Abstract

The U.S. tax system applies to its citizens’ worldwide incomes and estates, whether those citizens live in the U.S. or abroad. Fully escaping the U.S. tax system requires renouncing U.S. citizenship, and in recent years a growing number have done so. Using administrative tax microdata, I provide new descriptive information about the population of individuals who have renounced U.S. citizenship. The typical renouncer had long lived abroad, was slightly wealthier than the typical American, and reported no or little net U.S. tax liability prior to their renunciation. Combined with information on the foreign jurisdictions where renouncers reside, the evidence suggests that most recent renunciations are a result of increasing compliance costs of maintaining U.S. citizenship while living abroad, and not a response to U.S. tax liability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Only two other countries, Eritrea and Myanmar, similarly tax their citizens regardless of residence. Eritrea levies a flat income tax of 2% on its citizens living abroad; Myanmar applies the same rates to its citizens’ income, whether derived at home or abroad.

I use the term “expatriation tax system” to refer to the laws and tax regulations that govern expatriation and citizenship renunciation; these include filing and reporting requirements, and tax liabilities incurred at and after renunciation. Following previous literature and the terminology of related legislation, I use the term “expatriation” to mean giving up U.S. citizenship, rather than merely moving abroad.

I rely on the list of tax havens used in Johannesen et al. (2020). As they note in footnote 1, “This list does not have any official role in IRS enforcement efforts.” Neither the IRS nor the U.S. Treasury have an officially accepted definition of a tax haven.

There are two model types of IGAs, Model 1 and Model 2. Belnap, Thornock, and Williams (2021) show specifically that Model 1 IGAs, comprising the vast majority of IGAs, were associated with higher-quality information sharing and thus higher FFI costs, relative to the combined group of Model 2 IGA and non-IGA jurisdictions.

I am especially grateful to Tom Hertz at the IRS for developing these data.

This is an imperfect proxy that in general would bias towards classification into the first group, as some individuals may maintain addresses in the U.S. even while living abroad, or may use a U.S.-based tax preparer’s address on their filings. Because not all renouncers are primary filers, I search for tax filings associated with their TIN as either primary or secondary filers, to ensure as much pre-renunciation location information about each individual as possible.

For example, consider the case of Oleg Tinkov, who had true net worth in excess of $1 billion but filed a Form 8854 reporting less than $2 million in net worth, and was subsequently indicted and pled guilty to filing false tax returns (Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs 2021).

In September 2019, the IRS announced “Relief Procedures for Certain Former Citizens”, which provide alternate means for satisfying the tax compliance certification process, available to U.S. citizens with a net worth less than $2 million and an aggregate tax liability of $25000 or less for the year of expatriation and the five prior years (https://www.irs.gov/individuals/international-taxpayers/relief-procedures-for-certain-former-citizens).

These population estimates are for households, and thus weighted towards higher amounts, relative to the renunciation statistics which are for individuals.

The 2018 Credit Suisse Global Wealth Report estimates that 17.35 million Americans were millionaires, or 7.1% of the adult population.

For example, legislative changes in the 1990s reportedly came about because then President Bill Clinton read about the tax-motivated expatriation of six wealthy Americans in Forbes magazine (Cooper and Melton 1995). More recently, Senators Chuck Schumer and Bob Casey proposed a bill to punish Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin for his pre-Facebook IPO expatriation (Romm 2012). The bill, titled the Expatriation Prevention by Abolishing Tax-Related Incentives for Offshore Tenancy, or Ex-PATRIOT Act, failed to make it out of committee.

Appendix A, Figure 18 shows a similar pattern when considering the average liability over the five years prior to renunciation.

Destination here refers to the foreign jurisdiction listed as a renouncer’s country of tax residency (when reported) or general residency (when tax residency is not reported or available). In almost all cases, tax residency and general residency are the same: more than 99% of the records with both tax residency and general residency have the same jurisdiction reported for both.

Press reports describe numerous anecdotes of U.S. citizens abroad facing such difficulties. See, e.g., Williams (2014), “U.S. expats find their money is no longer welcome at the bank” and Graffy (2015), “The law that makes U.S. expats toxic.” Some of these difficulties are only now starting to arise, as FATCA implementation was not necessarily immediate; France, for example, was set to start reporting information in 2020, prompting an August 2019 article warning of pending bank account closures for 40,000 U.S. citizens (Goncalves 2019).

One important group of individuals who were particularly affected by the enforcement changes were those hiding assets abroad. These individuals faced an ever-increasing likelihood of being discovered by the IRS. One response to this would be to come clean, pay any necessary penalties, and maintain U.S. citizenship. Another response would be to drop U.S. citizenship in an attempt to “sneak out” before the hidden assets could be discovered. However, because hidden assets are unobservable it is not possible to test directly whether individuals with such assets were more likely to expatriate following the increased enforcement actions.

Dharmapala (2016) models the behavior of FFIs under FATCA, with FFIs passing on the costs of information sharing to their accountholders through increased fees.

For instance, the JCT report notes at p. 7 that there may be discrepancies between the definitions used for the yeas 1962–1979 and 1980–1994.

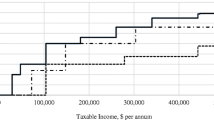

Among all covered expatriates, nearly 90% are over the net worth threshold, while only about 25% are over the average income tax liability threshold. The evidence suggests there is little direct response to the average income tax liability threshold, in that there is no bunching below that threshold. One explanation is that it is harder for taxpayers to adjust an average based on past-5 years income tax liabilities than it is to adjust reported net worth at the point of expatriation.

That the pattern is visible both before and after the HEART Act suggests that covered expatriate designation was viewed as costly even without the mark-to-market exit tax consequences introduced under the HEART Act.

For this analysis, I rely on gift amounts reported on Form 709 and charitable contributions reported on Schedule A.

Reported net worth is only completely available since mid-2004, when Form 8854 began to require all filers to list their reported net worth; prior to this change, only those with net worth above the tax-motivation threshold ($622 K in early 2004, adjusted upward for inflation over 1998–2004) were required to report this information.

I use the prior year to ensure a full year’s income is reported. In the year of renunciation itself, those renouncing citizenship file a Form 1040 representing the portion of the year they are a citizen, and may file a Form 1040 NR for the remaining portion of the year after they have renounced.

Those without filings or TINs are excluded due to lack of income data.

See, e.g., the Nomad Capitalist (https://nomadcapitalist.com/) or 1040Abroad (https://1040abroad.com/about/).

For example, whether a taxpayer already lives or holds citizenship abroad; the amount and type of income a taxpayer receives currently and expected to receive in the future; the amount and type of assets a taxpayer holds currently and expects to bequeath in the future; the tax system of the anticipated destination country; and whether a taxpayer is currently compliant on their U.S. taxes.

The thresholds during 2019 were $168 K (average past-five-years income tax liability) and $2 M (net worth). Figure 19 shows how these have changed over time. Note that the income tax liability threshold is applied to tax liabilities, not incomes; to have an income tax liability of $168 K in 2019 would have required income of more than $500 K. This distinction is sometimes missed in discussion of the expatriation tax system, with some suggesting that the threshold applies to income itself (and thus implying that many more individuals would be treated as covered expatriates according to this threshold than is truly the case).Fig. 21Statutory covered expatriate thresholds and gains exemptions over time

Between 1997 and July 2002, 270 applications for private letter rulings overturning the presumption of tax-motivated expatriation were made to the IRS. Of these about half received favorable responses, and all but 11 of the remainder received neutral responses. Favorable and neutral responses meant that applicants could proceed without fear of further IRS enforcement under the expatriation tax regime. This suggests that roughly 96% of appeals were successful (259/270 = 0.959) (Kwong 2009, 421).

Arsenault (2009) provides further information on the first two changes. For the Form 8854 filing requirement, see the amendment history of IRC §7701(n); the 2004 AJCA added §7701(n), stating that an expatriating individual is still treated as a citizen or resident of the U.S. until that individual “provides a statement in accordance with Sect. 6039G.”.

Exceptions include deferred compensation items, specified tax deferred accounts, and interest in non-grantor trusts.

For expatriations during 2019 the first $725 K of gains are exempt. Figure 19 shows how the exempted amount has changed over time.

Expatriating individuals are still required to file Form 8854 under IRC §6039G, but after the 2008 HEART Act’s removal of IRC §7701(n), failure to file Form 8854 no longer carries the consequence that an individual is treated as a U.S. citizen or resident for tax purposes until the form is filed. This change lowered the cost of non-filing and may help explain the large share of expatriating individuals in recent years without Form 8854 filings.

Kim’s estimates of renunciation rates show that the highest rates were in jurisdictions with military draft systems, with the top three rates observed for South Korea, Singapore, and Taiwan. While the relative comparison of rates across jurisdictions is certainly of interest, the many factors influencing citizenship decisions make it difficult to draw conclusions from these cross-jurisdiction comparisons. By focusing on the decisions of individuals specifically with respect to U.S. citizenship, observing trends over time, and using individual microdata, much can be learned about the motivation for citizenship renunciation and its connection to the tax system.

If required to specify customers in advance, the IRS would not have been able to meaningfully pursue the relevant information. U.S. taxpayers hiding assets did not notify the IRS of their holdings, and thus could not be identified ex ante and specified in requests for information.

Between 2008 and 2010, the U.S. signed such agreements with six jurisdictions: Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Panama, and Switzerland.

As noted above, due to data accessibility I focus in this paper on citizenship and not long-term residency status, but similar arguments can be made for the long-term resident population, with similar conclusions about the effect of the tax system on individuals’ decisions. In each year, the number of individuals relinquishing long-term residency status is far lower than the number applying for it.

I am not the first to draw this comparison; a similar point was made by Elise Bean in her testimony before the House Subcommittee on Government Operations in a hearing titled “Reviewing the Unintended Consequences of the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act,” held on April 26, 2017. In some respects, the discussion of renunciations is similar to that of corporate inversions: although the absolute number occurring is relatively small, there is still significant public press and legislative focus on the issue.

A similar framing considers citizenship as insurance. Herzfeld and Doernberg write that, “In effect, a citizen of the United States has an insurance policy, and taxes are the cost of maintaining that policy” (Herzfeld and Doernberg 2018, 24).

Some individuals who expatriate continue to file Form 1040 or Form 1040 NR after renunciation, depending on their income sources and other circumstances.

Schedule C includes income and loss from a business or profession practiced as a sole proprietor; Schedule E includes income and loss from rental real estate, royalties, partnerships, S corporations, estates, trusts, and residual interest in real estate mortgage investment conduits (REMICs).

In this main specification, seeking to explain the recent increase in Droppers, I include only the Droppers as renouncers, excluding Movers from the dataset in any year where they appear. I also run the models including all renouncers, and the results are nearly identical; see Table 13

References

Agrawal, D. R., & Foremny, D. (2019). Relocation of the rich: Migration in response to top tax rate changes from Spanish reforms. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 101(2), 214–232.

Ahn, J. J. E. J. (2015). The HEART act of 2008: To deter expatriation, but why more expatriation. North Carolina Journal of International Law and Commercial Regulation, 4, 1021–1084.

Akcigit, U., Baslandze, S., & Stantcheva, S. (2016). Taxation and the international mobility of inventors. American Economic Review, 106(10), 2930–2981.

Arsenault, S. J. (2009). Surviving a heart attack: Expatriation and the tax policy implications of the new exit tax. Akron Tax Journal, 24(2), 37.

Belnap, A., Jacob T., and Braden W. (2021). Hidden Wealth and automatic information sharing. Working paper.

Bilal, A., & Ross-Hansberg, E. (2021). Location as an Asset. Econometrica, 89(5), 2459–2495.

Christians, A. (2017). Buying in: Residence and citizenship by investment. Saint Louis University Law Journal, 62, 51–72.

Cooper, K. J., & Melton, R. H. (1995). Tax breaks for wealthy expatriates sparks class warfare charges. The Washington Post, March 31.

Craig, B. (2012). Congress, have a heart: Practical solutions to punitive measures plaguing the HEART act’s expatriate inheritance tax. Temple International & Comparative Law Journal, 1, 69–102.

Denson, T. (2015). Goodbye, uncle Sam? how the foreign account tax compliance act is causing a drastic increase in the number of Americans renouncing their citizenship. Houston Law Review, 52(3), 967–1005.

Department of Justice, Office of Public Affairs. (2021). Founder of Russian Bank Pleads Guilty to Tax Fraud. October 1. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/founder-russian-bank-pleads-guilty-tax-fraud.

Dharmapala, D. (2016). Cross-border tax evasion under a unilateral FATCA regime. Journal of Public Economics, 141, 29–37.

Goncalves, P. (2019). FATCA could push French banks to close up to 40,000 accounts. International Investment, August 14.

Graffy, C. (2015) The law that makes U.S. expats toxic. The Wall Street Journal, October 10.

Herzfeld, M., & Doernberg, R. L. (2018). International Taxation in a Nutshell (11th ed.). West.

Johannesen, N., Langetieg, P., Reck, D., Risch, M., & Slemrod, J. (2020). Taxing hidden wealth: The consequences of U.S. enforcement initiatives on evasive foreign accounts. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 12(3), 312–346.

Joint Committee on Taxation. (1995). Issues presented by proposals to modify the tax treatment of expatriation: A report. JCS-17–95.

Joint Committee on Taxation. (2003). Review of the present-law tax and immigration treatment of relinquishment of citizenship and termination of long-term residency. JCS-2–03.

Kim, Y. R. (2017). Considering “Citizenship Taxation”: In Defense of FATCA. Florida Tax Review, 20(5), 335–370.

Kingson, J. (2021b). Wealthy people are renouncing American citizenship. Axios, August 5.

Kleven, H., Landais, C., Muñoz, M., & Stantcheva, S. (2020). Taxation and migration: Evidence and policy implications. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 34(2), 119–142.

Kleven, H., Landais, C., & Saez, E. (2013). Taxation and international migration of superstars: Evidence from the European football market. American Economic Review, 103(5), 1892–1924.

Kudrle, R. T. (2015). Expatriation: A last refuge for the wealthy? Global Policy, 6(4), 408–417.

Kwong, Y. H. S. (2009). Catch me if you can: Relinquishing citizenship for taxation purposes after the 2008 HEART act. Houston Business and Tax Journal, 9, 411–444.

Manolakas, C., & Dentino, W. L. (2012). The exit tax: A move in the right direction. William & Mary Business Law Review, 3, 341–418.

Mason, R. (2016). Citizenship taxation. Southern California Law Review, 89, 169–240.

McGinty, JC. (2020). More Americans are renouncing their citizenship. The Wall Street Journal, October 16.

Mirrlees, J. A. (1982). Migration and optimal income taxes. Journal of Public Economics, 18(3), 319–341.

Moretti, E., & Wilson, D. J. (2017). The effect of state taxes on the geographical location of top earners: Evidence from star scientists. American Economic Review, 107(7), 1858–1903.

Muñoz, M. (2020). Do European top earners react to labour taxation through migration? Working paper.

Naughtie, A. (2021). Record number of wealthy Americans dropped US citizenship in 2020, say IRS figures. The Independent, August 5.

Richards, PJ. (2016). Delays, costs mount for Canadians renouncing U.S. citizenship." The Globe and Mail, February 9.

Romm, Tony. 2012. "Pols plan would tax Facebook expat." Politico, May 17.

Rubolino, E. (2021). Tax-induced transfer of residence: Evidence from tax decentralization in Italy." Working paper.

Sheppard, L. (2009). "Don't ask, don't tell, part 4: Ineffectual information sharing." Tax Notes, March 23.

Simone, De., Lisa, R. L., & Markle, K. (2020). Transparency and tax evasion: Evidence from the foreign account tax compliance act (FATCA). Journal of Accounting Research, 58(1), 105–153.

Westin, R. A. (2000). Expatriation and return: An examination of tax-driven expatriation by united states citizens, and reform proposals. Virginia Tax Review, 20(1), 75–190.

Williams, G. (2014). U.S. expats find their money is no longer welcome at the bank. Reuters, June 11.

Wood, R.W. (2013). U.S. citizens renouncing skyrocket—The Tina Turner Effect. Forbes, November 15.

Young, C., Varner, C., Lurie, I. Z., & Prisinzano, R. (2016). Millionaire migration and taxation of the elite: evidence from administrative data. American Sociological Review, 81(3), 421–446.

Young, C., Ithai, L. 2022. "Taxing the Rich: How Incentives and Embeddedness Shape Millionaire Tax Flight." Working Paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

For helpful comments, suggestions, and support I thank my dissertation committee: Joel Slemrod, Jim Hines, Ash Craig, and Ed Fox; thanks also to Ron Davies (editor), two anonymous referees, Katarzyna Bilicka, Sebastien Bradley, Dhammika Dharmapala, Gabe Ehrlich, Jeff Hoopes, Daniel Reck, Max Risch, Molly Saunders-Scott, Bill Strang, and seminar participants at the University of Michigan, IRS, Joint Committee on Taxation, U.S. Treasury Office of Tax Analysis, 2020 NTA Annual Conference, 2021 IIPF Annual Congress, and 2021 Oxford CBT Doctoral Conference. I am especially grateful to John Guyton, Anne Herlache, Tom Hertz, Pat Langetieg, Alicia Miller, Annette Portz, Alex Turk, and Carlos Zepeda at the IRS for their support of this work. This is an updated draft of a working paper originally posted to SOI Tax Stats (www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/21rpcitizenshipandtaxes.pdf). This research was conducted while the author was an employee at the IRS and the U.S. Department of the Treasury, and at no time was confidential taxpayer data ever outside of the IRS computing environment. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or the official positions of the U.S. Department of the Treasury or the Internal Revenue Service. All results have been reviewed to ensure that no confidential information is disclosed.

Appendices

Appendix A: Additional figures and tables

In the main text of this paper I focus on renunciations from 1998–2018, the years for which the administrative tax data with information on those renouncing U.S. citizenship is available and complete. Using outside sources, it is also possible to provide some context on renunciations covering a longer time period. Annual counts of U.S. citizen renunciations are available for the years 1962–1994 from the State Department, as listed in a report discussing proposals for changes to the tax treatment of expatriation (Joint Committee on Taxation 1995). These can be paired with annual counts of individuals reported in the Federal Register as having relinquished citizenship, which are available for the years 1998–2020. Note that because of slight differences in the way numbers were tracked from year to year and the precise criteria for inclusion, these sources may not be exactly comparable with each other, nor with the counts I present above.Footnote 20 Still, all three capture a similar idea and allow for consideration of trends over time.

Figure 6 below shows the JCT and Federal Register series, with the JCT numbers in blue and the Federal Register numbers in green. The longer-term trend shows that renunciations were actually somewhat more common in the 1960s and 1970s, and had fallen to a relative low by the 2000s, before increasing in the past decade, as discussed above.

Annual count of renunciations (JCT and Federal Register). Notes: This figure plots the count of U.S. citizenship renunciations from two sources. For the years 1962–1994, the values are as reported in Joint Committee on Taxation (1995). For the years 1998–2020, the values are the count of names published in the Federal Register as the “Quarterly Publication of Individuals Who Have Chosen to Expatriate”, required under IRC §6039G

In Sect. 3, I show that most of those renouncing citizenship lived abroad for at least five years prior to renunciation. Figure 7 shows that this pattern holds true when looking only at two years of pre-renunciation U.S. tax filings (top panel) or ten years (bottom panel).

Annual counts, split by pre-renunciation location (using 2, 5, and 10 years of tax filings). Notes: This figure plots the count of individuals who renounced U.S. citizenship each year, split by their classification based on U.S. tax filing behavior during the two, five, or ten years prior to renunciation. Tax data is available from 1999 onwards. Thus, for the two-year graph (top panel), only renunciations from 2001 onwards are included. Similarly, the five-year graph includes renunciations from 2004 onward, and the ten-year graph from 2009 onward

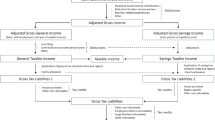

As described further in Appendix B, expatriating individuals are subjected to a test that determines whether they are a covered expatriate. The test has three components, any one of which results in designation as a covered expatriate: (1) net worth above a threshold; (2) past-five-years average income tax liability above a threshold; and (3) failing to certify compliance on U.S. taxes for the five years prior to expatriation. Covered expatriate status results in additional filing requirements, as well as potential additional tax liability. Prior to the HEART Act in 2008, this tax liability was based on income earned during the 10 years following expatriation, which could be liable for U.S. income taxation. Since the HEART Act, this tax liability is a mark-to-market exit tax based on the value of all assets owned on the day prior to expatriation, with taxes applied to gains above a statutory exemption.

For most covered expatriates, the net worth threshold is the crucial component.Footnote 21 Since mid-2004, the net worth threshold has been constant at $2 M. A histogram of renouncers’ reported net worth around this threshold reveals a strong response, as shown in Fig. 8: a sharp drop-off in the number of renouncers reporting net worth just above the threshold. This figure shows the aggregate histogram for all renunciations from mid-2004, when the AJCA took effect and net worth data become widely available, through 2018. Although not presented here for disclosure reasons, the pattern is also visible within each year.Footnote 22 There are several plausible explanations for this drop-off: some potential renouncers with net worth above $2 M may have been discouraged from renouncing; some may have taken actions to reduce net worth below the $2 M threshold (for example, by making gifts or charitable contributions); and some may have reported net worth lower than their actual net worth, in order to appear below the threshold. In addition, recall that only about half of renouncing individuals have a filed Form 8854 with reported net worth data available; it is possible that some individuals with net worth above the threshold chose not to file Form 8854.

Histogram of reported net worth around $2 million. Notes: This figure plots the count of renouncers in each $100 K bucket around the $2 M threshold for designation as a covered expatriate. Renunciations with a filed Form 8854 and available reported net worth data, after the AJCA (mid-June 2004) through 2018, are included. The drop-off in filings with reported net worth occurs exactly at the cutoff for covered expatriate designation, suggesting it is this cutoff that is driving the observed behavior; there is no drop-off at either $1 or $3 M, suggesting that round-number bunching can be ruled out as an explanation for the observed pattern

There is evidence that for some taxpayers, gifts may have been used to get below the threshold. 8% of the individuals who report net worth of $1-2 M would have had net worth above $2 M if gifts they reported making in the 0–2 years prior to renunciation were added to their reported net worth. A handful of individuals similarly would move from below the threshold to above it if their pre-renunciation charitable contributions were added to their reported net worth.Footnote 23 Still, even after adjusting the reported net worth amounts to include recent gifts and charitable contributions, a large “hole” to the right of the threshold remains. One feature of Form 8854 (the expatriation tax form) is that it requires individuals to provide a balance sheet with assets listed by asset type; although not presently available, these data could in future be used to further explore the patterns shown here.

Figure 9 shows the annual count of renunciations, grouped by reported net worth.Footnote 24 The net worth buckets correspond to the thresholds for covered expatriate designation: $622 K (the threshold prior to the AJCA, i.e., prior to June 2004) and $2 M (the threshold since the AJCA, i.e., after June 2004).

A few patterns are worth noting. First, although there has been a small rise in the number of renunciations by those reporting net worth of at least $2 M (the green bars), these still represent a relatively small share of the total. Second, there has been more substantial growth in the number reporting between $622,000 and $2 M in net worth (the blue bars); this group is relevant because it represents the individuals who prior to the AJCA would have been designated as covered expatriates, but after the raising of the net worth threshold no longer faced such designation. At the same time, there was similar growth in those reporting less than $622 K (the orange bars). Finally, an important pattern is the persistent large share of renunciations without Form 8854 or without reported net worth data, (the gray bars). Although filing Form 8854 is a necessary step to fully complete one’s citizenship renunciation, a significant number of individuals still have not done so. Some of this pattern in more recent years could reflect that some file Form 8854 with a lag (this likely explains the difference between 2017 and 2018-those who renounced in 2018 and plan to file Form 8854 may still be finalizing their filings). Although this non-filing limits the ability to draw comprehensive conclusions about the wealth of all renouncers, useful information can still be gleaned by studying those for whom data are available.

I next consider how the wealth of those renouncing each year has changed over time, and whether this differs for those moving from the U.S. relative to those who were already abroad. I call these two groups “Movers” (those that filed from a U.S. address in at last one of the five years prior to renunciation) and “Droppers” (those that always filed from abroad in the five years prior to renunciation). Figure 10 reports the mean reported net worth of those renouncing each year since 2005, separately for Movers and Droppers (only including those with reported net worth data available). Movers are wealthier than Droppers. Average renouncer wealth during the 2004–2010 period was notably higher than in more recent years. Removing the top 10 individuals in each group each year has a dramatic effect on the average values. Similar patterns emerge when considering the median values (see Fig. 11).

Comparison of reported net worth among renouncers, Movers versus Droppers. Notes: This figure compares reported net worth among those renouncing each year, separately for Movers and Droppers. Only those with reported net worth data available are included. The left panel includes all Movers and Droppers; right panel drops the top 10 Movers and Droppers, by reported net worth, each year

Comparison of reported net worth among renouncers, Movers versus Droppers, mean and median. Notes This figure compares reported net worth among those renouncing each year, separately for Movers and Droppers. Only those with reported net worth data available are included. The left panel includes all Movers and Droppers; right panel drops the top 10 Movers and Droppers, by reported net worth, each year

It is also interesting to consider how renouncers compare to others in terms of income. Figure 12 reports renouncers’ mean total income and wage income for the year prior to renunciation, and compares this to two other groups: (i) all other filings from foreign addresses, and (ii) a sample of the full population of Form 1040 filings. In orange are renouncers who were the primary filer for a linked 1040 in the year prior to renunciation.Footnote 25 In blue are all other Form 1040 filings from foreign addresses for the given year, and in gray are a sample of all Form 1040 filings. The vertical dashed lines represent three key dates related to expatriation tax law: 2004 AJCA (raising the net worth threshold for covered expatriate designation), 2008 HEART Act (introducing the mark-to-market exit tax), and 2010 FATCA (increasing information reporting of foreign financial accounts held by U.S. citizens). To illustrate the influence of a few outliers on the mean value among renouncers, the dashed line removes the top 10 individuals for each year.

Comparison of income for renouncers, foreign filers, and all tax filers. Notes: This figure compares the income of renouncers in the year prior to renunciation to two comparison groups: all other foreign filings, and a sample of the population of Form 1040 filing. For renouncers, only primary filers with linked filings are included. The three vertical dashed lines represent three key dates related to expatriation tax law: the 2004 AJCA, the 2008 HEART Act, and 2010 FATCA. The solid line includes all individuals; the dashed line removes the top 10 in each year

Figure 12 demonstrates that the average income of those renouncing each year has changed dramatically over time, and that outlier individuals play an important role in driving the annual averages. Those renouncing during the window between 2004 (AJCA) and 2010 (FATCA) were on average much higher income, relative to those expatriating in the 2010s; and this is true even when removing the top 10 individuals each year. Prior to 2010, those renouncing were higher income, on average, than both other foreign filers and the broader U.S. filer population. Since 2010, those renouncing have had lower income, on average, than other foreign filers, but still higher than the U.S. filer population overall. Similar trends appear when considering the median values instead of the mean (see Fig. 13).

Comparison of income for renouncers, foreign filers, and all tax filers, mean and median. Notes: This figure compares the income of renouncers in the year prior to renunciation to two comparison groups: all other foreign filings, and a sample of the population of Form 1040 filing. For renouncers, only primary filers with linked filings are included. The three vertical dashed lines represent three key dates related to expatriation tax law: the 2004 AJCA, the 2008 HEART Act, and 2010 FATCA. The solid line includes all individuals; the dashed line removes the top 10 in each year

For more detail about the income of renouncers, consider Fig. 14, which compares the income just for renouncers, with averages calculated separately for Movers and Droppers.Footnote 26 For both groups, incomes were higher during the 2005–2010 time period, but the big outliers for total income are among the Movers, not the Droppers. The groups also differ in terms of their source of income; Movers have higher average total income, but Droppers have higher average wage income. The dramatic influence of the top 10 individuals each year on the average total income among Movers is a stark example of the nature of the renunciation policy problem: although most individuals have a small revenue impact, a handful can have a significant effect. As above, similar trends are seen in the median values (see Fig. 15).

Comparison of income among renouncers, Movers versus Droppers. Notes: This figure compares the income in the year prior to renunciation for renouncers with linked Form 1040 filings as primary filers. The mean values are calculated separately among Movers and Droppers. Renouncers with no filings or no TINs are excluded

Comparison of income among renouncers, Movers versus Droppers, mean and median. Notes: This figure comparison the income in the year prior to renunciation for renouncers with linked Form 1040 filings as primary filers. The mean values are calculated separately among Movers and Droppers. Renouncers with no filings or no TINs are excluded

Figure16 shows the share (in Panel A) and count (in Panel B) of renouncers in each year going to the top five destination jurisdictions (by total count from 1998 to 2018), and all others. Over time renunciation has become more concentrated in the top five destinations, with the share going to destinations outside these top five falling from about 50% in the 2000s to 30% in 2013, although this share ticked back up to 40% by 2018. In recent years, the share renouncing to Canada has risen dramatically. Also of note is the sharp rise and gentler fall in renunciations to Switzerland. The tables following Fig. 16 show that the top destinations are similar when looking within various subgroups (net worth, pre-renunciation location). Table 4 reports the top destinations by total count from 2005–2018, first among all renouncers (as in the left panel of Table 2 in the main text), and then within each reported net worth group. Table 5 similarly reports the top destinations, now split by classification based on pre-renunciation tax filings. Table 6 reports summary statistics for the data underlying the jurisdiction-level regressions discussed in Jurisdiction characteristics. Table 7 reports regression results for two robustness checks related to the Citizenship-for-sale variable. The results suggest that the negative coefficient on CFS in the main regression (see Table 3 in the main text) is driven by the few non-haven CFS jurisdictions, where renunciation is relatively uncommon. Table 8 provides a series of summary statistics that help to answer the question of whether recent renunciations would be likely to have a significant impact on U.S. revenue. Figure 17 shows the count of renouncers each year, split by their U.S. tax liability in the year prior to their renunciation. Figure 18 shows, among those with linked tax returns, the share of renouncers in each pre-renunciation average tax liability group. This shows a pattern similar to Fig. 3 in the main text, but in Fig. 18 the groups are defined based on average liability over the five years of pre-renunciation tax filings, whereas Fig. 3 used the single year prior to renunciation.

Annual count of renunciations, split by pre-renunciation U.S. tax liability. Notes: This figure plots the count of individuals renouncing each year, split by their U.S. tax liability in the year prior to renunciation. In gray are those without linked U.S. tax filings (mostly due to lack of TIN/SSN for linking). In orange are those with zero net liability; in blue those with < $1000 in net liability; and in green, those with > $1000 in net liability. Most of the recent increase in renunciation is from those without filings or liability

Share of renouncers with linked tax returns, split by pre-renunciation U.S. tax liability (averaged over five years).Notes: This figure reports the share of individuals renouncing in a given year based on their average U.S. tax liability during the five years prior to renunciation. Individuals are grouped into those with no liability in all five years, average annual liability < $1000, and average annual liability > $1000. This share is calculated only among those renouncers who are linked as a primary filer on a Form 1040

Appendix B: Background and institutional details

2.1 The process of U.S. citizenship renunciation

Section 349(a) of the Immigration and Nationality Act outlines the seven acts by which a U.S. national can voluntarily relinquish U.S. nationality: (1) obtaining naturalization in a foreign state once 18 years or older; (2) declaring allegiance to a foreign state once 18 years or older; (3) serving in the armed forces of a foreign state, either as an officer or engaged in hostilities against the U.S.; (4) serving a foreign government if that service requires foreign nationality or allegiance; (5) making a formal renunciation of nationality before a diplomatic or consular officer of the USA in a foreign state; (6) making a formal written renunciation of nationality in the USA (when the USA is at war and the renunciation is approved by the Attorney General); and (7) committing treason against or attempting to overthrow the U.S. government (8 U.S.C. §1481).

The fifth option is the main approach taken by those choosing to lose their U.S. citizenship. The required steps include preparing the necessary forms, meeting with a diplomatic or consular officer in a foreign state, swearing an oath of renunciation, and paying the renunciation fee. In most cases, renunciation requires two separate appointments at a foreign embassy or consulate. In the first appointment, the U.S. citizen is interviewed to confirm that renunciation is being done out of free will and not under duress. At the second appointment, an oath of renunciation is sworn. The current fee for citizenship renunciation is $2350 (until mid-2014 the fee was $450, and there was no fee before 2010). Because of the recent increase in renunciations, some embassies and consulates have experienced backlogs of renunciation appointments, leading to delays or prompting some individuals to travel to other cities and countries to seek earlier appointments (Richards, 2016). Various third-party firms offer services to U.S. citizens considering citizenship renunciation, promising to assist with the process and often targeting their marketing at high-wealth individuals.Footnote 27

After completing these steps, the State Department processes the renunciation and sends the individual a Certificate of Loss of Nationality confirming the renunciation of U.S. citizenship. Those renouncing citizenship must also file a U.S. income tax form for the year in which they renounced citizenship and include Form 8854 to complete renunciation for tax purposes (and remit or make arrangements to remit any associated tax liability). Because expatriation is an individual process, each individual must file a separate Form 8854, even if filing Form 1040 with married filing jointly status.

Figure 19 below plots the changes over time in the income tax and net worth thresholds for covered expatriate designation, as well as the changes in the capital gains exemption available to those who are deemed covered expatriates and subject to the mark-to-market exit tax (since 2008).

Costs and benefits of citizenship renunciation

The costs and benefits of citizenship renunciation for any given taxpayer depend on a variety of taxpayer characteristics,Footnote 28 but can generally be grouped into the categories shown in Table 9: administrative costs and benefits (e.g., renunciation fee vs. removal of U.S. tax filing obligation) and income- or wealth-dependent tax consequences (e.g., expatriation tax consequences vs. lower future income or estate tax liabilities). This high-level framework allows a consideration of how the net benefits of renunciation would change as any of the component costs or benefits change. For example, consider one change which occurred in 2014, when the State Department raised the fee for citizenship renunciation from $450 to $2350. This change uniformly lowered the net benefits of citizenship renunciation for all individuals considering it by $1900.

Some of these costs and benefits are simple to value (the renunciation fee is known and is exactly $2350) while others are longer-term and more uncertain (e.g., comparing expected U.S. income tax liability vs. foreign income tax liability on the next 10 years of income). However, even when exact values are unavailable, as long as one can characterize the sign of the change, it is possible to elicit a prediction about the effect of a policy change on the incentive to expatriate. In later sections I will discuss several changes to expatriation tax law or offshore financial enforcement and consider how these policy changes would be expected to affect incentives for certain types of taxpayers considering citizenship renunciation.

Citizenship and U.S. tax law

The U.S. tax system has attempted to discourage tax-motivated expatriation for several decades. The Foreign Investors Tax Act of 1966 introduced §877 of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC), requiring taxation of former citizens for ten years following expatriation if tax avoidance was a “principal purpose of the expatriation” (Craig, 2012). Thirty years later, a formal test for tax-motivated expatriation was introduced, as part of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). Under the new objective standards, expatriating individuals were deemed “covered expatriates” if either past-five-years average net income tax liability exceeded a certain threshold, or if net worth exceeded a different threshold.Footnote 29 Taxpayers also had to certify that they were compliant on all federal tax obligations for the five tax years preceding expatriation. As before, designation as a covered expatriate meant a taxpayer was liable for U.S. taxes on U.S.-source income and on income effectively connected with a trade or business in the U.S., at the same progressive rates faced by U.S. citizens, for the ten years following expatriation. In practice, even if a taxpayer was deemed a covered expatriate under the objective tests, one could appeal this designation and most who did so were successful.Footnote 30 Also of note, in an attempt to further discourage tax-motivated expatriation, HIPAA required the names of expatriating individuals to be published in the Federal Register (Internal Revenue Code, §6039G).

The American Jobs Creation Act (AJCA) of 2004 brought additional changes: (1) the removal of expatriates’ ability to challenge their designation as tax-motivated, (2) an increase in the net worth threshold from $622,000 to $2 M; and (3) requiring the filing of Form 8854 to complete expatriation for tax purposes.Footnote 31 The next changes were introduced in the 2008 Heroes Earnings Assistance and Relief Tax (HEART) Act, which created IRC §877A and changed the consequences for covered expatriate designation to now include a mark-to-market exit tax, rather than the taxation of next-ten-years’ U.S.-source income. Under the new regime, gains on all of a covered expatriate's assets (with a few minor exceptionsFootnote 32) are deemed realized as of the day prior to the expatriation date, and taxes owed on deemed gains above a certain exempted amount.Footnote 33 The 2008 bill also removed the requirement that Form 8854 be filed to complete expatriation for tax purposes.Footnote 34 Selected aspects and changes to the expatriation tax system are shown in Table 10.

Academic research on expatriation has mainly appeared in law journals, and generally focuses on detailed components of related legislation or proposed changes to the expatriation tax system (Arsenault, 2009, Kwong 2009, Manolakas & Dentino, 2012, Craig, 2012). Westin (2000) provides a comprehensive overview of the expatriation tax system prior to the reforms of the 2000s. More recently, Ahn (2015) studies the HEART Act and notes an increase in expatriations following the introduction of the deemed realization tax that can be seen in public data from the Federal Register.

Mason (2016) provides a thorough evaluation of various arguments for and against citizenship-based taxation. In response to Mason, Kim (2017) argues in favor of citizenship taxation and discusses how citizenship renunciation rates for the U.S. compares to other high-income countries. Noting the difficulty of defining a denominator when calculating the renunciation rates, Kim provides several plausible estimates based on 2010 and 2013 foreign diaspora data and relying on aggregate counts of renunciations, and concludes that the U.S. is not a serious outlier.Footnote 35 Kim also notes that “we lack empirical studies on the specific motivation of renunciation,” a concern also raised by Kudrle (2015). This is precisely the gap that this paper aims to fill. More recently, De Simone, Lester, and Markle (2020) study how U.S. individuals responded to FATCA. Although their paper focuses on portfolio investments based in foreign tax havens, the authors also make use of the public Federal Register data to plot the annual counts and suggest that the recent rise in U.S. expatriations could be related to FATCA.

This paper is the first to study in detail and quantitatively the connection between citizenship renunciation and citizenship-based taxation. There is a related literature in economics which studies the connection between taxes and migration, generally studying residence-based taxation (Mirrlees, 1982; Kleven et al., 2013; Akcigit et al., 2016, Kleven, Landais and Muñoz, et al. 2020). The distinction between residence-based and citizenship-based taxation is important because changing one’s residence is more reversible than changing one’s citizenship (and may carry different costs as well). By using administrative data including Form 8854 filings, which allow for a more detailed study of the population of those renouncing citizenship, this paper makes an important contribution to measuring and understanding the incentives to maintain or renounce citizenship under a citizen-based taxation system.

Tax enforcement and foreign financial activity

In the last decade, major changes have been made in the enforcement environment affecting financial activity by U.S. citizens living or holding financial accounts abroad. Johannesen et al. (2020) describe the introduction since 2008 of “a range of enforcement initiatives targeting owners of offshore accounts”: ad hoc legal action and information exchanges; bilateral treaties; and FATCA.

Ad hoc legal action against Swiss banks included so-called “John Doe summonses”, which allowed the IRS to request information from foreign banks about their U.S. citizen customers without identifying the specific customers in advance.Footnote 36 The IRS was authorized to use these summonses beginning in July 2008 against UBS, and subsequently against other large banks including HSBC and Credit Suisse. In addition to the ad hoc legal steps, the U.S. government signed bilateral information exchange agreements with several countries deemed to be tax havens.Footnote 37 These agreements allowed the IRS to request foreign bank account information for specific taxpayers in tax evasion cases. As Johannesen et al. note, citing Sheppard (2009), these agreements are relatively restrictive, requiring specification of taxpayer identities in advance and evidence to justify the request, and thus may not be effective deterrents of offshore tax evasion.

Finally, a new reporting regime requiring systematic information exchange on U.S. citizen account holders between foreign financial institutions (FFIs) or foreign tax authorities and the IRS was introduced in 2010, as part of FATCA. This may have affected U.S. citizens living abroad in two main ways. First, the IRS would now have better access to third-party reporting on income and assets for these individuals. Second, these individuals now faced increased costs (either financial costs or compliance costs) in their dealings with FFIs, as those FFIs themselves faced increased costs in complying with FATCA. Dharmapala (2016) studies how a unilateral reporting regime (like FATCA) affects the cost to FFIs of providing financial services and how this in turn affects incentives for tax-compliant behavior by foreign residents. Belnap, Thornock, and Williams (2021) study foreign countries’ and FFIs’ participation in automatic information sharing with the IRS and show that FFI participation was near-universal (97% of FFIs participated in automatic information sharing) and costly. They also show, however, that the quality of information shared varies considerably across FFIs and jurisdictions.

These enforcement changes are relevant to the study of citizenship renunciation because each change either made it more difficult, or less attractive, to be a U.S. citizen living and maintaining financial accounts abroad. This paper is the first to study carefully the potentially unintended consequence of these changes in tax enforcement–increased U.S. citizenship renunciation by U.S. citizens living abroad.

Net flow of U.S. citizenship

To evaluate the effect of the tax system on citizenship decisions overall, one should consider both inflows (naturalizations) and outflows (renunciations). Although the relative increase in renunciations over the last decade is remarkable, the net flow (naturalizations less renunciations) is still vastly tilted toward in-migration. Figure 20 plots the annual count of naturalizations (those receiving U.S. citizenship) in gray, and renunciations (plotted with negative values) in orange. The renunciations are just barely distinguishable at the bottom of the graph, two orders of magnitude smaller than the naturalizations. In every year between 1998 and 2018, the number of naturalizations was above 40,00,00. This compares to a total of roughly 40,000 citizenship renunciations between 1998 and 2018.Footnote 38

What about those who already have citizenship, and choose not to renounce it? This describes almost all U.S. citizens. There are more than 300 million such individuals, and typically fewer than 5000 renouncing each year. The number of renunciations is still tiny even when compared to the stock of U.S. citizens abroad, who could more readily renounce. Although the exact number of U.S. citizens living abroad is not known, some estimates put it at perhaps nine million, and the number filing taxes from foreign addresses is more than one million per year. A few thousand renunciations per year thus represents, as a conservative upper bound, less than half of 1 percent of those living abroad.Footnote 39 This suggests another lesson from the fact that the increased compliance costs under FATCA induced some individuals abroad to drop their U.S. citizenship: those costs did not induce vastly many more foreign-resident U.S. citizens to drop citizenship, implying that for those individuals the maintenance of U.S. citizenship was worth incurring the resulting financial and hassle costs of complying with new regulations, and thus that they place a relatively high value on U.S. citizenship.

Appendix C: Individual determinants of renunciation

This section considers why individuals decide to renounce U.S. citizenship. I develop a framework for the decision of those living abroad to maintain or drop citizenship using a simple option value approach. I then use this framework to motivate empirical tests, first using individual-level data to test various determinants of renunciation and confirm that age is positively correlated with renunciation, then using a difference-in-differences approach to show that increased compliance costs help explain the recent increase in renunciations.

Theoretical framework

For U.S. citizens living abroad, U.S. citizenship can be thought of in an option value framework, somewhat similar to the framing of “location as an asset” (Bilal & Ross-Hansberg, 2021).Footnote 40 For those abroad, U.S. citizenship represents an American-style call option in which the foreign resident U.S. citizen retains the right to return to the U.S. to live or work at some point in the future. Typically, option value can be decomposed into time value and intrinsic value. Time value for the option on U.S. citizenship corresponds to age: as individuals get older, the remaining time in which they can exercise the option decreases, leading the value of that option to decrease as well. All else equal, this suggests that the probability of renunciation should increase with age.

The intrinsic value of the option on U.S. citizenship comprises many components. First, consider that for a typical financial option, the value of that option increases with the volatility of the underlying asset. Similarly, the value of U.S. citizenship should increase as volatility increases. Volatility in this case could include global economic uncertainty and the political stability of foreign countries relative to the United States; those living in more stable countries may consider themselves less likely to want or need to exercise the option to return to or work in the U.S., and thus be more likely to renounce U.S. citizenship. Other components of the intrinsic value could include the tax rates of the foreign country relative to the U.S. and the relative value of the foreign country’s passport. For those living in countries with lower relative rates, the value of the option on U.S. citizenship would be lower, while for those in countries with a relatively more valuable passport, the option value of being able to use one’s U.S. passport would be lower.

Finally, in addition to the value of the option, consider the cost of maintaining it. This cost has always included remitting one’s annual tax liability, if any, as well as the compliance costs, including time and effort, of annual filing of U.S. tax returns. These compliance costs have increased in recent years, with additional forms required for many taxpayers, both by tax agencies and financial institutions. In the next sections I test whether the predictions of this framework are borne out in the data.

Individual determinants of renunciation

To begin testing the implications of the options model, I focus first on identifying characteristics associated with the costs and benefits of the decision of those living abroad to renounce citizenship. Although not all the reasons someone might choose to renounce are captured in tax filings, administrative microdata still allow me to test how several key characteristics relate to renunciation.

The base for this study is the set of all U.S. tax filings by those filing from abroad. This includes Form 1040 filings, and other linked tax form data, for those filing from abroad for tax years 2007–2017. Among these filings, I identify the individuals who ultimately renounce citizenship, and flag the tax year prior to the year in which they expatriate, dropping subsequent filings for these individuals if they appear.Footnote 41 As noted above, I consider the tax information in the year prior to the year of expatriation as the most relevant, because it is represents a complete year of earnings and other taxpayer decisions. The final dataset contains about 17000 instances of citizenship renunciation (I include only primary filers, and am unable to include individuals without TINs or linked tax filings), out of more than four million tax filings from those living abroad.

I develop a simple linear probability model, regressing Renounce (the decision to renounce citizenship in the following year) on a set of individual-year covariates and, in some specifications, jurisdiction, year, or jurisdiction X year fixed effects:

These covariates include: total positive income (TPI) in millions of dollars; wages as a share of total positive income (0 if no TPI); a dummy indicating the taxpayer had a positive tax liability (net of foreign tax credits and income exclusions); dummies indicating whether a taxpayer had nonzero values reported for Schedule C or Schedule E income, respectively,Footnote 42 a dummy indicating that a charitable contribution deduction was claimed on Schedule A, a dummy indicating Form 709, the U.S. Gift and Generation-Skipping Transfer Tax Return, was filed; and a dummy indicating a taxpayer received any notice from the IRS. In some specifications I include age (in years), though this slightly lowers the observation count because of some missing data on dates of birth. Table 11 presents summary statistics for these variables.

The results of the basic linear probability model are shown in Table 12.Footnote 43 The dependent variable is coded as 100 or 0, so that the coefficient estimates represent the effect in percentage points for each covariate, holding all others constant. The different columns include various combinations of fixed effects, culminating in column (6) with year X jurisdiction fixed effects included (so that the model seeks to explain the decision to renounce within a jurisdiction in a year). Figure 21 below plots the coefficient estimates, scaled by the mean probability of renunciation, to show the estimated percent change in the probability of renunciation resulting from a 0 to 1 change in each binary covariate. The figure also compares the coefficient estimates when including or excluding Movers, showing similar coefficient estimates.

Scaled coefficient estimates for selected covariates, individual LPM. Notes: This figure plots the coefficient estimates for selected covariates of the fully saturated linear probability model reported in column 6 of Table 12 (excluding Movers) and Table 13 (including Movers). The estimates are scaled by the mean dependent variable to show the estimated effect on the probability of a given type of expatriation, in percent. 95% confidence intervals using standard errors clustered by year and jurisdiction are shown around each point estimate. The covariate for filing a gift tax form is excluded from this figure because it dominates the others, with a scaled point estimate suggesting it is associated with a more than 500% increase in the probability of renunciation

The results suggest several individual characteristics connected with the decision to renounce citizenship. Filing a gift tax form, which is relatively rare in general, is very strongly associated with renunciation (consistent with a pattern I demonstrate later related to the net worth threshold for covered expatriate designation). The presence of Schedule C income is positively associated with renunciation, while having a higher wage share of income is negatively associated with renunciation (interesting given the pattern shown in Appendix A that Droppers had relatively high wage income, suggesting that those renouncing had both high wage income and non-wage income). Having a positive tax liability is negatively associated with expatriation, although this is only statistically significant at standard levels in one specification. However, if the association is truly negative, this would be consistent with an explanation in which long-term foreign resident U.S. citizens drop citizenship because of increased compliance costs (filing new and more complicated forms), not because of tax liability itself.

Most relevant to the option value framework, the results show that age is significantly, and positively, correlated with the decision to renounce. This is consistent with the prediction that as individuals age, the time value of their option on U.S. citizenship decreases, leading to lower values for that option and renunciation becoming more common.

IGA difference-in-difference analysis

Section 4.3 discuss the effects of FATCA, and how individuals living in jurisdictions that signed IGAs were more likely to experience increased compliance costs, and thus be more likely to renounce citizenship. I test this relationship using a difference-in-differences approach, relying on the same individual-year level data as in the previous section, as follows:

where \(IGA\) is an indicator equal to one for jurisdictions that signed an IGA, \(Post\) is an indicator for tax years 2010 or later (renunciations in 2011 or later), and \(IGA*Post\) is their interaction. As before, Renounce is an indicator equal to 100 if an individual renounces citizenship the following year, and 0 otherwise.

The main regression results are shown in Table 14 and confirm that the probability of renunciation increased relatively more after FATCA for individuals living in IGA-signing jurisdictions. We can also go one step further and take advantage of a distinction between the two types of IGAs, called Model 1 and Model 2. Under Model 1, firms report to their local tax authorities, who then report to the IRS. Under Model 2, firms report information from their consenting account holders’ accounts directly to the IRS, while information from non-consenting account holders is sent through their local tax authorities. The majority of signed IGAs follow Model 1. BTW show specifically that information exchange quality is higher for Model 1 jurisdictions relative to Model 2 and Non-IGA jurisdictions. The result is driven by Model 1 jurisdictions; Model 2 jurisdictions saw no post-FATCA increase.

The results shown in Fig. 5 and Table 14 are robust to various alternative data filters and variable definitions. Including Switzerland, excluding “Movers”, or excluding jurisdictions with fewer than 100 U.S. tax filers does not affect the results (see Table 15 and Figure 22). Alternative IGA definitions also do not affect the results, whether restricting to only IGAs signed through 2015 or 2017, or also including unsigned but agreed-in-substance IGAs (see Table 16).

Annual share renouncing, alternate specifications. Notes: This figure plots the number of individual renouncing each year as a share of prior-year U.S. tax filers, from either IGA or non-IGA jurisdictions. The four rows correspond to four different definitions of “IGA jurisdictions”: including those signed through 2019, 2017, or 2015, or adding in those with Agreements in Substance. The four columns correspond to sample definitions: the second column includes observations from Switzerland; the third column excludes Movers; and the fourth column restricts to jurisdictions with at least 100 U.S. tax filers in one year

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Organ, P.R. Citizenship and taxes. Int Tax Public Finance 31, 404–453 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-022-09767-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-022-09767-5