Abstract

In her article from 2019, Fleur Johns describes a change: from a style of development work marked by a propensity for ‘planning’, to one marked by a propensity for ‘prototyping’. Our project in this paper is to propose a modest shift in perspective. Where Johns traces a transition from old to new styles, we emphasise the enduring links between planning and prototyping, such that both styles are best understood through their ongoing relationships and entanglements. Returning to Pulse Lab Jakarta (PLJ), the site of Johns’ initial inquiry, we offer a reinterpretation of what might be novel about PLJ for development practice. Our claim is that to understand the particular intervention that PLJ represents, and the new modes of practice it produces, it may be helpful to understand PLJ's work in the manner of a ‘modular’ attachment to existing development apparatuses, that combines big data analytics with design thinking. We then develop some reflections and speculations on the forms and novelty of PLJ in light of our redescription of its work in the language of modularity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Johns opens her article, ‘From Planning to Prototypes’, by taking us on a ‘short walk, across one of Jakarta’s busiest intersections… back and forth between BAPPENAS [Ministry of National Development Planning of the Republic of Indonesia] and Pulse Lab Jakarta’ (Johns 2019, pp. 833–834). For Johns, this walk enacts ‘a change–or rather a set of changes–underway in contemporary global governance’ (2019, p. 834)–from a style of development work marked by a propensity for ‘planning’, symbolised by BAPPENAS, to one marked by a propensity for ‘prototyping’, or more accurately for ‘trial [ling] a particular, prototypical application or assemblage of digital data for development purposes’ (2019, p. 850).

However, if we were to pause en route between Pulse Lab Jakarta (PLJ) and BAPPENAS, at the heart of the intersection that Johns takes us across, we would find a roundabout. In the middle stands the Selamat Datang Monument—a fountain topped by a ‘welcoming statue’. The statue depicts a man and a woman with arms outstretched, welcoming the world to Indonesia, and Indonesians to ‘their future’ (Permanasari 2008, p. 5).

Our project in this paper is to propose a modest shift in perspective, reflected in this pause. Whereas for Johns the walk from BAPPENAS to PLJ is a transition from old to new, we suggest that the walk reminds us of the enduring links between planning and prototyping, such that both styles are best understood through their ongoing relationships and entanglements. In other words, the future might be welcomed not at PLJ, but at that intersection between the two institutions.

Specifically, we offer a reinterpretation of what might be novel about PLJ for development practice. Our claim is that to understand the particular intervention that PLJ represents, and the new modes of practice it produces, it may be helpful to understand it in the manner of a ‘modular’ attachment to existing development apparatuses. ‘Modularity’ is a rather imprecise term, and seems to mean different things for different people within–and studying–organisations such as PLJ (e.g. Johns’ contribution to this issue; Johns 2021). We develop in more detail our choice of that term, the resonances that it has for us, and the work that we want it to do, towards the end of the paper, when it will be clearest.

Following Johns, our argument and investigation is focused on United Nations Global Pulse (UNGP) and its subsidiary organisations, especially PLJ itself. We too approach these organisations as emblematic of an emergent ‘style’ in development practice, and it is this style which is the ultimate object of our analytic attention. To that end, we have surveyed the grey primary and secondary literature–especially PLJ annual reports, blogs, project documents, and practitioner texts. While this does not give us the fine-grained sense of the inner workings of PLJ itself that might be gleaned from ethnographic engagement with PLJ on-site, as found in Johns and certain others who study PLJ, it does give us a window onto the connections between prototyping and planning that emerge from PLJ and UNGP’s self-description in particular.

The paper proceeds, first, by positioning UNGP at the intersection of two trends in development practice–big data and design. In our telling, the new development style that PLJ represents seeks to combine the two, and we explore the ways in which they are set in relation, and to what ends in UNGP’s and PLJ’s practice. In the second section, then, we explore this intersection through an engagement with a set of documents from UNGP’s early days setting out its use-case, while the third section expands our account through short case studies of PLJ’s financial inclusion work. Finally, in the last section, we develop some reflections and speculations on the forms and novelty of PLJ in light of our redescription of its work in the language of modularity.

UN Global Pulse

United Nations Global Pulse (UNGP) was established in 2009 as an initiative of the Executive Office of the UN Secretary-General. It was, according to the accounts of some involved in its work, ‘launched with the mission to accelerate the discovery, development and scaled adoption of big data innovation for sustainable development practice and humanitarian action’ (Hidalgo-Sanchis 2021). In addition to its headquarters in New York, UNGP has over the past decade established three policy labs in Jakarta (founded in 2012), Kampala (founded in 2014), and Helsinki (founded in 2020). UNGP’s work is funded by voluntary contributions from UN Member States, foundations and private sector entities (UNGP 2018a).

The work of UNGP and its associated labs has by now an established place within the scholarly literature as a significant site for the exploration of the possible futures of development practice. Although the literature contains no sustained account of UNGP’s origins, a number of accounts position UNGP at the vanguard of a—perhaps paradigmatic—disruption of development and humanitarian work. For example, in addition to Johns herself, Chandler identifies a style of work in PLJ he calls ‘digital hacktivism’, or an ‘iterative, gradual approach to policy interventions, where each hack uses and reveals new inter-relationships, which create new possibilities for thinking and acting’ (2017, p. 116). Duffield suggests that UNGP more broadly provides an infrastructure through which humanitarians can reimagine ‘disasters as socially distributed information systems’, which provide scope for ‘humanitarian innovations’ to be designed, trialled, and assessed (2019, p. 156). Indeed, UNGP positions itself similarly, as a catalyst for innovation in the development space: UNGP has ‘ignited innovation … developing new methods, consolidating new partnerships and contributing to new ways of approaching development practice and humanitarian assistance’ (Hidalgo-Sanchis 2021). Generalising slightly, we might suggest that what is common to each of these is accounts is: 1) a particular combination of (big) data and some kind of new thinking about how to go about development work, 2) as an ethos or style or practice, 3) that is disruptive and transformative of a planning orientation in development, 4) at epistemological and ontological levels (Johns 2019, p. 836; Chandler 2017, p. 117; Duffield 2019, pp. 156–157).

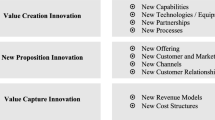

We think it is important that, in its own literature, in the accounts of insiders, and in scholarly work on it, UNGP is positioned historically at the intersection of two trends in public policy practice, and is imagined as simultaneously responsive to both. The first is the long-standing technocratic demand for more ‘evidence-based’ and ‘data-driven’ policy-making processes; the second is the emergence of ‘design’ as a framework for innovation and experimentation in public policy. In our view, the distinctive policy style which UNGP represents is constituted precisely through the coming together of these two strands, and through the particular ways in which they are combined and set in relation.

As regards the first strand: there is in many quarters considerable excitement about the potential for ‘big data’ to enhance the knowledge and knowledge infrastructures available for evidence-based policy-making in development. New sources of exploitable data (data exhausts, crowd-sourced data, new physical and virtual sensors, etc.), combined with new data analytical tools, can supplement or parallel official statistics as a basis for policy-making, help measure progress towards policy goals, and enable faster and more accurate monitoring and evaluation of the performance of policy interventions (Jerven 2013; World Bank 2016).

The aspiration to deliver on this promise has clearly influenced UNGP’s organisational goals and its choice of projects. Early UNGP publications noted that ‘digital data offer opportunities to gain a better understanding of changes in human well-being, and to get real-time feedback on how well policy responses are working’ (UNGP 2009). Robert Kirkpatrick, the Executive Director of UNGP, has consistently emphasised the potential role for the organisation in providing real-time monitoring of crisis response, more precisely targeting development assistance, finding ‘new ways to measure well-being’, improving monitoring and evaluation of development programmes, and more generally, ‘unlock[ing] the value of big data for more evidence-based decision-making that can accelerate progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals’ (Kirkpatrick and Vacarelu 2019; see also UNGP 2009; Anonymous 2014; Burn-Murdoch 2012). The existing metrological machinery of performance management in development policy both provides a condition of possibility for, and shapes the direction of, UNGP’s style of work (Duffield 2019).

At the same time, like others, we also discern an orientation towards design thinking in UNGP’s style of work. ‘Design thinking’ has been deeply influential in the context of contemporary approaches to commercial product design, but it is a rather generic term for a combination of design methodologies with diverse histories and trajectories, and it is now applied in the context of the development of policies as much as products (Torjman 2012; Mintrom and Luetjens 2016; Armitage 2016). In that context, it is used to describe a mode of policy-making which emphasises experimentation, stakeholder participation, user-focus, and the values of empathy and curiosity. Rather than starting with an established problem frame, it emphasises the importance of integrating end-users (often denominated as citizens, or stakeholders) into the process of problem definition. Critical to the design process is empathetic engagement with end-users, and an ability to imagine the world from multiple user perspectives, including through elaborated imagined use cases. Solutions emerge iteratively and experimentally, through a process of prototyping and feedback-informed revision.

The ‘policy lab’ gives organisational form to design thinking, and maps onto UNGP’s formal self-description and self-conception. Policy labs have their own context and history both in the field of public sector innovation (McGann, Blomkamp and Lewis 2018; Olejniczak et al. 2020) and increasingly in international development (Ramalingam et al 2014; HPG 2018). Set against technocratic and top-down rational approaches to policy design, and emphasising the complexity and dynamic qualities of policy problems (Duffield 2019; Ramalingam et al 2014), policy labs are associated with a mode of policy-making with the hallmarks of design thinking: iterative policy-development, user-orientation and inclusive participatory approaches (Torjman 2012). Indeed, for some, an important objective of policy labs is precisely to create a ‘commitment to design thinking’ within policy-making processes (Mintrom and Luetjens 2016).

Clearly, there are deep affinities between ‘design thinking’ and the ‘lean start up method’, ‘tinkering’ or ‘prototype style’ to which Johns connects PLJ, and even to the concept of ‘hacktivism’ proposed by Chandler–as well as to other similar framings, such the ‘agile development process’ (Pellini et al. 2018, p. 100). We leave to another day the question of precisely how they relate to one another, and what if anything is at stake in their different emphases and shadings. But while both ‘big data’ and (something like) ‘design thinking’ are present in numerous accounts of UNGP, the novelty of the Pulse Labs tends to be articulated in terms of their status as synecdoche for one or the other strand and its impacts on existing development practice. For Johns and Chandler, PLJ stands in for a style of development practice structured by design thinking (prototyping, hacktivism) –for which big data is a condition. For others, such as Taylor and Schroeder, and Mann, the work of PLJ stands in for a mode of development work shaped by, and allied to, the political economy of the production, consumption and commodification of ‘big data’, with all that this implies (cf. Johns 2019; Chandler 2017; Taylor and Schroeder 2014; Mann 2018).

This is where our account differs. For us, the novelty lies in the ways in which PLJ extends an existing emphasis on data and evidence, and weaves it together with an emerging ethos of design. That is, the style that we are interested in appears to emerge precisely at the intersection of data sciences and design thinking in the practice of development–and, as we shall elaborate further below, gives that intersection a modular organisational form that both supplements existing development apparatuses, and attempts to prefigure their transformation.

In the following two sections we explore the ways in which these strands are brought together, first, in the early days of UNGP’s founding, and second, through its strand of work on financial inclusion. Importantly, the argument we develop in these sections is not offered in the service of some sort of empirical ‘test’ of the validity of Johns’ and others’ claims about PLJ. Nor is it intended as a causal historical account of why (for and in response to what) UNGP was created. These are interesting questions, but are not central to the story we tell. Instead, we simply wish to draw attention to particular instances in which the relations between big data and design thinking are articulated, performed and enacted, and to suggest that they tell us something significant about the emergent development style to which others have drawn attention.

Scenario Planning

In December 2010, in its second year of existence, UN Global Pulse convened ‘Pulse Camp 1.0’, a three-day event to facilitate brainstorming around the potential uses and architecture of the technology platform that the young organisation sought to create. The event brought together around 100 participants from across the UN system (eg, UNDP, FAO, WFP, UNHCR), the commercial sector (Apple, Microsoft, Google), NGOs active in the digital space (eg, CrisisMappers, InSTEDD, Open Geospatial Consortium), and academic researchers. In preparation for Pulse Camp 1.0, UNGP’s Executive Director Robert Kirkpatrick disseminated a think piece to participants, since published on the UNGP website, in which he sets out an imagined future scenario to illustrate a potential use case for UNGP’s data architecture. It was entitled ‘Self-Assembly Required: A Real-Time Platform for Global Pulse’–there is an echo here of something like the ‘tinkering’ ethos described by Johns–and in this section, that scenario is our primary object of analytical attention, supplemented by a number of contemporaneous accounts of Pulse Camp 1.0 itself (Kirkpatrick 2010; Nielsen 2010a; b; c).

We are not interested in this scenario as a faithful illustration of what UNGP does, or even what it concretely planned to do in its early days. Instead, we think the genre of the ‘hypothetical use case’ can be illuminating in itself. For one thing, it is a genre in which those involved in UNGP’s work can express their aspirations and desires, as well as self-consciously pose problems and surface anxieties, in a somewhat idealised form. In this case, it seems especially significant that the scenario’s author is someone who has had an outsize impact on UNGP’s work from its inception to the present, and that it has been produced precisely for a potentially formative gathering such as Pulse Camp 1.0. Moreover, as noted above, the formulation of hypothetical use cases is a key stage in ‘user centred design’ (Torjman 2012; OECD 2015; HPG 2018; Duffield 2019) –and indeed much of Pulse Camp 1.0 was organised precisely around stages of that design process (Nielsen 2010b). We approach ‘Self-Assembly Required’, then, as much as an enactment of UNGP’s data- and design-oriented style, and an artefact of its commitment to ‘design thinking’, as a faithful and substantive expression of its organizational self-narration.

‘Self-Assembly Required’ opens with a general sketch of the problem in response to which UNGP was (in this account) created. ‘Imagine’, Kirkpatrick asks his readers, a global crisis involving ‘increasing fuel prices, decreasing food supply, and massive job losses’ (2010). Imagine further the range of responses this crisis will elicit in affected populations: some will adapt by ‘taking on extra work, cutting back on non-essential expenses, selling household items they do not need, and switching to less costly foodstuffs and forms of transportation’; but others will be forced to make choices with more severe long-term consequences, to ‘pull their children out of school to work in the market … cut back on the quality and number of meals … forego medical care to save money’ (2010). The key in such situations, he argues, is target the latter actions, ‘to act fast to prevent long-term harm’, and in particular to direct safety net resources to those individuals and communities least able to cope with shocks. Political leaders understand this, he suggests, but at present are hampered by inadequate access to timely information:

What we found […] as we reached out to UN agencies and partner organizations, is that hard evidence on the real-time impacts of the crisis at the household level was pretty much non-existent. The statistical data available was several years out of date and was of no use. All we had to go on were anecdotal reports. (2010)

UNGP, in this account, ‘was created to fill this information gap’ (Kirkpatrick 2010). Specifically, ‘Global Pulse must allow local, national and global leaders in times of crisis to use real-time information to protect vulnerable populations through agile, targeted policy decisions’ (Kirkpatrick 2010). A goal of UNGP’s Pulse Labs should be to ‘help leaders at every level–local, national, and global–detect, characterize, and investigate patterns in collective behavior that could represent incipient impacts and emerging vulnerabilities’ (Kirkpatrick 2010).

This articulation of UNGP’s mission, it is worth noting, chimes with others. Global Pulse has been described by another insider as being ‘born to monitor in real-time the impacts of slow-onset shocks’ (Nielsen 2010a). In a 2013 interview with the New York Times Kirkpatrick noted the significance of UNGP’s creation in the immediate aftermath of the global financial crisis: that crisis, he noted, ‘awakened many at the global level to two significant challenges: not only were we unable to anticipate where and when global hazards would originate, but we also could not predict who they would impact or how.’ The goal, he noted, must be ‘to bring real-time monitoring and prediction to development and aid programs’ (Lohr 2013). The imaginative problem space into which UNGP enters, then, is organised around the governance of precarity, understood in significant part as vulnerability to unforeseen and potentially catastrophic hazards, which in turn is understood to demand, first and foremost, digitally-enabled, rapid and adaptive operational responses (Duffield 2019). (Again, we are not making a claim here about the accuracy of this ontogenesis.)

How, precisely, might UNGP’s future technology platform respond to this demand? We are given a snapshot a few paragraphs later. ‘Several months after the onset of a complex global crisis’, in this hypothetical scenario, Pulse Lab personnel note a number of worrying data points from UN food security monitoring indicators, which track average rainfall, oil price fluctuations, and other early indicators of food security risks (Kirkpatrick 2010). On this basis, they designate identified regions as at risk. Some months later, ‘Global Pulse software automatically picks up a more worrisome pattern–this time through real-time monitoring at the national level’ (Kirkpatrick 2010): a sharp rise in food prices, increased enquiries about fertiliser prices on social media and mobile channels, a rise in the use of prepaid mobile calls, and an increased rate of cashing in food vouchers distributed by an NGO. This information is shared by the Pulse Lab team with local and international networks through the Global Pulse network, and ‘it turns out that a team in a neighboring country government is observing comparable changes in communities on their side of the border’ (Kirkpatrick 2010). Research into community responses to prior similar events suggests two potentially harmful coping strategies: families ‘are likely to pull their girls out of school to work in the market, and they will begin migrating across a nearby border to find jobs’ (Kirkpatrick 2010). As a result:

Pulse Lab staff broadcast text messages to radio station operators to inform them of their concerns about food shortages and sensitize them to listen for calls and messages from their audience that could indicate households are cutting back on consumption of food or migrating for work […] Teachers are likewise alerted to be on the lookout for decreases in girls’ attendance. (Kirkpatrick 2010)

On the basis of a recommendation from the relevant PulseLab team, the national government then sends a team to the region to perform a rapid household-level impact assessment. PulseLab then mobilises relevant and available support infrastructure, using their system to ‘broadcast text messages to key contacts working in the affected communities, such as local government, NGOs, radio station operators, teachers and community health workers, alerting them to the situation, notifying them that additional food vouchers and school feeding programs will be initiated in their community’ (Kirkpatrick 2010). Over the course of the crisis response, ‘Pulse Lab staff monitor the population through a combination of proxy indicators, citizen reporting, and mobile surveys to evaluate the effectiveness of the response’ (Kirkpatrick 2010). Once the crisis is over, or at least at some later point, they review both their own work, and the outcomes of this rapid policy response. The results of this review are used retrain the Global Pulse system in light of the new data, and to ensure that more of the process is automated: ‘next time a crisis hits, the team will have more free time to focus on the aspects of analysis that cannot be automated’ (Kirkpatrick 2010).

Is the work that UNGP performs in this scenario effecting a wholesale shift from one style of development practice to another? In our view, it is best understood somewhat differently: UNGP is imagined and narrated here as fundamentally supplemental, as working in tandem with a very traditional and recognisable ‘planning’-style development apparatus, rather than replacing it. Indeed, rather a lot of planning infrastructure is assumed to be in place in the background of this scenario: an existing support infrastructure consisting of a social safety net, including a food voucher program; implicitly, a political apparatus which has produced sufficient social consensus to establish and resource humanitarian responses, and to resolve the attendant distributional choices to the point where they do not intrude upon the scenario; disaster response administrators with an awareness of their own data gaps, and a willingness to address them; there are local government organisations, schools and community health organisations. UNGP is a ‘decision-support platform’ for those at the helm of an existing development apparatus currently organised in a ‘planning’ mode, and this traditional apparatus is figured in the scenario as a condition of possibility of UNGP’s work.

Similarly, rather a lot of the existing sensory/knowledge architecture of development also features in this scenario as a condition of possibility of UNGP’s work. It is certainly true that UNGP is imagined as offering the possibility of a new sensory regime for development institutions: UNGP helps to create ‘a kind of global nervous system integrating across diverse information streams to allow leaders to detect, characterize and respond to fluctuations in human wellbeing’ (Kirkpatrick 2010). Specifically, it eclectically connects and integrates non-traditional information streams which are otherwise unavailable to decision-makers (talk radio, social media); overcomes artificial obstacles to visibility (jurisdictional boundaries); and helps decision-makers see new significance in the information which is already available to them. Yet, even in the idealised future painted in the scenario, UNGP also relies heavily on an existing metrological system. UNGP’s attention is triggered by movement in ‘UN food security monitoring indicators’—which themselves rely on background systems for measuring oil prices, average rainfall, and so on. There are resourced governmental teams trained in delivering household level surveys, and standing ready to deliver them. The international border turns out in the scenario not just to be an impediment to information flow, but also a device for measuring and visibilising transborder migration. UNGP, then, is not figured in this scenario as an alternative to any of this, but an add-on to it. As Kirkpatrick has elsewhere made clear: ‘Official statistics will continue to provide high-quality snapshots of progress that can be benchmarked … [b]ut increasingly, between those annual, bi-annual, or monthly updates, real-time data sources will provide valuable interim feedback and indicators’ (Anonymous 2014).

Yet, at the same time, there is an undeniable way in which this scenario is saturated with an implicit normative promise that UNGP (writ large, as a new platform and set of digital techniques for visibilising and responding to the world) can radically transform the conduct of development decision-making. On one side, the world painted in this scenario is one in which new sensory architectures transform decision-makers themselves, encouraging greater attentiveness on the part of decision-makers to real-time data about human wellbeing. Making people and their problems visible, in other words, elevates their policy salience, the possibilities of empathy with them, and the priority accorded to them. New sensory regimes also modify the temporality of decision-making, enabling faster response and learning cycles. Together, these encourage an ethos of adaptability and flexibility in decision-making structures. On the other side, the new regime of visibility is figured also as transforming local communities. UNGP’s sensing apparatus in this hypothetical scenario involves active interrogation of social space, and the enlistment of new sensors at community level. It mobilises existing actors as new parts of the existing sensory apparatus: local radio talkshow hosts, teachers, citizens themselves through continuous mobile surveys, all participate in the process of making the community visible to a governance apparatus.

The image of UNGP’s work, then is that of a connector, plugging in to existing development apparatuses, and attaching them to new sensory networks. But the act of connection also promises a dual transformation: on one hand sensitising decision-makers through new and enhanced regimes of visibility of the users of governance technologies, and on the other mobilising those users and beneficiaries to arrange themselves and make themselves visible to decision-makers. The larger promise is to engender new forms of connection between governors and population, precisely through the acts of rendering the unseen visible (Chandler 2017), enabling empathetic imagination, transmitting ethics of design thinking, and enabling popular participation in regimes of visibility. By describing UNGP as ‘supplementary’ to the existing apparatus of development planning, we do not mean to deny this transformative promise. Rather, we are arguing that this transformative promise is imagined to operate in the manner of a modular attachment to an existing apparatus–rather than as an autonomous alternative to it.

Financial Inclusion

In this section, we extend these reflections through an examination of one strand of the work of PLJ from 2016 to the present. PLJ has a large and diverse portfolio–we counted 111 projects since 2015, on topics ranging from disaster management (11) and environmental protection (11), to physical infrastructure (15) and agricultural productivity (5). For this paper we have chosen to focus on a series of projects on the theme of financial inclusion. These projects seem particularly promising as a place to begin, given our broader preoccupations. ince the aftermath of the global financial crisis in 2008, financial inclusion for the ‘unbanked’ or ‘underbanked’ has been established as a global priority, around which a diverse array of institutions, forums, and programmes have organised themselves. The G20, APEC, World Bank, Asian Development Bank, BIS and FATF all have active work programmes on the topic, new regulatory networks such as the Alliance for Financial Inclusion have emerged, as have a variety of metrological projects to measure the extent of the problem and monitor progress towards targets, such as the World Bank’s Findex, the IMF’s Financial Access Survey and the privately funded Intermedia Financial Inclusion Insights, and GSMA Mobile Money Metrics. The Indonesian government has had its own national financial inclusion strategy since September 2016 (renewed and replaced in December 2020), co-ordinated by the National Council on Financial Inclusion, with an ambitious initial target of covering 75% of the adult population served by formal financial institutions by 2019 (OECD 2018, p. 147). At the same time, the rapid growth of new technology-enabled ways of delivering financial services–mobile money, branchless banking, agent banking–has given rise both to optimism about the possibility rapid progress towards financial inclusion goals, as well as new, and relatively unanalysed, sources of consumer data. Financial inclusion, then, is in many respects a particularly likely site for the sort of work the UNGP does, and an interesting testbed for some of its innovations.

PLJ has conducted a number of projects on the theme of financial inclusion. From 2016, it partnered with the UN Capital Development Fund (UNCDF), on a project analysing customer data–mainly savings and loan records of customers covering 2010–2015–provided by four financial service providers operating in Cambodia (UNGP 2018b). The aim of this project was to understand customers’ ‘journeys’ better, to help diagnose the reason why usage of formal financial services remains so low amongst poorer and more marginalised groupings within this region. Another project in 2018 focussed on the banking practices of early fintech adopters amongst Indonesian micro-enterprises–street food vendors, small shop owners, and so on–with a view to understanding how and why some micro-enterprises, despite considerable obstacles, had begun to use such services (Maesy et al. 2018). This led subsequently to a Challenge Fund competition for Indonesian FinTech innovators. The same year, PLJ facilitated a ‘data dive’ focused on ‘measuring financial awareness and financial literacy across Indonesia based on social media data; measuring financial access based on information regarding both financial institutions and non-financial institutions; modelling gender-based differences in financial inclusion; and assessing the impact of digital opportunity on financial inclusion’ (UNGP 2018c). In 2018–2019, another project conducted in partnership the Secretariat of the National Council for Financial Inclusion (DNKI) and Women’s World Banking involved building an interactive geospatial mapping tool to visualise the location of financial access points in selected regions of Indonesia (UNGP, 2019). Finally, PLJ’s #TabunginAja (#JustSaveIt) project was conducted in Indonesia over 2018–2020. This project involved sending series of targeted social media messages to banking agents, asking them to encourage customers to save their loose change, and evaluating the results. It was conducted in partnership with the DNKI Secretariat, and the Behavioural Insights Team (UNGP 2020). Alongside these PLJ projects, it is also worth noting a 2017 project undertaken by its sister lab in Kampala, investigating the potential uses of customer data derived from the rapidly growing mobile money sector in Uganda and across the African continent (UNGP 2017).

Across these projects, a common theme is the desire to ‘apply human-centred design and behavioural insights to develop and trial innovative approaches to improve financial inclusion’ (UNGP 2020). One key move is to visibilise the ‘user’–where the ‘user’ is understood in this context as simultaneously a (potential) consumer of fintech services, and a citizen beneficiary of financial inclusion policies. ‘While financial inclusion efforts should be pioneered by higher-level policymaking’, one project report notes, ‘it must also be supported with a clear understanding of the realities of the target users’ (UNGP 2018b). In the Cambodian project, this understanding emerged by way of the interrogation of commercial sources of ‘big data’: PLJ analysed customer data over 2010–2016, covering 2.3 million customers and 6.5 million savings and loan records, with a view to getting a more granular understanding of who tends to engage with formal financial services, for what purpose, and for how long.

The microenterprise project also focussed on understanding ‘user experiences’ better, but adopted a different method:

We employed a set of methods under one defining methodology of human-centred design, which refers to a problem solving approach that involves researchers empathising with the people, or users, for whom the service is intended. The aim of this approach is to understand the needs, desires, pain points and experiences of the respondents. (UNGP 2018b)

Interviews were conducted with 116 respondent micro-merchants, most of whom were women, from five areas of Java: Jakarta, Bekasi, Sukabumi, Ciseeng, and Banyumas. From of these interviews, the researchers identified eight ‘key insights’ into the ‘behaviours, thoughts and emotions’ of these micro-merchants in relation to fintech and financial managements: ‘it’s all about convenience, not about risks or costs’; ‘micro-merchants plan for the short term and think that financial services are only for the long term’; ‘agents and fintech users view each other as people, not functions’; ‘social norms influence decision-making’; ‘agents and users use only oral communication’; and so on. They further identified four enabling factors that facilitated early adoption of fintech amongst micro-enterprises: ‘trusted peers, appropriate use case, accessibility, and affordability’ (UNGP 2018b).

The methods of data collection and analytic work of PLJ in these projects, then, works (in aspiration at least) to enable a particular kind of empathetic engagement with the user of fintech products, on the part of both policy-makers and commercial service providers. It is a kind of empathy expressed and enacted through the process of policy and product design, in which the policy/product is reformatted for a newly visibilised sociality embodied in the user experience. In the microenterprise study, this was made clear through the articulation of four design principles– ‘designing for accessibility, designing for trust, designing for appropriate use case, and designing for affordability’–but the larger lesson is offered in generally applicable terms. The uptake of fintech services amongst micromerchants, the study concludes, is determined less by the technological features or products and more by the human relationships around them, and as a result ‘a policy approach that takes into account the social aspect of finance and the unbanked community’s reliance on their peers is required to realise the potential of fintech for the financial inclusion of this cohort’ (UNGP 2018b). At the same time, we would also observe that this empathetic engagement is conditioned in important ways by the policy and technical apparatus it is offered to disrupt. For one thing, those aspects of the micromerchants’ experiences which are made visible–and thereby constructed as relevant needs, emotions or behaviours–are those which emerge from their interaction with existing financial technologies. Moreover, PLJ’s practices of visibilisation are evidently mediated by the ways in which the problem of ‘financial inclusion’ has already been made visible, and measured. Project reports consistently draw on existing financial inclusion indices and maps to define the policy problem, and everywhere telegraph their relation to, and contribution to, larger global financial inclusion projects. The result is a mode of visibilisation of the user which is attentive to some matters, but not others. ‘Throughout the research, we uncovered various mental barriers that hamper micro merchants’ access to financial services; the fintech adoption journey of several micro merchants; and the enabling factors that have encouraged these micro merchants to use fintech’ (UNGP 2018a, p. 34). As a result of the study, then, we know more about what makes the use of fintech services a valuable or pleasant experience for micro-merchants, for example, but we do not know if a policy designed to improve access to fintech services feels to them like a solution to a problem that they might not realise they had. It is not just a newly visibilised user which PLJ’s mode of working seeks to offer. It is also, and perhaps more importantly, the sensibility, practices and aspirations of design thinking itself. The report of the #TabunginAja (#JustSaveIt) social media campaign, is explicit in this respect. As it happens, the direct outcomes of this experimental intervention were not particularly significant: few agents changed their messages to customers as a result of the campaign, and there was no evidence of increased savings rates. However, the report of the project emphasises the core principles of human-centred design which were reflected in the design of the project, and which were transmitted to S-DNKI staff as a result of the project. Regardless of the outcomes of this particular technical experiment, it notes, the core implications of PLJ’s work for the policy-design process remained: ‘design interventions to encourage habit formation’; ‘acknowledge the human factor’; ‘test before implementing at scale’; ‘design interventions that close the gap between responsiveness and action’, and so on (UNGP 2020, p. 4). This–that is to say, an appreciation of human-centred design, and a familiarity with its skillset–is ultimately sold as the core output of the project.

In that project, the vehicle for transmitting design thinking to policy-makers appears to have been the report itself, along with associated presentations. But this was interestingly different in the financial access point mapping project. The output of this project was a set of tech objects: a prototype database, and interactive geospatial mapping tool, and (in a promised future) a public-facing web interface and app. The interactive map was built based on data, mostly from official sources, relating to two areas (Yogyakarta City, Yogyakarta and Bima District, West Nusa Tenggara). The access points mapped included ATMs, banks of various kinds, banking agents, post offices, TCash points, among others, and these were mapped against contextual data on socioeconomic and infrastructure indicators. The prototype ‘interactive visualisation dashboard’, the primary output of this project, offers the same promise of greater visibility as noted earlier: ‘a financial access map with information down to the village level [which] has the potential to help policymakers make informed decisions that are attuned with the context of both urban and rural areas’ (UNGP 2019). But it is also designed in a way which encourages, to some degree, further experimentation (‘tinkering’, of a kind) on the part of the policymaker-user. It contains, for example, analytic layers allowing users to see very quickly the number of access points per capital of adult population, driving times to the nearest access point, etc., simply by checking different boxes. More importantly, it was designed with a ‘modular orientation to accommodate additional data sets’ (UNGP 2019). Data from more regions could of course be added to the map, but the designers more significantly also imagined the possibility of an open-ended range of additional analytic layers which policy-makers might in the future find helpful: ‘[t]here’s also the possibility of adding other data insight layers based on poverty, unemployment, electricity infrastructure, internet signal strength, distance between branches and agents, literacy data, and gender analysis’ (UNGP 2019).

What is significant for our purposes here is the way that the affordances of the tech object–the map and its various interfaces–are imagined to act as vehicles for prototyping, user-oriented, experimental design sensibility. The designed openness of the map’s architecture (new data sources, new analytic layers, both possible and planned) is imagined to encourage an exploratory and experimental mindset on part of users/decision-makers. The customisable visual interface affords rapid changes of scale in visibility–encouraging granularity, drilling down as well as up. Its design is modular, in the sense that it is offered as an optional enhancement of an existing policy planning apparatus–albeit one with a transformational promise–which seems to be as easily disconnected or discarded as it is added. Moreover, the technical artefact of the map has the benefit of being compatible on a universal basis with essentially any development project/problem–its normativity works, in other words, at the level of system and architecture, not at the level of goal, outcome or political priority. More broadly then, the ‘supplementary’ character of UNGP’s work conditions its transformative effects, in part by keeping them indirect and implicit, even as the transformative promise of UNGP’s vision conditions the kinds of supplementary enhancement it offers to existing development apparatuses.

Modularity

Our exploration of PLJ’s financial inclusion work offers a contrast with the bombastic scenario planning of the earlier section. These projects are modest, of limited impact, and emerge less directly from the urgency of crisis. Yet across the two sections, some core observations about PLJ’s work hold true.

First, PLJ works with, and within, existing metrological and governance apparatuses, from Kirkpatrick’s invocation of food security indicators as a condition precedent for UNGP activity, to PLJ’s use of existing financial inclusion indices and maps to define the problem in the Cambodian project. The projects themselves are made interpretable in part through reference to their contribution to progress on SDG indicators. Existing arrangements are in this important sense a condition of possibility of the sort of development practice that PLJ seeks to instantiate. Second, just as in the hypothetical scenario, PLJ products are offered as an enhancement of existing regimes of measurement and visibilisation. The Financial Access Map is supposed to offer greater granularity of vision, with a view to more informed decision-making. There is a particular focus on enhancing the visibility of the user, whether the early adopter of fintech products in the microenterprises project, or school-aged girls in the disaster scenario. Third, PLJ doesn’t just take these existing arrangements for granted, but also promises to disrupt, transform, and re-engineer them in the service of a design-oriented approach to decision-making, as explicitly set out in the #TabunginAja project. What, then, can we conclude about the kind of work the UNGP/PLJ’s projects do on traditional development apparatuses? As foreshadowed earlier, we propose to think of UNGP/PLJ’s work in the manner of a ‘modular attachment’. We intend this metaphor to capture at least three characteristics of the work of UNGP/PLJ which emerge for us from the material and projects examined in this paper.

First, modularity is in part intended to evoke the supplementary character of PLJ’s work. PLJ’s style is best understood less an alternative to planning, more a set of techniques for disrupting and enhancing an existing planning regime, and its transformative effects are always made operational in the context of that relation of enhancement and disruption. Modularity in this sense evokes its everyday use in the context of tech–think, perhaps, of the swappable attachments to a power tool that might transform it into a screwdriver, or a drill (Boyce Stone 1997, p. 42); or an attachment to a mobile phone which turns it into a virtual reality headset–where the attachment works through and by virtue of the modalities of its connection to existing hard- or software, and where the affordances, properties and function of the combination are radically different from either of the elements. Thinking in terms of modularity thus invites us to think at the level of forms, connections, and affordances–and it does for PLJ too, as one of Johns’ respondents notes in her contribution to this collection. It draws our attention to the multiple ways in which the work of PLJ brings both styles of development work– ‘planning’ and ‘prototyping’–into relation, instead of focussing our attention primarily on drawing distinctions between the two, or positing a transition from one to another.

Second, modularity is also intended to capture the customisable and provisional quality of the artefacts and relations which PLJ produces. Modular attachments are designed to be removable, updatable, swappable. Though they work through attachment, they always and necessarily enable the possibility of easy disattachment. A drill becomes a screwdriver; a VR headset attachment can be swapped out for a microscope one. In the same way, UN Global Pulse does indeed seek to piece together a new sociotechnical apparatus for the visibilisation of ‘users’ in the development apparatus, but this apparatus is by design oriented towards its own ongoing revision and customisation–indeed, that is a sign of its success. We saw, for example, the way in which the Financial Access Map was produced to be customisable–to enable and encourage the inputting of new data sources, new kinds of stakeholder workshops, and/or new forms of empathetic understanding of stakeholders. But also more generally, the technological and other artefacts produced by PLJ relate to the broader development apparatuses in the mode of attachment and disattachment. That is, these supplements are simultaneously engaged in the work of pragmatic association and alliance-building with existing development apparatuses; and of dissociating itself from the particularities of those same apparatuses. In this sense, then, modularity draws our attention to the central role of ‘designed-in provisionality’ plays in new development styles, and the social/political work that it does.

Third, thinking in terms of modularity draws our attention to the systems architecture, and formal transformations, which may be required for modularity to work. (A virtual reality attachment cannot be used with just any phone: the hardware must be designed to accept the attachment; protocols of communication must be developed; a connection or adaptor may be needed; and so on.) Thus, the prototype itself might operate at the level of module: a thing that can be attached and disattached. The prototype might also operate at the level of connector, in the sense that it might attach to the development apparatus, and then allow different modules to feed new data or empathetic relationships into the apparatus. And the prototype might further operate at the level of architecture: aiming to transform the apparatus it encounters or connects with–its forms, its mindsets, its logics–into one well-suited to operating in a modular fashion. There is, after all, a great deal of work which needs to be done on existing development apparatuses–at the level of technical systems, decision-making processes, and indeed decision-maker sensibilities–to make them interoperable with UNGP, that is to say, able to receive and use the enhancements offered by UNGP and its technologies.

What are some of the political stakes of the modular nature of PLJ’s work, and to what specific lines of critique might thinking in ‘modular’ terms give rise? In claiming that PLJ might be understood as producing modular attachments, we do not want to suggest that PLJ merely reinforces existing development practices–although it might (c.f. Irani 2019). Rather, we suspect that PLJ might work to prefigure and enact transformations of the organisational forms of development apparatuses–such that they operate in a modular fashion, incorporating and discarding different attachments as needed.

Johns (2019) encourages us to problematize the purchase of a received critical repertoire–concerned with unveiling and unmasking power relations behind development practices–over ‘prototyping’. If we are arguing that PLJ’s work should also be understood in relationship to ‘planning’, it may be tempting to return to that repertoire to understand the stakes of PLJ’s work: how are stakeholders identified, problems defined, progress imagined? However, we think a different set of questions offer themselves when we interrogate modularity specifically.

First, there is a set of questions around interoperability. As just noted, modular forms never simply plug-in to an existing architecture without both imaginative and practical preparatory work, all of which have political consequences. How then do our different actors imagine a development apparatus has to be remade to make it interoperable with modular forms? How might we trace the effects of the long, hard, resource-intensive work of planning and infrastructure-building which has to happen if PLJ-style prototyping is to work modularly as intended? What actually happens when this is tried?

The Financial Access Map is instructive here: it was constructed to enable decision-makers to add new layers of data as they see fit. The openness of the architecture facilitates the adoption and discarding of means of visibilisation; and, in doing so, encourages an exploratory and experimental mindset on part of decision-makers. At the same time, the evidence is that this digital artefact has–until recently–had a relatively inactive life since its original production, in part on account of its incomplete and (now) out-of-date data. A project is currently underway, with the financial support of the Asian Development Bank, to expand the features of the database, to create a support infrastructure around it, and to integrate it more fully into the work of the DNKI Secretariat.

In this respect, the trajectory of the Financial Access Point Map–an imaginative and experimental prototype produced during a short-duration project, but without clear plans for subsequent support, and an uncertain post-project afterlife–is characteristic of a number of PLJ’s projects, and has recently led to a reassessment by PLJ of its ways of working. After a period during which PLJ took on a very high number of projects simultaneously, in part with a view to experimenting with a wide range of innovative tools and techniques, it has begun to focus more attention on the afterlife of its innovations, and of the prototypes it has built. This involves taking on fewer projects, but spending more time and resources on the difficult and time-consuming work of helping to build softer architecture of training, human resources, support etc. to help new processes and prototypes get embedded, used, integrated, and to have the impact that they are intended to have, and to create sustainable systems within decision-making structures.

There is a broader lesson here. The Map is an exemplary project, in the sense of enacting the transformations it seeks to realise more broadly. However, we see the transformation not as a shift from planning to prototype. Rather, the operationalisation of a modular intervention such as the Map can lead to a reformatting of the institution or development apparatus to which it is attached. The Map can be tagged on, and disconnected/discarded, from existing development apparatuses. New analytical layers can be added, encouraging experimentation, tinkering–and perhaps jettisoning. This is of a kind with a broader vision for UNGP articulated by Kirkpatrick back in 2010: ‘we’re looking to design an open standards-based plug-in architecture for the platform that supports integration of a wide range of useful existing applications and services that provide capabilities such as mapping, social networking, analysis, visualization and collaboration.’ (Kirkpatrick 2010)

The private sector, in PLJ’s telling, may already be amenable to such an architecture. In the microenterprise project, for example, ‘rather than recommending products or service ideas’, PLJ ‘chose to translate [their] insights into a set of practical design principles’, since such principles can already be ‘applied by fintech companies as design directives in developing and testing’, applying and disapplying, ‘a variety of solutions for micro enterprises in Indonesia’ (UNGP 2018a, p. 34). The challenge for PLJ is to help the public sector do the same, sustainably and at scale.

Second, and more briefly, there is a set of questions around the forms and location of reflexivity. It is quite possible to see the work of PLJ as inaugurating a newly empathetic and reflexive form of development governance–there is much of PLJ’s own literature which paints its work in this way. In our view however, it may be better to understand its work as modifying or relocating existing forms and practices of reflexivity, engendering reflexivity and empathy within modular forms–such that they may be substituted with new practices of empathy from another module (for example, from stakeholder consultation to applied ethnography). Thinking modularly, then, raises a set of questions about the transformation of practices of empathy and reflexivity in development governance. What are the limits of these particular practices of reflexivity? What do they do to other forms and mechanisms of reflexivity already present in existing development governance–for example, monitoring and evaluation cultures and practices? How are new and old modules of reflexivity set in relation, and how do they condition, critique, and justify one another? How and with what effects are tasks and functions distributed and redistributed between them?

Third, and finally, there is a set of questions around provisionality. We have said that the sort of work that UNGP does can be characterised, following Johns and others, as the construction of a new architecture for development work, and that this architecture is placed in the service of reflexive and user-oriented style of development decision-making as ‘design’. But this new architecture is not in principle attached to any particular sources of data or empathy, and indeed is designed to enable and facilitate their constant updating, revision, aggregation and replacement.

One consequence of this, for us, is that the politics of this new architecture is harder to find. Others have sought to find this politics in the particular sources (Twitter, satellite imagery, etc.) which are used in one project or another, and of course the structural politics of data sources is hugely important. But the picture is complicated by the designed-in quality of the architecture which ensures that it is always to some extent only opportunistically and provisionally attached to particular sources, and with the goal of always being open to looking anew and differently.

We suspect that the politics of this apparatus might be found in the ways in which it produces, justifies, and sustains this enduring provisionality. For example, we might see it in the ways in which the movement between and layering of data sources–or at least the possibility of such movement and layering–is produced; or in the form and process of the constant search for new data supplements.

Coda

The Selamat Datang monument was built in 1962 to mark the hosting of the Asian Games in Jakarta. General Sukarno made it the center of an urban transformation effort. It was flanked by the impressive new Hotel Indonesia, also built as part of the Asian Games; and would welcome traffic from what was then the newly-refurbished international airport. Sukarno intended these ‘monumental’ projects not only to change the character of the city, but produce nationalist sentiment.

Over the years, the space has been reinterpreted. It became a place of public protest (or ‘protesters, vendors, prostitutes, homeless people and hoodlums’, depending on who you ask: Permanasari 2008, p.10). In 2001, under the guise of aesthetic improvement, the governor of Jakarta, General Sutiyoso, surrounded the statue and fountain with ‘a deep pool at the centre surrounded by an overflow area that covers all but a small margin of the public space’ (Permanasari 2008, p.10)–thereby disrupting the place’s protest potential. Ending at the crossroads where Johns begins, then, we find a place where transformative projects come and go, in an effort to transform the broader landscape that surrounds them.

References

Anonymous. 2014. A Conversation with Robert Kirkpatrick, Director of United Nations Global Pulse. The SAIS Review of International Affairs 34 (1): 3–8.

Armitage, Alice. 2016. Gaugin, darwin and design thinking: a solution to the impasse between innovation and regulation. UC Hastings Research Paper No. 235.

Burn-Murdoch, John. 2012. Big data: what is it and how can it help? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2012/oct/26/big-data-what-is-it-examples. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Chandler, David. 2017. Securing the anthropocene? international policy experiments in digital hacktivism: a case study of jakarta. Security Dialogue 48 (2): 113–130.

Chandler, David. 2018. Ontopolitics in the anthropocene. Abingdon: Routledge.

Duffield, Mark. 2019. Post-humanitarianism: governing precarity through adaptive design. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs 1 (1): 15–27.

Hidalgo-Sanchis, Paula. 2021. UN Global pulse: a UN innovation initiative with a multiplier effect. In Data Science for Social Good, ed. Massimo Lapucci and Ciro Cattuto, 29–40. Cham: Springer.

Humanitarian Policy Group. 2018. A design experiment: imagining alternative humanitarian action. London: ODI.

Irani, Lily. 2019. Chasing innovation: making entrepreneurial citizens in modern India. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jerven, Morten. 2013. Poor numbers: how we are misled by African development statistics and what to do about it. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Johns, Fleur. 2019. From planning to prototypes: new ways of seeing like a state. Modern Law Review 82 (5): 833–863.

Johns, Fleur. 2021. Governance by Data. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 17: 53–71.

Johns, Fleur, and Caroline Compton. 2022. Data jurisdictions and rival regimes of algorithmic governance. Regulation and Governance 16 (1): 63–84.

Kirkpatrick, Robert, and Felicia Vacarelu. 2019. A decade of leveraging big data for sustainable development. UN Chronicle 5594: 26–31, https://www.un.org/en/un-chronicle/decade-leveraging-big-data-sustainable-development. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Kirkpatrick, Robert. 2010. Self-assembly required: a real-time platform for global pulse. UN Global Pulse, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/2010/11/self-assembly-required-a-real-time-platform-for-global-pulse/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Lohr, Steve. 2013. Searching big data for ‘digital smoke signals. New York Times, https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/08/technology/development-groups-tap-big-data-to-direct-humanitarian-aid.html?_r=0. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Maesy, Angelina, Nisa Fachry, Dalia Kuwatly and Rico Setiawan. 2018. Banking on fintech: financial inclusion for micro enterprises in Indonesia. Pulse Lab Jakarta. https://www.unglobalpulse.org/document/banking-on-fintech-financial-inclusion-for-micro-enterprises-in-indonesia/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Mann, L. 2018. Left to other peoples’ devices? a political economy perspective on the big data revolution in development. Development and Change 49 (1): 3–36.

McGann, Michael, Emma Blomkamp, and Jenny M. Lewis. 2018. The rise of public sector innovation labs: experiments in design thinking for policy. Policy Sciences 51 (3): 249–267.

Mintrom, Michael, and Joannah Luetjens. 2016. Design thinking in policymaking processes: opportunities and challenges. Australian Journal of Public Administration 75 (3): 391–402.

Nielsen, René Clausen. 2010a. Global pulse: an open architecture for sustainable innovation. UN Global Pulse, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/2010a/11/global-pulse-an-open-architecture-for-sustainable-innovation/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Nielsen, René Clausen. 2010b. Notes from pulse camp 1.0: day one. UN Global Pulse, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/2010b/12/notes-from-pulse-camp-1-0-day-one/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Nielsen, René Clausen. 2010c. Notes from pulse camp 1.0: day two, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/2010c/12/notes-from-pulse-camp-1-0-day-two/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Nielsen, René Clausen. 2010d. Notes from pulse camp 1.0: day three. https://www.unglobalpulse.org/2010d/12/notes-from-pulse-camp-1-0-day-three/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

OECD. 2015. The innovation imperative in the public sector: Setting an agenda for action. Paris: OECD.

OECD. 2018. Economic outlook for Southeast Asia, China and India 2019: towards smart urban transportation. Paris: OECD.

Olejniczak, Karol, Sylwia Borkowska-Waszak, Anna Domaradzka-Widła, and Yaerin Park. 2020. Policy labs: The next frontier of policy design and evaluation? Policy and Politics 48 (1): 89–110.

Pellini, Arnaldo, Diastika Rahwidiati, and George Hodge. 2018. Data innovation for policymaking in Indonesia. In Knowledge, Politics and Policymaking in Indonesia, eds. Arnaldo Pellini, Budiati Prasetiamartati, Kharisma Priyo Nugroho, Elisabeth Jackson, and Fred Carden, 89–108. Singapore: Springer.

Permanasari, Eka. 2008. When currency speaks for the state: discourse on indonesian bill notes and stamps under three postcolonial regimes. Proceedings of the XXVth International Conference of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand.

Ramalingam, Ben, Miguel Laric and John Primrose. 2014. From best practice to best fit: understanding and navigating wicked problems in international development." London: Overseas Development Institute (2014): 1-44.

Boyce Stone, Robert. 1997. Towards a theory of modular design. PhD Thesis, University of Texas at Austin.

Taylor, Linnet, and Dennis Broeders. 2015. In the name of development: power, profit and the datafication of the global south. Geoforum 64: 229–237.

Taylor, Linnet, and Ralph Schroeder. 2014. Is bigger better? the emergence of big data as a tool for international development policy. GeoJournal 80 (4): 503–518.

Torjman, Lisa. 2012. Labs: Designing the future. MaRS Discovery District Report, https://www.marsdd.com/research-and-insights/labs-designing-the-future. Accessed 17 June 2022.

UN Global Pulse. 2009. About UN Global Pulse. https://www.unglobalpulse.org/about/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

UN Global Pulse. 2017. Exploring the potential of mobile money transactions to inform policy, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/project/exploring-the-potential-of-mobile-money-transactions-to-inform-policy-3/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

UN Global Pulse. 2018a. Annual Report 2018a: Shaping Development Practice & Humanitarian Action for the Digital Age, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/pulse-lab-jakarta-annual-report-2018a.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2022.

UN Global Pulse. 2018b. Big data for financial inclusion, examining the customer journey, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/Project-Brief-Big-Data-for-Financial-Inclusion-Customer-Journey.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2022.

UN Global Pulse. 2018c. Examining customer journeys at financial institutions in cambodia: Using big data to advance women’s financial inclusion, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/wp-content/uploads/2018c/07/Examinining_Customer_Journey_at_Financial_Institutions_in_Cambodia.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2022.

UN Global Pulse. 2019. Mapping financial services points across Indonesia, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/project/mapping-financial-services-points-across-indonesia/. Accessed 17 June 2022.

UN Global Pulse. 2020. #JustSaveIt - Encouraging usage of agent-based bank accounts to improve financial inclusion, project report, https://www.unglobalpulse.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/English-Full-report-D-SNKI-TabunginAja-1.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Understanding and navigating wicked problems in international development. ODI Working Paper, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a089b3ed915d622c000363/61065-BestPracticetoBestFit.pdf. Accessed 17 June 2022.

World Bank. 2016. Big data innovation challenge: pioneering approaches to data-driven development. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. 2014. Central America: Big data in action for development. Washington, DC: World Bank, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21325. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dimitri van den Meerssche and Geoff Gordon for the opportunity to contribute to the symposium, and for their engagement and comments throughout. Thanks also go to Maesy Angelina, Vitasari Anggraeni, Stephen Humphreys, Andrea Leiter, Marie-Catherine Petersmann, Sugeng Prabowo, Gavin Sullivan, Sofia Stolk, and the peer reviewers for their careful and thoughtful feedback. Robert Holland provided detailed research assistance. The research was supported by funding from Edinburgh Law School. Errors and omissions remain our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Desai, D., Lang, A. From Mock-Up to Module: Development Practice between Planning and Prototype. Law Critique 33, 299–318 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10978-022-09326-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10978-022-09326-1