the public [74].

These drawbacks may explain why BOFIA 2020, in contrast to its predecessors, steers clear of conservatorship and provisional administration option and drop Sections 36, 37. 38. 40 and 42 in BOFIA 1991 as amended and BOFIA 2004. Unlike the USA’s Competitive Equality Banking Act of 1987 and United State Codes 1821 that allow the deposit insurer to explore varieties of resolution options including OBR to resolve failing banks, BOFIA 2020 restrict deposit insurer in Nigeria to only closure and liquidation as the only resolution approach to resolving a failing bank. Other resolution packages for failing banks open to the Central Bank in BOFIA 2020 are more of CBR such as use of bridge banks, with the exception of bail-in tools (e.g. bail-in certificates) that may be an OBR option.

Despite some difference from the UK’s regimes of bank resolution, BOFIA 2020 still aligns with UK’s Banking Act 2009 as amended in the use of bridge bank: the Central Bank of Nigeria, like the Bank of England, controls the resolution mechanism. BOFIA 2020 thus invariably differs from the Competitive Equality Banking Act of 1987 in USA that provides for the FDIC to establish a bridge bank when an FDIC-insured bank fails as contained in Sect. 503 subsection 1 of Competitive Equality Banking Act of 1987.

BOFIA 2020, BOFIA 1991 as amended, as well as BOFIA 2004 share a number of similarities, however. First, all these Acts adopt special resolution regimes where banking supervisors and regulatory authorities control the processes of resolving failing banks, rather than the judicial procedures where the court determines resolutions as governed the general insolvency law. These laws align with the paradigm shift in banking resolution from judicial control to bank supervisors’/government control of bank insolvency and pre-insolvency process [43]. This shift was necessitated by the peculiarity of banks and the implication of their failure for the economy [74, 81].

Second, BOFIA 2020, BOFIA 1991 as amended, as well as BOFIA 2004 make use of closure and liquidation of failing banks as a resolution option. In addition, while BOFIA 2020 retains the good aspects of the previous versions it still, albeit unwittingly, does not correct for certain weaknesses that characterise its predecessors. For instance, while the all Acts focus on long term financial stability in its resolution approaches to bank failures, none pays attention to the short-term welfare of the of depositors in terms access to their deposits, especially the insured funds, unlike the Bank Act of 1935 in USA. While this may be justified on their reliance on other extant regulations or Acts such as the Nigeria Deposit Insurance Acts (NDIC Decree 1988 and NDIC Act 2006), BOFIA as the Act that plays a sweeping oversight function on all matters in banking and other financial institutions should not overlook depositors’ access to their deposit in the advent of bank failure, given the implication of quick access to deposit on financial system stability. The Banking Act of 1935, an amendment to the Federal Reserve Act of 1914 as amended, provides for, in paragraph 6, subsection ‘l’’ of Sect. 12B, depositors to be reimbursed their insured depositor by the FDIC as soon as possible. BOFIA’s reliance on extant laws for this important provision, as well as others, is however apparently weakened by its arrogating overrule of other financial laws through its pervasive use of the clause ‘notwithstanding the provisions of any other enactment’ throughout the Act, as unrestrictedly flaunted in Sect. 53 subsection 1 of BOFIA 2020, for instance.

Brief literature review

Bank regulation has been described to have emerged as natural public reaction to market failures of private banking industry that arose from information asymmetry between informed bankers and less informed stakeholders [38]. If unregulated, the bankers as private economic agents may exploit the information asymmetry to pursue their interests at the expense of the depositors and other stakeholders and, by extension, the entire financial system. This would result in erosion of shareholders’ wealth, decline in household savings, collapse of public confidence and eventual systemic implosion of the financial system [67]. Thus, regulatory interventions are instituted to correct the engendered market failures [7, 67], protect the financial sector consumers and investors [55, 67] and promote financial system stability, with spill-over effects for macroeconomic performance [50, 54].

The public therefore institutionalises arrangements (financial safety-nets) and delegates sufficient authorities to agencies to operationalise the arrangements through appropriate legislations. These legislations constitute banking regulations. According to the [37, 47, 58], financial/banking regulation comprises a framework of rules and guidelines within which financial institutions’/banks’ activities, ranging from formation and operation to acquisitions, are located and controlled.

Regulation generally aims at coordinating the behaviour of an industry’s participants in a way that prioritises and optimises the public good above private gains [55, 70]. Banking regulation is not an exemption. Regulation of the banking industry is, however, more significant than many non-bank regulations [45], given the higher level of information asymmetries in banking sector [6, 38] and the significant importance of the sector to the economy [6]. Unsurprisingly, banking is thus one of the most regulated industries in the world [8, 9, 41].

The motivation for bank regulation may though be similar with other government regulations of product manufacturers, and there are greater emphasis, wider-spread attention and a more global concertation of efforts on bank regulation than others. This derives from the unique roles that banks play in economic and financial system development [45], ranging from providing a substantial proportion of external finance to firms around the world [16, 60], mobilising savings, facilitating trading and risk management, monitoring investment and exerting corporate finance and supporting payment system [34, 57, 67].

The effectiveness of bank regulation in achieving its objectives depends on, at least in part, monitoring the regulated entities for compliance. The monitoring of banks to ensure enforcement of the rules and regulation constitutes bank supervision [47]. While regulation and supervision are distinct, they serve complementary roles in achieving financial system stability objective [37], as one without the other may not achieve the desired objectives which include, but not limited to, minimisation of moral hazards and its price shock effects on the banking system, reduction of bank failure and distress [80], and fostering a healthy banking industry [20].

The complementarity of banking regulation and supervision is espoused by the Core Principles of Banking Supervision issued by the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision (BCBS). The Core Principles perceive regulation and supervision as two sides of same coin: both regulation and supervision are embedded in the framework for effective oversight of banks’ activities such that the desired public policy objectives, especially the financial system stability objective, are realised. The first thirteen of the Core Principles focus on issues relating to supervision, specifically the powers, responsibilities and functions of bank supervisors, while the last sixteen discuss prudential regulation for regulated banks [11].

Approaches to bank regulation and supervision approaches vary across different jurisdictions [12], depending on the financial and socio-political systems adopted [8, 68], cultural and religious background [79], legal origins and traditions [14, 56, 76], as well as geographical locations and colonisation histories [1, 2].

The approaches include regulation on capital adequacy [7, 22, 25, 70], activity restriction [32], entry restrictions [51, 67, 76], private sector monitoring [15, 16, 44], strong (concentrated) supervisory powers [7] personalising costs for non-compliance with regulation [23, 33, 36], and a hybrid of these. Though theoretical predictions regarding the effects of these approaches for bank performance and financial system stability are sometimes contradictory [16], empirical evidences on the effects of a regulatory approach are often clearer.

The regulatory theory predicts that tightened capital regulation in terms of increased capital adequacy requirement would reduce agency problem between banks and the depositors because increased capital at risk (for unexpected losses absorption) would reduce the ‘limited liability’ cover enjoyed by the shareholders [7]. According to this theory, it reduces moral hazard problems (excessive risk-taking behaviour) induced by deposit insurance and thus realigns the incentives of banks owners with depositors and creditors [22, 52]. Another stand of theoretical literature, however, argues that increased capital requirement may not reduce, but rather, increase risk-taking behaviour by banks [25, 53]. In addition to capital regulation, some supervisory policies hold banks’ directors liable to penalties for non-compliance with regulations. The interests are thus aligned, resulting in a greater stability of the financial system.

The general theory of government regulation, together with supervisory power view, posits that the approach of strengthening or increasing the power of regulatory and supervisory authorities would improve corporate governance of banks, enhance their performance and promote financial system stability in an environment where information and transaction of monitoring banks are so huge that the private sector lacks the incentives and capability to monitor and discipline banks [4, 16, 78]. The supervisory power view posits that increased supervisory power is very crucial to reducing moral hazard problems in a banking system characterised by weak official supervision (that makes complex banks difficult to monitor) and where the deposit insurance arrangement features unlimited coverage and risk-insensitive premium structure [7, 26]. Supervisory power view, however, emphasises that some government regulatory policies negatively interfere with the ability of the private agent to monitor banks [16] and exert an appropriate level of market discipline.

The regulatory capture view, however, expects otherwise, positing that strengthening the powers of supervisors in an environment with weak institutional arrangement induces abuse and corruption: the empowered supervisors often pursue private gains above the public goods [19, 76] by interfering with credit allocations mechanisms to re-channel credit to their politically connected allies [18, 42]. The view posits that banks may use political influence to pressure regulators for regulations that are beneficial to their interests, often at the expense of financial system stability. In contrast to private sector monitoring, concentrating supervisory powers in a single regulatory authority predisposes the banking system to the risk of regulatory capture [16]. Spreading supervisory powers over more than one regulatory authority, therefore, would reduce this risk.

The private empowerment view supports the private sector monitoring approach by espousing that bank regulatory and supervisory policies improve the incentives of the private sectors and their capabilities to monitor and discipline banks by minimising information cost through ensuring effective information disclosure [16, 44]. This view did not support the supervisory view which envisages that increased regulatory and supervisory power improves bank performance and system stability nor did it support the Pigouvian views that regulatory and supervisory power would resolve market failures [7, 76] such as monopoly exploitations, negative externalities, information asymmetries [7] and divergence between private cost and social costs. Rather, private empowerment view proffers solution to the regulatory capture problem by supporting the private sector monitoring arrangement [15].

Some theoretical arguments, according to [7], favour regulatory policies that limit the scope of activities banks engage in. Such activity restrictions (from participating in securities trading, insurance, real estate and acquisition of other nonfinancial firms) are deemed necessary to aid monitoring of banks whose size and complexity of activities, and the inherent information asymmetries, pose challenges to bank supervision. In addition, such big banks may exploit the political power derived from their size, wealth and position to hinder industry competition and selfishly influence policies. Counter arguments, however, posit that activity restrictions impede banks’ ability to harness economies and scale and scope [32], and thereby undermine their performance. Also, the information asymmetries inherent in large scope of activities are argued not to be so large to negatively interfere with system stability [7].

Theoretical predictions on the effects of entry restriction approach to bank regulation also diverge. Some arguments, on the one hand, support entry restriction, positing that restriction of entry into the banking industry promote financial system stability by enabling existing big banks to exploit their monopolistic power to harness their franchise value, thereby promoting prudent risk-taking behaviour [7, 51]. On the other hand, some argue that restricting entry harms the banking industry by impeding competition [7, 76].

There have been different theoretical arguments in favour and against personalising the cost for regulatory breaches against corporate directors. Those that oppose personalising the legal cost for regulatory breaches argue that reputational and market sanctions against erring directors are enough as deterrents [35]. They further contend that pressing legal charges against these directors would only discourage competent and ethical directors from serving Corporations [33] and limit their ability to take appropriate business risks [23] if they ever offer to serve. 36, however, argues in favour of personalised legal sanctions (financial, and or incarceration) against directors. He posits that they serve as effective deterrents for regulatory breaches, especially when there is a probability that misconduct may go undetected. In support of [21, 36] contends that reputational and market sanctions are not effective in preventing regulatory breaches.

Regulatory approaches though vary across jurisdictions, methodologies employed by regulatory authorities in regulating and supervising banks, and their objectives, are similar, if not entirely the same. These methodologies comprise, according to [47] public disclosures, non-public disclosure, on-site examination and off-site surveillance. Regulatory and supervisory authorities often require that banks disclose pertinent information, publicly and non-public.

Public disclosure requires that banks’ statements of financial performance are verified and certified by appointed auditors. This type of disclosure may be motivated by the need to satisfy stakeholders and enjoys their support and avoid sanction/discipline for non-performance. It may thus be deemed self-regulation, though compliance with financial reporting and their standards may be stipulated by regulatory authorities. Non-public disclosure involves rendering of returns to regulatory authorities which entails full disclosure of all relevant financial data for regulatory and supervisory purposes. In addition to analysing returns rendered by banks in an off-site surveillance, regulators and supervisors often visit regulated banks to obtain data that to complement findings from off-site surveillance.

There are documented empirical evidences on the effects of different approaches to regulation and supervision on bank performance in particular, and banking/financial system stability in general. Though theoretical predictions may differ on the effects of a particular approach to regulation, empirical evidences appear to often agree on the impact of a regulatory approach on bank performance and system stability.

Many empirical studies establish that regulating banking sector capitalisation has significant effects on bank performance and efficiency, and therefore banking sector development. Most of these studies show that tight capital regulation, or increase in capital adequacy requirements, improve banking sector performance and development. [29], as well as [10] find that increasing capital requirement improves bank efficiency, while [7] documents that capital stringency (increase in capital requirements) positively affect bank development, improve bank stability by significantly reducing incidence of non-performing loans, and hence reduce the likelihood of bank crises. Reference [63], however, documents that capital requirement stringency undermined banks’ financial performance.

The effects of capital stringency on bank development and bank crisis reduction in [7] are though not robust to model control for other supervisory and regulatory policies, they are found to be significant, as corroborated by findings from other studies. [30, 31] find that stringent capital regulation is negatively correlated with bank crises, as countries that have witnessed crises tend to have had less stringent definition of capital and had allowed more discretion in how banks compute capital requirement and ratios. This nexus is corroborated by [62] finding that higher capital requirements reduce bank failure rates.

Private monitoring (which entails financial information disclosure, external audit performance, and compliance with accounting standards) has though been noted to negatively correlate with capital stringency, strengthened bank governance and resolution regime [30], it has been established to improve bank development by reducing non-performing loans [7], increase bank efficiency [9], improve risk management [63], and, by reducing regulation-induced corruption in bank lending, raise integrity of financial intermediation in countries with sound legal institutions [16]. It, however, poses a burden on banks through reducing net interest margin and increasing overhead cost [7] and may thus lead to loss of operational efficiency [29]. Private sector monitoring of banks has, however, been found to have no impact on the likelihood of banking crises [7].

The extent, strength or concentration of regulatory powers in a regulatory or supervisory authority have been documented to have diverse impacts on banking industry performance, efficiency and development. Reference [7] finds that concentration of supervisory power in a regulatory authority did not lead to improvement in bank efficiency, nor did it lead to reduction in non-performing loans. Reference [62] finds that suspension rate (bank failure) in US counties where a regulator/supervisor has the sole licensing authority is higher than where the licensing is subject to second-layer authorisation or where licensing power is shared. Reference [62]’s findings establish that concentration of supervisory power hinder banking sector development by having the potential to destabilise the banking sector through corruptive practices.

Concentration of regulatory powers for monitoring, disciplining, and influencing banks in a single authority, unlike private sector monitoring, has been established by 16 to lead to corruption lending as regulators induce banks to channel credits to politically connected parties, thereby worsening the integrity of the financial intermediation role of the banking system. On the other hand, independence of supervisory power from government mitigates adverse consequences of powerful supervision [15]. Similarly, [62] posits that granting the supervisor the sole authority to liquidate banks without having a court to appoint a receiver significantly reduce bank failure. [9, 29], however, find that strengthened official supervisory power enhance bank efficiency by reducing financial distress, agency problem and market power abuse [9], albeit only in countries with independent supervisory authorities [9].

Restriction on entry into the bank industry by either the domestic or foreign firms has been found to increase overhead cost, induce bank fragility and increase the likelihood of banking crises [7]. Also, [41] find that entry restriction is associated with higher cost of credit, lower access to credit but lower level of non-performing loans. These findings show that entry restriction lead to lower level of bank development and performance [7]. These negative effects arose because entry restriction impedes competition and thus hinders banking sector efficiency [9].

Similarly, restriction on the scope of business activities of a bank has been found to significantly affect bank development. [9, 29] establish that restriction on bank activities impedes banks’ operational efficiency [7] had, however, found that the negative effects often associated with scope restriction were not robust to the inclusion of other (control) variables. [62] established that restriction on bank branching extends to activity restriction and limitation to portfolio diversification, leading to increased rate of failure. However, [31, 32] findings suggest a link between banking crises and activity restrictions as countries that experienced bank crises had imposed fewer restriction on bank activities.

BOFIA 2020: improvements, strength and pitfalls

BOFIA 2020 internalises significant changes from its previous versions in many respects. The structure of the new regulation has changed, while the scope of operation is broadened. These changes are associated with improvements in most of its provisions, suggesting that the new law is strengthened to achieve its public policy objectives. These feats are, however, beclouded with some inherent pitfalls.

As discussed under Sect. 2 of this paper, BOFIA 2020 registered a number of improvements over its previous versions, structurally, conceptually and in regulatory coverage. First, it classifies all the sections under a named and number parts, and appropriately categorises these parts under relevant chapters. This gives the new Act tractability as readers are able to navigate the section and locate them more easily.

Second, it rearranges some sections and place them where they more appropriately belong. For instance, it removes the first three sections of the category ‘supervision’ and place them in the preceding section where they appear to fit better. Third, categories/parts are more appropriately named such that they reflect the sections thereunder.

In addition, the new BOFIA introduces regulation on matters that are pertinent to the banking system stability such as the resolution funds and tools, contemporaneous and emerging issues including, but not limited, to money laundering and terrorism, corporate governance and cybersecurity, as well as important judicial matter that affect the very root of problems and dispute resolutions in the banking system.

The strength

BOFIA 2020 was enacted to improve banking system regulation in Nigeria. Besides the structural improvement, the new law exhibits strengths in many respects.

Clarity of rules and regulations

Most of the sections in BOFIA 2020 are presented in a clearer, simpler and reader friendly sentences. The new Act also attempts to clarify concepts to circumvent ambiguity and drive home the communication of matters under discussion for better understanding. For instance, BOFIA 2020 add three more subsections 3–5 to provide clarifying information on key concepts addressed in Sect. 2 ‘Banking Business’. BOFIA 1991 and 2004 did not state what ‘banking business’ means, but BOFIA 2020 does in subsection 5 where it describes banking business as ‘receiving deposit from the public as a main feature of the business or issuance of financial instruments in consideration for deposit repayment’. Also, subsection 3 clarifies the person deemed to have conducted a banking business (not described in the old BOFIA versions) to include not only a corporate body but also its promoters, directors, managers or any other officers in charge of the affairs of the body.

This clarification approach runs through the new Act, ensuring that conceptual issues are elucidated. Such issues are expatiated when necessary, and itemised for emphasis and clarity. Definitions are also provided, where hitherto absent, to ensure that users of the Act, or actors to whom the Act relates, have unambiguous understanding of the issues. For example, BOFIA 2020 Section 8 subsection 4 explicitly defines ‘offshore banking’ with the aim of forestalling ambiguity. Including such a definition in the new BOFIA, where absent from old versions, has aided clarity and circumvented fluidity of conceptualisation and interpretation.

Another clarity-enhancing approach taken by BOFIA 2020 is broadening the scope of application of its clauses or sections, and describing larger set of circumstances that apply or may apply to use or interpretation of the Act. For instance, while Section 12 ‘revocation of banking licence’ in BOFIA-1991 and 2004 only has 1 subsection, the same section has 6 subsections which describe various issues that relate, or may relate, to banking licence revocation.

Strengthened incentive mechanism for compliance

BOFIA 2020 expands the scope of punitive measures for regulatory breaches and itemises them for emphasis and clarity. In addition, regulatory requirements are elaborated for better understanding such that banks have no rooms to evade compliance. The Act also provides incentives to discourage non-compliance.

Section 2 subsection 2, ‘banking business’ in BOFIA 2020 for instance itemises 4 punitive measures for breaching the clause, whereas relevant sections in BOFIA 1991 and 2004 are not as explicit. Besides improving clarity, BOFIA 2020 increases the number of punitive measures to strengthen incentive for compliance.

Punitive measures are also made stricter in some ways. The monetary values of the fines are raised. For instance, the regulatory fines for breaching Sect. 2, ‘Banking business’, were increased from N2 million in BOFIA 1991 and 2004 to N50 million in BOFIA 2020. The increase was to enhance deterrence as N2 million may not serve this purpose in 2020 as it did in 1999 due to inflationary dilution. However, while N50 million fine in BOFIA 2020 may not be as effective a deterrent in real time as N2 million in 1991, it is more effective than N2 million fine in BOFIA 2004.Footnote 3

Another incentive mechanism introduced by BOFIA 2020 to improve regulatory compliance is the personalised penalty for directors/promoter/managers of any banking entity which fails to comply with the regulatory requirements of the new Act. Sections 5(6), 8(6), 16(2), 17(12), 19(10), 27(3) 49, 50, 59(4) of BOFIA 2020, among others, impose financial or nonfinancial penalties (incarceration) or both on directors/managers/or promoter for breaching pertinent sections of the Act. These penalties are in addition to the financial fines imposed on the financial institution in breach of regulation. These personalised penalties are aimed at ensuring that decision makers superintending the affairs of the regulated entities see to compliance or face the wrath of law.

Scope of supervision and contemporaneous regulation

The banking industry and the financial system in Nigeria have advanced over the years, and the number and types of financial institutions have tremendously changed. Therefore, BOFIA 1991 as amended and BOFIA 2004 may not be effective in regulating these institutions and the dynamics of financial transactions. BOFIA 2020 thus comes in handy in providing necessary regulation of these institutions.

Several sections of BOFIA 2020 extend regulation to Non-Interest Banks, unlike the BOFIA 1991 as amended and BOFIA 2004 which predated Non-Interest Banks. Pertinent regulatory issues for non-interest banks covered by the Act range from application of banking licence [Sect. 3(1(d))], investment and release of prescribed minimum share capital [Sect. 4(1)], minimum holding of cash reserves [Sect. 14(1)], publication of consolidated statement [Sect. 25], management and control of failing specialised banks [Sect. 61], among others.

Banking system shield against possible International Financial Malpractices

BOFIA 2020 strengthens the protection of the banking system in a way that the previous Acts did not. It includes, as part of the regulations on licence issuance in Sect. 3, a subsection that offers protection for the Nigerian banking system against a potential avenue for international financial malpractices. Section 3(5) stipulates that a foreign bank or entity without a physical presence in its country of incorporation, or licensed in its country of incorporation and not affiliated to a financial services group that is subject to effective consolidated supervision shall not be permitted. The Act also disallows Nigerian banks to establish or continue any relationship with such a bank.

This enactment is aimed at protecting the banking system, especially the local residents from possible malpractices from the international space that may be difficult to trace, control and check. The Act and its objective are similar to other countries’ (e.g. Hong Kong) regulation of international virtual banks’ operations in their country (see [72].

Stronger commitment to prudential ratios

Compliance with the prudential ratios, especially the capita adequacy ratio, is emphasised in Sect. 12(1 h) which specifies noncompliance as punishable with licence revocation. Revocation of the operating licence appears to be the greatest sanction for a regulatory breach. Thus, including breach of prudential ratio as part of condition for licence revocation emphasises the sanctity BOFIA 2020 attaches with prudential ratio compliance.

The commitment of the Act to ensuring compliance to prudential ratios are evidenced in Sects. 13(5)(6) and 16(1c) which impose restrictions on bank activities for failure to comply, as well as in Sect. 16(2) that penalises the directors of a bank for breaching prudential regulations. The importance ascribed to capital adequacy ratio is also reflected in Sect. 13(3) that empowers the CBN to require a bank hold additional capital as a means of ensuring that the bank does not slip below the prudential thresholds.

Minimising legal obstacles to failure resolution

Section 13(3–5) reduces the time period within which the licence revocation of nay bank may be challenged in court of law to 30 days. The reduction is to ensure that the process of resolving a bank failure is not unnecessarily lengthened, such as to prevent certain individuals from abusing legal machinery to slow down failure resolution process.

Improved disclosure

Banks and other financial institutions are required by BOFIA 2020 to disclose more information to the pubic beyond the few existing financial data displays required by BOFIA 1991 and 2004. In addition to the lending and deposit rates that the old BOFIAs require banks to displays at their offices, BOFIA 2020 in Sect. 22 (1b–f) mandates banks to display such other information as their obligations to report transactions above limits stipulated in ATML/CFT guideline to Nigeria Financial Intelligence Unit, foreign exchange rate, certified true copy of certificate of incorporation, and abridged version of last audited accounts.

Disclosure is also strengthened in many ways by BOFIA 2020. First, it reduces the time that banks and other financial institutions render regulatory returns to CBN to 5 days after the end of the month from 28 days allowed in BOFIA 1991 and 2004. The long period allowed by the old BOFIA is no longer necessary in the current digital age.

In addition, Sect. 26(1) mandates banks and other financial institutions to forward to the CB for approval their financial statement no later than 3 months after the end of the financial year, unlike the 4 months granted by BOFIA 1991 and 2004. In addition, Sect. 26(2) stipulates that banks and other financial institutions should have the financial statements (statement of financial position, the balance sheet, and statement of profit and loss and other comprehensive income) published in 2 national daily newspapers no later than 7 days after CBN’s approval. This contrasts with BOFIA 1991 and 2004 which allows publication in only one national daily without any stipulated timeline.

Internalising failure resolution cost

One of the greatest strengths of BOFIA 2020 is that it attempts to shift the cost of resolving bank failure or distress from tax payers to shareholders and other direct beneficiaries of banks’ profits or business. This achievement is realised through two major regulations: use of bail in certificates and constitution of resolution fund and resolution tools.

Sections 37–39 highlight the use of bail-in certificates as it relates to use of eligible instruments that will be determined post ante, as well as circumstances and conditions underlying the use of rescue tools in resolving failing banks. The sections provide for conversion of eligible instruments (issued by the bank in the course of business) into a form that would be used in rescuing (recapitalising) a failing bank. This type of rescue strategy internalises the cost of resolving a bank’s distress or failure in its operations. Also, Sect. 39(2) states that the CBN may require banks and other financial institutions to ensure that parties to the contracts governing eligible financial instruments agree to be bound by the contract provision: that the instruments would be subject to terms of bail-in certificate issued by the CBN.

Sections 74–80 provide for establishment of banking sector resolution fund that would be used to defray the cost of resolving distress or failure of any bank or other financial instruments. Section 78 highlights the bridge bank option for which use the fund would be used. The resolution fund would be funded from annual contributions by the CBN (N10 billion), NDIC (N4 billion) and every bank, specialised bank and other financial institution (an amount equal to 10 basis points of its total assets).

Pitfalls

The giant strides taken by BOFIA 2020 at improving the banking sector regulation notwithstanding, it suffers from a number of pitfalls that may undermine its effectiveness and potential to realise its goals. Some of these shortcomings are discussed hereinafter.

Reduction in the roles of other safety net participants

Safety net participants are non-profit entities, mostly regulatory bodies and often government-related entities, whose role in a system primarily focuses on engendering financial system stability and promoting the interest of relevant stakeholders. While financial safety net participants are sometimes broadly described to include all financial institutions, and even depositors and creditors that provide liquidity [13], they are more closely conceptualised to comprise government-related financial-sector regulatory authorities and their mandates [28, 40, 73].

Besides other components of financial safety net participants such as prudential regulation and supervision, as well as lender of the last resort function of the Central Bank [ 65, 73], deposit insurance is, according to [13], clearly the most recognised component of the financial safety net because of its role in sustaining public confidence in banking system through discouraging liquidity panics and preventing bank runs. According to [40], DIS contributes to financial system stability by assuaging financial crises and supports economic stability by reducing the number and amplitude of economic contractions in the last several decades.

These highlighted importance and contribution of deposit insurance notwithstanding, BOFIA 2020 appears to downplay the role of deposit insurance in financial safety-net management in Nigeria by expunging from BOFIA 1991 as amended, and BOFIA 2004 Sects. 36–42 of the Acts which provide for deposit insurance administrator in Nigeria, the NDIC, to play its natural role in the financial safety-net arrangements and banking system stability functions entrenched within a whole deposit insurance design.

Section 36 of BOFIA 1991, 2004 stated that the CBN may turn over the control and management of a failing bank to the NDIC on terms that CBN stipulated over time. Section 37 conferred on NDIC the power to take resolution actions on a failing bank that came under its control through application of Sect. 36. Such actions included requesting the failing bank to submit recapitalisation plan, prohibiting the bank from credit activities or capital expenditures without NDIC approval. With the provision of Sect. 38, the NDIC had the power to remain the manager of the failing bank for the length of time determined by the CBN. According to Sect. 39, NDIC had a duty to advise CBN to revoke the licence of a failing bank under its control when deemed necessary. Section 40 required that the NDIC apply to the Federal High court to wind-up a bank with revoked licence, while Sect. 41 prohibits legal action against a failing bank under NDIC control. Section 42 required NDIC to render returns on the CBN for which NDIC was acting as the liquidator.

The removal of these sections from BOFIA 2020 seems to be in contradiction to the Basel’s Core Principles of Banking Supervision by which the quality of the system of bank supervision is gauged. Principle 1, ‘Responsibilities, Objectives and Powers’ states there must be a legal framework that provide each authority involved in bank supervision with legal power to authorise banks, conduct ongoing supervision, address compliance with laws, and undertake timely corrective actions to address safety and soundness concerns. Principle 3, ‘Cooperation and Collaboration’ posits that the legal framework allows for cooperation and collaboration with relevant domestic authorities and foreign supervisors.

The word ‘each’ in Principle 1 connotes that the banking sector supervisory system naturally comprises more than one authority, for which there must be appropriate legal power to conduct its supervisory activities according to its mandate, as allowed by the legal framework. IADI Core Principles of Effective Deposit Insurance state in its Principle 2 ‘Mandate and Powers’ that such mandate (which ranges from ‘pay-box’ to ‘risk minimiser’ mandate) and power to execute it must be entrenched in the legal framework. The NDIC Act 2006, as part of the legal framework indicates in Sects. 26 to 42 that the NDIC has a ‘risk minimiser’ mandate; and this mandate is consistent with the responsibility, objectives and power that Sect. 1 of the Core Principles of Banking Supervisions stipulates that each authority in a supervisory system should have.

Regulatory power concentration

By reducing the roles of other members of the financial safety net participants, BOFIA 2020 indirectly increases concentration of regulatory and supervisory power in the CBN. Section 34(2) of BOFIA 2020 specifically allocates the power to undertake resolution of a failing bank through prohibition of lending, payment suspension, removal of director or any other officer of the bank. This function or power was exclusive to NDIC under Sect. 37 of BOFIA 1991 as amended and BOFIA 2004, once it was conferred the power to control a failing bank under Sect. 36 of BOFIA 1991 and 2004.

Section 36 of BOFIA 2020 requires relevant agencies including the Federal Ministry of Finance, Budget and National Planning (FMFBNP), the NDIC, the Corporate Affairs Commission (CAC), Federal Inland Revenue Services (FIRS) to cooperate with the CBN in banking resolution activities. This regulation connotes unidirectional flow of cooperation, and not bidirectional as may be conceived in Principle 3, ‘Cooperation and Collaboration’ of the Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision. Besides, the section also suggests that the sole responsibilities and powers of bank resolution lie with the CBN, while other ‘authorities’ are merely required to cooperate and participate in the resolution process as directed by the CBN. This against contradicts Principle 1 of the Core Principles for Effective Banking Supervision. Section 36 of BOFIA 2020 may thus generally be conceived to concentrate supervisory powers in the CBN by reallocating the powers of these authorities (and other financial safety net participants) to the apex bank.

Duplication of resolution cost/function

Sections 74–101 of BOFIA 2020 provide for the establishment of resolution funds and resolution tools, its administration and other pertinent issues. The CBN and NDIC are to annually contribute N10 billion and N4 billion, respectively, while each bank is to contribute an amount equal to 10 basis points of its total assets. This fund is to be used to defray the cost the Bridge Bank and any other resolution options.

Bridge Bank as a resolution option was provided for by the NDIC Act, one of the legal framework governing banking supervision in Nigeria. Thus, creation of resolution fund for this purpose may be deemed as duplicating this function. The administration of this resolution options is funded, at least in part, by the Deposit Insurance Fund accumulated from premiums paid by banks and returns on the invested funds. Therefore, the requirement for banks’ contribution to the fund for same function may appear to increase resolution cost borne by banks.

Also, NDIC’s contribution to the resolution fund eventually pass through to banks in a plausible, though unlikely, situation where the contribution makes its resources insufficient to give financial assistance to ailing insured institutions and discharge its other functions, and the Corporation had to require banks to pay special contribution in addition to the usual premium, as allowed by Sect. 17(5) of the NDIC Act. This may increase the burden of resolution cost on the banks.

While this fund may be necessary to cope with any increase in the cost of bridge bank resolution option, and to internalise the cost of failure to the banks, its invariance with the risks undertaken by the banks (as indicated by the flat charge on total assets of individual banks) may further exacerbate moral hazard effects of bank regulations in Nigeria.

Weak or lack of harmonisation with other relevant acts

BOFIA 2020, like its predecessors, fails to harmonise with other relevant laws that govern the conduct of, and resolution of matter and issues in, banks and other financial institutions, unlike the USA’s Federal Reserve Act 1914 as amended, United Kingdom’s Financial Services and Market Act of 2000 and the Banking Act of 2009 of the UK as amended.

These foreign Acts governing financial matters are amended to harmonise the regulations by supervisory and regulatory authorities with those of the apex monetary agency in their countries. For instance, the Banking Act of 1935 is an amendment of the USA’s Federal Reserve Act 1914 to harmonise the operations and regulations of the FDIC (a supervisory and regulatory authority of the banking system in US) with those of the Office of the Comptroller of Currency, Federal Reserve Banks and other regulatory authorities in USA.

Similarly, the Financial Services and Market Act of 2000 in the UK is so enacted as to delineate the duties of various regulators as a means to harmonising their operations and regulations. Also, the Banking Act of 2009 of the UK as amended recognises the role of various financial regulatory authorities such as the Bank of England, the Financial Conduct Authority, The Prudential Regulation Authority, and Her Majesty Treasury, as well as such other financial safety net participants as the Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) in complementarily engendering the financial system stability in UK. In addition, Sect. 7(3), Sect. 8 (2) and Sect. 9 (4) of the UK Banking Act of 2009 stipulate that regulatory authorities in UK, namely, the Bank of England, Her Majesty’s Treasury and the FSA (now the FCA and PRA), must consult each other in determining and applying resolution tools to failing banks.

Harmonisation of financial rules and regulation in financial Acts obviates chaotic conflicts in financial regulations contained in various promulgations that prepares the grounds for exploitable loopholes and regulatory arbitrage. Such developments that harmonisation forestalls are inimical to financial system stability. The failure of BOFIA should harmonise with other Acts, rather than overriding their provisions.

Banking sector reforms and banking sector performance: implications of codified reform-induced regulations in BOFIA 2020 for financial system stability

This section provides analytical evidence on the effects of BOFIA 2020 for financial system stability in Nigeria. Using ex post analysis of banking rules and regulations associated with reforms to determine their effects on financials and prudential performance of commercial banks, this study extends that BOFIA 2020, a codification of such regulation, would strengthen, and not detract from, the impact of such reforms-associated regulation.

The ex post analysis comprises simple statistical comparison of banking performance indicators before and after the 2004 and 2009 reforms using the test of means and variance, as well as regression analysis that tests for the impact of regulatory reforms on a subset of financial and prudential indicators using a dummy variable.

Methodology

Test of two means and variances

This study compares the means and variances of commercial banks’ financial and prudential indicators before and after banking reforms of 2004 and 2009. The data sample used contain data collected from NDIC Annual Reports from 1994 to 2020. The test of two means and variance follow previous studies in the literature (such as [76] on banking system performance around regulatory shifts occasioned by reforms.

The z statistics employed in the analysis provides a measure by which the statistical significance of the difference between the means of the performance indicators before and after a regulatory shift occurs, and hence helps in suggesting the possible effects of the shift on the behaviour of the performance indicators. The z statistics whose p-values indicate that the mean value of financial and regulatory performance indicators after regulatory shifts in the years 2004 and 2009 is statistically different from that before the shifts are given in Eqs. 1 and 2. Equations 3 and 4 present F test for equality of standard deviation for the data before and after regulatory shifts.

Regression analysis with regime shifts

A statistical difference by which the means of banking sector financial and prudential indicators after a regulatory shift is greater or lower than those before the shift may only suggest that difference is associated with the regime shift; it may not establish dependence or causality. A stronger statistical method to establish, at least, the dependence of the indicators’ post-reform behaviour on the regulatory reform is a regression analysis with regime shift. This analysis is highlighted in equations below:

The regression model 5 above may take the form of autoregressive distributed model of order 1, 0,0…0.0 (as shown in Eq. 6) to control for any autocorrelation within the model

Equation 6 is re-specified to test for regulatory shift of 2004 and 2009, as shown in Eqs. 7 and 8, respectively

where

\({y}_{t}\) = a 1 × 1 vector, and \({y}_{t}\) \(\in {Y}_{t}\)\({Y}_{t}=\left[{\mathrm{ROE}}_{t}, {\mathrm{ROA}}_{t}, \;{\mathrm{NPL}}_{t}, \; {\mathrm{CAR}}_{t}\right]\)\({X}_{t}=\left[{\mathrm{GDPCYCLE}}_{t}^{+}, \; {\mathrm{GDPCYCLE}}_{t}^{-}, \; {\mathrm{INF}}_{t}, \;{\mathrm{EXR}}_{t}, \;{\mathrm{NINT}}_{t}, {\mathrm{NFA}}_{t}\right]\)

\({\mathrm{ROE}}_{t}\)= Return on equity; \({\mathrm{ROA}}_{t}\)=Return on assets;\({\mathrm{NPL}}_{t}\)= Non-performing loan ratio, \({\mathrm{CAR}}_{t}\)= capital adequacy ratio; \({\mathrm{INF}}_{t}\)= inflation; \({\mathrm{EXR}}_{t}\)= exchange rate; \({\mathrm{GDPCYCLE}}_{t}^{+}\) = positive business cycle; \({\mathrm{GDPCYCLE}}_{t}^{-}\) = negative business cycle; \({\mathrm{NINT}}_{t}\)=net interest income; \({\mathrm{NFA}}_{t}\)=net financial account

where

all variables as earlier defined.

The use of regression analysis with regime shift to examine the role of banking reforms in banking sector performance follows [27]. Data used span 1983 to 2020 and were collected from [77]’s study (1983–1993) and from NDIC (1994–2020).

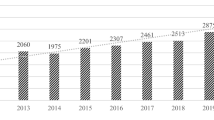

Findings

The means of most selected banking industry financial and regulatory indicators after a regulatory reform are statistically different from those before the banking reforms of 2004 and 2009.

Return on Equity (ROE) in the period after the banking reform of 2004 and 2009, on average, significantly underperformed that before the reform (as shown in Tables 1 and 2). Do these result show that the reform failed? Not necessarily. The banking reform of 2004 raised the minimum capital requirements for commercial banks from N2 billion to N25 billion [46]. Thus, equity (the denominator of the ratio) increased largely,Footnote 4 apparently more than did the returns. This does not, however, absolve the bank of inefficiency of maximising the output/profit from capital employed. While the decline may suggest operational inefficiency, the regulatory objective of having banks sufficiently capitalised was achieved, as indicated by increase in Capital to Earning Asset (CEA) after the banking reform of 2004. The slight, albeit statistically significant, decline after the banking reform of 2009 reflects an inherited capitalisation challenges which the reform targeted to resolve.

Similarly Return on Asset (ROA) is significantly lower and more volatile after the banking reform of 2004 (as shown in Table 1). This result may be explained by the nature of the minimum capitalisation reform and their effects on banking structure and operations. The reform led to several mergers and acquisitions and may have led to reduction in asset management efficiency that undermined returns. Also, the increased capital created the need for a corresponding increase in the size of asset. These may also directly reduce ROA, and indirectly through possible nascency of the banks’ experience at that time in managing huge magnitude of risk assets occasioned by the large multiple of capital enforced by the reform.Footnote 5 These developments may also, invariably, explain the behaviour of Return on Earning Assets (ROEA) before and after the two reforms. ROA, however, improved after the banking reform of 2009 that sought to resolve challenges undermining banking sector performance such as corporate governance failure, lack of investor (& management) sophistication, inadequate disclosure among others [71].

The banking reforms of 2004 and 2009 may though not appear to have contributed to the profitability of the Nigerian banks, they were obviously successful, given the significant improvement of Nigerian Banking Industry’s financial performance indicators that underpin financial system stability. Capital to Asset (CA), Capital to Loan (CL) and Capital to Earning Asset (CEA) all rose, significantly, after the banking sector capitalisation reform of 2004, signifying the efficiency of the reform at achieving its objective. Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR) was, however, lower, albeit insignificantly, after the 2004 reform, and that was reflective of some of other challenges that occurred much later. Post-2009 reform, CL’s average after the 2009 reform was also significantly higher. While CEA and CAR were lower after the 2009 reform, the CA’s average after the reform was not significantly different from its average before the reform. The behaviour of CAR, CEA and CL post-2009 reform was reflective of the vestige of the challenges that the 2009 reform aimed to resolve. Besides, capitalisation was not the primary focus of the 2009 reform, as was general resolution of problems undermining banking system stability.

Notwithstanding, indicators of financial intermediation (Loan to Deposit, LD; Loan to Assets, LA), indicators of short-term financial stability (Liquidity Ratio, LR) as well as indicator of long-term stability (solvency) and asset quality (Non-Performing Loan, NPL Ratio) improved significantly after the two banking sector reforms. LD and LA were significantly higher after the two reforms, indicating that banks granted more loans per unit of asset and liabilities under their management. The percentage of assets allocated to liquid investment, LR, was higher, thus enhancing the industry’s poise at meeting its short-term financial obligation to their customers and other creditors. In addition, non-performing loan as a ratio of total loan was significantly lower after the reform, suggesting improvement in asset quality that, in turn, enhanced solvency and long-run stability of the Nigerian Banking System.

The standard deviation (indicating the volatility) of the financial and prudential ratios, except for LA, were lower after the 2009 reforms, suggesting that the banking sector has been more stable after the reform. Where the standard deviation of most of the indicators was higher post-2004 reform, the p-values of the F-statistics (from the ratio of the standard deviation after and before the 2004 reform), and the insignificance of the statistics, show that volatility, which denotes banking system instability in Nigeria, was no greater after the reform.

Findings from regression analysis affirm that regulatory reforms are not merely associated with improvement in prudential performance of the Nigerian Banking sector. Corroborating the findings from the test of two means earlier, findings from the regression analysis (in Table 3) show that the banking reform of 2004 did not contribute to profitability of the Nigerian Industry, as indicated by negative and statistical insignificance of the regulatory regimes of 2004’s coefficients in ROE and ROA Eqs. 7ROE and 7ROA. This finding is supported by [63] which finds that capital stringency undermines banks’ financial performance. The financial performance of banks after the 2004 reform may be explained by the fact that reform focused more on prudential stability of the Nigerian banking system than it did on profitability.

Similarly, the 2004 banking reform did not improve asset quality performance by not significantly reducing non-performing loan (NPL) ratio (as shown in Table 4). This result did not support the findings by [7] that capital stringency reduces Non-Performing Loan. The 2004 reform, however, had positive, albeit insignificant, effects on capital adequacy ratio (CAR). These results arose from the regulatory focus of the reform: recapitalisation. The statistical insignificance of the reform’s effects on CAR is akin to findings from the ‘test of two means’ analysis and reflects the myriads of challenges that rocked the capital base of some banks. For instance, a few banks had negative shareholders’ funds in 2017 [64]Footnote 6 and that would invariably contribute to lower capital base post-2004 reform.

The banking reform of 2009 which addressed the challenges facing Nigerian banks more holistically had positive effects on their profitability. The regulatory reform of 2009 had a positive and statistically effect on ROE. The reform apparently did not detract from ROA, as its effects on ROA were positive, albeit insignificant. The banking reform of 2009 did not, however, improve the CAR; and that may stem from the fact that the reform had primary objective other than recapitalisation.

Notwithstanding, the reform very significantly reduce NPL, suggesting the effectiveness of the reform in resolving the challenges that dot the banking sector prior to the reform.

These findings suggest that the banking reform of 2009, which aimed at removing impediments to banking system financial and prudential performance, contributed to profitability and stability of the Nigerian Banking System.

Most other macroeconomic determinants of banks’ financial and prudential performance used as control variables contributed in explaining the behaviour of performance indicators, in conformity with a priori expectation. Negative business cycle which detract from firms’ profit reduced bank profitability (ROE and ROA). While its negative effect on NPL seems counterintuitive, negative business cycle actually corrected for exuberance in lending that occurred during the output boom (positive business cycle) when the restrictive rules guarding lending quality lax. Since banks tighten lending rules during negative business cycle, asset quality rises and NPL drops. In addition, interest rate (lending less deposit rate) which is expectedly boost interest income enhanced profitability.

Implications of BOFIA 2020

Empirical evidence of the effect of bank regulations on the financial/banking system as well as its stakeholders provides the avenues to gauge the potential implications of BOFIA 2020 on the stability of the Nigerian financial system, as well as welfare of its stakeholders. BOFIA 2020 codifies into law the banking rules and regulations introduced by the banking sector reforms of 2004 and 2009. It thus provides a legal framework that holistically addresses the challenges that those reforms sought to resolve. To the extent that those reforms improved the banking sector’s financial and prudential performance and promoted its long-term stability (as established in Sect. 5), BOFIA 2020, which codifies banking rules and regulations occasioned by the reforms, is set to further enhance the banking system financial performance, strengthen financial system stability, and by extension, promote the interest of stakeholders in the Nigerian financial system.

The following subsection highlights the details of the potential effects of BOFIA 2020, for which the empirical support is provided in Sect. 5.

Implications for financial system stability in Nigeria

BOFIA 2020 as a more comprehensive Act that adds several new regulations besides large revisions to many existing sections touch on financial system stability in Nigeria in several aspects.

First, the improved clarity of the new Act reduces room for misinterpretation, thus blocking the loopholes for perverse exploitation of the law. This would aid speedy adjudication of legal cases that impede bank resolution and liquidation process, and hence promote financial system stability. In addition, BOFIA 2020’s prescription for timely liquidation of failed banks whose licence has been revoked aims at preventing abuse of legal structures by unscrupulous market participants to slow down liquidation process. Timely resolution/liquidation of failed banks strengthens public confidence in the banking system, thus enhancing financial system stability.

Second, the tightened incentive structure for regulatory compliance has the potential to reduce probability, hence the frequency, of the malpractices in the banking sector. By personalising cost of breaching regulations, bank directors and manager would be committed to strengthening internal control system to minimise, if not prevent, regulatory breaches, and by extension occurrence of malpractices in Nigerian banks. Though these improvements in the banking regulations, BOFIA 2020 has addressed myriads of problems that threatened the banking systems in 2009, for which the 2009 reforms were implemented. The improved banking legislations in BOFIA 2020 would ex ante discourage abuse for which, according to [71], top executive of about eight banks had to be removed in the wake of the 2009 reforms.

Third, the increased scope of regulation by BOFIA 2020 to include such aspects of banking as non-interest banking has the potential to increase financial depth, coverage and inclusion. This would enhance financial sector development that would engender inclusive growth.

More importantly, the Act’s commitment to the sanctity of regulatory/prudential ratio in the form of raising the sanction for breaching to the level of licence revocation signals to the banking industry the importance of compliance. It is worth of note that increasing sanction for non-compliance regarding capital adequacy is part of its stringency measures. As BOFIA 2020 increases the stringency of capital adequacy ratio, it is also expected, as established in findings of empirical studies [see 30, 31], that financial system stability improves.

BOFIA 2020 is also expected to enhance financial system stability in Nigeria through its legislated support for improved disclosure. By ensuring that banks render returns earlier than allowed by older BOFIA, BOFIA 2020 allows the regulatory/supervisory authorities to detect and check unsafe and unsound banking practices and other events that may put financial system stability at risk.