Abstract

This paper offers a compositional take on two internally complex conditional connectives in Mandarin, zhi-yao ‘only-need’ and zhi-you ‘only-have’. While the former conveys the antecedent proposition’s minimal sufficiency, the latter conveys its necessity for the consequent proposition to come true. Both connectives will be treated as pairing an exclusive particle, zhi, with a modal, an assumption that is less controversial for the necessity modal yao than for you, which will be treated as a possibility modal. Accepting this treatment, however, we have two connectives that openly differ in modal force. While the surface order will be preserved for zhi-you, an inversion will be shown to lead to better results for zhi-yao. In both cases, a possible extension to monoclausal uses is considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This paper deals with two conditional connectives in Mandarin, zhi-yao ‘only-need’ and zhi-you ‘only-have’.Footnote 1 The two are special by virtue of their internal complexity. Both of them have the exclusive particle zhi ‘only’ as their first component, and differ only in the second. This difference leads to substantial differences in interpretation, however, and a major goal of this paper is to account for these differences in a compositional fashion. I start by looking at each of zhi-{yao,you} in turn.

The interpretive effect of zhi-yao ‘only-need’ may be taken to consist in what Grosz (2012) calls minimal sufficiency. An informal definition of the latter goes like this:

The scalar component in (1-b) easily translates into p being easy to satisfy, i.e., ranking low on an effort scale, cf. Liu (2017a) a.o.

A sentence like (2-a) can be shown to fall under this pattern. As a conditional connective, zhiyao combines with two proposition-denoting clauses, an antecedent p and a consequent q.Footnote 2 In the case at hand, p is the proposition that you smile, and q the proposition that I’m happy.Footnote 3

The minimal sufficiency interpretation the sentence intuitively has is given in (3): p is implied to both suffice for q, and to rank low(est) on a scale (to require minimal effort).

What makes zhiyao especially appealing for semantic analysis is its internal make-up, which strikingly resembles a pattern investigated by von Fintel and Iatridou (2007): an exclusive particle—zhi ‘only’—conspires with a necessity modal—yao ‘need’—to convey minimal sufficiency.

The exclusive force we would expect an only-sentence to have is lost, and the sentence even has an additive flavor to it: if it takes as little as a smile from the hearer H for the speaker S to be happy, then it is easy to infer that relevant alternatives to a mere smile from H, which take conceivably more effort, make S happy at least as easily. (2-a) works in a scenario in which H has just offered S to bake a cake for her (say, because it’s S’s birthday). In uttering (2-a), S implies herself to be easier to please than that, by no means denying that she would be happy about a cake as well.

In terms of its internal composition, zhi-yao strongly resembles another item which can also be used as a conditional connective, namely zhi-you ‘only-have’. The necessity modal yao ‘need’ is replaced by you ‘have, exist’. The interpretive effect of this permutation is huge: instead of conveying (minimal) sufficiency, zhiyou conveys necessity. Necessity can be informally characterized as follows.Footnote 4

English necessity conditionals involve only if (Herburger 2015, 2019),Footnote 5 and this is how zhiyou translates in the following example, a variation of (2-a).Footnote 6

In line with the definition in (5), this sentence’s necessity-implication can be put as follows:

To recap:

If these characterizations are correct, then zhiyao and zhiyou are in complementary distribution in terms of sufficiency and necessity. Thinking of these relations as semantic features [±suff] and [±nec], respectively, zhiyao can be described as [+suff,-nec], and zhiyou as [-suff,+nec]. A diagnostic applied by Herburger (2016, 2019) enables us to add substance to this claim. If for a given conditional if p q, where if is just a placeholder for a given conditional connective, you cannot felicitously follow up doubting that p makes q true, you have evidence for sufficiency. By contrast, if you can felicitously follow up admitting the possibility that q may be true without p being also true, you get evidence for necessity.

Let us start with zhiyou, just claimed to be [-suff,+nec]:

Following this example, the speaker S can felicitously doubt that [\(_\text {p}\) hard work] invariably leads to [\(_\text {q}\) success]. This confirms [-suff]: (10-a) wouldn’t work as a follow-up otherwise.Footnote 7 At the same time, S cannot felicitously mention the possibility that there is [\(_\text {q}\) success] without [\(_\text {p}\) hard work], as seen in (10-b). This confirms [+nec]. In other words, zhiyou patterns with only if in these crucial respects.Footnote 8

These felicity judgments reverse when the conditional to be continued is a zhiyao-conditional:

Someone uttering (11) contradicts herself by subsequently questioning that [\(_\text {p}\) hard work] leads to [\(_\text {q}\) success], as seen in (12-a). This confirms that zhiyao is [+suff]. On the other hand, the same speaker can consistently follow up entertaining the possibility that [\(_\text {q}\) success] may come about without [\(_\text {p}\) hard work] having been invested, (12-b). This is expected from zhiyao being [-nec]. In other words, zhiyao-conditionals work like English if-conditionals, leaving aside minimality for a moment.Footnote 9

Our preliminary finding can be summed up like this:

This classification is based on conditional uses of zhiyou and zhiyao. But at least zhiyou is well known for its nonconditional, monoclausal uses (Hole 2004, 2017; Sun 2021 a.o.). The following example involves obligatory object fronting into the preverbal domain.Footnote 10

And even zhiyao does seem to have a monoclausal variant of sorts:

Monoclausal uses can be schematized as follows:

where P and Q are each properties of individuals: in the cases at hand, being tea for P and being drunk by Old Wang for Q. A successful analysis of zhiyao and zhiyou should cover these monoclausal uses as well.

Still, the main focus of this paper is on conditional uses, and the goal is to derive the featural opposition in (13) in a compositional fashion. A compositional analysis of zhiyou is proposed in Sect. 2. Under the tempting assumption that you is an existential modal, zhiyou-conditionals will be treated as necessity-conditionals wearing existential force on their sleeves, unlike only if conditionals, for which existential force is sometimes posited, cf. Herburger (2019) a.o. Sect. 3 deals with zhiyao, for which an inverse scope analysis is proposed. zhi’s exclusive force is weakened by having it scope below the universal modal denoted by yao, and silent even captures an additive implication zhiyao-conditionals give rise to. Both sections also consider an extension of the analysis to monoclausal uses. Section 4 discusses interactions of the two connectives with modals in the consequent, and Sect. 5 concludes with some remaining issues.

2 zhi-you ‘only-have’

This section offers a compositional analysis of zhiyou-conditionals. As a reminder, zhi-you ‘only-have’ is internally composed of an exclusive, zhi, and an existential, you. The purpose of the following two subsections is to shed some light on each of these two items. The section on you contains the auxiliary assumption that you has a modal variant. This assumption allows us to bring zhi and you together in an analysis that resembles Herburger (2015, 2019)’s analysis of only if conditionals in that an exclusive applies to a modal claim of existential force.

2.1 zhi ‘only’

This subsection motivates a treatment of zhi as an exclusive particle—a view that may be uncontroversial, but still requires some motivation. On the rather old-fashioned working semantics assumed here, zhi asserts the conjunction of its prejacent p (positive component) and the negation of all of p’s contextually salient alternatives except for p itself (exclusive component). So our preliminary semantics for zhi looks as follows. It takes a proposition p, the prejacent, asserts p to be true (17-a) and none of p’s non-identical alternatives p\('\) to be true (17-b). Alternatives are restricted to C, a set of contextually salient alternatives.

The assertion in prose:

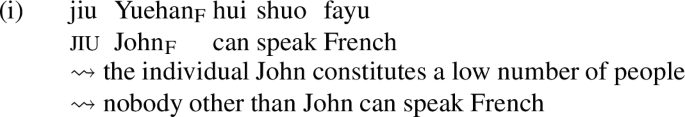

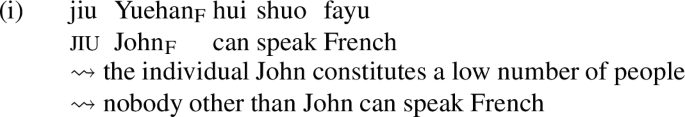

Let us now look at the simple sentence in (19), which has both the positive and the exclusive implication. The subscript \(_\text {F}\) signals focus-marking.

The alternatives in C can be thought of in two different ways here: namely, as differing or not differing in logical strength. In C1, they don’t, in C2, they do, and [\(_\text {p}\) LW ate a cherry] is asymmetrically entailed by its non-identical alternatives.

On either way of thinking of C, the working semantics in (17) derives the positive and the exclusive implication we observed.

There are well known refinements to such an analysis. Consider a case with focus on the numeral liang ‘two’:

In this case, the prejacent has a conceivable weaker alternative, that LW ate one cherry, that we do not want zhi to exclude: the truth of [\(_\text {p}\) LW ate two cherries] is implied—and on the present analysis, entailed. p entails that Little Wang ate one cherry, so the positive and the exclusive implication seem to be incorrectly predicted to contradict each other. One reaction to this has been to assume that only only excludes alternatives that are not entailed by p. In defense of the working analysis, one could follow e.g. von Fintel (1997) in considering weaker alternatives not to count as relevant, hence to be banned from C to begin with. As a result, our weaker alternative that LW ate one cherry is not asserted to be false, and the contradiction doesn’t arise.

The rich literature on exclusives offers other refinements to the entry in (17), which pertain to the so-called prejacent-implication and the implication that the prejacent ranks low on a scale.Footnote 11 Scalar lowness will become crucial in the context of zhiyao. But (17) should suffice for the analysis of zhiyou to follow.

2.2 you ‘have’

You has a whole variety of uses exemplified in the following two sets of examples, both of which have one thing in common: existential quantification. The three examples in (23) come with existential (\(\exists \)) quantification over individuals. The first of two properties ascribed to these individuals (the expression denoting this property, to be more precise) sits in the subject NP: the property of being a person, a story, and a cat, respectively. In (23-a) and (23-b), you precedes a subject-internal determiner, yige ‘a’ and xie ‘some’. This is not the case in (23-c), which has a determinerless subject.

These examples can be informally paraphrased as follows:

The adverbial uses in (24-a) and (24-b) differ from the preceding examples in the type of entities existentially quantified over: (24-a) comes with \(\exists \)-quantification over times, (24-b) over worlds. In other words, the former use is temporal, the latter modal.

The corresponding paraphrases no longer involve individuals, but existential force remains in place:

The use called modal here is of particular interest: if there is a modal version of you, this would be the candidate to be part of conditional zhi-you. Let us first look at the general pattern that seems to emerge for you on the basis of the examples just given. We can derive (25), according to which you takes two properties p and q, and ascribes them to an entity x that it existentially quantifies over, be x an individual, a time, or a world.Footnote 12

What we may want is a modalized version of (25), an existential quantifier over worlds. Accordingly, p and q are now properties of worlds (of semantic type s,t).

It’s not quite as easy as that though. Starting with the temporal case (24-a), it is far from clear that you itself takes on a temporal meaning. This temporal specification rather seems to arise compositionally, namely by virtue of shi ‘time’ in you-shi serving as you’s first argument p. We get an LF like (24-a) and an interpretation like (27-b), but you seems to remain a quantifier over an underspecified x in this case, not over a time in particular.

The modal variant is even trickier. What you immediately combines with is the possibility modal keneng, which albeit translates as ‘possibility’ in this case. So a paraphrase of you-keneng that is faithful to its internal composition would be something like ‘there is a possibility that’. In analogy to shi ‘time’ denoting a set of times, we may treat keneng as denoting a particular set of worlds, namely those that are epistemic alternatives in the sense of being epistemically accessible, say, to the speaker:

If this is on the right track, we are in a position to treat the modal example in (24-b) in a parallel fashion to the temporal one. In the LF in (29-a), the two arguments of you are now two properties of worlds rather than times, type s,t.

Still, concerns raised by a reviewer on the existence of a modal you like the one in (26) remain in place. For one thing, you itself does not seem to quantify over worlds here, just like it does not seem to quantify over times in the temporal case. Worlds are only brought into play by keneng, and all that you seems to add is quantificational force. For another, the same reviewer also points out that you, unlike zhi-you, cannot serve as a conditional connective:

What we see in (30) seems to touch on a more general idiosyncrasy of zhiyou, which complicates a decompositional analysis. Informally speaking, it seems that zhiyou leads a life of its own, in our case: functions in environments in which you itself does not. This dichotomy between zhiyou and you arises in monoclausal environments as well. Sun (2021): 322, footnote 3 observes bare you to exhibit the so-called definiteness restriction, brought to prominence by Milsark (1974). The following pair of monoclausal examples illustrates this: zhiyou has no trouble associating with the proper name Lao Wang in focus, (31-a). By contrast, it seems hard to make sense of a maximally similar sentence with bare you, (31-b).

zhiyou is more than the sum of its parts. Should these idiosyncrasies discourage us from entertaining the modal variant of you? I don’t have a satisfying answer to this problem, and keep entertaining the modal entry in (26) as an auxiliary assumption, with the stipulation that its appearance is limited to conditional zhiyou. The latter may or may not have formed in analogy with zhi-yao, the second part of which is clearly a modal, as will also be argued for below. Be this as it may, what the entry in (26) does keep in its favor, I think, is that it is just a specification of the less controversial type-neutral entry provided in (25).

2.3 zhi-you

We saw at the beginning that zhiyou resembles only if in coming with necessity, but not with sufficiency. This subsection derives this in a compositional fashion, based on the above entries for zhi ‘only’ and modal you ‘have’. If these two entries (and especially the latter of the two) are accepted, zhiyou does not cause the same problems that only if has caused in the past (von Fintel 1997; Herburger 2019): the modal you contained in it would openly deliver the very same \(\exists \)-force that Herburger (2019) posits only if conditionals to have.

The following zhiyou-conditional will serve as the basis for the analysis to come.

The (non-)implications we want to derive are

-

insufficiency: there is a chance for the speaker not to go even if the hearer goes

-

necessity: there is no chance for the speaker to go if the hearer does not go

In line with a suggestion made by a reviewer, the aim is to work out a single lexical entry for zhiyou, which is a lexical unit despite its internal complexity.Footnote 13 This suggests a constellation like (33-b) rather than (33-a), where zhi outscopes an entire modal claim headed by modal you, which as we saw in the previous subsection doesn’t occur in isolation anyway.

To work out option (33-b), a higher-type zhi which takes modal you as an argument is required. The entry from above, repeated in (34), will not do.

Drawing inspiration to some extent from the type-shifts in Coppock and Beaver (2014), (35) derives such a higher-type version, zhi\('\). Its first argument slot R will later on be saturated by modal you, the p- and q-slots by the antecedent and the consequent, respectively. R stands for a function that takes two propositions and returns another proposition.Footnote 14 The contribution of zhi\('\) is to apply the simpler zhi to R(p)(q), the proposition resulting from R’s application to p and q. As a result, we get the conjunction of R(p)(q) together with the negation of any proposition R(p\('\))(q), where p\('\) is an alternative other than p.

To get to the entry for conditional zhiyou, modal you is inserted for R. The entry for the former is repeated in (36), with the intensional step of having it take an evaluation world as its third argument.

With these ingredients in place, the semantics of zhiyou is derived in (37). What we end up with is an operator that takes two propositional arguments p and q. Its assertive contribution conjoins the existential claim that p and q are both true in some world w\('\) with the negative claim that no alternative p\('\) other than p is going to verify this existential claim. In other words: there is no world w\(''\) that makes both p\('\) and q true.

Let us apply the semantics proposed for zhiyou in (37) to the example in (32). We get an LF like the following.

If we now take the last line from (37) and substitute p and q with the concrete propositions from (38), we get (39-a), which is paraphrased in (39-b):

The contextually salient alternatives in C are all alternatives to the focused antecedent p, including p itself. So in a context in which besides the hearer’s going, Mary’s and Henry’s going are entertained as possibilities, C looks like this:

When C is as in (40), the exclusive second conjunct of the truth conditions in (39) entails that there is neither a way for the speaker to go in the event that Mary goes, nor in the event that Henry goes. This captures necessity, which amounts to a negated existential claim. The negation comes from zhi’s exclusive second conjunct, existential force from you. Both of these components are overtly realized by zhi-you.

The same goes for insufficiency. The prejacent-implication of zhi re-asserts the existential claim coming from you, delivering the respective first line of (39-a) and its paraphrase in (39-b): there is some world w\('\) in which the hearer’s going coincides with the speaker’s. This allows there to be worlds in which the hearer goes, but the speaker doesn’t.

So under the assumptions made about zhi and you here, both insufficiency and necessity can be derived on the basis of overt material. This transparency should not be taken for granted: it has proven quite difficult to derive the necessity-implication exhibited by English only if conditionals in a compositional fashion (von Fintel 1997; Herburger 2015, 2016, 2019). The quantificational force of such conditionals does not manifest itself overtly. Plain if-conditionals come with sufficiency, hence warrant the assumption of having universal rather than existential force.Footnote 15 But universal force cannot be maintained for only if conditionals without further assumptions: the exclusive component of only ends up negating universal rather than existential claims. Herburger (2019)’s take on this problem is to assume a principle called Conditional Duality (cd): conditionals have existential force in negative (downward-entailing) environments, including the one created by only, and universal force otherwise. Under the present account of zhi-you, the latter wears existential force on its sleeves, so there is no need to resort to cd in dealing with it.

2.4 Monoclausal zhiyou

The above analysis covers conditional, biclausal zhiyou. Can it be extended to nonconditional, monoclausal zhiyou as illustrated in the following example repeated from the introduction?Footnote 16

Such an extension seems motivated in that the two kinds of zhiyou seem to give rise to analogous implications. In the biclausal cases, the two relevant implications were necessity and insufficiency. These seem to carry over to monoclausal examples like (41). Necessity figures as plain exclusiveness here: the implication that Old Wang drinks nothing other than tea. Just like conditional zhiyou’s necessity, exclusiveness can be shown to be uncancelable:Footnote 17

We also seem to have something analogous to insufficiency. (43-b) is an attempt at an insufficiency-continuation, and it seems to work fine. One may think of a scenario in which Old Wang disprefers certain kinds of tea, or sometimes simply doesn’t feel like having tea at all.

As a reminder, the entry for bi(clausal) zhiyou repeated from above looked as follows:

The task is to derive mo(noclausal) zhiyou from (44). The biclausal variant takes two propositions, i.e. properties of worlds, and quantifies over both propositions and worlds. The monoclausal one can be conceived of as taking two properties of individuals, and as quantifying over both properties and individuals. Its semantic type would then be that of a generalized quantifier, et, \(\langle \)et,t\(\rangle \):

This says that there is an individual x of which properties P and Q both hold, and that for no alternative property P\('\) different from P is there an individual y that both P\('\) and Q are true of.

Here is a possible LF for the example in (41). P is now satisfied by the property of being tea, Q by the property of being drunk by Old Wang.

Based on the entry in (45), we predict (46) to have the following truth conditions:

In the respective first line of the a- and b-variants in (47), zhi’s prejacent-implication figures as the existential claim that there is some x that is tea and that Old Wang drinks. This is in line with the insufficiency-implication, some evidence of which we saw in (43): for something to be tea is not a guarantee for it to be drunk by Old Wang.

As already mentioned in Sect. 2.2, Sun (2021) notes a problem for any decompositional take on zhiyou, including this one: unlike you, zhiyou easily associates with foci on definite NPs, including proper names, as illustrated in (48).

It is clear that the entry for monoclausal zhiyou given in (45) doesn’t work without further ado here, one potential solution being a type-shift of the NP in focus.Footnote 18

Leaving it at that, I will turn to zhi-yao ‘only-need’ next. Here the modal following zhi has universal rather than existential force, and the relevant implications are the reverse of those for zhi-you: (minimal) sufficiency comes, necessity goes. The next section aims to capture both aspects of zhiyao’s meaning.

3 zhi-yao ‘only-need’

Zhiyao was stated above to come with minimal sufficiency: sufficiency plus scalar lowness of the antecedent p. p’s lowness is another implication we need to account for. Before getting into possible analyses, let’s take a brief look at the kind of scalar lowness zhiyao conveys.

3.1 Scalar lowness

Take the sequence of conditionals in (49). Only the second conditional has zhiyao in it. (49-b) is slightly odd, an intuition one may ascribe to a lowness-requirement coming from zhiyao: the only alternative antecedent provided in the context, that Mary comes, is logically weaker, hence scalarly lower, than the one zhiyao combines with, that Mary and John come. This conflicts with the assumed lowness-implication: Mary’s and John’s cannot count as low in the given context, given that the only alternative available is even lower.Footnote 19

It doesn’t seem far-fetched to ascribe zhi-yao’s scalar lowness to the zhi it contains: after all, only is well known for implying scalar lowness as well, cf. Guerzoni (2003), Grosz (2012), Liu (2017a), Greenberg (2019) a.o. In fact, the oddity seen in (49) disappears if zhi-yao is replaced by the conditional connective yao-shi ‘if’ (lit.: ‘need-be’), which contains yao, but crucially lacks zhi. The felicity of (50-b) can be ascribed to scalar lowness being absent from yaoshi.

How low does zhiyao rank its antecedent? Greenberg (2019) defends the view that only requires its prejacent to be the lowest in the context—and not, say, lower than most of its available alternatives (Grosz 2012). In answering the question for zhiyao, we may vary a diagnostic applied by Greenberg (2019): the context makes salient a lower and a higher alternative, created here by lower and higher numbers of peaches eaten. If zhiyao wants the antecedent to rank lowest, then the saliency of a higher alternative does not suffice for zhiyao to be felicitous. This is in fact what is suggested by (51).Footnote 20

Zhiyao is odd here because it wants three to be the lowest number of peaches eaten, but the context makes salient the even lower number one.Footnote 21

To take stock: zhiyao comes with scalar lowness, in the sense that the antecedent p is implied to rank lowest on a contextually salient scale. (52) provides a lexical entry that captures this insight. Zhiyao is treated as a conditional operator with a special presupposition.Footnote 22 Following previous analyses of exclusive particles such as Liu (2017a)’s and Greenberg (2019)’s, it is treated as triggering a minimality-presupposition of sorts, (52-a): every alternative proposition p\('\) that is different from the antecedent p ranks higher on a salient scale than p. This presupposition coincides with the standard conditional assertion that all (closest) p-worlds are q-worlds, (52-b).

Of course, (52) ignores the internal make-up of zhi-yao ‘only-need’. We want to derive this meaning in a compositional fashion. Before doing so, some more clarity needs to be gained about the two ingredients zhi and yao. A semantics for zhi has already been provided in 2.1. However, it seems worthwhile to refine it a bit in light of the role scalar lowness has come to play by now. After this refinement, some data involving yao will be considered to motivate its treatment as a necessity modal, hence as a universal quantifier over possible worlds.

3.2 zhi, again

In decomposing zhi-yao, one may want to assign the scalar lowness presupposition to zhi, enriching the semantics given for this exclusive particle in Sect. 2.1. Before doing so, let us briefly convince ourselves that zhi comes with lowness, independently of whether it combines with yao or not.

Take (53), with the numeral part of the object NP in focus. In addition to the positive and the exclusive implications we have already convinced ourselves of, two cherries are also conveyed to be low in number.Footnote 23

Analogous to other exclusives, scalar lowness is sometimes zhi’s sole contribution. An example of this sort is (54). The context makes salient a ranking of fruits depending on their sizes. The zhi-sentence has the object noun yingtao ‘cherry’ in focus. The effect of zhi in this case is a so-called rank order reading (Coppock and Beaver 2014): a cherry is conveyed to be small in size. The exclusive implication that Little Wang didn’t eat anything besides a cherry is rather uninformative in this case, compared to the same sentence without zhi.Footnote 24

The propositional alternatives made contextually salient vary along the object noun (the fruit eaten).

From this set of propositions, zhi excludes the peach- and the melon-alternatives, which, again, is hardly informative in that the prejacent is already about the single fruit that Little Wang ate. The lowness-implication that a cherry is small in size is compatible with default assumptions about fruits and their sizes: a cherry is smaller than both a peach and a watermelon.

As we did for zhiyao above, we can once again apply Greenberg (2019)’s diagnostic and check if it is indeed minimality we are dealing with, in the sense that zhi ranks its prejacent lowest among its alternatives. The data point in (56) suggests this to be the case. (56) varies the previous example to the effect that the fruit eaten by Little Wang, which is a peach this time, is no longer the smallest in the context: John ate a cherry, hence an even smaller one. This results in a certain oddity of the zhi-sentence, in spite of the fact that a larger fruit, the watermelon eaten by Mary, is also salient.Footnote 25

Based on scalar lowness, we can now enrich our initial lexical entry of zhi with the scalar presupposition already assigned to zhiyao in the preceding subsection, making our working semantics for zhi look a bit more like the kind of only that Greenberg (2019) ascribes to Guerzoni (2003) and refers to as ‘hybrid’: the prejacent p is presupposed to rank lowest on a salient scale, (57-a). The assertion remains as previously assumed.Footnote 26

Before moving on to yao, a quick note on the notion of scalar lowness and its relation to propositional strength. It is safe to assume a positive correlation between the two: the stronger a proposition, the higher on a scale. (54) provides an example where alternatives do not differ in strength, and the scale is purely pragmatic (related to fruit size).Footnote 27 So scalarity is to some extent independent of entailment. A question already touched upon in footnote (21) is whether this independence is limited in the sense that entailment, if present, dictates the scalar ranking holding between alternatives. The following example suggests this to be the case. The context in (58-a) enforces a negative correlation between an effort and an entailment scale: the less peaches one eats, the more effort it takes; put differently: the stronger an alternative is, the lower it ranks on the effort scale. In this context, zhi infelicitously combines with the stronger proposition (58-b):

This suggests that zhi disallows for a given entailment scale to be pragmatically overwritten.

3.3 yao ‘need’

The modal yao displays a striking range of uses reflected by the various translations it may receive. As seen in (59), yao may translate as ‘want’, ‘will’ or ‘need’.Footnote 28

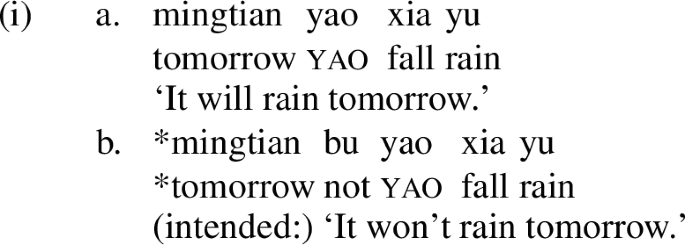

This range of uses is likely to be one of modal flavor rather than force, the underlying core meaning being one of (strong) necessity, i.e. universal quantification over possible worlds.

The fact that yao expresses the speaker’s desire to get a new cell phone in (59-a) can be ascribed to its taking on a bouletic (desire-related) flavor. want is treated as a universal quantifier over possible worlds under Heim (1992)’s influential analysis defended by Rubinstein (2017), the latter also putting forth a unified view of necessity modals and want-like attitude verbs. Yao supports such a view by virtue of instantiating both classes of verbs.

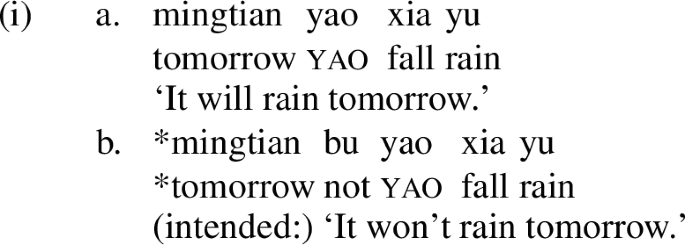

The future use in (59-b) is expected under an account that treats the future auxiliary will as a necessity modal, not as a tense operator, a view Iatridou (2000) ascribes to Palmer (1986), among others.Footnote 29

The data set in (59) suggests yao to be a necessity rather than a possibility modal, that is, to differ from you ‘have’ in being a universal, rather than an existential, quantifier over possible worlds. This is captured in (60), a lexical entry that otherwise resembles the one given for modal you above: yao takes two propositions p and q, the first of which restricts quantification over q-worlds. In the conditional uses (yao-shi, zhi-yao), this slot is to be satisfied (in part at least) by the antecedent clause.Footnote 30

This entry may leave a lot to be desired, but should suffice for given purposes. Xie (2022) takes a closer look at both of the following issues: for one thing, the range of modal flavors yao allows, to the exclusion of others; for another, the question of whether yao is a weak or a strong necessity modal, though see the appendix for some preliminary discussion. Under a prominent view, necessity is weakened via a restriction on the domain: the set of worlds quantified over (von Fintel and Iatridou 2008; Rubinstein 2014; Vander Klok and Hohaus 2020). Under this view, yao’s force remains universal, no matter how we settle the question whether it is weak or strong. In other words, we can keep the entry in (60) no matter what.

3.4 A compositional challenge

We have defined the ingredients of zhi-yao; now comes the task of deriving its contribution in a compositional fashion. This turns out to be trickier than in the case of zhi-you.

An obvious first thing to do would be to treat zhi-yao in a parallel fashion as zhi-you is treated in Sect. 2.3. This requires, again, working with zhi\('\) a type-shifted variant of zhi\('\) that can take yao as an argument. The new zhi repeated in (61-a) differs from the old one in presupposing the prejacent to be low. The zhi\('\) derived from this is given in (61-b). Its R-slot is to be filled by yao, and what is presupposed to be low is its first propositional argument p, which is in focus.

To apply zhi\('\) to yao is to insert the latter for R in the second line of (61-b). This is what happens in the third line of (62).

What this analysis derives is, for one thing, the antecedent p’s presuppositional evaluation as low. For another, the prejacent-implication (the first conjunct of the assertion) ensures p’s sufficiency for q. Both of these aspects are welcome. At the same time, however, we end up with there being no salient alternative p\('\) that is both different from p and suffices for q. In other words, the second conjunct fails to derive the intuitive meaning of zhiyao, which is at least neutral regarding the question of whether some alternative antecedent p\('\) suffices for q, if there isn’t even an additive implication that any such antecedent verifies q as well, as will be argued below. These undesirable results are reminiscent of challenges von Fintel and Iatridou (2007) (henceforth: vF &I) tackle in their (de)compositional analysis of only have to, which is hence worth taking a look at.

vF &I’s working example is the following:

Just as in the case of zhi-yao, an exclusive particle (only) and a necessity modal (have to) conspire to convey minimal sufficiency: roughly, that going to the North End is an easy means to get good cheese. The analysis vF &I end up proposing crucially involves a decomposition of only into a negation, called ne here, and an exceptive component que, which asserts something other than the prejacent to be true:Footnote 31

In addition, que is assumed to split from ne below the necessity modal \(\Box \) denoted by have to. What is crucial for present purposes is that \(\Box \) is taken by vF &I to be silently restricted by the proposition denoted by the infinitival purpose clause to the left, to get good cheese. We start out with a highly simplified LF like (65-a), outscoped by only, with the purpose clause proposition acting as a silent restrictor to \(\Box \).Footnote 32 After decomposition and que’s lowering under \(\Box \), we get (65-b): que takes immediate scope with respect to the proposition \(\phi \), that you go to the North End. Its truth conditions are informally paraphrased as in (65-c).

What matters most for given purposes is the combinatorics involving \(\Box \) and its arguments (Hole 2004, 2006). For one thing, zhiyao seems to differ from only have to by (sometimes) acting as a genuine conditional connective, combining with two overt propositions. Here is a possible Mandarin version of (63), which closely resembles an example presented in Hole (2006):Footnote 33

From (63), we can derive an LF like this:

Comparing the LFs in (67) and (65-b), it seems that the order in which zhiyao combines with the two propositions in question is the reverse of that in which only have to does: [\(_{\phi '}\) good cheese], the restrictor of have to, is the nuclear scope of zhiyao, and vice versa, the nuclear scope of have to, [\(_\phi \) go to the NE], is zhiyao’s restrictor.Footnote 34

Here is a summary of this combinatory reversal:

Mandarin (66) evokes a temporal succession between restrictor and nuclear scope just as we tend to find it in ordinary conditional constructions: [\(_\phi \) go(ing) to the NE] temporally (and causally) precedes [\(_{\phi '}\) get(ting) good cheese].Footnote 35

However, Hole (2006) takes steps towards a vF &I-style treatment of zhiyao: for one thing, he assumes the latter to contribute negated universal quantification, albeit over focus alternatives rather than possible worlds. For another, he assumes the order in which zhiyao takes its arguments to reverse at LF: the matrix clause [\(_{\phi '}\) get good cheese], rather than acting as the nuclear scope, is mapped to zhiyao’s restrictor. As a result, the linear order of arguments is in fact vF &I’s, \(\phi '\) > \(\phi \), and the resulting LF looks something like this:

By contrast, the analysis to be spelled out in the following subsection will preserve surface order and take the LF in (67) to be the input to semantic interpretation, even though another reversal is going to happen.Footnote 36

3.5 Inverting zhi-yao

This subsection pursues an inverse scope treatment of zhi-yao, which is shown to deliver desirable results. zhi’s exclusive force becomes innocuous, scoping below yao and above the antecedent. There is some prima facie motivation for such an analysis considering that yao appears to be a neg-raising modal: a negation that precedes yao on the surface appears to scope below it at LF. The following song line may serve as an illustration. It clearly reads as a prohibition, not as a permission not to pick wild flowers along the road, despite logical compatibility of these two readings

Exclusive particles negate (certain) alternatives. So zhi, too, is a negative item of sorts. And if overt negation scopes below yao, one might expect zhi to do so as well. Some more neg-raising data are provided in section two of the appendix.

In deriving a lexical entry along these lines, we essentially take the step from (71-a) to (71-b).

The configuration we get is reminiscent of one investigated in depth by Grosz (2012): minimal sufficiency conditionals in which only appears in a conditional antecedent, conveying the proposition denoted by the latter to rank low on a scale. A German example involving nur ‘only’ is given in (72-a), an LF for it in (72-b).

The zhi we have in (71-b) is no longer the typeshifted variant zhi\('\), but the simpler one. Given the derivation to follow, it now makes sense to define an intensionalized version of this simpler zhi, one that takes a world argument w in addition to the prejacent:

Having defined this intensional zhi, we can continue to work out our lexical entry based on the structure derived in (71-b). The antecedent is again presupposed to rank low on a scale, (74-a). The final assertion is in the second line of (74-b) and boils down to this: in all worlds w\('\) in which p and no other salient p\('\) holds, q holds as well.

Let us apply this semantics to a concrete example, repeated from (2-a):

The two implications we would like to capture are

-

sufficiency: three cats make her happy

-

lowness: three cats are low in number

Our example gets the following LF:

If focus is on the numeral, the alternatives in C vary according to the number of cats showing up:Footnote 37

The interpretation of (76) can now be derived by taking the entry in (74) and inserting [\(_\phi \) 3 cats come] and [\(_{\phi '}\) she’s happy] for p and q, respectively.

Presupposition and assertion can be paraphrased as follows.

The assertion can be simplified as follows:Footnote 38

On a closer look at the assertion, a potential complication regarding sufficiency arises: the pronominal referent is asserted to be happy in worlds in which exactly three cats come. But we would like her to be happy in any kind of world in which three cats come, including worlds in which four or five come. In other words, under the derived assertion the coming of three cats does not actually seem to be sufficient for her to be happy.

This points to a potential problem in the characterization of zhiyao-conditionals as implying sufficiency. It does not seem to reveal a problem with the analysis itself. Zhiyao-conditionals can be shown to be nonmonotonic just like other conditionals have been observed to be (von Fintel 2011a; Liu 2017b). This is suggested by the following Sobel-sequence, whose first member is a zhiyao-conditional:

The zhiyao-conditional in (81-a) does not entail just any kind of world in which Mary comes to ensure the speaker’s happiness, or else the continuation in (81-b) would come out odd. This is predicted by the present analysis insofar as it ascribes a weaker assertion to (81-a): that the speaker is happy as long as no one other than Mary comes. This is fully compatible with her no longer being happy as soon as both Mary and John come.

Still, zhiyao-conditionals do seem to trigger an additive, albeit cancelable, inference of sorts, to the effect that any stronger proposition than the prejacent-antecedent will verify the consequent as well, and we do get sufficiency after all, even if it is not part of zhiyao’s lexical semantics. It is probably by virtue of this additive inference that (82-b) can be understood as an affirmative answer to (82-a):Footnote 39

The following subsection tackles this additive inference. In so doing, it also captures sufficiency, which seemed absent from the truth-conditions derived in this subsection.

3.6 Additivity

The additive inference just mentioned is plausibly licensed by the scalar presupposition triggered by zhiyao, according to which any alternative p\('\) but the antecedent p itself is stronger than p. Given the assertion that all worlds in which nothing but p holds are worlds in which the consequent q holds, it is easy to infer that any other p\('\), presupposed to be stronger than the q-verifying p itself, will verify q as well.

It is not by coincidence that this kind of reasoning is reminiscent of Rullmann (1997)’s regarding the additivity of even. More recent work such as Crnič (2011, 2012) returns to the more traditional view that even triggers an additive presupposition. This crucially includes Panizza and Sudo (2020), who propose that even is overtly or covertly involved in minimal sufficiency readings of English just. If we follow this line of work, the additivity (and sufficiency) of zhiyao can be derived by inserting an even-operator on top of a zhiyao-conditional’s LF. This operator asserts nothing, but triggers two presuppositions. One of these two is an additive one, a universal variant of which is provided in (83-b).

So we may enrich the LF for (75) given in (76) by placing silent even on top. The latter associates with the same focus as zhiyao, even though its alternatives are structurally more complex:Footnote 40

Silent even takes the entire zhiyao-conditional \(\psi \) as its prejacent, and presupposes all of \(\psi \)’s non-identical alternatives q to be true, given (83-b):

Since even’s alternatives in C\('\) and zhiyao’s in C associate with the same focus, they vary along exactly the same lines, in this case the numeral.

For the sake of simplicity, let us informally paraphrase the alternatives in C\('\) along the lines of (80):

According to the presupposition in (85), any C\('\)-alternative other than \(\psi \) holds true: the coming of exactly 4 cats and the coming of exactly 5 cats are both presupposed to make her happy. Any alternative antecedent in C is thus presupposed to make the consequent true, which in the case at hand means that any relevant number of cats higher than 3 is presupposed to make her happy.

If this is on the right track, what remains puzzling is the ease with which zhiyao licenses silent even. This cannot be taken for granted, as is revealed by a look at German conditionals of the form if only p q. Grosz (2012) observes that such conditionals are in principle ambiguous between an exclusive and a minimal sufficiency reading, and that it usually takes an overt particle like even in the consequent for the minimal sufficiency reading to arise. Here is a variant of the examples he provides:

In the absence of even, there is a preference for an exclusive reading, according to which she’s implied to no longer be happy if more than three cats show up. even-insertion, by contrast, enforces the minimal sufficiency reading that any number of cats higher than three will make her at least as happy as three do.Footnote 41

Mandarin zhiyao is not ambiguous in the same way as wenn nur ‘if only’. It has a clear minimal sufficiency reading, which does not require any special particle in the consequent to be enforced. To be sure, the consequent has jiu in it, but its presence seems to be dictated by the very presence of zhiyao, possible exceptions taken aside (Hole 2004):

I hope for future work to shed some light on why zhiyao and wenn nur come apart in this way.

3.7 Monoclausal zhiyao?

As mentioned in the introduction, zhiyao has potential monoclausal uses like zhiyou does, even though the situation is not as clear:Footnote 42

What (90) seems to convey is that Old Wang is fairly unselective when it comes to tea. The two (non-)implications we ascribed to biclausal zhiyao, sufficiency and non-necessity, seem to roughly carry over. This is suggested by the continuations in (91). The sufficiency-denying continuation in (91-a) feels odd to four out of seven Mandarin speakers. By contrast, seven speakers accept the necessity-denying continuation in (91-b).Footnote 43

In analogy to how zhiyou was treated above, it seems tempting to assume a typeshifted variant of our bi(clausal) zhiyao to be at work in (90). As a reminder, this is what the latter looks like:

The mo(noclausal) counterpart would then again be a quantifier over individuals which takes two properties:

This monoclausal variant would then be involved in an LF for (90):

Based on the entry in (93), we predict (94) to presuppose (95-a), and to ‘assert’ (95-b):

The property of being tea is presupposed to rank low on a scale, and all y that have no other property P\('\) but being tea are asserted to be drunk by Old Wang. One question that arises is how a property can be thought of as low in the first place. For concreteness, let us put (90) into a scenario in which someone asks if Old Wang drinks da hong pao tea, which seems to be quite expensive. As a result, we are dealing with the following two alternatives:

One may see the two elements in C as forming a value-scale, with da hong pao constituting the upper end. By virtue of its genericity, the focus predicate cha ‘tea’ is interpreted as ranking at least as high on the scale as the cheapest tea one can think of. The denotation of the focus predicate becomes (or rather remains) a superset of the denotation of its only alternative.Footnote 44 It is in terms of this superset-relationship that I consider lowness to be satisfied here, in analogy to the superset-relationship between a weaker and a stronger proposition.

As for the assertion in (95-b), it says that any y of which no predicate P\('\) other than tea holds—hence any y that is not (also) da hong pao tea—will be drunk by Old Wang. This seems intuitive enough. So while the formal details remain to be worked out, the present take on biclausal zhiyao inspires a plausible treatment of what might be its monoclausal counterpart.

4 Interaction with quantificational adverbs

One of this paper’s core observations was conditional zhiyao’s and zhiyou’s opposition regarding whether or not the antecedent is implied to be sufficient for the consequent:

This opposition in terms of sufficiency was explained on the basis of differences in quantificational force:

-

zhiyao is taken to bring universal force, given yao ‘need’

-

zhiyou is taken to bring existential force, given you ‘have’

As a reviewer points out, this explanation rests on a nonstandard assumption regarding the source of a conditional’s quantificational force. The present account locates it in the respective connective. But on the so-called restrictor view (Lewis 1973; Kratzer 1986; von Fintel and Heim 2011b), force comes from a modal or quantificational adverb in the consequent, henceforth referred to as q-items, and all a conditional connective does is to introduce the antecedent as a restriction on the operator denoted by that item. It is hence an interesting question to ask how zhiyao and zhiyou interact with a q-item that doesn’t match their assumed force—more concretely, when

The same reviewer exemplifies both combinations, and checks whether they can be felicitously followed up by denying sufficiency.

Following (99-a), which instantiates (98-a), sufficiency is felicitously denied in (99-b): because of you keneng ‘possibly’ and despite zhiyao, diligence is no longer implied to suffice for success.

The same sufficiency-denying continuation seems to cause infelicity following (100-a), which instantiates (98-b): because of yiding ‘necessarily’ and despite zhiyou, diligence is implied to be not only necessary, but also sufficient for success.

In other words, the mismatching q-items in the consequents reverse the featural ascriptions given in (97). Does this follow from the present analysis, or does it indicate the need to treat zhiyou- and zhiyao-conditionals in terms of the restrictor view instead?

Under the present analysis, the q-items take narrow scope with respect to the consequent, such that their contribution remains in the scope of zhiyao and zhiyou, respectively. This turns out to be less problematic for the zhiyao-case in (99-a) than for the zhiyou-case in (100-a).

As for (99-a), we get an LF that looks roughly as in (101). The arguably most important part is the existentially modalized consequent \(\phi '\). \(\Diamond \) is supposed to represent the denotation of the complex expression you-keneng here, a compositional treatment of which was sketched in Sect. 2.2.

The predicted truth-conditions look as in (102), and say that in all worlds w\('\) in which you are diligent and nothing else (say, talented), there is a possibility for you to succeed.

So under the present account, the lack of sufficiency is actually predicted, in the sense that \(\Diamond \), spelled out as youkeneng, has a weakening effect. Success is not a reality in any of the worlds w\('\) universally quantified over; it’s just the possibility of success that is ensured in all of these worlds.

By contrast, (100-a) poses a much trickier challenge. The adverbial yiding ‘necessarily’ instantiates a necessity modal, \(\Box \). Now it’s the latter to take narrow scope with respect to the consequent \(\phi '\):

With the universal \(\Box \) being within the scope of existential zhiyou, we fail to capture both sufficiency and necessity. The first conjunct of the truth-conditions derived in (104) says that in some diligent world w\('\), success is a necessity. Given that necessity is non-actual, this even weakens the existential claim ascribed to zhiyou-conditionals without yiding. The second conjunct, once successful at capturing necessity, now says that in no w\(''\) in which you are something other than diligent do you necessarily succeed. This is undesirable in that it leaves open the possibility for you to succeed in some such w\(''\).

What we want instead is a hybrid approach like (105): in the first conjunct of the assertion, \(\Box \) takes over as the restrictor view has it, supplying universal quantification and ensuring sufficiency, but is completely ignored in the second conjunct, where zhiyou makes its negated existential claim, ensuring necessity.

What we would like is a principled way of getting this result, which is a challenge I have to leave to future work. If there is any consolation to be found, it’s that at least as far as sufficiency is concerned, a definitely in an only if conditional’s consequent seems to have the same sufficiency-enforcing effect, as can be seen from the infelicity of the sufficiency-denying continuation in (106-b).

As far as I can see, (106) poses a similar challenge for Herburger (2019)’s treatment of only if conditionals as having existential force, at least as far as the emergence of sufficiency is concerned. At the same time though, the necessity-denying continuation in (106-a) seems to work, and this absence of necessity was predicted for the Mandarin case in (104).

To sum up this section, the present account correctly predicts zhiyao’s interaction with a non-matching q-item, but gets into some trouble when it comes to zhiyou’s, which seems to call for a hybrid approach of sorts.

5 Conclusion

This paper offered a decompositional analysis of Mandarin zhi-you ‘only-have’ and zhi-yao ‘only-need’, with the main focus on their biclausal uses as conditional connectors, but possible extensions to monoclausal uses. The following logical structures were proposed, assuming that you instantiates an existential modal (\(\Diamond \)) and, less controversially, yao a universal one (\(\Box \)):

If this account is on the right track, then zhi-you and zhi-yao are special by virtue of transparently wearing their respective modal force on their sleeves. The same cannot be said of English if-conditionals, whose modal force has to be posited, at least in the absence of modals in the consequent.

I conclude with some (more) remaining issues, both of which touch on scalarity.

5.1 only if conditionals and scalarity

In Sect. 3.2, zhi was endowed with a presupposition of scalar lowness, in line with many existing only-accounts. This lowness-presupposition was only discussed in the context of zhiyao, not of zhiyou. So, how does it factor into a proper treatment of the latter?

It is worth noting in this respect that zhiyou-conditionals tend to have scalar readings. The following example is a case in point.

Such examples seem to convey five cats to be high in number, so quite the opposite of lowness. Given this highness-effect, it seems that salient alternatives all involve numbers lower than three, and that the following alternatives are active by default:

It would be desirable to ascribe this highness-effect to zhi’s compositional interaction with a scale-reversing (or downward-entailing) operator, such that its lowness converts into highness qua focus association across such an operator, which is an assumption Crnič (2012) makes for conditionals in the scope of only. The lowness presupposition would shape the alternatives such that those involving higher numbers are ignored, an effect Krifka (2000) ascribes to other scalar particles.Footnote 45 But under the present analysis, zhiyou combines with the focus-containing antecedent directly, not with the conditional as a whole, and the structural simplicity of the alternatives in (109) reflects this. And even if the alternatives were entire conditionals, as they are assumed to be under all approaches to only if I am aware of, no scale-reversing, but a scale-preserving operator would be involved: the prejacent-conditional outscoped by zhi would be an existential claim rather than a universal one, given the assumed contribution of you ‘have’, and mean something like ‘some world in which three cats come is a happy world’. This asymmetrically entails, and is hence stronger than, the alternative claims of there being a happy world with {two, one} cat(s) showing up in it. So it is far from clear how the prejacent-conditional could be construed as weak with respect to these alternatives, and how zhi’s lowness-presupposition could give rise to highness-effects.

5.2 jiu and cai

zhiyao has to be followed up by the particle jiu in the consequent, zhiyou by the particle cai (Hole 2004, 2017):

And while jiu and cai cannot be deleted from the conditionals in (110), zhiyao and zhiyou can. The meaning seems to be largely preserved, subtle differences notwithstanding.Footnote 46 In other words, (111-a) is still a (minimal) sufficiency and (111-b) is still a necessity conditional.

In the end, something has to be said about the interaction between zhiyao and jiu on the one hand and zhiyou and cai on the other.

If there is no considerable change in meaning from (110) to (111), it seems fair to think of an agreement phenomenon holding between the respective connective and its matching particle. Such views have in fact been put forth, in some version or other; cf. Hole (2004), Tsai (2017), Wimmer (2021a) on jiu and Hole (2017) on cai, critically reviewed by Sun (2021). There are differing views as to which of the two items carries the actual semantics. Hole (2004), Tsai (2017) and Wimmer (2021a) treat postfocal jiu as semantically vacuous. By contrast, Hole (2017) and Sun (2021) treat zhiyou as vacuous.

It also raises the question as to which semantic features are involved in these sorts of agreement. The question of scalarity comes up again. But cai and jiu have both been disentangled from scalarity, which has been argued to be a marginal pragmatic effect these particles occasionally come with (Hole 2004; Sun 2021). It seems that the only safe thing to do is to endow cai with an exclusive feature. jiu’s featural characterization remains open, even though it is also exclusive under Liu (2017a)’s analysis. Loosely following Tsai (2017) and Zhang and Jia (2017), it is tempting to endow jiu with a sufficiency-feature of sorts. But such an ascription runs into similar problems in that jiu is well known for its temporal uses, which a sufficiency-ascription seems to fall short of capturing. In other words, there remain quite a few puzzles to be solved.

Change history

02 December 2022

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note

Notes

When the internal composition of these two items is not immediately relevant, hyphens will henceforth be omitted between their parts.

For convenience, I will use the terms ‘antecedent’/‘consequent’ interchangeably for the two respective clauses involved in a conditional as well as for the propositions they denote.

Example found online, https://www.ixigua.com/6769792101723931143? &wid_try=1 [2020/12/22].

The definition in (5) sidesteps problems of temporal order that a more elegant definition of necessity in terms of sufficiency would face (Horn 1996; Herburger 2019). On that definition, necessity is defined in terms of sufficiency, and all that changes is the direction of verification: p is necessary for q iff q suffices for p.

The sentences in (2-a) and (6) aren’t exact minimal pairs in that the different connectives require different co-occurring particles in the consequent: a zhiyao-conditional has the particle jiu; a zhiyou-conditional has the particle cai in the consequent. Also, only (2-a) ends with the aspectual particle le. Another change in meaning from zhiyao to zhiyou that sometimes seems to occur is one in scalarity (Sun 2021 on cai): (6) no longer conveys a smile to be easy, but rather a hard thing, to put into action. It is in this sense that zhiyou may sometimes convey maximality (highness) rather than the minimality (lowness) just ascribed to zhiyao. For discussion of some of these issues, see this paper’s conclusion.

One may object that the possibility modal neng ‘can’ in the consequent of (9) acts as a distorting factor here, weakening zhiyou’s sufficiency. However, it seems that the pattern remains the same if hui ‘will’ is used instead. This is not to claim that modals in the consequent never make a difference, cf. Sect. 4.

A reviewer raises the question whether zhiyou patterns with only if in all possible respects. One more aspect in which they certainly pattern the same is that having the consequent temporally precede the antecedent without further ado leads to oddity, an effect the observation of which von Fintel (1997) and Herburger (2019) ascribe to McCawley (1993).

Six out of seven native speakers sensed an inconsistency between (11) and (12-a) (or a slight variant thereof), even though one of those six still found this sequence natural. Two out of three liked (11) + (12-b); the third one explicitly stated that (12-b) does not contradict (11), but is merely an unusual thing to say.

Sentences like (14) do not seem to be accepted by all speakers of Mandarin, which might be due to regional variance.

As for the prejacent-implication, Horn (1996) traces the ‘conjunctionalist’ view entertained here back to the medieval philosopher Peter of Spain. Nowadays it is more standard to take p as presupposed rather than asserted (Horn 1969; Alonso-Ovalle and Hirsch 2018), or its truth to be derived on the basis of an interplay between a weak presupposition and the exclusive assertion (Horn 1996; Coppock and Beaver 2014; von Fintel and Iatridou 2007).

The definition in (25) arguably deviates from Cheng (1994)’s, who treats you as an existential closure operator.

The same reviewer provides the interesting argument that zhiyou cannot associate with a focus outside p. Indeed, if such an association were possible, p’s necessity for q should be defeasible via focus placement on q, which does not seem to be the case. Under the analysis to follow, zhi continues to take semantic scope with respect to q, by virtue of taking q as an argument.

The type-label p is an abbreviation for the propositional type s,t, again following Coppock and Beaver (2014).

Thanks to a reviewer for raising this question.

While three consultants judged the additive continuation in (42-b) to be fine, four saw (a slight variant of) it as problematic.

Partee (2002/1986)’s ident-shift from type e to e, t offers itself here.

A consultant sees a plain contradiction between the two sentences. She writes that “in using [zhiyao], it is implied [Mary] alone will not make the speaker happy”. This contradiction may relate to a constraint observed by Grosz (2012): “while thresholds can be shifted downwards ..., they cannot be shifted upwards” (p. 147). In (49-b), zhiyao sets the threshold for speaker-happiness to be Mary’s and John’s (joint) coming. This contradicts the previous sentence, according to which Mary’s coming is by itself sufficient for the speaker to be happy. The very establishment of such a threshold is a different matter. Following ideas in Lai (1999) and Beck (2019), one might see threshold-readings as the effects of scalar implicatures: zhiyao(p)(q) conveys p to be the lowest condition to make q true. Anything even lower than p is scalarly implicated not to make q true.

Four out of five native speakers felt (51-b) to be odd in the given context.

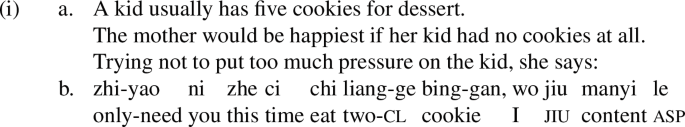

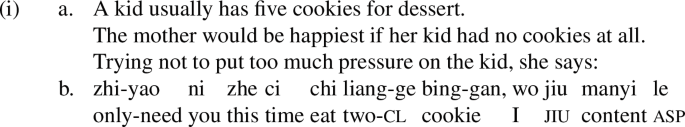

It seems that zhiyao allows the lowness of a proposition to be untied from numerical lowness, which translates into logical weakness of the resulting proposition. The context in (i-a), which I owe to Mingya Liu (pc), disentangles scalar lowness and logical weakness in the sense that the less cookies the kid eats, the more effort it has to invest.

The felicity of (i-b) may indicate a scalar difference between zhiyao and plain zhi: such disentanglements are not generally available for zhi, as example (58) given at the end of the following subsection suggests.

This is reminiscent of Schulz (2014)’s treatment of the difference between indicative and subjunctive conditionals. She assumes the LFs of both types of conditionals to involve variants of the necessity operator \(\Box \). These variants only differ in their presuppositions, not in their assertions.

Liu (2017a) observes prefocal jiu to also pair scalar lowness with exclusiveness:

Five out of six native speakers accept (54-b) in its context. The other one commented he needed more context to use zhi. The issue, I suppose, lies in accent placement. With accent on the numeral yi ‘one’, the context does indeed not license the use of zhi.

Three out of five informants saw an issue with (56-b) in its context. A sixth also dispreferred zhi, but probably for reasons other than fruit size, cf. footnote 25.

The exclusive assertion conspires with the scalar presupposition to imply all higher alternatives to be false: It rejects all of p’s alternatives except for p itself. The scalar presupposition restricts these alternatives to be higher than p.

yao is translated as ‘need’ in (59-c). This may suggest that this is exactly the variant we find in zhi-yao, glossed as ‘only-need’ throughout this paper. Still, there is an apparent difference in modal flavor: yao seems to be deontic (rule-related) in (59-c). But as a conditional connective, zhi-yao is more plausibly to be seen as epistemic (knowledge-related) or doxastic (belief-related). In other words, to utter zhiyao p q will often be a claim that p makes q true, given one’s knowledge or beliefs.

To be sure, future-oriented yao does not cover the same range of uses as will. To convey that something will not happen in the future, one cannot simply negate yao:

To be sure, (i-b) is not in and of itself ungrammatical. Five out of six native speakers accept it as an expression of a desire for rain not to fall tomorrow. Such cases are interesting not only because they illustrate yao’s neg-raising behavior, some more cases of which can be found below.

The domain of quantification is generally assumed to be subject to further restrictions one may vaguely subsume under the term relevance. Both maximal similarity to the actual world and modal flavor play a role here. To capture this, one could equip yao with more argument slots. A different option discussed by von Fintel and Heim (2011b) is to have the antecedent combine intersectively with these additional restrictions, allowing us to leave the number of arguments as is.

This move is motivated by languages like French, where exclusiveness tends to find its discontinuous expression in a negation (ne) and an exceptive (que) surrounding the main verb.

A more accurate analysis would have the purpose clause proposition be assigned to a propositional variable restricting \(\Box \), cf. von Fintel (1994).

What is ignored from (66) is the possibility modal neng ‘can’ in the consequent. In line with Hole (2006)’s paraphrase of his example, I assume neng not to replace zhiyao as the construction’s centerpiece, but to take narrow scope with respect to the consequent \(\phi '\). This derives a reading on which \(\phi \) ensures \(\phi '\)’s mere possibility. So the sentence ends up being about how easily this possibility comes about, in line with its intuitive interpretation: As vF &I observe, going to the North End in and of itself won’t bring one into the possession of good cheese. The hardest part may be over, but one still has to enter a store, look for good cheese in it and suchlike. neng can be seen as reflecting the need for these additional steps.

This matching between temporal and linear precedence is natural. A conditional paraphrase of English (63) sounds odd unless we form an anankastic conditional out of it, cf. footnote (34):

To be sure, Hole (2006)’s remarks on zhiyao are preliminary, and he explicitly leaves a deeper investigation to the future: “The recalcitrant fact is that it is not obvious how the overall type of focus quantification ... (\(\lnot \forall \)) can be matched with the ‘only’-word [zhi] plus the necessity modal [yao] in the subordinate clause ” (Hole 2006: 372; bracketed additions added).

The alternatives for zhiyao do not have to form an entailment scale as they do in (77). A nonlogical scale is equally conceivable. This is illustrated in Wimmer (2021a) for (what are assumed to be) minimal sufficiency conditionals in Mandarin and German.

That’s because zhi, apart from locally asserting [\(_\phi \) 3 cats come], excludes all of \(\phi \)’s non-identical alternatives, which in our case involve numbers higher than three. As a consequence, antecedent-worlds are such that three and no more than three cats come in them.

Four out of five informants have this intuition. Three out of these four also consider it a clearer answer than if yaoshi ‘if’ is used instead of zhiyao. A reviewer brings up the possibility that this might be because yaoshi can have a contrastive topic instead of a focus in its scope, while zhiyao cannot.

The configuration at hand is essentially the same as one that I assume for German minimal sufficiency conditionals in Wimmer (2021b). Panizza and Sudo (2020) credit Krifka (1991) for the view that only may pass on alternatives for even to work with. Bade and Sachs (2019) (discussing silent exhaustification under embedding) point out that under Rooth (1992)’s classical view of focus association, the lower operator is predicted to cause an intervention effect.

The involvement of shi ‘be’ may raise the suspicion that (90) is actually a conditional with a ‘clefted’ antecedent, with a paraphrase like as long as it’s tea, Old Wang drinks it. The viability of such a reductionist analysis has to be left open here.

Two additional speakers suggest to add [semantically harmless] material to either (90) or the necessity-denying continuation in (91-b), but see no contradiction between them either.

The focus predicate’s genericity ensures supersethood either way. The reason for envoking an at least interpretation here is that genericity itself does not seem to ensure lowness: if the other, more specific alternative were the next best tea available, the generic predicate tea could not plausibly be construed as scalarly lower than that alternative, which shows that tea value necessarily factors into the way the scale is construed. A more explicit account might include a silent at least operator, cf. Crnič (2011), Alonso-Ovalle and Hirsch (2018).

References

Alonso-Ovalle, Luis, and Aron Hirsch. 2018. Keep ‘only’ strong. Proceedings of SALT 28: 251–270.

Bade, Nadine. 2016. Obligatory presupposition triggers in discourse. Empirical foundations of the theories Maximize Presupposition and Obligatory Implicatures. Ph.D. Thesis. Universität Tübingen.

Bade, Nadine, and Konstantin Sachs. 2019. EXH passes on alternatives: A comment on Fox and Spector (2018). Natural Language Semantics 27: 19–45.

Beck, Sigrid. 2019. Readings of scalar particles: Noch/still. Linguistics and Philosophy 43: 1–67.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen. 1994. Wh-words as polarity items. Chinese Languages and Linguistics II: 614–640.

Coppock, Elizabeth, and David Beaver. 2014. Principles of the exclusive muddle. Journal of Semantics 31: 371–432.

Crnič, Luka. 2011. Getting even. Ph.D. Thesis. MIT.

Crnič, Luka. 2012. Focus particles and embedded exhaustification. Journal of Semantics 30: 533–558.

von Fintel, Kai. 1994. Restrictions on quantifier domains. Ph.D. Thesis. UMass Amherst.

von Fintel, Kai. 1997. Bare plurals, bare conditionals, and only. Journal of Semantics 14: 1–56.

von Fintel, Kai, and Sabine Iatridou. 2004. What to do if you want to go to Harlem: Notes on anankastic conditionals and related matters. Ms., MIT.

von Fintel, Kai, and Sabine Iatridou. 2007. Anatomy of a modal construction. Linguistic Inquiry 38: 445–483.

von Fintel, Kai, and Sabine Iatridou. 2008. How to say ought in foreign: The composition of weak necessity modals. Time and modality, 115–141, Springer

von Fintel, Kai. 2011a. Conditionals. Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning 2: 1515–1538.

von Fintel, Kai, and Irene Heim. 2011b. Lecture notes on intensional semantics. Cambridge: MIT.

Fox, Danny. 2007. Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics, 71–120. Springer.

Greenberg, Yael. 2019. Even and only: Arguing for parallels in scalarity and in constructing alternatives. In Proceedings of NELS 49. Edited by Maggie Baird, and Jonathan Pesetsky, 61–70.

Grosz, Patrick Georg. 2012. On the grammar of optative constructions. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

Guerzoni, Elena. 2003. Why even ask? On the pragmatics of questions and the semantics of answers. Ph.D. Thesis. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Heim, Irene. 1991. Artikel und Definitheit, 487–535. In Semantik: Ein internationales Handbuch der zeitgenössischen Forschung.

Heim, Irene. 1992. Presupposition projection and the semantics of attitude verbs. Journal of Semantics 9 (3): 183–221.

Herburger, Elena. 2015. Only if: If only we understood it. Sinn und Bedeutung (SuB)19: 304–321.

Herburger, Elena. 2016. Conditional perfection: The truth and the whole truth. SALT 25: 615–635.

Herburger, Elena. 2019. Bare conditionals in the red. Linguistics and Philosophy 42: 131–175.

Hole, Daniel. 2004. Focus and background marking in Mandarin Chinese: System and theory behind cai, jiu, dou and ye. London: Routledge.

Hole, Daniel. 2006. Mapping VPs to restrictors: Anti-diesing effects in Mandarin Chinese. Where semantics meets pragmatics, 337–380, Brill, Paderborn, Germany.

Hole, Daniel. 2017. A crosslinguistic syntax of scalar and non-scalar focus particle sentences: The view from Vietnamese and Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 26: 389–409.

Horn, Laurence R. 1969. A presuppositional analysis of only and even. In Proceedings of CLS 5: 98–107.

Horn, Laurence R. 1996. Exclusive company: Only and the dynamics of vertical inference. Journal of Semantics 13: 1–40.

Horn, Laurence R. 2000. From if to iff: Conditional perfection as pragmatic strengthening. Journal of Pragmatics 32 (3): 289–326.

Iatridou, Sabine. 2000. The grammatical ingredients of counterfactuality. Linguistic Inquiry 31: 231–270.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1986. Conditionals. In Proceedings of CLS 22.

Krifka, Manfred. 1991. A compositional semantics for multiple focus constructions. In Proceedings of SALT 1.

Krifka, Manfred. 2000. Alternatives for aspectual particles: Semantics of still and already. In Proceedings of the twenty-sixth annual meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 401–412.

Lai, Huei-Ling. 1999. Rejected expectations: the scalar particles cai and jiu in Mandarin Chinese. Linguistics 37: 625–661.

Lewis, David. 1973. Counterfactuals. Oxford: Blackwell.

Liu, Mingming. 2017a. Varieties of alternatives: Mandarin focus particles. Linguistics and Philosophy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10988-016-9199-y.

Liu, Mingming. 2017. Mandarin conditional conjunctions and only. Studies in Logic 10: 45–61.

McCawley, James. 1993. Everything that linguists have always wanted to know about logic* *but were ashamed to ask. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Milsark, Gary Lee. 1974. Existential sentences in English. Ph.D. Thesis. MIT.

Palmer, Frank Robert. 1986. Mood and modality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Panizza, Daniele, and Yasutada Sudo. 2020. Minimal sufficiency with covert even. Glossa 5: 1–25.

Partee, Barbara. 2002/1986. Noun phrase interpretation and type-shifting principles, 357–381. Chicago: Blackwell Publishing.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 75–116.

Rubinstein, Aynat. 2014. On necessity and comparison. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 95(4): 512–554.

Rubinstein, Aynat. 2017. Straddling the line between attitude verbs and necessity modals. In Modality across syntactic categories. Edited by Ana Arregui, María Luisa Rivero, and Andrés Salanova, 610–633. Oxford University Press.

Rullmann, Hotze. 1997. Even, polarity, and scope. Papers in Experimental and Theoretical Linguistics 4: 40–64.

Schulz, Katrin. 2014. Fake tense in conditional sentences: A modal approach. Natural Language Semantics 22: 117–144.

Stalnaker, Robert C. 1968. A theory of conditionals. In Ifs, 41–55. Springer.

Stalnaker, Robert C. 1980. A defense of conditional excluded middle. In Ifs, 87–104. Springer.

von Stechow, Arnim, Sveta Krasikova, and Doris Penka. 2006. Anankastic conditionals again. In A Festschrift for Kjell Johan Sæbø: In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the celebration of his 50th birthday, 151–171.

Sun, Yenan. 2021. A bipartite analysis of zhiyou ‘only’ in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 30: 1–37.

Tsai, Cheng-Yu Edwin. 2017. Preverbal number phrases in Mandarin and the scalar reasoning of jiu. In Proceedings of WCCFL 34: 554–561.

Vander Klok, Jozina, and Vera Hohaus. 2020. Weak necessity without weak possibility: The composition of modal strength distinctions in Javanese. Semantics and Pragmatics 13.

Wimmer, Alexander. 2021a. Flavors of scalar lowness. In Proceedings of IATL 2018–2019, Edited by Gabi Danon, 175–189.

Wimmer, Alexander. 2021b. Keeping only exclusive in conditional antecedents. Paper submitted to the Proceedings of CLS 57.

Xie, Zhiguo. 2022. Epistemic modality and comparison in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 31: 1–39.

Zhang, Linmin, and Jia Ling. 2017. Mandarin Chinese particle jiù: A current question restrictor. http://semanticsarchive.net/Archive/TlkNmU5N/ZhangLing_2017_ TEAL11.pdf. Slides presented at TEAL 11 [accessed 2018/03/04].

Acknowledgements

For valuable feedback, I am indebted to Giuliano Armenante, Sigrid Beck, Mingya Liu and to two anonymous JEAL reviewers, whose constructive comments have added a lot more depth to this paper—which would not exist in the first place without my endlessly patient consultants: Xuna Yu, Xiaozhu Zhou, and especially Xiaojie Su and Yiting Tian, who readily elicited judgments from several members of her family. Toshiko Oda kindly elicited some more. I am also grateful to Kate Pilson, Vali Tamm and the editors of JEAL. Of course, all remaining shortcomings are my own.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The more subtle data points included in this paper—especially those involving contextual felicity judgments—were checked with at least two native speakers of Mandarin per data point. When there was disagreement between two speakers, at least one more speaker was consulted.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Is yao weak or strong?