Abstract

Quantifier Raising usually exhibits finite-clause boundedness due to the syntactic and semantic constraints it is subject to (Fox 1995, 2000, Cecchetto 2004, a.o.). In this paper, I argue that QR out of a Mandarin prenominal pre-determiner RC is not only properly licensed, obeying both syntactic and semantic constraints, but also needed to account for the exceptional-scope effects observed across relative clause boundaries (Huang 1982, Aoun and Li 1993, a.o.). I further consider constructions where the exceptional-scope effects are not present, including relative clauses containing the focus-sensitive operator dou and full-sized subject RCs, and show that the absence of the exceptional-scope effects in these constructions follows directly from the proposed analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Subject to syntactic and semantic conditions, Quantifier Raising (QR) normally cannot cross a finite-clause boundary (Fox 1995, 2000, Reinhart 1995, Bruening 2001, Takahashi 2006, Mayr and Spector 2010, a.o.). However, exceptional application of QR is licensed given sufficient motivations, such as creating new scope relations or resolving antecedent-contained deletion (ACD) (Fox 2002, Wilder 2003, Cecchetto 2004; though see Overfelt 2020). Following current views on the syntactic and semantic constraints on QR, this paper presents a novel analysis of scope taking and binding out of Mandarin relative clauses (RCs), arguing that long QR out of a finite clause is not only properly licensed but also necessary in certain circumstances.

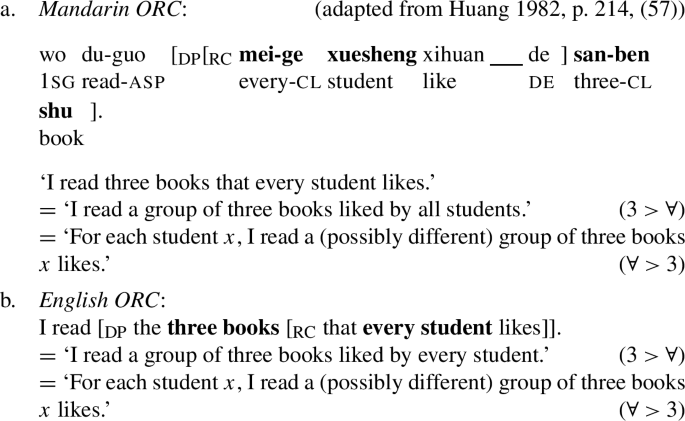

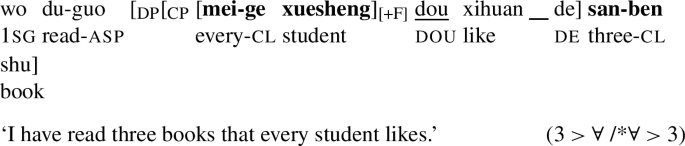

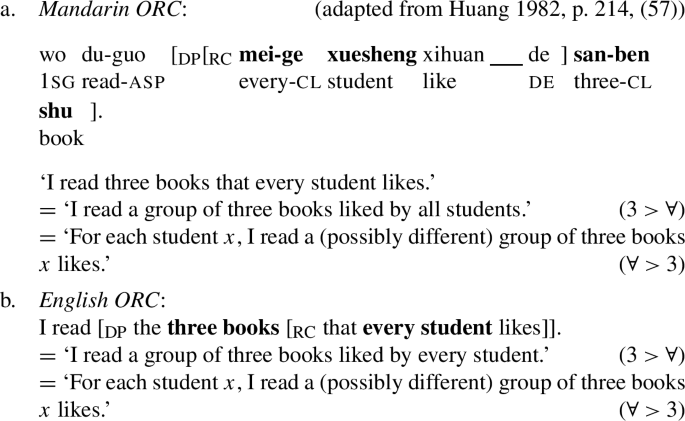

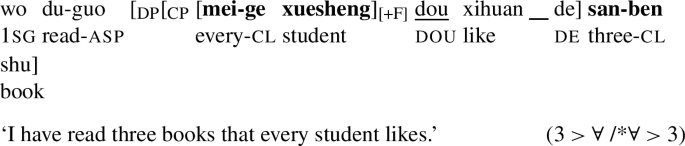

It has been observed in previous literature that an object relative clause (ORC) in Mandarin exhibits scope ambiguity between a QP in the subject position of the ORC (subj-QP) and an RC-external quantifier, as shown in (1a) (Huang 1982, Aoun and Li 1993, 2003),Footnote 1 similar to its English counterpart shown in (1b).

-

(1)

Furthermore, an RC-internal QP can also bind a matrix pronoun c-commanded by the RC-containing DP but not by the QP itself, as shown in (2a) (Huang 1982, 1983). A similar pattern has also been observed in English and Hebrew, as shown in (2b) (Doron 1982, Sharvit 1997, 1999, a.o.).

-

(2)

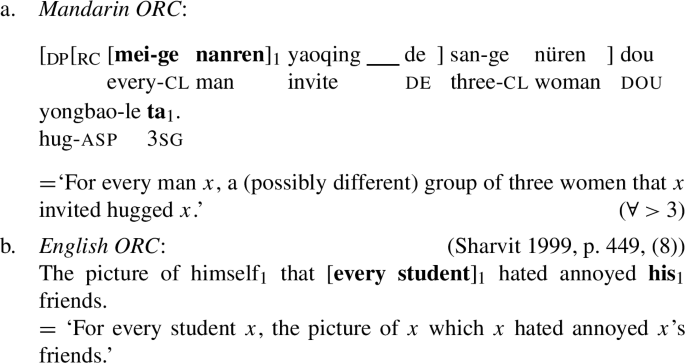

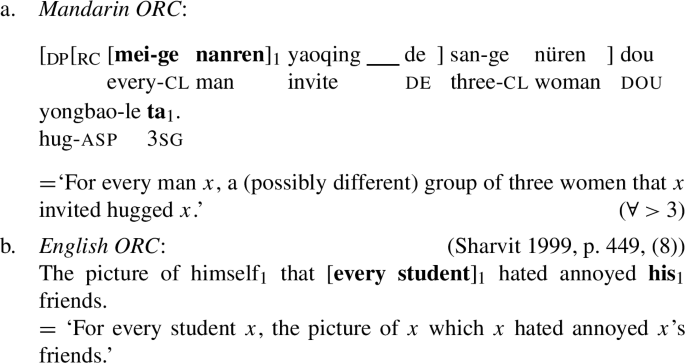

The scope ambiguity in ORCs (though not binding of pronouns outside the DP containing the relative clause) can potentially be derived from reconstruction of the RC-external numeral along with the RC-head back into the relative clause (as explored, e.g., by Larson and Wu 2018; Chen 2020). Aoun and Li (2003) have shown that Mandarin relative clauses exhibit reconstruction effects of the RC-head NP, and scope ambiguity can co-occur with reconstruction effects of the RC-head, as shown in (3), where scope ambiguity is available when the RC-head is forced to reconstruct for anaphora binding.

-

(3)

Scope ambiguity & anaphora binding

In this paper, I argue that even though reconstruction is necessary for Mandarin RCs, it is not sufficient to derive the full picture of scope interactions in Mandarin RCs. I propose that the scope interactions in a Mandarin prenominal, pre-D(eterminer) RC result from long QR of the RC-embedded QP out of the RC to the edge of the containing DP, where it takes wide scope over the RC-external QP. This apparently “exceptional” QR is in fact non-exceptional, because as I will show, the pre-D position of a Mandarin RC allows the RC-embedded QP to circumvent the relevant syntactic and semantic constraints on QR. The proposed analysis accounts for the observed scope interactions in Mandarin, along with their absence in certain constructions, without imposing language-specific constraints that are not independently motivated.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents more data on scope interactions beyond simple ORCs in Mandarin, specifically in relative clauses containing the particle dou (dou-RCs) and subject relative clauses; in some of these environments, exceptional scope effects are absent. Section 3 proposes a long QR analysis, with detailed derivation of the scope ambiguity and binding out of the containing DP in a Mandarin ORC. Section 4 applies the long QR analysis, along with an analysis of dou proposed by Xiang (2020), to account for the general absence of exceptional scope effects in dou-RCs. Section 5 investigates a case which seems to be a counterexample to the generalization that dou blocks exceptional scope and proposes a natural-function analysis for it, following Jacobson (1994) and Sharvit (1999). I show that this case is expected under the current analysis of dou and does not pose a challenge to the proposed long QR analysis. Section 6 focuses on Mandarin SRCs, where scope interaction is restricted in certain cases. Section 7 concludes the paper and discusses several puzzles left open for future research.

2 Scope interaction beyond simple ORCs

This section discusses the distribution of scope interactions in Mandarin RCs. I focus on two puzzles suggestive of a non-reconstruction based approach. These are the absence of scope interaction in Mandarin RCs containing dou, a focus-sensitive particle (Sect. 2.1), and scope interaction in subject RCs (Sect. 2.2).

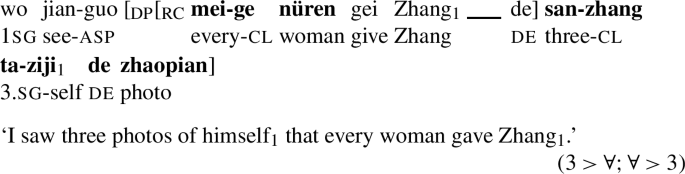

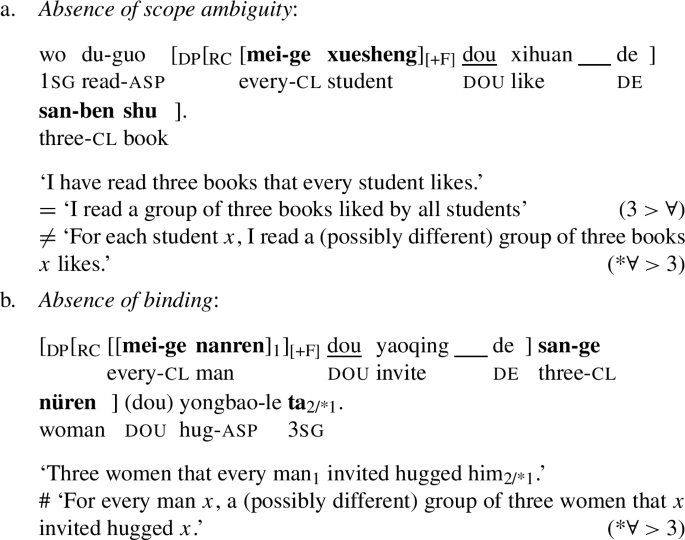

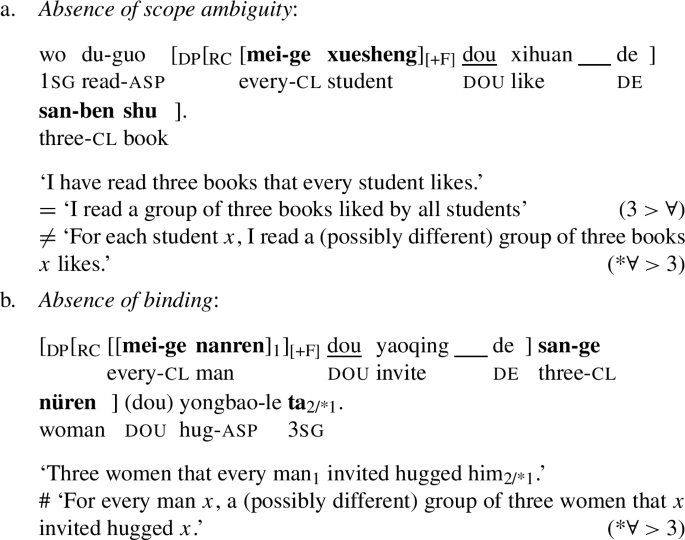

2.1 The blocking effect of dou

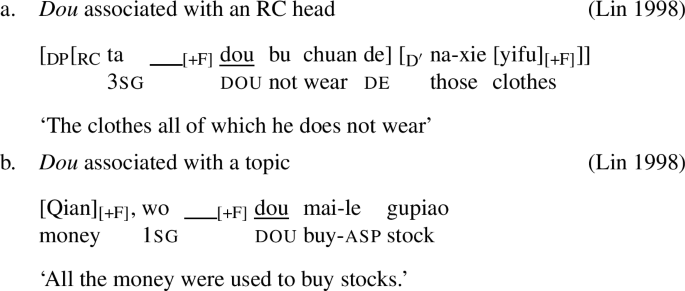

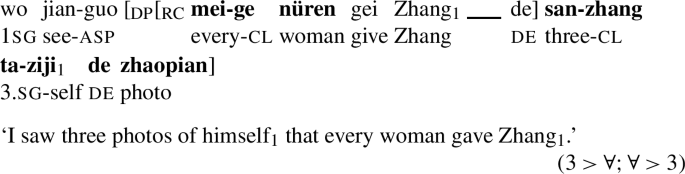

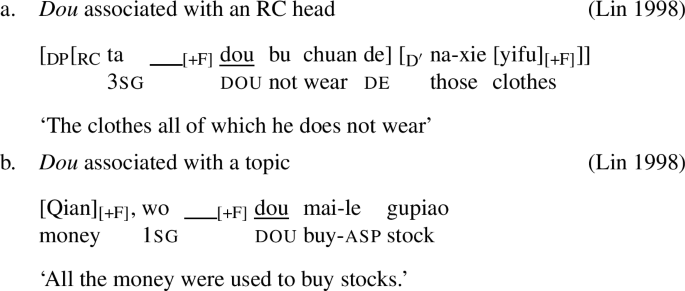

When the focus-sensitive particle dou is present inside the RC, the RC-embedded subj-QP is no longer able to take wide scope (Aoun and Li 1993, 2003), as shown in (4a), or to bind a matrix pronoun c-commanded by the DP containing the relative clause (Huang 1982), as shown in (4b).Footnote 2Dou functions as a quantifier-distributor here, and has to be focus-associated with a plural or quantificational nominal expression (Lin 1998; Giannakidou and Cheng 2006; Xiang 2008; Xiang 2020, a.o.). A formal analysis of dou is discussed in Sect. 4.

-

(4)

Presence of dou inside an ORC

At first sight, the absence of scope interactions in (4) might be attributed to dou blocking reconstruction of the RC-external quantifier for scope along with the RC-head NP. However, independent evidence shows that dou does not block reconstruction.

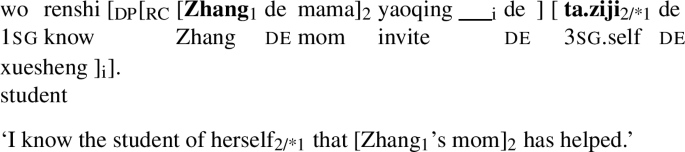

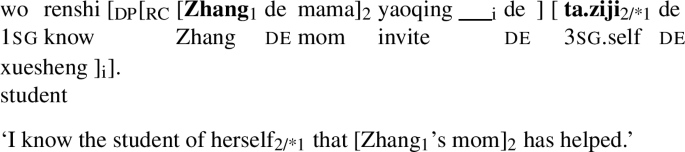

First, an anaphor in the RC-head NP can be bound by an element inside a dou-RC. As shown in the baseline (5), the RC-external anaphor ta.ziji can only be bound by an RC-internal DP c-commanding the gap, e.g., [Zhang de mama] in (5), but not by the more deeply embedded DP Zhang, despite both DPs linearly preceding the anaphor. This clarifies that reconstruction possibilities are dependent on binding rather than on linear order.

-

(5)

Anaphora binding in baseline RC:

The same binding pattern is observed in a dou-RC, as shown in (6). The anaphor tamen.ziji in the RC head can be bound by [Zhang he Li de pengyou], which c-commands the gap, but not by the more deeply embedded [Zhang he Li]. (Due to the well-known plurality requirement of dou (see detailed discussion in Sect. 4), the embedded subject DP associated with dou has to be plural, and thus the anaphor and the more deeply embedded possessor are correspondingly plural to illustrate the reconstruction effect.) (5) and (6) together suggest that reconstruction of the RC-head NP is available in Mandarin RCs and is not blocked by dou.

-

(6)

Anaphora binding in dou-RC:

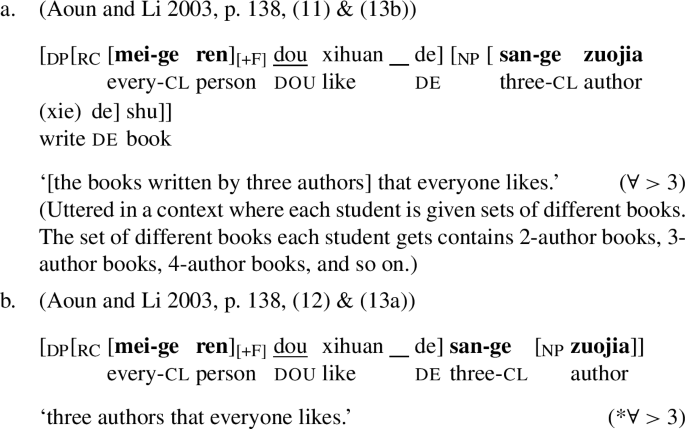

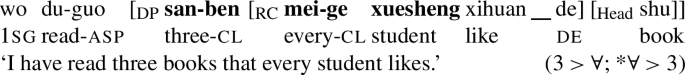

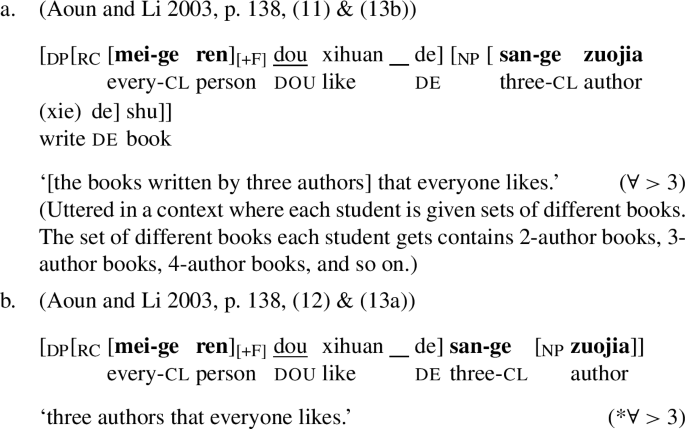

Furthermore, scope interaction is not always absent in a dou-RC. An RC-external numeral embedded in an adjectival modifier of the RC-head NP interacts with the RC-embedded subj-QP for scope, despite the presence of dou inside the relative clause, as shown in (7a), while a numeral directly quantifying the RC-head NP does not take narrow scope in the same dou-RC, as shown in (7b). With dou present in both sentences, the contrast in (7) cannot be due to dou blocking reconstruction for scope, but rather lies in the difference between an adjectival modifier and a directly quantifying numeral.

-

(7)

Following Aoun and Li (2003), I argue that an adjectival modifier can reconstruct along with the RC-head NP for scope in Mandarin, while a numeral quantifier cannot, because an adjectival modifier is part of the RC-head NP but a numeral quantifier is not. Independent evidence for the distinction between an adjectival modifier and a numeral with respect to their ability to reconstruct with the RC head is shown below, following an observation about English modified RC-head NPs in Bhatt 2002. Therefore, the availability of scope ambiguity in the dou-RC in (7a) suggests that dou does not block reconstruction for scope.

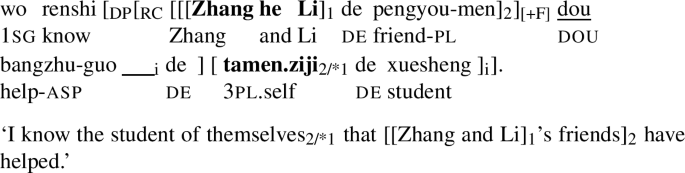

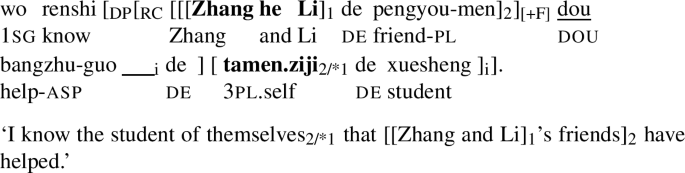

Bhatt (2002, 2006) has shown that adjectival modifiers of an RC-head NP, including adjectives like first and longest, numerals, and quantificational adjectives like few, all exhibit ambiguity between a high reading and a low reading, derived from reconstruction of the RC-head, but only when they are preceded by a definite determiner, as shown in (8). Bhatt (2002) attributes the contrast to the fact that numerals and quantificational adjectives in English are ambiguous between adjectival modifiers and determiners, depending on the presence of a definite determiner, and only NPs, but not DPs, reconstruct back into RCs. In the presence of a determiner in (8a), the numeral is an adjectival modifier, which is part of the RC-head NP, and can reconstruct back into the relative clause. In the absence of an overt definite determiner, the numeral in (8b) is no longer part of the RC-head NP, but rather is base-generated in the D head, and thus cannot reconstruct to derive the low reading.

-

(8)

((52) and (54) in Bhatt 2002)

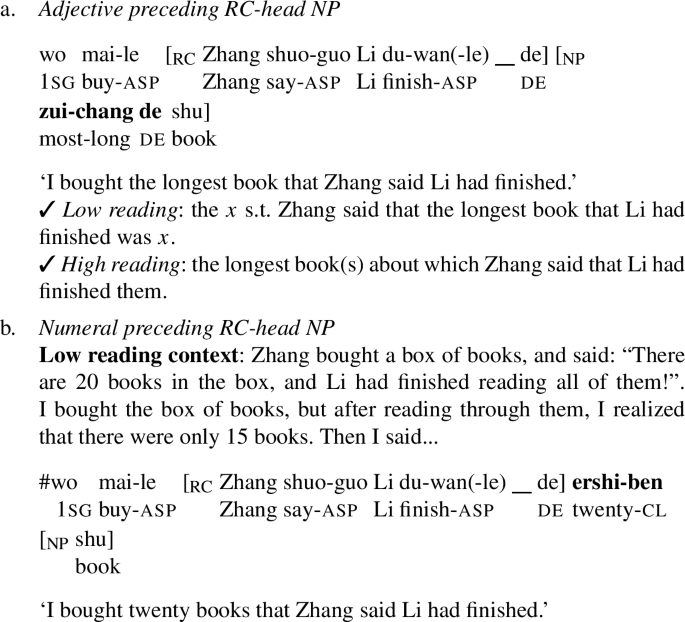

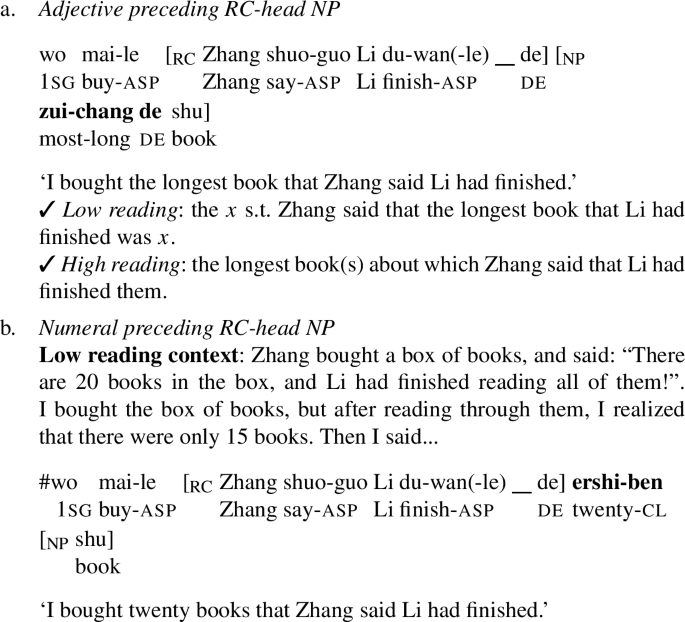

Similarly, a Mandarin adjectival modifier of an RC-head NP receives a low reading like its English counterpart, as shown in (9a), but a numeral directly quantifying the RC-head NP does not, as shown by the infelicity of (9b) in a context that forces the low reading. Hence, in Mandarin, only an adjective preceding an RC-head NP, but not a numeral directly quantifying the RC-head NP, can reconstruct with the RC-head back into the relative clause to take a narrower scope.

-

(9)

The contrast between adjectives and numerals can be attributed to numerals in Mandarin, unlike Mandarin adjectives or their counterparts in English, not being part of the NP, but rather being base-generated in a projection higher than NP. This argument is in line with the DP structure shown in (10), which has been independently argued for in previous literature (Tang 1990, Li 1998, 1999, Aoun and Li 2003, Huang et al. 2009, a.o.).

-

(10)

I adopt this structure for Mandarin nominal expressions henceforth, but collapse all projections above NP into the DP layer and depict a numeral including its classifier as the D head for simplicity, though of course the following analysis works just as well if a full-fledged DP structure is assumed.

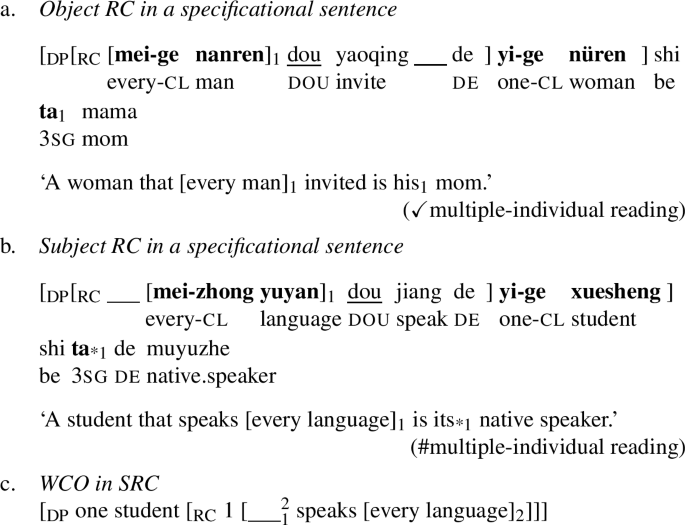

Having established that dou does not block reconstruction of the RC-head, I argue that a reconstruction-based approach to scope interaction in Mandarin RCs could not capture dou’s blocking effect we saw in (4), where the presence of dou blocks the wide-scope reading and matrix pronoun binding of an RC-internal QP; instead, the solution to the puzzle follows directly from the long QR analysis to be proposed in Sect. 3, as shown in detail in Sect. 4. We now introduce a complication: the blocking effect of dou depends on the type of the matrix clause, which is not directly handled by a reconstruction-based approach, either.

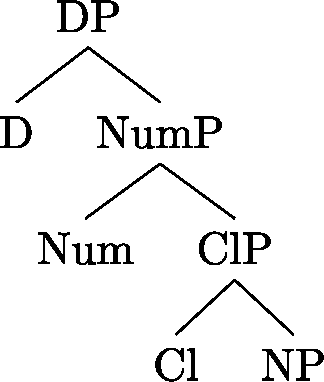

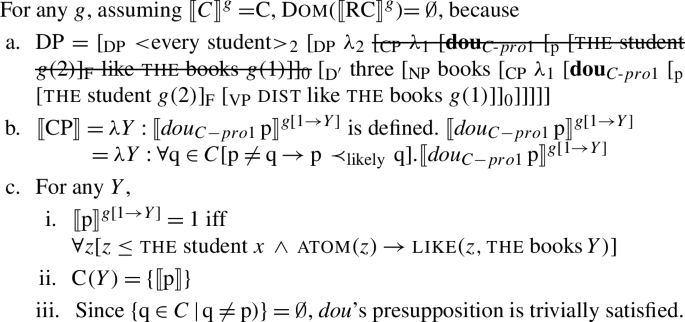

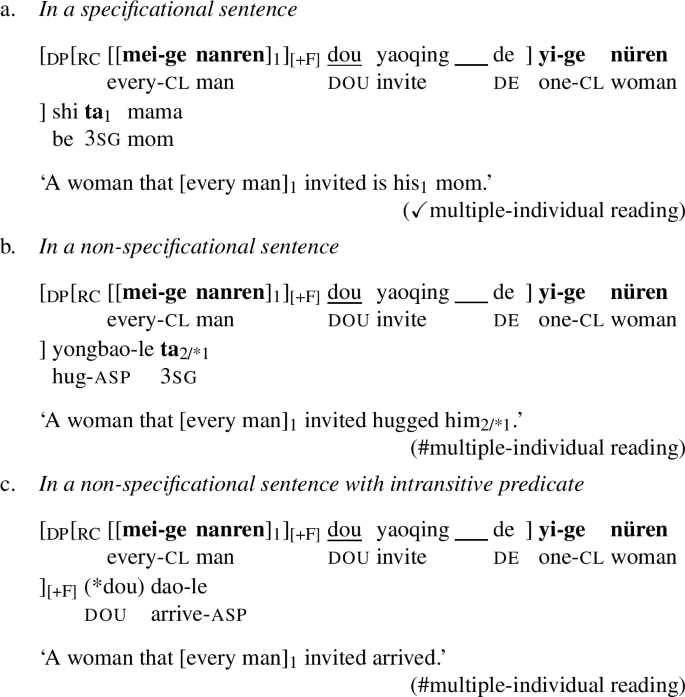

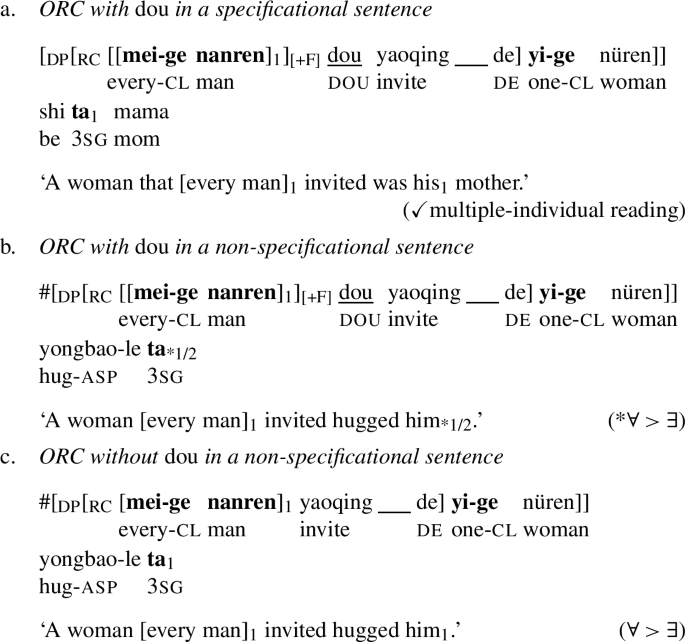

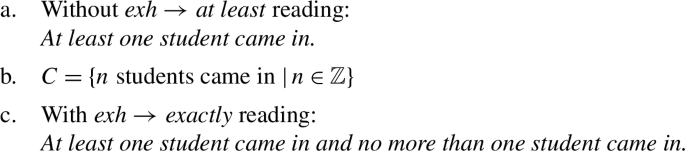

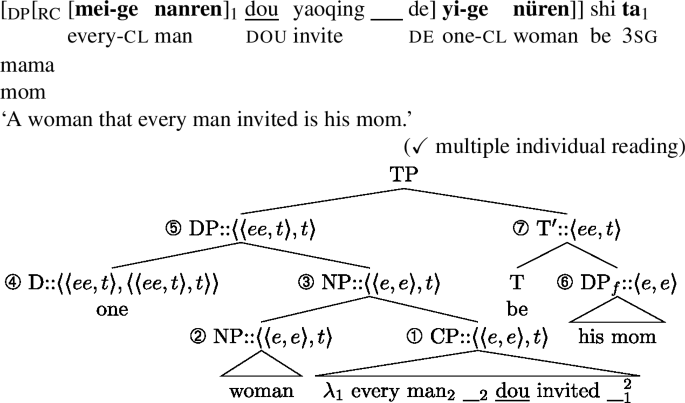

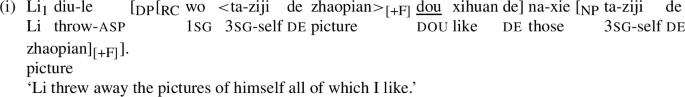

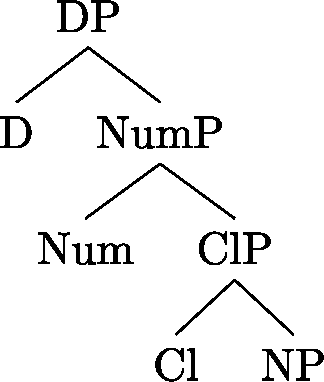

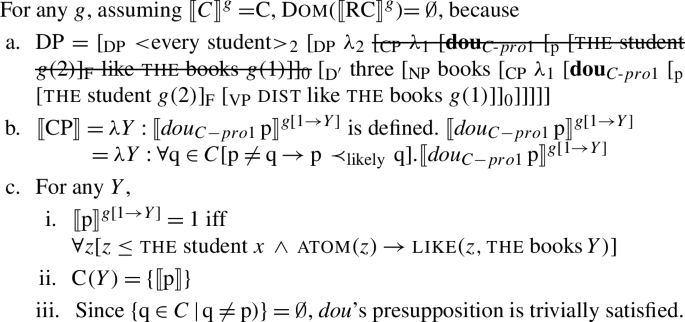

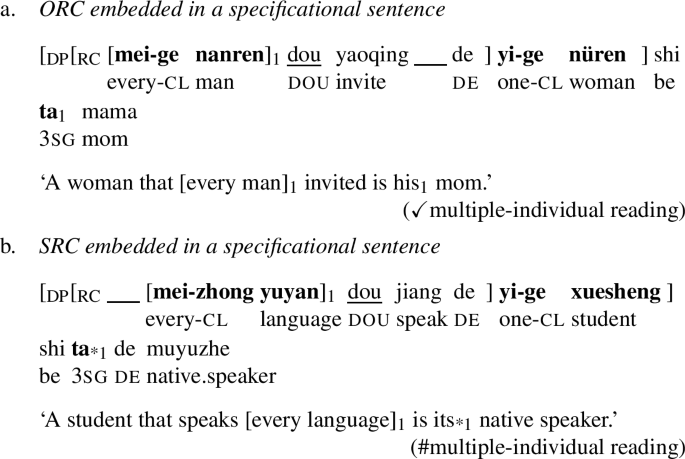

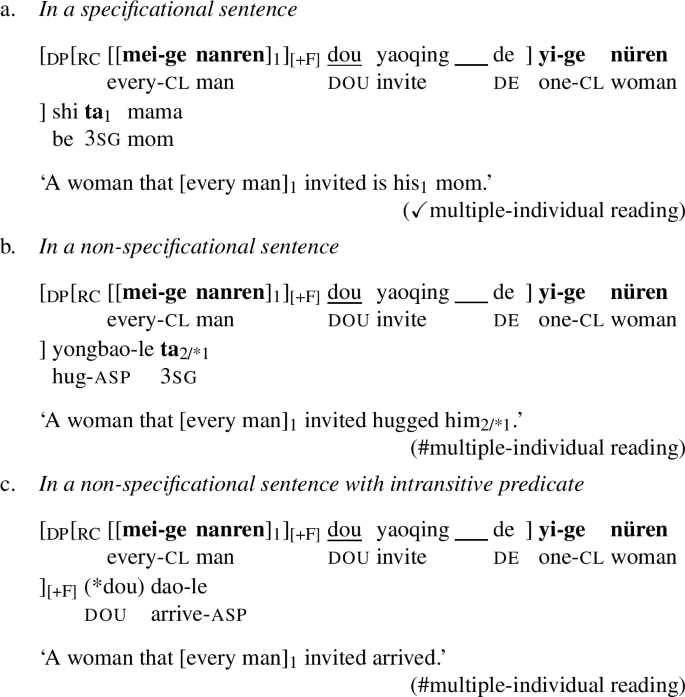

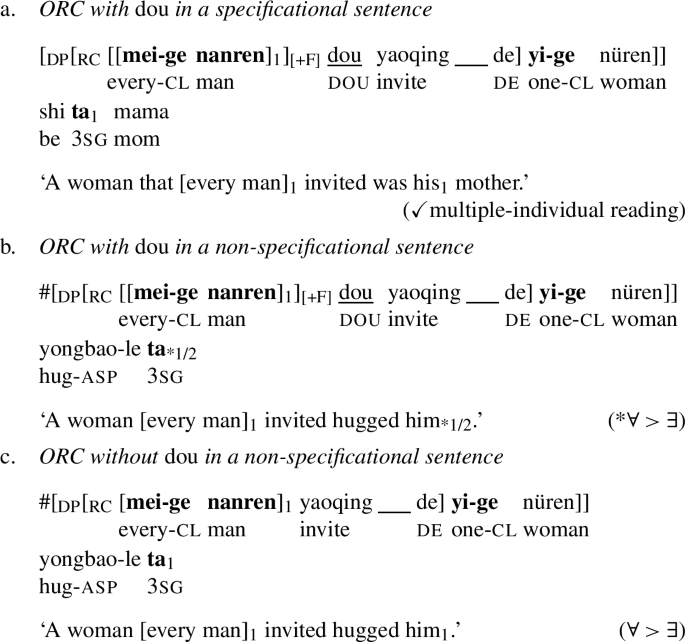

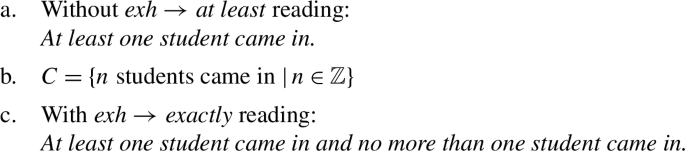

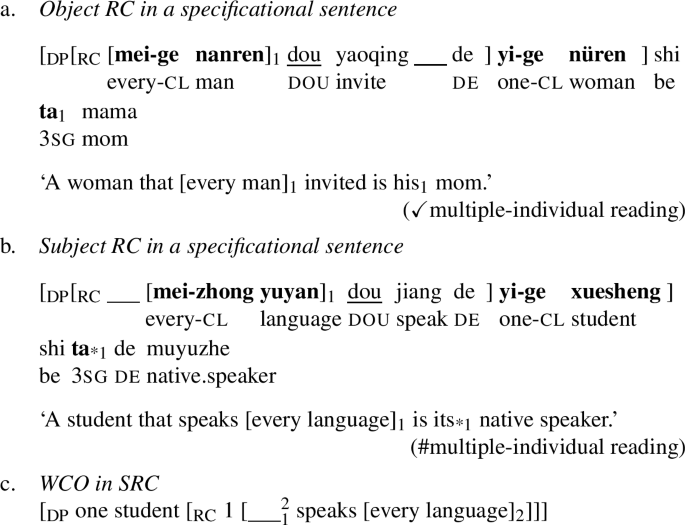

When a dou-ORC is embedded in a specificational-copula sentence, as shown in (11a), a pronoun c-commanded by the RC-containing DP may covary with the RC-embedded subj-QP. In other words, the containing DP admits a multiple-individual reading despite being quantified by yi-ge ‘one’: for every man x, x invited one or more women and among the women that x invited, there must be a woman who is x’s mom. However, a dou-SRC embedded in the same specificational sentence, as shown in (11b), does not admit the multiple-individual reading.Footnote 3 The only available interpretation for (11b) is that there is only one student who speaks every language and the student is a native speaker of a (possibly different) language salient in the context.

-

(11)

The multiple-individual reading of an RC-embedded subj-QP in an ORC containing dou embedded in a specificational sentence seems to be at odds with the absence of scope effects in dou-RCs embedded in non-specificational sentences. However, as discussed in Sect. 5, while the multiple-individual reading has a similar effect as the wide-scope reading of RC-embedded QP, it is not a consequence of scope taking, but rather results from a natural-function interpretation of the relative clause.

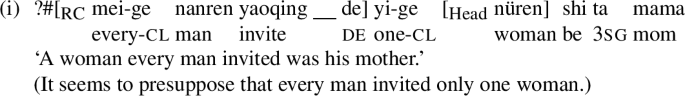

2.2 Restriction on scope interaction in SRCs

So far we have considered ORCs. Turning now to subject relative clauses (SRCs), we see that some Mandarin SRCs admit the wide-scope reading and matrix-pronoun binding of the RC-embedded object QP (obj-QP) (Huang 1982, Larson and Wu 2018). However, I observe that not all Mandarin SRCs exhibit these scopal effects. This section discusses restrictions on scope interaction in Mandarin SRCs related to the presence of aspectual marking.

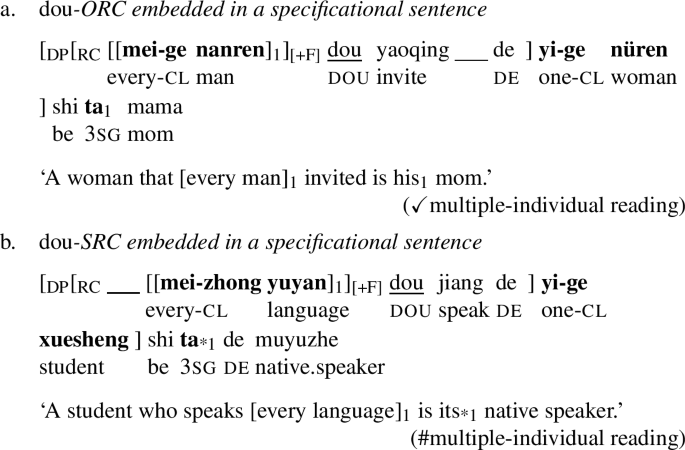

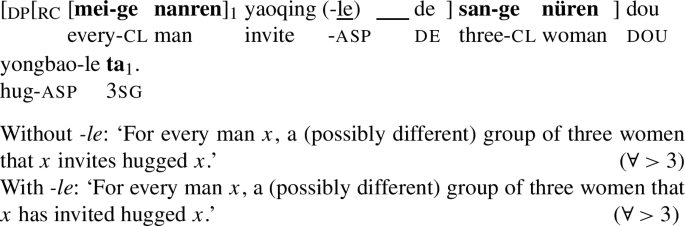

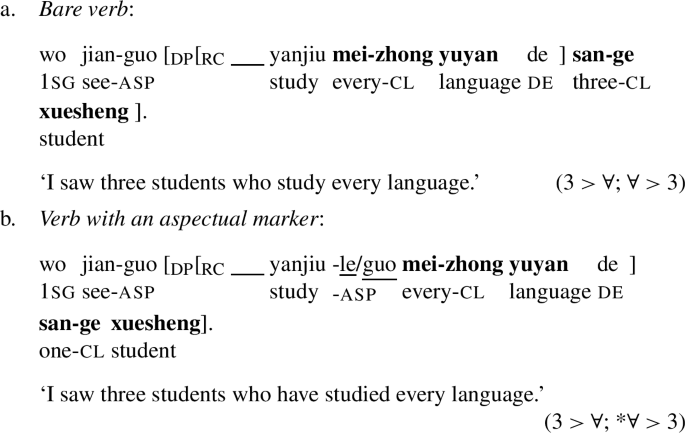

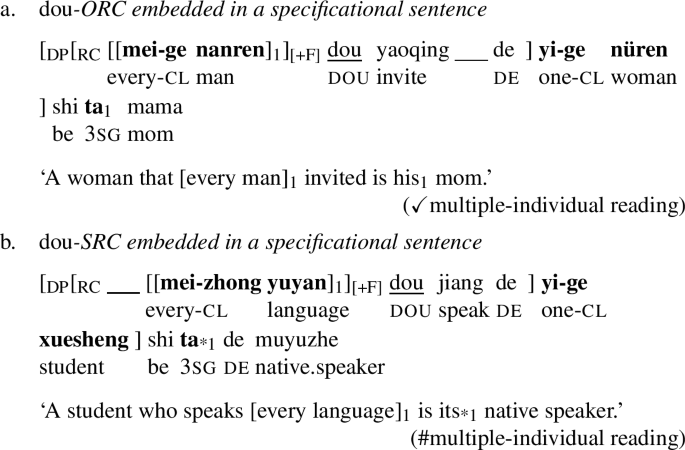

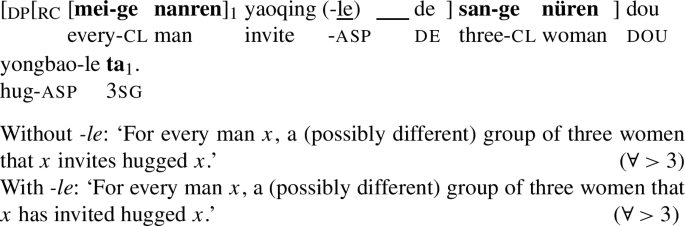

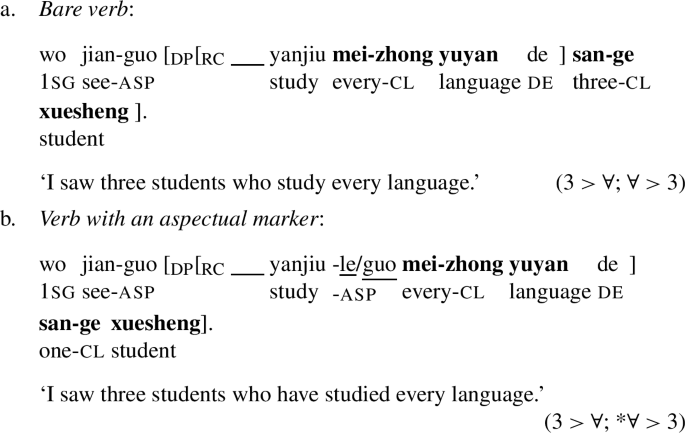

Scope ambiguity and matrix-pronoun binding are observed in an SRC containing a bare verb, as shown in (12a), but not when the embedded verb contains an aspectual marker, as shown in (12b).Footnote 4

-

(12)

Scope ambiguity and matrix-pronoun binding in SRCs

The same asymmetry with respect to the verb form is not observed in ORCs. Regardless of the form of the RC-embedded verb, an RC-embedded subj-QP in an ORC is always able to take wide scope over an RC-external QP and bind a matrix pronoun, as shown in (13).

-

(13)

Scope ambiguity and matrix-pronoun binding in ORCs

The contrast with respect to verb forms poses another challenge to a reconstruction-based approach for scope ambiguity across RC boundaries. For example, Larson and Wu (2018) propose that the scope ambiguity in SRCs is derived from reconstructing the RC-external quantifier along with the RC-head noun. They assume that prenominal relative clauses are truncated to TPs, as shown in (14); thus, subjects always stay in [Spec, TP], like those in English simple transitive clauses, instead of moving into a topic position higher than TP, as in Mandarin simple transitive clauses. Scope interaction in Mandarin RCs is thus comparable to scope interaction between the subject and the object QPs in English simple transitives. In a Mandarin SRC, the RC-embedded obj-QP can then undergo QR over the reconstructed subj-QP, as shown in (14).

-

(14)

Mandarin relative clauses:

Larson and Wu (2018) do not discuss the contrast with respect to the RC-embedded verb form observed in (12). Since the analysis predicts that scope interaction between subj-QP and obj-QP is always available in Mandarin SRCs, regardless of the presence of aspectual markers inside the RC, it is unclear how the contrast could directly follow from the current shape of the analysis.Footnote 5 I suggest therefore that reconstruction for scope is not sufficient to account for the variation in scope effects with respect to the presence of aspect in Mandarin SRCs.

2.3 Interim summary

The two sets of data discussed in this section show that scope interaction across Mandarin ORCs are not available across the board: they are generally not available in dou-RCs or in SRCs with aspectual marking. The pattern of scope interactions in Mandarin relative clauses is summarized in Table 1.

As also discussed in this section, these patterns are unexpected under an analysis based on reconstruction for scope. In Sect. 3, I propose a long QR analysis to derive the scope interactions in the baseline ORCs, where I argue that the subj-QP of an ORC undergoes long QR out of the RC to [Spec, DP].

3 Long QR in ORCs

This section proposes a long QR analysis for scope interaction in Mandarin RCs: the RC-embedded QP undergoes QR to the edge of the containing DP, where it can take wide scope over the RC-external quantifier and bind a matrix pronoun. Section 3.1 introduces syntactic and semantic conditions which have been shown to constrain QR. Section 3.2 shows that long QR out of Mandarin prenominal pre-D(eterminer) ORCs is possible, obeying the syntactic and semantic conditions. Section 3.3 derives the scope ambiguity and binding out of the containing DP in detail, following the mechanism proposed for inverse linking in Büring (2004). Scope interactions in Mandarin SRCs are discussed in Sect. 6.

3.1 Syntactic and semantic constraints on QR

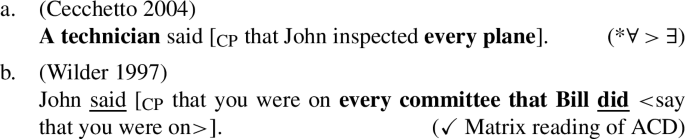

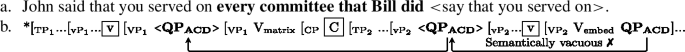

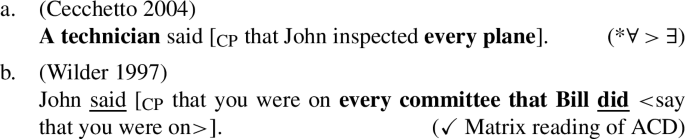

QR generally exhibits clause-boundedness, as shown in (15a) (Fodor and Sag 1982; Fox 1995, 2000, a.o.), where the embedded QP every plane in unable to scope over the matrix QP a technician. However, exceptional QR crossing finite clause boundaries seems to be licensed in some circumstances. For example, the matrix reading of the antecedent-contained deletion (ACD) construction in (15b), where the elided VP takes the matrix VP as its antecedent, requires the embedded QP including the ACD site to undergo QR over the matrix verb, which crosses a finite clause boundary (Fox 2002, Wilder 2003, Cecchetto 2004).

-

(15)

To account for clause-boundedness as well as its exceptions, Fox (2002) and Cecchetto (2004), among others, propose that QR obeys both a syntactic constraint on movement, i.e., the Phase Impenetrability Condition (PIC) (Chomsky 2000, 2001), and a semantic constraint, i.e., Scope Economy (Fox 1995, 2000).

In the spirit of the PIC as assumed in Cecchetto (2004), where vP and CP are phases and a single step of movement cannot cross two or more phase heads, I adopt a version of the PIC modified from the classical one (Chomsky 2000, 2001), as defined in (16);Footnote 6 I also adopt the strong version of Scope Economy, following Fox (1995, 2000). As defined in (17), it requires each step of QR to be independently motivated. In other words, each step of QR has to be semantically non-vacuous, such as by creating a new scope relation, but not by simply facilitating a further step of QR.Footnote 7

-

(16)

The (Weak) Phase Impenetrability Condition

The complement of a phase α is not accessible to operations when α occurs in the complement of a higher phase β.

-

(17)

(Strong) Scope Economy

In successive-cyclic QR, each step needs a motivation other than allowing further movement of the QP.

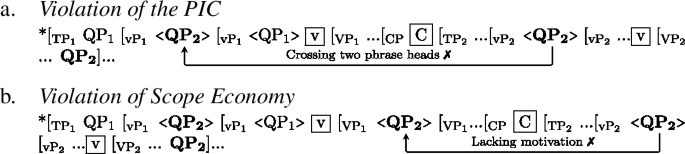

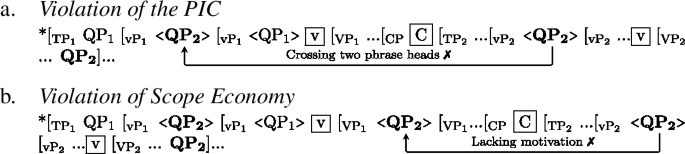

The two constraints account for the clause-boundedness of QR.Footnote 8 Take (15a) as an example. As shown in (18), the step of QR from [Spec, vP1] to [Spec, vP2] violates the PIC by crossing two phase heads, as shown in (18a). It is not alternatively possible for QP2 to undergo successive-cyclic QR to [Spec, vP1], since facilitating further QR is not an independent motivation for the step from [Spec, vP2] to [Spec, VP1], as shown in (18b).Footnote 9

-

(18)

✗ Long QR in (15a):

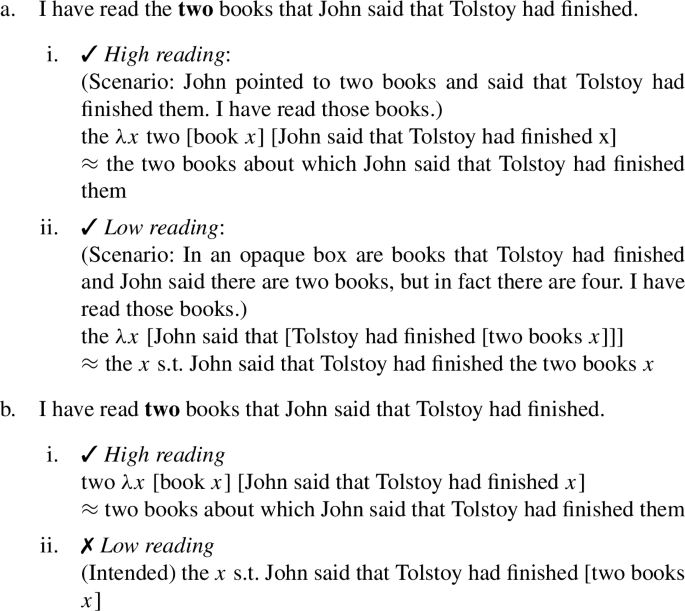

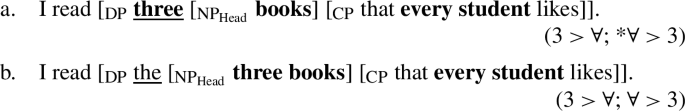

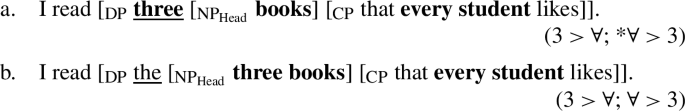

Applying these ideas now to RCs in English, recall that scope ambiguity in English RCs varies according to whether the RC-external numeral is a determiner, like in (19a), or in a lower position, like in (19b). We saw in Sect. 2.1 that the scope alternation in (19b) can be accounted for via reconstruction of RC-external numeral along with the head NP, while the absence of it in (19a) is due to the numeral in the determiner position being unable to reconstruct.

-

(19)

If long QR of the embedded QP out of the English RC were available, we should expect (19a) to show scope alternation as well, contrary to fact. I now show that the analysis correctly derives the impossibility of long QR in English RCs.

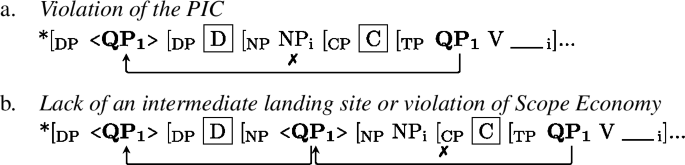

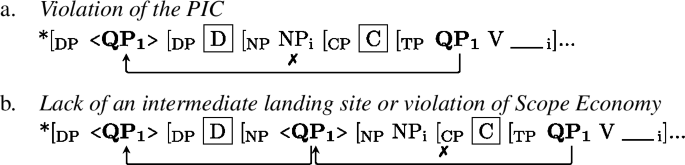

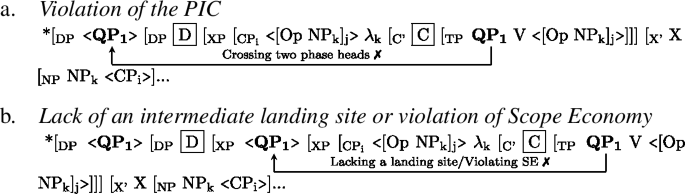

One-step QR would violate the PIC by crossing two phase heads, as shown in (20a), while two-step QR is not available either, due either to the lack of an intermediate landing site or to violation of Scope Economy. Assuming that QR does not target CP (Cecchetto and Chierchia 1999, Cecchetto 2004), the embedded QP needs to undergo QR to a position between the RC-head noun and the D head, but it is widely assumed that NPs lack specifiers (Bošković 2014, Sichel 2018, a.o.). Furthermore, this step of QR is also semantically vacuous, violating Scope Economy.

-

(20)

✗ Long QR out of postnominal ORC (19a)

[DP three books [RC that every student likes]]

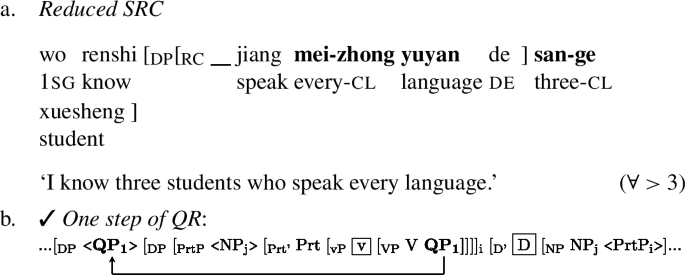

The next subsection applies the idea that QR as covert movement obeys both the PIC and Scope Economy to Mandarin relative clauses. I argue that long QR out of a prenominal, pre-D ORC does not violate either condition, and thus can unexceptionally derive the “exceptional” scope effects.

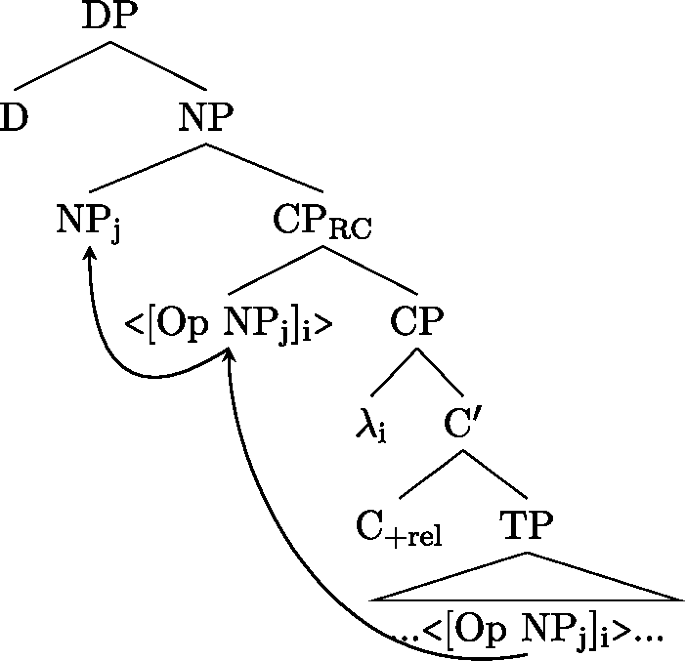

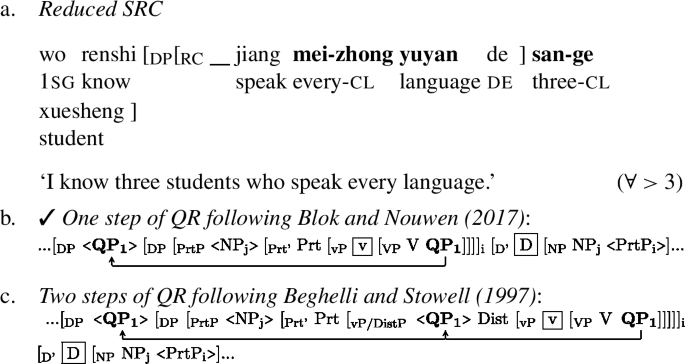

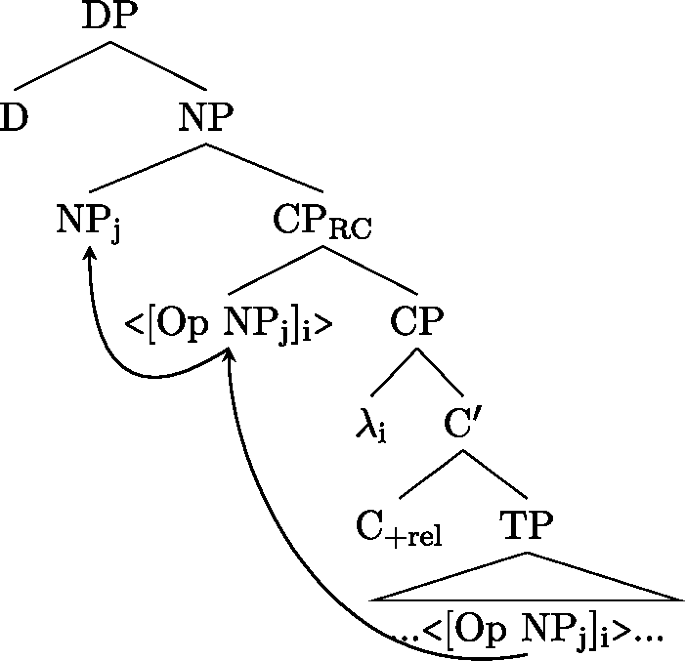

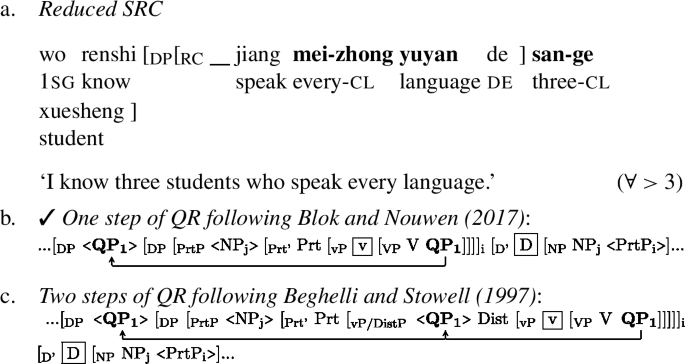

3.2 Long QR out of prenominal ORCs

Before introducing the proposed analysis for the observed scope effects in Mandarin RCs, I first lay out the derivation and interpretation of Mandarin prenominal pre-D RCs. Aoun and Li (2003) have shown that a Head Raising analysis (Brame 1968, Schachter 1973, Vergnaud 1974, Kayne 1994, Bianchi 1999, Bhatt 2002, a.o.) is available in Mandarin RCs. As we saw in (3), the scope effects can co-occur with reconstruction of the RC-head NP, which is suggestive of a Head Raising analysis. I therefore adopt Head Raising in this paper.Footnote 10 Specifically, I adopt the version of Head Raising proposed in Bhatt (2002), and following De Vries (2002), I assume that prenominal RCs in an SVO language are base-generated postnominally. Therefore, the RC-head NP raises out of the relative CP after moving with the relative operator to [Spec, CP] from its base position and projects NP, as shown in (21) with unpronounced copies in angle brackets. One and only one of the copies is interpreted, and the uninterpreted copies are deleted at LF (Bhatt 2002, Sportiche 2016). I further assume that when a copy is deleted, the λ abstraction created by the movement, i.e., λi in (21), may be retained (Bhatt 2002, p. 64).

-

(21)

Step 1: RC-head raising

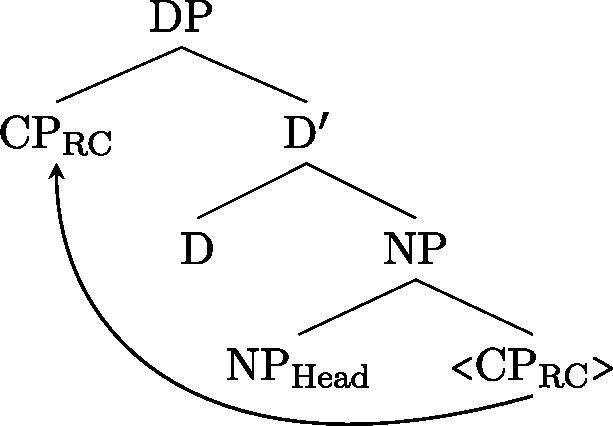

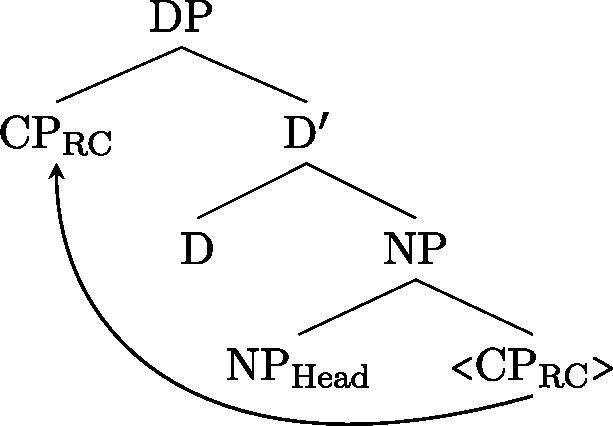

Then, the prenominal pre-D word order of Mandarin RCs is derived from moving the relative CP into a prenominal position, specifically [Spec, DP] (De Vries 2002).Footnote 11 This step of movement is shown in (22), where the unpronounced CP copy is in angle brackets and the internal structure of the RC is omitted for clearer visualization.

-

(22)

Step 2: Deriving the prenominal word order

For interpretation of the RC, I assume that the relative CP undergoes syntactic reconstruction back to its postnominal base position at LF.Footnote 12 Further supposing that the lowest copy of the RC-head gets interpreted, we finally obtain the structure shown in (23), where the uninterpreted copies are struck out and the unpronounced ones are in angle brackets.

-

(23)

Step 3: Interpreting the lowest copies of CPRC and RC-head

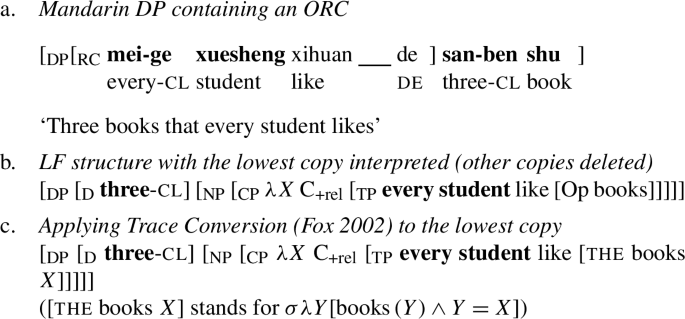

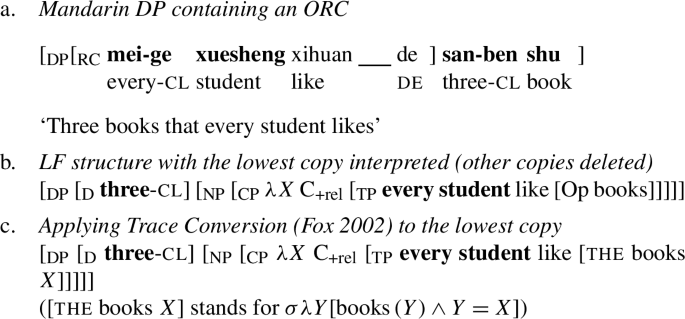

Take the Mandarin ORC in (24a) as an example. It correponds to an LF shown in (24b), with the uninterpreted copies of the relative CP and RC-head deleted. The lowest copy of the RC-head is interpreted via Trace Conversion (Fox 2002), as shown in (24c), where capital letters X and Y are for variables of plurality and σ is the plural counterpart of the ι-operator.

-

(24)

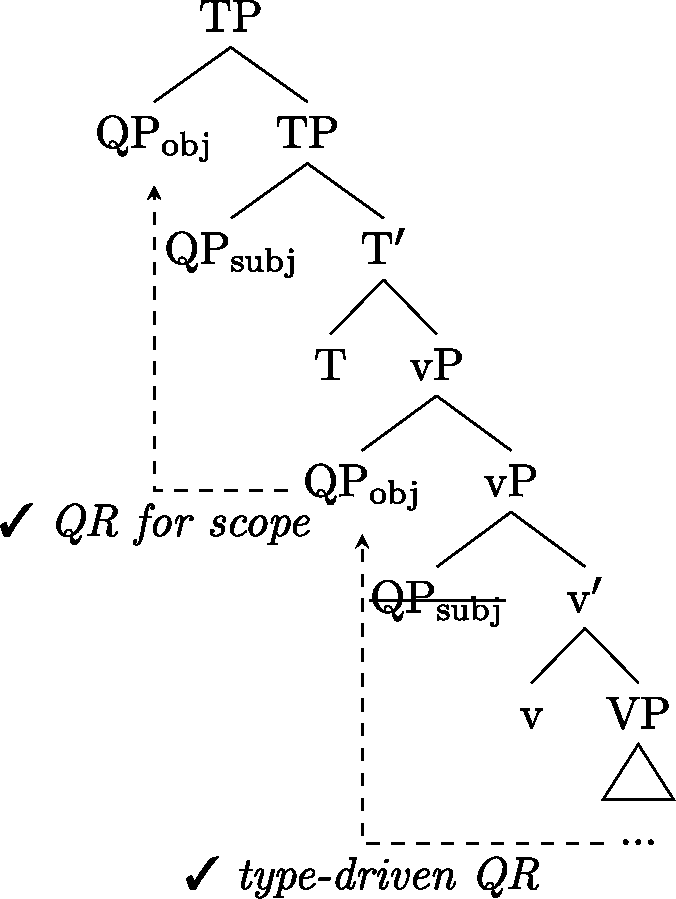

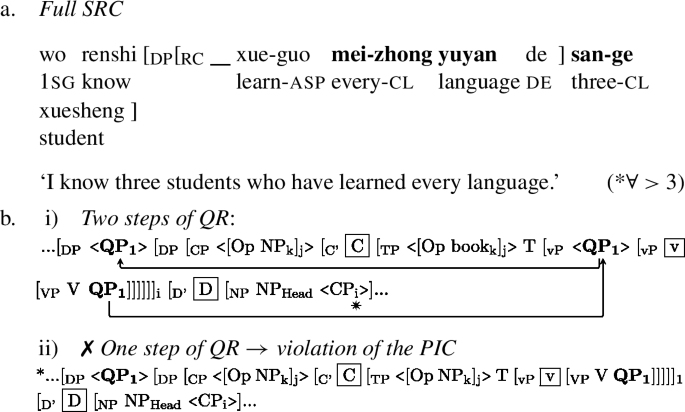

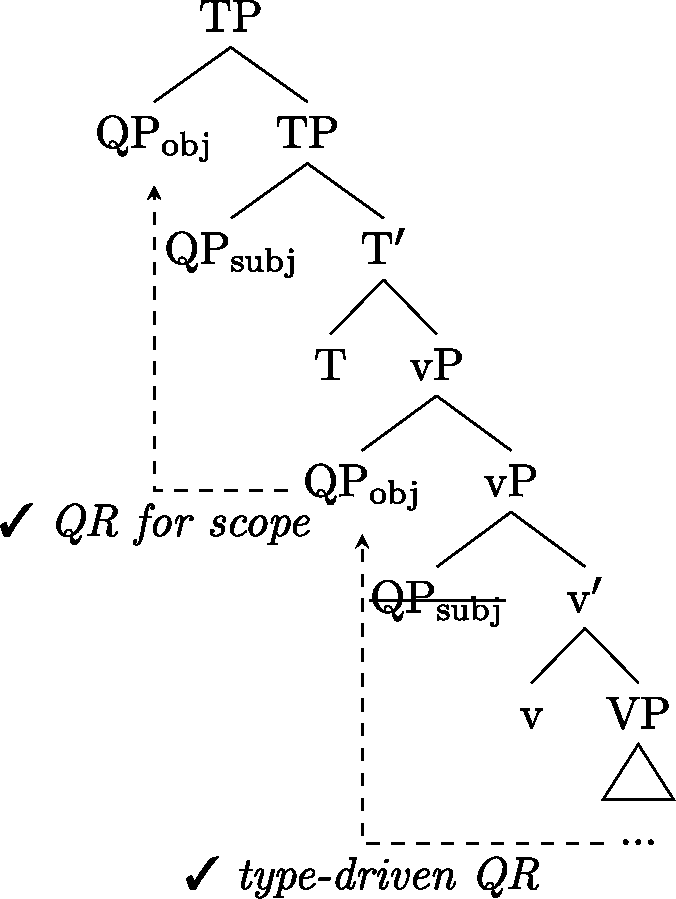

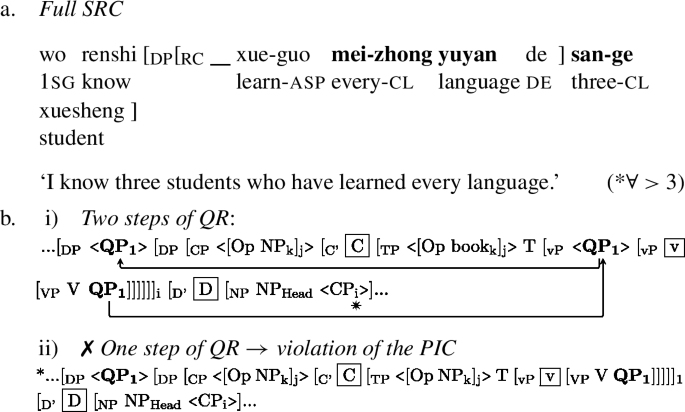

I now show that QR out of an ORC in Mandarin obeys both the syntactic and semantic constraints on QR, due to its pre-D position. I assume, following prior work, that the relevant phases in the structure above are DP, CP, and vP (see Bošković 2014, Citko 2014, Aravind 2021, a.o.). I further assume that QR as a process occurring at LF is freely ordered with reconstruction, so that it happens before the syntactic reconstruction of the relative CP (see, e.g., Romero 1998, pp. 104–105 for a similar procedure with QR occurring before reconstruction).

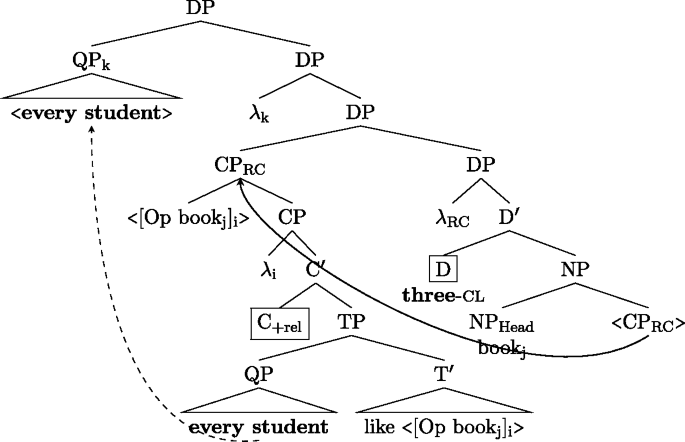

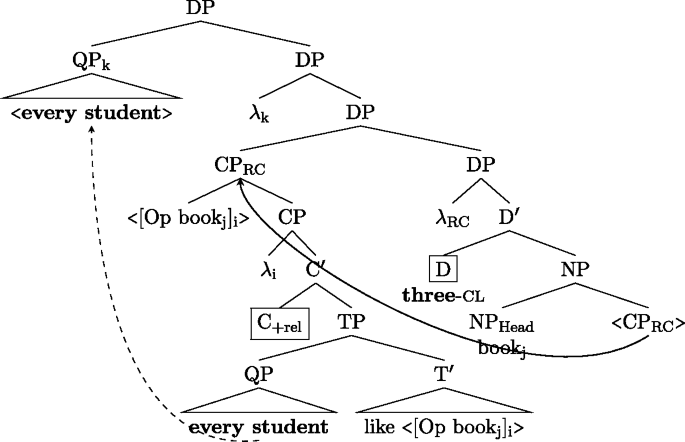

Then, as shown in (25) for (24a), since the relative CP moves to the edge of the DP and thus to a position higher than the phase head D, i.e., the boxed RC-external quantifier three-cl, the step of QR, as indicated by the dashed arrow in (25), crosses only one phase head, obeying the PIC. It also obeys Scope Economy by creating a new scope relation, since the RC-embedded subj-QP can now be interpreted at a position c-commanding the RC-external quantifier and takes wide scope.

-

(25)

✓ Long QR out of prenominal ORCs

Since it is the pre-D position that the ORC moves into that facilitates the apparently “long” QR, this analysis predicts that long QR out of an ORC in a post-D position, with all the other conditions being the same, would violate the constraints on QR. The prediction is correctly borne out in English ORCs, discussed in Sect. 3.1 above. We now see that it is borne out in Mandarin prenominal post-D ORCs.

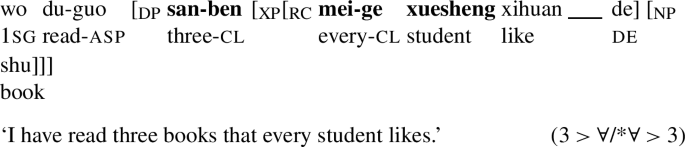

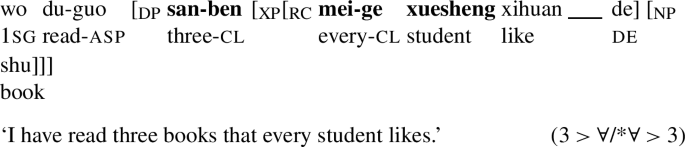

Mandarin relative clauses are all prenominal, but can either precede or follow demonstratives and numerals, which are referred to as pre-D RCs and post-D RCs, respectively. It has been observed that Mandarin post-D ORCs do not show scope ambiguity, as shown in (26) (Huang 1982, Aoun and Li 1993, a.o.).

-

(26)

Mandarin post-D RC

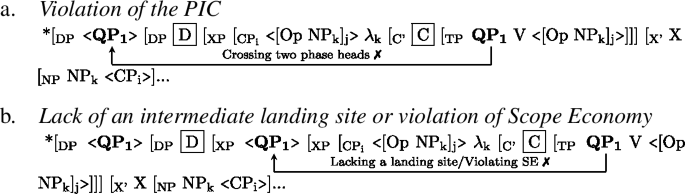

I assume that a post-D RC moves from its postnominal base position to [Spec, XP], a position between D and N, following De Vries (2002). Since the moved relative CP is still within the DP phase, QR of the RC-embedded QP in one step to [Spec, DP] would cross two phase heads ( and

and  ), as shown in (27a), which violates the PIC. However, two-step QR is not available either, as shown in (27b). Either an intermediate landing site is unavailable, if we assume that the functional projection XP between D and N only has one specifier position, or the first step of QR is semantically vacuous, violating Scope Economy.

), as shown in (27a), which violates the PIC. However, two-step QR is not available either, as shown in (27b). Either an intermediate landing site is unavailable, if we assume that the functional projection XP between D and N only has one specifier position, or the first step of QR is semantically vacuous, violating Scope Economy.

-

(27)

✗ Long QR out of prenominal post-D ORCs

To summarize, this subsection has shown that long QR out of a Mandarin prenominal pre-D ORC obeys both the PIC and Scope Economy, two constraints on QR, and thus is in fact not “exceptional”. Detailed derivation of the RC-embedded QP’s wide-scope reading and matrix-pronoun binding is shown in the next subsection.

3.3 Deriving the exceptional-scope effects

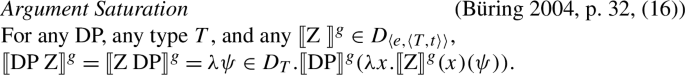

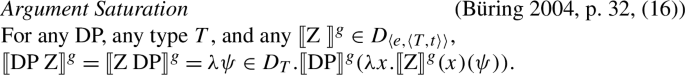

Büring (2004) proposes a type-shifting rule, Argument Saturation (28), for QR in inverse linking and possessive constructions. The same rule will be adopted for long QR out of an ORC, to allow the QRed subj-QP to compose with the rest of the DP at [Spec, DP].

-

(28)

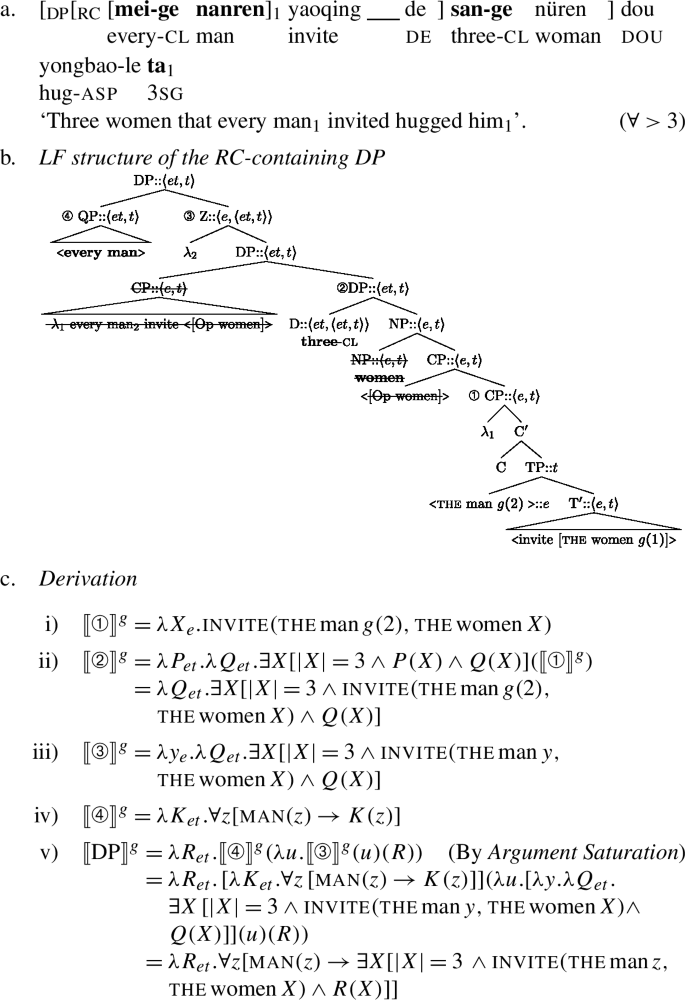

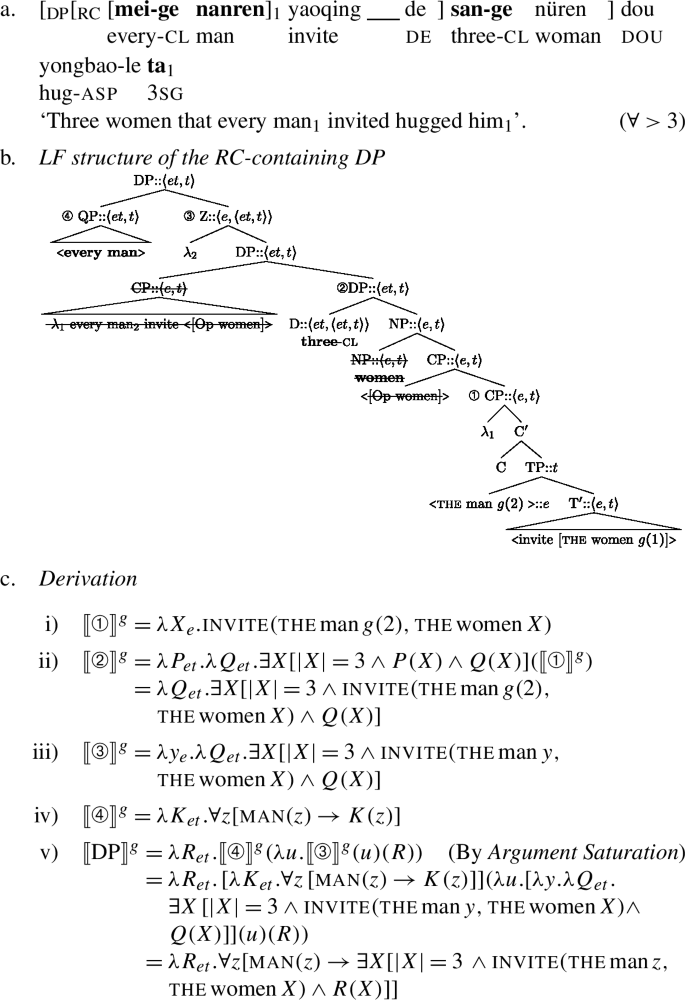

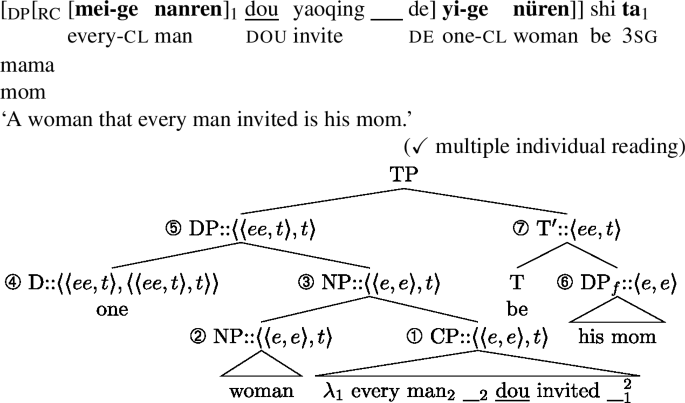

Take (29a) as an example, where the RC-embedded subj-QP takes wide scope and binds a matrix pronoun. The structure of the DP containing the relative clause is shown in (29b), where the unpronounced copies are in angle brackets and uninterpreted copies are struck out. Having undergone QR to [Spec, DP], the subj-QP (➃) c-commands the RC-external numeral. Recall that the fronted relative CP undergoes syntactic reconstruction back to its postnominal base position, and suppose here that under a Head Raising analysis of the RC, the lowest copy of the RC-head NP is interpreted. Since the RC-head NP is plural, the lowest copy is interpreted as “the plurality X of women”.Footnote 13 Node ➀ is composed via Predicate Abstraction (Heim and Kratzer 1998), as is node ➂. The QRed subj-QP (➃) composes with the rest of the DP (➂) via Argument Saturation, as shown in (29c-v).Footnote 14

-

(29)

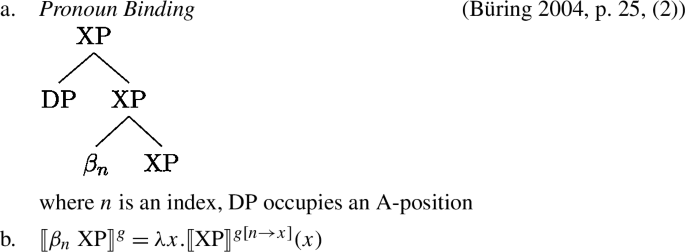

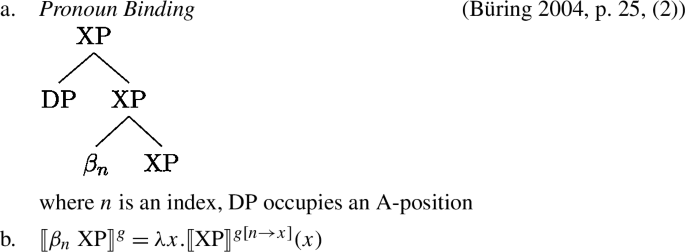

Despite being interpreted at the edge of DP, the RC-embedded subj-QP still does not directly c-command the matrix pronoun at LF. To derive matrix-pronoun binding, I adopt the β-operator for pronoun binding proposed in Büring (2004), as defined in (30).

-

(30)

The matrix pronoun is then analyzed as an E-type pronoun (Evans 1980, Heim 1990, Cooper 1997, Chierchia 1995, Heim and Kratzer 1998, a.o.). Specifically, the pronoun consists of a definite article the and a predicate containing two variables: a 2-place relation \(R_{\langle e, \langle e, t\rangle \rangle}\) supplied by the context, and a variable \(x_{e}\) bound by the β-operator.

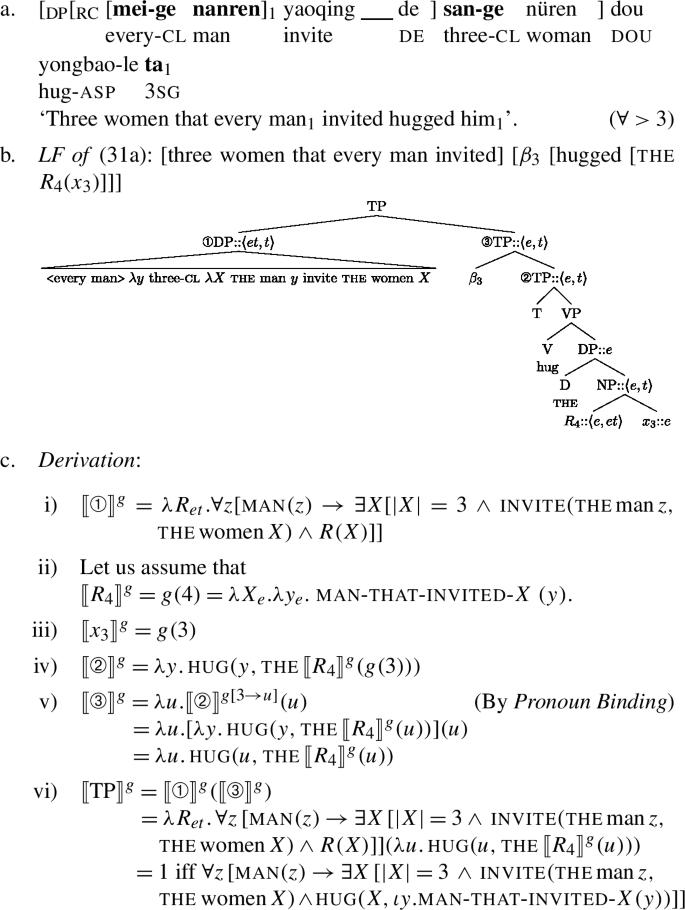

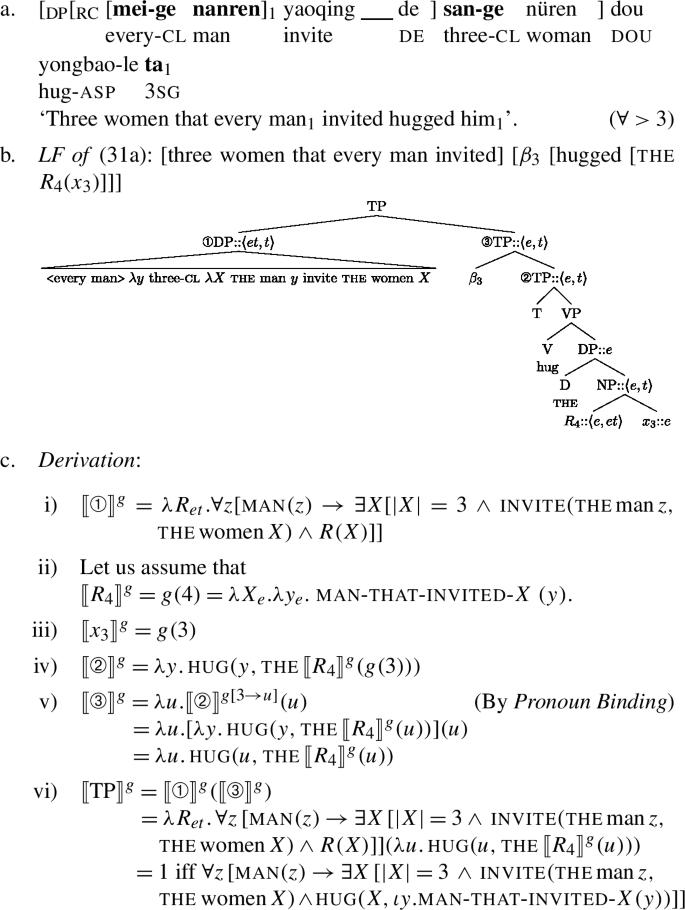

Sentence (29a), repeated below as (31a), therefore has the LF shown in (31b). The contextually supplied two-place relation \(R_{4}\) taken by the definite article the receives the interpretation in (31c-ii), and its argument \(x_{3}\) is bound by \(\beta _{3}\). Then after the step-by-step derivation, we get the intended truth conditions shown in (31c-vi).

-

(31)

To summarize, the derivations in (29) and (31) show that the RC-embedded subj-QP in a Mandarin pre-D ORC takes wide scope and binds out of the containing DP at [Spec, DP] after undergoing long QR. The next section shows in detail that the proposed long QR analysis, accompanied with the analysis of dou in Xiang (2020), can easily account for the absence of the scope interactions when dou is present in an ORC (dou-RC).

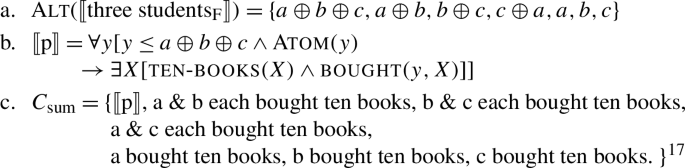

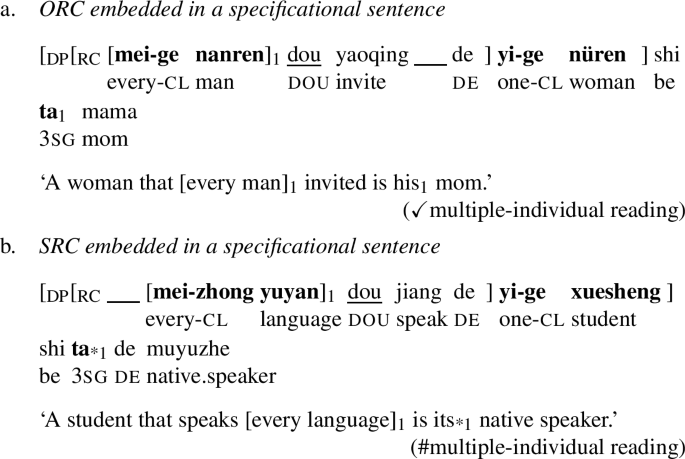

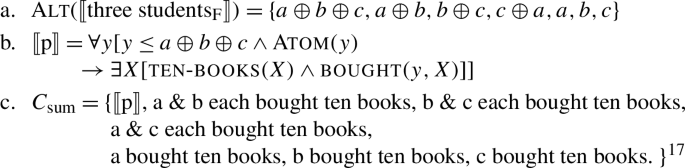

4 The blocking effect of dou

This section provides an account for the blocking effect of dou presented in Sect. 2.1, where the RC-embedded subj-QP is no longer able to take wide scope or bind a matrix pronoun when dou is present in the relative clause.

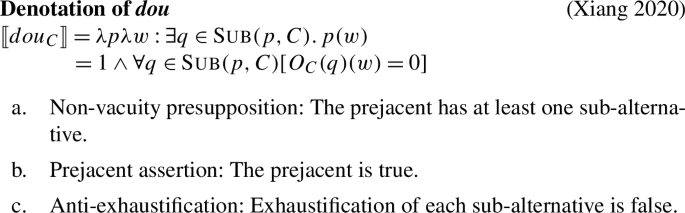

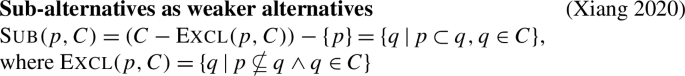

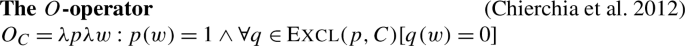

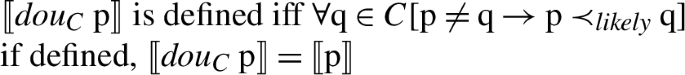

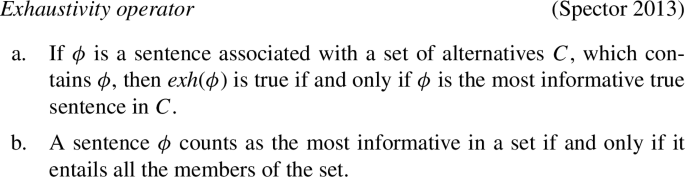

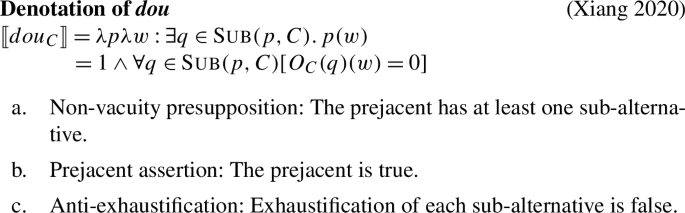

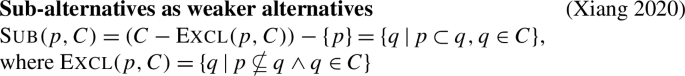

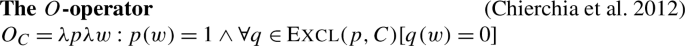

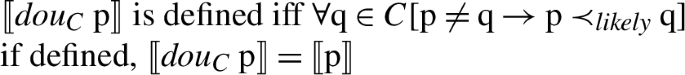

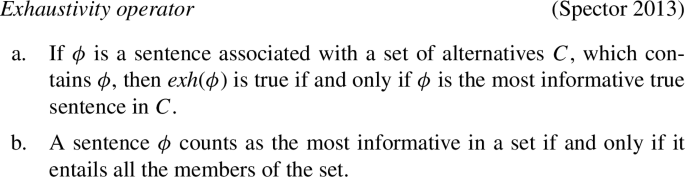

The particle dou in Mandarin is well-known for its multiple functions: it can be used as a quantifier-distributor, a free-choice item licensor, and a scalar operator (Lin 1998, Giannakidou and Cheng 2006, Xiang 2008; Xiang 2020, a.o.). Xiang (2020) proposes a unified analysis of dou as a focus-sensitive exhaustifier on analogy to only, as shown in (32). Like only, dou presupposes that the prejacent clause has at least one sub-alternative, i.e., a weaker alternative asymmetrically entailed by the prejacent clause, as defined in (33). Dou then asserts that (i) the prejacent clause is true, and (ii) the exhaustification of each sub-alternative, achieved by the O-operator defined in (34), is false.

-

(32)

-

(33)

-

(34)

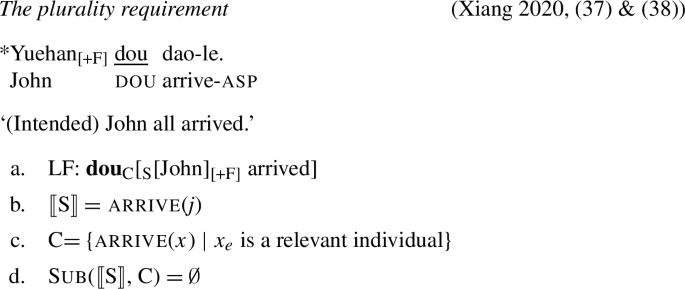

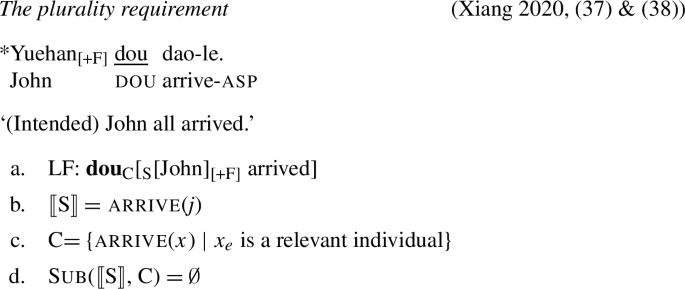

The non-vacuity presupposition gives rise to the well-known plurality requirement: dou’s associate has to be non-atomic, as shown in (35).Footnote 15 With an atomic associate, e.g., Yuehan ‘John’ in (35), the prejacent clause of dou does not entail any contextually relevant F-alternatives, except itself. Since the prejacent clause has no logically weaker alternatives, the set of sub-alternatives is empty, as shown in (35d), failing the non-vacuity presupposition. Hence, the associate of dou has to be non-atomic.

-

(35)

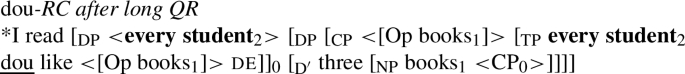

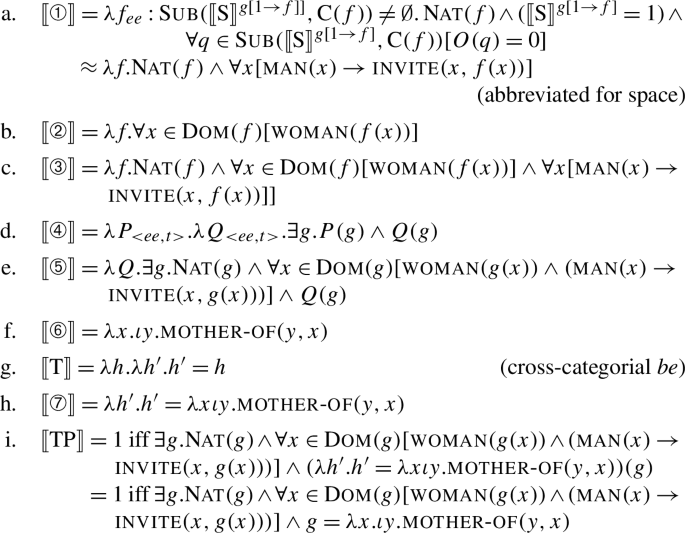

Given this analysis of dou, I now show that dou blocks long QR out of RCs due to its non-vacuity presupposition. In particular, we will see that long QR of the RC-embedded subj-QP out of the dou-RC leaves dou with an atomic associate.

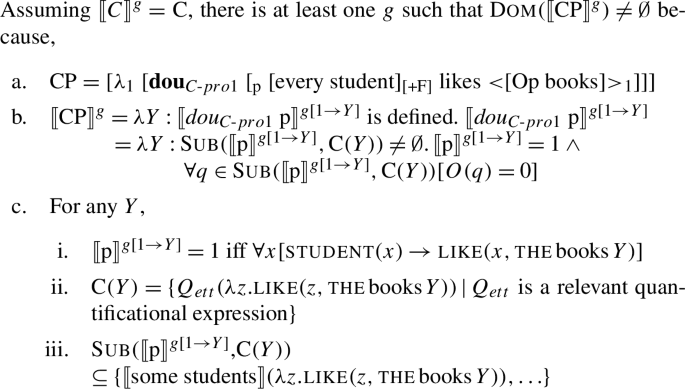

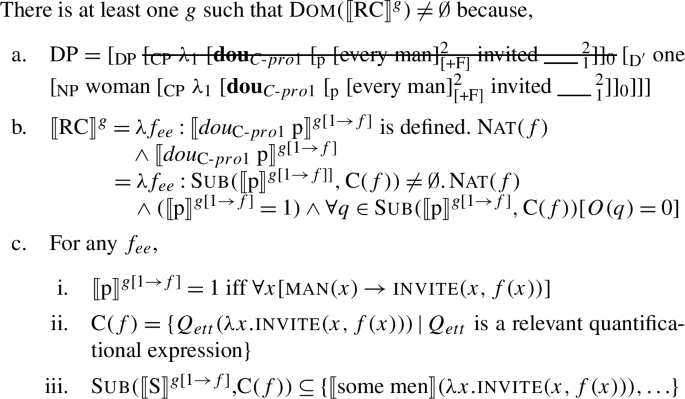

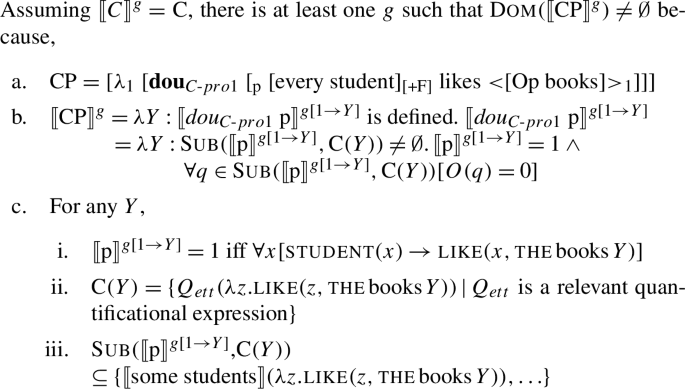

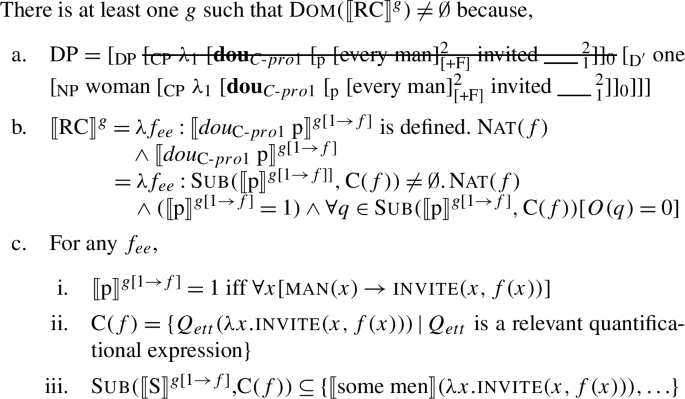

The non-vacuity presupposition of dou is satisfied and the relative clause is interpretable if the RC-embedded subj-QP, ‘every student’, is interpreted inside the dou-RC (36), as shown by the proof in (37). The prejacent clause of dou contains a gap left by relativization and the associate of dou is the RC-embedded subj-QP as shown in (37a). The quantificational domain of dou is thus a function from (plural) individuals to sets of alternatives, as indicated by the subscript ‘C-pro1’ on dou where ‘pro1’ is bound by \(\lambda _{1}\). The RC is interpreted as in (37b), with a presupposition that the set of sub-alternatives of the prejacent clause is non-empty. Since the associate of dou is non-atomic, there is at least one g such that for any y, there is at least one sub-alternative of the prejacent clause, as shown in (37c), thereby satisfying the non-vacuity presupposition of dou.

-

(36)

dou-RC without long QR

-

(37)

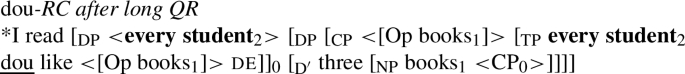

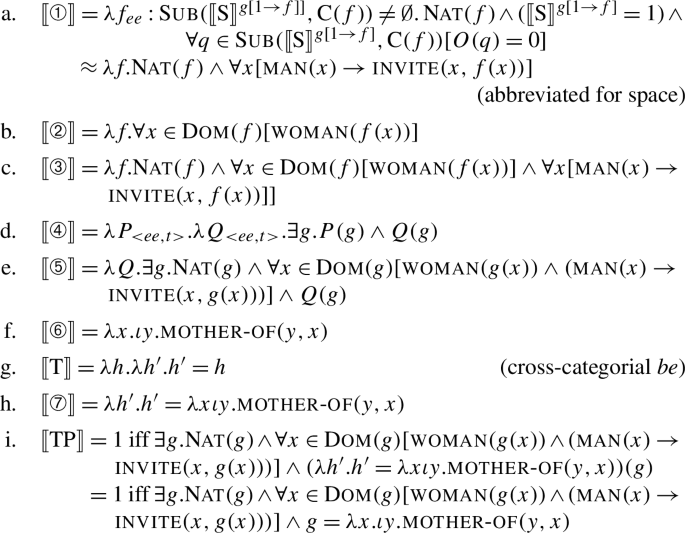

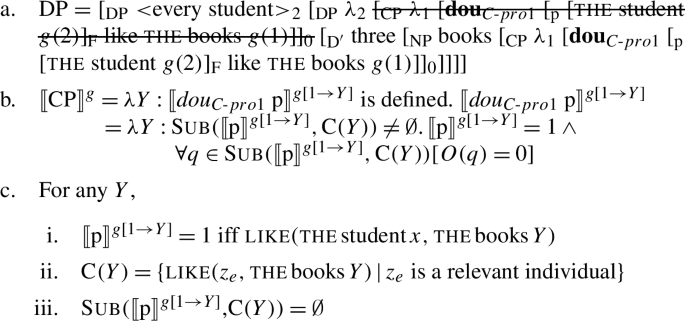

By contrast, if the RC-embedded subj-QP undergoes QR out of the dou-RC, as illustrated in (38), the non-vacuity presupposition of dou fails. Following Xiang (2020), I assume that dou does not move. QR of the subj-QP out of the dou-RC leaves dou to be associated with a trace, as shown in (39a). The trace left by QR is interpreted as ‘the student x’ by Trace Conversion (Fox 2002), assuming that \(\lambda _{2}\) binding the trace assigns 2 to x. Then the prejacent of dou gets the denotation in (39c-i). Since the trace is atomic, for any g and any y, the prejacent clause after long QR no longer asymmetrically entails any contextually relevant alternatives defined in (39c-ii), and therefore the set of the sub-alternatives is empty (39c-iii). Hence, the non-vacuity presupposition of dou fails and the dou-RC after long QR is always uninterpretable.

-

(38)

dou-RC after long QR

*I read [DP <every student2> [DP [CP <[Op books1]> [TP every student2 dou like <[Op books1]> de]]0 [D′ three [NP books1 <CP0>]]]]

-

(39)

For any g, assuming 〚C\(]\!\!]^{g} =\)C, Dom\(([\!\![\text{RC}]\!\!]^{g}) = \emptyset \), because,

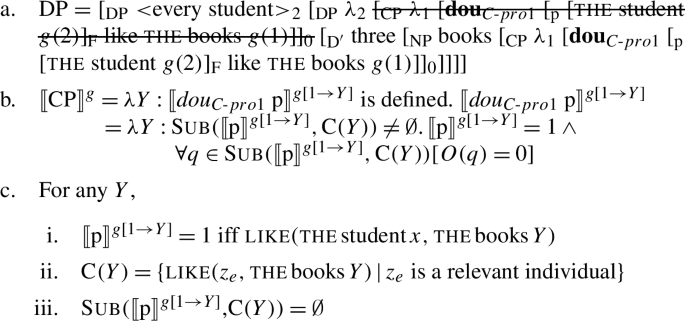

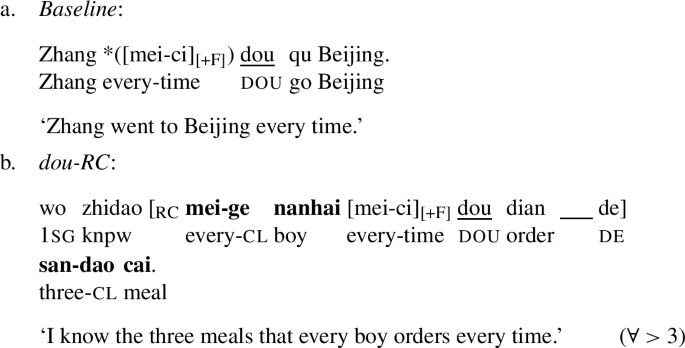

The proposed analysis predicts that if dou is not associated with the RC-embedded subj-QP, scope interaction between the subj-QP and an RC-external quantifier should reemerge. The prediction is borne out, as shown in (40). The baseline (40a) shows that dou can be associated with a quantificational adverb, such as mei-ci ‘every time’. In the dou-RC in (40b), dou is associated with the adverb ‘every time’ instead of the subj-QP ‘every boy’. The subj-QP is then able to take wide scope over the RC-external QP ‘three meals’ (∀>3).

-

(40)

The analysis also seems to predict that dou is unable to associate with an expression that has moved outside its prejacent clause. However, cases shown in (41) are counterexamples to this potential prediction. As observed by Lin (1998), dou can be associated with an RC-head, as shown in (41a), or a topic, as shown in (41b), which are both outside the prejacent clauses of dou.

-

(41)

In fact, the analysis does not imply that the associate of dou cannot move out of the prejacent clause. Instead, whether the moved element can reconstruct and be interpreted in its base position matters for the focus association. In (41), the RC-head NP, which is a plural expression, can reconstruct back to its base position inside the prejacent clause of dou. Then dou no longer associates with an atomic trace, different from dou in (38) where the QRed quantifier is obligatorily interpreted outside a dou-RC to take wide scope. The non-vacuity presupposition of dou can then be satisfied even if the associate has moved out of dou’s prejacent clause on the surface.Footnote 16 Hence, the acceptability of “long-distance” association of dou in (41) does not challenge the proposed analysis that dou blocks an RC-embedded subj-QP from undergoing long QR out of a dou-RC.

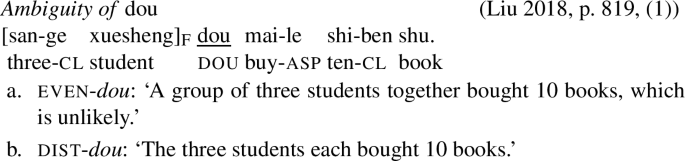

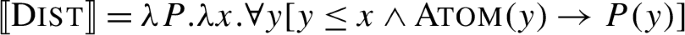

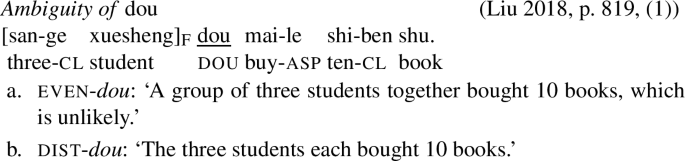

Before concluding the discussion for dou’s blocking effect, I briefly discuss an analysis of dou that is an alternative to the only-analysis (Xiang 2020) assumed in this paper. Liu (2017) proposes that an even-meaning in (42a) is the primary use of dou, given that dou is ambiguous between an even-reading and a distributive reading, as shown in (42). Liu (2017) then defines dou on analogy to even, as shown in (43), where dou does not alter the truth condition of its prejacent clause, but presupposes that its prejacent is the most unlikely proposition among its alternatives.

-

(42)

-

(43)

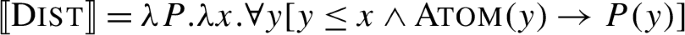

The distributive reading in (42b) is derived via a covert dist operator on VP, as defined in (44), following Link (1983).

-

(44)

Under the distributive reading, the prejacent entails all of its alternatives, as shown in (45). If p entails q, p is as likely as or less likely than q (Lahiri 1998; Crnič 2014). Hence, the presupposition of dou on likelihood is weaker than entailment, and is thus automatically satisfied. The even-meaning is thus trivialized under the distributive use of dou.

-

(45)

However, the puzzle on dou’s blocking effect considered in this paper cannot be easily solved under this analysis. Assuming that the trace left by QR of the universal quantifier is atomic, we leave dou associated with an atomic expression. Since the even-dou reading is not relevant here, we only consider the dist-dou reading. As shown in the derivation (47) for the dou-RC in (38) (repeated below as (46)), since the associate of dou is now atomic, the prejacent does not entail any alternative that is not itself, trivially satisfying dou’s presupposition in (43). Hence, the even-analysis of dou predicts the wide-scope reading of the embedded QP to be available in a dou-RC, contrary to fact.Footnote 17

-

(46)

-

(47)

The only-analysis of dou assumed in this paper, on the other hand, provides a direct solution to why dou blocks exceptional scope effects across RC-boundaries, as discussed above. Hence, the puzzle on dou’s blocking effect, as well as its solution, provide novel support for the only-analysis of dou. Furthermore, they are also in line with the distinction between even and only in English, where even, but not only, can associate with elements that have moved out of its scope and do not necessarily undergo syntactic reconstruction (Erlewine 2018).

To summarize, this section has accounted for the absence of scope interactions and binding out of the containing DP in dou-RCs by adopting the only-analysis of dou proposed by Xiang (2020). The blocking effect is due to the failure of dou’s non-vacuity presupposition caused by its association with an atomic trace left by QR. The next section is devoted to the new observation that a dou-ORC embedded in a specificational sentence admits a reading similar to the wide-scope reading of the RC-embedded QP and allows the RC-embedded subj-QP to bind a matrix pronoun. I argue that the observed “scope” effects do not result from scope taking, but rather from a functional interpretation of the relative clause, which is compatible with the requirements of dou.

5 Functional readings of relative clauses

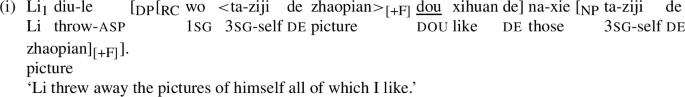

As shown in (11) and repeated below in (48), a multiple-individual reading is observed in an object RC containing dou embedded in a specificational sentence, but not in a subject RC counterpart embedded in the same type of sentence.

-

(48)

This section proposes that the observed multiple-individual reading in (48a) results from interpreting the ORC as a natural-function RC. I first provide empirical evidence for a natural-function analysis of the ORC in question, following Jacobson (1994) and Sharvit (1999), and then show that dou is compatible with a natural-function RC.

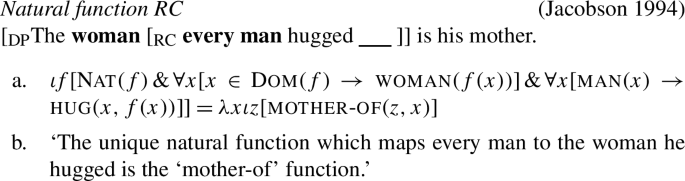

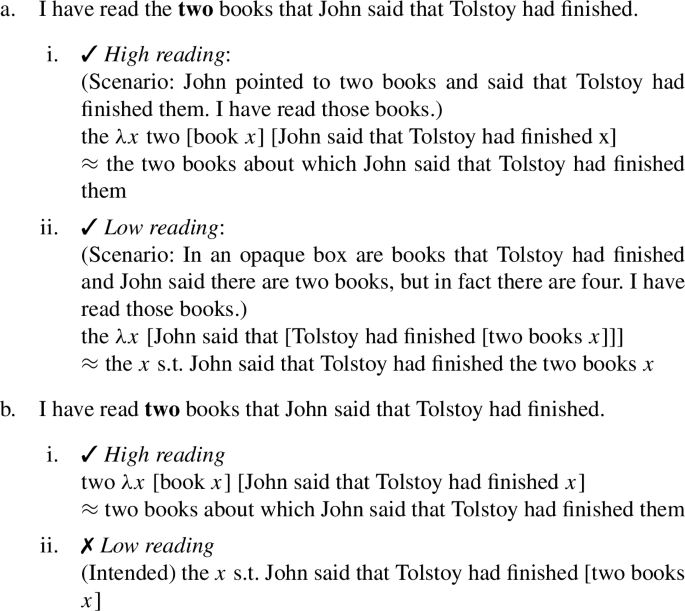

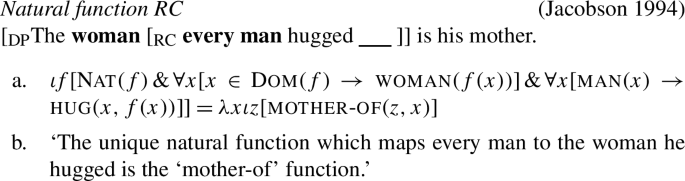

Like wh-questions with quantifiers, relative clauses with quantifiers embedded in the subject position also admit a natural-function reading, as shown in (49) (von Stechow 1990; Jacobson 1994). The ORC in (49) denotes a set of natural functions that map every man x to a woman x hugged.Footnote 18 Among the set of functions, there exists a unique natural function, i.e., the mother-of function, as stated by the post-copular part of (49).

-

(49)

The natural-function reading exhibits several properties that distinguish it from a genuine wide-scope reading of the RC-embedded subj-QP (Jacobson 1994, Sharvit 1999). First, natural-function RCs are only admitted in specificational sentences. Since the specificational copula be and the definite determiner are assumed to be cross-categorial, they are not selective of the type of their arguments, as long as the arguments connected by them match in type. In contrast, a non-specificational predicate of type 〈e,t〉 cannot be composed with a DP of type 〈e,e〉 containing a natural-function RC.

Second, the natural-function RC in (49) is felicitous in a context where a man hugged more than one women, as long as his mother is among the women he hugged. The same RC embedded in a non-specificational sentence is not felicitous in such context, as shown in (50).

-

(50)

Context: John hugged Sarah and his own mother, Bill hugged Mary and his own mother, Sam hugged his own mother, …

The contrast in (50) is due to how the uniqueness presupposition imposed by the definite determiner the is satisfied. When the definite determiner takes a natural function, instead of an entity, as its argument, its uniqueness presupposition is not imposed on the individual that each man is mapped to by the relative clause, but on the natural function. In other words, the uniqueness presupposition of the in (50a) is satisfied as long as there exists a unique natural function, i.e., the mother-of function in this case. By contrast, the uniqueness presupposition of the in the non-natural-function RC (50b) has to be satisfied by the existence of a unique individual. Since some men hugged more than one individual, the uniqueness presupposition of the fails, leading to the infelicity of (50b).

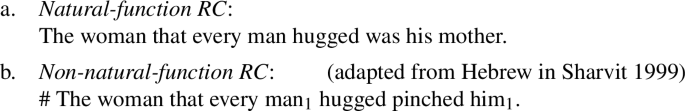

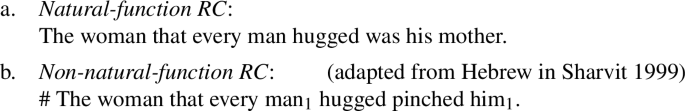

A Mandarin dou-ORC embedded in a specificational sentence also has the two properties discussed above. First, the observed multiple-individual reading disappears when the same ORC is embedded in a non-specificational transitive or intransitive sentence, as shown by the contrast between (51a) on the one hand and (51b-c) on the other. Hence, like the natural-function reading, the multiple-individual reading in (51a) is only admitted when the ORC is embedded in a specificational sentence.

-

(51)

ORC with dou

Second, like the natural-function RC in (50a), a dou-ORC embedded in a specificational sentence is felicitous in the same context that only requires the existence of a unique natural function. The same RC embedded in a non-specificational sentence (52b) does not have the intended multiple-individual reading at all, due to the incompatibility of a non-specificational sentence with a natural-function reading. An ORC without dou embedded in a non-specificational sentence (52c) admits the wide-scope reading and matrix-pronoun binding of the embedded subj-QP, but is infelicitous in the given context, because the scope effects are derived from long QR of the subj-QP instead of a natural-function interpretation of the ORC. Footnote 19

-

(52)

Context: John invited his own mother and Sally, Bill invited his own mother and Zoe, Jack invited his own mother...

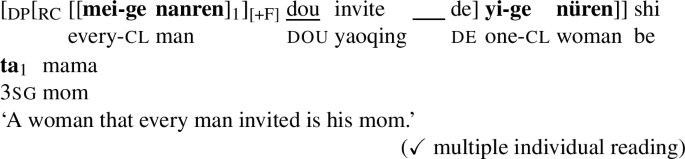

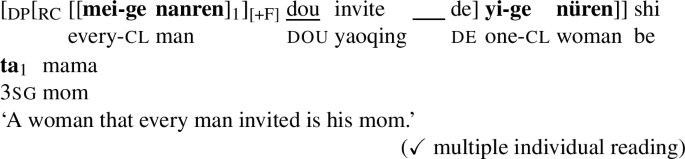

Note that since Mandarin does not have a counterpart of the with uniqueness presupposition, the contrast in uniqueness in (52) comes from the numeral yi ‘one’. Following Chierchia et al. (2012), I assume that a numeral is ambiguous between an at least reading and an exactly reading depending on its interaction with other operators and has a strong preference for being in the scope of an exhaustivity operator, as defined in (53).

-

(53)

Applying the exhaustivity operator excludes all alternatives that are not entailed by ϕ, and thus the exhaustivity operator strengthens an at least reading to an exactly reading, as illustrated in (54).

-

(54)

ϕ= One student came in.

Since the exactly reading of the numeral ‘one’ is equivalent to uniqueness, the contrast with respect to uniqueness in (52) is contributed by the numeral ‘one’ despite the absence of a definite determiner with a uniqueness presupposition (see also Tsai 2021 for a similar analysis involving obligatory exhaustivity on bare numerals in certain constructions).

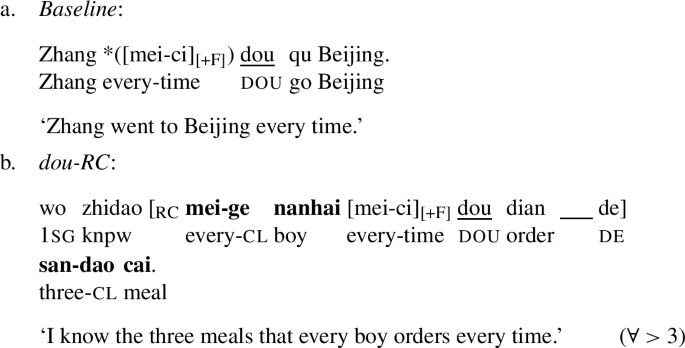

To summarize, a Mandarin dou-ORC can be analyzed as a natural-function RC only when it is embedded in a specificational sentence. The subject-object asymmetry shown in (48) and repeated below in (55) is also expected under this analysis. Following Chierchia (1993) and Sharvit (1999), I assume that analyzing the gap in the subject position in an SRC as a functional trace with two indices, as shown in (55c), causes a weak crossover effect (WCO), since the obj-QP co-indexed with the functional trace needs to cross over it in order to bind it. Hence, only an ORC but not an SRC can be analyzed as a functional RC.

-

(55)

We will now see that despite blocking long QR, dou inside an ORC does not block a natural-function interpretation. As shown in (51a) and repeated below as (56), the dou-ORC embedded in a specificational sentence has a natural-function reading. The prejacent clause of dou (labeled as ‘p’) contains a functional gap bound by both the embedded subj-QP and the RC-head, as shown in (57a), and denotes a set of functions mapping every man x to a woman x invited. The RC is defined only if the prejacent clause of dou has at least one contextually salient sub-alternative, according to the definition of dou proposed in Xiang (2020); see (57b). Since the embedded subj-QP ‘every man’ is non-atomic, and does not move out of dou’s prejacent clause, dou can be associated with it to guarantee that there is at least one alternative asymmetrically entailed by the prejacent clause in the set of the contextually relevant alternatives (57c). The non-vacuity presupposition of dou is thus satisfied and the dou-ORC is interpretable.

-

(56)

-

(57)

The composition of the natural-function RC with the rest of the sentence is illustrated in (58)–(59). Since the quantifier-distributor dou does not affect the truth-condition of its prejacent clause and the presupposition of dou is satisfied in a natural-function RC, the interpretation of the relative CP (➀) is abbreviated as in (59a) for simplicity of illustration.

-

(58)

-

(59)

Before leaving the topic of functional readings of relative clauses, I would like to briefly discuss another type of functional reading observed in relative clauses that are embedded in non-specificational sentences, namely the pair-list reading as shown in (60) (Sharvit 1999).

-

(60)

The pair-list reading is similar to the wide-scope reading and matrix-pronoun binding of the RC-embedded QP, but it is derived from analyzing the RCs as a set of pair-list functions and does not require scope taking across clause boundaries.

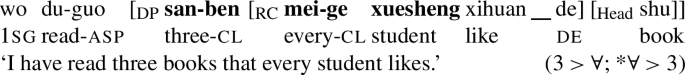

However, even though the pair-list RC analysis derives the same effects, it has an undesirable prediction for scope interaction in Mandarin RCs. It predicts that the wide-scope reading of the RC-embedded subj-QP should be available when the relative CP is in a post-D position, contrary to fact, as shown in (26) and repeated below in (61). The absence of scope ambiguity in post-D RCs is straightforwardly captured on the long QR analysis, as discussed in Sect. 3.2. Hence, the pair-list RC analysis is not an empirically adequate alternative to the proposed long QR analysis in explaining scope interaction in Mandarin RCs.

-

(61)

To summarize, Sect. 4 and Sect. 5 have discussed the interaction of dou with scope effects in Mandarin ORCs. Due to its non-vacuity presupposition, dou blocks long QR, giving rise to the blocking effect of scope ambiguity in a dou-RC embedded in a non-specificational sentence. However, dou is compatible with a natural-function interpretation of ORCs; we therefore observe a multiple-individual reading in an ORC embedded in a specificational sentence, which is similar to a wide-scope reading of the embedded subj-QP.

6 Long QR out of prenominal subject RCs

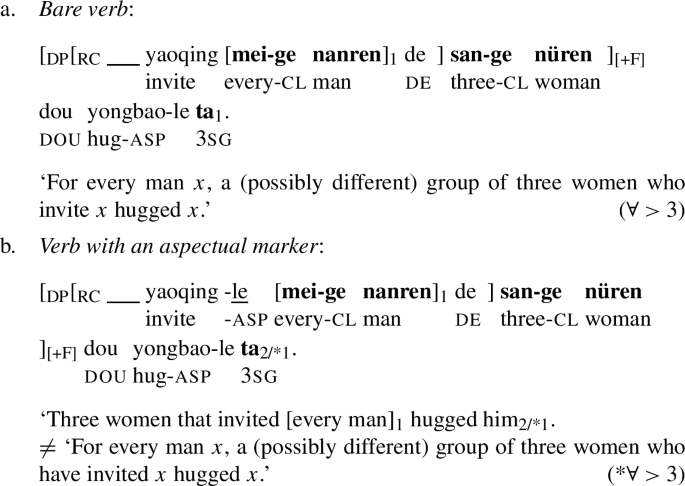

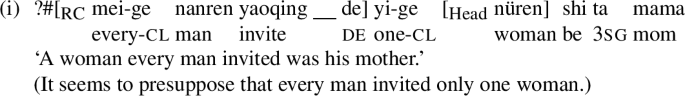

Having discussed the interaction between dou and scope effects in ORCs, I now turn to scope interaction in SRCs, which also follows from the proposed long QR analysis. As shown in (12) and repeated below in (62), an SRC with a bare verb in (62a) exhibits scope ambiguity, but its counterpart with an aspectual marker, as shown in (62b), does not. The asymmetry is not observed in ORCs and is not available to all speakers.

-

(62)

Scope ambiguity in SRCs

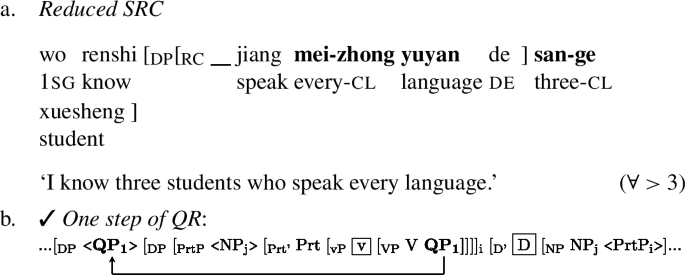

I propose that the asymmetry is related to RC sizes. While a Mandarin SRC with a bare verb can be analyzed as a reduced RC, its counterpart with an aspectual marker cannot, due to the obligatory projection for aspect. As shown below, a full-sized subject RC, compared to a reduced SRC or an ORC, requires the RC-embedded obj-QP to undergo one more step of QR to take wide scope out of the RC. Crucially, the additional step is ruled out due to its semantic vacuity, leading to a degradation in the wide-scope reading of the RC-embedded obj-QP. The inter-speaker variation can then be attributed to whether a speaker’s grammar allows an SRC with a bare verb to be reduced.

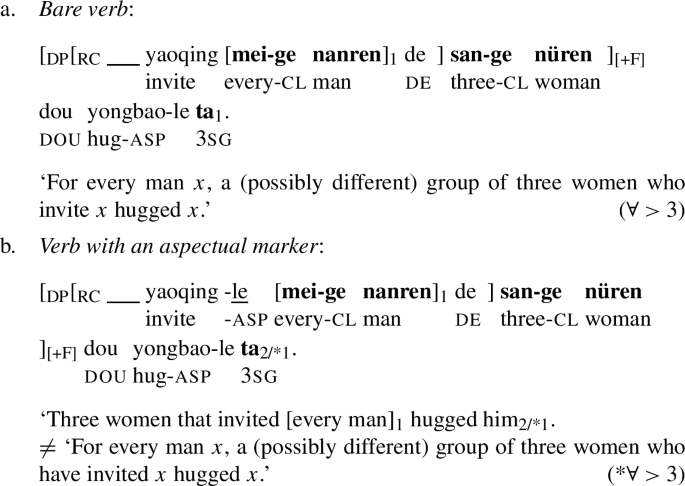

I assume that only SRCs can be reduced and the highest projection of a reduced RC is some projection lower than TP, following Bhatt (2006). Since aspect requires the projection of TP, an SRC with an aspectual marker cannot be reduced, and has to stay as a full-sized CP (63a), which has one more phase than a reduced SRC.Footnote 20 In a full-sized SRC (63), the RC-embedded obj-QP needs to undergo QR to [Spec, vP] first before the further step of QR out of the relative CP (63b-i); otherwise, the PIC would be violated by a single instance of QR crossing two phase heads (63b-ii).

-

(63)

By contrast, since a reduced SRC does not have the CP phase, the RC-embedded obj-QP can undergo a single step of QR out of the relative clause to [Spec, DP], as shown in (64b), without violating the PIC.

-

(64)

Recall that as we saw in (25) in Sect. 3.1, QR of the RC-embedded subj-QP out of an ORC also takes only one step of movement, on a par with a reduced SRC but not a full-sized SRC. I argue that it is the additional step of QR in a full-sized SRC (63b), compared to that in a reduced SRC (64b) and an ORC (25), that makes the wide-scope reading of the RC-embedded QP unavailable.

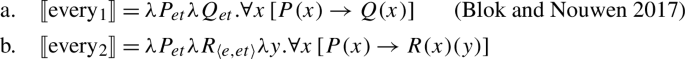

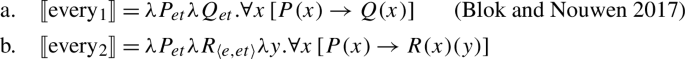

Crucially, following prior work (Montague 1973, Partee and Rooth 1983, Hendriks 1993, Keenan 2016, Blok and Nouwen 2017, Blok 2019, Blok and Nouwen 2020, a.o.), I assume that an object QP does not resolve type-mismatch by obligatorily undergoing QR to [Spec, vP], but rather can do it in situ. For example, Blok and Nouwen (2017) argue for an in-situ analysis, in which a quantifier like every can be interpreted in an object position, because it is ambiguous between two types, as shown in (65) (cf. Heim and Kratzer 1998, p. 180).

-

(65)

Therefore, resolving type-mismatch is not an independent motivation for the step of QR from object position to [Spec, vP]; instead, the step of QR to [Spec, vP] applies only for the obj-QP to take inverse scope over the reconstructed subj-QP (Hornstein 1995, Johnson and Tomioka 1997, Sauerland and Elbourne 2002, a.o.). In other words, QR to [Spec, vP] does not satisfy Scope Economy for free, and is possible only if doing so creates a new scope relation.

This assumption has two desirable results for the puzzle on scope effects in Mandarin SRCs. First, since the step of QR from object position to [Spec, vP] is no longer obligatory, the RC-embedded obj-QP can undergo one step of QR out of the RC, as long as it does not violate the PIC or Scope Economy. Hence, the RC-embedded obj-QP is able to undergo one step of QR out of a reduced SRC, as shown in (64b), but not out of a full-sized SRC, as shown in (63b).

Furthermore, since QR from object position to [Spec, vP] obeys Scope Economy, i.e., being semantically non-vacuous, only if it creates a new scope relation, the first step of QR in a full-sized SRC, as marked by  in (63b-i), is no longer available.Footnote 21 Since the RC-embedded object QP cannot undergo one step of QR out of the full subject RC either, as shown in (63b-ii), it is syntactically impossible for the RC-embedded obj-QP to take wide scope in a full-sized SRC. The contrast of scope interaction with respect to aspectual marking in Mandarin SRCs shown in (62) is thus explained.Footnote 22Footnote 23

in (63b-i), is no longer available.Footnote 21 Since the RC-embedded object QP cannot undergo one step of QR out of the full subject RC either, as shown in (63b-ii), it is syntactically impossible for the RC-embedded obj-QP to take wide scope in a full-sized SRC. The contrast of scope interaction with respect to aspectual marking in Mandarin SRCs shown in (62) is thus explained.Footnote 22Footnote 23

Before concluding this section, I would like to briefly touch on the inter-speaker variation in the effect of embedded verb forms, as mentioned in Sect. 2.2. The asymmetry with respect to the presence of an aspectual marker in an SRC is not available to all Mandarin speakers. The consulted speakers who do not report the asymmetry uniformally find the wide-scope reading of the embedded obj-QP unavailable in all SRCs, regardless of the presence of aspectual markers. It is possible that not every speaker’s grammar allows an SRC with a bare verb to be a reduced RC. For speakers who analyze all relative clauses as full-sized RCs, long QR of the embedded obj-QP takes the same number of steps out of an SRC with a bare verb as out of an SRC with an aspectual marker, and thus is equally degraded compared to long QR out of an ORC. More theoretical and experimental research is needed to test this hypothesis.

To summarize, I have proposed an analysis for the effect of aspectual marking on scope ambiguity in Mandarin SRCs. Specifically, the contrast in (62) can be attributed to the fact that an SRC containing a bare verb can be reduced to a projection lower than TP, while an SRC with aspectual marking on the embedded verb has to stay as a full-sized CP. The size difference requires the RC-embedded obj-QP to take one more step of QR to take wide scope in the latter than in the former, which causes degradation of the wide-scope reading of the RC-embedded obj-QP.

7 Conclusion

This paper has examined exceptional scope effects in Mandarin relative clauses, and argued for a long QR analysis for the wide-scope reading and matrix-pronoun binding of RC-embedded QPs. In a prenominal pre-D object RC, the RC-embedded subj-QP undergoes long QR across the RC-boundary to [Spec, DP]. This step of QR does not violate the syntactic and semantic constraints on QR, namely the PIC and Scope Economy, due to the pre-D position of the relative clause, as discussed in Sect. 3.

The proposed analysis accounts for empirical data that cannot be directly accounted for under reconstruction for scope, which is available in Mandarin but insufficient to derive all scope interactions considered in this paper. First, the long QR analysis captures the observation that when the focus-sensitive exhaustifier dou is present inside the relative clause, the exceptional scope effects disappear. The non-vacuity presupposition of dou blocks long QR, but dou has been shown not to block reconstruction, as discussed in Sect. 2.1.

Furthermore, subject relative clauses admit exceptional scope effects depending on the size of the relative clause. Only an SRC containing a bare verb, but not one with aspectual marking on the embedded verb, admits exceptional scope effects. Under the long QR analysis, the size difference leads to a difference in the number of QR steps required for the RC-embedded obj-QP to take wide scope out of the relative clause. A full-sized SRC requires two steps of QR of the embedded QP, while a reduced SRC requires only one step of QR.

From a theoretical perspective, the proposed long QR analysis is in line with the view that it is not a finite clause boundary, but rather a phase boundary and lack of motivation for QR to proceed successive-cyclically through the phase boundary, that creates the effect of clause-boundedness on QR. Once a phase head can be circumvented by an independent movement, e.g., the overt movement of an RC to a prenominal pre-D position in Mandarin, QR can take place across a finite clause boundary without violating any locality constraints. However, the Complex-NP Constraint for overt movement will not be relaxed in Mandarin in the same manner. Overt movement has been argued to be subject to additional constraints, such as cyclic linearization (Fox and Pesetsky 2005), and the lack of an escape hatch at the edge of the relative CP still blocks overt movement out of a Complex-NP island.

I conclude with remarks on two puzzles related to the phenomena analyzed in this paper. The first is the scope rigidity of Mandarin transitive clauses, as compared to the scope flexibility in their English counterparts. While the proposed analysis does not provide a direct answer to the puzzle, it points toward a potential solution: different from its English counterpart, a Mandarin subj-QP in a transitive clause does not reconstruct to a position below vP for scope. Presented below is a sketch of the idea.

As argued for in Hornstein (1995), Johnson and Tomioka (1997), Sauerland and Elbourne (2002), among others, the scope ambiguity between a subj-QP and an obj-QP in an English transitive clause can only be derived from reconstruction of the subj-QP back into vP. Under the conventional approach, the obj-QP can undergo QR to [Spec, vP] to resolve the type-mismatch, while under the analysis in Blok and Nouwen (2017), where type-driven QR is not independently motivated, QR of the obj-QP to [Spec, vP] is only licensed for creating new scope relations. Then if the subj-QP of a transitive clause in Mandarin dose not reconstruct back into vP for scope, there is no independent motivation for the obj-QP to undergo QR to the edge of vP.

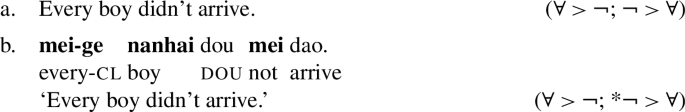

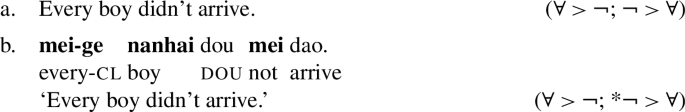

In fact, scope interaction between a subj-QP and negation, as shown in (66), provides evidence for the difference between Mandarin and English with respect to the reconstruction of a subj-QP for scope. Unlike an English subj-QP in (66a), the Mandarin one in (66b) cannot be interpreted as taking narrow scope relative to negation. If the scope ambiguity in the English negation (66a) is due to the possibility of reconstructing the subject below negation, then it is likely that Mandarin does not allow the subject to reconstruct to a position below negation for scope. However, the reason that subject reconstruction for scope is not available in Mandarin is out of scope of this paper and thus left open for future research.Footnote 24

-

(66)

The second puzzle relates to differences among quantifiers. Compared to ORCs, SRCs in Mandarin show stronger dispreference for the wide-scope reading of the RC-embedded quantifier if it is daduoshu ‘most’ or a modified numeral, such as zhishao liang-ge ‘at.least two-cl’, instead of a universal one. The variation with respect to different quantifiers is puzzling under the QR theory, a syntactic theory that is not sensitive to quantifier classes, but not surprising, since it is not unique to Mandarin relative clauses.

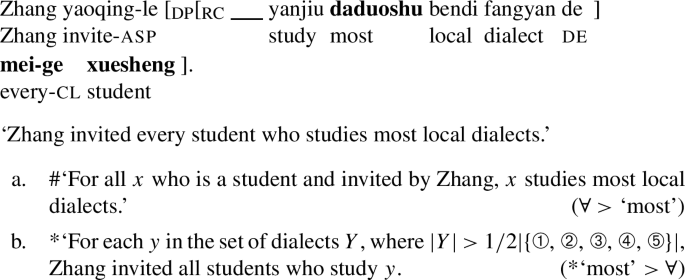

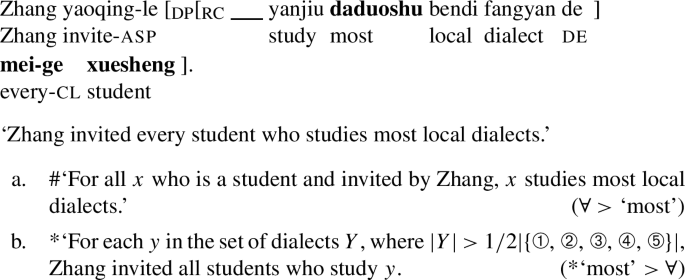

Take daduoshu ‘most’ as an example. As shown in (67), the sentence is not felicitous in a context forcing the wide scope of the RC-embedded daduoshu ‘most’ over the RC-external ‘every’. The ‘every’-wide scope reading (67b) is available to the sentence, but is not true in the given context, since none of the students invited by Zhang study most of the languages; in fact, none of them study more than two out of the five languages. The sentence is only true in the context under the ‘most’-wide scope reading, and therefore, the infelicity of the sentence in the context strongly suggests that the ‘most’-wide scope reading is unavailable.

-

(67)

Mandarin SRC with counting quantifier embedded

Context forcing ‘most’-wide scope: Suppose that there are five local dialects and let’s call them ➀, ➁, ➂, ➃, and ➄ respectively. Four students A, B, C, and D are linguistics graduate students studying the local dialects. Specifically, A studies ➀ and ➁; B studies ➂ and ➃; C studies ➄; D studies ➁ and ➃. Zhang invited students A, B, and D to a reading group focusing on most of the local dialects, namely ➀, ➁, ➂, and ➃. Then I said...

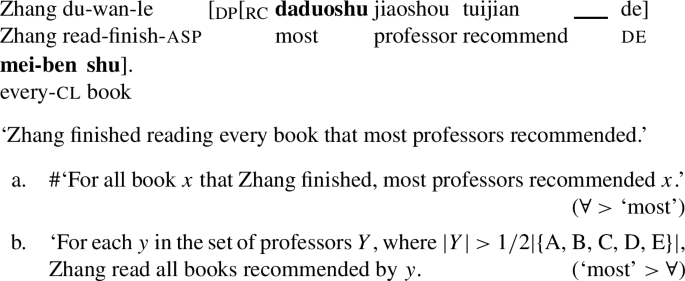

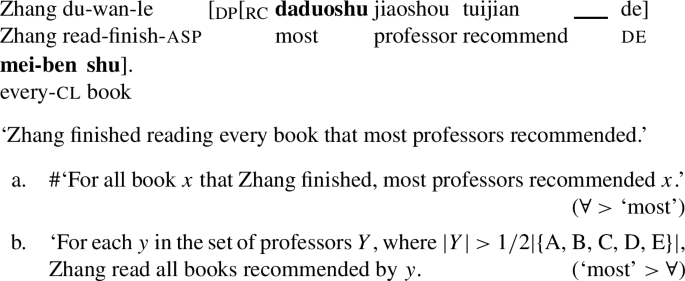

RC-embedded most in an ORC, on the other hand, is able to take wide scope, although it is less natural and needs to be forced by a context such as the one in (68). The ‘every’-wide scope reading (68a) is not true in the given context, since none of the books finished by Zhang was recommended by more than two professors. According to the speakers I consulted, the sentence sharply contrasts with (67) in its acceptability in a context that forces ‘most’-wide scope, indicating that the ‘most’-wide scope reading (68b) is available in an ORC.

-

(68)

Mandarin ORC with counting quantifier embedded

Context forcing ‘most’-wide scope: Suppose that there are five professors A, B, C, D, and E, and there are five books recommended by them, which are represented as ➀, ➁, ➂, ➃, and ➄. Specifically, A recommended ➀ and ➁; B recommended ➀, ➂, and ➃; C recommended ➂ and ➃; D recommended ➁; E recommended ➄. Zhang finished reading books recommended by professors A, B, C, and D, which are most of the professors, namely the books ➀, ➁, ➂, and ➃, and I said...

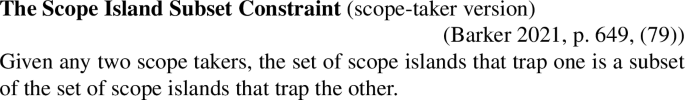

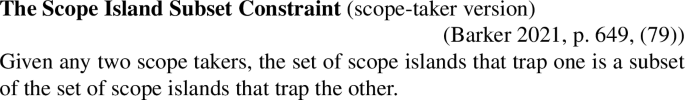

Barker (2021) shows with data from previous literature and natural occurrences that English relative clauses with definite relational heads are not scope islands for each and potentially every. He therefore argues that scope islands and scope takers are not uniform in their strengths of trapping quantifiers and escaping islands respectively. The different flavors of islandhood and island escapers then fall under a more general constraint, the Scope Island Subset Constraint, as shown in (69). Then we can argue that relative clauses are not scope islands for universals (and also indefinites, given that indefinites are usually capable of taking unbounded scope), but trap quantifiers like most and modified numerals, which are assigned a weaker strength of escaping scope islands.

-

(69)

The constraint does not obviously capture the distinction between Mandarin SRCs and ORCs in trapping non-universal quantifiers. If a quantifier is trapped in an island when it is in the object position, the Scope Island Subset Constraint does not directly predict that it can escape the island when it is in the subject position.

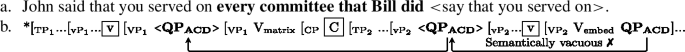

Additional challenges apply to other well-known views on differences among quantifiers, such as Beghelli and Stowell (1997). On their view, quantifiers move to specifiers of different functional projections. Distributive quantifiers like every and each obligatorily move into [Spec, DistP], a relatively high projection, while quantifiers like at least two and most, which they call counting quantifiers, are interpreted in their case positions, i.e., [Spec, AgrO-P] and [Spec, AgrS-P] for object and subject QPs, respectively, and take scope in situ.

On such a view, one could potentially stipulate that a quantifier in [Spec, AgrO-P] cannot undergo further QR, but once a quantifier reaches DistP, it is possible to scope out of the clause if doing so does not violate the syntactic and semantic constraints on QR. This would restrict the scope of counting quantifiers in object position, as desired. However, the stipulation is notably incompatible with the proposal that clause-internal scope interaction between subject and object QPs is derived from total reconstruction of the subject QP to a position below the scope-taking position of the object QP, instead of QR of the object QP above (Hornstein 1995, Johnson and Tomioka 1997, Sauerland and Elbourne 2002, a.o.). Under the stipulation that a quantifier in a position as high as DistP can scope out of a clause, a distributive object QP should be able to undergo QR over the surface subject position to take inverse scope.

Even more seriously, given the arguments of this paper, the hierarchical structure proposed in Beghelli and Stowell (1997) is incompatible with the assumption that QR does not have to stop at every propositional node or even at the edge of vP to resolve type mismatch, following Blok and Nouwen (2017), among others. The proposal in Beghelli and Stowell (1997) requires a distributive object QP to obligatorily stop at [Spec, DistP], which is in principle in a position between TP and VP. Then even in a reduced SRC in Mandarin, as shown in (64) and repeated below as (70), two steps of QR would be needed, since the embedded object QP has to stop at the edge of the embedded vP to check the Dist feature. Therefore, the observation that only a Mandarin SRC containing a bare verb, but not an SRC with aspectual marking on the embedded verb, exhibits wide-scope reading of the RC-embedded object QP can no longer be explained by the different steps of QR taken in each SRC.

-

(70)

In conclusion, this paper has proposed a novel account for apparently exceptional scope effects in Mandarin relative clauses. There are still scope-related puzzles beyond relative clause construction, universal quantifiers, and Mandarin that are left open from the current analysis, but they together with the proposed analysis highlight the importance that a comprehensive scope theory needs to be able to capture how syntactic structures and semantic properties of different quantifiers interact to derive their different scope-taking behaviors.

Notes

For simplicity, SRC abbreviates subject RCs, while ORC abbreviates non-subject RCs. In ORCs, the RC-embedded QP is always in the subject position, and thus is abbreviated as subj-QP. Correspondingly, in SRCs, the RC-embedded QP is obj-QP.

Note that if the matrix pronoun is replaced by a third person plural ta-men, the wide-scope reading and matrix pronoun binding become available. However, with a plural pronoun, it is unclear to me whether we get real variable binding or just coreference with the plural pronoun. Hence, I avoid using plural pronouns in the paper due to potential ambiguity.

Note that the RC-embedded obj-QP is fronted to a preverbal, pre-dou position. This is independently due to the leftness condition of dou, which requires its associate to be on its left side. This raises the possibility that the SRC with the object fronted in (11b) might be an appositive relative clause, which causes the multiple-individual reading to be unavailable. In the following context (i) which forces a restrictive reading of the relative clause, the SRC in (11b) is felicitous, but the multiple-individual reading is still not available. Hence the contrast in (11) is not due to restrictiveness of the RCs.

(i) Context forcing a restrictive RC: Suppose that there are only three languages in the world, A, B, and C. Several students speak A, several speak B, several speak C, and several speak all of A, B, and C. Then I say...(11b).

Note that the contrast between (12a) and (12b) is not available to all Mandarin speakers. Speakers who do not have this contrast usually find both cases lack the intended scope effects. I discuss one possibility for this variation in Sect. 6. Again we can also confirm that this judgment is not due to the possibility of an appositive rather than restrictive parse. In a context forcing a restrictive reading (i), the SRC in (12b) is felicitous, but the intended scope effects are still unavailable.

(i) Context: There are three men, A, B, and C. There are three women who invited A, three women who invited B, three women who invited C, and three women who invited A, B, and C.

The contrast could be explained under Larson and Wu’s analysis if we assume that the aspectual marker blocks local QR of the RC-embedded obj-QP over the reconstructed subj-QP. Thanks to a reviewer for pointing out that Lin (2013) proposes an account along these lines. It has been observed that while scope interaction between subject and object QPs is available in both finite and nonfinite clauses in English, it is available only in nonfinite clauses in Mandarin. Lin (2013) attributes the contrast to finite tense being a barrier for QR and the locus of tense being in different positions in English and Mandarin. The locus of tense in English is in C (Chomsky 2004), while tense in Mandarin is in T. It seems to be a plausible analysis, but further research is needed, especially into the distinction between Mandarin and English tenses (e.g., under Chomsky’s 2004 argument that the locus of tense is in C in all languages, why and how Mandarin is different from English in this way). Since this is out of the scope of this paper, I do not pursue this idea in detail here and leave it open for future research.

This version of the PIC is similar to Subjacency, where only the number of phase heads crossed in one instance of movement matters, but the complement of each phase head will not become invisible at LF when the next phase head is reached. Cecchetto (2004) assumes that covert movement such as QR takes place after spell out, following Nissenbaum (2000), and access to LF is not successive cyclic, but rather a one-step operation at the end of the derivation. The definition diverges from the classical PIC (Chomsky 2000, 2001), but is able to derive all the relevant facts captured by the conventional PIC. Since QR as a type of movement obeys the constraint that no more than one phase head can be crossed in one step, QR is still successive-cyclic.

Different from the original version of Scope Economy in Fox (2000), I do not consider resolving type-mismatch to be an independent motivation for QR in this paper, since I assume that type-driven QR is available, but not obligatory, following Blok and Nouwen (2017), among others (e.g., Montague 1973, Partee and Rooth 1983, Hendriks 1993, Keenan 2016). The question of resolving type-mismatch in situ is discussed in Sect. 6.

The analysis also correctly derives the absence of clause-boundedness of QR in the ACD case shown in (15b). The details are omitted here due to space and relevance, but see Cecchetto (2004) for detailed argumentation.

The analysis proposed in this paper for the scope puzzles is also compatible with the Head External analysis (Montague 1973, Partee 1975, Chomsky 1973, 1977, Heim and Kratzer 1998, a.o.) and the Matching analysis (Lees 1962, Chomsky 1965, Sauerland 1998, 2000, Hulsey and Sauerland 2006, a.o.) of relative clauses, assuming that they are available in Mandarin. The implementation is omitted due to space.

Kayne (1994) proposes that prenominal RCs are all TPs moved from a postnominal position to [Spec, DP], leaving the RC head and relative operator stranded. De Vries (2002) provides extensive arguments against movement of only the TP in a relative clause to derive an [RC-D-N] word order. Therefore, I assume movement of CP instead of TP for my analysis.

Alternatively, the relative CP could also undergo semantic reconstruction. Since a relative CP is of type 〈e,t〉, it can potentially leave a higher type trace at the postnominal position and be interpreted in its landing site. One advantage of assuming semantic reconstruction over syntactic reconstruction is that we do not need to assume the timing between QR and reconstruction, to be discussed in the next paragraph. However, there are independent arguments in the literature against higher-type traces (Chierchia 1984, Landman 2006, Poole 2022; see also Moulton 2015 for arguments that complement CPs leave type-e traces). Furthermore, according to the Condition on Trace Typing proposed by Ruys (2015), under semantic reconstruction of the relative CP, the trace of RC-head NP in the higher copy of the CP defaults to type e and reconstruction of the RC-head NP is blocked. Hence, it is unclear how, if possible at all, semantic reconstruction of the relative CP can be compatible with a Head Raising analysis of the RC. The choice between syntactic and semantic reconstruction, as well as interpretation of prenominal RCs under Head Raising, are challenging puzzles, but orthogonal to the proposed analysis for the scope effects in this paper; hence, I leave them open for future research. For simplicity of illustrating my proposal, I adopt syntactic reconstruction of relative CP here.

It is abbreviated as “the women X” henceforth for simplicity, where the capital letter X represents plurality.

The denotation of the quantifier every is presuppositional, i.e., 〚every\(]\!\!]= \lambda Q_{et}. \lambda P_{et}: \exists x \in D_{e} \, [P(x)]. \, \forall x [P(x) \rightarrow Q(x)]\). For example, the QP every man presupposes that there exists at least one man. I will leave out the presupposition part in the derivation henceforth for simplicity.

Note that the sentence is grammatical if ‘John’ is stressed, in which case dou has an even-like reading, as mentioned in Xiang (2020, footnote 15). Since the even-reading is not relevant here, I leave this reading aside.

An RC-internal dou can be associated with the external RC-head even when reconstruction of the RC-head is blocked, as shown in (i). Coindexed with the matrix subject, the reflexive, ta-ziji, embedded in the RC-head NP must be interpreted RC-externally by Condition A. The unavailability of reconstruction does not challange the proposed analysis. Under a Matching analysis of the RC, where the external RC-head is base-generated RC-externally and matched under identity in meaning with a silent internal head, the associate of dou is the RC-internal head, instead of the RC-external head or a gap. The RC-internal head is non-atomic as long as the RC-external head is non-atomic, and thus a proper associate of dou. Hence, even if the external RC-head is not interpreted in the gap position, the “long-distance” association of dou with the RC-head in (i) is still licensed.

Even if we don’t assume that the trace left by QR of the universal is atomic, the even-analysis of dou does not predict that dou blocks long QR either. When dou is associated with a non-atomic trace, dou accesses the distributive reading with the presupposition satisfied in the same maner as (45). Since the prejacent entails of all of its alternatives, the prejacent is as likely as or less likely than its alternatives, which satisfies dou’s presupposition in (43); therefore, a dou-ORC is predicted to admit long QR, contrary to fact.

Jacobson (1999) defines a natural function informally as a “procedurally defined function”, and distinguishes it from a pair-list function in the following way: “A procedurally defined function is an intensional one: its value can be computed for any new individual added to the world … A random list of ordered pairs – while extensionally equivalent to a procedurally defined function for a given domain – is not a recipe in the same sense” (Jacobson 1999, footnote 23).

When the same relative clause without dou in (52b) is embedded in a specificational sentence, as shown in (i) below, a natural-functional reading is expected and it should be as felicitous as (52a) in the given context, but a few native speakers I consulted with considered it to be less natural, if not entirely impossible, in the context. I do not have an answer for the contrast between (52a) in the main text and (i) below, but one possibility is that long QR is always preferred over the natural-functional analysis whenever long QR is possible, as in the case below where dou is not present and nothing blocks long QR out of the relative clause.

I do not assume that a full-sized relative clause has the same size of full matrix clause, due to several differences related to the peripheries, such as their abilities of admitting sentence final particles.

One may wonder why the subject-QP, which is the RC-head, cannot reconstruct back into the RC-embedded vP to derive the inverse scope, as in English transitive clauses discussed in Sauerland and Elbourne (2002), given that the RC-head does reconstruct into the relative clause in Mandarin and the subject originates inside vP. It is possible that Mandarin does not reconstruct the subject back into a vP-internal position, as discussed in detail in Sect. 7.

Alternatively, the degradation of the wide-scope reading of an RC-embedded obj-QP in a full-sized SRC, compared to that in a reduced SRC, could be attributed to processing costs: the additional step of QR in a full-sized SRC is syntactically possible, but involves a higher processing cost. Following the Processing Scope Economy proposed by Anderson (2004) and experimental evidence on processing costs of QR (Syrett and Lidz 2011, Tanaka 2015, a.o.), Wurmbrand (2018) argues that QR is not always clause-bounded; rather, the processing cost of QR increases as more steps of QR are required by the inverse scope, leading to the degradation of cross-sentential QR. As shown in (63), (64) and (25), QR out of a full-sized SRC takes two steps, while QR out of a reduced SRC or an ORC only requires one step. According to Wurmbrand’s version of Processing Scope Economy, the RC-embedded QP taking a wide scope reading in a full-sized SRC is expected to create higher processing cost and thus is less acceptable than that in a reduced SRC or an ORC. Crucially, however, this processing-based approach similarly requires the assumption that type-driven QR is not obligatory.

The assumption of both this syntactic account and the processing-based account noted in the previous footnote that type-driven QR is not obligatory faces potential challenges in capturing ACD data. The matrix reading of an ACD construction, which is derived from the embedded QP containing the ACD site undergoing long QR across a finite clause boundary, becomes unexpected under this assumption, as shown in (i). Without type-driven QR, the first step of QR to the embedded [Spec, vP] in (i-b) would be unmotivated, since it does not create any new scope relations, but this step is required by the PIC.

(i) Matrix reading of ACD

There is a potential route to save these approaches. Overfelt (2020) suggests that the restricted distribution of sloppy pronouns in ACD constructions shows that the QR to resolve ACD, which is a syntactic operation, cannot be licensed by postsyntactic conditions. It seems to be at odds with the conventional understanding of QR, which is sufficiently licensed when it can create interpretational distinctions. Since QR for ACD has a more structural than interpretive motivation, it is possible that QR for ACD does not need to obey the same set of constraints as QR for scope taking, for example the requirement of being semantically non-vacuous.

Since both syntactic and processing-based approaches can account for the degradation of scope effects in Mandarin full-sized SRCs and both face the same potential problem, I leave the choice between them open for future research, especially on the processing of QR and (non-local) ACD.

Note that this sketch of analysis here does not imply that Mandarin subjects never reconstruct, but only intends to point out the possibility that Mandarin subjects might not reconstruct as far as vP.

References

Anderson, Catherine. 2004. The structure and real-time comprehension of quantifier scope ambiguity, PhD dissertation, Northwestern University.

Aoun, Joseph, and Yen-hui Audrey Li. 1993. Syntax of scope. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Aoun, Joseph, and Yen-hui Audrey Li. 2003. Essays on the representational and derivational nature of grammar: The diversity of wh-constructions. Cambridge: MIT press.

Aravind, Athulya. 2021. Successive cyclicity in DPs: Evidence from Mongolian nominalized clauses. Linguistic Inquiry 52: 377–392.

Barker, Chris. 2021. Rethinking scope islands. Linguistic Inquiry 53(4): 633–661.