In November 1903, the residents of New York City received difficult news: Harriet Maxwell Converse, the well-known leader of a community of Native Americans in the city, had died. As many at the time knew well, her life was a fascinating one. She was an accomplished poet, a white adoptee of the Seneca-Iroquois Snipe Clan, counted as her best friend the Civil War hero and first Indigenous Commissioner of Indian Affairs Ely S. Parker, and was hand-selected by Haudenosaunee, also known as Iroquois, leadership and given honorary titles to help them in the fight to protect their national sovereignty.

Politically, then, Converse was seen as the Iroquois’ “chief publicist,” an adopted woman who spent the end of her adult life enjoying the support of leadership for her unflinching defense of their territorial sovereignty.Footnote 1 Professionally, however, Converse was very much the opposite. She was a salvage ethnographer, one of the many who contributed to the attempted cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples by participating in a predatory economic and academic system that turned the theft and surrender of Native American cultural objects from tribal control into a big business, all in the name of saving and studying the history of what they incorrectly saw as a “vanishing” race.Footnote 2 She was one of the many who made “‘research’ … one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary” all for the sole benefit of white entertainment and education.Footnote 3 But for Converse and her admirers, these were not mutually exclusive aspects of her Iroquoian life. She was colonial kin, a person whose predatory salvage informed her genuine desire to protect Indigenous sovereignty just as her official connections to Indian Country fueled her need to salvage.Footnote 4

Converse was thus a model leader for the Indian Colony of New York City, an embassy for Indigenous travelers and residents. From the founding of the Colony in 1885 to her death and the closing of the Colony in 1903, white New Yorkers read extensively in newspapers about the Colony, a space where:

Here in the city her home was their home. From far and near, Indians all over the country knew of her and adored her. The Sioux and those of other far Western tribes who came here with Buffalo Bill or with other shows invariably hunted her out and went to see her … To Mrs. Converse they constantly went with their troubles and for advice, invariably following religiously all her directions as to their course of action in given cases.Footnote 5

As this quotation suggests, journalists and others wrote in newspapers about the Colony and its governor and, in so doing, granted both a measure of publicity and fame that belied the tiny population of Indigenous Colonists relative to the rest of the city. It also reveals how Native American travelers, many from the northeast who came to the city for work in the entertainment industry and in the so-called Indian trade, met or spoke with Converse who then integrated them into the Colony’s expanding network boarding houses and resources. It did indeed look to the public as if “her home was their home.”

In that light, the ways that Converse and her Colony were portrayed in the press reveals the history of an unstudied community that was surprisingly well-known in its time. That history is overlooked for a few reasons. For historians of New York in this era, their attention is often—and deservedly—focused on the more familiar topics that follow significant changes in American life like European and Asian immigration; New York’s explosive economic growth in the Gilded Age; the social and political reforms underway that shaped city and nation; and the ways that New York City’s own society, culture, and economy influenced the rest of the country. Amid all that, the story of an adopted white woman overseeing a tiny community of Indians living in New York City is easy to miss, not least because Native Americans themselves are rarely understood as part of those broader histories. As historian Sherry Smith explains, Native Americans in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era “still seem to occupy a place at the margins of U.S. history.”Footnote 6

To help correct that historiographic gap, this article explores the hidden history of Converse and her Colony through contemporary newspapers. The Colony’s renown was due predominately to the press’s fascination with Converse herself. Her voice helped shape the public’s perception of the Colonists, her reputation and position as a wealthy white woman as well as an “authentic” adopted Seneca legitimized the Colony and its operations, her involvement in the predatory salvage trade and connections to museums influenced a slice of New York City’s cultural and museum intelligentsia, and her political connections and ability to control media narratives spread knowledge of the Colony throughout the region.

The existence of the Colony also pushes the periodization of urban Indian studies backward into the nineteenth century. Histories of the earliest urban Indian community in New York City typically focus on the famed Iroquois steelworkers, or “Skywalkers,” who migrated from upstate New York and Canada in the 1910s through the 1930s, “built the bones of this city,” and settled in a neighborhood known as “Little Kaugnawage” in Brooklyn.Footnote 7 Likewise, historians exploring urban Indian communities outside New York find them in the first decades of the twentieth century in cities like Seattle, Chicago, and even London.Footnote 8 An important part of identifying these communities is by their self-defined organization. In other words, the presence of Indigenous peoples in urban spaces does not qualify as an urban Indian community unless certain criteria are met. Like the immigrant and ethnic communities that grew in the decades prior, urban Indian communities had recognized leadership; were self-supported through some recognizable economic means; members maintained ties to their home communities (an idea that presumes, much like immigrant communities, that Indians could not ever be “from” these cities); and were otherwise recognized by the broader public as a distinct cultural entity and something other than the Anglo-American norm. As this article will reveal, Converse and the Colony not only checked all those boxes but thrived and faded away more than a decade earlier than those other urban Indian communities.

The Colony also inhabited a media space where the Colonists, led by their white, wealthy, and supposedly “authentic” adopted Seneca leader, were viewed as more socially acceptable than the other non-white, non-Protestant, or non-Anglo immigrant “colonies” in lower Manhattan.Footnote 9 While the press often wrote in stereotypical prose about the Native American actors, stagehands, and performers who came to the city to find work in the entertainment and myth-making machinery of Wild West shows and in the capital of the film industry in Fort Lee, New Jersey, many aspects of the Colonists’ lives revealed by that industry showed a community of people whose lives were often unremarkable, even familiar.Footnote 10 They arrived in New York City by train and ship, looked for work like millions of other immigrants and Americans, were doctors and students, struggled with poverty and enjoyed economic gains, some spoke English and others not at all, and they lived and died in ways that reflected how most people experienced day-to-day life in the city. The Colony was both a real and literary space where the printed stories of the lives of average Indigenous men and women clashed with Native American myths and stereotypes and, in so doing, revealed the dueling desires of white New Yorkers to see “authentic” Indians in their natural element but who also took comfort in the idea that these Indians were a prime example of the “civilizing” influence of American society on their Indigenous neighbors.

At the center of it all stood Converse, an adopted Seneca known to white New Yorkers as the “Great White Mother” and the only white woman ever given an honorary title of Iroquois League chief (a token title with no real governing authority).Footnote 11 New Yorkers’ interest in Converse was also linked to American’s shifting perceptions of what was an acceptable role for women in society and politics. Converse was but one of those many lily-white women who, by professing charitable intent, set out to assimilate non-Anglo-American immigrants and Indigenous peoples across the globe. Specifically, she joined a large cohort of predominately women settlement house reformers who intervened in the lives of non-white peoples and immigrants.Footnote 12 In that light, most of the newspaper coverage of the Colony focused on Converse and the women in her care because, in the public’s mind, the Colony was inseparable from, even unknowable without, its caring and knowledgeable governess who worked tirelessly to protect and “civilize” her charges.

Some aspects of Converse’s governorship of the Colony, however, broke those more predictable gendered assumptions. Elite men from local universities and museums frequented the ethnographic salon she operated out of her townhouse in Manhattan, which became a new and reputable intellectual arena in the city. Because of that scholarly acceptance, the salon became more than other elite houses-turned-galleries of the era. These, as scholars explain, showcased elite women’s participation in the new global economy by transforming the domestic space of their homes into a place of curated foreign encounter.Footnote 13 The salon was that, but it also mattered that Converse was one of the many women of the time who not only took on new public roles as caretakers and preservers of “Americana,” but that her home doubled as a reputable Indigenous museum as well as the seat of her salvage trading empire.Footnote 14 Adding to that reputation was the very fact that Iroquois leadership had given Converse the honorary title of a League chief. Regardless of the lack of any real authority the title bestowed or of her own non-committal views on women’s suffrage, her salon and title meant that she enjoyed a measure of popular political legitimacy, Indian “authenticity,” and a scholarly authority that undercut those other acceptable but still limited political and social roles set aside for women in American society.Footnote 15

In the end, the story of Converse and the Indian Colony reveals an unstudied aspect of New York City history from the perspective of a press that expected much from this tiny community and its governess. This article shows how the public’s interest in Converse, and by extension the Colonists, blurred the lines between stereotype and reality. It reveals how white New Yorkers sought to understand and co-opt the stories and images of the Indigenous peoples who formed their own communities in white urban spaces, often in defiance of that very pressure. Similarly, it invites historians to take a closer look at how newspaper sources can help tease out the lives of individuals otherwise invisible in the historical record and to highlight some of the paradoxical ways that contemporary publicity, however stereotyped and intentionally damaging, subtly pushed back against the erasure of Indigenous peoples from American society by elevating the lives and experiences of the living Colonists.

*****

Jacob Riis, one of the most influential and poignant commentators on immigrant communities in the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, knew that immigration was an important challenge the United States faced at the turn of the century and, as an example, he pointed to the rapidly expanding immigrant “colon[ies]” of New York City.Footnote 16 Like Riis, other journalists and writers who came to New York with a “taste for the exotic” found what they were looking for among the immigrant communities that claimed sections of the city and turned them, as historians explain, into “foreign territory.” These writers encountered people on the streets and in neighborhoods who spoke a myriad of different languages, commented on how the faces and dress of locals had visibly changed, and noticed that the neighborhoods only seemed to become ever more diverse and densely populated. Whenever journalists and writers spoke of these “colonies,” it was as if New York City itself had become a set piece in a foreign “travelogue.”Footnote 17

By the last decades of the nineteenth century, the New York reading public recognized on sight the “Negro,” “Italian,” “Syrian,” “Russian,” “Chinese,” “English,” “French,” “Greek,” and other “colonies” scattered across the industrial southeastern quarter of the island.Footnote 18 The Sun marveled at the “sixty-six languages” spoken in New York City, though they made the careful distinction that the presence of a language “did not” necessarily “imply a colony of its own” and that “many” of these language-speakers “were lumped into the ghetto.” The Irish, for example, a people that had once enjoyed their own “colony” but had since diffused throughout the poorer sections of New York City, no longer counted as a colony. True colonies were easy to spot because they were sometimes so ethnically uniform that “experts” professed to be able to “pick out tenements practically filled with tenants from a single town” of their home country.Footnote 19 Nearly fifty “foreign language” newspapers were published throughout the city, and many of these languages could even be heard in New York’s public school system.Footnote 20

The Indian Colony, while it could not claim a single city block in the densely populated Lower East Side as its own, was nevertheless regarded as one of those legitimate colonies. As a result, it became a known quantity to New Yorkers and to Indidgenous peoples nationwide. Most colonists were Haudenosaunee from upstate New York and Canada, who found a welcoming host in Harriet Maxwell Converse and—for better or worse—an audience among the city’s white reading public. Many of these Colonists came to a city swept up by the vast demographic changes caused by European and Asian immigration, and Native Americans similarly found themselves entangled in a media environment that catered to an Anglo-American audience both obsessed and repulsed by their encounters with “others” from around the world.Footnote 21

While Native Americans were likewise regarded as racial “others,” part of what fascinated New Yorkers about the Colonists was that newspapers generally talked about them as a people distinct from those other “others.” Converse was the primary architect of that image. Born in 1836 in Elmira, New York, she gained notoriety early in life as a poet and journalist and, by the 1880s, married Frank Converse, the “father” of contemporary banjo instruction. Her life changed, however, when she befriended a famous Native American and Civil War hero, Ely S. Parker. The two became fast friends, he brought her to Iroquois reservations upstate and in Canada, and in 1884 Converse was formally adopted into the Seneca Snipe Clan by his sister, Caroline Parker Mountpleasant. This made Converse, to the Parkers as well as to the outside world, kin. At the same time, her interest and participation in the predatory practice of salvage ethnography grew with time. From her adoption until she died, Converse was responsible for the removal of countless material culture objects from Iroquois control that were then sold to the highest bidder or donated to build museum ethnography collections. But to the Haudenosaunee, her political value in protecting Iroquois sovereignty outweighed the cultural damage she left in her wake. Because of her connections, resources, and ability to mobilize public opinion in the press, and after a few years working on behalf of the Seneca in court and in public to successfully defend Iroquois sovereignty from predatory private, state, and federal removal efforts, she was selected by the Iroquois leadership in 1891 to become a member of the Seneca nation. Later that year, she was given an informal honorary title as a Six Nations League chief, the highest honorary title an adopted woman ever achieved (but that held no real political influence among the Six Nations).Footnote 22

While Converse’s role in Haudenosaunee politics and salvage ethnography are not the focus of this article, they do help to shed light on her governorship of the Colony. That perfect storm of Converse’s adoption, political connections, and ethnographic influence meant that when she established herself as the ambassador of Native America to New York City, New Yorkers listened. Not only was she among the most famous adopted Native Americans in the country, she had help from another famous Native American, Ely Parker, who lent further credibility to this adopted Seneca. With Parker’s help until he passed away in 1895, Converse hosted an ethnographic salon of repute from her apartment, operated a network of boarding houses, supplied travel/financial/political resources to the many resident and visiting Colonists, and she did it all under the socially acceptable guise of an elite woman engaging in her own version of social charity. The Indian Colony thus captivated New Yorkers because it blurred the lines between nativism and immigration, “civilization” and “savagery,” and had the veneer of academic legitimacy since it was the seat of one of the most important regional centers of Native American salvage ethnography.Footnote 23

An important part of cultivating that kind of public credibility was Converse’s ability to position herself as the Iroquois’ guardian in terms that locals, particularly those concerned about immigration and the increasingly complex religious and ethnic makeup of the city, recognized. For example, Converse’s adoption and views on assimilation resonated with Rosa Sonneschein, the founder and editor of the influential The American Jewess magazine headquartered in Chicago and an early supporter of the progressive Jewish Women’s Congress, who published an article in 1895 on “The White Chief[’s]” remarkable Seneca life. In it, Sonneschein excerpted a letter from Converse in which she expressed admiration for “your race,” which had “preserved its identity through years of persecution and sorrow.” Converse described her own “adopted people” as “Like the Jews” in that they are “a persecuted race” who “need not be Christianized to become civilized.” To Converse, as with most social reformers of the era, the foundation of any “civilizing” effort was an education in which reformers would teach Native Americans to shed their old cultures and participate in the international economy and assimilate into white society. Like the solutions put forward by contemporary American Jewish intellectuals Alexandar Harkavy and Abraham Cahan who wrote about ways to bend the written and spoken Yiddish language to better “get along in English” with the ultimate goal of “eas[ing] everyday assimilation,” Converse also had faith that Indians should adopt aspects of the dominant culture in order to “‘keep sacred what they consider so; they have a right to do this, as well as other nations.’”Footnote 24

The language connecting Native Americans to the Jewish experience was immediately recognizable by many New Yorkers, immigration commentators and reformers, and the rapidly expanding Jewish population in the city.Footnote 25 By writing to Sonneschein and The American Jewess, Converse tapped into the familiar and ongoing public debates over immigration, social belonging, cultural acceptance, and the place of “others” in a changing American society. In doing so, she presented the Iroquois and Native Americans to the public as a people akin to what Jewish reformers and sympathetic Americans had been arguing for decades: a people whose society and culture was different, but not entirely incompatible, with Anglo-American lifeways.

That dualism resonated with Sonneschein and mirrored the understanding of many contemporary Jewish intellectuals, immigration reformers, and even Zionists who saw American Jews as having “evolved a distinctively Jewish way (or ways) of being American, of living as an aspiring and the equal member of the gentile-dominated world yet doing so in a manner recognized and accepted by Jew and non-Jew alike.” American Jews “experienced simultaneous separateness and doubleness” in their efforts to protect their language and cultural norms amidst constant and antagonistic pressure from a country and culture that deemed Anglo-American whiteness, the English language, and the Christian faith as the only acceptable traits of an “advanced” society.Footnote 26 Converse’s faith in the possibility, indeed the desirability, of Indigenous and white coexistence persisted even as nationwide efforts to destroy Native American languages and cultures were ongoing. The most infamous example of these were Indian Boarding Schools.Footnote 27 Yet Converse understood the Iroquois as “not so far behind the Christian as the latter is prone to believe,” and Sonneschein agreed. The editor of The American Jewess even brought Converse into conversation with Zionists directly when she suggested that the “permanen[t] … independence” of the Indians was a state of existence so “indispensable to their existence” that it reverberated with her own peoples’ experience (not to mention many other immigrant communities).Footnote 28 Both women agreed that a form of coexistence, whether Indian or Jewish, was compatible with American life.

Converse also extended her rhetoric on Haudenosaunee assimilation and protectionism north into Iroquois country itself. She was quick to defend the history and memory of an exceptional Iroquoian history, one closely bound to New Yorkers’ understanding of themselves as exceptional citizens of an exceptional Empire State.Footnote 29 For example, when defending the Senecas in 1895 against the groundless charge that they ate “cooked dog meat” at the annual Corn Dance, Converse borrowed from the stereotype of the “stoic” to prove that they were not “savages,” as many believed, but were even more civilized and philanthropic than local New Yorkers. The Haudenosaunee were “sober” and industrious, more “moral” than “the white people” who lived nearby, and were nearly immune to criminality as only “sixteen” had been charged with a crime, and even then only for minor offenses.Footnote 30 What was more, Converse explained that Haudenosaunee women generally kept beautiful and “tastefully furnished” homes and, like some of their men, lived a model industrious life. Converse’s Iroquois were a model of racial uplift, a perception that clashed with the incredibly popular stereotypes of “savage” Plains Indians perpetuated by Wild West shows.Footnote 31

Similarly, the Colonists were “civilized,” educated, and defied other Indian stereotypes. This included Colonists who were “bead and basket workers,” and “‘supes’ (or supernumerary actors) in Indian plays,” and “models for artists and illustrators.” These Colonists stood in stark contrast to their European immigrant neighbors and, in that contest, became the model of a “civilized” and assimilated people that immigrant communities would do well to emulate.Footnote 32 After all, the Colony was a model community of “clean” and industrious people. Regardless of the stereotype-perpetuating industries its residents worked in, the Colonists were not at all like their immigrant neighbors who were “dirty,” lived in crime-ridden communities, and were generally un-American aliens who literally covered the streets with trash.Footnote 33

Another reason why the Colony seemed a more civilized community was because of the reputation of Converse’s ethnographic salon. Open to Indian and non-Indian alike, the salon was a space where Converse exhibited her material culture collection. It tempted the city’s ethnographic and museum intelligentsia with its impressive ethnography collection and offered visitors an opportunity to meet Native Americans in person.Footnote 34 Observers noted the “many brilliant minds” from New York City’s universities and museums that “congregate[d]” in Converse’s “Indian sanctum.” They came to “listen to most interesting information from the charming and enthusiastic hostess,” peruse her collection, and chat with the Indigenous peoples who attended the meetings.Footnote 35 To white New Yorkers, Converse was the academic and social gatekeeper of one of New York City’s unique ethnic communities.

This “Indian sanctum” was also the seat of a salvage ethnography trading empire. Converse’s collection was built over decades and included sensitive and mundane pieces of Native American material culture, much of it from the Haudenosaunee. Wampum belts, masks, rattles, weapons, beads, artwork, recorded songs and dances, a lock of hair and portrait of the famed Seneca orator Red Jacket, and countless other objects turned her apartment into a veritable ethnographic sales floor. Converse built the collection to preserve the history of the “vanishing Indian,” but also to display, buy, sell, and trade. She sold 3,000 pieces and $6,000 “worth of wampum and Indian relics” to the New York State Museum alone, a number that does not include her sales and trades to World’s Fairs, the Smithsonian Institution, and other smaller museums and private collectors.Footnote 36

The salon was a place of education, salvage ethnography, and historic and cultural preservation, but it also functioned as a boarding house and therefore reflected the assimilationist goals of the settlement house movement. Pioneered by Jane Addams and Chicago’s Hull House and like institutions in England, the settlement houses were women-led places of social welfare where immigrants and the poor were taught “cultural uplift” in the vein of the Social Gospel by mostly wealthy and educated young people. These social reformers, writ large, sought to reform American society by spreading “elite culture to their plebian neighbors” throughout urban America in order to help society’s helpless.Footnote 37

These charity houses, like the Colony itself, were an important part of late nineteenth-century immigrant and working-class life. By 1890, they had become so popular that the annual New York Charities Directory listed hundreds of different organizations of their kind. Of relevance to Indian residents and visitors to the Colony, these directories included “a brief description of the purposes of all worthy charitable organizations,” which included “Class 3” or “special relief” charities that provided financial and legal assistance to many, including “Indians.”Footnote 38 Other references to Indigenous peoples ranged from the use of stereotypical images of Native American men—presumably wounded during the recent Indian Wars—to sell artificial limbs to descriptions of the various “Christian public sentiment[s]” of certain charities who professed to help Indigenous peoples, even convicts.Footnote 39 As these directories show, Native Americans were not an unexpected community in New York City but were a recognized part, albeit a small one, of its social and economic life.

Converse, even though she was a generation older than those who founded many contemporary charities and settlement houses, was known as a woman with similarly philanthropic instincts. She took into her home and supported through the Colony many Indian travelers to New York City, but she also extended that spirit elsewhere. As a “member of the Women’s Press Club” she was involved in their charity events. She even spoke as an official source grading the performance of the New York Evening World’s distribution of five hundred loaves of bread to “the hungry unemployed poor of the east side.”Footnote 40 And when asked as she often was about the Iroquois, she would speak of them in similarly philanthropic terms. In her defense of the annual Corn Dance, for example, she explained that despite suffering “the ‘pale faces at Salamanca’ [who] have succeeded in wresting from the Seneca the fairest of their land,” the Iroquois leveraged their collective resources to support the “four paupers” that lived in Iroquois country. This was one of many stories that proved “the charity of the Indian people themselves.”Footnote 41

The Colony was, in that sense, Converse’s greatest contribution to the popular and progressive social welfare movement. Alongside Ely Parker (until he passed away in 1895) who took a low-level clerkship at the New York City Police Department (NYPD) during retirement, Converse oversaw a sprawling organization known to newspapers and the public as the central hub of Indian activity in the city.Footnote 42 As the Daily People reported, the “Indian gravitates to Indian as surely as water finds its level,” so the Colony became the best place for white Americans to observe Native Americans at home, at work, and traveling not to “war” but “returning from an artist’s studio, a theatre, or a call on General Ely S. Parker or Mrs. Harriet Maxwell Converse.”Footnote 43 And in general, that was not a bad strategy. If an Indigenous person lived in or visited the city, they made time to see Converse and Parker. If they got lost or railroad and steamboat operators were stumped by the various Indigenous languages spoken by the Colonists, they were escorted by “friendly officers” to Parker’s office at NYPD headquarters on 300 Mulberry Street who then sent them to boarding houses and to Converse directly for further assistance.Footnote 44 If someone needed funds or help getting back home to their people, Converse would leverage the Colony’s resources to make it happen.

The capital of the Colony, like the salon, was Converse’s townhouse at either 450 West 20th Street or 155 West 46th Street.Footnote 45 The boarding houses of the Colony were scattered throughout neighborhoods now known as Tribeca, Soho, the West Village, and Midtown West. Until Parker’s death in 1895, his NYPD office served as the first point of contact for many Indigenous visitors to the city. These initial meetings were frequent enough that Jacob Riis, a friend of Parker’s, expressed his “sheer delight” at the chance to watch the “powwow that ensued” when Parker’s people from the Iroquois reservations and from Canada called on him at his office.Footnote 46 (See fig. 1.)

Fig. 1. Locations of Indian Colony sites in Manhattan. Details added by the author. Map: New York City Elevated Railroads, 1897. From the New York Public Library, Lionel Pincus & Princess Firyal Map Division, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/1d416880-f3b2-0130-ddc2-58d385a7b928 (accessed Nov. 2020).

As for the permanent residents of the Colony, newspapers reported that there were “half a hundred all told” permanent Native American residents living in New York City. They were praised for their work as students, doctors, and laborers, but their “civilized” occupations could not hide the fact that they were what was “left to the island of its earliest red-skinned sovereigns.” The Colonists who attracted the most attention, however, were the nonresidents who visited the city and utilized the Colony’s resources. Perhaps the first of these was Julia French, or “Do-de-oak-ton,” a young Mohawk woman who visited the city in January 1885 from the Iroquois territory of Kahnawake, Canada. French was part of an Indian acting troupe that stopped in the city on their way to “exhibit themselves in a Philadelphia dime museum” but, soon after they arrived, French “disappeared mysteriously” after a late night out on the town. One of her companions, knowing that Ely Parker worked nearby, came to his office for help. Parker issued a general release among the officers of the NYPD to locate French and bring her to the station, but it is unclear if she was ever found.Footnote 47

Over the next decade, the Colony expanded far beyond the salon and the walls of Parker’s NYPD office to become a network of boarding houses and people that utilized the resources and high-level connections of Converse and Parker. Starting with French and expanding to others who came to the city, Converse and Parker built a functional embassy for Indigenous residents and travelers to the city. In addition to Parker’s network of police informants, Converse’s own reputation as a salvage ethnographer and Seneca kin were vital to the operation of the Colony. She was widely known as an honorary League chief, an appointment that gave her a measure of publicity, legitimacy, and “authenticity” among white New Yorkers, but also attracted Indigenous travelers, particularly from Iroquois country. Along with her Haudenosaunee bona fides, her class and social connections also granted her important access to discounted train tickets for Native American travelers to and from New York City. These came primarily from her friend Joseph “Udo” Keppler, a fellow friend of the Iroquois, owner of Puck magazine, and representative of the New York West Shore & Buffalo Railway Company. Converse’s adoption and her honorary leadership title her the political gravitas to speak on behalf of Colonists to various federal Indian agents.Footnote 48

Converse established herself as the “governor” of the Colony, a role that mirrored what many white and Indigenous contemporaries expected of her as the Iroquois’ “chief publicist.”Footnote 49 Then in 1891, the same year she was made a member of the Seneca nation and an honorary League chief, newspapers began reporting on the ways she leveraged her newfound political status to help the Colonists. A young Mohawk woman named Annie Carr, or “Ta-ka-ni-wi-ta,” encountered Converse and the Colony after she was abandoned by her husband in New York City. After Carr’s husband stole the money she made from selling her “beadwork” and left her struggling for days in despondency on the street, she attempted to kill herself somewhere near the Battery. Local police officers intervened in time to save her life, brought her to a hospital to recover for a few days, then brought her to a police court where she was charged with the crime of “self murder.” During the trial, a court official contacted Converse, the “‘White Woman Chief,’” who was brought in to speak on the young woman’s behalf. Converse appealed Carr’s prison sentence by suggesting that she be sent back to her reservation and confined there for five years. The court complied, Carr was sent back home, and the two women maintained correspondence thereafter.Footnote 50

In May 1891, one Haggard Menicke, a Kahnawake St. Regis Mohawk, and her granddaughter were found by a local officer “sitting disconsolately on a trunk at the Grand Central Station evidently waiting to be called for.” They were in the city to sell beadwork made on the reservation, but somehow their connection to the city, Sarah A. Peirce, also a Mohawk from Kahnawake who lived near the Colony at 161 Varick Street, never got the message. The officer who found them, at a loss because they did not speak English, followed Parker’s standing advice on how to handle wayward Indians and brought them straight to police headquarters. After meeting Parker, Menicke and her granddaughter spent the night in Parker and a “Matron Travers” care. Converse and Peirce arrived the next day and took the women to a boarding house on 218 Spring Street.Footnote 51

The public knew Sarah Peirce as an “Indian Queen” of the Colony and a trusted ally of Converse’s. She lived in the city with her mother, an Indigenous woman who did not speak a word of English, so Peirce’s role in the Colony was as a translator. Eventually, she opened her apartment as another boarding house. Peirce was well-suited to hosting and helping Colonists because, like many others, she made a living “from the sale of her bead and fancy work” to “Indian-ware dealers of the city.” This reportedly comfortable existence did not last long, however. In 1892, Peirce became sick with “consumption” and then, in June that year, she was “run over by a Belt Line car in West Street near Canal Street.” She never recovered and was eventually declared “Insane” and committed to the asylum on Ward’s Island (now Roosevelt Island) in 1894. Converse, the “warmest champion” the “Indians have in the east,” found out about Peirce’s committal and relocated her to the Bloomingdale Insane Asylum where she was just a short train trip away in Morningside Heights. Peirce’s health failed before the transfer could be made, however, and she died shortly after Converse brought Peirce’s mother in to see her at Ward’s Island one last time. Converse arranged for her friend’s remains to be brought back to Kahnawake to be buried at St. John’s Chapel. Peirce’s mother, with help from Converse who spoke on her behalf to the Canadian Indian agent, secured funding from the agent to escort her daughter home.Footnote 52

As with Peirce and others, much of Converse’s Colony business involved leveraging her own influence to help the Colonists. In October 1894, a Louis Saylor and Eva Rea Jamison Jacobs, Two Canadian Mohaws of the Grand River Iroquois reservation in Canada, came to Converse for help in getting married in the city. Newspapers, as usual, followed the couple and marveled at how “civilized” their wedding was. “Though it was not preceded” by “burning teepees, bloodied tomahawks and forced marches through the wilderness,” the young couple enjoyed as “long a courtship as any wedding of the romantic Indian fiction” popular at the time, perhaps due in large part to the fact that they apparently “did not look at all like a [stereotypical] Indian.”Footnote 53

Behind this racially inspired dramatization of an otherwise joyous event were the far more relatable and real familial problems rooted in the reservation economy and church membership. Eva’s mother, unaware that the couple had eloped, had long resisted the idea of Eva marrying anyone who would “take her away from the reservation.” This was not at all surprising considering the Anglo-American assault on Indigenous land around the turn of the century in Canada and the United States, but it was also due to much more local concerns: Eva was an important part of her mother’s business creating “Indian costumes” to sell to “theatrical people.” The mother worried that if her daughter were married off, her husband would cut into the family’s self-sufficiency. To make matters more difficult, Eva’s mother did not approve of the fact that her daughter, a Catholic, was planning to marry an Episcopalian. Nevertheless, the couple eloped to New York City to seek out “the white chief of the Senecas’” for help. Louis, who also grew up on the Grand River Reservation, claimed to know Converse when he was younger, a very real possibility considering that Converse visited the New York and Canadian Iroquois reservations annually. And help she did. Converse organized their wedding at St. Chrysostom’s Episcopal Church on Seventh Avenue and 39th Street, secured flowers and lighting, put together and attended the wedding ceremony and reception, and saw “the couple off on their wedding trip.” After the ceremony, Converse settled in to “await the arrival of Eva’s mother” who was on a trip to St. Louis and girded herself for “the delicate diplomacy of getting Louis into good standing with his church again.”Footnote 54

The Colony’s business also took Converse out of New York City. In November of 1897, Converse intervened in the arrest of Willie Bonda, a nineteen-year-old Seneca “side-show Indian” who either played or was nicknamed “Deerfoot,” the nickname of the legendary mid-nineteenth-century Seneca long-distance runner “Hot-tyo-so-do-no” (He Peeks in the Door), or Lewis Bennet. Bonda, who reporters called an “Oklahoma Indian” even though he was Seneca, was arrested in Newark, New Jersey, “after a lively chase” one morning. The night before, the young man “got full of strong water and went home with James Tanner, [a white] saloonkeeper of Springfield Avenue.” The next day while Tanner was still asleep, Bonda reportedly absconded with two of his host’s silver watches. Tanner called the police and the officers pursued Bonda. Bonda ran because, as the papers put it, “it was quite natural for an Indian to run if anybody was pursuing him.” But when caught, the young Seneca claimed that “he was so drunk that he did not know what he was doing.” Converse learned about Bonda’s arrest, and the morning after “the only white woman chief of the Six Nations” appeared at the police station in Newark to speak on Bonda’s behalf and remind the officers that Tanner himself “was liable to a fine of $500 for selling liquor to an Indian.” After a few hours, the “19 year old youth” was “discharged with a reprimand” and returned to New York City where, presumably, Converse either reconnected him with his acting troupe or gave him a place to stay in the Colony.Footnote 55

As Bonda’s experiences show, New York City—and by extension the Colony—attracted large numbers of actors and costume makers who made a living performing their “Indian-ness” for American audiences. These actors, dancers, athletes, and other performers were mostly involved in traveling Wild West-type shows that came to New York. The shows, even the Indigenous peoples’ very presence in an urban space, satisfied the city’s vast appetite for exotic entertainment. It also fueled the growth of the capital of the Gilded Age film industry across the river in Fort Lee, New Jersey.Footnote 56 That interest spread far outside the entertainment industry, as well. While off the clock, Indigenous actors, artisans, and performers were sought out by museum and university ethnographers who saw these people as models—sometimes literally—of Native American racial purity.

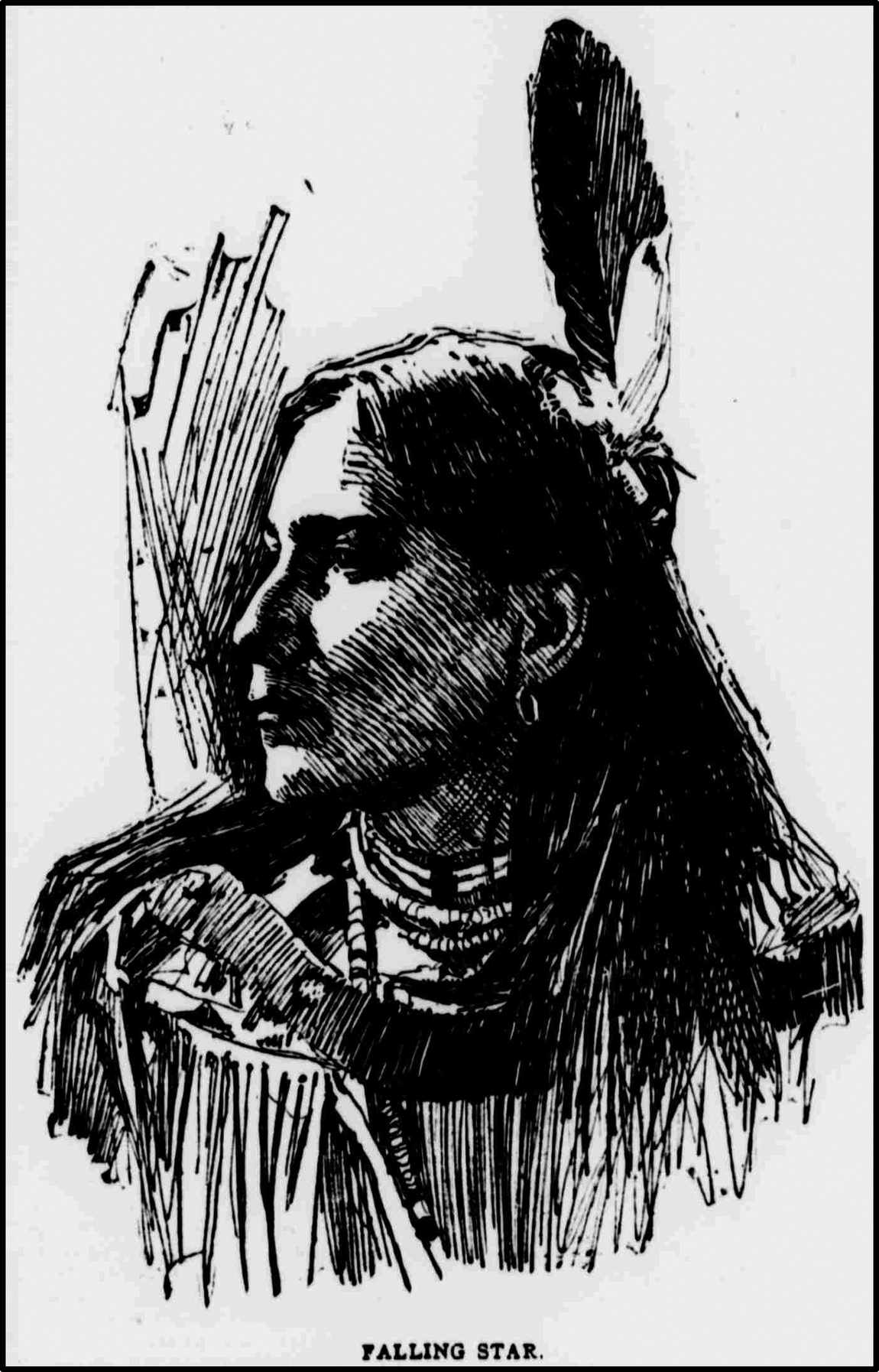

One of the more famous of these was an Abenaki woman named Annie Dennis Fuller, or “Falling Star.”Footnote 57 Fuller was swept into the orbit of the Colony because, like many others, when she arrived in the city she called on Converse first. The forty-year-old Abenaki woman arrived unannounced at Converse’s doorstep one day seeking advice about the best places in the city to trade her handwoven baskets, and she asked for help purchasing train tickets back home to Lake Luzerne, New York. Fuller was surprised, however, when Converse “paid no attention to the baskets” and instead offered her an entirely different proposal. When Fuller arrived, Converse used her “trained [salvage ethnographer’s] eye” to look past the drab woman “dressed in the garments of civilization, her swarthy face concealed by a veil” to find a beautiful Abenaki physical specimen, “a fine type of her race.” After that inspection, Converse, a woman ever on the lookout for ways to help Colonists and to feed her salvage ethnography, knew that Fuller would attract the attention of artists and ethnographers who “would make pictures of her and pay her for merely sitting still by the hour.” Fuller would prove to be a mild-mannered person uncomfortable with what the art and museum world asked of her, but Converse nevertheless convinced her to “place herself in the hands of her would-be fairy godmother.”Footnote 58 (See fig. 2.)

Fig. 2. Annie Dennis Fuller, or “Falling Star.” Sun (New York), January 25, 1903.

Fuller did exactly that. Over the next few years, she “Found a Fortune in Her Face.” Converse’s extensive connections and social influence put the Abenaki woman’s career as a model on the fast track. Within weeks, Fuller was invited to sit for the Chase School, the Metropolitan School of Fine Arts, the Pratt Institute, the Cooper Union School, several independent artists, and the Art Students League of New York. The artists were immediately drawn to Fuller. They marveled at how “fine!” she was, at “What eyes!” she had, and “What grace!” she comported herself with. Artists and journalists let their imaginations soar when they looked at Fuller and claimed to feel the spirit of the “mountains” and “forests.” She was not only a perfect and elegant physical specimen of her race and gender, but equally a “wild” Indian who was a renowned sharpshooter, an expert in “wood lore,” and a seasonal camp guide in the Adirondacks.Footnote 59

As a model, however, her “wild” beauty was never far removed from Euro-American’s standards of femininity. In Fuller’s case, that distance was quite literally short. Printed on the other side of the fold of a lengthy biography of Fuller in the Sun was an advice column written by a “beauty expert in Paris” who championed the feminine social art of the “Coquettish Turn of the Head.” This pose reflected how many artists portrayed Fuller and the surviving portraits of her printed in newspapers. The beauty expert explained to her readers that the art of “the Neck in Repose” and other “adorably noble and dignified” ways of leveraging the “poise of the head” would help both “really pretty and attractive” women as well as those for whom “fate has … carelessly … daubed on her features or modeled her form.” The article even professed to help those women who simply “lacked the art and intelligence to play up their best points and make the most of themselves.” Fuller’s rising fame was bound to that standard. The reason Converse and others saw her as a fine example of her “race” was because she embodied the public’s desire for that mixture of physical beauty and coy feminine modesty, while at the same time satisfying their obsession with seeing “wild” Indians in their own element. Fuller, much like the internationally famed Annie Oakley, could be both a delicate feminine domestic icon and a rugged Abenaki frontierswoman.Footnote 60

Fuller was also the model of a stereotypical “vanished” Indian. The same artists who marveled at her beauty also noted the “sad expression” on her face, one that made her “look as if she were sorrowing for her people and all that sort of thing.” But Fuller’s sadness, as Converse herself was quick to correct, was not born from a stereotypical lament for her “vanished” people but because she suffered from immense personal loss. Over her forty years of life, Fuller had lost her brother, father, and husband (perhaps shortly after their marriage) to disease and murder, and then “her only child” more recently. This left only Fuller and her “invalid mother” alive.Footnote 61 This is one of the few areas where Fuller’s story was not bound to stereotype but was universally recognizable to her white audience.

Yet despite Converse’s momentary defense of Fuller’s humanity against the “vanished Indian” stereotype, the elder woman was still a predatory salvage ethnographer. When Fuller was not busy meeting with artists all over the city, Converse introduced her to her friends Franz Boas and Caspar Mayer of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH).Footnote 62 Boas, the renowned Columbia University and AMNH ethnographer, member of Converse’s salon, and beneficiary of her donations to the museum; and Mayer, an artist and photographer from Albany who worked with Boas, also saw Fuller as the perfect physical manifestation of Indian womanhood. Even though Fuller was reluctant to “show her arms and shoulders” which reporters assumed was out of Indian modesty, Boas and Mayer studied her and took photographs of her face, her body in “Indian costume,” and made plaster casts of her hands and feet. Among the drawings and plaster casts, Mayer also created a life cast of Fuller’s face that remains in the museum’s collection but is in poor condition.Footnote 63 Fuller’s ethnographic appeal extended beyond the AMNH when another sculptor used her as the model for a statue of an Indian woman in “characteristic costume” that stood “in front of the Thomas Orphan Asylum on the Cattaraugus reservation.”Footnote 64

Fuller’s brief career as a model reveals the connections, influence, and—in the case of becoming an ethnographic object—intellectual interests of Converse and how these influenced the management of the Colony. The elder Seneca introduced Fuller to the many artists and organizations that entertained her, found her “$1.00-a-week” housing somewhere in the Colony on Sixth Avenue, and accompanied her on the many visits she made to the AMNH when Boas and Mayer studied her. In addition, Converse not only traveled with her to an outdoorsman camp in “Adirondack country” where Fuller would sell her baskets, but she also convinced the younger woman to create her own business cards for whenever she appeared in public or at art studios. Converse was around often enough at these events that Fuller was supposedly seen “secretly clinging to a corner of Mrs. Converse’s raiment now and then, lest the good fairy vanish away altogether.” Fuller was also described as being gifted in the healing arts, as well as an innovative designer who impressed Converse’s elite female friends with a fascinating “curtain” that she made for Converse “made like those of Japan, but composed of dried kernels of corn as well as beads.” Her celebrity grew to the point that, at an 1897 reception at Carnegie Hall for the Metropolitan School of Fine Arts, she was even “more important [an] attraction than” Mayor William Lafayette Strong. This was telling to those who read about the reception because even though the Colony made Indians a common-enough sight in the city, it was still quite a thing to see “a Mayor drinking tea” with “a full-blooded Indian woman pouring it.” In 1902, five years after that meeting, Fuller’s career came to end. She was severely injured in “a railroad accident” where “her usefulness as an artist’s model was at an end” and was left “unable to use her hands.” After the accident, Fuller parted ways with Converse and returned home to Luzerne. She was buried there in an unmarked grave in 1903.Footnote 65

While Fuller’s example provides an insight into the many ways the Colony operated to take care of and support its residents, the true extent of its reputation in Indian Country is most visible after Converse passed away “of apoplexy” in November 1903. Surrounded by a salvaged collection “crowded with arrow heads, war bonnets, feathers, snow shoes, blankets, and bead work” among other objects, the governor of the Colony died amidst the material culture of Indian Country that she spent the last two decades of her life collecting and trading.Footnote 66 Arthur C. Parker, her young Seneca protégé, first biographer, and Ely’s nephew, waxed poetic about the late Converse’s reputation in Iroquois country and throughout Native America. Respect for her “was born not only of gratitude for her constant efforts on their behalf, but from a feeling that she was actually one of them.” She looked out for the Colonists and was beloved because she personally intervened on their behalf with “small acts of kindness,” like with the unnamed “Sioux Indian” who was knocked from his horse and killed (presumably in or around New York City). The young man’s body, rather than being returned home as was proper, was seized by scientists who wanted to use it to study Indian physiology. Parker explained that Converse, knowing that “Indians have a great horror of mutilation after death … stood between them and the subject like a rock” and managed to convince the scientists to release the remains. She even oversaw the body’s shipment back to the Sioux reservation.Footnote 67

In keeping with that memory of Converse’s charity toward Indian people, Parker and Joseph Keppler expected her funeral service to attract many Indigenous visitors and well-wishers. They were not disappointed. The service was held at a local establishment, “Merritt’s undertaking establishment [at] Nineteenth street and Eight Avenue,” on November 22, 1903, and followed Iroquois customs. It was officiated by “Chief Cornplanter of the Senecas, who lives on the Cattaraugus Reservation.” Keppler, an adopted Seneca like Converse and the only other high-profile adopted Iroquois in the city, took the initiative and notified “twelve of the leading men of the Six Nations” of her death. Confident in Converse’s broad appeal, Keppler then told reporters that he had “no doubt” that other Native Americans from across the country would attend the funeral.Footnote 68

He was right. In attendance were at least seventy-five Native Americas from across the continent who mourned alongside Converse’s white friends, family, and associates. This number included Arthur Parker; “other Indians who lived in the neighborhood”; a “Great Medicine Man of the Long Island Indians” (presumably the Shinnecock); some members of the Sioux nations; a “Chief Dark Cloud” perhaps of the Abenaki of Montreal (Fuller’s kin); unnamed Indians from “Buffalo, Akron and Syracuse,” members of the “Hurons, Abenakis … and Algonquins”; and high-profile Haudenosaunee leaders like “Chiefs Crow, Cornplanter, Longfeather, Lay, and Sachem Chauncy Abrams.” From even further away came a “Chief War Cloud” and a “brave named Carlo” from the “Aztec tribe of Mexico.” The latter had apparently known about Converse and her role in the Colony and among the Iroquois, and while he did not know her personally he praised the “‘Great White Mother’ … and all she had done for his race.” There were also fifty representatives from the Six Nations who attended the funeral ceremony. Joining these dignitaries was a large crowd of her local white New York City friends and well-wishers that included clergy, artists, New York Congressman William Sulzer, and ex-NYPD Captain James Price and the brutal police inspector Alexander S. Williams, the “Czar of the Tenderloin.”Footnote 69

Converse’s funeral, for many casual observers, also symbolized an Iroquoian political regime change. Chauncy Abrams, “the gray headed hereditary Sachem of the Senecas,” recognized Joseph Keppler as the new “inheritor” of Converse’s honorary appointment as a Six Nations League chief. Chief Cornplanter also had confidence in Keppler, saying he “will take up her work … He will have the same power … He will do good.” After the funeral, the gathered “fifty” or so “Iroquois from the Six Nations,” the men “dressed like the palefaces and the women like their white sisters,” returned to “Onondaga to take part in the grand council which is going on there.” The Iroquois, the last to see Converse before her remains were moved to Elmira where she was buried with her husband, ceremonially transferred Converse’s honorary title to Keppler and returned home to continue running the Six Nations.Footnote 70

Despite Keppler’s token nomination, Converse’s death marked the end of the Colony. It had lost its governor and its most visible celebrity, the NYPD had no one left to refer Indigenous Colonists to, Keppler never picked up the mantle of a settlement house organizer, Converse’s salon ceased operation once she died, and her salvaged collections were sold to the highest bidder.Footnote 71

*****

The history of Harriet Maxwell Converse and her Indian Colony intersects with several broader historical themes. The Colonists themselves were caught up in the shifting expectations of a white America that knew Indian Country mostly through Wild West stereotyping. Colonists therefore straddled the line between foreignness and familiarity. They participated in a creative economy that was a major part of the metro area’s entertainment industry and shaped international Indigenous stereotypes, but their day-to-day lives revealed to New Yorkers a relative civility compared to neighboring immigrant colonies. They, with the seemingly benign leadership of Converse, challenged America’s notion of what an acceptable “other” looked and acted like.

Converse herself intersected with varied aspects of American life and embodied what New Yorkers expected to see from a “civilized” Indian. She was a salvage ethnographer and adopted Seneca, two entangled identities that granted her an unassailable “authenticity.” Her professional obligation to buy and sell Indigenous history and culture may have suggested a breach in the male-dominated world of scholarly anthropology, but the fact that she operated this salvage empire within the domestic arena of her townhouse, a space that also existed within the acceptably gendered realm of settlement houses, recategorized her as one of a growing number of women who preserved and protected Americana but within clearly defined gendered boundaries.

In addition, her adoption and honorary titles may have existed in tension with that gendered domestic ideal, but they nevertheless granted her the public authority necessary to speak for the Haudenosaunee and the other Colonists. To white New Yorkers it did not matter, nor did they care to learn, that she had no real political authority among the Senecas. To them, she was the governor of the Colony and leader of the Haudenosaunee, the fabled Indigenous empire of New York, whose gender and progressive ideals softened the stereotypes placed on the very Colonists she governed. She created, in effect, the perception that the Colony was an acceptably safe, yet still “authentic,” Native American space in New York City.

In terms of the Colonists’ experiences, their presence in newspapers was mostly that of an ethnographic object not unlike the coverage of neighboring immigrant colonies. But this Colony was uniquely shaped by Converse’s presence in their lives. In particular, the overtly gendered newspaper coverage of the Colony reveals the ways that Converse shaped the public’s perception of the Colonists, particularly women. Yet even in that skewed coverage, elements of the Colonist’s day-to-day experiences were visible. Their migration to the city was not unique, yet they also reflected how expulsed Native Americans nationwide were forced out of their homelands by destructive federal and state Indian policies. Still, they were among those who maintained their history and culture and created new ones in white urban spaces. The Colonists, in sometimes subtle ways, shaped the perspectives of those who preyed on Indigenous need and community.

In the end, the story of Converse and her Colony invites historians to expand our periodization of Urban Indian Studies into the late nineteenth century. When we take a closer look at communities like this, even if only through the lens of its white governors, we may find others that were surprisingly well-known despite their size and benefited from an organizational coherence that mirrored the planned Indigenous communities of the twentieth century. As the Colony shows, these spaces help illuminate the histories of non-white peoples nationwide who found themselves defending their culture and history against forces that wanted to see them “vanish” entirely.