Abstract

This article analyses the institutional conditions required to support a strategic state in being responsive to the changing demands of a market-economy, whilst maintaining a credible commitment to long-term policy goals. This article identifies a key pillar of a market economy that we believe is crucial to promoting inclusive economic growth; we term these institutions market-engaging institutions. We propose that market-engaging institutions may form a bridge between the flexibility required by a dynamic market economy and the stability demanded by the rule of law. We define market-engaging institutions as those institutions that facilitate greater political participation for marginalized groups, manage technological disruptions, and support human capital formation. Examples include social partnership agreements, collective bargaining coverage, trade union membership, education and training services, and research and development programmes. We suggest that mobilizing these institutions necessitates credible commitment. Further, we argue that through its commitment to the non-arbitrary administration of general rules the rule of law is an essential condition for signalling the state’s credible commitment. However, at times the requirement for the state to be flexible to the changing needs of market actors may conflict with the rule of law’s demand for constancy and stability. This article examines the delicate balancing act required to sustain a strategic, responsive, and credible state in an era of institutional flux.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

According to Fritz (2021), we have entered an era of institutional flux in which “new institutional capabilities need to be developed or redeveloped to buffer citizens and businesses through acute crises and longer-term transitions.” These institutions must be responsive to exogenous shocks such as financial crises and pandemics, as well as endogenous (i.e., self-produced) changes, particularly technological innovations. Yet institutions must also be coherent and consistent; their integrity relies on strong rule of law. Recently, the World Bank reported that “political polarization, fragmentation and populism undermine institutional coherence through policy shifts combined with frequent changes in public sector staffing and organizational structures” (Fritz 2021). These incoherencies weaken accountability and leave the state vulnerable to capture. Therefore, understanding how to balance the need for responsiveness with the need for coherence is a pressing issue in this era of institutional flux.

In response, this article identifies a key pillar of a market economy that we believe is crucial to promoting inclusive economic growth; we term these institutions market-engaging institutions. We define market-engaging institutions as a bundle of institutions that facilitate greater political participation for marginalized groups, manage technological disruptions, and support human capital formation. Examples include social partnership agreements, collective bargaining coverage, trade union membership, education and training services, and research and development programs. These institutions may be delivered by the state or in partnership with private actors. We suggest that if these institutions are to be functional and factor in the practical deliberations of legal subjects and market actors then they must be underpinned by a credible commitment. We observe that, through its commitment to the non-arbitrary administration of general rules, the rule of law signals the credibility of the state’s commitment to long-term policy goals.

However, at times the requirement for the state to be flexible to the changing needs of market actors may conflict with the rule of law’s demand for constancy and stability. To date, there has been a paucity of scholarly engagement with the question of how the state remains flexible to the changing needs of a market economy whilst also providing the requisite coherence and consistency demanded by the rule of law. We propose that market-engaging institutions may form a bridge between these competing priorities—flexibility and certainty. This article is a first foray into our understanding of market-engaging institutions. Consequently, we have narrowed our discussion to consider advanced market-economies. Future research on the role market-engaging institutions play in authoritarian regimes, socialist economies or in lower-and-middle income countries would be welcomed.

We first situate our research question within the literature on institutional theory and identify the contribution this article makes to progressing the discourse on institutions, particularly as they relate to the rule of law and the strategic state (Sect. 2). We follow the OECD (2013, p. 58) definition of a strategic state as “a government that can articulate a broadly supported long-term vision for the country, identify emerging and longer term needs correctly, prioritize objectives, identify medium- and short-term deliverables, assess and manage risk, strengthen efficiencies in policy design and service delivery to meet these needs effectively, and mobilize actors and leverage resources across society to achieve integrated, coherent policy outcomes in support of the visions.” Despite this robust definition there is still little known about the specific measures required to establish a strategic state (Elliott 2020).

In response, we identify a bundle of institutions which underpin a strategic state: market-engaging institutions. We suggest that these institutions help manage the interdependencies and conflicts among technological change, human capital formation, political participation, and the rule of law (Sect. 3). To support our hypothesis that market-engaging institutions may promote inclusive growth, we present a case study of Ireland’s development model (Sect. 4). Ireland was identified as a suitable case study as its development path illustrates the formation of a strategic state (OECD 2013) through the use of market-engaging institutions. Ireland is an advanced economy that underwent rapid transformation since its independence in 1937. According to the World Bank (2015), Ireland is one of few countries that has managed to transition from middle-income status to higher-income status, making it a particularly interesting case study. Section 4 illustrates the central role market-engaging institutions played in this transition.

Finally, we conclude that there appears to be a positive correlation between institutions that support human capital formation and political participation (i.e., market-engaging institutions) and lower rates of inequality, when these institutions are delivered with a credible commitment (i.e., in accordance with the rule of law). These findings warrant further theoretical and empirical inquiry into market-engaging institutions.

2 Situating Market-Engaging Institutions in the Literature on Institutions and the Strategic State

This section reviews the literature on institutions and the strategic state (Sect. 2.1), situates the discourse on the rule of law in the literature on market-supporting institutions (Sect. 2.2), and identifies the research gap this article seeks to address (Sect. 2.3).

2.1 Institutional Theory and the Strategic State

As Drumaux and Joyce (2018, p. 1) observe, “creating effective and credible government has become a big issue in the last 25 Years.” Beginning with the interventions of Douglass North, forefather of new institutional economics, a body of literature has emerged to question the neoliberal ideology of minimal state intervention and deregulation as a means to promote the development of a market economy. Rather, North and his followers have emphasised the need for strong state-delivered institutions that support a market economy. In many ways, new institutional economists take the Polanyian perspective (Polanyi 2001) of the “free market” as a myth as their starting point. However, they have equally cautioned that good institutions must be supported by good governance. Good governance refers to the traditions and institutions by which authority is exercised in a country, and includes the process by which governments are selected, monitored, and replaced, the government’s capacity to effectively formulate and implement policies, and the overarching respect for the institutions governing economic and social interactions. As we will explore throughout this article, the rule of law is considered key for good governance and good institutions.

Institutions are the rules of the game or, more formally, the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction (North 1990, p. 3) and set expectations (Yifu Lin and Nugent 1995, p 2306–7). Institutions may be informal or formal in nature. Helmke and Levitsky (2004, p. 727) define informal institutions as “socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels” and formal institutions as “rules and procedures that are created, communicated, and enforced through channels widely accepted as official.” Institutions increase predictability and reduce uncertainty by providing a framework for human interaction (North 1990, p. 6). In essence, they are vehicles through which information on standards of conduct circulate, and thus close the information gap between social, political, and economic actors. Through this increased certainty, these institutions should decrease transaction costs and encourage investment, ultimately stimulating economic growth.

Shirley (2008) identified two distinct institutional frameworks that are crucial for economic growth; institutions that foster exchange by lowering transaction costs and encouraging trust and institutions that limit abuse of state power and protect private property and persons. Rodrik and Subramanian (2003) provide a somewhat more encompassing typology with their four institutional dimensions of a market economy: market-creating, market-regulating, market-stabilizing, and market-legitimizing institutions. These four institutions support a market economy by: providing private property rights and contract enforcement (i.e., market-creating institutions), dealing with externalities, economies of scale and imperfect information (i.e., market-regulating institutions), ensuring low inflation, minimizing macroeconomic volatility, and averting financial crises (i.e. market-stabilizing institutions), and providing social protection and insurance, redistribution, and conflict management (i.e. market-legitimizing institutions). This typology of institutions captures the present state of our understanding of the institutions that support a market economy.

To this typology we could add Mazzucato’s (2018) understanding of the state as an “entrepreneurial” actor in the market. On Muzzacato’s account, the state is a key-driver of innovation-led growth, having contributed to technological innovations such as the Internet, GPS, biotechnology, nanotechnology, and alternative energy sources. These early public investments at the risky stage of the innovation cycle have produced new technologies and emergent markets that were later exploited by private actors. Rather than a public–private divide, Mazzucato finds a dynamic public–private partnership. States that do not invest in technological disruption, Mazzucato suggests, tend to stagnate.

In sum, institutional theory has revived our understanding of the state as a key actor in supporting and promoting a dynamic market economy. The state provides a framework of general rules through which economic actors may engage in impersonal transactions with confidence, regulates otherwise volatile aspects of the economy, and mitigates the negative externalities of the market through the provision of regulatory bodies and social services. We use the term “dynamic economy” to refer to the process of creative destruction that is a key characteristic of a market economy. Capitalism requires the constant reshaping of markets, products, and services. From the Schumpeterian perspective (Schumpeter 2010), technological mutations or disruptions (i.e., creative destruction) produce emergent economies that alter the landscape of labour/capital relations (Piazza-Georgi 2002, p. 463). As such, a capitalism economy is ever-changing or dynamic.

Creative destruction should temporarily push society and the market into a state of social disequilibrium as existing markets are destroyed and resources (including labour) are reallocated. A state of social disequilibrium is characterised by the emergence of new markets, and the corresponding alteration of the roles, rights, and duties of market actors. We argue that depending on how a dynamic economy is managed by the state, a period of disequilibrium may persist and produce or exacerbate inequalities between labour and capital, or open opportunities, new markets, and technologies to a broader segment of society. While Mazzucato (2018) highlights the role of the state in stimulating creative destruction, this article explores the role of the state in exiting a period of disequilibrium. Therefore, our market-engaging institutions are primarily concerned with managing labour/capital relations.

2.2 Institutional Theory and the Rule of Law

Running through institutional theory is an overarching concern for the rule of law. Through its capacity to protect persons, property, and contract rights, to restrain the arbitrary use of government power, and to reduce corruption, the rule of law has been identified as a precondition for a well-functioning market economy (Ramanujam and Farrington 2022, p. 160–61). The rule of law provides the structural constancies required to govern through general rules. To guide human behaviour, legal rules must be of general application, publicized, prospective, intelligible, non-contradictory, possible to comply with, stable, and congruent (Fuller 1969). These so-called precepts of legality are the minimum conditions required to create a stable framework of rules that can factor in the practical reasoning of legal subjects. In turn, a stable legal system provides a base level of expectations upon which strangers may form exchange-based relationships. As exchange-based economies grow, expanding in terms of both space and time, mechanisms for enforcing contracts become increasingly important (Greif 1993). Where an agreement is made for the future performance of an obligation, or the performance of an obligation by parties in differing jurisdictions, informal trust-based agreements often become insufficient mechanisms for exchange. Instead, more formalised systems are required to ensure that actors, acting across space and time, can transact with confidence. In other words, the rule of law provides a credible commitment from the state when delivering market-supporting institutions.

The idea of consistency across government policy is captured in the idea of a strategic state. As stated above, the OECD define a strategic state as one which provides a long-term vision for the country which it delivers through coherent medium- and short-term goals. The emphasis on stability over time accords well with our understanding of the rule of law as concerned with stabilizing expectations between legal subjects. In essence, the rule of law provides the foundation upon which the pillars of a market economy (i.e., market creating, stabilizing, regulating and legitimizing institutions) may be erected.

2.3 Bridging the Gap Between a Strategic State and a Dynamic Market Economy

There is an outstanding question of how a strategic state provides the requisite stability of expectations required by the rule of law, and remains responsive to the changing dynamics of a market economy. This article provides a conceptual framework for understanding how a strategic state can be both consistent and responsive, without undermining the credibility of its commitment to long term policy goals. We are concerned that an unresponsive state could produce unintended inequalities by enforcing legal rules that are incongruent with contemporary needs. There is widespread consensus that inequality is rising within high-income countries (Atkinson 2015; Cingano 2014; Irvine 2008; Piketty 2017). A report by the OECD found that “the gap between rich and poor is at its highest level in 30 years. Today, the richest 10 per cent of the population in the OECD area earn 9.5 times the income of the poorest 10 per cent; in the 1980s this ratio stood at 7:1 and has been rising continuously” (Cingano 2014, p. 6). There is also growing concern that a post-pandemic recovery will be uneven unless a “human-centric” approach is adopted—one that tackles inequality while stimulating economic growth (ILO 2021). Understanding how to build a human-centric state requires further research and experimentation.

Building on Rodrik and Subramanian’s (2003) typology, this article adds another dimension to the four previously identified market-supporting institutions. This article aims to expand our understanding of the state’s role in promoting inclusive growth through the provision of market-engaging institutions. Each institution plays an important and interconnected role in supporting a market economy. Market-creating institutions provide the formal institutions necessary for an exchange-based economy in the form of contract and property rights, and the associated legal architecture to support the administration and enforcement of those rights. Market-regulating and -stabilizing institutions provide the infrastructure to support economies of scale and minimize economic volatility. These institutions guard against macroeconomic shocks that have serious distributional consequences, such as tax increases or public service cuts (Rodrik and Subramanian 2003, p. 32). However, outside of macroeconomic crises, these institutions leave the distributional outcomes of the market to freedom of contract. Perhaps for this reason, market-legitimizing institutions have entered the picture.

There is evidence that market-legitimizing institutions may offset the negative externalities of a free market by providing better unemployment insurance provisions (Aghion et al. 2016), active immigration policies, and housing rights (Berger 2016). However, these responses have been described as neither adequate nor credible as they fail to balance the interests of labour and capital(Frenken and Schor 2019, p. 131), and are at best a palliative solution for a problem that is endemic to capitalist societies (i.e., creative destruction). Recently, there have been more progressive and ambitious proposals aimed at tackling inequality including progressive income taxation (Stiglitz 2014, 2019), a global wealth tax (Piketty 2017), and universal basic income (Standing 2017). Each of these solutions focus on changing the way the state generates and redistributes its income. As such, they are more concerned with market-legitimizing institutions.

We recognize the importance of market creating, stabilizing, and regulating institutions to providing the formal institutions for a well-functioning exchange-based economy. We also recognise the important role market-legitimizing institutions play in mitigating the distributional inequalities that may arise when economic freedoms are prioritized. However, we posit that these institutions alone are insufficient to reverse the inequality phenomenon or to fairly balance the interests of labour vis-à-vis capital. We believe that the state must also extend engagement in economic and political life to a broad segment of society. This need for engagement and responsiveness, however, must be carefully balanced with the need for consistency in economy policy over time. In this article, we build on the abovementioned literature to propose a fifth institutional dimension of the market economy—market engaging institutions.

3 Towards Market-Engaging Institutions

This section defines the parameters of our market-engaging institutions. We define market-engaging institutions as those institutions that promote inclusive political participation, manage technological disruptions, and support human capital formation through the provision of skill-training and education. Examples include social partnership agreements, collective bargaining coverage, trade union membership, education and training services, and research and development programs. In essence, market-engaging institutions are built on two pillars—human capital formation (Sect. 3.1) and political participation (Sect. 3.2). Together these pillars help manage conflicts between labour and capital. Most importantly, there must be a credible commitment to these policies, predictability in rulemaking, and long-term consistency in public policy. We begin by looking at the importance of human capital for maintaining social equilibrium or exiting a period of technological disruption. We then consider how the capacity of the state to provide the appropriate institutions for human capital formation is predicated on the ability of a broad segment of society to engage in political life and the state’s commitment to the rule of law.

3.1 The First Pillar of Market-Engaging Institutions: Human Capital Formation

Human capital is commonly defined as “the stock of personal skills that economic agents have at their disposal in addition to physical capital” (Piazza-Georgi 2002, p. 463). It comprises skills, stocks-of-knowledge, and entrepreneurship (Piazza-Georgi 2002, p. 461). Despite its central importance to a market economy, interest in human capital has often been overshadowed by inquiry into physical capital. Physical and human capital have some features in common, but their distinguishing features are perhaps more interesting. Capital is “a productive resource that is the result of investment” (Piazza-Georgi 2002, p. 462). No resource on its own is productive; for a resource to be transformed into capital, it requires investment. Human capital is no different. A distinguishing feature of human capital is that its stocks increase with use, rather than depleting like its physical counterparts. Human capital also does not suffer from diminishing returns; the wider its dispersion among individuals, the greater the returns (Piazza-Georgi 2002). In contrast to physical capital, distributional inequalities in human capital impact efficiency and productivity (Piazza-Georgi 2002).

For physical capital, capital concentration has been linked to greater productivity. As such, at an early stage of development, there has been some evidence that inequality is positively correlated with growth (Banerjee and Duflo 2003; Barro 2000). However, this falls away in the long run, and once we begin to include human capital inequality in the equation the picture becomes more complex. Castelló and Doménech (2002, p. 189) show that “human capital inequality negatively influences economic growth rates not only through the efficiency of resource allocation but also through a reduction in investment rates.” Similarly, Belitz et al (2015, p. 455) find that, in developed economies, “an increase of one percentage point in research and development spending in the economy as a whole [led] to a short-term increase in GDP growth of approximately 0.05 to 0.15 percentage points.” Cingano (2014, p. 6) discovered that inequality negatively impacts growth due to the impact on human capital accumulation; his analysis showed that income disparity depresses skills development and reduces long-term growth prospects. Therefore, investing in human capital, particularly policies directed at low- and middle-skilled workers will likely increase overall growth.

To put it crudely, anyone that does not have access to education due to economic, social, or cultural barriers is an untapped resource. Innovation, and research and development catalyse technological change while entrepreneurs are important equilibrating agents. These aspects of human capital—skills, innovation, and entrepreneurship—maintain the cycle of creative destruction and are preconditions for sustained economic growth. However, we submit that, in many respects, human capital can be understood as both the entry point into social disequilibrium (through technological disruption) and the exit point toward social equilibrium.

Exit from social disequilibrium can be facilitated through investment in education, upskilling, and perhaps most importantly making stocks-of-knowledge more publicly available. Stocks-of-knowledge encompass “stored expertise” (Piazza-Georgi 2002, p. 464) in various formats from books to data banks. As such, it is unsurprising that recent research has found that libraries are a vital bridge across the “digital divide”, i.e., the gap between those who have access to digital technologies and those who do not (Allmann et al. 2021). If we wish to fully comprehend the process of endogenous change in income and technology, we need to begin to appreciate the role human capital plays in exiting social disequilibria. We suggest that without market-engaging institutions, society will persist in a state of social disequilibrium, and we will continue to see a rise in income inequality.

There is emerging data to support this suggestion. For instance, Lee and Lee (2018) found evidence from a cross-country analysis that a more equal distribution of education significantly impacts income inequality. On the other hand, the study showed that higher per capita income, trade openness and, technological change have a positive impact on income inequality—but that this could be counteracted by more equal distribution of education. As such, Lee and Lee (2018) identify the source of rising income inequality within East Asian economies as rapid income growth, globalization, and technological change in the absence of income-equalizing policies that improve equal access to education. Glomm and Ravikumar (1992), Saint-Paul and Verdier (1993), and Galor and Tsiddon (1997) have all provided evidence that uneven distribution of human capital is a key source of inequality. As such, growth in the absence of market-engaging institutions will, we suggest, remain uneven.

Similarly, Andersen (2015) emphasises that passive means of redistribution via taxes and transfers (i.e., market-legitimizing institutions) are unlikely to be sufficient to reverse the trend of growing inequality. Andersen (2015, p. 7) explains that “the distribution of qualification is an important factor in determining the distribution of market incomes. The wage distribution is formed via the interaction between labour demand and supply.” Consequently, the more unequal the distribution of qualifications the more unequal the distribution of market incomes. Most interestingly, and contrary to popular opinion, the egalitarian outcomes of Nordic countries may be more a result of an equal distribution of qualifications than of redistribution via taxes and transfers (Andersen 2015, p. 8). As such, the first pillar of market-engaging institutions is human capital formation which provides an important exit point from the social disequilibrium caused by technological change.

However, in general, access to market-engaging institutions has been uneven. There is a broad consensus that “both new technologies and globalization tend to induce a skill bias in labour demand; that is, job creation tends to be concentrated at the top of the qualification distribution, while job destruction is concentrated at the lower end” (Andersen 2015, p. 12). This bias towards high-skilled workers, in conjunction with their privileged position in the private sector, disadvantages low-and-medium skilled workers.

Therefore, we need mechanisms to ensure continued and equal access to institutions that provide for human capital formation. According to Goldin (2016) initial distributions of wealth affect human capital across generations; the stock of human capital that an individual is able to accumulate is dependent on the investment their parents are capable of committing to. Children’s future participation in the labour market is largely determined by their initial access to education, which is determined by neither their natural ability nor work ethic but by their parents (Shuey and Kankaraš 2018; OECD 2018; van Belle 2016). As such, the idea that the market will reward those that work hard enough can only be sustained if there is an even playing field from the start. Removing these contingencies (wealthy and altruistic parents) requires the state to intervene to ensure equal access to education and knowledge. Investment in human capital must be inclusive, encompassing those traditionally excluded, such as women (OECD 2020a, 2018, 2021), children from lower-income backgrounds (OECD 2020b), migrants and their children (OECD 2020c), and low skilled workers (ILO 2021). This requires a state that is not solely or primarily responsive to the interests of powerful economic actors or—in other words, a state that is not subject to capture.

3.2 The Second Pillar of Market-Engaging Institutions: Participation and the Rule of Law

Acemoglu et al (2014) pick up on the importance of inclusive institutions for human capital formation. They argue that studies purporting to measure human capital are in fact capturing the effect of institutions, and once controlled for the impact of human capital is not as significant as studies would suggest. We suggest that human capital and inclusive institutions are interdependent and mutually supportive. A more recent study commissioned by the IMF (Baldaci 2004) found that public spending increases growth where it improves the education and health services required to build human capital. However, the impact of social spending on economic growth is directly affected by governance.

In simple terms, governance refers to the way public power is exercised (Kaufmann et al. 1999). Poor governance may produce inefficiencies when delivering public services. More troublesome, poor governance allows corruption to thrive. On the other hand, good governance occurs when public power is exercised with due regard for the rule of law and constraints are placed on the arbitrary use of power. As a result, the rule of law has been identified as a key tool in the fight against corruption and state capture (Edgardo Campos et al. 1999; Hongdao et al. 2018). Therefore, while education and human capital formation matter, equally important are the processes through which those policies are delivered.

The interdependence of inclusive institutions and human capital has also been emphasised by the World Bank. The World Bank (2006, p. xiv) found that “rich countries are largely rich because of the skills of their populations and the quality of the institutions supporting economic activity.” Intangible capital, which includes raw labour, human capital, social capital (i.e., the trust among people in society and their ability to work together), governance and the quality of institutions are key components of development (World Bank 2006). Importantly, the rule of law was linked to higher wealth and a higher intangible capital residual (World Bank 2006). As such, there appears to be a two-way relationship between inclusive institutions and human capital. Good or inclusive institutions and human capital are both intangible components of wealth, they allow a broader segment of society to engage in economic life, thus increasing gains and equalizing their distribution.

There is a wealth of literature on inclusive institutions (Acemoglu 2003; Acemoglu et al. 2001; Rodrik 2000a; Rodrik and Subramanian 2003). To date, inquiry into inclusive institutions has been concentrated on market-creating institutions and has consequently focused predominantly on those institutions that limit government, reduce transaction and production costs, and protect market actors’ freedoms. Within this category of inclusive institutions lies the rule of law, private property rights, and contractual freedoms. Yet, it is open to debate whether the rule of law, in and of itself, can promote an inclusive economic or political system (Bennett 2011; Kramer 2004). The rule of law provides the conditions for the consistent application of general rules to human behaviour. According to Raz, the negative virtue of the rule of law is that it guards against the potential for legal rules to be used arbitrarily (Raz 2009). The rule of law may support legal subjects in forming expectations on the behaviour required of them and others, but if the substantive content of the legal rules is oppressive, their rigid application could be used for exclusionary purposes. On this point Kramer (2004, p. 69) cautions that, the advantages of the rule of law are the same for both just and unjust rulers, and that “if power-hungry rulers are determined to exert and reinforce their repressive sway for a long period over a sizeable society, their efforts will be severely set back if they do not avail themselves of the coordination and the incentive-securing regularity made possible by the rule of law.”

Perhaps it is for this reason that Acemoglu, Johnson and Robinson (AJR) emphasised that inclusivity also depends on whether some degree of equal opportunity is available to a broad segment of society so that individuals can make investments, especially in human capital, and participate in productive economic outcomes (Acemoglu 2003). These important aspects of inclusive institutions have been eclipsed by the interest in market-creating institutions. However, without the second pillar of market-engaging institutions that expand political participation to a broader segment of society, growth may, we suggest, be uneven. Indeed, a strategic state that rigidly applies legal rules over a consistent period may find itself disadvantaging rather than empowering economic actors where those rules or policies are incongruent with contemporary needs. Therefore, market-engaging institutions and the rule of law appear to be interdependent prerequisites for an inclusive state. Together they empower the state to adapt to technological disruptions and exogenous shocks in a non-arbitrary fashion.

In support of the primacy of participatory institutions, studies have found that inequality rises, and labour share of income decreases as voices are silenced, and trade unions and collective bargaining agreements are dismantled (McGaughey 2016; Palma 2011). Rodrik (2000b), Stiglitz (2002), and Isham et al. (1995) find that consensus-building, open dialogue, and the promotion of an active civil society produce more sustainable growth, greater resistance to economic shocks, and deliver better distributional outcomes. Rodrik and Subramanian (2003) and Acemoglu and Robinson (2013) suggest that institutions of public deliberation and collective choice are required to identify complementarities between institutions, the incentive effects of alternative arrangements, the relevant trade-offs of such arrangements, and the impact of the removal of market failures on future political stability.

Therefore, exiting social disequilibria requires more than fixing prices, privatizing resources, or improving institutions; it requires inclusive investment in human capital which can only occur through participatory processes that are transparent and accountable. Participation means more than voting, it requires open dialogue and active engagement with a broad segment of society (Stiglitz 2002).

In sum, while market-creating institutions may be a strong determinant of the growth prospects of a given nation and explain inequality between nations, the distribution of qualifications, access to education, and stocks of human capital will largely determine the equity of the distribution of incomes within nations. Participation is key to defining the path institutions take and identifying socio-economic changes that may produce social disequilibrium. Identifying where the labour supply and demand exists, as well as where jobs will be created and destroyed should inform investment in human capital, allowing society to return to equilibrium. As Piazza-Georgi (2002, p. 465) observes, it is the quality rather than the quantity that matters when it comes to investment in skills and education; policy must be tailored to technological changes and innovations (Cingano 2014, p. 6).

Most importantly, the beneficial outcomes of good policies will be magnified in states that respect the rule of law, where there is predictability in rule making, institutionalized checks and balances, and freedom from corruption (Chhibber 1999). However, as mentioned, the rule of law is insufficient, in and of itself, to promote broader economic and political engagement. Building a credible government begins with listening and partnership (Chhibber 1999, p. 308). The rule of law needs to be supported by participatory institutions if a strategic state is to satisfy (a) the evolving demands of economic actors and (b) produce the credible commitment demanded by the rule of law and in a market economy. In essence, there are two pillars to our market-engaging institutions—inclusive human capital formation and political participation—which rest on a strong rule of law foundation.

4 Market-Engaging Institutions in Motion: Ireland’s Development Model

We now turn to consider whether market-engaging institutions are feasible in practice and capable of promoting inclusive economic growth. We take Ireland as a case study and find that public investment in human capital formation was key to attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) and opening up Ireland’s economy. Additionally, Ireland was able to protect labour interests in the process of trade integration through a series of Social Partnership Programmes. These agreements further ensured consistency in economic policy across governments, avoided regulatory inertia and reduced the opportunity for capture. We further find evidence that the dismantling of Ireland’s market-engaging institutions after the 2007–2008 financial crisis corresponds with a decline in the labour share of income and a rise in inequality.

4.1 Human Capital and Social Partnership at the Heart of Ireland’s Success

In less than a decade, the Economist (1988, 2017) went from crowning Ireland the “Poorest of the Rich” to “Europe’s Shining Light.” Speaking about Poland’s growth prospects, the World Bank (2015) recently observed that “becoming a fully developed economy will be a challenge: only a few countries in the past have succeeded in doing so, including Japan, Singapore, Taiwan, South Korean, and Ireland.” The World Bank’s comment recognises the (seemingly) extraordinary success of Ireland’s economic development. However, what the East Asian and Celtic Tigers have in common is that their development models were state-led rather than market-led and were characterised by early and significant investments in public goods, services, and human capital (Stiglitz 2021). In short, Ireland’s success was predicated on the early formation of market-engaging institutions. In Ireland’s case, the state worked in partnership with economic actors (both labour and capital representatives) to develop long-term and consistent economic policies.Footnote 1

Ireland’s growth has indeed been exceptional. However, this was not always the case. After independence in 1922 Ireland’s economic policy was one of austerity and isolationism. Yet, Ireland was able to change its fortunes by increasing public expenditure, investing in human capital, and gradually entering the global market (Dorgan 2006; Fitzgerald 1999). Ireland began developing its education system in the late 1960s, with free secondary education introduced in 1967 (Fitzgerald 1999, p. 12). Dorgan (2006, p. 3) finds that public expenditure grew by nearly 10 percent between 1960 and 1973. It was only once “the government and the social partners increasingly came to view investment in human capital as a strategic objective in the national development planning process and as an important tool for growth,” (World Bank 2012) that Ireland was equipped to enter the free-market and its well-known growth phase. As Ó’Riain (2000, p. 159) explains, by investing locally in learning, efficiency, and innovation, and integrating local alliances into global supply chains “[l]ocal strength becomes the basis of global competitiveness.” This allowed Ireland to “leapfrog over the immediate hump of industrialisation” to become a post-industrial high-tech economy (Murphy 2000, p. 4).

The Irish State further benefitted from EU funding following its membership in 1973. While Ireland’s tiger phase occurred during the onset of neoliberalism (i.e., market oriented reforms aimed at deregulating capital markets, privatizing social services, and lowering trade barriers), the more likely reason for Ireland’s economic growth at this time was the growth in the transfer of EU Structural Funds which allowed it to continue investing in infrastructure and education (Fitzgerald 1999, p. 10). However, the way in which these funds were managed and distributed was equally important. Dorgan observes that similar levels of EU funds were transferred to Greece, Portugal, and Spain, yet none of these countries have managed to capitalize on this investment (Dorgan 2006, p. 8).

A series of articles published by the Financial Times highlighted that the ability for European Union Structural Funds (ESF) to promote growth depends on (a) state capacity to administer the funds, and (b) the opportunity for corrupt practices to diminish funds either at the national or EU. O’Murchu and Pignal (2010) commented that “a programme, which has been credited for lifting once-under-developed countries like Ireland and Spain into gleaming modernity, now spends billions of euros every year on projects that appear no longer to live up to the programme’s mission: transforming the poorer parts of the Union through infrastructure, education and development investment into sustainably prosperous communities.” Pignal (2010) found that ESFs only achieve this mission where local and national authorities have the capacity to direct those funds to the intended beneficiaries, in particular small and medium businesses.

Therefore, it may not be possible to attribute Ireland’s economic success solely to an injection of EU funding. As Desai et al (2020) note, institutional design and implementation is equally important when it comes to the administration of funds. Countries have to overcome unresolved governance deficits, identify the proper beneficiaries, and have the infrastructure to administer and monitor the use of funds (Desai et al 2020). In short, the outcome of ESFs depends on the presence of the necessary human and organisational resources required for the administrative machinery of the state to “function effectively and efficiently in its role as a bridge between public policy objectives and their actual realisation” (Lutringer 2022, p. 21).

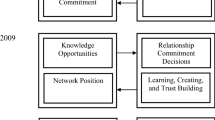

Therefore, Ireland’s success arises from a multitude of factors: investment in education, pragmatic and consistent economic policies, and more importantly maintaining a national consensus by building inclusive and accountable processes into the reform agenda. Dorgan (2006) and Ó’Riain (2000), in separate studies, consider that Ireland’s transformation was made possible by state’s responsiveness to a multiplicity of interests. This cooperative approach allowed a shared vision of Ireland’s economic policy which was sustained through public will. These investments were supported by an open, inclusive, and transparent system of oversight, with government funding allocated on the basis of explicit criteria, and stakeholder engagement in formulation and implementation of policy (World Bank 2012). Crucially, there was consistency in policy across levels of governments, meaning that there was strong coordination and cooperation in the delivery of services across government levels (see Fig. 1). In sum, Ireland has supported FDI, and economic globalisation by embedding reforms within a set of market-engaging institutions.

Source: OECD. Poland: Implementing Strategic-State Capability. OECD Public Governance Reviews. OECD 2013. 57 https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201811-en

Consistency in responsibilities across levels of government.

In particular Ireland used Social Partnership Programmes to negotiate wage restraints, public spending limits, and increase social inclusion (Ó’Riain 2000, p. 158). Between 1987 and 2008 there were six such Social Partnership agreements, each of which were the result of dialogue between employers and employees on the future of the Irish economy (Flaherty and Ó’Riain 2020, p. 1047). Consistency in economic policy when combined with Social Partnership Programmes further reduced the risk of regulatory inertia and state capture, meaning that the beneficial outcomes of public spending and EU funding were more evenly distributed. It is this combination of flexibility and consistency, and the careful balancing of global and local interests that has allowed Ireland to withstand shocks and continue on a strong development path.

The Irish approach was quite different to that adopted in the UK at the time, or later followed by transitional economies. As Fitzgerald (1999) explains, the UK pursued a legalistic approach, whereas Ireland was inspired by the partnership approach taken in Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark. A partnership approach involved “regular negotiations between the social partners which have resulted in a series of agreements covering not only pay rates, but also taxation policy and policy on publicly provided services” (Fitzgerald 1999, p. 9). Departing from a legalistic approach, and including stakeholder engagement added legitimacy to reform programs, making reforms more acceptable and durable.

In short, and contrary to popular belief, it was the commitment to market-engaging institutions that was the basis of Ireland’s economic success. Ireland adopted a gradualist approach and its success appears to be the result of a commitment across successive governments to pursue a consistent economic strategy (Fitzgerald 1999, p. 2). As Fitzgerald (1999, p. 29) notes, “such a strategic approach to economic policy mirrors that of some Asian countries in more recent times, and it highlights the importance of creating an environment of certainty for foreign investors.” Like the Asian tigers, Ireland’s development path also began with a protectionist stance, early investment in human capital, followed by a gradual freeing of trade, at first between the UK under the Anglo-Irish Free Trade Agreement (1965) and then upon entry to the European Union. Essentially, the Irish experience shows that three things matter for long-run growth—growth-friendly spending, stakeholder engagement in economic policy, and consistency in economic policy.

While market-creating, market-regulating, and market-stabilizing institutions were all key to forming a robust market economy, and while market-legitimizing institutions certainly helped offset the negative externalities of a capitalist market, we suggest that Ireland’s development path illustrates the importance of market engaging institutions for equitable and inclusive development. It is not sufficient to tackle inequality through progressive taxation and transfers, rather there needs to be a bundle of institutions that mediate the interests of labour and capital, respond flexible to the demands of market actors and the emergence of new markets and technologies, but that are supported by strong rule of law. Unfortunately, Ireland’s development strategy changed after the financial crisis, when Ireland began dismantling its market-engaging institutions and made a turn towards neoliberalism.

4.2 The Neoliberal Turn: The Dismantling of Ireland’s Market-Engaging Institutions

The financial crisis resulted from a failure of market regulating and stabilizing institutions, rather than market-engaging institutions. Yet, the latter were flagged for demolition in the post-crisis recovery program. The Social Partnership Programmes collapsed after negotiations broke down during the financial crisis (O’Kelly 2010). The government also shifted from a consensual approach on socio-economic policy to a unilateral approach (Regan 2009). This shift was largely influenced by external forces, particularly the European Monetary Union and the Troika (the European Commission, European Central Bank, and IMF). As Regan (2009, p. 1) explains, “the policy constraints of European Monetary Union (EMU) and the narrow focus on public sector austerity, in the context of an unprecedented economic crisis, has undermined the capacity of actors to engage in a strategy of social partnership,” and further entrenched neoliberalism in Irish economic policy. This is despite the fact that the “causal factor behind [the financial crisis] was a house-price boom associated with an oversupply of cheap credit and facilitated by pro-cyclical fiscal policies, not social partnership” (Regan 2009, p. 16).

The shift towards neoliberalism has had a notable impact on income inequality. Ireland’s Gini coefficient has stayed relatively stable since 2000 after a period of rapid decline from 1987 to 2000. Indeed, Ireland’s Gini coefficient was at a record low in 2019. However, the stability of Ireland’s disposable income inequality is largely due to the intervention of progressive taxation. This disguises inequalities in market income growth, where growth has been less evenly distributed (Roantree et al. 2021). On the other hand, earnings have stagnated, and young people entering the labour market are earning less than their counterparts in the 1990s and 2000s (Roantree et al. 2021). Despite the interventions of market-legitimizing institutions, Ireland currently has the highest gross income inequality of any other EU country. Ireland is now known for its low wages, uneven labour participation, particularly amongst women, and increasing numbers at risk of poverty (Sweeney and Wilson 2018).

Carolan (2019, p. 3) observes that “between 2015 and 2017 the bottom 50% of people experienced a 2% fall in their share of gross income, while the top 1% saw their share increase by 27%. Between 2010 and 2015 average household expenditure among the bottom 40% rose by 3.3%, while incomes rose by barely 1.1%.” This corresponds with a gradual decrease in government spending, and public expenditure on education since the early 1980s. In 1981, government expenditure in Ireland was 60.7 percent of GDP, while spending on education was 5.73 percent of GDP (Ortiz-Ospina and Roser 2016a, b). McDonnell and Goldrick-Kelly (2018) compared per capita public expenditure in Ireland between 2008–2012 with that of its peers and found that on average Ireland was spending just 84.7 percent of the peer country population. From Table 1 below, we can see that public spending has dropped significantly.

We may see deepening inequality in Ireland in both income and education as responsibilities for education are shifted to private actors. There will likely come a time when tax transfers are insufficient to tackle income inequality. Furthermore, relying on progressive taxation rather than progressive education and economic policies will create a pool of untapped human potential. This will impact Ireland’s potential to attract high-skilled and high earning jobs which in turn will impact Ireland’s ability to raise revenue. On a more human level, cutting off education to the economically marginalized limits their capacity to pursue the lives they want as envisaged in Sen’s human-centric approach to development (Sen 2005). As mentioned above, there appears to be a two-way relationship between education and income inequality. Access to high-skilled and high-income jobs require education, and if we make education contingent on existing wealth, we exclude lower-income individuals from more lucrative markets and force them to the peripheries. As Andersen explains “equality of opportunity concerns both the formal access and entry possibilities into the educational system as well as the outcomes” (Andersen 2015, p. 20). Similarly, Björklund and Jäntti (2009) have found that those countries with higher income inequality have lower social mobility.

Trade union density has also declined in Ireland. While trade union density has stayed steady in the Nordic countries and Belgium, it has dropped significantly in Ireland, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, and Austria (see Fig. 2 below). However, the Netherlands and Austria have maintained high levels of collective bargaining coverage, with Austria rising from 95 to 98 percent of employees from 1960 to 2015 and the Netherlands dropping only slightly from 80.8 percent to 79.4 percent in the same period. Ireland and the UK on the other hand have dropped from around 70 percent collective bargaining coverage to below 40 percent, with the UK sitting on 27.9 percent in 2015. The sharp decline of trade union density and collective bargaining coverage in the United Kingdom, unsurprisingly, corresponds with the onset of neoliberalism. Once again, those countries that top the tables in social partnership are those that have high expenditure and low inequality. Of course, these findings do not definitively evidence a causal relationship between market-engaging institutions and inequality However, our findings strongly suggest a correlation between market-engaging institutions and lower inequality. Of particular interest is that the reduction in trade union density and the removal of Social Partnership Programmes may explain the abovementioned finding that growth in market incomes has been unevenly distributed.

Source: Authors’ own, data from Trade Union Dataset, OECD, https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=TUD#

Trade union density in selected EU countries 1960–2015.

While the post-recession dismantling of Ireland’s market-engaging institutions is concerning there have been some promising recent initiatives. For instance, Ireland’s National Skills Strategy (Department of Education and Skills 2016) aims to invest in the skills required for current and future participation in the workforce through active engagement with key stakeholders. The Digital Innovation Programme (Department of Rural and Community Development 2021) provides funding to Local Authority-led projects that improve regional digital development, while the Human Capital Initiative focuses on “increasing capacity in higher education in skills-focused programmes designed to meet priority skills needs” (Higher Education Authority n.d). Therefore, while Ireland’s market-engaging institutions were eroded, they have not been abolished. There is still substantial scope for improvement. In particular, there needs to be greater investment in more robust social partnerships that can meet the needs of contemporary workers.

5 Conclusion and Future Research

While creativity, innovation, and technological change are products of a market economy, destruction and disruption are misnomers that lead us to believe (and too readily accept) that inequality is the price of progress. Rather, we have illustrated that inclusive growth may be realizable through early and continued investment in market-engaging institutions.

This article examined the institutional conditions required to support a strategic state in being responsive to the changing demands of a market-economy, whilst maintaining a credible commitment to long-term policy goals. We noted that at times these two priorities may conflict. In response, we suggested that a bundle of institutions was needed to balance the competing priorities of flexibility and stability that underpin a strategic state. We observed that the rule of law provides the conditions for the state’s credible commitment. On the other hand, we identified that institutions that support human capital formation and political participation for a broader segment of society were key to ensuring that the state remained responsive to the needs of both labour and capital in a dynamic market economy. Together, we termed these institutions market-engaging institutions. While the rule of law may support these institutions, we suggested that it is insufficient, in and of itself, to tackle growing inequality in advanced market economies. Instead, we argued that market-engaging institutions and the rule of law are interdependent aspects of a human-centric state. Together they provide the conditions for the state to adapt to the changing needs of market actors in an inclusive manner, whilst maintaining the requisite stability required to support an exchange-based economy.

These findings warrant further theoretical and empirical inquiry into the dynamics of market-engaging institutions. We would encourage future research into the connection between market-engaging institutions and social capital formation. It may be hypothesised that market engaging institutions and the rule of law act as a formalised complement to informal networks that support cooperative action (Farrington 2022). Therefore, it may be interesting to consider how social capital is complementary to or captured by our understanding of market-engaging institutions. Future research could also consider the form market-engaging institutions might take in authoritarian regimes, socialist economies, or lower- and middle-income countries such as China. There is evidence that China is moving towards greater formalisation (Chen et al. 2017; Ramanujam et al. 2019), and greater investment in education, and training (Mehrotra et al. 2015) as its economy grows. Finally, future empirical research might conduct qualitative or quantitative country specific analyses or consider the role market-engaging institutions play in the development of lower- and middle-income countries.

Notes

More recently, the World Bank (2021) has acknowledged the vital role human capital investment and social partnership played in Ireland’s economic and social transformation.

References

Acemoglu D (2003) Root causes—a historical approach to assessing the role of institutions in economic development. Finance Dev 40:27–30

Acemoglu D, Robinson JA (2013) Economics versus politics: pitfalls of policy advice. NBER Working Paper Series 18921, National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w18921/w18921.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2022

Acemoglu D, Johnson S, Robinson JA (2001) The colonial origins of comparative development: an empirical investigation. Am Econ Rev 91:1369–1401

Acemoglu D, Gallego FA, Robinson JA (2014) Institutions human capital and development. NBER Working Paper Series 19933, National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w19933/w19933.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2022

Aghion P, Akcigit U, Deaton A et al (2016) creative destruction and subjective well-being. Am Econ Rev 106:3869–3897

Allmann K, Blank G, Wong A (2021) Libraries on the front lines of the digital divide: the Oxfordshire Digital Inclusion Project Report. University of Oxford, Oxfordshire. https://www.law.ox.ac.uk/sites/files/oxlaw/digital_inc_project_report_a4_final.pdf. Accessed 4 Dec 2021

Andersen TM (2015) Human capital, inequality and growth. Discussion Paper 007, European Commission, Luxembourg. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/dp007_en.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2021

Atkinson AB (2015) Inequality: what can be done? Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Baldaci E (2004) Social spending, human capital, and growth in developing countries: implications for achieving the MDGs. Working Paper WP/04/217, International Monetary Fund

Banerjee AV, Duflo E (2003) Inequality and growth: what can the data say? J Econ Growth 8:267–299

Barro RJ (2000) Inequality and growth in a panel of countries. J Econ Growth 5:5–32

Belitz H, Junker S, Podstawski M, Schiersch A (2015) Growth through research and development. DIW Econ Bull 35:455–468

Bennett MJ (2011) Hart and Raz on the non-instrumental moral value of the rule of law: a reconsideration. Law Philos 30:603–635

Berger T (2016) Creative destruction and the changing geography of European jobs. Oxford Martin School. https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/blog/creative-destruction-and-the-changing-geography-of-european-jobs/. Accessed 15 May 2022

Björklund A, Jäntti M (2009) Intergenerational income mobility and the role of family background. In: Nolan B, Salverda W, Smeeding TM (eds) Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Carolan D (2019) Inequalities in Ireland. SDG Watch Europe, Ireland. https://www.sdgwatcheurope.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/7.3.a-Report-IE.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2022

Castelló A, Doménech R (2002) Human capital inequality and economic growth: some new evidence. Econ J 112:187–200

Chen D et al (2017) Law, trust and institutional change in China: evidence from qualitative fieldwork. J Corp Law Stud 17(2):257–290

Chhibber A (1999) Social capital, the state, and development. In: Serageldin I, Dasgupta P (eds) Social capital: a multifaceted perspective. World Bank, Washington DC, pp 296–309

Cingano F (2014) Trends in income inequality and its impact on economic growth. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Paper No. 163. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/5jxrjncwxv6j-en. Accessed 2 Feb 2022

Department of Education and Skills (2016) Ireland’s National Skills Strategy 2025. Government of Ireland. https://assets.gov.ie/24412/0f5f058feec641bbb92d34a0a8e3daff.pdf. Accessed 4 Oct 2021

Department of Rural and Community Development (2021) Digital Innovation Programme. Government of Ireland. Accessed 5 Oct 2021

Desai D et al (2020) Redefining vulnerability and state-society relationships during the COVID-19 crisis: the politics of social welfare funds in India and Italy. In: Poiares Maduro M, Kahn PW (eds) Democracy in times of pandemic: different futures imagined. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 182–195

Dorgan S (2006) How Ireland became the Celtic Tiger. https://www.heritage.org/europe/report/how-ireland-became-the-celtic-tiger. Accessed 5 Oct 2021

Drumaux A, Joyce P (2018) The strategic state and public governance in European institutions. In: Drumaux A, Joyce P (eds) Strategic management for public governance in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54764-4_1

Edgardo Campos J, Lien D, Pradhan S (1999) The impact of corruption on investment: predictability matters. World Dev 27:1059–1067. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00040-6

Elliott IC (2020) The implementation of a strategic state in a small country setting—the case of the ‘Scottish Approach. Public Money Manag 40:285–293

Farrington F (2022) Trust and the rule of law: an interdisciplinary analysis of the relationship between the rule of law and economic development. Doctoral Thesis, University of Cambridge

Fitzgerald J (1999) Understanding Ireland’s economic success. ESRI Working Paper No. 111, Economic and Social Research Institute, Dublin

Flaherty E, Ó’Riain S (2020) Labour’s declining share of national income in Ireland and Denmark: the national specificities of structural change. Soc Econ Rev 18:1039–1064

Frenken K, Schor J (2019) Putting the sharing economy into perspective. In: Mont O (ed) A research agenda for sustainable consumption governance. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Fritz V (2021) Institutions are in flux. That’s both a challenge and an opportunity. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/governance/institutions-are-flux-thats-both-challenge-and-opportunity. Accessed 11 Feb 2023

Fuller L (1969) The morality of law. Yale University Press, New Haven

Galor O, Tsiddon D (1997) The distribution of human capital and economic growth. J Econ Growth 2:93–124

Glomm G, Ravikumar B (1992) Public versus private investment in human capital: endogenous growth and income inequality. J Polit Econ 100:818–834

Goldin C (2016) Human capital. In: Diebolt C, Haupert M (eds) Handbook of cliometrics. Springer, Berlin. https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/34309590

Greif C (1993) Contract enforceability and economic institutions in early trade: the Maghribi traders’ coalition. Am Econ Rev 83:525–548

Helmke G, Levitsky J (2004) Informal institutions and comparative politics: a research agenda. Perspect Polit 2:725–740

Higher Education Authority (n.d.) Human capital initiative. In: Higher Education Authority. https://hea.ie/skills-engagement/human-capital-initiative/. Accessed 5 Oct 2021

Hongdao Q et al (2018) Corruption prevention and economic growth: a mediating effect of rule of law. Int J Soc Sci Stud 6:128–143. https://doi.org/10.11114/ijsss.v6i2.2946

International Labour Organisation (2021) COVID-19 and the World of Work Seventh Edition. ILO Monitor. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_767028.pdf. Accessed 6 July 2022

Irvine G (2008) The rise of inequality in Britain and the United States. Polity Press, Cornwall

Isham J, Narayan D, Pritchett L (1995) Does participation improve performance? Establishing causality with subjective data. World Bank Econ Rev 9:175–200

Kaufmann D, Kraay A, Zoido-Lobaton P (1999) Governance matters. Policy Research Working Paper, Working Paper Series. World Bank, Washington DC

Kramer MH (2004) On the moral status of the rule of law. Camb Law J 63:65–97

Lee JW, Lee H (2018) Human capital and income inequality. Working Paper 810, Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo

Lutringer C (2022) The puzzle of ‘unspent’ funds in Italy’s European Social Fund. Int Dev Policy 14:1

Mazzucato M (2018) The entrepreneurial state: debunking the public vs private sector myths. Penguin Books, London

McDonnell TA, Goldrick-Kelly P (2018) A growth-friendly spending mix? Breaking down public spending in Ireland. J Self-Gov Manag Econ 6:7–34

McGaughey E (2016) All in ‘it’ together: worker wages without worker vote. King's Law J 27:1–9. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2729150

Mehrotra S, Gandhi A, Kamaladevi A (2015) China’s skill development system: lessons for India. Econ Pol Wkly 50:57–65

Murphy AE (2000) The ‘Celtic Tiger’—an analysis of Ireland’s economic growth performance. https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/1656/00_16.pdf. Accessed 12 Dec 2022

North DC (1990) Institutions, institutional change and economic performance. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

O’Kelly KP (2010) The end of social partnership in Ireland? Transfer Eur Rev Labour Res 16:425–429

O’Murchu C, Pignal S (2010) Europe’s grand vision loses focus. https://www.ft.com/content/ddffb8f8-fbe8-11df-b7e9-00144feab49a. Accessed 21 Jan 2023

Ó’Riain S (2000) The flexible developmental state: globalization, information technology and the “Celtic Tiger.” Polit Soc 28:157–193

OECD (2013) Poland: implementing strategic-state capability. OECD Public Gov Rev. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264201811-en

OECD (2018) How does access to early childhood education services affect the participation of women in the labour market? Education Indicators in Focus No. 59. https://doi.org/10.1787/232211ca-en

OECD (2020a) Caregiving in crisis: gender inequality in paid and unpaid work during COVID-19. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/3555d164-en. Accessed 14 Jan 2022

OECD (2020b) The Impact of COVID-19 on student equity and inclusion: supporting vulnerable students during school closures and school re-openings. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/d593b5c8-en. Accessed 14 Jan 2022

OECD (2020c) What is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on immigrants and their children? https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/e7cbb7de-en. Accessed 14 Jan 2022

OECD and European Commission (2021) Female-led businesses were more likely to close during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/component/7457f6de-en. Accessed 14 Jan 2022

Ortiz-Ospina E, Roser M (2016a) Government spending. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/historical-gov-spending-gdp?tab=chart&country=~IRL. Accessed 1 Aug 2022

Ortiz-Ospina E, Roser M (2016b) Global education. https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/total-government-expenditure-on-education-gdp?country=~IRL. Accessed 1 Aug 2022

Palma JG (2011) Homogeneous middles vs heterogeneous tails, and the end of the “Inverted-U”: the share of the rich is what it’s all about. Dev Change 42:87–153

Piazza-Georgi B (2002) The role of human and social capital in growth: extending our understanding. Camb J Econ 26:461–479

Pignal S (2010) Poor take-up reflects basic flaw. https://www.ft.com/content/f275a632-fbe1-11df-b7e9-00144feab49a. Accessed 21 Jan 2023

Piketty T (2017) Capital in the 21st century. Belknap Press, Cambridge

Polanyi K (2001) The great transformation: the political and economic origins of our time. Beacon Press, Boston

Ramanujam N, Farrington F (2022) The rule of law, governance and development. In: Hout W, Hutchison J (eds) Handbook on Governance and Development. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham

Ramanujam N, Caivano N, Agnello A (2019) Distributive justice and the sustainable development goals: delivering agenda 2030 in India. Law Dev Rev 12:495–536

Raz J (2009) The Authority of Law. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Regan A (2009) The impact of the Eurozone crisis on Irish social partnership: a political economic analysis. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---europe/---ro-geneva/---ilo-brussels/documents/genericdocument/wcms_195004.pdf. Accessed 3 Feb 2022

Roantree B et al (2021) Poverty, income inequality and living standards in Ireland. https://www.esri.ie/system/files/publications/BKMNEXT412_1_0.pdf. Accessed 2 Feb 2022

Rodrik D (2000a) Institutions for high-quality growth: what they are and how to acquire them. Studies in Comparative International Development 35

Rodrik D (2000b) Participatory politics, social cooperation, and economic stability. Am Econ Rev 90:140–144

Rodrik D, Subramanian A (2003) The primacy of institutions. Finance Dev 40:31–34

Saint-Paul G, Verdier T (1993) Education, democracy and growth. J Dev Econ 42:399–407

Schumpeter J (2010) Capitalism, socialism and democracy. Taylor & Francis Group

Sen A (2005) Human rights and capabilities. J Hum Dev 6:151–166

Shirley M (2008) Institutions and development. In: Menard C, Shirley M (eds) Handbook of New Institutional Economics. Springer, Berlin, pp 611–638

Shuey EA, Kankaraš M (2018) The power and promise of early learning. OECD Education Working Paper No. 186. https://doi.org/10.1787/f9b2e53f-en

Standing G (2017) Basic income: a guide for the open-minded. Yale University Press, New Haven

Stiglitz JE (2002) Participation and development: perspectives from the comprehensive development paradigm. Rev Dev Econ 6:163–182

Stiglitz JE (2014) Reforming taxation to promote growth and equity. Roosevelt Institute, New York. https://rooseveltinstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/RI_Reforming_Taxation_White_Paper_201405.pdf. Accessed 13 Dec 2021

Stiglitz JE (2019) People, power, and profits: progressive capitalism for an age of discontent. Allen Lane, London

Stiglitz JE (2021) The proper role of government in the market economy: the case of the post-COVID recovery. J Gov Econ 1

Sweeney R, Wilson R (2018) Cherishing all equally 2019: inequality in Europe and Ireland. TASC, Dublin

The Economist (1988) The Poorest of the Rich 306:7533

The Economist (1997) Ireland Shines 343:8017

Van Belle J (2016) Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) and its long-term effects on educational and labour market outcomes. Research Report RR-1667-EC, RAND Corporation. https://doi.org/10.7249/RR1667

World Bank (2006) Where is the wealth of nations? Measuring capital for the 21st Century. World Bank, Washington, DC

World Bank (2012) Ireland workforce development. SABER Multiyear Country Report No. 79926. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/27077. Accessed 3 Feb 2022

World Bank (2015) Toward an innovative poland: the entrepreneurial discovery process and business needs analysis. Ministry of Economic Development, Poland. http://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/672481468191359439/pdf/106148-REPLACEMENT-v1-EXCSUM-ENGLISHWeb.pdf. Accesed 3 Feb 2022

World Bank (2021) Building human capital: lessons from country experiences—Ireland. World Bank, Washington DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36301. Accessed 12 Jan 2022

Yifu Lin J, Nugent JB (1995) Institutions and economic development. In: Chenery H, Srinivasan TN (eds) Handbook of Development Economics, 1st edn, vol 1. Elsevier, North Holland, Amsterdam

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the editorial team and the two anonymous reviewers for their detailed and insightful suggestions. Thanks is also due to the research assistants who contributed to preparing this work for publication - Katrina Bland, Mehlka Mustansir, Kassandra Neranjan and Nicolas Kamran. Finally, we wish to acknowledge the Faculty of Law, McGill University who supported this research through the Randall Barker, Ratpan, and VP research funds.

Funding

Dr. Ratpan Endowment Fund at the Faculty of Law, McGill University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ramanujam, N., Farrington, F. Market-Engaging Institutions: The Rule of Law, Resilience and Responsiveness in an Era of Institutional Flux. Hague J Rule Law 15, 329–352 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40803-023-00190-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40803-023-00190-4