Abstract

A large multidisciplinary literature discusses the relationship between economic growth and population health. The idea that economic growth is good for societies has inspired extensive academic debate, but conclusions have been mixed. To help shed light on the subject, this paper focuses on opportunities for consensus in this large literature. Much scholarship finds that the health-growth relationship varies according to (1) which aspect of “health” is under consideration, (2) shape (e.g., positive linear or logarithmic), (3) issues of timing (e.g., growth over the short or long term), (4) a focus on health inequalities as opposed to population averages, and (5) multivariable relationships with additional factors. After reflecting upon these findings, I propose that economic growth promotes health in some respects, for some countries, and in conjunction with other life-supporting priorities, but does not by itself improve population health generally speaking. I then argue there is already wide, interdisciplinary consensus to support this stance. Moreover, policies focusing exclusively on economic growth threaten harm to both population health and growth, which is to say that political dynamics are also implicated. Yet multivariable approaches can help clarify the bigger picture of how growth relates to health. For moving this literature forward, the best opportunities may involve the simultaneous analysis of multiple factors. The recognition of consensus around these issues would be welcome, and timely.

Résumé

De nombreux travaux multidisciplinaires s’intéressent aux liens qui existent entre la croissance économique et la santé de la population. L’idée que la croissance économique est bénéfique pour les sociétés suscite de longs débats universitaires aux conclusions parfois mitigées. Afin de mieux comprendre ce sujet, cet article vise à dégager des possibilités de consensus au sein de cette littérature abondante. La plupart des études montrent que le rapport entre la santé et la croissance économique varie en fonction : 1) de l’aspect de la santé étudié; 2) de la forme (linéaire positive ou logarithmique par ex.); 3) de la temporalité (croissance à court ou à long terme par ex.); 4) de l’accent mis sur les inégalités en matière de santé plutôt que sur les moyennes de population; et 5) des relations à variables multiples avec facteurs additionnels. Après avoir considéré ces différentes conclusions, il est possible d’affirmer qu’à certains égards, la croissance économique a un effet bénéfique sur la santé, pour certains pays et en parallèle avec d’autres priorités vitales, mais qu’en elle-même, elle n’améliore globalement pas la santé de la population. L’article montre ensuite qu’il existe déjà un large consensus interdisciplinaire appuyant ce point de vue. En outre, les politiques axées exclusivement sur la croissance économique risquent de nuire non seulement à la santé de la population, mais également à la croissance économique elle-même, ce qui signifie que des dynamiques politiques sont également à l’œuvre. Toutefois, des approches à variables multiples peuvent contribuer à expliquer de façon plus large la façon dont la croissance économique exerce un rôle sur la santé. Pour faire évoluer cette littérature, il pourrait être judicieux de procéder à une analyse simultanée des différents facteurs. La reconnaissance d’un consensus sur ces questions seront également profitable et opportune.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The relationship between economic growth and population health has long been debated. An interdisciplinary literature makes contrasting claims about whether growth improves or harms health, the directionality of the relationship, to whom in particular these effects apply and under what circumstances. This poses important dilemmas for the social sciences, such that comparative studies have often focused on other phenomena. Consider for instance how little attention economic growth drew compared to fertility rates in demographic studies over the latter part of the twentieth century, even under the long shadow of Thomas Malthus’s work (Pebley, 1998). Numerous challenges unique to the present era (e.g., see Haass, 2022) are intertwined with economic considerations. Clear direction on how to regard opportunities for growth would be helpful, and alignment around some kind of consensus timely.

In this paper, I review the case for interpreting economic growth as a determinant of population health. To set the stage for discussion, the next section explores the simpler question of whether growth is good for health. Because answering such a question is more complex than it may appear at first blush, I then propose a framework for organizing the findings of this large literature in all their variety. Presented as a set of straightforward questions about how researchers operationalize their studies, the framework illustrates a multifaceted impact of growth on health. After describing the literature review methodology in the following section, this then becomes the framework that I use to summarize a fresh literature search of those findings. Finally, in a discussion of some key takeaways, the crux of this work is an attempt to identify what the best opportunity for interdisciplinary consensus might be. Here, I argue that economic growth likely benefits population health in some respects, for some countries, and in conjunction with other life-supporting policy priorities, but does not otherwise on its own promote health as a general rule. While still offering a falsifiable claim about how growth relates to health, I show how this conclusion harmonizes some of the disagreement in this literature. I also show how support for growth-minded initiatives must be tempered by several caveats. Not the least of these is that they can easily harm health. While giving an honest appreciation for how growth could benefit health, and presumably has in the past, taking a more realistic stance such as this one may help encourage the kinds of policies that will more convincingly improve both health and prosperity. In offering these contributions, I suggest we may be much closer to consensus than many realize.

2 Does Economic Growth Improve Population Health?

Several decades ago, Joseph Schumpeter (1947) acknowledged the challenges of studying economic change. First is the wide array of considerations that have bearing on a country’s prospects for growth. Among them are geographic factors, various types of regulation and the institutions that devise them, politics, “innovation” in the broadest sense, human “material” such as educational attainment, and cultural phenomena. Yet these factors do not promote growth in isolation from each other. Still another challenge is placing them into a coherent framework that reflects which are most important. At the macro-level, Schumpeter says, “we have to deal with a system of interdependent factors of which economic growth is just one” (p. 4). His observations were prescient, since subsequent debates over economic growth have left no shortage of countervailing theories and findings.

Conversations around how economic growth may benefit health have been similarly conflicted. Some optimism comes from Thomas McKeown (1976), who galvanized support for the view that economic growth improves population health. He argues that rising standards of living were responsible for Western society’s long-term gains in life expectancy. In addition to curbing hunger-related death, better access to good food in wealthier economies improves strength and immunity. To support this explanation, Fogel (1997, 2004) discusses how food availability and sanitation were key contributors to population health improvements in the twentieth century. According to Birchenall (2007), economic growth explains between a third and a half of recent declines in mortality. While the exact linkages to health have been disputed, McKeown’s central argument that growth benefits health has had lasting influence (Colgrove, 2002).

The “McKeown thesis” has been critiqued by many, however, who consider programs for growth to be at odds with population health. Szreter (1988, 1994, 2002, 2004) for example claims that McKeown’s exclusive focus on rising standards of living became a pretext for subsequent waves of economic liberalism, undermining population health as a policy priority. He argues that once economic growth was understood as promoting health, policymakers took it to be an intrinsic social good, the attainment of which would inevitably lead to better population health. Yet such views discouraged investment in public health infrastructure. He further contends that the preferred models for protecting and promoting health began to emphasize individual-level risk factors like smoking or sedentary lifestyles, an approach which likely has had little impact on population health (Rose, 1985; Schwartz & Diez-Roux, 2001; Galea et al., 2010; Davidson, 2019). Szreter criticizes McKeown for having taken for granted the egalitarian welfare structures of Western countries of the time, as well as for overlooking the kinds of illnesses that can be prevented through investment in public health and sanitation systems.

Another view is that population health is good for the economy. Many economic scholars highlight the role of “human capital,” in that growth depends on a capable, healthy workforce (Mankiw et al., 1992; Mankiw, 1995). Economists now recognize the importance of investment in both population health and educational systems for growth, not the least because these support the productivity of workers (e.g., Berg & Ostry, 2017; Ogundaria & Awokuseb, 2018; Psacharopoulos, 2006; Dhrifi et al., 2021) by reducing absences and enhancing job performance (Bloom & Canning, 2000, 2003; Bloom et al., 2004).

That being the case, numerous scholars concede that the relationship between economic growth and population health is better understood as bidirectional (Bishai & Kung, 2007; Swift, 2011; French, 2012; Bloom & Canning, 2003), in keeping with Schumpeter’s own speculations in 1947. The idea here is that economic growth is good for population health but the vice-versa is also true. Along these lines, Ranis and colleagues (Ranis et al., 2000) discuss ‘virtuous and vicious cycles’ between growth and health. They argue that policies ignoring the latter often lead to a vicious cycle and thus decline in both growth and health.

Disagreement continues to be a feature of this large literature. However, I suggest much of that disagreement comes from relatively simple questions of specification, which alter the kinds of relationships that may be expected to appear. That being so, interdisciplinary consensus becomes clearer when answers to these questions are accounted for.

3 A Framework for Review

Needed is a common framework for organizing these diverse findings. I propose a framework that comprises some basic questions about the choices scholars make in day-to-day research. The starting point is (1) the choice of health outcomes to study. Surely, there are different ways to conceptualize health (e.g., survivability, absence of particular disease, mental health) but the ways they relate to economic growth and prosperity vary quite a bit. Another issue pertains to (2) differences in the shape of the relationship. By this, I refer to the modeled, mathematical relationship between economic factors and population health, which often shows that growth has different implications for countries at different stages of economic development. The next set of questions involves (3) issues of timing, such as the span of years under consideration or the pace of growth across that time frame. In contrast with studies focused on average health, many studies of health inequalities compare countries by (4) the degree to which health varies at the subnational level, such as the gap in life expectancy across households or across cities. Here greater disparity is usually seen as more problematic. Last but not least are questions of (5) what happens when additional variables come into play. The point here is that economic growth may not stand on its own as a determinant of good health, but is best understood as part of a bigger picture. Although not always discussed explicitly, scholars agree that these distinctions matter a great deal. As I show throughout the rest of the paper, growth appears to benefit health only under certain specifications, while others suggest it can be harmful.

4 Review Methodology

This paper is designed as an approachable way to discuss a complex subject. Through a critical narrative essay, the objective was to explore areas of agreement in the scholarly literature. Given the size and diversity of this literature, an unstructured review was the preferred option. As part of this work I carried out a fresh literature search. To capture as many potentially relevant studies as possible, terms were entered into Web of Science through May 2022. Peer-reviewed articles were retrieved that referred to the topics {“economic growth” or “economic development” or “economic prosperity” or “gross domestic product” or “GDP” or “national income” or “GNI” or “industrialization” or “human development”} AND the topics {“population health” or “public health” or “life expectancy” or “infant mortality” or “maternal mortality” or “morbidity” or “disease” or “incidence” or “child mortality” or “Under 5 Mortality”). This yielded over 12,000 abstracts. To help pare down that number, further consideration was given to quantitative comparative analyses of 10 or more countries, which sought nomothetic claims about the impact of economic growth on health. To support a manageable but comprehensive review, some exceptions to this rule were applied on a case-by-case basis. Where there was clearly wide agreement, more recent studies were assumed to represent earlier ones, such as in studies connecting pollution to poor health, or higher cancer incidence to higher scores on the Human Development Index. For precedent and context, as well as to curtail methodological bias, some theoretical and qualitative-historical pieces were considered also. Additional authors were cited who contributed significantly to the legacy of this literature, such as Samuel Preston or Thomas McKeown, along with studies responding to their findings that appeared in the search. For more detail on the search methodology, refer to the Supplementarymaterial available online.

This search strategy produced 600 potentially relevant studies, which were downloaded for further review. Of these, a majority (n = 498) somehow touched upon the relationship between economic growth and population health. Most (n = 358) of those in turn used empirical analysis to see whether growth impacts health. They showed remarkable heterogeneity in terms of their areas of focus, conceptualizations for health, methodology, and findings, which were assessed in light of the proposed framework. In the analysis below, special attention was given to studies of life expectancy and other general measures of survivability. This is not only due to their general relevance to health, but also the fact that some of the most contested and controversial claims pertain to them.

I interpret “economic growth” as referring to change in a country’s income per capita over time. However, this change can be measured in numerous ways, which may affect interpretation. Most studies focus on gross domestic product (GDP) per capita or similar measures of economic prosperity in standardized dollars. Other approaches account for purchasing power parity (PPP) based on a common “basket of goods” benchmark. Although more challenging to calculate, the latter are arguably higher-quality measures where available. Given what were known to be high correlations among these, however, I did not have a priori reason to believe that this distinction would supersede those emphasized in the above framework. Most studies also use cross-sectional differences in income and presume that they represent differences in long-term economic development. By contrast, some specifically measure change in income per capita over time. This choice too requires arbitrary decisions, especially when dealing with time-series data. As Table 1 shows, each approach has both advantages and disadvantages, which posed some complications. Restricting analysis to studies based on the latter alternative measures would have invited other risks as well, after excluding findings from a very large and relevant comparative literature based on the more standard comparisons. The paper therefore emphasizes substantive conclusions coming from this literature, while seeing the use of higher-quality measurement as an asset.

With the kind of flexible, unstructured approach described above, the potential for bias is always a risk and this review is no exception. Caution is encouraged when interpreting the analysis I offer below. Bearing these limitations in mind, however, a fresh literature search still supports using the above framework to describe the enormous diversity of findings in this large literature. In the following, I use it to categorize studies, as well as to find consensus amidst this diversity.

5 Empirical Dimensions

This section uses the above framework to discuss findings from the empirical literature. It shows how the ways we operationalize studies will affect what we end up finding out, while demonstrating the multifaceted character of the relationship between growth and health. For an overview of select health outcomes, findings, and remarks around the status of this literature, see Table 2.

5.1 Operational definitions of health

To start, whether economic growth is potentially good for health depends on how “health” is defined. Consideration of all the different aspects of health that could be studied—from mortality overall to different kinds of disease such as parasitic or chronic disease, obesity, sedentariness, mental health, etc.—shows how health is a multifaceted concept that has a variegated relationship to the economy.

Much research supporting a positive impact of economic growth focuses on life expectancy or overall mortality. Admittedly most such studies do not critically review this relationship. They typically control for economic factors while mainly interested in other variables and wishing to rule out sources of confounding. However, numerous studies do consider this relationship more carefully and conclude in favor of growth, for example, highly affirming results from Jetter et al. (2019) or Cole (2019). Still more affirming findings are from studies of life expectancy in sub-Saharan Africa (Shahbaz et al., 2019; Frimpong & Adu, 2014), which is often a focus of the developmental literature. Others suggest that growth contributes to better subjective well-being (Deaton, 2008) and higher consumption of fruits and vegetables (Frank, 2019). Equivalently, economic growth reduces risk of several negative outcomes as well. Examples are infant and child mortality (O’Hare et al., 2013), childhood undernutrition (Smith & Haddad, 2002; Yaya et al., 2020), and risk of a wide range of diseases, including tuberculosis (Janssens, & Rieder, 2008), cholera (Talavera, & Pérez, 2009), malaria (Datta & Reimer, 2013), HIV infection (Nikolopoulos et al., 2015), and mortality from several other diseases both infectious and non-infectious (Bollyky et al., 2015). In fairness, there are also some dissenting conclusions (e.g., Chen et al., 2014; Vollmer et al., 2014), including some that consider more complex relationships as in Vogel et al. (2021). I discuss these more below. Nevertheless, there are some respects in which a clear majority of studies link better health to improvements in economic prosperity.

On the other hand, economic growth comes with risk of diverse health problems as well. Several recent analyses show that cancer incidence is higher in wealthier countries (Coccia, 2013; Luzzati et al., 2018; Grant, 2014; Teoh et al., 2020; Dafni et al., 2019), so is incidence of atopic dermatitis (eczema) (Alkotob, 2020; Laughter, 2021), multiple sclerosis (Buchter et al., 2012), inflammatory bowel syndrome (Michaelides et al., 2020; Szilagyi et al., 2021), and many others. Broadly speaking, a country’s disease profile changes as it grows economically, with a presumable tendency toward noncommunicable disease but also greater diversity of diseases in wealthier countries (Garas, 2021). Additional studies connect economic prosperity to the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, both in terms of death rates and incidence (Antonietti et al., 2021; Chang et al., 2022; Hashim et al., 2020; Djordjevic et al., 2021; Sorci et al., 2020). This likely has to do with a higher degree of social interaction coming from commerce in these countries, including connectivity to the global marketplace (Farzanegan et al., 2021). There are also some environmental implications, which I touch upon below. Altogether, interdisciplinary findings are that economic growth reduces risk of some health outcomes while increasing risk of others.

5.2 The Shape of the Relationship Between Economic Growth and Health

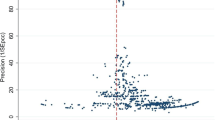

The second question pertains to the shape of the relationship, e.g., whether it is linear or if it changes across the range of values. Rather than economic growth simply promoting population health or not, the idea here is that the relationship may take a variety of forms. These forms in turn are contingent on how health is conceptualized and measured. Examples are presented in Fig. 1. A key conclusion is that growth may have different implications for countries at different stages of development, depending on the health outcome under consideration.

Simulated scatterplots of possible relationships between income per capita (on the X-axis) and health outcomes (on the Y-axis) with the fitted regression line. a A positive linear relationship. This is the standard formulation of a health outcome (e.g., self-rated health or subjective well-being) improving by some amount with each increase in income per capita. b A negative linear relationship. This is the standard formulation of a health outcome being less likely with each increase in income per capita. c A logarithmic relationship. A well-documented example is the diminishing returns to life expectancy as income per capita increases, appearing more beneficial for poor countries. d A Kuznets curve (quadratic with downward concavity), such as with injury mortality

Linearity is the statistical assumption that a straight line can be drawn through a scatterplot to depict the relationship between variables (see panel [a] of Fig. 1). Each unit increase in one variable would then correspond with a specific amount of increase or decrease in the other. Linear relationships are frequent in this literature, partly because it is a common assumption in statistical exercises. Studies find, for example, a positive linear relationship between per-capita GDP and life satisfaction (Sacks et al., 2012). By the same token, a negative linear relationship may appear when examining poor health outcomes instead (panel [b] of Fig. 1). For example, cancers of the mouth and pharynx are higher in less developed countries (Mathers et al., 2002), so these trends are downward with increasing income per capita. Again, the impact depends on the health outcomes under consideration. Relationships with incidence rates for many other cancer types are positively linear (Luzzati et al., 2018).

By contrast, much research concludes that health relates logarithmically to economic growth or prosperity (see panel [c] of Fig. 1). This means that the potential benefits to health weaken as countries develop economically. Findings of loglinear relationships follow the seminal work of Samuel Preston (1975). Using simple scatterplots, he shows a very steep relationship between income per capita and life expectancy among the poorest countries. However, the relationship flattens among wealthier countries such that any further contributions of economic growth would seem to be negligible. Similar may be said of some mortality-based measures like infant mortality, which is much lower in wealthier countries and so is often measured in logarithmic scale (e.g., Schell et al., 2007).

Relationships between economic growth and population health are not, however, limited to linear or logarithmic trends. Other kinds of relationships make it difficult to say whether economic growth helps or harms population health at all. A quadratic, “Kuznets” type of curve in the shape of an inverted “U” (see panel [d] of Fig. 1) describes relationships with injury mortality (Bishai et al., 2005; van Beeck et al., 2000; Ahmed & Andersson, 2000) for example. Gains in per-capita GDP involve more motor vehicle deaths in less developed countries, but the relationship peaks and then turns negative at higher income levels. The argument here would be that economic growth facilitates access to personal vehicles and other potentially dangerous commodities, but controls such as smarter regulation and safer technology start to kick in only after a certain level of economic advancement. The case for a Kuznets-type curve has been made with respect to numerous other health outcomes as well, in which middle-income countries have the highest risk. Examples are cholesterol levels (Ezzati et al., 2005), obesity (Grecu, & Rotthoff, 2015), systolic blood pressure (Nagano et al., 2020), cardiovascular disease mortality (Spiteri & von Brockdorff, 2019), alcohol consumption (Cantarero-Prieto et al., 2019), and self-reported asthma (Sembajwe, 2010).

For some outcomes, issues of shape are an area of active debate. Violation of the linearity assumption fuels the argument that economic growth matters little to the health and well-being of countries that are already wealthy (Wilkinson & Pickett, 2010; see also Bloom & Canning, 2007). However, this is subject to interpretation. Deaton (2013, pp. 30-34) demonstrates how the relationship with life expectancy appears positively linear after performing a logarithmic transformation on GDP per capita. The argument here is that one more dollar per capita in a poor country, where most households live off of $1000 per annum, will mean a lot more than a dollar in a wealthy country where they live off of $100,000. A logarithmic transformation accounts for this difference in scale. Nevertheless, as I discuss below the practical implications of this kind of rebuttal are debatable if it says little about how growth is invested.

5.3 The Time Dimension

Issues of time are another consideration. Findings are different when considering growth over the long or short term, whether it is fast or slow, and when using model specifications that allow population health to evolve over a period of time after economic change has occurred (“lag effects”). In fact, many studies link short-term improvements in economic prosperity to worse health. The observation of detrimental impacts during times of short-term growth is a classic sociological insight (Durkheim, 1897/2006). Ruhm (2000, 2003, 2007) similarly observes more obesity, smoking, and heavy drinking when labor markets strengthen. One possible explanation is that longer working hours mean greater stress for workers and self-medication through unhealthy habits. Along these same lines, studies suggest that population health improves in tandem with economic crisis (Tapia Granados, 2005; Tapia Granados & Ionides, 2017), for instance, by observing increases in life expectancy (Kristjuhan & Taidre, 2012) and children’s self-rated health (Angelini & Mierau, 2014) in the aftermath of a recession, as well as lower rates of tuberculosis (Holland et al., 2011) and mortality (Rolden et al., 2014; Ballester et al., 2019; Gerdtham & Ruhm, 2006).

On the other hand, economic crisis may not benefit health on every occasion, in every respect. Dadgar and Norström (2020) do not find any short-term impact on cardiovascular mortality. Some studies link economic shocks to higher rates of child mortality and child wasting in poor countries (Maruthappu, 2017; Baird et al., 2011; Headey & Ruel, 2022). Thus, the impact of growth again varies when considering alternative conceptualizations for health and when comparing countries at different levels of economic development.

Other studies suggest that economic growth improves population health over the long run (e.g., Swift, 2011; Jetter et al., 2019; Cole, 2019; Firebaugh & Beck, 1994; Brenner, 2005). The argument here is that growth implies sets of opportunities that may take some time to realize themselves, thus there could be a substantial lag between changes in economic fortunes and any improvements in population health. Arguably, thoughtful policies are needed in the context of economic expansion (Szreter, 2004; Haddad et al., 2003). Urbanization for example should come with infrastructures for waste disposal and water treatment to curtail risk. Industrial innovation too should come with new safety features and protocols to avoid harming workers. The time it took to put such infrastructure in place may explain why people’s physical stature stagnated or even worsened in Canada, England, and the USA during the nineteenth century, but improved later on (Steckel, 1995; Cranfield & Inwood, 2007; Haines, 2004; Shaw-Taylor, 2020). However, the same case of a lagged effect can be made with regard to negative health outcomes. Cancer rates for example are not immediately sensitive to policy change, simply because it can take many years for toxic exposure to result in new cancer cases.

Another related issue is the pace of growth. Some scholars suspect that quicker growth is more detrimental to health than slower, steady growth. Psychosocial kinds of explanations could be applied here, as in Durkheim (1897/2006) or Ruhm (2000, 2003, 2007). Yet Szreter (1999; 2004) argues that shortsighted policy is to blame. In a historical analysis comparing nineteenth century Britain to China in the twentieth century, he discusses how in both cases a laissez-faire policy orientation trumped other important priorities like population health. Supporting those concerns, various authors have linked the accelerated processes of industrialization in China to outbreaks of cancer (Bode et al., 2016), where factories have evidently used public waterways to dispose of toxic waste (Zhang et al., 2010; Li et al., 2016).

There is a shortage of cross-national research specifically on the pace of growth, as this research typically focuses on one or a few countries at a time. However, choices over policy seem to be a common thread. A pair of papers (Hertzman & Siddiqi, 2000; Siddiqi & Hertzman, 2001) examines the history of rapid growth in the “tiger economies” of Asia. After exceptional growth during the past few decades, these countries saw remarkable gains in life expectancy. The authors contend that these changes were the result of policies supporting access to education and housing, which also coincided with reductions in income inequality.

5.4 Health Inequalities

Some studies focus on health inequalities, or variation in health within societies, where larger disparities are usually seen as harmful. Often but not always, these are discussed within the context of other kinds of social inequality. This is to say there are multiple ways to measure health inequality, so decisions around the operational definition thereof are an important step. The level of variation in health can then be compared across countries, offering another fruitful area for debate.

Yaya et al. (2020) for example find that economic growth at the national level fails to prevent stunting among the poorest children. However, at least two other studies could not confirm any relationship between economic growth and health inequalities (Yang, & Geng, 2022; Eozenou et al., 2021). Still other papers make counterintuitive arguments by suggesting that the dissemination of knowledge and other resources increases health inequalities, by way of disproportionately reaching the more privileged members of society (Cutler et al., 2006; Link & Phelan, 2010). Considering the importance of this subject for many (see Beckfield et al., 2013), more research is needed on comparative differences in subnational variation in health.

5.5 Multivariable Relationships

As illustrated above, most scholars agree that economic growth does matter for population health, but exactly how it matters is an ongoing question. What then happens when more factors are considered? This last step highlights the need to include additional variables in everyday analysis, beyond simply adding to the list of controls. I next argue that multivariable analysis provides a more complete picture of how economic growth relates to health.

Figure 2 presents some of the most common types of multivariable relationships considered in the scholarly literature. By far the one tested most often is spuriousness, although it is certainly not the only possibility. For clarity, I include in this figure some description of the methodology based on familiar recommendations from Baron and Kenny (1986), although note that multivariable techniques have evolved since then (see Hayes, 2009).

The first possibility is that there is a mediating (or “intervening”) relationship. This refers to questions of whether a third variable might account for any association between economic growth and population health. Consider, for instance, evidence that growth in per-capita income promotes life expectancy (Anand & Ravallion, 1993) and infant health (Patterson, 2017), but only insofar as it means that the government spends more on public health programs. Such findings show that the policies in place are what really matter, particularly in terms of how societies use economic growth to improve the lives of citizens. Put another way, mediation analysis can explore whether economic growth is a worthwhile end on its own right (a “sufficient cause” of good health), or whether it is best understood as a means to an end and thus part of a broader strategy to improve the well-being of citizens. However, it is important to note that the data alone cannot distinguish between mediators and confounders. Careful theoretical argumentation is needed to characterize a variable as both a cause and a consequence of other phenomena (“Z” in Fig. 2).

Moderation, or interaction, is another kind of multivariable relationship. Studies of moderation examine what factors may affect the relationship between economic growth and population health. For Latin American countries, Biggs et al. (2010) find that income inequality reduces or even eliminates the positive influence of economic growth on health. Complementarily, Kangas (2002) finds that income inequality undermines the potential for economic growth to improve the income levels of poor people. In his words, when presuming income inequality to be the cost of doing business, the benefits of growth do not “trickle down.”

Indeed, much literature suggests the effects of income inequality are pervasive. According to Wilkinson and Pickett (2006, 2010; Pickett & Wilkinson, 2015), unequal societies are more competitive, less trusting, less cooperative, and altogether more stressful to live in, which activates psychosomatic processes that harm health. Yet income inequality seems to impede growth over the long term as well (Mo, 2000; Keefer & Knack, 2002; Berg & Ostry, 2017). This is partly because a combination of poorer health, disincentives, and political instability make unequal countries less reliable places for investment. Taken together income inequality appears to harm health directly, mitigate the economic growth/population health association, and pose obstacles to economic growth. Programs for growth will evidently be self-defeating over the long run if they end up increasing income inequality.

While these arguments are well established in the literature, my own search did not show clear consensus on the subject. According to one recent review of the empirical literature (Ferreira et al., 2022) conclusions on the influence that income inequality has on both growth and health are actually quite mixed. The authors speculate that the discrepancies in findings may come from differences in data and methodological choices. Other studies show income inequality harms health in poor countries but not rich countries (Curran & Mahutga, 2018; Herzer & Nunnenkamp, 2015), which contrasts with common claims that income inequality poses more concern for the latter countries.

A related literature asks how environmental degradation fits into this picture. Steinberger and colleagues (2021) show how cross-national differences in life expectancy may be the consequence of multivariable relationships between carbon emissions, energy consumption, and economic growth. Following up with tests of moderation, another paper (Vogel et al., 2021) concludes that both economic growth and resource extraction weaken the efficiency with which energy consumption can support basic human needs including health. Key questions on the role of governments thus come to the fore in multivariable analysis. A paper from Haddad et al. (2003) is a case in point. They argue that the plight to reduce child malnutrition requires an approach that balances programs for growth against other strategies and priorities that more directly address the needs of children.

In summary, the most important debates may be those that consider multiple factors. Nonetheless, concerted studies of multivariable relationships, which start at the theoretical level and then follow through with original analysis of the types of relationships discussed here, are infrequent. Interest in multivariable relationships tends to be limited to the choice of control variables. This is a problem even for the most optimistic accounts, which do not often tie their empirical analysis back to questions of why economic growth might be good for health and for whom. Filling these gaps may be our most important opportunity ongoing.

6 Key Takeaways and Implications

There is a compelling case for the claim that economic growth plays some kind of role in improving population health, which I review in the next few pages. However, it seems that the more we broaden the scope of the literature under consideration, the more caveats come along to constrain this view and the case for a simple, causal pathway from the former to the latter is vanishingly small. As illustrated above, the impact of growth varies by health outcome, considerations of timing, and a country’s developmental progress—the “shape” of the relationship as discussed above. Indeed, there are some respects in which growth appears to harm health. Additional opportunities come from an interest in health inequalities and in more complex relationships across multiple variables. These considerations bring us into a larger, richer arena for empirical study. They also call into question the wisdom of viewing growth as an intrinsic social good, rather than one that works interdependently with other social goods to promote human welfare.

6.1 Does Economic Growth Enhance Population Health?

In response to this question, the best answer may be a qualified yes: in some respects, for some countries, and in conjunction with other life-supporting priorities. The consensus here is often quite striking, with important caveats appearing on the one hand in the some of the most optimistic views such as Cole’s (2019) mention of “diminishing returns” to survivability in wealthier countries. On the other hand, even some of the more pessimistic readings leave open possibilities for long-term benefit, such as historical analysis from Szreter (1999; 2004), which emphasizes policy gaps during times of economic change. Ruhm (2003), who was seminal for research on the detrimental impacts over the short term, too acknowledges that economic change likely benefits health over the long term.

In his own review, Weil (2014) summarizes the situation well: “It is hard to escape the conclusion that in the long run, improvements in health have indeed been the result of economic growth” (p. 678). Growth, he explains, facilitates scientific discoveries, advances in medicine, and public health initiatives. Moreover, claims of a bidirectional relationship between economic growth and population health still support the possibility that economic growth enhances health by being part of a “virtuous cycle” of increasing prosperity (Ranis et al., 2000). Rising income levels are therefore among the likely explanations for cross-national variation in mortality-based indicators like life expectancy and infant mortality over a large sample of countries—developed and developing countries combined (Pritchett and Summers, 1996; Filmer and Pritchett, 1999; Bollyky et al., 2019). Researchers who routinely control for income per capita in comparative analysis do so for good reason, although more work is needed on the theoretical front to clarify what role it plays in a multivariable context (i.e., mediation/moderation, versus confounding).

Granted, not everyone agrees that growth benefits societies overall. Borowy (2013) points out how one faction of scholarship calls for radical restructuring of the global economy with goals of economic equity and environmental justice in mind. Often advocating for “post-growth” or “de-growth” agenda, some offer strategies for equitable welfare policy in the absence of economic growth (e.g., Walker et al., 2021). With replications of the Preston Curve, Lutz and Kebede (2018) argue that coincident changes in educational infrastructure are what really explain long-term historical trends, making growth a spurious cause of comparative differences in population heath. After using Granger tests of causality, another paper (Chen et al., 2014) finds that claims of a causal pathway leading from wealth at the national level to improved population health could only apply to a small minority of developing countries.

Nevertheless, by allowing that growth improves health only in some respects and for some countries, the stance that I propose above harmonizes many of these divergent claims. Perhaps more so, it acts as a prompt to consider the bigger picture of a country’s policy regime. Note that other goals such as support for equity, education, environmental protection, and other amenities still find a place with the phrase, in conjunction with other life-supporting priorities. This is especially given large literatures connecting these, too, to health.

Discussion of the theoretical methodology is needed as well. The fixed-effects models that Lutz and Kebede (2018) use, for example, do not distinguish spurious from mediating relationships. If variables pertaining to education were to be interpreted as mediators, it would mean that growth implies better health by way of allowing more investment in educational infrastructure. That possibility must be ruled out to sustain the claim that growth has no bearing on health. Similar may be said of other mediators, such as the diffusion of health-related knowledge and technology throughout the world (see Cutler et al., 2006). Although these can be inexpensive to deliver (Casabonne & Kenny, 2012), citizens of wealthy countries may still be uniquely equipped to access them.

Perhaps the most compelling case for growth comes from empirical analyses conducted only recently. Compared to previous studies, Jetter et al. (2019) and Cole (2019) use larger samples of countries over a longer time span. Cole tests the impact of economic growth by measuring change in income over time, rather than inferring growth from contemporaneous measures of income per capita as most studies do, and finds a robust correlation with improvements in both life expectancy and infant health. Jetter et al. (2019) examine trends over a much longer time frame. They find that the positive impact on life expectancy strengthened in the past few decades and that economic prosperity explains as much as 64% of the variation thereof up to the present day. So, in terms of historical trends in mortality, the balance of evidence favors the beneficial effects of economic growth over the long term.

Yet one important piece of the puzzle is missing in these optimistic studies. They do not illuminate the pathway leading from growth to health through tests of mediation. What we have are reliable correlations between economic measures and health, which are robust to different model specifications and controls. However, we do not have a clear explanation for why growth should be good for health at the macro level, which withstands the same rigor of empirical testing. As a case in point, McKeown’s (1976) and then Fogel’s (1997; 2004) claim that growth promotes health by increasing access to food does not hold in at least one study of food supply per capita as a mediator (Patterson, 2017). Cole (2019) separately tests the influence of caloric intake per capita on health and finds that impact is somewhat weaker in comparison to economic growth.

Altogether, my literature search turned up relatively few studies that include careful tests of mediation, despite offering numerous explanations linking economic growth to better population health. Meanwhile, other studies highlight the health implications of amenities that come from economic policies, such as infrastructures for education, sanitation, etc. The insinuation from much of this literature that economic growth is an intrinsic good, which acts independently of other social goods or even supersedes them, therefore rings hollow. Yet, neither can growth be conclusively ruled as spurious when confusing potential mediators as confounders in multiple regression models.

Absent those debates, consensus would seem to be that growth is both good and bad for population health. This is consistent with long-standing demographic theory. The implication from Omran (1971) is that risk of chronic disease is the trade-off for living in a more developed country, where the chances of long life are better. However, questions remain as to whether economic change has in some respects created excess risk.

Related concerns pertain to the impact of economic activity on the environment. Global warming and other environmental threats have been the aftermath of industrialization. Much scholarship finds that growth therefore worsens environmental degradation. This area too has seen debate, with some scholars observing a Kuznets-type curve (an inverted “U” shape; e.g., Grossman & Krueger, 1995; Selden & Song, 1994; Shafik, 1994; Dinda, 2004). Typical explanations have been that more developed countries produce cleaner technologies, leading to the curious conclusion that the remedy for environmental degradation is more growth. Most studies fail to affirm that carbon emissions follow a Kuznets curve, however, according to a recent systematic review (Haberl et al., 2020), indicating that it only continues to increase monotonically alongside income. A more complete picture should come from understanding the interplay across multiple factors—economic growth, carbon footprint, politics, health, etc. So says a recent bibliographic study (Wiedenhofer et al., 2020), which finds that research on “decoupling” economic growth from carbon emissions in support of more sustainable alternatives has grown quickly in recent years.

6.2 Exploring the Bigger Picture

The last part of the framework invites scholars to explore the broader political and economic context. They can do so by bringing more variables into their analysis, in ways that seriously consider other kinds of arguments (see Fig. 2). Although it would seem to fall into a methodological realm, and I pitch it as such, a much bigger interdisciplinary debate looms large behind this recommendation. Cited above are papers arguing that the benefits of growth depend on whether it occurs in a context of socioeconomic inequality (Biggs et al., 2010), that growth improves survivability only to the extent that it encourages governments to invest in public health (Anand & Ravallion, 1993; Patterson, 2017), that it weakens the degree to which energy consumption and resource extraction drive improvements in health (Vogel et al., 2021), and that both education and health are prerequisites for growth (Berg & Ostry, 2017). Although they make the case for spuriousness in GDP, results from Lutz and Kebede (2018) could be interpreted to suggest that growth has historically supported population health by promoting investment in education (a mediator). Similar could be said about other skeptical studies that include potential mediators in regression models (e.g., Jamison et al., 2016; or Brady et al., 2007). Complementary arguments coming from scholarship on the ‘demographic dividend’ highlight the development of educational infrastructure as a pathway out of poverty traps (Bloom & Canning, 2001; Lutz et al., 2019; Prados de la Escosura, 2013). Finally, much of the discrepancy between good and bad impacts of growth likely has to do with how the world’s countries have industrialized. Growth has evidently come with an increasingly toxic ecosystem (Belpomme et al., 2007; Irigaray, 2007). Consequentially, empirical evidence (Luzzati et al., 2018; Coccia, 2013) points to higher cancer incidence in wealthier countries.

Part of the problem is that reductionism to economic growth is a unidimensional interpretation of prosperity. Variables like gross domestic product per capita fail to capture the manifold kinds of exchange that do not happen to revolve around cash, such as domestic labor, volunteerism, or political participation. Although probably a more valid measure of income, similar concerns apply to measures based on purchasing power parity. Neither do growth-focused measures address the quality of international relationships. This is bearing in mind an unsavory global history, in which Western powers occupied and exploited parts of the world that now comprise many of the poorest countries, such as in sub-Saharan Africa.

These observations put us quite far from the basic question of whether economic growth is good for “health” in broad strokes, by highlighting what is likely to be a more complex dynamic. They also show how a multivariable approach offers a powerful, theoretically forceful alternative. Yet to add variables to routine analysis, or even reconsider extant findings from multiple regression models, could be a relatively modest embellishment. Among both proponents of growth and its critics, multivariable analysis may be the most important opportunity.

6.3 “...In Conjunction with Other Life-Supporting Priorities”

Raising these stakes are debates around economic philosophy. Should we support policies that prioritize growth, assuming that it is an intrinsic social good from which other goods (including health) flow, according one tradition? Economic liberalism, known by various other, often pejorative names (“supply-side” economics, neoliberalism, laissez-faire minimalism, “trickle-down” economics) offers a familiar package of solutions: deregulation, tax cuts, diminution of publicly funded services, privatization thereof, etc. Or should we support the main contenders, which have their own theoretical legacies? These alternative economic philosophies ask for all the opposite: more generous welfare benefits, government-sponsored public services, oversight of economic activity, etc.

Although surely much debate remains to be had, the latter philosophy carries more weight for health researchers. A majority support some kind of equitable solution for the use of growth, either through the mitigation of market inequities or via government sponsorship of infrastructures that support “human capital” such as through investment in education. Remarkably, many more economists nowadays also support this latter philosophy than in times past (see Krugman, 2009). Advocacy for government involvement in economic affairs has a robust theoretical base, such as in John Maynard Keynes, or in Amartya Sen’s Capabilities Approach (1985). Numerous other, complementary approaches have come to the fore as well in recent past (see Brand-Correa et al., 2022), for example, by using the rubric of the Wellbeing Economy. They advocate a wholesale shift in priorities, away from growth as an end on its own and towards the set of factors that more directly enhance quality of life and wellbeing. Altogether there is much support for the view that growth can promote health, but only “in conjunction with other life-supporting priorities.” By the same token, one too many studies provide reasons for suspicion toward the advocacy of an unrestrained market and a diminished role of government. Various narratives show how giving free rein to the pursuit of business interests—what we may call the commercial determinants of health (Kickbusch, et al., 2016)—has been highly detrimental to societies (McGarity, 2013; Freudenberg & Galea, 2008; Moss, 2014).

A complementary literature relates to the response of governments to economic crisis. Stuckler and Basu (2013) cite evidence linking policies of austerity in Greece to the spread of HIV, not the least because of budget cuts to essential health services. They also connect mortality spikes in Eastern Europe to the imposition of an economically liberal policy philosophy after the fall of communism. Using the UK as a case study, in a recent report, McCartney et al. (2022) explain how austerity policies halted a long-term decline in mortality that had been occurring in this country through 2010. Various austerity-minded economic policies resulted in cuts to social welfare, more homelessness, less investment in healthcare, and thus a disproportionate, detrimental impact on poorer households and communities especially. Yet findings that reductions in welfare benefits have harmed families are unsurprising, considering the evidence connecting household income to health (Link & Phelan, 1995; 2010). From the larger literature on the “social” determinants of health, we know that household income, educational attainment, and other markers of social standing have much bearing on future health, which implicates policies that in any way harm people’s access to these resources. Even the International Monetary Fund, which often required austerity policies as part of its lending program for developing countries, has acknowledged the likely failures of such policies (Ostry et al., 2016). Such programs seriously undermined the sovereignty of these countries over their economic policies, forcing them to cut essential services.

Many more scholars find the case for liberal, laissez-faire economy to be unconvincing from a population health perspective. Barlow (2018) for instance does not find any consistent benefit of economic liberalization for child health in her analysis of 36 policy experiments. Nor is there a convincing case for tax cuts as a catchall solution for growth in recent economic studies (Prillaman and Meier, 2014; Hope & Limberg, 2022; Suzuki, 2022; Gechert & Heimberger, 2022). Along these lines, Stiglitz (2010, 2015) discusses how many popular economic policies over the last few decades have been short-sighted, such as those involving the removal of regulatory protections in the time leading up to the Great Recession or that worsened income inequality. Rather, choice of tax policy could help improve population health if it is based on a holistic appreciation of the needs of citizens (Mccoy et al., 2017). There is also a more general connection between egalitarian economic policy and health. Recent systematic reviews see the benefit in reducing market inequities for health (McCartney et al., 2019; Barnish, Tørnes, and Nelson-Horne, 2018; Naik et al., 2019), for example, by supporting generous welfare programs, the availability of healthcare, or affordable housing.

Lastly, these observations underscore the importance of the political context. They resonate with the conclusions of economic historian Karl Polanyi (1944 / 1957) that decisions around the architecture of a country’s economy are unavoidably moral and political. In his analysis of the historical roots of industrialization, Polanyi shows how markets do not ever act autonomously, outside the oversight of citizens or their leaders.

7 Limitations

Before concluding, some important limitations must be noted. Coverage of such a large, diverse literature required some flexibility in my approach to the review. While carrying out this ambitious task, I may have missed some relevant studies in my literature search and given insufficient attention to others during later stages of the project. Further study on the subject is encouraged. The use of the framework that I offer may help facilitate this work.

8 Conclusions

Surely, for many scholars, the relationship between economic growth and population health is far from clear. This is not the least due to the enormous size and diversity of this literature, which shows substantial disagreement about what economic growth is supposed to do for us. Nevertheless, I argue that a sense of consensus is much more likely once we have clarified which aspects of the health-growth relationship we are interested in. Many current studies illustrate how this is really a multifaceted relationship. Growth could be construed as a factor supporting better population health, although this case is strongest over the long run, in terms of overall mortality risk alongside certain kinds of morbidity, for poor countries especially, and as part of a broader program of public supports and services. Beyond these stringent criteria, the case for economic growth as a boon to health is more debatable. Not the least is the concern that growth can harm health. Yet some of the negative repercussions would seem to be preventable through careful reflection over policy choices. Needed is more research that explores the multivariable relationship between economic growth and health, such as by distinguishing between spurious and mediating effects more carefully. Altogether, a broader discussion is needed, and imminently so, about the areas where we agree.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Ahmed, N., & Andersson, R. (2000). Unintentional injury mortality and socio-economic development among 15-44-year-olds: In a health transition perspective. Public Health, 114, 416–422.

Alkotob, S. S., Cannedy, C., Harter, K., Movassagh, H., Paudel, B., Prunicki, M., Sampath, V., Schikowski, T., Smith, E., Zhao, Q., Traidl-Hoffmann, C., & Nadeau, K. C. (2020). Advances and novel developments in environmental influences on the development of atopic diseases. Allergy, 75(12), 3077–3086.

Anand, S., & Ravallion, M. (1993). Human development in poor countries: On the role of private incomes and public services. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7(1), 133–150.

Angelini, V., & Mierau, J. O. (2014). Born at the right time? Childhood health and the business cycle. Social Science & Medicine, 109, 35–43.

Antonietti, R., Falbo, P., & Fontini, F. (2021). The wealth of nations and the first wave of COVID-19 diffusion. Italian Economic Journal. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40797-021-00174-z

Baird, S., Friedmen, J., & Schady, N. (2011). Aggregate income shocks and infant mortality in the developing world. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(3), 847–856.

Ballester, J., Robine, J.-M., Herrmann, F. R., & Rodó, X. (2019). Effect of the Great Recession on regional mortality trends in Europe. Nature Communications, 10, 679.

Barlow, P. (2018). Does trade liberalization reduce child mortality in low- and middle-income countries? A synthetic control analysis of 36 policy experiments, 1963-2005. Social Science & Medicine, 205, 107–115.

Barnish, M., Tørnes, M., & Nelson-Horne, B. (2018). How much evidence is there that political factors are related to population health outcomes? An internationally comparative systematic review. BMJ Open, 8(10), e020886.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Beckfield, J., Olafsdottir, S., & Bakhtiari, E. (2013). Health inequalities in global context. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1014–1039.

Belpomme, D., Irigaray, P., Hardell, L., Clapp, R., Montagnier, L., Epstein, S., et al. (2007). The multitude and diversity of environmental carcinogens. Environmental Research, 105, 414–429.

Berg, A. G., & Ostry, J. D. (2017). Inequality and unsustainable growth: Two sides of the same coin? IMF Economic Review, 65, 792–815.

Biggs, B., King, L., Basu, S., & Stuckler, D. (2010). Is wealthier always healthier? The impact of national income level, inequality, and poverty on public health in Latin America. Social Science & Medicine, 71(2), 266–273.

Birchenall, J. A. (2007). Economic development and the escape from high mortality. World Development, 35(4), 543–568.

Bishai, D. M., & Kung, Y.-T. (2007). Macroeconomics. In S. Galea (Ed.), Macrosocial Determinants of Population Health (pp. 169–191). Springer Science + Business Media.

Bishai, D. M., Quresh, A., James, P., & Ghaffar, A. (2005). National road fatalities and economic development. Health Economics, 15(1), 65–81.

Bloom, D. E., & Canning, D. (2000). The health and wealth of nations. Science, 287(5456), 1207–1209.

Bloom, D., & Canning, D. (2001). Cumulative causality, economic growth, and the demographic transition. In N. Birdsall, A. C. Kelley, & S. W. Sinding (Eds.), Population matters: Demographic change, economic growth, and poverty in the developing world (pp. 165–198). Oxford University Press.

Bloom, D. E., & Canning, D. (2003). The health and poverty of nations: From theory to practice. Journal of Human Development, 4(1), 47–71.

Bloom, D. E., & Canning, D. (2007). Commentary: The Preston curve 30 years on: Still sparking fires. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36(3), 498–499.

Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., & Sevilla, J. (2004). The effect of health on economic growth: A production function approach. World Development, 32(1), 1–13.

Bode, A. M., Dong, Z., & Wang, H. (2016). Cancer prevention and control: Alarming challenges in China. National Science Review, 3(1), 117–127.

Bollyky, T. J., Templin, T., Andridge, C., & Dieleman, J. L. (2015). Understanding the relationships between noncommunicable diseases, unhealthy lifestyles, and country wealth. Health Affairs, 34(9), 1464–1471.

Bollyky, T. J., Templin, T., Cohen, M., Schoder, D., Dieleman, J. L., & Wigley, S. (2019). The relationships between democratic experience, adult health, and cause-specific mortality in 170 countries between 1980 and 2016: An observational analysis. Lancet, 393, 1628–1640.

Borowy, I. (2013). Global health and development: Conceptualizing health between economic growth and environmental sustainability. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 68(3), 451–485.

Brady, D., Kaya, Y., & Beckfield, J. (2007). Reassessing the effect of economic growth on well-being in less-developed countries, 1980-2003. Studies in Comparative International Development, 42, 1–35.

Brand-Correa, L., Brook, A., Büchs, M., Meier, P., Naik, Y., & O’Neill, D. W. (2022). Economics for people and planet—Moving beyond the neoclassical paradigm. The Lancet: Planetary Health, 6(4), e371–e379.

Brenner, M. H. (2005). Commentary: Economic growth is the basis of mortality rate decline in the 20th century—Experience of the United States, 1901-2000. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(6), 1214–1221.

Buchter, B., Dunkel, M., & Li, J. (2012). Multiple sclerosis: A disease of affluence? Neuroepidemiology, 39, 51–56.

Cantarero-Prieto, D., Pascual-Saez, M., & Gonzalez Diego, M. (2019). Examining an alcohol consumption Kuznets Curve for developed countries. Applied Economics Letters, 26(17), 1463–1466.

Casabonne, U., & Kenny, C. (2012). The best things in life are (nearly) free: Technology, knowledge, and global health. World Development, 40(1), 21–35.

Chang, D., Chang, X., He, Y., & Tan, K. J. K. (2022). The determinants of COVID-19 morbidity and mortality across countries. Scientific Reports, 12, 5888.

Chen, W., Clarke, J. A., & Roy, N. (2014). Health and wealth: Short panel Granger causality tests for developing countries. Journal of International Trade & Economic Development, 23(6), 755–784.

Coccia, M. (2013). The effect of country wealth on incidence of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research & Treatment, 141, 225–229.

Cole, W. M. (2019). Wealth and health revisited: Economic growth and wellbeing in developing countries, 1970 to 2015. Social Science Research, 77, 45–67.

Colgrove, J. (2002). The McKeown thesis: A historical controversy and its enduring influence. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 725–729.

Cranfield, J., & Inwood, K. (2007). The great transformation: A long-run perspective on physical well-being in Canada. Economics and Human Biology, 5, 204–228.

Curran, M., & Mahutga, M. C. (2018). Income inequality and health: A global gradient. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 59(4), 536–553.

Cutler, D., Deaton, A., & Lleras-Muney, A. (2006). The determinants of mortality. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(3), 97–120.

Dadgar, I., & Norström, T. (2020). Is there a link between all-cause mortality and economic fluctuations? Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 48, 770–780.

Dafni, U., Tsourti, Z., & Alatsathianos, I. (2019). Breast cancer statistics in the European Union: Incidence and survival across European countries. Breast Care, 14(6), 344–352.

Datta, S. C., & Reimer, J. J. (2013). Malaria and economic development. Review of Development Economics, 17(1), 1–15.

Davidson, A. (2019). Social determinants of health: A comparative approach (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 22(2), 53–72.

Deaton, A. (2013). The great escape: Health, wealth, and the origins of inequality. Princeton University Press.

Dhrifi, A., Alnahdi, S., & Jaziri, R. (2021). The causal links among economic growth, education and health: Evidence from developed and developing countries. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 12(3), 1477–1493.

Dinda, S. (2004). Environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis: A survey. Ecological Economics, 49(4), 431–455.

Djordjevic, M., Salom, I., Markovic, S., Rodic, A., Milicevic, O., & Djordjevic, M. (2021). Inferring the main drivers of SARS-CoV-2 global transmissibility by feature selection methods. GeoHealth, 5, e2021GH000432. https://doi.org/10.1029/2021GH000432

Durkheim, E. (2006). On suicide (R. Buss, Trans.). Penguin Classics. (Originally published in 1897).

Eozenou, P. H.-V., Neelsen, S., & Lindelow, M. (2021). Child health outcome inequalities in low and middle income countries. Health Systems & Reform, 7(2), e1934955.

Ezzati, M., Vander, H. S., Lawes, C. M. M., Leach, R., James, W. T. P., Lopez, A. D., et al. (2005). Rethinking the ‘diseases of affluence’ paradigm: Global patterns of nutritional risks in relation to economic development. PLoS Medicine, 2(5), e133.

Farzanegan, M. R., Feizi, M., & Gholipour, H. F. (2021). Globalization and the outbreak of COVID-19: An empirical analysis. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(3), 105.

Ferreira, I. A., Gisselquist, R. M., & Tarp, F. (2022). On the impact of inequality on growth, human development, and governance. International Studies Review, 24(1), viab058. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viab058

Filmer, D., & Pritchett, L. (1999). The impact of public spending on health: Does money matter? Social Science & Medicine, 49(10), 1309–1323.

Firebaugh, G., & Beck, F. D. (1994). Does economic growth benefit the masses? Growth, dependence, and welfare in the third world. American Sociological Review, 59(5), 631–653.

Fogel, R. W. (1997). New findings on secular trends in nutrition and mortality: Some implications for population theory. In M. Rosenzweig & O. Stark (Eds.), Handbook of Population and Family Economics (Vol. 1A, pp. 433–481). Elsevier.

Fogel, R. W. (2004). The escape from hunger and premature death, 1700-2100: Europe, America, and the Third World. Cambridge University Press.

Frank, S. M., et al. (2019). Consumption of fruits and vegetables among individuals 15 years and older in 28 low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Nutrition, 149, 1252–1259.

French, D. (2012). Causation between health and income: A need to panic. Empirical Economics, 42(2), 583–601.

Freudenberg, N., & Galea, S. (2008). The impact of corporate practices on health: Implications for health policy. Journal of Public Health Policy, 29(1), 86–104.

Frimpong, P. B., & Adu, G. (2014). Population health and economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: A panel cointegration analysis. Journal of African Business, 15(1), 36–48.

Galea, S., Riddle, M., & Kaplan, G. A. (2010). Causal thinking and complex system approaches in epidemiology. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39, 97–106.

Garas, A., Guthmuller, S., & Lapatinas, A. (2021). The development of nations conditions the disease space. PlosOne, 16(1), e0244843.

Gechert, S., & Heimberger, P. (2022). Do corporate tax cuts boost economic growth? European Economic Review, 147, 104157.

Gerdtham, U.-G., & Ruhm, C. J. (2006). Deaths rise in good economic times: Evidence from the OECD. Economics & Human Biology, 4(3), 298–316.

Grant, W. B. (2014). A multicountry ecological study of cancer incidence rates in 2008 with respect to various risk-modifying factors. Nutrients, 6(1), 163–189.

Grecu, A. M., & Rotthoff, K. W. (2015). Economic growth and obesity: Findings of an obesity Kuznets curve. Applied Economic Letters, 22(7), 539–543.

Grossman, G. M., & Krueger, A. B. (1995). Economic growth and the environment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110(2), 353–377.

Haass, R. (2022). The dangerous decade: A foreign policy for a world of crisis. Foreign Affairs, 101(5), 25–38.

Haberl, H., et al. (2020). A systematic review of the evidence on decoupling of GDP, resource use and GHG emissions, part II: Synthesizing the insights. Environmental Research Letters, 15(6), 065003.

Haddad, L., Alderman, H., Appleton, S., Song, L., & Yohannes, Y. (2003). Reducing child malnutrition: How far does income growth take us? World Bank Economic Review, 17(1), 107–131.

Haines, M. R. (2004). Growing incomes, shrinking people: Can economic development be hazardous to your health? Historical evidence for the United States, England, and the Netherlands in the nineteenth century. Social Science History, 28(2), 249–270.

Hashim, M. J., Alsuwaidi, A. R., & Khan, G. (2020). Population risk factors for COVID-19 mortality in 93 countries. Journal of Epidemiology and Global Health, 10(3), 204–208.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420.

Headey, D. D., & Ruel, M. T. (2022). Economic shocks predict increases in child wasting prevalence. Nature Communications, 13, 2157.

Herzer, D., & Nunnenkamp, P. (2015). Income inequality and health: Evidence from developed and developing countries. Economics: The Open-Access, Open-Assessment E-Journal, 9(2015-4), 1–57. https://doi.org/10.5018/economics-ejournal.ja.2015-4

Hertzman, C., & Siddiqi, A. (2000). Health and rapid economic change in the late twentieth century. Social Science & Medicine, 51(6), 809–819.

Holland, D. P., Person, A. K., & Stout, J. E. (2011). Did the ‘Great Recession’ produce a depression in tuberculosis incidence? International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, 15(5), 700–702.

Hope, D., & Limberg, J. (2022). The economic consequences of tax cuts for the rich. Socio-Economic Review, 20(2), 539–559.

Irigaray, P., Newby, J. A., Clapp, R., Hardell, L., Howard, V., Montagnier, L., Epstein, S., & Belpomme, D. (2007). Lifestyle-related factors and environmental agents causing cancer: An overview. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 61, 640–658.

Jamison, D. T., Murphy, S. M., & Sandbu, M. E. (2016). Why has under-5 mortality decreased at such different rates in different countries? Journal of Health Economics, 48, 16–25.

Janssens, J.-P., & Rieder, H. L. (2008). An ecological analysis of incidence of tuberculosis and per capita gross domestic product. European Respiratory Journal, 32(5), 1415–1416.

Jetter, M., Laudage, S., & Stadelmann, D. (2019). The intimate link between income levels and life expectancy: Global evidence from 213 years. Social Science Quarterly, 100(4), 1387–1403.

Kangas, O. (2002). Economic growth, inequality, and the economic position of the poor in 1985-1995: An international perspective. International Journal of Health Services, 32(2), 213–227.

Keefer, P., & Knack, S. (2002). Polarization, politics and property rights: Links between inequality and growth. Public Choice, 111(1-2), 127–154.

Kickbusch, I., Allen, L., & Franz, C. (2016). The commercial determinants of health. Lancet. Global Health, 4(12), e895–e896.

Kristjuhan, U., & Taidre, E. (2012). The last recession was good for life expectancy. Rejuvination Research, 15(2), 134–135.

Krugman, P. (2009). How did economists get it so wrong? New York Times Magazine (September 6). Available at https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/06/magazine/06Economic-t.html. Accessed 23 July 2020.

Laughter, M. R., et al. (2021). The global burden of atopic dermatitis: Lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study 1990–2017. British Journal of Dermatology, 184, 304–309.

Li, Y. R., Li, H. X., & Miao, C. H. (2016). Spatial assessment of cancer incidences and the risks of industrial wastewater emission in China. Sustainability, 8, 5.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. (1995). Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 35(Extra issue), 80–94.

Link, B. G., & Phelan, J. (2010). Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities. In C. Bird, P. Conrad, A. Fremont, & S. Timmermans (Eds.), Handbook of Medical Sociology (6th ed., pp. 3–17). Vanderbilt University Press.

Lutz, W., Crespo Cuaresma, J., Kebede, E., Prskawetz, A., Sanderson, W. C., & Striessnig, E. (2019). Education rather than age structure brings demographic dividend. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(26), 12798–12803.

Lutz, W., & Kebede, E. (2018). Education and health: Redrawing the Preston curve. Population and Development Review, 4(2), 343–361.

Luzzati, T., Parenti, A., & Rughi, T. (2018). Economic growth and cancer incidence. Ecological Economics, 146, 381–396.

Mankiw, N. G. (1995). The growth of nations. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 275–326.

Mankiw, N. G., Romer, D., & Weil, D. N. (1992). A contribution to the empirics of economic growth. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(2), 407–437.

Maruthappu, M., Watson, R. A., Watkins, J., Zeltner, T., Raine, R., & Atun, R. (2017). Effects of economic downturns on child mortality: A global economic analysis, 1981–2010. BMJ Global Health, 2, e000157.

Mathers, C. D., Shibuya, K., Boschi-Pinto, C., Lopez, A. D., & Murray, C. J. L. (2002). Global and regional estimates of cancer mortality and incidence by site: I. Application of regional cancer survival model to estimate cancer mortality distribution by site. BMC Cancer, 2, 36.

McCartney, G., Hearty, W., Arnot, J., Popham, F., Cumbers, A., & Mcmaster, R. (2019). Impact of political economy on population health: A systematic review of reviews. American Journal of Public Health, 109(6), e1–e12.

McCartney, G., Walsh, D., Fenton, L., & Devine, R. (2022). Resetting the course for population health: Evidence and recommendations to address stalled mortality improvements in Scotland and the rest of the UK. Glasgow Centre for Population Health, University of Glasgow Available at https://www.gcph.co.uk/publications/1036_resetting_the_course_for_population_health

Mccoy, D., Chigudu, S., & Tillmann, T. (2017). Framing the tax and health nexus: A neglected aspect of public health concern. Health Economics, Policy & Law, 12(2), 179–194.

McGarity, T. O. (2013). Freedom to harm: The lasting legacy of the laissez faire revival. Yale University Press.

McKeown, T. (1976). The Modern Rise of Population. Academic Press.

Michaelides, P. G., Theodoratou, O., & Konstantakis, K. N. (2020). Inflammatory bowel disease and economic activity: Panel data evidence for Europe. Applied Economics Letters, 27(1), 72–76.

Mo, P. H. (2000). Income inequality and economic growth. Kyklos, 53(3), 295–315.

Moss, M. (2014). Salt, Sugar, Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us. Signal Books.

Nagano, H., Puddim de Oliveira, J. A., Barros, A. K., & da Silva Costa Jr., A. (2020). The ‘Heart Kuznets Curve’? Understanding the relations between economic development and cardiac conditions. World Development, 132, 104953.

Naik, Y., Baker, P., Ismail, S. A., et al. (2019). Going upstream: An umbrella review of the macroeconomic determinants of health and health inequalities. BMC Public Health, 19, 1678.

Nikolopoulos, G. K. (2015). National income inequality and declining GDP growth rates are associated with increases in HIV diagnoses among people who inject drugs in Europe: A panel data analysis. PLoS ONE, 10(4), e0122367.

Ogundaria, K., & Awokuseb, T. (2018). Human capital contribution to economic growth in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does health status matter more than education? Economic Analysis and Policy, 58, 131–140.

O’Hare, B., Makuta, I., Chiwaula, L., & Bar-Zeev, N. (2013). Income and child mortality in developing countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 106(10), 408–414.

Omran, A. R. (1971). The epidemiologic transition: A theory of the epidemiology of population change. The Milbank Quarterly, 49(4), 509–538.

Ostry, J. D., Loungani, P., & Furceri, D. (2016). Neoliberalism: Oversold? Finance & Development, 53(2), 38–41.

Patterson, A. C. (2017). Not all built the same? A comparative study of electoral systems and population health. Health & Place, 47, 90–99.

Pebley, A. R. (1998). Demography and the environment. Demography, 35(4), 377–389.

Pickett, K. E., & Wilkinson, R. G. (2015). Income inequality and health: A causal review. Social Science & Medicine, 128, 316–326.

Prados de la Escosura, L. (2013). Human development in Africa: A long-run perspective. Explorations in Economic History, 50, 179–204.

Preston, S. H. (1975). The changing relation between mortality and level of economic development. Population Studies, 29(2), 231–248.