Abstract

Even though research on the influence of institutions on entrepreneurial activities has recently gained scholarly attention, most studies are quantitative cross-country analyses that assume response homogeneity. Qualitative single-country studies that provide deeper insights into institutional peculiarities are still rare, especially in the East Asian context. Based on qualitative data generated from semi-structured interviews, this study examines the institutional environment for entrepreneurship in South Korea and its latest changes to explain the recent wave of newly established corporations. Building on Scott’s distinction of institutional dimensions, this article demonstrates how significant changes in regulative institutions pushed forward by the Korean central government have decreased individual financial risks and have created a surge in business foundations. At the same time, normative institutions have remained almost unchanged, while changes of the cognitive institutional dimension in the form of entrepreneurship education are underway. The findings suggest that regulative institutions play a bigger role for entrepreneurial activities than cognitive or normative institutions, as people start a business despite unfavorable informal institutions. Theory should therefore reevaluate the importance and effective power of each institutional dimension on entrepreneurial activities. Policymakers who put high emphasis on regulative institutions should pay attention to potential moral hazards arising from generous support programs.

Resumen

Obwohl der Forschung über den Einfluss von Institutionen auf unternehmerische Tätigkeiten in den letzten Jahren mehr Beachtung geschenkt wurde, so sind die meisten Studien quantitative, länderübergreifende Studien, die einheitliche Reaktionen auf institutionellen Druck annehmen. Qualitative Länderstudien, die tiefere Einblicke in die institutionellen Besonderheiten gewähren, sind noch rar, insbesondere im ostasiatischen Kontext. Basierend auf qualitativen Daten, generiert durch halbstrukturierte Interviews, untersucht die vorliegende Studie das institutionelle Umfeld für Unternehmertum in Südkorea und seine Veränderungen. Ziel ist es, dadurch den Anstieg an Unternehmensgründungen in jüngster Zeit zu erklären. Aufbauend auf Scotts Unterscheidung institutioneller Dimensionen zeigt der Artikel, wie signifikante Änderungen der regulativen Institutionen, befördert durch die koreanische Zentralregierung, das individuelle Unternehmensrisiko vermindert und somit zu einem Anstieg der Gründungen geführt haben. Gleichzeitig blieben normative Institutionen fast unverändert, während sich kognitive Institutionen in Form von unternehmerischer Bildung im Änderungsprozess befinden. Die Erkenntnisse legen nahe, dass regulative Institutionen eine größere Rolle für Unternehmensgründungen spielen als kognitive und normative Institutionen. In theoretischer Hinsicht sollte die Relevanz und Effektstärke der jeweiligen institutionellen Dimensionen überdacht werden. Politiker, die den Fokus auf regulative Institutionen legen, sollten darauf achten, dass massive Unterstützungsprogramme keine Fehlanreize setzen und keine Moral-Hazard Probleme hervorrufen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Contributions of the Paper: The paper provides deeper insights into the three-dimensional institutional environment for entrepreneurship in Korea. It allows a better understanding of institutional elements, their origin, and recent changes.

Research questions/purpose: The purpose of this study is to examine Korea’s perceived institutional environment for entrepreneurship as an occupational choice among young Koreans with the goal of finding evidence for the rise in entrepreneurial activities.

Methodology: Qualitative study.

Database/Information : Semi-structured interviews with experts and entrepreneurs.

Results/Findings: Regulative institutions have improved noticeably and possess the most power over the occupational choice for entrepreneurship. Cognitive and normative institutions are still unfavorable and are not the main driver of entrepreneurial activities.

Limitations (If There Are Any): Low generalizability and impossibility of statistical inference.

Recommendations for further research: Further research should examine the role of cognitive and normative institutions to verify the hypothesis that they are not as crucial for the decision to start a business as regulative institutions. Qualitative studies should be conducted in other countries as well.

Managerial/Theoretical Implications: Formal institutions overrule informal institutions in encouraging entrepreneurship and they change quicker.Formal institutions overrule informal institutions in encouraging entrepreneurship and they change quicker.

Practical Implications and Recommendations as well as Public Policy Recommendations: Stronger awareness by the government of moral hazard issues is recommended.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship has been found to positively influence economic growth (Wennekers and Thurik 1999; Acs et al. 2012; Braunerhjelm et al. 2010; Audretsch et al. 2006). Growth-oriented (Stam and van Stel 2011) and opportunity-driven entrepreneurship in particular (Acs and Varga 2005) contribute to economic growth and job creation (Hathaway 2013). Therefore, examining and understanding the factors that drive entrepreneurial activities is vital. In recent years, research on the connection between institutions and entrepreneurship has increased (Bjørnskov and Foss 2016; Urbano et al. 2019), and many scholars have adopted the institutional theory of North (1990) and the approach by Scott (2014), who distinguishes between regulative, cognitive, and normative institutions. The general hypothesis is that institutions more conducive to entrepreneurship generate higher entrepreneurial activity and consequently improve the economic performance of a given country (Urbano and Alvarez 2014). Researchers often find that regulative institutions like strong property rights, business freedom, and fewer procedures to start a business positively influence entrepreneurial activities (Stenholm et al. 2013; Fuentelsaz et al. 2015). Cognitive institutions like skills and knowledge about doing business are also found to be beneficial (Valdez and Richardson 2013; Urbano and Alvarez 2014; Aparicio et al. 2016). Others find normative factors like the belief that entrepreneurship is a good career choice to be positively related to entrepreneurship (Bosma et al. 2018).

While most research focuses on evidence of cross-country effects generated from panel data using institutional indices, Bjørnskov and Foss (2016:301) argue that assuming homogeneous responses to institutional pressure is a shortcoming of previous literature in that it “merely identif[ies] average treatment effects that can easily hide very different effects across industries or countries.” Scholars like Busenitz et al. (2000) and Gupta et al. (2014) have assessed individual countries’ institutional profiles (CIP) for entrepreneurship, focusing more on the perception of different institutional dimensions and their effect on entrepreneurship. This article follows this direction by presenting a single-country study of the perceived institutional environment for entrepreneurship in South Korea (hereinafter referred to as Korea).

Korea is an interesting case to study entrepreneurship due to its economic development from one of the poorest countries in the 1950s to a highly industrialized member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) since 1996. This development can largely be contributed to family-led conglomerates like Samsung, Hyundai, or LG, the so-called Chaebol which has been supported and nurtured by the central government throughout Korea’s catch-up phase (Amsden 1989; Jones and SaKong 1985; Joh 2015). Only in the 1990s did the government’s focus shift to technology-oriented venture businesses (Kwon 2010:253) as a new engine for Korea’s dwindling economic growth. At the same time, the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 legitimized government support for business foundations to fight increasing unemployment (Choi and Kim 2004; Song 2007). After the burst of the dot-com bubble in the early 2000s, however, entrepreneurial activities slowed down, and public support schemes were rationalized. Only when President Park Geun-hye (2013–2017) vowed to transform Korea into “a startup nation” (Cha 2015) under her “Creative Economy” paradigm, new business foundations gained momentum once more. Consequently, the institutional environment in which this happened constitutes a matter of interest.

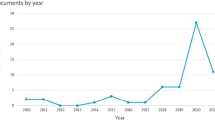

Figure 1 shows the number of newly established corporations between 2000 and 2019. Between 2000/2 and 2008/1, the average growth rate of new foundations was − 0.6%, but it was 3.6% between 2008/2 and 2017/1. For founders younger than 30 years old, the average growth rate was 7.0%, and for those in their 30 s, it was 2.3% during that period. Moreover, the number of corporations increased by 80% between 2008/1 and 2017/1. Thus, there is a visible increase of newly established corporations in the 2010s.

Source: MSS/KOSIS (2021)

Newly established corporations. Note: Biannual number of newly established corporations total (left axis), by Koreans under 30 years and between 30 and 39 years (right axis), based on registration data of the Korean National Tax Service.

This study’s goal is to examine Korea’s perceived institutional environment for entrepreneurship as an occupational choice among young Koreans and its recent changes. Considering the three different institutional dimensions (regulative, cognitive, normative), the most salient type of institution in encouraging entrepreneurship can be identified, providing a possible explanation for the increase of newly established corporations. At the same time, the findings hint at the relevance of each institutional dimension for entrepreneurship and their order of change.

The empirical findings draw on data gathered from 31 semi-structured interviews with entrepreneurs and experts on entrepreneurship in Korea. Additional secondary literature, official statistics, and government documents complement the dataset. Together, the data provide a rich source for the identification of important institutional changes and connections between the respective dimensions. In this way, this article provides a thorough analysis of the institutional environment for entrepreneurship in Korea, which, to the author’s knowledge, has not been accomplished so far.

The results indicate that entrepreneurship-friendly regulative institutions have contributed significantly to the rise in business foundations. However, cognitive and especially normative institutions are not yet fully favorable for entrepreneurship despite some initial changes. The findings suggest an institutional asymmetry between the formal and the informal institutions. Yet, in the battle of the conflicting institutional forces, it seems that regulative institutions are more powerful in encouraging entrepreneurship than cognitive and normative institutions are preventing business foundations. This puts the role of informal institutions in entrepreneurial activities into question. Their relevance for the decision to start a business seems to be negligible if regulative institutions are supportive enough. The results also indicate that informal institutions change slower than formal institutions and can hardly be changed top-down—it is up to society or even entrepreneurs themselves to change informal institutions (Elert and Henrekson 2021). This finding contributes also to the theory on institutional change (Williamson 2000). Overall, this paper provides important insights for entrepreneurship scholars concerning the institutional environment for entrepreneurship as well as policymakers from Korea and countries with a similar entrepreneurial history.

The remainder of the article is structured as follows: The “Literature review” section reviews the theoretical and empirical literature related to entrepreneurship and institutions, starting with the conceptualization of entrepreneurship in this paper. The “Methodology” section explains the methodology and data collection. Results from each institutional dimension are presented in the “Results” section. The “Conclusion” section concludes the paper.

Literature review

Conceptualization of entrepreneurship

There is little consensus among scholars on how to define entrepreneurship. Besides the theoretical fragmentation (see also Wennekers and Thurik [1999:31]) and various types of entrepreneurs (Sendra-Pons et al. 2021:2) including Knight’s (1971 [1921]) risk-taking entrepreneur, Schumpeter’s (1983 [1934]:75) innovating entrepreneur, and Kirzner’s (1974:34) alert entrepreneur, there is heterogeneity in empirical studies (Marcotte 2013). Parker (2009:6) argues that different empirical measurements reflect not only the different theoretical approaches but also the diverse scholarly interests. For instance, economists are often interested in the analysis of incentives or occupational choices, so they tend to assess entrepreneurship via business owners and the self-employed. In this context, “necessity entrepreneurs,” who are those facing “no better choices for work,” are often distinguished from “opportunity entrepreneurs,” i.e., those who pursue “a business opportunity for personal interest” (Reynolds et al. 2001:8). Business and entrepreneurship scholars assess entrepreneurship in the light of behavior, cognition, and perception (Parker 2009:6), more frequently taking the Schumpeterian or Kirznerian perspective. Yet, despite the importance of innovations, Schumpeter’s theory is “abstract and not easily operational at the empirical level” (Henrekson and Sanandaji 2020:735). For instance, the concept is transitional, meaning every Schumpeterian entrepreneur sooner or later becomes an owner-manager unless he keeps innovating (Schumpeter 1983 [1934]:78). New firm formation rather than self-employment or small business ownership might be the best empirical proxy available (Nyström 2008:271). Henrekson and Sanandaji (2020:737) also find evidence that newly registered corporations are closest to the Schumpeterian type of entrepreneur, as their legal status reflects higher quality and growth potential.

The study at hand focuses on the institutions that encourage or prevent the type of entrepreneurship that spurs economic growth and job creation. In Korea, self-employment is often characterized as “poor entrepreneurship” with low profits and productivity (Yun 2013:58 f.), so it disqualifies as a measure for entrepreneurship in this study. While also imperfect, the quantitative measure of newly established corporations is the best proxy available because it has a qualitative dimension through its legal status without being too narrowly defined. Additionally, it allows entrepreneurship to be regarded as an occupational choice in the pursuit of an opportunity. It captures the dynamic component of entrepreneurship (Wennekers and Thurik 1999:33) in that it only counts the newly created and not the already existing corporations. Finally, while institutions “shape entrepreneurial behavior along the entire entrepreneurial process” (Valdez and Richardson 2013:1150), the decision to establish a new business is commonly used for assessing the connection between institutions and entrepreneurship.

Institutions and entrepreneurship

Institutions have been ignored within economics due to their complexity (North 1990:16, Williamson 2000:595, Ménard 2018:6) until the statement by North (1990:12) saying that “institutions matter” for economic performance became widely accepted. North (1994:360) defines institutions as “the humanly devised constraints that structure human interaction,” which are “made up of formal constraints (e.g., rules, laws, constitutions), informal constraints (e.g., norms of behavior, conventions, self-imposed codes of conduct), and their enforcement characteristics.” Accordingly, formal and informal institutions form the incentive structure for individual behavior and economic decisions, thereby indirectly influencing the economic outcome. This leads to the common theoretical proposition that institutions can spur or hamper entrepreneurial activities as a form of economic behavior “by providing an appropriate environment or by imposing barriers” (Urbano et al. 2019:24). Most analyses on how institutions affect entrepreneurship are based on North’s institutional theory (Urbano et al. 2019:26).

Although there is a debate about whether or not to address both formal and informal institutions (Bruton et al. 2010), Valdez and Richardson (2013:1150) emphasize that empirical studies concerned with macro-level entrepreneurship should examine a combination of different institutional elements because it not only allows assessing the effect of the institutional environment as a whole but also identifying the most salient institutional variables. The three institutional dimensions proposed by Scott (2014), i.e., regulative, (cultural-)cognitive, and normative institutions, provide a structured approach including both the formal and informal institutions that shape entrepreneurial activities in theory.

The regulative pillar is equivalent to formal institutions (Scott 2014). In the realm of entrepreneurship, regulative institutions comprise, for instance, tax and bankruptcy laws, industry and labor market regulations, government policies, public support schemes, fiscal incentives, and the venture capital market (Valdez and Richardson 2013:1157, Wennekers et al. 2002:41 f.).

Cognitive institutions represent the glasses through which all members of society see reality. In the entrepreneurship literature, there are two streams capturing the cognitive dimension (Valdez and Richardson 2013:1155 f.). The first one is the personality or trait approach which has been criticized for being fruitless (Gartner 1988; Davidsson 2003). The second one assesses cognitive differences at the national level based on the belief that aggregate behavior is influenced by “cognitions that are generally shared in a society” (Valdez and Richardson 2013:1155). However, there is no empirical consensus with regard to this issue. For instance, Thomas and Mueller (2000) test whether the traits innovativeness, risk propensity, internal locus of control, and energy level vary across cultures. Mitchell et al. (2000) investigate whether individual cognitions (“venturing scripts”) are decisive for starting a business and test whether these vary by country due to cultural differences. Busenitz et al. (2000:995) refer to the cognitive pillar as the shared social knowledge about entrepreneurship and prevalent skills necessary to create and run a new business. Based on this reasoning, Simón-Moya et al. (2014) and Pinho (2017) use indicators for education as proxies for the cognitive institutional dimension.

The normative pillar includes “norms of behavior, conventions, [and] self-imposed codes of conduct” (North 1994:360) as well as values which are “conceptions of the preferred or the desirable together with the construction of standards to which existing structures of behaviors can be compared and assessed” (Scott 2014:64). Norms guide people on how to do things (Valdez and Richardson 2013:1157). They arise through social interaction between humans and are maintained by means of social sanctions like shame or disrespect (Dequech 2009:72). However, whenever the rewards for disobedience outweigh the costs of social sanctions and the benefits of compliance, individuals are likely to deviate from social norms (Dequech 2009:74). In the realm of entrepreneurship, normative institutions address, for instance, the degree to which people admire and respect entrepreneurs and entrepreneurship as a career path as well as how society values creative and innovative thinking (Busenitz et al. 2000:995).

Ideally, the three institutional dimensions for entrepreneurship are complementary; however, institutions constantly change. Some argue that because formal institutions are deliberately designed and imposed centrally (Kingston and Caballero 2009:153), they can be altered quickly and overrule inert informal institutions. In contrast, Roland (2009:117) claims that informal institutions change incrementally until formal institutions are under pressure to follow suit. A compromise is to see the different perspectives on institutional change not as substitutes but as complements (Ruttan 2006:252).

Nevertheless, differences in the speed of adjustment can create asymmetries in the institutional system in the short run (North 1990:87 f.). Empirical studies in transition economies have found evidence for supportive and unsupportive institutions existing at the same time, which might undermine entrepreneurial potential (Tonoyan et al. 2010; Puffer et al. 2010; Manolova and Yan 2002; Williams and Vorley 2015).

Many scholars have examined the connection between institutions and entrepreneurial activities empirically with various models as well as sets of data, and some have also tested the link to economic growth. However, results are mixed, also due to differences in conceptualization and measurements of entrepreneurship and institutions (see Table 3 in the appendix for an overview of cross-country studies). Aparicio et al. (2016) find that regulative institutions like private coverage to obtain credit have a positive influence on entrepreneurial activity, whereas the number of procedures to start a business has a negative influence. Similarly, Urbano et al. (2020) state that the number of procedures for starting a new business and private credit coverage significantly explain the entrepreneurial activity. Fuentelsaz et al. (2015) declare that better property rights, more business and labor freedom, as well as better financial and educational capital have a positive influence on entrepreneurial activity, but more fiscal freedom exerts a negative influence. McMullen et al. (2008) find a similar result for property rights and labor freedom.

Valdez and Richardson (2013) note that cognitive institutions in the form of perceived knowledge, skill, experience required to start a new business, and fear of failure as well as normative institutions, measured via a cultural support index, have a positive influence on entrepreneurial activity. Bosma et al. (2018) also mention factors exerting such a positive influence, which are regulative institutions in the form of a smaller size of government and normative institutions in the form of the belief that entrepreneurship is a good career choice. However, Stenholm et al. (2013) declare that only regulatory interventions in the form of business freedom and ease of new business formation positively influence the rate of entrepreneurial activity. They find no significant impact of the cognitive and normative institutional dimensions. Khalilov and Yi (2021) also consider regulative institutions (economic freedom) to drive entrepreneurial activities but not normative institutions (entrepreneurial value). Thus, while there seems to be some agreement with regard to the role of regulative and cognitive institutions, there is ambiguity concerning the role of the normative institutional dimension.

Most of these quantitative cross-country studies directly draw the connection between institutions, startup rates, and economic growth. They also provide a high degree of generalizability. However, they are less helpful for evaluating the perceived institutional environment in a specific context or country, especially when assuming response heterogeneity to institutional pressure that is often neglected (Bjørnskov and Foss 2016). This can be the case, for instance, in emerging or developing economies but even in highly industrialized economies with distinct economic systems like Korea or Japan.

There are some quantitative studies evaluating the institutional environment of single countries. For instance, in his comparative study, Sahiti (2021) notes that although the regulatory environment for starting a business is rather positive, there are obstacles with access to finance, entrepreneurship education, and the overall political stability in Kosovo. Closely based on Scott’s three institutional dimensions, Busenitz et al. (2000) developed the country institutional profile (CIP) survey to measure the perception of the institutional environment for entrepreneurship in single countries. For instance, Gupta et al. (2012) and Gupta et al. (2014) conducted the CIP in Korea in 2009 and found that it ranked low in the regulative, the cognitive, and especially the normative institutional dimensions in comparison to other rapidly emerging major economies like China and India as well as other developing economies like the United Arab Emirates. Yet, Manolova et al. (2008:213), who measured the CIP in Bulgaria, Hungary, and Latvia, arrive at the conclusion that “aggregate measures of the institutional environment for entrepreneurship may mask subtle and persistent differences, especially in the role of deeply embedded and less readily observable influences such as legal and cultural traditions, or social norms and values.”

There are only few qualitative studies about the institutional arrangement for entrepreneurship, although Williams and Vorley (2015:846) suggest that it could provide deeper insights through the perceptions and experiences of entrepreneurs and experts. These views would be important for a better understanding of the institutional environment and the generation of future research questions and hypotheses. Williams and Vorley (2015), who examine how the institutional environment has shaped entrepreneurial activity in Bulgaria, focus on the effect of institutional asymmetries that undermine entrepreneurial activities. In a similar qualitative manner, Puffer et al. (2010) explore how the void of formal institutions in Russia and China affects the relationship between entrepreneurship and institutions. Following the route of Williams and Vorley (2015), the goal of this research is to find indicators for the rise in new business creations by carefully assessing Korea’s perceived institutional environment.

Recent literature on entrepreneurship in Korea

While the literature on Chaebol entrepreneurship is plentiful, research about the recent increase in entrepreneurial activities in Korea is still rare. In 2019, Robyn Klingler-Vidra and Ramon Pacheco Pardo published three articles about the phenomenon. One takes on a developmental state perspective and argues that the government’s Creative Economy Action Plan of President Park Geun-hye had a strong effect on the volume of participants in the entrepreneurial ecosystem by increasing awareness and making entrepreneurship a good career option as well as by providing more and better access to financing (Pacheco Pardo and Klingler-Vidra 2019:324). The qualitative study of Hemmert et al. (2019) explores the entrepreneurial ecosystem (EE) of Seoul according to the domains policy, culture, human capital, finance, markets, and supports. They find that Seoul’s EE is driven by national-level policy programs with a focus on financial support and that it used to lack a conducive culture for entrepreneurship due to uncertainty avoidance and fear of failure. While these studies provide interesting insights, they are not based on institutional theory. To the knowledge of the author, there is no qualitative study of the Korean institutional environment for entrepreneurship yet that explains the recent increase in entrepreneurial activities, measured as newly established corporations. Consequently, the study at hand attempts to fill this gap.

Methodology

Qualitative semi-structured interviews can reveal perceptions about institutional changes from experts on entrepreneurship and about individual experiences by entrepreneurs themselves. The qualitative approach provides a more accurate picture of the perceived institutional environment, and policymakers can profit from a better understanding of how to encourage entrepreneurship via institutional change (McMullen et al. 2008:891). After all, the perception of context is what entrepreneurs react to (Gómez-Haro et al. 2011:1680). Therefore, semi-structured interviews with 14 experts from diverse public and private organizations and 17 Koreans who already (co-)founded and were planning to find (so-called nascent founders) or give up on founding an enterprise were conducted. Questions were based on and derived from the three institutional dimensions explained in the “Literature review” section.

The interviews were conducted between October 2016 and March 2017 in Seoul, Daejeon, and Gyeonggi Province (see Tables 4 and 5 in the appendix for details on interviewees). These locations were targeted because Seoul metropolitan area is the economic center of Korea (Lee 2009:357 f.) and Daejeon is Korea’s national R&D hub (Oh and Yeom 2012).

The sampling method for the recruitment of interviewees was purposive and snowball sampling.Footnote 1 Entrepreneurs were mostly approached at startup events or via the researcher’s private network. In the selection process, the researcher focused on young founders in their 20 s and 30 s, and in terms of legal form on “Representative Directors” (CEOs) and “Joint Stock Companies” to avoid necessity entrepreneurship. The founders’ gender and educational background as well as industry and level of innovativeness of the business idea were of secondary importance. Questions for entrepreneurs were more comprehensive on the normative aspects.

Many experts were recruited similarly to entrepreneurs, but some were contacted via email after online-based research for accelerators, incubators, etc. Depending on the expert, the questionnaire focused more on specific aspects. For instance, venture capital experts received more questions on financing issues.

Especially early interviews were conducted in English whenever the interviewees agreed. As the researcher’s Korean language skills improved during field research, some interviews could be conducted in Korean. In those cases, a Korean version of the questionnaire was used, which was translated by a bilingual research assistant.

Data saturation occurred at around 30 interviews. Interview recordings were first transcribed by the researcher (interviews in Korean were transcribed by an instructed Korean native speaker). Then, the data were analyzed according to the guidelines suggested by Taylor-Power and Renner (2003). Coding started with the three broad themes, i.e., the regulative, cognitive, and normative institutional dimensions. Interview questions were already framed around these three themes and subthemes which were derived from the literature. However, some questions were openly formulated to allow interviewees to raise new topics and issues. Eventually, three to four subthemes emerged from each theme during the coding process, and for most subthemes, further categories emerged from the answers. These build the structure of the “Results” section. To find possible connections as well as cause and effect relationships between subthemes (Taylor-Power and Renner 2003:5, Saldaña 2009:187), the MAXQDA Code Relations Browser was used to show the closeness and overlap between main themes and all subthemes. In addition to quotes by experts (EP1–EP14) and entrepreneurs (E1–E17) integrated into the text (in italics), Tables 6 , 7 and 8 in the appendix present additional selected interview material.

Since interviewees could not elaborate in detail on some crucial issues, the researcher filled these gaps with secondary data from the literature, statistics, and official documents.

Results

The cognitive institutional pillar

Korea’s public and private sector education system

In international comparison, education levels in Korea stand out. According to the World Bank Education Statistics, Korea had a relatively high net enrolment rate in secondary education (98.01%) and an exceptionally high gross enrolment rate in tertiary education (94.35%) in 2017.Footnote 2 Pursuant to OECD data, 70% of young adults (25–34 years old) held a tertiary education degree in 2018, which constitutes the highest proportion among OECD countries (OECD 2019:50).Footnote 3 Korea is also known for its excessive private tutoring system with private educational institutes (hagwŏn). As per the Kostat (2017) Private Education Expenditures Survey, total private sector expenditures for education rose from 18.1 trillion KRW (15.56 billion USD) in 2016 to 18.6 trillion KRW (16 billion USD) in 2017, while the participation rate increased from 67.8 to 70.5%.Footnote 4 The main reasons for participating in private sector education were to compensate for classes in the public education system (47.4%) and to prepare for higher school levels in the case of high school students (31.2%).

Shin (2012) argues that the high level of tertiary education stems from a combination of imported foreign ideas of universities, high value of education based on Confucianism, and, most importantly, the rapid economic development of Korea since the 1960s. The incremental expansion of education from elementary to graduate level during Korea’s rapid industrialization process explains the high demand for private sector education (Shin 2012:61). Additionally, the government education policy produced bottlenecks at upper education levels that shifted higher with time, up to the national standardized exam for college and university admission (Kim 2002). Therefore, the ultimate purpose of the public and private education system is to prepare students for the competitive Korean College Scholastic Ability Test (KCSAT) that filters the elite from the population at large (Byun et al. 2012:223).Footnote 5 Since the KCSAT is a standardized multiple-choice test, a homogenous style of teaching by rote and memorizing is widespread.

Reforms of the education system to “eliminate socially undesirable practices associated with school education” (Kim 2002:36) were already implemented under President Kim Young Sam (1993–1998) in 1995 through the 5.31 Education Reform Proposal and the integration of ICT into the education system (Kim 2002:36–38). Moreover, to ease the competitiveness of the KCSAT, adjustments of admission standards to higher education were attempted in 2008 (Jones 2011:40), but they did not entail substantial changes.

The immense importance of the KCSAT for students’ academic future and career paths is regarded as preventing entrepreneurship, as the “traditional Korean education system has nothing to do with entrepreneurship [and] especially high-school education is mainly for passing the entrance examination for the university” (EP3). The Korean education system is perceived as a severe cognitive hindrance for entrepreneurship, hampering students’ ability to think “outside the box.” Entrepreneur E1 remarks that young Koreans “are used to just getting instructions in classes throughout the whole years of schooling. And they are not really used to questioning or ‘going out of the box.’” Experts stress the importance of education but see a lack of creative and innovative thinking:

I believe that the education really matters in this type of [entrepreneurial] process because as a student, you are not asked to create or think of something from scratch, but rather you learn what’s given. And the exam that you do is multiple choice, so you are good at choosing, but you are not good at making something new. But startup is such a creative business. Sometimes, you need to think something from scratch if you really want to disrupt current businesses. But I think we are not trained to be entrepreneurs yet. (EP13)

The Korean education system has also been criticized for not teaching students problem-solving abilities or the ability to manage risks and mistakes, which the interviewees regard as essential for entrepreneurial action:

Education is the problem. [Students] only focus on the KCSAT exam before graduation, [and] even after entering the university, students don’t acquire problem solving ability. (EP11)

The Korean educational system […] is very efficient in terms of selecting, […] screening people. […] And this system makes people more efficient to take the exam. Not the real, you know, creativity or thought. So Korean private or public education always focuses on the textbook problems. How efficient (sic) we solve the test or how fast. And in other words, the people are afraid of answering the wrong question. […] But in real life […] you have to start again if you fail, but if someone is really afraid of failure and the education systems makes people afraid of making mistakes [...] [being] an entrepreneur is something about making mistakes over and over again until you finally find a solution. (EP2)

In 2018, compulsory coding education was integrated into the official curriculum to accommodate the technology- and innovation-driven economy as well as to enhance logical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving ability (Paek 2018). However, experts like EP6 and EP13 remain skeptical whether students would apply coding as a tool for the creation of an innovative business. Even more detrimental, the introduction of coding as a part of the curriculum already opened a new market for coding hagwŏn, intensifying competition and inequality among students (U 2018). Thus, compulsory coding education might result in students cramming to collect another “spec” for their CV without improving actual productivity,Footnote 6 let alone the ability to apply it when starting a business.

Overall, the Korean education system is perceived as unfavorable for entrepreneurship, as it fails to transmit the necessary knowledge, skills, and abilities for starting a business.

The emergence of entrepreneurship education

There have been efforts to provide entrepreneurship education in Korea. For instance, the Youth BizCool program for elementary, middle, and high school students, which is run by the Ministry of SMEs and Startups (MSS) every year since 2002 (Platum 2014), is mentioned by experts (EP1, EP12). Through this program, students can learn about entrepreneurship, participate in student startup clubs, and listen to experts’ special lectures. The program aims at cultivating an entrepreneurial spirit among students and spreading the knowledge necessary for starting a business. Teachers in charge also receive training and teaching material. The program has been expanded in recent years: While in 2013, only 135 schools took part nationwide, the number rose to more than 500 schools in 2017. The budget for the program in 2018 was around 7.6 billion KRW (6.54 million USD) (MSS 2018).

Moreover, some private sector organizations recognized the shortcomings of the Korean education system and started providing their own educational content. For instance, the Asan Nanum Foundation provides educational programs for students, teachers, parents, and the general public.Footnote 7 A representative explains the motivation:

Because if you want to foster entrepreneurship among the students, I think the most important part is educating them about problem-solving ability and creative-thinking ability. But Korean education contents are usually for memorization. Not really suitable. So that’s why our foundation is trying […] we are actually making our own educational content. (EP7)

Thus, there is a bottom-up movement for entrepreneurial education at the school level.

At the tertiary education level, entrepreneurship education has increased in recent years. Already in 2013, the Ministry of Education (MOE) planned to contribute 262 billion KRW (225.32 million USD) to adjust curricula and support innovative models for education (OECD 2014:146). Accordingly, universities were required to use 30% of the funds they received from the MOE for the promotion of startups, jobs, and connections between industry and university, including the development of entrepreneurship education.

Universities like the Yonsei University in Seoul and the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST) in Daejeon have established entrepreneurship education for their students including practical training and first-hand experience programs. For instance, in 2014, the “Startup KAIST” movement began to revive entrepreneurship at KAIST and nationwide.Footnote 8 “K-School” was founded in 2016 upon the initiative of KAIST members, and the Ministry of Science, ICT, and Future Planning (MSIP) supported the idea to establish a graduate program by providing significant funds. Hence, KAIST established a cross-departmental master’s degree in entrepreneurship and innovation, a minor degree in science-based entrepreneurship, as well as a certificate program open to all KAIST students. Interviewee E16, who took part in the entrepreneurship lectures, reports that the program helped him to see the world through an entrepreneur’s eyes, which is something he would not have learned in conventional engineering classes:

The 3-day lean startup program was also very useful […] because it felt more like a training, not teaching, not learning, but a little different, it wasn’t lecture-based, it was more experience-based. We really learned a lot about presentation and presenting our ideas. (E16)

Although entrepreneurship education at the university level is still not pervasive yet, the initiatives can be regarded as initial changes of the cognitive institutional pillar.

The normative institutional pillar

Desirable career paths in Korea

Many interviewees mention two desirable career paths in Korea: regular employment in large enterprises and in the public sector including professions such as a medical doctor, lawyer, and teacher.

So far, the common types of jobs in Korea are either you go for the big company, or you go for the government. Or if you’re retired, especially after the financial crisis, they are forced to retire. And they have to do their own job which is now called self-employed. (EP 2)

Both jobs in large firms and the public sector are perceived as “good jobs” (Lee and Choi 2006:210), and the following explains why becoming an entrepreneur is not. The main reason for preferring employment in a large enterprise is the financial incentive: “If I’m in Korea, I should go for the large cooperation. First of all, for most Koreans, the reason why they choose the big companies is because they get more money and it’s more comfortable or convenient.” (E16).

Regular employment in a large conglomerate guarantees a relatively high income compared to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs).Footnote 9 Figure 2 shows that entrance level average annual salaries in large, public, and foreign enterprises are always higher than salaries in SMEs. Annual salaries in SMEs have also been stagnant between 2014 and 2017. These wage gaps are firstly caused by the distorted business structure in Korea with low productivity of SMEs compared to large enterprises (Ahn 2018: 4 f.) and secondly by the increasing labor market duality that intensified because of the labor market deregulation after the Asian Financial Crisis (AFC) in 1997, subsequent labor policy failures and changes in Korea’s industrial structure (Yun 2009). Therefore, regular workers in SMEs receive lower wages and fewer social benefits than regular workers in large firms, while temporary workers in SMEs are even worse off (Schauer 2018:14).

Source: Kim (2015), Yun (2017), based on data from www.jobkorea.co.kr

Annual average entry-level salary by company Type, 2014–2017. Note: Salary of entry-level positions for graduates from 4-year university programs. Unit: 10,000 KRW. Large = large enterprise; Public = public enterprise; Foreign = foreign enterprise. In 2014, 146 large, 20 public, 41 foreign, and 197 SMEs (404 in total) were surveyed by the job portal Jobkorea. In 2015, the sample size was 182, 29, 30, and 162 (403 in total), respectively, and in 2017, it was 207, 12, 13, and 290 (522 in total), respectively. Information on the sample size of 2016 was not available. Figures including bonus and excluding incentives.

Employment at large enterprises is desirable but competitive. According to Statistics Korea (2021) Business Demography Statistics from 2016 until 2019, 99.9% of Korean firms are SMEs and employ around 82% of the workforce. Moreover, while SMEs suffer labor shortages, the top 500 largest enterprises planned to hire fewer employees in 2016 compared to 2015 due to sluggish economic conditions and company internal issues (FKI 2016). These dire prospects have been fueling youth unemployment and youth labor market inactivity, as young Koreans are reluctant to work for SMEs and postpone graduation until they find a decent job (Yun 2010).

Wages of government officials are comparably modest, and they are determined by rank and salary level (Lee and Choi 2006:202). For example, according to the civil service payroll of 2017 by the Ministry of Personnel Management, a ninth-rank general government official earns between 1,395,800 KRW (1,200.4 USD) (salary level 1) and 3,017,500 (2,595.05 USD) (salary level 31) per month.Footnote 10 Nevertheless, public sector jobs are still desirable due to high job security. Interviewee E16 continues:

It’s really funny, but in Korea, if you have a safe job, if you get steady money, then it’s a good job in Korea. Like another good job is, [a] public job, is teacher, because it’s also paid by the government. (E16).

Other advantages of public sector jobs are a higher retirement age in contrast to early retirement schemes in the private sector, moderate working hours, and less competition for promotion. Public sector jobs are especially advantageous for women, as they can stay employed after marriage and childbirth (Pak 2016).

However, it is especially Korea’s elderly, and not their children, who prefer the desirable jobs. This is due to Korea’s history of economic development and the AFC. Entrepreneurs believe that their parents’ occupational preferences were shaped by the catch-up phase of economic development. Since Korea used to be a developing country, a stable income, and job security were considered as the route to economic success because it provided the necessary financial resources to support one’s family:

We’ve been in poverty, […] but the main way to get out of that was to put your head down, study, learn, […] make money, don’t starve. Job security. Not lottery. Job security for your family. That’s what success looked like. One generation above. And even these days that’s what success looks like to a lot of people. (E5)

Indeed, there was a shortage of college graduates starting their own business and an oversupply of salaried managers and engineers, who received a sizable remuneration in the 1960s and 1970s (Amsden 1989:221, 229). Instead of new firm formation, the expansion of existing firms was the driver of Korea’s rapid industrialization (Jones and SaKong 1985:170).

An equally important explanation is the shared experience of the economic shock of 1997. Life-time employment, once a substitute for an underdeveloped welfare state and a sign of corporate paternalism preserving social stability (Kim and Finch 2002:122), ended with the failure of the Chaebol. The following labor market flexibilization was regarded as a violation of Confucian values in Korea (Kim and Finch 2002:134), as mass layoffs and non-regular employment became omnipresent. Entrepreneurs report how their own families were affected by the economic hardship and how it shaped their parents’ wishes for their children’s economic safety.

And that’s because we have experienced [the] IMF [crisis]. We saw a lot of people […] losing their job, [going] bankrupt, not just bankrupt, they just owed a lot of money and committed suicide. And my family also had a really difficult situation, financial difficulties, back in 1998, when I was at second grade in middle school. We had a really tough time. So I understand when my mom is worried about my future when I tell her I just want to start my own startup. I understand. Because she experienced that. (E2)

We had the IMF and, in that era, lots of parents turned their children into ‘chickens.’ They are so scared about losing their job. […] Our generation was the biggest generation that was pushed to get a safe job. (E10)

These stories indicate that the shared experience of poverty and economic shock of Korea’s older generation affects the occupational choices of the young generation to minimize socio-economic risks. Taking financial risks by founding one’s own business leads to parental concerns (E8) or even serious conflicts (E15).

The societal ranking system and occupational choices

The desirable career paths are also associated with a high social status resulting from their competitiveness and exclusiveness. This draws back onto a deep-rooted ranking mindset pervasive in Korea. “Education enthusiasm” (Shin 2012:66) as a characteristic of Confucian tradition and the exam-based filtering system as a social heritage have served to select high ability people for positions in public office since the kwagŏ civil service examination system in the early koryŏ Dynasty (918–1392) (Jung 2014:51). Throughout Korea’s rapid industrialization, the civil service exam-based recruitment system became even more meritocratic, as the bureaucracy was essential for state-led development (Lee and Lee 2014:52, Ko and Jun 2015:197). More importantly, however, exam-based filtering systems have “functioned as a way to improve social status” (Shin 2012:66), i.e., climbing the social ladder and enjoying social prestige through passing competitive exams (Lee and Lee 2014:54). The KCSAT in particular creates a nationwide performance ranking among all test takers, which influences all areas of life including one’s place of residence.Footnote 11

The perception of gaining social prestige by passing competitive exams persists until today as remarked by, for instance, entrepreneur E10 and expert EP5:

There is a word like ipsinyangmyŏng [i.e., rising in the world and gaining fame (author’s note)]. […] This is about […] getting success and going into the government. Means success before Chosŏn dynasty [1392 – 1910 (author’s note)], that concept of success still remains, I think. So, they want to go to the government and [become] a lawyer. Of course, it’s just prestigious and well paid. (E10)

So they [i.e., Korean parents (author’s note)] realized that in order to get into those good schools and Samsung, the score really matters. So that’s why they are pushing them [i.e., their children (author’s note)] to get a good score and entering the good elite school, and after that, just go to the well-known company like the Samsung or become a high-ranked official in the government. And most people strongly believe that that’s the way to having a great life. (EP5)

Thus, Korean society is highly aware of the connections between the education system, the exam-based filtering system, as well as social status, and the societal pressure to conform to these institutional elements is high.

The occupation “entrepreneur” is not compatible with the societal ranking system. Expert EP5 continues: “So becoming an entrepreneur, joining a startup is actually not following that kind of elite path.” On the contrary, starting one’s own business is often interpreted as a sign of underachievement. Eventually, lacking alternatives pushes people to start their own business as already noted by EP2 in the “Desirable career paths in Korea” section.

However, with the current startup trend, expert EP2 and entrepreneur E4 find that the reality of entrepreneurship is increasingly perceived as more nuanced:

But now the young people and young generation realize entrepreneurs are very different from those self-employed moms and pops. It’s more like a structured and more advanced type of doing your own business, which means you have to leverage technology and the money, I mean capital. And also, they are very professional people, right? (EP2)

Korean society? Well… they are still arguing about it. Some people say startups are good, and some say startups are just second or third option when people fail to get a job in big companies. (E4)

Hence, a slight change of perception was observed during the field research.

Social stigma against business failure

Business failure is another issue that stood out during interviews because Korean entrepreneurs usually rely on debt financing, which underlies the so-called joint guarantee system (see more in the “The regulative institutional pillar” section). It means that despite the corporation’s legal identity as the principal borrower, entrepreneurs are the guarantor for their incorporated business and are liable in the case of insolvency.Footnote 12 In addition, a co-guarantor, often a family member or a friend, is a prerequisite for a bank loan (OECD 2014:143). If a corporation defaults, both guarantor and co-guarantor are held liable to settle obligations. This joint guarantee system creates a social stigma against business failure according to interviewees:

But how to face and how to leverage the failure experience is critical, but in Korea, we have the fear of failure, we can see this issue from two perspectives. First one is financial, and second one is social. […] Social stigma, I also think this is related to the financial breakdown. You go down in your life, so people say ‘See, he is financially broke, he’s not gonna do things, he’s just such a failure.’ He gets a stigma of failure. (EP13)

If a company is insolvent, the owner loses everything. Not just financially but also socially, there is a bad connotation […]. That person is then regarded as a failed human being. (EP14)

The risk of business failure therefore has two dimensions, a financial and a social dimension, which together creates a social stigma against business failure.

Overall, entrepreneurship in Korea is not perceived as a desirable occupation due to its financial uncertainty, a low social status, and a social stigma against business failure.

The regulative institutional pillar

The joint guarantee system

To understand the social stigma against business failure, it is essential to comprehend the joint guarantee system. Throughout Korea’s economic development, its financial system has relied on the banking sector to provide financing for development projects rather than the securities market (Jin et al. 2004, cited in Kwon 2010:252). As credit score-based lending practices were underdeveloped, businesses could secure their loans via collateral. However, loans without collateral were restricted through the amendments in the Banking Act from 1962 and 1969 (Cha and Kim 2010:193). The credit guarantee system was established in 1961, and in 1976, the Korea Credit Guarantee Fund (KODIT) was implemented, followed by the Korea Technology Finance Cooperation (KOTEC) in 1989. Their purpose was to provide preferential credit guarantees to businesses without security solvency.

Nowadays, KODIT provides a guarantee service for promising startups, export businesses, and green growth businesses. KOTEC supplies technology guarantees for startups younger than five years old, for venture and innovative businesses, and other businesses with excellent technology according to KOTEC’s technology appraisal system. KOTEC and KODIT step in as a guarantor and issue a letter of guarantee to the potential creditor. If the business defaults, KOTEC or KODIT pay back the loan to the creditor, and the guarantor is indebted to KOTEC or KODIT. However, guarantees for credits are issued without the requirement of material collateral. Therefore, the joint guarantee system, determined by Art. 437 of the Korean Civil Act and Art. 57 of the Commercial Act,Footnote 13Footnote 14 prevents moral hazard arising from information asymmetry.

And the traditional way of Korean startups financing their business is through joint guarantee. To finance your company, when you borrow money, the borrower should be the company, not you. But because you are related to the company’s destiny, if the company collapses, the duty of repaying is automatically transferred to the CEO. So, you become liable for that. It’s a unique institution, unique system in Korea. (EP13)

The problem of the joint guarantee system as a major obstacle for Koreans to start their own business has been addressed by the Korean government as mentioned by, for example, EP11 and E11:

Every bank has been practicing this [joint guarantee system], personal liability for the founder, they have to succeed, otherwise, they will get in trouble. But even a good entrepreneur can fail. The government pushed to not use the joint guarantee system anymore. (EP11)

As far as I know, in the past one or two years, even if you don’t have money, the opportunities to start a business increased and there are now many companies that invest in early stage. Therefore, those things [i.e., hardship through business failure caused by the joint guarantee system (author’s note)] have become less. The case of joint guarantee system that I mentioned before, it has changed recently, like one or two years ago. (E11)

Over time, both KODIT and KOTEC adjusted the joint guarantee system as it was regarded to be a major obstacle for business foundations. Table 9 in the appendix lists the major reform steps of the joint guarantee system between 2005 and 2016. Until 2010, the reforms eased the joint guarantee requirements for venture businesses and businesses in strategic industries, but in 2011, the scope of exemptions from the joint guarantee system expanded to startups. From 2012 onwards, distinctions were made between individual and corporate businesses. These steps de facto abolished the joint guarantee system for individual businesses and reduced the joint liability for corporations significantly. From 2014 onwards, more focus was put on the exemption of businesses including startups with excellent technology to encourage new business foundations and mitigate the fear of failure.

Eventually, the Financial Service Commission (FSC), a government regulatory authority, announced the complete abolishment of the joint guarantee system for startups younger than five years with a plan to increase the exemptions for startups from 1,400 to up to 40,000 cases (FSC 2015). This reform was implemented in January 2016 and led to an increase of new guarantees issued by KOTEC exempted from the joint guarantee from 332.2 billion KRW (285.7 million USD) in 2015 to 962.5 billion KRW (827.7 million USD) in 2017 (+ 289.7%) and 3,773 beneficiary companies in 2017 compared to 521 in 2015 (+ 724.2%) (KOTEC 2017:40). In the case of KODIT guarantees, the exemptions among startups increased from 319 in 2015 to 4,112 in 2017 and from 25 billion KRW (21.5 million USD) in 2015 to 988.3 billion KRW (849.9 million USD) in 2017 (KODIT 2017:26).

With the continuing loosening of the joint guarantee system, the fundamental property of KOTEC, which mainly consists of contributions from the government and financial companies,Footnote 15 decreased almost continuously from 28.2 trillion KRW (24.2 billion USD) in 2011 to 19.7 trillion KRW (16.9 billion USD) in 2017. This means that the risks of default have been shifted from entrepreneurs to taxpayers, as government contributions are understood as public goods sourced from the fiscal budget.

Although the joint guarantee system still exists, the related risks of business failure resulting for entrepreneurs have been reduced, which helps explain the recent emergence of young entrepreneurs.

Administrative and industry-specific regulations

When asked about the administrative procedures of setting up a corporation, entrepreneurs did not report any difficulties:

I think founding your own company or a company is very easy, with the regulations […]. We just went to an attorney and asked that attorney to set it up, set the corporation, like Ltd., up. And then he did it, and then we started. We started researching and developing the machine. That’s all. (E1)

This can be attributed to the fact that first, the minimum amount of capital required to establish a stock corporation in Korea is 0 KRW since amendments of the Commercial Act in 2009.Second, according to the 2018 World Bank “Doing Business” report, the procedures to register a company in Korea consist of two steps, namely (1) making a company seal and (2) registering the company with Start-Biz and paying incorporation fees, which takes four days in total and can be done online (WBG 2018). Therefore, in international comparison, Korea ranks ninth in the “Starting a Business” category.

As is the case in other countries, there are industry—and product-specific regulations, for instance—in the pharmaceutical, the medical, and the financial industry, to guarantee product and customer safety standards. Expert EP6 explains:

You know, in China, they adapt the negative regulations. Korea is still a positive regulation system. You know that Uber is illegal in Korea. AirBnB business model is illegal in Korea, because of the regulations. I’m not saying that we have to adapt to everything, but how can we have such innovative companies in Korea […] imagine that they would have started from Korea, they are already illegal. […] So many innovative businesses are illegal in Korea, why? It’s because the regulations cannot keep up with the innovations, that’s it. (EP6)

However, the government under President Moon has recently pushed forward so-called regulatory sandboxes to ease the actualization of innovations in leading industries (Kim and Choi 2019:19–21).

The government’s role in promoting entrepreneurship

Throughout Korea’s economic development, the government has played a central role in promoting selected industries and businesses. However, the belief that technology-driven startups are more flexible, creative, and innovative than conglomerates in old industries became prevalent, especially under President Park Geun-hye (2013–2017). Moreover, startups were also considered as a solution for the increasing youth unemployment (Kim 2014:2). Therefore, President Park’s Creative Economy heavily supported young entrepreneurs. In June 2013, the Action Plan for the Creative Economy was announced including strategies for the “creation of the ecosystem in which creativity is rewarded fairly and it is easy to start a new company” and to “strengthen the competitiveness of the venture and small [and] medium sized company as a key player” (Cha 2015:38). Many interviewees report about the effect of the Creative Economy:

It’s been crazy […]. Ever since the Creative Economy initiative, a lot of the Korean startups you see around you right now, at this hour, you owe it […] to the government initiative. [...] So the Korean entrepreneurship scene is really growing (sic) in the past two to three years because of the government’s role. (E5)

This startup boom is kind of created, artificially created by this current government, because this government started about less than five years ago, and it’s one of their major agenda (sic) to boost startup activities. I think that’s good. They picked the right topic, and growing new startups is very important, very necessary for the Korean economy. (EP3)

This increasing focus on startups found financial expression in the growing budget of the Small and Medium Business Administration (SMBA) and the MSIP (Fig. 3). The budget for the SMBA increased from 6.15 trillion KRW (5.29 billion USD) in 2012 to 8.19 trillion KRW (7.04 billion USD) in 2017. The MSIP’s budget also increased from 13.65 trillion KRW (11.74 billion USD) in 2014 to 14.5 trillion KRW (12.47 billion USD) in 2016. In 2017, the budget was slightly reduced. Together, the budget of the SMBA and the MSIP accounted for almost 6% of the total central government’s budget in 2015 and 2016. After President Moon had taken over the Blue House in 2017, the MSIP was dissolved and the SMBA was upgraded to the MSS. The budget of the MSS exceeded 10 trillion KRW in 2019 (8.6 billion USD), signaling a continued promotion of entrepreneurship.

Source: Based on Ministry of Economy and Finance (MOEF) (n.d.) Present Budget by Jurisdiction

Annual budget for SMBA, MSIP, and MSS, 2007–2019. Note: Unit: trillion KRW. The MSIP was founded in March 2013 and was thus not considered in the budget for 2013 yet. The SMBA was reorganized into the MSS in 2017.

Table 1 lists the major budget plans to foster startups and entrepreneurs under the Creative Economy initiative from 2014 to 2016, which includes increased startup funding like the tech incubating program for startups (TIPS) and expansion of support programs, including university education programs. Infrastructure measures, such as the expansion of the incubator-like Centers for Creative Economy and Innovation and the development of Pangyo Techno Valley, a technology hub in Gyeonggi Province, were supposed to create regional entrepreneurship ecosystems in support of startup activities.

Despite the positive impact of government support, some interviewees described the government’s efforts as too generous and therefore prone to moral hazard, creating wrong incentives for individuals who are not apt to run a business. The above-quoted expert EP3 continues: “[…] but I don’t think their approach is correct. […] I don’t think [TIPS (author’s note)] is a very healthy program because it’s too generous.” (EP3).

The abundant government support for initial financing is said to induce students to start a business for the purpose of obtaining another “spec” and eventually getting hired by a large enterprise: “Actually, some youngsters use that as a career. […] They are not interested in startup companies, not interested in their own company. They just did it so that they can make one line in their CV, resume.” (EP6).

Furthermore, the government has played an active role in developing Korea’s venture capital industry ever since it was initiated in the 1980s (Kenney et al. 2002:75–77). In fact, the immaturity of the Korean VC industry justifies a continued intervention of the Korean government until the present day, which in turn results in a misallocation of investment towards less risky and more mature businesses (Jones 2015:57) and a high dependency of the Korean VC market on the Korean central government.Footnote 16 Policy financial institutions contributed up to one-third to new fund formation in the VC industry between 2006 and 2016 (KVCA 2016:4).Footnote 17 Supported by the government, the VC market has grown in recent years: the number of VC companies jumped from 103 firms in 2014 to 115 firms in 2015,Footnote 18 the amount of new investments steadily increased since 2008, and the number of companies that received VC investment almost doubled between 2006 and 2016, standing at 1,399 in 2018 (see Table 2).

Experts see the growth of the VC industry as a positive development, but they also regard the government’s role in the VC industry and investment guidelines as a reason for the conservative investment behavior of venture capitalists. Therefore, some recommend an end of government investment activities:

Korea’s VC industry is not mature, so the government needs to drive the VC market. But Korea needs to change in that regard. If the government. doesn’t give money, some VC will close, so the startups cannot get money, that is the problem. But even if some VCs vanish (sic), the good ones would survive. The government should give more money to good VCs instead. 10 years ago, the government needed to drive the VC industry, but not anymore. (EP11)

Conclusion

Drawing on the institutional economic approach by North (1990) and Scott (2014), this article investigated the institutional environment for entrepreneurship in Korea and the latest changes thereof to explain the recent rise in entrepreneurial activities.

Figure 4 plots the major institutional changes against the development of entrepreneurial activities between 2000 and 2019. While there are ambiguous forces with respect to the cognitive and normative institutions in the 2010s, the changes in the regulative dimension are pronounced and therefore can be considered the main drivers of the increase in newly registered corporations.

This study’s results suggest that in comparison to Gupta et al. (2014), regulative institutions have improved since 2009. There are some initial changes in the cognitive and normative dimensions, but they do not seem to be the key drivers of entrepreneurial activities in Korea. This means that despite the obvious asymmetry between the institutional dimensions, newly established corporations have increased. Therefore, the results of this study support the findings in Stenholm et al. (2013) according to which regulative institutions are the main drivers of newly registered corporations. This contrasts with results by Bosma et al. (2018), who find that a small size of the government increases opportunity-driven entrepreneurship, and Valdez and Richardson (2013), who find the cultural-cognitive and normative institutions to be most decisive. It leads to the hypothesis that the different institutional dimensions are not of equal importance for entrepreneurial activities because regulative institutions set stronger incentives for occupational decisions and overrule hindering normative as well as cognitive institutions. Nevertheless, supportive normative and cognitive institutions might still be necessary to legitimize the encouraging regulative institutions in the long term and improve entrepreneurial quality. Additionally, this study also supports the theoretical argument that informal institutions change only after formal institutions.

Policymakers of the Moon administration have already worked on remaining regulative obstacles, e.g., by installing regulatory sandboxes. However, the government must also take possible moral hazards seriously. It is more difficult to give practical advice on the cognitive and normative institutions. Persisting occupational norms will undermine efforts to promote entrepreneurship education. To change the societal sentiment and appreciation for entrepreneurship, creative approaches are necessary, such as spreading a positive image about entrepreneurship via media and content industries.

There are limitations to this research. First, the qualitative single-country approach limits the generalizability of results and statistical inference on causality between institutions and entrepreneurship. Second, methodological issues like the sample selection and mixed language might have caused biases and should be treated with more care in the future.

Despite these flaws, this article provides a qualitative analysis that contributes to the understanding of institutions for entrepreneurship in the Korean context. Future research not only needs to pay attention to the effect of institutions on the quantity but also on the quality of newly established corporations.

Data availability

Interview questionnaires and transcripts are available upon request.

Notes

Purposive sampling is a nonprobabilistic sampling technique, which is based on the researcher’s specific selection criteria or subjective judgement about the quality of participants (Etikan 2016:2). This sampling technique is limited in drawing conclusions about the total population due to sampling bias (Etikan 2016:4).

Net enrolment ratio: number of children of (secondary) school age enrolled in (secondary) school divided by number of children of (secondary) school age. Gross enrolment ratio: number of individuals enrolled in tertiary education divided by number of individuals of tertiary education age.

Classification according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED), see OECD (2019: 19) for details.

All values in Korean Won (KRW) hereafter are converted into US-Dollar (USD) with the exchange rate of 01.01.2020 (1,000 KRW = 0.86 USD).

The KCSAT exam is developed and managed by the Korean Institute for Curriculum and Evaluation (KICE), which is commissioned by the Ministry of Education (MOE). The test format is mostly multiple choice. The score report includes not only the standard score but also percentile rank, which allows the results to be compared with all exam participants in Korea.

The term “spec” is used in Korean for various qualifications, certificates and experiences that are regarded as beneficial for one’s attractiveness in the labor market as they indicate a student’s competitiveness.

The Asan Nanum Foundation is a non-profit foundation established in 2011 to commemorate the 10th anniversary of the death of Hyundai’s late founder and chairman Chung Ju-yung.

Similar initiatives existed during the first venture boom in the late 1990s and early 2000s; however, the activities slowed down and revived only after the change of the president of KAIST in 2013.

In Korea, SMEs and small businesses are defined by their sector-specific average sales figures of the last three years.

Monthly remuneration varies by type of government official and is adjusted regularly.

Despite President Roh Moo-hyun’s (2003–2008) regional equity policy, centralization remains strong in Korea. See Lee (2009) for details on regional policies and balanced growth strategy in Korea.

Ninety percent of incorporated businesses in Korea are stock companies, so-called chusikhoesa, which is often mistranslated to Limited Liability Company (yuhanhoesa). But regardless of the legal business form and the respective degree of limited liability, the joint guarantee system is determined by the Commercial Law and the Civil Law in Korea (KET 2016).

English version: “Article 437 (Defense by Surety of Peremptory Notice and Inquiry): If an obligee has demanded performance of the obligation from the surety, upon proving that the principal obligor has sufficient means to effect performance and that the execution would be easy, the surety may enter a plea as a defense that the obligee must demand from the principal obligor and that he must first levy execution on the property of the principal obligor: Provided, That if the surety has assumed an obligation jointly and severally liable with the principal obligor, this shall not be apply.” Source: Civil Act (Enforcement Date 20.12.2016).

English version: “Article 57 (Joint and Several Obligations among Multiple Obligors, or between Obligor and Guarantor): (1) If two or more persons assume obligations arising out of transactions that are commercial activities in respect of one or all of them, they shall be jointly and severally liable for the obligations. (2) Where there is a guarantor, if the guaranty itself is a commercial activity, or if the principal obligation has arisen out of a commercial activity, the principal obligor and the guarantor shall be jointly and severally liable for the obligation.” Source: Commercial Act (Enforcement Date 02.03.2016).

The KOTEC Annual Report 2016 (KOTEC 2016:26) states: “The contributions from the government are transferred from the government’s General Account to KOTEC to facilitate KOTEC’s supply fund for technologically innovative SMEs with weak collateral capabilities. The contributions are provided to KOTEC every year directly from the government’s fiscal budget (KRW 50 billion in 2014 [43 million USD], 40 billion [34.4 million USD] in 2015 and 80 billion KRW [68.8 million USD] in 2016) in the form of public goods assigned to protect and foster technology startups and SMEs.”.

As a sign that government support is taken for granted, the KVCA states on its English homepage: “It is generally accepted that the Korean government plays an important role in supporting private fund-raising and investment in the market.” (KVCA n.d.).

Beside the strong role of the government in the fund-raising stage, Lee (2008:217–219) lists the short life span of outside funds with a duration of usually five years, IPO as the dominant exit form due to an underdeveloped M&A market, and the increasing proportion of expansion-staged invested firms as characteristics of the Korean VC market.

In 2018, 133 VC firms were registered.

References

Acs ZJ, Audretsch DB, Braunerhjelm P, Carlsson B (2012) Growth and entrepreneurship. Small. Bus Econ 39(2):289–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9307-2

Acs ZJ, Varga A (2005) Entrepreneurship, agglomeration and technological change. Small Bus Econ 24(3):323–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-005-1998-4

Ahn CY (2018) Income-led growth and innovative growth policies in Korea: challenges, rebalancing, and a new business ecosystem, KEI Acad Pap Ser, May

Aidis R, Estrin S, Mickiewicz (2009) Entrepreneurial entry: which institutions matter? IZA Discussion Paper 4123

Amsden AH (1989) Asia’s next giant: South Korea and late industrialization. Oxford University Press, New York

Aparicio S, Urbano D, Audretsch DB (2016) Institutional factors, opportunity entrepreneurship and economic growth: panel data evidence. Technol Forecast Soc Change 102:45–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.04.006

Audretsch DB, Keilbach MC, Lehmann EE (2006) Entrepreneurship and economic growth. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Bjørnskov C, Foss NJ (2016) Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth: what do we know and what do we still need to know? Acad Manag Perspect 30(3):292–315. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2015.0135

Bosma N, Content J, Sanders M, Stam E (2018) Institutions, entrepreneurship, and economic growth in Europe. Small Bus Econ 51(2):483–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0012-x

Braunerhjelm P, Acs ZJ, Audretsch DB, Carlsson B (2010) The missing link: knowledge diffusion and entrepreneurship in endogenous growth. Small Bus Econ 34(2):105–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9235-1

Bruton GD, Ahlstrom D, Li HL (2010) Institutional theory and entrepreneurship: where are we now and where do we need to move in the future? Entrep Theory Pr 34(3):421–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00390.x

Busenitz LW, Gómez C, Spencer JW (2000) Country institutional profiles: unlocking entrepreneurial phenomena. Acad Manag J 43(5):994–1003. https://doi.org/10.2307/1556423

Byun SY, Schofer E, Kim KK (2012) Revisiting the role of cultural capital in East Asian educational systems: the case of South Korea. Sociol Educ 85(3):219–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040712447180

Cha DS, Kim I (2010) Development of Korea’s financial policies and the financial market. In: Sung KJ (ed) Development experience of the Korean economy. Kyung Hee University Press, Seoul, pp 189–211

Cha DW (2015) The creative economy of the Park Geun-hye administration. Korea’s Economy 30:35–47