Abstract

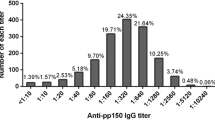

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) shedding has been extensively investigated in newborns and in young children, however, much less is known about it in immunocompetent adults. Shedding of HCMV was investigated in saliva, vaginal secretions and urine of pregnant women experiencing primary infection along with the development of the HCMV-specific immune response. Thirty-three pregnant women shed HCMV DNA in peripheral biological fluids at least until one year after onset of infection, while in blood HCMV DNA was cleared earlier. Significantly higher levels of viral load were found in vaginal secretions compared to saliva and urine. All subjects examined two years after the onset of infection showed a high avidity index, with IgM persisting in 36% of women. Viral load in blood was directly correlated with levels of HCMV-specific IgM and inversely correlated with levels of IgG specific for the pentameric complex gH/gL/pUL128L; in addition, viral load in blood was inversely correlated with percentage of HCMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ expressing IL-7R (long-term memory, LTM) while viral load in biological fluids was inversely correlated with percentage of HCMV-specific CD4+ and CD8+ effector memory RA+(TEMRA). In conclusion, viral shedding during primary infection in pregnancy persists in peripheral biological fluids for at least one year and the development of both antibodies (including those directed toward the pentameric complex) and memory T cells are associated with viral clearance.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cannon MJ, Davis KF (2005) Washing our hands of the congenital cytomegalovirus disease epidemic. BMC Public Health 5:70. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-5-70

Kenneson A, Cannon MJ (2007) Review and meta-analysis of the epidemiology of congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection. Rev Med Virol 17(4):253–276. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.535

Lilleri D, Fornara C, Furione M, Zavattoni M, Revello MG, Gerna G (2007) Development of human cytomegalovirus-specific T cell immunity during primary infection of pregnant women and its correlation with virus transmission to the fetus. J Infect Dis 195(7):1062–1070. https://doi.org/10.1086/512245

Fornara C, Lilleri D, Revello MG, Furione M, Zavattoni M, Lenta E, Gerna G (2011) Kinetics of effector functions and phenotype of virus-specific and γδ T lymphocytes in primary human cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy. J Clin Immunol 31(6):1054–1064. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-011-9577-8

Lilleri D, Kabanova A, Revello MG et al (2013) Fetal human cytomegalovirus transmission correlates with delayed maternal antibodies to gH/gL/pUL128-130-131 complex during primary infection. PLoS ONE 8:e59863. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0059863

Mele F, Fornara C, Jarrossay D et al (2017) Phenotype and specificity of T cells in primary human cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy: IL-7Rpos long-term memory phenotype is associated with protection from vertical transmission. PLoS ONE 12:e0187731. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187731

Fornara C, Furione M, Zavaglio F, Arossa A, Spinillo A, Gerna G, Lilleri D (2021) Slow cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell differentiation: 10-year follow-up of primary infection in a small number of immunocompetent hosts. Eur J Immunol 51(1):253–256. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.202048772

Sinzger C, Digel M, Jahn G (2008) Cytomegalovirus cell tropism. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 325:63–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_4

Cannon MJ, Hyde TB, Schmid DS (2011) Review of cytomegalovirus shedding in bodily fluids and relevance to congenital cytomegalovirus infection. Rev Med Virol 21(4):240–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/rmv.695

Mayer BT, Matrajt L, Casper C et al (2016) Dynamics of persistent oral cytomegalovirus shedding during primary infection in ugandan infants. J Infect Dis 214(11):1735–1743. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiw442

Zanghellini F, Boppana SB, Emery VC, Griffiths PD, Pass RF (1999) Asymptomatic primary cytomegalovirus infection: virologic and immunologic features. J Infect Dis 180(3):702–707. https://doi.org/10.1086/314939

Tu W, Chen S, Sharp M et al (2004) Persistent and selective deficiency of CD4+ T cell immunity to cytomegalovirus in immunocompetent young children. J Immunol 172(5):3260–3267. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.172.5.3260

Revello MG, Furione M, Rognoni V, Arossa A, Gerna G (2014) Cytomegalovirus DNAemia in pregnant women. J Clin Virol 61(4):590–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2014.10.002

Sarasini A, Arossa A, Zavattoni M et al (2021) Pitfalls in the serological diagnosis of primary human cytomegalovirus infection in pregnancy due to different kinetics of IgM clearance and IgG avidity index maturation. Diagnostics 11(3):396. https://doi.org/10.3390/diagnostics11030396

Lilleri D, Gerna G, Furione M, Zavattoni M, Spinillo A (2016) Neutralizing and ELISA IgG antibodies to human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein complexes may help date the onset of primary infection in pregnancy. J Clin Virol 81:16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2016.05.007

Lozza L, Lilleri D, Percivalle E, Fornara C, Comolli G, Revello MG, Gerna G (2005) Simultaneous quantification of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells by a novel method using monocyte-derived HCMV-infected immature dendritic cells. Eur J Immunol 35(6):1795–1804. https://doi.org/10.1002/eji.200526023

Fornara C, Furione M, Arossa A, Gerna G, Lilleri D (2016) Comparative magnitude and kinetics of human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses in pregnant women with primary versus remote infection and in transmitting versus non-transmitting mothers: its utility for dating primary infection in pregnancy. J Med Virol 88(7):1238–1246. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.24449

Stowell JD, Mask K, Amin M et al (2014) Cross-sectional study of cytomegalovirus shedding and immunological markers among seropositive children and their mothers. BMC Infect Dis 14:568. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-014-0568-2

Dollard SC, Keyserling H, Radford K et al (2014) Cytomegalovirus viral and antibody correlates in young children. BMC Res Notes 7:776. https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-776

Barbosa NG, Yamamoto AY, Duarte G et al (2018) Cytomegalovirus shedding in seropositive pregnant women from a high-seroprevalence population: the Brazilian cytomegalovirus hearing and maternal secondary infection study. Clin Infect Dis 67(5):743–750. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciy166

Zelini P, d’Angelo P, De Cicco M et al (2021) Human cytomegalovirus non-primary infection during pregnancy: antibody response, risk factors and newborn outcome. Clin Microbiol Infect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2021.09.013

Ju D, Li XZ, Shi YF, Li Y, Guo LQ, Z hang Y, (2020) Cytomegalovirus shedding in seropositive healthy women of reproductive age in Tianjin. China Epidemiol Infect 148:e34. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268820000217

Coonrod D, Collier AC, Ashley R, DeRouen T, Corey L (1998) Association between cytomegalovirus seroconversion and upper genital tract infection among women attending a sexually transmitted disease clinic: a prospective study. J Infect Dis 177(5):1188–1193. https://doi.org/10.1086/515292

Zhang C, Pass RF (2004) Detection of cytomegalovirus infection during clinical trials of glycoprotein B vaccine. Vaccine 23(4):507–510. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.06.027

Steininger C, Kundi M, Kletzmayr J, Aberle SW, Popow-Kraupp T (2004) Antibody maturation and viremia after primary cytomegalovirus infection, in immunocompetent patients and kidney-transplant patients. J Infect Dis 190(11):1908–1912. https://doi.org/10.1086/424677

Revello MG, Lilleri D, Zavattoni M, Furione M, Genini E, Comolli G, Gerna G (2006) Lymphoproliferative response in primary human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection is delayed in HCMV transmitter mothers. J Infect Dis 193(2):269–276. https://doi.org/10.1086/498872

Forman MS, Vaidya D, Bolorunduro O, Diener-West M, Pass RF, Arav-Boger R (2017) Cytomegalovirus kinetics following primary infection in healthy women. J Infect Dis 215(10):1523–1526. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jix188

Delforge ML, Costa E, Brancart F et al (2017) Presence of Cytomegalovirus in urine and blood of pregnant women with primary infection might be associated with fetal infection. J Clin Virol 90:14–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2017.03.004

Fornara C, Cassaniti I, Zavattoni M et al (2017) Human cytomegalovirus-specific memory CD4+ T-cell response and its correlation with virus transmission to the fetus in pregnant women with primary infection. Clin Infect Dis 65(10):1659–1665. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix622

Zavattoni M, Furione M, Lanzarini P et al (2016) Monitoring of human cytomegalovirus DNAemia during primary infection in transmitter and non-transmitter mothers. J Clin Virol 82:89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2016.07.005

Schoenfisch AL, Dollard SC, Amin M et al (2011) Cytomegalovirus (CMV) shedding is highly correlated with markers of immunosuppression in CMV-seropositive women. J Med Microbiol 60(Pt 6):768–774. https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.027771-0

Lilleri D, Kabanova A, Lanzavecchia A, Gerna G (2012) Antibodies against neutralization epitopes of human cytomegalovirus gH/gL/pUL128-130-131 complex and virus spreading may correlate with virus control in vivo. J Clin Immunol 32(6):1324–1331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10875-012-9739-3

Tabata T, Petitt M, Fang-Hoover J et al (2019) Neutralizing monoclonal antibodies reduce human cytomegalovirus infection and spread in developing placentas. Vaccines 7(4):135. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines7040135

Choi KY, El-Hamdi NS, McGregor A (2019) Inclusion of the viral pentamer complex in a vaccine design greatly improves protection against congenital cytomegalovirus in the guinea pig model. J Virol 93(22):e01442-e1519. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01442-19

Jonjić S, Pavić I, Polić B, Crnković I, Lucin P, Koszinowski UH (1994) Antibodies are not essential for the resolution of primary cytomegalovirus infection but limit dissemination of recurrent virus. J Exp Med 179:1713–1717. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.179.5.1713

Gamadia LE, Remmerswaal EB, Weel JF, Bemelman F, van Lier RA, Ten Berge IJ (2003) Primary immune responses to human CMV: a critical role for IFN-gamma-producing CD4+ T cells in protection against CMV disease. Blood 101(7):2686–2692. https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2002-08-2502

Sester U, Gärtner BC, Wilkens H et al (2005) Differences in CMV-specific T-cell levels and long-term susceptibility to CMV infection after kidney, heart and lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 5(6):1483–1489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.00871.x

Gabanti E, Bruno F, Lilleri D et al (2014) Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells are both required for prevention of HCMV disease in seropositive solid-organ transplant recipients. PLoS ONE 9(8):e106044. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106044

Gabanti E, Lilleri D, Ripamonti F et al (2015) Reconstitution of human cytomegalovirus-specific CD4+ T Cells is critical for control of virus reactivation in hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients but does not prevent organ infection. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21(12):2192–2202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.08.002

Lilleri D, Zelini P, Fornara C et al (2018) Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-specific T cell but not neutralizing or IgG binding antibody responses to glycoprotein complexes gB, gHgLgO, and pUL128L correlate with protection against high HCMV viral load reactivation in solid-organ transplant recipients. J Med Virol 90(10):1620–1628. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.25225

Antoine P, Varner V, Carville A, Connole M, Marchant A, Kaur A (2014) Postnatal acquisition of primary rhesus cytomegalovirus infection is associated with prolonged virus shedding and impaired CD4+ T lymphocyte function. J Infect Dis 210(7):1090–1099. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiu215

Bialas KM, Tanaka T, Tran D et al (2015) Maternal CD4+ T cells protect against severe congenital cytomegalovirus disease in a novel nonhuman primate model of placental cytomegalovirus transmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(44):13645–13650. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1511526112

Redeker A, Remmerswaal EBM, van der Gracht ETI et al (2018) The contribution of cytomegalovirus infection to immune senescence is set by the infectious dose. Front Immunol 8:1953. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.01953

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Giuseppe Gerna for revision of the manuscript and helpful discussion; Valentina Marazzi and Stefania Piccini for collecting the samples.

Funding

This work was supported by Ministero della Salute, Ricerca Corrente [grant number 053618].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CF analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. FZ e Pd’A collected the data and performed the experiments. AS supervised the data on antibody response. MF and AA enrolled and followed the patients and provided clinical data. DL conceived the study and revised the study. FB and AS revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (P-20180075214). Informed consent was obtained from all partecipants included in the study.

Additional information

Communicated by Matthias J. Reddehase.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fornara, C., Zavaglio, F., Furione, M. et al. Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) long-term shedding and HCMV-specific immune response in pregnant women with primary HCMV infection. Med Microbiol Immunol 211, 249–260 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00430-022-00747-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00430-022-00747-4