Introduction

After democratisation in the 1990s, Brazil was ruled by elite right-of-centre coalitions with strong ties to business and a credible commitment to the market economy.Footnote 1 In contrast with their ideological affiliations, parties such as the PSDB, PMDB, PFL, PTB and PPB agreed upon legislation that allowed the Federal Government to expropriate and redistribute land.Footnote 2 The literature on distributive conflict suggests several reasons why this should not occur, such as the role of conservative parties in preventing redistribution and elites’ reliance on democratisation as a means to protect property rights.Footnote 3 Brazil is not an exception to these postulates. Therefore, what motivated right-wing parties to embrace land expropriation?

Some authors claim that the Right passed agrarian reform because the programme did not damage the landed elites.Footnote 4 Others ascribe agrarian reform to the mixed ideological identity of President Fernando Henrique Cardoso.Footnote 5 However, the most widely accepted explanation for the actions of these unlikely expropriators focuses on how violence against the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (Landless Workers Movement, MST) shifted public opinion in favour of agrarian reform, allowing the movement to pressure the government more effectively.Footnote 6 These accounts neglect the role of elite interest during the policy-making process, portraying the Right as simply reacting to pressures from below.

In this paper, I argue that agrarian reform was triggered from above, i.e. by elites proactively endorsing redistribution in order to mitigate externalities of inequality. Threatened by a wave of urban violence and by voters’ demands for redistribution, right-wing and conservative parties endorsed agrarian reform in order to (i) prevent crime in urban areas by settling the poor in the countryside and (ii) gain competitive advantage against more distributive left-wing challengers. In contrast to other policy options available, agrarian reform allowed the majoritarian urban elites to assign the costs of redistribution to the minoritarian landed elites.

To test this theory, I coded archival, interview and survey data accounting for over 500 elite statements about agrarian reform. These data were analysed according to protocols of Bayesian process tracing,Footnote 7 which consists of estimating the likelihood of evidence in light of working versus rival hypotheses. In addition, I modelled land expropriation in a panel of Brazilian municipalities whilst accounting for rural–urban migration and the performance of the Left and controlling for key covariates in alternative explanations. Results from both methods strongly indicate that right-wing parties instrumentalised agrarian reform policies to shield urban elites against redistributive threats related to crime and electoral competition.

The study complements previous research on agrarian reform in Brazil by outlining the causal mechanisms that led right-wing coalitions to pass progressive land legislation early in the 1990s. While the cited literature highlights the role of organised peasants in pressuring for land redistribution, the present study demonstrates how redistribution to the rural poor was caused by urban elites’ own protection strategies.

More generally, the study contributes to the scholarship about the impact of externalities of inequality on attitudes towards redistribution by describing how the latter translate into concrete policies.Footnote 8 The study also bridges the gap between the literature on right-wing endorsement of progressive policies and that on agrarian reform and conflict resolution.Footnote 9

In the remainder of this article, I first place agrarian reform in Brazil in its historical context. I then summarise my causal argument. Methods and data, and results, are presented in the following two sections, followed by a final section with conclusions and the main discussion points. The online supplement presents a step-by-step formalisation of the process tracing methodology.

Agrarian Reform in Brazil

Agrarian reform in Brazil took place via a series of laws and policies through which the Federal Government redistributed land to poor landless peasants. Contradicting their neoliberal pedigree, centre–right coalitions in the 1990s relied extensively on the expropriation of unproductive private farms to boost agrarian reform, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Land expropriation (in hectares per year)

Source: INCRA: https://www.gov.br/incra/pt-br (all websites last accessed 30 Jan. 2023)

Why did right-wing and conservative parties endorse an expropriation policy that ultimately damaged the landed elites? An important piece of this puzzle is that agrarian reform was on the table of Brazil's politics long before it was finally passed into law. Debates about the ‘agrarian question’ date back to the 1930s amid Brazil's projects of modernisation.Footnote 10 At that time, Brazil was a typical case for agrarian reform, i.e. an autocratic rural country with work relations akin to serfdom.Footnote 11 However, conservative elites blocked early attempts to redistribute land. After the failure of agrarian reform projects in the 1930s and again in the 1960s, the issue resurfaced during the military dictatorship of the 1970s.Footnote 12 As in Prussia, Russia, France and elsewhere in Latin America,Footnote 13 Brazil's autocrats planned on catering to peasants in order to consolidate power, which contributed to elite desertion and consequently to democratisation in the 1980s.Footnote 14

With growing urbanisation and democratisation, Brazil became a least-likely case for agrarian reform. As noted by Bernardo Sorj, urbanisation rendered agrarian reform obsolete and unappealing to the material interest of a majority of urban constituents.Footnote 15 Nevertheless, it was in this new scenario that agrarian reform finally came to fruition. During the transition to democracy, newcomer left-wing parties and social movements embraced agrarian reform as a flagship of their agenda, in particular the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT) and the MST. The PT originated in São Paulo's industrial belt, in the southeast, born of an alliance between labour unions and progressive sectors of the Catholic church; the PT's rural ally, the MST, was from the southern state of Paraná.

In their opposition to agrarian reform, the landed elites organised under the leadership of Congressman Ronaldo Caiado (PSD, later PFL), founder of the União Democrática Ruralista (Democratic Association of Ruralists, UDR), whose mission was the obstruction of progressive land legislation. Representatives of the landed elites made up the agrarian caucus (bancada ruralista) in Congress.Footnote 16

In 1988, during the José Sarney presidency, a constitutional assembly was established. Although the assembly was dominated by right-wing and conservative parties, the resulting new (and current) constitution stated that any private land that did not fulfil a ‘social role’ could be expropriated (Article 184).Footnote 17 The support for agrarian reform by President Sarney and powerful conservative bosses, such as Antônio Carlos Magalhães, was a clear threat to latifundia and an early sign of the conservatives’ tolerance of land redistribution. Subsequently, President Fernando Collor of the Partido da Reconstrução Nacional (National Reconstruction Party, PRN) opposed agrarian reform, in line with his anti-communist rhetoric. Embroiled in corruption scandals, Collor was impeached in September 1992 and replaced by his vice-president, Itamar Franco (PMDB), who shifted the government's position on agrarian reform.Footnote 18

Regulation and Implementation (1993–2002)

Committed to neoliberal reforms and the market economy, the Itamar administration rested on an alliance between the right-of-centre parties PMDB and PSDB and the conservative parties PFL and PTB, which together accounted for over 50 per cent of seats in Congress. The programmatic Left – the PT and the Partido Comunista do Brasil (Brazilian Communist Party, PCdoB) – accounted for less than 10 per cent of Congress, while a myriad of mostly conservative parties occupied the remaining seats. In 1994, two smaller conservative parties merged to form the PPB, a powerful conservative force which joined the governing coalition. Landed elites were in the minority in Congress but continued to be represented in all main right-wing parties.Footnote 19

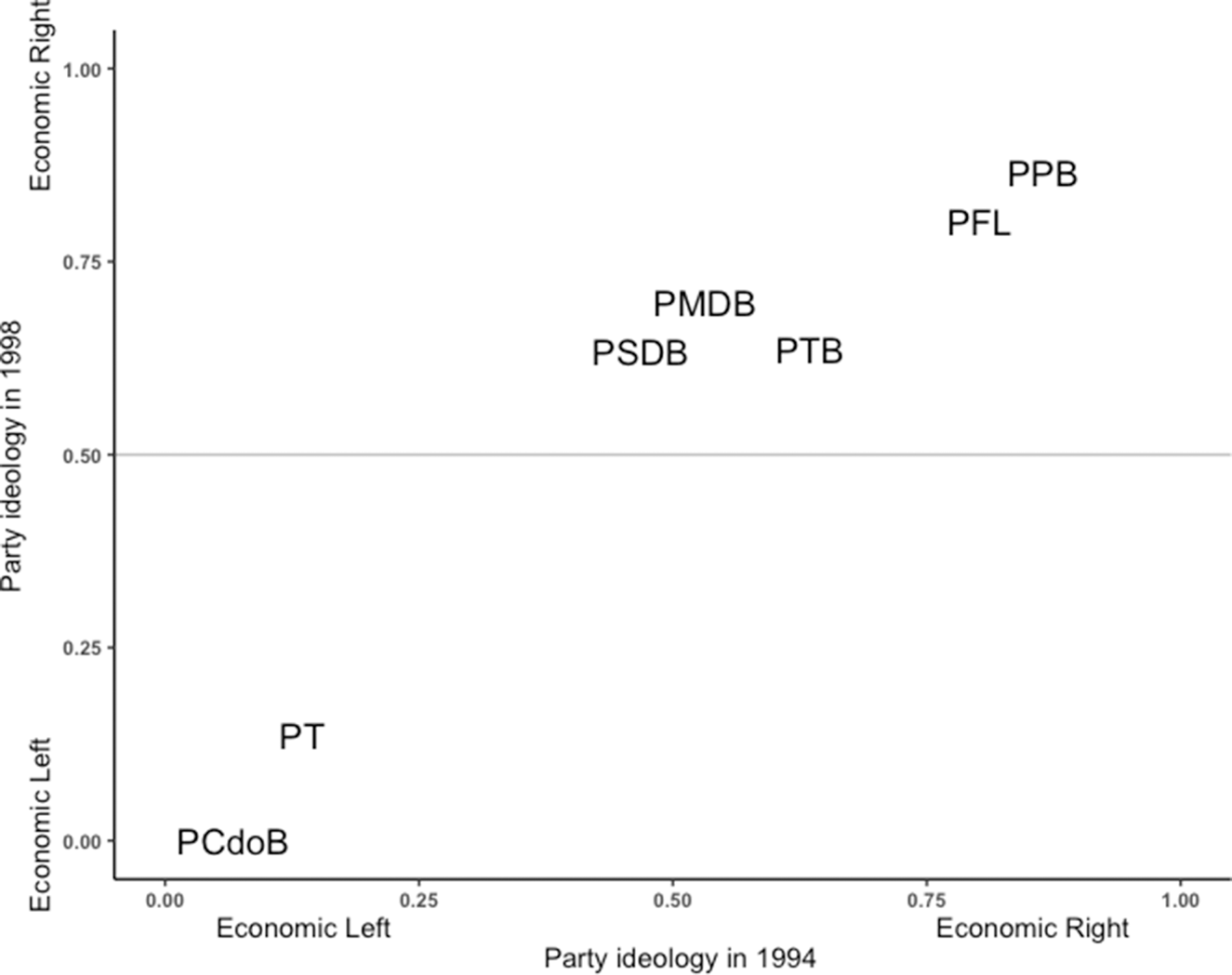

The same coalition of parties supported Itamar's successor Cardoso (PSDB). Itamar's and Cardoso's ideological affiliations are a source of debate. However, the coalition of parties sustaining their administrations clearly leaned heavily towards the Right in economic terms. Figure 2 shows the ideological distribution of parties during the two administrations.

Figure 2. Parties’ ideology in 1994 (Itamar administration) and 1998 (Cardoso administration)

Source: Staffan I. Lindberg et al., ‘Varieties of Party Identity and Organization (V-Party) Dataset V1’, https://doi.org/10.23696/vpartydsv1; not all parties are included in the dataset. V-Party, under the aegis of the V-Dem project (https://www.v-dem.net/), provides datasets of expert survey estimates about parties’ internal structure, behaviour and ideology.

During the 1990s, the coalition parties moved further toward the Right and consolidated their neoliberal identity, as shown by research on the party leaders’ estimated and self-reported ideology.Footnote 20 Apparently contradicting this tendency, the right-wing parties passed a series of laws allowing the Federal Government to expropriate and redistribute land.

First, Congress passed two bills regulating agrarian reform, which Itamar signed into law in 1993: the Agrarian Law and the Summary Process Law.Footnote 21 Itamar vetoed the agrarian caucus’ amendments to the laws and moreover legitimated the MST by receiving its leaders in the Alvorada Palace.Footnote 22 President Cardoso expanded on Itamar's approach. During his term, Congress passed a second Summary Process Law, which further facilitated expropriations, as well as a law mandating a tax on rural land holdings.Footnote 23 Between them, the Itamar (1992–5) and Cardoso (1995–2003) administrations expropriated over 13 million hectares of land (circa 32 million acres).

The bulk of expropriations occurred during Cardoso's first term (1995–9), when 6 per cent of the country's private farms were expropriated.Footnote 24 The cost of agrarian reform to landed elites was significant. In accordance with the Agrarian Law of February 1993, expropriated farmers were compensated with agrarian debt bonds (títulos da dívida agrária), which entailed lower costs to the government than other bonds (such as internal debt bonds) and could be cashed in only between five and 20 years after issue.Footnote 25 Members of the agrarian caucus described them as ‘rotten bonds’ (see online supplement). To the urban elite, the cost of agrarian reform was low. The programme represented around 20 per cent of government expenditure on agriculture.Footnote 26

The implementation of such a massive programme did not compromise the government's commitment to neoliberal reforms and fiscal austerity. However, implementing agrarian reform demanded coordination between right-wing parties, all in the name of a policy that was a flagship of the Left. Given that right-wing and conservative parties are normally regarded as guardians of private property, why did they endorse agrarian reform?

Up to now, explanations have focused on pressure from organised peasants, claiming that the massacres of Corumbiara in 1995 and of Eldorado do Carajás in 1996 increased public sympathy towards the MST, pushing the government to side with the peasants.Footnote 27 Whereas the two massacres are key in the chain of events that characterised the unfolding of agrarian reform in Brazil in the late 1990s, I contend that they cannot explain why the Right passed agrarian reform legislation early in 1993, before such events occurred. In what follows, I propose a causal argument focused on the elites’ own interest prior to the popularisation of the MST's fight for land equality.

Explaining Right Wing Support for Land Reform

The argument proposed and tested in the present study shows how two dimensions of distributive conflict, which are not directly related to land inequality, triggered elite support for land redistribution: urban crime and the emergence of left-wing challengers. In what follows I unpack how elites came to associate these two issues with the agrarian question.

For decades, industrialisation in Brazil incentivised poor peasants to migrate to big cities, where they lived in densely populated favelas. These communities became stigmatised as sources of crime and violence.Footnote 28 In light of these externalities, Elisa Reis noted that elites in the late 1990s framed agrarian reform in terms of their desire to send the poor ‘back’ to the countryside.Footnote 29 Building on Reis’ observation, I theorise that the right-wing parties mirrored urban elites’ aspirations, i.e. they expected agrarian reform to have an effect on crime.

However, mitigating the effects of crime was not the only potential benefit of implementing a redistributive land tenure policy. As shown in recent studies about right-wing coalitions embracing progressive policies, conservative incumbents seek to gain leverage against the left-wing opposition by selectively endorsing policies that appeal to median voters and the poor.Footnote 30 In the same way, I theorise that right-wing parties anticipated electoral gains from agrarian reform. The programme could increase right-wing incumbents’ credibility as redistributors, making the governing coalition more competitive against left-wing challengers and therefore preventing the emergence of more committed redistributors. Thus, fear of crime and competition with the Left together triggered support for agrarian reform within right-wing and conservative parties, ultimately leading to the regulation and implementation of land expropriation on a large scale.

A third relevant aspect of the ‘agrarian reform’ solution relates to its relatively low cost. Contrary to other redistributive policies, agrarian reform allocated the cost of redistribution to landed elites, maximising gains for the broader set of urban elites at their expense. In comparison with other avenues of redistribution, agrarian reform was inexpensive.

In a nutshell, right-wing parties became aware that inequality was a source of threat to elites in the form of urban crime and through the increasing popularity of left-wing political alternatives. As elites coordinated policy solutions to these externalities of inequality, agrarian reform stood out as the most cost-efficient alternative and for this reason the Right endorsed it, betraying the landed elites. If this argument is correct, this means that agrarian reform was caused by social turmoil in big cities after democratisation and the emergence of left-wing challengers, and not by the more visible role of the MST towards the late 1990s.

There are important clues suggesting that this was indeed the case, i.e. that the public validation of the MST's mission was not the root cause of the set of laws and policies that allowed the reform to take place. First, the convergence of right-wing parties in support of agrarian reform preceded the wide media exposure of the MST in the mid 1990s, which is credited with the movement's high popularity. In fact, the positive coverage of the agrarian question can itself be attributed to the interests of elites, as the media conglomerates leaned heavily towards the Right.Footnote 31 Second, land redistribution relying on expropriations of private land dwindled when the PT coalition finally won the presidency, despite the party's strong links with the MST. The ending of expropriatory agrarian reform under PT rule is consistent with the argument put forward: as the crime wave reduced in the 2000s (see Figure A.1), and with the PT abandoning its adherence to democratic socialism in favour of an alliance with conservative sectors, the triggers for the Right's support for agrarian reform faded.

There are two mutually exclusive counterfactual scenarios which would either confirm or invalidate the causal role of fear of crime and competition with the Left.

Counterfactual 1: Agrarian reform would not have occurred in the absence of fear of urban crime and competition with the Left, all else being equal.

Counterfactual 2: Agrarian reform would have occurred regardless of fear of urban crime and competition with the Left, all else being equal.

If Counterfactual 1 is true, my causal argument is confirmed. If the second counterfactual is correct, then something else caused right-wing support for agrarian reform. In the following section I outline the methodology and data utilised to estimate the level of confidence in my theory vis-à-vis rival explanations.

Data and Methods

The research question of this study is: Why did right-wing majorities sponsor a redistributive agrarian reform programme in Brazil? To answer it, I propose the following theory:

T1: Elite-backed right-wing parties endorsed agrarian reform in order to mitigate urban violence and to gain credibility as redistributors against left-wing challengers at a low cost.

Theory T1 accounts for two mutually reinforcing causal mechanisms linking inequality to elites’ policy preferences: fear of crime and electoral competition with the Left.Footnote 32 To test the theory, I subdivide it into two working hypotheses:

H1: Concern with urban crime increased support for agrarian reform among right-wing political elites.

H2: Concern with the left-wing opposition increased support for agrarian reform among right-wing political elites.

Both hypotheses need to be true in order for T1 to be true. To test these hypotheses, I integrate process tracing and regression models in a two-step multi-method design. First, I rely on protocols of Bayesian process tracing to estimate the likelihood of observations in light of H1 and H2, as well as their likelihoods considering rival explanations. Second, I use regression models to estimate whether covariates derived from the motivations described in H1 and H2 predict how right-wing administrations targeted farms for expropriation. The protocols applied in each step of the design are described below.

Process Tracing

I adopt a Bayesian framework for process tracing building on Tasha Fairfield and Andrew Charman's formal approach and in line with recommendations from other case study methodologists.Footnote 33 The Bayesian approach entails estimating how likely (or expected) the evidence is under the working theory as compared to rival hypotheses. Confidence in the working theory is updated favourably whenever it makes the evidence more expected and unfavourably when rivals better predict the evidence. Mathematically, this is expressed as

where Pr means probability, Ta represents each alternative causal explanation and K represents the evidence. Departing from a state of ignorance, I assume disadvantageous prior odds for my theory (20 per cent) in contrast with the combined prior likelihood of four mutually exclusive alternative hypotheses (80 per cent) described in detail in the online supplement. Posterior odds are not expressed numerically, as this would increase subjectivity, but using comparisons. For instance, let us assume that K = the speech of party leader X prior to the vote on law Y. If K is clearly more expected under T1, then

In the present article I focus on the strongest alternative hypothesis in the literature; however, a more exhaustive account of the other three alternative explanations is presented in the online supplement. The main alternative hypothesis Tai affirms that agrarian reform occurred after massacres against MST peasants generated visibility and sympathy for peasants, granting the movement the opportunity to expand its operations and pressure the government, which then conceded land redistribution.Footnote 34

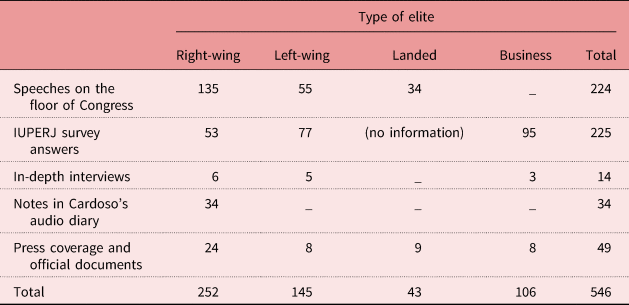

To update the confidence in T1 vs. alternative hypotheses I built a dataset of 546 elite attitudes related to agrarian reform policies. The data were mostly collected through term searches (using ‘agrarian reform’ as the keyword) in transcripts of Congressional debates and of President Cardoso's personal audio diary, official documents, press and TV coverage and campaign materials.Footnote 35 In addition, I analysed data from in-depth interviews from Elisa Reis’ project and a survey of elites.Footnote 36 Reis conducted interviews with legislators, party leaders, Federal Government officials and businesspeople in 1998, 1999 and 2012, sampled using the positional method; the elite survey sampled members of Congress, people in top positions in the Federal Government and business leaders.Footnote 37 I then coded the material, separating favourable from unfavourable statements about agrarian reform, and whether a practical reason for the policy was stated. The data are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1. Statements about agrarian reform, by elite group

Notes: In order to distinguish urban from landed elites I coded elites’ ties to rural interests. (This was not possible for the IUPERJ survey data, which are anonymised.) The ‘right-wing’ group consists mainly of urban members of the PSDB, PMDB, PFL, PTB and PPB. The ‘left-wing’ category comprises mainly PT leaders and their allies, such as the MST leadership itself. The ‘landed’ elite group consists of Congress(wo)men identified with the agrarian caucus in those same right-wing parties and elites in agribusiness. The ‘business’ group consists of elites at the head of corporations and business organisations, excluding agribusiness.

Sources: See Footnote notes 35–Footnote 7.

Regression Models

I ran multilevel regressions to model the number of expropriated farms in each locality using both fixed (i.e. the same for every cluster/nest) and random slopes.

The predictors that are consistent with T1 are the number of emigrants from each state and the vote ratio for Luis Inácio Lula da Silva in the presidential elections of 1989. The first measure accounts for the migratory pressures that one state imposes on other states, mainly the emigration of poor peasants from northern states to the metropolises of the wealthier states of the south. The second measure accounts for the level of electoral competition with the Left in each municipality. In simple terms, if Ta is true the effect of migratory pressures and Lula's vote ratio should be zero after accounting for the levels of demand for land and of conflict in each locality.

The data are nested in three levels: municipalities (Level 1) within states (Level 2) within years (Level 3). The reference model is specified as

where Y is the yearly number of expropriated farms in a municipality (see Table 2), all the ‘0’ constants represent the different baselines (intercepts) in each level, ‘Lula's votes’ represents the ratio of votes that PT candidate Lula received in the run-off presidential election of 1989 in a given locality, ‘Emigrants’ represents the number of emigrants per 1,000 inhabitants in each state and E is an error term. The controls in Level 1 are the number of land occupations carried out by the MST, the number of murders in the locality (as a proxy for rural violence), the number of unproductive estates per 1,000 inhabitants, and municipal income per capita. Level 3 controls are press coverage of the agrarian question in each year and dummies for the two massacre events. Controls account for the alternative explanation Tai (based on violence against the MST and issue salience), as well as for the suitability of the land for expropriation in accordance with the Agrarian Law of February 1993 (see Footnote note 21) and the economic characteristics (income per capita) of each locality (see Appendix for regression coefficients of all covariates included). All covariates are centred at their mean.

Table 2. Panel of Brazilian municipalities: descriptives

Notes: The panel to which the regression models were applied is structured in hierarchical fashion, with municipalities nested in states and states nested in years.

The data account for the 48,785 municipality-years for which all measures are available.

Sources:

Expropriations and rural conflict at the municipal level: Michael Albertus, Thomas Brambor and Ricardo Ceneviva, ‘Land Inequality and Rural Unrest: Theory and Evidence from Brazil’, Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62: 3 (2018), pp. 557–96

Voting data for the 1989 elections: Tribunal Superior Eleitoral (Supreme Electoral Commission, TSE): https://www.tse.jus.br/eleicoes/

Brazilian states’ emigration rate: 1991 Census: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics, IBGE): https://www.ibge.gov.br/

Municipal income per capita: Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (Institute of Applied Economic Research, IPEA): http://ipeadata.gov.br/

Land occupations by MST: Albertus et al., ‘Land Inequality and Rural Unrest’.

Murders: Albertus et al., ‘Land Inequality and Rural Unrest’.

Number of unproductive estates per 1,000 inhabitants in each municipality: IPEA: http://ipeadata.gov.br/

Press coverage of rural conflict: Ondetti, Land, Protest, and Politics, p. 152: number of mentions of rural conflict and agrarian reform in the Folha de S. Paulo, by year.

Results

The results are presented in the following fashion. The first subsection presents estimates of the level of elite support for agrarian reform. The second and third subsections show the evidence informing H1 and H2,, which define fear of crime and competition with the Left as the causal mechanisms that explain support for agrarian reform. The fourth subsection shows the results from the regression models.

How Supportive Were Conservatives?

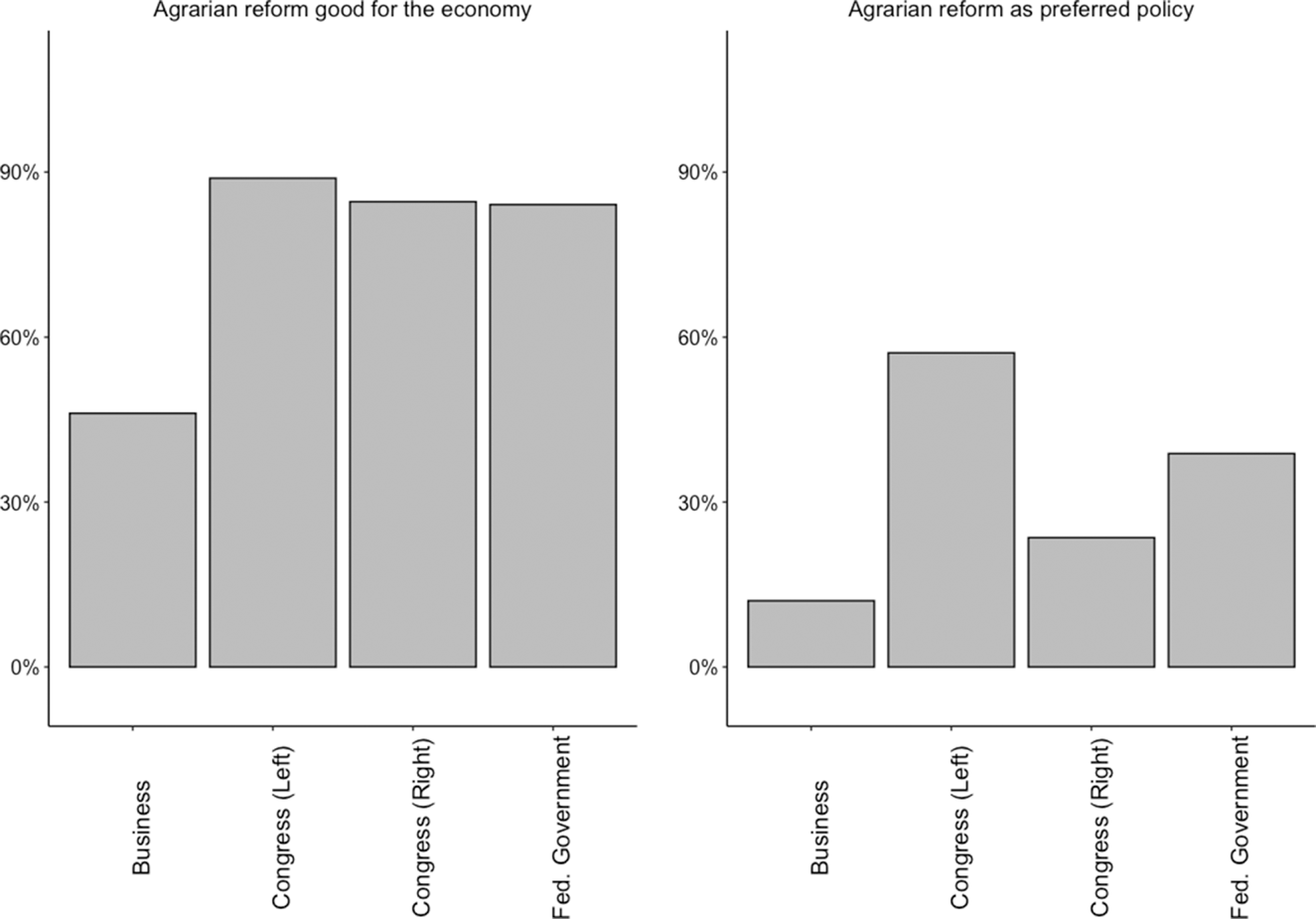

Figure 3 illustrates attitudes about agrarian reform among different elite groups surveyed during the Itamar administration.

Figure 3. Elite support for agrarian reform, 1993–4 (Itamar administration)

Source: IUPERJ elite survey (see Footnote note 37)

The figure shows that members of Congress who identified as right-wing as well as elites in the Federal Government during the Itamar administration were supportive of agrarian reform, even when compared with those who identified as left-wing. The absolute majority of right-wing partisans in the survey sample regarded agrarian reform as very important for the country, and about one quarter of them portrayed it as either the most important or the second most important policy for solving the problem of inequality in Brazil. Within the Federal Government, agrarian reform was even more popular. Even business elites portrayed agrarian reform as important, although not yet a priority at that point.

The timing of the IUPERJ elite survey coincided with the regulation of agrarian reform in Congress and Itamar's endorsement of the policy in 1993. The policy approval rates among elites and the endorsement by right-wing parties in 1993 seem unlikely if the conservatives’ true preference was indeed antagonistic to agrarian reform, as previously believed. In the following subsections, I demonstrate how two main mechanisms, apparently unrelated to the rural question, explain why the Right deserted landed elites and became supportive of agrarian reform.

Mechanism 1: Fear of Urban Crime

Living in luxury properties in big cities such as Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo, often just a few blocks away from favelas, the elite felt threatened by a wave of criminal violence in the 1990s and early 2000s (see murder and kidnapping rates in Figure A.1). Affluent residents of the southeast were targeted by kidnappers and taken hostage until ransoms were paid.Footnote 38 Not infrequently, mobs of poor people would storm affluent neighbourhoods, robbing those who got in their way – a criminal and rebellious tactic known as the arrastão.Footnote 39 The wealthiest neighbourhoods in southeast metropolises gradually became a very hostile territory for elites, overcrowded with beggars and surrounded by rebellious poor.

Around 65 per cent of the politicians and 45 per cent of the business elites surveyed by the IUPERJ between 1993 and 1994 perceived urban violence as the most relevant consequence of poverty. The overwhelming human misery in the metropolises of the southeast was in part the result of cities’ failures to absorb the mass migration from poorer rural areas in the north. It is estimated that the rural exodus accounted for 33 per cent of urban demographic growth between 1990 and 2000.Footnote 40 Many of those migrants ended up in favelas, perceived by elites as the source of criminal violence.Footnote 41 In a session of Congress in 1994, Congressman Osmânio Pereira (PSDB) claimed:

The favelas, the homeless families, the street kids, unemployment … all are but the reflection of the prevalence of a perverse socio-economic structure, the injustices of which are bound to be taken out on the dominant classes too. This has been widely demonstrated by the violence of our daily life … Fortunately, the Itamar Franco administration has so far proven its intention of implementing agrarian reform for real. We hope it continues on this path.Footnote 42

In line with Congressman Pereira's reasoning, to many elites agrarian reform represented a step forward in mitigating urban violence, at an acceptable cost. The rationale is unlikely but not illogical: if the rural exodus was a cause of conflict in cities, then providing for the rural poor would help solve that problem. More importantly, agrarian reform was less costly to the majority of elites when compared with other redistributive policies, as its costs were allocated to landed elites. PFL Congressman José Alves argued on 7 April 1995 that ‘government expenditure on health, education, housing and sanitation’ cost more than improving ‘living conditions in the countryside’. The cost efficiency of agrarian reform was mentioned even more explicitly by PPB's conservative leader Espiridião Amin in 1996. He claimed:

One truth has been stated repeatedly here on the floor of the Senate, as well as throughout our huge [country of] Brazil, a truth which all people with common sense are convinced of, but that the government is reluctant to accept: it is cheaper to invest in keeping peasants in the countryside than it is to later solve the social problems that they cause when they migrate to the cities.Footnote 43

The following statement from a conservative PFL politician further illustrates such rationale.

First of all, I am in favour of agrarian reform. I am in favour. What is agrarian reform? Agrarian reform to me means to provide some land to the average Joe and just letting him be there … You may think at first that the investment needed would be too great, but it would not be really. You have to think that, if you don't do that, that same guy will go to a big city to create problems.Footnote 44

In the eyes of Amim and the PFL interviewee, agrarian reform could be a means of keeping poor peasants from migrating to big cities, preventing them from becoming threats to the urban rich and mitigating violence at a low cost. Excluding those by members of the agrarian caucus, 40 per cent (76) of the speeches in Congress about agrarian reform between 1992 and 1997 explicitly mentioned urban criminal violence and the overcrowding of big cities as a key motivation for the policy. Elites anticipated that, by redistributing land in the countryside, they could stop or even reverse the rural exodus and consequently mitigate distributive conflict in big cities. Below are extracts from speeches from the floor illustrating this reasoning:

What about urban violence? And the state of violence that the country watches in astonishment? … In the wonderful city of Rio de Janeiro, there were three kidnappings occurring almost simultaneously last week … Social inequalities will only soften when we truly have conditions to promote agrarian reform.Footnote 45

Agrarian reform is one of the most urgent matters within the context of the current state of degradation of the Brazilian social fabric. The consequence of our indecision can be seen in the panic of the middle and rich classes, facing the hordes of poor that surround us on every corner … We are now in a dilemma, between a serious and responsible agrarian reform and barbarism.Footnote 46

The idea of agrarian reform as a cure for urban violence resonated on the Left as well. ‘With agrarian reform, we will have more food and jobs, as a consequence, violence will decrease’, said a PT interviewee in 1999. Noting that linking agrarian reform and urban violence was beneficial to the MST, the movement's leader João Pedro Stedile made a similar statement to the press in 1995, arguing that ‘one way of fighting violence in big cities is by implementing agrarian reform’.Footnote 47 Overall, private and public discourses on inequality followed a similar pattern: elites looked more favourably on agrarian reform as they realised that inequality was generating conflict in urban settings, which ultimately affected their own security.

Meanwhile, violence in the countryside was on the rise as well. Following that of Corumbiara in 1995, the rather more notorious massacre of 19 landless workers in the city of Eldorado do Carajás in April 1996 increased public support for the MST, further pressuring Congress to legislate in favour of agrarian reform. Excluding those by members of the agrarian caucus, 30 per cent (57) of speeches about agrarian reform between 1992 and 1997 mentioned violence against the MST. Nevertheless, massacres did not replace criminal violence as the main motivation for agrarian reform expressed during speeches on the floor of Congress. In 1997, the Cardoso administration defended agrarian reform policy and justified land expropriation in the light of urban problems: ‘Expelled from the countryside, this man [the rural man] and his family went on to form the armies of ill-employed, under-employed and unemployed in the ghettos of Brazil's big cities, crafting the dramatic social landscape, marked by profound inequalities, which lasts to this day.’Footnote 48

As noted above, the main explanation in the literature for the Right's endorsement of agrarian reform relates it to shifts in public opinion after the massacres of 1995 and 1996. However, the data portray how agrarian reform was more frequently justified by right-wing partisans as a measure to mitigate urban crime. This does not imply that the massacres had no impact on the policy. The Eldorado do Carajás massacre in particular pressured President Cardoso to show a policy response, as described in the next section. In terms of the number of expropriations, the massacre may or may not have had an effect (see Figure S1 in the online supplement). Overall, the arguments made by right-wing partisans in Congress, the rationale expressed during the open-ended interviews conducted by Reis, elites’ responses in the IUPERJ survey and public statements reported by the press (see Footnote notes 35–Footnote 7) are much more expected assuming H1 as true than assuming alternative explanations as true.

Mechanism 2: Electoral Competition with the Left

Although the Right implemented agrarian reform, the policy had been a flagship of the left-wing opposition since the 1980s, in particular of the PT. The party was born under the leadership of Lula da Silva, a prominent union leader who coordinated huge strikes during the military dictatorship. The PT united key segments of the Left, from former guerrilla fighters to unions, scholars, sectors of the Catholic church and, unofficially, also the MST. In a party event in Brasília in 1987, Lula warned the economic elite that ‘with the PT in government … banks will be nationalised, and the working class and the government will have control over banks’.Footnote 49

In the 1989 presidential election, Lula made it to the runoff but ended up losing to Fernando Collor de Mello by a 6 per cent margin. The defeat of Lula in 1989 demanded massive elite coordination, including from the heads of media outlets, in particular the Globo group.Footnote 50 Since the 1989 election, the PT had been perceived as a major threat to conservative and economic elites, and portrayed as such by the press. The idea of Lula winning the presidential election terrified the economic elites,Footnote 51 including the landed elites. To them, the PT was a prototypical socialist threat, with its red flag and bearded leaders.

PT's flagship programme for agriculture was agrarian reform. However, after the meltdown of the Collor presidency, newly installed President Itamar Franco placed himself one step ahead of the PT by endorsing the Agrarian Law and the Summary Process Law of 1993 (see Footnote note 21) in an outright commitment to agrarian reform.

As the 1994 presidential elections neared, Lula's candidacy was clearly ahead, according to early opinion polls.Footnote 52 Itamar's finance minister Cardoso was considered by many conservatives to be the most competitive candidate against PT. He was credited with ending hyperinflation, which provided him with extensive positive media exposure. A moderate with previous socialist credentials, Cardoso signalled commitment to both redistribution and neoliberal reforms. Like Collor, he could count on massive support from business and media corporations against Lula. As the government's candidate, he renewed the alliance with the PFL and PTB, and received unofficial support from PMDB factions despite the party having its own presidential candidate.

Fighting the Left over ownership of the redistribution issue was key in the election, with debates centred on social justice. At this point, agrarian reform delivered double benefits for urban conservatives: it addressed the issue of mass migration and, more immediately, helped the Right in its competition with the Left. In a Congress session in May 1994, PFL Congresswoman Maria Valadão drew Cardoso's attention to the electoral appeal of agrarian reform. She contended: ‘I hope that this deserves the attention of candidate Fernando Henrique Cardoso, allowing his campaign to take off … I am talking about a fair agrarian reform, which should return to the countryside the people who wish to produce.’Footnote 53

The congresswoman's remarks illustrate how the two motivations of the Right in supporting agrarian reform were mutually reinforcing. First, expropriation would protect the elite by settling the poor in the countryside. Second, the policy would provide competitive advantage against left-wing challengers. Cardoso indeed introduced the issue of agrarian reform in his campaign later that year, committing first to settle 100,000 landless families and later increasing that number to 280,000 families.

Other right-wing presidential candidates also came out in support of agrarian reform. Orestes Quércia (PMDB), a multimillionaire political boss, promised to deliver ‘the greatest agrarian reform the world has ever seen’.Footnote 54 Agrarian reform was also a campaign promise of the ultraconservative Esperidião Amin (PPB) and even of the far-right nationalist leader Enéas Carneiro, a member of the Partido da Reedificação da Ordem Nacional (Party of the Reconstruction of the National Order, PRONA).Footnote 55 Astonishingly, agrarian reform appeared in the 1994 elections as a consensual policy across the ideological spectrum. In a presidential debate on national TV, Cardoso contended: ‘All the parties feature agrarian reform in their programmes. The only thing left is to actually do it. I am going to do it.’Footnote 56

As the race converged on a dispute between the PT and PSDB candidates, Lula complained that Cardoso's programme of agrarian reform was a copy of his own: ‘They [the PSDB] wrote their programme in one weekend, because they plagiarised [ours]. It would have been more dignified for them if they admitted that our programme was the best one.’Footnote 57

Despite the strong initial appeal of Lula and the PT, by the end of the campaign Cardoso was victorious. A few months after taking office, he expropriated 1 million hectares (2.5 million acres) of land for agrarian reform in a single shot. In a ceremony held at one of the expropriated farms in the state of Ceará, the President argued:

Never has a government expropriated one million hectares of land before. We forced that half-dozen people [the left-wing opposition] to shut up … Brazil is going to change and the minority group which I defeated in the polls will not prevent that from happening. The agrarian reform will be done and it has already started, for the benefit of all of us.Footnote 58

Expropriating land helped President Cardoso to counterbalance his depiction as a neoliberal politician and prevented the Left from gaining ground. In early May 1995, he made note of this in his private audio diary: ‘The government has to make an effort in the matter of assentamentos [expropriated land provided to the landless] … This is what I call a social agenda. And this agenda now needs to be promoted in order for us to occupy [electoral] spaces. Otherwise, the left-wing opposition will say that we are paralysed regarding social matters.’ On 12 October, he added: ‘With [us pushing] agrarian reform … it becomes harder [for others] to say that the government only cares about inflation.’

With the aim of fighting the PT's ownership of the agrarian reform issue, Cardoso and allied conservative political elites remained committed to its implementation. The PT, on the other hand, faced the dilemma of either trying to obstruct legislation on agrarian reform, showing a consistent opposition to the government but betraying its base and principles (and siding with the landed elites), or approve it, remaining loyal to their programme but strengthening Cardoso's administration.

The costs for the landed elites were significant as well. The agrarian debt bonds used as compensation for expropriated land were deemed highly unattractive, making land ‘worthless’, in the exaggerated words of Senator Júlio Campos (PFL).Footnote 59 Perhaps more importantly, the agrarian caucus had been defeated over the core of its agenda. Its leadership in Congress showed great frustration with the government, threatening to leave the coalition and to counter-attack. ‘We will play hardball … the government will lose our support’, threatened Congressman Nelson Marquezelli (PTB).Footnote 60 Cardoso largely ignored such a threat: it is not mentioned in his diary nor was any action by the government offered in response. Marquezelli complained about the treatment that landed elites were receiving. ‘If Volkswagen or any other company can have armed guards, why can't the farmers?’ he asked in an attempt to justify the private militias that were terrorising the MST.Footnote 61 Months earlier, the police, along with members of such private militias, had killed nine landless peasants and wounded dozens more in Corumbiara.

Up to that point, the violence against the MST did not merit the attention of the president, to judge from notes in his audio diary. This changed after the massacre of 19 landless workers in Eldorado do Carajás in April 1996. The massacre received ample media coverage and was followed by increasing public support for the MST. PT leaders and members of the Church met with President Cardoso two days after the massacre, pressuring him to do more for agrarian reform. Cardoso replied that it was the opposition which was blocking amendments to the 1993 Summary Process Law.Footnote 62 He recorded his response to PT leaders in his diary: ‘Do you [the PT] want to help? Do you want to participate? I am all for it, but you have to give us the votes; [so far] you have not, you always vote against.’ On 23 December 1996, the government got the votes to approve the second Summary Process Law, accelerating land expropriations. A few days earlier, on 19 December, Congress had passed a new tax on rural land holdings, despite resistance from landed elites (see Footnote note 23).

Consternation over the Eldorado do Carajás massacre provided the impetus for further legislation on agrarian reform, as Ondetti shows,Footnote 63 and was used to frame the implementation of a programme of financial aid to small rural producers, the Programa Nacional de Fortalecimento da Agricultura Familiar (National Programme for Strengthening of Family Agriculture, PRONAF). However, in the notes in his audio diary Cardoso more frequently expressed concern about fighting the Left than about the pressure of public opinion following massacres.

Cardoso mentioned competition with the Left in February, May and October 1995 in his private notes on agrarian reform. This motivation was therefore present both before and after the first massacre (in Corumbiara), which was not mentioned in the diary in 1995. In 1996, Cardoso made five references to violence against the MST, all in April, i.e. in the month of the second massacre, in Eldorado do Carajás. He made five additional references to agrarian reform and competition with the Left in 1996 in the months of September, November and December.

Given the government's reinforced commitment to agrarian reform, the landed elites adopted two new strategies of mitigation. First, they pushed for legislation that would shift the mode of land redistribution from expropriations to land acquisition through mortgages granted by a public bank, the Banco da Terra (Land Bank). This strategy had mixed results for landed elites, as the mortgages programme was implemented but expropriation remained the main mode of land redistribution, accounting for 90 per cent of distributed land.Footnote 64 The second strategy involved collusion with technocrats, i.e. establishing a direct relationship with top bureaucratic elites within the government to bias policy implementation in landed elites’ favour, or at least to mitigate losses. Such a strategy accounted for increasingly generous compensations for expropriated land.Footnote 65 While this second strategy was deemed successful by some authors,Footnote 66 members of the agrarian caucus complained about how it distorted the land market and how the programme in general was a source of great insecurity for farmers (see quotes in the online supplement).

Overall, the reaction by landed elites, the statements made by right-wing elites during the presidential campaign of 1994, and the notes in Cardoso's diary up to May 1995 are highly expected under H2 and very unlikely if alternative hypotheses are true, in particular with regard to the causal role of massacres in August 1995 and April 1996. It is clear that right-wing parties and Cardoso in particular envisioned land expropriation as an asset against the Left. For the 1998 re-election campaign, Cardoso portrayed himself as someone who was actually implementing redistribution, backed by a conservative coalition concerned with the externalities of distributive conflict. He was re-elected with over 50 per cent of the vote.

Effect on Expropriations

As shown in the previous sections, the urban elites believed that agrarian reform would reverse rural–urban migration and cripple the Left's electoral appeal. In what follows, I assess whether these motivations shaped the distribution of land expropriations. I ran regression models to test whether (i) the relative number of people emigrating from each state and (ii) Lula's vote ratio in the 1989 presidential elections in each municipality effectively predict the number of farms expropriated in each municipality, accounting for other predictors of agrarian reform.

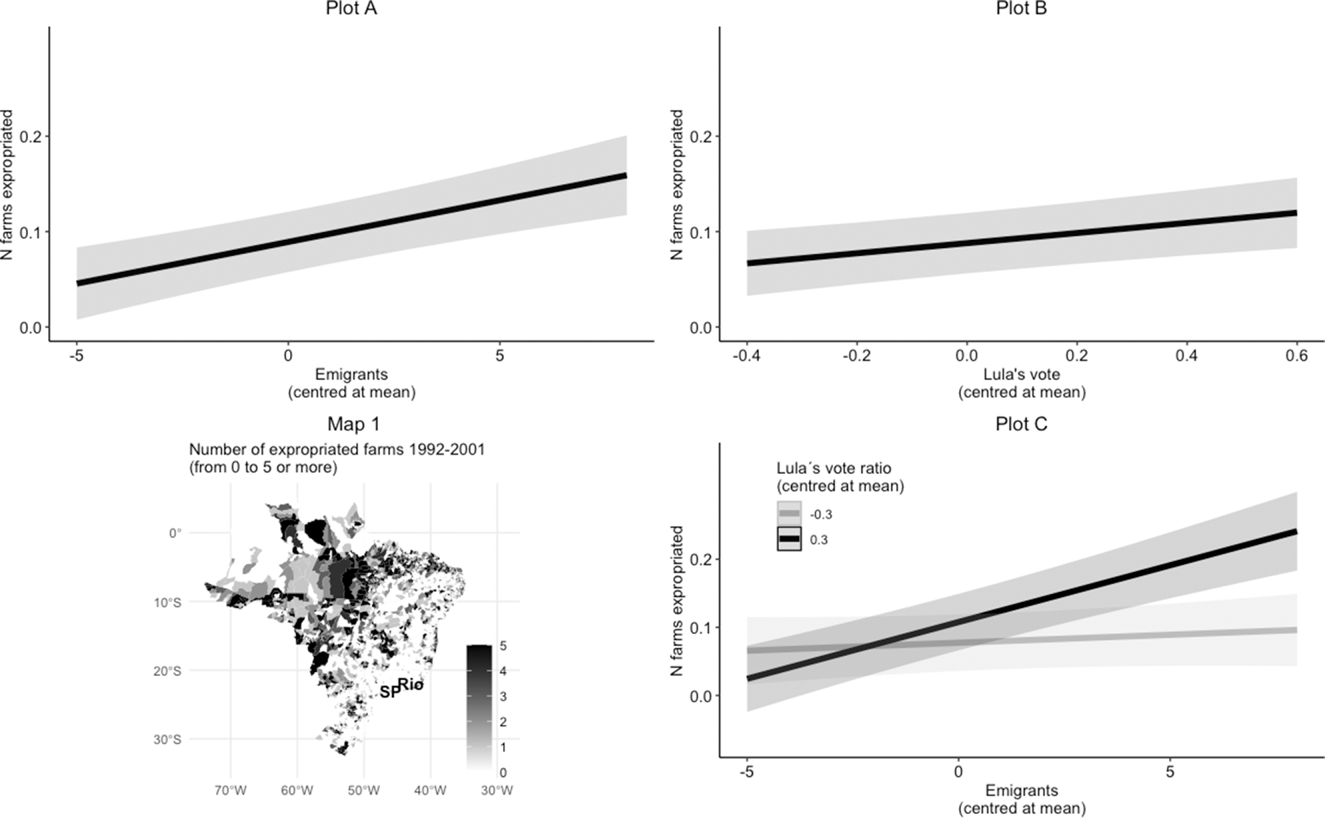

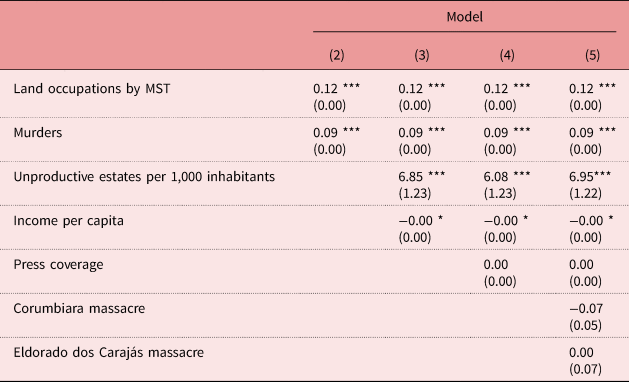

Table 3 displays the regression coefficients in the five predictive models; Figure 4 shows the marginal effects of migration and Lula's vote ratio on the number of expropriations as well as the geographic distribution of expropriations.

Figure 4. Effect of migration and Lula's vote ratio on expropriations

Notes: Confidence intervals at 95% level of confidence. Estimates based on Model (5) in Table 3. Data on MST land occupations in Map 1 based on Albertus et al., ‘Land Inequality and Rural Unrest’.

Table 3. Regression coefficients in the five predictive models

Notes: Outcome: number of expropriated farms, standard error in parentheses

* p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001

As seen in Map 1 of Figure 4, the farm expropriations policy mainly targeted land in the north and northeast, not in the south where the MST was founded and was better organised. Land in the midwest was also highly targeted, hitting landed elites at the heart of agribusiness. This distribution appeared as a belt of expropriations around southern metropolises, such as Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. Plot A in Figure 4 shows how the number of predicted expropriations is higher in states sending more migrants to other states in the 1990s. Plot B shows how Lula's performance had a similar effect, all other covariates kept constant at their mean. More importantly, the predicted number of expropriations is significantly higher when both the number of emigrants sent by the state and Lula's vote ratio are high, as seen in Plot C. The positive interaction between these two covariates is highly consistent with the policy goals of the Right, as shown with process tracing in the previous section.

In numbers, the models describe how for every 1,000 new migrants an additional farm was expropriated in their state of origin, considering the entire period (see Table 3). By the same token, for every point increase in the ratio of votes favouring Lula an additional farm was expropriated in the same period. Both effects are robust to changes in model specification. The effect of migration and of Lula's vote ratio are robust to controlling for poverty levels, the number of unproductive farms, the level of rural violence, MST occupations, press coverage and the year of massacres (see coefficients of control covariates in Table A.1). In other words, the government privileged the expropriation of farms in the states with higher emigration rates and, within those, in the municipalities in which the Left performed better. Such targeting of farms was independent of the local demand for land, technical suitability for expropriation and rural violence. These results add strong evidence in favour of the theory that fear of crime and competition with the Left triggered the Right's sponsorship of agrarian reform.

Discussion and Conclusion

Three points of discussion derive from the evidence: How do these data inform our understanding of agrarian reform in Brazil? Do the causal mechanisms portrayed here apply to other cases of agrarian reform? What are the implications of these findings for understanding elite behaviour under distributive conflict?

In respect of agrarian reform in Brazil, the study shows how right-wing politicians conceived agrarian reform as a less costly policy to make metropolises safer for the rich (by reversing rural–urban migration), as well as instrumental for gaining competitive advantage against more redistributive left-wing challengers. The two mechanisms explain why right-wing parties (including those of strong conservative inclination) rallied around a flagship policy of the Left. Given that fear of crime and competition with the Left motivated right-wing majorities to regulate and implement agrarian reform, it can be inferred that the policy would not have been implemented in the absence of such motivations.

Previous explanations in the literature focused on two factors facilitating expropriations: public support for the MST following the two massacres of the mid 1990s and the generosity of compensation to land owners, which reduced resistance to the policy from landed elites.Footnote 67 I sustain that the massacres are important landmarks that shaped the agrarian reform process but cannot be assumed as its cause for they occurred after the policy's approval in Congress. Regarding landed elites, the evidence suggests that their acceptance of agrarian reform has been largely overestimated by the literature.

Overall, the public statements by both right-wing and left-wing elites, Cardoso's personal notes in his audio diary, the interview and survey data (see Footnote notes 35–Footnote 7) and the distribution of expropriations constitute a body of evidence that is highly expected if the causal argument presented in this study is correct and extremely unlikely in light of alternative explanations (see the online supplement for the estimation of likelihood ratios). The study therefore contributes to the scholarship on agrarian reform in Brazil by portraying the causal mechanisms that explain why right-wing parties sponsored the policy.

The second point of discussion concerns whether the causal argument applies to other cases of agrarian reform under right-wing or conservative administrations. Two potential candidates in this regard are the agrarian reforms of Chile in the 1960s and of Colombia in the late 1980s and 1990s. Felipe González shows how Christian Democrats in Chile sponsored agrarian reform in the 1960s in order to compete with the Partido Socialista de Chile (Chilean Socialist Party), a left-wing challenger feared by urban elites.Footnote 68 Michael Albertus and Oliver Kaplan show how agrarian reform in Colombia targeted regions where left-wing guerrilla fighters were based.Footnote 69 Given that the conflict spilled over to urban areas through terrorism and kidnapping, it seems plausible that motivations parallel to those observed in Brazil were operating in Colombia.

Thirdly, regarding distributive conflict theory, the present study challenges the assumption that economic elites, and the right-wing parties representing them, act cohesively in defence of property rights. Right-wing parties can impose losses on minoritarian elites in order to reduce the costs to the broader set of elites, which problematises the idea of conservative parties as safe havens for the landholding classes.Footnote 70 To some extent, the Right in Brazil replicated the spirit of conservative modernisation described by Barrington Moore,Footnote 71 implementing social changes ‘from above’ in order to secure their privilege. But this version of conservative modernisation turned against the landed elites who had historically benefitted from it in Brazil and elsewhere.Footnote 72 It follows that elites should not be assumed as a monolithic group with mechanical solidarity ties, but rather as a heterogeneous group with potentially antagonistic preferences regarding property rights and redistribution.

The study reinforces the prediction that externalities of inequality and competition from left-wing parties push elites and right-wing coalitions to endorse redistributive policies.Footnote 73 The case of Brazil shows that these two mechanisms, previously analysed separately in the literature, are mutually reinforcing and therefore more effective when in interaction.

Finally, the study shows that it is relevant to ask which redistributive policies result from these causal processes triggered by the externalities of inequality. The fact that redistributing land constituted a high-gain/low-cost policy played a key role in ensuring the Right's commitment to agrarian reform. My results therefore indicate that the politics of cost allocation are key for understanding elite coordination in favour of redistribution.

Appendix

Figure A.1 illustrates the 1990–2005 crime wave. While the murder rate expresses generalised violence, targeting the poor much more than the rich, the rate of kidnappings is informative of the threat of crime to upper-class citizens.

Figure A.1. Homicides and kidnappings, 1990–2005

Note: Missing values are imputed for kidnappings using decade averages.

Sources: IPEA: http://ipeadata.gov.br/; Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais (National Institute for Space Research, INPE): https://www.gov.br/inpe/; Instituto de Segurança Pública (Institute for Public Safety, ISP): http://www.isp.rj.gov.br/; Caldeira, ‘Segurança pública e sequestros’.

Table A.1 shows regression coefficients for the control covariates included in the models outlined in Table 3.

Table A.1. Regression coefficients for controls in the four predictive models with controls

Acknowledgements

While carrying out this research I was fortunate to count on the intellectual generosity of Frances Hagopian, Tasha Fairfield, Lorenza Fontana, Ricardo Pagliuso, Jonas Pontusson, Lívio Silva-Müller, Jan Teorell, Agustín Goenaga, Oriol Sabaté, Laura Garcia and Elisa Reis. I benefitted from discussions about this project in the contexts of the REPAL conference, the Unequal Democracies project at the University of Geneva, the STANCE project at Lund University and early on at the regular Political Economy seminars at Harvard University. Finally, I thank JLAS’ editors and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive criticism and pertinent suggestions.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X23000044