Abstract

Men are underrepresented in caring degrees such as nursing, teaching and social work. There is a political ambition to attract more men to these educational programmes, in part because of the future, global need for professionals such as nurses and teachers. A common explanation for men not entering these programmes concerns the relational aspects. Care and empathy are important components in caring professions - skills which traditionally have been associated with the female role, and stereotypically viewed as less suitable for men. There has been too little research on how male students that do enter caring degrees evaluate the programmes’ emphasis on empathy, and furthermore whether this relates to their commitment to their future profession. In this study I show that there is no difference between male and female students in reporting that the study programmes have overemphasised empathy. However, reporting that the degree has given excessive weight to empathy is negatively related to commitment to the profession among male students and not among female students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Teaching, nursing, and social work are relational occupations, in which care and empathy are important competencies of the core professional activities (Abbott & Meerabeau, 1998; Mausethagen & Kostøl, 2010). The relational component of these professions has been a common explanation for the reluctance of men to enter them (Abbott & Meerabeau, 1998; Bradley, 2000; Mastekaasa & Smeby, 2008). Projections show that there is a growing need for so-called caring professionals across Europe, especially in nursing and teaching (European Commission, 2020). Attracting individuals to choose these education paths is therefore vital, followed by the need to keep them engaged throughout their education and during their time in the workforce. Above all, there is a political ambition to attract more men, who are currently underrepresented in these professions and the education (Myklebust et al., 2019; DBH, 2022).

Nursing, social work and teaching have been viewed as traditionally feminine occupations, associated with low status, and therefore deemed as being less desirable and unsuitable for men. The literature also exhibits that men could experience difficulties in female dominated degrees, especially in the recruitment phase: In a review investigating pre-registered nursing students’ view on barriers and facilitators in recruiting men to nursing programmes, male nurses reported the perception of female nurses and the society in general viewing male nurses as being less caring (Gavine et al., 2020). Whitford et al. (2020) furthermore found that nursing was characterised as a female occupation, not suitable for men. Stott (2007) found that male nursing students were concerned with whether they were able to conduct caring work in an appropriate manner, which they reported was associated with being feminine. The same tendency has been found in primary school teacher education. Student teachers report a common reason for fewer men applying being due to the occupation being viewed as a feminine job, one in which values associated with the “mother role,” such as empathy and care, is central (Drudy, 2008). In the social work profession, the minority of male students has been explained because social work education contains “gendered praxises” (Christie, 1998), and it is difficult for male students to fully master these gendered praxises, because they relate to traditional feminine values such as caring and nurturing (Abbott & Meerabeau, 1998; Crabtree, 2014).

In a recent study from Norway, it was found that male students in female dominated programmes had higher drop our rates compared to women (Abrahamsen Bente, 2020). Although this is not a consistent finding internationally (Mastekaasa & Smeby, 2008; Meyer & Strauß, 2019; Riegle-Crumb et al., 2016), it actualises a question of whether non-completion among men in part relates to the same reasons as many men avoid entering this type of education in the first place. Research into the experience of being male in female dominated education is predominantly qualitative and usually focuses on the experience of being a gender minority (Myklebust, 2020). Although perspectives around empathy and caring aspects often are a theme in these studies, they usually centre around male students’ perception of how others view them (Crabtree, 2014; Meadus & Twomey, 2011). Few of these studies explicitly address male students’ perception of how empathy is handled in the education and training, and whether this is associated with their identification within their future profession.

One way of getting information on students’ evaluation of how aspects of empathy is handled in the educational programme, is through assessing learning outcomes. Growing attention has been given to how and what students learn in higher education, often measured through self-evaluation of attainment of relevant skills (Caspersen et al., 2017). Empathy is seen as a core skill and value for the caring profession, and a necessity if the job is to be done properly (Begley, 2010; Kemp & Reupert, 2012). Measuring learning outcomes through self-report captures students’ attitudes towards whether their education contributes to acquiring relevant competencies and not actual acquired learning (Gonyea & Miller, 2011). Their attitude towards whether the training has equipped them with sufficient learning of empathy could be associated with their attitude towards their future profession. Considering the above argument that males are less attracted to these educations because of the relational aspect, the overall research question is: Do male students in care education feel the programme has given too much weight on empathy learning outcomes compared to female students, and is this associated with lower professional commitment for male students?

As a contrast, students’ assessment of leadership learning outcome will also be investigated. According to scholars such as Brass & Holloway (2021), the caring professions have become more managerial and bureaucratic during the last few decades, actualising the need for managerial skills. In parallel with this, male students in caring occupations are more often attracted to leadership positions and have a higher likelihood of filling them (Abrahamsen & Storvik, 2019; Karlsen, 2012). By including learning outcomes related to both empathic skills and leadership skills we will be able to say (1) whether there is something unique with the provision of empathy skills for students’ commitment to the profession; and (2) whether different types of skills predict professional commitment to become caring professionals differently for men and women.

Professional commitment in relational education

Professional commitment is defined as the individual’s attitudes and bond towards his or her profession (Klein et al., 2013). In the workforce, high levels of professional commitment are associated with outcomes that benefit both the employer and the employee, such as a reduced intention to leave the profession and higher levels of job satisfaction (Lee et al., 2000). For students in various short professional degrees the formation of commitment is in process even while they are in training (e.g., Gan 2021). Compared to the disciplinary programmes, the result is more defined as they are going into a specific line of work. Students start to adopt and align with the core values of their future profession, contributing to commitment to and identification with the profession. Taking on the identity as a professional and thus becoming committed to the profession is seen as an important mechanism for developing appropriate professional qualifications and skills (Myklebust, 2020).

Professional commitment is highly relevant when studying the propensity to drop out, as early commitment to the profession, could be associated with a heightened chance of academic persistence (Tinto, 1987). One of the more dominating theories in the literature on dropping out is Tinto’s model of student departure. In Tinto’s model, commitment is an important factor keeping students from leaving the education programme. Tinto’s model was developed mainly to understand students in generic fields such as humanities and social science, and therefore commitment to the institution and goal commitment have first been given attention. For students in professional programmes, professional commitment could be seen as a form of goal commitment, where the goal of the study is to become a professional. Thus, commitment to a future vocation could be an important motivational factor enhancing the likelihood of persistence. Understanding the antecedents of a student’s professional commitment and whether there are gender differences would be valuable. Identifying the factors that contribute to commitment could lead to enhanced persistence by students when studying.

Development of professional commitment is a result of congruence or a match between the person’s characteristics and the characteristics of the profession (Cable & DeRue, 2002; Klein et al., 2013). There are several ways in which the person and the profession can be compatible, such as by holding the traits, values, and skills necessary to meet the tasks of the profession (Kristof-Brown & Guay, 2011). In the relational professions, holding empathic skills and dispositions are often seen as a prerequisite to being able to do a good job. This is highlighted in social work, nursing, and teaching (Begley, 2010; Myklebust, 2020). The type of skills and competencies which are emphasised during the degree will inform the student about what is important in order to become a “good” professional and may possibly also predict their level of commitment.

Gender and professional commitment

A review of the literature on gender differences and commitment showed mixed results: In some studies, male primary school teachers and social workers had a tendency to have a lower level of professional commitment, compared to female professionals (Carmeli & Freund, 2009; Ingersoll, 1997), while in other studies, researchers have found no difference in commitment between male and female students in their first academic year (Freund et al., 2013) and student teachers across academic years (Moses et al., 2019). The mechanism that might explain the gender difference is seldom investigated. One exception is a study by Moses et al., (2019), conducted on Tanzanian teacher education students. In this study, perceived gender roles were included as a predictor of a student’s commitment. Gender roles were conceptualised by the extent to which students identified with stereotypical masculine and feminine traits. Feminine traits were being affectionate, nurturing, and empathic, while masculine traits assessed independence, leadership abilities and competitiveness. In Moses et al.’s (2019) study, only androgyn gender roles emerged, meaning that students had similar levels of masculine and feminine traits, although varying in strength. Students scoring high on both feminine and masculine traits generally had more commitment than students who scored low (and moderate) on feminine and masculine traits. The study did not investigate whether it is the combination of strong masculine and feminine traits that drives commitment, or whether there are specific traits that are associated with commitment, such as being empathic.

Empathy

There are several definitions of empathy, and most commonly these can be grouped into two categories, as affective and cognitive understandings of empathy (Reniers et al., 2011). When talking about empathy as a professional skill, the cognitive component has predominantly been emphasised (Hojat, 2007). The ability to understand the other person’s situation, rather than feel an emotional concern, is seen as crucial in doing one’s job. Correctly understanding the situation is important for responding with the right types of action. Empathy is associated with, but not solely determined by the individual’s personality traits (Melchers et al., 2016). Empathy can in part be learnt, which is of special relevance in professional education (Engbers, 2020). A review investigating the effect of empathy training intervention in nursing found an enhancement in skills associated with empathy (Engbers, 2020). Interventions designed to take the other’s perspective, influencing the cognitive component of empathy, were seen as especially effectful.

As stated above, professional commitment is formed when the individual experiences a match between their own personal skills and values, and those of the profession (Klein et al., 2013). Based on this, it is likely that students in caring professions on average will have higher levels of commitment when they feel their degree has provided appropriate levels of empathy learning. Given the assumption that one reason for men dropping out more frequently in nursing is the orientation towards caring values, one could expect that male students more often than female students perceive the education to have had a focus on empathy learning that was too extensive, and that this could result in a negative effect on professional commitment. In comparison, managerial skills should predict professional commitment in the same manner. Although the caring professions have become more bureaucratic, it is unlikely to be perceived as a core task of these professions. On the other hand, male students in caring professions have career preferences associated with leadership more often than female students do, which could lead them to request more focus on such skills.

In this study, I focused on students’ perceptions of congruence between the weight they perceive the degree should have given to empathic and leadership skills to be a good professional, and the weight they perceived the degree had given to empathy and leadership skills. The students were in their third and final academic year. Actual empathic and leadership traits or skills are not measured in this study. Even though this could be influencing how the students evaluate learning outcomes (e.g. Penprase et al., 2015), the focus in this study rather lies on their attitudes towards whether the education has accommodated for these skills and whether this attitude relates to commitment to their future profession.

The following hypotheses were formulated:

-

1)

Compared to female students, male students will perceive that empathic learning outcomes had been given too much weight.

-

2)

Perceiving positive incongruence, the education emphasising empathic skills more than deemed appropriate will predict lower levels of professional commitment among male students, but not among female students.

-

3)

Perceiving negative incongruence, the education emphasising empathic skills less than was deemed appropriate, will predict lower levels of professional commitment among female students, but not among male students.

-

4)

Compared to female students, male students will perceive to a larger extent that the education had been given too little weight on managerial skills.

-

5)

Perceiving either positive or negative leadership skill incongruence, the education emphasising leadership either less or more than was deemed appropriate, is unrelated to professional commitment.

Methods

The data used for analysis came from StudData, the Norwegian panel survey of professional students. StudData has several panels and waves, investigating various aspects of the educational experience, such as satisfaction, support, motivation, and learnings outcomes. The present data were collected between January and June 2015, in the students’ final semester. All higher education institutions offering bachelor’s programmes in shorter professional degrees were invited to participate in StudData. 3 out of 12 institutions offering a nursing degree; 5 out of 11 institutions offering a degree in social work; and 4 out 9 institutions offering degrees in primary teaching took part in the study. A variety of both larger and smaller higher institutions participated in the study. The questionnaires were distributed in class by the teacher or an administrative official. The students were informed that the survey was voluntary. The response rate varied between educational groups. Primary teacher education in Norway is divided in two study programmes: primary teaching for school levels 1–7 and primary teaching for school levels 5–10. Sixty-one per cent of the invited students in primary teaching for school levels 1–7, 48 per cent of the invited students in primary teaching for school levels 5–10, 62 per cent of the invited nursing students, and 72 per cent of the invited social work students participated in the survey.

Professional commitment

The dependent variable professional commitment is measured by the Career Commitment Scale, developed by Blau (1988). The Career Commitment Scale is a seven-item measure of one’s attitude towards one’s profession / vocation – that is, an individual’s degree of commitment to a career field (e.g., “I like this vocation too much to give it up”). Items are rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale has received support for being a psychometrically valid and reliable measure (Blau, 1988, 1999). Some of the items were negatively worded, and these were reversed before computing the mean sum score. The internal reliability of the Career Commitment Scale reached a satisfactory level in this study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.867.

Empathy skills/learning outcomes

Measuring students’ and newly graduates’ achieved learning outcomes has been of interest both in international, large scale research surveys and national graduate surveys (Caspersen et al., 2017). Indexes typically measure self-reported levels of a variety of both achieved generic and field specific skills and competencies. Even though these indexes often are similar, there is no definite consensus of how to measure acquired learning outcomes. The sample in this study was presented with the same index as used by Caspersen et al., (2014). Caspersen et al., (2014) performed a PCA of 21 items measuring learning outcomes and found that three factors could be extracted. These factors were called (i) social and ethical learning outcomes (ii) leadership learning outcomes and (iii) practical learning outcomes. Of relevance to this study is the “The social and ethical learning outcomes” factor which consisted of six items: ‘verbal communication skills’, ‘tolerance and ability to value others’ points of view’, ‘ability to make ethical judgments’, ‘the ability to empathise with other people’s situation’, ‘values and attitudes’ and ‘being able to cope with the emotional challenges in the work’. As the main interest of the present study was to look specifically on empathy learning outcomes, the item “the ability to empathise with other people’s situation” was used as a measure of empathy learning outcomes.

Unlike in Caspersen et al.s’ study (2014), where the students were asked to evaluate to what degree they had acquired the competences as a result of their education, a discrepancy score was calculated in the present study. In their third year, the students were asked to evaluate the extent to which (1) they feel these outcomes should have been emphasised during the degree to become a good worker and (2) the extent to which they perceive they had acquired the competences as a result of their education. The items are rated from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree).

A discrepancy score was computed by subtracting the value given for what students’ have acquired (regarding the ability to empathise with other people’s situation) from what they think should have been emphasised (regarding the ability to empathise with other people’s situation). A negative value indicates that the students feel they have learnt less than needed about the ability to empathise to become a good worker, zero indicates that they have learnt the appropriate amount, and a positive value indicates that they feel they have learnt more than needed about the ability to empathise to become a good worker. The two dummy variables Empathy underemphasised, and Empathy overemphasised were computed. Those having a negative value on the sum score feeling they have learnt less then needed are coded 1 on the Empathy underemphasised variable, and everyone else are coded zero, while those that have a positive value and feel they have learnt more are coded 1 on the Empathy overemphasised variable, and everyone else is coded zero which means they perceive to have learnt the appropriate amount of empathy.

There are several measures of self-reported empathy, but few items which measure empathy learning outcomes. To my knowledge the present study is the first to have looked exclusively on this, thus no existing studies validating this measure have been conducted. This study should therefore be seen as the initial exploration of empathy learning outcome, and future studies are needed to validate the present study. That being said, the learning outcome in this study resembles SITE, which measures self-reported empathy (Konrath et al., 2018). SITE asks respondents with one item to what extent the following statement describes him or her: “I am an empathic person.” SITE is a validated measure, and does not differentiate between emotional and cognitive empathy, even though it seems to be more strongly correlated with emotional empathy (Konrath et al., 2018). Based on this there are reasons to believe that the empathy learning outcome in this study, although not covering all aspects of empathy learning, measures the concept adequately at a group level.

Leadership skills

Two items taken from the same index as the empathy learning outcome, were used to compute a subscore measuring discrepancy in leadership learning outcomes. In Caspersen et al.’s study the factor labelled leadership learning outcomes consisted of 7 items, ability to: ‘work under pressure’, ‘work independently’, ‘interpersonal skills’, ‘take initiative’, ‘written communication skills’, ‘leadership-abilities and take responsibility’. The same factor structure as in Caspersen et al., (2014) was not reproduced, and only two items seemed to reflect leadership: ‘leadership-abilities’ and ‘ability to take responsibility’. Cronbach’s alpha reached 0.769. Except from Caspersen et al.’s study, there do not seem to exist studies validating leadership learning outcome measures based on these items. Thus, the same applies for the leadership outcomes measure as the empathy measure; further studies should be conducted to validate both the findings and the measurement.

The leadership discrepancy learning outcome is computed the same way as the empathy learning outcome, namely as a difference between what students have learnt from what they think should have been emphasised in the degree. Two dummy variables Leadership underemphasised, and Leadership overemphasised were computed. Those having a negative value on the sum score feeling they have learnt less then needed are coded 1 on the Leadership underemphasised variable, and everyone else are coded zero, while those that have a positive value and feel they have learnt more are coded 1 on the Leadership overemphasised variable, and everyone else is coded zero which means they report to have learnt the appropriate amount of empathy.

Results

The education programme with the largest majority of women is nursing, while primary teaching has a higher proportion of male students, Table 1. Women were significantly younger than men among primary teaching levels 5–10 and nursing, Table 1.

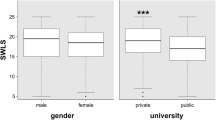

Men scored significantly lower than women on professional commitment, with a mean of 3.6 for men and 4 for women t(870) = -4.621, p < 0.001. Figure 1.

A larger proportion of men than women reported that the empathy was underemphasised in their degree. Even though the difference is relatively large, it is not statistically significant. There is a larger proportion of women reporting that the degree emphasised empathy to an appropriate degree, while there was almost identical proportions of men and women reporting that empathy has been overemphasised, X2(2, N = 832) = 4.792, p = 0.091. Table 2. Therefore, hypothesis 1 was not supported.

For weight given leadership skills, there is no gender difference, X2(2, N = 837) = 2.884, p = 0.236. Table 3. Hypothesis 4 was therefore not supported.

Comparing the mean between empathy and leadership skills, the sample in total had a significantly lower mean in leadership skills, -0.7593, compared to empathy, -0.4214, t(832) = -9.141, p < 0.001. This means that the students perceived the educational programme to have given them less than desired learning in leadership skills compared to empathy skills.

Two multiple linear regression models were estimated, with professional commitment as the dependent variable. Professional commitment had a range of 4. The first analysis examined the control variables: Age, gender, and dummy of educational groups, as well as a dummy of empathy learning variable and interaction between gender and empathy, Table 4.

Step 1 of the regression analysis show that female students had significantly higher levels of commitment compared to male students, even when controlling for other variables. The analysis furthermore showed that age was positively related to professional commitment: older students had higher levels of commitment. Teacher education students teaching levels 1–7, had significantly higher levels of commitment compared to nursing students. Looking at the predictor variables, students reporting that the study programme had either underemphasised or overemphasized empathy did not significantly predict professional commitment. However, when including the interaction term in step 2 of the regression analysis both a significant main effect of overemphasising empathy and the interaction term between gender and overemphasising empathy was significant. The results show that males that perceive the education to have overemphasised empathy are associated with lower levels of professional commitment (B = -0.568). The interaction term shows the difference in regression coefficients between male and female students (B = 0.587), meaning that for female students the coefficient between overemphasise and professional commitment is 0.017 (-0.569 + 0.587). Thus, for female students there is not a negative relation between perceiving the education to have overemphasised empathy and professional commitment, which supported hypothesis 2. Although including the interaction term resulted in a significantly better fit of the regression model, it only explained 1% more of the variance in professional commitment. Hypothesis 3 did not receive support: Perceiving that the education emphasised empathy skills less than deemed appropriate did not predict lower levels of professional commitment among female students.

Table 5 shows the second linear regression, which also examined the weight given to leadership skills.

Neither of the two leadership skill variables predicted professional commitment, which was in support of hypothesis 5.

Discussion

The results of the analyses illustrate that there are differences between male and female students in caring educational programmes, when it comes to professional commitment and perception of empathy learning in education, and how these are related. As earlier studies have also illustrated, comparison of means showed that male students in the present study reported significantly lower levels of professional commitment, compared to women (Carmeli & Freund, 2009; Ingersoll, 1997). Some have explained lower levels of professional commitment with the fact that male students to a larger extent choose forms of education for instrumental reasons, such as job security and status (Balyer & Özcan, 2014). This could affect the extent to which male students identify with the profession compared to female students. Specifically in caring education and training, one explanation for fewer men entering these degrees concerns men feeling alienated in meeting with how care and empathy are handled and taught in the programme, which is often associated with being traditionally feminine professions (Crabtree, 2014; Drudy, 2008; Whitford et al., 2020).

Based on this, I hypothesised that male students would perceive the degrees to have given empathy too much weight. This was not the case. Although failing to reach significance, the tendency was in the opposite direction: A larger proportion of male students, compared to female students, reported that empathy was underemphasised; thus, they perceived that they had been learning less about the importance of empathy than was necessary to be prepared for life in the workforce. It is important to underline that this difference was not statistically significant, but as the difference is substantial investigating how this folds out in further studies could be valuable. As empathy learning outcome was measured with one item, a broader measure of empathy learning could lead to a significant result. Should it be the case that male students feel they have not learnt adequate amount of empathy, this would be important to uncover.

The regression analyses showed that perceiving the education to have over-emphasised empathy predicted lower levels of professional commitment for men but not for women, This was in line with hypothesis 2. When students feel that their degrees have placed more emphasis on empathy than what they deemed necessary, it could make them infer that the education (and in extension, the occupation) value empathy to a greater extent than they themselves do. This might contribute to incongruence, a feeling of not being a good fit in the profession, which in turn could be negative for students’ identification with the profession and their commitment to it. This incongruence seems to contribute to a stronger feeling of not fitting in among men compared to women. In previous studies, male professionals in female dominated occupations have reported that they experienced a stereotypical preconception that care is something which is associated with the female role (e.g., Gavine et al., 2020; Whitford et al., 2020; Christie, 1998; Drudy, 2008). Experiencing discrepancies on this specific skill could lead to a stereotypical view being confirmed, reinforcing the attitude that the educational programmes are not as suitable for men as for women.

According to person- environment fit theories, which explains the mechanisms for the development of professional commitment, congruence between person and occupation will lead to higher professional commitment (Cable & DeRue, 2002; Klein et al., 2013). Incongruence in empathy learning outcome could not explain all of the gender difference in professional commitment. The reason that male students do not have as strong of a bond towards their future profession as female students remains a question.

The assumption that difference in professional commitment would be explained by male students valuing and requesting more of leadership skills, was not confirmed. Future studies should therefore look more closely on other factors that might explain gender differences in professional commitment. Looking at whether motivation for entering the education explains difference between male and female students’ commitment could be interesting, as some studies indicate that male students more often have instrumental reasons (Balyer & Özcan, 2014).

Limitations and future research

This study was conducted among final year students, for whom there are reasons to believe they are members of a select group. Students who perceive that they do not fit in the education, training and the profession could have left earlier in the educational trajectory. According to Statistics Norway students from the educational bachelor’s fields ‘health, social work and sports’ and ‘primary school teachers’ have relative to other bachelor’s programmes a lower share of students departing from the field, with approximately 22% of students leaving (Andresen & Lervåg, 2022). How non-response might have affected the result of the study is hard to say. We cannot rule out that those who have left the programme have lower levels of empathy or professional commitment. One possibility is that the relationship between empathy skills and professional commitment would have been stronger if measured earlier, because of this. At the same time, final year students have more experience of how the training emphasised skills, which gives them a much broader basis for assessing their learning outcomes. In addition, it is valuable to investigate predictions of professional commitment among students who will soon transitioning into the workforce. One question to ask would then be if this could be related to where they apply to work.

In this study, empathy skill was measured by using only one item. Although one-item versions of empathy have been shown to be of acceptable validity (Konrath et al., 2018), it does not differentiate between different aspects of empathy, more specifically empathy as an affective skill and empathy as a cognitive skill. Research on empathy indicates that men seem to be more prone to have “stronger” cognitive empathy skills compared to affective empathy skills, while women seem to perform better on tests measuring affective empathy (Christov-Moore et al., 2014). Future research should investigate the degree to which the different aspects of empathy are taught in the degrees, and whether male and female students benefit from different forms of empathy learning: cognitive vs. affective.

Conclusion

This study shows that there is not a larger proportion of male students, compared to female students, reporting that their education excessively emphasised empathy. Although the difference does not reach statistical significance, the tendency is in the opposite direction: Men more often than women report that their education should have given more weight to empathy. In line with this, caring education should critically review how empathy is being taught during the programme. If there is an underlying assumption in the programme that empathy is a “feminine” trait brought into the study, it may explain why a larger proportion of men want to be trained in empathic skills. Alternatively, male students might feel that they encompass empathy skills to a lesser extent than female students do. Regardless of the cause, it is highly relevant for the education providers to be aware of this result, as studies have shown that it is possible to enhance empathy skills through correct training (Engbers, 2020). The negative association between reporting “excessive empathy” and professional commitment is stronger among men, compared to women. These male students could feel that they fit the stereotypical image of a caring professional to a lesser extent. It can be useful for these men to be shown during their education and training that other skills, related to problem solving, are also in high demand for practising in the profession. This informs us that more than one skill is needed to become a good professional.

References

Abbott, P., & Meerabeau, L. (1998). Professionals, Professionalization and the Caring Professions. I P. Abbott & L. Meerabeau (Red.), The sociology of the caring professions (s. 1–19). Psychology Press.

Abrahamsen, B., & Storvik, A. (2019). Nursing students’ career expectations: Gender differences and supply side explanations. 3, 16.

Abrahamsen Bente. (2020). Færre menn enn kvinner fullfører kvinnedominerte profesjonsutdanninger. TfS, 61(3), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1504-291X-2020-03-03

Andresen, S. M. H., & Lervåg, M. L. (2022). Frafall og bytter i universitets- og høgskoleutdanning Kartlegging av frafall og bytte av studieprogram eller institusjon blant de som startet på en gradsutdanning i 2012 (Nr. 2022/6). Statistisk sentralbyrå.

Balyer, A., & Özcan, K. (2014). Choosing Teaching Profession as a Career: Students’ Reasons. International Education Studies, 7. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v7n5p104

Begley, A. M. (2010). On being a good nurse: reflections on the past and preparing for the future. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 16(6), 525–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2010.01878.x

Blau, G. J. (1988). Further exploring the meaning and measurement of career commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 32(3), 284–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(88)90020-6

Blau, G. (1999). Early-Career job factors influencing the Professional Commitment of Medical Technologists. Academy of Management Journal, 42(6), 687–695. https://doi.org/10.5465/256989

Bradley, K. (2000). The incorporation of women into higher education: paradoxical outcomes? Sociology of Education, 73(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673196. JSTOR.

Brass, J., & Holloway, J. (2021). Re-professionalizing teaching: the new professionalism in the United States. Critical Studies in Education, 62(4), 519–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1579743

Cable, D. M., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The convergent and discriminant validity of subjective fit perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.875

Carmeli, A., & Freund, A. (2009). Linking Perceived External Prestige and Intentions to leave the Organization: the mediating role of job satisfaction and affective commitment. Journal of Social Service Research, 35(3), 236–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488370902900873

Caspersen, J., Frølich, N., Karlsen, H., & Aamodt, P. O. (2014). Learning outcomes across disciplines and professions: measurement and interpretation. Quality in Higher Education, 20(2), 195–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538322.2014.904587

Caspersen, J., Smeby, J. C., & Olaf Aamodt, P. (2017). Measuring learning outcomes. European Journal of Education, 52(1), 20–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12205

Christie, A. (1998). Is Social work a ‘Non-Traditional’ Occupation for Men? The British Journal of Social Work, 28(4), 491–510. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a011363

Christov-Moore, L., Simpson, E. A., Coudé, G., Grigaityte, K., Iacoboni, M., & Ferrari, P. F. (2014). Empathy: gender effects in brain and behavior. Beyond Sexual Selection: the evolution of sex differences from brain to behavior, 46, 604–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.09.001

Crabtree, J. P. (2014). Being Male in Female Spaces: Perceptions of Masculinity Amongst Male Social Work Students on a Qualifying Course. 4, 7–26.

DBH (2022). Opptakstall [Enrollment numbers]. Opptakstall. https://dbh.nsd.uib.no/statistikk/rapport.action?visningId=156&visKode=false&admdebug=false&columns=arstall!8!kjonn&index=1&formel=422&hier=studkode!9!instkode!9!progkode&sti=¶m=arstall%3D2020!8!2019!9!dep_id%3D1!9!nivakode%3DB3!8!B4!8!HK!8!YU!8!AR!8!LN!8!M2!8!ME!8!MX!8!HN!8!M5!8!PR

Drudy, S. (2008). Gender balance/gender bias: the teaching profession and the impact of feminisation. Gender and Education, 20(4), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250802190156

Engbers, R. A. (2020). Students’ perceptions of interventions designed to foster empathy: an integrative review. Nurse Education Today, 86, 104325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104325

European Commission, Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion, McGrath, J. (2020). Analysis of shortage and surplus occupations 2020, Publications Office. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2767/933528

Freund, A., Blit-Cohen, E., Cohen, A., & Dehan, N. (2013). Professional Commitment in Novice Social Work students: Socio-Demographic characteristics, motives and perceptions of the Profession. Social Work Education, 32(7), 867–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2012.717920

Gan, I. (2021). Registered Nurses’ metamorphosed “Real Job” experiences and nursing students’ vocational anticipatory socialization. Communication Studies, 72(4), 563–579. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2021.1953102

Gavine, A., Carson, M., Eccles, J., & Whitford, H. M. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to recruiting and retaining men on pre-registration nursing programmes in western countries: a systemised rapid review. Nurse Education Today, 88, 104368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104368

Gonyea, R. M., & Miller, A. (2011). Clearing the AIR about the use of self-reported gains in institutional research. New Directions for Institutional Research, 150, 99–111.

Hojat, M. (2007). Empathy in patient care: Antecedents, development, measurement, and outcomes (s. xxxvi, 295). Springer Science + Business Media.

Ingersoll, R. M. (1997). Teacher professionalization and teacher commitment: a multilevel analysis, SASS. U.S. Department of Education Office of Educational Research and Improvement.

Karlsen, H. (2012). Gender and ethnic differences in occupational positions and earnings among nurses and engineers in Norway: identical educational choices, unequal outcomes. Work Employment and Society, 26(2), 278–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017011432907

Kemp, H., & Reupert, A. (2012). There’s no big book on how to care”: Primary pre-service teachers’ experiences of caring. 37(9), 114–127. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.728838486904697

Klein, H. J., Molloy, J. C., & Cooper, J. T. (2013). Conceptual Foundations: Construct Definitions and Theoretical Representations of Workplace Commitments. I H. J. Klein, T. E. Becker, & J. P. Meyer (Red.), Commitments in Organizations Accumulated Wisdom and New directions (s. 3–36). Routledge.

Konrath, S., Meier, B. P., & Bushman, B. J. (2018). Development and validation of the single item Trait Empathy Scale (SITES). Journal of Research in Personality, 73, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2017.11.009. PubMed.

Kristof-Brown, A., & Guay, R. P. (2011). Person–environment fit. I APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol 3: Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization (s. 3–50). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12171-001

Lee, K., Carswell, J. J., & Allen, N. J. (2000). A meta-analytic review of occupational commitment: relations with person- and work-related variables. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(5), 799–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.799

Mastekaasa, A., & Smeby, J. C. (2008). Educational choice and persistence in male- and female-dominated fields. Higher Education, 55(2), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-006-9042-4

Mausethagen, S., & Kostøl, A. (2010). Det relasjonelle aspektet ved lærerrollen. NPT, 94(3), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.18261/ISSN1504-2987-2010-03-05

Meadus, R. J., & Twomey, J. C. (2011). Men Student Nurses: the nursing education experience. Nursing Forum, 46(4), 269–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2011.00239.x

Melchers, M. C., Li, M., Haas, B. W., Reuter, M., Bischoff, L., & Montag, C. (2016). Similar Personality Patterns Are Associated with Empathy in Four Different Countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 7. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00290

Meyer, J., & Strauß, S. (2019). The influence of gender composition in a field of study on students’ drop-out of higher education. European Journal of Education, 54(3), 443–456. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12357

Moses, I., Admiraal, W., Berry, A., & Saab, N. (2019). Student-teachers’ commitment to teaching and intentions to enter the teaching profession in Tanzania. South African Journal of Education, 39(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v39n1a1485

Myklebust, R. B. (2020). Skilful sailors and natural nurses. Exploring assessments of competence in female- and male-dominated study fields. Journal of Education and Work, 33(4), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2020.1820964

Myklebust, R. B., Afdal, H. W., Mausethagen, S., Risan, M., Tangen, T. N., & Wernø, I. L. (2019). Rekruttering av menn til grunnskolelærer-utdanning for trinn 1–7 (Nr. 19; Skriftserien 2019). Oslo Storbyuniversitetet.

Penprase, B., Oakley, B., Ternes, R., & Driscoll, D. (2015). Do higher dispositions for Empathy predispose males toward careers in nursing? A descriptive Correlational Design. Nursing Forum, 50(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12058.

Reniers, R. L. E. P., Corcoran, R., Drake, R., Shryane, N. M., & Völlm, B. A. (2011). The QCAE: a questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(1), 84–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.528484

Riegle-Crumb, C., King, B., & Moore, C. (2016). Do they stay or do they go? The switching decisions of individuals who enter gender atypical College Majors. Sex Roles, 74(9), 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0583-4. PubMed.

Stott, A. (2007). Exploring factors affecting attrition of male students from an undergraduate nursing course: a qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 27(4), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2006.05.013

Tinto, V. (1987). Leaving college: rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. University of Chicago Press.

Whitford, H. M., Marland, G. R., Carson, M. N., Bain, H., Eccles, J., Lee, J., & Taylor, J. (2020). An exploration of the influences on under-representation of male pre-registration nursing students. Nurse Education Today, 84, 104234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.104234

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the “Persist” research group at NIFU/SPS for valuable feedback on drafts of this paper.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway under Grant 283556.

Open access funding provided by Oslo New University College

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure statement

There are no relevant financial or non-financial competing interests to report.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nesje, K. When the education emphasises empathy: does it predict differences in professional commitment between male and female students in caring education?. Tert Educ Manag 29, 63–78 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-023-09116-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-023-09116-z