Abstract

Using dynamic factor models and state-space techniques we quantify financial cycles for twenty European countries over the period 1960Q1–2015Q4 capturing imbalances across credit, housing, bond and equity markets. The paper documents the existence of slow-moving and persistent financial cycles, as well as cross-country synchronicity patterns in Europe. Spillover analysis points at the significant role the global financial cycle and the regional European financial cycle play in shaping national financial market dynamics. Quarterly Bayesian panel VAR estimations suggest that financial cycles influence business cycles and public debt dynamics, with stronger shock transmission observed in the euro area and systemic European economies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availibility

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon request, except for subscription-only data from Haver Analytics. The author would like to thank Nadya Heger for excellent statistical support, as well as the participants of the 16th Euroframe, AMEF 2019, ERFIN 2020 conferences, and two anonymous referees for valuable comments. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the views of the World Bank, the Executive Directors of the World Bank, or the governments they represent.

Notes

The paper is well-aligned with this literature also with regard to the dynamic factor approach utilized to derive supranational financial cycles based on the data for multiple countries and financial markets.

The studies similar in certain aspects are Ha et al. (2020) and Comunale (2022). However, Ha et al. (2020) investigate only G-7 economies and do not analyze implications for current account and public debt. Differing from Comunale (2017), we estimate financial cycles as a dynamic factor based on price, quantity and risk characteristics of four financial segments (in contrast to a measure based only on private credit) and analyze a broader sample, including non-EU countries.

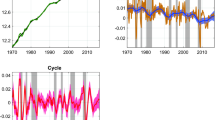

In particular, it is shown using a full-panel scatterplot of business cycle measures and charts for the dynamics of selected countries with longer data availability that, in fact, alternative statistical filters—the Baxter-King (BK) and the Hodrick-Prescott (HP) filters—yield very similar results and are strongly correlated.

The variables are standardized (demeaned and divided by their sample standard deviation) to ensure their variances contribute to the variance of the estimated latent factor symmetrically, regardless of their measurement scale and historical volatility.

One may also formulate a hierarchical model incorporating segment-specific, aggregate country-level, and regional factors in a single system. However, this would need a strongly balanced panel rather than a broader unbalanced sample for which the financial cycles are estimated individually, while only those countries with longer series form a strongly balanced sample to estimate the regional financial cycles. In addition, technically this may not be feasible for a sample with heterogeneous composition of input financial market series and contraints on the signs of factor loadings at each step. Furthermore, constructing a hierarchical factor model would yield “net” national financial cycles, i.e. financial cycles purged from common regional and global factor, while the analysis focuses on the dynamics of “gross” financial cycles and then discusses the role of the common factor (regional and global) in shaping their dynamics.

The magnitudes of predictive margins are challenging to interpret directly given that both variables do not have a direct interpretation for the full sample, as the financial cycle index does not have a global interpretable scale, while credit-to-GDP is expressed as a deviation from trend and the magnitudes differ across countries. However, one may interpret the magnitudes in relation to the range and distribution of both series, which, inter alia, can be inferred from the scatterplot in Fig. 3, panel e)

Estimations are done via the BEAR toolbox by Dieppe et al. (2016).

Estimations with the Minnesota prior produced similar results.

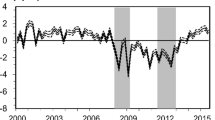

A one-standard deviation shock corresponds to a change in FC by 0.2. As noted above, financial cycle indices are standardized, which allows to interpret FC changes in terms of the number of standard deviations from the (country-specific) historical mean. These can then be related to the known financial distress episodes as benchmarks—see Fig. 2. Generally, systemic financial market events are associated with FC fluctuations of at least one standard deviation.

An alternative measure computed for robustness, Pearson’s correlation, is reported in Appendix Figure A3.

Country composition for version 1: AUT, SWE, DEU, FRA, CHE, GBR, ITA; version 2: AUT, SWE, DEU, FRA, CHE, GBR, ITA, BEL, ESP, NOR, HUN, NLD. The country composition is based entirely on the length of the financial cycle series.

The global financial cycle index is obtained from Adarov (2020), which estimates it using a similar dynamic factor model based on a global sample of countries.

Additional estimations are carried out based on a broader sample of 12 countries (CHE, GBR, DEU, NLD, ESP, FRA, ITA, SWE, AUT, NOR, BEL and HUN). However, in this case the time span shrinks to 1993Q2–2012Q2. The preference thus is given to the estimates based on the longer period, albeit both cases yield similar results.

The Minnesota prior yields very similar results—available on request.

References

Adarov A (2020) Financial cycles around the world. Int J Finance Econ. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijfe.2316

Aikman D, Haldane AG, Nelson BD (2015) Curbing the credit cycle. Econ J 125:1072–1109

Aldasoro I, Avdjiev S, Borio CE, Disyatat P (2020). “Global and domestic financial cycles: variations on a theme.” BIS Working Papers No 864

Borio C (2013) The great financial crisis: setting priorities for new statistics. J Bank Regul 14(3–4):306–317

Bori C (2014) The financial cycle and macroeconomics: What have we learnt? J Bank Finance 45(C):182–198

Borio C, Disyatat P, Juselius M (2013) “Rethinking potential output: Embedding information about the financial cycle,” BIS Working Papers 404, BIS

Borio C, Disyatat P, Juselius M (2014) “A parsimonious approach to incorporating economic information in measures of potential output,” BIS Working Papers 442, BIS

Claessens S, Kose AM, Terrones M (2011) “Financial cycles: What? How? When?” IMF Working Paper no WP/11/76

Claessens S, Kose AM, Terrones M (2012) How do business and financial cycles interact? J Int Econ 87(1):178–190

Claessens S, Kose AM (2017) “Asset prices and macroeconomic outcomes: a survey,” World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series 8259

Comunale M (2020). “New synchronicity indices between real and financial cycles: is there any link to structural characteristics and recessions in European Union countries?.” Int J Finance Econ, 2020

Comunale M (2022) A panel VAR analysis of macro-financial imbalances in the EU. J Int Money Finance 121:102511

Covas F, Haan WJD (2011) The cyclical behavior of debt and equity finance. Am Econ Rev 101(2):877–99

Covas F, Haan WJD (2012) The role of debt and equity finance over the business cycle. Econ J 122(565):1262–1286

Dieppe A, Legrand R, van Roye B (2016) “The BEAR Toolbox” ECB Working Paper Series 1934

Drehmann M, Borio C, Tsatsaronis K (2012) “Characterising the financial cycle: don’t lose sight of the medium term!” BIS Working Paper 380

Dumitrescu E, Hurlin C (2012) Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ Model 29(4):1450–1460

Eickmeier S, Gambacorta L, Boris H (2014) Understanding global liquidity. Eur Econ Rev 68:1–18

Farhi E, Tirole J (2018) Deadly embrace: sovereign and financial balance sheets doom loops. Rev Econ Stud 85(3):1781–1823

Geweke J (1977) The dynamic factor analysis of economic time series. In: Aigner DJ, Goldberger AS (eds) Latent variables in socioeconomic models. Amsterdam

Ha J, Kose MA, Otrok C, Prasad ES (2020). “Global Macro-Financial Cycles and Spillovers”. NBER Working Paper No. w26798

Harding D, Pagan A (2002) Dissecting the cycle: a methodological investigation. J Monet Econ 49:365–81

Harding D, Pagan A (2006) Synchronization of cycles. J Econ 132(1):59–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeconom.2005.01.023

Hatzius J, Hooper P, Mishkin F, Schoenholtz K, Watson M (2010). “Financial conditions indexes: a fresh look after the financial crisis”, NBER Working Papers, no 16150

Hiebert P, Jaccard I, Schüler Y (2018) Contrasting financial and business cycles: stylized facts and candidate explanations. J Financ Stab 38:72–80

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2003) Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J Econom 115:53–74

IMF (2017). “Are countries losing control of domestic financial conditions? Global Financial Stability Report. Getting the Policy Mix Right.” 04/2017, Ch.3

Jermann U, Quadrini V (2012) Macroeconomic effects of financial shocks. Am Econ Rev 102(1):238–71

Jordà Ò, Schularick M, Taylor AM, Ward F (2019) Global financial cycles and risk premiums. IMF Econ Rev 67(1):109–150

Kose A, Sugawara N, Terrones M (2020). “Global Recessions,” Policy Research Working Paper Series 9172, The World Bank

Laeven L, Valencia F (2020) Systemic banking crises database II. IMF Econ Rev 68(2):307–361

Li T, Zhong J, Huang Z (2020) Potential dependence of financial cycles between emerging and developed countries: based on ARIMA-GARCH Copula model. Emerg Mark Finance Trade 56(6):1237–1250

Mandler M, Scharnagl M (2022) Financial cycles in euro area economies: a cross-country perspective using wavelet analysis. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 84:569–593

Minsky HP (1978) The financial instability hypothesis: a restatement. Hyman P. Minsky Archive, Paper, p 180

Miranda-Agrippino S, Rey H (2015). “World Asset Markets and the Global Financial Cycle,” NBER Working Papers 21722

Nowotny E, Ritzberger-Grünwald D, Backe P (ed.), 2014. “Financial cycles and the real economy”, Edward Elgar

Obstfeld M (2015). Trilemmas and trade-offs: living with financial globalisation. BIS Working Paper No.480

Oman W (2019) The synchronization of business cycles and financial cycles in the euro area. Int J Central Bank 15(1):327–362

Pagano M. et al. (2014). “Is Europe Overbanked?” Report of the Advisory Scientific Committee 4, European Systemic Risk Board

Pesaran H (2003), “A Simple Panel Unit Root Test in the Presence of Cross Section Dependence,” Cambridge Working Papers in Economics 0346

Pesaran H (2015). “Testing Weak Cross-Sectional Dependence in Large Panels” Econometric Reviews, 2015

Potjagailo G, Wolters M (2020). “Global financial cycles since 1880” Bank of England SWP No. 867

Rey H. (2015). “Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy independence”. NBER Working Paper No. 21162

Rünstler G, Balfoussia H et al. (2018). “Real and financial cycles in EU countries—Stylised facts and modelling implication”. ECB Occasional Paper Series 205

Sargent TJ, Sims CA (1977) Business cycle modeling without pretending to have too much a priory economic theory. In: Sims CA (ed) New Methods in Business Cycle Research. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

Schüler Y S, Hiebert P, Peltonen T A (2015) “Characterising the financial cycle: a multivariate and time-varying approach.” ECB Working Paper Series 1846

Schularick M, Taylor AM (2012) Credit booms gone bust: monetary policy, leverage cycles, and financial crises, 1870–2008. Am Econ Rev 102(2):1029–1061

Stremmel H (2015) “Capturing the financial cycle in Europe”, ECB Working Paper Series 1811

Acknowledgements

Support from the Austrian National Bank’s Anniversary Fund is gratefully acknowledged (research Grant No.17044). The research was conducted while the author was at the wiiw.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Julia Wörz.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Adarov, A. Financial cycles in Europe: dynamics, synchronicity and implications for business cycles and macroeconomic imbalances. Empirica 50, 551–583 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-022-09566-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10663-022-09566-5