Abstract

The impact of migration on the sizes, composition, and well-being of First Nations communities and the motivations that triggered such migrations have long been a topic of interest among researchers. Exploiting a new data source, linkages of consecutive censuses, this study aims to portray migration into and out of Indian reserves, with a focus on the Indigenous population. Between 2011 and 2016, migrations into and out of reserves resulted in net losses for reserves. These migratory losses, however, did not prevent the population on reserve to continue growing. From a socioeconomic point of view, migrations had a net positive impact on reserves by contributing to increase the proportions of individuals who are employed, with relatively high incomes or relatively high education. Looking at the determinants of migration, and taking advantage of a multilevel framework, it is found that migration into and out of reserves is multidimensional, being influenced by factors at both individual and community levels. Out-migration seems to be governed mainly by the propensity of individuals at certain stages of life to leave the reserve, permanently or not. In contrast, in-migration appears more influenced by reserves’ characteristics, and its prevalence varies greatly from one reserve to another.

Résumé

L’impact de la migration sur la taille, la composition et le bien-être des communautés des Premières Nations, ainsi que les motivations ayant entraîné ces migrations, sont depuis longtemps un sujet d’intérêt pour les chercheurs. Tirant parti d’une nouvelle source de données, soit les couplages de données entre des recensements consécutifs, cette étude vise à dresser un portrait des migrations en provenance et à destination des réserves indiennes, en mettant un accent particulier sur la population autochtone. Entre 2011 et 2016, les migrations en provenance et à destination des réserves ont entraîné des pertes nettes pour les réserves. Ces pertes migratoires n’ont cependant pas empêché la population des réserves de continuer de croître. D’un point de vue socio-économique, les migrations ont eu un impact net positif sur les réserves en contribuant à accroître la proportion d'individus ayant un emploi, des revenus relativement élevés ou un niveau de scolarité relativement élevé. En examinant les déterminants de la migration, et en prenant avantage d'une approche multi-niveaux, on constate que la migration en provenance et à destination des réserves est multidimensionnelle, étant influencée par des facteurs opérant à l’échelon individuel ainsi qu’à celui de la communauté. La migration de sortie semble principalement influencée par la propension des individus à quitter la réserve, de façon permanente ou non, à certaines étapes de leur vie. À l’inverse, la migration d'entrée semble davantage influencée par les caractéristiques des réserves, et sa prévalence varie beaucoup d’une réserve à une autre.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In past decades, results from censuses and the National Household Survey (NHS) have shown that migratory flows into and out of Indian reserves were contributing positively to the growth of these reserves, i.e., that they were experiencing positive net migration (Cooke and Penney 2019; Cooke and O’Sullivan 2015; Clatworthy and Norris 2007, 2014; Norris et al. 2004; Norris 1990, 1996, 1985).Footnote 1 This finding became accepted as a certitude as it was found again and again, from census to census. However, in a recent study based on newly available data linkages between censuses for the period from 2006 to 2016, Morency et al. (2021) found different patterns: Indian reserves in Canada had experienced negative net migration, which means that there were more reserve out-migrants than in-migrants during that period. This study also showed some of the limitations of using retrospective information about place of residence in the census and NHS to estimate migration flows into and out of Indian reserves, calling into question the precision of past estimates.

This paper follows the research initiated by Morency et al. (2021) in exploiting a new data source, linkages of consecutive censuses, to analyze migration into and from Indian reserves. A first goal is to provide a detailed portrait of the migrants who left or entered a reserve between 2011 and 2016, with a focus on the Indigenous population.Footnote 2 This analysis will improve understanding of how these entries and exits have contributed to modifying the growth and the composition of the population living on reserves in that period. This appears essential, particularly in light of the new results obtained from census linkages showing that most reserves recorded negative net migration. A second goal is to investigate the determinants of migrations of the Indigenous population into and out of Indian reserves. While this study is not about motivations of individuals for migrating per se, some inference can be made in light of the characteristics of migrants and those of reserves of origin and destination. In particular, it seems important to disentangle drivers operating at the individual level from those operating at the scale of the reserves.

The paper is structured in six distinct parts. Following this introduction, a succinct review of the literature is presented with regard to migration flows between Indian reserves and off-reserve areas. Next, research questions are presented, followed by a section in which concepts and definitions are established, and data sources and methods used in this paper are presented. Results are shown in the fifth section, following these lines: (1) a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of migrants into and out of reserves and (2) a multivariate analysis based on multilevel regression combining reserves as varying effects with other socioeconomic characteristics as constant effects. A discussion and conclusion follow in the sixth and seventh sections, respectively.

2 Short Review of Past Studies

Between 2001 and 2016, the population on reserves grew from 297,000Footnote 3 to 380,000 people. This represents an annual growth rate of 2.5%, which is close to twice the growth rate experienced in Canada over the same period (1.3%). A secular high fertility explains, in large part, this relatively high growth rate (Morency et al. 2018). Several past studies based on censuses and the NHS (which replaced the long-form census questionnaire in 2011) showed that positive internal migration also contributed to the population growth of reserves (Cooke and Penney 2019; Cooke and O’Sullivan 2015; Norris and Clatworthy 2011; Clatworthy and Norris 2007, 2014; Norris et al. 2004; Norris 1990, 1996, 1985), although these results seem to be largely caused by the limitations of using retrospective information for measuring migration flows from or toward reserves. Indeed, a recent study (Morency et al. 2021) using linkages between the 2011 Census and the 2016 Census (short-form questionnaire) and between the 2006 Census (short-form questionnaire) and the 2011 CensusFootnote 4 shows that, overall, reserves lost 33,000 individuals through internal migration between 2006 and 2016.

A key aspect of migration from and into reserves is its repetitive nature for a significant proportion of the migrants. There is indeed evidence of return migration or circular movement between reserves and urban areas (Cooke 1999; Cooke and Bélanger 2006; Irvine 2010). Results from the First Nations Regional Health Survey conducted in 2017 among people living in First Nations communities show that almost 60% of adults have, at one time or another, lived outside their community (First Nations Information Governance Centre 2018).

Several studies have examined the characteristics of migrants, either to describe the impact of migration on the population of reserves or to infer about migrants’ motivations. Age and sex patterns of migrants have been well documented. Among Registered Indians, females were found to have higher migration rates than males, the gap being more pronounced for out-migration and among youth and young adults (Clatworthy and Norris 2014). Overall, migration rates are lower among young children and are higher for young adults and then decline steadily thereafter (Clatworthy and Norris, 2007, 2014; Norris et al. 2004; Norris 1990, 1996, 1985). This is the typical age pattern of migration, a result relatively insensitive to the scale of the migration studied (Rogers and Castro 1981). This suggests that migrations from and toward reserves are strongly associated with events in the lifecycle of individuals, such as getting an education, searching for employment, or having a family (e.g., Amorevieta-Gentil et al. 2015; Sandefur and Wilbur 1981; Lee 1966). Similar findings have been observed for the Indigenous populations of Australia (Kinfu 2005; Taylor and Bell 1994).

Studies looking specifically at the motivations for migration tend to confirm these findings. These studies use either survey data or qualitative studies to probe respondents about the reasons why they moved to a reserve or left a reserve. Data from the 1991 Aboriginal Peoples Survey, a survey administered to individuals living on- or off-reserve who identified with their Aboriginal origins or were Registered Indians, show that the main motivations for moving were related to family and housing considerations (Clatworthy 1996; Clatworthy and Norris 2007). Family considerations were especially important for migration to reserves. Seeking a higher level of education was the primary reason for leaving a reserve (Clatworthy and Norris 2007). Data from the First Nations Regional Health Survey on people living in First Nations communities show that those who had left their communities did so mainly for reasons related to education and employment (FNIGC 2018). By contrast, the main reasons for coming back to the community were related to family and the connection to the community and home and, secondarily, job opportunities.

Although they lack the statistical power of surveys, qualitative studies may probe respondents outside of fixed categories and therefore uncover a wider and more profound array of motivations. Using semi-structured interviews conducted with 17 Registered Indians who had moved to the city of Winnipeg, Cooke and Bélanger (2006) found that employment was a key factor motivating migrations between reserves and cities. Results from a three-wave survey of individuals identifying as First Nations, Métis, or Inuit who had recently moved to Winnipeg (not necessarily from a reserve) show that the initial move to the city was motivated mainly by reasons related to family, employment, and education (Institute of Urban Studies 2004). However, housing issues had become a main motivation for those who moved between the first and the third waves of the survey. Globally, the survey exposed the significant struggles in securing shelter.

In the literature on migration, a typical distinction is made between individual determinants and macro-level variables referring to the characteristics of the geographical areas of origin and destination (Gardner 1981). Cooke and Bélanger (2006) suggest a conceptual framework that recognizes the interplay of several dimensions, such as the political, sociocultural, demographic, economic, and spatial contexts. The study highlights that migration is a complex process, influenced, facilitated, or hindered by a number of factors not only at the individual level, but also at the levels of family, community, or city. This is a recurrent theme in the literature. For example, past studies have highlighted the necessity to consider factors such as the influence of socioeconomic conditions prevailing in reserves (Frideres 1998; Newhouse 2003; Trovato et al. 1994), level of community well-being (Cooke and O’Sullivan 2015; Flanagan 2019; O’Sullivan and McHardy 2007), distance from an urban center (Clatworthy and Cooke 2001; Cooke 1999; Cooke and Bélanger 2006), level of economic performance and educational achievement (Cooke and O’Sullivan 2015), institutional completeness (i.e., the presence of administrative, educational, and medical institutions) (Gerber 1984), or population size (Gerber 1984). Other less tangible factors, such as cultural attachment and ties with the community, are also at play (e.g., Amorevieta-Gentil et al. 2015; Cooke 1999; Norris et al. 2004).

It is impossible to cover all aspects of migration from and into reserves highlighted in the literature in a reasonable space here, but this short summary shows that it is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon, calling for a comprehensive approach that encompasses factors at various levels. Readers may find more detailed accounts by Cooke (1999), Cooke and Bélanger (2006), Amorevieta-Gentil et al. (2015), and Quinless and Manmohan (2016), among others.

3 Research Questions and Focus of the Analysis

The objective is to provide a portrait of migration into and out of reserves and of the determinants of these migrations using the newly available linkage between the 2011 Census and the 2016 Census, and between the 2011 NHS and the 2016 Census. The analysis targets mainly the Indigenous population, implying that a fair number of movements—those made by non-Indigenous individuals—are simply not considered in the analysis; in fact, between 2011 and 2016, these movements represented 40.5% of migrations into a reserve and 20.7% of migrations from a reserve. However, a large part of these movements were concentrated in only a small number of reserves, most located in British Columbia, with relatively large non-Indigenous populations. In these reserves, non-Indigenous in-migrants were likely drawn by the availability of residential housing open to all, the existence of economic development projects, or other factors not typically available in most reserves. Moreover, the composition of migrants also differs greatly between Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations, suggesting different dynamics at play. In this context, the inclusion of the non-Indigenous population would provide a portrait that is not representative of the reserves overall, one that is biased by some large flows involving only a small number of reserves. Some results pertaining to the whole Canadian population are nevertheless shown in the first part of the analysis, where a broader portrait of migratory flows into and out of reserves is provided.

The study also focuses on the population aged 15 years and older. This choice was made because young children do not generally take part in the decision-making process surrounding migration and because several characteristics of interest for the analysis of migration are not available in the census for the population aged younger than 15 years old, especially those related to education, employment, and income.

The first part of this paper aims to provide a portrait of the migrants. Detailed statistics describing the flows of migrants from and into reserves, the net results of these flows, and the population living on-reserve are presented. This first section aims to answer two questions:

-

1.

How does migration affect the composition of the population of reserves?

-

2.

How do reserves differ in regard to their level of net migration?

A useful framework for studying migration, proposed by Lee (1966), conceptualizes the phenomenon as influenced by a combination of push and pull factors comprising characteristics of the place of origin and places of destination, personal factors, and intervening obstacles. This framework seems particularly appropriate given the insistence in the literature for the consideration of determinants of migration at both the level of individuals and the level of reserves. In practice, however, these factors are interrelated and often difficult to single out. In the second part of the analysis, an effort is made in this direction by adopting a multilevel analysis approach able to link individual factors and macro-level determinants in a specific manner (Massey 1990). More precisely, multilevel regression models were built to answer three further key questions in relation to the general objective of this paper:

-

3.

Are there differences in out-migration and in-migration rates between reserves?

-

4.

What are the characteristics of individuals associated with out-migration and in-migration?

-

5.

What are the characteristics of the reserves that are associated with out-migration and in-migration?

4 Concepts, Data, and Methods

4.1 Concepts and Definitions

In this paper, reserves are defined based on the definition of the 2016 Census. The places of residence in 2011 have been recoded to meet the 2016 definitions so that no migration is artificially induced by changes in the boundaries of geographic entities over time. Readers interested in knowing more about the definitions are asked to refer to the 2016 Census of Population dictionary (Statistics Canada 2018a). Unless otherwise indicated, the analysis covers 533 of the 984 census subdivisions (CSDs) associated with the on-reserve population. Excluded reserves are those in the territories (because of low linkage rates—this exclusion involves two reserves), those that were incompletely enumerated in the 2011 Census and NHS or the 2016 Census (40 reserves), and those with 65 people or less according to the 2011 Census or to the linkage between the 2011 Census and the 2016 Census (short-form questionnaire) (409 reserves—including 250 reserves with 10 persons or less). This threshold was used to exclude reserves with very small populations to ensure robust estimation and because some indicators used in this paper such as the Community Well-Being Index were not available for reserves with populations smaller than 65. Overall, the excluded reserves only comprise 6.4% of the population enumerated on reserve in the 2011 Census.

The concept of migrant used for this article corresponds here to the concept of “internal migrant” as defined in the 2016 Census (Statistics Canada 2017): a migrant is a person who changed CSD during a given reference period.Footnote 5

In this article, the Indigenous population refers to people who reported being an Indigenous person—First Nations (North American Indian), Métis, or Inuk (Inuit)—or who reported being a Registered or Treaty Indian, as defined by the Indian Act of Canada, or who reported being a member of a First Nation or Indian band in the census or the NHS.

Throughout the document, reference is made to the population with Registered Indian status. In this article, all people who self-declared in the census or the NHS as a Registered Indian or a Treaty Indian under the Indian Act of Canada are considered Registered Indians.Footnote 6

4.2 Data Sources and Methods

It is a goal of this paper to study how newly available census linkages can contribute to improving the measurement of movements into and from reserves and to increase understanding of their dynamics. Census data linkages are useful in this context because they provide information for individuals at two points in time and allow researchers to avoid using retrospective information about place of residence. Details about how these census linkages were produced have been described extensively by Morency et al. (2021) and are not repeated here. Readers are therefore invited to consult that study to know more about (1) the advantages and limitations of censuses and linked files between censuses for the study of internal migration, (2) the linkage process, and (3) how linked records were weighted.Footnote 7

Different census linkages can be made depending on which questionnaires are linked. Three distinct linkages are used in this paperFootnote 8:

-

S2011/S2016: linkage of the 2011 and the 2016 Census short-form questionnaires

-

L2011/S2016: linkage of the 2011 National Household Survey (this voluntary survey replaced the long-form census questionnaire in 2011) and the 2016 Census short-form questionnaire

-

S2011/L2016: linkage of the 2011 Census short-form questionnaire and the 2016 Census long-form questionnaire.

Each combination has its advantages, reflecting the qualities of each type of questionnaire: the short-form questionnaires contain a very large number of records (since they are mandatory surveys) but few variables, whereas long-form questionnaires contain detailed information, but only for a (sizable) sample of the population.Footnote 9 The S2011/S2016 is particularly useful for estimation of migration rates when no detailed information about migrants is required, as this linkage has no exclusions related to sampling. Conversely, a linkage to the long-form questionnaire is necessary for analysis of migrant characteristics. Proper use of such linkages requires a thoughtful and adapted approach, which will vary depending on the goal of the analysis.

In the descriptive section of the paper, the focus is on estimating quantities that apply either to the whole Canadian population or to the whole Indigenous population. The 2011 NHS and the 2016 Census long-form questionnaire target 100% of the on-reserve population but only samples of the Canadian population living off-reserve. The use of sampling weights is thus required for proper estimation when using the L2011/S2016 or S2011/L2016 files. Note that by definition, in this paper, a migrant is someone who moved between two regions with different weighting schemes. The use of these weights also contributes to correction for biases induced by the linkage process, which may occur if non-linked individuals have different characteristics than linked individuals. Special sets of weights were computed to account for individuals who could not be linked for each of the three linkage files used in this study. This is particularly important, given that linkage rates are lower for individuals living on reserves and Indigenous people in general.Footnote 10

However, the calculation of the variance associated with estimates coming from linked files requires special procedures that take into account the unequal sample selection probabilities and unequal probabilities of successful linkages (Bollen et al. 2016). Unfortunately, the complex sampling schemes implemented in the 2011 NHS and (to a lesser extent) the 2016 Census long-form questionnaire to ensure adequate sample sizes for different groups of the population, combined with procedures used for optimal linkages (themselves sources of variance), make the process of recovering individuals’ probabilities of appearing in the file impossible to track. Consequently, procedures for the calculation of the variance that accounts for the sample design—such as computation of “bootstrap” weights or inclusion of varying (random) effects accounting for the complexity of the sampling design—could not be used, and it was not possible to compute variances or proceed to formal statistical tests for the descriptive part of the analysis.

The impossibility of computing variances in the census is often not a major issue in estimation, since they are usually negligible because of large sample sizes. It may become significant, however, for model fitting and interpretation of the results, a key task in the second part of the analysis. One option is to use a “model-based” approach, often adopted for regression analysis, where the data are assumed to originate from a simple random sample (Bollen et al. 2016; Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000). In fact, using unweighted data often provides more precise estimation (Solon et al. 2013). Analysts will often make sure to include information in their models that was used in the design of sampling schemes. But this approach cannot be used when the sampling schemes (and, therefore, the weights) are functions of the dependent variable (Winship and Radbill 1994; Solon et al. 2013; Lavallée and Beaumont 2015), as is the case in this study. Indeed, the origin and destination of migrants are two areas with different sampling schemes. The use of statistical weights is therefore preferable (i.e., using a “design-based” approach).

Table 1 illustrates the issue. All individuals who migrated to a reserve between 2011 and 2016 are present in S2011, S2016, and L2016, but not in L2011, where approximately one-third of households not living in a northern community or an Indian reserve were sampled. In fact, most of these migrants cannot be linked because they simply did not respond to the 2011 NHS. Likewise, some of the migrants who left a reserve between 2011 and 2016 would be missing in a linkage of S2011 or L2011 with L2016. Therefore, in linkages with L2011 or L2016, individuals who migrated and those who did not migrate live in areas with radically different sampling schemes, i.e., areas where the probability of being sampled varies largely.Footnote 11

One way to solve the problem would be to use the S2011/S2016 linkage, where the importance of the weighting is marginal. However, this dataset is limited in terms of the number of variables that it contains. A more astute method is to take advantage of the 100% sampling scheme in the reserves and vary the perspective depending of the type of flow examined. In this paper, “reserve to off-reserve migrations” are analyzed with the L2011/S2016 linkage. The characteristics of individuals come from the L2011 file and so, in the case of migrants, relate to their situation before the migration. The models simply contrast the characteristics of out-migrants to those of the population living on reserves in 2011. Off-reserve to reserve migrations, on the other hand, are analyzed with the S2011/L2016 linkage. Here, the setup is different because migrant characteristics are contrasted with those of the destination population, and the characteristics are those observed in 2016. Defined in this manner, the prevalence of migrations is adequately measured by the in-migration rate—not computed as a probability type of rate (Hamilton 1965), but as the number of in-migrants divided by the population at the destination.Footnote 12

Beyond allowing proper calculation of variances in conjunction with the model-based approach, the strategy—observing migration flows from the perspective of the sending or receiving reserves—has several benefits. First, the entire set of variables available in L2011 and L2016 can be used in the models. Second, no individual of interest for the model is excluded because of sampling or linkage to a sampled population, therefore making it possible to use a model-based approach. But perhaps more importantly, it places the reserves as the center of interest and provides a unique base of comparison for the two types of flows.Footnote 13 The models can be conceptualized as trying to predict, among the population living in a reserve, who the migrants are—that is, who is more likely to move out in the next 5 years, and who is more likely to have moved in over the last 5 years. To facilitate the interpretation of results, predicted probabilities are presented. Analyses were performed using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Comparisons of weighted and unweighted results were made to validate the adopted approach, following recommendations made by Solon et al. (2013). A first test consisted of comparisons between weighted and unweighted regression results using the S2011/S2016 linkage. A second test compared results between S2011/S2016 and L2011/S2016 for out-migration, and between S2011/S2016 and S2011/L2016 for in-migration. Resulting estimates and variances were of the same size in all comparisons, and this tends to confirm the soundness of the approach. While this suggests unbiased estimation of regression coefficients (and predicted probabilities), the estimation of variances does not account for the effects of non-response to the long-form census and for linkage errors, both in weighted and unweighted analyses. As a result, variances could be slightly underestimated, and this could lead to overstated significance levels.Footnote 14

4.3 Model Specification

Logistic regressions are a common choice in social sciences for modeling binary outcomes, such as the occurrence of an event. They are used to model the conditional probability that an outcome of interest \({\mathrm{Y}}_{i}\) occurs \(({Y}_{i}=1)\) given specific values of the predictor variables \({\mathrm{X}}_{i}\). In fact, to ensure that the predicted values are confined between 0 and 1, what is modeled is not the probability itself, but the log of the odds.Footnote 15

Perhaps less common is the use of multilevel models. These models represent a natural solution for the study of factors operating at different levels, such as individual and macro-level determinants (Massey 1990). Multilevel models provide the capacity to specify the correlation structure of various sets of predictors, rendering them so they are adapted to such hierarchical structures—in this example, the individual level (level-1) and the reserve level (level-2, representing a cluster of individuals).

In multilevel models, some of the predictors are treated as constant effects and others as varying effects.Footnote 16 Constant effects are similar to those estimated in a standard logistic regression model. Treating some level-2 variables as varying effects consists of estimating varying intercepts that reflect the variations in the average probability of the outcome in each cluster (technically, the log of the odds that the outcome realizes) in addition to the standard constant intercept, the overall average probability of the outcome. Variations in the varying intercepts, the varying-intercept variance, are indicative of the influence of the level-2 variable on the outcome: the higher this variance, the larger the influence. This is another benefit of multilevel models—they allow measurement of the proportion of the total variance related to the higher level factors (clusters).Footnote 17

If reserves have features that are influential in their capacity to attract and retain people, such as employment opportunities, schools, general well-being, and distance from essential services, then the assumption of independence of observations, important in linear modeling, is violated. While it is possible to treat some reserve characteristics as constant effects, it is not possible to control exhaustively for all possible intervening factors at the reserve level. At the same time, it is not of interest to obtain specific estimates for each reserve. Treating reserves as a varying effect allows control for the influence of any factors pertaining to reserves in a parsimonious way (in contrast to adding the reserve identifier as a constant effect in the model or running separate models for each reserve).

Note that in the regression models, some variables that could pertain to a higher level are treated as constant effects because the goal is to estimate their effect. Moreover, robust estimation of constant effects in the presence of varying effects and estimation of variance components require having sufficient number of clusters and observations within each cluster (Ali et al. 2019; Moineddin et al. 2007). Using reserves as a varying effect is not a problem, as it yields 533 distinct clusters (the 533 reserves retained for analysis). A more technical presentation of the models used in this paper is presented in Appendix 1.

In general, the choice of covariates was guided by the literature. Correlation analysis was also used to identify potential of contextual variable candidates. The contribution of the different levels of covariates was expressed by developing a series of increasingly complex nested models. Models are specified in parallel for each event, out-migration (series 1) and in-migration (series 2), to answer research questions 3 to 5. Models 1a and 2a are empty models used to estimate the variation in the outcome between clusters (reserves). They include no predictor, only a reserve identifier as a level-2 varying effect (varying-intercept). Models 1b and 2b add level-1 predictors related to individuals as constant effects. Models 1c and 2c add level-2 variables that pertain to reserves as constant effects. These variables are of two types: covariates describing reserve attributes such as location, size, or density, and covariates that consist of summary measures of individual-level characteristics, such as median age. Variables of the second type are present only in model 1c to measure how the composition of a reserve (e.g., median age) impacts out-migration. They should not be considered proxies for their individual-level analogs (e.g., age), also present in the regressions. One of these variables, the Community Well-Being Index, is an index—composed of 4 components: education, labor force activity, income, and housing—that measures socioeconomic well-being for communities (census subdivisions) across Canada over time (Indigenous Services Canada 2019). More details are provided about the Community Well-Being Index in Appendix 2. Summary measure variables are not included in-migration models because their presence would capture two very different things: how they impact in-migration and how the composition of the population on reserves contrasts with the composition of in-migrants.Footnote 18 Finally, models 1d and 2d are identical to 1c and 2c with the exception that the Community Well-Being Index is replaced by all the characteristics that make up the index.Footnote 19 Most of these variables are summary measures of individual-level characteristics and are excluded from model 2d for the reasons outlined above.

The results of the models, presented as predicted probabilities, show the predicted probability of an individual to experience the outcome for a given characteristic, at the average values of the other covariates. These probabilities have a cluster-specific interpretation, thanks to the multilevel specification adopted, meaning that they show the probabilities “within a given reserve.”

As mentioned previously, careful interpretation must be used for the results from the in-migration models, where the outcome is not an action but rather a state (being an in-migrant) reflecting the consequence of a past action (migration into a reserve). The analysis of the empty model (2a) is straightforward, as it simply assesses the influence of reserve characteristics (including their composition) on the attractiveness of a reserve. A similar interpretation can be given to reserve-level characteristics included in models 2c and 2d. The interpretation of individual-level characteristics requires more attention, though. Indeed, the specification forbids any kind of causal inference because non-migrants were never at risk of migrating into a reserve, since they were already living in one and because of the time order of the covariates, which refer to the situation in 2016. The inclusion of these covariates highlights the individual characteristics that distinguish in-migrants from the rest of the population in a reserve.

5 Results

Results are shown in two parts. The first is dedicated to results that are descriptive in nature and aims to (1) describe characteristics of migrants to understand how migration affects the composition of reserves and (2) provide a brief portrait of reserves in regard to their level of migration. The second part of this section delves into statistical modeling to draw statistical conclusions about the strength and significance of several factors thought to influence migration. As mentioned earlier, the number of reserves considered in the analysis may differ depending of the objective. For the first objective of the descriptive part of the paper (about the characteristics of migrants), almost all reserves are considered with the exception of those that were incompletely enumerated in 2011 or 2016 and those located in the territories (42 reserves). However, in the rest of the paper, all exclusions described in Section 4.1 are applied.

5.1 Descriptive Analysis

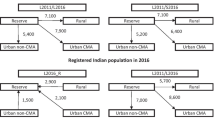

Between 2011 and 2016, reserves lost several thousand individuals globally through internal migration. Data drawn from the S2011/L2016 (for in-migrants) and from the L2011/S2016 (for out-migrants) reveal that reserves lost 16,100 individuals through internal migration during that 5-year span. This represents 4.6% of the population living on reserves in 2011.Footnote 20

However, the portrait is very different for the non-Indigenous population. Between 2011 and 2016, net migration on reserve was actually positive at + 4000 for the non-Indigenous population, compared with − 20,100 for the Indigenous population, resulting in a total loss of 16,100 people. Indigenous and non-Indigenous migrants also differ substantially (see Table A1 in the supplementary material file for a portrait contrasting characteristics of Indigenous and non-Indigenous migrants). Between 2011 and 2016, non-Indigenous reserve out-migrants and in-migrants were, on average, significantly older, wealthier, more educated, and more likely to live in suitable housing than their Indigenous counterparts. They were also moving into or out of a relatively low number of reserves. For instance, nine reserves located in a census metropolitan area (CMA) or a census agglomeration (CA) of British Columbia received 60% of all non-Indigenous in-migrants between 2011 and 2016. During the same period, 50% of all non-Indigenous out-migrants left these same nine reserves. By comparison, Indigenous migrants were distributed much more evenly among reserves. Overall, the reserves of origin and destination of non-Indigenous migrants were more often located in a CMA or a CA and had, on average, larger population sizes, larger shares of non-Indigenous people, and better scores on various socioeconomic indicators such as the Community Well-Being Index.

Restricting the analysis to the Indigenous population from this point onward, migrations into or from reserves have contributed to losses in reserves between 2011 and 2016. This was particularly true among young adults, females, people not in a union and without children or those with young children, Registered Indians or members of an Indian band, and people with the following characteristics: do not know an Indigenous language, do not have a diploma, are not in the labor force or are unemployed and looking for work, are in the very low income bracket, and are living in an overcrowded dwelling (see Table A2 in the supplementary material file)Footnote 21. Proportionally, reserves in Ontario and Manitoba, and those located in rural areas, had the greatest losses. Conversely, reserves are gaining people with higher income overall.

Migration from and into reserves contributed to increasing the age of the Indigenous population of reserves. In-migrants were older, on average, than out-migrants (25.3 vs. 21.3).Footnote 22 In fact, net migration rates were negative among individuals from age groups 40 to 44 and below, especially so among the 15-to-19 and 20-to-24 age groups. Net migration rates were closer to zero among age groups 45 to 49 and above (Fig. 1).

Overall, migration losses were more significant among females than males, a result that matches those of earlier studies cited before. The gap is most significant among age group 15 to 24, but remains substantial in all subsequent age groups up to 35 to 39 (Fig. 1). The sex ratio for the Indigenous population aged 5 years and older decreased from 101.8 males per 100 females to 101.2 males per 100 females between 2011 and 2016.Footnote 23 In 2016, however, the sex ratio would have decreased further to 100.0 without migration. Depicting the male-biased sex ratios on reserve and analyzing the potential reasons for it, Akee and Feir (2020) come to the conclusion that sex imbalances in migration flows are the most plausible explanation.

Although net migration of Indigenous people on reserve was globally negative between 2011 and 2016, not all reserves experienced negative net migration over the period. In fact, among the 533 reserves retained for this analysis, 51 recorded positive net migration, 338 recorded negative net migration, and 144 recorded net migration close to zero or very small counts of migrants. Close to half (23) of the reserves that experienced gains are located in British Columbia (Fig. 2), representing close to 14% of all reserves of the province. Only Alberta had a higher proportion of reserves experiencing gains (18%). By contrast, less than 5% of reserves in the Atlantic provinces, Ontario and Manitoba, and less than 10% of those located in Quebec and Saskatchewan, experienced net gains during that period. Higher proportions of reserves had net gains in CMAs (26%) and CAs (13%) than in rural areas (8%) (See Table A3 in the supplementary material file).

Figure 3 shows histograms of the reserves according to Indigenous in-migration and out-migration rates. The in-migration rate histogram shows a right-skewed distribution with more than 70% of the reserves located below 100 per thousand. By contrast, the out-migration histogram is more symmetric and flat, with less than 30% below 100 per thousand. The median in-migration rate was half the median out-migration rate (70.6‰ vs. 140.7‰).

5.2 Regression Models

Tables 2 and 3 present the results of the regression models exploring out-migration, in-migration, and composition. As described earlier under Section 4.3, all models use a multilevel specification with reserves as a varying effect. The addition of the varying effect improves the fit of the model (statistical significance of p < 0.0001). Out-migration and in-migration are explored in turn.

5.2.1 Out-Migration

From model 1a (Table 2), it is possible to estimate an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC)Footnote 24 factor of 9.3%, which represents how much of the total variation in the outcome can be accounted for depending on the reserve an individual lives in. This result confirms that, as suggested in the literature, some reserve-level characteristics influence out-migration.

Model 1b adds individual-level characteristics. Almost all individual covariates show coefficient estimates as significant (at p < 0.0001). Characteristics showing particularly strong positive associations are age, especially the 15-to-29 group, not being a Registered Indian or an Indian band member, and not being in a union with a Registered Indian or an Indian band member. This last result is not surprising given that in several Indigenous communities, entitlement to live on a reserve is often granted only to people who are Registered Indians and members of an Indian band, or to those who are not but live with a spouse/partner who is. Other associations are found for the following characteristics: not being a Registered Indian or an Indian band member but being in a union with a Registered Indian or an Indian band member, not being in a union and without children, not knowing an Indigenous language, sex (female), not having Indigenous ancestry, being employed off reserve, having at least a high school diploma, living in a dwelling with a shortfall of at least two bedrooms (unsuitable housing), and not being in a union and with at least one child younger than 5.Footnote 25

These associations remain significant in models 1c and 1d.

For model 1b, the median odds ratio (MOR) value of 1.740 and its reciprocal of 0.575 can be compared with odds ratios associated with individual-level characteristics.Footnote 26 Thus, the reserve where a person was living has a non-negligible influence on the propensity to migrate, but other individual-level attributes, such as age and Registered Indian status, band membership, or status of spouse, have effects of higher or comparable magnitude. For example, contrasting the 15-to-29 age group with the 45-to-64 age group in model 1b yields an odds ratio twice as high (3.45). On the other hand, contrasting female and male yields a lower odds ratio of 1.34. The inclusion of individual-level characteristics as constant effects in this model barely reduces the ICC value, implying that composition effects do not play much of a role in the differences in out-migration rates between reserves.

Model 1c has the addition of reserve-level characteristics. Globally, out-migration increases with remoteness and decreases with population size. It is higher in Alberta and lower in the Atlantic provinces. The inclusion of reserve-level characteristics as constant effects in this model reduces the ICC value to 7.1%, meaning that they account for 24% of the total variance attributable to reserve-level characteristics. The fact that the inclusion of the level-2 varying effect remains significant suggests that the list of reserve-level characteristics included in the model influencing migration is not exhaustive.

The Community Well-Being Index does not add much strength to model 1c. However, this could be because some of its constituents act in different directions. In model 1d, where these constituents are included separately, high labor force participation rates and low employment rates in the reserve are positively associated with out-migration.

5.2.2 In-Migration

As model 1a did for out-migration, model 2a (Table 3) shows the results of an empty model applied to in-migration. Although not large, the ICC of 11.1% is a confirmation that in-migration is not homogeneous among reserves, with some welcoming proportionally more Indigenous in-migrants than others. The MOR value of 1.841 is slightly higher than in the comparable out-migration model.

The inclusion of individual-level covariates in model 2b decreases the ICC by 14.5% to 9.5%. Clearly, there must be heterogeneity in how reserves attract in-migrants with regard to their composition. But as mentioned earlier, these covariates also reflect how in-migrants differ from non-migrants, rendering the interpretation of the predicted probabilities difficult.

All individual covariates included in the models show significant association with being an in-migrant. Strong positive associations are found with the following characteristics: not being a Registered Indian or an Indian band member and not being in a union with a Registered Indian or an Indian band member, as well as not being a Registered Indian or an Indian band member but being in a union with a Registered Indian or an Indian band member. A strong positive association also exists with regard to age, in particular groups aged 15 to 29 and 30 to 44. Other characteristics associated with in-migrant status are having a postsecondary diploma, not knowing an Indigenous language, being in a union and with at least one child younger than 5 years, being employed off reserve, being in a union and without children, not having Indigenous ancestry or having mixed ancestry, and being female. These associations remain significant in models 2c and 2d.

The addition of reserve-level characteristics in models 2c and 2d further reduces the ICC by 29%. The probabilities of being an in-migrant are higher in Saskatchewan, Alberta, and Manitoba but much lower in the Atlantic provinces and in Quebec. Significant effects were also found for population size of the reserve, with higher probabilities of in-migration into the least populated reserves in contrast to the most populated, and for the Community Well-Being Index of the reserve, with higher probabilities when the value of the index is high.

6 Discussion

In the previous section, the characteristics of Indigenous migrants and non-Indigenous migrants were compared using descriptive results. The contrast is striking, but perhaps not surprising, given that the presence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in reserves must follow different dynamics, particularly because non-Indigenous individuals are not usually entitled to benefits and services offered to band members and Registered Indians. These results support the approach of studying the two populations distinctly as was done here, but also suggest that a deeper investigation of the migration into and out of reserves of non-Indigenous populations is warranted.

When the analysis is limited to the Indigenous population, it was observed that overall, reserves experienced very heterogeneous outcomes in terms of migration between 2011 and 2016. Close to two-thirds of reserves recorded losses of Indigenous people during that time. Migration also had an effect on the composition of the population. Globally, migration has contributed to increasing the age of the Indigenous population of reserves. Between 2011 and 2016, the mean age of the Indigenous population living on reserves increased by 1.0 year, from 31.8 to 32.9 years. Migration into and from reserves during this period contributed to an increase in the mean age of this population by 0.7 years; i.e., the mean age would have increased by 0.3 years had there been no migration.Footnote 27 This may seem surprising but the relatively high fertility rates observed on reserves, with a total fertility rate way above the replacement level at around three children per woman (Morency et al. 2018), explain why the population is continually growing, with younger cohorts surpassing older ones. This growth factor contributes to the rejuvenation or maintenance of the young age structure of the population.Footnote 28

Migration also contributed to an increase in the number of Indigenous people with high income (above $40,000) on reserve. Inversely, it contributed to a decrease in the proportions of individuals who are not in union and without children or with at least one child younger than 5 years, who have no diploma, who are not in the labor force or unemployed, and who are not living in a suitable dwelling.

An important result of this study is that reserve-level characteristics contribute to 9% of total variance in the out-migration model and 11% in the in-migration model. While these numbers attest that reserves exert push and pull effects on migration, they may seem somewhat trivial given the importance of contextual variables recognized (but never adequately quantified) in the literature and how heterogeneous reserves are in terms of size, distance from an urban center, availability of resources, population composition, and so on.

The results show that several reserve attributes are associated with migration of Indigenous people (while controlling for the demographic composition of reserves). Remoteness and high labor force participation rates are positively associated with out-migration, while population size and employment rates show a negative association.Footnote 29 Province of residence was also associated with migration. Living in Alberta appears as a push factor, while living in the Atlantic provinces or in Quebec seems to have a retention effect. Conversely, living in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta is associated positively with being an in-migrant. Note the seemingly unintuitive association where living in Alberta is found to be associated with both in- and out-migration. This result is a phenomenon that has long been observed and could be caused in large part by other characteristics unobserved in the models. For example, looking at migration movements in cities of England and Wales, Cordey-Hayes and Gleave (1973) found that high out-migration rates could be an indirect consequence of the attractiveness of the region, which itself contributes to raise in-migration rates. In the case of Alberta, employment opportunities related to the extraction of oil as well as oil support activities have attracted a large number of migrants in the last decades. These residents have ties in another province and may consider migrating again, especially if the labor conditions worsen (Plane and Rogerson 1994). Considering that labor market conditions deteriorated between 2011 and 2016 following the decline in oil prices that started mid-2014 (Gellatly and Richards 2016), labor market turnover could be an explanation for the relatively high out-migration rates in Alberta.

Overall, the addition of contextual variables to the model only contributed to a fraction of the between-reserve variance, especially in the out-migration model. Clearly, there must be other unobserved reserve-level attributes that influence migration. One of these characteristics could be the Indian band and First Nation membership rules adopted in a reserve. This is important because these rules may grant access to sets of economic entitlements and political rights, but not all reserves share the same rules (Clatworthy 2007).

In terms of individual characteristics, the sets of variables associated with out-migration, such as (young) age and marital status, are most likely proxies for situations in life that often trigger migration, such as going to school, finding a job, entering a union with someone, or having children. Such events are universal in nature, and their occurrence must depend little on the reserve one lives in. This could explain the relatively low importance of reserve-level characteristics in explaining migration in contrast to age. Other variables, such as speaking an Indigenous language or having Indigenous ancestry, may point toward more abstract notions of the way individuals perceive themselves and the sense of belonging to a community. Indeed, as noted earlier, connection to home or to the community was one of the most cited reasons in FNIGC (2018) for coming back after having left a reserve. Conclusions can only be speculative here, but speaking an Indigenous language and having Indigenous ancestry could be related to higher attachment to the community, which may have a retention effect. In the case of speaking an Indigenous language, attachment to a community can be a driver for someone to learn a language, but learning the language may have promoted attachment to the community. For Indigenous populations, this attachment can take form for multiple reasons. Living on reserves may provide access to territories used over generations for fishing and hunting, and access to advice from elders. Symbolically, reserves may be perceived as sites associated with ceremonial and spiritual practices. In fact, as Landry et al. (2019) wrote: “Indigenous culture, identity, knowledge, and practices are intimately linked to the land.” Relatedness to the land has been associated with positive outcomes in terms of well-being among Indigenous populations (Landry et al. 2019; Huyser et al. 2018; Flynn 1995).

In the in-migration models, the addition of individual-level characteristics contributed to decrease the between-reserve variance, in large part because in these models they act as reserve characteristics, reflecting their composition. However, because these covariates also reflect how migrants generally differ from non-migrants, these results must be interpreted with caution.

Looking at the composition of migrants, in-migrants appear to differ significantly from out-migrants. They tend to be more educated and earn higher income, and they are more likely to be employed and to live in suitable housing. In contrast to the non-migrant Indigenous population on reserve, Indigenous in-migrants are less likely to be Registered Indians and to know an Indigenous language, but are more likely to have mixed ancestry or non-Indigenous ancestry only. Overall, the influx of in-migrants changes the composition of reserves in two ways: it contributes to the global improvement of several socioeconomic indicators and it increases the heterogeneity of the population with regard to Indigenous ancestry status, Registered Indian status, knowledge of an Indigenous language, etc. Finally, in-migrants are more likely to choose a reserve with a relatively small population size, with a high Community Well-Being Index score and with a high proportion of non-Indigenous people—this last element possibly acting as a proxy for less restrictive band membership rules.

7 Conclusion

For historical and political reasons, migrations from and into reserves have received special attention. The demographic evolution of the population on reserve, the impact of migration on the composition and well-being of First Nations communities, and the motivations that triggered and influenced such migrations have been studied for several decades. Using recently available linked census data, this study helps to improve understanding of migration patterns on reserves. In particular, it highlights how migration into and out of reserves is multidimensional, being influenced by factors at both individual and community levels.

Between 2011 and 2016, the population of First Nations people on reserve grew from 320,000 to 335,000 people, while the off-reserve First Nations population grew from 532,000 to 643,000. Globally, population loss resulting from migrations into and out of reserves during the period did not prevent reserves from growing, and contributed only marginally to the growth of the Indigenous population outside reserves (Morency et al. 2021).

To return to the five research questions of this study, it was found that reserves differed substantially in their capacity to retain individuals and attract migrants. These differences are caused in part by characteristics specific to reserves. Out-migrants and in-migrants have characteristics that differ from non-migrants living on reserves. From a socioeconomic point of view, migrations had a net positive impact on reserves by contributing to increase the proportions of individuals who are employed, with relatively high incomes or relatively high education. Out-migration seems to be governed mainly by the propensity of individuals at certain stages of life to leave the reserve, permanently or not. Out-migration was associated positively with remoteness and labor force participation rates, and negatively with population size and employment rates. In contrast to out-migration, in-migration appears more influenced by reserves’ characteristics, its prevalence varying greatly among reserves.

Reserves that attract more migrants tend to be those with a higher score on the Community Well-Being Index and with smaller population size. The province of residence has an effect on both in- and out-migration, suggesting the presence of other unobserved push and pull factors at play.

The relative unimportance of socioeconomic conditions in the models may be surprising, given that it is among First Nations people living on reserve that the lowest employment rates, median income, and educational levels are found (NIEDB 2019), and in view of the numerous obstacles related to economic development faced by Indigenous communities (e.g., Nelson 2019; OECD 2020). However, if a lack of opportunities for education or employment is common in reserves, it is an expected result because in this study, reserves are compared with themselves. Such lack of opportunity is not unique to reserves, but to small communities in general. The fact that the most important predictor of migration is belonging to the group aged 15 to 29 could be partly because it is at those ages that lack of opportunity is felt most acutely. As a note of caution, it is important to avoid any particularization of the situation on a reserve based on the global picture. For example, there could be reserves where poor living conditions constitute the predominant factor in out-migration.

Another note of caution worth stating is that although multilevel regression models allow control for many possible confounding effects, the evidence remains correlational. The models do not aim for inference on the specific nature of the links between individual and macro-level determinants, or for causal interpretation of the determinants; this would require the construction of a complete theoretical framework that is outside the scope of this study. They do, nevertheless, sketch a general picture of the determinants most suspected to induce migration, both at the individual level and at the reserve level.

Results of this study also highlight important remaining data gaps. For example, it was shown that a significant number of non-Indigenous people have moved into and out of reserves between 2011 and 2016. Indeed, reserves globally gained several thousand non-Indigenous people during that period. To the authors’ knowledge, migration into and out of reserves by non-Indigenous people has never been a subject of research, perhaps because it tends to be a marginal phenomenon in most reserves. Dedicated research could help to better understand the motivations of these migrants, as well as the impact of these migrations on the demographic and socioeconomic fabric of reserves.

Another area for future research could be to better understand the role of circular migration. The fact that some individuals eventually leave the reserve to look for education, work or work experience, or a life partner is to be expected. For example, possibilities for postsecondary education are inevitably limited in some reserves, particularly the more remote ones. A relevant question, in this context, is to what extent are out-migrants eventually coming back to reserves, and how many in-migrants were in fact previous out-migrants? Insights from qualitative studies confirm the existence of return or circular migration (e.g., Irvine 2010). However, it was not possible to observe return flows with the census linkage used here, with only two points in time.

Data Availability

Not available.

Code Availability

Not available.

Change history

11 May 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42650-022-00066-2

Notes

In the context of this article the terms “Indian reserves” and “reserves” are used as a shortcut to refer to the 6 census subdivision (CSD) types associated with “on reserve” population in the 2016 Census which includes (1) Indian reserve (949 CSDs), (2) Indian settlement (23 CSDs), (3) Indian government district (2 CSDs), (4) Terres réservées aux Cris (8 CSDs), (5) Terres réservées aux Naskapis (1 CSD), and (6) Nisga'a land (1 CSD) (Statistics Canada 2018a).

The term “Aboriginal people” has been used extensively in the past to refer to First Nations, Inuit, and Métis people, as well as to Registered Indians and members of Indian bands or First Nations. However, the term “Indigenous people” has come to be preferred in recent years.

In this paper, reserves are identified based on the definition used in the 2016 Census. For this reason, estimates for a year other than 2016 may differ slightly from those obtained from the census of that year.

In 2011, the NHS replaced the long-form questionnaire of the 2011 Census. For this reason, in this article, “2011 Census” refers to the short-form questionnaire, while “2011 NHS” refers to the long-form questionnaire.

Consequently, people who did not live in Canada 1 year or 5 years before the census and NHS reference date but who had a usual place of residence in Canada at the time of the collection (“external migrants”), as well as people who changed their place of residence within the same CSD (“people who have moved”), are not considered to be migrants for the purposes of this study.

A data linkage between the 2011 NHS and the Indian Register and between the 2016 Census long-form questionnaire and the Indian Register allowed the addition of information about the registration category (6[1] or 6[2]) on the Indian Register for the Registered Indian population. When a case could not be linked to the Indian Register, the registration category was either deterministically imputed using information on the registration of other census family members or imputed using a probabilistic model. Imputation was necessary for 15% of cases in the 2011 NHS and 20% in the 2016 Census. Registered Indians in category 6(1) have two parents who are Registered Indians, while those in category 6(2) have one parent who is a Registered Indian and one parent who is not.

More information about the linkages and weighting processes is provided by Morency et al. (2021) and the supplementary material accompanying the article. At the time of publication of this article, these linkage files could be accessed only through a partnership with researchers from Statistics Canada.

Data from the 2011 Census (S2011) and the 2011 NHS (L2011) are also used to calculate several indicators at the reserve level that serve as reserve contextual information throughout this article.

The short-form questionnaire asks fewer questions, but targets 100% of the Canadian population, while the long-form questionnaire contains more questions but is sent only to a sample of the Canadian population living in private households.

See Morency et al. (2021) for an in-depth discussion about the issue of linkage rates.

Table 1 in Morency et al. (2021) shows the distribution of the weights in various census linkages combining data from short- and long-form questionnaires. Of particular importance are the differences between weights of those who migrated and those who did not. It can be seen that these differences are substantial in all files except linkages of consecutive short-form questionnaires.

This conceptualization yields results that require careful interpretation, since the migrants (the numerator) are not a subset of the population living on a reserve (the denominator), as will be discussed later in this section. However, it shares the usefulness of in-migration rates, providing “a measure of the impact of migration upon the receiving population” and permitting “analysis of the composition of the population with respect to migration status” (United Nations 1970, p. 41).

That is, characteristics of out-migrants and in-migrants are all contrasted by those of the population living on reserve, although observed at two different times.

For this reason, it is preferable to focus on the real effects (the magnitude of the probabilities) than the statistical significance of the results—a good recommendation for any analysis in general.

Other transformations are possible. There is, however, a simple relationship between the coefficients estimated from a logistic regression and the odds ratio, an intuitive measure of association that is widely used in social sciences and that can be computed straightforwardly from a contingency table (Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000).

This follows Gelman’s terminology (see Gelman 2005). In the literature, constant and varying effects are most often but more ambiguously referred to as “fixed” and “random” effects.

More complicated models, not used in this paper, also include varying slopes, which allows the estimation of constant effects independently in each cluster (e.g., the effect of age could vary from one cluster to the next).

This issue exists because of the disconnection between migrants and non-migrants. In out_migration models, the composition of migrants and the composition of the population living on-reserve are not independent, since the former are a subset of the latter.

Two indexes are included in the regression model: the Community Well-Being Index and the Remoteness Index. Both are described in Appendix 2.

Other variants of the 2011/2016 data linkage provide slightly different results. For instance, according to the S2011/S2016 and the L2011/L2016 files, reserves recorded net migration of − 18,900 and − 20,400 individuals, respectively (Morency et al., 2021).

Based on the age in 2011 and excluding those who were born between 2011 and 2016.

The sex ratios for 2011 and 2016 were computed from the 2011 NHS and the 2016 Census (long-form questionnaire) data. People in reserves located in the territories or that were incompletely enumerated in the 2011 NHS or the 2016 Census were excluded from the calculations.

See Appendix 1 for a description of the ICC.

The results for a variable are conditional to other variables included as constant effects, but also to the reserve, given its inclusion as a varying effect. Thus, predicted values reflect comparisons of individuals made within the same reserve (or within reserves having the same risk of outcome).

The odds are the probability that an outcome occurs divided by the probability that the outcome does not occur. The ratios of these odds (odds ratios) measured for two distinct covariates contrast their influences on the outcome (with an odds ratio of 1 showing no difference). The odds ratios can be computed easily from the predicted probabilities shown in Table 2.

Estimates were computed from the S2011/L2016 and S2016/L2011 files. Results may differ with estimates computed from the 2011 NHS and the 2016 Census. Estimation of the impact of migration does not account for migrants aged 0 to 4 (as they were not born in 2011).

By comparison, the total fertility rate of the whole Canadian population has been much lower in recent years, at about 1.6, and its median age much older, at 40.7 years (Statistics Canada 2018b). The comparatively higher mortality rates observed on reserves (Feir and Akee 2019) may also, to a lesser extent, contribute to the younger age structure of the population living on reserves.

Population size is sometimes seen as a proxy of institutional completeness—i.e., the presence of administrative, educational, and medical institutions (Gerber 1984).

Multilevel models are often used to account for study design, when observations are drawn from a sample of larger units (clusters, regions, for example) and the choice of that unit has an impact on the outcome (outcomes are correlated within a unit). But this is not an incentive since all units of interest were sampled evenly (in fact, all units of interest were sampled, period).

References

Aitkin, M., & Longford, N. (1986). Statistical modelling issues in school effectiveness studies. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A, 149, 1–43.

Akee, R., & Feir, D. (2020). Gender ratios on First Nations reserves in Canada. Canadian Studies in Population, 47, 213–227. Available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s42650-020-00023-x.

Alasia, A., Bédard, F., Bélanger, J., Guimond, E., & Penney, C. (2017). Measuring remoteness and accessibility: A set of Indices for Canada communities. Reports on Special Business Projects. Statistics Canada (catalogue no. 18–001).

Ali, A., Khan, S.A., & Khan, D.M., et al. (2019). Sample size issues in multilevel logistic regression models. PLoS ONE 14(11), e0225427. Available at https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225427.

Allison, P. D. (1999). Logistic Regression Using the SAS® System: Theory and Application. SAS Institute Inc.

Amorevieta-Gentil, M., Bourbeau, R., & Robitaille, N. (2015). Migration among the First Nations: Reflections and inequalities. Population Change and Lifecourse Strategic Knowledge Cluster Discussion Paper Series / Un Réseau stratégique de connaissances Changements de population et parcours de vie Document de travail, 3(1), 10. Available at https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/pclc/vol3/iss1/10.

Austin, P. C., & Merlo, J. (2017). Intermediate and advanced topics in multilevel logistic regression analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 36, 3257–3277. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.7336

Bollen, K. A., Biemer, P. P., Karr, A. F., et al. (2016). Are survey weights needed? A review of diagnostic tests in regression analysis. Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application, 3, 375–392. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-statistics-011516-012958

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data Analysis Methods. Sage.

Clatworthy, S. J. (1996). The migration and mobility patterns of Canada’s Aboriginal population. Report prepared for the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, and the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

Clatworthy, S. J. (2007). Indian registration, membership, and population changes in first nations communities. In J. P. White, S. Wingert, D. Beavon, & P. Maxim (Eds), Aboriginal policy research volume V: Moving forward, making a difference (pp. 99–120).

Clatworthy, S. J., & Norris, M. J. (2007). Aboriginal mobility and migration: Trends, recent patterns, and implications: 1971–2001. In J. P. White, S. Wingert, D. Beavon, & P. Maxim (Eds.), Aboriginal policy research volume IV setting the agenda for change (pp. 207–234). Available at https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci/103/.

Clatworthy, S. J., & Norris, M. J. (2014). Aboriginal mobility and migration in Canada: Trends, patterns and implications, 1971 to 2006. In F. Trovato & A. Romaniuk (Eds.), Aboriginal Populations: Social, Demographic and Epidemiological Perspectives (pp. 119–160). The University of Alberta Press.

Clatworthy, S. J., & Cooke, M. (2001). Patterns of registered Indian migration between on- and off-reserve locations. Research and analysis directorate, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada.

Cooke, M. (1999). On leaving home: Return and circular migration between First Nations and prairie cities. Graduate thesis. Department of Sociology, University of Western Ontario.

Cooke, M., & Bélanger, D. (2006). Migration theories and First Nations mobility: Towards a systems perspective. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 43(2), 151–164.

Cooke, M., & O’Sullivan, E. (2015). The impact of migration on the First Nations Community Well-Being Index. Social Indicators Research, 122, 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0697-4

Cooke, M., & Penney, C. (2019). Indigenous migration in Canada, 2006–2011. Canadian Studies in Population, 46(2), 121–143.

Cordey-Hayes, M., & Gleave, D. (1973). Migration movements and the differential growth of city regions in England and Wales. CES Research Paper 1, and Papers of the Regional Science Association, Volume 33.

de Leeuw, J., & Kreft, I. G. G. (1986). Random coefficient models for multilevel analysis. Journal of Educational Statistics, 11, 57–85.

Feir, D., & Akee, R. (2019). First Peoples lost: Determining the state of status First Nations mortality in Canada using administrative data. Canadian Journal of Economics, 52, 490–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/caje.12387

First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). (2018). National Report of the First Nations Regional Health Survey Phase 3: Vol. 2. First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC).

Flanagan, T. (2019). The wealth of first nations. Fraser Institute.

Flynn, L.L. (1995). Buffalo burgers with cappuccino: Urban Indians in Vancouver. In Tiberini, E.S. (Ed.), L’Uomo, special edition. North American Indians: Cultures in motion. Societa Tradizone Sviluppo. University of di Roma La Sapienza VII n.s – n-1, 45–62. Available at https://rosa.uniroma1.it/rosa03/uomo/article/view/14818/14320

Frideres, J. S. (1998). Aboriginal peoples in Canada: Contemporary conflicts (5th ed.). Prince Hall/Allyn and Bacon.

Gardner, R. W. (1981). Macrolevel influences on the migration decision process. In G. F. De Jong & R. W. Gardner (Eds.), Migration decision making: Multidisciplinary approaches to microlevel studies in developed and developing countries (pp. 59–89). Pergamon Press.

Gellatly, G., & Richards, E. (2016). Recent developments in the Canadian economy: Fall 2016. Economic Insights, no. 61. Statistics Canada (catalogue no. 11–626-X). Ottawa: Statistics Canada.

Gelman, A. (2005). Analysis of variance – Why it is more important than ever. The Annals of Statistics, 33(1), 1–53. https://doi.org/10.1214/009053604000001048

Gerber, L. M. (1984). Community characteristics and out-migration from Canadian Indian reserves: Path analyses. Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology, 21(2), 145–165.

Hamilton, C. H. (1965). Practical and mathematical considerations in the formulation and selection of migration rates. Demography, 2, 429–443.

Hosmer, D. W., & Lemeshow, S. (2000). Applied logistic regression (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

Hox, J. J. (1995). Applied multilevel analysis. Amsterdam: TT-Publikaties.

Huyser, K. R., Angel, R. J., Beals, J., Cox, J. H., Hummer, R. A., Sakamoto, A., Manson, S. M., & the AI-SUPERPFP Team. (2018). Reservation lands as a protective social factor: An analysis of psychological distress among two American Indian tribes. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 4, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023118807022

Indigenous Service Canada. (2019). Report on trends in First Nations communities, 1981 to 2016. Available at: https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/DAM/DAM-ISC-SAC/DAM-STSCRD/STAGING/texte-text/report-trends-FN-Comm-1981-2016_1578933771435_eng.pdf

Institute of Urban Studies. (2004). First Nations/Métis/Inuit Mobility Study – Final Report, March 2004. Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10680/310.

Irvine, P.R. (2010). From reserves to cities (and back): the significance of reserves in Registered Indian Women’s migration. Master’s Thesis. University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon. https://harvest.usask.ca/bitstream/handle/10388/etd-05182010-071944/completedthesis.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Kinfu, Y. (2005). Spatial mobility among Indigenous Australians: Patterns and determinants. Working Papers in Demography no. 97. Research School of Social Science, Australian National University (Canberra: CAEPR).

Landry, V., Asselin, H., & Lévesque, C. (2019). Link to the land and Mino-Pimatisiwin (comprehensive health) of Indigenous people living in urban areas in eastern Canada. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(23), 4782. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16234782

Larsen, K., Petersen, J. H., Budtz-Jørgensen, E., & Endahl, L. (2000). Interpreting parameters in the logistic regression model with random effects. Biometrics, 56, 909–14.

Lavallée, P., & Beaumont, J.-F. (2015). Why we should put some weight on weights. Survey Methods: Insights from the Field, Weighting: Practical Issues and “How to” Approach. https://doi.org/10.13094/SMIF-2015-00001

Lee, E. S. (1966). A theory of migration. Demography, 3, 47–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/2060063

Massey, D. S. (1990). Social structure, household strategies, and the cumulative causation of migration. Population Index, 56(1), 3–26.

Moineddin, R., Matheson, F.I., & Glazier, R.H. (2007). A simulation study of sample size for multilevel logistic regression models. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7(34). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-7-34

Morency, J. D., Caron Malenfant, É., & Daignault, D. (2018). Fertility of Aboriginal people in Canada: An overview of trends at the turn of the 21st Century. Aboriginal Policy Studies, 7(1), 34–61.

Morency, J. D., Dion, P., & Grondin, C. (2021). Migration between Indian reserves and off-reserve areas: An exploratory analysis using census data linkage. Canadian Studies in Population, 48(1), 91–122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42650-021-00042-2