Introduction

When Italian troops conquered Ethiopia's capital city, አዲስ ፡ አበባ/Addis Abeba,Footnote 1 in May 1936 and Benito Mussolini announced the resurrection of the so-called impero (empire), the Fascist regime considered itself at the peak of its power (Labanca Reference Labanca and Rothermund2015, 181–2). Only one month later, however, the idea of consensusFootnote 2 carefully woven around the cruel war of conquest was shaken to the core by the first soldiers returning home from East Africa. In their luggage, many had, among other things, thick bundles of photographs. It was precisely the prints of atrocities illegally taken by soldiers and circulated among them that decisively challenged the official staging of the war as a ‘civilising mission’ and a seemingly exotic (but danger-free) adventure. The public was shocked by these images, and the Fascist authorities reacted and considered having the police confiscate questionable material before soldiers left the ships – a plan that ultimately appeared unfeasible due to the immense numbers of returnees and images (Guerzoni Reference Guerzoni, Bertella Farnetti, Mignemi and Triulzi2013, 117; Mignemi Reference Mignemi and Mignemi1984b, 192). After all, the Fascist government had sent some 350,000 men to East Africa, who were now gradually returning (Labanca Reference Labanca and Steinacher2006, 34). In the end, the pictures’ journeys did not end in the Italian harbours but rather in the returnees’ family homes, where they are often kept to this day. Paolo Bertella Farnetti (Reference Bertella Farnetti and Bertella Farnetti2007b, 7–12), for example, assumes that there must be families in almost every Italian village or city who keep photo collections from the Italo-Ethiopian War.

Research on the connection between colonialism and photography in Italy goes back as far as the 1980s. These very early studies aimed to create visual histories of colonialism through the presentation of visual material. Assuming that photographs would speak for themselves because of their indexical quality, historians pursued mostly descriptive approaches, so that these first works are more like coffee table books than theoretically informed and methodologically grounded analyses (Goglia Reference Goglia1989a). Even though the 1935–41 Italo-Ethiopian War left behind an incomparable amount of visual material, particularly in the private realm (Bertella Farnetti Reference Bertella Farnetti and Bertella Farnetti2007b, 7–12), at first, historians were mainly interested in official, propagandist image production (Mignemi Reference Mignemi1984a). They focused, for example, on the Istituto Nazionale LUCE, the Fascists’ propaganda apparatus, its organisation, and visual leitmotifs (Del Boca and Labanca Reference Del Boca and Labanca2002; Guerzoni Reference Guerzoni2014). Only in the last 20 years – driven by the cultural turn and the ‘discovery’ of the perspective from ‘below’ – has the focus widened to include photographic practices of ‘ordinary’ soldiers, too. Since their images are not usually stored in public archives, several initiatives have emerged to collect, digitise, and thus prepare such collections for research (Steinacher Reference Steinacher2006a; Bertella Farnetti Reference Bertella Farnetti2007a; Bolognari Reference Bolognari2012a; Deplano Reference Deplano2017). As different as the various projects may have been, they were united by the aim of giving a voice to ‘ordinary’ men to subvert the hegemonic discourse of colonial archives (Frascaroli Reference Frascaroli, Bertella Farnetti, Mignemi and Triulzi2013, 38). Behind this enterprise stood the idea that private image collections could offer a more authentic insight into the colonial past compared to the staged imagery of war (Del Boca Reference Del Boca and Isnenghi1996, 436–437; Guerzoni Reference Guerzoni, Bertella Farnetti, Mignemi and Triulzi2013, 118) – which, as Bertella Farnetti (Reference Bertella Farnetti and Bertella Farnetti2007c, 328) rightly argues, they cannot. Private visual practice could hardly resist colonialist indoctrination, thus its visual products do not offer a ‘truer’ insight, but rather one that is complementary (Mignemi Reference Mignemi, De Grazia and Luzzatto2002, 554) to the official narrative of the colonial war.

When historians started to analyse such private photo collections – for instance, trying to identify and distinguish between private and official imageries of war (Pipitone Reference Pipitone2010, 132–4; De Pretto Reference De Pretto2016, 42) – they noticed to their astonishment that collections consisted not only of privately produced images. On the contrary, a large proportion of the photographs in these collections originated from propaganda or commercial contexts of production (Guerzoni Reference Guerzoni2014, 21). Because of the idea that material in private collections would be truly ‘authentic’ and that mass-produced images could merely offer more of the ‘same’, familiar imaginary of war, researchers tended to ignore mass-produced images altogether (Guerzoni Reference Guerzoni2014, 21; Bertella Farnetti Reference Bertella Farnetti and Bertella Farnetti2007c, 322).

When we examine the role of mass-produced images in the Fascists’ consensus-building endeavour, private collections promise to be rich sources.Footnote 3 While several studies have pointed out that the regime used mass-produced visual material as a manipulating consensus-building tool (Goglia Reference Goglia and Goglia1989b, 33–4; Petrella Reference Petrella2016, 11), so far there has been no detailed research on how this kind of visual propaganda played out on the ground. Recent research on private image practices has simply noted that mass-produced images were appropriated by ‘ordinary’ soldiers only as ‘ricordi’ (keepsakes) (Bolognari Reference Bolognari and Bolognari2012b, 129). To address this desideratum, I will use a techno-anthropological approach (Rose Reference Rose2010, 275) and, therefore, consider mass-produced images as communication tools that were embedded in the everyday lives of ‘ordinary’ colonialists in different ways. This approach argues that usage and materiality play a central role in the processes of visual meaning-making (Edwards Reference Edwards2009, 130–50). By looking at the images’ ‘social lives’ (Rose Reference Rose2010, 275), the question at stake is not whether ‘ordinary’ soldiers believed in the content of visual propaganda, but rather how and for which purpose they used mass-produced images – and what new meanings they spawned in the processes of appropriation. Did soldiers affirm dominant colonial discourses laid out in mass-produced images or did they modify or challenge them?

Methodologically my analysis draws on private collections of ‘ordinary’ men who were categorised by the Fascist regime as ‘allogeni’. The term was created to express that they belonged to the native populations in Italy's new provinces in the North and North-East. These had become part of the kingdom only after the First World War, and their inhabitants did not speak Italian as their mother tongue but rather German or Slovenian. The Fascist state considered them as second-class citizens and tried to ‘Italianise’ them through a repressive policy (see below; Pergher Reference Pergher2018, 56–7, 182, 246). Nevertheless, as Italian citizens these non-Italian-speaking men were also subject to compulsory military service (Verdorfer Reference Verdorfer1990, 83). This is also why at least 1,118 German-speakers took part in the Fascist campaign against the Ethiopian Empire in 1935 (Ohnewein Reference Ohnewein and Steinacher2006, 271). In this article I investigate how four of them used mass-produced images they acquired during their war deployments in East Africa. Since it is commonly assumed that this politically marginalised and oppressed linguistic minority did not share the Fascist consensus (Steurer Reference Steurer and Steinacher2006, 237–9), the analysis of their visual practices promises to be eminently telling for this article's epistemological interest.

Colonial war as mass-media spectacle

Like no other colonial war before, the Fascist invasion of the Ethiopian empire represented a mass-mediated event. In 1935 the Fascist party – supported by the royal military – launched an incomparable propaganda campaign to create a homogeneous imaginary of war (Del Boca and Labanca Reference Del Boca and Labanca2002; Guerzoni Reference Guerzoni2014). This campaign was essentially conducted by the Istituto Nazionale LUCE. This institution had already been created in 1925 through the nationalisation of the stock company La Unione Cintematografica Educativa (LUCE) and had been subordinated to the Fascist party's press office (later the Ministry of Propaganda). It was brought into being to shape and control the regime's public image and its political activities in the media landscape – which was also brought into line (Del Boca and Labanca Reference Del Boca and Labanca2002, 11–13, 21–3). Thus, the Istituto was an important part of Fascist consensus-building structures – and remained so during the colonial war in East Africa.

The regime ordered the Istituto to take care of visual war propaganda. This was not necessarily an obvious choice, since the royal army had gained extensive experience in visual propaganda in Eritrea in 1896 and in Libya in 1911–12, as well as during the First World War. In 1934 the army founded a servizio fotocinematografico (cinematographic service) as well as a cinemateca militare (the military's film-related archive), which gave visual propaganda even more attention (Mignemi Reference Mignemi and Mignemi1984b, 189; Goglia Reference Goglia and Goglia1989b, 36). Nevertheless, the fact that the Istituto was within the Fascist party's direct sphere of influence might be the reason why it was ordered to take over visual war propaganda.

Since the regime knew that the attack on Ethiopia would soon have to be legitimised, great importance was attached to visual propaganda (Mancosu Reference Mancosu, Deplano and Pes2014, 268). Visual materials were intended to convince not only Italian society but also foreign countries of the legitimacy of the colonial venture. The regime spared no effort, mobilising great financial, human, and material resources to set up an efficient visual propaganda machine. In September 1935, one month before the start of the war, the Istituto therefore set up the so-called Reparto LUCE Africa Orientale (LUCE division in East Africa) and moved into its headquarters to ኣስመራ/Asmara (Eritrea), where photo and film productions were centrally organised and carried out. This ‘image headquarters’ consisted of administration, archives, magazines, and laboratories for printing as well as developing raw material. It was also equipped with a fleet of vehicles, mobile photo laboratories, and aeroplanes to reach the front lines in far-flung locations(Mignemi Reference Mignemi2003, 125–6; Mancosu Reference Mancosu, Deplano and Pes2014, 268). The Reparto not only had its own photographers and filmmakers, but also coordinated the deployment of the army's visual services: at least a sezione cinematografica (cinematographic division), 16 squadre fotografiche (photographic squads), and 16 squadre telefotografiche (telephotographic squads) were deployed in East Africa (Guerzoni Reference Guerzoni2014, 13).

The visual materials the Reparto produced were passed on to two press offices in ኣስመራ/Asmara and Muqdisho/Mogadiscio (Somalia), which were operated by the Ministry of Propaganda. As the only authorised photo agencies in the Italian colonies, they were responsible for censoring and distributing the material among Italian and foreign journalists, and this is how the material found its way into European newspapers and cinemas (Mancosu Reference Mancosu, Deplano and Pes2014, 268; Baglio Reference Baglio and Bolognari2012, 27). The brutal colonial war was ‘sold’ to audiences as a just one, as an exotic adventure, and as a civilising mission, which was to benefit the defeated (Mancosu Reference Mancosu and Pes2012, 90–1). From October 1935 to May 1936 alone, LUCE employees reportedly produced around 80,000 metres of film material as well as around 8,000 negatives, of which approximately 350,000 copies were made. Army photographers developed and copied an additional 100,000 pictures (Mignemi Reference Mignemi2003, 127; Mignemi Reference Mignemi and Mignemi1984b, 189). But what do these state and military actors have to do with the private collections of ‘ordinary’ colonialists? Their materials were systematically distributed among the latter in large military camps in the form of small-format series. The photographs, however, were not just made to ‘inform’ men about the progress of war, but to shape how they thought of and would remember it in the future (Bondioli Reference Bondioli and Bertella Farnetti2007, 295–6).

It is not the massive propaganda campaign alone which made the war mass-mediated. Due to the boom in visual industries in the 1930s, the East African theatre of war saw more ‘ordinary’ soldiers equipped with photo cameras than any other colonial venue had seen before (Guerzoni Reference Guerzoni2014, 13; Mignemi Reference Mignemi and Mignemi1984b, 194). In the years before the war, cameras and supplies had become much cheaper and much easier to handle, therefore transforming photography into a popular everyday practice in Italy (Goglia Reference Goglia and Goglia1989b, 35; D'Autilia Reference D'Autilia2012, 175–6). While photography was still the exclusive domain of officers and ambitious amateurs during the First World War (D'Autilia Reference D'Autilia2012, 175–6), workers or craftsmen could now also afford it (Wurzer Reference Wurzer2020, 129). Consequently, the colonialists in East Africa represented a generation of ‘visual men’ (Paul Reference Paul2016, 14), who relied heavily on the indexical quality of photography (Barthes Reference Barthes1985, 92), and, therefore, were used to structuring (and communicating) experiences visually rather than in other cultural forms.Footnote 4

Those who could not afford or did not want a camera and extra equipment had another possibility to get pictures in the colonies besides the LUCE services: professional photo studios in both harbour cities as well as in the colonies. To them, the 350,000 or so soldiers who travelled from Italy to East Africa in 1935/6 were well-funded and eager customers. In most private collections there is material which originates from this branch of production (Wurzer Reference Wurzer2020, 132–6). Therefore, it is even more surprising that there has been hardly any research on professional photographers who ran their studios in the Italian colonies, and as a result we know little about their identities and working processes (Labanca and Tomassini Reference Labanca and Tomassini1997, 48).

What we do know is that Italian citizens had already been running professional photo studios in the colonies of Eritrea and Italian Somaliland since the end of the nineteenth century (Goglia Reference Goglia and Goglia1989b, 30). When soldiers arrived in 1935, these studios sold them not only apparatus, supplies, and album blanks, but also photo postcards, and series. Their imagery drew on the orientalist traditions of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century painting and focused on scenes of indigenous life, landscapes, flora, and fauna. However, an important theme was also, of course, the staging of the Italians’ ‘civilising work’, including the construction of bridges, railroads, hospitals, etc. (Goglia Reference Goglia and Goglia1989b, 15–19). Even though commercial photo mass-production followed the rules of the market rather than any directives of the colonial regime, their visual products – alongside those of the propaganda branches and the ‘ordinary’ soldiers – shaped the perception of the colonial war as the exotic adventure of seemingly superior ‘white’ men (Wurzer Reference Wurzer2020, 170–7). Propagandists and commercial and amateur photographers unleashed a veritable flood of images, turning the colonial war into a mediatised spectacle that ordinary soldiers could hardly or did not want to escape.

‘Colonised’ colonisers: German-speaking ‘allogeni’ in East Africa

When the later colonialists from Südtirol/Alto Adige were born, their birthplaces did not yet belong to Italy, but to Austria-Hungary. However, the First World War changed this: after Italy's declaration of war in 1915 the region became an alpine theatre of war. The children who would later become soldiers in the Italian armed forces in Ethiopia, then between two and six years old, experienced the everyday life of war, which was not only marked by supply problems and their fathers’ absence but also by proximity to the front and the presence of the military (Auer Reference Auer2008, 47–135). After the end of the war, in 1920 Italy took possession of the southern part of Tyrol. While Rome had initially adopted a thoroughly liberal attitude towards the German-speaking population in its new province, this changed when the Fascists took power in 1922 (Steininger Reference Steininger2012, 19). The regime quickly began to assert its claim to rule over the province and to affirm its Italian character, so vehemently claimed by nationalistic propaganda, through various measures: anti-Italians were to be ousted, ‘real’ Italians from the old provinces were to be settled, and German-speaking ‘allogeni’ were to be assimilated (Pergher Reference Pergher2018, 56–7). In this regard the citizenship given to the new national subjects functioned as a ‘weapon for assimilation’ (Pergher Reference Pergher2018, 183), because it provided no minority rights to the language group. Without this protection, German-speakers were exposed to the pressure to assimilate that the Fascist regime created through a repressive denationalisation and Italianisation policy (Pergher Reference Pergher2018, 56–7).Footnote 5 Among other measures, topographical German names were exchanged for Italian ones, the Italian language was imposed as the only one in the public sphere, and German first (and in some cases also last) names were ‘Italianised’ (Fuller Reference Fuller, Ferrari, Bagnato and Pasqual2018, 109–11). From 1926 onwards, the German-speaking population was also forbidden any form of political representation. The only party, the Deutsche Verbund (German Bond), was dissolved (Pergher Reference Pergher2018, 64). Through all these measures, ‘not just a colonisation of the land – an ethnic filling-in up to the border – but a radical erasure of [German] Otherness’ was set in motion (Fuller Reference Fuller, Ferrari, Bagnato and Pasqual2018, 111). According to Mia Fuller, ‘the campaign of cultural cleansing that Italy waged in Alto Adige/Südtirol […] was far more detailed, and certainly had an even greater impact, than its equivalent in Libya or any other external colony’ (2018, 109). Fuller describes this province as one of Italy's ‘internal’ colonies (2018, 98–111).

One assimilation measure that affected young men was general conscription. This service had already been introduced in Italy in 1921 (Steinacher Reference Steinacher and Steinacher2006b, 16). Protests by German-speaking men who did not want to serve in the army their fathers had fought against in the First World War went unheeded (Verdorfer Reference Verdorfer1990, 83). What German-speakers experienced in the Italian army was sometimes very different: the spectrum ranged from nationalistically motivated humiliation and harassment by superiors and comrades to men who were promoted and who made careers due to their supposed ‘German’ qualities, such as loyalty and discipline, which were appreciated and rewarded by some superiors (Wurzer Reference Wurzer2016, 34–9; Wurzer Reference Wurzer2020, 106).

The call-up to the colonial war effort in 1935 found the German-speaking men caught between two stools. While the regime propagandistically presented the draftees as truly assimilated, loyal citizens of the Fascist state, separatist movements, such as the Völkischer Kampfring Südtirol (VKS, Ethnic Combat Circle South Tyrol), which was a National Socialist underground organisation, tried to use them for its own political purposes.Footnote 6 Further, in the eyes of most of the province's German-speakers these men were going to war for the real enemy, fascism, which had tried to erase their ‘Germanness’. After the war, veterans saved themselves from any accusation by referring to the compulsory nature of the war service, emphasising experiences of humiliation and marginalisation as well as expressing distance from the Fascist state and its imperialistic agendas (Wurzer Reference Wurzer2020, 107–10, 254–62).

From the analysis of ego documents, however, we know their own ethnic difference in East Africa lost social relevance for many German-speakers in favour of ‘race’, which shaped the colonial reality. ‘Allogeni’ participated in the colonial war in very different functions and branches: while some were ‘only’ bakers, hairdressers, or – if they were judged by the authorities to be particularly politically unreliable – dockworkers, others were involved in the war effort as ‘ordinary’ soldiers and officers, and later also in the brutal counter-guerrilla actions. While most returned to Europe as soon as they could, others stayed, for instance as farmers (Wurzer Reference Wurzer2018, 182). For those who wanted to assimilate as ‘Italians’, the regime certainly offered attractive prospects in the colonial sphere (Wurzer Reference Wurzer2020, 113–14). For most, however, this was out of question for very different reasons, last but not least of which was that only about 30 per cent of the German-speaking soldiers spoke adequate Italian (Ohnewein Reference Ohnewein and Steinacher2006, 269).

In summary, German-speakers in East Africa can be considered as ‘colonised’ colonisers. While in their home province the regime had pursued a restrictive course aimed at the extinction of their Germanness, the colonial project was also designed to assimilate the young men through their military service and to integrate them into the empire as new ‘Italians’ – which hardly succeeded. The next section deals with the connection between mass-produced images, image practices, and consensus-building, and in this respect one may assume that the ‘allogeni’ in East Africa, due to their experiences of marginalisation and oppression, categorically rejected any Fascist propaganda and did not reproduce the imperialist discourse. However, the analysis of their image practices will provide a more complex account.

Social lives of mass-produced images

Collecting

In November 1935 – a month after the war began – Franz/Francesco Kostner (born 1909) went ashore in Muqdisho/Mogadiscio in Italian Somaliland. While he had been a hotelier in his civilian profession, in wartime he was part of the 235th Autoreparto speciale (Special Car Unit) as a driver. As such, it was probably his duty to transport men and equipment by truck along the steadily advancing southern front. In February 1937 he fell ill with malaria and was hospitalised. To recover further he was sent back to Italy in April, where he was discharged in August (Military Register Kostner 1909, 2).

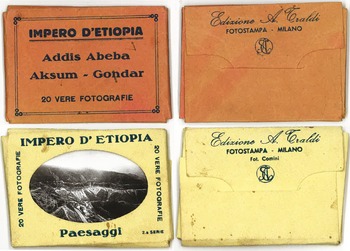

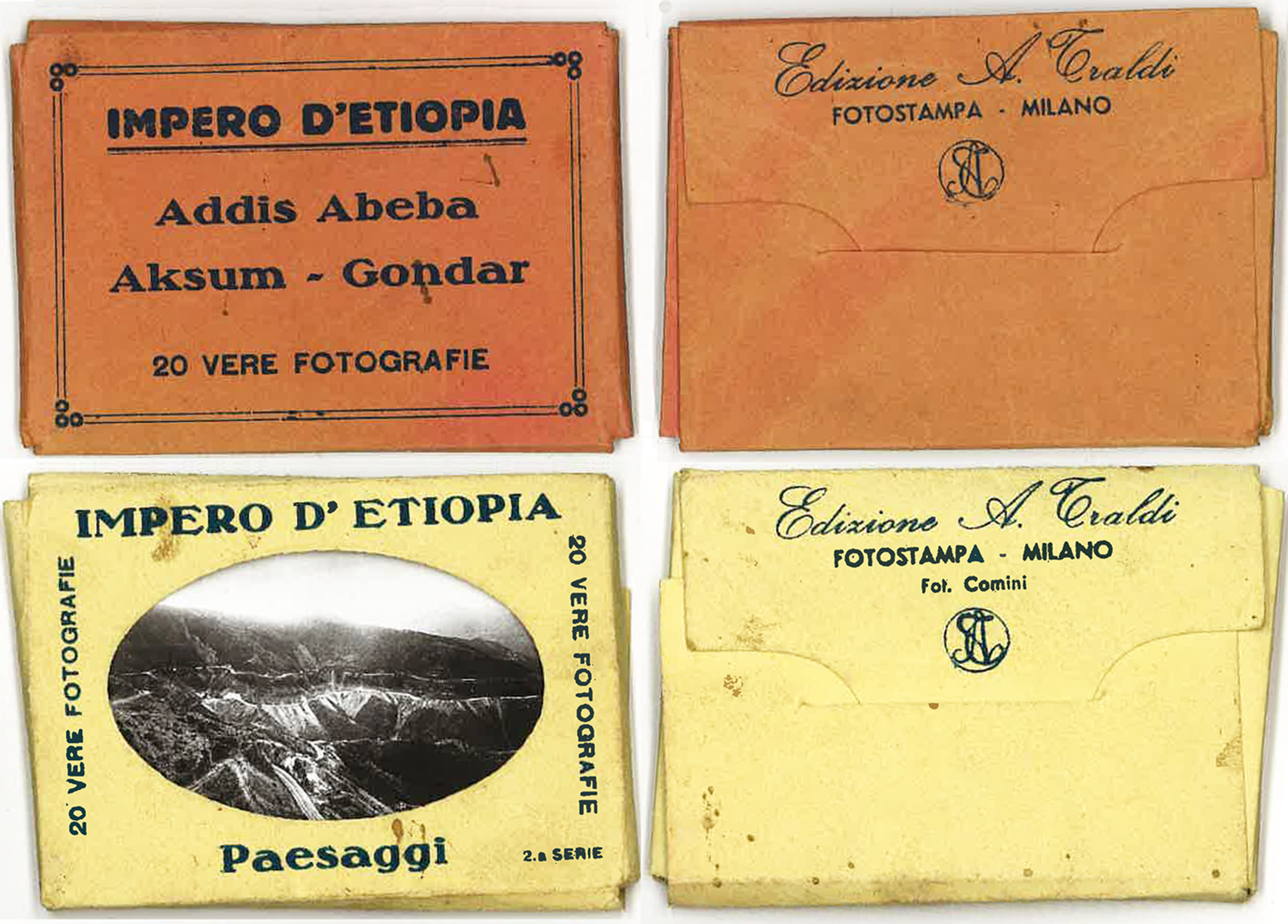

Kostner also carried a camera with him, with which he tried to document his daily life as a driver. In addition, he bought at least two series of mass-produced images from professional photo studios. This can be proved because Kostner – unlike most other soldiers – did not put the photographs in an album or box after the war, but kept them in the original packaging material (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. ‘Impero d'Etiopia – Paesaggi’; Edizione A. Traldi; Tyrolean Archive of Photographic Documentation and Art, Lienz

The back of the packaging reveals that the picture series were published by the Milanese Edizione A. Traldi. The fact that they were also available for purchase in the colonies indicates the transnational interconnections of the colonial image industry. The manufacturer, however, lured potential buyers – as can be seen from the imprints on the fronts – with the claim to contain ‘20 vere fotografie’ (20 true photographs) of important Ethiopian cities like አዲስ ፡ አበባ/Addis Abeba, አክሱም/Aksum, and ጎንደር/Gondar as well as of ‘Paesaggi’ (landscapes) of the ‘Impero d'Etiopia’ (Ethiopian Empire). This label indicates that this image series was produced even before the colonial war started in 1935. For the buyer, this detail seems to have been unimportant, at least with regard to the purchase decision.

In addition, the material form of the packaging had a significant impact on the affordance of the image series. The small-format packages were intended for passing travellers who could easily stow them in their breast pockets or backpacks. Furthermore, the note ‘2.a serie’ on the lower part of the package indicates that such image series were part of even larger series. The small format and the serial character encouraged soldiers to buy several series and to appropriate them, with the promise of gaining as complete and comprehensive an image of colonial space as possible. The collecting of such series formed an arraying practice that served the symbolic appropriation of the seemingly ‘foreign’ world and the normalisation of the colonial war's state of emergency (Axster Reference Axster2014, 118).

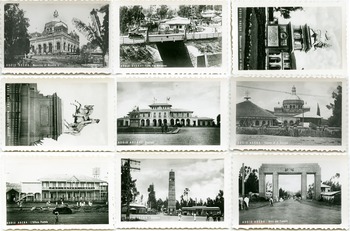

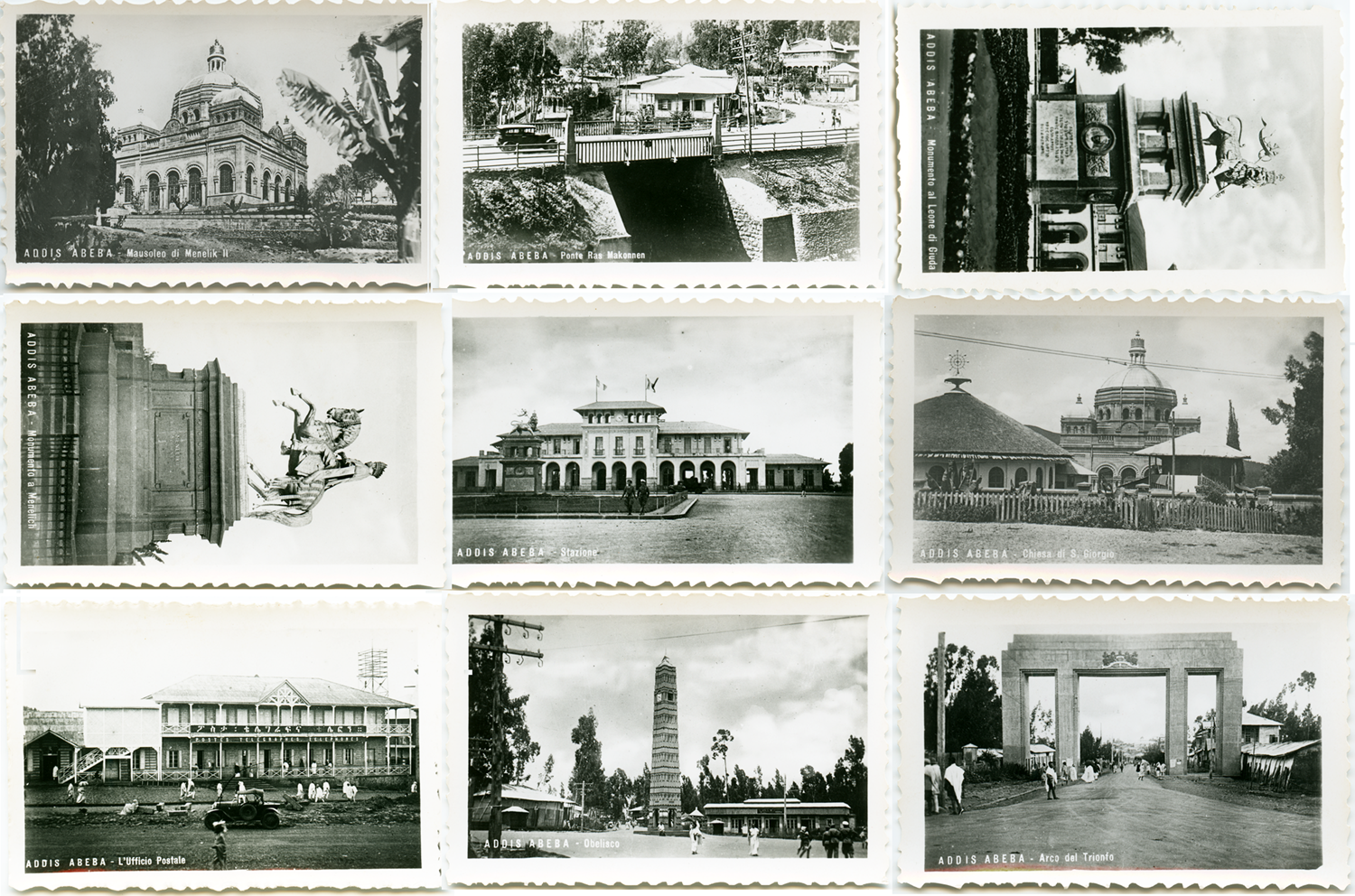

Figure 2 shows nine mass-produced images that were preserved in the upper pack. As promised by the manufacturer on the outside, the pictures show city views of the Ethiopian capital አዲስ ፡ አበባ/Addis Abeba – which Kostner himself most likely never visited. Furthermore, Edizione Traldi provided the pictures with short captions in white, in the lower right or left corners. Labelling, however, is not a neutral practice. Even though it represents a common aesthetic practice of the photo industry, it pursues a particular agenda: By adding a textual frame, producers tried to determine what an imagined audience should (not) perceive in the image detail. They ‘told’ a soldier, for instance, that he was looking at the ‘Stazione’ (rail station), ‘Monumento a Menelick’ (Monument to Menelik IIFootnote 7), or the ‘Ufficio Postale’ (post office). These captions were intended to invoke the visual technology's promise of evidence – just like the imprint ‘20 vere fotografie’ on the packaging – to increase authenticity and with it the value of the photograph (Axster Reference Axster2014, 98).

Figure 2. City views of አዲስ ፡ አበባ/Addis Abeba; Edizione A. Traldi; Tyrolean Archive of Photographic Documentation and Art, Lienz

Through this practice – the sale of images of structures deemed important as collectible pictures or picture postcards – the image industry produced a canon of landmarks over the decades. Most soldiers who entered East Africa in 1935 were imagining their war deployment as a journey (Wurzer Reference Wurzer2020, 155), and, therefore, learned through the consumption of such mass-produced images which sites they absolutely had to see when visiting a city and in front of which – recognisable – landmarks they had to have themselves photographed in order to reaffirm their physical presence.

Finally, it is worth taking a look at the backs of the mass-produced images in the series: Surprisingly, they are all blank. No imprint from the manufacturer, no handwritten note from Kostner specifying date, place, or content – as he did with the majority of the (probably self-photographed) images in his collection. Among soldiers, however, labelling was a specific practice of appropriating images that went beyond mere collecting. This is mainly because by doing so men could position themselves in relation to what was depicted and created independent meanings, whether they affirmed, modified, or negated the manufacturers’ interpretations.

Imitation

Siegfried/Sigisfredo Seppi (born 1912), another German-speaking soldier, came to Eritrea as early as September 1935, scarcely a month before the colonial war began. Because he had been an electrician in his civilian life, he was assigned to a telegraphy detachment of the 8th engineer regiment, which later saw action on the northern front (Military Register Seppi 1912, 2).

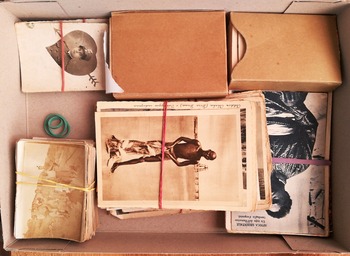

A box with a total of 375 pictures from the colonial war has survived in his family (see Figure 3). Seventy-four of these are mass-produced photo postcards that Seppi acquired in the colonies from various producers and integrated into his collection after he returned home in December 1937. In the process of putting together his collection he even demanded the return of postcards that he had originally sent to his family. As the extensive captions often affixed on their backs suggest, the remaining images were probably made by Seppi with his own camera. They mostly show scenes from his everyday work as a telegraphist.

Figure 3. The private collection of Siegfried/Sigisfredo Seppi, kept by his family in a cardboard box; photo Markus Wurzer

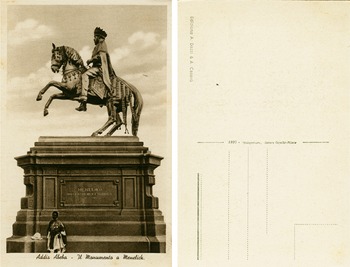

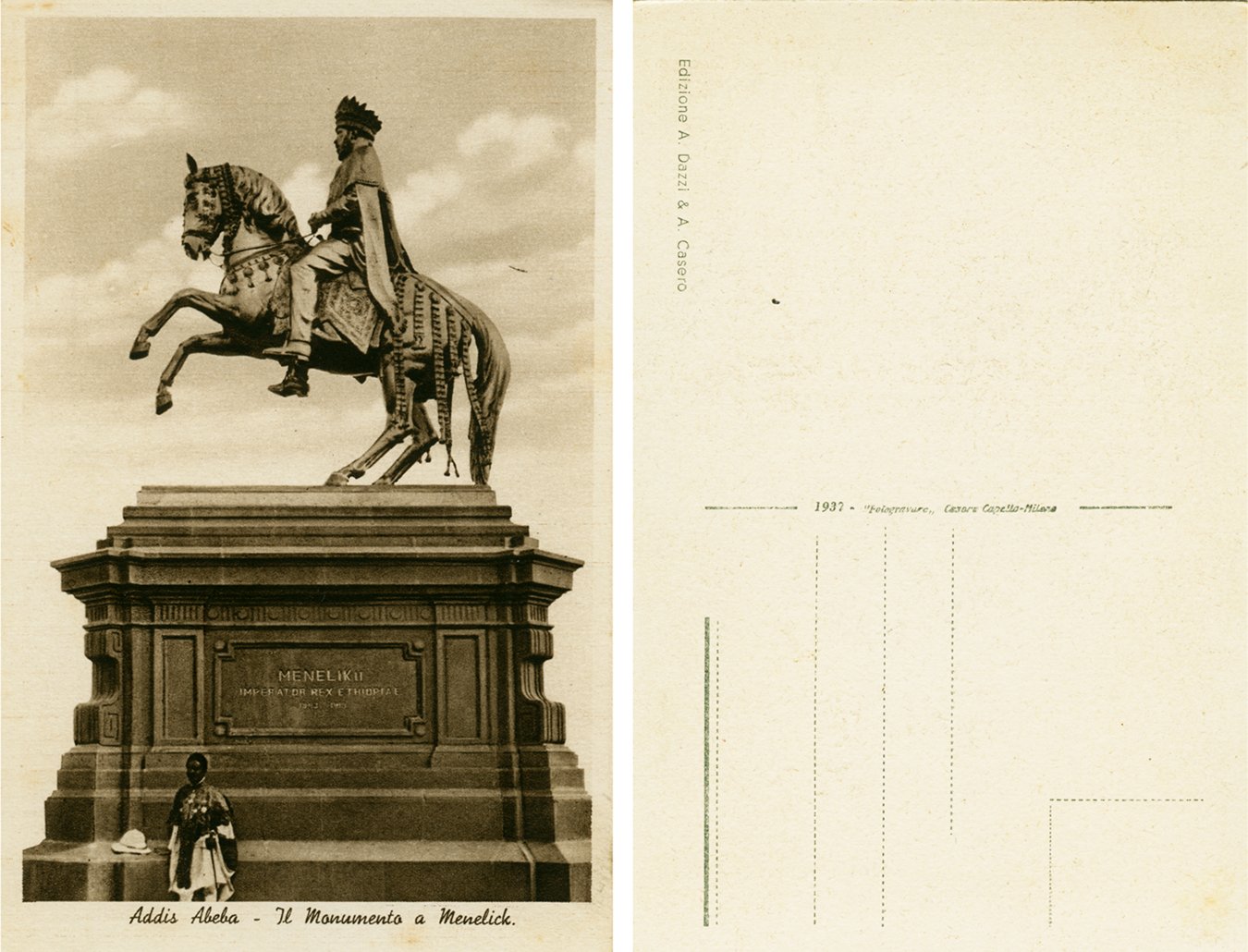

Unlike Kostner, Seppi actually reached አዲስ ፡ አበባ/Addis Abeba during his war deployment. In February 1937, his unit was transferred there from ደሴ/Dessié. During his stay, he used his leisure time to, among other things, explore the city on his own. The analysis of his photo production practices suggests that the destinations he set out for on his walks may have been significantly influenced by the photo industry's canon of landmarks. Seppi bought no fewer than 21 photo postcards showing buildings and monuments around the city – as their backs show, none of them were mailed. That implies that he had acquired them for himself and his collection only. This is actually quite astonishing because it means that Seppi – like many other soldiers whose collections I have surveyed – resisted the objects’ intrinsic affordance: after all, as Figure 4 shows, the format of 6 x 9 centimetres and the standardised imprint on the back, which divides it into three fields for address, message, and stamp, make the visual object only a postcard.

Figure 4. ‘Addis Abeba – Il Monumento a Menelick’; Edizione A. Dazzi & A. Casero; Tyrolean Archive of Photographic Documentation and Art, Lienz

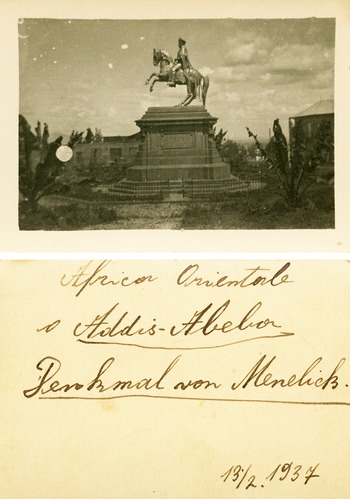

One of Seppi's postcards depicts – according to its caption on the front – a statue of Menelik II (see Figure 4), which actually is – as we learn on its back – the reproduction of a photoengraving (‘fotogravura’) of the Milanese printing company Cesare Capello issued by Edizione A. Dazzi & A. Casero in 1937. The depiction consists of an impressive plinth, a rearing horse, and a crowned man riding on its back. A plaque is set centrally on the plinth identifying the rider as ‘Menelik II / IMPERATOR REX ETHIOPIAE [Emperor and King of Ethiopia] / 1843–1913’. To the left of it stands, based on his clothing, probably an Ethiopian nobleman.

The gaze on the statue – as it is presented in Figure 4 – is by no means chosen at random. It appears that the photographer followed the ‘invitation’ of the architect, the German Carl Härtel (Sefrin Reference Sefrin2018, 118). In the design of the monument, but above all through the plaque on the plinth, the latter tried to direct the gaze of future visitors. For them the plaque marked the side view as the main view. Härtel probably did this because this perspective emphasises, better than the front or rear view, the details and elegance of the bronze sculpture – the rising horse is only connected to the plinth at three points. While this specific gaze was anticipated by the architect for an imagined audience, it was the professional photo studios that made it consumable and rehearsed it through the mass-production and distribution of corresponding images. In the Kostner Collection, for instance, there is also an image of Menelik's statue (see Figure 2, bottom centre). The unknown photographer chose the same format, camera setting, perspective, and composition. The similarity of the two motifs is evidence of the successful production of a city's visual icon in a relatively short time – the statue had been erected only a few years earlier, in 1930 (Sefrin Reference Sefrin2018, 118).

When Seppi came to the city in February 1937, he also visited Menelik's monument and took a photograph of – as we learn from his handwritten German label on the back – the ‘Denkmal von Menelick’ (Monument of Menelik II) with his own camera (see Figure 5). On the back he also noted the time and site of the shot: ‘Africa Orientale [East Africa] / Addis-Abeba / 13./2.1937’.

Figure 5. ‘Africa Orientale / Addis-Abeba / Denkmal von Menelick. / 13.2.1937’; Tyrolean Archive of Photographic Documentation and Art, Lienz

If one compares the motifs of Figures 4 and 5, it becomes evident that Seppi was trying to imitate the standardised gaze he was obviously familiar with due to his consumption of the photo market's products. He situated the statue in the centre of the frame and took aim from the same direction, namely the side, in order to reproduce the iconic imaginary. However, there are also subtle differences: Seppi photographed the monument in horizontal format and did a total shot, instead of in vertical format and a half-total shot. Therefore, Seppi's snap depicts the main subject together with its surroundings in full size. This produces spatial orientation and conveys the basic mood of the space surrounding the statue. The postcard's motif, by contrast, concentrates attention more on the main figure – the statue – and its details, such as Menelik's clothing and the horse's bridle. Furthermore, while the plaque's text was still legible on the postcard, it is no longer so in Seppi's photograph. This was obviously not as important to him as bringing the immediate surroundings, especially the two towering bushes on the left and right, which might have served as seemingly ‘exotic’ ornaments, into the frame.

In any case, the imitation of visual icons is an aesthetic practice that not only served the appropriation of assumed ‘otherness’, but also fulfilled a need for social prestige. After all, many soldiers perceived the war deployment as an adventurous journey to an exotically ‘foreign’ country. The imitated images were thus by no means intended to show something new or unknown, but to repeat well-known icons or stereotypes. The familiar was to prove to an imaginary audience, maybe the family or friends at home, that the ‘soldier-tourist’ had seen everything that was generally considered worth seeing from a European point of view (Pagenstecher Reference Pagenstecher2009, 461).Footnote 8

The handwritten note on the reverse supports the authenticity of what is depicted. The term ‘Africa Orientale’ (East Africa), however, which seems quite objective at first sight and which many soldiers used to localise their pictures at least tenuously, deserves more attention: The Fascist regime referred to its colony on the Horn of Africa, which now consisted of Eritrea, Somaliland and Ethiopia, as ‘Africa Orientale’. Therefore, the term is not just a neutral name; it marks the conquered territory as ‘Italian’ and embodies the claim to rule over it. Through the caption, Seppi reaffirmed and normalised this claim. Because it also makes the conquest of land and people comprehensible and repeatable on a symbolic-visual level, the image also functioned as a war trophy for its owner (Axster Reference Axster2014, 101–2): after all, Menelik II was not just anyone. He had defeated Italy at አድዋ/Adua in 1896. It must be considered that for the German-speaking Seppi the photograph of the statue might also have had subversive potential, namely as a gesture honouring the man responsible for the Italian humiliation. However, the fact that Seppi through his label decidedly located the statue in Italian-dominated ‘Africa Orientale’ rather suggests that he was joining in with an Italian conversation on a final symbolic defeat of Menelik and to make up for the propagandistically created ‘shame of Adua’. It fits with this that the physical statue was toppled by the occupiers shortly after Seppi's visit – which again was a mass-mediated event staged by the Reparto LUCE (Archivio LUCE 1937).

Sending and personalising

Johann/Giovanni Garber (born 1914), who had been a farmer before the war, only arrived in Eritrea in February 1936 as part of the 3rd Regiment ‘Granatieri di Sardegna’ (Grenadiers of Sardinia) Regiment (Military Register Garber 1914, 2). On his way through East Africa, he also reached አዲስ ፡ አበባ/Addis Abeba – where he had himself photographed in front of some sights, including in front of the now empty pedestal of the toppled statue of Menelik (Garber Collection).

His extensive collection also includes two postcards, which he did not buy for himself as a souvenir – as, for instance, Seppi did – but which he used according to their affordance as a means of communication: he addressed them both (in Italian), stamped them, and added short personal messages (in German) for his brother.Footnote 9 That the cards are back in Garber's collection suggests that he reclaimed them after his return home in 1937.

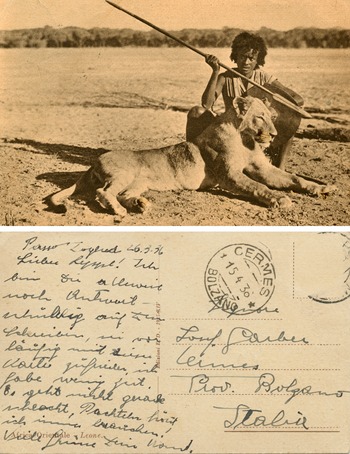

Garber wrote the first postcard (see Figure 6), which he most likely acquired in the colony, a good two weeks after his arrival in ምጽዋዕ/Massaua. On the back it is noted that the postcard was issued in 1935 by Edizioni E. D. The producer also specified the image content with a caption in the lower left corner. It reads: ‘Africa Orientale – Leone’ (East Africa – Lion). A glance at the motif, however, makes clear that not only a lion is depicted in a seemingly ‘empty’ landscape, but also a man. Although he is crouching behind the animal, he is squaring off: while he holds his shield protectively in front of him, his spear is ready for a thrust. Be that as it may, the caption, which highlights the animal and is silent about the man, plus the insinuated attack pose and the elegantly presented lion, suggest a certain ‘proto narrative’ (Kröber Reference Kröber, Kirschenmann and Wagner2006, 171). From the manufacturer's perspective the motif should be understood as a hunting scene – the stance of the spear anticipates the fatal thrust against the lion. Meanwhile, and this may come as a surprise, in the personal message that Garber addressed to his brother on the reverse, he did not refer to the motif depicted at all. He neither explicitly reaffirms nor challenges what is shown. It seems like he accepted the propaganda's content and instead considered the motif a suitable representation of colonial reality, which could speak for itself and would need no commentary in order to ‘inform’ the audience at home about his experiences in situ. He merely apologised for not having contacted him sooner with a detailed letter, asked for understanding that he had little time, and told his brother that he was not doing too badly.

Figure 6. ‘Africa Orientale – Leone’; Edizioni E. D.; Tyrolean Archive of Photographic Documentation and Art, Lienz

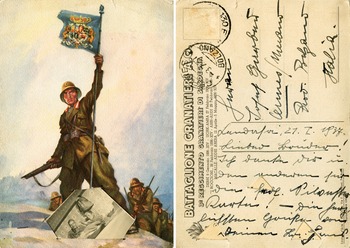

Garber sent the second postcard (see Figure 7) to his brother about ten months later. As can be seen from the footnote on the back, it was produced by the Roman publishing house ‘Edizioni d'Arte V. E. BOERI’. However, this was not just any publisher: The eponymous Vittorio Emanuele Boeri had been a fascist from the very beginning and later also an officer in the Fascist militia; after the March on Rome in 1922, he had founded the publishing house there, which was known for producing mainly propaganda content that put the royal armed forces, party organisations, or colonial projects in a good light (Brilli and Chieli Reference Brilli and Chieli2001, 28–49).

Figure 7. ‘BATTAGLIONE GRANATIERI A. O.’; Edizioni V. E. Boeri; Tyrolean Archive of Photographic Documentation and Art, Lienz

In the present case, it is – as the reverse also reveals – a postcard dedicated to a particular troop body, the ‘Battaglione Granatieri A.[frica] O.[rientale]’, a battalion that had been specially deployed for the African war effort in East Africa by the ‘3rd Reggimento Granatieri di Sardegna’. Garber belonged to this military body. It is therefore reasonable to conclude that he did not buy this mass-produced postcard in one of the colonies’ souvenir shops, but that it was distributed among the associated soldiers via military logistics to strengthen the esprit de corps and to spread the idea that this battalion was a particularly brave and battle-hardened one. In keeping with this, the sites where the troop had apparently stood victoriously in battle during the Italo-Ethiopian War are listed on the reverse.

Primarily, however, this proto narrative is supported by the motif on the forefront: What can be seen are soldiers charging uphill at the viewer with bayonets attached for close combat. These men are undoubtedly recognisable as grenadiers because of their distinctive red-white-red collar tabs. The colonial uniform moves the depicted scene into the colonial sphere. Moreover, the soldier in front is not ramming the Italian flag or the Fascist party's emblem into apparently African soil, but rather the battalion's symbol.Footnote 10 Finally, the raising of a flag functions as a clear gesture of victory.

Moreover, Garber's postcard also demonstrates another way in which ‘ordinary’ men dealt with mass-produced images: he not only sent the postcard, but he also personalised it by assembling a display detail of a private snapshot into the postcard's motif. It shows Garber – also wearing grenadier collar tabs – and another soldier in a cheerful mood lying against wallpaper. The shape of the display detail follows both pragmatic and aesthetic reasons: Garber used a clamping technique to fix the smaller image, in addition, it imitates the composition of the approaching soldiers – a triangle – and functions as a ‘rock’ for the flagpole. For all these reasons, the smaller image integrates well into the postcard motif.

Through this intervention, Garber also modified the meaning of the postcard: it juxtaposes the representations of violence and idyll, which, however, do not form a contrast. Conversely, combat and calm are alternating, complementary components of soldierly worlds of experience. On the postcard, Garber links these through the staging of comradeship and positions himself towards the audience, his brother, within the interpretation of the Granatieri as seemingly successful conquerors and himself as one of them. This reading fits with the wider archive of Garber, which suggests that he took pride in being a member of the Sardinian grenadiers.

In this case, too, Garber did not address the image in his message. It was probably meant to speak for itself. Through such postcards circulating between the colony and the home province, however, colonial knowledge seeped almost casually into the living rooms of Italian families. Pictures do not simply show something – they are ‘institutions of world production’ (Tropper Reference Tropper, Musner and Uhl2006, 106) and, therefore, bring forth ideas about something. Hence, the proto narrative offers normalised colonial conquest through the mass distribution of images, and, as in the cases under discussion, an imagined Ethiopia as a land of ‘wild’ animals and underdeveloped indigenous people, as well as a war that is solely a victorious advance without death or wounding.

Remembering

All the mass-produced images discussed so far were kept by their owners even after they returned home from East Africa. The return, however, marked a break in the materials’ ‘social lives’. The now veterans detached them from their previous contexts of usage and refunctionalised them as media of remembrance. The images were now no longer trading cards or postcards but served as occasions to call up memories and articulate them to the familial audience.

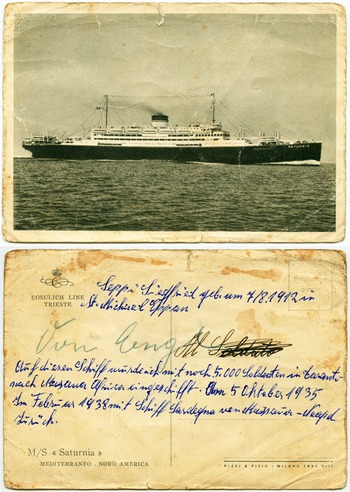

Seppi, for instance, remained unmarried after his return home and lived with his sister's family. He kept his visual collection in a small box (see Figure 3), to which he also added the postcards he had sent to his parents and his two siblings. Figure 8 shows an example of the different contexts in which pictures were used in the course of their ‘biographies’.

Figure 8. ‘M/S «Saturnia» / MEDITERRANEO – NORD AMERICA’; Pizzi & Pizio; Tyrolean Archive of Photographic Documentation and Art, Lienz

This is a postcard, issued in 1935 by the Milanese publishing house Pizzi & Pizio, depicting the ship M/S Saturnia of the Triestine shipping company Cosulich. In Seppi's collection there are another four postcards of this ship. It can be assumed that these postcards were issued to soldiers on the ship so that they could write to their families. In any case, Seppi sent three to his family at the start of his journey. He kept the other two, although the address field of the card in Figure 8 shows that Seppi had already started to write an address. It seems that he had changed his mind, kept it, and crossed out ‘Al Soldato’. Next to it, in light blue letters, is the text ‘Von Engl’ (from Engelbert, Seppi's brother), which could indicate that the visual object also ‘travelled’ within the family. In later years, Seppi added the text in dark blue, thus making the postcard functional as a remembrance medium. He left his biographical data and noted the start and end dates of his ‘war voyage’, and added that this ship was the one that brought him to East Africa in 1935.

Garber too kept his visual material – along with letters and postcards he had sent home – but, in contrast to Seppi, he did not do anything with it for decades. This only changed in the 1980s, when his wife decided to arrange it in a leather-bound album as a Christmas gift for him. She did not arrange the photographs and postcards in any order, neither thematically nor chronologically, nor did she label them. By gluing them in, however, the backs were also concealed and with them information about producers or original contexts of use. In other families, too, it was often the wives and daughters of veterans who took care of the colonial image collections as self-appointed ‘archivists’ and ensured their preservation and presentation. In many families, it was they who ensured that the image collections were not disposed of because of lack of interest or in the event of the death of the veteran, but were kept for the next generations: as a result, these colonial remnants can still be found in German-speaking families today (Wurzer Reference Wurzer2020, 292–301).

Other veterans, however, were very concerned with their collections after they returned home from the colonies. According to Benedetta Guerzoni (Reference Guerzoni2014, 21), creating an album represented the most popular way for returnees to process their colonial experience. One of them was Oskar/Oscar Eisenkeil (born 1910), who had been in East Africa from 1935 to 1939. He had first been a non-commissioned officer in the intelligence corps and, after completing a training course, an officer who took command of an ‘Ascari’Footnote 11 company in counter-guerrilla operations (Military Register Eisenkeil 1910, 3–5). He left two extensive albums in which he relates his colonial war deployment chronologically as a huge journey, starting with the farewell in Naples and ending with the return to his hometown of Meran/Merano. In order to tell a supposedly coherent narrative about his war deployment, he used not only photos he had taken himself, but also material from the commercial photo market, the Reparto LUCE, and the military services (Eisenkeil Reference Eisenkeil1973, 17).

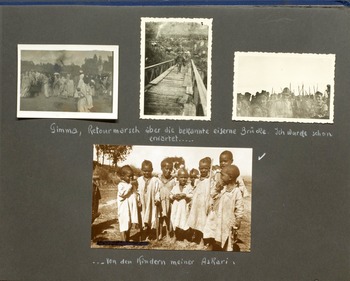

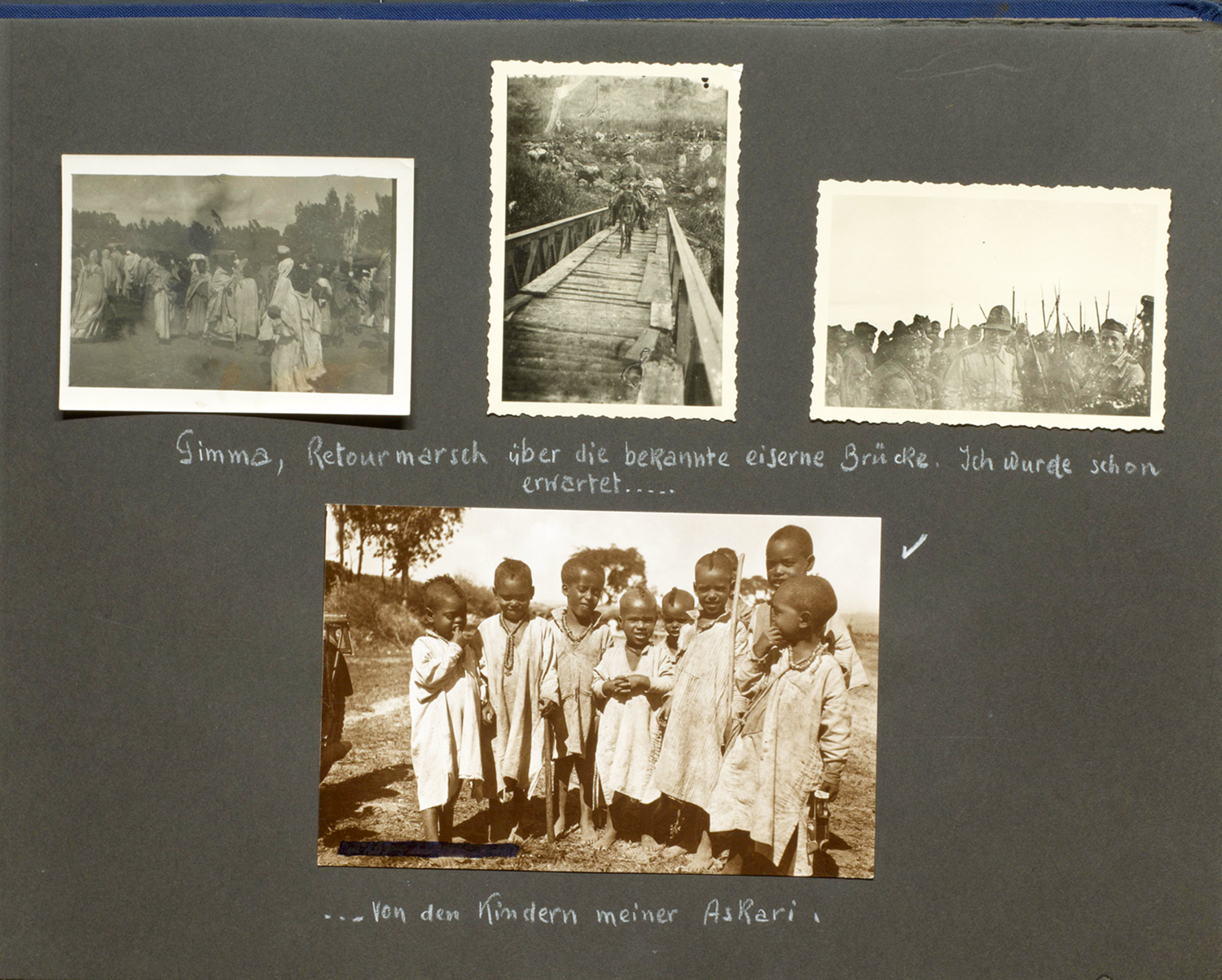

Figure 9 depicts page 22 of Eisenkeil's second album. On it the veteran presents an episode of returning to the battalion's camp after a counter-guerrilla action. Three pictures he took himself introduce the episode. While the two pictures on the top left and top right show indigenous people and officers of his battalion, the picture in the middle is the main motif: It depicts Eisenkeil riding a horse during the ‘return march across the famous iron bridge’ (‘Retourmarsch über die bekannte eiserne Brücke’). The story is continued by the large-format picture below, which shows a group of indigenous children in landscape format. Eisenkeil noted underneath the image that he was already expected in the camp ‘by the children of my Askari’ (‘von den Kindern meiner Askari’). However, these were not their children. It is obvious that the picture is not a private snap but a commercially produced postcard. In order to conceal this, Eisenkeil made the caption in the lower left corner unrecognisable. He thus modified the meaning of the postcard – probably for lack of his own pictures – put it into a new context of meaning, and, thus, transformed the unknown children into those of his inferiors. It seems that the fact that the motif was not representing them does not disturb his narrative: on the contrary, it supports it.

Figure 9. ‘Gimma [ጅማ], Retourmarsch über die bekannte eiserne Brücke. Ich wurde schon erwartet von den Kindern meiner Askari.’ (Return march over the well-known iron bridge. I was already expected by the children of my Askari.); page 22 in Oskar/Oscar Eisenkeil's second album; Tyrolean Archive of Photographic Documentation and Art, Lienz

Conclusion

The 1935–41 Italo-Ethiopian War was a mass-media spectacle – not least because of the extensive circulation of images mass-produced by the state and military but also commercial players. As visual men, ‘ordinary’ soldiers not only appropriated them as souvenirs, but also used them according to their affordance (or in contrast to it) in very different everyday communication contexts. Men bought and sent mass-produced images, but they also used them as models for their own production or as barter goods. Through these practices, they created new meanings that reinforced or modified – but, and this is essential, did not break – those established by the colonial regime.

This is particularly relevant for the present analysis, because it is present in the visual practices of so-called ‘allogeni’, who were suppressed and marginalised by the Fascist regime. Even after the downfall of the regime in 1943 and the final loss of the colonies in 1947, this did not change: as commemorative media, the images now served the veterans in the form of albums or boxes as occasions to recall their memories. But the colonial war continued to be presented as an exotic adventure, a civilising mission, and its owners as its protagonists. And so the mass-produced images concealed the colonial mass violenceFootnote 12 even a long time after the Fascist ‘consensus machine’ had decommissioned its work.

When the veterans died, their collections often ended up in the hands of their children. With their deaths, however, the material's meanings were also threatened with collapse, because they were the only ones in the family who could link the visual content with their experiences (Erll Reference Erll2017, 148). What remains are proto narratives that offer specific imaginations about the colonial past, which can be condensed into the myth of the ‘brava gente’ (Del Boca Reference Del Boca2014). Behind this is the idea that the Italian colonisers were particularly humane and that their rule above all benefited the colonised. This myth was created during the colonial period – also through visual propaganda – and still dominates the collective memory of colonialism in Italy today (Triulzi Reference Triulzi, Andall and Duncan2010, 24). This historical imagination is also deeply rooted in family memories. This is because there the idea of the good colonisers is personalised in the figure of the (grand)father, who, of course, is assumed to be a morally good person by his relatives. Furthermore, this idea is enriched by (mass-produced) images. For descendants, it is often impossible to tell which producers images originate from – to them, they all possess the same authenticating power, and, therefore, tell an alleged ‘truth’. Therefore, it is high time to decolonise private image collections, which means not leaving the proto narratives unchallenged but making them objects of critical analysis.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my anonymous reviewers for their constructive engagements with my manuscript. I am also thankful to the guest editors, Laura Moure Cecchini and Carmen Belmonte, for considering my manuscript for publication. The copy-editing was financed by the Max Planck Society in the framework of the Independent Max Planck Research Group ‘Alpine Histories of Global Change: Time, Self and the Other in the German-Speaking Alpine Region’.

Competing interests

the author has declared none.

Markus Wurzer is a historian and postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Halle. His research has taken him to the Austrian Historical Institute in Rome, the International Research Centre for Cultural Studies (IFK) in Vienna, the European University Institute (EUI) in Florence, Harvard University in Cambridge, MA, and the European Academy (EURAC) in Bolzano/Bozen. Wurzer is co-coordinator of www.postcolonialitaly.com and has received numerous prizes for his work, including the 2019 award of the Theodor Körner Fonds for his dissertation. In his PhD thesis he focused on Italy's colonial enterprise against Ethiopia (1935–1941) in visual culture and family memories.