Introduction

Although English speakers address all interlocutors with the same pronoun (i.e., you), independent of a person’s age or of their personal proximity with them, Spanish speakers can select from more options. For example, they may say ¿Podrías [tú] pasarme la sal? [Could you pass me the salt?] when asking a close family member to pass the salt over dinner, but might choose to say ¿Podría [usted] pasarme la sal? [Could you pass me the salt?] when requesting that a stranger at a restaurant pass the salt from their table, especially if the stranger in question is identified as older. In the first case, the request is made by using a verb form conjugated with the second person pronoun tú. In the second scenario, the request is made by using a form conjugated with the distancing pronoun usted.

It may initially seem that the distinction between tú and usted (T/V, in accordance with the Latin etymon, hereafter) is simply a matter of formality, but this is far from being true. Choosing which pronoun of address (PA) is appropriate in a given context depends on the daily linguistic uses of the speakers in that particular social setting (Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2016). Indeed, some groups of speakers may agree that tú is the natural option in a certain communicative context, whereas others may consider usted to be more appropriate in that same context. For example, many Colombian speakers may choose to use usted in daily interactions with family members, whereas most Spanish speakers would prefer tú for those contexts (Fontanella de Weinberg, Reference Fontanella de Weinberg, Bosque and Demonte1999). Speakers across the Spanish-speaking world display a multitude of varied patterns of use when it comes to these PAs, and those patterns quickly change over time (Mas Álvarez, Reference Mas Álvarez and Girao2021).

Due to the great variability in their use and to the constant changes in how speakers employ them, doubts about which PA to select in specific contexts have been repeatedly documented in second language (L2) learners of Spanish (Marsily, Reference Marsily2022; Mas Álvarez, Reference Mas Álvarez2014; Sampedro Mella & Sánchez Gutiérrez, Reference Sampedro Mella and Sánchez Gutiérrez2019; Soler-Espiauba, Reference Soler-Espiauba, Montesa and Gomis1996). However, little is known about how such difficulties vary depending on students’ L1 and on the context in which they learn Spanish. For instance, many studies so far have focused on learners of Spanish whose L1 is English, a language that does not present a T/V distinction (van Compernolle et al., Reference van Compernolle, Gomez-Laich and Weber2016; González Lloret, Reference González Lloret2008; Villareal, Reference Villarreal2014). These studies bring to light the difficulties that learners encounter when using a more complex PA system in the target language and how they adapt to the new uses throughout their learning process. For example, Villareal (Reference Villarreal2014) observed an overgeneralization of tú in intermediate-level learner’s productions, even in formal situations. González Lloret (Reference González Lloret2008) also documented alternative strategies to the use of T/V forms, such as the first-person plural pronoun nosotros [we], in the analysis of elementary Spanish learners.

Concerning the production of Spanish T/V by learners whose L1 displays a similar distinction, Granvik (Reference Granvik2005) analyzed five L1-European PortugueseFootnote 1 speakers who lived in Madrid and Marsily (Reference Marsily2022) studied 60 L1-French from Belgium in nonimmersionFootnote 2. Both authors compared native and nonnative productions and found different uses, including an overuse of usted and other polite forms in learners’ samples, probably due to a pragmatic transfer (Kasper, Reference Kasper1992) from their L1s, which often require the use of more formal pronouns. Granvik (Reference Granvik2005) highlighted as well that these deviations from L2 uses were gradually reduced when staying in immersion over a longer period. However, no study, to the best of our knowledge, has investigated in detail the specific patterns of Spanish T/V use in both French and European Portuguese speakers, or the effects of the learning context on their pragmatic uses. To address this gap, the present study explores T/V uses by L2 Spanish learners who differ along two dimensions: L1 (i.e., European Portuguese vs. French) and learning context (i.e., immersion vs. nonimmersion). The main hypothesis is thus that L1-French and L1-European Portuguese students of L2-Spanish will display pragmatic transfer from their L1 to their L2. Pragmatic transfer was defined as

the inappropriate transfer of speech act strategies from one language to another, or the transferring from the mother tongue to the target language of utterances which are semantically/syntactically equivalent, but which, because of different “interpretive bias”, tend to convey a different pragmatic force in the target language. (Thomas, Reference Thomas1983, p. 101)

The expectation is that this pattern of transfer will be stronger in students who learn Spanish in their home countries than in learners who are exposed daily to the more typical T/V uses of Spanish native speakers during a study abroad experience.

Literature Review

Formal aspects of PAs in Spanish, French, and European Portuguese

Address forms are defined as “words and phrases used for addressing” (Braun, Reference Braun1988, pp. 7–8). They provide information about a number of features related to the interlocutors (e.g., age, sociocultural level, gender), the type of relationship they share (e.g., close friends vs. distant acquaintances), and their relative social roles (e.g., boss vs. employee). Address forms concern three word classes: pronouns (e.g., tú, usted), verbs (i.e., inflectional suffixes), and nouns (e.g., doctor, mum, sir, etc.). This study focuses on verbal and pronominal expressions of the T/V distinction in Spanish. As Spanish is a pro-drop language, subject pronouns do not need to be expressed and the information about the person is to be found in verbs’ inflectional endings, which correspond with the pronouns (e.g., [tú] come [eat, in the imperative], [usted] coma [eat, in the imperative]).

In Spanish, French, and European Portuguese, second person (2P) pronoun systems are grammatically similar due to their common Latin origin. Singular pronouns tu/tú accompany conjugated verbs that follow the typical inflectional paradigm of the 2P, but the other singular pronouns—namely usted in Spanish, você in Portuguese, and vous in French—present a different pattern: usted and você accompany conjugated verbs that follow the third person singular paradigm (3P sg.), and vous follows the second plural person paradigm (2P pl.). The common Latin etymon of these latter forms, vos, originally corresponded with a 2P pl. pronoun in Latin. In the Middle Ages, the pronoun vos was used to address an individual in a formal way in contrast to tu, which was used for informal situations. Although French maintained this system, Spanish and Portuguese presented a shift during this period. As a result, some nominal forms from the pronoun vos were created in the XV century: Vuestra Merced in Spanish and Vossa Mercê in Portuguese. As these were nominal forms, they were conjugated in the 3P sg. but used to address a 2P sg. in a highly formal way. Eventually, these composed forms turned into usted and você and maintained the 3P pl. inflection (see De Jonge & Nieuwenhuijsen, Reference De Jonge, Nieuwenhuijsen and Company2006, and Lennertz Marcotulio, Reference Lennertz Marcotulio2014, for further information about the Spanish evolution of usted and the Portuguese evolution of você, respectively).

As evidenced in Table 1, European Portuguese presents an additional set of forms of address (i.e., o senhor [the male person]/a senhora [the female person]), which serve to conjugate verbs in a way identical to the 3P sg. você. These nominal forms convey an even greater distance between the interlocutors than você and mark gender distinctions (i.e., o senhor for masculine, a senhora for feminine).

Table 1. 2P pronoun systems in Castilian Spanish, French, and European Portuguese

Patterns of PA use in Spanish, French, and European Portuguese

In spite of the existence of relatively similar T/V forms, PA use differs across the three languages. Politeness and cross-cultural pragmatics studies (Briz, Reference Briz2007; Haverkate, Reference Haverkate2004; Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2019) have shown that some cultures, such as the Spanish, focus on proximity and solidarity between participants and thus tend to use more positive politeness forms like imperatives, compliments, nicknames, or jokes (Brown & Levinson, Reference Brown and Levinson1987). Other cultures, such as the French or Portuguese, tend to use more mitigation strategies as well as negative politeness forms including conditional sentences, apologies, modal verbs, indirect forms, etc. to show greater distance and formality (Brown & Levinson, Reference Brown and Levinson1987). Such differences directly affect PA use in the languages spoken in those cultures, as was demonstrated in Brown and Gilman’s (Reference Brown, Gilman and Sebeok1960) seminal article where they compared German, French, and Italian social norms and their respective uses of T/V. These authors found that increased uses of T in the Italian language were related to a social preference for symmetrical social relationships and the valorization of interpersonal solidarity. In French and German, alternatively, the importance given to the identification of power structures and the ensuing need to establish hierarchies between collocutors resulted in a predominant use of V over T.

As expected based on these findings, in FrenchFootnote 3 and in European Portuguese, the use of 3P distancing forms (i.e., vous and o senhor/a senhora) is more generalized than in Castilian Spanish (see sections below). Although in European Portuguese and French the unmarked form is the 3PFootnote 4 (Cook, Reference Cook1997; Hammermüller, Reference Hammermüller1993; Hughson, Reference Hughson2003; Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Reference Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Hickey and Stewart2005; Maingueneau, Reference Maingueneau1994), in Spanish it is the 2P (Carrasco Santana, Reference Carrasco Santana2002; Hickey & Vázquez Orta, Reference Hickey and Vázquez Orta1990; Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2016, Reference Sampedro Mella2022).

In reference to French, Kerbrat-Orecchioni (Reference Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Hickey and Stewart2005) underlines that the use of V is greater in France than in most neighboring countries where Romance languages are spoken. Coveney (Reference Coveney2010, p. 138) adds to this line of thinking when stating that “one can readily accept that V is ‘unmarked’ in the sense that most French people opt for T only if they are addressing an adult belonging to their network of family, friends and colleague—and even then, not all of these.” However, he also recognizes that “reciprocal T is normal among children, adolescents and often—though not universally—students” (2010, p. 139). Concerning European Portuguese, most authors point to the hierarchical organization of Portuguese society (Aldina Marques, Reference Aldina Marques2010; Araújo Carreira, Reference Araújo Carreira2003; Cintra, Reference Cintra1986/1972; Lennertz Marcotulio, Reference Lennertz Marcotulio2014) to explain the extended use of distancing nominal forms, or forms of reverence (e.g., o senhor, o senhor doutor, a senhora dona Ana, Vossa Excelência). In this highly hierarchical context, the use of the 2P tu is limited to very intimate contexts.

As was mentioned earlier, in Castilian Spanish, the 2P tú is the unmarked address form (Carrasco Santana, Reference Carrasco Santana2002; Hickey & Vázquez Orta, Reference Hickey and Vázquez Orta1990; Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2016, Reference Sampedro Mella2022), and the use of usted has been steadily declining since the 70s (Alba de Diego & Sánchez Lobato, Reference Alba de Diego and Sánchez Lobato1980; Aguado Candanedo, Reference Aguado Candanedo1981 Borrego et al., Reference Borrego, Gómez Asencio and Pérez Bowie1978). In this respect, more recent studies have confirmed that the use of tú in Spain is now spreading to communicative contexts where speakers used to prefer usted not long ago, such as service encounters or teacher–student interactions (Blas Arroyo, Reference Blas Arroyo and Arroyo1998; Molina Martos, Reference Molina Martos and Rodríguez González2002; Sanromán, Reference Sanromán2006). There is no consensus among researchers to explain this change in favor of tú, but some historical events have been associated with this trend, such as the presence of an equality police during the Second Republic in the 30s (Alonso, Reference Alonso and Alonso1968; Hickey & Vázquez Orta, Reference Hickey and Vázquez Orta1990; Molina Martos, Reference Molina Martos and Rodríguez González2002), the end of World War II (Alba de Diego & Sánchez Lobato, Reference Alba de Diego and Sánchez Lobato1980; Brown & Gilman, Reference Brown, Gilman and Sebeok1960), or the transition to democracy after Franco’s dictatorship in the late 70s (Aguado Candanedo, Reference Aguado Candanedo1981).

PA use in Castilian Spanish

Choosing T/V forms depends on some variables related to both the speaker and the hearer. In Castilian Spanish, specifically, most studies agree on placing the age of the interlocutor as the first and most relevant variable to take into account when making decisions about which PA to use (Aguado Candanedo, Reference Aguado Candanedo1981; Alba de Diego & Sánchez Lobato, Reference Alba de Diego and Sánchez Lobato1980; Borrego et al., Reference Borrego, Gómez Asencio and Pérez Bowie1978; Molina Martos, Reference Molina Martos and Rodríguez González2002; Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2016). According to these studies, this variable is closely followed, in terms of its relevance, by the sociocultural level of the addressee. Concretely, the use of usted is related to the older age and higher status of the person being addressed, whereas tú is associated with younger interlocutors whose sociocultural status is considered to be lower by the speaker. In cases where age and sociocultural level come into conflict, such as when an interlocutor is older but also has a lower sociocultural status, age will be the most relevant variable in deciding whether to use tú or usted (Aguado Candanedo, Reference Aguado Candanedo1981; Borrego et al., Reference Borrego, Gómez Asencio and Pérez Bowie1978; Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2016, Reference Sampedro Mella2022). Additionally, some researchers have found that the gender of the addressee may also come into play when deciding whether to use tú or usted. For instance, in Schwenter (Reference Schwenter1993) or Sampedro Mella (Reference Sampedro Mella2016), women tended to be addressed more often as tú, whereas men tended to more often be addressed as usted. However, these findings have not been corroborated by other studies where no differences were found when comparing T/V uses when addressing women or men (Aguado Candanedo, Reference Aguado Candanedo1981; Borrego et al., Reference Borrego, Gómez Asencio and Pérez Bowie1978; Sanromán, Reference Sanromán2006).

As for other variables that are related to the context of communication such as the formality of the situation, the hierarchical relations between the collocutors in that specific context, or the level of interpersonal proximity between participants, these have tended to be studied separately (Alba de Diego & Sánchez Lobato, Reference Alba de Diego and Sánchez Lobato1980; Blas Arroyo, Reference Blas Arroyo and Arroyo1998; Molina Martos, Reference Molina Martos and Rodríguez González2002; Sanromán, Reference Sanromán2006; Schwenter, Reference Schwenter1993), resulting in a lack of clarity when it comes to establishing which of these variables has the strongest influence on PA selection. However, the literature has consistently confirmed the relevance of personal proximity on the use of tú in that this pronoun is often preferred when addressing someone close to the speaker, such as a friend or family member. Alternatively, situations that are seen as highly formal, especially when addressing a person who is considered as being higher in the hierarchy and/or is unknown to the speaker, will trigger the use of usted more often.

PA use in French

The usage of 2P pronouns in France underwent significant changes throughout the history of the nation, especially following the French Revolution or the sexual revolution, both of which changed the social structure of the country. However, in spite of these changes, the unmarked PA in contemporary French is still vous. The use of tu is still limited to the counted situations where social factors related to the hearer (e.g., age, gender, status, etc.) or the relationship type (e.g., family, friends, close people, etc.) make it appropriate.

Overall, the literature on French T/V tends to relate the use of tu with the lower age of the interlocutor (Bustin-Lekeu Reference Bustin-Lekeu1973, Gardner-Chloros, Reference Gardner-Chloros1991; Guigo, Reference Guigo1991; Havu, Reference Havu2006) such that younger people are more often addressed as tu than older people. Other variables such as the relationship between the participants and the roles played by the collocutors are also important in PA choice (Havu, Reference Havu2006; Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Reference Kerbrat-Orecchioni1992). Alternatively, the sociocultural level and gender of the interlocutor seem to not have the same influence as in Castilian Spanish (Isosävi, Reference Isosävi2010). Finally, several cases remain where native speakers of French doubt in choosing between tu and vous in French (Havu, Reference Havu2005). For instance, when addressing a younger hearer who holds a superior position at one’s job, the competition between the age variable, which would indicate that tu should be used, and the variable related to the hierarchical position, which would favor vous, would result in opposed T/V decisions in L1 French speakers.

PA use in European Portuguese

The PA system in European Portuguese is more complex due to the presence of three alternatives: tu, você, and nominal forms (i.e., o senhor, a senhora doutora), with the latter expressing even more distance and hierarchy than você (Paiva Raposo et al., Reference Paiva Raposo, Bacelar do Nascimento, Coelho da Mota, Segura, Mendes and Andrade2020). The pronoun você is thus used as an intermediate form between tu and o senhor/a senhora (Guillerme & Lara Bermejo, Reference Guillerme and Lara Bermejo2015), and it has many different uses in speech, depending on contexts and geographical areas (see Guillerme & Lara Bermejo, Reference Guillerme and Lara Bermejo2015, or Hammermüller, Reference Hammermüller1993, for more information).

In European Portuguese, variables related to the social context, such as formality (Cook, Reference Cook1997; Duarte, Reference Duarte and Brito2010; Hammermüller, Reference Hammermüller1993), hierarchy (Araújo Carreira, Reference Araújo Carreira2003; Aldina Marques, Reference Aldina Marques2010; Cintra, Reference Cintra1986/1972; Lennertz Marcotulio, Reference Lennertz Marcotulio2014), or personal closeness (Duarte, Reference Duarte and Brito2010) drive PA choices. Previous studies have also pointed to the influence of the interlocutor’s gender, age, and socioeconomic status (Aldina Marques, Reference Aldina Marques2010; Duarte, Reference Duarte and Brito2010; Thomé-Williams, Reference Thomé-Williams2004). In this respect, a man, an elderly person, or an individual with a high sociocultural status would more often be addressed with a 3P form than a woman, a young person, and/or an individual with a lower sociocultural status.

Communicative misunderstandings when using PAs

Although many of the variables that affect PA choice in the three languages are common, some cultural differences (i.e., proximity in Spain vs. distance in France and Portugal) and how much importance is given to each variable may create misunderstandings caused by pragmatic transfer, or “pragmatic failure” (Thomas, Reference Thomas1983, p. 91). For instance, because the age of the interlocutor is perceived as the primary factor to use usted in Castilian Spanish, being addressed as usted tends to be interpreted as a sign that the speaker considers you to be old, as stated by the RAE & ASALE (2011):

El uso de usted puede hacer sentir incómodo al interlocutor si, en lugar de como forma de respeto, se interpreta como medio para marcar distancia o como señal de que se considera persona de edad. [the use of usted can make the interlocutor feel uncomfortable if, instead of a sign of respect, it is interpreted as a mark of distance or an indication that the speaker believes that the interlocutor is old]. (p. 322)

In this context, L2 learners from Portugal or France may easily and completely involuntarily commit communicative mishaps when overusing the 3P in Spanish by transferring the patterns of their L1s, either as an acknowledgment of the perceived hierarchical superiority of the addressee, or as an indication of formality and politeness. Thus, although intending to show respect, they may actually make the interlocutor feel somewhat annoyed if the use of usted is viewed as a sign that the person considers them an older person. To avoid such situations, it is important for Spanish L2 learners to know how Spanish T/V use differs from that of their L1.

PA in L2 Spanish teaching

Given the multiple variables that need to be taken into account when deciding which PA to use, the inherent variability in T/V use across communities of speakers, and possible mismatches between the students’ L1 and L2, research has shown that appropriately using these forms in L2 Spanish is far from easy for many learners (Marsily, Reference Marsily2022; Más Álvarez, Reference Mas Álvarez2014; Navarro Gala, Reference Navarro Gala, Zorraquino and Pelegrín2000; Ramos-González & Rico-Martín, Reference Ramos-González and Rico-Martín2014). Consequently, researchers have called for more attention to the teaching of PAs in L2 Spanish. For instance, Soler-Espiauba (Reference Soler-Espiauba, Montesa and Gomis1996) emphasized that the complex dynamics that underlie PA selection can only be addressed through explicit instruction and adequate and repeated practice with specific activities that tap into the influential variables involved in PA choice in different contexts.

Despite the increased use of communicative language teaching or task-based language teaching in Europe, which are promoted by the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001, 2020) and seek to develop students’ communication skills, L2 Spanish textbooks in Europe still often dismiss pragmatic matters, such as T/V uses (Más Álvarez, Reference Mas Álvarez2014, Reference Mas Álvarez and Girao2021; Navarro Gala, Reference Navarro Gala, Zorraquino and Pelegrín2000; Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2016). This is illustrated in Sampedro Mella & Sánchez Gutiérrez (Reference Sampedro Mella and Sánchez Gutiérrez2019), who analyzed 15 beginner L2 Spanish textbooks and found that only 13.3% included an adequate approach for teaching T/V. Most books in their study (53.3%) did not include any reference to T/V uses, and 33.3% introduced a brief mention to how tú and usted are not used in the same contexts but limited their explanations to stating that tú should be used in informal settings and usted should in more formal ones. No specific description was provided of the variables that determine whether a communicative context is formal or informal. More importantly in the case of Castilian Spanish, no mentions were ever made to the fact that tú is more used than usted or that usted can be interpreted as an indicator of the older age of the interlocutor.

L2 Spanish use of forms of address during study abroad

Due to the limited attention given to pragmatics, which importantly includes PAs, in explicit Spanish language teaching, study abroad (SA) has been seen as a means of addressing such gaps and complementing language learners’ education. Indeed, researchers have looked into the effects of participating in SA programs on the use of more locally appropriate norms when performing specific speech acts, especially requests, apologies, and compliments (Bataller, Reference Bataller2010; Cohen & Shively, Reference Cohen and Shively2007; DiBartolomeo et al., Reference DiBartolomeo, Elias and Jung2019; Félix-Brasdefer & Hasler-Barker, Reference Félix-Brasdefer and Hasler-Barker2015; Hernández, Reference Hernández2018; Hernández & Boero, Reference Hernández and Boero2018; Shively, Reference Shively2011), Findings indicate that SA contributes to achieving such goals, but many studies insist that learners’ incidental exposure to relevant input while abroad may not be sufficient and recommend the inclusion of explicit classroom-based pragmatic treatments, either pre-SA or during SA (Morris, Reference Morris2017). This need for additional explicit teaching may be observed because most research was carried out with students who participated in “sheltered” SA programs, where learners complete courses with peers and instructors from their home institution. In this type of program, extensive interaction with native speakers is not guaranteed and greatly depends on the goals, positioning, and investment of the individual learners (Quan, Reference Quan2019).

In the specific context of the L2 development of T/V distinctions, Kinginger and Farrell (Reference Kinginger and Farrell2004, p. 24) stated that “address form competence is as much a matter of language socialization as it is of acquisition,” pointing to the importance that repeated meaningful social interactions may have in adopting local norms of PA use. Therefore, the fact that some studies did not find significant change in the use of Spanish T/V during SA (Shively, Reference Shively2011) may result from the limited opportunities for meaningful socialization offered by sheltered SA programs as well as the relatively short length of such programs (i.e., typically between four and 14 weeks). In the present study, participants of both L1-French and L1-European Portuguese who were in a linguistic immersion context lived in a small city in Spain, without the support of a group from their home country or university, and were enrolled in academic programs at the local public university. Additionally, they had already stayed in Spain for a minimum of six months, but generally longer, and were studying advanced language-related majors, probably resulting in a more advanced proficiency than that of the participants in most SA studies related to T/V uses so far.

Objectives and research questions

Although French and European Portuguese display a T/V distinction, as does Spanish, the frequency of use of both PAs, as well as the variables that determine their use, are different from the patterns in Spanish. In this context, it is important to investigate whether those L1 patterns appear in the L2’s T/V use and, if so, whether said patterns change when learners are in an immersive educational context. This study analyzes Spanish T/V uses by L1-French and L1-European Portuguese learners of Spanish who are studying their L2 either in their home country, a nonimmersive context, or in Spain, an immersive context. The objective of this design is to respond to the following research questions:

-

1. Do L1-French and L1-European Portuguese learners of Spanish present different frequency patterns in their use of T/V in their L2 when participating in an educational immersive experience in Spain compared with students who learn the language in their home countries?

-

2. What variables influence T/V choice in L1-French and L1-European Portuguese learners of L2-Spanish when they learn the language at home versus during an immersive educational experience in Spain?

Methods

Participants

A total of 168 learners of L2 Spanish, 27 men and 141 women, participated in this study. Of these, 87 were French speakers, with 39 being in an immersive context in Spain and 46 in a nonimmersive context in France. The remaining 81 participants were L1-European Portuguese speakers, of whom 35 were in Spain at the time of testing and 48 in Portugal. Participants’ age ranged between 22 and 24 years old. All participants had been enrolled in formal Spanish language instruction for a minimum of 4 years and were completing university majors in Spanish, translation, or linguistics. Although we cannot attest to their proficiency based on the results of a test, all participants were enrolled in classes taught fully in Spanish and that required an advanced command of academic Spanish to be able to complete the coursework. All learners in the immersion group were participating in SA programs in Salamanca, Spain, which lasted at least 6 months. These programs were completed individually in that students were not part of a group that traveled together from their home country. They were all enrolled in university programs that focused on linguistics or translation, just as their counterparts at home.

Twenty-five L1-Spanish speakers from Salamanca also participated in the study. This group was composed of five men and 20 women between the ages of 20 and 24 years old who were completing a Spanish major at the University of Salamanca. Therefore, these speakers shared a similar age range, were enrolled in similar programs, and lived in the same city as the L2-Spanish learners in immersion.

Testing materials

Participants completed a Discourse Completion Test (DCT; Cyluk, Reference Cyluk2013; Nurani, Reference Nurani2009) and a demographic questionnaire. The demographic questionnaire included a series of questions that gathered information about their age, gender, academic background, nationality, and general linguistic background (i.e., L1, L2, length of stay in Spain, length of study of L2 Spanish).

A DCT is a “written questionnaire containing short descriptions of a particular situation intended to reveal the pattern of a speech act being studied” (Kasper & Dahl, Reference Kasper and Dahl1991 as cited in Nurani, Reference Nurani2009, pp. 667–668). DCTs have been broadly used in empirical investigations related to pragmatic competence (Ivanovska et al., Reference Ivanovska, Kusevska, Daskalovska and Ulanska2016; Nurani, Reference Nurani2009) as well as in L1 and L2 contrastive studies (Blum-Kulka & Olshtain, Reference Blum-Kulka and Olshtain1984; Cohen & Olshtain, Reference Cohen and Olshtain1981). Although natural data, as that found in corpora, provides more direct and realistic measures of speakers’ linguistic practices, elicitation tasks such as DCTs, oral DCTs, and role plays also have their advantages (Bataller, Reference Bataller2013; Félix-Brasdefer, Reference Félix-Brasdefer2007; Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2021). Indeed, these types of tasks offer a systematic approach to both data collection and data analysis processes. Unlike speech corpora, DCT data uniquely tap into the variables of interest and allow for the collection and comparison of larger amounts of data under controlled conditions. Because all participants respond to the same questionnaire with identical elicitation tasks, no other contextual variables can affect the results. Among elicitation tasks, although role plays provide results that may be closer to natural data (cf. Félix-Brasdefer, Reference Félix-Brasdefer2007), they are limited in the number of different scenarios that can be covered with each participant. Therefore, in this study, the DCT was selected as the most appropriate method, as it allows to combine a wide range of situations in different scenarios and makes it possible to include more participants in a shorter time, which results in the collection and comparison of a larger amount of data.

The items included in this study’s DCT were created ad hoc, with the intention of obtaining answers that included tú, usted, or a verbal inflectional form corresponding to either tú or usted. Each of the 16 situations described in the DCT tapped into one or more sociolinguistic variables that are known to influence L1-Castilian Spanish speakers’ T/V decisions (see Table 2).

Table 2. Variables considered in the DCT questionnaire

Examples 1 and 2 illustrate the type of items included in the test. In example 1, the variables of interest are the age (old) and gender (woman) of the interlocutor as well as the degree of familiarity with the speaker (known) and the formality of the situation (informal). In example 2, the variables of interest are the relative social status (high) and the gender (man) of the hearer, the relationship between participants (unknown), and the formality of the situation (formal). The complete test can be found in Appendix 1.

Example 1. Encuentras a tu vecina, una mujer mayor, cargada con bolsas y decides ofrecerle tu ayuda, ¿qué le dices?

[You run into your neighbor, an elderly woman, loaded with bags and you decide to offer to help her, what do you tell her?]

Example 2. Has faltado al trabajo porque estás enfermo. Pídele al médico que te ha atendido en el hospital, que te firme un justificante.

[You have missed work because you are sick. Ask the doctor who examined you at the hospital to sign a doctor’s note.]

As evidenced in these examples, the variables were considered as binary: young versus old, low versus high social status, formal versus informal situation, etc. Although these variables always appear in each item of the DCT, not all items include explicit information about all the variables. For instance, in Example 1, no explicit information is given about the sociocultural level of the interlocutor and, in Example 2, the same occurs with the age of the interlocutor. The lack of this explicit information is also used to analyze the T/V choices in these situations. This design decision was made because there are situations in real life where some relevant information about the interlocutor may be missing, such as when one talks with an unknown person, and other situations where one may be unsure about the age or social status of the people we address. In those circumstances, speakers still need to decide whether to use tú or usted. Therefore, including some items that do not explicitly offer details about certain variables is important to study what learners of L2-Spanish do when they are unsure about someone’s age or someone’s social status. Do they default to tú or to usted?

Procedures

One of the researchers carried out all data collection efforts at the three universities where participants were recruited in order to ensure that all data were collected in the exact same way. Participants completed the demographic questionnaire and the DCT during normal class time without a time limit. On average, participants took 20–30 min to complete the questionnaire. They were asked to respond in Spanish and were not informed of the goal of the research until the survey was completed by all participants in order to avoid response biases.

Results

Data processing

The data collected from the DCT was processed in Microsoft Excel, where the PAs used by each participant in response to each item were tallied. Although participants almost always used a PA in their responses, some of them revealed other structures that did not require any PA, such as impersonal sentences. Additionally, some utterances included both tú and usted. All the address forms collected were classified under five categories: (1) tú, (2) usted, (3) neither tú nor usted (i.e., use of alternative linguistic structures), (4) tú and usted (i.e., both tú and usted in the same utterance), and (5) no response (i.e., empty or completely unrelated answers that were not analyzed).

Examples of responses that would fit in category 3 (i.e., neither tú nor usted) would be Necesito un justificante para mi trabajo [I need a doctor’s note for my work] or ¿Hay más cuadernos? [Are there any more notebooks?]. In both cases, the participant avoided using a PA and used alternative linguistic resources to ask a question or make a request. Cases like Perdone, ¿podrías limpiar el suelo delante de mi puerta? [(Usted) excuse me, could you (tú) clean the floor in front of my door?] were included in category 4, since both tú and usted were used to address the same person.

Amount and context of use of tú and usted in immersion versus nonimmersion contexts

To address Research Question 1, Table 3 presents the distribution of response types in each participant group (i.e., L1-French immersion, L1-French nonimmersion, L1-Portuguese immersion, L1-Portuguese nonimmersion, native speakers). In addition to this descriptive information, Table 4 presents the results of a binomial linear regression where only L2-learners’ responses that included either tú or usted are used in order to assess whether the choice of one or the other varies according to two independent variables: (1) L1 (i.e., French vs. European Portuguese) and (2) immersion context (i.e., immersion vs. nonimmersion). In the model, usted is used as the reference level.

Table 3. Response types by total participants in each group

Table 4. Parameter estimates and derived values from the linear regression model T/V ~ L1 × Context

When looking at the percentages of PA use in both L1 groups, 31.1% of L1-French learners use tú, but only 17.3% of L1-European Portuguese learners do when learning the language in their home country. In both L1 groups, learners in immersion display a great increase in their use of tú and a decrease in their use of usted compared with their L1-counterparts who were studying Spanish in their home countries. However, their use of tú is still much lower than that of the native speakers, even after several months of immersion.

The model presented in Table 4 confirms the trends observed in Table 3. First, it reveals a significant main effect of L1, with L1-European Portuguese learners using usted significantly more often than L1-French learners. Second, a main effect of immersion was also found, showing that learners in an immersion context display a significantly greater use of tú. Finally, the interaction between language and immersion also reached significance. Concretely, the difference in the use of tú in the immersion group, as compared with the nonimmersion one, was significantly greater for L1-European Portuguese learners than for L1-French learners, pointing to a potentially greater effect of immersion on the former.

Because learners’ responses (i.e., tú, usted, neither tú nor usted, tú and usted, no response) form a categorical variable, it was not possible to include more than two levels (i.e., tú vs. usted) in the dependent variable of the regression model. However, the evolution of mixed responses (i.e., when learners use both tú and usted in the same utterance) in the descriptive statistics presented in Table 3 also reveals interesting trends. Indeed, both L1-French and L1-European Portuguese learners in an immersion context presented a greater proportion of mixed uses than their counterparts at home, which indicates that they may become more doubtful about their PA choices as they are exposed to native speakers of Castilian Spanish who use the T/V distinction in ways that differ from their L1.

When it comes to determining which situations trigger such doubts, an analysis of some illustrative DCT items reveals relevant patterns. For instance, both L1-French and L1-European Portuguese learners in immersion seem to hesitate between tú and usted when they do not know the age and sociocultural level of the hearer. For example, in Item 5, participants are asked to address an unknown man in the street. As evidenced in Table 5, for this item, 20% of French and 10.3% of Portuguese participants in immersion, as opposed to 4.2% of French and 6.5% of Portuguese in nonimmersion, use both tú and usted in the same statement.

Table 5. Example of the use of address forms with an unknown interlocutor (Item 5)

In addition to this trend observed in learners of both L1s, L1-French speakers in immersion seem particularly unsure about their PA choices when they address a person whom they already know but whom they consider to have a lower sociocultural status. This hesitation does not seem to appear in the L1-European Portuguese data in either immersion or nonimmersion. Table 6 provides a comparison of two items from the DCT that have a common interlocutor: a salesclerk at the market. In Item 7, the salesclerk is a person the speaker would know, whereas in Item 1 they are not previously known by the speaker. An analysis of the responses to these two items reveals that L1-French participants use usted more often with a clerk they do not know, whereas they prefer using tú with a salesclerk with whom they share greater familiarity. In immersion, however, L1-French learners seem to feel more insecure in using a specific PA with the clerk they already know, as evidenced by a lower frequency of mixed responses at home (2.1%) than in immersion (17.1%).

Table 6. 1 by L1-French learners and native speakers

In the case of European Portuguese speakers, they tend to hesitate more than the French and their doubts seem to be greater while in immersion than in nonimmersion, especially when addressing women whom they consider to have a high sociocultural status. The answers to Items 9 and 12, where they address a female doctor and a young female eye doctor, respectively, clearly illustrate these doubts with high-status women, as evidenced in Table 7. However, when addressing a man with a higher status, European Portuguese speakers tend to use usted more often and do not hesitate as much, except if the man in question is younger (e.g., Item 3). Indeed, in addressing a young male human resources officer, L1-European Portuguese learners used both tú and usted in the same utterance 10.3% of the time when in immersion and only 2.2% of the time while learning Spanish at home.

Table 7. Responses to Items 9, 12, and 3 by L1-Portuguese learners and native speakers

Overall, it seems that great mismatches between L2-learners’ and L1-speakers’ uses result in more doubt for learners who are in immersion. In most of these items, native speakers show a clear preference for the T form and learners in nonimmersion greatly favor the V form. Thus, it is not surprising that learners who are exposed to this completely opposite set of T/V uses in Spain may need some time to adjust and hesitate between their L1 tendency of using V and the newly discovered Spanish preference for T in certain specific situations.

Variables influencing the use of tú in different groups

To further explore the variables that influence PA choices in the different groups of learners who participated in this study, the next sections present a series of five logistic regression models for each one of the groups (i.e., L1-Spanish speakers, L1-French immersion, L1-French nonimmersion, L1-European Portuguese immersion, L1-European Portuguese nonimmersion). It was impossible to include all groups in a single model due to lack of power, which explains the multitude of models.

All models include the same set of predictors:

-

- Age of the interlocutor (young, old, unspecified)

-

- Sociocultural level of the interlocutor (high, low, unspecified)

-

- Gender of the interlocutor (male vs. female)

-

- Formality of the situation (formal vs. informal)

-

- Familiarity with the interlocutor (known vs. unknown person)

In all five of the models, the dependent variable is the proportion of uses of tú, as it is the default PA in Spanish but not in European Portuguese and French. The goal is thus to observe whether the uses of tú, which were significantly greater for learners in immersion contexts, are also better adjusted to variables known to be decisive in L1-Spanish. Concretely, what variables are they taking into account when deciding to use tú while in immersion? How do these variables differ from the ones used to make T/V decisions by students who are not in a linguistic immersion context?

Variables influencing the uses of tú in L1 speakers of Spanish

In the case of the L1 speakers of Spanish, as evidenced in Table 8, all predictors reached significance, with increased uses of tú being associated with the younger age of the interlocutor, the fact that the interlocutor is a woman, that the situation is informal, and that the interlocutor is a known person. When it comes to the effect of the sociocultural level of the interlocutor, speakers tend to increase their use of tú when they know the person they are addressing has a lower sociocultural level and decrease their use of tú when they do not have that information. Using the model’s parameter estimates as unstandardized effect sizes, age is the most influential variable in deciding to use tú, followed by familiarity and sociocultural level (only the unspecified-low pair) and finally by formality and gender. This confirms the previously mentioned finding in the literature that the age of the interlocutor is the main predictor of T/V decisions in Castilian Spanish and that the effects of formality and gender are generally less conclusive.

Table 8. Parameter estimates and derived values from the logistic regression models tú ~ gender ~ age ~ formality ~ sociocultural level ~ familiarity of the Spanish native speakers

Variables influencing the uses of tú in L1-French L2-Spanish learners

As can be observed in Table 9, no predictor reaches significance in L1-French learners in a nonimmersion context even though age, formality, and sociocultural level present marginally significant results. Concretely, L1-French learners in France tend to use tú more often with younger people, in informal contexts, and with people who they identify as having a lower sociocultural level. In learners who are in an immersion context in Spain, the effect of the interlocutor’s sociocultural level reaches statistical significance, as they use tú more often, not only when the person is known to have a lower sociocultural level, but also when they are unsure about the person’s sociocultural level. Age, however, does not reach significance in any of the two groups of L1-French speakers. Finally, it needs to be noted that the R 2 values of these models are relatively low, with the immersion model being the one that explains the most variance, at approximately 10%. This indicates that there are probably more variables that are influencing L1-French learners’ decision making when they choose to use tú.

Table 9. Parameter estimates and derived values from the logistic regression models tú ~ gender ~ age ~ formality ~ sociocultural level ~ familiarity (model on the left: French + nonimmersion; model on the right: French + immersion)

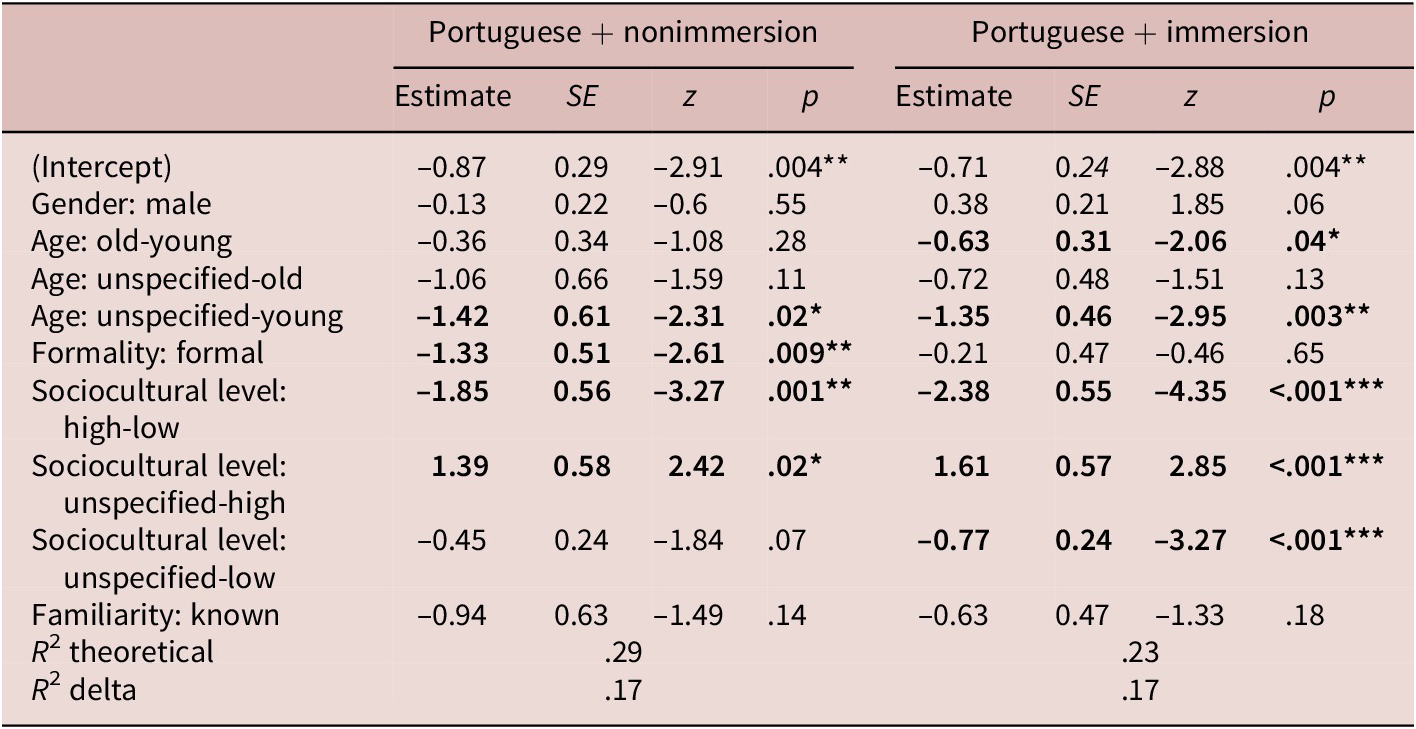

Variables influencing the uses of tú in L1-European Portuguese L2-Spanish learners

As evidenced in Table 10 above, L1-European Portuguese learners of L2-Spanish who are in a nonimmersion context tend to associate the use of tú with informal situations and with the lower sociocultural level of the interlocutor. Speakers also take into account the age of the person they are addressing and they pay attention to the level of formality required by the specific situation at hand. In the case of L1-Portuguese learners in the immersion group, age and sociocultural level remain significant predictors of the use of tú, with younger people with a lower sociocultural status being addressed more often with tú. Alternatively, formality, a variable that reached significance but was not as relevant as age in the native speakers’ model, is not a significant predictor in the immersion model. Both in the immersion and the nonimmersion models, the R 2 is around .20, indicating a medium effect size.

Table 10. Parameter estimates and derived values from the logistic regression models tú ~ gender ~ age ~ formality ~ sociocultural level ~ familiarity (model on the left: Portuguese + nonimmersion; model on the right: Portuguese + immersion)

Discussion

Some linguistic varieties, like Castilian Spanish, are known to focus on proximity and solidarity, using positive politeness forms, whereas others, like French, focus on negative politeness forms, seeking to ensure some distance between the speaker and the hearer in order to show respect (Briz, Reference Briz2007; Haverkate, Reference Haverkate2004; Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2019). Therefore, even though Castilian Spanish, French, and European Portuguese all present a T/V distinction, the distribution and use of such forms greatly varies, with the T form representing the default in Castilian Spanish (Carrasco Santana, Reference Carrasco Santana2002; Hickey & Vázquez Orta, Reference Hickey and Vázquez Orta1990; Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2016, Reference Sampedro Mella2022) and V forms being favored in most situations by speakers of French (Hughson, Reference Hughson2003; Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Reference Kerbrat-Orecchioni, Hickey and Stewart2005; Maingueneau, Reference Maingueneau1994) and European Portuguese (Cook, Reference Cook1997; Guillerme & Lara Bermejo, Reference Guillerme and Lara Bermejo2015; Hammermüller, Reference Hammermüller1993). In sum, although Spanish speakers generally default to tú, French speakers most often use vous, and Portuguese display a broader array of respect forms with the use of nominal forms, such as o senhor/a senhora, thus presenting the greatest attention to politeness and distance of the three groups.

These differences between the L1s were reflected in participants’ frequency of use of T/V forms in Spanish when they were learning Spanish in their home countries, revealing instances of pragmatic transfer (Kasper, Reference Kasper1992). Specifically, L1-European Portuguese learners used usted significantly more often than L1-French speakers. In both L1 groups, however, learners in immersion used usted less often than those in nonimmersion and chose to use tú in more situations, which better conforms to the T/V frequencies in the L1-Spanish group. Interestingly, the immersive context of living in Spain not only played a role in developing more native-like frequencies of use of tú and usted but also seemed to sow doubt for some learners when deciding which PA to use in certain contexts. For example, L1-French participants in immersion presented significantly more mixed uses of tú and usted when addressing a salesclerk they knew than did L1-French learners in France. This may be due to the fact that, in France, they would systematically use vous in the context of a service encounter, whereas Spaniards would consistently use tú, presenting a great mismatch between L1 and L2 pragmatic practices. Overall, our data suggest that, when discrepancies between the forms preferred in the L1 and the L2 in a given situation are notable, learners experience greater insecurity in PA choice in that situation when they are immersed in the L2 context. Such doubts seem to reflect a normal step in the process of adopting, and adapting to, new pragmatic uses that do not correspond to the L1.

It is important to note that mixed uses of tú and usted in the same utterance also appeared in the responses of the L1-Spanish group, which is not surprising because similar cases have been documented in Spain (Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2016, Reference Sampedro Mella2022), in Argentina with the pronouns vos and usted (Rigatuso, Reference Rigatuso2014), and in Colombia (Denbaum, Reference Denbaum2021) or Costa Rica (Quesada Pacheco, Reference Quesada Pacheco, Hummel, Kluge and Vázquez2010) with tú, vos, and usted. In the literature, such mixed uses by L1-speakers are known as polymorphism (Denbaum, Reference Denbaum2021), alternancia [alternation] (Sampedro Mella, Reference Sampedro Mella2022), cambio momentáneo [momentary change] (Rigatuso, Reference Rigatuso2014), or danza pronominal [pronominal dance] (Quesada Pacheco, Reference Quesada Pacheco, Hummel, Kluge and Vázquez2010). When multiple variables need to be taken into account at once and each may lead to competing and sometimes contradictory options, speakers, native or not, may proceed to mix both PAs. In the case of L2-learners, the influence of the L1 and the resulting pragmatic transfer add another level of complexity to the already intricate decision-making process of choosing context-appropriate forms of address. Therefore, although some mixed T/V uses can be considered as linguistic mistakes, as was found in previous studies (Marsily, Reference Marsily2022), most T/V hesitations, especially in immersion, seem to be an indication of learners’ realization of the complexity of the PA system (including cases of polymorphism) and, consequently, a positive step in their development of L1-Spanish patterns.

When it comes to the variables that better predicted the use of tú in the different groups of participants, it is notable that none of them seemed to play a predominant role in the nonimmersion L1-French group. Although formality, age, and sociocultural level were marginally significant in that model, no variable actually reached significance. In the case of the L1-French learners who had been living in Spain for a few months, the sociocultural level of the interlocutor became the decisive factor for choosing tú over usted, most often addressing people who were identified as having a lower sociocultural status with tú. However, the age of the interlocutor, which was the most predictive variable in the L1-Spanish group, was not a significant predictor either in immersion or in nonimmersion for L1-French learners.

It is noteworthy that the overall R 2 in both the immersion and nonimmersion L1-French models was low, indicating very small effect sizes. This suggests that other variables that were not included in the model may underlie French speakers’ decisions about which PA to use (e.g., hierarchy, physical context, etc.). It may also be that, even in immersion, learners did not have opportunities to interact with people in all age groups or in situations that were highly formal, thus lacking enough exposure to certain situations that were presented in the DCT (Quan, Reference Quan2019). As Kinginger and Farrell (Reference Kinginger and Farrell2004) proposed, PA choices depend on adequate socialization, and Quan (Reference Quan2019) clearly showed how the simple act of being abroad is not enough to ensure such socialization, as it greatly depends on the motivation, emotions, and goals of the learners. Therefore, if learners’ social life in immersion does not include enough opportunities to notice differences between L1 and L2 address patterns, L1-transfer will continue to play a great role and they may not adopt L2-uses as readily. Finally, the DCT used in this study does not offer items for all possible combinations of variables, as it would result in a long test that very few participants would agree to complete. It is possible that the inclusion of additional items could have brought light onto specific combinations of predictors that could reach significance together but not in isolation.

In the case of the L1-European Portuguese learners of L2-Spanish, the models showed larger effect sizes, pointing to a better fit of the variables at hand for these learners. Age and sociocultural level were significant predictors of the use of tú both in immersion and nonimmersion. However, the level of formality of the situations described in the DCT played a distinct role in deciding to use tú for participants who were in a nonimmersion context, but not for those who were living in Spain. This pattern shows that not only did L1-Portuguese learners in immersion better align with L1-Spanish speakers in that they started using tú more often than in nonimmersion; they also started rejecting PA selection criteria that were transferred from their L1 but not as relevant in their daily interactions in Spanish. Indeed, formality was one of the least predictive (though significant) variables in the L1 model. These data seem to indicate that, in the case of the L1-Portuguese group, pragmatic transfer was reduced when learners were immersed in a Spanish-speaking environment, in terms of both frequency of T/V use, as Granvik (Reference Granvik2005) also pointed out, and of the variables taken into consideration when making decisions about PA choice.

In sum, the difference between being in immersion or not was overall more observable in the pragmatic choices of L1-Portuguese learners than in L1-French learners. This may be due to several factors. First, when it comes to frequencies of use of tú and usted, the choices of L1-French learners tended to deviate less from those of the L1-Spanish speakers. They did use usted more often than L1 speakers but less than L1-Portuguese learners. In this context, L1-French learners had less room for improvement and may have had a harder time noticing the difference between their own T/V uses and those of L1-Spanish speakers while in immersion. Alternatively, L1-Portuguese learners in nonimmersion were already making use of predictors of PA use that were similar to those of L1 speakers (i.e., age, sociocultural status, closeness). Even if they used usted as the default option in many cases, the specific variables that they took into account when deciding when to use tú differed less from the L1 speakers than L1-French learners, for whom none of the predictors reached significance in the nonimmersion group.

Conclusion

This study analyzed the uses of the Spanish address pronouns, tú and usted, by learners whose L1s display similar pronominal distinctions—namely, French and European Portuguese. Although both languages have various forms of address to indicate a greater or lesser distancing, as is the case in Spanish, the specific variables that determine which pronoun fits better in a particular context vary between languages. First, both French and European Portuguese exhibit an overall preference for their respective V forms, whereas in Spanish the T form is the default. Additionally, speakers of European Portuguese tend to use information about the formality of the situation as a central criterion to determine which address form to use. Spanish speakers, alternatively, tend to guide their decision by the age of the interlocutor as well as their perceived sociocultural level. This study indicates that learners of both L1s not only increase their use of tú during a study abroad experience but also start adopting more native-like criteria in deciding which PA to use, displaying less instances of pragmatic transfer when in immersion.

These findings demonstrate that (1) PA choices are challenging even for learners’ whose L1s also have a T/V distinction and (2) immersive experiences result in more native-like uses. Such data have implications not only for future research, which should dive deeper into the development of pragmatic competence by learners of L1s other than English, but also for L2-Spanish teaching. Indeed, the evidence of pragmatic transfer found in the nonimmersion groups and the difficulty experienced by students as they adapt to new T/V uses in their L2 seem to confirm the need for an in-depth pedagogical treatment of the distinction between tú and usted. A more systematic approach that explicitly explains the decision process behind T/V choices by L1-speakers of Spanish may be a first step in the right direction. Furthermore, analyzing recorded interactions between speakers and trying to understand why each interlocutor used the pronouns they used in this situation would also allow for interesting discussions about politeness standards in different cultures. This approach, though, would need to be adapted to the community of Spanish speakers that learners may most probably interact with, as T/V uses present a great deal of variation across the Spanish-speaking world.

Despite the contributions of the present study, some limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the items included in the DCT were designed based on the most influential predictors found in previous literature, but it is probable that more factors are important in PA decisions, such as the personality and pleasantness of the interlocutor, or the physical context (e.g., being at the office or at the cafe with your boss or coworkers), for example. Additionally, due to time constraints, the DCT does not include items that cover all possible interactions of the multiple variables, which limits our understanding of how these factors influence each other in different communicative situations. Finally, it might also be relevant to replicate this study’s findings by looking at speech corpora, which would provide more naturalistic data. In sum, this study is a first step in the direction of going beyond the focus on L1-English students when it comes to learning the distinction between tú and usted in L2-Spanish, but more sources of data will be necessary to provide a full picture of this learning process in various L1 groups.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Paloma Fernández Mira for her work on the statistical models in this article and to acknowledge the help provided by students and faculty during data collection at the Universidade de Lisboa, Universidad de Salamanca, and Université Sorbonne Nouvelle. This study was funded through a grant from the Xunta de Galicia (Spain) received by María Sampedro Mella and titled “Use of general and learner corpora for the research and teaching of discourse in Spanish as a foreign language” [grant code: ED481D–2022–016].

Appendix 1

Demographic questions:

-

• Edad [age]:

-

• Sexo [gender]:

-

• Nacionalidad [Nationality]

-

• Lengua(s) materna(s) [L1(s)]:

-

• Titulación que está cursando [University major]:

-

• Tiempo de estudio de español [Period of time studying Spanish]:

-

• Tiempo residiendo en España [Period of time living in Spain]:

-

• ¿Has residido en algún otro país en el que se hable español? [Have you ever lived in another Spanish-speaking country?]

ITEMS OF THE DCT

-

1. Vas a comprar manzanas al mercado, pero no las encuentras. Pregúntale a la vendedora si tiene más en el almacén. [You go to the market to buy apples, but cannot find them. Ask the salesclerk if she has more in store.]

-

2. Has faltado al trabajo porque estás enfermo. Pídele al médico que te ha atendido en el hospital que te firme un justificante. [You have missed work because you are sick. Ask the doctor who examined you at the hospital to sign a doctor’s note.]

-

3. Vas a dejar tu CV a una empresa y te atiende el responsable de recursos humanos, que es más joven que tú. Pídele una tarjeta de visita. [You go to the offices of a company to apply for a job, and give your CV to a Human Resources officer who is younger than you. Ask him for a business card.]

-

4. Encuentras a tu vecina, una mujer mayor, cargada con bolsas y decides ofrecerle tu ayuda. ¿Qué le dices? [You run into your neighbor, an elderly woman, carrying grocery bags and you decide to offer your help. What do you tell her?]

-

5. Encuentras un móvil en la calle y crees que pertenece a un hombre que anda por la zona. Pregúntale si el teléfono es de él. [You find a cellphone in the street and think that it belongs to a man who you have seen walking around. Ask him if the cellphone is his own.]

-

6. Estás en el ayuntamiento y te atiende una señora funcionaria. Te has equivocado en la fecha de tu impreso, ¿cómo le pides que la corrija? [You are in the town hall, being attended by a civil servant who is an older woman. You have inadvertently written a wrong date on a form. How would you ask her to correct it?]

-

7. Estás en la frutería donde siempre compras. Pídele a la vendedora que te recomiende algo para comprar. [You are at your usual fruit store. Ask the salesclerk to recommend you something to buy.]

-

8. El señor mayor con el que siempre hablas en el autobús ha dejado su cartera olvidada en el asiento y se la has guardado, ¿qué le dices cuando se la devuelves? [The elderly man with whom you always talk in the bus has left his wallet on his seat when he left the bus and you have kept the wallet. What would you tell him when you give it back to him?]

-

9. Acudes a urgencias por una lesión en un pie. Pídele a la médica que te recete unos calmantes, porque tienes mucho dolor. [You go to the emergency room due to a foot injury. Ask the [female] doctor to prescribe you some painkillers, as you are in a lot of pain.]

-

10. Has puesto un dato incorrecto haciendo un ingreso. ¿Cómo le pides a Pérez, empleado del banco a punto de jubilarse, que lo rehaga con la información correcta? [You have made a mistake when making a deposit at the bank. How would you ask Pérez, a bank clerk who is about to retire, to repeat the procedure with the correct information?]

-

11. Pregúntale al camarero si puede servirte el plato que quieres sin pimiento, porque eres alérgico. [Ask the [male] waiter if they can alter your dish by not including peppers, because you are allergic to them.]

-

12. Acudes a la óptica a comprarte gafas nuevas y la especialista que te atiende, más joven que tú, te muestra varios modelos, pero ninguno te convence. Pídele más opciones. [You go to the optician to buy new glasses and the clerk, who is a woman and is younger than you, shows you some models. You are not convinced by any of the ones she shows you. Ask her for more options.]

-

13. A la mujer que va andando delante de ti se le acaba de caer la bufanda y tú se la has recogido, ¿qué le dices al entregársela? [The woman who walks ahead of you in the street has just dropped her scarf and you have picked it up. What would you say when you give it back to her?]

-

14. Pregúntale al señor de la tienda donde siempre compras si tiene más cuadernos, porque ninguno te gusta. [Ask the salesclerk from your usual shop if he has different notebooks in store, because you do not like any of the ones you have seen in the shop.]

-

15. Pregúntale a la chica que limpia el portal de tu edificio si puede fregar delante de tu puerta, porque está bastante sucio. [Ask your building’s cleaning lady to mop the floor in front of your door, because it is quite dirty.]

-

16. ¿Cómo le pides a tu farmacéutico de siempre, un señor mayor, que te recomiende algún medicamento para la gripe? [How would you ask your usual pharmacist, an elderly man, to recommend you some medicine for the flu.]