Abstract

Prior research indicates that employees from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to experience depression and other mental health problems than their ethnic majority counterparts. To understand what drives these negative outcomes, we integrate research on ethnic minorities at work with the job demands-resources (JDR) model. Based on the JDR model, we consider climate for inclusion as a key job resource for ethnic minority employees that mitigates the deleterious effects of ethnic minority status on job self-efficacy, perceived job demands, and depressive symptoms. We conducted a two-wave survey study (Time 1: N = 771; Time 2: N = 299, six months apart) with employees from five medium sized not-for-profit and local government organizations in Australia. Our empirical results indicate that ethnic minorities report a higher job-self-efficacy and fewer depressive symptoms when they perceive a high climate for inclusion.

Similar content being viewed by others

In many countries, the number of ethnically diverse employees is growing due to skilled labor shortages, a global labor market, poverty in some developing countries, and armed conflicts in several areas around the world (Chand & Tung, 2014; ILO, 2018; OECD, 2012). If supported by managers and the organization, ethnic diversity at work can have many advantages such as increased creativity, innovation, and performance (Adamovic, 2018; Cooke & Saini, 2010, 2012; Ely & Thomas, 2001; Olsen et al., 2021). Despite these potential advantages, many organizations consider managing employees from ethnic minority backgrounds a challenge, because they lack understanding of these employees’ experiences in the workplace (Avery et al., 2008; Syed & Pio, 2010). Ethnic minorities are often exposed to prejudice, social exclusion, discrimination, and exploitation in the workplace (Adamovic, 2020a, 2022; Binggeli et al., 2013). Research evidence and media reports further suggest that ethnic minorities and migrants are at greater risk for depression and other mental health problems relative to their ethnic majority counterparts (Al-Maskari et al., 2011; Schachner et al., 2016). This depression negatively impacts ethnic minority employees’ productivity and quality of life (Alonso et al., 2004; Whiteford et al., 2013).

Prior research about ethnic minority employees often applied a social identity perspective (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) to identify the problems that these employees face (e.g., Coates & Carr, 2005; Dietz, Joshi, Esses, Hamilton, & Gabarrot, 2015; Li & Frenkel, 2017). According to social identity theory, individuals identify with their ethnic group and compare their group to others to reduce uncertainty around one’s ethnic identity and maintain a positive self-evaluation (Hogg & Terry, 2000; Tajfel & Turner, 1979). Ethnic identification leads individuals to favor their own ethnic group and could also lead to discrimination against other ethnic groups (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). While these previous studies reveal issues ethnic minority and migrant workers face such as discrimination and social exclusion, less is known about the ways managers and organizations can effectively improve these employees’ well-being (Guillaume et al., 2013; Guo & Al Ariss, 2015; Hutchings, 2003; Kingshott et al., 2018). We aim to extend prior research and provide clearer insights into how organizations can improve these employees’ well-being (Adamovic et al., 2020; Hajro, Gibson, & Pudelko, 2017; Romani et al., 2017).

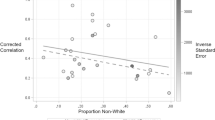

By integrating research on ethnic minorities at work with the job-demands-resources (JDR) model (Demerouti et al., 2001), we advance both theory development and organizational people management systems to ultimately improve ethnic minority workers’ well-being (Romani et al., 2017; Soltani et al., 2011). Based on prior research on ethnic minorities (Avery et al., 2008; Avery et al., 2018; McKay et al., 2008; Tufan & Wendt, 2020), we first argue that ethnic minority status has negative effects on perceived job demands, job self-efficacy, and depressive symptoms (Fig. 1). To buffer these negative effects, we consider climate for inclusion as a job resource and investigate its moderating role on the effects of ethnic minority status (Fig. 1).

Research model. Note. N = 771 employees in T1, 299 employees in T2. The T1 cases for which there is no T2 data were included in the path analysis. Values are standardized coefficients. ** p < .01, * p < .05, † p < .10. The dashed lines represent indirect relationships through job self-efficacy (Hypothesis 1) and job demands (Hypothesis 2)

Our research makes three key contributions. First, we examine an inclusive organizational climate as a key job resource for ethnic minority employees’ well-being. An inclusive climate indicates that an organization values equality and inclusion and thus should improve ethnic minorities’ well-being by weakening the dysfunctional effects of ethnic minority status on perceived job demands and job self-efficacy. Prior research on gender diversity suggests that higher climate for inclusion can improve well-being for gender minority employees in organizations (Miner-Rubino et al., 2009; Sliter et al., 2014). Similarly, we expect that climate for inclusion may also support ethnic minority employees. Furthermore, prior research on the JDR model indicates that a positive and inclusive workplace climate can reduce burnout (Crawford et al., 2010; Mauno et al., 2007; Odle-Dusseau et al., 2013).

Second, we analyze occupational (i.e., job self-efficacy and job demands) and personal well-being (i.e., depressive symptoms) as outcomes of ethnic minority status. Prior research on ethnicity at work overlooked personal wellbeing as outcome. Instead, prior research focused on outcomes such as discrimination, exclusion, performance, and job satisfaction (Avery et al., 2018), rather than personal well-being.

Third, to advance theory on ethnic minority employees and inform inclusive practices and people management systems (Binggeli et al., 2013; Guo & Al Ariss, 2015), we specify the mechanisms (i.e., job demands and job self-efficacy) and a moderator (i.e., climate for inclusion) of ethnic minority status effects. The few existing studies on climate for inclusion and well-being have only investigated the direct effects of climate for inclusion on employees’ well-being (Chrobot-Mason & Aramovich, 2013; Hardeman et al., 2016). By examining mechanisms and moderators, we can isolate what drives these negative outcomes to inform more effective and targeted organizational approaches to diversity. This approach is recommended in diversity research to guide managers and organizations (Guillaume et al., 2013; Hoever et al., 2012; Van Knippenberg et al., 2004).

Job-demands-resources model and research model

To develop the research model (Fig. 1), we apply the JDR model, which is a theoretical framework for predictors of stress and employee well-being in the workplace (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti et al., 2001). According to this model, employee well-being decreases because of job demands (i.e., psychological and organizational characteristics increase psychological stress and decrease cognitive resources; Nahrgang et al., 2011; van Woerkom et al., 2010), and improves when organizations provide job resources (i.e., aspects of a job or organization that enhance productivity, engagement, and well-being; Demerouti et al., 2001) that buffer the dysfunctional effects of job demands (Crawford et al., 2010; Dicke et al., 2018; Schaufeli & Bakker, 2004). Job demands include high workload, stress, conflict, and unclear work expectations (Crawford et al., 2010; Halbesleben, 2010), while job resources include autonomy, positive workplace climate, and social support (Crawford et al., 2010; Halbesleben, 2010). Given the negative consequences of job demands for ethnic minority employees in particular (Adamovic et al., 2020; Dietz, 2010), and the buffering effects of job resources, the JDR model offers a useful framework for workplace ethnicity research.

We tested two mechanisms that could explain the relationship between ethnicity and depressive symptoms. First, we selected perceived job demands, which captures an energetic process proposed by the JDR model (Huynh et al., 2012; Korunka et al., 2009) because they consume an employee’s energy and cognitive resources (Crawford et al., 2010). In the JDR model, job demands include high workload and stress, and higher job demands are related to reduced personal well-being (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti et al., 2001). Second, we selected job-self-efficacy, which is as a job resource that captures a cognitive process in the JDR model by measuring perceived capacity for facing challenges at work (Consiglio et al., 2013; Demerouti et al., 2016; Dicke et al., 2018). Due to social exclusion, ethnic minorities are likely to report lower job self-efficacy at work (for a study on refugees’ job self-efficacy, see Newman et al., 2018), which may negatively impact their well-being.

Finally, prior research on gender diversity suggests that diversity climate might be a crucial job resource for gender minority employees (Miner-Rubino et al., 2009; Sliter et al., 2014). We suggest that a greater diversity climate may support ethnic minority employees as it does gender minority employees. Specifically, an effective organizational diversity climate should demonstrate the organization values equity and inclusion and thus be a key job resource to enhance ethnic minority employees’ well-being.

Hypotheses development

Ethnicity and job self-efficacy

In addition to common workplace challenges and associated health risks that all employees face (Hovey & Magaña, 2000; Schachner et al., 2016), ethnic minority employees are more likely to experience isolation, incivility, harassment, and discrimination than ethnic majority employees (Adamovic, 2020a, 2022; Cortina, 2001; Kabat-Farr & Cortina, 2012). We apply the JDR model to these employees’ workplace experiences, considering job self-efficacy as a cognitive mechanism, and argue that ethnic minority status will reduce job self-efficacy. A focal concept in research on well-being is job self-efficacy (Consiglio et al., 2013; Demerouti et al., 2016; Dicke et al., 2018), defined as the belief that one can “successfully execute the behavior required to produce the outcomes” desired in the job (Bandura, 1977: 193). An understanding one’s current work requirements and the ability to effectively maintain or exceed current levels of job performance facilitates job self-efficacy (Adamovic et al., 2021); therefore, we propose that greater well-being and fewer depressive symptoms at the individual level is related to greater job self-efficacy (see also Demerouti et al., 2016; Dicke et al., 2018).

We expect ethnic minority employees to have lower job self-efficacy than ethnic majority employees. Self-efficacy is enhanced through vicarious experiences such as behavioral modeling of coworkers and managers (Bandura, 1977); however, due to bias against ethnic minorities, it is difficult for these employees to develop collaborative relationships with coworkers and managers (Avery, Richeson, Hebl, & Amady, 2009). Consequently, they are less likely to believe that they can share and learn from their coworkers and managers (McKay et al., 2009), reducing the opportunities to develop a sense of job self-efficacy.

Stereotypes depicting ethnic minorities as under-skilled and low in competence, and the associated employment discrimination, are prevalent in Western workplaces (Adamovic, 2022; Midtbøen, 2014; Thijssen et al., 2021; Yemane & Fernández-Reino, 2019). Mirroring these stereotypes, ethnic minority employees are afforded lower status relative to native workers (Li & Frenkel, 2017). Media, society, historical context, and government policies reinforce these status differences (Li & Frenkel, 2017). These stereotypes and prejudices, lead to lower self-efficacy and status for ethnic minorities and higher self-efficacy and status for majority group members (Ashforth & Mael, 1989).

Hypothesis 1:

Ethnic minority status reduces job self-efficacy.

Ethnic minority status and job demands

We also argue that ethnic minority status increases perceived job demands. Due to discriminatory experiences associated with their minority status, ethnic minority employees are likely to have fewer cognitive resources available to cope with their job and life (Bakker et al., 2003), increasing their job demands. Ethnic diversity often leads to workplace segregation, whereby ethnic minority employees are treated as outsiders and feel socially isolated in their organizations (Adamovic et al., 2020; D’Netto et al., 2014). They may face interpersonal conflicts with co-workers, supervisors, or clients due to their ethnic minority status, which are particularly detrimental for employees’ well-being (Hofhuis et al., 2012; Sojo et al., 2016; Zhang & Liao, 2015). Ethnic minority employees often report that they do not fit in the dominant culture and develop perceptions of social exclusion (Hakak et al., 2010). They also tend to suffer from a lack of professional and personal networks, cultural differences, and discrimination (Cooney-O'Donoghue et al., 2022; Hakak et al., 2010). Given ethnic minority employees’ social exclusion and the related cognitive demands (Ozier et al., 2019; Salvatore & Shelton, 2007), they may perceive their job demands as excessive and overwhelming.

Hypothesis 2:

Ethnic minority status increases perceived job demands.

The moderating role of climate for inclusion for ethnicity and job self-efficacy

We propose organizational climate for inclusion as a job resource that moderates the relationship between ethnicity and job self-efficacy. Climate for inclusion is defined in the literature as the extent to which the organization is perceived by the employees as an environment where individuals from all backgrounds, not just members of historically powerful groups, are (1) valued for who they are, (2) treated with respect, and (3) their uniqueness and differences are appreciated (Nishii, 2013). In the present work, we focus on individuals’ perceptions of climate for inclusion, defining climate for inclusion as cognitive evaluations or appraisals of the environment related to the support and value of diversity and inclusion (Kossek & Zonia, 1993).

We believe that an effective climate for inclusion is particularly important for ethnic minority employees’ job self-efficacy and job demands because it demonstrates that all employees are valued and respected, regardless of their ethnic backgrounds (Nishii, 2013). We posit that climate for inclusion is a job resource for ethnic minority employees that indicates a welcoming and respectful environment, weakening the dysfunctional effects of ethnic minority status on job self-efficacy. In a diversity-friendly environment, employees believe differences among employees are respected (Kossek et al., 2006). They believe they can benefit and learn from different perspectives and ways of thinking (Ely & Thomas, 2001; Nishii, 2013). In inclusive workplace environments, employees are valued for who they are as people (Mor Barak, 2000) and believe they can learn from each other (McKay et al., 2009). Such an open-minded environment characterized by welcoming diversity may increase ethnic minority employees’ job self-efficacy. In short, in an inclusive workplace, ethnic minority employees believe they can handle unforeseen situations more effectively and that they are well-prepared for their jobs (Schyns & von Collani, 2002).

Perceiving a climate for inclusion will likely increase job self-efficacy for ethnic minority employees, because this signals that their identities are valued. If the organization establishes an environment that supports diversity, ethnic minority employees will likely have fewer concerns about being mistreated because of their background (McKay et al., 2011), reducing negative effects of ethnic minority status on job self-efficacy. Further, a climate for inclusion is characterized by organizational support of diversity (Nishii, 2013). When the organization communicates that it cares for all employees and supports diversity through its policies, ethnic minority employees should feel more confident and that their careers will not be hindered by their ethnicity. In contrast, if managers and co-workers do not value diversity and different perspectives, ethnic minority employees are likely to lose confidence and find it difficult to share their ideas and knowledge.

Hypothesis 3:

Climate for inclusion moderates the relationship between ethnicity and job self-efficacy to mitigate the dysfunctional effects of ethnic minority status on job self-efficacy.

The moderating role of climate for inclusion for ethnicity and job demands

We further argue that a high climate for inclusion will buffer dysfunctional effects of ethnic minority status on perceived job demands. A high climate for inclusion means employees are treated with respect, regardless of their identities (Nishii, 2013). Thus, ethnic minority employees should perceive fewer job demands and a less stressful work environment when there is a high climate for inclusion. In general, a work environment characterized by open-mindedness and tolerance should energize ethnic minority employees and improve interpersonal interactions with co-workers (McKay et al., 2007; Sliter et al., 2014). In an inclusive climate, ethnic minority employees will have more cognitive resources available to cope with their job and life (Bakker et al., 2003), weakening the relationship between ethnic minority status and increased job demands.

Further, perceptions of a high climate for inclusion will increase the likelihood that ethnic minority employees are motivated to seek support (Guarino & Sojo, 2009) and to participate in knowledge exchange behaviors (Randel et al., 2016). Such behaviors should increase ethnic minority employees’ perceived control over their own jobs and weaken dysfunctional effects of ethnic minority status on perceived job demands.

In contrast, a low climate for inclusion should be particularly detrimental for the job demands of ethnic minority employees. For example, the inability to express one’s identity consumes cognitive energy (King & Cortina, 2010; Madera, 2010), which hinders workers’ capacity to deal with job demands. With a low climate for inclusion, ethnic minority employees may perceive interactions with managers and co-workers as more stressful and cognitively demanding (Hofhuis et al., 2012) and their resources to manage work tasks as insufficient.

Hypothesis 4:

Climate for inclusion moderates the relationship between ethnicity and job demands to mitigate the dysfunctional effects of ethnic minority status on job demands.

Job self-efficacy and depressive symptoms

We expect that job self-efficacy is a protective factor against depressive symptoms. For instance, low job self-efficacy increases feelings of helplessness (Madsen et al., 2017), which is a risk factor for depression (Burns & Seligman, 1991). Consequently, high job self-efficacy (i.e., believing in one’s ability to persist under job stress and capability to handle work) may reduce helplessness and other risk factors for depression. In contrast, low job self-efficacy may reduce employee’s belief in their capabilities to accomplish their work and meet expectations of their supervisor and colleagues, increasing psychological distress and the risk of depressive symptoms.

Moreover, prior research suggests that increased psychological resources like job self-efficacy have beneficial cross-over effects in one’s personal life (Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012). Feeling confident to conduct work effectively should increase employees’ belief that they are responsible for their well-being and lives (Hobfoll, 2002) (i.e., enhanced personal efficacy), which is protective against depressive symptoms (Blazer, 2002; Maciejewski et al., 2000).

Hypothesis 5:

Job self-efficacy reduces depressive symptoms.

Job demands and depressive symptoms

Next, we predict a positive relationship between perceived job demands and depressive symptoms. This prediction is aligned with the JDR model, which theorizes that job demands reduce employees’ well-being by consuming psychological resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti et al., 2001). Consequently, an employee has fewer remaining resources to cope with stressful events professionally and personally, increasing the likelihood of depressive symptoms.

If employees perceive high job demands such as a large workload, they are more likely to feel frustrated and helpless, increasing their likelihood of experiencing depressive symptoms. Job demands also consume cognitive energy, negatively impacting an employee’s well-being (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007, 2018). Our arguments follow prior research that finds perceived job demands lead to severe depression (for systematic reviews and meta-analysis, see Madsen, et al., 2017; Theorell, et al., 2015).

Hypothesis 6:

Job demands increase depressive symptoms.

Methods

Sample and procedure

We conducted a two-wave survey study with employees from five medium sized not-for-profit and local government organizations in Melbourne, Australia. In Australia, people with non-Anglo-Celtic backgrounds are considered ethnic minorities (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016; Syed & Pio, 2010). Historically, Anglo-Celtic Australians (i.e., ethnic majority) have opposed immigrants from Asian, Middle Eastern, and African backgrounds in Australia, in line with the White Australia Policy that existed until 1973 (Markus, 2015). The White Australia Policy prohibited immigration from non-European countries to Australia between 1901 and 1973. Today, ethnic minorities still experience ethnic discrimination in Australia (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2018).

Employees were recruited through two routes. First, senior leaders from each organization sent an email to employees explaining the research project and encouraging employees to participate in the study. Next, the research team directly emailed all employees of the organizations with an invitation to participate. There was a six-month interval between the two invitations and one reminder after each initial invitation. At Time 1, employees completed items measuring their perceptions of climate for inclusion, job demands, and job self-efficacy. They also reported on their depressive symptoms and provided demographic information. At Time 2, employees again reported on their depressive symptoms.

The described study collected data from 771 employees in Wave 1 (30% response rate), and 299 employees also completed the Wave 2 survey. Out of the 771 employees, 80% were female. This ratio reflects gender proportions within the organizations and industry sectors in Australia. Eighty-seven percent of the participants identified as heterosexual, 74% were born in Australia, and 80% were White. Regarding the ethnicity reported by the participants, 591 selected Caucasian/White, 70 selected Asian, 15 selected Latin-American/Hispanic, five selected African, three selected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, three selected Middle Eastern, 29 selected mixed race/biracial, and 56 selected “I prefer to refer myself as …” and provided an open-ended response. The most common response for mixed race/biracial was Caucasian-Asian (five responses) and Indian-White (three responses). The other responses were diverse and included, for example, Australian-Filipino, Australian-Italian, Greek-Australian, Indian-White, or Middle Eastern-White. The most common responses for “I prefer to refer myself as …” were Indian (six responses) and Chinese (four responses). The other responses were diverse and included Aboriginal, Anglo-Celtic, Bosnian, Egyptian, Greek, Creole, Israeli, Italian, Malaysian, Mauritian, Serbian, Turkish, and Vietnamese. Based on these responses, we considered 154 (20%) participants as ethnic minority employees. The average age of participants was 44 years. The mean tenure in the organization was 6.1 years. Based on ANZSCO's classification of occupations, the employees worked in following occupations: community and personal service workers (i.e., health workers; 31%), professionals (i.e., accountants, nurses, scientists, and lawyers; 29%), clerical and administrative workers (i.e., office managers, receptionists, bookkeepers, and legal clerks; 20%), managers (18%), sales workers (1%), technician and trades workers (1%), and labourers, machinery operators, and drivers (1%).

In Wave 2, 79% of the employees were female. Ninety-one percent of the participants identified as heterosexual, 73% were born in Australia, and 82% where White. The average age was 44.2 years, and the mean tenure was 6.8 years. In our sample, ethnic minority employees were not significantly different from their European Australian counterparts in job types. Regarding managerial roles, 12% of ethnic minorities were in managerial roles an 19% white Australian were in managerial roles. To compare the participants of Wave 1, who did not participate in Wave 2, with the sample of Wave 2, we conducted t-tests for depressive symptoms and all demographic variables. All t-tests were non-significant.

Ethnic minorities in Australia

Modern Australia is a nation founded on migration and in which migrants from different countries and with different ethnicities play an important role. However, for significant periods of Australian history, immigration policies have been highly selective and have mistreated treated people of non-White European backgrounds, as well as Indigenous peoples. For example, the ‘White Australia’ policy, an institutionalized opposition to non-Anglo migration, was adopted shortly after the federation of the Australian colonies in 1901 and only began to break down in the second-half the twentieth century with the intake of new waves of migrants from southern Europe and Asia.

Today, Australia is a multi-cultural society; more than one-quarter of its residents are born overseas and many new migrants with different ethnic backgrounds arrive each year (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2020). Beneath this multi-cultural surface, however, ethnic discrimination persists (Bahn, 2014; Dunn et al., 2016; Mahmud et al., 2014). Ethnic minorities report mistreatment based on their cultural and ethnic origin (Bahn, 2014). There have also been recent, high-profile employment scandals involving major Australian companies exploiting and under-paying their foreign workers.

Measures

Climate for inclusion was measured with seven items (e.g., “In this organisation, people’s differences are respected”) developed by Nishii (2013) to measure psychological climate for integration of differences in the workplace. The original instrument has three subscales: (a) Foundation of equitable employment practices, (b) Integration of differences, and (c) Inclusion in decision making. We selected the subscale Integration of differences because it directly captures individuals’ perceptions about the extent to which their organization is inclusive and respectful of different people (Nishii, 2013). Participants indicated to what extent their agreement with each item from 1 = ‘Strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘Strongly agree’ in this measure, as well as the job self-efficacy and job demands scales, described below. The Cronbach alpha of the scale was .94. The Composite Reliability (CR) was .94 and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) was .68.

Job self-efficacy was measured with seven items (e.g., “Thanks to my resourcefulness, I know how to handle unforeseen situations in my job”) developed by Schyns and Collani (2002). The Cronbach alpha of the scale was .89. CR was .90 and AVE was .55.

Perceived job demands were measured with five items (e.g., “My job requires all of my attention”) developed by Boyar et al. (2007). The Cronbach alpha of the scale was .94. CR was .94 and AVE was .75.

Depressive symptoms were measured with the relevant items from the General Health Questionnaire 28, which asks participants how their health has been over the past few weeks. This is a well-validated, commonly used measure of perceived health in workplace contexts (Makowska et al., 2002). The depression subdimension evaluates feelings of worthlessness and suicidal ideation with 7 items (e.g., “Felt that life isn't worth living?”) to which responses included ‘not at all’, ‘no more than usual’, ‘rather more than usual,’ and ‘much more than usual’. This measure was scored following the traditional method scoring (0–0-1–1) that allocates one point when the participant selected options indicating the presence of symptoms of depression (Goldberg et al., 1997). The Cronbach alpha of the scale was .92 in Time 1 and .80 in Time 2. CR was .92 and AVE was .62 in Time 2.

Finally, participants self-reported their ethnicities. We used six broad categories of ethnic groups (i.e., Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, African, Asian, Caucasian / White, Latin American/Hispanic, Middle Eastern) and included two text boxes for people to accurately indicate their ethnic identity/identities. Several respondents used the text box to provide more detailed information about their ethnic identification (e.g., Chinese, Greek, Indian, Italian, Malaysian, Sri Lankan, Vietnamese). For the data analysis, we considered these respondents as ethnic minority respondents, because they did not identify as the ethnic majority group (Caucasian/White). For example, a Greek migrant could indicate that she or he identifies as a White Caucasian or this respondent could use a text box to state Greek as ethnic identification. A Greek migrant would be considered as an ethnic minority employee in our sample, if she or he stated Greek as ethnic identification. Given that the largest ethnic group in Australia is White people from European ancestry (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016) and that this was also the largest ethnic group in our sample, we created a dichotomous variable with 0 = ethnic minority background and 1 = White.

Control. We controlled for depressive symptoms in Time 1, sex (0 = female, 1 = male), country of birth (0 = overseas, 1 = Australia), tenure, and organizational membership. By controlling for Time 1 depressive symptoms, we analyze if the variables in our model influence depressive symptoms in Time 2 beyond the effects of depressive symptoms in Time 1. We also controlled for gender because, due to the persistence of traditional gender stereotypes and roles, female employees could perceive more stress and mental health problems from expectations of work and home responsibilities (Drummond et al., 2016) or experiences of discrimination and harassment (Sojo et al., 2016). We controlled for country of birth as well because being born overseas could increase feelings of being an outsider, elevating stress (Avery et al., 2010). We controlled for tenure because there may be differences between new and tenured employees regarding well-being and job demands (Karatepe & Karatepe, 2009). Finally, as we collected the data in five different organizations, we also controlled for organizational membership. The inclusion of the control variables did not change our results or interpretations. The significance level and direction of the main effects did not change, supporting the robustness of our research model.

Analysis and results

Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations are presented in Table 1. In our sample, ethnicity and country of birth were correlated; individuals who identified as ethnic minorities were more likely to have been born outside Australia. Climate for inclusion was positively correlated with job self-efficacy and negatively correlated with job demands, depressive symptoms, and organizational tenure. Job self-efficacy was negatively correlated with job demands and depressive symptoms. Finally, job demands were positively correlated with gender (i.e., men), ethnicity (i.e., self-identifying as White), and depressive symptoms.

Hypotheses testing

The model fit of the measurement model was acceptable: χ2 (479) = 1341.49; CFI = .955; TLI = .951; RMSEA = .040; and SRMR = .049. A SRMR value less than .08 is considered a good fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Hu and Bentler further suggested that a RMSEA value smaller than .06 provides a very good fit. A CFI and TLI value higher than .9 means satisfactory fit (Awang, 2012; Hair et al., 2010). Hu and Bentler’s work (1999) suggests a higher cut-off value close to .95. Based on these common cut-off values, the model fit of the hypothesized measurement model was very good. We also compared this model to a model in which we combined all variables that were measured in T1 to one overall factor. However, the model fit got worse: χ2 (488) = 10,793.32; CFI = .465; TLI = .421; RMSEA = .137; and SRMR = .216. We therefore kept the initial measurement model.

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a path analysis using Mplus version 8. Mplus uses the delta method to calculate indirect effects. For mediation models for continuous observed variables, the delta method is equal to the Sobel test.Footnote 1 The use of Mplus allowed us to include the T1 cases for which there was no T2 data. We also tested an alternative model, in which we added a direct effect of ethnic minority status on depressive symptoms, but the effect was non-significant (ß = .05, p > .05). We therefore kept the hypothesized model, which is also the more parsimonious model.

In Hypothesis 1, we argued that ethnic minority status has dysfunctional effects on job self-efficacy. The results of our analysis (Fig. 1) indicate that the relationship is significant and that White employees (ethnic majority) report a higher job self-efficacy (ß = .45, p < .01; 95% confidence interval [CI]: .157, .743). Hypothesis 1 is supported. In contrast, Hypothesis 2 is not supported; the relationship between ethnicity and job demands is non-significant (ß = -.01, p > .05; 95% CI: -.301, .281).

Hypotheses 3 and 4 described the effects of the interaction between ethnicity and climate for inclusion. The results indicate that the moderation of climate for inclusion was significant regarding job self-efficacy (ß = -.58, p < .01; 95% CI: -.899, -.267, see Fig. 1). Hypothesis 3 was therefore supported. Figure 2 graphically represents the two-way interaction between ethnicity and climate for inclusion. As predicted, ethnic minorities’ job self-efficacy depended more on climate for inclusion (ß = .27, p < .01; 95% CI: .182, .360) than White employees’ job self-efficacy (ß = .09, p < .01; 95% CI: .039, .135). Further, when ethnic minorities perceived a high climate for inclusion, they reported a higher job self-efficacy and, in turn, fewer depressive symptoms (ß = -.06, p < .05; 95% CI: -.118, -.002) compared to ethnic majority employees (ß = -.02, p >.05; 95% CI: -.040, .001). However, the indirect effects were not significantly different from each other (p > .05).

The interaction of ethnicity and climate for inclusion was not significant regarding job demands (ß = .12, p = .45; 95% CI: -.215, .413), so Hypothesis 4 was not supported.

Hypothesis 5 predicted a negative relationship between job self-efficacy and depressive symptoms. This relationship was significant and negative (ß = -.09, p < .05; 95% CI: -.178, -.009), supporting our hypothesis. However, reduced job self-efficacy did not mediate the relationship between ethnic minority status and depressive symptoms (ß = -04., p > .05; 95% CI: -.089, .005).

Further, the relationship between job demands and depressive symptoms was positive and significant (ß = .13, p < .01; 95% CI: .043, .223), supporting Hypothesis 6. However, the indirect relationship between ethnic minority status and depressive symptoms through job demands was non-significant (ß = -.00, p > .05; 95% CI: -.040, .037).

Finally, the R-Squared values were significant for all endogenous variables of our model: job self-efficacy (R2 = .08, p < .01), job demands (R2 = .10, p < .01), and depressive symptoms (R2 = .50, p < .01).

Discussion

Summary and discussion of results

Drawing on ethnicity research (Avery et al., 2008, 2018; McKay et al., 2008) and the JDR model (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007; Demerouti et al., 2001), we developed and tested a research model explaining the influence of ethnic minority status on well-being in terms of job demands, job self-efficacy, and depressive symptoms. In this two-wave survey study, ethnic minority employees reported lower job self-efficacy than ethnic majority employees. When they perceived a high climate for inclusion however, ethnic minority employees reported higher job self-efficacy and fewer depressive symptoms.

Consistent with our proposed theoretical model, our data suggest that climate for inclusion is a job resource for ethnic minority employees. They reported lower depressive symptoms, roughly six months later, through increased job self-efficacy, when climate for inclusion was high. Our findings are considered robust because they were consistent whether or not we controlled for depressive symptoms at time 1, gender, country of birth, tenure and organizational membership. This work makes three main contributions to the literature on ethnic minority employees and climate for inclusion.

First, we showed that employees from ethnic minority backgrounds benefit more from a high climate for inclusion regarding their job self-efficacy than White employees in Australia. In line with prior research (Madera et al., 2016; McKay et al., 2007), our theoretical and empirical work suggests that a respectful and welcoming work environment increases ethnic minorities’ confidence to address their needs related to inclusion. Such an inclusive climate shows ethnic minority employees that contributions and ideas from all employees, regardless of ethnic background, are valued. This supportive work environment helps ethnic minorities develop job self-efficacy (see also for refugee employees: Newman et al., 2018).

Contrary to our expectations, ethnic minority employees did not report higher job demands and climate for inclusion did not moderate the relationship of ethnicity with job demands. Climate for inclusion was beneficial regarding job demands for all employees, independent of their ethnic backgrounds. It seems that an inclusive climate satisfies the needs of all employees, creating a less stressful environment. Another reason for the non-significant interaction effects might be that we focused on the integration of differences sub-dimension of Nishii's diversity climate construct (Nishii, 2013) to measure climate for inclusion. However, the other two sub-dimensions of diversity climate (i.e., equitable employment practices and decision-making participation) may be more protective against job demands. Indeed, organizational justice research has shown that having a voice reduces stress (Greenberg, 2004).

Second, we showed that ethnic minority status and climate for inclusion impact employee occupational outcomes (i.e., job self-efficacy and job demands) and personal (i.e., lower depressive symptoms) well-being. Prior research has focused primarily on job performance and job satisfaction as outcomes of ethnic minority status (Avery et al., 2018). We demonstrate that ethnic minority status is also important to employees’ self-efficacy and health (Barak & Travis, 2010), depending on the employee’s perceptions of the organization’s climate for inclusion.

Finally, we focused on the role of organizations and managers to improve the well-being of ethnic minority employees. Prior research was often guided by social identity theory and focused on identifying the problems and challenges that ethnic minorities and migrants face in the workplace (Guillaume et al., 2013, 2014; Hakak & Al Ariss, 2013; Stahl et al., 2016). We take a more proactive approach, going beyond the analysis of problems and challenges (Adamovic et al., 2020; Hajro et al, 2017) to demonstrate that organizations can improve employees’ well-being by fostering a high climate for inclusion. We confirmed that a cognitive mechanism (i.e., job self-efficacy- evaluation of own competencies at work) and an energetic mechanism (i.e., job demands- perceptions of the job as taxing) explain the beneficial moderating effects of climate for inclusion on well-being for ethnic minorities. Employers can support their employees by communicating that their ideas and needs are respected and that they can reveal their authentic identities in the workplace. Such a climate will likely increase ethnic minority employees’ beliefs in their skills and knowledge directly and indirectly by providing opportunities to develop and use skills and networks. As a result, they may feel more in control of their jobs and lives, reducing depressive symptoms.

Strengths, research limitations, and avenues for future research

Our study has several strengths including analyzing how an inclusive climate can improve ethnic minority employees’ personal well-being, investigating the mechanisms that improve experiences in diverse organizations, and collecting two-waves of data from working adults across five not-for-profit and local government organizations. Despite these strengths, our study has several limitations that present interesting avenues for future research.

Most ethnic minority employees listed Asian as their ethnic background. This is not surprising because people of Chinese and Southeast Asian descent are the most common ethnic minority groups in Australia (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2016). However, future research should include additional ethnicities to compare and generalize our findings and analyze whether differences exist between different ethnic minority groups (McKay et al., 2008).

As we have conducted our study in Australia, future research in other countries is needed to generalize our findings as well. We believe that our findings can be generalized to other Western countries with a high share of ethnic minorities from Asian backgrounds such as New Zealand, Canada, and the USA. However, future research is needed to test our research model in Asian, African, European, and South American countries, which have different ethnic minorities and migration histories.

In this article, we applied a JDR lens and used the JDR model to design our study and to explain our hypotheses. To help researchers and practitioners better understand the drivers of employee well-being, future research could integrate the JDR model with the conversion of resources (COR) framework (Hobfoll, 2001, 2011). The COR framework is another important framework to analyze well-being issues of employees. This framework argues that individuals suffer from mental health issues like stress or emotional exhaustion when they lose resources or when their resources are threatened. The COR framework considers how context (environmental, social, and cultural factors) and life circumstances impact well-being.

Further, employees evaluated most variables in our research model. Future research could include supervisor evaluations or clinical health measures to reduce common method variance issues (Podsakoff et al., 2003). However, address some of these common issues by taking two measurements six months apart and investigating variables like self-efficacy and job demands, which require employees to self-report. Further, we controlled for depressive symptoms in Time 1. Additionally, as our predictor was ethnicity, a demographic attribute, there should be fewer issues related to common method variance and causality in our tests of moderation. We also report a significant interaction effect, indicating that our study is unlikely to be influenced by common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Similarly, the measure of depressive symptoms we used, even if self-reported, has been extensively validated as a predictor of severe depression in the general population across multiple countries.

Finally, due to our two-wave survey design and a six-month time lag, the number of responses dropped from 771 to 299 employees. This also means that the number of ethnic minority employees had dropped from 154 employees in Time 1 to 54 employees in Time 2. However, our main finding, which is the significant interaction effect between ethnicity and climate for inclusion is based on the use of 154 ethnic minority employees. Mplus allowed to use all respondents in Time 1 to test our research model, so that we could include all 154 ethnic minority employees for Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 8. In contrast, we had 54 ethnic minority employees to test the effects of job self-efficacy and job demands on depressive symptoms (Hypotheses 5 and 6), but Hypotheses 5 and 6 refer to all employees and not only to ethnic minority employees. Nevertheless, future research could sample a larger number of employees in Time 1 to account for attrition.

Practical implications

In Australia and most Western countries, ethnic minorities are a significant and increasing part of today’s workforce. Organizations strive to create work environments that enhance job self-efficacy and reduce job demands for employees from all ethnic backgrounds, particularly those who are in the minority. Our research offers insight into integrating ethnic minorities in the workplace. While prior research has already identified educational level of migrants, and economic recession as in the integration of ethnic minorities and migrant workers in society and workplaces (Aydemir & Skuterud, 2005; Bloom et al., 1995; Fang et al., 2013; Frenette & Morissette, 2005; Grant, 1999; Guo & Al Ariss, 2015; Moore & Pacey, 2003; Reitz, 2001), we demonstrate that climate for inclusion is particularly important for the well-being of ethnic minority employees.

The present study indicates that a climate for inclusion is particularly impactful for ethnic minority employees’ job self-efficacy. Organizations should therefore support ethnic minority employees with resources assistance with language and cultural values and norms (Bhaskar-Shrinivas et al., 2005; Harrison et al., 2004). Intercultural and respectful relations training for all employees might be effective interventions, starting with senior leaders, given they are expected to set the tone of appropriate behaviors at work and sometimes drive the exclusion of employees within the organization (Hauge et al., 2011).

Importantly, true equity might require moving beyond intercultural relations training for senior leaders and other employees. To create a climate for inclusion, organizations and managers could implement participative decision-making processes, allowing different employees to express their opinions and ideas (Adamovic et al., 2020; Borak, 1999). Organizational leaders need to avoid intergroup biases and treat employees with equity in allocation of opportunities (Shore et al., 2011). A climate for inclusion involves fair human resource management practices related to recruitment and selection, allocation of important projects and job opportunities, training and development, performance appraisal, and compensation (D’Netto et al., 2014). In general, a whole-of-organization approach is recommended to address matters of inclusion and workplace equity, rather than isolated actions (Roberts & Sojo, 2019).

Finally, understanding how employees perceive and evaluate their work environments, as well as how social psychological processes function within the context of diversity, will help managers utilize the potential of diversity regarding creativity and innovation (Adamovic, 2020b; Guillaume et al., 2014). Considering the protective role that climate for inclusion played in the current study, managers must understand the societal-, organizational-, team- and individual-level factors that drive positive attitudes towards workplace inclusion and how to enhance them (Anglin et al., 2019; Guillaume et al., 2013).

In conclusion, we developed and tested a research model of the organizational environment’s role in creating an inclusive workplace that values diversity, particularly for ethnic minority employees whose self-efficacy might be hindered by their treatment and status in organizations. We show that occupational and personal well-being of ethnic minorities can be improved by focusing on climate for inclusion.

Notes

Based on a reviewer’s comment, we also used bootstrapping. The results remained very similar. The direction and significance level of the main findings did not change.

References

Adamovic, M. (2018). An employee-focused human resource management perspective for the management of global virtual teams. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29(14), 2159–2187. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1323227

Adamovic, M., Gahan, P., Olsen, J., Harley, B., Healy, J., & Theilacker, M. (2020). Does procedural justice climate increase the identification and engagement of migrant workers? A group engagement model perspective. Personnel Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-11-2019-0617

Adamovic, M. (2020a). Analyzing discrimination in recruitment: A guide and best practices for resume studies. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 28(4), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12298

Adamovic, M. (2020b). Taking a deeper look inside autonomous and interdependent teams: why, how, and when does informational dissimilarity elicit dysfunctional versus beneficial effects. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(5), 650–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1763957

Adamovic, M., Gahan, P., Olsen, J., Gulyas, A., Shallcross, D., Mendoza, A. (2021). Exploring the adoption of virtual work: the role of virtual work self-efficacy and virtual work climate. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2021.1913623

Adamovic, M. (2022). When ethnic discrimination in recruitment is likely to occur and how to reduce it: Applying a contingency perspective to review resume studies. Human Resource Management Review, 32(2), 100832. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2021.100832

Al-Maskari, F., Shah, S. M., Al-Sharhan, R., Al-Haj, E., Al-Kaabi, K., Khonji, D., & Bernsen, R. M. (2011). Prevalence of depression and suicidal behaviors among male migrant workers in United Arab Emirates. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 13(6), 1027–32.

Alonso, J., Angermeyer, M. C., Bernert, S., Bruffaerts, R., … ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators, European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) Project (2004). Disability and quality of life impact of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00329.x

Anglin, J., Sojo, V., Ashford, L., Newman, A., & Marty, A. (2019). Predicting employee attitudes to workplace diversity from personality, values, and cognitive ability. Journal of Research in Personality, 83, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103865

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. (1989). Social identity theory and the organization. Academy of management review, 14(1), 20–39.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2016). Cultural Diversity in Australia. Retrieved from https://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/by%20Subject/2071.0~2016~Main%20Features~Cultural%20Diversity%20Data%20Summary~30. Accessed 10 June 2022.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2020). Migration, Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/migration-australia/latest-release. Accessed 10 June 2022.

Australian Human Rights Commission (2018). Anti-Racism in 2018 and Beyond. Sydney, Australia, AHRC. Retrieved from, https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/race-discrimination/publications/anti-racism-2018-and-beyond-2018. Accessed 10 June 2022.

Avery, D. R., McKay, P. F., & Wilson, D. C. (2008). What are the odds? How demographic similarity affects the prevalence of perceived employment discrimination. Journal of Applied Psychology, 235–249.

Avery, D. R., Richeson, J. A., Hebl, M. R., & Ambady, N. (2009). It does not have to be uncomfortable: The role of behavioral scripts in Black–White interracial interactions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1382.

Avery, D. R., Tonidandel, S., Volpone, S. D., & Raghuram, A. (2010). Overworked in America? How work hours, immigrant status, and interpersonal justice affect perceived work overload. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(2), 133–147.

Avery, D. R., Volpone, S. D., & Holmes, O. I. V. (2018). Racial discrimination in organizations. In A. J. Colella & E. B. King (Eds.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of workplace discrimination (pp. 89–109). Oxford University Press.

Awang, Z. (2012). Research methodology and data analysis second edition. UiTM Press.

Aydemir, A., & Skuterud, M. (2005). Explaining the deteriorating entry earnings of Canada’s immigration cohorts, 1966–2000. Canadian Journal of Economics, 38, 641–671.

Bahn, S. (2014). Migrant workers on temporary 457 visas working in Australia: Implications for human resource management. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 52(1), 77–92.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2007). The job demands-resources model, State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328.

Barak, M. E. M. (1999). Beyond affirmative action: Toward a model of diversity and organizational inclusion. Administration in Social Work, 23(3–4), 47–68.

Barak, M. E. M., & Travis, D. J. (2010). Diversity and organizational performance. Human services as complex organizations. Los Angeles ua, 341–378.

Bakker, A. B., Demerouti, E., Taris, T. W., Schaufeli, W. B., & Schreurs, P. J. G. (2003). A multigroup analysis of the job demands-resources model in four home care organizations. International Journal of Stress Management, 10, 16–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.10.1.16

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2018). Multiple levels in job demands-resources theory: Implications for employee well-being and performance. Handbook of well-being.

Bhaskar-Shrinivas, P., Harrison, D. A., Shaffer, M. A., & Luk, D. M. (2005). Input-based and time-based models of international adjustment, Meta-analytic evidence and theoretical extensions. Academy of Management Journal, 48(2), 257–281.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy, Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215.

Binggeli, S., Dietz, J., & Krings, F. (2013). Immigrants, A forgotten minority. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 6, 107–113.

Blazer, D. G. (2002). Self-efficacy and depression in late life: A primary prevention proposal. Aging & Mental Health, 6(4), 315–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360786021000006938

Bloom, D. E., Grenier, G., & Gunderson, M. (1995). The changing labor market position of Canadian immigrants. Canadian Journal of Economics, 28, 987–1005.

Boyar, S. L., Carr, J. C., Mosley, D. C., Jr., & Carson, C. M. (2007). The development and validation of scores on perceived work and family demand scales. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 67(1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164406288173

Burns, M. O., & Seligman, M. E., et al. (1991). Explanatory style, helplessness, and depression. In C. R. Snyder & D. R. Forsyth (Eds.), Handbook of social and clinical psychology: The health perspective (pp. 267–284). Pergamon.

Chand, M., & Tung, R. L. (2014). Bicultural identity and economic engagement: An exploratory study of the Indian diaspora in North America. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 31, 763–788.

Van Knippenberg, D., De Dreu, C. K., & Homan, A. C. (2004). Work group diversity and group performance, An integrative model and research agenda. Journal of Applied Psychology, 1008–1022.

Coates, K., & Carr, S. C. (2005). Skilled immigrants and selection bias: A theory-based field study from New Zealand. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 577–599.

Chrobot-Mason, D., & Aramovich, N. P. (2013). The psychological benefits of creating an affirming climate for workplace diversity. Group & Organization Management, 38(6), 659–689.

Consiglio, C., Borgogni, L., Alessandri, G., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2013). Does self-efficacy matter for burnout and sickness absenteeism? The mediating role of demands and resources at the individual and team levels. Work & Stress, 27(1), 22–42.

Cooke, F. L., & Saini, D. S. (2010). Diversity management in India: A study of organizations in different ownership forms and industrial sectors. Human Resource Management: Published in Cooperation with the School of Business Administration, the University of Michigan and in Alliance with the Society of Human Resources Management, 49(3), 477–500.

Cooke, F. L., & Saini, D. S. (2012). Managing diversity in Chinese and Indian organizations: A qualitative study. Journal of Chinese Human Resources Management.

Cooney‐O’Donoghue, D., Adamovic, M., & Sojo, V. (2022). Exploring the impacts of the COVID‐19 crisis for the employment prospects of refugees and people seeking asylum in Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 57(1), 88–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.177

Cortina, L. M. (2001). Assessing sexual harassment among Latinas, Development of an instrument. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7, 164–181.

Crawford, E. R., LePine, J. A., & Rich, B. L. (2010). Linking job demands and resources to employee engagement and burnout, a theoretical extension and meta-analytic test. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95(5), 834–848.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands- resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 499–512.

Demerouti, E., Sanz-Vergel, A. I., Petrou, P., & van den Heuvel, M. (2016). How work-self conflict/facilitation influences exhaustion and task performance, a three-wave study on the role of personal resources. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 21(4), 391–402.

Dicke, T., Stebner, F., Linninger, C., Kunter, M., & Leutner, D. (2018). A longitudinal study of teachers’ occupational well-being, applying the job demands-resources model. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 23(2), 262–277.

Dietz, J. (2010). Introduction to the special issue on employment discrimination against immigrants. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25, 104–112.

Dietz, J., Joshi, C., Esses, V. M., Hamilton, L. K., & Gabarrot, F. (2015). The skill paradox: Explaining and reducing employment discrimination against skilled immigrants. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26, 1318–1334.

D’Netto, B., Shen, J., Chelliah, J., & Monga, M. (2014). Human resource diversity management practices in the Australian manufacturing sector. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 25(9), 1243–1266.

Dunn, K., Paradies, Y., Atie, M. R., & Priest, D. N. (2016). The morbid effects associated with racism experienced by immigrants: findings from Australia. In A. M. N. Renzaho (Ed.), Globalisation, Migration and Health (pp. 509–531). https://doi.org/10.1142/9781783268894_0015

Drummond, S., O’Driscoll, M. P., Brough, P., Kalliath, T., Siu, O.-L., Timms, C., … Lo, D. (2016). The Relationship of social support with well-being outcomes via work-family conflict, Moderating effects of gender, dependents and nationality. Human Relations, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716662696

Ely, R. J., & Thomas, D. A. (2001). Cultural diversity at work, The effects of diversity perspectives on work group processes and outcomes. Administrative Science Quarterly, 229–273.

Fang, T., Samnani, A.-K., Novicevic, M., & Bing, M. (2013). Liability-of-foreignness effects on job success of immigrant job seekers. Journal of World Business, 48, 98–109.

Frenette, M., & Morissette, R. (2005). Will they ever converge? Earnings of immigrant and Canadian-born workers over the last two decades. International Migration Review, 39, 228–258.

Goldberg, D. P., Gater, R., Sartorius, N., Ustun, T. B., Pinccinelli, M., Guruje, O., & Rutter, C. (1997). The validity of two versions of the GHQ in the WHO study of mental illness in general health care. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 191–197. S0033291796004242. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291796004242.

Grant, M. (1999). Evidence of new immigrant assimilation in Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics, 32, 930–955.

Greenberg, J. (2004). Stress fairness to fare no stress, managing workplace stress by promoting organizational justice. Organizational Dynamics, 33(4), 352–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2004.09.003

Guarino, L., & Sojo, V. (2009). Adaptation and validation of the ITQ (Interpersonal Trust Questionnaire). A new measure of social support. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 27(1), 192–206.

Guillaume, Y. R. F., Dawson, J. F., Priola, V., Sacramento, C. A., & Woods, S. A. (2013). Getting diversity at work to work: What we know and what we still don’t know. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(2), 123–141.

Guillaume, Y. R. F., Dawson, J. F., Priola, V., Sacramento, C. A., Woods, S. A., Higson, H. E., Budhwar, P. S., & West, M. A. (2014). Managing diversity in organizations, An integrative model and agenda for future research. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 23(5), 783–802.

Guo, C., & Al Ariss, A. (2015). Human resource management of international migrants, current theories and future research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 26, 1287–1297.

Hajro, A., Gibson, C., & Pudelko, M. (2017). Knowledge exchange processes in multicultural teams: linking organizational diversity climates to teams’ effectiveness. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1), 345–372.

Hair, J., Black, W., Babin, B., and Anderson, R. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.): Prentice-Hall, Inc. Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA).

Hakak, L., & Al Ariss, A. (2013). Vulnerable work and international migrants, A relational human resource management perspective. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24, 4116–4131.

Hakak, L. T., Holzinger, I., & Zikic, J. (2010). Barriers and paths to success: Latin American MBAs' views of employment in Canada. Journal of Managerial Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011019366

Halbesleben, J. R. B. (2010). A meta-analysis of work engagement, relationships with burnout, demands, resources, and consequences. In A. B. Bakker, & M. P. Leiter (Eds.), Work engagement, a handbook of essential theory and research. Taylor & Francis Group, New York.

Hardeman, R. R., Przedworski, J. M., Burke, S., Burgess, D. J., Perry, S., Phelan, S., van Ryn, M., et al. (2016). Association between perceived medical school diversity climate and change in depressive symptoms among medical students: a report from the medical student CHANGE study. Journal of the national medical association, 108(4), 225–235.

Harrison, D. A., Shaffer, M. A., & Bhaskar-Shrinivas, P. (2004). Going places, Roads more and less traveled in research on expatriate experiences. In J. J. Martocchio (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resources management (pp. 199–247). Boston.

Hauge, L. J., Elnarsen, S., Knardahl, S., Lau, B., Notelaers, G., & Skogstad, A. (2011). Leadership and role stressors as departmental level predictors of workplace bullying. International Journal of Stress Management, 18(4), 305–323.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2001). The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: Advancing conservation of resources theory. Applied Psychology, 50(3), 337–421.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2002). Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology, 6(4), 307–324.

Hobfoll, S. E. (2011). Conservation of resources theory: Its implication for stress, health, and resilience.

Hoever, I. J., van Knippenberg, D., van Ginkel, W. P., & Barkema, H. G. (2012). Fostering team creativity, Perspective taking as key to unlocking diversity’s potential. Journal of Applied Psychology, 982–996.

Hofhuis, J., Van der Zee, K. I., & Otten, S. (2012). Social identity patterns in culturally diverse organizations, The role of diversity climate. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(4), 964–989. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00848.x

Hogg, M. A., & Terry, D. J. (2000). Social identity and self-categorization processes in organizational contexts. Academy of Management Review, 25(1): 121–140.

Hovey, J. D., & Magaña, C. (2000). Acculturative stress, anxiety, and depression among Mexican immigrant farmworkers in the Midwest United States. Journal of Immigrant Health, 2(3), 119–131.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural equation modeling: a multidisciplinary journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Hutchings, K. (2003). Cross-cultural preparation of Australian expatriates in organisations in China: The need for greater attention to training. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 20, 375–396.

Huynh, J. Y., Xanthopoulou, D., & Winefield, A. H. (2012). The Job Demands-Resources Model in emergency service volunteers, Examining the mediating roles of exhaustion, work engagement and organizational connectedness. Work & Stress, 28(3), 305–322.

ILO. 2018. ILO Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers. Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_652001.pdf. Accessed 14 April 2022.

Kabat-Farr, D. & Cortina, L. M. (2012). Selective incivility, Gender, race, and the discriminatory workplace. In S. Fox & T. Lituchy (Eds.), Gender and the Dysfunctional Workplace. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Karatepe, O. M., & Karatepe, T. (2009). Role stress, emotional exhaustion, and turnover intentions, does organizational tenure in hotels matter? Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 9(1), 1–16.

King, E. B., & Cortina, J. M. (2010). The social and economic imperative of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and transgendered supportive organizational policies. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 3, 69–78.

Kingshott, R., Sharma, P., Hosie, P., & Davcik, N. (2018). Interactive impact of ethnic distance and cultural familiarity on the perceived effects of free trade agreements. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 36, 135–160.

Korunka, C., Kubicek, B., Schaufeli, W. B., & Hoonakker, P. (2009). Work engagement and burnout, testing the robustness of the Job Demands-Resources model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(3), 243–255.

Kossek, E., & Zonia, S. (1993). Assessing diversity climate, A field study of reactions to employer efforts to promote diversity. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14, 61–81.

Kossek, E. E., Lobel, S. A., & Brown, J. (2006). Human resource strategies to manage workforce diversity. Handbook of workplace diversity, 53–74.

Li, X., & Frenkel, S. (2017). Where hukou status matters: analyzing the linkage between supervisor perceptions of HR practices and employee work engagement, International Journal of Human Resource Management, 28, 2375–2402.

Maciejewski, P., Prigerson, H., & Mazure, C. (2000). Self-efficacy as a mediator between stressful life events and depressive symptoms: Differences based on history of prior depression. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176(4), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.176.4.373

Madera, J., Dawson, M., & Guchait, P. (2016). Psychological diversity climate, justice, racioethnic minority status and job satisfaction. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(11), 2514–2532.

Madera, J. M. (2010). The cognitive effects of hiding one’s homosexuality in the workplace. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Perspectives on Science and Practice, 3, 86–89.

Madsen, I., Nyberg, S., Magnusson Hanson, L., Ferrie, J., Ahola, K., Alfredsson, L., Kivimäki, M. (2017). Job strain as a risk factor for clinical depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis with additional individual participant data. Psychological Medicine, 47, 1342–1356. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171600355X

Mahmud, S., Alam, Q., & Härtel, C. (2014). Mismatches in skills and attributes of immigrants and problems with workplace integration: A study of IT and engineering professionals in A ustralia. Human Resource Management Journal, 24(3), 339–354.

Makowska, Z., Merecz, D., & Kolasa, W. (2002). The validity of general health questionnaires, GHQ-12 and GHQ-28, in mental health studies of working people. International Journal of Occupational Medicine and Environmental Health, 15(4), 353–362.

Markus, A. (2015). Australian opinion on issues of race, a broad reading of opinion polls, 1943 – 2014. Australian Human Rights Commission (Ed.), Perspectives on the Racial Discrimination Act. 40 Years of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (CTH) Conference (pp. 16–31). Sydney, NSW, Australian Human Rights Commission. Retrieved from, https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/race-discrimination/publications/perspectives-racial-discrimination-act-papers-40-years

Mauno, S., Kinnunen, U., & Ruokolainen, M. (2007). Exploring work- and organization-based resources as moderators between work–family conflict, well-being, and job attitudes. Work & Stress, 20(3), 210–233.

McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., Liao, H., & Morris, M. A. (2011). Does diversity climate lead to customer satisfaction? It depends on the service climate and business unit demography. Organization Science, 22(3), 788–803.

McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., & Morris, M. A. (2008). Mean racial-ethnic differences in employee sales performance, the moderating role of diversity climate. Personnel Psychology, 61, 349–374.

McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., & Morris, M. A. (2009). A tale of two climates, Diversity climate from subordinates’ and managers’ perspectives and their role in store unit sales performance. Personnel Psychology, 62, 767–791.

McKay, P. F., Avery, D. R., Tonidandel, S., Morris, M. A., Hernandez, M., & Hebl, M. R. (2007). Racial differences in employee retention, Are diversity climate perceptions the key? Personnel Psychology, 60, 35–62.

Midtbøen, A. H. (2014). The invisible second generation? Statistical discrimination and immigrant stereotypes in employment processes in Norway. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 40, 1657–1675. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2013.847784

Miner-Rubino, K., Settles, I., & Stewart, A. (2009). More than numbers, Individual and contextual factors in how gender diversity affects women’s well-being. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01524.x

Moore, E. G., & Pacey, M. A. (2003). Changing income inequality and immigration in Canada, 1980–1995. Canadian Public Policy/analyse De Politiques, 29, 33–52.

Mor Barak, M. E. (2000). Beyond affirmative action, Toward a model of diversity and organizational inclusion. Administration in Social Work, 47–68.

Nahrgang, J. D., Morgeson, F. P., & Hofmann, D. A. (2011). Safety at work, a meta-analytic investigation of the link between job demands, job resources, burnout, engagement, and safety outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(1), 71–94.

Newman, A., Nielsen, I., Smyth, R., Hirst, G., & Kennedy, S. (2018). The effects of diversity climate on the work attitudes of refugee employees, The mediating role of psychological capital and moderating role of ethnic identity. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 105, 147–158.

Nishii, L. H. (2013). The benefits of climate for inclusion for gender-diverse groups. Academy of Management Journal, 56(6), 1754–1774.

Odle-Dusseau, H. N., Herleman, H. A., Britt, T. W., Moore, D. D., & Castro, C. A. (2013). Family-supportive work environments and psychological strain, a longitudinal test of two theories. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(1), 27–36.

OECD. (2012). Key statistics on migration in OECD countries. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/document/4/0,3746,en_2649_37415_48326878_1_1_1_37415,00.html. Accessed 10 October 2018.

Olsen, J. E., Gahan, P., Adamovic, M., Choi, D., Harley, B., Healy, J., & Theilacker, M. (2021). When the minority rules: Leveraging difference while facilitating congruence for cultural minority senior leaders. Journal of International Management, 100886.

Ozier, E. M., Taylor, V. J., & Murphy, M. C. (2019). The cognitive effects of experiencing and observing subtle racial discrimination. Journal of Social Issues, 75, 1087–1115. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12349

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2012). Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it. Annual review of psychology, 63(1), 539–569.

Randel, A., Dean, M., Ehrhart, K., Chung, B., & Shore, L. (2016). Leader inclusiveness, psychological diversity climate, and helping behaviors. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 31(1), 216–234.

Reitz, J. G. (2001). Immigrant skill utilization in the Canadian labor market, Implications of human capital research. Journal of International Migration and Integration, 2, 347–378.

Roberts, V. L., & Sojo, V. E. (2019). To strive is human, to abuse malign: discrimination and non-accidental violence of professional athletes without employee-style statutory protection. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 54, 253–254. bjsports-2019–100693. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2019-100693

Romani, L., Holck, L., Holgersson, C., & Muhr, S. L. (2017), “Diversity management and the Scandinavian model, Illustrations from Denmark and Sweden.” In: M. Özbilgin & J. F. Chanlat (eds.), Management and Diversity. Perspectives from National Context, Vol. 3. London, Emerald, 261–280.

Salvatore, J., & Shelton, J. N. (2007). Cognitive costs of exposure to racial prejudice. Psychological Science, 18, 810–815. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01984.x

Schachner, M. K., Noack, P., Van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Eckstein, K. (2016). Cultural diversity climate and psychological adjustment at school-equality and inclusion versus cultural pluralism. Child Development, 87, 1175–1191.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25, 293–315.

Schyns, B., & von Collani, G. (2002). A new occupational self-efficacy scale and its relation to personality constructs and organizational variables. European Journal of Work & Organizational Psychology, 11(2), 219–241.

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Ehrhart, K. H., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups, a review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1262–1289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310385943

Sliter, M., Boyd, E., Sinclair, R., Cheung, J., & McFadden, A. (2014). Inching toward inclusiveness, Diversity climate, interpersonal conflict, and well-being in women nurses. Sex Roles, 71, 43–54.

Sojo, V., Wood, R., & Genat, A. (2016). Harmful workplace experiences and women’s occupational well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(1), 10–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684315599346

Soltani, E., Syed, J., Liao, Y.-Y., & Shahi-Sough, N. (2011). Tackling one-sidedness in equality and diversity research: Characteristics of the current dominant approach to managing diverse workgroups in Iran. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29, 9–37.

Stahl, G., Tung, R. L., Kostova, T., & Zellmer-Bruhn, M. (2016). Widening the lens, Rethinking distance, diversity, and foreignness in international business research through positive organizational scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 1–10.

Syed, J., & Pio, E. (2010). Veiled diversity? Workplace experiences of Muslim women in Australia. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 27, 115–137.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin, & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–37). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

ten Brummelhuis, L. L., & Bakker, A. B. (2012). A resource perspective on the work-home interface, The work-home resources model. The American Psychologist, 67, 545–556.

Theorell, T., Hammarström, A., Aronsson, G., Träskman Bendz, L., Grape, T., Hogstedt, C., Marteinsdottir, I., Skoog, I., & Hall, C. (2015). A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health, 1, 738. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1954-4

Thijssen, L., Coenders, M., & Lancee, B. (2021). Is there evidence for statistical discrimination against ethnic minorities in hiring? Evidence from a cross-national field experiment. Social Science Research, 93, 102482. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2020.102482

Tufan, P., & Wendt, H. (2020). Organizational identification as a mediator for the effects of psychological contract breaches on organizational citizenship behavior: Insights from the perspective of ethnic minority employees. European Management Journal, 38(1), 179–190.

van Woerkom, M., Bakker, A. B., & Nishii, L. H. (2010). Accumulative job demands and support for strength use, fine-tuning the job demands-resources model using conservation of resources theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 141–150.

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method bias in behavioral research, A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 879–903.

Yemane, R., & Fernández-Reino, M. (2019). Latinos in the United States and in Spain: the impact of ethnic group stereotypes on labour market outcomes. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1622806

Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., … & Vos, T. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 382, 1575–1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6

Zhang, Y., & Liao, Z. (2015). Consequences of abusive supervision: A meta-analytic review. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 32, 959–987.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix A

Appendix A

Factor loadings for measurement items

Climate for inclusion | Loading |

|---|---|

In this organisation, people’s differences are respected | .85 |