Abstract

This paper empirically examines whether Africa’s low corruption agenda can be achieved amid election cycles. We employ country-level data from 36 African countries covering the period 1998–2020. Using fixed effects, random effects and dynamic panel data regressions, our results suggest that in election years, increment in government expenditure is associated with higher corruption perception while increment in real GDP growth lowers corruption perception than in non-election years. On regional differences, the effect of election cycles on corruption perception was found to be greater in southern part of Africa than the rest of the sub-regions. These findings may have important implications for policy.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Political business cycles (PBC) are cycles in macroeconomic variables such as money supply, GDP growth, unemployment among others caused by election cycles (Drazen, 2004). It results from a situation where incumbent governments try to boost their popularity and, enhance their re-election chances by applying expansionary policies ahead of elections. This practice often undermines democratic institutions making them less able to control corruption (Transparency International, 2019). The Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI)Footnote 1 released by Transparency International (2018) reveals alarming correlation between democracy level and corruption. According to the results, most countries out of the 180 considered are not able to tackle corruption. Particularly, in Africa, the picture was largely gloomy where only 8 out of 49 countries from the continent score more than the 43 (out of 100) despite African leaders’ commitment to declare 2018 an anti-corruption year (Transparency International, 2019). Further analysis from the report shows that highly rated corrupt countries have low levels of democratic institutions and political rights. This, therefore, suggests that many democratic institutions are put under threat across Africa by leaders with authoritarian tendencies.

Whiles Africa needs to do more to protect citizens’ right by strengthening checks and balances, the existence of election cycles may impede this achievement. The desire of African governments to remain in power for long cause them to engage in high public expenditure ahead of elections to boost their popularity and enhance their re-election chances. In most cases, the executive arm of government influences the legislative and the judiciary arms to facilitate their re-election. All these practices undermine democratic institutions, and in turn, weak institutions are less able to control corruption (Transparency International, 2019). Africa, therefore, presents the appropriate context to investigate the impact of election cycles on corruption.

Election cycles have been noted to be largely detrimental to African economies. In particular, there is evidence that expansionary policies ahead of elections exist and affects economic growth, inflation, human development, inter alia, in Africa (see for example Block et al., 2003; Mosley & Chiripanhura, 2016; Iddrisu & Bokpin, 2018; Iddrisu & Mohammed, 2019). Iddrisu and Bokpin (2018) as well as Iddrisu and Mohammed (2019) particularly confirmed that PBC exists in Africa and that it is detrimental to economic growth and human development. On the flip side, Iddrisu and Turkson (2020) revealed a positive side of PBC as enhancing financial inclusion. However, to the author’s knowledge, little is known about how expenditure associated with election cycles affects corruption. Will it be difficult to reduce or eliminate corruption in the presence of election cycles? Employing country-level data from 36 African countries and focusing on two macroeconomic variables (government spending and real GDP growth), this paper examines the above question in Africa where corruption perceptions are very high. In particular, the study investigates whether cycles in macroeconomic variables caused by election cycles influence corruption perception in Africa. Secondly, whether such cycles affect corruption perception differently across the African sub regions.

The following key results were found; Increment in government spending in election years was associated with higher corruption perception while increment in real GDP growth lowers corruption perception in Africa. These were consistent across the African sub-regions, albeit different magnitudes, with Southern Africa on the lead. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 provides overview of the literature comprising the link between political business cycle and corruption and reviews existing literature on political business cycle. Section 3 presents specifications of corruption perception, measures of cycles in the selected macroeconomic variables, and the control variables used. It also contains descriptive statistics and the methodology employed. Section 4 contains the empirical analysis. In Sect. 5 the study concludes.

2 Overview of related literature

2.1 The link between PBC and corruption

The works of Nordhaus (1975) and Tufte (1978) are the ground-breaking works on political business cycle and are built on the assumption that voters based their voting decisions on the pre-electoral economic performance of the government. Subsequently, other studies including Reid (1998), Alesina et al. (1992), Kohno and Nishizawa (1990) supported this assumption in advanced democracies that governments influence economic policies ahead of elections, resulting in the increment of fiscal deficits in election year and high inflation after elections. Thus, manipulations of the economy in pre-election does not necessarily strongly affect real growth rates, nevertheless, governments tend to implement pre-electoral expansionary fiscal policy, resulting in fiscal imbalance and inflation. As voters are unable to gather information on the incumbent government’s de facto competence, they tend to assess it using its past policy performance and base their voting decision on it. The incumbent government realizing this try to manipulate economic policies ahead of elections to prove their capability. This leads to fiscal deficits in an election year and high inflation after elections.

Political business cycle arguably undermines democratic institutions. Incumbent governments’ interference in the activities of central banks, the executive arm of government influencing the judiciary and legislative, among others (to brighten their re-election chances), are some of the ways through which democratic institutions can be weaken. And weak democratic institutions as noted by the Transparency International (2019) are less able to control corruption. There is largely negative empirical relationship between democracy and corruption. Warren (2004) noted that, usually, corruption in a democracy indicates a deficit of democracy. In a joint impact analysis of democracy and press freedom on corruption, Kalenborn and Lessmann (2013) reveal that democracy only works in controlling corruption if there is a certain degree of press freedom in a country. Even though, Rock (2009) reported a non-linear relationship (inverted U shape) between age of democracy and corruption, occurring early in the life of new democracies, several other studies found a well-established inverse relationship between corruption and democracy, where high levels of corruption undermine democracy and vice versa (see for example Fjelde & Hegre, 2014; Kalenborn & Lessmann, 2013; Mohtadi & Roe, 2003; Treisman, 2000). In particular, Fjelde and Hegre find that low-corruption democracies are more stable than high-corruption ones. Corruption damages the rule of law and social justice by diverting rare resources from disadvantaged people in society (Holmes, 2006; Jong-sung & Khagram, 2005). In sum, political business cycle is inversely related to democracy where higher levels of PBC undermine democracy. There is also an inverse relationship between democracy and corruption where weak democratic institutions are less able to control corruption. Thus, by transitivity, there is an inverse relationship between political business cycle and corruption.

2.2 Review of related literature

From existing literature, PBC and its relationship with several other macroeconomic variables are firmly established. However, literature on its effect on corruption is dearth to the best of the author’s knowledge. This section reviews empirical literature of the existence of political business cycle and its effect on other macroeconomic variables. In a single country studies, the study of Efthyvoulou (2011) proposes a shift in economic and partisan policies outcome and noted these outcomes declines with the progression of globalization. Further, he documented in particular a shift in fiscal balance subcomponents to be driven by shift in the electoral fortunes. Funashima (2016) in the USA found that except in the 1990s, the Federal Reserve always reduces the funds rate ahead of presidential elections. He noted that such a political manipulation is affecting output in various periods significantly. These findings were however, attributed to changes in the preferences of voters. Enkelmann and Leibrecht (2013) analyzed the existence of PBC and found that election cycles existed in the Eastern European countries. Finally, the argument of Higashijima (2016) is that when authoritarians are able to signal popularity through polls reliably, they have a strong desire to overspend ahead of the polls. He further examined PBC in authoritarian regimes and noted that in dictatorships, fiscal deficits are more noticeable than in their counterpart democratic regimes. His study again posited that autocrats with semi-structured competitive but less fraudulent elections are quick to apply expansionary fiscal policies ahead of elections.

In Africa, Block et al. (2003) demonstrates the presence of PBCs in Sub-Saharan African countries. He discovered electorally timed systematic interventions in 9 cases of monetary and fiscal policy in Africa. Similarly, Block et al. (2003) find in African countries that PBCs are found in countries where a multiparty system exists and moderate in countries where ‘founding’ elections exist. Again, Mosley and Chiripanhura (2016) posited heterogeneity in PBCs in Africa and that they rarely occur in ‘dominant-party systems’ in which the pre-election incentive slightly confers political advantage. They further noted that election cycles do not necessarily cause institutional damage in countries they exist. Nonetheless, whether it causes damage or not, it is less dependent on whether an electoral cycle exists, rather it depends on whether this cycle strengthens or reduces fears of unfair resource allocations. Iddrisu and Bokpin (2018) found in Africa that PBC is present and hinders economic performance in African nations. In a related study in Africa, Iddrisu and Mohammed (2019) found political business cycle to worsen human development. Following the literature above, the relationship between political business cycle and other outcome variables such as economic performance and welfare has been established. The knowledge gap regarding election cycles’ relationship with corruption is clear. The current study, therefore, seeks to verify whether such cycles encourage corruption in the African continent.

3 Evaluating methodology

3.1 Data

This study employs country level unbalanced panel data. Series are yearly, covering 23 years (1998–2020) for a sample of 36 African countries. The sample includes all African countries for which annual data is available, particularly for Corruption Perception Index (CPI), the period is also influenced by the CPI data (CPI data started from 1998). Data on CPI is sourced from Transparency International database; Political rights Rating data is from freedom house database; Election and pre-election dummies are computed by authors while data on the rest of the variables are from the WDI of the World Bank.

3.2 Variable measurements

The study measures corruption perception using the corruption perception index from transparency international. The index provides ranking for 180 countries according to their perceived levels of public sector corruption observed by businessmen and experts. using a scale of 0 to 100, 0 denoting highly corrupt and 100 represents very clean. Therefore, the higher the index, the less corrupt the country.

Following the work of Iddrisu and Mohammed (2019), Iddrisu and Bokpin (2018), we use the interaction between election cycle (ELE) and government expenditure and with real GDP growth to measure cycles in macroeconomic variables. The ELE dummy is one (1) in a presidential election year and zero (0) otherwise and Government expenditure is measured by the general government final consumption expenditure as a percentage of GDP while real GDP growth is in annual percentage.

We also control for variables that may affect the dependent variable (corruption perceptions). These controls include macroeconomic, financial, and political environments characteristics. For the controls, PREELE dummy is one (1) in a pre-election year, and zero (0) otherwise. Political right rating (PRR) is used to measure freedom for political activism. Generally, African countries have low level of institutional efficiency which has an adverse effect on corruption perceptions. The PRR variable assigns high scores to less freedom countries and low scores to countries with freer environments. Gross fixed capital formation as a percentage of GDP is used to measure national investment. Infrastructure is represented by fixed telephone subscription per 100 people. Domestic credit to private sector as a percentage of GDP measures financial sector development. The rate of inflation based on the GDP deflator is also controlled for. Gross secondary school enrolment is used to measure education level and expenditure in health as a percentage of GDP is used to measure health investment.

3.3 Summary and descriptive statistics

Table 1 presents the mean values of the variables used in the study. Variables are categorised by non-election, pre-election, and election years.

From Table 1 the mean values of corruption perception index is about 15.68 in election year with about 15.83 and about 15.22 in pre-election and non-election years respectively. These suggest that on average corruption perceptions in Africa are high in non-election years, decreases in pre-election years and then increase again in election years. This may not necessarily be a cycle but follows logic because if the incumbent government is perceived to be corrupt over the years, it may want to redeem its image in pre-election years by being less corrupt, however, in a quest to win back power in election years it may engage in corrupt practices again thereby raising corruption perceptions. Government expenditure in election years for the full sample averaged about 13.23 percent of GDP, about 12.63 percent of GDP in pre-election years and about 12.81 percent of GDP in non-election years. Similarly, real GDP growth recorded an average percentage of about 4.25 in election years, about 4.39 percent in pre-election years and about 4.00 percent in non-election years. Clearly, on average African governments spend more and record higher real GDP growth in election years than non-election years, thus, confirming incumbent government’s pre-electoral manipulations of the economy which increase macroeconomic variables in election years to brighten their re-election chances. Real GDP growth may be realised because of complementary spending of oppositions parties rather than incumbent government’s spending alone. Government’s spending in election years is argued to often create fiscal imbalance and high inflation after elections (Alesina et al., 1992; Kohno & Nishizawa, 1990; Reid, 1998), this is confirmed by the average inflation figures from our data where higher values of about 17.40 percent is recorded in non-election years compared to about 5.98 percent in election years. The existence of political business cycles in Africa is therefore confirmed from our data.

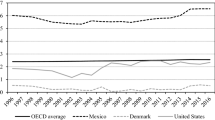

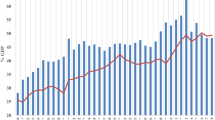

This trend is consistent across African sub-regions albeit with different magnitude except for central and north African countries where the reverse is true with government expenditure in non-election years being more than election years, West Africa, and Southern Africa where real GDP growth in non-election years is more than election years. The higher government spending with a corresponding lower real GDP growth in West Africa and Southern Africa in election years reflects the argument that economic manipulations in pre-election does not necessarily strongly affect real growth rates (Reid, 1998).Footnote 2 Figure 1 shows the pictorial representation of the data on government expenditure, real GDP growth and inflation portraying evidence of the existence of PBC. This serves as an up-to-date evidence supporting existing empirical evidence including Block (2002), Iddrisu and Bokpin (2018), Iddrisu and Mohammed (2019) among others confirming the existence of PBC in Africa. The novelty of this study is to assess the influence of cycles in some macroeconomic variables on corruption perception by examining how government spending and real GDP growth in election years affect corruption perceptions in Africa.

3.4 Model and estimation strategy

To assess the corruption perception and election cycles relationship, the study examines the effect of government expenditure and real GDP growth in election years on corruption perception in Africa. We referred to the works of Iddrisu and Bokpin (2018); Iddrisu and Mohammed (2019) and estimate the following model.

where \(CP{I}_{c,t}\) is corruption perception index of country \(c\) at period \(t\), \({ELE}_{t,c}\) is the election period of country \(c\), \({PREELE}_{c,t}\) is the pre-election period of country \(c\), \({Gov. exp}_{c,t}\) is government expenditure of country \(c\) at period \(t\), \(\left({ELE}_{c,t}*{Gov. exp}_{c,t}\right)\) is the interaction between election dummy of country \(c\) and government expenditure of country \(c\) at period \(t\), \({GDPgrowth}_{c,t}\) is the real GDP growth of country \(c\) at period \(t\), \(\left({ELE}_{c,t}*{GDPgrowth}_{c,t}\right)\) is the interaction between election dummy of country \(c\) and real GDP growth of country \(c\) at period \(t\). The variable \({X}_{i,j}\) are a set of \(\{K\}\) covariates which includes (i) national investment (gross fixed capital formation), (ii) financial development (domestic credit to private sector), (iii) political rights rating, (iv) infrastructural development (fixed telephone subscription per 100 people). \(\beta^{\prime}\)s are the parameters to be determined. \({\alpha }_{c}\) is country fixed effects accounting for unobserved country differences.\({\rho }_{t}\) represent year fixed effects which accounts time differences. \({\pi }_{c,t}\) is the random error term.

Equation (1) is estimated using fixed and random effects techniques. In fixed and random effects models, omitted variable bias is eliminated by measuring change within groups across time. For fixed effects method, the assumption is that the regressors have some correlation with the individual specific effects, therefore, the effect of time-invariant characteristics is removed to assess the net effect of the covariates on the dependent variable (corruption perceptions). With the random effects, it is assumed that the regressors are not correlated with individual specific effects. Additionally, with the fixed effects model, inference outside the data set is not considered. Inferences can however be extended to a larger population with the random effects since it assumes normal distribution of the data set. Again, with random effects, we can include time-invariant variables in the model, however, in fixed effect model, the intercept absorbs such variables.

The Hausman test was performed ahead of the data analysis to choose between the fixed and the random effects models. The P-values of the Hausman test was significant (p-value = 0.000) suggesting the presence of endogeneity bias in the model and choosing the fixed effects model over the random effects which provides consistent estimates in this case (see results in Table 2). Another methodological concern is the possible existence of reverse causality between corruption and government expenditure and real GDP growth in election years. Again, it is highly recognized and established that corruption negatively affects economic growth and investments in the economics literature (see for example Campos et al., 1999; Mauro, 1995; Coupet Jr, 2001). Therefore, the presence economic growth and investment proxies as exogenous variables introduces endogeneity bias in the fixed and random effects models. Therefore, as a robustness check and to account for any potential endogeneity bias in the model, the Linear Dynamic Panel Data (XTDPD) technique is also used to estimate Eq. (1) and as a sole estimator for the sub-regions.

The linear dynamic panel-data (xtdpd) model includes as covariates p lags of the outcome variable and contain unobserved panel effects (random or fixed). The unobserved panel effects correlate with the lagged outcome variables by construction, making the standard estimators differ. By using the Arellano–Bond (1991) (xtabond) or the Arellano–Bover (1995); Blundell–Bond (1998) (xtdpdsys) estimators, xtdpd constructs a dynamic panel-data model. In the mist of more complex syntax, xtdpd compared to xtabond or xtdpdsys can fit models with low-order moving-average correlation in the idiosyncratic errors or predetermined variables with a more complex structure.

The functional form of the model as used in this paper is as follows.

where \({CPI}_{c,t}\) is the corruption perception index used as the dependent variable. \({\beta }_{1}\),…,\({\beta }_{p}\) are \(p\) parameters to be estimated. \({X}_{c,t}\) is a \({1\times k}_{1}\) of strictly exogenous covariates, which included government expenditure, GDP growth, financial development, infrastructural development, and investment. \({\beta }_{1}\) is a \({k}_{1}\times 1\) vector of parameters to be estimated. \({W}_{c,t}\) is a \({1\times k}_{2}\) of predetermined covariates, which included election and pre-election cycles and political rights rating. \({\beta }_{2}\) is a \({k}_{2}\times 1\) vector of parameters to be estimated. \({\alpha }_{c}\) are the panel-level effects (which may be correlated with \({X}_{c,t}\) or \({W}_{c,t}\)), and \({\pi }_{c,t}\) are i.i.d. or come from a low-order moving-average process, with variance \({\sigma }_{\pi }^{2}\).

The study also used robust standard errors for the Fixed and Random effects models to correct heteroscedasticity and autocorrelation. Here, the standard errors are clustered by country which is appropriate when using panel data. A bias-corrected robust estimator derived by Windmeijer (2005) and known as the WC-robust estimator for two-step VCEs from GMM estimators is implemented in xtdpd.

4 Empirical results

4.1 Effects of election cycles on corruption

The results shown in Tables 2 and 3 are obtained from estimating Eq. (1) using the fixed effect (FE), random effect (RE) and dynamic panel data techniques. The outcome of the Hausman test recommends the use of the fixed effect model. Therefore, we concentrate on the parameter estimates obtained under the FE estimator, and the dynamic panel estimator since it accounts for endogeneity. We apply the robust clustered standard errors to correct for the presence of heteroskedasticity and serial correlation.

In Table 2 above, the results of the election cycle dummy in columns 1 and 2 indicate that corruption perception is low (i.e. CPI is high) in election years as compared to non-election years. This is however not robust as it is not statistically significant for the dynamic panel estimate in column 3. Also, the coefficient of government expenditure is positive and significant in column 3 indicating that higher government spending tends to decrease corruption perceptions (increase the corruption perception index). More importantly, despite the positive effects of both the election dummy and government expenditure on CPI, the coefficient of the interactive term (ELE*Gov exp) is negative and statistically significant across all regressions, indicating that government expenditure in election years tend to increase corruption perception (i.e. decrease the corruption perception index) compared to non-election years. However, the results of the interaction term (ELE*GDP growth) suggest in column 3 that real GDP growth in election years tend to decrease corruption perception (i.e. increase the corruption perception index) compared to non-election years. To be specific, the results in column 3 (the dynamic panel model) indicate that for every extra percentage point increase in government expenditure, corruption perceptions increase by 0.338 units in election years than in non-election years, while a percentage point increase in real GDP growth decreases corruption perceptions by 0.785 units in election years compared to non-election years, all else equal. To conclude, our results support the hypothesis of a negative and significant impact of (ELE*Gov exp) on the corruption perception index (i.e. positive impact on corruption perception) and a significant positive impact of (ELE*GDP growth) on the corruption perception index (i.e. negative impact on corruption perception). Thus, in Africa, higher election year’s government spending increases corruption perception, but when this spending translates to real GDP growth, corruption perception decreases.

Table 3 presents the results that explore regional differences within the African region. These sub-regions are the West Africa, East Africa, Southern Africa, Central Africa, and North Africa. However, due to fewer representation of North and Central African countries in the sample, we treat them as one sub-region. Because the dynamic panel accounts for endogeneity bias in the model, we presented only its estimated results.

From Table 3, the coefficients of the interactive term (ELE*Gov exp) are negative across all columns but statistically significant at various conventional significance levels for East Africa, Central and North Africa, and Southern Africa, suggesting that government spending in election years is associated with higher perception of corruption in these regions, and consistent with the findings of the full sample. It is however not significant for the West African sub region. Also, the results of the interactive term (ELE*GDP growth) were only significant for Central & North Africa and Southern Africa (not significant for West Africa and East Africa) thereby confirming the earlier findings for the aggregated sample that real GDP growth in election years is associated with low perception of corruption. Indeed, there are regional differences, whereas there was no significant evidence of either government spending or real GDP growth in election years affecting corruption perception in West Africa, the effect of government spending and real GDP growth in election years on corruption perception were more pronounced in Southern Africa, thus, the magnitude was much higher in Southern Africa than the rest of the regions. To test the equality of the coefficients of the interaction terms (ELE*Gov exp) and (ELE*GDP growth) across the sub-regions, we provided Z-valuesFootnote 3 in Table 4.

The Z values in Table 4 for the coefficients of (ELE*Gov exp) and (ELE*GDP growth) across the sub-regions were all not significant (below 1.96), except between Southern Africa and the rest. Thus, we can reject the null hypothesis that \({\beta }_{S}={\beta }_{W,E,C\&N}\), and conclude that cycles in government spending and real GDP growth affects corruption perception in Southern African countries more than the rest.

5 Conclusion and recommendations

Cycles in macroeconomic variables are often caused by election cycles, when incumbent governments try to boost their popularity and enhance their re-election chances by applying expansionary policies ahead of elections. Particularly in Africa, incumbent governments are always noted to be power drunk. This has been demonstrated in many instances where most incumbent governments try to manipulate the countries’ constitution to legalise their stay in power for a long time. In other instances, they resort to the use of public resource for political gains. This paper assesses the effect of cycles in macroeconomic variables caused by election cycles on corruption perceptions in Africa and whether there are regional differences within Africa. The paper measured corruption perception using the corruption perception index from transparency international. To measure cycles in macroeconomic variable, we interacted government expenditure and real GDP growth with the election dummy ‘ELE’ to get (ELE*Government expenditure) and (ELE*GDP growth). The ELE dummy takes the value one (1) if there have been presidential elections in that year and zero (0) otherwise. To get a minimum error term, we controlled for the phenomena that affect corruption perception. Using Eq. (1), we estimated an unbalanced panel model using data from 36 African countries over the period 1998–2020. We presented robust estimation results of the Fixed Effect, Random Effect, and the Dynamic Panel Data models. The robust estimation was to control for serial correlation and heteroskedasticity. Following the Hausman test rejection of the null hypothesis of no correlation between the unobserved heterogeneity and the regressors suggesting the appropriateness of the Fixed Effect model over the Random Effect model, we concentrate on the results from the Fixed Effect model and subsequently on the dynamic panel results because of the issue of potential endogeneity bias in the model.

We found a negative and significant relationship between the interactive term (ELE*Government expenditure) and corruption perception index indicating that, increment in government spending in election years is associated with higher corruption perception compared to non-election years. However, the interaction term (ELE*GDP growth) was positive and significant suggesting that increment in real GDP growth lowers corruption perception in election years compared to non-election years. On the regional differences, whereas there was no significant evidence of either government spending or real GDP growth in election years affecting corruption perception in West Africa, the effect of government spending and real GDP growth in election years on corruption perception were more pronounced in Southern Africa. The conclusions and policy recommendations from the findings are as follows.

The study concluded that attaining low corruption perception will be difficult in Africa if government spending in election year is not controlled. This is particularly true for the southern African countries. Thus, African governments’ low corruption agenda will be very difficult to attain in the presence of election cycles. The policy recommendations are that if the region is committed to the fight against corruption, policies should design to ensure that incumbent governments spend appropriately and at the right time by the right person and not just for the purpose of their re-election. This is possible if independent committees are established to always monitor government spending or domestic policymakers limiting borrowing by an incumbent in pre-election and election years. Sensitising electorates on the dangers political business cycle and making an informed choices can also help. The main limitation of this paper has to do with the missing observations in the dataset. This has reduced the number of countries and observations used in estimating the results. Nonetheless, the paper is still useful to inform policy.

Data availability

Data and material is available upon request.

Notes

The index ranks 180 countries according to their perceived levels of corruption in the public sector by businessmen and experts using a 0 to100 scale, 0 denotes highly corrupt and 100 is very clean.

Appendix 1 presents the extent of correlation among the key variables used in the study. The correlation between the independent variables is generally low (< 0.70). The low correlations between the variables suggests less collinearity among them which will not cause estimation issues.

References

Alesina, A., Cohen, G. D., & Roubini, N. (1992). Macroeconomic policy and elections in OECD democracies. Economics and Politics, 4(1), 1–30.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51.

Block, S. A., Ferree, K. E., Singh, S. (2003). Multiparty competition, founding elections and political business cycles in Africa. Journal of Development Economics, 12, 444–468.

Block, S. A. (2002). Political business cycles, democratization, and economic reform: the case of Africa. Journal of Development Economics, 67, 205–228.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Campos, J. E., Lien, D., & Pradhan, S. (1999). The impact of corruption on investment: Predictability matters. World Development, 27(6), 1059–1067.

Clogg, C. C., Petkova, E., & Haritou, A. (1995). Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. American Journal of Sociology, 100(5), 1261–1293.

Coupet, E., Jr. (2001). Corruption and economic growth: theory and international evidence. University of Illinois at Chicago.

Drazen, A. (2004). Political economy in macroeconomics. Princeton University Press.

Efthyvoulou, G. (2011). Political cycles under external economic constraints: evidence from Cyprus. Journal of Economics and Business, 63, 638–662.

Enkelmann, S., & Leibrecht, M. (2013). Political expenditure cycles and election outcomes: Evidence from disaggregation of public expenditures by economic functions. Economics Letters, 121, 128–132.

Fjelde, H., & Hegre, H. (2014). Political corruption and institutional stability. Studies in Comparative International Development, 49(3), 267–299.

Funashima, Y. (2016). The Fed-induced political business cycle: Empirical evidence from a time–frequency view. Economic Modelling, 54, 402–411.

Higashijima, M. (2016). Political Business Cycles in Dictatorships. 早稲田大学高等研究所 (WIAS).

Holmes, L. (2006). Rotten states? Corruption, post-communism, and neoliberalism. Duke University Press.

Iddrisu, A. G., & Bokpin, G. A. (2018). Political business cycles and economic growth in Africa. Journal of Economic Studies, 45(4), 760–772.

Iddrisu, A. G., & Mohammed, J. I. (2019). Is Political business cycles an enemy to human development? Empirical evidence from Africa. Journal of Economic and Political Studies., 7(3), 337–351.

Iddrisu, A. G., & Turkson, F. E. (2020). Political business cycles, bank pricing behaviour and financial inclusion in Africa. Cogent Economics and Finance, 8(1), 1762286.

Jong-sung, Y., & Khagram, S. (2005). A comparative study of inequality and corruption. American Sociological Review, 70(1), 136–157.

Kalenborn, C., & Lessmann, C. (2013). The impact of democracy and press freedom on corruption: Conditionality matters. Journal of Policy Modeling, 35(6), 857–886.

Kohno, M., & Nishizawa, Y. (1990). A study of the electoral business cycle in Japan: Elections and government spending on public construction. Comparative Politics, 22(2), 151–166.

Mauro, P. (1995). Corruption and growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(3), 681–712.

Mohtadi, H., & Roe, T. L. (2003). Democracy, rent seeking, public spending and growth. Journal of Public Economics, 87(3–4), 445–466.

Mosley, P., & Chiripanhura, B. (2016). The African political business cycle: Varieties of experience. The Journal of Development Studies, 52, 917–932.

Nordhaus, W. D. (1975). The political business cycle. The Review of Economic Studies, 42(2), 169–190.

Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology, 36(4), 859–866.

Political rights Rating. Freedom house database. https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world.

Reid, B. G. (1998). Endogenous elections, electoral budget cycles and Canadian provincial governments. Public Choice, 97(1), 35–48.

Rock, M. T. (2009). Corruption and democracy. The Journal of Development Studies, 45(1), 55–75.

Transparency International (2019). Sub-Saharan Africa: Undemocratic regimes undermine anti-corruption efforts. A continuous struggle in fighting corruption across the region. https://www.transparency.org/en/news/cpi2018-subsaharan-africa-regional-analysis.

Transparency International database. Corruption Perception Index. (2018). https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi#.

Treisman, D. (2000). The causes of corruption: A cross-national study. Journal of Public Economics, 76(3), 399–457.

Tufte, E. R. (1978). Political control of the economy. Princeton University Press.

Warren, E. M. (2004). What does corruption mean in a democracy? American Journal of Political Science, 48(2), 328–343.

World Bank’s World Development Indicators data bank https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators.

Funding

No funding available.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest exist.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I am thankful to Roger D. Congleton for his valuable comments, and to Lin Wood for proofreading the paper. Any mistakes or omissions are my responsibility.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Iddrisu, A.G. Election cycles and corruption perception in Africa. Const Polit Econ 34, 553–571 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-022-09388-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10602-022-09388-4