Abstract

Although there is increased need for closing the gap between educational research and policy to better enable effective practice, addressing the problem remains a challenge. A review of current literature reveals a lack of systematic guidelines which clarify how collaboration between researchers and policy-makers can actually be achieved. Therefore, this study aims to articulate a framework which satisfies these needs. We used Lasswell’s stages heuristic model, integrated with perspectives from Kingdon's model, as a basis for building this framework, and conducted semi-structured interviews with nine experts in educational research and policy-making to gain understanding for how to effectuate their collaboration. The study identified six main stages for achieving effective collaboration, and the resulting framework could prove useful to future applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Academic literature has covered the “connecting research, policy and practice” topic extensively in recent years, focusing especially upon factors involved with the use of research in guiding policy and practice (Roderick et al., 2007). Part of this effort has involved investigating issues which hinder the use of research in policy and practice (Baker, 2003; Bellamy et al., 2006; Berliner, 2008; Johansson, 2010; Kennedy, 1997; Manuel et al., 2009; Nutley et al., 2007; Tseng, 2012). From these studies, a series of contributing factors emerged which explained why particular research projects failed to have an appropriate impact upon educational policy and practice. Kennedy (1997) condensed these factors into four distinct groups: (1) low quality of research, (2) irrelevant research, (3) research ideas inaccessible to practitioners, and (4) education systems resistant to change. While researchers have paid considerable attention to these challenges, and identified further explanations, they have also found potential solutions to address them (Cherney et al., 2012; Levin, 2013; Levin & Edelstein 2010; Ion et al., 2018; Tseng 2012). Part of this trend features rising interest in academic literature regarding the use of Research-Practice Partnerships (RPPs). RPPs are entities which forge the long-term collaboration between educational researchers and decision-makers to help identify key problems, then generate appropriate mitigation policies and support them in practice (Coburn & Stein, 2010; Coburn et al., 2013). Indeed, many scholars indicate that RPPs provide a great opportunity to support the use of research in both policy and practice (Donovan, 2013; Fishman et al., 2013; Tseng, 2012). Over the last five years, many universities and institutions, along with a myriad of local and international organizations, such as the Institute of Education Sciences, have helped to fund and develop RPPs (Coburn & Penuel 2016).

However, despite the keen awareness amongst scholars regarding the importance of creating close connections between research and policy for successful practice, a significant gap still persists (Kennedy, 1997; Nutley et al., 2007; Sebba, 2007; Vanderlinde & Van Braaka, 2010; Tseng, 2012). Researchers acknowledge the advantages of using research in policy and practice, but assert that implementation is frequently poor. Tseng (2012) attributes this, in part, to the absence of a systematic approach with guidelines for clarifying “how researchers can produce more useful work, how practitioners can acquire and use that work productively, and how policy-makers can create the conditions that enable both to occur,” (P. 3). Furthermore, Ion et al. (2018) conducted quantitative research to determine what factors might influence the use of research in policy and practice. Their conclusions, published in the journal Educational Research for Policy and Practice, revealed that a major issue preventing collaboration is the lack of “institutional strategies” to provide a comprehensive understanding for how research can be operationalized to inform policy and research to achieve successful practice (Cobb et al., 2003; Poon, 2012; Power, 2007; Urquiola, 2015; Whitty, 2006). Our study attempts to bridge this critical gap in the literature by developing an effective, theoretically-grounded framework which provides systematic guidelines for enabling collaboration between educational researchers and policy-makers, with the resultant benefits this will have towards improving practice. This framework comes complete with clear guidelines, based upon theoretical foundations developed by Lasswell and Kingdon, to explain how collaboration can occur in systematic stages.

2 Literature review

In this study, the literature review is split between (a) research utility in policy and practice, and (b) Research-Practice Partnerships in education. The former provides a conceptual understanding for research utility, while also addressing studies which focus upon the considerations involved with transferring knowledge gained from research into educational practices, while the latter offers practical examples of actual, evidence-based practices; we illustrate several RPPs, along with how well they function.

3 Research utility in policy and practice

The study of research utility (i.e. how well research results find useful employment in practice) dates back to the 1970s and '80 s, an era which Henry and Mark (2003) refer to as the “golden age” for work supporting “knowledge and evaluation use.” Carol Weiss was a leading light in this field. Much of her substantial body of work was driven by the question: “Why does the government support the efforts on research while it will not use these findings?” To address this conundrum, Weiss (1979) emphasized learning how policy-makers might use research, and how they might do so effectively.

Weiss’s (1977) work focused upon developing understanding for the term ‘research use. ‘She did so by subdividing the concept into seven related categories, with the first being ‘knowledge-driven use.’ This refers to how research influences policy development. Next came the 'problem-solving model,’ which involves the direct application of research results in solving a problem. The third category, dubbed the ‘interactive model,’ implies collaborative work in which policy-makers search for knowledge from a wide range of sources, including research. Fourth is the ‘political model,’ where research is used intentionally in support of specific policy stances. In the fifth category, the ‘tactical model,’ research findings tend to be employed outside of their original mandate, deflecting attention, tactically, away from more politically sensitive issues. Weiss's sixth category of ‘research use,’ the ‘enlightenment model,’ involves research findings that have a gradual impact upon policy. Permeating through society, these findings raise public awareness and create an appropriate environment for framing effective solutions. The final category, ‘intellectual enterprise,’ involves research having a broad influence in shaping the way policy-makers and practitioners think about policy. While Weiss’s categories of ‘research use’ are helpful, scholars have subsequently recognized that they overlap and interact with each other (Nutley et al., 2007). As a result, researchers have elaborated upon her work, or used it as a foundation for further study. This has helped policy-makers to understand, support, and use research in their practice (Scott & Jabbar, 2014).

Current debate in the education field regarding “research utility” has shifted to focus upon “gold standards” for translating research findings into actual practice. Many researchers have emphasized the importance of improving the relevance of high-quality research (Berliner, 2008; Kennedy, 1997; Nutley et al., 2007; Tseng, 2012). Mary Kennedy (1997) is one of the more thoughtful authors regarding the disconnect between educational research, policy, and practice. While she has provided many explanations for this predicament, she noted in particular that, “The quality of educational studies has not been high enough to provide compelling, unambiguous, or authoritative results for practitioners,” (p. 4). Kennedy argued that, to provide reliable knowledge when conducting empirical studies, researchers must use an appropriate methodological design. Moreover, some studies concerned the relevance of research in relation to practice. For example, scholars have found that a majority of educational research is actually irrelevant to practice, and fails to address practical problems in the field (Berliner, 2008; Kennedy, 1997; Sebba, 2007; Vanderlinde & Van Braaka 2010). Berliner (2008) further argues that despite the emergence of a real-world context in research, its relevance is often still too weak to affect practice. Farley-Ripple & Jones (2015) conducted a case study to analyze the educational researches that used in practice, they found that these studies were so broad, and complex for implementation.

Another important aspect of making connections between research, policy, and practice is developing communication avenues between the relevant parties involved, making the research accessible (i.e. intelligible) to the reader, and disseminating it effectively to those who need to use it (Bellamy et al., 2006; Nutley et al., 2007; Malin et al., 2018). A commonly used strategy for making research “accessible” involves presenting research findings in clear language, suitably written for educational stakeholders to quickly understand and absorb. Kennedy (1997) argued that the lack of accessibility leads to research having only a weak impact upon policy and practice. She claimed that there is a need to focus upon what makes research accessible for teachers, and how teachers apply research in practice. Tseng (2012) noted that to ensure research is accessible to policy-makers and practitioners, policy reports and executive briefs should be short and “jargon-free.” This will enable readers without research experience to digest the information easily and quickly. Furthermore, Tseng (2012) advised that improving research accessibility should also include developing websites and databases, and conducting short conferences to represent findings, and make them broadly available.

Another important line of thinking regarding the use of research in policy and practice is how to transform research findings into their practical implementation. It is therefore crucial to distinguish between knowing about and actually implementing research (Berliner, 2008; Johansson, 2010; Manuel et al., 2009). Although many teachers and educational stakeholders have adequate knowledge about policy and educational research findings, this knowledge does not necessarily transfer into implementation. This acknowledges a basic need for implementation strategies to convert research findings into the formulation of policy and practice. Levin and Edelstein (2010) provided two strategies to effectuate this, with the first being translation; empirical research findings and policies need to translate into clear, practical steps to help educators understand what they need to do (and why). The second strategy is to link professional development endeavours with research evidence to facilitate the implementation of research findings. Moreover, several authors noted the importance of monitoring and evaluating policy implementation in the field to help promote the program (Nutley et al., 2007; Tseng, 2012; Weiss, 1972). Weiss (1972) defines evaluation as the examination of a program's effectiveness against its pre-determined goals. Evaluation results must, therefore, influence the decision-making process for improving the program’s future. Tseng (2012) considers feedback loops as a helpful strategy for testing how effectively research affects practice and, in turn, how practice influences future research. Similarly, Nutley et al. (2007) indicate that connecting research with practice should not simply focus upon how research affects practice, but the opposite as well. Indeed, practice must inform research; for example, teacher and educational stakeholder perspectives regarding implementation challenges and barriers should help shape future research to address these challenges.

4 Research-practice partnerships in education

In recent years, the field of education has seen increased attention focused upon evidence-based policy and practice. Research-Practice Partnerships (RPPs) have played a significant role in this effort. Indeed academic literature is increasingly candid about the importance of RPPs (Booker et al., 2019). Coburn et al. (2013) define RPPs as “Long-term, mutualistic collaborations between practitioners and researchers that are intentionally organized to investigate problems of practice and solutions for improving district outcomes,” (p.2). This approach focuses upon bringing researchers and educational decision-makers together to identify problems in policy or practice. RPPs tend not to form around a single study, but rather they establish and sustain strong, collaborative relationships between educational leaders and researchers over multiple projects. Instead of simply developing research to address gaps in theory, RPPs try to address real-world issues, such as the challenges which practitioners face while teaching. Tseng (2012) indicates that developing RPPs can lead to greater research utility in the decision-making process. This collaboration helps to address persistent problems in educational practice, and has consequently lead to improved scholastic outcomes (Donovan, 2013; Fishman et al., 2013). Coburn et al., (2013) note that RPPs collect data from target participants, then use analytical techniques to resolve associated research questions. The answers hopefully yield solutions to the larger problems under discussion.

Many RPPs have proven themselves operationally in the USA, and these may serve as useful examples for other nations to employ, or even to expand upon into new forms of partnership. But building RPPs, and maintaining their strong collaborative spirit, is no easy task. Many potential challenges require careful consideration. Indeed, a major initial hurdle involves establishing a good working relationship between researchers and practitioners. Such a bond is termed “mutualistic,” which implies working together over decisions and sharing authority in making them (Coburn & Penuel, 2016; Lon et al., 2019). Rosen (2010) noted that expectation differences between researchers and practitioners regarding their authority and responsibilities may lead to conflict. RPPs must apply deliberate strategies to foster this relationship successfully; they should have carefully designed rules, responsibilities, routines and interaction procedures (Coburn et al., 2013). Previously published work highlights the challenges of building appropriate communication channels between researchers and education leaders (Coburn et al., 2013; Kennedy, 1997; Penuel et al., 2007; Tseng, 2012). For example, researchers and practitioners often face difficulty communicating with one another because there is a range of field-specific language unique to each party in the conversation, language which is not necessarily interpreted easily by their counterparts. To maintain communication quality, each party should keep their language simple, minimizing the use of field-specific terms, and providing adequate clarification for those which prove necessary.

Research into RPPs has also identified a number of problems which arise from the complexities of education systems (Coburn & Penuel, 2016; Coburn et al., 2013); school districts, for example, have elaborate organizational structures. This raises concerns about who one should partner with and how to collaborate across a wide range of disparate goals, priorities and agendas (Coburn & Stein, 2010). It is essential to take this complexity into consideration, with a clear understanding for each participant’s needs, before embarking upon such a collaboration. Scott and her colleagues (2014) noted that political groups, whether inside or outside of education districts, may apply pressure over particular decisions. Coburn et al. (2013) recommend that RPPs should not fall prey to political whim, noting the importance of being able to distinguish between political and educational benefits. Although our literature review focused upon the challenges which RPPs face, we found little evidence of any energy being expended upon the creation of guidelines, designs, frameworks or even strategies for building successful RPPs (Coburn et al., 2013).

In summary, despite numerous scholars and programs around the world having made efforts to promote collaboration between personnel working in educational research, policy, and practice, the disjunction between these essential functions still persists in many education systems around the world, and they struggle unnecessarily as a result. Regarding this very issue, members of AERA have argued the usefulness of creating a better connection between educational research, policymaking, and practice. Indeed, a major thrust for AERA's 2020 annual meeting focused upon developing collaboration between these three parties. This is not a new concern for AERA, of course, but rather an enduring theme stretching over decades. Adding to that, many researchers acknowledge the advantages of using research in policy to achieve effective practice, but assert that implementation is frequently poor. Furthermore, Ion et al. (2018) revealed that a major issue preventing collaboration is the lack of guidelines and strategies to provide a comprehensive understanding for how research can be operationalized to inform policy and practice (Cobb et al., 2003; Poon 2012; Power, 2007; Urquiola, 2015; Whitty, 2006). Our study, therefore, attempts to develop an effective, theoretically-grounded framework which comes complete with guidelines, based upon theoretical perspectives developed by Lasswell and Kingdon, to explain how collaboration can occur in systematic stages.

4.1 Theoretical background

As demonstrated above, our literature review focused upon the “standards” for using research to inform research and policy for the promotion of effective practice, and provided examples of programs (such as RPPs) which foster collaboration between educational research, policy, and practice. This study required a systematic process to develop a framework of guidelines for achieving collaboration between researchers and policy-makers, accomplishing this goal by using the stages model (Lasswell, 1956), integrated with perspectives from Kingdon's model. Lasswell’s stages model (1956) was one of the earliest approaches to have had an effective impact upon public policy analysis; the other being Easton's system model (1957). Its significance is grounded in framing and illustrating the stages of the policymaking process. Although there are now many other public policy process theories, the stages model has retained its relevance, and a diverse group of academics still use it in a variety of forms. Indeed, there is a general consensus for using Lasswell's stages to guide both policy-making and analytic procedures. In the public policy process, problems are first determined, then cited in government agenda, after which potential solutions are formulated, policy decisions implemented, evaluated and then revised (Lasswell, 1956; Kingdon, 2010; Sabatier, 2007). Lasswell’s model, also known as the process/sequential model, has been discussed by many scholars since its introduction (Anderson, 1979; Peters, 1996; Sabatier, 2007). Over the last few decades, however, Lasswell’s heuristic/stages model has evolved from seven stages into its present five stage process; defined variously as either a policy process model, or stages theory (see Anderson, 2014; DeLeon, 1999; Sabatier, 2007). There are five primary stages to the policy process: (i) problem identification and agenda-setting, (ii) policy formulation (iii) decision-making, (iv) policy implementation, and (v) policy evaluation (Fig. 1).

Heuristic/stages model (Lasswell, 1956)

In the first stage, “problem identification and agenda-setting,” the goal is to identify and define an issue which both needs rapid remedial action while also being well-suited to a government’s agenda. The relative importance between the various problems and concerns that attract political and public attention vie for a place on this agenda. Kingdon (2003) indicates that, “the agenda-setting process narrows this set of conceivable subjects to the set that actually becomes the focus of attention,” (p. 4). Cook et al. (1983) addressed, “what factors affect and attract government attention,” indicating that multiple vectors, including the media, politicians and other officials, can play dominant roles in this stage. Societal, economic, and political pressures, ideologies and significant events (such as disasters) are just some of the influential factors involved in identifying problems for agenda-setting (Pollitt and Bouckaert 2000). Blewden et al. (2010) argue that evidence should both frame the problem attracting attention and determine agenda-setting. If a government recognizes their responsibility for addressing an issue, they will add it to their agenda, however, a variety of circumstances/prerequisites frequently need satisfying for this to occur. Benoit (2013) indicated that the populace must acknowledge the issue openly, describing its effects and potential solutions, while also engaging in activities which motivate the government to take positive action. If problems miss the initial agenda, they must wait for the next policy cycle to receive consideration.

“Policy formulation” involves identifying, reviewing, and evaluating a wide range of policy and program responses to a given problem definition. Howlett et al. (2009) describe the policy formulation stage as being where, “…means are proposed to resolve perceived societal needs,” (p. 110). A government will use a variety of techniques to devise plans of action, resulting in a selection of one or more approaches to address a given problem. Kingdon (1995) notes that civil servants, practitioners, researchers, think-tanks, consultants, etc. might contribute to this process. Analysis of possible responses for tackling a given problem (including consideration of alternative ideas) takes place during the “decision-making” phase. This, hopefully, yields informed decisions to shape appropriate policies (Benoit, 2013). Although perhaps self-evident, it is important to select potential solutions based upon their capacity to optimize the utility of decision-makers (Cattaneo, 2018; van Schaik et al., 2018). Howlett et al. (2009) argue that for this stage, decisions should be made that require either positive, negative, or even non-decision responses. Kraft and Furlong (2012) indicate that research should provide evidence to support the decision-making process; this research could explain, guide and examine the potential effects of a variety of policy options. Such a process is often influenced by society at large, so policy-makers must at least consider their requests and demands.

Policies translate into action during the “implementation phase”. Research is almost always employed to define the funding at this stage, along with the policy and program requirements to implement policy decisions. It is considered the most important phase of the policy-making process, because the quality of a policy’s execution usually determines how well it meets its objectives (Ripley & Franklin, 1986). In this context, if the policy is not implemented properly, it is rarely possible for it to achieve its goals, no matter how well-formulated. Moreover, political, economic, and technological conditions, etc. can have profound influence upon implementation (Howlett et al., 2009).

Outcomes of implemented policies are assessed in the “evaluation stage” (Peters, 1996). This is the moment where policymakers and/or consultants verify whether enacted policies achieved their desired goals (Benoit, 2013). A number of scholars have provided valuable insight into the role that research plays during this phase (Baum, 2003; Renée, 2006). For instance, Kulaç and Özgür (2017) describe how empirical studies use surveys and/or interviews to aggregate data from target groups about an implemented policy’s effectiveness. Furthermore, if a policy fails to achieve its aims, the policy-analysis process returns to its first stage for re-tooling (Jann & Wegrich, 2007). Indeed, Tseng (2012) argues that while many scholars have made great effort to understand “research-to-policy and practice,” they have neglected the importance of “practice-to-research.” Lasswell’s model addresses this concern, however, as the evaluation phase focuses upon assessing the policy from research-to-practice, as well as its reverse.

It is important to note here that Kingdon’s Multiple Streams model was developed as a response to the Heuristics model. Kingdon (2003) argues that policy-making should be a dynamic process in which many stakeholders engage with identifying and making sense of public problems and potential solutions with the goal of determining their rank in the agenda. Kingdon’s model is more fluid than Lasswell's, because the latter model is a linear, rational process which takes place in a vacuum, and is performed by a single, logical actor. This is in contrast to the Kingdon model, where policy-making occurs via macro-analysis involving several actors, organizations, institutions, and activities, all of which affect the end result. Kingdon’s model also complicated our understanding for the agenda-setting phase. For example, Kingdon (2003) indicated that three different streams influence the agenda-setting process: the problem, policy, and politics. The ‘problem stream’ is similar to Lasswell’s model in which a problem needing immediate action drives the agenda. The policy stream is where tractable approaches, or policy alternatives, originate. Whereas the political stream indicates that the political situation is affected by elections, pressure from officials, administrative changes, public opinion, etc.

Scholars in policy science have devoted a lot of effort into understanding the policy-making and analysis processes. In our framework, we discussed two of the more significant policy process models (Lasswell and Kingdon), and while there are other useful models to choose from, their absence here should not be misinterpreted for any lack of perceived relevance on our part. We focused upon Lasswell and Kingdon for two major reasons: (1) the need for a systematic approach to guide the collaboration between researchers and policy-makers in the education field, and (2) to explain how the public policy process is developed. Our framework uses the five stages in Lasswell’s model as a basis for establishing systematic phases for achieving collaboration. Moreover, our framework agreed with Kingdon’s perspective that these stages need not be linear; overlapping and interaction between these stages should be expected in the framework for collaboration between research and policy. Finally, this study makes an additional contribution by essentially breaking new ground for Kuwait (our home) and other nations with similarly poor collaboration between educational research, policy, and practice, all of which presently remain under-explored in such countries.

5 Methodology

The framework in this study used qualitative analysis with nine, semi-structured interviews conducted with Kuwaiti educational researchers and policymakers serving as “experts”. The semi-structured interview allows conversations with experts to grow organically, since the questions do not have to come in a specific order; they can react extemporaneously to new ideas or emerging world views which arise naturally as the interaction flows (Merriam, 1998). The resultant aim for these interviews, as already implied, was the creation of a framework providing systematic guidelines to facilitate more effective collaboration between educational researchers and policy-makers to better achieve effective practice. As already implied, the study used Lasswell's stages model as guidance for the interview questions.

5.1 Data collection and participants

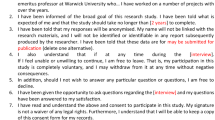

The researchers selected participants for this study using a purposeful selection method. This method involves choosing experts based upon their knowledge and its relevance to the endeavour being undertaken (Babbie & Motuon, 2001). In other words, the advantage of a purposive sample lies in its ability to enrich the research data (Creswell, 2014). Participants were divided into two groups: researchers, and policy-makers. Specific criteria for selecting each group’s participants were identified to ensure that their perspectives and experiences served the purpose of this study. The researchers we selected had to have (i) earned a PhD in the education field, and (ii) have relevant publications, and/or have participated in projects which address the policy formulation and implementation processes in education. Whereas each policy-maker we interviewed had to have (i) a minimum of five years’ experience in the education field, and (ii) real-world experience in the formulation, implementation, or evaluation of educational policies. Participants came from Kuwait’s Ministry of Education (MoE), higher education institutions, professional associations and independent research centres in Kuwait (see Table 1 for their profiles). Prior to contacting potential participants, we first obtained permission from the MoE to conduct the study. We then requested assistance from the MoE to help us find relevant participants; they introduced us to several policy-makers and researchers with experience in educational research and policy. After each interview, we asked participants to suggest other policy-makers or researchers whom they believed we should interview.

The participants included 4 researchers and 5 policy-makers, 3 of whom were female and 6 male. Their experience levels ranged from 7 to 25 years. Before the interview, each expert completed and signed a consent form. The roughly 45 min, audio-recorded interviews took place either via telephone or face-to-face. The study used a semi-structured interview approach in which we asked each expert ten identical questions. We allowed discussions to unfold and expand naturally for each question, enriching our understanding, rather than simply moving on to the next question following a basic answer. The ten questions were split evenly across five sections, reflecting the five stages in Lasswell’s model: (i) problem identification and agenda-setting, (ii) policy formulation (iii) decision-making, (iv) policy implementation, and (v) policy evaluation. Each section contained two questions which focussed upon learning what is needed to achieve collaboration, and how to do so in each phase. The authors asked the experts “why”, “how”, and “what” during the discussions surrounding each question to gain comprehensive explanations and insight into their answers. The interview recordings were transcribed and constitute the study’s main data source (Benesch, 2001). To maintain confidentiality, each participant received a pseudonym, with all identifiers masked as thoroughly as possible. These pseudonyms began with a letter, ‘R’ for researcher or ‘P’ for policy-maker, followed by a number, creating a unique name for each expert, but one which clearly identified their background for ease of use during our analysis.

5.2 Data analysis

For data analysis, the researchers applied a hybrid technique similar to Fereday and Cochrane (2006), blending a deductive approach (using an a priori template of codes) with an inductive example where new categories arose from those in the data set categories. Prior to transcript analysis, we created a table in Microsoft Excel, serving as a codebook to organize the data. We began by first adding each expert’s pseudonym to the codebooks so we could later identify the unique set of data derived from their responses. This would provide a streamlined view, making it easier to clarify where experts differed or agreed regarding each theme (Marshall & Rossman, 2011). Then we added the five main themes generated via Lasswell's stages model: (i) problem identification and agenda setting, (ii) policy formulation and legitimation, (iii) decision making, (iv) policy implementation, and (v) evaluation. The codebooks, at this stage, were effectively operating as data management devices, coordinating similar phrases stripped from the data to facilitate interpretation. The next step featured deductive analysis, where the researchers read in the data and assigned it to the specific themes and participant names created a priori, as per the Laswell’s stages model. For example, the first two questions involved the ‘problem identification and agenda setting’ phase, so expert responses entered the codebook under these themes, and a similar approach occurred for the subsequent pairs of questions which followed, with responses again assigned to their appropriate themes. Inductive analysis took place in the third step. Here, the researchers generated categories and their related sub-categories, where applicable, with codes containing “meaningful units of text” assigned to their appropriate phase. If we found meaningful information outside the bounds of the present set of themes, then we would generate appropriate additional themes to accommodate them as needed. The researchers repeatedly read and re-read the unexpurgated transcripts of each expert interview to code and recode them. They also opened codes and developed definitions for each prominent category. The final step involved comparing the coding results from both analyses (deductive and inductive), balancing one against the other in an iterative process which connected the codes to uncover common themes in the data, grouped under the previously identified headings. If a code failed to match a Lasswell stages model theme, we could generate an appropriate additional theme to accommodate it. This proved necessary, as our analysis revealed the need for one additional theme/stage, which we labeled “prior to collaboration,” a conditional phrase which most experts mentioned.

Of note, each person involved in conducting this study coded the interview transcripts individually, with results being compared collectively. Disagreements in the coding process led to several modifications, and discussions to improve the work. Using back-translation (Brislin, 1970), Arabic and English versions of the findings were examined by two professional translators to ensure no significant discrepancies. In the data analysis, we mainly depended upon the Lasswell Heuristic stages model, while ensuring that Kingdon’s perspectives were also captured within the study codes and themes. One way we achieved the latter was by not using phases in a strictly linear fashion, indeed we welcomed their overlapping and/or interaction. For example, some codes could overlap different phases, with one of them depending upon earlier stages (like how the evaluation phase relies upon prior phases).

6 Proposed framework

The intent of this study was to develop a framework to provide guidelines for building collaboration between educational researchers and policy-makers in order to promote effective practice. To achieve this goal, as already noted, we conducted interviews with researchers and policy-makers who had relevant experience with our study topic. Data collected from four “researchers” and five educational “policy-makers” varied in perspective, length, and detail. The breadth of this feedback proved to be of great value in developing the framework.

Broadly speaking, each expert agreed that achieving collaboration between research and policy has great potential for improving educational outcomes. For example, one expert noted that, “…achieving this [partnership between research and policy] would improve the education system.” Most experts indicated, however, that the issues related to collaboration between research and policy are complex. To address this complexity, experts provided a comprehensive explanation for how collaboration between research and policy could be achieved via six main policy-making phases (see Fig. 2). The following section reveals their views for each stage:

6.1 Prior to collaboration

Most experts argued that preparing an appropriate environment for developing collaboration between research and policy should be the first step before starting any research; having a well-prepared system/environment helps to facilitate collaboration. They indicated that this environment must accommodate the demands of collaboration; i.e. establish a solid foundation for future steps. In this phase, expert views centred upon the major requirements for establishing collaboration. They concluded that there are three essential steps to consider: (i) signing official agreements; (ii) establishing research centres, and; (iii) providing adequate funding.

6.1.1 Signing official agreements

Most experts concurred regarding the importance of having an official agreement in place between collaborating parties before work could start. This agreement would help establish the formal decision-making processes for future actions between parties. Affirming this, one expert (P2) noted, “An official agreement is very important before working to solve the educational problems.” The experts indicated that this agreement should contain a clarified set of all instructions, details, and requirements expected from each party. They stressed the importance of identifying which people would be involved in the collaboration, what type of problems they should focus upon, and the timeframe for accomplishing the required tasks. Moreover, they highlighted that the agreement should consider the geographic scales and timeline involved; i.e. will the collaboration cover a school, district, state, or even a country, and over what time duration shall this collaboration take place. Additionally, all responsibilities, roles, rules, and protocols for each party must be carefully delineated. Furthermore, to establish good relationships between researchers and policy-makers, each person involved in this collaboration must know and understand their rights and duties. Indeed, having official agreements helps to preserve rights and show a commitment for using research results to build new policies. Reiterating this, expert (S4) explained, “Having an official agreement between the researcher and policy-maker is a good start to protecting our rights and freedom of expression.” Adding to this, expert (P3) noted concern, stating that, “If there is no very clear agreement, there may be conflict between researchers and policy-makers.” He recommended that the agreement consider all relevant details and encapsulate them within a succinct, clearly written document, with all parties signing on right from the beginning, to reduce the risk of future misunderstanding regarding payments, responsibilities, timeframes, etc.

6.1.2 Establishing research centers

Experts stressed the need for establishing an independent research centre responsible for providing salient evidence about the problems facing education. This centre would develop an avenue of collaboration with educational policy-makers for conducting useful research, while offering advance analysis of research strategy outcomes. Experts suggested either using research centres which already exist, or creating new ones. With the former, one could select an established research centre at a university, educational institution, or from within the independent research sector. For the latter, the MoE could establish their own educational research centre, creating new positions for researchers to conduct inquiries that are directly related to MoE objectives and policy aims. Such establishments could provide staff expertise on educational research, assessment, evaluations and other forms of assistance. One expert (P2) provided support for creating a new MoE research centre, noting: “These research centres determine the needs of researchers effectively, helping them to work independently, and providing them with several types of resources.” Furthermore, three of the experts (R1, P3, & P5) agreed with him that: “In my opinion, forming research units within the aims of producing properly researched information which can be used later by policy-makers is important in this process… The MoE should seek to achieve a closer and more stable relationship between researchers and policy-makers in a more formal way.”

6.1.3 Providing adequate funding

Experts agreed that the availability of adequate funding must be considered before facilitating collaboration between parties, as such cooperation requires significant effort, resources, and technology. They further noted that these funds would need to cover all collaboration expenses, such as employees, resources, labs, technology, etc. Additionally, they highlighted that determining the funding requirements and source would have to occur before research began. Two experts suggested local government as being a possible funding source, which might then open the window for national initiatives and government grants. One expert (R1) clarified this point, stating:

I believe that the funding is an essential component in any collaboration process…. To do so, our University increased the budget for research and encouraged researchers to look for alternative financial and international research opportunities to fund research… Last year, our department signed an agreement with the MoE to fund a lot of education research that has a common interest in a way to help MoE leaders make good decisions.

6.2 Problem identification and agenda-setting

This stage focuses upon the procedures for identifying the problem(s) to set the educational agenda, and how facilitating collaboration between researchers and policy-makers will occur. The experts noted that the most important problem(s) should be identified and placed in the educational agenda. Experts provided several criteria for selecting priority problems, such as those which have (i) a highly negative effect upon practitioners and/or students, (ii) an effect upon a significant number of educational stakeholders and/or students, and (iii) problems related to disasters, wars, or sudden events. One expert singled out the coronavirus pandemic as a particularly problematic example of the latter, indicating that a lot of research is needed to provide a high-quality, online learning process model. He further noted that, “[This] research may focus on the impact on students’ achievement, learning, and how to increase learning effectiveness during this pandemic.” He explained that this type of research would be of great benefit to overcoming this critical period by helping to achieve positive educational outcomes. Moreover, the lessons learned would also help lay the foundation for surmounting similar disruptions in the future.

In terms of achieving collaboration, experts stated that there is a need to interact with a range of stakeholders (e.g. teachers, school principals, government officials, etc.) and educational policy-makers in order to establish and define a problem clearly. Educational policy-makers are responsible for identifying the initial problems, while providing opportunities for researchers and other parties to share their perspectives. After selecting priority problems for the education agenda, experts agreed that policy-makers should then task researchers with finding solutions. The experts also indicated that positive outcomes would depend upon following appropriate strategies. These strategies fall into two main categories: (a) establishing a research proposal panel, and (b) considering only high-quality research.

6.2.1 Establishing a research proposal panel

The experts expressed belief in the value of a research proposal panel. These panels would provide researchers with the ability to fully understand the scope of the research task at hand, while also allowing the free exchange of ideas for how best to tackle it. Furthermore, they noted that a research proposal panel would help address two significant concerns: (i) research-applicability, and (ii) research-bias. One expert indicated that these proposal panels would clearly identify the boundary conditions surrounding a particular problem by providing researchers with complete details related to school infrastructure, student population size, education system ability, etc. This would allow researchers a deeper understanding regarding a proposal’s affordability, and help to ensure the applicability of their labours. For example, expert (P1) stated that, “Some research is very good, but we cannot implement it due to many challenges and difficulties.” He expanded upon this point regarding the benefits of proposal panels, stating that, “It will help to select the research that fits in with our ability.” Another expert stated that, “There is a huge gap between what the researcher does, and what we need to know in practice… most of the research is too fussy, too concerned with justification, and doesn't reflect the real lives of our teachers at school.” Therefore, creating a research proposal panel will help select realistic, more applicable research efforts which more properly fit our educational capacity. With regards to the potential for research-bias occurring in the writing up of results, two experts indicated that when educational researchers undertake “research-for-policy,” their work must inevitably contend and compete with a mix of political and economic priorities, not to mention values, that influence policy and practitioner decision-making. This can conspire to lead research astray, biasing results to match perceived desires rather than realistic outcomes. Experts therefore stressed that policy-makers must allow researchers to have a completely independent perspective in their efforts to improve education. Establishing research review panels that openly share research proposals will help avoid this bias, and make the selection of appropriate research more likely—thereby reducing wasted effort.

6.2.2 Considering only high-quality research

Most experts express the importance of conducting high-quality research. They indicated that both researchers and educational policy-makers must agree to appropriate research criteria from the very beginning. This will help researchers to adhere to requirements as they conduct their work. Expert perspectives regarding what qualifies as “high-quality” research focused upon four factors. Firstly, they indicated that the term ‘high-quality’ referred to research which is both relevant and addresses a problem in an effective way. Stressing the importance of achieving this correctly, one expert (R2) provided a comprehensive explanation describing the unfortunate reality at his own institution:

“I think that the problems being discussed in research are mostly related to researcher interest or point of view… It is important that the researcher consider the priority of a long list of research-users such as teachers, administrators, parents, policy-makers, voluntary organizations, professional associations, the media, the general public, and of course, the researchers themselves... Unfortunately, in my institution the researcher writes research only to get tenure… and when they get tenure they stop doing research… Problems they discuss in their research are far away from what school teachers and leaders really need…”

Secondly, the experts emphasized that high-quality research always builds upon a good methodology. Two experts noted that the research should involve an empirical study rather than theoretical discussions or a literature review; i.e. it should employ surveys, interviews, experiments, or other statistical techniques to measure the quality of solutions. For instance, an empirical study could use a survey to explore the reasons behind a problem and its associated effects upon society (e.g. teachers, students, and/or parents). If a problem is significant enough, the government will add it to their agenda. One expert also suggested that conducting teacher interviews should be required; such involvement will help researchers gain better understanding for the real-world realities of the problem.

Thirdly, the experts stressed the importance of the reliability and validity of evidence. Expert (R1) noted that, “Considering reliability and validity helps us to know how well our methods or techniques are accurate and consistent.” Expert (R3) stated that, “Researchers should improve the study design, checking and verifying and replicating, to reflect the teachers' needs.” It is also important to ensure that a research study measures what it intends to measure, and to ensure results are stable as well.

And finally, two experts encouraged cooperative work between researchers. For instance, having multiple researchers conduct similar studies helps to broaden the perspectives, experiences, and views, and this contributes to improving research quality. Demonstrated repeatability is also a part of this process.

6.3 Policy formulation and legitimation

In the previous stage, the research review panel selected a variety of research avenues to pursue. Following the completion of this wide range of research efforts, the educational policy-makers must now read the resulting reports to formulate their policy recommendations. A meeting between each party involved is needed to properly review all possible solutions. In order for the policy-makers to make informed decisions though, they first need to properly understand the research reports. Some of this study's experts expressed a concern for potential misunderstanding between researchers and policy-makers at this stage. They noted that most policy-makers do not have prior experience with research, and therefore may not fully understand the research effort nor its findings. The experts gave a variety of recommendations for how researchers should prepare their reports to ensure that policy-makers properly understand them, and these data can be separated into two main categories: (a) making research language understandable, and (b) facilitating research accessibility. Each of these categories is addressed in detail in the following subsections.

6.3.1 Making research language understandable

The experts indicated that, to be effective, research must be both readable and understandable by educational policy-makers and other practitioners. They suggested three techniques to ensure research is clear to policy-makers and educational stakeholders: (i) reports should be short, (ii) with appropriate language, and (iii) guided by a knowledge transfer expert. Regarding Short Reports, two experts indicated that policy-makers have no need to read excessive details regarding the literature review, research procedure, or results. For example, one expert (R1) stated that, “We need the conclusion, what is important, and how we solve the problem. They do not need to read much about research methods, and theoretical background.” Therefore reports should be brief, with concise explanations for research methods, results, and implications. This will help policy-makers to read, understand and absorb these reports more easily. With respect to Appropriate Language, two experts expounded upon how researchers must ensure that policy-makers and other practitioners find their reports fully and easily understandable. Researchers must therefore write their reports using clear language, avoiding overly technical or complex descriptions and scientific language. As an explanation, the experts noted that policy-makers often regard overly-technical and complex language as a barrier to their proper understanding of research reports. They stressed that if a partnership fails to consider establishing appropriate communication mechanisms, the benefits of the research may not be fully realized, or even applied at all. One expert (P2) explained this problem clearly:

“Researchers are writing articles for publishing not for practice! ... Several times I received reports from researchers about implementing new programs or learning strategies… [and] these reports are written in an academic and theoretical way… How can I transfer their ideas to teachers, parents, and school leaders? … I believe that the gap between researchers and policy-makers is related to how to understand the research findings…”

(3) Knowledge Transfer Expert: One expert (P3) indicated that the ideas involved in “knowledge transfer” may help translate research findings into more accessible forms for educational policy-makers to better absorb and understand. The expert stated that, “It would be advisable that educational institutions involve a knowledge-transfer expert to close the gap between researchers and policy-makers in understanding any academic language employed.” This particular reviewer is a ‘knowledge transfer expert’ with significant experience in the practical aspects of interpreting educational research findings for policy-makers and stakeholders. He noted that many teachers, principals (with educational doctorates), teacher-researchers and principal-researchers may be effective in this role.

6.3.2 Facilitating research accessibility

Experts stressed that, to facilitate their collaboration, it is essential to establish a network between educational stakeholders, researchers, and policy-makers. They suggested two strategies for creating this collaborative relationship: (i) holding face-to-face meetings, and (ii) establishing an online database. With respect to Face-to-Face Meetings, it is imperative to hold them periodically to discuss a project’s progress, review any issues or misunderstandings which may have arisen, and to make mid-course corrections, if needed, based upon what has already been learned. At these meetings, researchers will come to understand the constraints of educational policy-making. They will also have a forum to discuss their ideas, possible solutions, and policies with educational stakeholders. These meetings will also provide opportunities for policy-makers to express their concerns and discuss aspects of the project which need clarifying with researchers. Such meetings are also essential to developing the human bonds and sense of trust between parties; an important ingredient to the success of any joint endeavour. Regarding an Online Database, establishing such resources with mutually relevant data facilitates the flow of information between researchers, policy-makers and other educational stakeholders. They help each party keep up to date with progress, to review research reports and findings, etc. These databases also make it easier for participants to receive and answer questions from other members. One expert (P1) expounded upon the benefits of maintaining an online database, stating:

“We live in a technological era and taking advantage of technology will facilitate the collaboration between researchers and educational policy-makers and other educational stakeholders… Online databases help researchers to review their findings easily and quickly, and at the same time enable policy-makers to review the research and send their concerns, questions, and suggestions to researchers… This is a good idea!”

In summary, experts indicated that a wide range of research should be reviewed and evaluated in this phase. They highlighted the importance of reporting research in appropriate, understandable language, and encouraged both policy-makers and researchers to discuss research progress via face-to-face meetings, while also sharing information within an online environment.

6.4 Decision-making

Six experts confirmed this stage as being the most important for collaboration in educational research, policy and practice. The experts stressed that all decisions should result from deep analysis of the available solutions/evidence. This will help to shape appropriate policies from an informed perspective. Experts state clearly that decision-making is not a random process, and must evolve from both (i) scientific evidence, and (ii) the balancing of interests.

6.4.1 Using scientific evidence

Experts agreed that selecting the strongest scientific evidence to support a decision helps ensure that the correct decision emerges. Bolstering this point, one expert (P2) stated that, “To have the ability to make successful decisions, these decisions should depend on strong evidence… every solution should be taken under consideration.” To make sure that the most appropriate science informed these decisions, the experts encouraged choosing research that is relevant, of high quality, and in possession of significant and reliable evidence. Consideration of an education system’s capacity to implement potential solutions must also be factored into the policy decision process. Experts suggest that, when making a decision, there is a need to define alternate options, as this will help create a more deliberative decision-making process.

6.4.2 Ensuring the balancing of interests

Experts clarify that this process requires identifying the options and making selections based upon the values, preferences and beliefs of decision-makers and stakeholders. Decision-makers should balance their choices against the potentially negative consequences of their policies as well. Experts suggest that indivisible resources and unequal stakeholder stature can sometimes constrain educational researchers and policy-makers in their efforts to balance interests. Therefore, two of the experts emphasized the need for a positive collaboration climate for sharing ideas and interests. A single, clear decision should result from this stage.

6.5 Policy implementation

Most of the experts stated that having a well-formulated policy is no guarantee of its implementation achieving intended goals. Therefore, educational stakeholders should work together to execute policy, with guidance from the researchers involved in its creation. Towards this end, experts suggested: (i) conducting short training courses/workshops, and (ii) creating step-by-step guidance.

6.5.1 Short training courses/workshops

The experts were concerned that the educational stakeholders responsible for implementing policies may not understand the procedures involved with carrying them out. To overcome this hurdle, the experts argued the importance of holding short training courses or one-day workshops to more effectively explain new policies to the appropriate parties. Buttressing this point, expert (R1) noted that, “Practical workshops would help teachers to learn how to employ these policies.” Whereas expert (P4) suggested that if the researchers involved in policy formulation provided these training courses, it could be very beneficial:

From my experience… I think that a clear perception of what researchers and policy-makers mean could enhance policy implementing successfully… I see that researchers who take part in formulation of the new education strategy should be responsible for training teachers and leaders.

6.5.2 Creating step-by-step guidance

One expert recommended that writing a guideline report covering practical methods, such as step-by-step instructions, for shepherding stakeholders through the implementation process should be sufficient, and preclude any need for reading research details. As the experts emphasized earlier, research findings should be translated into practical, easily explained steps. These steps will make it easier for stakeholders to implement new policy. Expert (R2) implied this, stating: “I assume that development of clear policies and procedures will help stakeholders to define and implement best practices in the educational field…”.

6.6 Policy evaluation

All experts agreed upon the importance of evaluation in building successful policies. Indeed, expert (P4) stated: “If we do not evaluate our policies, we will not know if these policies achieved our goals or not!” Experts suggested that researchers should use academic tools and methods to measure a policy's quality, following its implementation, to verify how well it met intended objectives. Statistical techniques, surveys and structured interviews, to aggregate data from appropriate target groups about the newly-minted policy, could help achieve this. The experts in this study provided a number of ideas regarding policy evaluation, and these data separated into three main categories: (i) ongoing feedback, (ii) observation, and (iii) two-way evaluation.

6.6.1 Ongoing feedback

Two experts recommended that policy evaluation should occur periodically; i.e. researchers should work with policy-makers to collect views and impressions about the new policy from educational leaders, teachers, and/or students. Using surveys and interviews will help researchers and policy-makers track the real-world impact of their policies. Furthermore, the experts recommended that researchers who analyze these evaluations should send their report/conclusions to the educational stakeholders involved. When a new policy is successful, periodic evaluation is still important to ensure success continues, while also allowing for the discovery of potential improvements. Expert (P2) stated that:

“I believe that it is necessary to involve educators and results of recent research in the evaluating process of the educational policy…in the long term … This will help us to understand the strengths and weaknesses in the implemented policy… Therefore, we encourage leaders in different school districts to have a regular meeting with educators to listen to their needs and see what they think about the new decisions made by MoE”.

6.6.2 Conducting observations

One expert (R3) indicated ‘observation’ helps determine if a policy is successful. He stated that, “We may select a couple of schools in different areas, and visit these schools to conduct observations to evaluate the policy’s impact.” He also argued that observations take time and effort, making it virtually impossible to make observations at all schools. Therefore, overall effectiveness must be surmised from the statistical integration of survey results from randomly selected schools from different districts.

6.6.3 Considering two-way evaluation

Experts stated that the policy evaluation process should involve two-way analysis; focusing upon research-to-practice and its reverse, practice-to-research. Simply put, if the evaluation reveals that a policy falls short of intended results, then researchers should endeavour to explain these failures, along with suggested revisions for raising performance. This is one of the benefits of collaboration; it helps to ensure improved outcomes in subsequent policy iterations.

7 Conclusions

This study focused upon developing an effective, theoretically-grounded framework to provide clear and complete guidelines for facilitating collaboration between educational researchers and policy-makers, leading towards more effective practice. We began with a literature review to investigate the connections between policy and research in education (Baker, 2003; Bellamy et al., 2006; Berliner, 2008; Cherney et al., 2012; Johansson, 2010; Kennedy, 1997; Manuel et al., 2009; Nutley et al., 2007; Tseng, 2012). Next, we developed the study’s framework, building it around the theoretical foundations in Lasswell’s stages model and Kingdon’s perspectives, to provide clear and systematic stages for building guidelines which foster collaboration between researchers and policy-makers. As part of this aim, the study used a qualitative research method to conduct semi-structured interviews with nine experts in educational research and policy-making fields, exploring their perspectives regarding collaboration between personnel involved with educational research and policy-making. In accomplishing this task, this study helped advance the debate concerning how researchers can produce more useful research, how practitioners can acquire and use that research, and how policy-makers can create the conditions enabling both to occur.

The results confirmed that issues related to this collaboration are complex. To help simplify this situation, as already noted, this study adapted Lasswell’s heuristic/stages model (1956) to identify the six main stages critical to achieving effective collaboration: (1) prior to collaboration, (2) problem identification and agenda-setting, (3) policy formulation and legitimation, (4) decision-making, (5) policy implementation, and (6) policy evaluation. These six stages are summarized as follows:

-

1.

‘Prior to collaboration’ recognizes that for collaboration to thrive, a well-prepared system/environment must be in place before work begins. This involves having three key elements: (i) a formal, succinct agreement (ii) a research centre, and (iii) sufficient funding.

-

2.

For problem identification and agenda-setting, ‘the study affirmed the importance of identifying the most significant problem and setting it as the agenda's priority (Bultitude et al., 2012; Lasswell, 1956). This is where the collaborative work, the sharing of relevant ideas, perspectives and issues, between researchers and educational stakeholders becomes critical. The study results suggest the creation of a ‘research proposal panel’ to both allow the free exchange of ideas and weed out irrelevant concepts, so that resources can focus upon enhancing the better investigative ideas and thereby promote the creation of high-quality research. Proposals must be relevant and follow strong methodology (Kennedy, 1997; Tseng, 2012). Indeed the quality and relevance of the research, along with its accessibility, address a major issue in the gap between research and practice (Kennedy, 1997).

-

3.

‘Policy formulation and legitimation’ occur once the research proposals selected in the previous phase are completed and their findings submitted. Since policy-makers typically have little-to-no experience conducting research, the reports must be ‘accessible;’ i.e. they should be short, succinct, use appropriate language, and involve a knowledge transfer expert to help ensure information is easily absorbed and understood by all parties (Cooper, 2014; Cooper & Shewchuk, 2015; Malin et al., 2018). Research accessibility can be facilitated by establishing a collaboration network, which includes face-to-face meetings between relevant parties and an online database for easy sharing of research updates, data and communication.

-

4.

Educational policy-makers will review research report findings to aid ‘decision-making’. The study confirmed that this stage is pivotal to the whole endeavour; a key consideration being the vital role of scientific evidence in analyzing educational policy alternatives. Decisions must also balance competing interests by considering potentially negative repercussions, and the constraints of reality, such as budget availability, political issues, cultural norms, etc. Collaboration between parties here is essential for research results to be understood, believed, translated into policy and enacted successfully. Eyler et al. (2010) stress that using the best available evidence and systematically collecting data will allow educational stakeholders to see that evidence-based policymaking is the best way to help ensure new policies produce optimal results.

-

5.

With policy implementation, educational stakeholders must work together to execute policy with guidance from the researchers involved in its creation. The study's experts suggested creating step-by-step guidelines for policy implementation and conducting short training courses/workshops for practitioners to help them absorb and perform policy requirements. This agreed with a study by Levin and Edelstein (2010) which suggested connecting professional development with policy, and creating practical reports which illustrate each step towards implementing research findings.

-

6.

‘Policy evaluation’ is essential to policy success. A feedback cycle, observation and two-way evaluation are recommended techniques for achieving it. Feedback from practitioners and/or students helps to ensure that a policy achieves its intended goals (Tseng, 2012). Randomly selecting different schools to observe and rate policy implementation in practice, while statistically aggregating the results, contributes to overall understanding for policy effectiveness, as does two-way evaluation. Two-way evaluation involves seeing how well research-based policy translates into successful practice and, when insufficiencies arise, reversing this process to reveal how these failures occurred (Ion & Iucu, 2015; Nutley et al., 2007).

These are all dynamic processes in which many stakeholders can have an impact upon policy making, and they need not occur in a linear fashion. Indeed, stages will likely interact or overlap; for instance, although the formal evaluation stage comes after implementation, evaluation is a continuing cycle, occurring at numerous points during collaboration. Nevertheless, these six stages outlining the processes of collaboration between educational research and policy-making will serve as a useful tool for improving policy, its implementation, and ultimately, scholastic achievement.

7.1 Contributions

As already noted, there is currently an absence of guidelines demonstrating how to build collaboration between researchers, policy-makers, and practitioners (Baker, 2003; Huberman, 1990; Tseng, 2012). This study attempted to address this gap in the literature by developing an effective, theoretically-grounded framework of guidelines for both facilitating collaboration and explaining how to achieve it. As such, it offers a unique contribution to the field. Moreover, this study makes another contribution by building a bridge between theory and practice. While there are a number of theoretical review studies related to research utility and policy analysis (Bogenschneider & Corbett, 2010; Edwards et al., 2007; Gelderblom et al., 2016; Ion et al., 2018), relatively few actually connect theory with its practical application. This study aligned the theoretical foundation of Lasswell’s stages model and Kingdon's perspectives to define a systematic approach for collaboration. It provided a practical example for how this collaboration builds by following the stages model. Furthermore, this study makes an additional contribution by essentially breaking new ground for our country (Kuwait) and other nations which experience similarly poor collaboration between educational research and policy-making. The Kuwaiti education system does not implement any significant partnership programs between educational research and policy-making, so the work presented in this study could help ameliorate that situation by providing a platform to both introduce the collaboration concept and make it’s implementation easier. We developed the framework to be appropriate for Kuwaiti needs as well as any other nation interested in facilitating collaboration. Thus, the researchers anticipate that this framework—along with the stages, guidelines, requirements and considerations necessary for implementing it—will provide valuable ideas for researchers, educational policy-makers and other parties who wish to collaborate. Therefore, educational institutions, policy-makers, and researchers should be able to use these guidelines to further any future collaboration.

7.2 Implications

This study has implications for researchers regarding their pursuit and execution of high-quality research which has a positive impact upon both policy development and implementation. Indeed, we believe our framework can help researchers better understand policy-maker and practitioner needs, preferences, and routines, which will help them to tailor both their research proposals and their resulting research reports more successfully. We agree with Green’s (2008) vision of a “future in which we would not need to ask the question of how to get more acceptance of evidence-based practice, but one in which we would ask how to sustain the engagement of practitioners, patients and communities in a participatory process of generating practice-based research and program evaluation,” (p. 24).

7.3 Recommendations

In consideration of the study’s findings, several recommendations for future research emerged. The first involves acquiring perspectives from additional experts regarding the establishment of collaboration between researchers and policy-makers. These additional data are important to ensuring the internal validity of the proposed framework and would involve asking the experts to examine and provide feedback regarding the framework developed in this study. This subsequent review would likely strengthen the framework’s quality by including further perspectives and knowledge. The future research should expand the sample to include practitioners in the educational field to provide more comprehensive perspectives regarding collaboration. The practitioners could serve as a third party between policy-makers and researchers; their perspectives would enrich this collaboration. Another recommendation includes examining how political, economic, cultural and various social factors might influence each stage of the collaborative process. This will help provide understanding for what might hinder effective collaboration.

7.4 Limitations

While the Kuwaiti experts provided valuable information regarding the guidelines framework we proposed, their different cultural backgrounds, education systems, environments, and educational policies may have biased these data. Specifically put, these data were collected via interview and, therefore, reflect each Kuwaiti expert’s perceptions, which can be subjective; i.e. they depend upon their own personal experiences and prior background related to the education system in Kuwait. Moreover, this study’s sample included only researchers and policy-makers. It is possible that other participants, such as practitioners or educators, could hold other opinions in how best to build an effective collaboration between personnel in educational research, policy and practice. As a consequence, the researchers suggest that future studies should also collect data from educators such as school principals and teachers.

References

Anderson, C. W. (1979). The place of principles in policy analysis. American Political Science Review, 73(3), 711–723.

Babbie, E., & Mouton, J. (2001). The practice of social research. Oxford University Press.

Baker, R. (2003). Promoting a research agenda in education within and beyond policy and practice. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 2(3), 171–182.

Baum, L. (2003). The supreme court in American politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 6(1), 161–180.

Bellamy, J. L., Bledsoe, S. E., & Traube, D. E. (2006). The current state of evidence-based practice in social work: A review of the literature and qualitative analysis of expert interviews. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 3(1), 23–48.

Benesch, S. (2001). Critical English for academic purposes: Theory, politics, and practice. Lawrence Erlbaum Assoc Inc.

Benoit, F. (2013). Public policy models and their usefulness in public health: The stages model. National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy.

Berliner, D. C. (2008). Research, policy, and practice: The great disconnect. V S. D. Lapan (ur.) In M. T. Quartaroli (ur.) (Eds.) Reassert essentials: an introduction to designs and practices, (pp. 295–325) Jossey- Bass, str.

Blewden, M., Carroll, P., & Witten, K. (2010). The use of social science research to inform policy development: case studies from recent immigration policy. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 5(1), 13–25.

Bogenschneider, K., & Corbett, T. J. (2010). Evidence-based policy making: Insights from policy minded researchers and research-minded policymakers. Routledge.

Booker, L., Conaway, C., & Schwartz, N. (2019). Five ways RPPs can fail and how to avoid them: Applying conceptual frameworks to improve RPPs. William T. Grant Foundation.

Brislin, R. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216.

Bultitude, K., Rodari, P., Weitkamp, E., BridginCherney, A., Poveyb, J., Headb, B., Borehamb, P., & Fergusonb, M. (2012). What influences the g the gap between science and policy: the importance of mutual respect, trust and the role of mediators. Journal of Science Communication, 11(3), 1–4.

Cattaneo, K. H. (2018). Applying policy theories to charter school legislation in New York: rational actor model, stage heuristics, and multiple streams. Educational Policy Analysis and Strategic Research, 13(2), 6–24.

Cherney, A., Povey, J., Head, B., Boreham, P., & Ferguson, M. (2012). What influences the utilisation of educational research by policy-makers and practitioners?: The perspectives of academic educational researchers. International Journal of Educational Research, 56, 23–34.

Cobb, P., McClain, K., de Silva Lamberg, T., & Dean, C. (2003). Situating teachers’ instructional practices in the institutional setting of the school and district. Educational Researcher, 32(6), 13–24.

Coburn, C. E., & Penuel, W. P. (2016). Research-practice partnerships in education outcomes, dynamics, and open questions. Educational Researcher, 45(1), 48–54.

Coburn, C. E., Penuel, W. R., & Geil, K. (2013). Research-practice partnerships at the district level: A new strategy for leveraging research for educational improvement. Wiilliam T. Grant Foundation.

Coburn, C. E., & Stein, M. K. (2010). Research and practice in education: Building alliances, bridging the divide. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Cook, F. L., Tyler, T. R., Goetz, E. G., Gordon, M. T., Protess, D., Leff, D. R., & Molotch, H. L. (1983). Media and agenda setting: Effects on the public, interest group leaders, policy makers, and policy. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47(1), 16–35.

Cooper, A. (2014). Knowledge mobilisation in education across Canada: A cross-case analysis of 44 research brokering organisations. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 10(1), 29–59.

Cooper, A., & Shewchuk, S. (2015). Knowledge brokers in education: How intermediary organizations are bridging the gap between research, policy and practice internationally. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23(118), n118.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage publications.

DeLeon, P. (1999). The stages approach to the policy process: What has it done? Where is it going. Theories of the Policy Process, 1(19), 19–32.