Abstract

Background

Although religious involvement tends to be associated with improved mental health, additional work is needed to identify the specific aspects of religious practice that are associated with positive mental health outcomes. Our study advances the literature by investigating how two unique forms of religious social support are associated with mental health.

Purpose

We explore whether support received in religious settings from fellow congregants or religious leaders is associated with participants’ mental health. We address questions that are not only of interest to religion scholars, but that may also inform religious leaders and others whose work involves understanding connections between religious factors and psychological outcomes within religious communities.

Methods

We test several hypotheses using original data from the “Mental Health in Congregations Study (2017–2019)”, a survey of Christian and Jewish congregants from South Texas and the Washington DC area (N = 1882). Surveys were collected using both paper and online surveys and included an extensive battery of religious and mental health measures.

Results

Congregant support has more robust direct associations with mental health outcomes than faith leader support. Increased congregant support is significantly associated (p < 0.001) with fewer symptoms of psychological distress (β = − 0.168), anxiety (β = − 0.159), and anger (β = − 0.190), as well as greater life satisfaction (β = 0.269) and optimism (β = 0.283). However, faith leader support moderates these associations such that congregant support is associated with better mental health only in cases where faith leader support is also high. When leader support is low, congregant support and mental health are not associated.

Conclusions and Implications

At the conceptual level, our study adds to an extensive literature on the relationship between religious social support and mental health. Additionally, our work may provide important insights to religious leadership in terms of communications strategies, services, and resources that might enhance overall congregant mental health and well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Emile Durkheim was the publicly engaged classical social theorist who first recognized the unique role that religion plays in societies, particularly in its ability to provide moral grounding and social solidarity. This general conceptualization has stood the test of time and continues to be debated and expanded upon, inspiring various contemporary approaches from cultural analysis to semiotics (Alexander 1988; Lemert 1979). However, while it stands to reason that nineteenth century views on social phenomena were formed in reaction to set of specific historical events particular to the time, we might find ourselves asking if such questions bear any relevance to the current religious landscape.

We suggest that ideas from the classical canon can still be viewed through the lens of explanatory social science, and as a means of addressing contemporary issues and questions. To that end, the study of religion as a source of social support—whether that be solidarity through shared meanings or through specific institutional channels—continues to be a relevant area of scholarly consideration (Krause and Markides 1990; Krause et al. 1998; Krause 2002). Particularly in light of circumstances where persistent social inequalities and unequal distribution of community resources might require religious organizations to provide a substitute for dwindling social services, asking questions related to support emanating from religious communities seems quite relevant at both a scholarly and practical level (DeAngelis et al. 2019). It is at this juncture that the current study takes shape.

Our study draws from a strand of social support literature specifically focused on sources of support in religious settings (Ellison and George 1994; Krause et al. 2001). For our study, we explore the associations between religious social support and mental health outcomes among parishioners (Dunn and O'Brien 2009; Nooney and Woodrum 2002) and hope to contribute to the literature by highlighting social support that emanates from interactions with either fellow parishioners (congregant support) or from religious leaders (pastoral support). Subsequently, we ask three interrelated questions: (1) Is congregant support associated with parishioner mental health? (2) Is religious leader support associated with parishioner mental health? (3) Is there a multiplicative or interactive association between both forms of support and parishioner mental health?

We address these questions by examining an original data set comprised of congregants from two regions of the continental United States. The data are based on two community samples in South Texas and the District of Columbia where quantitative and qualitative data were collected. For this study, we will focus on survey responses to an original questionnaire that included an extensive battery of religion and mental health measures.

With this background in mind, the remaining sections of the paper will proceed as follows. First, we provide a review of literature on congregant and religious leader support in religious settings. We focus on work that has considered measures of mental health and well-being as outcome variables. Second, based on that literature, we develop a series of empirical hypotheses that we evaluate using survey data. We then provide an overview of our data, measures, and analytical strategies. We close with a discussion that places our findings within a broader scholarly context, while also proposing several implications for practitioners and others working in the area of religion and mental health. Our discussion also addresses study limitations and suggests avenues for future work in this area.

Literature and Hypotheses

Congregant Social Support and Mental Health

The early literature on social support focused on the beneficial consequences of immersion into networks of likeminded peers who could provide a set of stable rewards and other strategies for self-improvement. As described in one seminal article, “this kind of support could be related to overall well-being because it provides positive affect, a sense of predictability and stability in one's life situation, and a recognition of self-worth” (Cohen and Wills 1985: 311). Such formative studies informed subsequent work that has examined the mental health correlates of religious social support, indicating generally positive associations between religious support and enhanced mental health (Ellison and Levin 1998, George et al. 2002, Hill et al. 2021, Pargament et al. 2000, Taylor and Chatters 1988). Koenig (1997) found that regular churchgoers were about half as likely to report depressive symptoms when compared to individuals with lower levels of church attendance, while related work found that churchgoers with more access to congregational support reported improved health outcomes relative to their peers with less support (Brewer et al. 2015: 2228–2229). More recent empirical studies have provided additional evidence that religious social support is associated improved psychological functioning and self-reported quality of life (Acevedo et al. 2014; Chatters et al. 2015; Schieman et al. 2013; Levin 2010). Addtionally this, generally salutary relationship has been demosntarted using multpile methodological approaches and documented in both pure research settings as well as within applied, community-based and public health organizations (Chatters 2000).

There is also a substantial body of work that explores linkages between congregational support and mental health from a variety of contexts. Here we focus on several strands of congregational support literature have focused on how factors such as age, gender and race/ethnicity moderate the religion-mental health link. Krause and his colleagues have successfully operationalized multiple dimensions of congregational support, while focusing their numerous research programs on the impact of religious factors among aging and elderly populations (Krause 2002; Hayward and Krause 2013; Krause and Markides 1990). Kent (2020) has not only reinforced the idea that distinct measures of religion (e.g., attendance, prayer, Biblical literalism) show varied magnitude and directional relationships with mental health, but that these effects operate differently for men and women. McFarland (2010) has reported parallel findings among older adults.

Some of the earlier and most widely cited research in this area highlighted congregational support on mental health, with emphasis on differential effects based on race and ethnicity (Blaine and Crocker 1995; Ellison 1995). Using longitudinal survey data, Ellison et al. (2008) have shown the specific direct effects of church-based social support on mental health. Their findings indicate that congregational support may offset the effects of discrimination on psychological distress, so that individuals receiving support from fellow congregants experience lower levels of psychological distress, even when controlling for the presence/absence of discrimination experiences. Additionally, work in this area has expanded the scope of key research questions to include physical as well as psychological health among minority populations (Levin et al. 1995). And in a current review of the literature, Nguyen (2020) focuses on the intersections of age, race/ethnicity, and how measures of religiosity impact members of distinct groups in diverse ways throughout the life course.

One possible explanation for the link between social support and positive well-being among religious individuals is the development of a specific form of religious social capital within religious communities (Ellison and Levin 1998; Lim and Putnam 2010). Religious organizations may foster feelings of belonging and togetherness which, in turn, enhance individual well-being. Ellison, for instance, has drawn from principles in social psychology and discussed ways that affirming self-conceptions based on others’ positive perceptions, are often expressed in religious settings (Ellison 1993). These “positive reflected appraisals” from fellow congregants may serve as a psychosocial mechanism that fosters feelings of high self-esteem, enhances overall mental health and that may mitigate against the noxious effects of everyday stress on psychological well-being (Bradshaw and Ellison 2010). Feeney and Collins (2015) find that people are more likely to thrive, prosper and cope with adversity when they are embedded in a network of responsive relationships that establish a secure base of support. They contend that the aspects of social relationships that support human thriving go beyond the notion of a secure base (Feeney and Collins, 2015: 3).

In our view, religious organizations may provide an institutional basis for the development of such relationship ties. Indeed, as one extended review of the literature has shown, multiple studies using both cross-sectional and longitudinal data have shown that many religious individuals draw on religious belief to enhance their own feelings of resiliency and security which, in turn, fosters positive psychological outcomes (Cherniak et al. 2020). Congregations provide a space where individuals are immersed in networks of like-minded peers who provide comfort in times of distress and who may also impart messages of affirmation leading to a higher sense of personal worth and self-esteem (Sherkat and Reed 1992). Likewise, messages of affirmation may be partnered with specific life skills and other strategies that could positively impact mental health outcomes (Vishkin et al. 2014). In a similar vein, congregational associations may also foster healthy coping behaviors in times of personal stress (Park et al. 2018). Fellow congregants often make themselves available and when connected with institutional programming such as religious study groups, recreational activities and other faith-based outings, it is quite plausible that regular interaction in such activities may enhance overall well-being.

Throughout this review of previous literature, we cite multiple studies showing empirical linkages between religion and improved psychological functioning (for comprehensive recent overviews see, Rosmarin and Koenig 2020; Koenig 2018). However, the literature is less clear as to the specific aspects of religious practice associated with these positive mental health outcomes (Pargament and Maton, 2000). One area we suggest is in need of further elaboration has to do with two central dimensions of religious support. While above we have focused primarily on scholarship focused on support from immersion in religious networks and resource provision from like-minded peers, there is little accumulated scholarship exploring the effects of pastoral support on congregant psychological well-being. This is surprising given that worshipers increasingly rely on support from their pastors (Bradbury, 2004; Cahill et al., 2014). And in an emerging area of inquiry, scholars are beginning to assess the role that clergy played in assisting others during the COVID-19 pandemic (Shelton et al. 2021; Snowden 2021). We next turn to this work and assess the role of faith leaders in support provision, with emphasis on mental health and well-being.

Faith Leaders and Pastoral Support

Examining pastoral care in Black Churches in 1979, Edward Wimberly argued that pastoral care—when understood as a set of faith-based resources mobilized to assist church members in times of crisis—defines one key supportive feature of a given church and establishes a vital relationship between pastors and their congregation (Wimberly 1979: 22, 74, 83). Immersion into networks of meaningful relationships with fellow congregants leads to interactions that might foster feelings of self-worth, secure attachments, and other forms of socioemotional support that, in turn, may influence a host of positive psychological outcomes. Following from Wimberly’s early classic study, here we redirect our focus to the effects of religious social support that is based on one-on-one relationships, particularly when that support stems from interactions with religious leaders. As has been argued, individual support acts as a catalyst for personal development, allowing a person to explore their social environment through play, work with others, educational experiences and other “excursions into the world” (Feeney and Collins, 2015: 3). As with the forms of collective support discussed above, individual-level, relational support may also act as a catalyst for improved psychological health and personal well-being (Feeney and Collins 2015).

In comparison to research on congregational support and mental health, it is fair to say that there is less accumulated scholarship that explores linkages between psychological well-being and support that congregants receive directly from their religious leaders. However, several key studies have shown insightful associations and promising avenues for continuing investigation. Continuing with their intersectional research agenda that explores religion, race, and mental health, Taylor and his co-authors (Taylor et al. 2000) provide a comprehensive review of published studies that highlight pastoral support systems geared at mental health vulnerabilities among African American congregants. And while their contribution does not set out to provide a major theoretical or methodological statement, their overview provides invaluable insights for practitioners, religious leaders, and others involved in mental health work in religious settings, particularly among minority populations.

One particularly illuminating line of inquiry involves the role that clergy play in health promotion and education (Stewart 2014, Teizazu et al. 2021, Wright et al. 2019). This work has shown the ability of religious leaders to marshal necessary resources and to build on existing networks of trust to provide positive health related messages and services to their members. A parallel line of work is exploring ways that congregational leadership may develop programmatic strategies for the transmission of health-related messages emphasizing sexual health and regular health screening (Brown and Cowart 2018; Powell et al. 2017; White et al. 2020). Additionally, several studies have highlighted the mental health benefits that accrue to members of disadvantaged communities, often persons of color, who are able to access faith-based support systems (Bryant et al. 2014; Bryant et al. 2015; Taylor et al. 2000; Williams et al. 2014). Continuing the focus on aging populations, Krause and Hayward (2012) have provided evidence of positive associations between pastoral emotional support, beliefs in God’s ability to alleviate personal burdens and a greater sense of hopefulness in late life. This accumulated work shows positive linkages between interventions that originate from religious organizational leadership and enhanced mental health functioning and well-being among participants. We suspect such interactions to provide beneficial support that will enhance well-being and health.

The Interaction of Leadership and Congregational Support

We also want to suggest that church leadership and the congregations they serve should not be seen as unrelated features of religious institutions, but rather as working in partnership to achieve organizational goals. And while these partnerships are not free from tensions, disagreements and even conflicts that may lead to religious fracturing, we are focused on alignments between clergy and membership that may foster an environment that is conducive to congregant mental health. We surmise that it is such an environment—one where clergy leadership and congregant values are aligned around mental health promotion—where religious adherents will benefit most from religious participation.

A starting point is work from Ellison and colleagues, where the study authors draw from a representative sample of US churchgoers to explore the perceptions that congregants hold towards clergy serving in mental health support roles (Ellison et al. 2006). Their work is a starting point to begin thinking of the additive impact of congregant and pastoral leadership on the organizational culture within religious institutions. Results from their work suggest that congregants hold very specific views and expectations in terms of the role that clergy can and should play in the provision of mental health support. While, on the one hand, the results of their study show that regular churchgoers are supportive of clergy acting as surrogate front line mental health workers, they are less inclined to support this role for clergy in cases of schizophrenia, or for persons who are perceived as being danger to themselves or others (Ellison et al. 2006). Such findings resonate with studies that highlight the role that clergy can play in shaping the organizational culture within their organizations. For instance, May’s (2020) recent study, based on roughly 50 interviews with clergy and members from five Christian congregations, show that the value orientations held by clergy greatly influenced the organizational culture within each study site (May 2020). When defined as “the collection of shared beliefs and values held by the organization’s members” (May 2020: 3, see also Schein 1990), we emphasize associations between messages from clergy, and now these messages might shape members’ belief systems; including their general treatment and support of one another.

Second, it is well established that conservative Protestant churches have been successful in advocating from the pulpit and therefore translating clergy messages to political action (for a recent review see, Wilde and Glassman 2016). Additionally, a growing line of work has focused on religious leadership’s ability to effectively communicate social justice frames that, in turn, amplify already existing sentiments among adherents (Brewer et al. 2003). Todd and Houston (2013), in their study of over 250 congregations spanning a 9-year period, have shown that congregants from organizations that were led by women or clergy of color, were more likely to be engaged in political activism than those led my white male clergy. Adler (2014) has shown the ways that religious leaders can influence the organizational culture of a congregation in relation to same-sex relationships. In contrast, Neiheisel and Djupe (2008) find that clergy who wish to speak out on issues of human sexuality will often need to show restraint in their messaging, or risk alienating members whose views do not align with their own.

What these studies share is an underlying theme of “connectedness” between clergy messaging, congregant beliefs and the organizational culture of the institution. We suspect that a cooperative atmosphere where clergy and membership are aligned in terms of a shared vision and mutual objectives, shapes an organizational culture that is most conducive to meeting specific needs. In terms of mental health support systems, we conceptualize the combined effects of clergy and congregant support in times of stress as additive, in that congregants receive an accumulated level of support from multiple sources within their religious community. Such an expectation parallels work from Krause (2006b) showing the additive effects of previously received support and future perceptions that support will continue to be forthcoming on improved self-reported health among older congregants. In terms of our specific conceptual expectations, we surmise that religious adherents will benefit most, and their overall mental health be augmented, when both clergy messages and organizational culture are aligned around provision of mental health support systems. While work in public health often explores multiple pathways leading to specific outcomes, we propose a parallel process whereby leadership and an organizational culture focused on mental health will work in tandem to enhance congregant well-being.

Research Hypotheses

As we have noted above, few studies have focused explicitly on disentangling collective versus individual forms of social support in religious settings. For this study, we operationalize each dimension by exploring sources of support from pastors and fellow congregants, and how these distinct support systems are associated with congregants' mental health. Given the general positive religion-health link in the literature, we expect to find both forms of religious support to be associated with improved mental health, in direct and interactive associations. Thus, we propose the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1

There will be a direct positive association between faith-based social support—congregant and pastoral—and improved mental health outcomes of individual members.

Hypothesis 2

There will be a multiplicative association between congregant and pastoral support with mental health, such that positive mental health outcomes will be amplified for members with high levels of both forms of support.

Methods

Data

Data come from an original survey of congregants in South Texas and the greater Washington DC area (including DC, Maryland, and Virginia). In the San Antonio area, we conducted paper and online surveys in Christian churches from evangelical, mainline, Catholic, and black American traditions, while the DC area canvassing also included Jewish synagogues. Between 2017 and 2019, we surveyed 19 organizations (San Antonio N = 13; DC N = 6) ranging in size from approximately 50 to more than 1500 congregants. Surveys were distributed to congregants during weekend services. Members of participating organizations were asked to fill out the survey and then return it within 3 weeks. Reminders were sent out on a weekly basis.

Participating organizations received a $1,000 contribution in appreciation for participation in the survey. However, at both sites, individual members’ participation was anonymous and voluntary and there was no monetary reward given to individual respondents. A total of 4689 paper surveys were distributed, along with online surveys distributed via email correspondences maintained by participating organizations. A total of 1882 completed surveys were returned (57 percent paper; 43 percent online), resulting in a response rate of 40 percent, though the rate could be considerably lower depending on the exact number of email solicitations received and opened. Unfortunately, most participating organizations lacked the technical staff and technology to provide specific information on mailings, “clicks” etc. Our analytic sample includes all completed and partially completed surveys (n = 1882).

Measures

Mental Health Mental health is a complex phenomenon that can include various experiences of distress and other negative emotions, on the one hand, and subjective well-being or eudaimonia, on the other. Following calls to operationalize mental health with a broad range of indicators (Thoits 2010), our analyses include five distinct mental health outcomes reflecting aspects of subjective distress and well-being. The first three outcomes are scales of past-month psychological distress, anxiety, and anger. Response options for all three scales range from never (= 1) to almost always (= 5). Psychological distress is measured by asking respondents how often they felt: (1) bothered by things that usually do not bother you; (2) lack of appetite; (3) that you could not “shake off the blues”; (4) that everything you did was an effort; (5) hopeless about the future; (6) unable to keep your mind on what you were doing; (7) so sad that nothing could cheer you up; (8) like you could not “get going”; (9) shortness of breath or trouble breathing; (10) numbness or tingling in parts of your body; (11) sweaty but not due to heat or exercise; and (12) that life is ultimately meaningless (Andrews and Slade 2001; Radloff 1977).

Anxiety is measured by asking respondents how often they felt: (1) trembling and shaky; (2) worried over possible misfortunes; (3) your muscles were tense; (4) could not control your thoughts; (5) like the worst was going to happen; (6) butterflies in your stomach; (7) dizzy or lightheaded; (8) like you were missing out on things in life; and (9) that you had to keep busy to avoid unpleasant thoughts (Julian 2011).

Anger is measured by asking respondents how often they felt: (1) angry; (2) like you were “boiling up inside”; (3) outraged by something somebody had said or done; (4) unable to control your temper; (5) difficulty forgiving people who have angered you; (6) that you could not stop thinking about everything that makes you angry; and (7) that you wanted to “get back” at someone who had angered you (Petersen and Kellam 1977; Spielberger et al. 1995).

The last two outcomes are life satisfaction and optimism. Response options range from strongly disagree (= 1) to strongly agree (= 4). Life satisfaction is measured with the following indicators: (1) In most ways, my life is close to my ideal; (2) The conditions of my life are excellent; (3) I am satisfied with my life; (4) So far, I have gotten the important things I want in life; and (5) If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing (Diener et al. 1985).

We measure optimism with the following indicators: (1) In uncertain times, I usually expect the best; (2) If something can go wrong for me, it will (reverse-coded); (3) I always look on the bright side of things; (4) I’m always optimistic about my future; (5) I hardly ever expect things to go my way (reverse-coded); (6) Things never work out the way I want them to (reverse-coded); (7) I’m a believer in the idea that “every cloud has a silver lining”; and (8) I rarely count on good things happening to me (Scheier and Carver 1985).

Religious Social Support. We include two separate scales for congregant support and congregant leader support. Respondents were presented with the following items, asked separately for their congregant leader and fellow congregants (for Jewish congregations, the word “synagogue” was substituted for church): (1) I feel very close to my church leader/other members of my church; (2) My church leader/other members of my church would take the time to talk over my problems if I needed to; (3) My church leader/fellow church members often criticize(s) the choices I make (reverse-coded); (4) My church leader/fellow church members make(s) me feel like a worthwhile person; (5) My church leader/other members of my church expect too much from me (reverse-coded); (6) When I am around my church leader/other members of my church, I can completely relax and be myself; (7) My church leader/members of my church really care(s) about me; and (8) My church leader/members of my church treat(s) me like I am an inferior person (reverse-coded). Response options range from strongly disagree (= 1) to strongly agree (= 4). The two scales are correlated at r = 0.58 (34% shared variance).

Covariates. Analyses include covariates for age (in years), gender (1 = female, 0 = male), race-ethnicity (Black, Hispanic, other race, White), marital status (1 = married, 0 = single), educational attainment (ordinal, 1 = less than high school, 5 = postgraduate), and household income (ordinal, 1 = less than $10k, 8 = more than $250k). We also control for religious attendance (ordinal, 1 = a few times a year or less, 5 = several times a week), private prayer (ordinal, 1 = never, 6 = several times a day), and religious salience (ordinal, 1 = religious faith is not at all important, 5 = religious faith is the most important thing in life).

These variables are added to account for the possibility that different socioeconomic groups, as well as more religiously engaged respondents, exhibit distinct mental health profiles, and seek out religious social support more often than their peers. If this is the case, then any associations between religious social support and mental health may be confounded by socioeconomic status or other dimensions of religious involvement. For example, past studies show that socioeconomically marginalized groups tend to rely on religious coping resources more often than their advantaged peers (DeAngelis et al. 2019). Links between religious involvement and mental health also vary for different racial-ethnic and socioeconomic groups (DeAngelis and Ellison 2018; Schieman et al. 2006). Finally, to account for potential geographic heterogeneity in mental health and religious social support, we include a dummy variable for whether the survey was conducted in San Antonio or Washington, D.C.

Analytic Strategies

We use linear regression techniques with robust standard errors to estimate mental health outcomes. Standard errors are clustered by congregations (n = 20) to account for intraclass correlations or non-independence of observations within congregations. That is, our standard error estimates account for the possibility that members of the same congregation are more alike with each other than with members of other congregations—in terms of, for example, religious preferences or shared experiences within their congregations—which we cannot directly measure. Each outcome is estimated with the following five models: (1) congregant support only; (2) congregant leader support only; (3) congregant support + congregant leader support; (4) Model 3 + congregant support × congregant leader support interaction; (5) Model 4 + covariates. The two support variables are centered on their respective means.

All variables have missing observations. Proportions of missingness range from 6% for religious attendance (n = 121) to 13% for congregant support (n = 251). We replace all missing observations with 25 iterations of multiple imputation by chained equation (Johnson and Young 2011). Findings reported below are substantively identical when we use listwise deletion.

Results

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics of study variables. On average, respondents are 61 years old, college educated, earn household incomes between $50k–100k, attend services nearly once a week, pray daily, and consider their religious faith to be very important. Most respondents are also female (65%), White (60%), married (68%), and from San Antonio (64%). Average levels of congregant and leader support are also high (approximately 4 out of 5).

Tables 2 and 3 report unstandardized linear regression coefficients of mental health outcomes. Covariates are excluded from these tables to streamline the presentation of findings (full models available upon request). Two consistent patterns emerge in these tables. First, apart from optimism, only congregant support has significant direct associations with mental health outcomes while holding the other support variable constant. In models that include covariates, increased congregant support is associated with fewer symptoms of psychological distress (b = − 0.138; p < 0.01), anxiety (b = − 0.142; p < 0.01), and anger (b = − 0.177; p < 0.01), as well as greater life satisfaction (b = 0.205; p < 0.001) and optimism (b = 0.138; p < 0.01). Religious leader support is only associated with increased optimism when holding congregant support constant (b = 0.098; p < 0.01). Consequently, we find partial support for hypothesis 1.

Second, faith leader and congregant support exhibit multiplicative relationships with all mental health outcomes, except for life satisfaction, lending support to our second hypothesis. The interaction terms for psychological distress, anxiety, and anger are all negative and statistically significant, thereby indicating that the inverse associations between congregant support and these mental health outcomes are amplified when leader support is also higher. The inverse is true for optimism: the significant and positive interaction term indicates that leader support amplifies the positive association between congregant support and optimism.

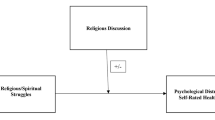

Figures 1 and 2 provide visual confirmation of two interactions, revealing interesting patterns that are difficult to discern from the regression coefficients alone. In these figures, we find that congregant support is not associated with mental health outcomes when faith leader support is low (i.e., below the sample average). Only when leader support is at or above the sample average do we find consistent associations between congregant support and mental health outcomes. These patterns can be confirmed in Table 4, which reports marginal associations between congregant support and mental health outcomes at representative values of congregant leader support. The takeaway is that congregant support is associated with better mental health only in cases where leader support is also higher. When leader support is below average, congregant support does not appear to benefit mental health.

These patterns should be observed with some caution. The adjusted R-squared estimates show that congregant support, leader support, and their interaction account for only around 5–10% of unique variance in mental health outcomes. Our analyses nevertheless demonstrate that any potential mental health benefits of congregant support may be conditional on leader support, and vice-versa. This finding is critical for faith leaders to be aware of, as it suggests that the mental health benefits of religious social support are contingent upon receiving consistent and robust support from everyone in the congregation. We discuss the implications of this finding in more detail to follow.

Conclusions and Implications

Our study examined how congregational and pastoral support are associated with faith community members’ mental health. Our results indicated that congregant support has more robust associations with mental health outcomes than faith leader support. However, we also found that leader support moderated these associations such that congregant support is associated with better mental health only in contexts where leader support is also high.

Empirical research has shown evidence of religion’s role in providing emotional support in times of interpersonal relationship strain (Granqvist and Hagekull 2003). As has been noted, “in most religious belief systems, God’s love is either unconditional or available through particular courses of action, which allow an otherwise ‘unworthy’ person to ‘earn’ God’s love and forgiveness” (Granqvist et al. 2010: 54). At the level of tangible support, research has shown a growing emphasis on mental health support systems in religious communities and emphasizes the positive role that clergy and the organizations they manage can play in terms of substantive health provision, particularly in low-income communities (Wong et al. 2018). And while a less established line of research, results in Muslim faith communities report similar patterns where spiritual leaders are able to foster a culture of overall health promotion and to encourage members to provide comfort and support to fellow members (Osman et al. 2005). Consistent with this perspective, we find that the links between mental health and religion are explained, at least in part, by the presence of positive interactions between fellow congregants and faith leaders. Such an association has been reported in multiple settings giving us confidence that our results are representative of a more general pattern existing within diverse religious communities. Additionally, as Krause’s (2006a) research with older Americans has shown, the salutary effects of religious social support can exceed forms of secular social support, a finding that underscores the distinctiveness of religious support systems aimed at psychological health.

One unexpected yet informative finding from our study is the interaction between congregant and pastoral support. At first glance, our results would seem to indicate null effects of pastoral leadership on most mental health outcomes, but the interactions reveal a more complex story. Our results suggest that the potential mental health benefits of congregational support are predicated on the presence of pastoral support. This implies that faith leaders play a decisive role in promoting positive mental health outcomes among community members. But why might this be the case? We suggest several plausible explanatory mechanisms.

First, while clearly an understudied area, there is mounting evidence that the organizational strength and vitality of religious firms is often a function of dynamic and collaborative pastoral leadership (Wollschleger 2018). It makes sense then, as the literature has shown, that religious leadership can play a central role in health promotion and health-related service provision (Rowland and Isaac-Savage 2014). In religious settings, leadership often functions as the primary vehicle by which the organization initiates its mission and goals. With less bureaucratic red tape and complexity to manage, religious leaders are often equipped to drive organizational change in ways that leaders in larger, more complex organizations are unable to. When applied to mental health challenges that congregants might face, religious leaders are able to mobilize resources and create partnerships with key stakeholders and local agencies with the aim of addressing psychological well-being (Robinson et al. 2018). Such partnerships may have the latent effect of creating a culture of tolerance that fosters greater openness and willingness to engage in help-seeking behaviors among congregants.

Secondly, the messages that religious leaders communicate to their members can have a significant impact on the overall climate and collective mood found within the congregational setting. As with the latent effects of community partnerships noted above, when so-called “messages from the pulpit” are directed at health behaviors, pastoral communications also have the capacity to foster a more inclusive congregational culture—one where mental health concerns are treated with greater tolerance and understanding (Hankerson et al. 2018). Additionally, previous research has reinforced the influence that messages from religious authorities can have on disclosing health-related information that can aid in counseling, service provision and congregant health promotion (Hankerson et al. 2018; Jeffries et al. 2017). We surmise that such leadership approaches—pastoral direction that fosters an environment of supportive peers and tolerant faith networks—impact the overall well-being and psychological health of an organization’s membership base.

Our findings may be extended to practical applications for continued leadership strategies aimed at advancing congregant health and well-being. First, one key implication of our study is that the impact of clergy leadership on advancing the mental health of their members, is most salient in circumstances where clergy messaging is aligned with the views of their membership. In other words, as far as mental health support in religious settings is concerned, the greatest impact on congregant health is found in institutions where the organizational culture fosters mental health outreach on the part of both, leadership and membership. For this reason, we suggest that training modules and other tools may be developed that specifically highlight successful strategies for faith leadership in promoting salient mental health messages and in expanding resources to their faith communities. Such educational resources can reinforce the key finding from our study noted above: while congregational and pastoral support play a positive role in enhancing congregant well-being, it is in organizational settings where membership and leadership share a commitment to psychological well-being that religion is most conducive to positive mental health outcomes.

Second, messaging that aligns theological messages with health promotion could serve as a constructive form of communication that provides both spiritual guidance and constructive health-related information. Above we cite research showing that messages from the pulpit have the capacity to express religious teachings while also fostering an atmosphere among congregants that is tolerant and sympathetic to mental health issues. Finally, realizing the important role of religious leadership in shaping congregational culture, emphasis on mental health training, professional credentialling and counseling education as part of the seminary curriculum, would all serve to create the type of collaboration between religious leadership and its membership that, as our study suggests, best facilitates congregant well-being and psychological health.

As with most cross-sectional studies, this study has several potential limitations. One immediate shortcoming is the nature of our study sample which, not being a nationally representative sample, does not allow us to generalize to a larger, representative sample of US congregants. However, we do suggest that the community-based samples we collected using a more purposive sampling approach, generated a reasonably diverse sample. We also note the correlational nature of the study which does not allow us to make causal claims in reference to religious social support and mental health. Future work could consider these issues by drawing from panel data, while qualitative research may shed light on some of the underlying mechanisms that are at work in the present study. Specifically, interviews with both religious leaders and congregants—interviews that are designed to capture the dynamics of the “faith leader-congregant” relationship—could be informative in providing an explanatory lens into the interaction between congregational and pastoral support described here. Finally, few studies in this area, including ours, test links between religious involvement and biomarker indicators of distress and health (Page et al. 2020). While our sample lacked such indicators, future work could incorporate biomarkers into their study designs to account for potential self-report biases or underreports of stress and distress.

With these limitations in mind, our study adds to the literature on religious social support and mental health in several ways. First, we contribute to work that addresses relational support between members of religious organizations and leadership. We find this to be a fruitful avenue of future work that could be extended to faith traditions outside the major Judeo-Christian denominations in the United States. Furthermore, our work is aimed at both scholars and practitioners and will hopefully encourage conversation related to the role of clergy in resource provision aimed at improved health. Such discussions could lead to specific policy, educational and leadership initiatives that might foster greater mental health support structures within religious organizations. Finally, we expand on past empirical work that has assessed the multiple pathways by which religious factors influence health and well-being (Ellison 1991; Pargament et al. 2000), particularly by revealing the unique interactive associations of pastoral and congregant support with congregant mental health. We hope our work will contribute to continued scholarship that focuses on the role of both collective and individual level factors that may enhance psychological outcomes in religious settings.

References

Acevedo, Gabriel A., Christopher G. Ellison, and Xu. Xiaohe. 2014. Is it really religion? Comparing the main and stress-buffering effects of religious and secular civic engagement on psychological distress. Society and Mental Health 4 (2): 111–128.

Adler, Gary. 2014. An opening in the congregational closet? Boundary-bridging culture and membership privileges for gays and lesbians in Christian religious congregations. Social Problems 59 (2): 177–206. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2012.59.2.177.

Alexander, Jeffrey C. 1988. Durkheimian Sociology: Cultural Studies. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Andrews, Gavin, and Tim Slade. 2001. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10). Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 25 (6): 494–497.

Blaine, Bruce, and Jennifer Crocker. 1995. Religiousness, race, and psychological well-being—Exploring social-psychological mediators. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 21 (10): 1031–1041. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672952110004.

Bradbury, Suzanne. 2004. The use of pastoral support programs within schools. Educational Psychology in Practice 20 (4): 303–318.

Bradshaw, Matt, and Christopher G. Ellison. 2010. Financial hardship and psychological distress: Exploring the buffering effects of religion. Social Science & Medicine 71 (1): 196–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.015.

Brewer, Gayle, Sarita Robinson, Altaf Sumra, Erini Tatsi, and Nadeem Gire. 2015. The influence of religious coping and religious social support on health behavior, health status and health attitudes in a British Christian sample. Journal of Religion and Health 54 (6): 2225–2234.

Brewer, Mark D., Rogan Kersh, and R. Eric Petersen. 2003. Assessing conventional wisdom about religion and politics: A Preliminary view from the pews. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42 (1): 125–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5906.00166.

Bryant, Keneshia, Todd Moore, Nathaniel Willis, and Kristie Hadden. 2015. Development of a faith-based stress management intervention in a rural African American community. Progress in Community Health Partnerships 9 (3): 423–430. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2015.0060.

Bryant, Keneshia, Tiffany Haynes, Karen Hye-cheon Kim. Yeary, Nancy Greer-Williams, and Mary Hartwig. 2014. A rural African American faith community’s solutions to depression disparities. Public Health Nursing 31 (3): 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12079.

Brown, Maria T., and Luvenia W. Cowart. 2018. Evaluating the effectiveness of faith-based breast health education. Health Education Journal 77 (5): 571–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896918778308.

Cahill, Jo., Jan Bowyer, and Sue Murray. 2014. An exploration of undergraduate students’ views on the effectiveness of academic and pastoral support. Educational Research 56 (4): 398–411.

Chatters, Linda M. 2000. Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health 21 (1): 335–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335.

Chatters, Linda M., Robert Joseph Taylor, Amanda Toler Woodward, and Emily J. Nicklett. 2015. Social support from church and family members and depressive symptoms among older African Americans. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 23 (6): 559–567. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.04.008.

Cherniak, Aaron D., Mario Mikulincer, Phillip R. Shaver, and Pehr Granqvist. 2020. Attachment theory and religion. Current Opinion in Psychology 40: 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.08.020.

Cohen, Sheldon, and Thomas Ashby Wills. 1985. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin 98 (2): 310–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

DeAngelis, Reed T., John P. Bartkowski, and Xu. Xiaohe. 2019. Scriptural coping: An empirical test of hermeneutic theory. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58 (1): 174–191.

DeAngelis, Reed T., and Christopher G. Ellison. 2018. Aspiration strain and mental health: The education-contingent role of religion. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 57 (2): 341–364.

Diener, Es., Robert A. Emmons, Randy J. Larsen, and Sharon Griffin. 1985. The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment 49 (1): 71–75.

Dunn, Marianne G., and Karen M. O’Brien. 2009. Psychological health and meaning in life stress, social support, and religious coping in Latina/Latino immigrants. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences 31 (2): 204–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739986309334799.

Ellison, Christopher G. 1991. Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 32 (1): 80–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136801.

Ellison, Christopher G. 1993. Religious involvement and self-perception among Black Americans. Social Forces 71 (4): 1027–1055. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/71.4.1027.

Ellison, Christopher G. 1995. Race, religious involvement and depressive symptomatology in a southeastern US community. Social Science & Medicine 40 (11): 1561–1572. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)00273-v.

Ellison, Christopher G., and Linda K. George. 1994. Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community: A study of a theoretical-model linking institutional church participation and social network relationships. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 33 (1): 46–61. https://doi.org/10.2307/1386636.

Ellison, Christopher G., and Jeffrey S. Levin. 1998. The religion-health connection: Evidence, theory, and future directions. Health Education & Behavior 25 (6): 700–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019819802500603.

Ellison, Christopher G., Margaret L. Vaaler, Kevin J. Flannelly, and Andrew J. Weaver. 2006. The clergy as a source of mental health assistance: What Americans believe. Review of Religious Research 48(2): 190–211. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20058132

Ellison, Christopher G., Marc A. Musick, and Andrea K. Henderson. 2008. Balm in gilead: Racism, religious involvement, and psychological distress among African-American adults. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47(2): 291–309. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20486913

Feeney, Brooke C., and Nancy L. Collins. 2015. Thriving through relationships. Current Opinion in Psychology 1: 22–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.11.001.

George, Linda K., Christopher G. Ellison, and David B. Larson. 2002. Explaining the relationships between religious involvement and health. Psychological Inquiry 13 (3): 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1303_04.

Granqvist, Pehr, Mario Mikulincer, and Phillip R. Shaver. 2010. Religion as attachment: Normative processes and individual differences. Personality and Social Psychology Review 14 (1): 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309348618.

Granqvist, Pehr, and Berit Hagekull. 2003. Longitudinal predictions of religious change in adolescence: Contributions from the interaction of attachment and relationship status. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 20 (6): 793–817. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407503206005.

Hankerson, Sidney H., Kenneth Wells, Martha Adams Sullivan, Joyce Johnson, Laura Smith, La’Shay. Crayton, Faith Miller-Sethi, Clarencetine Brooks, Alana Rule, Jaylaan Ahmad-Llewellyn, Doris Rhem, Xavier Porter, Raymond Croskey, Eugena Simpson, Charles Butler, Samuel Roberts, Alicia James, and Loretta Jones. 2018. Partnering with African American churches to create a community coalition for mental health. Ethnicity & Disease 28 (Suppl 2): 467–474. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.28.S2.467.

Hayward, R David, and Neal Krause. 2013. Changes in church-based social support relationships during older adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 68 (1): 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs100.

Hill, Terrence D., Liwen Zeng, Simone Rambotti, Krysia N. Mossakowski, and Robert J. Johnson. 2021. Sad eyes, crooked crosses: Religious struggles, psychological distress and the mediating role of psychosocial resources. Journal of Religion & Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01273-y.

Jeffries, William L., IV., Madeline Y. Sutton, and Agatha N. Eke. 2017. On the battlefield: The black church, public health, and the fight against HIV among African American gay and bisexual men. Journal of Urban Health 94 (3): 384–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-017-0147-0.

Johnson, David R., and Rebekah Young. 2011. Toward best practices in analyzing datasets with missing data: Comparisons and recommendations. Journal of Marriage and Family 73 (5): 926–945.

Julian, Laura J. 2011. Measures of anxiety: State-trait anxiety inventory (STAI), beck anxiety inventory (BAI), and hospital anxiety and depression scale-anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care & Research 63 (S11): S467–S472.

Kent, Blake Victor. 2020. Religion/spirituality and gender-differentiated trajectories of depressive symptoms age 13–34. Journal of Religion and Health 59 (4): 2064–2081. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-019-00958-9.

Koenig, Harold George. 1997. Is religion good for your health?: The effects of religion on physical and mental health. New York: Routledge.

Koenig, Harold G. 2018. Religion and mental health: Research and clinical applications. Cambridge: Elsevier.

Krause, Neal. 2002. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 57 (6): S332–S347. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.6.S332.

Krause, Neal. 2006a. Exploring the stress-buffering effects of church-based and secular social support on self-rated health in late life. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 61 (1): S35–S46.

Krause, N. 2006b. Church-based social support and change in health over time. Review of Religious Research 48(2): 125–140. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20058128

Krause, Neal, and Kyriakos Markides. 1990. Measuring social support among older adults. International Journal of Aging & Human Development 30 (1): 37–53. https://doi.org/10.2190/cy26-xckw-wy1v-vgk3.

Krause, Neal, Christopher G. Ellison, and Keith M. Wulff. 1998. Church-based emotional support, negative interaction, and psychological well-being: Findings from a national sample of presbyterians. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 37 (4): 725–741. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388153.

Krause, Neal, Christopher G. Ellison, Benjamin A. Shaw, John P. Marcum, and Jason D. Boardman. 2001. Church-based social support and religious coping. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40 (4): 637–656. https://doi.org/10.1111/0021-8294.00082.

Krause, Neal, and R. David. Hayward. 2012. Informal support from a pastor and change in hope during late life. Pastoral Psychology 61: 305–318. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-011-0411-2.

Lemert, Charles C. 1979. Language, structure, and measurement: Structuralist semiotics and sociology. American Journal of Sociology 84 (4): 929–957. https://doi.org/10.1086/226867.

Levin, Jeff. 2010. Religion and mental health: Theory and research. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies 7 (2): 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1002/aps.240.

Levin, Jeffrey S., Linda M. Chatters, Robert Joseph Taylor. 1995. Religious effects on health status and life satisfaction among black americans. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 50B, (3): S154–S163. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/50B.3.S154.

Lim, Chaeyoon, and Robert D. Putnam. 2010. Religion, social networks, and life satisfaction. American Sociological Review 75: 914–933.

May, Matthew. 2020. Superordinate ties, value orientations, and congregations’ organizational cultures. Religions 11 (6): 277. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel11060277.

McFarland, Michael J. 2010. Religion and mental health among older adults: Do the effects of religious involvement vary by gender? Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 65 (5): 621–630. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbp112.

Neiheisel, Jacob R., and Paul A. Djupe. 2008. Intra-organizational constraints on churches’ public witness. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 47 (3): 427–441. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2008.00419.x.

Nguyen, Ann W. 2020. Religion and mental health in racial and ethnic minority populations: A review of the literature. Innovation in Aging 4 (5): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa035.

Nooney, Jennifer, and Eric Woodrum. 2002. Religious coping and church-based social support as predictors of mental health outcomes: Testing a conceptual model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41 (2): 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5906.00122.

Osman, Ali M., Glen Milstein, and Peter M. Marzuk. 2005. The Imam’s role in meeting the counseling needs of Muslim communities in the United States. Psychiatric Services 56 (2): 202–205. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.56.2.202.

Page, Robin L., Jill N. Peltzer, Amy M. Burdette, and Terrence D. Hill. 2020. Religiosity and Health: A Holistic iopsychosocial Perspective. Journal of Holistic Nursing 38(1): 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010118783502.

Pargament, Kenneth I., Harold G. Koenig, and Lisa M. Perez. 2000. The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology 56 (4): 519–543. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-4679(200004)56:4%3c519::Aid-jclp6%3e3.0.Co;2-1.

Pargament, Kenneth I., and Kenneth I. Maton. 2000. Religion in American life. In Handbook of community psychology, 495–522. Boston: Springer.

Park, Crystal L., Cheryl L. Holt, Daisy Le, Juliette Christie, and Beverly Rosa Williams. 2018. Positive and negative religious coping styles as prospective predictors of well-being in African Americans. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 10 (4): 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000124.

Petersen, Anne C., and Sheppard G. Kellam. 1977. Measurement of the psychological well-being of adolescents: The psychometric properties and assessment procedures of the how I feel. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 6 (3): 229–247.

Powell, Terrinieka W., Fiona H. Weeks, Samantha Illangasekare, Eric Rice, James Wilson, Debra Hickman, and Robert W. Blum. 2017. Facilitators and barriers to implementing church-based adolescent sexual health programs in Baltimore City. Journal of Adolescent Health 60 (2): 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.09.017.

Radloff, Lenore Sawyer. 1977. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1 (3): 385–401.

Robinson, Michael A., Sharon Jones-Eversley, Sharon E. Moore, Joseph Ravenell, and A. Christson Adedoyin. 2018. Black male mental health and the black church: Advancing a collaborative partnership and research agenda. Journal of Religion and Health 57 (3): 1095–1107. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0570-x.

Rosmarin, David H., and Harold G. Koenig. 2020. Handbook of spirituality, religion, and mental health. Waltham: Elsevier.

Rowland, Michael L., and E. Paulette Isaac-Savage. 2014. As I see it: A study of African American pastors’ views on health and health education in the black church. Journal of Religion and Health 53 (4): 1091–1101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9705-2.

Scheier, Michael F., and Charles S. Carver. 1985. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology 4 (3): 219–247.

Schein, Edgar H. 1990. Organizational culture. American Psychologist 45 (2): 109–119.

Schieman, Scott, Teyana Pudrovska, Leonard I. Pearlin, and Christopher G. Ellison. 2006. The sense of divine control and psychological distress: Variations across race and socioeconomic status. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45 (4): 529–549.

Shelton, Rachel L., Mewelau Hall, Seairra Ford, and Robert L. Cosby. 2021. Telehealth in a Washington, Dc African American religious community at the onset of Covid-19: Showcasing a Virtual Health Ministry Project. Social Work in Health Care 60 (2): 208–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2021.1904322.

Sherkat, Darren E., and Mark D. Reed. 1992. The effects of religion and social support on self-esteem and depression among the suddenly bereaved. Social Indicators Research 26 (3): 259–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00286562.

Schieman, Scott, Alex Bierman, and Christopher G. Ellison. 2013. Religion and mental health. In Handbook of the sociology of mental health, 457–478. Dordrecht: Springer.

Snowden, A. 2021. What did chaplains do during the Covid pandemic? An international survey. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling 75(1_SUPPL): 6–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1542305021992039.

Spielberger, Charles D., Eric C. Reheiser, and Sumner J. Sydeman. 1995. Measuring the experience, expression, and control of anger. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing 18 (3): 207–232.

Stewart, Jennifer M. 2014. Pastor and lay leader perceptions of barriers and supports to HIV Ministry Maintenance in an African American Church. Journal of Religion & Health 53 (2): 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9627-4.

Taylor, Robert J., Christopher G. Ellison, Linda M. Chatters, Jeffrey S. Levin, and Karen D. Lincoln. 2000. Mental health services in faith communities: The role of clergy in black churches. Social Work 45 (1): 73–87. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/45.1.73.

Taylor, Robert J., and Linda M. Chatters. 1988. Church members as a source of informal social support. Review of Religious Research 30 (2): 193–203. https://doi.org/10.2307/3511355.

Teizazu, Hawi, Jennifer S. Hirsch, Richard G. Parker, and Patrick A. Wilson. 2021. Framing HIV and AIDS: How leaders of black religious institutions in New York City interpret and address sex and sexuality in their HIV interventions. Culture, Health & Sexuality. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2021.1898676.

Thoits, Peggy A. 2010. Stress and health: Major findings and policy implications. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 51 (S): S41–S53.

Todd, Nathan R., and Jaclyn D. Houston. 2013. Examining patterns of political, social service, and collaborative involvement of religious congregations: A latent class and transition analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology 51 (3–4): 422–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-012-9561-3.

Vishkin, Allon, Yochanan Bigman, and Maya Tamir. 2014. Religion, emotion regulation, and well-being. In Religion and spirituality across cultures, ed. C. Kim-Prieto, 247–269. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands.

White, Jordan J., Derek T. Dangerfield, Erin Donovan, Derek Miller, and Suzanne M. Grieb. 2020. Exploring the role of LGBT-affirming churches in health promotion for black sexual minority men. Culture Health & Sexuality 22 (10): 1191–1206. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2019.1666429.

Wilde, Melissa, and Lindsay Glassman. 2016. How complex religion can improve our understanding of American politics. Annual Review of Sociology 42 (1): 407–425. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-081715-074420.

Williams, Laverne, Robyn Gorman, and Sidney Hankerson. 2014. Implementing a mental health ministry committee in faith-based organizations: The promoting emotional wellness and spirituality program. Social Work in Health Care 53 (4): 414–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2014.880391.

Wimberly, Edward P. 1979. Pastoral care in black churches. Nashville: Abingdon Press.

Wollschleger, Jason. 2018. Pastoral leadership and congregational vitality. Review of Religious Research 60 (4): 575–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-018-0352-7.

Wong, Eunice C., Brad R. Fulton, and Kathryn P. Derose. 2018. Prevalence and predictors of mental health programming among U.S. religious congregations. Psychiatric Services 69 (2): 154–160. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600457.

Wright, LaNita S., Sarah Maness, Paul Branscum, Daniel Larson, and E Laurette Taylor. 2019. Pastors’ perceptions of the black church’s role in teen pregnancy prevention. Health Promotion Practice 21 (3): 344–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839919834269.

Acknowledgements

Data for this study was supported by grants from the H. E. Butt Foundation and the John Templeton Foundation (#61107). Reed DeAngelis received support from the Population Research Infrastructure Program (P2C-HD050924) and the Biosocial Training Program (T32-HD091058) awarded to the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Bill by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Acevedo, G.A., DeAngelis, R.T., Farrell, J. et al. Is it the Sermon or the Choir? Pastoral Support, Congregant Support, and Worshiper Mental Health. Rev Relig Res 64, 577–600 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-022-00500-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-022-00500-6