Abstract

Research on global climate change governance is no longer primarily concerned with the international legal regime, state practice and its outcomes, but rather scrutinizes the intricate interactions between the public and the private in governing climate change. This broad trend has also taken center stage within the pages of INEA. Two decades after its establishment, we sketch the main theoretical debates, conceptual innovations and empirical findings on global climate change governance and survey the new generation of climate governance scholarship. In more detail, we sketch how climate governance research has developed into three innovative sub-debates, building on important conceptualizations and critical inquiries of earlier debates. Our aim is not so much to provide an all-encompassing assessment of global climate change governance scholarship in 2022, but rather to illustrate in what important ways current research is different from research in the early phase of INEA, and what we have learned in the process. First, we discuss scholarship on the bottom-up nature of climate governance, developing from earlier ideas on agency beyond the state and the transnationalization of governance arenas. Second, we review contributions that have more systematically engaged with the concept of governance architectures, resulting in a stimulating new academic debate on the characteristics of complex governance systems and the consequences of governance complexity and fragmentation. Third, we note a distinct normative turn in global environmental scholarship in general and global climate governance in particular, associated with question of access, accountability, allocation, fairness, justice and legitimacy. The assessment of each of these debates is centered around questions of effective and legitimate climate governance to counter the climate emergency. Finally, as a way of concluding, we critically reflect on our own scholarly shortcomings and suggest a modest remedy.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Over the last 20 years, we have witnessed a gradual transformation of global climate governance, both in terms of substance and focus, from a top-down state-centered international to a more complex multi-actor and multi-level bottom-up transnational arena. In 2008, INEA published an article (Pattberg & Stripple, 2008) that conceptualized this shift as the emergence of a transnational climate governance domain, understood as “the gradual institutionalization of a transnational public sphere in world politics, where the establishment of norms and rules and their subsequent implementation are only to a limited extent the result of public agency in the formal sense, but often the outcome of agency beyond the state” (Pattberg & Stripple, 2008, 369). In this article, we revisit three important arguments about this shift, sketching how the next generation of global climate governance scholarship has engaged with the empirical puzzles and contradictions that started to become increasingly visible more than two decades ago. In more detail, we focus predominantly on research that has been published in this journal, without ignoring important climate-related research published outside INEA. We identify three distinct of sub-themes of global climate governance research that have emerged over the last two decades and have prominently been pursued within the pages of this journal. Next to providing an account of the conceptual and theoretical innovations related to transnational climate governance, we are in particular interested in the lessons learned about effective interventions, approaches and institutions. As we are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972, we are taking stock of our knowledge about the promises and pitfalls of transnational climate governance.

The first sub-theme is agency beyond the state (Nasiritousi et al., 2014). Scholars such as Hall and Biersteker (2002) and Ruggie (2004) have noted early on that public policy could be pursued by a range of non-state actors, and that consequently, the authoritative allocation of values within societies was increasingly taking place “beyond the confines of national boundaries, and a small, but growing fraction of norms and rules governing relations among social actors of all types […] are based in and pursued through transnational channels and processes” (Ruggie, 2004, 521). From these conceptual beginnings, a fruitful scholarly debate on the groundswell of non-state climate action has emerged, now occupying center stage in climate governance research (Bäckstrand et al., 2017; Hermwille, 2018).

Another development is the increased attention paid to the broader governance system and the use of insights from complexity theory (Orsini et al., 2020). A first generation of governance scholarship has analyzed the conditions for effectiveness of international environmental regimes, including the UNFCCC and the Kyoto Protocol, while a second generation put emphasis on interplay and interlinkages between international institutions. Around 2008, a third generation of scholarship was starting to pay attention to the systemic level of governance, focusing conceptually on ideas such as fragmentation and cohesion (Biermann et al., 2009). In fact, Pattberg and Stripple (2008, 385) called for more research in this field when they argued that “we need to further our knowledge about the systemic interaction between the international and transnational global climate arena and the possibility for effective and equitable governance, taking into account a growing number of agents in a multiplicity of institutional contexts.” Based on these fundaments, a lively academic debate emerged on the appropriate concepts and methods to analyze the system level of environmental governance. We will portray the main insights from this sub-field under the heading ‘from fragmentation to complexity.’

A third notable development concerns what we refer to as a normative turn in global environmental governance research. Concepts such as allocation and access (Gupta & Lebel, 2020), fairness and equity (van den Berg et al. 2016), and legitimacy and accountability (Dombrowsky, 2010) have become widely discussed as key ingredients for the sustainability transition. Already in the 1990s, Rosenau (1997, 39) attempted to analyze novel spheres of authority beyond the state as the building blocks of “a new ontology where states are treated as only one of the many sources of authority” (Pattberg & Stripple, 2008, 372). A central question then was to understand how domestic concepts such as ‘democratic accountability’ could be applied to the realm of transnational politics (Dingwerth, 2007).

Finally, after having discussed three distinct conceptual, theoretical and empirical contributions that emerged within the pages of INEA over the last two decades, we focus on renewed attention to the politics of climate change, building on the observation that the predominant market-based ideology visible in policy instruments such as emission trading is problematic. Whereas initial scholarship provided some useful reflections on ‘climate governance beyond the state,’ we now need to concede that in order to follow the climate deeper into social, cultural and material realms, we need new concepts and critical perspectives. Consequently, we engage in some self-reflection on the state of global climate governance scholarship as a way of conclusion.

2 The global climate change governance arena: from agency beyond the state to bottom-up climate action

In the beginning of the 2000s, the “predominant perspective on global climate governance” was biased toward interstate negotiations (Pattberg & Stripple, 2008, 369). However, seeds of change were already in the ground, promising a broader, more inclusive perspective on agency. For instance, in an editorial for INEA on the institutional design of global environmental governance, Vellinga and colleagues (2002, 294) wrote that one could imagine “a system that is perhaps beyond the current United Nations thinking and makes room for not only state actors but also civil society, industry and other international and national players,” but that “it is not clear what such a system would look like.” Despite the budding interest in agency ‘beyond the state,’ INEA contains few articles from the early 2000’s elaborating on how such a system could look like and what actors it should involve. Research interest in non-state actors (e.g., cities, NGOs and companies) primarily pertained to their role and influence on the multilateral negotiations under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), as lobbyists and advocates for or against domestic climate action (e.g., Brandt & Svendsen, 2004), and not as autonomous agents and governors in their own right.

In 2008, Pattberg and Stripple questioned the research bias toward interstate negotiations and pointed to an ongoing “transnationalization” of global climate governance. The number of transnational governance arrangements—where non-state actors play an important role, sometimes in conjunction with public actors—such as the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and multi-stakeholder partnerships was growing rapidly. Consequently, researchers should expand their focus to include “agency beyond the state.” Fast forward to 2021, The Conference of the Parties (COPs) and the intersessional meetings to the UNFCCC remain important fieldwork sites for collecting data and carrying out research on, for instance, environmental NGOs (Dombrowski, 2010); indigenous peoples (Schroeder, 2010); or youth participation (Thew, 2018), as well as broader questions of non-state actor participation in the negotiations (e.g., Nasiritousi & Linnér, 2014; Nasiritousi et al., 2016). However, the bias among global climate governance scholars toward interstate negotiations is waning and yielding to more pluralist perspectives. In this context, the coming section highlights three themes with regards to research on transnational actors and institutions in climate governance: (1) the expanding universe of transnational governance initiatives; (2) the expanding institutional space for transnational initiatives and non-state actors in the UNFCCC; and, (3) the impact and effectiveness of transnational climate governance on mitigation and adaptation.

2.1 The expanding universe of transnational governance initiatives

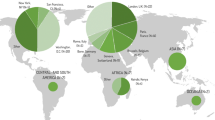

The first theme concerns the rapid growth in the number of new agents in transnational climate governance, in particular the growth in number of new initiatives. It is difficult to estimate the exact population of initiatives and agents, but when Bulkeley and colleagues (2012, 2014) finished a major study on transnational climate governance in 2012, they found 60 initiatives. Nine years later, the Climate Initiatives Platform—a UN supported database—lists 269 initiatives, representing a fourfold increase in the number of initiatives since 2012 (UN Environment, 2021). The emerging picture of a rapid growth in initiatives is confirmed by more specialized databases, e.g., on transnational adaptation initiatives or transnational city initiatives (e.g., Dzebo, 2019; Papin, 2019). Widerberg and colleagues (2016) found that nearly 10,750 cities, regions, companies, foundations, NGOs and other non-state and sub-national actors engaged in 89 transnational climate governance initiatives, and more recently, Hsu, Yeo, et al. (2020) released a dataset with over 10,000 cities that participate in transnational initiatives focusing on urban climate governance. The expanding universe of transnational initiatives has happened in parallel to a growth in international initiatives (between states). Keohane and Victor (2011, 12) has likened the process to a “Cambrian explosion,” alluding to a geological event some 540 million years ago resulting in a rapid increase in variety of species. The result is a dense institutional architecture of global climate governance marked by overlapping norms, discourses, and memberships (Widerberg, 2016; Zelli, 2011).

2.2 The new structure of global climate governance

The second theme concerns structure of the international climate regime complex, and the role of the UNFCCC in particular. Much research capacity has been devoted to scrutinizing alternative international arenas to the UNFCCC. The now defunct Asia–Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate (APP) is a case-in-point, as countries skeptical to the Kyoto Protocol (e.g., US and Australia) created a new partnership that was generally perceived as a potential threat to the UNFCCC’s authority (e.g., Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen & van Asselt, 2009). Researchers and other observers were worried that countries would engage in ‘forum shopping’ or ‘forum shifting’ (Kellow, 2012), challenging existing institutions and agreements (Falkner, 2015). After COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009 failed to produce a substantive outcome (Dimitrov, 2010), governments and the then new UNFCCC executive secretary Christiana Figueres initiated a change process to the institutional structure of the UNFCCC. They were supported by political scientists and economists making theoretical and empirical arguments for why a “global solution” and a “uniform approach” was likely to fail; instead one should opt for “bottom-up” and “polycentric” structures (Ostrom, 2010; Verbruggen, 2011; Victor, 2011). The change process came to fruition in the Paris Agreement in 2015, where governments agreed on a new structure to international climate governance, moving from what Hale (2016) calls a ‘“regulatory” model of binding, negotiated emissions targets to a “catalytic and facilitative” model that seeks to create conditions under which actors progressively reduce their emissions through coordinated policy shifts. Suddenly there was space for alternative arenas where countries could pursue their interests. The Paris Agreement, in particular the decision of COP21, also embraced a more visible role for non-state and sub-national actors, referred to as “non-Party stakeholders.” Parties to the convention were explicitly encouraged to collaborate with non-Party stakeholders; non-Party stakeholders were encouraged to share data with the UNFCCC via the Non-State Actor Zone for Climate Action platform (NAZCA); an annual high-level event was launched, building on the Lima-Paris Action Agenda set up in 2014; and, two “champions” were appointed to strengthen the connections between Parties and non-Party stakeholders (Hsu et al., 2018; Widerberg, 2017). The Paris Agreement and the COP21 decision thus further blurred the boundaries between international and the transnational spheres of global climate governance. The current institutional structure of global climate governance is thus marked by what Pattberg and Stripple call “the inadequacy of the public/private dichotomy in political theory” (2008, 384), as the role of governments in addressing climate change globally is changing and a more diverse set of actors are engaging in climate action, often via hybrid and multi-stakeholder constellations.

2.3 The impact of transnational governance initiatives and non-state actors on global climate governance

The third theme concerns the impacts of a changing climate regime complex. Theorizing about how non-state actors and transnational governance initiatives are supposed to influence global climate governance is a central topic in research on impact (Widerberg and Pattberg 2015). For example, are non-state actors and transnational governance initiatives there to instill confidence, build momentum and support governments in taking ambitious climate actions (indirect influence), or are they to be seen as independent actors in their own right, mitigating and adapting to climate change (direct influence) (Widerberg, 2017)? The two pathways for influence resonate well with Downie’s (2016, 741) observation that there is a “two-level” game frame (referring to Putnam’s theory on the relationship between national and international politics), where “[t]he preferences of non-state actors are accounted for through the domestic polity”, and a system-level perspective, where international negotiations is one of many arenas for non-state and sub-national actors to influence governments. Hermwille (2018) brings both perspectives together by analyzing interdependencies between the international and the transnational levels of global climate governance using structuration theory (Giddens, 1984). The idea is to foster feed-back loops between the national, transnational and international levels of climate governance to create a momentum toward increased action.

The second topic has been on how to measure impact empirically. As GHG emissions continue to rise unabated on a global level, it is tempting to jump to the conclusion that transnational initiatives have done little to break the negative trend. However, few studies actually attempt (and succeed) to isolate and measure the impact of transnational initiative on emission reduction (but see Hsu, Tan, et al., 2020 and Hale et al, 2021, for an overview). The literature instead understand term ‘impact’ in a multifaceted way where effectiveness, i.e., whether the proliferation of initiatives and actors, and the ‘bottom-up’ structure actually leads to reduced greenhouse gas emissions and adaptation, is but one aspect and most authors suggest a separation between output, outcome, and impact level effectiveness (Chan et al., 2018; Dzebo, 2019). One measure of impact is to what extent countries have included transnational initiatives and non-state actors in their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). A study by Hsu, Brandt, et al. (2019) demonstrates that this is generally not the case, however, developing countries are more prone to mention cities, regions and companies in their NDCs compared to developed countries, in particular in the context of adaptation. Studies that estimate impact at the level of GHG emissions focus on potential impact, i.e., what hypothetically could happen if an initiative reaches its goals. Researchers have used newly available data for assessing their impact on global climate governance, mitigation and adaptation, and developed new protocols and methodologies for streamlining the research efforts (e.g., Hsu, Höhne, et al., 2019; Lui et al., 2020). A recurring challenge to understanding the impact of transnational climate governance initiatives is the lack of information necessary to assess important aspects such as goal-attainment (Widerberg & Stripple, 2016). Other types of impact have been suggested by, for instance, Jacobs (2016) argues that a coalition of civil society actors contributed to the successful outcome of COP15 in Paris, by putting pressure on governments to reach an agreement. In sum, despite convincing evidence that the transnationalization of global climate governance has accelerated, we know little about its impact on halting and adapting to dangerous climate change; however, a broader perspective on effectiveness suggests that transnational initiatives do have impact in various ways.

Looking ahead, the transnationalization of global climate governance seems to be accelerating rather than decelerating. More companies, investors, cities, regions, faith-based organizations and other non-state and sub-national actors are making public commitments and joining transnational initiatives on climate mitigation and adaptation. The UNFCCC is prolonging mandates for the High-level champions and expanding the NAZCA database. Civil society organizations and advocacy groups such as Fridays for Future and the Extinction Rebellion are ramping up pressure on governments and other actors to take ambitious climate action. For researchers and other observers, the question of effectiveness is an elusive one. On the one hand, conclusive evidence is scarce whether individual initiatives and actions have led to reduced GHG emissions or concrete adaptation. On the other hand, it is plausible to assume that transnational climate action contributed to the adoption of the Paris Agreement), and that in an counter-factual scenario—where multi-stakeholder partnerships and non-state and sub-national climate action are absent—the pressure on governments to take on ambitious climate goals and policies would have been lower.

3 From governance fragmentation to complexity

Another key innovation in global environmental governance scholarship is the focus on the broader institutional system of environmental governance under the heading of ‘governance architecture.’ Biermann and colleagues defined governance architecture in their 2009 seminal article as “…the overarching system of public and private institutions that are valid or active in a given issue area of world politics” (Biermann et al., 2009, 15) and introduced ‘fragmentation’ as a central analytical category. Questions relating to the role and relevance of fragmentation of governance architectures, its drivers and implications and subsequent management options in and beyond the climate governance arena gained prominence over the last decade (see for example van Asselt & Zelli, 2014). However, researchers are increasingly realizing the limitations of established analytical frameworks and ontologies to study governance architectures and are consequently searching for alternative framings. Complexity has emerged in recent years as one such an overall integrative framing for fragmentation research. In this section, we first summarize some generic findings of the fragmentation literature (as far as it relates to sustainability and climate change) and second review complexity-informed research on climate governance.

3.1 Fragmented climate governance: key findings

A recent meta-analysis (see Heidingsfelder & Beckman, 2020) has screened 134 publications related to fragmentation and sustainability governance and found convergence in the literature mostly around the specific management approaches to fragmentation, identified as coordination, convergence and integration, and meta-governance. Beyond the important question of how to manage fragmentation (see for example Zelli & van Asselt, 2013), other issues have been addressed as well. Relevant academic contributions have been made over the last two decades relating to: emergence and drivers of fragmentation (e.g., Oh & Matsuoka, 2015), the empirical pervasiveness, depth and relevance of fragmentation (e.g., Pattberg & Widerberg, 2020), and its implications (e.g., Hackmann, 2012). We will briefly summarize relevant contributions in each of these areas.

In an early application of the fragmentation concept in empirical analysis, Hof and Colleagues (2009, 58) study various possible climate governance architectures using a quantitative modeling approach related to effectiveness and distribution. Their study concludes that “stabilising GHG concentrations at low levels is generally more costly in a fragmented regime, either because ambitious reduction targets must be achieved by a smaller number of countries or because emission reductions do not take place where it is cheapest to do so” (Hof et al., 2009, 58). This study serves as an important reminder that fragmentation is not only a conceptual innovation, but also allows for precise quantitative analysis when it comes to expected outcomes.

Other studies have focused on linking fragmentation to sub-optimal governance performance and the subsequent question of fragmentation management. Hackmann (2012), for example, analyzes the emerging governance architecture of climate change in international shipping, hypothesizing “that the degree and the characteristics of governance fragmentation have a crucial impact on the effectiveness and performance of a governance system” (Hackmann, 2012, 87). The study in particular highlights the role that institutional fragmentation with regards to nesting overlaps between decision-making systems and norm conflicts play in producing sub-optimal governance outcomes (Hackmann, 2012, 100).

On the important question of fragmentation management, Gupta et al. (2015) illustrate the central role that multi-stakeholder partnerships play as ‘bridge organizations’ in managing governance fragmentation. Empirically situated in at the nexus of forest and climate governance, the study analyzes the increased institutional fragmentation in the REDD + domain and interrogates possible management approaches, in particular related to enhancing transparency, participation, knowledge sharing and coordination (Gupta et al., 2015, 370). The authors (2015, 371) highlight in particular the role that political contestation and the broader normative conflicts that shape the overall global environmental governance architecture play in explaining fragmentation management and its limitations. As a consequence, a robust finding of the ‘managing fragmentation ‘ literature in global environmental governance is the recommendation to focus on improving the management of fragmentation as opposed to redesigning governance structures to reduce fragmentation, as the latter are affected by system-level political dynamics (see Zürn & Faude, 2013).

Another group of studies has attempted to shed light on the dynamic interactions, or interplay, among the many institutions, both international and transnational, that aim at governing global environmental change. For example, Gomar (2016, 526) scrutinizes the factors “determining the quality of interplay management and the achievement” in the international biodiversity governance cluster, comprising of the Convention for Biological Diversity along with five specialized international regimes. Hoch and Colleagues (2019) are also interested in interplay, this time related to international climate governance. Utilizing the typology of Biermann and Colleagues (2009) that distinguished between synergistic, cooperative and conflictive fragmentation, the study analyzes the interplay between the Paris Agreement, the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol and CORSIA (Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation). One important finding is that equal stringency reinforced cooperative fragmentation (Hoch et al., 2019, 611).

Yet another line of research is represented by Oh and Matsuoka (2017), who scrutinize the emergence of institutional fragmentation in the climate change arena from a constructivist perspective. A key observation here is that fragmentation can arise out of normative contestations of key international norms, often motivated by strategic considerations. The example explored in Oh and Matsuoka (2017) is the establishment of the Asia–Pacific Partnership on Clean Development and Climate (APP), under the leadership of the USA, building a counter-narrative to the mandatory emission reduction approach of the Kyoto Protocol (KP). Earlier work on the APP published in INEA by Karlsson-Vinkhuizen and van Asselt (2009) has reached similar conclusions, highlighting also the implications fragmentation has for effectiveness and legitimacy of global climate governance.

Finally, research has also attempted to measure the fragmentation of global governance architectures. Building on a standardized methodology, Pattberg and colleagues have provided measurements for the degree of institutional fragmentation for the issue areas of climate change, energy, biodiversity, forestry and fisheries (see Widerberg et al., 2016; Negacz et al., 2020; Pattberg & Widerberg, 2020).

3.2 Governance complexes and governance complexity

After having discussed scholarship building on the initial interest for questions around governance architecture discussed in this journal (see, e.g., Pattberg & Stripple, 2008), we now turn to a related debate that has unfortunately received much less attention in the pages of INEA: the interest in climate governance complexes and complexity. While undoubtedly there has been progress in the study of international institutions, in particular by moving ‘beyond the state’ (see Sect. 5) and by analyzing interplay and interlinkages (see Kalaba et al., 2014), little attention has been paid to system-wide interactions and the emerging complexity in and of global environmental governance in general and climate governance in particular. While scholars have noted “the presence of nested, partially overlapping, and parallel international regimes that are not hierarchically ordered” (Alter & Meunier, 2009) and referred to these structures as “regime complexes” (Keohane & Victor, 2011; Raustiala & Victor, 2004), few scholars have attempted to utilize insights from complexity theory for the study of global environmental governance in general and climate governance in particular. However, this situation is now changing.

In a recent forum in International Studies Review, Orsini and Colleagues (2020) argue for embracing the complexity of world politics analytically, by utilizing insights from the broad school of complexity science (for a similar argument, see Zelli et al., 2020). For Orsini et al., (2020, 1011), world politics, including sustainability and climate change, is best addressed as a complex system, with open boundaries, emergent properties, and self-organizing adaptive behavior (see also Kim, 2014, for an important contribution). Consequently, analyzing governance systems (i.e., governance architectures) as complex systems has two important implications (see Orsini et al., 2020, 1022). First, the focus on individual institutions gives way to studying interactions and interconnections, i.e., the bio-physical/social nexus between governance approaches. Second, when evaluating global governance systems, analysts need to take into account the complexity of the system. In other words: system level performance is not the same as additive performance.

Beyond being used as a generalized description of reality (and then often confused with complicated), complexity has rarely been applied to global environmental governance in general and climate governance in particular. A noteworthy exception is Pattberg and Widerberg’s (2019, 2021) attempt to show that the global climate governance architecture has properties of a complex system and should consequently be analyzed using insights from complexity science. Taking seriously the implications that derive from properties of complex systems, such as nonlinearity and emergence, the prospects for management and orchestration (Chan & Amling, 2019) of governance architectures in a top-down fashion are slim, given that learning, adaptation, self-organization, and feedbacks are central to complex systems. This in turn calls into question overly optimistic plans to reduce conflicts and increase synergies within the ever-expanding field of global climate governance.

4 The normative turn and global climate change governance

The growing role of transnationalism in GEG opens up questions not only of effectiveness, but also of equity (Pattberg & Stripple, 2008). While the increasing fragmentation and diversification of global governance systems is in part a direct and potentially positive response to issues of uneven access, allocation and inclusion, it simultaneously has the potential to exacerbate these very injustices (Okereke, 2018). The increasing complexity of GEG architectures at large, and global climate change governance in particular, therefore point at a growing need to revisit those more normative questions pertaining to issues of equity and justice.

While the notion of ‘normative GEG scholarship’ does not do justice to the breadth and diversity of existing discussions, a concise overview of the state-of-the-art necessitates an umbrella term for the sake of clarity. Indeed, in their study into the diverging conceptualizations and operationalizations of ‘justice’ in GEG scholarship, Dirth et al. (2020) emphasize that this sub-field in environmental scholarship engages with a rich but complex vocabulary. Key concepts include, but are not limited to, justice, equity, and fairness (e.g., Dirth et al., 2020), access and allocation (e.g., Gupta & Lebel, 2010), and accountability and legitimacy (e.g., Biermann & Gupta, 2011).

4.1 Equity and effectiveness at a crossroads

Whether the growing attention to issues of justice is beneficial to the effectiveness of governance initiatives, however, has been the subject of deep-seated disagreements. At the turn of the century, Kemfert and Tol (2002) identified a gap in the literature concerning the interplay between efficiency and equity in GHG reduction efforts. In his study into emissions trading under the Kyoto Protocol, Bohm (2002) demonstrates how the deliberate facilitation of developing country participation in emissions trading schemes is beneficial to cost-effective GHG reduction. Barrett and Stavins (2003) argue against this, instead maintaining that cost-effectiveness and widespread participation are oftentimes conflictive. Whether equity should be treated as a means to the end of effectiveness or vice versa, therefore, is a contended topic of discussion. “For many regime analysts”, argue Vellinga and Colleagues (2002, 296), “environmental governance should not attempt to solve all issues in one go.”

Indeed, in 2010, Posner and Weisbach argued that a radical orientation on distributive and intergenerational justice comes at the expense of effective climate change action. ) carried this argument forward in his keynote address at the 2016 Berlin Conference on Transformative Global Climate Governance ‘après Paris.’ He additionally argued that scholars ought to prioritize research into real-world political action over “articulating a normative-philosophical view of ethical climate policy” (Keohane, 2016a).

In response, 18 scholars from diverse institutions across the world wrote a plea to encourage more, not less, research on equity and justice in GEG scholarship (Klinsky et al., 2017). First and foremost, Klinsky and Colleagues (2017, 171) argue that neglecting issues of equity and justice is in direct conflict with the research community’s obligation “to do intellectually rigorous work on issues affecting human wellbeing.” They further maintain that political research requires an understanding of existing interpretations of- and claims to justice, not least when assessing trade-offs, and that normative considerations are not necessarily at odds with effective climate action. In his response to this plea, Keohane (2016b) clarified that he agrees that academic research into equity and climate change is important, but nevertheless remains “cautious” to emphasize justice—an end he believes to be unrealistic.

4.2 Toward justice: potentialities and pitfalls of “green growth”

These ongoing disagreements did not restrain the expansion of normative scholarship since the launch of INEA. Noteworthy topics of inquiry include the energy transition (Carley & Konisky, 2020; Meadowcroft, 2009), the cap-and-trade system upheld by the UNFCCC regime (Méjean et al., 2015), the distributive practice of determining carbon emission rights (Caney, 2009; Duus-Otterström & Hjorthen, 2019) and carbon trading and -taxation practices (Aldred, 2012; Hammar & Jagers, 2007; Jagers & Hammar, 2009). The normative considerations associated with these practices are embedded within wider concerns over neoliberal and/or market-regulated climate change governance practices, including climate voluntarism, business environmentalism and transnationalism at large (Castro, 2016; Okereke, 2018). Evidently, tensions between economic growth and efficiency on the one hand and the pursuit of environmental and ecological justice on the other are a recurring theme in normative GEG scholarship.

INEA explored these tensions in detail in a special issue on environmental justice and the pursuit of a ‘green economy’ (Okereke & Ehresman, 2015). Described as a potential ‘paradigm shift’ (Bowen & Fankhauser, 2011), defendants of this model pursue economic development practices that are environmentally and ecologically sustainable and climate-resilient. Whether this ‘green economy’ and environmental justice are symbiotic, however, remains uncertain. Studies into labor union environmentalism (Stevis & Felli, 2015), the salience of ‘green growth’ in marginalized urban areas (McKendry & Janos, 2015) and socio-environmental activism in the Amazon (Bratman, 2015) all point at a need to more carefully consider all dimensions of justice, as well as the potentiality of the ‘green growth’-narrative as a means to override marginalized peoples’ claims to justice.

4.3 Understanding equity post-Paris

Not long after the publication of this special issue, the 2015 Paris Agreement proved decisive in determining the future directions of normative GEG scholarship. Some believe the Paris Agreement, given its departure from the developed-developing dichotomy and its emphasis on voluntarism and universalism, marks the beginning of a “post-equity” era (found in Klinsky et al., 2017, 170). Still, Okereke and Coventry (2016, 846–7) are cautious of the regime’s “trend toward voluntary commitments” and maintain that “suggestions that the new pledge and review system has sidestepped the contentious justice debates […] cannot but be described as simply naïve and wishful thinking.” The Agreement’s simultaneous emphases on climate justice on the one hand and market mechanisms on the other have also been the subject of scrutiny (Shrivastava & Bhaduri, 2019).

INEA addresses these concerns in their special issue on ‘Achieving 1.5 °C and Climate Justice’ (Dooley et al., 2018). For instance, Lahn (2018, 30) identifies a distinct tension between “the common temperature goal of 1.5 °C, and the differentiated goal of equity […] as two parallel objectives.” Particularly, striking is how the Paris Agreement redirects the normative narrative through its Pledge and Review system, within which countries ought to defend the ‘fairness’ of their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) in light of their capabilities and overall contribution to the problem (see Winkler et al., 2018). Holz, Kartha, and Athanasiou (2018) identify an evident ambition gap, in particular on the part of wealthier countries, and contend that “dual obligations” for both wealthier and poorer countries are the only way forward to align differentiations in NDCs with achieving the overall 1.5 °C goal in time, again emphasizing the tensions between equity and effectiveness.

Another line of research explores the normative implications of the potential ‘technologies of the future’ including geoengineering (Faran & Olsson, 2018; Flegal & Gupta, 2018) and negative emissions technologies (NETs) (Dooley & Kartha, 2018). The risks and ethical ‘grey areas’ associated with these technologies are manifold and warrant further research. According to Tallberg and colleagues (2018, 244–5), the global governance community faces a distinct tension between two dominant legal norms, namely ‘precaution’ (for the potentially harmful consequences of these technologies) and ‘harm minimisation’ (of the detrimental impacts induced by global warming). In addition, as Faran and Olsson (2018, 66) point out, “the question is not only how we decide on the use of particular forms of climate engineering, but who decides.” Indeed, Biermann and Möller (2019) identify a distinct underrepresentation of developing countries in climate engineering negotiations.

Nevertheless, geoengineering solutions could serve to correct lasting imbalances in the access to environmental goods (including the opportunity to secure basic human needs) and the global allocation of these goods (Gupta & Lebel, 2010). A recently published special INEA issue on ‘Access and Allocation in Earth System Governance’ (Gupta & Lebel, 2020) reveals, however, just how systemic the forces behind these inequities are. Global trade and investment schemes, industry-related financial flows, and other forms of transnational and market-regulated governance prove considerably decisive in determining the access to and allocation of environmental goods and burdens (Gonenc et al., 2020; Gupta et al., 2020; Kalfagianni, 2014). This, again, points at a need to integrate all dimensions of justice in our assessment of environmental and climate justice, and, empirically, highlights the necessity of a closer integration of the Paris Agreement on the one hand, and the 2030 Agenda’s Sustainable Development Goals on the other (Ivanova et al., 2020).

4.4 Normative GEG: a research agenda

What the special issue edited by Gupta and Lebel (2020) also highlights, however, are the notable advances made in normative GEG research over the years (Kalfagianni & Meisch, 2020). Nevertheless, many scholars maintain that the overall engagement with issues of justice on the part of the global research community remains relatively marginal and warrants more research, in particular on those more substantive questions of justice (Dirth et al., 2020; Kalfagianni & Meisch, 2020). This includes more rigorous work on the discrepancies in existing conceptualizations and operationalizations of those concepts central to normative GEG debates (see Klinsky & Dowlabati, 2009; Schlosberg, 2013; Dirth et al., 2020; Kalfagianni & Meisch, 2020).

A new research framework proposed by Biermann and Kalfagianni (2020) is a likely contender to carry this line of research forward. Recognizing the diverse interpretations of ‘justice’ in GEG, the authors propose to adopt the notion of ‘planetary justice’ over conceptions of, among others, environmental justice. The overall aim is to redirect the discussion “from a normative debate on planetary justice (‘what is just?’) toward an empirical debate on what conceptualizations of justice different actors in global environmental politics actually support” (Biermann & Kalfagianni, 2020, 2). The question remains whether future research efforts sufficiently take into consideration potential trade-offs between justice and effectiveness (Klinsky et al., 2017) and succeed in refraining from treating either of the two as ends in themselves. Nevertheless, treating the study of equity and justice as an empirical project instead of a normative one might provide common ground between Keohane (2016a) and Klinsky et al. (2017) that is beneficial for carrying this line of research forward.

Of particular importance is to direct more attention to transnational actors as potential facilitators of (or obstacles to) a positive relationship between equity and effectiveness. While transnational regimes indeed offer more space for inclusion, it is imperative to remember that the turn to transnational governance, as it has been observed across multiple governance domains, can be seen as the result of neo-liberalization (Bulkeley et al., 2014, chapters 3–4), which, according to Okereke (2018, 331) is ethically “not compatible with more radical interpretations of climate justice.” That transnational actors have been effective in reorienting climate change governance both horizontally and vertically, thereby considerably reshaping a previously predominantly top-down system is certain (Bulkeley et al., 2014, chapter 8). That this happens equitably, is not. Whether the transnational governance arena will become a space where effective and equitable climate change mitigation become naturally symbiotic, then, remains for future research to discern.

5 Conclusions: the road beyond ‘climate governance beyond the state’

Having discussed three distinct conceptual, theoretical and empirical contributions that emerged on the topic of global climate governance within the pages of INEA, we now engage in some introspective reflection to identify areas in need of theoretical attention in the decade to come. Twenty years ago, during the early 2000s, scholars coming from the discipline of International Relations (IR) discovered ‘climate governance beyond the state,’ i.e., governing accomplished by a range of actors, such as insurance companies, administrative certification institutions, standard-setting organizations, networks of cites, multi-stakeholder partnerships for energy, and divestments movements. IR’s journey ‘beyond the state’ has been a productive one, with lots of important discoveries, some discussed in this contribution. But as with many journeys, some of the most profound discoveries relate to ourselves. As you travel, if you are not really sure where you are heading, you will at least know more about where you were coming from.

As IR had left the sovereign state, the entities it encountered ‘beyond the state’ were depicted to be ‘non-state.’ This simple stating of what the entities were not—they were not states—illuminated as much as it obscured. IR went on its travel with some conceptual baggage (assumptions about sovereign authority) that it had to carry. Eventually, IR could offload some of that weight and learned a lot about the diversity and multiplicity of non-state actors. A rich and variegated account of the realm of non-state governance emerged (e.g., Bulkeley et al., 2014). In the face of the stalemate in the intergovernmental negotiations after Kyoto, a lot of hope was invested in the possibility for cities, citizen groups, and corporations to deliver in the absence of the state (Hoffman, 2011). Of course, corporate responses were also met with large suspicion. Already at the Rio Summit in 1992, when transnational companies were recognized as key actors in the battle to save the planet, Hildyard (1993) commented that this was akin to putting the “foxes in charge of the chickens.” Consequently, the question about corporations became a question not just about the agency of particular non-state actors, but a larger question about structure: can capitalism effectively respond to climate change? Could new alliances and coalitions in the private realm initiate a new form of capitalism that is able to deliver growth on a low-carbon basis (Newell & Paterson, 2010)? In an influential book, Klein (2014) argues that capitalism can only be fundamentally changed, if the civil-sphere (climate activism and social justice movements) unites behind an alternative worldview embedded in “interdependence rather than hyper-individualism, reciprocity rather than dominance, and cooperation rather than hierarchy” (Klein, 2014,462). Klein’s argument that ‘everything must change’ is thus not just about corporate actors and governments, but about the culture of the civil-sphere, what we can hope for and what we can demand from ourselves.

In parallel to the question of corporate actors, other fundamental theoretical issues have also come to the fore. While early writings on ‘climate change beyond the state’ traced the ways in which climate change started to become a matter of concern for more actors than environment ministries at international environmental summits, certain assumption about ‘the international’ as a particular space has limited IRs capacity to follow the climate deeper into social, cultural and material realms (Bulkeley et al., 2016). Today climate change is everywhere and is “an idea as ubiquitous and powerful in today’s social discourses as are the ideas of democracy, terrorism, or nationalism” (Hulme, 2009, 322). There is hardly any site in the contemporary world that is untouched by this idea, from how forests are managed, to what goes on in the farm and in the reconfiguration of urban environments. It is right there in the financial circuits, in plastics production facilities, clothing retailers and in public transport. It is unavoidable in discourses of holiday travel and has left its imprint on the varieties of milk at the local café. Hence, it is no longer meaningful to draw neat boundaries around the international politics of climate change as something which occurs, e.g., in the UN, and the everyday practices of eating, traveling, or shopping (Methmann et al., 2013).

In their recent book, Adler and Pouliot (2011) invite students of international relations to view world politics through the lens of its manifold practices. Their approach is about tracing the “doing” of world politics in and on the world. But what does such an approach mean for students of climate governance in the early 2020s? While the broadening of climate governance that emerge during the early 2000s was useful, it also tended to obscure the ways in which climate change has emerged everywhere. The question now becomes if the concept of climate governance can still describe and capture how we increasingly govern ourselves and others in relation to climate change. Climate governance, when approached too much in a general fashion, risks becoming an empty concept. Is it the same kind of governance that recur across sites? Or are these sites governing the climate in distinctive ways? Various forms of critical scholarship have argued that the manifold of sites involved in the governing of climate change cannot be brought into the same view. The politics will be different in each of them because power in intrinsic and emergent within those sites and not a resource to be deployed from the outside (Stripple & Bulkeley, 2014).

While global climate governance scholarship has excelled in engaging a much broader range of actors, it has been less focused on revisiting fundamental assumptions about how governing is accomplished in the absence of the state. A renewed engagement with such issues requires, however, that fundamental assumptions about power and authority are brought back into the foreground. Rather than assuming that particular actors or institutions hold power, as if it was a material resource, scholars should instead elucidate “how different locales are constituted as authoritative and powerful, and how different agents are assembled with specific powers, and how different domains are constituted as governable and administrable” (Dean, 1999, 29).

Traditions within social science that draw on structural and productive theories of power suggest that we should instead view governing as a practice and analyze the techniques that work through diffuse social relations to create, sustain, or disrupt particular socio-technical orders (Barnett & Duvall, 2005; Murray Li, 2007). If greenhouse gas emissions are produced and embodied in processes that work through global production chains, circuits of investment, the provision and use of infrastructure networks, and the consumption of a range of goods and services, then IR need to be prepared for new encounters (Bulkeley et al., 2018). Developing new accounts of climate governance requires, for example, utilizing analytical perspectives that highlight the material and spatial essences of these sites, scales, and socio-technical systems (Bridge et al., 2013; Rice, 2010).

While the question of power is central to how contemporary forms of governance emerge, new kinds of scholarship have also started to explore the power of visions of post-fossil futures to shape action in the present (e.g., Jasanoff & Kim, 2015; Yusoff & Gabrys, 2011). To grasp the role of imagination in the making of climate politics, a growing group of scholars are turning their attention to the concept of imaginaries (e.g., Hajer & Versteeg, 2019; Oomen et al., 2021; Pelzer & Versteeg, 2019). Overall, however, the process of translating imagined futures into action remains relatively underexplored and should therefore become a focus for future research.

To conclude, 20 years after the publication of the first issue of INEA, global climate governance scholarship has developed from a niche to a thriving school of thought within the broader confines of global environmental governance. In this article, we have highlighted three contemporary debates that have taken shape within the pages of INEA: agency beyond the state, governance complexity, and the normative turn in climate governance scholarship. What have we now learned for the next critical decades of climate governance practice in terms of the role and relevance of climate action? A short summary such as this one cannot do justice to the varied research conducted on the three themes discussed in this article. A singular answer to the question ‘does global climate governance work?’ is hard to give. Nonetheless, what seems to be emerging across the three research arenas sketched here is an understanding that focusing on the individual agency of a certain actor, the performance of a distinct governance arrangement, or the question of legitimacy and accountability of specific governance instruments employed in the fight against climate change falls short understanding global climate governance for what it is. A complex and adaptive system that is changing in a nonlinear and often quite unpredictable fashion. To successfully assess the problem-solving as well as normative performance of climate governance today, including important sub-questions such as the effectiveness of carbon markets, we need to embrace a holistic perspective on governance. A next generation of global climate governance scholarship will need to advance both new tools and concepts that allow comprehensive studies to be undertaken, while at the same time being attentive to the particularities, materialities and subjectivities of/in the contemporary world. At the time of the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment held in Stockholm in 1972, we might not have solved all governance-related questions of climate change; what we have achieved, however, is a robust understanding of its structural features, its key agents, the scope conditions for success, as well as the limits of our ability to predict and steer in light of new insights from complexity research. All in all, this is a solid achievement.

References

Adler, E., & Pouliot, V. (2011). International practices: Introduction and framework. In E. Adler & V. Pouliot (Eds.), International practices (pp. 3–35). Cambridge University Press.

Aldred, J. (2012). The ethics of emissions trading. New Political Economy, 17, 339–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2011.578735

Alter, K., & Meunier, S. (2009). The politics of international regime complexity. Perspectives on Politics, 7(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592709090033

Bäckstrand, K., Kuyper, J. W., Linnér, B.-O., & Lövbrand, E. (2017). Non-state actors in global climate governance: From Copenhagen to Paris and beyond. Environmental Politics, 26(4), 561–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2017.1327485

Barnett, M., & Duvall, R. (2005). Power in International Politics. International Organization, 59(1), 39–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3877878

Barrett, S., & Stavins, R. (2003). Increasing participation and compliance in international climate change agreements. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 3, 349–376. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:INEA.0000005767.67689.28

Biermann, F., & Gupta, A. (2011). Accountability and legitimacy in earth system governance: A research framework. Ecological Economics, 70(11), 1856–1864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.04.008

Biermann, F., & Kalfagianni, A. (2020). Planetary justice: A research framework. Earth System Governance, 6, 100049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2020.100049

Biermann, F., & Möller, I. (2019). Rich man’s solution? Climate engineering discourses and the marginalization of the Global South. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 19, 151–167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-019-09431-0

Biermann, F., Pattberg, P., van Asselt, H., & Zelli, F. (2009). The fragmentation of global governance architectures: A framework for analysis. Global Environmental Politics, 9, 14–40. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2009.9.4.14

Bohm, P. (2002). Improving cost-effectiveness and facilitating participation of developing countries in international emissions trading. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 2, 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021391431206

Bowen, A., & Fankhauser, S. (2011). The green growth narrative: Paradigm shift or just spin? Global Environmental Change, 21, 1157–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.07.007

Brandt, U. S., & Svendsen, G. T. (2004). Rent-seeking and grandfathering: The case of GHG trade in the Eu. Energy & Environment., 15(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1260/095830504322986501

Bratman, E. (2015). Passive revolution in the green economy: activism and the Belo Monte dam. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 15, 61–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9268-z

Bridge, G., Bouzarovski, S., Bradshaw, M., & Eyre, N. (2013). Geographies of energy transition: Space, place and the low-carbon economy. Energy Policy, 53, 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2012.10.066

Bulkeley, H., Andonova, L. B., Bäckstrand, K., Betsill, M., Compagnon, D., Duffy, R., Kolk, A., Hoffmann, M., Levy, D., Newell, P., Milledge, T., Paterson, M., Pattberg, P., & VanDeveer, S. D. (2012). Governing climate change transnationally: Assessing the evidence from a database of sixty initiatives. Environment and Planning-Part C, 30, 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1068/c11126

Bulkeley, H., Andonova, L. B., Betsill, M., Compagnon, D., Hale, T. N., Hoffmann, M. J., Newell, P., Paterson, M., Roger, C., & VanDeveer, S. D. (2014). Transnational climate change governance. Cambridge University Press.

Bulkeley, H., Cooper, M., & Stripple, J. (2018). Encountering climate’s new governance. In P. Dauvergne & J. Alger (Eds.), A Research agenda for global environmental politics (pp. 137–148). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bulkeley, H., Paterson, M., & Stripple, J. (2016). Towards a cultural politics of climate change: Devices. Cambridge University Press.

Caney, S. (2009). Justice and the distribution of greenhouse gas emissions. Journal of Global Ethics, 5(2), 125–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449620903110300

Carley, S., & Konisky, D. M. (2020). The justice and equity implications of the clean energy transition. Nature Energy, 5, 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-020-0641-6

Castro, P. (2016). Common but differentiated responsibilities beyond the nation state: How is differential treatment addressed in transnational climate governance initiatives? Transnational Environmental Law, 5(2), 379–400. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2047102516000224

Chan, S., & Amling, W. (2019). Does orchestration in the global climate action agenda effectively prioritize and mobilize transnational climate adaptation action? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 19, 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-019-09444-9

Chan, S., Falkner, R., Goldberg, M., & van Asselt, H. (2018). Effective and geographically balanced? An output-based assessment of non-state climate actions. Climate Policy, 18, 24–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2016.1248343

Dean, M. (1999). Governmentality: Power and rule in modern society. SAGE Publications.

Dimitrov, R. S. (2010). Inside Copenhagen: The state of climate governance. Global Environmental Politics, 10, 18–24. https://doi.org/10.1162/glep.2010.10.2.18

Dingwerth, K. (2007). The new transnationalism. Transnational governance and democratic legitimacy. PalgraveMcMillan.

Dirth, E., Biermann, F., & Kalfagianni, A. (2020). What do researchers mean when talking about justice? An empirical review of justice narratives in global change research. Earth System Governance, 6, 100042. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esg.2020.100042

Dombrowski, K. (2010). Filling the gap? An analysis of non-governmental organizations responses to participation and representation deficits in global climate governance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 10, 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9140-8

Dooley, K., Gupta, J., & Patwardhan, A. (2018). INEA editorial: Achieving 1.5 °C and climate justice. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 18, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-018-9389-x

Dooley, K., & Kartha, S. (2018). Land-based negative emissions: risks for climate mitigation and impacts on sustainable development. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 18, 79–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-017-9382-9

Downie, C. (2016). Prolonged international environmental negotiations: The roles and strategies of non-state actors in the EU. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16, 739–755. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-015-9292-7

Duus-Otterström, G., & Hjorthen, F. D. (2019). Consumption-based emissions accounting: The normative debate. Environmental Politics, 28(5), 866–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2018.1507467

Dzebo, A. (2019). Effective governance of transnational adaptation initiatives. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 19, 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-019-09445-8

Falkner, R. (2015). A minilateral solution for global climate change? On bargaining efficiency, club benefits and international legitimacy (No. 222/197). Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy/Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

Faran, T. S., & Olsson, L. (2018). Geoengineering: neither economical, nor ethical—a risk–reward nexus analysis of carbon dioxide removal. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 18, 63–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-017-9383-8

Flegal, J. A., & Gupta, A. (2018). Evoking equity as a rationale for solar geoengineering research? Scrutinizing emerging expert visions of equity. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 18, 45–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-017-9377-6

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. University of California Press.

Gomar, J. O. V. (2016). Environmental policy integration among multilateral environmental agreements: The case of biodiversity. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16, 525–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9263-4

Gonenc, D., Piselli, D., & Sun, Y. (2020). The global economic system and access and allocation in earth system governance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20, 223–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-020-09472-w

Gupta, A., Pistorius, T., & Vijge, M. J. (2015). Managing fragmentation in global environmental governance: The REDD+ Partnership as bridge organization. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16, 355–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-015-9274-9

Gupta, J., & Lebel, L. (2010). Access and allocation in earth system governance: Water and climate change compared. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 10(4), 377–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9139-1

Gupta, J., & Lebel, L. (2020). Editorial access and allocation in earth system governance. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20, 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-020-09485-5

Gupta, J., Rempel, A., & Verrest, H. (2020). Access and allocation: the role of large shareholders and investors in leaving fossil fuels underground. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20, 303–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-020-09478-4

Hackmann, B. (2012). Analysis of the governance architecture to regulate GHG emissions from international shipping. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 12, 85–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-011-9155-9

Haje, M., & Versteeg, W. (2019). Imagining the post-fossil city: Why is it so difficult to think of new possible worlds? Territory, Politics, Governance, 7(2), 122–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2018.1510339

Hale, T. N. (2016). “All Hands on Deck”: The paris agreement and nonstate climate action. Global Environmental Politics, 16, 12–22. https://doi.org/10.1162/GLEP_a_00362

Hale, T. N., Chan, S., Hsu, A., Clapper, A., et al. (2021). Sub- and non-state climate action: a framework to assess progress, implementation and impact. Climate Policy, 21(3), 406–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1828796

Hall, R. B., & Biersteker, T. J. (Eds.). (2002). The emergence of private authority in global governance (p. 2002). Cambridge.

Hammar, H., & Jagers, S. (2007). What is a fair CO2 tax increase? Individual preferences for fair procedures for emission reductions in the transport sector. Ecological Economics, 61, 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2006.03.004

Hermwille, L. (2018). Making initiatives resonate: How can non-state initiatives advance national contributions under the UNFCCC? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 18, 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-018-9398-9

Hickmann, T., & Elsässer, J. P. (2020). New alliances in global environmental governance: How intergovernmental treaty secretariats interact with non-state actors to address transboundary environmental problems. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20, 459–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-020-09493-5

Hildyard, N. (1993). ’Foxes in charge of the chickens’. In W. Sachs (Ed.), Global ecology. Zed Books.

Hoch, S., Michaelowa, A., Espelage, A., & Weber, A. (2019). Governing complexity: How can the interplay of multilateral environmental agreements be harnessed for effective international market-based climate policy instruments? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 19, 595–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-019-09455-6

Hof, A. F., den Elzen, M. G. J., & van Vuuren, D. P. (2009). Environmental effectiveness and economic consequences of fragmented versus universal regimes: What can we learn from model studies? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 9, 39–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-008-9087-1

Hoffmann, M. (2011). Climate governance at the crossroads: Experimenting with a global response after Kyoto. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hsu, A., Widerberg, O., Weinfurter, A., Roelfsema, M., Chan, S., Luthekemoller, K., & Bakhtiari, F. (2018). Bridging the emissions gap - The role of nonstate and subnational actors. In UN Environment: The Emissions Gap Report 2018. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP).

Hsu, A., Höhne, N., Kuramochi, T., Roelfsema, M., Weinfurter, A., Xie, Y., Lütkehermöller, K., Chan, S., Corfee-Morlot, J., Drost, P., Faria, P., Gardiner, A., Gordon, D.J., Hale, Thomas N., T., Hultman, N.E., Moorhead, J., Reuvers, S., Setzer, J., Singh, N., Weber, C., & Widerberg, O. (2019b). A research roadmap for quantifying non-state and subnational climate mitigation action. Nature Climate Change, 9, 11-17. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-018-0338-z

Hsu, A., Brandt, J., Widerberg, O., Chan, S., & Weinfurter, A. (2019). Exploring links between national climate strategies and non-state and subnational climate action in nationally determined contributions (NDCs). Climate Policy, 20(4), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2019.1624252

Hsu, A., Tan, J., Ng, Y. M., et al. (2020). Performance determinants show European cities are delivering on climate mitigation. Nature Clinical Practice Endocrinology & Metabolism, 10, 1015–1022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-020-0879-9

Hsu, A., Yeo, Z. Y., Rauber, R., Sun, J., Kim, Y., Raghavan, S., Chin, N., Namdeo, V., & Weinfurter, A. (2020). ClimActor, harmonized transnational data on climate network participation by city and regional governments. Scientific Data, 7, 374. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-020-00682-0

Hulme, M. (2009). Why we disagree about climate change. Understanding Controversy, Inaction and Opportunity: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Ivanova, A., Zia, A., Ahmad, P., & Bastos-Lima, M. (2020). Climate mitigation policies and actions: access and allocation issues. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20, 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-020-09483-7

Jacobs, M. (2016). High pressure for low emissions: How civil society created the Paris climate agreement. Juncture, 22(4), 314–323.

Jagers, S. C., & Hammar, H. (2009). Environmental taxation for good and for bad: the efficiency and legitimacy of Sweden’s carbon tax. Environmental Politics, 18(2), 218–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010802682601

Jasanoff, S., & Kim, S.-H. (2015). Dreamscapes of modernity : sociotechnical imaginaries and the fabrication of power. The University of Chicago Press.

Kalaba, F. K., Quinn, C. H., & Dougill, A. J. (2014). Policy coherence and interplay between Zambia’s forest, energy, agricultural and climate change policies and multilateral environmental agreements. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 14, 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-013-9236-z

Kalfagianni, A. (2014). Addressing the global sustainability challenge: The potential and pitfalls of private governance from the perspective of human capabilities. Journal of Business and Ethics, 122, 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1747-6

Kalfagianni, A., & Meisch, S. (2020). Epistemological and ethical understandings of access and allocation in Earth System Governance: a 10-year review of the literature. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 20, 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-020-09469-5

Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. I., & van Asselt, H. (2009). Introduction: Exploring and explaining the Asia-Pacific partnership on clean development and climate. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 9, 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-009-9103-0

Kellow, A. (2012). Multi-level and multi-arena governance: the limits of integration and the possibilities of forum shopping. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 12, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-012-9172-3

Kemfert, C., & Tol, R. S. J. (2002). Equity, international trade and climate policy. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 2, 23–48. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015034429715

Keohane, R.O. (2016b). Keohane on climate: What price equity and justice? Climate Home News. Retrieved March 31, 2021, from http://www.climatechangenews.com/2016b/09/06/keohane-on-climate-what-price-equity-and-justice/

Keohane, R.O. (2016a). Post-Paris: Pledge and review and politics research (presentation slides). Keynote Address at the 2016a Berlin Conference on Global Environmental Change, Transformative Global Climate Governance apres Paris, Berlin, Germany, 24 May 2016a. Retrieved March 31, 2021, from http://www.berlinconference.org/2016a/wp-content/uploads/2016a/07/Keohane-Robert-O.pdf

Keohane, R. O., & Victor, D. G. (2011). The regime complex for climate change. Perspectives on Politics, 9(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592710004068

Kim, R. E., & Mackey, B. (2014). International environmental law as a complex adaptive system. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 14(1), 5–24.

Klein, N. (2014). This change everything climate vs. capitalism. Penguin Books.

Klinsky, S., & Dowlabati, H. (2009). Conceptualizations of justice in climate policy. Climate Policy, 9(1), 88–108. https://doi.org/10.3763/cpol.2008.0583b

Klinsky, S., Roberts, T., Huq, S., Okereke, C., Newell, P., Dauvergne, P., O’Brien, K., Schroeder, H., Tschakert, P., Clapp, J., Keck, M., Biermann, F., Liverman, D., Gupta, J., Rahman, A., Messner, D., Pellow, D., & Bauer, S. (2017). Why equity is fundamental in climate change policy research. Global Environmental Change, 44, 170–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2016.08.002

Lahn, B. (2018). In the light of equity and science: scientific expertise and climate justice after Paris. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 18, 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-017-9375-8

Lui, S., Kuramochi, T., Smit, S., Roelfsema, M., Hsu, A., Weinfurter, A., Chan, S., Hale, T., Fekete, H., Lütkehermöller, K., de Casas, M. J. V., Nascimento, L., Sterl, S., & Höhne, N. (2020). Correcting course: the emission reduction potential of international cooperative initiatives. Climate Policy, 21(2), 232–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2020.1806021

McKendry, C., & Janos, N. (2015). Greening the industrial city: equity, environment, and economic growth in Seattle and Chicago. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 15, 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9267-0

Meadowcroft, J. (2009). What about the politics? Sustainable development, transition management, and long term energy transitions. Policy Sciences, 42, 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11077-009-9097-z

Méjean, A., Lecocq, F., & Mulugetta, Y. (2015). Equity, burden sharing and development pathways: reframing international climate negotiations. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 15, 387–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-015-9302-9

Methmann, C., Rothe, D., & Stephan, B. (2013). Interpretive approaches to global climate governance: (De)constructing the greenhouse. Routledge.

Murray Li, T. (2007). The will to improve. Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Durham: Duke University Press.

Nasiritousi, N., Hjerpe, M., & Linnér, B.-O. (2016). The roles of non-state actors in climate change governance: Understanding agency through governance profiles. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16, 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9243-8

Nasiritousi, N., & Linnér, B.-O. (2014). Open or closed meetings? Explaining nonstate actor involvement in the international climate change negotiations. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 16, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9237-6

Negacz, K. E., Widerberg, O. E., Kok, M., & Pattberg, P. H. (2020). BioSTAR: Landscape of international and transnational cooperative initiatives for biodiversity: Mapping international and transnational cooperative initiatives for biodiversity. (Report; Vol. 20, No. 02). Institute for Environmental Studies (IVM). https://www.ivm.vu.nl/en/Images/R20-02_Technical_report_200428_tcm234-940214.pdf

Newell, P., & Paterson, M. (2010). Climate capitalism. Cambridge University Press.

Oh, C., & Matsuoka, S. (2017). The genesis and end of institutional fragmentation in global governance on climate change from a constructivist perspective. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 17, 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-015-9309-2

Okereke, C. (2018). Equity and justice in polycentric climate governance. In A. Jordan, D. Huitema, H. Van Asselt, & J. Forster (Eds.), Governing climate change: polycentricity in action? (pp. 320–337). Cambridge University Press.

Okereke, C., & Coventry, P. (2016). Climate justice and the international regime: before, during, and after Paris. Wires Climate Change, 7, 834–851. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.419

Okereke, C., & Ehresman, T. G. (2015). International environmental justice and the quest for a green global economy: introduction to special issue. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 15, 5–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-014-9264-3

Oomen, J., Hoffman, J., & Hajer, M. A. (2021). Techniques of futuring: On how imagined futures become socially performative. European Journal of Social Theory. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431020988826

Orsini, A., Le Prestre, P., Haas, P. M., Brosig, M., Pattberg, P. H., Widerberg, O. E., Gomez-Mera, L., Morin, J.-F., Harrison, N. E., Geyer, R., & Chandler, D. (2020). Forum: Complex systems and international governance. International Studies Review, 22(4), 1008–1038. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viz005

Ostrom, E. (2010). Polycentric systems for coping with collective action and global environmental change. Global Environmental Change, 20(4), 550–557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.07.004

Papin, M. (2019). Transnational municipal networks: Harbingers of innovation for global adaptation governance? International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 19, 467–483. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-019-09446-7

Pattberg, P. H., & Stripple, J. (2008). Beyond the public and private divide: remapping transnational climate governance in the 21st century. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 8, 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-008-9085-3

Pattberg, P. H., & Widerberg, O. E. (2019). Smart mixes and the challenge of complexity: the example of global climate governance. In J. van Erp, M. Faure, A. Nollkaemper, & N. Philipsen (Eds.), Smart mixes for transboundary environmental harm (pp. 49–68). Cambridge University Press.

Pattberg, P. H., & Widerberg, O. E. (2020). Global sustainability governance: Fragmented, orchestrated or polycentric? Civitas Europa, 452(2), 373. https://doi.org/10.3917/civit.045.0373

Pattberg, P. H., & Widerberg, O. E. (2021). World politics as a complex system: Analyzing governance complexity with network approaches. In G. Christou & J. Hasselbalch (Eds.), Global networks and european actors: Navigating and managing complexity (p. 34). Routledge.

Pelzer, P., & Versteeg, W. (2019). Imagination for change: The Post-Fossil City contest. Futures, 108, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2019.01.005

Raustiala, K., & Victor, D. G. (2004). The regime complex for plant genetic resources. International Organization, 58(2), 277–309.

Rice, J. L. (2010). Climate, carbon, and territory: Greenhouse gas mitigation in seattle, Washington. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 100(4), 929–937. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045608.2010.502434

Rosenau, J. (1997). Along the domestic-foreign frontier: Exploring governance in a turbulent world. Cambridge University Press.

Ruggie, J. (2004). Reconstituting the global public domain. Issues, actors, and practices. European Journal of International Relations, 10(4), 499–531.

Schlosberg, D. (2013). Theorising environmental justice: the expanding sphere of a discourse. Environmental Politics, 22(1), 37–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2013.755387

Schroeder, H. (2010). Agency in international climate negotiations: the case of indigenous peoples and avoided deforestation. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 10, 317–332. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-010-9138-2

Shrivastava, M. K., & Bhaduri, S. (2019). Market-based mechanism and ‘climate justice’: reframing the debate for a way forward. International Environmental Agreements: Politics, Law and Economics, 19, 497–513. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10784-019-09448-5