Abstract

A major element of college sports governance is the enforcement of “amateurism”, that is, no pay beyond the grant-in-aid. Enforcement is a joint venture by university administrators through their National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) that preserves this interesting definition of amateurism and the wealth transfer it creates from athletes to those same administrators. Enforcement criticism abounds, aimed at the NCAA without any model of that process or incorporation of the motivations for enforcement. Three criticisms amenable to economic analysis are evaluated, that the level of enforcement is too low, is passive rather than active, and biased against lower-revenue programs. Basic economic modeling provides testable implications regarding these criticisms, rather than finger-pointing at the NCAA, hopefully adding to meaningful reform efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

“Amateurism” is in quotation marks here at this first instance because (discussed at length later) essentially it is whatever university administrators, acting through their NCAA, say it is. For example, see the Division I Manual (2020) at https://www.ncaapublications.com/productdownloads/D121.pdf.

Systemic oversight failure involving, say, Title IX participation violations, inappropriate sexual behavior under Title IX, or outright sexual predation violating state and local law are beyond the scope of this paper.

On the academic side, see Funk (1991), James (1993), Gerdy (1997), Zimbalist (1999), and Gurney et al. (2017). In the lay press, see Byers (1995). An informative cross-section of the legion of popular accounts includes Miller (2012), Solomon (2014), and Forde (2020). Others criticize exclusively due process and fairness that are not the point of this paper.

Miller (2012) went so far as to suggest that the NCAA needs to outsource enforcement to a law firm, consulting firm, or investigative agency.

The IAAUS became the NCAA at the fifth meeting in 1910 (Library of Congress, undated).

They reviewed the literature on greater giving by alumni and other boosters to the general university fund, a larger and better pool of student applicant, favorable general budget treatment by legislators, better faculty and administrators, value added to those athletes that would not be at the university without athletics, whatever Title IX compliance UAs have achieved through athletics.

Koch (1971, 1973) first identified the NCAA as an input cartel that reduced athlete compensation relative to a market outcome. That logic became so well-established that Fleisher, Goff & Tollison (1992) titled their analysis a “study in cartel behavior”. Fort and Quirk (1999) detailed the place of the input cartel in the entire “college football industry.” Even the NCAA’s own arguments in favor of amateurism rest on the impact on other sports if the subsidy is reduced. Rather than reprise references to the vast work on amateurism, the reader again is referred to the bibliographies in Fort (2015, 2016, 2018a).

This is purposefully vague, avoiding terms like “competitively determined”, since the point of the paper is not to engender a long discussion of possible processes to pay athletes closer to their contribution to the value in the athletic department and/or across the university.

It is unlikely that \(\alpha =1\) so that athletes receive literally zero compensation. Some level of compensation is needed to cover athlete opportunity costs outside of college sports. However, some athletes would find it worth their own investment into the returns to college sports. And the lower divisions see plenty of athletes pay their own way entirely. These cases would make college athletes much more like minor league baseball players, forced by market power circumstances to invest future earnings, or pay for the joy of participation.

In a more general model of the distribution of athlete talent across a college conference, with multiple sports outputs, Fort (2018a) shows the explicit conditions under which “college sports” outcomes are “invariant” with respect to the absence or presence of the amateur requirement.

The seven were Boston College, The Citadel, Maryland, Villanova, Virginia, Virginia Tech, and the Virginia Military Institute.

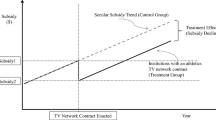

In the next season, 1952, UAs limited broadcasts to one national game and administered the selection and sale of rights through their NCAA. This stood until the famous case, NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma, 1984. Byers (1995) is informative on the original formation of NCAA enforcement.

The autonomy schools, also called the “Power 5”, include members of the Atlantic Coast Conference, Big 12 Conference, Big Ten Conference, Pacific-12 Conference, and Southeastern Conference, plus independent football colleges Army, Brigham Young, Connecticut, Liberty, Massachusetts, New Mexico State, and Notre Dame. Notre Dame football joined the Atlantic Coast Conference, just for 2021, and then returned to independent status after that.

Stern (1979, 1981) emphasized that the enforcement task requires oversight mechanisms for both detection and punishment. Noll (1991, p. 198) surmised that the incentives to cheat, and the resulting need for detection, grew over time with the ever-growing money incentives facing institutions and individual coaches.

The caution in footnote 2 bears repeating. This paper is not about systemic oversight failures resulting in illegal, criminal scandal.

DeSchriver and Stotlar (1996) estimate the size of the incentive to cheat based on March Madness earnings. Otto (2005) examines the impact of the size of penalties. Humphreys and Ruseski (2009) add a dynamic model of infraction choice. Fizel and Brown (2014) analyze a broader set of determinants, also identifying enforcement regimes, empirically. Harris (2016) devises a supply and demand for violations model and finds empirical support that penalties and detection probabilities matter as the model predicts.

The NCAA does not administer the FBS championship. It is run separately by a coalition of Football Bowl Subdivision conference commissioners, media firms, and bowl organizers through the College Football Playoff organization.

The history of COIP/SVPC is in NCAA (2015) and: http://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/media-center/press-releases/ncaa-announces-latest-division-i-certification-decision. The current SVPC details are at: http://www.ncaa.org/governance/committees/division-i-committee-institutional-performance.

The last certification granted under the program was in 2014. See https://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/media-center/press-releases/ncaa-announces-latest-division-i-certification-decision.

These reports also are the source of the annual NCAA Finances of Intercollegiate Athletics reports found at https://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/research/finances-intercollegiate-athletics). Reports to OPE at https://ope.ed.gov/athletics/#/are done by individual colleges, not the NCAA, based on the same data.

Stern (1981, p. 16) states of the NCAA, “Common surveillance techniques rely upon written reporting requirements, inspections, and charges brought by interested parties.” Fleisher et al. (1988) note that part of enforcement is direct monitoring of members, but they are not specific and their writing pre-dates COIP. Fleisher, Goff & Tollison (1992) add the idea of alarms in a proposed framework to empirically investigate enforcement. Interesting anecdotes of ADs reporting other ADs, and even coaches reporting other coaches, are in Byers (1995, Chap. 11).

Some might argue that there may be an incentive compatibility issue between enforcers and UAs. It is well-known that slack allows shirking as one explanation for observed outcomes. But the preservation of the transfer gives both UAs and critics a common goal in the face of shirking, namely, reducing it to its efficient level, given the costs of oversight.

Apologies for the recycling of P, the probability of detection in expression (4), and A, the unrestricted pay for athletes in expressions (1) through (3).

The complete history of violations is available at the NCAA’s Legislative Services Database (LSDBi), https://web3.ncaa.org/lsdbi/search/miCaseView?id=154. To this reader, these allegations all appear to be brought to the attention of the COI by athletes, other coaches, other ADs, or through those three via boosters and/or the press. In addition, Winfree and McCluskey (2008) find empirical evidence that self-reporting/punishment reduces eventual NCAA sanctions.

The quote has appeared many times through the years. This version is from Dufresne (2015).

Prior to the advent of the COI, Stern (1981) showed that stronger programs were more likely to be detected and penalized than weaker programs over the first 20 years of NCAA enforcement (1952–1972). Neither Fleisher, Schugart, Tollison & Goff (1988) nor Fleisher, Goff & Tollison (1992) found any bias against smaller-revenue programs. Otto (2005, p. 5) finds that the number of investigations, the infraction rate, penalty rates, and severity rates were all higher for higher-revenue programs.

Once again, apologies for recycling notation from before where L is the loss if cheating is detected in expression (4).

Joskow (1974) originally employed a similar diagram of the tradeoff between price and profit, with iso-values for electricity regulators having to do with the relative power of consumers and producers in the regulatory process.

References

Baumer A, Padilla D (1994) Big-time college sports: Management and economic issues. J Sport Social Issues 18:123–143

Byers W, Hammer C (1995) Unsportsmanlike conduct: Exploiting college athletes. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press

DeSchriver TD, Stotlar DK (1996) An economic analysis of cartel behavior within the NCAA. J Sport Manage 10:388–400

Dufresne C (2015) Jerry Tarkanian always liked a good fight, as NCAA learned the hard way. LATimes.com, Feb. 11. Last viewed online May 24, 2017 at http://www.latimes.com/sports/la-sp-tarkanian-appreciation-20150212-story.html

Fizel J, Brown CA (2014) Assessing the determinants of NCAA football violations. Atl Economic J 42:277–290

Fleisher AA, Shugart WF, Tollison RD, Goff BL (1988) Crime or punishment? Enforcement of the NCAA football cartel. J Economic Behav Organ 10:433–451

Fleisher AA, Goff BL, Tollison RD (1992) The National Collegiate Athletic Association: A study in cartel behavior. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL

Forde P (2020) SEC Commissioner warns NCAA it’s headed toward “crisis of confidence” over infractions case delays.Sports Illustrated, December 10. Last viewed June 8, 2021, at: https://www.si.com/college/2020/12/10/ncaa-basketball-investigations-greg-sankey-letter

Fort R (2015) College sports spending decisions and the academic mission. In: Comeaux E (ed) Introduction to intercollegiate athletics. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, pp 135–146

Fort R (2016) Collegiate athletic spending: Principals and agents v. arms race. J Amateur Sport 2:119–140

Fort R (2018a) Modeling competitive imbalance and self-regulation in college sports. Rev Ind Organ 52:231–251

Fort R (2018b) Sports economics, V1.0. Rodney Fort (Apple Books or Kindle), Ann Arbor, MI

Fort R, Quirk J (1999) The college football industry. In: Fizel J, Gustafson E, Hadley L (eds) Sports economics: Current research. Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT, pp 11–26

Fort R, Winfree J (2013) 15 sports myths and why they are wrong. Stanford University Press, Stanford, CA

Funk GD (1991) Major violation: The unbalanced priorities in athletics and academics. Leisure Press, Champaign, IL

Gerdy JR (1997) The successful college athletic program. The Oryx, Phoenix, AZ

Goff B (2000) Effects of university athletics on the university: A review and extension of empirical assessment. J Sport Manage 14:85–104

Grimes PW, Chressanthis GA (1994) Alumni contributions to academics: The role of intercollegiate sports and NCAA sanctions. Am J Econ Sociol 53:27–40

Gurney G, Lopiano D, Zimbalist A (2017) Unwinding madness: What went wrong with college sports—And how to fix it. Brookings Institution, Washington, D.C.

Harris JS (2016) The demand for student-athlete labor and the supply of violations in the NCAA. Marquette Sports Law Review 26:411–432

Hopenhayn H, Lohmann S (1996) Fire-alarm signals and the political oversight of regulatory agencies. J Law Econ Organ 12:196–213

Humphreys BR, Ruseski JE (2009) Monitoring cartel behavior and stability: Evidence from NCAA football. South Econ J 75:720–735

Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States (1906) Manual. Last viewed June 14, 2021, at: https://drive.google.com/drive/u/1/folders/16AGkNg4m0QVbA11pszR8bW7sFgpmCMQn

James KE (1993) College sports and NCAA enforcement procedures: Does the NCAA play fairly? National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Miller. Calif Western Law Rev 29:429–469

Johnson K (1998) Assistant coaches win N.C.A.A. suit; $66 million award, vol 1. New York Times, Section A

Joskow PL (1974) Inflation and environmental concern: Structural change in the process of public utility price regulation. J Law Econ 17:291–327

Koch JV (1971) The economics of “big time” intercollegiate athletics. Soc Sci Q 52:248–260

Koch JV (1973) A troubled cartel: The NCAA. Law Contemp Probl 38:135–150

Library of Congress. (Undated). NCAA and the movement to reform college football: Topics in Chronicling America. Last viewed June 10 (2021) at: https://guides.loc.gov/chronicling-america-ncaa-college-football-reform

Lupia A, McCubbins M (1994) Learning from oversight: Fire alarms and police patrols reconstructed. J Law Econ Organ 10:96–125

McCubbins M, Schwartz T (1984) Congressional oversight overlooked: Police patrols versus fire alarms. Am J Polit Sci 28:165–179

Miller GJ (2005) The political evolution of principal-agent models. Annu Rev Polit Sci 8:203–225

Miller SA (2012) The NCAA needs to let someone else enforce its rules. The Atlantic, October 23. Last viewed online June 8, 2021, at: https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/10/the-ncaa-needs-to-let-someone-else-enforce-its-rules/264012/

National Collegiate Athletic Association (1975) Proceedings of the 2nd special convention of the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Chicago, IL: Palmer House, August 14–15. Last viewed June 14, 2021, at: https://drive.google.com/drive/u/1/folders/16AGkNg4m0QVbA11pszR8bW7sFgpmCMQn

National Collegiate Athletic Association (2015) Handbook 2015-16 Reclassifying Institutions. NCAA, Indianapolis, IN

Noll RG (1991) The economics of intercollegiate sport. In: Andre J, James DN (eds) Rethinking college athletics. Temple University Press, Philadelphia, PA

Otto KA (2005) Major violations and NCAA “powerhouse” football programs: What are the odds of being charged? J Legal Aspects Sport 15:39–57

Smith DR (2015) It pays to bend the rules: The consequences of NCAA athletic sanctions. Sociol Perspect 58:97–119

Solomon J (2014) All quiet on the violations front… Is NCAA enforcement dead? CBSSports.com, May 13. Last viewed online May 24, 2017 at http://www.cbssports.com/college-football/news/all-quiet-on-the-violations-front-is-ncaa-enforcement-dead

Stern RN (1979) The development of an interorganizational control network: The case of intercollegiate athletics. Adm Sci Q 24:242–266

Stern RN (1981) Competitive influences on the interorganizational regulation of college athletics. Adm Sci Q 26:15–32

Winfree JA, McCluskey JJ (2008) Incentives for post-apprehension self-punishment: University self-sanctions for NCAA infractions. Int J Sport Finance 3:196–209

Zimbalist A (1999) Unpaid professionals. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Fort, R. College sports governance: “Amateurism” enforcement in big time college sports. Econ Gov 23, 303–322 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-022-00279-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10101-022-00279-w