Elizabeth Lavolette, Kyoto Sangyo University, Japan

Matthew Claflin, Kyoto Sangyo University, Japan

Lavolette, E., & Claflin, M. (2021). Comparing Japanese and US language spaces: A case study. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 12(4), 341–364. https://doi.org/10.37237/120403

Abstract

Language spaces worldwide have much in common. However, we believe that there is a meaningful difference between spaces that are considered “language centers” in the US (USLCs) and “self-access language centers” (SALCs) in Japan. These differences provide an opportunity for practitioners and scholars involved in language spaces to learn from each other. In the current article, we investigated the Global Commons at Kyoto Sangyo University for the characteristics of both USLCs and SALCs by collecting information about it from publicly available sources and from interviews with staff. We show that it can be considered an administrative SALC (Mynard, 2019) and show how it fulfills some of the USLC mandates (Lavolette, 2018) but not others. We discuss the implications of these characterizations, including how the Global Commons could be more useful to its stakeholders. Based on this case study, scholars of both SALCs and LCs can gain new ideas for services and roles that will benefit their stakeholders and facilitate change.

Keywords: language center, self-access center, case study, interview

Language spaces worldwide have names that include the terms self-access, center, commons, and hub, to name only a few examples. Despite the varied nomenclation, these spaces have much in common. However, we believe that there is a meaningful difference between spaces that are considered “language centers” in the US (USLCs) and “self-access language centers” (SALCs) in Japan. These differences provide an opportunity for practitioners and scholars involved in language spaces to learn from each other.

One way to exploit this opportunity is to examine a language space for the characteristics of both USLCs and SALCs. This can serve as a needs analysis that results in suggestions for improvement, some of which may be novel for the space’s context. As an example, the current study provides a case study of a language space in Japan, showing where it fits into Mynard’s (2019) taxonomy of SALCs in Japan and how it does and does not fulfill the US language center mandates (Lavolette, 2018).

The Relationship Between SALCs and USLCs

Lavolette and Kraemer (2017) defined a language center as “a physical and/or virtual space that supports foreign and/or second language learning and/or teaching within a larger educational institution” (p. 149). Given their similar purposes, this definition is not specific enough to distinguish USLCs from the self-access language centers (SALCs) more commonly found in Japan (and many other parts of the world). The definitions in the SALC literature present a similar situation. For example, Benson (2001) defined a SALC as “any purpose-designed facility in which learning resources are made directly available to learners” (p. 114). When these two definitions are considered together, SALCs are a subset of USLCs because SALCs support learning, but not teaching. However, Lavolette and Claflin (2019) pointed out similarities and differences between the two types of language spaces that indicate an intersectional relationship (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Relationship Between Self-Access Language Centers (SALCs) and US-style Language Centers (USLCs), Based on Lavolette and Claflin (2019).

SALCs and USLCs have much in common. First, both SALCs and USLCs generally have a physical space. Benson’s (2001) definition of a SALC mentioned a “facility,” and Swanson and Yahiro (2012) similarly used the word “facilities” in their definition (p. 115). As Cotterall and Reinders (2001) wrote, “A Self Access Centre consists of a number of resources (in the form of materials, activities and support) usually located in one place… Self-Access Language Learning is the learning that takes place in a Self-Access Centre” (p. 24; emphasis added). All of these definitions imply a physical space, rather than a virtual one. In contrast, the definition of a USLC allows for the possibility of a fully virtual space. However, Lavolette and Kraemer (2021) reported that 92% of USLCs provided physical lab spaces in 2019, showing that most USLCs, like SALCs, have physical spaces.

Second, SALCs and USLCs tend to be provided by institutions of higher education, rather than primary or secondary institutions (K–12). The Japan Language Learning Spaces Registry (managed by the Japan Association for Self-Access Learning, jasalorg.com), which allows anyone to list a SALC, contains only university SALCs (as of November 23, 2021). Similarly, Lavolette and Kraemer (2021) reported that fewer than 5% of language center directors who participated in the International Association for Language Learning Technology (IALLT) surveys in 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019 were employed at K–12 institutions. One possible explanation for this is that the directors of USLCs outside higher education generally do not respond to the IALLT survey. However, this is unlikely given the many K–12 members of IALLT and its outreach to these educators. The most likely explanation is that few USLCs are located in K–12 institutions.

Third, both SALCs and USLCs originated in the language labs of the 1970s. These early language labs were based on audiolingual methodology, which is in turn based in behaviorist views of language acquisition. As cognitivist theories became popular among educators in the early 1970s, universities in Europe needed to find a use for the audiolingual labs (Mach, 2015). As David Little put it, “The answer seemed obvious: make them available to students for self-instructional use. Thus was the university self-access centre born” (Little, 2015, p. 14). USLCs also originated in the audiolingual language labs, but maintained a focus on technology, becoming multimedia learning centers by the late 1980s (Roby, 2003).

Fourth, despite how language labs forked into SALCs and USLCs during the 1970s, the evolution of both is now toward social learning spaces (e.g., Jeanneau, 2017; Kronenberg, 2017; Mynard, 2016; Sebastian et al., 2021; Werner & Von Joo, 2018). In Japan, for example, Garold Murray described the SALC at Okayama University by noting that “the emphasis in the L-café is on learning through informal social interaction” (Murray, 2017, p. 185). Going beyond anecdotal evidence, Lavolette and Kraemer (2021) found that in the US, the percentage of language centers providing social spaces rose from 53% in 2013 to 77% in 2019.

Most importantly, SALCs and USLCs share a mission of supporting language learning. Each side should therefore be interested in not only the ways in which other language spaces are providing similar services, but also the different services that fulfill the same mission. SALCs generally focus on learner autonomy, including providing learner advising (Gardner & Miller, 1999, p. 9). USLCs, on the other hand, often provide professional development for language teachers (70% of USLCs in 2019, according to Lavolette & Kraemer, 2021).

These generalizations are useful in understanding language spaces in a broad sense. However, this is just the beginning of a taxonomy of language spaces. For example, Naomi Fujishima observed that the L-café at Okayama University did not employ learning advisors. She therefore referred to it as a social learning space, rather than a SALC (Fujishima, 2015, p. 462). Similarly, as we will show, the Global Commons (GC) at Kyoto Sangyo University (KSU) cannot readily be classified as either a SALC or USLC.

What are the Characteristics of USLCs and SALCs?

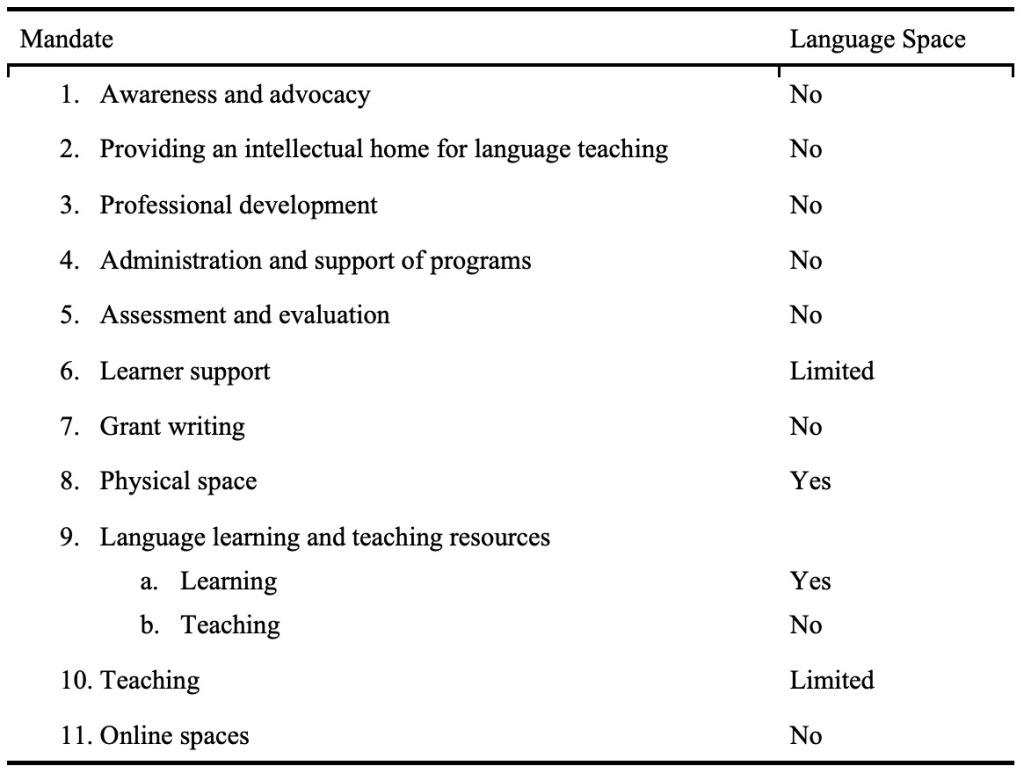

Mynard’s (2019) typology of SALCs in Japan divides centers into social-supportive SALCs, developing SALCs, and administrative centers, depending on the characteristics they exhibit (see Table 3 for the full list). Social-supportive SALCs exhibit characteristics such as a commitment to promoting learner autonomy and providing social spaces with opportunities for learners to use their target languages. Mynard claimed that these social-supportive SALCs are ideal from the perspective of supporting learners, so we adopt her characteristics of these SALCs to analyze the GC.

Turning to USLCs, Lavolette (2018) provided a list of mandates for these centers, which included learner support and the provision of physical and online spaces (see Table 4 for the full list). These mandates are based on a synthesis of previous USLC literature and questionnaire data collected from USLC directors. Thus, the mandates are not necessarily representative of what any given LC does. Instead, they were offered as an ideal for LCs to strive for, with the understanding that every LC has different affordances and limitations. We adopt these mandates here as a description of USLCs to analyze the GC.

In the current article, we investigate the GC as a case study using information gathered about it from publicly available sources and from interviews with staff. The GC’s context is Japan, so we first attempt to classify it using Mynard’s (2019) typology of SALCs in Japan. Next, to determine its similarities with and differences from USLCs, we explore its fulfillment of the language center mandates (Lavolette, 2018). We then discuss the implications of this classification, including how the GC could be more useful to its stakeholders and how stakeholders of language spaces can benefit from our analysis.

Method

Before we explain the research methods, some background on the authors is needed to understand our relationship to the Global Commons. The first author has first-hand experience in USLCs, including as a former director, but is not involved with the GC. Since beginning work at Kyoto Sangyo University, she has been curious about the GC and wanted to know more about it. The second author was instrumental in the planning of the GC but has had less involvement in the implementation of the plan and the daily operations. He remains on the GC steering committee, but this committee has little impact on the day-to-day running of the GC. As one of the reviewers of this paper pointed out, our positions as KSU employees gave us prior knowledge about the GC that made it impossible to be objective observers. That said, we made every attempt to put our preconceptions aside, ask unbiased questions (see Appendix), and learn about the GC from the perspectives of our participants.

Our investigation was guided by the following question: How does the Global Commons fit the characteristics of SALCs and USLCs? To address this question, we accessed publicly available materials on the GC website and conducted interviews with full-time GC staff and student staff.

Participants

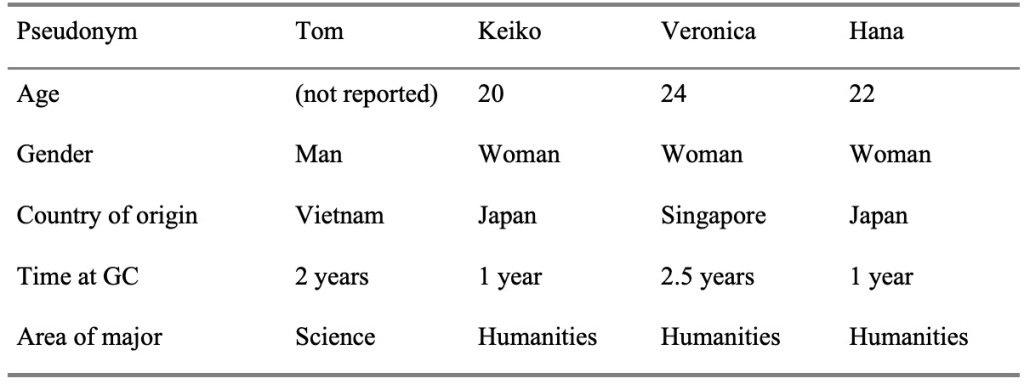

In the fall of 2019, three types of staff were working at the GC: part-time staff, full-time staff, and student staff. We interviewed all three of the full-time staff members (Table 1) but none of the part-time staff members. Of the 18 members of the student staff, we interviewed all four who volunteered to participate in this study (Table 2). All names used are pseudonyms.

Table 1

Global Commons Full-time Staff

Table 2

Global Commons Student Staff

In addition to the interviews with GC staff, we used the publicly available GC website to find information such as the mission statement, schedule of events, and the system for students to submit questions.

Procedure

We conducted, recorded, and transcribed semi-structured individual interviews with each participant in the fall of 2019. We interviewed each participant once, face-to-face. Full-time staff interviews lasted from approximately 40 to 55 minutes, and student staff interviews lasted from 20 to 45 minutes. We prepared a list of questions (see Appendix) and asked additional questions depending on the responses.

We gave each participant the choice of whether to participate in the interview in English or Japanese. All participants chose English, although some used Japanese occasionally. All quotes from participants are transcribed verbatim, and we do not include “sic” or other indicators of nonstandard forms.

Analysis

We transcribed the interviews and gathered further information from the GC website. Then, we reviewed the data and translated it into English, as necessary, to provide a basic description of the GC. In addition, the data were coded into apriori themes that correspond to Mynard’s (2019) taxonomy (14 characteristics; Table 3) and Lavolette’s (2018) 11 language center mandates (Table 4). The goal of the coding process was not to categorize all of the data but to find evidence for and against the hypothesis that the GC has each characteristic or fulfills each mandate. To perform the coding, we read and reread all of the data to become familiar with it. The first author performed the initial coding, then the second author checked the coding and added data that had been overlooked. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Findings

Description of the Global Commons

The Global Commons at Kyoto Sangyo University is on the first floor of a five-story building (completed in 2016), centrally located on the campus. The GC has an open design with glass walls, which makes its contents visible from both inside and outside the building. On its webpage, the GC is described (in Japanese only) as a place where, through the self-study of languages, students can feel closer to the world. The “concept” or mission statement of the GC, which is also shown on the website, outlines how, through the provision of resources, workshops, and support from staff with international experience, the GC works to encourage the development of (future) graduates.

The GC is a space that students and staff in the interviews described as “awesome” (Veronica), “clean and comfortable” and “beautiful,” (Kana) and “cafe”-like (Mary). As shown in Figure 2, it has various zones, including a free space with movable furniture (2), an “advising area” where student staff sit (5), group study rooms (8), and a resource space that houses language materials (9).

Figure 2

Diagram of the Global Commons Physical Layout

Note. Image courtesy of the Global Commons at Kyoto Sangyo University

The materials in the resource space cover 10 languages and include around 4,500 books, magazines, and newspapers. Most of these printed materials are for extensive reading but also include language learning and testing materials, cultural reference materials, and travel guides. The GC also has a collection of around 4,000 DVDs in a range of genres.

At the time of the interviews, between 20 and 30 workshops per semester were run by full-time staff members on topics related to English study, such as test-taking and giving presentations. Daily “Chat in English” (and other language) events were run by student staff. An online form allowed students to apply for a private session with a full-time staff member to work on English or academic skills.

SALC Characteristics

The characteristics of social-supportive SALCs (Mynard, 2019) are listed below, with explanations of whether the GC has them.

Philosophy: A Commitment to Promoting Autonomy in the Language Learner

The concept of the GC does not include any reference to autonomy.

Resources: Funding for Language-Related Materials (Print, Media, Digital) and Funding for General Materials (in the Target Language) of Interest to Learners

Kana, who was in charge of purchasing materials for the GC, explained that the GC had funds for books, magazines, and DVDs that were both language-related and general, such as manga, picture books, and cooking and travel books.

Facilities: Provision of Furniture, Rooms, Spaces, and Equipment Needed to Work on Different Kinds of Language-Related Activities (Including Some Quieter Places)

The GC provides movable tables and seating, DVD-viewing booths, an individual study counter, an area for student staff to hold chat sessions, and group study rooms, in addition to other spaces (Figure 2). Kana explained that students can borrow laptops and iPads.

Communities: Availability of Social Spaces for Users to Engage in Community Activities

As Tom noted, the GC is a space where students can socialize: “To be frank, I think they take this place in general is another library. But they can talk, not like in the real library. So around 70% of them are studying, either self-study or study in groups.” Note that not all users are studying, as Veronica said: “Sometimes when they don’t have classes, they just come down to GC and they just talk to people instead of studying.” Hana also explained that the GC was a good place to meet exchange students. Thus, students could engage with their friends and classmates and meet new people in the GC.

Communities: Opportunities to Use the Target languages with Other language Users

Student staff provided opportunities to “chat” in other languages, usually working in pairs. Keiko described their main duty as follows: “We have English conversation activity 3 times, 11:30, 1:30 and 3:30.” While these specific time slots are scheduled and announced, the opportunity for students to come and chat in English goes beyond the three time slots. As Mary stated, “student staff… is always there from 10:45 to 4:30. If somebody come to chat in English, they are always there.” Chat activities in other languages are also offered, depending on the abilities of the student staff. For example, Keiko held sessions in German and the Hiroshima dialect of Japanese, and Veronica held sessions in Singlish.

Communities: Opportunities for Learner Involvement in the Running of the SALC

Student staff members have an impact on how the center is run. As Hana said:

For example, before and after semester, the staff usually come to us and we will just talk about how we should improve the chat or some activities. And at the end of every shift, we will have to submit a report. So there’s a comment section, so we can basically just write anything that we want, like if we have some ideas, we can also write it in.

She further explained that she felt that the full-time staff listened to her ideas “because they do reply to your comments every day, so that’s great”.

The full-time staff also solicited learner involvement in other ways. As Kana mentioned:

And we ask also how to organize. I just asked one student…she’s been using this facility for three years, two years. But she didn’t know there was a newspaper here, so we ask them “Where should we put this, this newspaper.” And she suggested this place. So we ask suggestions from students. How we should do this to make this place better. So we want them to feel responsible to maintain this facility.

Support: Availability of Learning How to Learn (Materials, Courses, Posters, Leaflets, Workshops)

No mention was made of workshops or materials on learning how to learn.

Support: An Advising Service

At the GC, full-time staff provided individual English language support to students, as Kana explained, “We can offer how to study or we can give them advice how to do presentation or how to organize your paper, but we don’t really check what they write, so not many students.” Aspects of what the staff did in these support sessions could be considered advising, such as providing advice on how to study. However, given the lack of focus on learner autonomy in the sessions, we conclude that the GC did not offer an advising service.

Support: Teachers and/or Teaching Assistants Available for Language Support and Practice

No teachers or teaching assistants were available in the GC.

Support: A Help Desk and/or Information Counter

The GC has a reception desk (marked “1” in Figure 2) where students can ask for help.

Support: Administrative Support

The GC has the university’s official administrative support.

Innovation: Freedom for Innovation

The full-time staff indicated that they wanted to innovate, such as by promoting the center to new students at orientation or by creating social media accounts. However, their ideas were rejected by their supervisors, so we conclude that they do not have freedom to innovate.

Innovation: Support for Research

Research was outside the scope of the GC’s concept and the full-time staff members’ job duties.

Summary: Which type of SALC is the Global Commons?

The characteristics of the GC according to Mynard’s (2019) typology are summarized in Table 3. A social-supportive SALC would have all of the characteristics shown. The characteristics that the GC has are those of an administrative center, plus the characteristic of funding for general materials and the three “communities” characteristics.

Table 3

Characteristics of the Global Commons, Based on Mynard’s (2019) Typology of SALCs in Japan

Language Center Mandates

The language center mandates (Lavolette, 2018) are a description of what USLCs do and aspire to do, based on expert opinion (e.g., Askildson, 2011; Garrett, 2003; Liddell & Garrett, 2004) and questionnaire data collected by the International Association for Language Learning Technology. A given USLC is unlikely to fulfill all of the mandates, and not all of the mandates are appropriate for every USLC. Therefore, we did not expect the GC to fulfill all of the mandates. Rather, we examined how the GC does or does not fulfill each of the 11 mandates as a starting point for comparing the GC to USLCs.

Mandate 1: Awareness and Advocacy

Lavolette (2018) stated, “a language center cannot function if students, faculty, staff, and other center stakeholders are not aware of its existence and services” (p. 9). In addition to promoting awareness of the USLC itself, a USLC should also advocate for improved working conditions for language faculty.

Starting with the GC’s means of spreading awareness, it is centrally located and visible from the outside, and it features on the university web page. Promotion beyond the website is a challenge the GC was struggling with. All three full-time staff members expressed frustration with the level of awareness on campus and with a policy that limited promotion to some posters around campus and notices on the internal university online bulletin board.

The overall management structure of the GC inhibited awareness and advocacy in other ways. The GC was managed by an educational support center, who, in Yoshiko’s words, “are specialists in the administrative work, not in the learning support section. Actually, if I have a question about, for example, doing the workshop, like English presentation things, or sometimes we have a new idea to do the workshop… there is no leader position staff to our area, so it’s a kind of very difficult thing to communicate with them.”

In sum, the GC promotes itself to a limited extent, but is constrained by policy and a lack of senior leadership. This lack of leadership also prevents any advocacy role.

Mandate 2: Providing an Intellectual Home for Language Teaching, Mandate 3: Professional Development, and Mandate 4: Administration and Support of Programs

The GC lacks an academic director, and the mission statement does not include professional development. Without any senior leadership or mission to do so, the GC was clearly not positioned to administer or organize support for language programs. Therefore, the GC has little relationship to Mandates 2, 3, and 4.

Mandate 5: Assessment and Evaluation

Lavolette (2018) indicated that USLCs “should coordinate, support, and administer language assessment” for a wide variety of purposes (p. 11) and that USLCs should play a role in the evaluation of language programs, in addition to USLCs themselves being evaluated (p. 12). Without an academic director, the GC is unable to be involved in program evaluation.

The GC is also uninvolved in assessment, although it provides study materials for a range of language tests and offers some workshops for students on language tests such as the TOEIC (see Mandate 6).

Mandate 6: Learner Support

This mandate may be the most relevant one to the GC. Veronica, one of the student staff members, commented, “We also have this learning support [unclear], so students who have difficulties with their English, they can always come here, make an appointment with the staff, and the staff will help them.” Mary, one of the full-time staff members, said that her fellow staff members see the GC as “a very good facility to give a lot of opportunity to learn English through our workshop [where] we can offer any kind of study support specializing in language learning or qualification test related to English or Japanese or any other language.”

Learner-support opportunities took several forms: Workshops and one-to-one advising sessions, provided by the full-time staff, and opportunities to “chat” in other languages, led by student staff members. However, all of the staff members mentioned that attendance was a problem and a source of frustration. As Mary put it, “Even if we have activities and workshops every day, not so many students join us. This is a waste of everything: the time and the facilities and the opportunities.”

The full-time staff provided individual student support, but they seemed to find communicating the purpose to be challenging. The staff also seemed to be disappointed in the number of students who used the advising service. As Yoshiko said, “This autumn’s term only one up to now, but in the spring term, I think, less than 10 unfortunately.”

The student staff members were generally enthusiastic about the chat activities. Keiko said, “I sometimes joined Chat in English, like, it’s event the student staff held. It’s really interesting. And I want to improve my English skill at this event. That’s why. I want to help this event for other students.” However, frustration was common among student and full-time staff members that “not so many students are coming for the chat” (Mary). Veronica stated the number of students coming “can be mostly zero.”

To summarize, the GC provided various forms of learner support, but those opportunities were underused by students.

Mandate 7: Grant Writing

Lavolette (2018) stated that “Some language centers are supported mainly by grants” (p. 12). However, this is not the case for the GC. It lacks an academic director and a research mission, so it has no need or ability to be involved in grant writing.

Mandate 8: Physical Space

Scholars have raised questions about the necessity of physical language spaces (e.g., Garrett, 2003; Kronenberg, 2016), and the COVID-19 pandemic has forced these spaces to become fully virtual for periods of time. However, Lavolette (2018, p. 12) concluded that physical spaces are needed, and we believe that this is still true. If physical spaces are necessary, Kronenberg’s (2016) design criteria should be met: flexibility and adaptability, mission-based design, situatedness, social space, and deemphasis of technology.

The GC has a flexible and adaptable layout. As shown in Figure 2, it has many open, adjustable spaces with moveable furniture that can be reconfigured to suit various purposes.

Mission-based design, according to Kronenberg (2016), means that architects should not make decisions about how a space will be used. Rather, everyone who will use the space should be a part of the design process. In the case of the GC, the design team included the second author and several administrative staff members. Several workshops and ongoing consultations were used to obtain input from faculty members involved in managing language programs throughout the university. Input was also solicited from students in the Faculty of Foreign Studies.

The GC is physically well-situated on the first floor of a centrally located building, and it was designed with an emphasis on social spaces, as described above. It deemphasizes technology in that it has no associated computer lab or computers installed in the center. Because the GC meets each of Kronenberg’s (2016) design criteria, it fulfills the mandate of physical space.

Mandate 9: Language Learning and Teaching Resources

US language centers “should provide language learning and teaching resources to students, faculty, and staff” (Lavolette, 2018, p. 13). While the GC has many learning resources, it limits the lending of materials to students, so this mandate will be considered from the student perspective only.

The GC has “a lot of books, DVDs” (Keiko) and provides computers and iPads for students to check out for individual work in the center. The overall impression of both full-time staff and student staff is well summarized by Kana’s comment, “I think it’s great because we don’t have only resources for classes or university [but also] manga books and students can learn and having fun with those books. Also picture books, cooking and travel, books for travel, so I think it helps students become interested in English or other languages, not only English.”

The most popular resource is the DVDs: “Many students reserve the DVD booths to watch DVDs with their friends” (Mary). In fact, the DVD booths (which are enclosed with low walls) are popular with couples and are “one of the dating spot” (Hana). Keiko stated that the selection of English DVDs in particular “is really good.”

Yoshiko expressed some concerns about how well the resources were meeting students’ needs. She said, “according to the data from the counter staff, they say that some books are not borrowed by any students. So, maybe teacher carefully selected the books, but not all the books are not, how should I say, the student like. Some students want to read more casual topics. Some students want to read more serious story, maybe, I don’t know. The other problem is we don’t know how to grasp their needs or they want to do here.”

In sum, the GC fulfills the mandate for learning resources for students, although it has room for improvement. On the other hand, there are no resources relating to pedagogy or language teaching, and faculty and staff are not permitted to borrow materials.

Mandate 10: Teaching

Full-time GC staff members taught workshops for students in a range of areas, including those related to language instruction. They also offered one-to-one English language help sessions. Kana emphasized the difficulties in attracting students to the sessions: “We don’t really have many participants for workshop.” We can thus say that, while GC staff do provide language instruction, the workshops are poorly utilized by the student body.

Mandate 11: Online Spaces

The GC provided no online spaces or vetting of online resources, aside from its webpage offering a guide to what was in the GC and how to use it.

Summary: Which Mandates Does the Global Commons Fulfill?

In light of Lavolette’s (2018) mandates, the lack of a dedicated in-house academic director combined with a lack of a clear role in managing or supporting language programs and testing means that it is impossible or impractical for the GC to provide an intellectual home for language teaching (Mandate 2), professional development (Mandate 3), administration and support of programs (Mandate 4), assessment and evaluation (Mandate 5), and grant writing (Mandate 7). In addition, systemic limitations, both in terms of staffing and university policy, mean that few resources are devoted to awareness and advocacy (Mandate 1) and that online spaces (Mandate 11) do not exist beyond a basic webpage. However, the GC does provide a beautiful and attractive physical space (Mandate 8) with extensive language learning (although not teaching) resources (Mandate 9). It also provides limited learner support (Mandate 6) and teaching (Mandate 10), although both are underused by students because the GC lacks a clear role in university programs and is poorly advertised.

Table 4

Mandates Fulfilled by the Global Commons, Based on Lavolette’s (2018) Language Center Mandates

Discussion

Based on information gleaned from the website of the Global Commons and the comments from the participants organized in terms of the frameworks provided by Lavolette (2018) and Mynard (2019), it is clear that the GC fulfills few of the USLC mandates and lacks many of the characteristics of social-supportive SALCs. Despite not being fully classifiable as either type of language space, however, it does embody some characteristics of both SALCs and USLCs, most notably, an appealing and well-located physical space and useful learner support and resources.

The frustration of the staff participants with such factors as the lack of freedom to innovate, both in terms of programs and advertising, shows that they feel the GC could be much more. Based on the examination of the GC in the two frameworks, the GC may be regarded as an underdeveloped language space that has much potential. As Mynard (2019) wrote about SALCs, “Type 1 [social-supportive] is the ideal in terms of learner support, but with sufficient investment and institutional support, Types 2 [developing] and 3 [administrative] could shift to be more like a Type 1 SALC” (p. 193). Indeed, with sufficient investment and institutional support, the GC could become a social-supportive SALC, a USLC, or even a hybrid center that included characteristics of both. The positive view of the space and materials by the student participants suggests that developing the space to become any of these would likely have a positive influence on language learning at the university.

Three factors suggest a need for qualified leadership: The relatively short period of time the full-time staff participants had been working in the GC, the fact that they were all on contract (rather than permanent employees), and their comments that the management of the facility lacked an understanding of matters beyond administration. As we showed above, many of the USLC mandates require a dedicated in-house academic director, and this leadership might also be required if the GC were to transition to a social-supportive SALC. To be effective, a director would need stability in their role (i.e., tenure), rather than a contract-limited position. A role that rotated among faculty members, which is common in Japan, would also be unlikely to provide appropriate stability for the GC because faculty with little interest in the GC and without an appropriate background might also be asked to take the role.

Full-time staff participant comments also made it clear that the management hierarchy is problematic. To respond flexibly to student and faculty needs, a director would need the authority to make most decisions, including budgetary decisions, without getting permission from senior management.

In addition to appropriate leadership, a language space also needs ongoing financial investment to fulfill its mission. While the GC has an ongoing budget for resources, there is no funding for staff training or funding for research. If the GC were to become a social-supportive SALC, the staff would need to be trained in learner autonomy support, including learning advising. On the other hand, if the GC were to become a USLC, the staff would need to be able to provide language pedagogy support, such as workshops in using technology in the classroom. In either case, the staff would need support for conducting research on how the center can better support language learning and/or teaching.

Neither author of the current study can claim to be objective in suggesting that an academic director is key to improving the effectiveness of the GC. In fact, the original proposal for the GC by the second author’s team included a dedicated director and academic staff. However, for budgetary reasons, no director was appointed, and appointing a director would now require a decision from senior management. Unfortunately, this seems unlikely to happen in the near term, given that the coronavirus pandemic has tightened budgets. In addition, convincing administrators that the GC should be changed may be difficult. After all, the participants in the study commented positively on the appearance of the GC, and it is often full of students, even if they are not necessarily using the language resources or accessing language learning support services. The GC also regularly features in university advertising materials. From numerical and visual perspectives, the GC is a great success.

Conclusion

We hope that this example of examining a language space in Japan through Mynard’s (2019) taxonomy of SALCs in Japan and Lavolette’s (2018) US language center mandates may provide inspiration for improving language spaces. The struggle to demonstrate the benefits of a fully realized language space versus its expense is yet another commonality of USLCs and SALCs. Therefore, we hope that faculty and staff of all types of language spaces can gain some new ideas for services and roles that will help administrators see the benefits and thus facilitate positive change.

Further research is required into the similarities and differences of not only SALCs and USLCs themselves, but also into their organizational structure and their perceived roles at the institutional and state level. We intend to create a taxonomy of language spaces that includes Lavolette’s (2018) USLC mandates and Mynard’s (2019) taxonomy of SALCs in Japan, eventually expanding to a description of global language spaces. This requires further investigation of language spaces in the US, Japan, elsewhere in North America and Asia, Europe, and beyond. Such a taxonomy will help scholars worldwide to engage with literature from other parts of the world and benefit from sharing ideas.

Notes on the Contributors

Elizabeth (Betsy) Lavolette, PhD, is Associate Professor of English at Kyoto Sangyo University in Kyoto, Japan. Her research focuses on language learning spaces, especially in the US and Japan. She is also interested in professional development and the use of technology in teaching and learning.

Matthew Claflin is an Associate Professor in the English Department, Faculty of Foreign Studies, Kyoto Sangyo University. His research focuses on extensive reading, EMI and CLIL, and internationalization in higher education.

References

Askildson, L. (2011). From lab to center: A vision for transforming a language learning resource into a language learning community. In F. Kronenberg & U. S. Lahaie (Eds.), Language center design (pp. 11–21). International Association for Language Learning Technology.

Benson, P. (2001). Teaching and researching autonomy in language learning. Longman.

Cotterall, S., & Reinders, H. (2001). Fortress or bridge? Learners’ perceptions and practice in self access language learning. Tesolanz, 8, 23–38. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.612.2119&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Fujishima, N. (2015). Training student workers in a social learning space. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 6(4), 461–469. https://doi.org/10.37237/060413

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing self-access: From theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Garrett, N. (2003). Language learning centers: An overview. In U. Lahaie (Ed.), The IALLT management manual (2nd. ed., pp. 1–9). International Association for Language Learning Technology.

Jeanneau, C. (2017). Redefining language centres as intercultural hubs for social and collaborative learning. In F. Kronenberg (Ed.), From language lab to language center and beyond: The past, present, and future of the language center (pp. 61–82). International Association for Language Learning and Technology.

Kronenberg, F. (2016). Curated language learning spaces: Design principles of physical 21st century language centers. IALLT Journal, 46(1), 63–91. http://doi.org/10.11139/cj.30.3.307-322

Kronenberg, F. (2017). From language centers to language learning spaces. In F. Kronenberg (Ed.), From language lab to language center and beyond: The past, present, and future of the language center (pp. 161–165). International Association for Language Learning and Technology.

Lavolette, E. (2018). Language center mandates and realities. In E. Lavolette & E. Simon (Eds.), Language center handbook (pp. 3–33). International Association for Language Learning Technology.

Lavolette, E. (2019). A very brief introduction to US language centers. In L. Xethakis, & C. Taylor (Eds.), JASAL 2018 x SUTLF 5: Selected papers from the Sojo University Teaching and Learning Forum 2018: Making connections, 4–25.

Lavolette, E., & Claflin, M. (2019, November 30-December 1). Is it a SALC? A case study of the Global Commons at Kyoto Sangyo University [Presentation]. Japan Association for Self-Access Learning (JASAL) annual conference 2019, Osaka, Japan. https://jasalorg.com/jasal2019-osaka-november30-december01/

Lavolette, E., & Kraemer, A. (2017). The language center evaluation toolkit: Context, development, and usage. In F. Kronenberg (Ed.), From language lab to language center and beyond: The past, present, and future of the language center. International Association for Language Learning Technology.

Lavolette, E., & Kraemer, A. (2021). Language center trends: Insights from the IALLT surveys, 2013–2019. In E. Lavolette & A. Kraemer, (Eds), Language center handbook 2021 (pp. 107–136). International Association for Language Learning Technology.

Liddell, P., & Garrett, N. (2004). The new language centers and the role of technology: New mandates, new horizons. In S. Fotos & C. M. Browne (Eds.), New perspectives on CALL for second language classrooms (pp. 27–40). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Little, D. (2015). University language centres, self-access learning and learner autonomy. Researching and Teaching Languages for Specific Purposes, 34(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.4000/apliut.5008

Mach, T. (2015). Promoting learner autonomy through a self-access center at Konan University: From theory to proposal. The Journal of the Institute for Language and Culture, 19, 3–29. https://www.konan-u.ac.jp/hp/mach/cv/MACHkiyo2015_SALC_and_autonomy.pdf

Murray, G. (2017). Autonomy and complexity in social learning space management. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 8(2), 183–193. https://doi.org/10.37237/080210

Mynard, J. (2016). Self-access in Japan: Introduction. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 7(4), 331–340. https://doi.org/10.37237/070401

Mynard, J. (2019). Self-access learning and advising: Promoting language learner autonomy beyond the classroom. In H. Reinders, S. Ryan, & S. Nakamura (Eds.), Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching (pp. 185–209). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-12567-7_10

Roby, W. B. (2003). Technology in the service of foreign language learning: The case of the language laboratory. In D. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 523–541). The Association for Educational Communications and Technology. http://www.aect.org/edtech/ed1/19.pdf

Sebastian, P., Gopalakrishnan, S., & Hendricks, H. (2021). Language laboratories and centers: Looking to history and anticipating the future. In E. Lavolette & A. Kraemer (Eds.), Language center handbook 2021 (pp. 3–30). International Association for Language Learning and Technology.

Swanson, M., & Yahiro, H. (2012). Attributes of successful self-access learning centres. Bulletin of Seinan Jo Gakuin University, 16, 113–122. https://cir.nii.ac.jp/ja/crid/1050282812544079360

Werner, R. J., & Von Joo, L. (2018). From theory to practice: Considerations in opening a new self-access center. Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal, 9(2), 116–134. https://doi.org/10.37237/090205

Appendix

Interview Questions

Questions for full-time staff

Job

- What is your educational background? Related work experience?

- When did you begin working here?

- Why did you want the job?

- What is your typical day like?

- What are your job duties?

- Who do you report to?

- Who reports to you?

- How many hours do you work in a day? In a week?

- What projects are you working on?

- What projects would you like to do in the future?

- Do you hire student staff? What is the process?

GC

- Describe the GC.

- How is the GC different from what you imagined?

- Is the GC a self-access center? Why or why not? How does it promote learner autonomy?

- What is the GC’s mission?

- Does the GC support students? Study abroad students? Faculty? Staff? Community members? Teaching? Research? Study abroad prep/return?

- Is the space and location adequate for the mission?

- What GC resources are the most popular? What resources are missing or could be augmented?

- Where does the GC budget come from? Who controls it? What can it be used for? Is it adequate for the mission?

- What services does the GC offer?

- What times of day is the GC busiest?

- What activities do students do at the GC?

- How do faculty use the GC?

Opinions

- What do you think the GC does well?

- How do you think the GC could be improved?

- What are the GC’s most significant achievement(s) since you began working there?

- What ongoing significant challenges has the GC been experiencing since you began working there? How have you addressed these challenges?

- Why is the GC important to language education?

Connections

- How do you promote awareness of the GC among students? Faculty?

- Does the GC write grants?

- What is the GC’s relationship to other units at Institution? (e.g., study abroad, language departments, other Commons, library)

Questions for student staff:

- What is your major? What year are you?

- What country are you from?

- When did you begin working here?

- Why did you want the job?

- How many hours do you work in a day? In a week?

- Who do you report to?

- What is your typical shift like?

- What are your job duties?

- Describe the GC.

- What is the GC’s mission?

- Why is the GC important to language education?

- Why is the GC important to study abroad?

- What do you think the GC does well?

- How do you think the GC could be improved?

- What GC resources are the most popular? What resources are missing?

- What services does the GC offer?

- What times of day is the GC busiest?

- What activities do students do at the GC?

- How and when did you use the GC before becoming a staff member?