Abstract

Globalization, defined as trade- and FDI-related interdependence among nations, increases social welfare by transmitting managerial practices, advanced technologies, and labor skills across borders. Recent declines in FDI flows have prompted scholars to speculate on the nature, magnitude, and determinants of de-globalization trends. We investigate whether a U.S. national security-related foreign investment screening law, the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA), contributes to de-globalization trends. FINSA awarded a regulator known as the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States broad new powers to revise or reject foreign acquisitions of firms in national security-related industries. Using a difference-in-differences research design, a wide variety of model specifications, and estimation samples spanning 1990–2016, we document post-FINSA declines in foreign takeovers of U.S. firms in national security-related industries. Consistent with techno-nationalism, we document that takeover declines are concentrated among research-intensive national security firms. Placebo, event-time, and robustness tests corroborate our results. Our empirical evidence suggests that foreign investment screening laws help explain the nature, magnitude, and determinants of recent de-globalization trends and prompts multinational enterprise managers to increasingly weight the political factors behind foreign investment screening laws when assessing foreign investment strategies.

Résumé

La globalisation, définie comme l'interdépendance des nations en matière de commerce et d'IDE, augmente le bien-être social en transmettant les pratiques de gestion, les technologies avancées et les compétences de la main-d'œuvre à travers des frontières. La baisse récente des flux d'IDE a incité les chercheurs à spéculer sur la nature, l'ampleur et les déterminants des tendances de dé-globalisation. Nous explorons si une loi américaine liée à la sécurité nationale et au filtrage des investissements étrangers, la Foreign Investment and National Security Act de 2007 (FINSA), contribue aux tendances de dé-globalisation. La FINSA a conféré à un régulateur connu sous le nom de Comité pour l'Investissement Etranger aux États-Unis de nouveaux pouvoirs étendus pour réviser ou rejeter des acquisitions étrangères d'entreprises dans les secteurs liés à la sécurité nationale. À l'aide d'un plan de recherche de différences dans les différences, d'une grande variété de spécifications de modèle et des échantillons d'estimation couvrant la période 1990-2016, nous démontrons les déclins post-FINSA dans les prises de contrôle étrangères d'entreprises américaines dans les secteurs liés à la sécurité nationale. En accord avec le techno-nationalisme, nous prouvons que les baisses de prises de contrôle sont concentrées parmi les entreprises de sécurité nationale à forte intensité de recherche. Les tests de placebo, d'event-time et de robustesse corroborent nos résultats. Ces derniers suggèrent que les lois sur le filtrage des investissements étrangers aident à expliquer la nature, l'ampleur et les déterminants des récentes tendances de dé-globalisation. Ils incitent également les dirigeants d'entreprises multinationales à accorder de plus en plus d'importance aux facteurs politiques qui sous-tendent les lois sur le filtrage des investissements étrangers lors de l'évaluation des stratégies d'investissement à l'étranger.

Resumen

La globalización definida como la interdependencia entre los países con el comercio, y la inversión extranjera directa, aumenta el bienestar social al transmitir prácticas gerencias, tecnologías avanzadas y competencias laborales más allá de las fronteras. Los recientes descensos de los flujos de inversión extranjera directa han llevado a los académicos a especular sobre la naturaleza, la magnitud y los factores determinantes de las tendencias a la desglobalización. Investigamos si una ley estadounidense de control de la inversión extranjera relacionada con la seguridad nacional, la Ley de Inversión Extranjera y Seguridad Nacional de 2007 (FINSA por sus iniciales en inglés), contribuye a las tendencias de desglobalización. La FINSA otorgó a un regulador conocido como el Comité de Inversiones Extranjeras de los Estados Unidos amplios poderes nuevos para revisar o rechazar adquisiciones extranjeras de empresas en sectores relacionados con la seguridad nacional. Utilizando un diseño de investigación de diferencias en diferencias, una amplia variedad de especificaciones de modelos y muestras de estimación que abarcan 1990–2016, documentamos descensos posteriores a FINSA en las adquisiciones extranjeras de empresas estadounidenses en industrias relacionadas con la seguridad nacional. En consonancia con el tecno-nacionalismo, documentamos que los descensos en las adquisiciones se concentran en las empresas de seguridad nacional intensivas en investigación. Las pruebas de placebo, evento-tiempo y robustez corroboran nuestros resultados. Nuestra evidencia empírica sugiere que las leyes de control de la inversión extranjera ayudan a explicar la naturaleza, la magnitud y los factores determinantes de las recientes tendencias a la desglobalización, e incitan a los directivos de empresas multinacionales a tener cada vez más en cuenta los factores políticos que subyacen a las leyes de control de la inversión extranjera a la hora de evaluar las estrategias de inversión extranjera.

Resumo

Globalização, definida como a interdependência relacionada ao comércio e ao FDI entre nações, aumenta o bem-estar social ao transmitir práticas gerenciais, tecnologias avançadas e habilidades de trabalho além-fronteiras. Recentes declínios nos fluxos de FDI levaram acadêmicos a especular a respeito da natureza, magnitude e determinantes das tendências de desglobalização. Investigamos se uma lei de triagem de investimento estrangeiro relacionada à segurança nacional dos EUA, a Lei de Investimento Estrangeiro e Segurança Nacional de 2007 (FINSA), contribui para tais tendências de desglobalização. FINSA concedeu a um regulador conhecido como Comitê de Investimento Estrangeiro nos Estados Unidos novos e amplos poderes para revisar ou rejeitar aquisições estrangeiras de empresas em setores relacionados à segurança nacional. Usando um design de pesquisa baseado em diferenças em diferenças, uma ampla variedade de especificações de modelos e amostras de estimativas de variando de 1990 a 2016, documentamos declínios em aquisições estrangeiras de empresas americanas em setores relacionados à segurança nacional no período pós-FINSA. De forma consistente com o tecnonacionalismo, documentamos que declínios nas aquisições estão concentrados entre empresas de segurança nacional intensivas em pesquisa. Testes com placebos, tempo de evento e robustez corroboram nossos resultados. Nossa evidência empírica sugere que leis de triagem de investimento estrangeiro ajudam a explicar a natureza, a magnitude e determinantes das recentes tendências de desglobalização e convidam gerentes de empresas multinacionais a ponderar cada vez mais os fatores políticos inseridos nas leis de triagem de investimento estrangeiro ao avaliar estratégias de investimento estrangeiro.

摘要

全球化定义为国家之间的与贸易和外国直接投资 (FDI) 相关的相互依存, 它通过跨境传播管理实践、先进技术和劳动技能来增加社会福利。最近FDI流量的下降促使学者们推测去全球化趋势的性质、规模和决定因素。我们调查了与美国国家安全相关的外国投资审查法, 即2007 年外国投资和国家安全法(FINSA), 是否为去全球化趋势作出了贡献。FINSA 赋予一个叫做在美外国投资委员会的监管机构广泛的新权力, 以修改或拒绝外国对国家安全相关行业公司的收购。使用差异研究设计、各种模型规范以及 1990 至 2016 年间的估计样本, 我们记录了后 FINSA时期与国家安全相关行业的美国公司被外国收购的下降。与技术民族主义一致, 我们记录了收购下降集中在研究密集型国家安全公司中。安慰剂、事件时间和稳健性测试证实了我们的结果。我们的实证证据表明, 外国投资审查法有助于解释近期去全球化趋势的性质、规模和决定因素, 并促使跨国企业管理者在评估外国投资战略时越来越重视外国投资审查法背后的政治因素。

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Globalization, defined as trade- and FDI-related interdependence among nations, increases social welfare by transmitting managerial practices, advanced technologies, and labor skills across borders (Contractor, 2021; McGaughey, Raimondos, & la Cour, 2020; Petricevic & Teece, 2019; Verbeke, Coeurderoy, & Matt, 2018; Witt, 2019). FDI in particular improves shareholder welfare because foreign investors pay larger cash premiums than domestic acquirers when acquiring equities (see, e.g., Bass & Chakrabarty, 2014; Gu & Lev, 2011; Harris & Ravenscraft, 1991). Given the substantial benefits of globalization, recent declines in FDI flows have prompted scholars to speculate on the nature, magnitude, and determinants of de-globalization trends (International Monetary Fund, 2020; World Investment Report, 2020; Contractor, 2021; Luo, 2021; Witt, 2019).1

This study investigates the effect of a U.S. national security-related foreign investment screening law on de-globalization. On one hand, Contractor (2021) characterizes the worldwide proliferation of national security policies as introducing only marginally more protectionism into multinational enterprises’ (MNEs’) operating environments. On the other hand, foreign investment screening laws impose large costs on would-be foreign acquirers and credibly threaten to obstruct cross-border capital flows (Luo, 2021; Witt, 2019). These competing perspectives have led to calls for “more richly textured analysis” documenting de-globalization determinants and trends (Contractor, 2021: 12). We answer this call by investigating whether a U.S. national security-related foreign investment screening law contributes to de-globalization.

We address our research question by employing the enactment of the Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007 (FINSA) in the United States as a source of variation in foreign investment screening laws and measuring globalization using cross-border acquisition activity.2 We choose to examine the U.S. adoption of a foreign investment screening law due to the United States’ longstanding policy of openness to FDI. From 1998 to 2018, foreign investors spent an average of $289 billion per year acquiring U.S. firms, accounting for 19% of all U.S. mergers and acquisitions (M&A) activity (SDC, 2019).3

Our difference-in-differences (DiD) research design anchors on FINSA. FINSA significantly strengthened the pre-existing U.S. foreign investment screening mechanism. U.S. legislators enacted FINSA on July 11, 2007, and the U.S. Department of Treasury finalized implementing regulations on November 21, 2008 (Federal Register, 2008). FINSA awarded a multiagency regulator, led by the U.S. Department of Treasury and known as the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), broad new powers to revise or reject foreign acquisitions of U.S. firms deemed critical to national security. Rejections are inherently costly to foreign acquirers, and even successful foreign acquirers face new costs stemming from increases in U.S. Congressional oversight of foreign investment, delays in the benefits of foreign acquirers’ intended acquisition strategy, increases in the probability of competing bids, and increases in the frequency and severity of CFIUS-imposed national security risk-mitigation conditions and related non-compliance penalties. By endowing CFIUS with these new powers, FINSA addresses national security concerns voiced by U.S. policymakers and the public that foreign entities could exploit the U.S. takeover market to acquire critical technologies and disrupt supply chains (Moran, 2009).

To investigate whether national security-related foreign investment screening laws are associated with de-globalization, we determine whether foreign takeovers of U.S. national security firms declined after FINSA relative to foreign takeovers of non-national security firms. We identify national security firms using unclassified CFIUS documents that list 61 industries critical to national security by four-digit SIC (CFIUS, 2008). Firms in these industries comprise one-third of all U.S. public firms.4

We document a marked decline in foreign takeovers of U.S. national security firms relative to non-national security firms following FINSA. The decrease in the probability of a foreign takeover of a U.S. national security firm is a statistically significant one-half of one percentage point, representing an economically significant impact because the unconditional probability of takeover in the U.S. sample is 2.1%. This inference is robust to a wide variety of empirical specifications including univariate and multivariate models with and without control variables and fixed effects, employing either a pooled or an entropy-balanced estimation sample. We infer from our evidence that national security-related foreign investment screening laws are an economically significant factor driving de-globalization.

We next document that the effect of FINSA on U.S. national security firms’ takeover markets is stronger for firms more likely to face a CFIUS intervention. CFIUS intervenes in foreign acquisitions when foreign takeovers present a national security threat. Moran (2009) describes two national security threats stemming from foreign takeovers. First, acquired technology could enable U.S. rivals if foreign acquirers deploy technologies for military purposes. Motivated by this concern and by recent arguments that states are becoming more techno-nationalistic (Luo, 2021),5 we predict and find that the effect of FINSA on U.S. national security firm takeovers strengthens for research-intensive national security firms with more patents and patent citations. The second threat is that excessive reliance on foreign-owned firms could render the U.S. government vulnerable to supply-chain disruptions. We predict and find that the effect of FINSA on national security firm takeovers strengthens for national security firms with a greater ability to disrupt national security-related supply chains.

We find little to no variation in the frequency of takeovers for analogous control firms. In addition, noting that FINSA does not affect domestic takeovers of national security firms, we predict and find no variation in domestic takeovers of national security firms after FINSA. We further predict and find no variation in foreign acquisitions of nominally small equity stakes (valued at less than $100 million) in national security firms following FINSA. This evidence is consistent with foreign acquisitions of nominally small equity stakes being less likely to yield the control rights necessary for determining, directing, or deciding matters affecting U.S. assets in ways that threaten national security.

We next present a dynamic analysis using an event-time empirical specification demonstrating (1) that variation in U.S. national security firm takeover activity, vis-à-vis non-national security firms, occurs only after FINSA; (2) that no variation in U.S. national security firm takeover activity occurs prior to FINSA; and (3) the validity of the parallel trends assumption in our setting (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2003). Using the same event-time specification, we further observe no differences in placebo domestic takeover frequencies between national security and non-national security firms either before or after FINSA. Last, we observe no differences in the frequency with which foreign investors purchase nominally small equity stakes in national security or non-national security firms before or after FINSA.

Overall, results generated by cross-sectional and placebo tests support the inference that FINSA drives the observed decline in U.S. national security firms’ takeover market after FINSA. For an omitted variable to explain our results, it must explain a contemporaneous decline in only foreign takeovers of only majority stakes in only research-intensive and high-production-capacity firms within only national security-related industries. These empirical patterns indicate that FINSA, rather than an omitted variable, drives post-FINSA variation in national security firm takeover frequency.

Our evidence documenting the effect of national security-related foreign investment screening laws on de-globalization contributes to the international business (IB) literature in several ways. First, speculation regarding de-globalization has captured the attention of many IB scholars (e.g., Buckley, 2020; Petricevic & Teece, 2019) due to strong priors among some scholars that globalization is an irreversible process (Verbeke et al., 2018). Petricevic and Teece (2019) note that, “until recently, a popular (albeit flawed) view was that cross-border activities had become so common and growing so significantly that the world was becoming…a frictionless, homogenous, rule-of-law borderless world and a global playing field.” Against this backdrop, recent IB work points to the United Kingdom’s 2016 vote to leave the European Union and former President Trump’s America First policy as early evidence of economically significant de-globalization trends (Kobrin, 2017). Others speculate that, “at a global level, de-globalization seems to have been in progress for several years, at least with respect to the dimensions most directly relevant to international business, trade and FDI” (Witt, 2019: 1055). In contrast, other work characterizes ad hoc protectionist interventions as only marginally affecting globalization (Contractor, 2021; Verbeke et al., 2018; World Trade Organization [WTO], 2017).

Further illustrating the importance of our analysis and inferences, Witt (2019: 1053) notes that evidence of de-globalization “would induce a significant qualitative shift in strategies, structures, and behaviors in international business…requir(ing) international business research to develop a much deeper integration of politics, the key driver of de-globalization.” Consistent with this view and the growing relevance of politics for FDI, U.S. lawmakers are passing new laws expanding CFIUS’s scope while rejecting proposed laws requiring economic assessments to accompany national security reviews (GAO, 2018; Jackson, 2018).6 Accordingly, our evidence strongly encourages MNE managers to increasingly weight the political factors behind foreign investment screening laws when assessing their foreign investment strategies.

Second, our evidence highlights a first-order global problem facing IB managers because the foreign investment screening law we examine inhibits MNEs from efficiency gains otherwise provided by access to foreign markets for corporate control (Buckley, Clegg, Voss, Cross, Liu, & Zheng, 2018; Henisz, Mansfield, & Von Glinow, 2010). For example, foreign investment screening laws impose costs on foreign investors by inhibiting MNE managers from acquiring resources in foreign territories and gaining access to synergies made available by effecting strategic acquisitions abroad.

Relatedly, foreign investment screening laws impose costs on foreign investors by increasing the deterrent effect of tariffs. As noted by Buckley (2020: 1582), the fact that “tariffs reduce imports and induce tariff-jumping FDI is well established in 50 years of international business theory.” Foreign investment screening laws reduce foreign investors’ ability to sidestep tariffs through tariff-jumping and so increase the cost of tariffs on foreign MNEs.

Third, when foreign investment screening laws curb foreign investment, they curb not only cross-border transfer of superior management practices, advanced technologies, and related local labor specialization but also the cross-border transfer of gender equality, sustainability, and ethics (Ahlvik, Smale, & Sumelius, 2016; Berry, Guillén, & Zhou, 2010; Ellis, Moeller, Schlingemann, & Stulz, 2017). Also forfeited are the welfare-enhancing productivity spillover externalities associated with foreign investment (Eden, 2009; McGaughey et al., 2020). These costs fall hardest on emerging markets more likely to benefit from the transmission of management practices, advanced technologies, and labor specialization as well as emerging MNEs more likely to employ a “springboard” strategy of acquiring foreign competencies, capabilities, and resources in their bid to remain or become globally competitive.

Fourth, our work responds to concerns that “the relevance of interstate security relations to international business has received little attention” (Li & Vashchilko, 2010: 765). In this study, we document the relevance to de-globalization of national security-related foreign investment screening laws. We encourage further work at the intersection of security relations and IB that leverages key features of our design: (1) an objective classification of national and non-national security firms and (2) variation in national security relevance among national security firms.7 Taken together, these setting features facilitate robust research designs with clear identification strategies that significantly mitigate endogeneity concerns that otherwise threaten the credibility of archival method-based inferences.

We conclude our study by noting that, while we do not suggest that governments eschew foreign investment screening laws, we do submit that foreign investment screening laws accelerate de-globalization and significantly alter MNEs’ operating environment and strategic option set. The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section two details the institutional setting and develops the hypotheses. Section three describes the data. Section four presents the effect of FINSA on the takeover market, and section five shows FINSA’s shareholder wealth effects. Section six concludes.

INSTITUTIONAL SETTING AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT

Institutional Setting

National security concerns have long been relevant to host country foreign investment policies (Arpan & Ricks, 1974; Arpan, Flowers, & Ricks, 1981; Grosse & Trevino, 1996; Kim & Lyn, 1987; Kobrin, 2017; Tallman, 1988). Historically, however, national security concerns have been dominated by Washington Consensus ideals, which call for cross-border trade and capital liberalization. In the United States, CFIUS was created following post-World War II national security concerns. The origins of CFIUS are rooted in the Defense Production Act of 1950 (DPA), which permits the U.S. president to reject foreign investments that threaten national security. President Ford delegated the review of foreign transactions to CFIUS in 1975. A “Notice of Foreign Investment” alerts CFIUS to a pending acquisition. Either party to the transaction, a concerned industry member, or another U.S. entity may provide the notice, but CFIUS may also self-initiate the review process. The Notice of Foreign Investment triggers a 30-day CFIUS review, after which CFIUS can decide to conduct a further 45-day formal investigation. The outcome of that investigation may be approval or approval conditional on an agreement that mitigates national security concerns. CFIUS may also recommend rejection to the U.S. president.

In 2006, Congressional disapproval of a high-profile CFIUS investigation into Dubai Ports World (Rose, 2014)8 and increasing foreign government investment in U.S. equity through sovereign wealth funds (GAO, 2008, 2009; Graham & Marchick, 2006; Rose, 2014), coupled with adverse contemporaneous GAO performance reviews of CFIUS, triggered FINSA’s passage reforming CFIUS (GAO, 2015). Figure 1 demonstrates that, before FINSA, CFIUS performs a 30-day review of an average of 92 foreign investments per year. Figure 2 illustrates that, prior to FINSA, 98% of foreign investments were approved without a supplementary 45-day CFIUS investigation more likely to give rise to costly national security risk-mitigation demands. This bureaucratic process injected few uncertainties into the acquisition process for domestic targets and foreign acquirers (Byrne, 2006). By amending the DPA through FINSA, Congress significantly increased CFIUS’s ability and inclination to thwart foreign acquisitions. Figure 2 illustrates that, following FINSA, 45% of all national security-related foreign investment reviews led to a supplementary 45-day CFIUS investigation each year.

FINSA specifically charges CFIUS with scrutinizing foreign investments for patterns of coordinated acquisition behavior that could result in the transfer of advanced technologies to U.S. rivals. To fulfill this obligation, CFIUS meets weekly to perform three core functions: (1) review transactions and take action to address any national security concerns, (2) monitor and enforce compliance with mitigation measures, and (3) identify transactions that related parties have not submitted to CFIUS for review (Jackson, 2018).

In strengthening CFIUS, FINSA increased the barriers to foreign investment in four ways. First, FINSA delays the acquisition timeline by increasing the purview of CFIUS and, thus, the likelihood of not only a month-long “review” process but also a second 45-day CFIUS “investigation.” Lengthy approval periods are costly for would-be acquirers because they delay the benefits of foreign acquirers’ intended acquisition strategy and increase the probability of competing bids (Fieberg, Lopatta, Tammen, & Tideman, 2021; Luo, 2021).

Second, FINSA increases deal uncertainty by increasing political risk for foreign acquirers. FINSA gives Congress a larger role in the investment approval process, adding uncertainty to whether CFIUS would approve, revise, or reject foreign investment proposals. Rose (2014: 24–33) writes,

One of the most important aspects of FINSA is an increase in Congressional oversight…. FINSA creates a “broad new system for reporting information on CFIUS activities to Congress so that it may conduct appropriate oversight of the CFIUS”. This system includes a formal process by which Congress may request a “detailed, classified briefing” on a transaction; a requirement that CFIUS file annual reports with Congress that list transactions handled by CFIUS, cumulative and trend analysis of transactions by business sector and country of origin, and information on mitigation agreements entered into by CFIUS and parties to a transaction…. A redacted annual report covering the prior is made public in near the end of the following year; the full report, containing classified information, is provided to Congress…. To the extent that FINSA involves more Congressional oversight of CFIUS than under (preceding legislation), the process is perhaps more at risk of becoming politicized.

Uncertainty stemming from this new foreign investment screening law is accentuated because the U.S. government classifies all CFIUS investigation details. The DPA requires that even basic details about CFIUS interventions remain classified (GAO, 2018), and, because the DPA inhibits CFIUS disclosures, neither foreign nor domestic market participants know which M&A transactions are investigated and whether or why regulators impose national security risk-mitigation agreements or prohibit transactions. While first-order national security concerns drive CFIUS’s secretive decisions regarding what specific foreign acquisitions to investigate, the accompanying regulatory uncertainty has led to a growing debate over whether FINSA harms U.S. capital markets by discouraging FDI for the largest FDI recipient in the world (GAO, 2018; Jackson, 2018). Prior research shows that uncertainty decreases investment activity (Bhagwat, Dam, & Harford, 2016; Bonaime, Gulen, & Ion, 2018; Jens, 2017).

Third, FINSA increases the likelihood that CFIUS will impose costly national security risk-mitigation agreements on foreign investors. For example, mitigation agreements may require that the acquirer terminate specific activities of the U.S. business being acquired or allow the U.S. government to review certain business decisions and object if they raise national security concerns. Internet “Appendix 1” provides a list of costly risk-mitigation clauses implemented by CFIUS and disclosed in the public version of their 2014 annual report. Consistent with risk-mitigation costs being large, we observe anecdotal evidence from the financial press of foreign investors abandoning their proposed deal after CFIUS proposes risk-mitigation terms. Other would-be foreign acquirers simply withdraw their offers after learning that the CFIUS will review the deal.9 Figure 3 illustrates a significant post-FINSA increase in the proportion of foreign investment notices withdrawn by foreign acquirers. Foreign acquirers withdrew fewer than 2% of foreign investment proposals during the CFIUS review and investigation processes prior to FINSA. Following FINSA, foreign acquirers withdraw an average of 12% of all foreign investment proposals during the CFIUS review and investigation processes.

Fourth, FINSA strengthens CFIUS enforcement and penalties for noncompliance. FINSA provides for the “imposition of civil penalties for any violation…, including [violations of] any mitigation agreement” (Zaring, 2010: 97). FINSA also encourages CFIUS to “develop and agree upon methods for evaluating compliance with any agreement entered into or condition imposed with respect to a covered transaction that will allow the Committee to adequately assure compliance,” which bolsters their sanctioning authority (97). Rose (2014) notes that “FINSA allows CFIUS to reopen reviews and investigations if there has been an intentional breach of a mitigation agreement” (32). After FINSA, breaking a mitigation agreement can result in penalties up to the full value of the transaction and may force the unwinding of the transaction (Rose, 2014: 14).

Hypothesis Development

The foregoing discussion identifies FINSA as a source of exogenous variation in the barriers faced by would-be foreign acquirers of U.S. national security firms. Our first hypothesis evaluates the effect of these new barriers on the national security firms’ takeover market.

Hypothesis 1:

Foreign takeovers decline for national security firms after the enactment of FINSA.

We expect FINSA-related barriers to foreign investment to increase with the extent to which foreign ownership presents a national security threat (Luo, 2021). We define two potential national security threats following Moran (2009): (1) that acquired technology could be deployed by the acquirer for other than commercial and financial purposes, potentially enabling U.S. rivals,10 and (2) that excessive reliance on foreign-owned enterprises could render defense contractors vulnerable to supply chain disruptions. We capture variation in the first threat using national security firms’ research intensity. We capture variation in the second threat using national security firms’ production capacity. If FINSA-related barriers to foreign investment are large, then foreign takeovers will decline more in national security firms with greater research intensity and production capacity. Formally stated:

Hypothesis 2:

Foreign takeovers decline more after FINSA for national security firms with greater research intensity and production capacity.

We conclude our hypothesis development by noting several reasons to expect no relationship between FINSA and globalization in our setting. While FINSA’s formalized foreign investment screening process appears to impose costs on foreign acquirers, its impact on the takeover market is not obvious for at least four reasons. First, the United States has a history of failed attempts to inhibit foreign investment. Two prior amendments to DPA – the 1988 Exon-Florio amendment and the 1993 Byrd amendment – were designed by Congress to empower CFIUS to obstruct foreign investment, yet neither had a discernible effect on CFIUS activity (Graham & Marchick, 2006; see also, Figure 2). This suggests that another amendment – FINSA – will be similarly ineffective. Non-U.S. evidence, however, is mixed. Dinc and Erel (2013) suggest that European countries’ ad hoc attempts to inhibit foreign investment are effective while Fratteroli (2020) suggests that a 2014 French foreign investment screening law inhibits foreign takeovers of private but not public firms.

Second, prior to FINSA, foreign acquirers faced regulatory uncertainty in the takeover market due to the non-zero threat of U.S. government interventions (see, e.g., Wan & Wong, 2009). While CFIUS began screening foreign investment in a wide array of industries after FINSA, specific sectors (e.g., nuclear energy production) were already subject to federal provisions that either restricted the level of foreign investment, limited the use of a foreign-owned asset, or required approval or disclosure of any foreign investments.11 If regulatory uncertainty pervaded the pre-FINSA takeover market, then it is possible that FINSA’s formalized foreign investment screening process renders regulatory interventions in the takeover market more predictable and reduces a barrier to foreign investment.

Third, though FINSA significantly alters CFIUS’s mandate, CFIUS possesses neither a centralized budget nor permanent staff. Instead, the federal agency representatives populating CFIUS use discretion to provide resources to CFIUS as needed (GAO, 2018). One governance implication is that CFIUS resources have not kept pace with CFIUS reviews and investigations. Foreign investments scrutinized by CFIUS increased by 55% between 2011 and 2016 while personnel provided by member agencies increased by 11% (GAO, 2018). Taken together, these setting features render the effects of FINSA on takeover market activity an empirical question.

There are several more general reasons to expect no relationship between national security-related foreign investment screening laws and globalization. First, the costs that foreign investment screening laws impose on would-be foreign acquirers may not deter cross-border acquisitions if they are sufficiently attractive and profitable (Buckley, 2020). Second, foreign investment screening laws may have little effect if countries’ pre-existing antitrust and competition policies already allow host countries to intervene in national security-related foreign acquisitions (Aktas, de Bodt, & Roll, 2004; Dinc & Erel, 2013). Third, foreign investment screening laws may be ineffectual if domestic commercial and financial interests neuter their implementation. Each of these reasons supports the view that the effect of “heightened nationalism and protectionism (on cross-border flows) will be marginal rather than fundamental in nature” (Contractor, 2021: 1). Overall, the effect of national security-related foreign investment screening laws on globalization is another empirical question.

DATA AND DESCRIPTIVE STATISTICS

National Security Firms in the United States and Worldwide

Section 721(c) of the DPA prohibits disclosure of CFIUS interventions. Consequently, CFIUS does not list approved, revised, or rejected transactions. CFIUS does provide summary statistics of its activity each year but does not disclose, is not required to disclose, and cannot be compelled to disclose the specific firms subject to CFIUS interventions. In lieu of using classified CFIUS investigations to identify national security firms directly, we rely on unclassified CFIUS documents that use four-digit SIC codes to identify industries deemed critical to national security (CFIUS, 2008). “Appendix 1” lists 61 unique national security industries by four-digit SIC. National security industries include Advanced Materials and Processing, Chemicals, Advanced Manufacturing, Information Technology, Telecommunications, Microelectronics, Semiconductor Fabrication Equipment, Electronics: Military Related, Biotechnology, Professional/Scientific Instruments, Aerospace and Surface Transportation, Energy, Space Systems, and Marine Systems.

Firm and Acquisition Data

We gather firm data from Compustat North America. As documented in Table 1, our sample window spans 1990–2016, and our pooled estimation sample comprises 93,399 observations. Approximately one-third (34%) of observations are national security firm-years falling within the CFIUS definition of national security-related industries. We gather deal data from SDC Platinum. We include all SDC acquisitions of public firms in which an investor purchases an equity stake in excess of 50% with a cost of at least $100 million. In untabulated analyses, we document that the strength of our empirical results varies monotonically with this threshold, consistent with national security threats and regulatory scrutiny increasing in deal size. We gather patent and patent citation data from the NBER patent data project (Hall, Jaffe, & Trajtenberg, 2001) to conduct our cross-sectional tests. We gather control variables from Compustat, IBES, and Thomson Reuters.

We report summary statistics for national security and non-national security firms in Table 2. Table 2 documents that the probability of takeover and foreign takeover is similar for both groups, as is average market capitalization. With respect to cross-sectional partitions, the average national security firm has more patents and patent citations, lower production capacity (sales), and a similar takeover likelihood relative to the average non-national security firm.

With respect to firm characteristics known to determine takeover frequencies (Cremers, Nair, & John, 2009; Karpoff, Schnolau, & Wehrly, 2017), the average national security firm is smaller; has lower leverage; and is less capital-intensive, more liquid, and less profitable than the average non-national security firm. Both groups have similar market returns, analyst following, and institutional ownership. A key assumption underlying our DiD empirical approach is that national security and non-national security firms are similar but for the effects of FINSA. To address concerns that this assumption is violated, we also provide results where we entropy balance our estimation sample to force similarity across pre-FINSA firm characteristics.

Entropy balancing is a sampling procedure employed extensively in the recent literature (Hainmueller, 2012). In our setting, entropy balancing addresses covariate imbalance concerns by creating a control group of non-national security control firms sharing a high degree of covariate balance with national security firms across multiple moments. Entropy balancing weights control firm observations such that the mean, variance, and skewness of the matching variables for control firms match those for treatment firms. This procedure mitigates concerns regarding covariate balance in a manner similar to propensity score-matching but offers the incremental advantages of (1) retaining all data; (2) matching on the mean, variance, and skewness instead of just the mean; and (3) easier replicability given the many fewer research design decisions required when employing the entropy-balancing sampling procedure (McMullin & Schonberger, 2020; Shipman, Swanquist, & Whited, 2016).

Results of the matching procedure are tabulated in Table 3. Panel A of Table 3 documents pre-balancing summary statistics for national security and non-national security firms. Control variable summary statistics in Panel A differ from those in Table 3 because we use only pre-treatment (1990–2008) data in the entropy-balancing process to address concerns that FINSA directly affected matching covariates. Panel B of Table 3 demonstrates that the non-national security firm-year observations are reweighted such that the average non-national security firm displays mean, variance, and skewness nearly identical to the average national security firm. Covariate balance across treatment and control firms improves the credibility of non-national security firms as a counterfactual for national security firms. We tabulate our main results using unbalanced and entropy-balanced samples.

THE IMPACT OF FINSA ON THE TAKEOVER MARKET

Initial Evidence

We begin our examination of the effect of the investment barriers imposed by FINSA by compiling information contained in (1) the public version of CFIUS annual reports describing the aggregate level of CFIUS activity over time, (2) news articles, (3) company filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and (4) earnings conference calls.

We first examine whether FINSA led to an increase in the number of foreign investment notifications that CFIUS formally investigates. Figure 2 presents the percentage of foreign investments that CFIUS investigates, which we compile from the unclassified CFIUS annual reports. We find that, unlike following the 1988 Exon-Florio Amendment and the 1993 Byrd Amendment, CFIUS investigations increased dramatically starting in 2008. This evidence is consistent with FINSA significantly increasing scrutiny of M&A activity.

Second, we search Factiva for news articles that mention CFIUS and find that fewer than 400 articles mention CFIUS between 1989 and 2005 while more than 10,000 articles mention CFIUS between 2006 and 2016. Articles mentioning both “CFIUS” and “withdraw” (as in, “withdrawn offer”) also indicate barriers added by FINSA. Between 1989 and 2005, these articles numbered in the dozens while, since 2005, there have been more than 350 articles including both terms. We compile excerpts of representative articles in Internet “Appendix 2”.

Third, we compile data from SEC filings using SeekEdgar and present them in Figure 4. They show a significant increase in the number of firms that mention either “CFIUS” or the “Defense Production Act.” This also suggests the importance of CFIUS to public firms. Finally, analyzing earnings conference calls, we find that all recorded mentions of CFIUS during U.S. earnings conference calls occur in and after 2006.12 The numbers of CFIUS investigations, news articles mentioning CFIUS, and conference calls commenting on CFIUS all increase dramatically after the passage of FINSA. Variation in media articles and firm disclosures are strong indicators of an increase in barriers to capital flows after FINSA.

Empirical Method

To test Hypothesis 1, we follow Cremers et al. (2009) and Karpoff et al. (2017) and estimate Eq. (1) to examine the effect of FINSA on the frequency of firm takeovers in our cross-sectional partitions.

The dependent variable is equal to 1 for foreign acquisitions exceeding 50% of firm equity and $100 million. Post-FINSA is equal to 1 in years after 2008 and 0 otherwise, and National Security Firm is equal to 1 for national security firms and 0 otherwise. The DiD estimator is National Security Firm × Post-FINSA. We predict a negative DiD estimator, indicating that foreign takeovers of national security firms declined after FINSA relative to the contemporaneous change in foreign takeovers of non-national security firms.

We estimate several specifications to demonstrate the generalizability of our results to different models and samples. We estimate univariate and multivariate models with and without control variables and fixed effects, employing either a pooled or an entropy-balanced estimation sample. Karpoff et al. (2017) motivates our choice of firm-level control variables for Equation (1). Table 2 describes the control variables. We include four-digit SIC fixed effects (treatment varies at the four-digit SIC level). We include time-varying two-digit SIC fixed effects to account for takeover frequency time trends unique to a two-digit SIC industry (e.g., time-varying industry-level takeover waves; i.e., Harford, 2005; Maksimovic, Phillips, & Yang, 2013; Xu, 2017).13 This fixed effect structure addresses concerns that time-invariant four-digit SIC industry characteristics drive changes in foreign takeovers after FINSA and that shocks common to all firms in a two-digit SIC in a year drive changes in foreign takeovers after FINSA. We cluster standard errors by industry (four-digit SIC).

To test Hypothesis 2, we estimate Equation (1) separately for each cross-sectional partition. We partition the estimation sample at the median on patent count, patent citations, production capacity, and predicted takeover probability. The partitioning variable equals 1 when the pre-FINSA (1990–2008) average of the partitioning variable is above the sample median and 0 otherwise. We predict a negative coefficient on the DiD estimator in the high partition, consistent with fewer post-FINSA foreign takeovers for national security firms with more patents, patent citations, and production capacity and higher predicted takeover probability.

Results

Main results

We tabulate the estimation of Equation (1) across a variety of models in Table 4. Hypothesis 1 predicts a negative coefficient on our DiD estimator, National Security Firm × Post-FINSA. Column 1 presents a univariate estimation of Equation (1) in a pooled estimation sample. Column 2 replicates column 1 using the entropy-balanced sample. Column 3 estimates a multivariate specification including control variables listed in Table 2 using a pooled estimation sample. Column 4 replicates column 3 using the entropy-balanced sample. Columns 5–8 replicate columns 1–4 with the exception that we include four-digit SIC fixed effects and two-digit SIC × year fixed effects. We summarize characteristics of each model specification in the table footer.

Consistent with Hypothesis 1, we document a statistically and economically significant DiD estimator coefficient across all eight columns of Table 4. The coefficient on the DiD estimator in our most conservative estimation in column 8 is − 0.00489 (p value = 0.001). This coefficient suggests that the probability of a foreign takeover of a national security firm declines by approximately one-half of one percentage point after FINSA relative to the contemporaneous change for a non-national security firm. This is an economically significant impact because the unconditional probability of takeover in a firm-year in our sample is 2.1%. Overall, evidence tabulated in Table 4 strongly supports Hypothesis 1.

Control variable coefficients in Table 4 mirror the prior literature. Larger firms are more susceptible to foreign takeovers (e.g., Cremers et al., 2009; Karpoff et al., 2017), and less profitable firms with weaker sales growth are more likely to be subject to foreign takeover, consistent with the managerial disciplining effects of the market for corporate control (Manne, 1965).

Cross-sectional tests

We tabulate the estimation of Equation (1) across a variety of national security-related partitions in Table 5. For brevity, we estimate the most conservative specification reported in column 8 of Table 4. For convenient benchmarking, we copy the result first presented in column 8 of Table 4 into column 1 of Table 5. Hypothesis 2 predicts a negative coefficient on our DiD estimator, National Security Firm × Post-FINSA, in partitions comprising more research-intensive firms, firms with larger production capacity, and firms that were more susceptible to takeover market forces prior to FINSA.

Research intensity

We measure research intensity using the average values of pre-FINSA patent counts and patent citations and expect foreign ownership of research-intensive firms to present a relatively large national security threat via technology transfers (Moran, 2009). We measure production capacity using the average values of pre-FINSA sales and expect foreign ownership of high-production-capacity firms to present a larger national security threat due to dependencies the U.S. government may have on large U.S. firms (Moran, 2009). We measure pre-FINSA takeover probability using the predicted values from a takeover probability model (e.g., Karpoff et al., 2017; Table 4) estimated using pre-FINSA data. Across each pair of columns, we expect the DiD estimator coefficient in the high partition to be significantly more negative than in the low partition. We present p values indicating the statistical significance of differences in DiD estimator coefficients across partitions in the table footer.

With respect to the first cross-sectional results tabulated in columns 2 and 3, Hypothesis 2 predicts a larger negative coefficient in the High Patents partitions tabulated in column 3. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, the coefficient on the DiD estimator, National Security Firm × Post-FINSA, is approximately four times more negative in the High Patents partition than in the Low Patents partition (p value = 0.068). This result suggests that national security firms with high patents in the pre-FINSA period (i.e., those expected to draw more CFIUS scrutiny) see a larger decline in foreign takeovers after FINSA. The difference between the coefficients is statistically significant, as shown in the Table 5 footer (p value = 0.050). This first cross-sectional result is consistent with Hypothesis 2.

A concern regarding our use of patent counts is that large differences in the economic and technological significance across individual patents can make simple patent counts a noisy proxy for firms’ innovative output. To address this concern, we employ an alternate measure of research intensity that weighs patent observations using citations by subsequent patents. These patent citations capture the quality of innovation output (Hall et al., 2001). We split our sample based on patent citations in columns 4 and 5 of Table 5.

Hypothesis 2 predicts a more negative DiD estimator coefficient in the High Citations partition tabulated in column 5 because we expect FINSA-related barriers to foreign investment to increase with the extent to which foreign ownership presents a national security threat (Luo, 2021). Consistent with Hypothesis 2, we document a larger negative coefficient in the High Citations partition (p value = 0.051). The coefficient is approximately three times the magnitude of that reported in the Low Citations partition, suggesting that foreign takeovers decreased more for more research-intensive national security firms after FINSA. The statistical significance of the difference in the DiD estimator coefficients across partitions approaches conventional levels of statistical significance (p value = 0.149). This result provides additional, albeit modest, support for Hypothesis 2.

Production capacity

We examine whether the deterrent effect of FINSA on the foreign acquisitions of U.S. firms is larger for national security firms with greater production capacity and a greater potential to disrupt U.S. supply chains (Moran, 2009). We measure production capacity using firms’ average pre-FINSA sales. We tabulate the results in columns 6 and 7 of Table 5. Hypothesis 2 predicts a larger negative DiD estimator coefficient on the High Production Capacity partition. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, we document a statistically and economically significant DiD estimator coefficient in the High Production Capacity partition (p value = 0.014) while the DiD estimator in the Low Production Capacity partition is indistinguishable from 0. The difference between the DiD estimators across partitions is statistically significant (p value = 0.065). This result provides additional support for Hypothesis 2.

Pre-FINSA takeover probability

We conclude our cross-sectional tests by testing for variation in the cross-section of firms based on pre-FINSA takeover probability. If our hypothesis that FINSA reduces foreign takeovers is correct, then we expect that FINSA will most affect national security firms with a greater takeover likelihood in the pre-FINSA period. To generate the pre-FINSA probability of a foreign takeover for each firm-year, we first follow Cremers et al. (2009) and Karpoff et al. (2017) in constructing a takeover likelihood model. The model generates predicted takeover probability scores using pre-treatment (1990–2008) data. We partition firms in our sample using the predicted probability of foreign takeover with the partitions tabulated in columns 8 and 9 of Table 5. The coefficient on our DiD estimator, National Security Firm × Post-FINSA, is negative and statistically significant across both partitions. Consistent with our expectation, the DiD estimator has a larger negative coefficient in the High Takeover Probability partition than in the Low Takeover Probability partition. The difference between the coefficients is statistically significant (p value = 0.072). This result suggests that national security firms more likely to be taken over prior to FINSA are more negatively affected by FINSA’s impact on the takeover market. This test provides additional support for Hypothesis 1 by demonstrating that the relationship predicted in Hypothesis 1 varies predictably in the cross-section of national security firms.

Placebo tests: domestic takeovers

FINSA legislation affects only foreign investment. We leverage this feature of FINSA to mitigate correlated omitted variable bias concerns by replicating the foregoing analysis, instead examining domestic takeovers. Declines in the rates of U.S. firms acquiring U.S. national security firms (domestic takeovers) after FINSA suggest that a correlated omitted variable, and not FINSA itself, drives the changes we observe in the takeover market.

We tabulate these results in Table 6, which we structure to emulate the presentation of results in Table 5. The single difference between Tables 5 and 6 is that we code the dependent variable as equal to 1 when a firm is subject to a domestic instead of a foreign takeover. We first document in column 1 that the average effect of FINSA on domestic takeovers is statistically indistinguishable from 0. We observe similarly inconsequential DiD estimators across the research intensity, production capacity, and takeover probability partitions we examine, as tabulated in columns 2–11. Further documenting an orthogonal relationship between FINSA and domestic takeovers is that, as indicated in the table footer, DiD estimators across partitions are statistically indistinguishable from one another. That we are unable to document variation in domestic takeovers around FINSA corroborates FINSA as the mechanism driving the variation in foreign takeovers that we document.

Placebo tests: nominally small equity stakes in U.S. national security firms

Nominally small (< $100 million) equity purchases are less likely to yield the control rights necessary for determining, directing, or deciding matters affecting U.S. assets in a way that threatens national security. Accordingly, we predict no variation in the frequency of foreign investors acquiring nominally small equity stakes in national security firms following FINSA. To test this prediction, we replicate the analyses in Table 5 after replacing the dependent variable with an indicator variable capturing whether a foreign investor is purchasing a nominally small equity stake in a firm.

Table 7 documents no evidence that FINSA reduces foreign acquisitions of nominally small equity stakes in national security firms. These specifications include the full sample, where the DiD estimator is insignificant, as well as citation, production capacity, and takeover probability partitions, where the DiD estimators are statistically indistinguishable from one another.

Parallel trends assumption

Our research design assumes that the average change in foreign takeovers would have been the same for national security and non-national security firms after FINSA but for FINSA (parallel-trends assumption). Pre-treatment heterogeneity in foreign takeovers across treatment and control firms, for example, would confound our inference that post-treatment heterogeneity in foreign takeovers across treatment and control firms is attributable to FINSA. To address concerns regarding the validity of the parallel-trends assumption in our setting, we use a dynamic panel to demonstrate parallel pre-treatment foreign takeover trends across our treatment and control groups. We test the validity of this parallel-trends assumption by testing for differences in foreign takeovers in the pre-FINSA period using event-time DiD estimators.

We estimate a modified version of Eq. (1) in which we replace the DiD estimator National Security Firm × Post-FINSA with event-time DiD estimators National Security Firm × Year 2003 Indicator, National Security Firm × Year 2004 Indicator, … National Security Firm × Year 2016 Indicator. If the parallel trends assumption holds, we expect a coefficient on DiD estimators indistinguishable from 0 for pre-FINSA DiD estimators (National Security Firm × Year 2003 Indicator, … National Security Firm × Year 2008 Indicator).

We tabulate the results in column 1 of Table 8. Consistent with the validity of the parallel-trends assumption, we find that pre-FINSA DiD estimators are each indistinguishable from 0. DiD estimators statistically indistinguishable from 0 support the parallel trends assumption by documenting that the frequency of foreign takeovers of treatment and control firms was similar prior to FINSA. Column 1 of Table 8 also corroborates our main result. Starting in 2009, we begin observing fewer foreign takeovers of national security firms. This distinction spans well into the future with differences approaching or breaching conventional thresholds of statistical significance in 2009, 2011, 2014, 2015, and 2016. Overall, column 1 of Table 8 documents the validity of the parallel-trends assumption in our setting.

We corroborate our two placebo tests in columns 2 and 3 of Table 8. Columns 2 and 3 tabulate an event-time specification for the domestic takeover and nominally small equity stake placebo tests, respectively. Across both columns, we observe little variation in domestic takeovers or small foreign investments both before and after FINSA. This evidence supports the inferences we draw from Tables 6 and 7 and further suggests that treatment and control firms are similar but for FINSA.

Exogeneity of FINSA

Foreign investment screening laws that are endogenous to national security firm policies could threaten the credibility of our inferences. For example, treated firm influence over legislation is a major confound in the U.S. state-level antitakeover law literature14 and is an important feature of other regulatory settings. For example, despite the small number of lobbying firms in estimation samples used in the state antitakeover literature, Karpoff and Wittry (2017) find that the removal of lobbying firms from the estimation sample has a material impact on inferences drawn from the state antitakeover law setting. To address concerns that FINSA legislation is endogenous to treated firm policies, we compile data on lobbying activities related to FINSA and show that, of the 31 companies that lobbied for or against FINSA, 13 were U.S. companies.15 To address concerns that our results are driven by an endogenous relationship between lobbying firms and FINSA legislation, we (1) drop these 13 firms or (2) drop the industries in which these 13 firms are members and repeat our analysis with no change in inference (untabulated).

CONCLUSION

We investigate the effect of national security-related foreign investment screening laws on de-globalization. We employ FINSA as a source of variation in national security-related foreign investment screening laws and measure globalization using cross-border takeover activity. Congress passed FINSA to address growing national security concerns that foreign entities could exploit the U.S. takeover market to acquire critical technologies and disrupt supply chains (Moran, 2009). FINSA gives a regulator known as CFIUS broad new powers to revise or reject foreign acquisitions of U.S. firms deemed critical to national security. We use this regulation change and the groups of firms affected by it to provide the first study of the economic consequences of a U.S. securities regulation intended to improve national security.

Using a DiD research design, we document that the passage of FINSA significantly deterred foreign acquisitions of U.S. national security firms. The one-half of one percentage point decrease in the probability of a foreign takeover of a national security firm is statistically significant and represents an economically significant impact because the unconditional probability of takeover in our sample is 2.1%. This effect is stronger in national security firms for which a CFIUS intervention is more likely – those with more research-intensive activities and a greater ability to disrupt U.S. supply chains (Moran, 2009). On the other hand, we find little to no variation in takeovers of national security firms that are not affected by FINSA (domestic takeovers of national security firms and foreign acquisitions of nominally small equity stakes in national security firms), mitigating the influence of omitted variable bias in our analysis. Taken together, our evidence suggests that national security-related foreign investment screening laws are an economically significant factor driving de-globalization.

Our evidence documenting the effect of national security-related foreign investment screening laws on globalization contributes to the IB literature in several ways. First, our empirical approach offers readers a richly textured analysis documenting de-globalization determinants and trends. Our robust evidence should revise strong priors among some scholars that globalization is an irreversible process and that foreign investment screening laws only marginally affect globalization. As noted by Witt (2019: 1053), revising these prior beliefs is important because evidence of de-globalization “would induce a significant qualitative shift in strategies, structures, and behaviors in international business…require(ing) international business research to develop a much deeper integration of politics, the key driver of de-globalization.” An immediate implication is that our evidence strongly encourages MNE managers to increasingly weight the political factors behind foreign investment screening laws when assessing their foreign investment strategies.

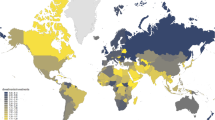

The empirical evidence we document may also foreshadow the effects of more recent U.S. legislation increasing CFIUS power as well as the effects of FINSA-type legislation being adopted worldwide. We encourage future research to examine the globalization effects of U.S. legislation following FINSA (i.e., the Foreign Investment Risk Reduction and Modernization Act of 2018, which expands CFIUS’s remit to include greenfield investments, joint ventures, and real estate) as well as the globalization effects of foreign investment screening laws adopted in 33 countries worldwide between 2002 and 2020 (OECD, 2020). In particular, we encourage researchers to leverage cross-country heterogeneity in foreign investment screening laws to help researchers and policymakers better understand how to evaluate the trade-off of benefits and costs between globalization and national security.

Last, we note that FINSA offers a rare source of exogenous variation in de-globalization, which permits an opportunity to test several predictions regarding the effects of de-globalization. For example, the FINSA setting can be used to investigate whether de-globalization has economically significant effects on a wide variety of outcomes of interest to IB scholars, including the cross-border diffusion patterns of not only superior management practices, advanced technologies, and related local labor specialization but also the cross-border transfer of gender equality, sustainability, and ethics (Ahlvik et al., 2016; Berry et al., 2010; Ellis et al., 2017).

NOTES

-

1

De-globalization is the process of weakening interdependence among nations (Witt, 2019).

-

2

Prior studies measure globalization using the ratio of foreign sales to total sales, whether or not a company has foreign activity (Errunza & Losq, 1985; Wiersema & Bowen, 2008), or asset and employee dispersion (Rugman & Verbeke, 2008). We measure globalization using cross-border acquisition activity in our setting because the foreign investment screening law we examine directly affects cross-border acquisition activity.

-

3

The impact on the real economy is also substantial as, in 2011 alone, majority-owned U.S. affiliates of foreign companies employed 5.6 million people, accounted for 15.9% of private R&D spending, and contributed 4.7% of total U.S. private sector output (Department of Commerce, 2013).

-

4

It is plausible that the definition of national security-related industries evolves over time. To test the stability over time of our definition of national security-related industries, determined in 2008, we examine how many CFIUS reviews involve target firms outside this definition. We infer from CFIUS Annual Reports that CFIUS scrutinized 2201 foreign investment notices between 2008 and 2016. Of these, 2090 (95%) relate to firms in industries included in CFIUS’s, 2008 list of national security-related industries.

-

5

Techno-nationalism is the belief that technology is a fundamental element in national security that must be stewarded carefully due to its utility in advancing nationalist agendas (Luo, 2021).

-

6

See the Foreign Investment and Risk Review Modernization Act of 2018 and the Foreign Investment and Economic Security Act of 2017, respectively.

-

7

In particular, our research design addresses the concern that prior methods of identifying strategic and non-strategic firms in IB literature is ad hoc and difficult to replicate (Buckley, 2020). We contribute to the IB literature by using publicly available CFIUS documents to objectively identify 61 industries U.S. regulators deem “strategic.” Future use of this classification will reduce measurement error in the IB literature when parsing strategic and non-strategic industries (e.g., Henisz et al., 2010; Li & Vashchilko, 2010; Petricevic & Teece, 2019).

-

8

The Dubai Ports World transaction was a regulatory tipping point because the CFIUS-approved deal triggered Congressional debates and media scrutiny that not only led to the unraveling of the Dubai Ports World transaction but also precipitated FINSA.

-

9

An example is “Tsinghua Unisplendour, a Chinese state-controlled company, which dropped plans to invest $3.8 billion in Western Digital, an American maker of computer hard-drives. The Chinese firm withdrew after the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, a government body, said it would review the deal” (The Economist [Espresso], February 24th, 2016). See Internet Appendix 2 for representative examples of CFIUS in the media.

-

10

Techno-nationalism characterizes technology as intrinsically related to national security, economic prosperity, and social stability (Graham & Marchick, 2006). Luo (2021) asserts that techno-nationalism has recently resurged.

-

11

For example, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act authorizes the president to prohibit certain transactions or block any property in which any foreign country or foreign national has any interest, the General Mining Law of 1872 inhibits foreign investors from owning valuable mineral deposits on U.S. lands, the Atomic Energy Act of 1954 inhibits foreign investors from owning assets in the nuclear industry, the Submarine Cable Landing License Act of 1921 permits the Federal Communications Commission to reject foreign investment if it assists in promoting the security of the United States, the Communications Act of 1934 inhibits foreign governments or their representatives (e.g., state-owned enterprises) from holding radio licenses, and the U.S. Transportation Code limits foreign investment in transportation industries.

-

12

We draw earnings conference call data from www.seekingalpha.com.

-

13

We use time-varying two-digit SIC fixed effects because time-varying four-digit SIC fixed effects would subsume our DiD estimator, National Security Firm × Post-FINSA; National Security Firm is equal to 1 for firms in national security industries where CFIUS defines national security industries at the four-digit SIC level (CFIUS, 2008).

-

14

See, e.g., Karpoff and Wittry (2017); and Werner and Coleman (2015).

-

15

Of the 13 companies, several were directly involved in the M&A business with no apparent vested interest in protecting managerial entrenchment. The lobbying firms were Boeing Company, Carlyle Group, Conoco Philips, EDS Corporation, Exxon Mobil, General Electric, Goldman & Sachs, Halliburton, JP Morgan Chase, Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, United Technologies Corporation, and Xcel Energy.

REFERENCES

Ahlvik, C., Smale, A., & Sumelius, J. 2016. Aligning corporate transfer intentions and subsidiary HRM practice implementation in multinational corporations. Journal of World Business, 51(3): 343–355.

Aktas, N., de Bodt, E., & Roll, R. 2004. Market response to European regulation of business combinations. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 39(4): 731–758.

Arpan, J., Flowers, E., & Ricks, D. 1981. Foreign direct investment in the United States: The state of knowledge in research. Journal of International Business Studies, 12(1): 137–154.

Arpan, J., & Ricks, D. 1974. Foreign direct investment in the United States and some attendant research problems. Journal of International Business Studies, 5(1): 1–8.

Bass, A., & Chakrabarty, S. 2014. Resource security: Competition for global resources, strategic intent, and governments as owners. Journal of International Business Studies, 45: 961–979.

Berry, H., Guillén, M. F., & Zhou, N. 2010. An institutional approach to cross-national distance. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(9): 1460–1480.

Bertrand, M., & Mullainathan, S. 2003. Enjoying the quiet life? Corporate governance and managerial preferences. Journal of Political Economy, 111(5): 1043–1075.

Bhagwat, V., Dam, R., & Harford, J. 2016. The real effect of uncertainty on merger activity. The Review of Financial Studies, 29(11): 3000–3034.

Bonaime, A., Gulen, H., & Ion, M. 2018. Does policy uncertainty affect mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Financial Economics, 129(3): 531–558.

Buckley, P. 2020. The theory and empirics of the structural reshaping of globalization. Journal of International Business Studies, 51: 1580–1592.

Buckley, P., Clegg, J., Voss, H., Cross, A., Liu, X., & Zheng, P. 2018. A retrospective and agenda for future research on Chinese outward foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 49: 4–23.

Byrne, M. 2006. Protecting national security and promoting foreign investment: Maintaining the Exon-Florio balance. Ohio State Law Journal, 67(4): 849–910.

CFIUS. 2008. Annual report to Congress. Public/unclassified version. U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Contractor, F. 2021. The world will need even more globalization in the post-pandemic 2021 decade. Journal of International Business Studies, 53: 156–171.

Cremers, K., Nair, V., & John, K. 2009. Takeovers and the cross-section of returns. Review of Financial Studies, 22(4): 1409–1445.

Department of Commerce. 2013. Foreign direct investment in the United States. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2013/10/31/new-report-foreign-direct-investment-united-states. Accessed 14 January 2021.

Dinc, S., & Erel, I. 2013. Economic nationalism in mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Finance, 68(6): 2471–2514.

Eden, L. 2009. Letter from the editor-in-chief: FDI spillovers and linkages. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(7): 1065–1069.

Ellis, J. A., Moeller, S. B., Schlingemann, F. P., & Stulz, R. M. 2017. Portable country governance and cross-border acquisitions. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(2): 148–173.

Errunza, V., & Losq, E. 1985. International asset pricing under mild segmentation: Theory and test. Journal of Finance, 40(1): 105–124.

Federal Register. 2008. Regulations pertaining to mergers, acquisitions and takeovers by foreign persons. 31 CFR Part 800 RIN 1505-AB88.

Fieberg, C., Lopatta, K., Tammen, T., & Tideman, S. 2021. Political affinity and investors’ response to the acquisition premium in cross-border M&A transactions—A moderation analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 42(13): 2477–2492.

Fratteroli, M. 2020. Does protectionist anti-takeover legislation lead to managerial entrenchment? Journal of Financial Economics, 136(1): 106–136.

GAO. 2008. Foreign investment laws and policies regulating foreign investment in 10 countries. GAO-08-320.

GAO. 2009. Sovereign wealth funds: Laws limiting foreign investment affect certain U.S. assets and agencies have various enforcement processes. GAO-09-608.

GAO. 2015. Critical technologies: Agency initiatives address some weaknesses, but additional interagency collaboration is needed. GAO-15.288.

GAO. 2018. CFIUS: Treasury should coordinate assessments of resources needed to address increased workload. GAO-18-249.

Graham, E., & Marchick, M. 2006. U.S. national security and foreign direct investment. Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics.

Grosse, R., & Trevino, L. 1996. Foreign direct investment in the United States: An analysis by country of origin. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(1): 139–155.

Gu, F., & Lev, B. 2011. Overpriced shares, ill-advised acquisitions and goodwill impairment. The Accounting Review, 86(6): 1995–2022.

Hainmueller, J. 2012. Entropy balancing for causal effects: A multivariate reweighting method to produce balanced samples in observational studies. Political Analysis, 20(1): 25–46.

Hall, B., Jaffe, A., & Trajtenberg, M. 2001. The NBER patent citations data file: Lessons, insights and methodological tools. Working paper 8498, NBER.

Harford, J. 2005. What drives merger waves? Journal of Financial Economics, 77(3): 529–560.

Harris, R., & Ravenscraft, D. 1991. The role of acquisitions in foreign direct investment: Evidence from the US stock market. Journal of Finance, 46(3): 825–844.

Henisz, W., Mansfield, E., & Von Glinow, M. 2010. Conflict, security and political risk: International business in challenging times. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(5): 759–764.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) 2020. IMF annual report 2020: A crisis like no other. Washington, D.C.: IMF.

Jackson, J. 2018. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). Congressional Research Service, 7-5700.

Jens, C. 2017. Political uncertainty and investment: Causal evidence from U.S. gubernatorial elections. Journal of Financial Economics, 124(3): 563–579.

Karpoff, J., Schnolau, R., & Wehrly, E. 2017. Do takeover defense indices measure takeover deterrence? Review of Financial Studies, 30(7): 2359–2412.

Karpoff, J., & Wittry, M. 2017. Institutional and legal context in natural experiments: The case of state antitakeover laws. Journal of Finance, 73(2): 657–714.

Kim, W., & Lyn, E. 1987. FDI theories, entry barriers, and reverse investment in U.S. manufacturing industries. Journal of International Business Studies, 18(2): 53–66.

Kobrin, S. 2017. Bricks and mortar in a borderless world: Globalization, the backlash, and the multinational enterprise. Global Strategy Journal, 7(2): 159–171.

Li, Q., & Vashchilko, T. 2010. Dyadic military conflict, security alliances, and bilateral FDI flows. Journal of International Business Studies, 41: 765–782.

Luo, Y. 2021. Illusions of techno-nationalism. Journal of International Business Studies, 53: 550–567.

McGaughey, S., Raimondos, P., & la Cour, L. 2020. Foreign influence, control, and indirect ownership: Implications for productivity spillovers. Journal of International Business Studies, 51: 1391–1412.

McMullin, J., & Schonberger, B. 2020. Entropy balanced accruals. Review of Accounting Studies, 25: 84–119.

Maksimovic, V., Phillips, G., & Yang, L. 2013. Private and public mergers. Journal of Finance, 68(5): 2177–2217.

Manne, H. 1965. Mergers and the market for corporate control. Journal of Political Economy, 73(2): 110–120.

Moran, T. 2009. Three threats: An analytical framework for the CFIUS process. Washington, D.C.: Petersen Institute for International Economics.

OECD. 2020. Acquisition- and ownership-related policies to safeguard essential security interests: Current and emerging trends, observed designs, and policy practice in 62 countries. Research Note by the OECD Secretariat.

Petricevic, O., & Teece, D. 2019. The structural reshaping of globalization: Implications for strategic sectors, profiting from innovation, and the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 50: 1487–1512.

Rose, P. 2014. The Foreign Investment and National Security Act of 2007: An assessment of its impact on sovereign wealth funds and state-owned enterprises. Working paper, Ohio State University.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. 2008. A new perspective on the regional and global strategies of multinational services firms. Management International Review, 48(4): 397–411.

SDC, 2019. SDC Platinum. Thomson Reuters. Available at: WRDS. Accessed April 2019.

Shipman, J., Swanquist, Q., & Whited, R. 2016. Propensity score matching in accounting research. The Accounting Review, 92(1): 213–244.

Tallman, S. 1988. Home country political risk and foreign direct investment in the United States. Journal of International Business Studies, 19(2): 219–234.

Verbeke, A., Coeurderoy, R., & Matt, T. 2018. The future of international business research on corporate globalization that never was…. Journal of International Business Studies, 49: 1101–1112.

Wan, K.-M., & Wong, K.-F. 2009. Economic impact of political barriers to cross-border acquisitions: An empirical study of CNOOC’s unsuccessful takeover of Unocal. Journal of Corporate Finance, 15(4): 447–468.

Werner, T., & Coleman, J. 2015. Citizens United, independent expenditures and agency costs: Reexamining the political economy of state antitakeover statutes. Journal of Law, Economics and Organizations, 31: 127–159.

Wiersema, M. F., & Bowen, H. P. 2008. Corporate diversification: The impact of foreign competition, industry globalization, and product diversification. Strategic Management Journal, 29(2): 115–132.

Witt, M. 2019. De-globalization: Theories, predictions, and opportunities for international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 50: 1053–1077.

World Investment Report 2020. International production beyond the pandemic. Geneva: UNCTAD.

World Trade Organization (WTO) 2017. World trade statistical review 2017. Geneva: WTO.

Xu, E. 2017. Cross-border merger waves. Journal of Corporate Finance, 46: 207–231.

Zaring, D. 2010. CFIUS as a congressional notification service. Southern California Law Review, 83(1): 81–132.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS