“Obviously, things are very upside down at the moment.”

- Pastor in New Zealand, April 8, 2020 (NZ2)

“It really felt like we had the rug pulled out from underneath us …. I mean [church] is not a service and it’s not something to consume, it’s something that we are, and it’s all about presence. What do you do when you can’t be together?”

- Pastor in Pacific Northwest United States, February 18, 2021 (PNW4)

Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced disruption that crossed sectors, borders, and disciplinary boundaries. Among faith communities and religious leaders, numerous commentators have observed technological innovations in response to physical gathering disruptions. We outline a form of pandemic spiritual leadership that supports faith communities beyond digital innovation by combining original empirical research and a novel conceptual framework.

Purpose

Our project examined innovation through a comparative study of how faith leaders adapt religious practices during a time of disruption. While existing research on congregational responses to COVID-19 has documented sustained technological innovation, our research argues that technological innovation is only one feature of a broader catalog of innovative practices.

Methods

To generate a trans-national sample, we used purposive sampling in two distinct locations, Pacific Northwest United States and Aotearoa New Zealand. Although separated by culture and geography, a purposeful sample across these two contexts illustrated how spiritual leaders in post-Christian contexts similarly responded to the pandemic crisis. The research involved semi-structured interviewing of nineteen faith leaders from seventeen communities we observed undertaking creative adaption. A trans-national selection deepened understandings of the dynamism of the unfolding pandemic and how limits, experienced differently in diverse contexts, can be generative.

Results

Our study identified six organizing practices: blessing, walking, slowing, place-making, connecting, and localizing care. We demonstrate how the presence of God is cultivated amid local letterboxes and neighborhood crossroads and argue for an intensification of the local as markers of pandemic spiritual leadership. These interrelated spiritual practices express features of Michel de Certeau’s “pedestrian utterings,” Joseph Schumpeter’s “creative recombination” and Pierre Bourdieu's social theory. Working with Certeau, we describe pedestrian utterings as historic church practices reframed as everyday local practices. Working with Schumpeter, we describe how the six practices and the language of innovation used by participants express creative recombinations. Working with Bourdieu, we consider how disruption realigns social fields, including between individuals, congregations, and broader communities. Finally, amid social distancing, congregations proved to be an anchor in resourcing this pandemic spiritual leadership.

Conclusions and Implications

These four theoretical foci and six localizing practices provide a conceptual framework for future research into spiritual practices and religious leadership in the wake of a crisis. Confinements in space and movement can be generative of spiritual practice. For religious leaders and organizations, the research informs the cultivation of concrete practices that can encourage communities of care as part of crisis preparation. For scholars and religious practitioners alike, while pandemics enforce social separation, pandemic spiritual leadership combines attention to the local and the particular, as new forms of in-place practice emerge to sustain faith communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Religious life and spiritual practice changed in the early weeks of the pandemic. Sunday morning became a stream of online worship services. What was gathered was now scattered. Rather than drive to a church building, with the click of a button and from the comfort of their home, individuals accessed prayers, songs, and a sermon. Numerous pastors and practitioners contributed to a surge in online religion during COVID-19, with platforms like Zoom, YouTube, and Facebook used to broadcast gathered worship (O’Brien 2020; Ganiel 2020). Some commentators noted how the social distancing of the pandemic catalyzed ecclesial innovation (McGrath 2020) and argued that the rise in numbers resulting from live streaming provided new opportunities for the church in mission (Pillay 2020). However, other quantitative measures painted a more somber picture. Analysis of offerings indicates a significant decline in financial offerings (Manion and Strandberg 2020). The nature and extent of innovation for the church in a pandemic required further research.

Digital religion as innovation has been well-researched (Campbell 2005; Campbell and Garner 2016). For O’Brien (2020), these online offerings are an acceleration of a pre-existing development rather than something new. Taylor’s (2021) case study of one particular congregation suggested a coherence between existing values and online presence. Oxholm et al. (2020) interviewed twelve religious leaders in Aoteroa and documented religious innovation in virtual worship. Writing amid COVID, Tim Hutchings (2020) suggested three common reasons for online churches: “The desire to amplify, to connect, and to experiment” (61). Johnston et al. (2021) note a lack of qualitative data on the lived reality of religious leaders and communities during the pandemic. Their study of a representative sample of twenty-four United Methodist pastors described adaptations that were primarily practical, concerned with new ways of doing ministry or worship. They did note some unsettling of “taken-for-granted understandings of ‘the Church’” and called for further research (Johnston et al. 2021). While these existing studies helpfully display the spiritual and leadership practices that are emerging in this moment, they do not consider the relationship between the creativity that marks this moment and the religious values and practices that guide leaders’ service in a particular community of faith. Moreover, separate research is needed that can clarify clusters of common practices and challenges, and begin to describe the practices that cross national boundaries amid a global pandemic.

Accordingly, interviews with Christian leaders in two countries provide an opportunity to examine six organizing practices: blessing, walking, slowing, place-making, connecting, and localizing care. This paper describes how particularities give rise to creative adaptations in these everyday practices. These shared practices illustrate how the pandemic magnified global connection and opportunities for relational and spiritual rehabituation through online technologies. However, the practices that guide pandemic spiritual leadership intensify the local and particular, and leadership requires innovating in the particular places one serves. These local “makings” are coherent with, yet uniquely adapt, expressions of spiritual leadership. Combined, they demonstrate the innovative adaptability of faith leaders whose leadership invites faith communities into nimble adaptability. Moreover, as ordinary practices of a broader community, these local markings illustrate how leaders' connection to a local community invites leaders and their congregation alike to take the risk such innovative spiritual leadership requires.

Background: Definitions and Conceptual Framework

Definitions

In researching the pandemic spiritual leadership, we work with some definitions of leadership, innovation, and spiritual practices.

We understand leadership as the ability to organize collective activity in response to uncertainty. In agreement with Northouse (2019), our understanding of leadership prioritizes the relational process that guides individuals and a broader community of practice. Consequently, leadership “is not restricted to the formally designated leader in a group” (Northouse 2019: 43). Finally, spiritual leaders’ understanding of leadership and capacity to serve a given community is nurtured over time in response to a dense matrix of relationships that support their service in and to a particular community (Dykstra 2008).

Following Nancy Ammerman (2014), we understand spiritual practices as “a cluster of actions” (56) that are given meaning by social forces and the people who occupy that social field. During times of crisis and disruption, spiritual leaders serve as caretakers for their communities and mediators of meaning amid uncertainty. Accordingly, spiritual practices become a social medium by which they may care for and lead their community.

We will now develop each definition in greater detail in conversations with three social theorists, Michel de Certeau, Josef Schumpeter and Pierre Bourdieu.

Conceptual Framework

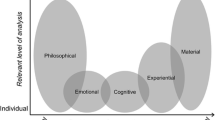

Researching pandemic spiritual leadership requires a conceptual frame that can attend to questions of creativity and adaption in relation to local and global fields of cultural production.

One significant source of conceptual resources occurs in the work of French scholar Michel de Certeau (1925–1986), considered “one of the leading theorists of cultural dynamics and of both historical and actual practice in many diverse domains of culture” (Frijhoff 2010: 78). Certeau was, by training, a historian of early modern Europe. Following the Paris Uprising of May 1968, Certeau began to study contemporary popular culture.

In The Practice of Everyday Life, de Certeau (1984) developed the concept of “pedestrian utterings” to describe how people, commonly assumed to be made passive by urban environments, are “making do,” living and walking in ways that made the city inhabitable. Certeau suggested that relationships between walking and the city are believable, memorable and other aware. Research of everyday practices insists on the believability of everyday practices as ways of making meaning (de Certeau 1984: 112–114). These meanings can be uncovered through participant interviews (1984: 114–115). Each act of local spiritual practice can be examined for other awareness, including the interconnections with local community and neighbour. “Pedestrian utterings” as believable, memorable and other aware provide theoretical resources to reflect on how spiritual practices might be deployed in times of pandemic constriction.

Another strand of Certeau’s work speaks to local spiritual practices in times of change. In The Mystic Fable (Certeau 1992) and an essay on “Mystic speech” (Ward 2000), Certeau outlines how the mystic spirituality of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries attended to God in places of suffering and loss. Amid plagues and political turmoil, Certeau argued for the value of confinement, as the mystics used language of castle and enclosed garden to describe spiritual intensification (Ward 2000: 204). Certeau argued that the mystics were innovating, not by pioneering something new. Rather they were innovating by offering “a different treatment of the Christian tradition,” “a new space, with new mechanisms” that reimagined how God might be experienced (Ward 2000: 188–189). Innovation in times of constriction occurs through creative adaptions of existing Christian traditions, in ways that reconciled the particularity of place and the universality of a shared solidarity with God (Ward 2000: 194).

Harvard economist Joseph Schumpeter, complements Certeau’s body of work. Schumpeter defined entrepreneurship as ‘the carrying out of new combinations’ and innovation as the act of creative recombinations, in which “the new combination must draw … from some old combinations” (Schumpeter 1934: 74; 68). Schumpeter’s Theory of Economic Development, published in German in 1911 and English in 1934, included a chapter devoted to social change. Schumpeter understood the entrepreneur as engaging in creative construction, a generative activity focused on new combinations, in both social and economic realms (1934: 86). Five types of innovation are described that include new organisations as well as new economic combinations (Schumpeter 1911: 66). Innovation as creative recombinations has been particularly fruitful in analysing innovation in contexts of social change. Schumpeter’s insights have been foundational in framing innovation as a collective and dynamic interplay between different actors (Lubberink et al. 2018). Social innovations are new combinations that “meet social needs and create new social relationships or collaborations” (Murray et al. 2010: 3). Hence social entrepreneurship can be understood as “the creation of social value and the pursuit of social change” through “the process of combining resources in innovative ways for the pursuit of opportunities for the simultaneous creation of both social value and economic value that manifests in new initiatives, products, services, programs or organisations” (Newth and Woods 2014: 193; 194). Schumpter’s understanding of innovation as creative recombinations provides ways to think theologically about socially responsible mission (Woods and Taylor 2021).

We see resonances between Schumpeter’s understanding of innovation as creative recombinations and Certeau’s theorization of new treatments of existing Christian traditions as mystics innovating in offering different treatments of the Christian traditions. The invitation is to examine how constrictions become new spaces in which spiritual practices are reimagined by creative adaptions of existing Christian traditions.

Pierre Bourdieu extends Certeau’s and Schumpeter’s body of work. Bourdieu’s notion of habitus as the “systems of durable, transposable dispositions … which generate and organize practices and representations that can be objectively adapted” locates practices as knowledge in specific social settings (Bourdieu 1990: 53). As Bourdieu observed in Practical Reason (1998), to think in terms of “structure” (35) requires considering the broader “symbolic space” (1) in which practices find their coherence. Symbolic spaces, comprised of relational and habitual properties, provide mediums (e.g., language, social structures, values) to imbibe ordinary practices with symbolic significance. While practices remain local, they also find their broader symbolic significance when embedded in a broader “social fields” of cultural production.

The epistemological foundation for Bourdieu’s work lies in his understanding of the social world as a relational space in which social encounters construct and transmit meaning (Hilgers and Mangez 2015). Social fields represent the historical and social loci in which individuals and groups transmit values, construct symbolic systems that provide meaning, determine the boundaries that organize social life, and engage in a struggle for power (Bourdieu 1990). Social fields invite individuals to grasp “particularity in generality, and generality in particularity” (Bourdieu 1990: 141). The concept also requires consideration of the particular practices that animate social life and the broader patterns that convey meaning and cohesion. Moreover, individuals may identify and examine social fields through social analysis that considers the structure of relations that contribute to and support habituated forms of social activity. These relations that organize fields may be “invisible or unseen at first glance” and exist both between “individual persons” and those “collected persons” (Bourdieu 1990: 191). When paired with Certeau and Schumpeter, Bourdieu’s conceptual framework provides theoretical resources for studying how the local and global combine to produce innovations in cultural production.

Together, Certeau, Schumpeter and Bourdieu invite those studying pandemic spiritual leadership and innovation practices to attend to the local of “pedestrian utterings.” They suggest that innovation can be framed as the “creative recombination” of spiritual practices, in ways that remain alert to how fields are changing in times of global constriction. Accordingly, our research considers how six everyday practices are embedded in a broader field of cultural production. Moreover, we demonstrate how the pandemic spiritual leadership we describe combines individual and collective activity, drawing the entire faith community into the creative work leaders envision. The data suggest that everyday practices that grounded the life of faith exist in imaginative relationships with the broader field of social practices reconfigured in a pandemic.

Methods

We developed a purposeful sample of pastors and ministry leaders from Aotearoa New Zealand and the Pacific Northwest United States to explore the shared practices that crossed national borders and distance during a global pandemic. Individual leaders were the primary unit of analysis. Given the constraints of data collection during the pandemic, we could not visit interview subjects in person and observe the leadership practices they described. Instead, our recruitment combined purposeful and convenience sampling technique. As a purposeful sample, our interviews included variations by denomination and gender. As a convenience sample, individuals were invited to participate in this trans-national study based either on proximity—for the New Zealand sample—or participation in previous research—for the Pacific Northwest sample. In order to initiate and complete this research during a time of distance and heightened collective anxiety, a combination of a purposeful and convenience sample ensured access and variation in the data. However, this model does represent a limitation of this research. All research was conducted according to established guidelines for ethical research in these contexts.

The two regions presented in this study represent two distinct geographic locales with some similar cultural and religious climates to permit trans-national comparison. New Zealand, or Aotearoa in the indigenous language of Māori, is a region in the South West Pacific that includes some 5 million individuals in two main islands and a land size of 103,360 square miles. The Pacific Northwest, a region of the United States that includes Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, is a region in the Northwest corner of the United States that includes more than 13.7 million people over 253,312 square miles. Furthermore, each region represents a clearly defined geography that includes cultural and geographic boundaries for this study.

These two contexts provided interesting sites for trans-national comparison, given they share two common cultural feature: common language and a post-Christian climate for innovation. Although two major cities in these respective regions—Wellington, NZ, and Seattle, WA—are separated by more than 7240 miles (11,650 km), the marginal place of religion in a post-Christian context provides cultural similarity to invite comparison (Killen and Silk 2004; Silk 2019). As Benac (2022), a scholar of religion in the Pacific Northwest, queried: “In a region researchers have dubbed the ‘None Zone’ is it possible to retain a sense of vital Christian witness, much less nurture durable forms of Christian organization and education?” In New Zealand, the church has experienced steady decline (Ward 2013) and is challenged to adapt to a post-Christian social climate. In both contexts, the marginal position of religion invites creativity. When religion is expressed "at the edge," it invites creative recombinations of existing practices (Bramadat et al. 2022). English is a common language across both contexts that enables the analysis of innovations within the limits of pandemic spiritual leadership. Accordingly, in both contexts, religious innovation and spiritual leadership occur within particular places that provide cultural and religious similarities that enable comparison.

We constructed a sample based on researchers’ access to networks of religious leaders within each region. In order to explore pandemic spiritual leadership in a time of heightened uncertainty, researchers required a level of trust with participants, which was drawn from previous research or service within each region. We also constructed the sample to include a similar composition across each sub-population. Within each sample context, the research sought participants from across each geography to construct a sample that included similar variations in gender and denominational affiliation for each sub-population. We intentionally stratified our sample to distinguish between reformed and non-reformed participants. Table 1 below summarizes the composition of the New Zealand (NZ) and Pacific Northwest (PNW) samples. The table intentionally excludes gender in order to preserve anonymity for participants.

Two researchers conducted semi-structured interviews while participants were in lockdown in each context. For New Zealand participants, interviews occurred between 6 April 2020 and 18 June 2020. For Pacific Northwest participants, interviews took place between 14 December 2020 and 18 February 2021. Reflecting our trans-national research design, participants' experience of lockdown at the timing of the interviews provided a corresponding experience across these two places for cross-cultural comparison. While the lockdown was initially more severe in New Zealand, it lifted sooner; meanwhile, participants in the PNW sample were still under lockdown during the time of these interview. Although individuals were interviewed at different times of the pandemic, the local state climate in each context during the time these interviews were conducted was comparable. Although the pandemic was global in scale, local and regional variation entail that the severity of lockdown was experienced at different times in different places. This variation justifies the two cycles of interview in our sample. Semi-structured interviews lasted between fifteen and sixty minutes and followed a consistent similar structure of questions. Guided by appreciative inquiry, the interview guide for these conversations included the following questions:

-

1.

What has leadership looked like for you in this particular moment?

-

2.

How have you innovated in the wake of the social-ecclesial crises of 2020?

-

3.

What sparked the idea? What values and factors were important for you?

-

4.

Follow up questions using appreciative inquiry, looking for innovative features, naming them, and seeking an explanation.

-

5.

Do you have any sense of how people responded?

The interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded using a collaborative coding strategy that combined inductive and deductive codes. The researchers coded the interviews independently and met three times during data analysis to develop a codebook, check for reliability in coding, and discuss any new themes based on the analysis. Once spiritual practices emerged as a dominant theme, the interviews were re-coded, to identify the range of spiritual practices emerging during the constrictions of the pandemic.

Results

Eight themes emerged from our analysis of how participants responded to the pandemic: spiritual practices, particularity, measures of success, innovation examples, creativity sources, partners, technology, and others. In order to understand the distinct localizing dimensions of the pandemic, other themes present in the interviews were not considered in this paper. Our analysis later came to understand these practices as an expression of leadership; however, our primary concern in the analysis was on the practices spiritual leaders employed in order to guide innovation. Leadership, defined already as the ability to organize collective activity in response to uncertainty, is expressed through particular practices. It is not a single practice that can stand on its own. Hence, we did not include leadership as a code in our analysis. These codes are ranked in Table 2.

The top two themes were spiritual practices and particularity. These themes were evident overall, as well as in both Aotearoa New Zealand, and the Pacific Northwest. Dominant words in the interviews for both countries were ministry and spiritual, followed by online, neighborhood, conversations, and connection. As expressed by faith leaders navigating precarity and uncertainty, the data points to a pandemic spiritual leadership. Ministry, spirituality, and connection were being reimagined, both online and in neighborhoods.

Measures of success were another dominant theme, third overall, fifth in the Pacific Northwest, and fourth in Aotearoa. Innovation examples were fourth overall, third in the Pacific Northwest but sixth in Aotearoa New Zealand. A methodological difference in selection could have shaped this variation. In the Pacific Northwest, those interviewed were selected as a follow-up from an earlier study (Benac 2022). Questions focused on the pandemic's impact on the religious community's journey and values. In Aotearoa New Zealand, those interviewed were selected because they had demonstrated creativity. Questions focused more specifically on the factors that shaped the innovation.

Creativity sources were fifth overall, third in Aotearoa New Zealand, but seventh in the Pacific Northwest. This variation could have been due to the timings of the interviews. Participant interviews in Aotearoa New Zealand were conducted in the first weeks of the pandemic (April–June 2000), while those conducted in the Pacific Northwest were conducted later in the pandemic, in December 2021. Far higher levels of tiredness and diminished energy for creativity were evident as the pandemic dragged on.

Technology played a minor role, seventh overall, eighth in the Pacific Northwest, and fifth in Aotearoa New Zealand. This suggests that the enforced innovations are not limited to those with technical skills and expertise. It requires attention to innovation in the local and particular, not just the digital.

The eight themes identified here, however, found coherence within an environment where leaders could partner with the broader community they served to imagine and iterate potential responses. Coded throughout as a “container for innovation,” the themes we identified required an environment that enabled individual and collective action. For example, leaders described the importance of shared language, small groups, a history of experimentation, and established rites of Christian worship for their leadership at this moment. “So then I needed a structure, and the obvious one that came to mind was using Stations of the Cross. So, it was, yeah, kind of like there for me, to just put something around that structure,” one respondent from New Zealand observed” (NZ2). This sphere of cultural production created space for respondents to practice what we identify as pandemic spiritual leadership.

Given the priority of particularity and spiritual practices as the two most common codes, the remainder of this paper will explore these two themes as key markers of pandemic spiritual leadership.

Pandemic Spiritual Leadership

Our analysis of spiritual practices among Christian leadership during the limits imposed by the COVID-19 indicates a “pandemic spiritual leadership.” This pandemic spiritual leadership is evident in a range of grassroots adaptive innovations that emerged in two distinct geographic communities among seventeen religious communities during public health restrictions in 2020. While these practices express individuals' attempt to attend to and reimagine the particularity of religious practice, their (re)visioning also occurs amid disruptions in a broader field. Our account of pandemic spiritual leadership identifies six focal practices that distinguish pandemic spiritual leadership and considers how individuals' exploration of these practices occurs within a reconfigured field. Finally, as evidenced by participants’ attempt to “be a faithful disciple during lockdown” (NZ5), this research invites a reconsideration of congregations’ role, both within and beyond this particular time of crisis (Benac and Weber-Johnson 2020).

The six practices we identify were mentioned 110 times across our interviews, 48 times in the seven Aoteroa New Zealand interviews and 62 times in the nine Pacific Northwest interviews (Table 3).

The six practices evince the logic of practice that guides pandemic spiritual leadership. Working with Schumpeter’s understanding of innovation as acts of creative recombinations, we use representative quotes to describe the new combination and the continuities with the historic Christian practices.

Blessing—Churches have historically sought to express Christian love in their community. The pandemic disrupted many of these avenues, such as drop-in centers or playgroups. Blessing as a practice was mentioned 15 times, present in 10 of the interviews, as churches worked creatively to find new and socially distanced ways to express care.

Following Schumpeter, these are creative recombinations in which Christian commitments to care found new expression. For example, one church made up seventy boxes. Each box was filled with family activities and left at the gate to let people know the church was there if needed. When levels lowered, another church hired an ice cream truck. Masked and glove, they sought to express fun and invite connection. Other churches practiced blessing in the immediate confines of their particular place:

People are spending way more time in the neighborhood. We need to innovate. We need to figure out how do we equip them, resource them. This is a great moment for the church, a great moment for folks, a great moment for the neighborhood to be spotlighted like this. How do we come alongside and help that? (PNW6).

These innovative practices of blessing express individuals' desire to be for their community and their neighbors, especially during an acute crisis and uncertainty. Even in times of deep division or misunderstanding, pastoral leaders express their desire to bless those they serve.

Walking—Walking was the practice mentioned the least, 13 times, across 6 of the interviews. During the lockdown, local exercise increased. Those interviewed noticed “a lot more people out on walks than had ever taken walks before” (PNW8). This walking was interpreted as “waking up to the gifts in the neighborhood, the gifts of neighboring” (PNW8). In response, churches created prayer walking spirituality resources. Trees, crossroads, and mailboxes become invitations to prayer (NZ5). Several churches provided Holy Week resources. One developed a podcast that invited people to walk their local neighborhood contemplating the journey toward Golgotha (NZ2). Another invited people outdoors to take pictures of sunrises (NZ6).

However, while walking was mentioned the least, it provided some of the most striking examles of creative recombination. Two churches, from different denominations, in different parts of Aotearoa New Zealand experimented with applying Stations of the Cross to walking in local neighborhoods. It is clear that the limitations of the pandemic invited a reimagining of spiritual practices around walking. Jones observes how Christians journeyed to Jerusalem from the church’s earliest days to imagine walking with Jesus from Pilate’s house to Golgotha (2003: 156). Over time, particularly as travel to Jerusalem became difficult, churches created their own Stations of the Cross. During the pandemic, with church buildings no longer open to visitors, the Stations of the Cross were reimagined in local neighborhoods.

One localized expression began as the minister confronted the reality of the need to attend to public health concerns by canceling the usual ecumenical Good Friday prayer walk. At the same time, she observed that people continued to walk. “I’ve seen, and part of all the walking that’s going on over these days in isolation. And there’s just so much of getting out and walking and I thought goodness. Why can’t we do something that is still in our bubble but we know that we’re all doing it alongside each other?” (NZ2). The Good Friday ecumenical prayer walk was reimagined. This creativity drew on the “structure” (NZ2) of the Stations of the Cross. “I love being able to take something that the Christian community has used for centuries and it’s worked for centuries for a reason” (NZ2). A downloadable MP3 recording was made, with instructions to pause outside letterboxes and neighbors’ houses and pray in response to Jesus bearing his cross and Veronica wiping his face.

Another minister developed an Easter prayer walk around the neighborhood. “Holy Week solitude, a prayer walk” was based on a walking experience. “One of the few things that I could do [under public health restrictions] was to go out for exercise. So that's when I started thinking, okay, maybe I can re-translate this Lenten discipline of a prayer walk into something that can help other people as well” (NZ5). The aim was to “relate” Holy Week to the particularity of “people's reality.” This relating involved taking “what we’d normally do in Holy week but translating it into the new reality of lockdown,” in “the places that people would be walking past each day” (NZ5). In this particular regional town, offering a local spiritual practice required attending to the particularity of the weather.

In each case, the local was intensified. One participant wondered: “What are the things that are helping me reflect on what it means to be a faithful disciple during lockdown? And how can I link them in with things like the tree or the crossroads or the mailbox, which would be there in any community?” (NZ5). Amid constrictions, ancient spiritual practices are expressed in new ways. While Calhoun (2005) documents prayer walking as an ancient spiritual practice, the pandemic's constrictions significantly impact these Holy Week practices. What resulted is consistent with Schumpeter's definition of innovation as creative recombinations.

Although the PNW sample did not include identical experiments with Stations of the Cross, this is understandable as the PNW interviews did not coincide with Easter, the time of year Christian congregations typically practice the Stations of the Cross. However, the PNW sample included numerous instances of individuals localizing practice and walking in their neighborhoods. In each sub-population, amid a shifting context filled with unexpected limits, participants reworked existing spiritual practices to create unique local experiences. These demonstrate a pandemic spiritual leadership engaged with the traditions of Christian practice and with the local patterns of particular faith communitys’ and their neighborhoods.

Slowing—Slowing as a practice was mentioned 16 times in total, present in 10 of the interviews. One minister was confronted with how tightly households had held to a rush of activities. During the pandemic, time spent in commutes and driving children to sport was re-orientated toward socially distanced-over-the-fence-conversations with neighbors. For one minister, “already deeply embedded in the neighborhood,” the response was to “just walk. And just talk to neighbors outside, and from the sidewalk” (PNW8). Mission became localized. The question was more about a neighborhood’s flourishing than a city’s (PNW6). The pandemic provided a “great” opportunity.

The taking of opportunities was clearly seen as a spiritual practice. “I think it started with a discipline. That I had to look for God in the every day,” one participant in New Zealand observed (NZ2). This insight suggests God was discerned in the every day of lockdown. Restrictions were a place for spiritual discovery. Limits were a gift because they allowed a slowing, practiced in ways unique through this pandemic.

Place-making –A shift in ministry practices was mentioned 20 times in total, across 11 of the interviews. This shift included a focus not on a flourishing city but a flourishing neighborhood. “This is a great moment for the church, a great moment for folks, a great moment for the neighborhood” (PNW6). For several participants, God was up to something distinctive, returning churches to their neighborhoods. These perspectives suggest a new imagination about the nature and identity of being Christian. Much as Certeau suggests, the catalyst for innovating emerged from individuals’ attention to the particularities of the everyday. This distinct expression of pandemic spiritual leadership enabled individuals to take risks in seeking to meet the needs of their particular context.

Connecting—Connecting was the practice mentioned the most, 31 times in total and present in 13 of the 16 interviews. One minister began an outdoor, socially distanced book club and a socially distanced happy hour. “[J]ust bring your own camping chair, bring your own” (PNW8). This invitation resulted in deeper, more human conversations. Another minister "found that people didn't want to open a [Bible] text and study. They just wanted to hear, tell me how you're doing connecting to your grandkids” (PNW3). The need was for innovations that amplified human connections between people feeling isolated. Book clubs, happy hours, and the church playing a role in social cohesion is not new. What is significant is the socially distanced adaptations and how church leaders paid attention to these dynamics in responding to the pandemic.

An innovative approach to connecting was playfully evident in one church, where ministers placed teddy bears in the church windows (NZ9, 10). As they walked their local community during the lockdown, they noticed teddy bears popping up in the community's windows and realized that their church had big windows.

So I started with the teddies. And then they ended up having the friends come. So there were other toys. And then that was heading into Easter. So we did the Last Supper scene. You know like the painting of Jesus with the disciples. We tried to recreate that with teddy bears … and we at one point we had three windows going across the front of the church with a different scene in each that was kind of being changed as we did the Easter story … [W]e printed off, from the Children’s Bible the passage that it was related to so that people could read it to their children (NZ9, 10).

The aim was to create playful connections with passersby. “Even while the doors were shut, [church] was a place that might be kind of connecting with them … yes in fun and yes in a playful way” (NZ9, 10). These acts of connecting were a grassroots adaptation shaped in multiple ways by observing and interacting with a specific local context.

We are aware of teddy bears' reports in other contexts (Wakefield 2020). Drawing from experimentation in other contexts is consistent with Schumpeter's definition of innovation as creative recombinations. At the same time, the data from our interviews, particularly in the teddy bear example, demonstrate how the local neighborhood was a factor in the innovation, otivating, and generating content.

Localizing care—Practices of localizing care were mentioned 15 times, present in 11 of the interviews. As case numbers increased and financial pressures multiplied, one local church increasingly focused on teaching practical Christianity. Online training was offered to reinforce the need to be a Christian beyond regular times of gathering. The challenge was made: when you are not gathering for worship, how are you exhibiting your faith in good and healthy ways? Lay people were offered specific equipping in contacting and connecting, then commissioned and released as neighborhood listeners. “It’s been refreshing and encouraging to hear of the times that people are purposefully reaching out to others who they know would have a need. And then, when we hear of a specific need, to see how quickly people respond” (PNW3). The equipping of lay people to offer pastoral care is not an innovation. Yet the cognitive shift is unique, as the energy and time that would have historically been focused on gathering is framed not as a loss but as an opportunity to bear witness “in good and healthy ways.” This indicates a new imagination about the nature and identity of being Christian.

Simultaneously, this individual attention was often linked to a broader community's previous practice. As one leader in the Pacific Northwest observed, his particular congregation had been leaning into the practice of innovation for several years before this pandemic.

I just think that the biggest thing that those five years of experimenting helped us with was it created more of a space and a comfort level with trying something. Honestly, that’s just one of the hardest things to get is just to be okay with trying something different or trying something new. And, so, we already had been practicing that (PNW7).

While no one church inhabited all of these six practices, a common theme amongst those interviewed was a deepened engagement with the local. We see this intensification of the local as an expression of creative recombinations. Agency is asserted in the creative attending to the particularity of the pandemic. Amid constrictions, ancient spiritual practices are expressed in new ways. There has been a creative localizing of disciplines of discerning, spiritual direction, serving, and prayer walking (Calhoun 2005). When sustained by individual and collective discernment, connection, and collaboration (frequently mediated by technology), individuals across both contexts crafted a distinct pandemic spiritual leadership through their ongoing innovation practice.

Alongside detailed analysis of the six practices, evidence of creative recombinations was also present in the language participants used to describe their spiritual practices. Fourteen of the sixteen participants used some form of innovation language (Table 4).

One participant spoke of their innovation as being about how to “redirect” what were “evolving” understandings of existing practices (NZ6). Another spoke of taking something that the “Christian community has used for centuries” as a treasure to “apply in our own situation” of pandemic restrcitions (NZ2). Language of “improvisation” (PNW2), “adaption” (PNW3, PNW6), “iteration” (PNW4), and “shifting” (PNW7, 8) indicate an approach to innovation centred on creative recombination. Our participants were innovating by offering different treatments of existing Christian traditions. These were not de novo in their novelty. Rather, the constrictions were experienced as new spaces in which historic spiritual practices were creatively readapted.

Discussion

Pandemic Spiritual Leadership as “Pedestrian Utterings”

Certeau’s account of “pedestrian utterings,” as outlined in The Practice of Everyday Life, provides a lens to analyze manifestations of these six practices. Certeau argued that relationships between walking and the city are believable, memorable and other aware. It is intriguing how the Easter neighborhood prayer walks perform a narrative that is making meaning amid pandemic constrictions (de Certeau 1984: 112–114). Possibilities of belief are located in the physical movements, as the walking body is slowing to inhabit the meanings of Easter. The Easter neighborhood prayer walks offer a place-making in which the local is made memorable. Each act of local spiritual practice potentially change perceptions of a particular intersection and the blessing of a nearby letterbox. There is a new other awareness, a localizing of care as the sufferings and love of Easter are connected with neighbors also walking by. Certeau’s theorization is evident in the empirical data. “The feedback that I've heard from most people was that they, they were pleased to be able to do something that took them outside. You know there's a lot of Holy Week stuff or things we've been doing for church and lockdown that's on a screen. But something that you could do outside and connect with God in a different way” (NZ5). A local intersection becomes a way of connecting to the contemplation of Golgotha. Prayer in response to Jesus bearing his cross is made not with other believers but in the company of a bird calling from the branches of a local tree.

While the pandemic imposed limits, these constraints generated an intensification of practices, including of walking, slowing, place-making, blessing, connecting and localizing of care. Lockdowns create, as Certeau (1992) observed, both limit and possibility. A pandemic spiritual leadership expressed over less than a year is significantly different from a mysticism developed over several centuries. Nevertheless, we see again how the constraints of a place-based limitation result in creative recombinations. Certeau’s “pedestrian utterings” and Schumpeter’s “creative recombinations” resonate with the six practices that mark pandemic spiritual leadership.

Creative Recombinations Beyond Pandemic Time

The convenience and purposeful sample that organized this study of how ordinary practices support innovation restricted the data collection and analysis to a moment of acute crisis. Across various schools of sociology of organizations, various thinkers agree that times of transition and uncertainty require leadership (Aldrich and Ruef 2006; Hannan and Freeman 1989). Moreover, leaders’ ability to take the risks of innovation amid the pandemic requires investment, trust, and an openness to experimentation within the community she serves.

Nevertheless, the practices identified here naturally raise questions about the relationship between our account and spiritual leadership beyond pandemic time. Are the practices identified here unique to this pandemic time? As leaders and the broader faith community they serve adapt to other forms of uncertainty, are the practices distinguishing pandemic spiritual leadership transferrable in any form? While our trans-national sample does not have a longitudinal dimension, two comparable studies provide a precedent to theorize about generalizability beyond this time of acute uncertainty. First, Taylor’s (2019) longitudinal study of ecclesial innovations in the United Kingdom, which is also a post-Christian context, identifies the importance of local—what he calls indigenous wisdom—to innovation. While some of the experiments he studied did not survive more than ten years, Taylor notes how innovations that proved unsustainable, what he describes as “tried and died” (73), can still enrich the broader community of practice. Second, Benac’s (2022) study of collaboration and community guiding innovation includes interviews with the same cohort of faith leaders from before and during the pandemic. While these leaders describe the acuity of their challenges, they do not describe a dramatic departure from the previous challenges they face. Accordingly, their leadership practices during the pandemic represent a deepening of the values that have historically guided their work and the broader community they serve.

Based on these two comparable studies, we anticipate that the distinguishing markers of pandemic spiritual leadership remain relevant beyond the temporal frame for this study. As Flyvbjerg observes (2001), critical cases offer "strategic importance in relation to the general problem" (78). While spiritual leadership beyond this moment will not have the same constraints, faith communities will face other times of crises that invite leadership. Leaders described how the constraints of this moment sharpened existing practices and expanded their innovative capacity. Accordingly, we anticipate that the acuity of the crises surrounding this study will not diminish the relevance of this research beyond pandemic time. Moreover, the interpretive framework we developed to analyze this particular crisis–particularity, place, practice, and production–provides a viable interpretive frame to guide leadership practice and the study of leadership beyond this particular moment. Hence, even if the acuity of the challenges may differ, the practices outlined here can still enrich the individual and collective activity that constitutes a community of faith.

Pandemic Spiritual Leadership in a Broader Field

These innovations occur against the backdrop of a broader field-level disruption. Bourdieu’s “social fields” invite us to examine the broader “symbolic spaces” (1998: 1) in which practices find their coherence. Individuals across our two sub-populations actively drew inspiration from a broader tradition of Christian thought and practice. For example, one individual named how scripture catalyzed their imagination (NZ1). Another drew inspiration from the role of contemplation in the Christian tradition (NZ3). A third tried to translate “the Christian story” to those they served (NZ5). The PNW sub-population expressed similar symbolic engagement. One pastor drew solace from praying the rosary (PNW6). Another noted how this time of disruption accentuated the need for “spiritual disciplines” (PNW5). A third observed how spiritual formation was the responsibility of everyone in the congregation (PNW4). Although not all participants describe their symbolic engagement in terms of practice, these themes still appear. One respondent concluded: “Our bottom line belief is that Jesus invites us into a way of life, into a practice of a whole life practice” (PNW4). Hence these six innovations in religious practice take on a particular symbolic meaning, what we call pandemic spiritual leadership, as individuals locate themselves and these practices within a broader symbolic space.

A field-wide disruption was particularly evident when participants described the life of their homes. Worlds previously separated required integration. “Your personal, your work, your family life, have all just overlapped so much” (PNW7). One leader observed that “the pace of life has changed for everyone, and there are all kinds of new rhythms, healthy and unhealthy” (PNW6). The pandemic recentred childraising, including spiritual formation, to the home. This recentring began with the need to attend to public health, parents having "to be with the kids, and make sure they are distancing and safe" (PNW8). This challenged existing patterns of outsourcing formation. For some, this was lifegiving. For others, it was experienced as a struggle. “It’s hard to get your kids to sit still” (PNW1). Time worked differently. People making commitments to events altered. “You ask people for a six-week commitment and it’s like pulling teeth, but you tell them, this is a two-year process, and half the people sign up” (PNW3). Initially, not being able to meet in person was “fun,” but “the novelty of that wore off really quick … it’s been a long year” (PNW3). These comments each express particularity, describing disruptive and embodied nature of the changes in contextually-rooted ways.

The dramatic changes in the broader field affected spiritual leadership as well. Participants more often described the impact of this disruption not through a coherent account of the consequence of this moment but in an affective manner. “It really felt like we had the rug pulled out from underneath us” (PNW4) reflected one pastor. The inability to gather amounted to a fundamental change in how the common life of faith was imagined. Individuals felt this change in a visceral and unshakeable manner, and the pandemic spiritual leadership of this moment reached toward a horizon individuals could not ultimately see. If leadership is the practice of organizing collective activity during a moment of pronounced uncertainty, the faith leaders interviewed here expressed their need for the kind of leadership they offered to those in their care.

Even if individuals cannot fully describe the outcome of their practices at this moment, they can clearly express their current state: weariness and fatigue. “So, it’s been a long year with this," one pastor in the Pacific Northwest observed (PNW3). This sense was concentrated among the Pacific Northwest sample, likely shaped by their prolonged experiences of isolation and ongoing innovation at the time of these interviews. The particular practices that express a pandemic spiritual leadership occur against this backdrop amid mounting physical and spiritual weariness. While pastoral leaders certainly experienced this time as “challenging and disruptive” (Johnston et al. 2021), pandemic spiritual leadership reflects an attempt to navigate the weariness of this moment and discern how God is present in ordinary spaces.

At the same time, it is vital to recognize how congregations provided the prime social container for pandemic spiritual leadership, even though individuals did not always have access to in-person worship. Individuals described congregations as sites to practice pandemic spiritual leadership and the imaginative source of the spiritual practices they drew on to reimagine despite social distancing. Corroborating findings from an English study of discipleship and community, Jones and Shepherd (2021) discovered how congregations anchored pandemic spiritual leadership and provided hubs for ongoing innovation. Most reflections about congregations during the COVID-19 lockdowns consider how COVID-19 precipitated a crisis for local congregations (Banks 2020). Without denying the gravity of the concerns identified by this research, our research moves in the opposite direction: congregations retain an essential function as anchors for the spiritual leadership that distinguishes this moment.

This conclusion reflects a broader and pre-existing cultural loosening of ties between individuals, congregations, and broader denominational bodies (Chaves 2011, 2017). Johnston et al. (2021) observed that individuals “renegotiated and reimagined congregational life and their pastoral roles in line with the previously established Methodist customs.” Our work identifies that contextual constraints pressed participants into more localized connections. Denominational bodies certainly provided resources as stability amid uncertainty. However, the wisdom, connection, and care that catalyzed and sustained pandemic spiritual leadership more often emerged from local and prior relational networks. One participant described belonging to a group of other churches which had already explored practices of “experimenting and developing a language and capacity as a congregation for trying new experiments and learning from them” (PNW7). This prior network provided “lots of ways that pastors have been connecting together to share ideas and to support each other and encourage each other … it’s just an outpouring of that work that we’d started for the last several years” (PNW7). This comment underlines the innovations required and how inherited practices can be a resource for creative recombination.

Limitations

The data drawn from this research provides a trans-national comparison of religious leaders’ responses to COVID-19, but it does not merit generalizability. The convenience sample also introduces unavoidable bias into the analysis. Nevertheless, following Yin’s discussion of case studies for comparison (2018), this research identifies New Zealand and the Pacific Northwest as comparative cases that enable researchers to engage in theory building. While existing COVID research (Johnston et al. 2021; Oxholm et al. 2020; Taylor 2021) identifies the disruptive impact of COVID-19 on congregations and religious leaders, our paper provides a first study of how the pandemic crisis surfaced a particular form of leadership. While the similarities between New Zealand and the Pacific Northwest provide a basis for comparison, the primary limitations are the sample size and the focuse on only two geographic sites. Additional research is needed in other contexts to assess how leaders practiced pandemic spiritual leadership beyond these two regions.

Conclusion and Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced disruption that crossed sectors, borders, and disciplinary boundaries. For communities of faith and religious leaders, whose collective practice is historically tied to regular in-person gatherings, the pandemic changed the field of religious practice and catalyzed innovation. These religious practices that sustained leaders in the wake of COVID-19 were localized. Our data provides a distinct contrast to the developing narrative of online ecclesial innovation during COVID-19. Our trans-national study of innovation and spiritual practices identifies six organizing practices: blessing, walking, slowing, place-making, connecting, and localizing care. As leaders and communities of faith pursued these practices, their response to COVID-19 turned toward the local to discipline and direct their practice. The six interrelated spiritual practices express creative recombinations within a drastically changing and physically confining field. As common expressions of pandemic spiritual leadership, these practice express what Certeau describes as pedestrian utterings: they are localized practices that become intelligible in relation to the particularity of the place they are performed. They express a particular form of pandemic spiritual leadership.

This research provides an empirically-grounded theory for future research into the evolution of spiritual practices and religious leadership in the wake of a crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic introduced one acute crisis for religious leaders that catalyzed innovation. As scholars of religion examine the impact of this and future crises on faith communities, the three theoretical foci and six organizing practices provide a conceptual framework to study the form(s) of innovation that emerge from times of disruption. Moreover, this trans-national study documents the lived realities of religious leaders and communities during the pandemic. For religious leaders and organizations, the research informs the cultivation of concrete practices that can encourage communities of care as part of crisis preparation. For scholars and religious practitioners alike, this research demonstrates that pandemic spiritual leadership intensifies the local and particular, as new forms of in-place practice emerge to sustain faith communities.

References

Aldrich, Howard, and Martin Ruef. 2006. Organizations Evolving, 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications.

Ammerman, Nancy. 2014. Sacred Stories, Spiritual Tribes: Finding Religion in Everyday Life. New York: Oxford University Press.

Banks, Adelle. 2020. Church giving down more due to COVID-19 than during recession, survey shows. Religious News Service. https://religionnews.com/2020/04/22/church-giving-down-more-than-during-recession-survey-shows/. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

Benac, Dustin. 2022. Adaptive Church: Collaboration and Community in a Changing World. Waco: Baylor University Press.

Benac, Dustin, and Erin Weber-Johnson, eds. 2020. Crisis and Care: Meditations on Faith and Philanthropy. Cascade: Wipf and Stock.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. In Other Words: Essays towards a Reflexive Sociology (trans: Adamson, Matthew.). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1998. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Bramadat, Paul, Patricia Killen, and Sarah Wilkins-Laflamme, eds. 2022. Religion at the Edge: Nature, Spirituality, and Secularity in the Pacific Northwest. Vancouver, BC: University of British Columbia Press.

Calhoun, Adele Ahlberg. 2005. Spiritual Disciples Handbook. Downers Grove: InterVarsity.

Campbell, Heidi. 2005. Exploring Religious Community Online: We are One in the Network. New York: Peter Lang.

Campbell, Heidi, and Stephen Garner. 2016. Networked Theology: Negotiating Faith in Digital Culture. Grand Rapids: Baker Academic.

Chaves, Mark. 2011. American Religion: Contemporary Trends. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Chaves, Mark. 2017. American Religion: Contemporary Trends, 2nd ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life (trans: Rendall, Steven.). Berkeley Cal: University of California Press.

de Certeau, Michel. 1992. The Mystic Fable (vol. 1). (Trans. Michael B. Smith). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dykstra, Craig. 2008. Pastoral and Ecclesial Imagination. In For Life Abundant: Practical Theology, Theological Education, and Christian Ministry, ed. Dorothy Bass and Craig Dykstra. Eerdmans: Grand Rapids.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. 2001. Making Social Science Matter: Why Social Inquiry Fails and How It can Succeed Again. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frijhoff, Willem. 2010. Michel de Certeau 1925–1986. In French Historians 1900–2000: New Historical Writing in Twentieth-Century France, ed. Philip Daileader and Philip Walen, 77–92. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Ganiel, G. 2020. Is Ireland Turning to Religion During the Covid-19 Crisis? RTE Brainstorm. https://www.rte.ie/brainstorm/2020/0408/1129276-ireland-religion-coronavirus/. Accessed 3 Sept 2021.

Hannan, Michael, and John Freeman. 1989. Organizational Ecology. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hilgers, Mathieu, and Eric Mangez. 2015. Bourdieu’s Theory of Social Fields: Concepts and Applications. New York: Routledge.

Hutchings, Tim. 2020. What Can History of Digital Religion Teach the Newly-Online Churches of Today? In The Distanced Church: Reflections on Doing Church Online, ed. Heidi Campbell, 61–63. Austin: Digital Religion Publications.

Johnston, Erin F., David E. Eagle, Jennifer Headley, and Anna Holleman. 2021. Pastoral Ministry in Unsettled Times: A Qualitative Study of the Experiences of Clergy During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Review of Religious Research 64(2): 375–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-021-00465-y.

Jones, Ian, and Nick Shepherd. 2021. Lockdown Disciples: An Exploratory Study of Discipleship Journeys Through the COVID-19 Pandemic. Birmingham: St. Peter’s Saltley Trust.

Jones, Tony. 2003. Soul Shaper: Exploring Spirituality and Contemplative Practices in Youth Ministry. El Cajon: Youth Specialties Books.

Killen, Patricia O’Connell, and Mark Silk, eds. 2004. Religion and Public Life in the Pacific Northwest: The None Zone. Walnut Creek: AltaMira Press.

Lubberink, Rob, Vincent Blok, Johan van Ophem, Gerben van der Velde, and Onna Omta. 2018. Innovation for Society: Towards a Typology of Developing Innovations by Social Entrepreneurs. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 9(1): 52–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2017.1410212.

Manion, Matthew F. and Strandberg, Alicia. 2020. Covid Parish Impact Study: Summary of Findings. The Center for Church Management, Villanova University. https://villanovachurchmanagement.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/COVID-19-Parish-Impact-Study-Summary-of-Findings.pdf.

McGrath, P. 2020. Surge in People Viewing Church Services Online. RTÉ. www.rte.ie/news/ireland/2020/0507/1137149-mass-online/. Accessed 3 Sept 2021.

Murray, Robin, Caulier-Grice, J. and Mulgan, G., 2010. The Open Book of Social Innovation (Vol. 24). London: Nesta.

Newth, Jamie, and Christine Woods. 2014. Resistance to Social Entrepreneurship: How Context Shapes Innovation. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 5(2): 192–213.

Northouse, Peter. 2019. Leadership: Theory and Practice, 8th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

O’Brien, Hazel. 2020. What Does the Rise of Digital Religion during Covid-19 Tell us About Religion’s Capacity to Adapt? Irish Journal of Sociology 28(2): 242–246.

Oxholm, Theis, Catherine Rivera, Kearly Schirrman, and William James Hoverd. 2020. New Zealand Religious Community Responses to COVID-19 While Under Level 4 Lockdown. Journal Religion and Health 60: 16–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01110-8.

Pillay, Jerry. 2020. COVID-19 Shows the Need to Make Church More Flexible. Transformation 37(4): 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265378820963156.

Schumpeter, Joseph. 1911. Theorie der Wirtschaftlichen Entwicklung. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot.

Schumpeter, Joseph. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Silk, Mark. 2019. The Pacific Northwest is the American Religious Future. Religious News Service. https://religionnews.com/2019/05/31/the-pacific-northwest-is-the-american-religious-future/. Accessed 2 Dec 2021.

Taylor, Steve. 2019. First Expressions: Innovation and the Mission of God. London: SCM Press.

Taylor, Lynne. 2021. Reaching Out Online: Learning from One Church’s Embrace of Digital Worship, Ministry and Witness. Witness: Journal of the Academy for Evangelism in Theological Education 35: 1–14.

Wakefield, Abbey. 2020. Coronavirus Outbreak: Teddy Bear Hunt Helps Distract Kids Under Lockdown. BBC News 31 March 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-52108765. Accessed 17 June 2022.

Ward, Graham, ed. 2000. The Certeau Reader. Malden: Blackwell Publishers.

Ward, Kevin. 2013. The Church in Post-Sixties New Zealand: Decline, Growth and Change. Auckland: Archer Press.

Woods, Christine, and Steve Taylor. 2021. Jesus as a Socially (Ir)responsible Innovator: Seeking the Common Good in a Dialogue Between Wisdom Christologies and Social Entrepreneurship. International Journal of Public Theology 15(1): 119–143.

Yin, Robert. 2018. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods, 6th ed. London: Sage.

Acknowledgements

Dustin D. Benac wishes to acknowledge the support of The Future Church Project grant from Lilly Endowment (Grant No. 2021 1146). The authors wish to acknowledge the thoroughgoing collaborative nature of this research and writing. The co-authors should be regarded as joint authors for this piece. Although academic conventions require listing first authors, this work represents a collaborative process of mutual engagement and discovery. Co-first authors can prioritize their names when adding this paper’s reference to their resumes. We also wish to express our appreciation for the two anonymous peer reviewers, whose feedback and questions enhanced our argument's overall quality and clarity.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, S., Benac, D.D. Pandemic Spiritual Leadership: A Trans-national Study of Innovation and Spiritual Practices. Rev Relig Res 64, 883–905 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-022-00521-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-022-00521-1