Abstract

The purpose of this paper is twofold. First, it investigates the formation of Mandarin embedded short-answer sentences. Given the fact that this type of sentence shares many syntactic properties with Mandarin pseudo-sluicing constructions, I propose that they are not derived via movement and ellipsis; instead, they consist of a base-generated empty category, shi, and the short-answer phrase. Although Mandarin embedded short-answer sentences are structurally similar to pseudo-sluicing constructions, they do not pattern alike in all aspects: the former differs from the latter in that the pre-shi empty category can be analyzed as an E-type pronoun, a topic-bound variable, or an event-related pro, depending on what it is co-referential with. In addition, the event-related pro cannot be linked to an implicit argument in embedded short-answer sentences, though it can in pseudo-sluicing constructions. Second, this analysis, in conjunction with the one proposed for Mandarin pseudo-sluicing constructions, illustrates that Mandarin Chinese, unlike Dutch and Hungarian, does not rely on the [E]-feature to construct sluicing and embedded fragment-answer sentences, which suggests that the [E]-feature is entirely absent in this language. Therefore, I propose that we should account for the derivation of Mandarin matrix fragment answers in terms of LF-copying, rather than PF-deletion.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The complete sentence mentioned here refers to responses like John ate the cookies as the answer to ‘Who ate the cookies?’, or he saw John as the answer to ‘Who(m) did he see?’.

Not all embedded fragment answers are acceptable in English. Relevant phenomena will be discussed shortly.

The phenomenon that certain verbs can embed fragment answers while some others cannot is also observed in Spanish.

(i)

MacDonald and de Cuba (2013)

a.

Me

dijeron/Repitieron/Parece/Creo

*(que)

Juan.

To me they said/They repeated/It seems/I believe

that

Juan

b.

*Se/Recuerdo/Me enteré de/Descubrí

que

Juan.

I know/I remember/I found out/I discovered

that

Juan

MacDonald and de Cuba call the verbs in (ia) +EFA verbs and those in (ib) -EFA verbs; they account for this contrast by assuming that the complement clause of +EFA verbs has ‘more structure’ than that of -EFA verbs. Thus, fragment answers in Spanish can only move to the additional space of the complement clause of +EFA verbs.

As the discussion proceeds, we will find that Mandarin Chinese does not have genuine embedded fragment answers derived via movement. Thus, all acceptable embedded ‘fragment’ answers in Mandarin Chinese are referred to as embedded short answers in this paper.

One reviewer gave the following example to illustrate the similarity between bridge and non-bridge verbs in Mandarin Chinese:

(i)

a.

Zhangsan

xiangxin

zhe-ben

shu,

Lisi

du-guo.

Zhangsan

believe

this-cl

book

Lisi

read-asp

‘Zhangsan remembered that this book Lisi has read (it).’

b.

Zhagnsan

jide

zhe-ben

shu,

Lisi

du-guo.

Zhangsan

remember

this-cl

book

Lisi

read-asp

‘Zhangsan remembered that this book, Lisi has read it.’

Given the fact that both types of verbs allow embedded topicalization and behave identically in embedding short answers, the reviewer suggested that all verbs might be non-bridge verbs in Mandarin Chinese. However, the following contrast reveals that there still exist some differences between these two types of verbs.

(ii)

a.

Ni

shuo/cai/renwei

weishenme

ta

zuotian

mei

lai?

you

say/guess/think

why

he

yesterday

not

come

‘Why do you say/guess/think that he didn’t come yesterday?’

b.

*Ni

xiangxin/xiwang/jiading/danxin

weishenme

tai

mei

lai?

you

believe/hope/assume/worry

why

he

not

come

‘Why do you believe/hope/assume/worry he didn’t come?’

Lin (1992) notes that weishenme ‘why’ can be embedded in the complement clause of certain verbs but not in that of others. Although two of the main verbs in (iia) are bridge verbs and only some of the main verbs in (iib) are non-bridge verbs, it seems that these two types of verbs do not behave identically in every aspect. Since investigating similarities and differences between bridge and non-bridge verbs in Mandarin Chinese is beyond the scope of this paper, I leave it to future research.

As we will see shortly, this claim is too strong, since it is only applicable to one type of embedded short-answer sentence.

T.-H. Lin (2012) proposes that modals take TPs as complements, which can be finite or non-finite. If we embrace this analysis, shi and the short-answer phrase that follow modals should also be viewed as TP-internal constituents. One of the reviewers asked if we assume that modals have CPs as complements, can shi and the short answer move to the Spec of the embedded CP? This possibility is ruled out for the following reasons.

First, moving shi and the short answer upwards will lead us to the same problem as Park and Li (2016) encounter.

(i)

*Bier

juede

[VP

keneng

[CP

Yuehanj

[C’

shii

[TP

ti

tj]]].

Bill

feel

possible

John

shi

Assuming that shi raises to the head of CP from V within the lower TP via head-to-head movement and that the short answer Yuehan ‘John’ moves to the Spec of the embedded CP, an ungrammatical sentence like (i) is generated.

We can also use one of the diagnostics mentioned in the main text to see if the combination of shi and the short answer reaches the embedded CP domain.

(ii)

Er-zi

renwei

keneng

zhi

shi

yi-zhi

gou.

son

think

possible

only

shi

one-cl

dog

‘Our son thinks/found that it might only be a dog.’

The above sentence can be used in response to the question raised by Mary in (44), in which zhi ‘only’ follows the modal keneng ‘possible’ and precedes shi. Given the fact that zhi ‘only’ appears TP-internally, the grammaticality of this sentence suggests that shi and the short answer do not move to the periphery of the embedded clause.

Wei (2004) classifies predicative wh-phrases into five types; weishenme ‘why’ and shenmeshihou ‘when’ are considered examples of the [preposition [wh-element]] type since wei is said to represent the preposition part in weisheme ‘why’, and shenmeshihou ‘when’ can optionally be preceded by the preposition zai ‘in.’

In Wei’s (2004) analysis, the event pro does not refer to an entire event; instead, it refers to one of the semantic arguments of the event predicate that appears in the antecedent clause, which can be either overtly stated or semantically implied.

Huang (1988) makes it clear that shi in cleft sentences in Mandarin Chinese should not be analyzed as a focus marker in the sense of Teng (1979); instead, it should be analyzed as a raising modal that emphasizes the constituent following it. Nevertheless, in order to facilitate the discussion, I still refer to the shi that possesses the syntactic properties noted in Mandarin cleft sentences as a focus marker in this work.

The pro analysis is also used to account for the derivations of answers to yes-no questions and of corrections in Mandarin Chinese in Wei (2016).

(i)

A:

Ta

kanjian

le

Zhangsan

(ma)?

he

see

asp

Zhangsan

Q

‘Did he see Zhangsan?’

B:

Bushi,

*(shi)

Lisi.

not.be

be

Lisi

‘No, it is Lisi.’

(ii)

A:

Ta

kanjian

le

Zhangsan.

he

see

asp

Zhangsan

‘He saw Zhangsan.’

B:

Bushi,

*(shi)

Lisi

not.be

be

Lisi

‘No, it is Lisi.’

Given the fact that shi cannot be dropped in these cases, Wei proposes that these two types of answers also contain a pro that is base-generated in the position preceding the answer itself. This fact, coupled with the analyses proposed for Mandarin pseudo-sluicing constructions (Wei 2004, 2011) and embedded short-answer sentences discussed in this paper, seems to suggest that as long as shi is present, a base-generation approach must be employed. For details, please refer to Wei (2016).

ec stands for empty category.

One reviewer pointed out that the unacceptability of (ic) is unexpected, given the analyses proposed for Mandarin matrix and embedded short answers in this paper.

(i)

a.

Yuehan

zhaodao

shei?

John

find

who

‘Who(m) did John find?’

b.

Mali

renwei

shi

Bier.

Mary

think

shi

Bill

‘Mary thinks that it is Bill.’

c.

*Shi

Bier.

shi

Bill

‘It is Bill.’

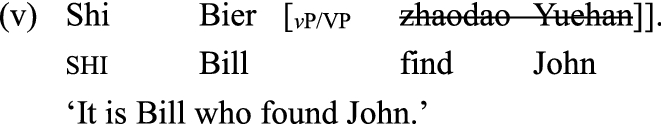

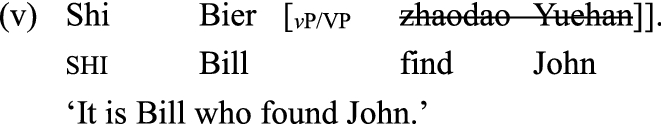

(S)he asked why we can apply the base-generated pro analysis to (ib) but not to (ic), analyzing this response as pro shi Bier. This issue can be addressed from two perspectives. First, the unacceptability of (ic) does not suffice to constitute a counterexample to the analysis proposed in this paper, since the same sequence of words can be felicitously used in the following context.

(ii)

a.

Shei

zhaodao

Yuehan?

who

find

John

‘Who found John?’

b.

Mali

renwei

shi

Bier.

Mary

think

shi

Bill

‘Mary thinks that it is Bill.’

c.

Shi

Bier.

shi

Bill

‘It is Bill.’

In addition, (ic) can become acceptable with the insertion of a modal, like keneng ‘possible.’

(iii)

Keneng

shi

Bier.

possible

shi

Bill

‘Bill is likely to be that person.’

The response in (iii) can serve as an acceptable response not only to (iia) but also to (ia), and it can be analyzed as pro keneng shi[identification verb] Bier. Nevertheless, it is not quite clear why the presence of a modal has an impact on the grammaticality of (ic).

Second, if we view shi in (ic) and (iic) as a focus marker, we can account for the contrast between these two responses. On the one hand, the unacceptability of (ic) can be attributed to the fact that objects cannot be clefted in Mandarin Chinese.

(iv)

*Yuehan

zhaodao

shi

Bier.

John

find

shi

Bill

‘John found Bill.’

The sentence in (iv) is not a well-formed underlying structure in Mandarin Chinese, and the subject Yuehan ‘John’ and the main verb zhaodao ‘find’ do not form a constituent eligible for ellipsis. On the other hand, (iic) can be analyzed as follows.

As we can see here, once we appeal to VP-ellipsis or v-stranding VP-ellipsis (Huang 1991a; Goldberg 2005), (iic) is derived.

The discussion above illustrates the elusive property of shi in Mandarin sentences, and I leave relevant issues to future research.

van Craenenbroeck and Lipták (2009) do not directly claim that Japanese does not have the [E]-feature; they simply say that this feature is “inert” in Japanese.

Both the [+wh]-feature and [+Foc]-feature are considered [+OP]-features in Temmerman (2013).

The analysis that I propose here raises one question: why is the LF-copying analysis not applicable to Mandarin embedded short-answer sentences? That is, what prohibits us from having the following derivation for embedded short-answer sentences?

(i)

a.

Mali

xihuan

shei?

Mary

like

who

‘Who(m) does Mary like?’

b.

*Bier

renwei

Yuehan.

Bill

think

John

‘Bill thinks that Mary likes John.’

(ii)

a.

Deep structure: *Bier renwei [FocP Yuehan [CP Δ]].

b.

After LF-copying: *Bier renwei [FocP Yuehan [CP λx. Mary likes x]].

As we can see above, the response given in (ib) is not acceptable. If we assume that the underlying structure of (ib) is the one in (iia), we should get an acceptable interpretable sentence after LF-copying applies, which is (iib). Nevertheless, this is not the case.

One reviewer proposed that this issue could be dealt with in terms of either the Direct Interpretation approach in the framework of Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar (Nykiel and Kim 2022) or the Direct Compositionality approach in the Categorial Grammar framework (Jacobson 2016). The advocates of the DI/DC approach, unlike those of the PF-deletion and LF-copying analyses, argue that NP fragment answers merely consist of an underlying NP and propose to turn it into a proposition by means of corresponding semantic rules.

The reviewer suggested that the nonstructural approach mentioned above could be used to analyze (ib), assuming what immediately follows the main verb renwei is Yuehan ‘John’ and attributing the unacceptability of (ib) to the incompatibility between these two constituents. By contrast, no such problem arises for matrix fragment answers. However, this assumption is challenged by the following example.

(iii)

a.

Yuehan

shuo

na-yi-ge

nan-dao

yu?

John

speak

which-one-cl

south-island

language

‘Which Austronesian language does John speak?’

b.

Mali

shuo

shi

Tajalu

yu.

Mary

say

shi

Tagalog

language

‘Mary said it is Tagalog.’

c.

#Mali

shuo

Tajalu

yu.

Mary

say

Tagalog

language

Intended meaning: ‘Mary said it is Tagalog.’

The sentence in (iiic) is acceptable when it is understood as Mary speaks Tagalog, but not when used to express the meaning of Mary said it is Tagalog. The fact is unexpected if we apply the DI/DC approach to (iiic). That is, if we apply the DI/DC approach to the NP Tajalu yu ‘Tagalog’ in (iiic), equipping it with a propositional interpretation similar to that of John speaks Tagalog, we should get a felicitous response. Nevertheless, this is contradictory to the fact.

Comparing the LF-copying analysis that I propose here with the DI/DC approach advocated in the literature is not the primary goal of this paper. At this moment, I simply attribute the unavailability of (iia) to the fact that the functional projection hosting a phrase carrying information focus is restricted to the left periphery of a root rather than an embedded clause in Mandarin Chinese, though more evidence is needed for such an assumption.

References

Adams, Perng Wang. 2004. The structure of sluicing in Mandarin Chinese. In Penn Working Papers in Linguistics 10, ed. Sudha Arunachalam and Tatjana Scheffler, 1–16, Proceedings of the 27th Pennsylvania Linguistics Colloquium.

Adams, Perng Wang, and Satoshi Tomioka. 2012. Sluicing in Mandarin Chinese: An instance of pseudo-sluicing. In Sluicing: Cross-Linguistic Perspectives, ed. Jason Merchant and Andrew Simpson, 219–247. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Authier, J.-Marc. 1992. Iterated CPs and embedded topicalization. Linguistic Inquiry 23 (2): 329–336.

Barton, Ellen. 1990. Nonsentential Constituents. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Bhatt, Rakesh, and James Yoon. 1991. On the composition of comp and parameters of V2. In Proceedings of the 10th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, ed. Dawn Bates, 41–52. Stanford: CLSI.

Büring, Daniel. 2007. Intonation, semantics, and information structure. In The Oxford Handbook of Linguistic Interfaces, ed. Gillian Ramchand and Charles Reiss, 445–473. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cheng, L. Lai-Shen. 2008. Deconstructing the shi … de construction. The Linguistic Review 25: 235–266.

Cheng, L. Lai-Shen, and C.-T. James Huang. 1996. Two types of donkey sentences. Natural Language Semantics 4: 121–163.

Chomsky, Noam. 1972. Some Empirical Issues in the Theory of Transformational Grammar. In The Goals of Linguistic Theory, ed. Stanley Peters, 63–130. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Chung, Sandra. 2006. Sluicing and the lexicon: the point of no return. Ms. University of California, Santa Cruz.

Chung, Sandra. 2013. Syntactic identity and sluicing: how much and why. Linguistic Inquiry 44 (1): 1–44.

Culicover, Peter W. 1991. Topicalization, inversion, and complementizers in English. In Going Romance, and beyond: Fifth symposium on comparative grammar, ed. Denis Delfitto, Martin Everaert, Arnold Evers, and Frits Stuurman, 1–43. Utrecht: OTS Working Papers, University of Utrecht.

de Cuba, Carlos. 2007. On (Non)factivity, Clausal Complementation and the CP-field. Doctoral dissertation, State University of New York at Stony Brook.

de Cuba, Carlos, and Barbara Ürögdi. 2010. Clearing up the ‘facts’ on complementation. UPenn. Working Papers in Linguistics 16(1): 41–50.

de Haan, Germen, and Fred Weerman. 1986. Finiteness and verb fronting in Frisian. In Verb Second Phenomena in Germanic Languages, ed. Hubert Haider and Martin Prinzhorn, 77–110. Dordrecht: Foris.

Erteschik-Shir, Nomi. 1997. The Dynamics of Focus Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Evans, Gareth. 1980. Pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 11 (2): 337–362.

Fukaya, Teruhiko, and Hajime Hoji. 1999. Stripping and sluicing in Japanese and some implications. Proceedings of West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics 18: 145–158.

Ginzburg, Jonathan, and Ivan Sag. 2000. Interrogative Investigations: The Form, Meaning, and Use of English Interrogatives. Center for the Study of Language and Information, Stanford, CA.

Goldberg, Lotus. 2005. Verb-stranding VP ellipsis: A Cross-linguistic Study. Doctoral dissertation, McGill University.

Hoekstra, Eric, and C. Jan-Wouter Zwart. 1994. De structuur van de CP: Functionele projecties voor topics en vraagwoorden in het Nederlands. Spektator 23: 191–212.

Hoekstra, Erik, and C. Jan-Wouter Zwart. 1997. Weer functionele projecties. Nederlandse Taalkunde 2: 121–132.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1982. Logical Relations in Chinese and the Theory of Grammar. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1984. On the distribution and reference of empty pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 15: 531–574.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1988. Shuo ‘shi’ he ‘you’ [On ‘be’ and ‘have’ in Chinese.]. The Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology 59(1): 43–64. Taipei: Academia Sinica.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1989. Pro-drop in Chinese: a generalized control theory. In The Null Subject Parameter, ed. Osvaldo Jaeggli and Kenneth Safir, 185–214. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1991a. Remarks on the status of the null object. In Principles and Parameters in Comparative Grammar, ed. Robert Freidin, 56–76. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Huang, C.-T. James. 1991b. Modularity and Chinese A-not-A questions. In Interdisciplinary Approaches to Linguistics: Essays in Honor of Yuki Kuroda, ed. Carol Georgopoulos and Roberta Ishihara, 305–332. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Iatridou, Sabine, and Anthony Kroch. 1992. The licensing of CP-recursion and its relevance to the Germanic verb-second phenomenon. Working Papers in Scandinavian Syntax 50.

Jacobson, Pauline. 2016. The short answer: Implications for Direct Compositionality (and vice versa). Language 92 (2): 331–375.

Kennedy, Christopher, and Jason Merchant. 2000. Attributive comparative deletion. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 18: 89–146.

Kiss, Katalin, É. 1987. Configurationality in Hungarian. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó.

Kizu, Mika. 2005. Cleft Constructions in Japanese Syntax. New York: Palgrave Mamillan.

Krifka, Manfred. 2012. Embedding speech acts. Forthcoming in Recursion in Language and Cognition, ed. Tom Roeper and Peggy Speas.

Kuwagara, Kazuki. 1996. Multiple wh-phrases in elliptical clauses and some aspects of clefts with multiple foci. In Formal Approaches to Japanese Linguistics: Proceedings of FAJL 2, ed. Masatoshi Koizumi, Masayuki Oshi, and Uli Sauerland, 96–116. Cambridge, MA: MITWPL.

Lasnik, Howard. 2001. When can you save a structure by destroying it? In Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 31, ed. Minjoo Kim and Uli Strauss, 301–320. Graduate Linguistics Students Association, Amherst, MA.

Lin, Jo-wang. 1992. The syntax of zenmeyang ‘how’ and weishenme ‘why’ in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 1: 293–331.

Lin, Jo-wang, and Chih-Chen Jane Tang. 1995. Modals as verbs in Chinese: A GB perspective. The Bulletin of the Institute of History and Philology 66: 53–105.

Lin, T.-H. Jonah. 2012. Multiple-modal constructions in Mandarin Chinese and their finiteness properties. Journal of Linguistics 48: 151–186.

Lipták, Anikó. 2001. On the Syntax of Wh-items in Hungarian. Doctoral dissertation, Leiden University.

MacDonald, J. Eric, and Carlos de Cuba. 2013. Embedded fragment answers, sluices and referentiality in Spanish. Paper presented in Linguistic Symposium on Romance Language. New York City, NY.

McCloskey, James. 2006. Questions and questioning in a local English. In Crosslinguistic research in syntax and semantics: Negation, tense, and clausal architecture, ed. Raffaella Zanuttini, Héctor. Campos, Elena Herburger, and Paul H. Portner, 87–126. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 1998. ‘Pseudosluicing’: Elliptical clefts in Japanese and English. In ZAS Working Papers in Linguistics 10, ed. Artemis Alexiadou, Nanna Fuhrhop, Paul Law and Ursula Kleinhenz, 88–112. Berlin: Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft.

Merchant, Jason. 2001. The Syntax of Silence: Sluicing, Islands, and the Theory of Ellipsis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Merchant, Jason. 2003. Subject-auxiliary inversion in comparatives and PF output constraints. In The Interfaces: Deriving and Interpreting Omitted Structures, ed. Kerstin Schwabe and Susanne Winkler, 55–77. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Merchant, Jason. 2004. Fragments and Ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 27: 661–738.

Merchant, Jason. 2007. Voice and ellipsis. Ms. University of Chicago.

Merchant, Jason. 2008. An asymmetry in voice mismatches in VP-ellipsis and pseudogapping. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 169–179.

Nykiel, Joanna, and Jong-bok Kim. 2022. Fragments and structural identity on a direct interpretation approach. Journal of Linguistics 58 (1): 73–109.

Paris, Marie-Claude. 1979. Nominalization in Mandarin Chinese. Département de Recherches Linguistiques, Université Paris 7.

Park, Myung-Kwan, and Zhen-Xuan Li. 2016. On the distribution of the copula shi in Chinese pseudo-sluicing and pseudo-fragmenting. Language and Linguistics 70: 179–208.

Paul, Waltraud, and John Whitman. 2008. Shi…de focus clefts in Mandarin Chinese. The Linguistic Review 25: 413–451.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1981. A second Comp position. In Theory of Markedness in Generative Grammar. Proceedings of the 1979 GLOW Conference, ed. Adriana Belletti, Luciana Brandi, and Luigi Rizzi, 517–557. Pisa: Scuola Normale Superiore di Pisa.

Ross, John Robert. 1969. ‘Guess Who?’ In Papers from the 5th Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, ed. Robert Binnick, Alice Davison, Georgia Green, and Jerry Morgan, 252–286. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Shi, Dingxu. 1994. The nature of Chinese emphatic sentences. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 3: 81–100.

Soh, Hooi Ling. 2007. Ellipsis, last resort, and the dummy auxiliary shi ‘be’ in Mandarin Chinese. Linguistic Inquiry 38 (1): 178–188.

Stainton, Robert. 1995. Non-sentential assertions and semantic ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 18: 281–296.

Stainton, Robert. 1997. Utterance meaning and syntactic ellipsis. Pragmatics and Cognition 5: 51–78.

Stainton, Robert. 1998. Quantifier phrases, meaningfulness ‘In Isolation’, and ellipsis. Linguistics and Philosophy 21: 311–340.

Temmerman, Tanja. 2013. The syntax of Dutch embedded fragment answers: On the PF-theory of islands and the WH/sluicing correlation. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31: 235–285.

Teng, Shou-Hsin. 1979. Remarks on cleft sentences in Chinese. Journal of Chinese Linguistics 7 (1): 101–114.

Uriagereka, Juan. 1999. Minimal restrictions on basque movements. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 17: 403–444.

van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen. 2009. Simple and complex WH-phrases in a split CP. In Proceedings of CLS 43. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen. 2010. The syntax of ellipsis: Evidence from Dutch dialects. New York: Oxford University Press.

van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen. 2012. How do you sluice when there is more than one CP? In Sluicing: Crosslinguistic perspectives, ed. Jason Merchant and Andrew Simpson, 40–67. New York: Oxford University Press.

van Craenenbroeck, Jeroen, and Anikó Lipták. 2009. What sluicing can do, what it can’t and in which language: On the cross-linguistic syntax of ellipsis. Ms., CRISSP/HUB/FUSL/KUL and Leiden University, Leiden.

Vikner, Sten. 1991. Verb Movement and the Licensing of NP-positions in the Germanic Languages. Doctoral dissertation, University of Geneva.

Vikner, Sten. 1995. Verb Movement and Expletive Subjects in the Germanic Languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wang, Chyan-an. 2002. On Sluicing in Mandarin Chinese. MA thesis, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan.

Wasow, Thomas. 1972. Anaphoric Relations in English. Doctoral dissertation, MIT, Cambridge.

Wei, Ting-Chi. 2004. Predication and Sluicing in Mandarin Chinese. Doctoral dissertation, National Kaohsiung Normal University, Taiwan.

Wei, Ting-Chi. 2011. Island repair effects of the left branch condition in Mandarin Chinese. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 20: 255–189.

Wei, Ting-Chi. 2016. Fragment answers in Mandarin Chinese. International Journal of Chinese Linguistics 3 (1): 100–131.

Weir, Andrew. 2014. Fragments and Clausal Ellipsis. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA.

Williams, Edwin. 1977. Discourse and logical form. Linguistic Inquiry 8 (1): 101–139.

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 11th Workshop on Formal Syntax and Semantics at Academia Sinica in Taiwan; I thank the audience for the comments. In addition, this paper benefits considerably from the discussion with Chen-Sheng Luther Liu and Hsiu-Chen Daphne Liao. I am also grateful for the anonymous reviewers and the editor James Huang for giving me insightful questions and suggestions. All remaining errors are my own. This work was sponsored by the Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan (MOST 105-2410-H-009-061).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, CM.L. (Embedded) short answers to wh-questions in Mandarin Chinese. J East Asian Linguist 31, 351–399 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-022-09242-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-022-09242-6