Abstract

Climate change, globalization, and increasing industrial and urban activities threaten the sustainability and viability of small-scale fisheries. How those affected can collectively mobilize their actions, share knowledge, and build their local adaptive capacity will shape how best they respond to these changes. This paper examines the changes experienced by small-scale fishing actors, social and governance complexities, and the sustainability challenges within the fisheries system in Limbe, Cameroon. Drawing on the fish-as-food framework, we discuss how ineffective fishery management in light of a confluence of global threats has resulted in changes to fish harvesters’ activities, causing shortages in fish supply and disruptions in the fish value chain. The paper uses focus group discussions with fish harvesters and fishmongers to present three key findings. First, we show that changes in the fisheries from increased fishing activities and ineffective fishery management have disrupted fish harvesting and supply, impacting the social and economic well-being of small-scale fishing actors and their communities. Second, there are complexities in the fisheries value chain due to shortages in fish supply, creating conflicts between fisheries actors whose activities are not regulated by any specific set of rules or policies. Third, despite the importance of small-scale fisheries in Limbe, management has been abandoned by fishing actors who are not well-equipped with the appropriate capacity to design and enforce effective fishery management procedures and protections against illegal fishing activities. Empirical findings from this understudied fishery make scholarly contributions to the literature on the fish-as-food framework and demonstrate the need to support small-scale actors’ fishing activities and the sustainability of the fisheries system in Limbe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Small-scale fisheries (SSFs) contribute significantly to the food security, culture, livelihoods, and well-being of hundreds of millions of people (Weeratunge et al. 2014; Johnson et al. 2018; Stacey et al. 2019). In many locales, SSFs are critical to sustaining local food systems (Loring et al. 2019) and have the potential to play a much larger global role (Farmery et al. 2021), including in the emerging so-called blue economy (Ayilu et al. 2022; Okafor-Yarwood et al. 2022; Ayilu et al. 2023). Specifically, large amounts of fish from small-scale capture fisheries are being caught and consumed due to their nutritional value and easy access for coastal communities in low-income countries (Teh and Pauly 2018). Small and medium-scale aquaculture is also increasing in prevalence and importance, especially for people in low- and middle-income countries (Belton and Thilsted 2014; Santafe-Troncoso and Loring 2021). Despite these varied contributions of SSFs, most small-scale fishing communities are challenged by pressures from international markets, fisheries privatization, and competition from other economic activities in ocean space and for marine resources (Campling et al. 2012; Carothers and Chambers 2012; O’Neill et al. 2018; Bennett et al. 2021).

Growth in industrial fisheries has exposed many small-scale fishing communities to conflicts, such as with illegal and foreign fishing vessels and competition with large export-oriented fleets (Scholtens 2015; Saavedra-Díaz et al. 2015; Belhabib et al. 2019; Okafor-Yarwood 2019; Okafor-Yarwood et al. 2022). These challenges add to the persistent social, economic, and institutional problems being navigated by small-scale fishing communities, such as poverty and other social and ecological legacies of colonialism (Olson et al. 2014; Song et al. 2020). Notwithstanding these challenges, SSF communities have long mobilized through local actions and community-based initiatives to respond to threats reactively, proactively, and innovatively (Lowitt et al. 2020; Green et al. 2021; Freeman and Svels 2022), respond to systematic shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Stoll et al. 2021; Bennett et al. 2020), and pursue transformation in local food systems (Chan et al. 2021; Short et al. 2021; Arthur et al. 2022).

This paper examines the changes and complexities presently being navigated by SSF actors in Limbe, Cameroon. Limbe is a coastal city in Cameroon, Central Africa, with a long history of small-scale artisanal fishing. Landings in these fisheries are sold locally and cross-border to neighboring Gabon, Nigeria, and Equatorial Guinea. In Limbe, fishing contributes directly to the local food system by providing food and nutritional security and to livelihoods by creating jobs for both men and women across the fish value chain, i.e., fish harvesting, processing, distribution, and fish trade. However, despite their evident local and regional importance, research on these fisheries is sparse.

Like most SSFs in developing countries, fishing activities in Limbe are continuously being threatened by increasing maritime activities, illegal fishing, and competition for access between local artisanal and large-scale industrial fishing fleets (Beseng 2019; Beseng 2021). Also, the increased construction of oil rigs and the expansion of offshore oil drilling activities around traditional fishing grounds have further depleted the fishery’s ecosystem (Alemagi 2007). These challenges are compounded by a lack of robust fisheries governance and management and few existing structures to promote and support community participation (Beseng 2019). These challenges have directly affected the livelihoods of many fishery-dependent households through a reduction in a fish catch that led to the inability to meet local fish demand (The New Humanitarian 2022). In Limbe, the problem of fisheries and food system sustainability is becoming more pronounced as many important local fish species are becoming scarce, and an increase in price for certain common species such as barracuda (Sphyraena spp.) (Nyiawung et al. 2022).

Below, we draw on the fish-as-food framework to explore challenges and complexities within the fisheries system in Limbe (Levkoe et al. 2017; Lowitt et al. 2020a, Lowitt et al. 2020b). With data gathered through a series of focus groups, we argue that changes in the fisheries system caused by social, economic, and environmental stressors — including ineffective governance/management — create complexities that permeate the entire fish value chain. First, we offer background on the conceptual framing of the paper, and the case study context, followed by a report on focus group discussions with fish harvesters and fishmongers. Then, we proceed to explore the fish food system changes, the fish value chain complexities, and the challenges of ineffective governance. In conclusion, we suggest that there is an opportunity for actors to collectively engage in the management of the fishery and identify the need for more social-ecological research for this understudied fishery.

Theoretical framework

Fish-as-food framework

The concept of “food systems” invokes a diverse and ever-growing body of literature that continues to be broadened and shaped to include economic, ecological, and human dimensions of how people procure, share, prepare, and consume food (Erickson 2008; Ericksen et al. 2010; Béné et al. 2019; Short et al. 2021). When discussing food security and food sovereignty, current trends in food systems research include the question of sustainability, justice, and decision-making processes, especially for marginalized communities (Eakin et al. 2017; Tezzo et al. 2021). The High-Level Panel of Experts on Food Systems (HLPE, 2017) reported that globalization, increasing urban sprawl, and resource grabbing are other key issues that must be considered when analyzing food systems and any socio-technical transitions occurring within them. Moreover, there is growing recognition that when considering social and ecological outcomes, how food systems are organized is more important than the specifics of the practices and technologies being used (Loring 2021). Additionally, there have been a number of calls in research and policy to more explicitly include seafood in the food system discourse (Olson et al. 2014; Levkoe et al. 2017; Tezzo et al. 2021; Naylor et al. 2021; Farmery et al. 2021).

For example, Levkoe et al. (2017) suggest a fish-as-food framework to explore how changes within a fishery have broader social, economic, and ecological impacts beyond the immediate activities of small-scale fisheries actors and also lead to changes within the fishing communities and their food sovereignty. Whereas much research and policy on fisheries adopt a resource-oriented perspective, the benefit of this fish-as-food framing is that it draws out the numerous ways that fish and fishing activities contribute to social, economic, cultural, well-being, and decision-making through contributions across the fish value chain and local food system (Loring et al. 2013; Love et al. 2017; Levkoe et al. 2017). There is also an inherent normative dimension to the fish as food framework in that it invokes food sovereignty as a political ideal or theory of change against which the features of fisheries ought to be evaluated and, if necessary, reformed (Levkoe et al. 2017).

The fish-as-food framework has been used to discuss fisheries in different geographical locales and contexts (e.g., Lowitt 2013; Tezzo et al. 2021). Within the broader conceptualization and positioning of fish in the food system discourse and aspects of food sovereignty, Lowitt et al. (2020) identify three essential components of the fish-as-food framework: (1) fish harvesting — constituting all activities from fish stock assessment, fish harvest rule/licensing, and other ecosystem-based management; (2) fisheries value chain — comprising of all the activities from fish processing, marketing, distribution, and consumption; and lastly, (3) governance and decision making — which speaks to the rulemaking process and power division within the fisheries and the interactions among actors in the food system. Tezzo et al. 2021 through a systematic review applied this framework to demonstrate factors that shape a change from capture fishery value chain activities to aquaculture in Asia. Also, Soma et al. (2021) used this framework to show how a broad understanding of the institutional structures influencing fish value chain activities is important to avoid challenges when establishing a new rural–urban fish food system in Kibera, Kenya.

Here, the fish-as-food framework provides a practical vocabulary to interrogate that ongoing changes and challenges being experienced by people in Limbe are not limited to fish as an economic commodity but rather cascade across other social and ecological aspects of fishing actors and their communities. Based on our analysis, we also offer insight into possible policy interventions that could improve outcomes and security of the fisheries system in Limbe to changes and existing complexities.

Methodology

Locale

This paper focuses on the coastal city of Limbe in Cameroon. In this city, small-scale fishing for multiple species of fish from the Atlantic Ocean has been carried out for several decades, providing food and livelihood for many local and migrant inhabitants (Fig 1). Limbe is located in Fako Division in the Southwest Region, with about 72,109 inhabitants (World Population Review 2022). The city was known as Victoria during the British, Dutch, Portuguese, and German colonial era but was changed to Limbe in 1987 through a Presidential decree (ApricaNomad 2020). The city is adjacent to the Atlantic Ocean and was used as a colonial route for many western explorers/colonizers to access new territories further inland. These colonial activities brought development to the city in terms of engineered roads and other infrastructures.

Unlike many other coastal small-scale fishing communities in the developing world, Limbe is considered an urban center, hosting the country’s only oil refinery company — SONARA. The city is developed with basic amenities such as potable water, electricity, and intra-city transportation facilities. The local inhabitants are the Bakwerians, whose traditions and culture are linked to the ocean with a unique coastal lifestyle and food (Ndille and Belle 2014). However, over the years, people have migrated to Limbe from other areas, both rural and urban, for jobs, including fishing. Some work as laborers for the biggest agricultural company in the country — the Cameroon Development Corporation (CDC), with headquarters in Limbe. Also, many migrant fish harvesters from neighboring countries and their families have migrated to Limbe, playing an active role in Cameroon’s fishing industry.

Fishing in Limbe is carried out by a few local indigenous inhabitants and many migrant fish harvesters from Nigeria, Ghana, Togo, and Benin. Fishers’ fish using carved wooden boats mounted with motor-engine or traditionally operated with wooden paddles. Occasionally, some boats carry coolers to preserve their catch offshore. Additionally, at times operating alone, fish harvesters set their nets mostly overnight on specific “traditional” fishing days.

The fishery is open access and multispecies; harvesters do not target specific species but catch and sell whatever they catch in their net. The catch is sold fresh and processed in open markets at the beachfront and nearby local markets. Fish price is determined on-site by fishers and generally influenced by local demand for the available fish. Fishmongers — predominantly the wives of migrant fish harvesters and other local women — buy the fresh fish, process them by drying them using smoke and a charcoal oven, and then sell them to market hawkers. However, some fishmongers process the fish fresh and sell it themselves at the local market. Fish traders sell their fish locally and across borders, just like in most other coastal west and central African countries, through formal and informal cross-border trade (Ayilu and Nyiawung 2022). In Limbe, fresh fish is also grilled and sold at beach markets (boucareau) or other small locales within the city, e.g., restaurants and beer parlors.

The fishery sector in Cameroon falls under the Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries, and Animal Husbandry, which operates regional delegations across the country. However, the ministry seldom trains personnel, does not regulate fishing activities at the beachfront, and has limited surveillance and monitoring infrastructure (The New Humanitarian 2022). Usually, the local city council is tasked with managing the affairs of the beach. Still, these activities are often quite limited, focusing on collecting taxes from local businessmen and women to raise revenue for the city council.

In recent years, with the entrance of foreign industrial fishing fleets from China and elsewhere, fish harvesters have been experiencing a significant reduction in their fish catch and, at times, conflicts between local and foreign fishers (Beseng 2019). Like in other areas, these foreign fleets are engaged in industrial and unsustainable fishing methods and compete with local fishers for the available fish resources (Scholtens 2016). Also, there has been an increase in marine activities, such as establishing more oil rigs and shipping activities in traditional fishing grounds. These industrial activities displace fishers from areas required for their livelihoods and further threaten the health of the fishery resources; collectively, these challenges lead some fishers to consider exiting the fishery (The New Humanitarian 2022). Moreover, other activities by local community members, specifically mangrove harvests, may also contribute to the degradation of the local ecosystem, including important fish habitats.

Data collection and analysis

The research was carried out in the coastal city of Limbe with fish harvesters and fishmongers in three locales: Down Beach, Idenao Wharf, and the New Town Open Market, the three most active fishing locales in Cameroon. Here, most fish harvesters, fishmongers, and their families live close to the ocean. Most fishmongers use their kitchen/home to process, dry/smoke, and package fish for the market.

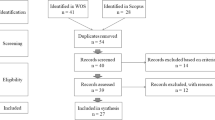

Given the lack of research in this area to build on, we adopted a qualitative and exploratory research design, using focus group discussions with active fish harvesters and fishmongers and supplementing these with a review of gray literature and documentaries from verified news outlets. The research was conducted in September and October 2020. Morgan (1997) argues that focus groups help provide in-depth qualitative data for research with participants having different views on a particular topic. Focus groups were held in pidgin English, a common language spoken by people in these communities, and then translated into English.

A total of 48 participants (20 fish harvesters and 28 fishmongers) participated in six different focus groups, with participants recruited via a semi-random, happenstance approach, i.e., meeting them directly at the beachfront and fish market at the three locales (see Table 1). Participants had, on average, 10 years of fishing experience. The youngest participant was 31 years old, and the oldest was more than 60. Three of the focus group had a mix of fish harvesters and fishmongers, one with only fish harvesters and two with only fishmongers. In this fishery, women are the only fishmongers, although they often hire men to help with fish cleaning, processing, and distribution.

The focus group discussions explored different changes and challenges participants in local fisheries are experiencing, as well as the factors promoting or hindering their ability to participate in and mobilize local management actions to respond to changes or challenges as they arise. The focus group discussion questions were open-ended, giving room for participants to discuss and elaborate in detail their opinion on any of the questions asked (see supplementary material for interview guide). After the focus groups, all notes and recorded interviews were translated, transcribed, and open coding was done using NVIVO 12 software for qualitative analysis. We then conducted axial coding, i.e., coding for emergent themes (Scott and Medaugh 2017) evident in the open codes. Several themes emerged from the research; we present these themes organized within the three main components of the fish as food network noted above: governance/management, the fish value chain, and the fishery itself.

Results

In this section, we present results from our discussions with small-scale fishing actors in Limbe and categorize our findings based on Lowitt et al.’s (2020) three key elements of the fish-as-food framework, i.e., fish harvesting, complexities in the fish value chain, and governance/decision-making challenges.

Changes in the fishery/food system challenge local fish harvesting

Fish harvesting in Limbe is open access, with limited government regulations and policies guiding fishing activities. The coastal city of Limbe is known throughout the whole country as a fishing hotspot, with many people engaged in the fishery’s value chain. In the early 2000s, fish was abundant at the beachfront and very cheap. Locals would buy fish, process it themselves, and send it to family members in large quantities in neighboring urban and rural areas. However, this changed during the early 2000s when foreign industrial fishing fleets became more active in Limbe, using large industrial trawlers and advanced fishing methods. This is coupled with the construction of more oil rigs around traditional fishing areas to fuel the only oil refinery company in the country (SONARA), located on Limbe’s coast. Participants report that these industrial economic activities and overfishing have directly affected the ecological well-being of the fisheries system. For example, fish harvesters and fishmongers cannot get enough fish to supply their customers. One participant explained, “… no, the quantity of fish has greatly reduced. If one goes to the dockyard and manages to find a little quantity of fish to sell and be able to feed our children for a week, then we are lucky and happy.” (Fishmonger, FGD 2).

Participants also shared that there has been a constant reduction in the quantity of their catches over the years. One explained,

We can’t get up to half the quantity of fish we used to catch years back; we can stay one week in water and still not make enough catch. Meanwhile, in the early days, we stay a maximum of three days in water, and the harvest is much (Fish harvesters, FGD 2).

Another participant supported this assertion by adding,

Yesteryears, we used to have fish until we threw some. Even during rainy seasons and peak fish season, we still don’t have enough. Last year’s and this year’s supply is the same, but we used to have more than enough in those days. Maybe it’s due to the presence of Chinese [fishing boats] in our waters (Fisherman, FDG 1).

There are changes in the fisheries system in Limbe due to poor management and overexploitation of fishery resources. The privatization and increased ocean economic activities supported by the government have impacted ecological sustainability and the access local small-scale actors have to traditional fishing grounds since they now compete with industrial fishing vessels. To satisfy their customers, many fish harvesters reported that they have instead started buying fresh fish directly at sea from the large Chinese fishing fleets and then selling them at a slightly higher price onshore (The New Humanitarian 2022). Limbe has a complete lack of rules surrounding fish harvesting and licensing. Additionally, there is a lack of fish stick assessment and ecosystem-based management. These gaps in fishery management have led to the continuous depletion of the fishery ecosystem and a reported decline in fish catch volumes.

Complexities in the fish value chain

Limbe’s fish-harvesting challenges affect fish supply and activities along the fish value chain. As mentioned earlier, fishing in Limbe is typically done by migrant fish harvesters from Nigeria and Ghana and a few locals. However, in Limbe, fishmongers — predominantly women — dominate fish processing and fish trade. Almost all fish caught by migrant fish harvesters are given to their female partners, who then coordinate how the fish would be processed and sold to other fishmongers. However, this system has often led to fish supply crises, considering the challenges fish harvesters are reportedly facing with accessing and harvesting fish. These changes have resulted in complexities in the fish value chain. For example, some fishmongers discussed how they are experiencing a disrupted fish supply, as fish harvesters have decided to supply their limited fish catch to their female partners before any other person. One fishmonger, for example, explained,

We realized that some of the reason for the shortages in fish supply was the fact that fish harvesters supply almost all their fish catch to their women and leave us [other fishmongers] without fish, and we end up buying from their women at a higher price (Fishmonger, FGD 4).

Fish harvesters started giving their catch to their female partners when the quantity of fish began to reduce while demand kept increasing. This approach has changed the fish value chain as fishmongers who usually buy directly from fish harvesters when their fishing boats arrive on shore must instead buy from the female partners of fish harvesters. A fishmonger supported this by explaining that “… fish harvesters supply their women and give us scrapes [low-value fish]” (Fishmonger, FGD 6). Also, some fishmongers are now forced to create personal connections with fish harvester’s female partners for fish supply. However, fishmongers were forced to react to these growing complexities in fish supply. They noted that “… we gathered and marched to the Delegation of Fisheries and reported, and a solution arrived: fish harvesters should supply one Cameroonian woman after every five migrant women. We were happy with the idea, which helped us” (Fishmongers, FGD 5).

Nevertheless, fish shortages and supply remain a problem in the fisheries system in Limbe. Shortages of fish have also made fishmongers resort to some response strategies. A participant noted, “when fish is scarce, we buy what is available, we change the species of fish we buy. Now we have started buying from the cold store, which is more expensive” (Fishmonger, FGD 6).

From discussions with fishing actors, the demand for fish is based on taste and preference, with many fish consumers in Cameroon preferring to buy fish caught from the sea compared to other sources (fish farms or cold stores). This preference is in line with other studies conducted by Lowitt (2013), which show that people living on the west coast of Newfoundland prefer locally caught seafood rather than imported ones. Moreover, many fishmongers in Limbe expressed dissatisfaction with selling fish from cold stores. One fishmonger at New Town market made the following assertion, “the cold store fish is different from the sea fish; for instance, the Strong Kanda we buy from cold stores produces more oil upon smoking compared to the Strong Kanda we get from the beachfront” (Fishmonger, FGD 5). Also, participants noted that “they rarely go to the cold store because the way we buy from the cold store is different from how we buy from the beach and cold store is more expensive” (FGD, 6). This statement is true as fishmongers at the open market on the beachfront can bargain and influence the price of fish they buy compared to the standard and fixed prices at the cold store. Moreover, fishmongers also noted that “… their customers believe that fish from the cold store is not as tasteful, and they don’t buy it as much as those from the sea” (FGD 3). Whether the fish is from the sea or a cold store, a participant explained that “… when fish is scarce, we buy expensive and sell expensive ... yes, the consumer ends up paying the price for fish scarcity” (FGD 1).

Finally, another issue affecting local fish supply is the increased demand for fish from neighbouring countries like Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, and Nigeria. Like in most other West African countries, fish are supplied through formal and informal cross-border trade to their customers and businesses (Ayilu and Nyiawung 2022). Fish traders make more money through cross-border fish trade than when they sell locally.

Governance challenges hinder effective management

Governance and decision-making are essential components of the fish-as-food framework. Poor fishery management has been presented to affect fish harvesting and complexities in the fish value chain in Limbe. No existing institutions actively regulate fishing activities at Cameroon’s local/community level. Fisheries in Cameroon fall under the Ministry of Livestock, Fisheries, and Animal Husbandry, represented at the national and regional levels by appointed government officials. The small-scale fishery sector has been abandoned despite its contribution to the livelihoods of fishing actors and their communities. Participants in the research raised multiple weaknesses in fishery management coupled with a lack of formal and informal institutions coordinating fishing activities in Limbe. Fishing along the West and Central African coastline constitutes a mix of local indigenous and migrant fisherfolks with diverse ethnicities (Njock and Westlund 2010; Binet et al. 2012). According to a local Cameroonian fisher, people from neighboring Nigeria and Ghana make up a more significant number of fish harvesters, which, together with their female partners, dominate fishing activities in Limbe. Typically, fewer Cameroonians are involved in direct offshore fishing, with many considering it a stressful activity. In one focus group discussion at Idenao, a fish harvester made the following assertion,

I am a Cameroonian; we are not used to fishing. The Ghanaians and Nigerians do fish here. Cameroonians only struggle to learn and cope with the stress of fishing. I would not love my child to endure that stress (Fisherman, FGD 1).

With the lack of rules and governance structures, there are constant conflicts within the fishery system between locals and migrant fisherfolks, principally due to ethnic differences. Local ethnic differences and associated social tensions have been reported to affect often how actors interact in the fishery system (Jentoft and Søreng 2017). Limbe, as earlier noted, is made up of the Bakwerians, the Indigenous sawa people whose ancestors have lived and cared for the ocean and land for several generations. Interviewees across all the research sites who are not native Bakwerians shared how they can only catch specific fish species and fish in particular fishing areas. A local Bakwerian fish harvester confirmed this, saying

Strangers [referring to migrant fish harvesters] catch only Bonga (Ethmalosa fimbriata) and Strong Kanda (Sardinella maderensis), while we the natives catch grouper (Epinephelinae spp.) and barracuda (Sphyraena spp.). The net type and size determine the fish species caught. Hence, we [natives] can satisfy our local women better (Fish harvester, FDG 3).

Although the native Bakwerians, by virtue of their territorial/traditional land/sea rights, might seem to oversee what happens in the fishery besides the government, our discussions with fish harvesters and fishmongers showed otherwise. Participants noted that there is no coordination between small-scale actors to set rules and manage their fishing activities. For example, in a focus group discussion at Down Beach, one participant explained,

No meeting since 1992. Members don’t even support one another. If you fall sick, you are on your own. Talk less about the Chinese issues we are currently facing. No fish harvester cares about you. We are not united like the Nigerians who have small meetings to address their issues (FGD 4).

Also, one elderly fish harvester added,

… we used to be united, but when fish harvesters who were driven from Manawah Bay came here, they started causing problems and disunited us with hatred and jealousy … hence we have no meeting or association as far as the Bakwerian fish harvesters are concerned (Fish harvester, FGD 4).

However, a few fish harvesters reported to us some personal actions they are implementing to support the sustainability of the fisheries. A fish harvester at Idenao did mention in a focus group discussion that “… we agree to stay at home and not to go fishing for about two weeks to one month, depending on the gravity of the shortage. After the fasting period, we resume fishing and experience an increase in our catch” (FGD 1). However, with no specific fish harvesting rules, the problem of fish sustainability abounds.

Finally, some interviewees also expressed frustrations with how fishing has been carried out in Limbe over the years, including the increasing activities of foreign fleets. There have been several conflicts between foreign fishing fleets and locals. However, the government seems to be overlooking the cries of the local fish harvesters, as a participant noted that “… we have gone to the government until we are tired … no solution … Chinese are sweeping the sea off fingerlings and not allowing them to grow” (FDG 2). Moreover, participants also explained that no one regulates fishing activities “… we go into the water anytime we want, no one stops us. We have communal days like every two weeks when we don’t go into the water” (FGD 1). These results show how the social complexity of the fishery and the disconnections between different groups of actors make the management and sustainability of the fishery more complex.

Discussion

Increased industrial fishing, expansion in offshore maritime activities, reduced fish catch quantities due to overfishing, and ineffective governance structures present myriad social, economic, and ecological challenges for small-scale fishing actors and their communities. The results demonstrate that actors in the fisheries system in Limbe are experiencing changes and complexities in the fish value chain, which affects not just their social and economic well-being but also their food sovereignty; we see this, for example, in how fisheries are losing control over how prices are set, people needing to rely on less desirable fish from the store, and the emerging pressures to export fish rather than sell it in local markets.

While SSF actors in Limbe still make critical contributions to the local food systems, which can be a locus of sovereign power to self-organize, we find three categories of threats that, if unaddressed, will further erode the potential of local fisheries to support food security and sovereignty These are the following: (1) substantive changes due to ineffective fisheries management for fish harvesting have resulted in overfishing, increased competition for fishery resources between SSF actors and industrial fishing fleets, and disruption in fish access and supply in Limbe, (2) shortages in fish supply due to poor management and disconnection among SSF actors creates complexities in the fish value chain, and (3) limited governance institutions undermine SSF actors’ ability to participate and engage in fisheries management. We discuss each below and then conclude by presenting the need for local small-scale actors to utilize their sovereign power to institute fishery management practices that support their social and economic well-being.

First, fish harvesters face numerous intersecting complications, especially with the increasing number of industrial fishing vessels and overfishing. The absence of fish harvesting rules has resulted in the rapid destruction of the fishery’s ecological system and overexploitation by large industrial fishing vessels at the disadvantage of SSF actors, who struggle to access important traditional fishing grounds. The number of fish harvesters has also increased over time despite a continuous decline in fishery resources. Fish harvesters spend more time at sea to catch a reasonable quantity of fish that can fetch them income to meet their needs. Also, increased competition over ocean space for other economic activities has significantly affected fishing, forcing small-scale fish harvesters to abandon traditional fishing grounds. All these changes have reportedly set in new pressures on the fisheries system and led to increased vulnerability of SSF actors. Indeed, there are echoes here of the marginalization-degradation hypothesis in political ecology, which proposes a feedback loop wherein marginalized people are perversely incentivized to put pressure on declining resources, which worsens their situation (Nayak et al. 2014). With no specific fish harvest rules and no protection against foreign fleets, small-scale fish harvesters constantly compete and are challenged to meet local fish demand. This has led to further disruptions along the fish value chain in Limbe. Furthermore, consistent with Lloret et al.’s (2012) study, which shows that adequate knowledge of fish stock helps promote better fishery management, with no fish stock assessment procedures or ecosystem-based management in Limbe, fishery sustainability remains a problem.

Second, the social complexity and disconnectedness inherent in the fishery system among SSF actors increase the complexities in the fish supply chain, which is exacerbated by shortages in fish supply. The fisheries system in Limbe, as earlier mentioned, is comprised of migrant fisherfolks from neighboring Nigerian, Ghana, and local Cameroonians with distinct ethnicities, cultures, and languages. As the fishery resources continue to deplete, local Indigenous Bakwerians fish harvesters compete with migrant fish harvesters for access to productive fishing grounds, including what kind of fish to catch and net sizes. This is in addition to the already existing challenges with industrial fishing vessels. These competitions have often led to conflict over harvesting and the supply of fish to fishmongers and consumers. Fish harvesters prefer to supply their catch to people from the same ethnic group before any other person. Such a situation creates small bubbles of disconnected actors who are focused on the social and economic well-being of their tribal members. As presented in the “Results” section, migrant fish harvesters prefer to give their catch to their female partners, who then sell to other local Cameroonian fishmongers. This action alone has often resulted in conflicts and fights around the beachfront, which has needed the intervention of security officers. Tribal members’ main interest is to sustain their livelihoods, with most actors unwilling to cross paths. This is in line with Pomeroy et al.’s (2007) research, which shows that there are often conflicts between user groups in SSFs with diminishing fish stocks. Moreover, social dynamics and tensions increase the marginalization and poverty experienced in many SSF communities (Scholtens and Bavinck 2018, Nayak et al. 2014). Researchers have reported these social tensions and conflicts between diverse groups make the governance of fisheries systems more challenging (Lau and Scales 2016; Song et al. 2018). However, more research is needed to explore these ethnic and cultural complexities between local and migrant fisherfolks in the fishery system in Limbe.

Third, state-level governance and decision-making in the fisheries system in Limbe are largely absent and ineffective. Fisherfolks in Limbe depend on their experiences and knowledge of the fishery system to carry out their activities, just like in other low-income SSF settings (Espinoza-Tenorio et al. 2013). As noted in the results, no one monitors or regulates fishing activities, and there is no defined set of rules for fish actors to follow. Consequently, fishers go out to see and harvest whatever fish they find whenever they want. Fishers only realize changes in the fisheries when their fish catch is low and when they spend longer at sea and cannot meet consumer demand. Scholars have argued that good institutional structures and policies create opportunities for local actors to work together and find solutions to existing challenges, enhance the food system’s sustainability, and manage their fishery (Chuenpagdee et al. 2013; Song et al. 2018).

Despite these challenges, Limbe’s SSFs continue to be critical to the social and economic well-being of SSF actors and their communities. There is a definite need for SSF actors to be empowered to collectively share local knowledge, search for solutions, and improve their capacity and capabilities to support the sustainability of the fisheries system in Limbe. Building adaptive capacity among SSF actors has been reported to increase local responses and resilience to shocks and stressors (Cinner et al. 2018; Freduah et al. 2018). With increasing global change resulting from climate change, industrialization, and the globalization of food systems, SSF actors will arguably need to be empowered to participate in the decision-making and governance of SSFs, while ensuring a sustainable fishery and healthy community (Arthur et al. 2021). This also includes a call for actors to increase their efforts to share resources, implement a governing system, and participate in conservation activities (Bodin et al. 2014).

Conclusion

The increasing threats from global change, i.e., globalization, urbanization, and industrialization, multiply the layers of changes and challenges faced by people in coastal small-scale fishing communities already suffering from a degrading fisheries ecosystem and declining fish stocks. Ultimately, the institutionalization of effective fishery governance systems contributes to helping communities build resilience to existing environmental stresses and unforeseen shocks. Empowering coastal fishing communities, where actors can collectively mobilize their knowledge and resources through co-management, for example, has been proven to enhance the sustainability of fishery resources (Cohen et al. 2015; Trimble and Berkes 2015; Tilley et al. 2019). This paper uses the fish-as-food framework to analyze an understudied fisheries system in Limbe, Cameroon, qualitatively. Here, the lack of an effective fishery management system, increased industrial fishing, and other ocean-related economic activities have been reported to affect fish harvesting and disrupt fish supply by small-scale fishers. These shortages in fish supply further affect activities along the fish value chains, impacting fisherfolks’ and their communities’ social and economic well-being. Additionally, Limbe’s poor fishery governance system makes fishing actors’ activities in this system ungovernable — no one sets the rules on how the fishery should be managed or ensures its sustainability. Lastly, many actors along the fish value chain rely solely on the fishery resources for their livelihood. This paper also provides much-needed background on an understudied fishery that would greatly benefit from continued support and policy interventions, especially given the increased global pressures on ocean resources associated with the so-called Blue Economy. The paper further underscores the importance of research framed in terms of social-ecological systems to understand better existing challenges and possible directions or next steps to support and organize actors’ actions in Limbe’s small-scale fishery system.

References

Alemagi, Dieudonne. 2007. The oil industry along the Atlantic coast of Cameroon: Assessing impacts and possible solutions. Resources Policy 32 (3): 135–145.

ApricaNomad. 2020. Limbe in Cameroon. https://apricanomad.com/limbe-in-cameroon-discover/. Accessed 10 April 2022.

Arthur, Robert I., Daniel J. Skerritt, Anna Schuhbauer, Naazia Ebrahim, Richard M. Friend, and U. Rashid Sumaila. 2022. Small-scale fisheries and local food systems: Transformations, threats and opportunities. Fish and Fisheries 23 (1): 109–124.

Ayilu, Raymond K., Michael Fabinyi, Kate Barclay, and Mary Ama Bawa. 2023. Blue economy: Industrialisation and coastal fishing livelihoods in Ghana. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries: 1–18.

Ayilu, Raymond K., and Richard A. Nyiawung. 2022. Illuminating informal cross-border trade in processed small pelagic fish in West Africa. Maritime Studies 21 (4): 519–532.

Ayilu, Raymond K., Micheal Fabinyi, and Kate Barclay. 2022. Small-scale fisheries in the blue economy: Review of scholarly papers and multilateral documents. Ocean & Coastal Management 216: 105982.

Belhabib, Dyhia, U. Rashid Sumaila, and Philippe Le Billon. 2019. The fisheries of Africa: Exploitation, policy, and maritime security trends. Marine Policy 101: 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2018.12.021.

Béné, Christophe, Peter Oosterveer, Lea Lamotte, Inge D. Brouwer, Stef de Haan, Steve D. Prager, Elise F. Talsma, and Colin K. Khoury. 2019. When food systems meet sustainability–Current narratives and implications for actions. World Development 113: 116–130.

Bennett, Nathan J., Elena M. Finkbeiner, Natalie C. Ban, Dyhia Belhabib, Stacy D. Jupiter, John N. Kittinger, Sangeeta Mangubhai, Joeri Scholtens, David Gill, and Patrick Christie. 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic, small-scale fisheries and coastal fishing communities. Coastal management 48 (4): 336–347.

Bennett, Nathan J., Natalie C. Ban, Anna Schuhbauer, Dacotah-Victoria Splichalova, Megan Eadie, Kiera Vandeborne, Jim McIsaac, et al. 2021. Access rights, capacities and benefits in small-scale fisheries: Insights from the Pacific Coast of Canada. Marine Policy 130: 104581.

Beseng, Maurice. 2019. Cameroon’s choppy waters: The anatomy of fisheries crime in the maritime fisheries sector. Marine Policy 108: 103669.

Beseng, Maurice. 2021. The nature and scope of illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing and fisheries crime in Cameroon: Implications for maritime security. African Security 14 (3): 262–285.

Binet, Thomas, Pierre Failler, and Andy Thorpe. 2012. Migration of Senegalese fishers: A case for regional approach to management. Maritime Studies 11(1): 1–14.

Bodin, Örjan, Beatrice Crona, Matilda Thyresson, Anna-Lea Golz, and Maria Tengö. 2014. Conservation success as a function of good alignment of social and ecological structures and processes. Conservation Biology 28 (5): 1371–1379.

Campling, Liam, Elizabeth Havice, and Penny McCall Howard. 2012. The political economy and ecology of capture fisheries: Market dynamics, resource access and relations of exploitation and resistance. Journal of agrarian change 12(2-3): 177–203.

Carothers, Courtney, and Catherine Chambers. 2012. Fisheries privatization and the remaking of fishery systems. Environment and Society 3 (1): 39–59.

Chan, Chin Yee, Nhuong Tran, Kai Ching Cheong, Timothy B. Sulser, Philippa J. Cohen, Keith Wiebe, and Ahmed Mohamed Nasr-Allah. 2021. The future of fish in Africa: Employment and investment opportunities. PloS one 16 (12): e0261615.

Chuenpagdee, Ratana, Svein Jentoft, Maarten Bavinck, and Jan Kooiman. 2013. Governability–New directions in fisheries governance. In Governability of fisheries and aquaculture, 3–8. Dordrecht: Springer.

Cinner, Joshua E., W. Neil Adger, Edward H. Allison, Michele L. Barnes, Katrina Brown, Philippa J. Cohen, Stefan Gelcich, et al. 2018. Building adaptive capacity to climate change in tropical coastal communities. Nature Climate Change 8 (2): 117–123.

Cohen, Philippa, Louisa Evans, and Hugh Govan. 2015. Community-based, co-management for governing small-scale fisheries of the Pacific: A Solomon Islands’ case study. In Interactive governance for small-scale fisheries, 39–59. Cham: Springer.

Eakin, Hallie, John Patrick Connors, Christopher Wharton, Farryl Bertmann, Angela Xiong, and Jared Stoltzfus. 2017. Identifying attributes of food system sustainability: Emerging themes and consensus. Agriculture and human values 34 (3): 757–773.

Ericksen, Polly J. 2008. Conceptualizing food systems for global environmental change research. Global environmental change 18 (1): 234–245.

Ericksen, Polly, Beth Stewart, Jane Dixon, David Barling, Philip Loring, Molly Anderson, and John Ingram. 2010. The value of a food system approach. Food security and global environmental change 25: 24–25.

Espinoza-Tenorio, Alejandro, Matthias Wolff, Ileana Espejel, and Gabriela Montaño-Moctezuma. 2013. Using traditional ecological knowledge to improve holistic fisheries management: Transdisciplinary modeling of a lagoon ecosystem of southern Mexico. Ecology and Society 18 (2).

Farmery, Anna K., Edward H. Allison, Neil L. Andrew, Max Troell, Michelle Voyer, Brooke Campbell, Hampus Eriksson, Michael Fabinyi, Andrew M. Song, and Dirk Steenbergen. 2021. Blind spots in visions of a “blue economy” could undermine the ocean’s contribution to eliminating hunger and malnutrition. One Earth 4 no. 1 (2021): 28–38.

Freduah, George, Pedro Fidelman, and Timothy F. Smith. 2018. Mobilising adaptive capacity to multiple stressors: Insights from small-scale coastal fisheries in the Western Region of Ghana. Geoforum 91: 61–72.

Freeman, Richard, and Kristina Svels. 2022. Women’s empowerment in small-scale fisheries: The impact of Fisheries Local Action Groups. Marine Policy 136: 104907.

Green, Kristen M., Jennifer C. Selgrath, Timothy H. Frawley, William K. Oestreich, Elizabeth J. Mansfield, Jose Urteaga, Shannon S. Swanson, et al. 2021. How adaptive capacity shapes the adapt, react, cope response to climate impacts: Insights from small-scale fisheries. Climatic Change 164 (1): 1–22.

HLPE. 2017. Nutrition and food systems. A report by The High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition. Rome, Italy.

Jentoft, Svein, and Siri Ulfsdatter Søreng. 2017. Securing sustainable Sami small-scale fisheries in Norway: Implementing the guidelines. In The small-scale fisheries guidelines, 267–289. Cham: Springer.

Johnson, Derek S., Tim G. Acott, Natasha Stacey, and Julie Urquhart, eds. 2018. Social wellbeing and the values of small-scale fisheries. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Lau, Jacqueline D., and Ivan R. Scales. 2016. Identity, subjectivity and natural resource use: How ethnicity, gender and class intersect to influence mangrove oyster harvesting in The Gambia. Geoforum 69: 136–146.

Levkoe, Charles Z., Kristen Lowitt, and Connie Nelson. 2017. “Fish as food”: Exploring a food sovereignty approach to small-scale fisheries. Marine Policy 85: 65–70.

Lloret, J., E. Faliex, G.E. Shulman, J.A. Raga, P. Sasal, M. Muñoz, M. Casadevall, A.E. Ahuir-Baraja, F.E. Montero, A. Repullés-Albelda, and M. Cardinale. 2012. Fish health and fisheries, implications for stock assessment and management: The Mediterranean example. Reviews in Fisheries Science 20 (3): 165–180.

Loring, Philip, and A. 2021. Regenerative food systems and the conservation of change. Agriculture and Human Values 39 (2): 701–713.

Loring, Philip A., S. Craig Gerlach, and Hannah L. Harrison. 2013. Seafood as local food: Food security and locally caught seafood on Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development 3 (3): 13–30.

Loring, Philip A., David V. Fazzino, Melinda Agapito, Ratana Chuenpagdee, Glenna Gannon, and Moenieba Isaacs. 2019. Fish and food security in small-scale fisheries. In Transdisciplinarity for Small-Scale Fisheries Governance, 55–73. Springer.

Love, David Clifford, Patricia Pinto, Julia da Silva, Jillian Parry Olson, and Fry, and Patricia Mary Clay. 2017. Fisheries, food, and health in the USA: The importance of aligning fisheries and health policies. Agriculture & Food Security 6 (1): 1–15.

Lowitt, Kristen. 2013. Examining fisheries contributions to community food security: Findings from a household seafood consumption survey on the west coast of Newfoundland. Journal of Hunger & environmental nutrition 8 (2): 221–241.

Lowitt, Kristen, Charles Z. Levkoe, Andrew Spring, Colleen Turlo, Patricia L. Williams, Sheila Bird, Chief Dean Sayers, and Melaine Simba. 2020a. Empowering small-scale, community-based fisheries through a food systems framework. Marine Policy 120: 104150.

Lowitt, K., C.Z. Levkoe, and C. Nelson. 2020b. Where are the fish? Using a “fish as food” framework to explore the Thunder Bay area fisheries. Northern Review 49: 39–65.

Morgan, David L. 1997. Planning and research design for focus groups. Focus groups as qualitative research 16 (10.4135): 9781412984287.

Nayak, Prateep K., Luiz E. Oliveira, and Fikret Berkes. 2014. Resource degradation, marginalization, and poverty in small-scale fisheries: Threats to social-ecological resilience in India and Brazil. Ecology and Society 19 (2).

Naylor, Rosamond L., U. Avinash Kishore, Rashid Sumaila, Ibrahim Issifu, Blaire P. Hunter, Ben Belton, Simon R. Bush, et al. 2021. Blue food demand across geographic and temporal scales. Nature communications 12 (1): 1–14.

Ndille, Roland, and Johannes A. Belle. 2014. Managing the Limbe floods: Considerations for disaster risk reduction in Cameroon. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science 5 (2): 147–156.

Njock, Jean-Calvin, and Lena Westlund. 2010. Migration, resource management and global change: Experiences from fishing communities in West and Central Africa. Marine Policy 34 (4): 752–760.

Nyiawung, R.A., R.K. Ayilu, N.N. Suh, N.N. Ngwang, F. Varnie, and P.A. Loring. 2022. COVID-19 and small-scale fisheries in Africa: Impacts on livelihoods and the fish value chain in Cameroon and Liberia. Marine Policy 141: 105104.

Okafor-Yarwood, Ifesinachi. 2019. Illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, and the complexities of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) for countries in the Gulf of Guinea. Marine Policy 99: 414–422.

Okafor-Yarwood, Ifesinachi, Nelly I. Kadagi, Dyhia Belhabib, and Edward H. Allison. 2022. Survival of the richest, not the fittest: How attempts to improve governance impact African small-scale marine fisheries. Marine Policy 135: 104847.

Olson, Julia, Patricia M. Clay, Patricia Pinto, and da Silva. 2014. Putting the seafood in sustainable food systems. Marine Policy 43: 104–111.

O’neill, Elizabeth Drury, Beatrice Crona, Alice Joan G. Ferrer, Robert Pomeroy, and Narriman S. Jiddawi. 2018. Who benefits from seafood trade? A comparison of social and market structures in small-scale fisheries. Ecology and Society 23 (3).

Pomeroy, Robert, John Parks, Richard Pollnac, Tammy Campson, Emmanuel Genio, Cliff Marlessy, Elizabeth Holle, et al. 2007. Fish wars: Conflict and collaboration in fisheries management in Southeast Asia. Marine Policy 31 (6): 645–656.

Saavedra-Díaz, Lina M., Andrew A. Rosenberg, and Berta Martín-López. 2015. Social perceptions of Colombian small-scale marine fisheries conflicts: Insights for management. Marine Policy 56: 61–70.

Santafe-Troncoso, Verónica, and Philip A. Loring. 2021. Traditional food or biocultural threat? Concerns about the use of tilapia fish in indigenous cuisine in the Amazonia of Ecuador. People and Nature. 3 (4): 887–900. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10235.

Scholtens, Joeri. 2015. Limits to the governability of transboundary fisheries: Implications for small-scale fishers in northern Sri Lanka and beyond. In Interactive Governance for Small-Scale Fisheries, 515–536. Cham: Springer.

Scholtens, Joeri. 2016. The elusive quest for access and collective action: North Sri Lankan fishers’ thwarted struggles against a foreign trawler fleet. International Journal of the Commons 10 (2).

Scholtens, Joeri, and Maarten Bavinck. 2018. Transforming conflicts from the bottom-up? Reflections on civil society efforts to empower marginalized fishers in postwar Sri Lanka. Ecology and Society 23 (3).

Scott, C., and M. Medaugh. 2017. Axial coding. The international encyclopedia of communication research methods 10: 9781118901731.

Short, Rebecca E., Stefan Gelcich, David C. Little, Fiorenza Micheli, Edward H. Allison, Xavier Basurto, Ben Belton, et al. 2021. Harnessing the diversity of small-scale actors is key to the future of aquatic food systems. Nature Food 2 (9): 733–741.

Soma, Katrine, Benson Obwanga, and Charles Mbauni Kanyuguto. 2021. A new rural-urban fish food system was established in Kenya–Learning from best practices. Sustainability 13 (13): 7254.

Song, Andrew M., Jahn P. Johnsen, and Tiffany H. Morrison. 2018. Reconstructing governability: How fisheries are made governable. Fish and Fisheries 19 (2): 377–389.

Song, Andrew M., Joeri Scholtens, Kate Barclay, Simon R. Bush, Michael Fabinyi, Dedi S. Adhuri, and Milton Haughton. 2020. Collateral damage? Small-scale fisheries in the global fight against IUU fishing. Fish and Fisheries 21 (4): 831–843.

Stoll, Joshua S., Hannah L. Harrison, Emily De Sousa, Debra Callaway, Melissa Collier, Kelly Harrell, Buck Jones, et al. 2021. Alternative seafood networks during COVID-19: Implications for resilience and sustainability. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems: 97.

Stacey, Natasha, Emily Gibson, Neil R. Loneragan, Carol Warren, Budy Wiryawan, Dedi Adhuri, and Ria Fitriana. 2019. Enhancing coastal livelihoods in Indonesia: An evaluation of recent initiatives on gender, women and sustainable livelihoods in small-scale fisheries. Maritime Studies 18 (3): 359–371.

Teh, Lydia C.L., and Daniel Pauly. 2018. Who brings in the fish? The relative contribution of small-scale and industrial fisheries to food security in Southeast Asia. Frontiers in Marine Science 5: 44.

Tezzo, Xavier, Simon R. Bush, Peter Oosterveer, and Ben Belton. 2021. Food system perspective on fisheries and aquaculture development in Asia. Agriculture and Human Values 38 (1): 73–90.

The New Humanitarian. 2022. Fishermen buying fish. https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/fr/node/241740

Tilley, Alexander, Kimberley J. Hunnam, David J. Mills, Dirk J. Steenbergen, Hugh Govan, Enrique Alonso-Poblacion, Matthew Roscher, et al. 2019. Evaluating the fit of co-management for small-scale fisheries governance in Timor-Leste. Frontiers in Marine Science 6: 392.

Trimble, Micaela, and Fikret Berkes. 2015. Towards adaptive co-management of small-scale fisheries in Uruguay and Brazil: Lessons from using Ostrom’s design principles. Maritime Studies 14 (1): 1–20.

Weeratunge, Nireka, Christophe Béné, Rapti Siriwardane, Anthony Charles, Derek Johnson, Edward H. Allison, Prateep K. Nayak, and Marie-Caroline Badjeck. 2014. Small-scale fisheries through the wellbeing lens. Fish and Fisheries 15 (2): 255–279.

World Population Review. 2022. Population of cities in Cameroon (2022). https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/cities/cameroon

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the guest editor of the special issue, Dr. Charles Levkoe from Lakehead University, for their critical comments, which helped shape the arguments in the paper. We would like to acknowledge the fish harvesters and fishmongers who offered their time and permitted us to gather and share their stories. Special thanks go to Alliance for Sustainable Development (ASDEV), NGO, for coordinating and assisting in the data collection process. We also acknowledge Marie Puddister for doing the map.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the Arrell Food Institute at the University of Guelph and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RAN and PAL designed the research, RAN organized data collection, and RAN, NB, and PAL conducted the analysis and writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Nyiawung, R.A., Bennett, N.J. & Loring, P.A. Understanding change, complexities, and governability challenges in small-scale fisheries: a case study of Limbe, Cameroon, Central Africa. Maritime Studies 22, 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-023-00296-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40152-023-00296-3