Abstract

I show that speaker bias in polarity focus questions (PFQs) is context sensitive, while speaker bias in high negation questions (HNQs) is context insensitive. This leads me to develop separate accounts of speaker bias in each of these kinds of polar questions. I argue that PFQ bias derives from the fact that they are frequently used in conversational contexts in which an answer to the question has already been asserted by an interlocutor, thus expressing doubt about the prior assertion. This derivation explains their context sensitivity, and the fact that similar bias arises from polar questions that lack polarity focus. I also provide novel evidence that the prejacents of HNQs lack negation, and thus only have an outer negation reading (see, e.g., Ladd in Papers from the seventeenth regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society, vol. 17, pp. 164–171, 1981; Romero and Han in Linguistics and Philosophy 27(5):609–658, 2004; Krifka in Contrastiveness in information structure, alternatives and scalar implicatures, pp. 359–398, 2017; AnderBois in Questions in discourse, pp. 118–171, 2019; Frana and Rawlins in Semantics and Pragmatics 12(16):1–48, 2019; Jeong in Journal of Semantics 38(1):49–94, 2020). Based on a treatment of HNQs as denoting unbalanced partitions (Romero and Han in Linguistics and Philosophy 27(5):609–658, 2004), and competition with their positive polar question alternatives, I propose a novel derivation of speaker bias in HNQs as a conversational implicature. Roughly, if the speaker is ignorant, then a positive polar question will be more useful because it is more informative, so the use of an HNQ conveys that the speaker is not ignorant. The denotation of the HNQ then makes clear which way the speaker is biased. The result separates high negation from verum focus, and I argue that it is more parsimonious and has better empirical coverage than prior accounts.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Romero and Han (2004) observe that both high negation questions (HNQs) like (1) and polarity focus questions (PFQs) like (2) convey that the speaker has a bias for the answer with opposite polarity from that of the question.Footnote 1

-

(1)

A: Ok, now that Stephan has come, we are all here. Let’s go!

B: Isn’t Jane coming?

⇝ B previously believed that Jane is coming

(Romero and Han 2004, p. 610)

-

(2)

B: Ok, now that Stephan has come, we are all here. Let’s go!

A: Wait, Jane’s coming too.

B: IS Jane coming?

⇝ B previously believed that Jane isn’t coming

Given the strikingly similar bias of these two question types, Romero and Han pursue a unified analysis of high negation and verum focus (Höhle 1992).Footnote 2 They propose that an epistemic conversational operator verum is introduced to the LF by high negation in (1) and verum focus in (2). It plays a crucial role in the derivation of speaker bias, and is subject to discourse constraints meant to explain the restricted distributions of both kinds of questions. Repp (2013) adds a negative version of verum, the falsum operator, and Frana and Rawlins (2019) develop a dual verum/falsum account of biased questions (see also Romero 2015; Romero et al. 2017; Jeong 2020). Other recent work has adopted the claimed connection between verum focus and biased questions, and sometimes also high negation, even though it does not directly employ the above verum and falsum operators (AnderBois 2011, 2019; Samko 2016; Taniguchi 2017; Gutzmann et al. 2020; Silk 2020; Bill and Koev 2021).

The question that motivates much of the research cited above also motivates this paper: why do HNQs and PFQs convey the biases that they do? I offer two distinct answers, one for HNQs like (1), another for PFQs like (2). The reason is that there are empirical asymmetries between HNQs and PFQs: bias in PFQs is context sensitive, while in HNQs it is not, as I demonstrate in Sect. 2. This leads me to formulate a novel account of PFQ bias in Sect. 3, in which the bias derives from general pragmatic principles in combination with the conversational contexts that PFQs happen to frequently appear in. This account does not make use of verum or falsum operators, but it also does not depend directly on the presence of focus marking. I compare my account with verum accounts of PFQ data.

Then, to understand the role of preposed negation in HNQs, I deploy a battery of tests for negation in polar questions in Sect. 4. The tests reveal that the prejacent of HNQs is not negated, contra the position of many researchers who argue that negation in HNQs can scope low. This leads me to conclude that the only position for negation in HNQs “is somehow outside the proposition” (Ladd 1981). In Sect. 6, I analyze high negation as scoping over a doxastic speech act operator. This structure denotes an unbalanced partition, similar to denotations proposed in Romero and Han (2004) and Krifka (2017).

In Sect. 7, I develop a novel account of the necessary inference that the speaker is biased for the prejacent of the HNQ. In brief, the HNQ competes with a PPQ alternative that is, in a sense, more informative. I argue that a speaker ignorant of whether p or ¬p should prefer the stronger PPQ; thus, if they use the HNQ, they must not be ignorant, that is, they must be biased. Finally, the manner in which the HNQ is unbalanced leads to the inference that they are biased for the positive answer.

2 Asymmetries between kinds of polar questions

2.1 The asymmetry between HNQs and LNQs

Since Romero and Han (2004) (with antecedents in Ladd 1981), HNQs have been known to require the speaker to have a bias for the positive answer, while their low negation counterparts do not. To appreciate Romero and Han’s observation, compare (3), in which both the HNQ and the low negation question (LNQ) are acceptable, to (4) and (5) where only the LNQs are acceptable.

-

(3)

A expects her roommate Moira to be home, but she looks everywhere and can’t find her. A finds their mutual roommate B in the last room that she checks. A says to B:

-

a.

Is Moira not home? low negation question (LNQ)

-

b.

Isn’t Moira home? high negation question (HNQ)

-

a.

-

(4)

A wants to find Moira, but has no expectations about whether she is home or not. She looks everywhere and can’t find her. But A does find B, and says:

-

a.

Is Moira not home?

-

b.

# Isn’t Moira home?

-

a.

-

(5)

A has been in a windowless office for the last eight hours. It is equally likely that it could be nice out or not. Then B walks in rubbing his hands together and stamping his feet, and says, “I hate the weather in this town!” A replies:

-

a.

Is it not nice out?

-

b.

# Isn’t it nice out?

-

a.

In all three examples, there is compelling contextual evidence for the negative answer, which is one way to license an LNQ (Büring and Gunlogson 2000; see (14b) below); thus, all of the LNQs are acceptable. But only in (3) does the speaker A have a prior expectation that the positive answer is true, and only in that context is the HNQ acceptable. Data like this has led researchers to posit the following generalization (Romero and Han 2004; Sudo 2013; Domaneschi et al. 2017; AnderBois 2019; Frana and Rawlins 2019):

-

(6)

Speaker bias condition:

An HNQ with propositional content p below the negation (HNQ-p) is felicitous only if the speaker is or was recently biased for p

Romero and Han show that the generalization holds in several languages besides English, including Modern Greek, Spanish, Bulgarian, Korean, and German (see also Hartung 2009 on German HNQs). It has also been claimed in Hungarian (Gyuris 2017) and Turkish Sign Language (Gökgöz and Wilbur 2017).Footnote 3 Since the phenomenon is crosslinguistic, we would like to have a principled explanation for it. As AnderBois (2011, p. 223) notes, this poses a challenge for Romero and Han’s account, since they stipulate that preposed negation introduces verum (p. 613), and so the link between preposed negation and speaker bias remains unexplained.

2.2 Asymmetries between HNQs and PFQs, and also really-Qs

There are two asymmetries between HNQs and PFQs. First, focus marked expressions require an antecedent in which backgrounded (non-focused) material is given (see Kratzer 1991; Rooth 1992; Schwarzschild 1999, i.a.). Polarity focus in PFQs is no different in this regard. For example, in (2), B’s use of polarity focus is licensed by A’s utterance, which provides the required antecedent for the prominence shift. Compare this to (1), repeated in (7) with added example sentences, in which the antecedent for polarity focus is missing from the context.

-

(7)

A: Ok, now that Stephan has come, we are all here. Let’s go!

-

a.

B: Isn’t JANE coming? (Romero and Han 2004, p. 610)

-

b.

B: # ISN’T Jane coming?

-

c.

B: # IS Jane coming?

-

d.

B: Is JANE coming?

-

a.

If prominence is shifted to the auxiliary as in (7b), the HNQ becomes infelicitous. The PFQ (7c) is also infelicitous, even though the same question without polarity focus in (7d) is felicitous. The asymmetry between (7a) and (7c) in particular poses a challenge for verum/falsum accounts that unify the two kinds of questions: if the distributions of both HNQs and PFQs were regulated entirely by conditions on the use of verum/falsum, then their distributions should not come apart in this way.

The explanation for (7) must be that the prominence shifts in (7b) and (7c) are polarity focus, and so require an appropriate focus antecedent that is not found in the context. But high negation in (7a) is not a kind of focus, and so doesn’t require the same kind of focus antecedent.Footnote 4

The second empirical asymmetry between HNQs and PFQs is that HNQs necessarily convey a speaker bias, while the speaker bias conveyed by PFQs is context sensitive. To see this, compare the biased PFQ in (2) to the PFQ in (8a), which is felicitous but unbiased.

-

(8)

B wants to know whether Jill will be at a meeting for members only. But B has no clue whether Jill is a member.

B: Will Jill be at the meeting?

A: If she’s a member, she will.

-

a.

B: IS she a member?

\(\not\leadsto\) B believed she isn’t a member

-

b.

B: # ISN’T she a member?

⇝ B believed she is a member

-

a.

Despite the fact that the context of (8) stipulates that B lacks a bias about whether Jill is a member, the PFQ in (8a) is perfectly felicitous. The HNQ in (8b) on the other hand is infelicitous in this context, presumably because the bias it necessarily conveys clashes with the context. If both of these question types introduce a verum or falsum operator that triggers speaker bias, then this asymmetry is unexpected.

The central fact about HNQs is that they always convey a bias for the propositional prejacent of the question, as laid out in (6). (8) shows that it is an equally crucial fact about PFQs that they do not always convey a speaker bias. Instead, PFQ bias seems to be conditioned by the context.

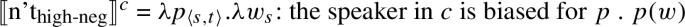

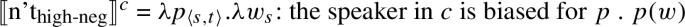

Finally, a reviewer points out that Romero and Han (2004, p. 624ff.) first introduce the verum operator relative to the adverb really, which also creates negative bias in polar questions, and asks how really fits into the picture I have painted. I take really to be a distinct phenomenon from polarity focus and high negation. First, the question “Is she really a member?” would be infelicitous in (8). Second, if you ask if I got a haircut, I can reply, “I DID get a haircut,” whereas “I really did/DID get a haircut” would be infelicitous. See further discussion of the differences between polarity focus and really in Gutzmann et al. (2020, p. 17, fn. 7) and Goodhue (2022a, p. 154). In Sect. 3.7 below, I propose an analysis of really-Q bias.

3 Why some polarity focus questions are biased

My account of bias in PFQs is based on the kinds of conversational contexts they happen to frequently appear in, in combination with general pragmatic principles.Footnote 5 In a nutshell, if an interlocutor implies some proposition p, then a speaker can cast doubt on p just by virtue of asking a polar question about whether p (which I abbreviate as ?p). In other words, the speaker questions the implied proposition p, thereby casting doubt on p. Via a further pragmatic process, this doubt can be strengthened into a bias for ¬p. One prediction of this account is that polarity focus is not required in order for bias to be derived; there could be focus elsewhere in the sentence (e.g., the subject or the verb), or even no focus at all. Another prediction is that the polarity of the bias need not oppose the polarity of the question. I compare my account to verum accounts.

3.1 Account of speaker bias in PFQs

Consider the following biased PFQ:

-

(9)

A: Dinah likes Ivy.

B: DOES Dinah like Ivy?

⇝ B believed that Dinah does not like Ivy

Let p be the proposition that Dinah likes Ivy. Using “□” to represent doxastic necessity, we can abbreviate the goal of our bias derivation as □¬p. In (9), A asserts p. Given the Maxim of Quality (Grice 1989), A conveys that they believe p. According to Stalnaker’s (1978) theory of assertion and common ground, A also intends their interlocutor B to accept p as true, and to update the common ground with p. The common ground is a set of propositions representing the mutual beliefs of the interlocutors. The context set c is the conjunction of these propositions, the set of all worlds compatible with all of the interlocutors’ mutual beliefs. If B were to accept A’s assertion, the common ground would be updated with p. The resulting context set c would then only contain p-worlds.

But this is not what happens in (9). Instead, B responds to A by asking ?p (Does Dinah like Ivy?). Crucially, there are general constraints on asking questions: both Roberts (2012, p. 14) and Büring (2003, p. 541) propose what I call the interrogativity principle: Footnote 6

-

(10)

Interrogativity principle:

-

(10)

Ask a question Q only if the context set c does not entail a complete answer to Q.

p is a complete answer to ?p, so if p were mutually believed, c would entail p and ?p would be infelicitous by (10). Thus, by asking ?p, B signals that c does not entail p, that p is not mutually believed. Since it is mutually believed that A believes p as a result of A’s assertion, the reason that c does not entail p must be that B does not believe it, ¬□p.Footnote 7

So far we are only part way to our goal, since the bias inference in (9), □¬p, is stronger than ¬□p. This gap can be bridged using an idea familiar from the quantity implicature literature that derives strong or secondary implicatures from weak or primary implicatures (Sauerland 2005; Fox 2007; Geurts 2010; also used in explanations of neg-raising in Bartsch 1973, Horn 1989). The inference ¬□p is strengthened to □¬p only when the context supports the assumption that B is opinionated about p, which is to say that they either believe p or ¬p, i.e., □p∨□¬p. But if B either believes p or ¬p, and we have concluded that it is not the case that B believes p, it follows that they believe ¬p. That is, the combination of ¬□p and □p∨□¬p entails the bias inference □¬p.Footnote 8

This account makes several predictions that are explored in the remainder of this section.

3.2 PFQ bias correlates with speaker opinionatedness

Given the role of opinionatedness in the derivation, the more likely that a speaker is opinionated about p in a context, the more likely we are to infer that their PFQ conveys a bias. For example, if we know that B in (9) is very close with both Dinah and Ivy, then it is highly likely that B has an opinion about whether Dinah likes Ivy, and so we feel that the speaker’s PFQ gives rise to the bias inference □¬p. On the other hand, if we know that B is not close with Dinah and Ivy, then it is not likely that B has an opinion about whether Dinah likes Ivy, and it is plausible to imagine B using the PFQ in (9) without conveying the bias inference, but instead conveying something weaker, like surprise or lack of awareness.Footnote 9 These two different inferences can be brought out by possible continuations of (9). In the first context, B can follow the PFQ with “I don’t think she does.” In the second context, B can follow the PFQ with “I didn’t know that.”

Here is another example demonstrating a lack of opinion leading to a weaker, surprise/unawareness inference:

-

(11)

A is telling B about a new club she has joined. Both know that B knows little about it.

A: And Jill is a member too.

B: IS she? That’s nice!

\(\not\leadsto\) B believed that Jill isn’t a member.

In (11), A asserts p, but B is not opinionated about p, so strong speaker bias is not derived.

3.3 PFQ bias depends on whether an interlocutor conveys commitment to the proposition questioned

Consider again (8), in which the PFQ conveys no bias, repeated here:

-

(8)

B wants to know whether Jill will be at a meeting for members. But B has no clue whether Jill is a member.

B: Will Jill be at the meeting?

A: If she’s a member, she will.

B: IS she a member?

\(\not\leadsto\) B believed she isn’t a member

This context is lacking two crucial conditions for the bias derivation laid out above. The first is that no one expresses a belief in the propositional prejacent of the question, p. A’s mention of p that licenses B’s use of polarity focus is embedded in the protasis of a conditional. The second is that B lacks an opinion about p. As a result, the bias derivation outlined above cannot get off the ground, and we do not infer that B is biased. A similar example is demonstrated in Goodhue (2018a, p. 100, ex. (24)).

This explains why bias arises from PFQs in some contexts and not others. It is just a coincidence that many contexts that license polarity focus also feature an interlocutor asserting p plus an opinionated speaker.

3.4 Bias without polarity focus

Another prediction of this theory is that, if we can find a context that provides all of the necessary inputs for a bias derivation but that does not license polarity focus, then bias should still be derived. This is indeed what we find.

-

(12)

A and B are planning a potluck.

A: Mark made a salad, and Jane baked a pie.

B: Wait. Is Jane coming?

⇝ B believed that Jane isn’t coming.

In (12), B can take A’s utterance to imply that Jane is coming (p). If the context set c entailed p, then by (10) B shouldn’t be able to ask ?p. So since B does, B conveys that c does not entail p, and this is because ¬□p. Finally, if B is taken to be opinionated, we derive the bias implicature, □¬p.Footnote 10 Despite this speaker bias, B’s polar question in (12) would be severely degraded with polarity focus because the proper antecedent for a prominence shift is absent. Instead, prominence appears most naturally on Jane, though it could also land on coming (cf. biased questions in which prominence lands on the verb in Romero and Han 2004; Frana and Rawlins 2019). So speaker bias can arise even in the absence of polarity focus, as predicted.Footnote 11

3.5 Bias for the propositional prejacent of the question

In all examples we have seen so far, the polarity of the bias is always opposite from that of the question, i.e., the bias is always against the propositional prejacent of the question. This is one of the common features between HNQs and PFQs identified by Romero and Han (2004). Insofar as we think of HNQs as negative, this generalization is correct for HNQs: HNQs always convey a bias toward the propositional prejacent embedded under high negation. However, (13) shows that not all biased polar questions convey a bias that opposes the polarity of the question.

-

(13)

Jane is not present:

A: Everyone’s here, let’s go!

B: Wait. Is Jane coming?

⇝ B believed that Jane is coming.

In (13), Jane’s absence plus A’s assertion implies that A believes that Jane is not coming (¬p). Like for (12), if c entailed ¬p, then by (10), B shouldn’t be able to ask ?p. So since B does, B conveys that c does not entail ¬p, and this is because ¬□¬p. Finally, if B is taken to be opinionated, we derive the bias implicature, □p. Like for (12), polarity focus would be infelicitous in (13) because the proper antecedent is missing, but the bias can be derived independently, as predicted.

Interestingly, the polarity of the bias in (13) is identical to the polarity of the polar question. (13) shows that question bias does not have to oppose the polarity of the question. This is because the polarity of the bias inference is conditioned by the context—specifically, the bias necessarily opposes the proposition q that was previously implied and is now being questioned. Regardless of whether the question has the same polarity as the previous implication q or the opposite, the bias derived will always oppose that implication. In (13), the implication q is ¬p, that Jane is not coming, and so the bias is for p.

Despite (13), question bias almost always opposes the polarity of the question. Here’s why: the biased question is frequently questioning a proposition for which there is salient evidence in the context, especially in the form of an assertion of that proposition. When this is the case, the question is subject to an evidential condition (see Büring and Gunlogson 2000; Sudo 2013; Trinh 2014; Roelofsen and Farkas 2015; Domaneschi et al. 2017; Frana and Rawlins 2019):Footnote 12

-

(14)

Evidential condition on the polarity of polar questions

-

a.

Positive polar questions with propositional content p (PPQs) are incompatible with compelling contextual evidence for ¬p (= compatible with evidence for p, or no evidence either way)

-

b.

Low negation questions with propositional content ¬p (LNQs) require compelling contextual evidence for ¬p

-

a.

This evidential condition forces the question to have the same polarity as the proposition being questioned. Since the polarity of the bias opposes the polarity of the proposition questioned, the polarity of the bias opposes the polarity of the question asked. (13) is a rare example in which the evidence for the proposition being questioned is implicit enough to allow the evidential condition in (14) to be obviated. Note that the question could have been phrased negatively as “Is Jane not coming?”, and the bias conveyed would have been the same.

3.6 Comparison to verum accounts

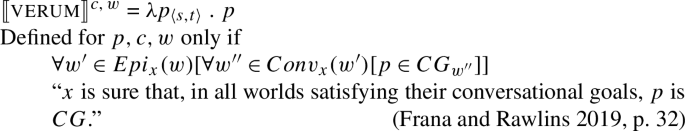

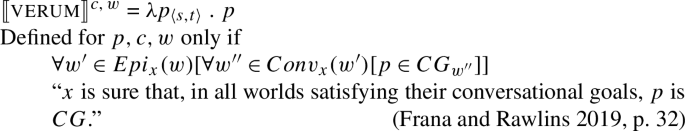

In recent work, Frana and Rawlins (2019) posit a verum operator with roughly the semantics of Romero and Han’s (2004, p. 627) verum, except that, building on an innovation in Romero (2015), verum makes a presuppositional, rather than at-issue, contribution:

-

(15)

x is fixed to a contextually provided individual by the illocutionary force of the utterance (x = speaker in assertions, x = addressee in questions). Frana and Rawlins follow Romero and Han in assuming that utterances containing verum are meta-conversational, and so their distribution is restricted by a principle of economy, which says not to use a meta-conversational move unless necessary to resolve a Quality dilemma. The relevant Quality dilemma here is an epistemic conflict in which the speaker has a preexisting bias that the context (especially the addressee) contradicts.

With these ingredients, Frana and Rawlins propose the following updated verum account of bias in PFQs: A asserts p, and then B chooses to ask a question ?p that contains verum instead of a simpler question without it. Given the principle of economy, B must be facing an epistemic conflict. The verum operator presupposes that A has indicated certainty for adding p to the CG, so the epistemic conflict must be caused by B being biased for ¬p. This matches intuitions for (9).

What this bias derivation shares with the one I developed above is that it depends on conflict between an interlocutor’s previous assertion (or implication) and the speaker’s choice to then use a certain kind of question, leading to the inference that the speaker’s bias must oppose the interlocutor’s commitment. However, whereas my account depends on an independently motivated pragmatics of question-asking relative to the common ground, Frana and Rawlins’s (2019) (and also Romero and Han’s 2004) depends on a principle of economy that is tailor-made for the verum view of biased questions, and so is less parsimonious.

My account also has broader empirical coverage than verum operator accounts (including Romero and Han 2004; Frana and Rawlins 2019; Gutzmann et al. 2020). First, my account explains why bias is present in some PFQs like (2) and (9), and absent in other PFQs like (8) and (11). verum accounts on the other hand have to stipulate that verum is present in biased PFQs and absent in unbiased PFQs.

A second challenge is that the verum operator is assumed to only be introduced by a few grammatical markers in English—high negation, the adverb really, and prosodic prominence on auxiliaries or verbs—but (12) and (13) lack such markers (prominence naturally lands on the subject Jane), yet they convey the kind of speaker bias typical of PFQs. While my account provides a unified explanation of these examples and PFQs, verum accounts need to either say that this bias is explained by an auxiliary theory distinct from verum, or that verum operators are present in sentences where they have been hitherto unexpected. The former route is unparsimonious, especially when compared to the simpler unified account I have proposed. The latter route makes two incorrect predictions for same polarity bias like in (13). First, given the semantics in (15), if verum were present in (13)B, the predicted presupposition would be that A is sure that, in all worlds satisfying A’s conversational goals, that Jane is coming is CG. But if A is sure about anything related to Jane in (13), it’s that Jane is not coming. Second, given this presupposition, B would be predicted to have a negative bias. But B’s bias is positive in (13).

Gutzmann et al. (2020) propose a distinct verum account that is subject to most of the challenges above, and also faces another challenge. For them, verum(p) means that the speaker wants to prevent the QUD from being downdated (=answered) with ¬p. They note that if verum operates on the question prejacent, then their semantics predicts exactly the opposite bias from what is actually observed. Their solution (p. 40ff.) is for verum to operate on the true answer. Thus, if the speaker thinks p is true, Gutzmann et al. predict that they want to prevent the QUD from being downdated with ¬p, while if the speaker thinks ¬p is true, they predict the speaker wants to prevent the QUD from being downdated with p. These predictions are in line with the intuitions. The problem is that this account doesn’t derive the bias—it assumes the bias at the beginning by stipulating what the true answer to the question is.

Despite the challenges I have raised for verum accounts, I suggest in Sect. 8 that my account of HNQ bias in Sect. 7 could be combined with such operators. What I have objected to here is the unification of PFQ bias and HNQ bias, and the application of verum to PFQs.Footnote 13 In Sect. 4, I further object to the view that verum gives rise to a scope ambiguity with negation in HNQs, and in Sect. 5, I raise challenges for the falsum view of HNQs.

3.7 Bias in really-questions

Returning to the reviewer’s question about how really fits into the picture, consider the really-Q in (16), which produces roughly the same bias as the PFQ in (9).

-

(16)

A: Dinah likes Ivy.

B: Does Dinah really like Ivy?

⇝ B believed that Dinah does not like Ivy

The semantics for verum that inspired (15) was initially proposed by Romero and Han (2004, p. 624ff.) for really. Suppose then that really does indeed denote something like (15). In that case, the general pragmatic derivation of bias I have proposed will predict bias to arise from a really-Q as well, without claiming that the move is meta-conversational or subject to a principle of economy. Just by virtue of raising the question ?p while presupposing the addressee’s commitment to add p to the CG, my account in Sect. 3.1 predicts the bias in (16) to arise.Footnote 14 Moreover, it does so while avoiding a unification of the empirical phenomena of really-Qs, PFQs, and HNQs. I see this as a welcome result, given the empirical asymmetries between them pointed out in Sect. 2.2.

3.8 Section conclusion

We now have a partial explanation for why biased questions convey the biases that they do: for PFQs, the bias conveyed does not depend directly on unique aspects of their prosody or syntax. Rather, the speaker bias of these questions is derived entirely via independent pragmatic principles. Semantically and syntactically (F-marker notwithstanding), PFQs are no different from polar questions that lack polarity focus. The account proposed works with any standard semantics for polar questions and accurately predicts that questions that lack polarity focus can also convey bias.

I turn now to HNQs and their invariable bias. Unlike for PFQs, I propose that HNQs have a syntax and semantics all their own that plays a direct role in the speaker bias they convey.

4 The prejacent of the HNQ is not negated

Given the correspondence between negation, preposing and bias in HNQs, the goal is to understand where negation is in the structure of HNQs and what role it plays in interpretation. In declarative sentences, negation reverses truth values. But since polar questions don’t have truth values, determining the position and effect of negation will require other diagnostics.

4.1 Polarity items are a poor diagnostic of negation in polar questions

Ladd (1981) claims that HNQs are ambiguous between an inner negation reading in which propositional, sentential negation is present, and an outer negation reading in which negation “is somehow outside the proposition…” Another way he states the ambiguity is that (17a) questions p, while (17b) questions ¬p. Ladd uses the polarity items either and too to bring out the two supposed readings:

-

(17)

-

a.

Isn’t Jane coming too? outer negation

-

b.

Isn’t Jane coming either? inner negation

-

a.

Many speakers find (17b) unacceptable; more on that shortly. Whatever intuitive contrast there is between (17a) and (17b)), it’s not immediately clear whether it’s due to the scope of negation or the polarity items. Claims of ambiguity between outer and inner negation are almost always demonstrated via examples with polarity items. (AnderBois 2011, 2019 also makes this observation.) For example, Sudo (2013) demonstrates inner and outer readings using too and either, and claims that the inner reading requires contextual evidence for ¬p, while the outer reading does not (this claim is discussed further in Sect. 4.3). Footnote 15 However, Rullmann (2003) observes that either itself imposes a licensing condition that requires evidence for the falsity of either’s complement clause. Perhaps either is not bringing out an ambiguity in HNQs, but having an effect itself (again, a point AnderBois 2019 also raises). This issue cannot be settled until we have a complete understanding of either, especially its licensing condition. Rullmann (2003, Sect. 3.3) points out several challenges for his own proposed licensing condition.

Moreover, many native speakers of American English, including AnderBois (2019), myself, and all other native speakers of American English I have consulted, find HNQs with either, such as (17b), to be either infelicitous or at least severely degraded. This fact is demonstrated experimentally by Hartung (2006) and Sailor (2013). Footnote 16 At the same time, informal discussion with a small number of British English speakers suggests that HNQs with either such as (17b) are acceptable in at least some dialects. Furthermore, Frana and Rawlins (2019, p. 22, fn. 18) report that the English speakers they have consulted fall into two dialect groups by whether they have the inner/outer negation ambiguity in HNQs, and that this is responsible for the conflicting judgments for HNQs with either. However, since the data Frana and Rawlins use to establish the inner/outer ambiguity involves polarity items, and since my discussion with British English speakers was restricted to HNQs with either, more work is needed on this variation to determine if it is due to the interpretation of HNQs or the polarity items themselves.

So, we must search for evidence beyond polarity items. Romero et al. (2017) claim to demonstrate that prosody exhibits the inner/outer ambiguity in English (see also Arnhold et al. 2021). The production experiment is designed to capture the prosody speakers produce when their HNQ-p is double-checking p or ¬p. This is done by producing contexts in which the character that participants play has a p bias, but is confronted with conflicting evidence for ¬p, and then the participant is explicitly told either that they are still convinced they are right about p and want to check their p assumption, or that they are now becoming convinced that ¬p and want to check their ¬p assumption. Participants were more likely to produce a shallower final rising intonation in the checking-p condition, while they were more likely to produce a steeper final rise in the checking-¬p condition. I believe the most straightforward explanation for this result has nothing to do with a potential inner/outer negation ambiguity: steepness of polar question intonation is independently known to signal increased emotional activation, which correlates with surprise (Gussenhoven 2004; Bänziger and Scherer 2005; Westera 2017; Goodhue 2021). The character participants played in the checking-¬p condition is surprised because they are now becoming convinced that their original p-bias was mistaken. In the checking-p condition, there is less to be surprised about—they previously believed p and they still do. Footnote 17

To get a handle on negation in HNQs, a larger set of diagnostics is needed. In the following, I use presupposition and conventional implicature triggers, expressions that are sensitive to aspect, and polar particle responses to test for negation.

4.2 Diagnostics for negation in HNQs

4.2.1 Projecting content

Not-at-issue content projects out of questions. Again presupposes that the proposition denoted by its complement has happened before (von Stechow 1996; Pedersen 2015). For example:

-

(18)

Did Lou come to class again?

presupposes: Lou has come to class before

If again’s complement contains negation, then negation can be part of the presupposition. (Negation can also be absent from the presupposition on another reading.) For example:

-

(19)

Did Lou not come to class again?

presupposes: Lou did not come to class at least once before.

Interestingly, the presupposition projecting from the HNQ in (20) cannot include negation, unlike (19). Instead it patterns with (18).

-

(20)

Didn’t Lou come to class again?

presupposes: Lou has come to class before.

Relative to a context, the asymmetry pops out via felicity judgments:

-

(21)

B knows that A is worried because A’s student Lou did not do their first assignment. The second assignment was due today. A gets home from teaching and says, “I don’t know what to do about Lou.” B replies:

-

a.

B: # Did they do the assignment again?

-

b.

B: Did they not do the assignment again?

-

c.

B: # Didn’t they do the assignment again?

-

a.

What these examples show is that the presuppositional operator again can scope over a propositional negation in LNQs but not in HNQs. In Goodhue (2018a, pp. 106-107), I demonstrate similar effects with also.

As-parentheticals provide another test. On one reading, the content of the claim in the as-parenthetical in (22) can include negation. (It can exclude it on another reading.)

-

(22)

Ames did not steal the documents, as the senators claimed.

implicates: The senators claimed that Ames did not steal the documents

(Potts 2002, p. 625)

Potts shows that the complement of the as-parenthetical projects through various presupposition holes, including questions:

-

(23)

Is it said that, as Joan claims, you are an excellent theremin player?

implicates: Joan claims that you are an excellent theremin player

(Potts 2002, p. 652)

As above, we can check to see whether the content that projects out of LNQs and HNQs can contain negation:

-

(24)

Did Zoe not win, as Joy predicted?

implicates: Joy predicted that Zoe did not win

-

(25)

Didn’t Zoe win, as Joy predicted?

implicates: Joy predicted that Zoe won

Again, we find that the projected content can contain negation in an LNQ, but not an HNQ. These facts suggest that again and as-parentheticals cannot scope over high negation.

4.2.2 Negation sensitivity

Until- and for-adverbials only combine with clauses that have durative rather than punctual aspect:

-

(26)

Punctual aspect:

-

a.

# Liv discovered the thief until 9.

-

b.

# The ball hit the ground for two minutes.

-

a.

Negating a verb with punctual aspect creates durative aspect:

-

(27)

Durative aspect:

-

a.

Liv didn’t discover the thief until 9.

-

b.

The ball didn’t hit the ground for two minutes.

-

a.

Turning to negative questions, LNQs license until- and for-adverbials:

-

(28)

-

a.

Did Liv not discover the thief until 9?

-

b.

Did the ball not hit the ground for two minutes?

-

a.

However, HNQs do not:

-

(29)

-

a.

#Didn’t Liv discover the thief until 9?

-

b.

# Didn’t the ball hit the ground for two minutes?

-

a.

These facts again suggest that certain expressions, until- and for-adverbials, cannot scope above high negation.Footnote 18,Footnote 19

4.2.3 Responses to negative sentences

While yes/no responses to PPQs as in (30) convey unambiguous answers, they are interchangeable in response to LNQs, as in (31) (Krifka 2013, Roelofsen and Farkas 2015, Goodhue and Wagner 2018).

-

(30)

A: Is Jane here?

-

a.

B: Yes (can only mean She is here)

-

b.

B: No (can only mean She is not here)

-

a.

-

(31)

A: Is Jane not here?

-

a.

B: Yes (can mean either She is here or She is not here)

-

b.

B: No (can mean either She is here or She is not here)

-

a.

Accounts of these facts differ in interesting ways, however all agree that a crucial component of the explanation for the contrast between (30) and (31) is that the sentence that B responds to in (31) is negative, i.e., it contains propositional negation, while that in (30) is not.

Responses to HNQs pattern with (30) rather than (31):

-

(32)

A: Isn’t Jane here?

-

a.

B: Yes (can only mean She is here)

-

b.

B: No (can only mean She is not here)

-

a.

Whatever the negative morpheme in the HNQ is doing, it clearly is not contributing the kind of negation necessary to condition the interchangeable behavior of yes and no as seen in (31).

Further evidence along similar lines is produced based on an example from Grimshaw (1979, p. 294).

-

(33)

A: Is Jane here?

B: It’s possible. (can only mean It’s possible Jane is here)

The null complement clause of B’s response has to have the content p, not ¬p. Compare this to (34):

-

(34)

A: Is Jane not here?

B: It’s possible. (can only mean It’s possible Jane is not here)

Now the null complement clause has to have the content ¬p, not p.

Responses to HNQs again pattern with PPQs, not LNQs, suggesting that HNQs do not contribute a sentential negation.

-

(35)

A: Isn’t Jane here?

B: It’s possible. (can only mean It’s possible Jane is here)

4.3 Even-HNQs

Despite the preceding evidence, perhaps a well-placed NPI can force an inner reading, which in combination with one of the tests from above will reveal a sentential negation. For example, stressed NPIs, and even plus low scalar items and minimizers, have been observed to convey negative bias in polar questions (Lahiri 1998; Guerzoni 2004). Given this, Jeong (2020) explores experimentally the kinds of biases that arise when HNQs contain such items (which I abbreviate collectively as even-HNQs). The experimental results suggest that even-HNQs simultaneously convey positive and negative speaker bias and, most relevantly here, that they also require contextual evidence for the negative answer, such as that required by LNQs in (14b). Jeong argues that high negation must be the culprit, since the results also suggest that positive questions with stressed NPIs or even plus low scalar items and minimizers do not require contextual evidence for the negative answer. She further assumes, following Sudo (2013), that if HNQs have an inner negation reading, this reading will require contextual evidence for the negative answer. Thus, Jeong argues that we need a theory of HNQs that accounts for Ladd’s inner vs. outer ambiguity, and that even-HNQs necessarily have a lower, inner negation that is responsible for the negative evidential bias. To achieve this, she assumes Frana and Rawlins’s (2019) verum/falsum account of HNQs.Footnote 20

If Jeong is right, then the tests from Sect. 4.2 should reveal the presence of inner negation in even-HNQs. But they do not. In (36), the presuppositions triggered by again result in the PPQ and the HNQ patterning together as unacceptable in the context, while the LNQ is just fine.

-

(36)

Les is struggling in logic class. On the first assignment, he failed to correctly prove any of the theorems. TA1 has just finished grading his second assignment.

TA1: Uh oh, Les had trouble on this one too.

-

a.

TA2: Did he not prove ANYTHING again?

(presupposes: Les didn’t prove anything before.)

-

b.

TA2: # Did he prove ANYTHING again?

-

c.

TA2: # Didn’t he prove ANYTHING again?

-

a.

To see that the pattern in (36) holds with even plus a low scalar item, exchange “prove ANYTHING” with “even prove a single theorem”.

(37) demonstrates the same pattern with the minimizer lift a finger.

-

(37)

Liz’s laziness is famous among her friends. Yesterday, her roommates cleaned the whole apartment, and Liz just sat on the couch, not helping at all. Tonight, her roommates made a fancy four-course meal and invited all their friends over to eat it.

Friend: This came out amazing, nice work!

Roommate (scowling at Liz): Yeah, no thanks to Liz.

-

a.

Friend: Did she not (even) lift a finger again?

(presupposes: Liz didn’t (even) lift a finger before.)

-

b.

Friend: # Did she (even) lift a finger again?

-

c.

Friend: # Didn’t she (even) lift a finger again?

-

a.

(38) demonstrates similar results using the negation sensitive operator until.

-

(38)

-

a.

# Didn’t Les even prove a single theorem until 9?

-

b.

Did Les not even prove a single theorem until 9?

-

a.

If the even-HNQs in (36)-(38) contained a lower, inner negation, as Jeong (2020) claims, then they should be just as felicitous as their LNQ counterparts, but they are not. The experimental results in Jeong (2020) shed new light on the complex interactions of bias in polar questions. But the theoretical conclusion that even-HNQs contain an inner negation is contradicted by the evidence here.

4.4 Section conclusion

The various data points in this section demonstrate that HNQs pattern with PPQs to the exclusion of LNQs. What this boils down to is that LNQs contain a propositional negation within the prejacent of the question, while HNQs—like PPQs—do not, contrary to what some authors have previously claimed (e.g., Ladd 1981; Büring and Gunlogson 2000; Van Rooy and Šafářová 2003; Romero and Han 2004; Trinh 2014; Romero 2015; Jeong 2020; see also Frana and Rawlins 2019 on one dialect).

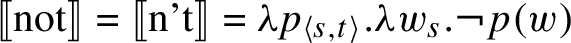

5 Against analyzing high negation as a discourse particle

One way to capture the bias generalization in (6) and the data from Sect. 4 is to claim that high negation does not contribute negation, but instead a discourse particle with a non-at-issue bias meaning:

-

(39)

(39) adds speaker bias, and passes the proposition p up the structure to a Q-morpheme, which produces the denotation of a polar question. The non-at-issue content could be elaborated in various ways. For Hartung (2009), for example, German high negation adds p to the speaker’s commitments in a Farkas and Bruce (2010) style formal pragmatics. For Northrup (2014), HNQs commit the speaker to p on the basis of prior weak evidence. For Taniguchi (2017), high negation removes p from the common ground and puts it in the speaker’s discourse commitments set.

While such approaches are formally precise, it is not clear that they provide insight into the phenomenon beyond empirical generalizations of it. For example, on these accounts, why is the bias for p and not ¬p? If high negation were a discourse particle that directly conveys bias, then there would be no reason in principle for the bias to be for the propositional prejacent of HNQ-p rather than against it. After all, the purported bias particle is morphologically linked to negation. It would be possible to imagine that it developed out of negative questions that convey evidential bias for ¬p (as LNQs do), so that when it turned into a discourse particle, the bias would be for ¬p instead of p. But no such language is known to exist. Another question is, why does the combination of negation and preposing trigger bias crosslinguistically? Discourse particle theories have little to say.

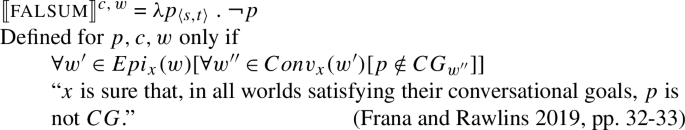

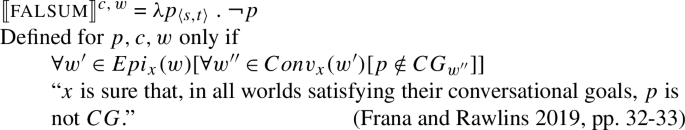

Now consider the illocutionary negation, falsum (Repp 2013):

-

(40)

Romero (2015) and Frana and Rawlins (2019) analyze some HNQs as having the LF: [ Q [ falsum [ p ] ]. Both claim that falsum doesn’t license NPIs because it is illocutionary denial rather than regular negation. While I agree that illocutionary denials won’t license NPIs, it isn’t completely clear why the operator in (40) wouldn’t license NPIs—after all, it introduces a standard logical negation on the at-issue dimension with no intervening operator, which should produce the right licensing environment.Footnote 21 More generally, the at-issue negation in (40) leaves the findings of Sect. 4 unexplained.

Another challenge for the falsum account of HNQs is relative to “suggestion” contexts, or as I prefer to call them non-conflict contexts:Footnote 22

-

(41)

A tells B that she is going to an Alabama Shakes concert tonight. B has previously heard that the opening act will be The Moon and You.

B: Oh yeah, I heard about that show. Aren’t The Moon and You opening?

-

(42)

Dialogue between two editors of a journal in 1900:

A: I’d like to send this paper out to a senior reviewer, but I’d prefer somebody new.

B: Hasn’t Frege not reviewed for us? He’d be a good one.

(Romero and Han 2004, p. 619)

The issue is that the HNQs in (41) and (42) are predicted by (40) to presuppose that the addressee A is sure that, in all worlds satisfying A’s conversational goals, the following propositions respectively are not CG: that The Moon and You are opening, and that Frege has not reviewed for us. But these predicted presuppositions are not met. It is true that, in each of these contexts, each of these propositions are not CG at the time the HNQ is uttered. But these presuppositions do not require these propositions not to be CG; they require them not to be CG according to the addressee’s conversational goals in the addressee’s epistemically accessible worlds. But nothing about these contexts implies this. For all we know, A’s conversational goals in A’s epistemically accessible worlds could be such that each of these propositions are CG. Thus, falsum’s presupposition is not met in non-conflict contexts for HNQs, and so (40) incorrectly predicts HNQs to be infelicitous in such contexts (pace Frana and Rawlins’s 2019, p. 35 discussion).

A reviewer argues that Frana and Rawlins can account for such examples by assuming that these presuppositions are “accommodatable as long as there is no public evidence against them”. For example, A’s failure to mention that The Moon and You is opening in (41) in combination with the assumed relevance of that fact could be taken by B to mean that A “is acting as if The Moon and You is not opening”. However, there is some evidence against this argument. To see it, consider that Trinh (2014) makes a very similar argument: Trinh claims that HNQs require compelling contextual evidence for ¬p, exactly like LNQs do, as laid out in (14b). When confronted with examples like (41) in which there is no ¬p evidence, Trinh argues that ¬p evidence can be accommodated as a result of A’s failure to mention p. If either of these very similar arguments were correct, then the accommodatable evidence that (A thinks that) ¬p should satisfy (14b), making LNQs felicitous in non-conflict contexts. The problem is that LNQs are infelicitous in such contexts. For example, the LNQ “Are The Moon and You not opening?” is infelicitous in the context of (41). This speaks against the view that B is accommodating that A thinks ¬p is true in examples like (41), which in turn calls into question the falsum analysis of HNQs and Trinh’s view that HNQs require negative contextual evidence.

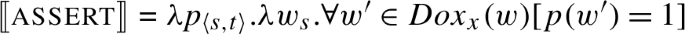

6 Speech act operators and unbalanced partitions

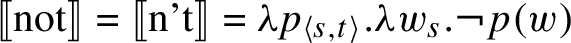

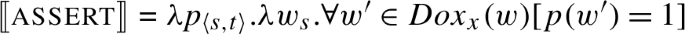

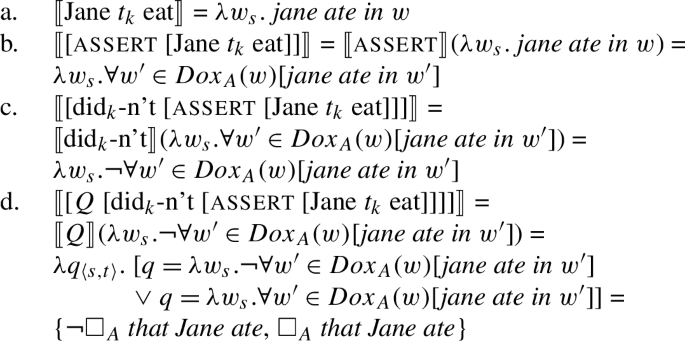

Based on the evidence in Sect. 4, I take it for granted that high negation is “somehow outside the proposition” (Ladd 1981) in all HNQs. To put flesh on the bones of Ladd’s idea, I adopt the view from prior work that high negation scopes over a high operator (e.g. verum in Romero and Han 2004, ASSERT in Krifka 2017). Here I treat it as a doxastic assert operator with the denotation in (43).Footnote 23 The main theoretical innovation relative to HNQs in this paper is not in the treatment of assert, but in the pragmatic derivation of speaker bias in Sect. 7. Given this, I use (43) because it simplifies exposition in Sect. 7. In Sect. 8, I briefly explore the prospects for moving to a more sophisticated syntax-semantics than assumed in this section (see also Goodhue 2022b).

-

(43)

\(Dox_{x}(w)\) is the set of worlds compatible with x’s beliefs in w. x is a free variable for individuals whose value is contextually determined. Usually x is the speaker, but when assert appears in an HNQ, x is the addressee.Footnote 24 In the following, I frequently abbreviate x’s doxastic necessity with “\(\square_{x}\)”.

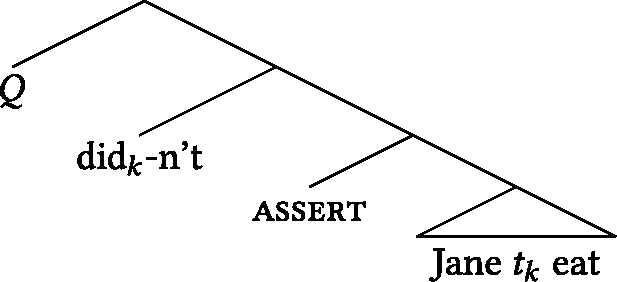

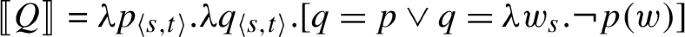

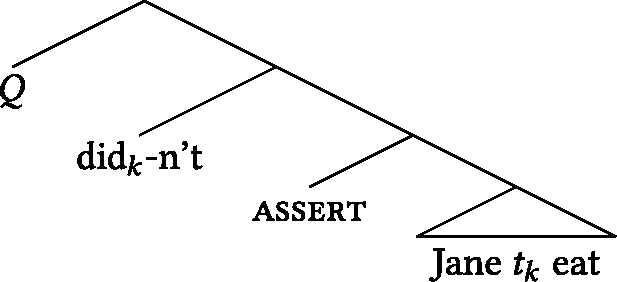

Here is the structure I assume for an HNQ like “Didn’t Jane eat?”:

-

(44)

By scoping over assert, high negation signals the operator’s presence in the HNQ. Otherwise, I assume that assert is not present in questions (cf. Meyer’s, 2013, p. 42, assumption that matrix K only appears in assertively used sentences).Footnote 25

An advantage of analyzing high negation as scoping over assert is that it explains the facts from Sect. 4 if (i) the relevant phrases cannot scope above the speech act layer and (ii) polarity particle responses are only sensitive to discourse referents introduced by constituents below the speech act layer, as argued by Krifka (2013, 2017).

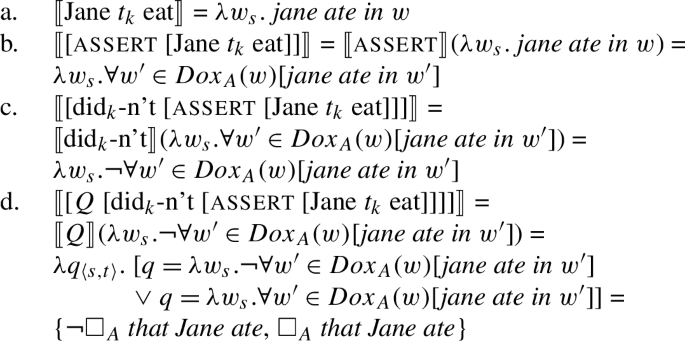

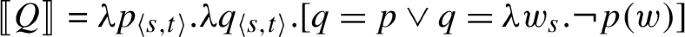

Following Romero and Han (2004) and Dayal (2016), I assume the denotation for polar interrogative Q in (45), which, when combined with a proposition, provides the denotation for polar questions.

-

(45)

I assume that the auxiliary did is vacuous, and that not/n’t is defined for propositions

-

(46)

With these lexical denotations in hand, the interpretation for (44) is demonstrated in (47).

-

(47)

The denotation for HNQs produced in (47) is similar to Romero and Han’s proposed interpretation for their outer negation polar questions in that it yields what they call an unbalanced partition. Whereas a positive polar question presents a partition that is balanced between p and ¬p, an HNQ presents an unbalanced possibility space, partitioned between doxastic necessity for p (\(\square_{A}~ p\)), and a lack of doxastic necessity for p (\(\neg\square_{A}~ p\)) (cf. a similar result in Krifka 2017, who refers to the negated cell \(\neg\square_{A}~ p\) as one in which the addressee refrains from committing to p). I follow Romero and Han in taking \(\neg\square_{A}~ p\) to cover any other degree of belief in p besides belief in p itself. \(\neg\square_{A}~ p\) is a weak claim in that it includes a wide range of situations, which can be further divided into two sorts (Geurts 2010; Meyer 2013).

-

(1)

Lack of belief either way, neither p, nor ¬p (\(\neg\square_{A}~ p \wedge \neg\square_{A}~\neg p\))

-

(2)

Belief that ¬p (\(\square_{A}~\neg p\))

Despite the fact that Romero and Han and Krifka both posit such unbalanced partitions, neither derives the speaker bias associated with HNQs from the way in which the partition is unbalanced. The innovation in Sect. 7 is that I derive the bias of HNQs from the way in which the possibility space is unbalanced, with the speaker expressing bias for the more precise cell, □p.

7 Explanation of speaker bias in HNQs

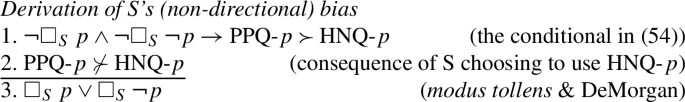

I argue for a novel derivation of speaker bias in HNQs as a conversational implicature.Footnote 26 The reasoning runs as follows. The speaker S has asked an HNQ with propositional prejacent p (HNQ-p). If S were ignorant of whether or not p is true, S could have asked an alternative question that would have been better suited to remedy that ignorance, namely the positive polar question (PPQ). Since S did not do so, it must be the case that S is not ignorant of whether or not p—that is, S is biased or opinionated about whether p or ¬p. But which way is S biased, for p or for ¬p? I show that the direction in which HNQ-p is unbalanced settles this: S is biased for p.

This implicature derivation bears some similarities to more familiar cases of quantity implicature, but differs in several ways, especially in the strength relationship between competing alternatives.

Four steps are needed to flesh out this story. First, PPQs need to be shown to be alternatives to HNQs (Sect. 7.1). Second, definitions of bias and ignorance need to be given (Sect. 7.2). Third, we need an argument that, in the case of ignorance, the PPQ is more useful than the HNQ because it is more informative (Sect. 7.3). Fourth, we need an argument that the direction of unbalance is only compatible with bias for the propositional prejacent of the HNQ (Sect. 7.4).

7.1 Alternatives

I claim that PPQs like (48a) are alternatives of HNQs like (48b).

-

(48)

-

a.

Did Jane eat?

-

b.

Didn’t Jane eat?

-

a.

Building on Rudin’s (2018, p. 58ff.) analysis of alternatives for discourse moves, I assume that a question counts as an alternative to another only if they have the same sentence radical and therefore the same propositional prejacent. In other words, the questions need to be about the same proposition. (48a) and (48b) share the same propositional prejacent, that Jane ate.

Let’s briefly compare this approach to one using Katzir’s (2007) algorithm, which identifies alternatives to a structure ϕ by making deletions, contractions and replacements of constituents in ϕ. This algorithm also predicts (48a) to be a valid alternative to (48b). However, Katzir’s algorithm can derive alternatives by making changes to the sentence radical and so the propositional prejacent, which results in incorrect predictions. For example, the PPQ in (48a) is also a Katzirian alternative to the questions in (49):

-

(49)

-

a.

Do you believe that Jane ate?

-

b.

Are you sure/certain that Jane ate?

-

a.

However, the questions in (49) do not convey the speaker bias that HNQs are known for.Footnote 27 But the flat-footed denotations of these polar questions are either identical or very similar to the one I have assumed for the HNQ in (48b), namely:

-

(50)

{\(\square_{A}\) that Jane ate, \(\neg\square_{A}\) that Jane ate}

Given this denotational similarity, if the choice to say (48b) instead of (48a) is responsible for conveying speaker bias, as I argue below, then it seems that the choice to say (49a) or (49b) instead of (48a) should also convey an HNQ-like bias, but it does not. The reason that the questions in (49) lack bias is that (48a) has a different prejacent, is about a different proposition, and so is not an alternative of the relevant kind. Thus, there is no competition between the questions in (49) and (48a) in the first place.

Also note, since both questions in (48) are about the proposition that Jane ate, I assume that whenever (48b) is relevant enough to utter, so is (48a). This is somewhat different from standard cases of quantity implicature, such as sentences containing some vs. all where the relevance of the weaker some alternative does not guarantee the relevance of the stronger all alternative. This may explain why the bias implicature of HNQs is not cancellable.

7.2 Bias as belief

Here is the empirical generalization from Sect. 2.1 to be explained:

-

(6)

Speaker bias condition:

An HNQ with propositional content p below the negation (HNQ-p) is felicitous only if the speaker is or was recently biased for p

It is clear from the various examples of HNQs above that being “biased for p” means either believing p, or at least taking p to be highly likely. Either formulation would work for the account developed below. For simplicity, I take bias to be doxastic necessity, which I write as follows using the “\(\square_{x}\)” abbreviation:Footnote 28

-

(51)

Bias:

S is biased for p ⇔ \(\square_{S}~ p\)

I take ignorance to be a lack of belief either way, neither for p, nor ¬p:

-

(52)

Ignorance

S is ignorant of whether p or ¬p ⇔ \(\neg\square_{S}~ p \wedge \neg\square_{S}~\neg p\)

Ignorance includes a wide array of degrees of confidence about p/¬p. S may be leaning toward p, or toward ¬p, or be completely split between the two, or anything else in between. However, this variation is not relevant. What matters is that in none of these states of affairs is S leaning so far one way or the other as to exhibit belief in p or in ¬p—otherwise we would say that S is biased for p/¬p, and the situation would not fall under the definition in (52).

7.3 Why HNQs imply that the speaker is not ignorant of the answer

With definitions for bias and ignorance, and with the assumption that PPQs are alternatives to HNQs in hand, we are ready to show how the two kinds of question relate to one another and thus the implicature that arises via the choice to use the HNQ instead of the PPQ. It will be helpful to briefly rehearse a standard case of quantity implicature for comparison.

Using some and all as abbreviations for alternative sentences containing these determiners, consider the conditional in (53a), restated symbolically in (53b), with ‘≻’ standing for ‘more useful than’:

-

(53)

-

a.

If S believes all, then all is more useful than some.

-

b.

\(\square_{S}~ \textbf{all} \rightarrow \textbf{all} \succ \textbf{some}\)

-

a.

When the purpose of a conversation is to cooperatively share information, stronger expressions are better than weaker ones, as long as the stronger expression is supported by belief. Thus, all is more useful than some, conditional on the antecedent clause of (53) (which is roughly Gricean Quality), because all asymmetrically entails some (Gricean Quantity). When S asserts the weaker some, that implies that all is not more useful than some, which given (53) must mean that S does not believe all. That is, the utterance of some implies that the consequent of (53) is false, and so S implicates that the antecedent of (53) is also false.Footnote 29

Returning to HNQs, I claim that the following conditional, analogous to that in (53), holds:

-

(54)

-

a.

If S is ignorant of whether p or ¬p, then the PPQ with prejacent p is more useful than the HNQ with prejacent p.

-

b.

\(\neg\square_{S}~ p \wedge \neg\square_{S}~\neg p \rightarrow \text{PPQ-}p \succ \text{HNQ-}p\)

-

a.

This conditional sets out ignorance as a sufficient condition on PPQs being more useful than their HNQ counterparts, but not a necessary condition.Footnote 30 More generally, I want to avoid postulating ignorance as a necessary condition on using PPQs because there are empirical counterexamples to it: PPQs can be used in exams and quizzes, they can be used rhetorically, and they can even be used when the speaker is biased for a particular answer, as we saw above with PFQs in Sect. 3.

(54) depends on a fact and two uncontroversial background assumptions. The fact, which I will argue for in a moment, is that HNQs are less informative than their PPQ alternatives. The first background assumption is that the goal of ignorant speakers is to gain information. The second is that utterances that help you achieve your goals are more useful than those that don’t. Putting these together produces the conditional: when S is ignorant about p, their goal is to gain information about it, and since the PPQ is more informative than the HNQ, the PPQ is more useful to S in achieving this goal. Therefore, if S is ignorant about p, the PPQ is more useful than the HNQ.

As a result of (54), S’s choice to use the less informative HNQ triggers a kind of quantity implicature: if the stronger PPQ wasn’t used, it must not have been more useful than the HNQ. By (54), if the PPQ was not more useful than the HNQ, then S must not be ignorant of whether p or ¬p, which is to say S must be biased for either p or ¬p.Footnote 31

The above reasoning depends on the claim that PPQs are more informative than HNQs. To evaluate the relative strength of PPQs and HNQs, I compare the strength of their positive and negative answers. However, because the proposed structure for HNQs includes a doxastic assert operator while that of PPQs does not, this can’t be done directly based on their semantic denotations.

-

(56)

-

(57)

For example, the positive answer to (55) does not entail anything about the positive answer to (56) or vice versa, since any proposition can be true without A believing it, and A can believe any proposition without it being true.

In Sect. 8, I show that Krifka’s (2017) commitment space semantics produces a semantics for PPQs and HNQs that can be directly compared. But sticking with our simpler representations for the moment, the answer sets can be compared if we move to a pragmatic level of description: S’s choice between these competing questions is guided by the information that A’s answers to the questions will produce for S. A’s answers will be given in the form of A’s assertions. (56) already builds the assertive component of A’s answers into the partition. We can compare this to the way that the answers in (55) will transit through A’s assertions:

-

(58)

The set of answers to the PPQ “Did Jane eat?”, as asserted by A:

{\(\square_{A}\) that Jane ate, \(\square_{A}\) ¬that Jane ate}

With this assertive component added in, it is easy to see in what sense the PPQ is more informative than the HNQ. The positive answers in (56) and (57) are identical. But the negative answer in (57) asymmetrically entails that in (56); if A believes that Jane didn’t eat, it entails that it’s not the case that A believes that Jane ate, and not vice versa. Since the PPQ and the HNQ produce identical information for S in their positive answers, and the PPQ produces stronger information than the HNQ in their negative answers, the PPQ is stronger than its HNQ counterpart. Put another way, S learns more from A’s negative answer to the PPQ than the HNQ: A’s negative answer to the PPQ informs S that ¬p. As for the HNQ, since \(\neg\square_{A}~ p\) is compatible with both A’s lack of belief about p (\(\neg\square_{A}~ p \wedge \neg\square_{A}~\neg p\)), as well as A’s belief in ¬p (\(\square_{A}~ \neg p\)), S would only learn that it’s not the case that A believes p, and not why that is.

The above discussion relies on the informal assumption that we are comparing positive answers to positive answers and negative ones to negative ones, despite the fact that answer sets are just unordered sets of propositions. Here is a formal means of comparing such sets and determining that one is stronger than the other:

-

(59)

\(Q_{1}\) is more informative than \(Q_{2}\) iff the following two conditions are satisfied:

-

a.

\(\exists p \in Q_{1}~ [\exists p' \in Q_{2}~ [p \subset p' ] ]\)

-

b.

\(\forall p \in Q_{1}~ [ \neg \exists p' \in Q_{2}~ [p' \subset p ] ]\)

-

a.

(58) says that a question \(Q_{1}\) is more informative than another question \(Q_{2}\) if and only if two conditions are satisfied: first, some proposition in \(Q_{1}\) asymmetrically entails (is a proper subset of) some proposition in \(Q_{2}\), and second, no proposition in \(Q_{2}\) asymmetrically entails (is a proper subset of) any proposition in \(Q_{1}\). According to (58), (57) is more informative than (56).

This is why the PPQ is more useful than the HNQ when S is ignorant, as stated in (54). Given S’s ignorance, their goal is to gain information, and the PPQ is better at helping S achieve that goal than the HNQ, in particular when comparing the negative answers to the two questions. So, if S is ignorant, then they should use the PPQ, not the HNQ. If S uses the HNQ instead, then S must not be ignorant. That is, the speaker is biased for either p or ¬p.

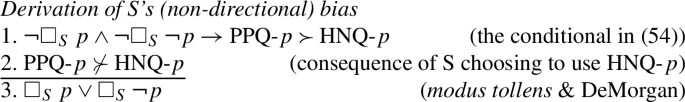

-

(60)

The bias that results in line 3 of (59) is non-directional, that is, S is biased, but nothing said so far tells us whether the bias is for p or ¬p. Empirically, an HNQ with prejacent p always conveys that S is biased for p. So now the direction of bias needs to be explained.

7.4 Explaining the direction of bias

S is either biased for p or for ¬p. Considering each of these in turn will show that the way in which the HNQ partition is unbalanced only fits with a p bias.

Here again is our example:

-

(61)

Suppose S were biased for ¬p, in this case, \(\square_{S}\) that Jane didn’t eat. If A were to choose the positive answer in (56) (\(\square_{A}\) that Jane ate), then it would convey a clear disagreement between S and A. But if A were to choose the negative answer in (56) (\(\neg\square_{A}\) that Jane ate), then it would remain unclear how S’s and A’s beliefs about p relate to one another. This is because the negative answer is consistent with both A’s ignorance (\(\neg\square_{A}\) that Jane ate \(\wedge~ \neg\square_{A}\) that Jane didn’t eat) as well as A’s belief in ¬p (\(\square_{A}\) that Jane didn’t eat). If the latter is the case, it would mean that A and S have an identical belief since they both believe that Jane didn’t eat. But if A is ignorant, it would mean that A and S have conflicting beliefs since A’s ignorance entails that it’s not the case that A believes the very thing that S believes—that Jane didn’t eat.

Now suppose that S were biased for p, in this case, \(\square_{S}\) that Jane ate. In this case, either answer in (56) will help S to determine how A’s beliefs about p relate to S’s own. The positive answer conveys that they have the same belief, while the negative answer conveys that they do not.

Putting this all together, an HNQ with prejacent p conveys that the speaker S is biased because if S had not been biased, then they should have used the alternative PPQ with prejacent p as it would have been more informative. Furthermore, when S uses HNQ-p, we assume that S has a particular bias, that is, that S is biased for p and not for ¬p. This is because of the way that the HNQ partition is unbalanced: if S were biased for ¬p, then the \(\neg\square_{A}~ p\) cell would fail to settle whether A shares S’s bias for ¬p or not. But if S’s bias is for p, then either cell of the partition will usefully settle whether or not A shares S’s bias.

What HNQs are useful for is determining whether an interlocutor shares the speaker’s bias for the propositional prejacent of the question. But there are different sorts of contexts in which an HNQ might be used to do this. In some contexts, there is contextual evidence that challenges p that may or may not come from the interlocutor: (1) and (3) (see also Bledin and Rawlins’s 2020, p. 45, ex. (7) demonstration of HNQs as resistance moves). In others, there is no evidence against p: (41) and (42).

While HNQs convey bias, they are still questions, so they require the speaker to have some reason to ask them as opposed to just asserting p. For example, here’s a variation of (41):

-

(60)

A bought tickets to see an Alabama Shakes concert tonight, and The Moon and You are opening. B asks A what she is up to tonight, and A says: I’m going to the Alabama Shakes concert…

-

a.

?? Aren’t The Moon and You opening?

-

b.

The Moon and You are opening.

-

a.

Despite the fact that A believes the propositional prejacent, the HNQ is infelicitous because A has no reason to ask this question in this context. A is merely informing B about A’s plans, and so the assertion in (60b) is preferred.

At the same time, the fact that HNQs are questions can be exploited to convey politeness in a context in which the speaker is otherwise warranted to just assert p, as in (61).

-

(61)

Earlier, the boss, B, told Jane to work the grill and A to wait on the tables. B however can be forgetful at times, is embarrassed about it, and also has a bad temper.

B: A, what are you doing?

A: I’m getting ready to wait on the tables.

B: Who’s working the grill then?

A: Isn’t Jane working the grill? B: Oh right, Jane is doing it.

Instead of asserting p, A uses the HNQ to suggest that p answers B’s question because of the social power imbalance between B and A, and B’s temper, allowing B to save some face.

8 Conclusion

I began the paper by reviewing facts about negative polar questions established in prior research: that HNQs require the speaker to be biased for the positive answer (the propositional prejacent), while LNQs do not. From there, there were several novel results of this paper, both empirical and theoretical. First, the empirical:

-

(1)

HNQs and polarity focus questions are distinct phenomena: while HNQs necessarily convey speaker bias, the bias of PFQs is context sensitive; moreover, only PFQs require a focus antecedent (Sect. 2.2).

-

(2)

The kind of bias arising from PFQs is not attached to polarity focus, but can appear in questions that lack any grammatical marker that has been linked previously to polarity/verum focus; moreover, the bias can have the same polarity as the question (Sect. 3).

-

(3)

A battery of tests reveals that the sentence radicals of HNQs are not negated; attempts to use NPIs to produce evidence of inner negation relative to these tests fails (Sect. 4).

These empirical results guided the theoretical proposals:

-

(1)

The speaker bias of PFQs is derived from more general facts about asking questions in some contexts that happen to also license polarity focus. If polarity focus is licensed by an interlocutor’s claim that p, then asking ?p leads to a ¬p speaker bias. Since the derivation untethers speaker bias from polarity (verum) focus, it accurately predicts that some PFQs lack speaker bias, and that some questions that lack polarity focus convey PFQ-like speaker bias (Sect. 3).

-

(2)

The lack of negation in the prejacents of HNQs in Sect. 4 supports the theoretical view that negation scopes over a high operator, keeping it outside of the question’s sentence radical. A simple account of this operator as doxastic necessity yields an unbalanced partition (Sect. 6), an idea in line with previous work (Romero and Han 2004; Krifka 2017).

-

(3)

The unbalanced partition is used to give a novel derivation of the necessary speaker bias associated with HNQs (Sect. 7). The idea is to derive the bias as a special kind of quantity implicature depending on competition between the HNQ and the positive polar question with the same propositional prejacent. The PPQ is stronger than the HNQ in the sense that the addressee’s positive and negative answers to the PPQ entail the answers to the HNQ, but the weaker cell of the HNQ (\(\neg\square_{A}~ p\)) does not entail any answer to the PPQ. Therefore, if the speaker is ignorant of whether p or ¬p, they should use the more informative PPQ. It follows that in contexts in which the speaker chooses to instead use the HNQ, they must not be ignorant, which is to say they must be biased for one of the answers. Finally, the fact that the bias is always for the propositional prejacent of the HNQ follows from the way in which the partition is unbalanced. If the speaker were biased for ¬p, then the weaker cell of the HNQ (\(\neg\square_{A}~ p\)) would not reveal whether the addressee shares the speaker’s bias, since \(\neg\square_{A}~ p\) is consistent not just with A’s belief in ¬p, but also A’s ignorance whether p or ¬p. If the speaker is biased for p, on the other hand, then either cell of the HNQ partition will resolve whether or not A shares that bias.

A limitation of the present account of HNQs is that the assumption in Sect. 6 that the speech act operator is doxastic necessity may be open to criticism. One reason that Romero (2015) and Frana and Rawlins (2019) moved the primary effects of verum to a non-at-issue dimension is that yes/no responses do not seem to incorporate the meaning of the verum operator, and the account I have proposed is open to the same criticism. However, as our understanding of polar particles as propositional anaphora has developed (Krifka 2013; Roelofsen and Farkas 2015; Goodhue and Wagner 2018), it has become clear that speech act operators like assert and common ground management operators like verum/falsum do not introduce the kinds of discourse referents that yes and no are sensitive to.

Still, the particular assert operator I have assumed may be open to many of the criticisms leveled at the performative hypothesis of Lakoff (1970) and Ross (1970) (see Levinson 1983, pp. 251-263, for a thorough critique). Ultimately, the operator that high negation scopes over is likely to be more sophisticated than simple doxastic necessity, and thus not open to these criticisms. My goal here has not been to propose a sophisticated theory of the dynamic semantics/pragmatics of speech act operators, but to demonstrate how an unbalanced partition arising from negation scoping over a high operator can be used to derive the speaker bias that HNQs are known for, and the simplest way to do that is with doxastic necessity.

That said, I believe that the prospects for applying the derivation of HNQ bias in Sect. 7 to other unbalanced partitions are bright. Due to space restrictions, I only briefly discuss commitment space semantics (Krifka 2015, 2017), though the proposed bias derivation could work with verum or falsum operators as well (Romero and Han 2004; Repp 2013; Romero 2015; Frana and Rawlins 2019). A commitment state c is modeled as a set of interlocutor commitments, e.g., c = {A is committed to p, A is committed to ¬q, B is committed to p, B is committed to q, …}, and a commitment space C is modeled as a set of commitment states representing the future possible developments of the current commitment state, e.g., C = {c, \(c'\), \(c''\), …}.Footnote 32 Speech acts are modeled as functions from commitment spaces to commitment spaces. The effect of a PPQ {p,¬p} is to move from the current commitment space C to a new one \(C^{PPQ}\) in which all of the commitment states are such that the addressee A either commits to p or to ¬p. Thus, the PPQ has the effect of removing all states in which A doesn’t commit one way or the other, and the resulting \(C^{PPQ}\) can be partitioned into two sets of states, those in which A commits to p, and those in which A commits to ¬p. Meanwhile, HNQs are modeled so that a special speech act negation, ∼, scopes over an ASSERT operator. The effect of an HNQ on a space C is to remove all states \(c'\) in which A commits to the proposition p embedded under ASSERT (essentially, the inverse or negation of the effect of A asserting and therefore committing to a proposition p). By removing states in which A commits to p, the commitment states left over in the updated \(C^{HNQ}\) can be partitioned into two kinds, those in which A commits to ¬p, and those in which A commits to neither p, nor ¬p. A is then free to accept or reject this move; if A rejects it, then A chooses the complement of \(C^{HNQ}\) (\(C - C^{HNQ}\)), and commits to p. This situation should look familiar from Sect. 7: the cell of \(C^{PPQ}\) in which A commits to p is identical to \(C - C^{HNQ}\). The cell of \(C^{PPQ}\) in which A commits to ¬p is a proper subset of (asymmetrically entails) the space \(C^{HNQ}\). Thus, the PPQ is predicted to be more informative about A’s commitments wrt p/¬p than the HNQ, and the HNQ bias derivation can proceed as it does in Sect. 7. A more detailed exploration of HNQs in commitment space semantics can be found in Goodhue (2022b).

Notes

I use ‘⇝’ to mark an implication, while remaining agnostic about what kind of implication it is. When present, all caps indicate the final, or nuclear, pitch accent in the utterance.