Abstract

Can international organizations (IOs) influence attitudes about regulating “Big Tech?” Recent tech sector activity engenders multiple concerns, including the appropriate use of user data and monopolistic business practices. IOs have entered the debate, advocating for increased regulations to protect digital privacy and often framing the issue as a threat to fundamental human rights. Does this advocacy matter? We hypothesize individuals that score high on measures of internationalism will respond positively to calls for increased regulation that come from IOs and INGOs. We further predict Liberals and Democrats will be more receptive to IO and NGO messaging, especially when it emphasizes human rights, while Conservatives and Republicans will be more receptive to messaging from domestic institutions that emphasize antitrust actions. To assess these arguments, we fielded a nationally-representative survey experiment in the U.S. in July 2021 that varied the source and framing of a message about the dangers posed by tech firms, then asked respondents about support for increased regulation. The average treatment effect of international sources is largest for respondents who score high on an index of internationalism and for respondents on the left of the political spectrum. Contrary to expectations, we found few significant differences across human rights and anti-trust framings. Our results suggest the ability of IOs to influence attitudes about tech regulation may be limited in an era of polarization, but that individuals who value multilateralism may still be influenced by IO campaigns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Over the past 30 years, tech companies have come to dominate commerce both within and across borders, while policymakers have debated new rules regulating tech firm activities. Questions about market competitiveness and privacy rights are central to ongoing debates about tech regulation. Amidst this backdrop, international organizations (IOs), such as the European Union (EU) and United Nations (UN), have entered the debate by advocating new standards and disseminating “best practices” with respect to digital privacy and users' rights. Similarly, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), like the London-based Privacy International, have emerged to spread information and persuade minds about the need to regulate powerful tech firms. Yet we know very little about whether these advocacy campaigns, meant to influence ideas about responsible corporate behavior, matter. Can IOs and NGOs influence attitudes about regulating "big tech"?

Countries vary widely in their regulatory approaches. The U.S. has been slow to enact comprehensive regulations, though several recent initiatives, such as the Federal Trade Commission's (FTC) 2020 antitrust suit against Facebook and the multi-state antitrust suit against Google in 2021, suggest increased momentum for regulation. These events also follow decreasing favorability of the tech sector among the general public, both on the left and right. For instance, an April 2021 Pew Research poll found that 68% of Americans believe tech firms have too much power and 56% favor more regulation, while only 47% preferred more regulation in June 2020.Footnote 1 A February Gallup poll found negative views of tech firms increased from 33% in August 2019 to 45% in February 2021.Footnote 2 Many on the left dislike breaches of privacy and the monetization of users' personal information, while those on the right often claim tech firms use their monopoly power to limit free speech. Though these segments of the public disagree on why tech firms should be subject to new regulations, the fact that they agree on the need for more regulation seems to have opened political space for attorneys general and government agencies to pursue more robust action.

In Europe, where citizens are perhaps more accustomed to private sector regulation, the EU has acted more aggressively.Footnote 3 The General Data Protection Regulation, which came into force in 2018, harmonized rules for data privacy and has since served as a model for data privacy laws. The EU is currently considering regulation that would increase platforms' responsibility for content, known as The Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act.

What explains the different speed and style of regulation between the EU and U.S.? One answer is that the European public is generally more receptive to regulation, and that only recently has the U.S. public come around to similar attitudes. Another reason can be found in the discourse surrounding the debate in the EU vs. the U.S. Whereas the debate in Europe has predominantly focused on data privacy and consumer rights, the debate in the U.S. tends to focus on the size of tech firms and anti-competitive nature of the sector. This difference motivates the first of two central questions: does issue framing affect willingness to increase tech regulations?

Beyond the EU, which has considerable independent regulatory power, other IOs and NGOs have become active advocates for privacy laws. For instance, the office of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights created a Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy in 2015, tasked with spreading information about data privacy and advocating for “best practices.” NGOs like Privacy International (originally founded in 1990) engage in a variety of activities to promote digital privacy. These actors tend to describe their mission in terms of protecting fundamental human rights, rather than focusing on the near-monopoly market share many large firms possess, although the issues are related. The decision to link data privacy to human rights is not random; these actors see the stakes of the debate as fundamental for human rights and believe this issue framing will help mobilize support for increased regulation. Yet especially in the U.S., where engagement with IOs has become heavily politicized, such campaigns may have limited appeal. These trends motivate the second central question of this paper: do IO and NGO campaigns influence public opinion about tech regulation?

We study individual attitudes because swings in public opinion are often the impetus for new public policy. As public opinion in the U.S. shifts in favor of more regulation, the urgency for Congress and regulatory bodies to act increases. We argue that IOs and NGOs can sway public opinion, but with limits. In particular, messaging from international sources like the UN or Privacy International is likely to be filtered through preexisting attitudes toward internationalism and multilateralism. This is especially likely in an environment, like the current U.S., where multilateralism and international cooperation is highly politicized (cf. Bowen & Broz, 2021). We posit that individuals who think the U.S. should be engaged in world affairs and cooperate with international institutions are more likely to be influenced by messages from international sources, while those who place low importance on internationalism will be more skeptical. We also argue that messaging about tech regulations will be filtered through partisan lenses. Individuals on the left may be more receptive to messaging from international sources, whereas individuals on the right will be more moved by messaging from domestic sources, likely due to the influence of elite cues about international institutions and multilateralism.Footnote 4

We further hypothesize that messages emphasizing human rights will prompt more emotional reactions, and hence will be more persuasive than messaging emphasizing the sector's lack of competitiveness. We also expect partisan differences with respect to message framing. Self-identified liberals and Democrats may be more receptive to rights-based arguments, while conservatives and Republicans may be more moved by appeals to market competition.

To test these claims we fielded a nationally representative survey experiment in the U.S. in July 2021 through YouGov.Footnote 5 We employed a 3 × 2 factorial design, in which respondents were randomly selected into reading a sample news story quoting one of three sources: the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy, Privacy International, and the Federal Trade Commission. Respondents were then randomized into seeing a story that emphasized a fundamental human right to privacy, citing the UN's International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, or a story emphasizing firm size and anti-competitiveness. We included a control group that read no story.

After exposure to these treatments, we asked respondents about their support for increasing regulations on tech firms. We also asked about the likelihood they would engage in several behaviors, such as researching platforms' privacy policies or discontinuing use if a platform's policies were not satisfactory. Our survey included a series of questions to gauge attitudes toward internationalism and political knowledge. These items allow us to look at the average treatment effect (ATE) across subgroups: high and low internationalism, left and right ideology, self-identified party ID, and high and low political knowledge.

Our findings indicate that IO and NGO messaging can influence attitudes, but primarily amongst respondents who score high on internationalism. Respondents that scored low on internationalism were more likely to be influenced by a story citing a domestic source, the FTC. To our surprise, we found little difference between respondents exposed to human rights and antitrust messaging. Below, we speculate on some reasons for this non-finding, including that media attention in the U.S. has highlighted ongoing antitrust actions rather than emphasizing privacy as a human right. This may illustrate how underlying political culture conditions efforts at persuasion and norm dissemination from IOs. In the U.S., where the right to privacy is implied but not explicitly stated in the Constitution, individuals may be less moved by appeals to rights. Yet as we discuss below, threats to privacy may threaten other rights, such as freedom of speech and assembly. As such, one implication of our study is that efforts to sway attitudes toward tech regulations in the U.S. might be more effective if they explicitly linked privacy to basic civil and political rights.

Our study makes several contributions. First, we know little about how influence campaigns matter in establishing widely shared expectations about appropriate digital privacy regulations, despite the efforts of IOs and NGOs in this relatively new issue area. Second, our study adds to a growing body of evidence showing that polarization is an obstacle to international cooperation (e.g. Bowen & Broz, 2021), extending to the international dissemination of ideas about best practices for regulating "Big Tech." Although partisans at opposite ends of the spectrum may support increased regulation, they often do so for different reasons, and attitudes are highly conditional on perceptions of the source of public information campaigns. Our study thus illustrates the possibilities, but also the limitations, of IOs' ability to disseminate norms.

1 IOs and public opinion

A large body of scholarship notes that not only do IOs often affect public attitudes, but this process plays an important role in determining whether states comply with international obligations (Dai, 2005). This literature examines the IO-public opinion nexus across a range of issue areas, such as the use of force (Chapman, 2012), trade policy (Chaudoin, 2014), human rights (Chaudoin, 2016; Wallace, 2013), and the environment (Greenhill, 2020), among others. Although some argue that the U.S. public is poorly informed about international affairs (see Holsti, 2004), the scholarship about IOs and public opinion has shown compelling evidence that IO activity can move mass attitudes, especially for salient issues.Footnote 6

Digital privacy impacts almost every citizen in the developed world, and increasingly many in the developing world. Why would messaging from an IO or NGO influence attitudes about how to best regulate this realm, especially if individuals are routinely exposed to information about privacy practices through user terms of agreement or news media? There are at least two arguments, drawn from the literature on IOs and public opinion, that apply.

First, IOs may be sources of expertise that help individuals forge beliefs about the appropriateness or efficacy of policies.Footnote 7 According to this argument, citizens may either have no opinion about policies they know little about, or alternatively possess some information and pre-existing attitudes about tech regulations and digital privacy. Additional messages from a source perceived as having special expertise can allow citizens to learn and adjust their attitudes. In formal models of information transmission, the degree to which updating occurs is a function of a “receiver's” knowledge about the motives of a "sender'' (cf. Farrell & Rabin, 1996). This means that in the context of IOs, citizens are likely to “consider the source” when evaluating messages from IOs and NGOs and are more likely to be receptive to calls for increased tech regulation when they believe those messengers share their own goals. Respondents predisposed to think IOs and NGOs promote the collective good, or who believe that an IO source shares similar preferences to them in a policy area, are more likely to update their beliefs in response to advocacy.

A second, and related, argument explains why IOs might be viewed as authorities on particular issue areas. They are often seen as repositories of scientific information or specialized expertise, which makes them particularly effective at disseminating norms (Finnemore 1996, Barnett & Finnemore, 1999, Barnett & Finnemore, 2005). This expertise lends them legitimacy, which may lead individuals to defer to IOs in many policy areas. As in information transmission theories, this perspective suggests that the degree to which IO messaging influences individuals is a function of how those individuals regard the IO.Footnote 8

Indeed, IOs routinely take steps to develop legitimacy in the eyes of observers by adopting standard operating procedures, technical terminology, and by emphasizing the professionalism of their bureaucracies (Barnett & Finnemore, 1999). IOs often develop internal knowledge, giving them some independence from member states (ibid; Abbot & Snidal 1998). NGOs develop and promote their expertise in similar ways. By focusing on specific issue areas, hosting conferences, disseminating research materials and policy briefs, and related activities, NGOs can establish their expertise in particular areas. Whether that expertise translates into deference to their recommendations or an ability to persuade depends on audiences' perceptions of the NGO. More so than IOs, NGOs often have a clear programmatic bias, which can dissuade some observers from consuming NGO messages. In particular, when an NGO is formed around an issue area that, ex ante, is associated with a partisan view, its messages are less likely to resonate with those that hold the opposite partisan view.

More generally, the activity of IOs and NGOs in the area of digital privacy is an example of norm entrepreneurship. Technological advancements that allow platforms and tech companies to gather user information have developed at breakneck speed. In response, new actors are emerging to advocate for best practices, and old actors are developing the know-how and organizational capacity to disseminate ideas about protecting privacy rights. Their efforts include, but are not limited to, providing information about the dangers of inadequate digital privacy laws, highlighting state obligations to human rights under relevant treaties, spreading information about new regulatory policies adopted by early movers in the realm of digital privacy, and contacting elected officials to increase pressure for regulation to protect users' rights.

This advocacy has multiple intended audiences. Some efforts are aimed at state governments, while others are aimed at tech companies themselves. However, the pressure on both the aforementioned actors to implement safeguards for digital privacy mounts when the public gains more awareness of the issue area. As such, much advocacy is aimed broadly at the public in order to alert users about how their information is used and to make the issue more salient in the minds of the public. As the President of Privacy International conveyed in an interview, sometimes "You have to stoke the fires of unrest, so that that boring regulatory machine can occasionally say it is responding to the public need….and when you have that unrest, you have vast amounts of media publications around it."Footnote 9 In other words, transnational advocacy efforts often involve attempts to sway public sentiment, which in turn puts pressure on regulators to respond to popular pressure.

These norm entrepreneurs are primarily operating in the “norm emergence” stage of the “norm life cycle” (Finnemore & Sikkink, 1998, 895–898). The United Nations system can be an important platform for norm entrepreneurs, as it provides visibility, resources, and a general air of authority. NGOs can accomplish the same thing through building their platforms and establishing networks of like-minded non-state actors (ibid, 900). The effectiveness of these efforts depends audiences' receptivity, however. This receptivity may change over time as more and more actors subscribe to the new norms. But early in the norm life cycle, contestation from those who are less receptive is to be expected.

In the survey experiment we describe below we test the implications of these arguments. The experiment varies source and framing of messages about the problems posed by large tech firms influences attitudes toward increasing regulation. We also designed our survey to allow comparison across partisan groups and preexisting attitudes toward internationalism. Before we turn to the design of our survey instrument and results, we first survey some descriptive evidence on attitudes toward digital privacy and tech regulations amongst the U.S. public and lay out our specific hypotheses.

2 Public Attitudes and Digital Privacy

IOs and NGOs have few tools at their disposal to compel states to enact stricter rules for tech firms. Instead, they rely largely on persuasion. Persuasion may be aimed directly at government officials, but as noted above, it is often aimed at the broader public. The latter may be more effective over the long run, especially in democracies where elected leaders are accountable to voters. Put simply, public opinion is often a good predictor of policy change.

Regulatory governance often resembles a game of “cat and mouse.” Firms prefer to adopt practices that stave off would-be regulators rather than become the target of new and burdensome regulations. This means in many cases, we should observe firms preemptively adopting practices in order to stay ahead of new regulatory initiatives (Solomon, 2010). And firms routinely commit to social responsibility initiatives, aimed at improving their public image in order to slow the pressure for regulation. However, when public opinion begins to coalesce around policy issues and regulatory initiatives (especially when the process is rapid), we observe considerable momentum for policy change (Wlezien, 1995; Soroka & Wleizien 2010; Stimson, 2015).

The debate over digital privacy and tech regulation has emerged as a central issue in not only the U.S. but across the world (Farrell & Newman, 2019). One strand of this debate emphasizes the threat to basic privacy that results from firms' use of user information. Another strand focuses on whether the tech sector is a level playing field, or whether the largest firms like Google, Facebook, and Amazon have crowded out competition by engaging in anti-competitive (and potentially illegal) practices. The two issues are related, even if they are often discussed separately in the media. When consumers face fewer choices, firms are less responsive to their preferences. And the collection of user information fuels both revenue and expansion into new corners of the sector, which can transform these one-time startups into sprawling, mega-firms capable of tracking consumers across multiple platforms.

The problem is also framed in different ways by different authorities on the subject. The UN High Commission for Human Rights and its office of the Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy, frame the issue as a threat to fundamental human rights. For instance, the opening page of the website of the Office of the High Commission for Human Rights (OHCHR) in the Digital Age states “data-intensive technologies, such as artificial intelligence applications, contribute to creating a digital environment in which both states and business enterprises are increasingly able to track, analyze, predict and even manipulate people’s behavior to an unprecedented degree. These technological developments carry very significant risks for human dignity, autonomy and privacy and the exercise of human rights in general, if applied without effective safeguards.”Footnote 10 The OHCHR's 2020 report invokes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child when establishing which rights are threatened by information technology.Footnote 11 These arguments highlight the most threatening aspects of large tech firms for democracy and inalienable rights and are most likely to influence individuals who identify strongly with the principles laid out in the ICCPR and other human rights treaties.

This contrasts with the discourse on the anti-competitive nature of the sector. Government activity in the U.S. has focused on antitrust actions, which may resonate more in a system premised on fair competition.Footnote 12 As inequality widens in the U.S., citizens' concerns may result in increased regulation for large, lucrative tech firms.Footnote 13 There is some evidence this is already occurring. In December 2020, 46 states joined the FTC in suing Facebook over anti-competitive practices. A federal court rejected the suit on the grounds of insufficient factual evidence late in June 2021, and the FTC amended the suit in August 2021. In October 2020, the Justice department sued Google under antitrust law, and 38 states filed a similar lawsuit against Google in July 2021. Texas, far from a hotbed of government regulation, filed its own lawsuit against Google in May 2021. And the FTC and Justice Department have ongoing investigations into Amazon and other tech “giants”.

Opinion polling supports the notion that attitudes are moving in support of increased regulation across party lines. An April 2021 Pew poll found that 56% of respondents think tech companies should be more regulated, up from 47% in June 2020. A February 2021 Gallup poll identified a similar trend, with the percent of respondents who think the government should increase tech regulation to 57%, up from 48% in August 2019.Footnote 14 An April 2021 poll by Morning Consult found even greater, and bipartisan, support for reining in tech firms, with 83% of voters saying legislation to protect user privacy should be a top'' or ''important but lower'' priority for Congress. 86% of Democrats and 81% of Republicans agreed with prioritizing privacy-protecting legislation.Footnote 15

The trends show mounting support for government action and a decline in the public's trust of tech firms. Nevertheless, the two sides of the debate may resonate differently across individuals, depending on their pre-existing attitudes. This may be especially true for a salient issue area, like problems posed by nearly ubiquitous big tech firms, and in a polarized political context like the contemporary United States. For instance, those on the right, especially strong partisans, became more negative over this period because of the perception that social media platforms were censoring conservative voices. Many moved to new platforms, especially in the wake of bans by Twitter and Facebook of President Trump. Partisans on the left have become more skeptical of social media platforms because of their inability to control misinformation before and after the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections. Some on the left also see big tech as exploitative, especially as these firms reported record profits during the Covid-19 economic downturn.

We expect these partisan trends more generally to manifest in two ways. First, we expect messaging that invokes fundamental human rights and obligations under UN human rights treaties to make left-leaning respondents more supportive of increasing regulations on tech firms. Multiple studies have found that Democratic partisans and individuals on the left are more supportive of humanitarian foreign policy (e.g. Rathbun, 2004, Kreps & Maxey, 2018). If such individuals are more likely to support the deployment of U.S. troops to protect human rights, they should also be more “primed” to worry about threats posed by tech firms when they are described as potential infringements on human rights. We therefore expect left-leaning respondents to be more “primed” to prefer additional government action when reading a human rights framed vignette.

At the same time, we expect the antitrust framing to resonate more with right-leaning individuals. A central tenet of economic conservatism is competitive markets. However, some evidence suggests that at the elite level, Republicans from more unequal parts of the country are less likely to support antitrust actions (cf. Allen et al. 2021), This suggests there may be limits to enthusiasm for government intervention to regulate markets among many self-identified Republicans. As such, although we expect Republicans to be more supportive of increasing regulations after reading an antitrust-framed vignette due to their preference for competitive markets, this effect may be attenuated by other factors like geography.

-

H1: Left-leaning and self-identified Democratic respondents are more likely to support additional regulations after reading a vignette focusing on human rights. Right-leaning and self-identified Republican respondents are more likely to support additional regulations after reading a vignette focusing on the importance of a competitive sector.

Second, we expect left-leaning individuals to be more likely to support increasing regulations on tech firms after seeing messaging from an international source. In recent years, the Republican party has viewed international institutions with skepticism, while many on the left view international organizations more favorably. For instance, Rapport & Rathbun (2021) argue that right-leaning parties are more sensitive to “sovereignty costs,” or the potential threat to sovereign governance, posed by international law and institutions (2021). Milner & Tingley (2013) find that Conservatives in the U.S. tend to oppose using multilateral aid channels, while Liberals prefer to channel aid through international institutions. This may be both a component of modern conservative ideology or a product of elite opinion leadership, or both. For instance, Brutger & Clark (2022) find in a series of survey experiments that partisans respond positively to co-partisan cues about funding IOs, and negatively to cues from opposing party elites. In particular, Republicans are more likely to reduce funding for IOs when primed by a partisan elite. Regardless, we expect partisanship and ideology to be powerful filters that influence individuals' receptivity to messages from IOs about regulating digital privacy.

-

H2: Left-leaning and self-identified Democratic respondents are more likely to support additional regulations after reading a vignette citing the UN Special Rapporteur or Privacy International. We expect vignettes citing these sources to have no effect on right-leaning and self-identified Republican respondents.

Finally, we return to the idea that the ability of IOs to persuade depends on perceptions of their motives and expertise. Individuals who value engagement with multilateral institutions are more likely to value their ideas and defer to their expertise. We expect individuals who score high on an index of internationalism to be more receptive to messages from international sources, while those that score low on internationalism should be unmoved by such messages.

-

H3: Respondents who score high on an index of internationalism are more likely to indicate support for increasing regulations on tech firms upon seeing a treatment message citing the UN Special Rappoteur or Privacy International as a source.Footnote 16

3 Survey and research design

We developed a survey experiment to disentangle the effects of message framing and message source on attitudes about tech regulation. Our factorial design included two types of message framing –- one focusing on fundamental human rights and one focusing on sector competitiveness –- and three message sources –- the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy, Privacy International, and the FTC. We included both an IGO and NGO source, as one might expect influence to vary. The UN Rapporteur is under the High Commission for Human Rights and thus carries the imprimatur of the UN, which may afford it more legitimacy. On the other hand, Privacy International is a lesser-known source, although its name clearly conveys its mission of promoting digital privacy. It is also an NGO, as opposed to an IGO, and therefore may be seen as less authoritative than an organization with state membership. We chose the FTC as a comparison source for several reasons. First, we wanted to assess the relative influence of a domestic source. Second, we chose an agency that would not sound particularly partisan and with a mandate relevant to the sector.

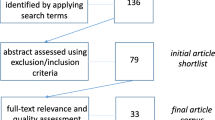

We fielded our survey on a nationally representative U.S. sample of 1,200 respondents, matched to a sampling frame on gender, age, race and education, through YouGov in July 2021. After reading a general introduction, respondents were randomly assigned to six treatment groups and presented with a vignette in the form of an excerpt from a news story. Respondents in a control group read no news story. We also collected demographic data, such as age, gender, partisanship, ideology, as well as two sets of questions to create indices of internationalism and political knowledge.

3.1 Treatments

Our vignettes were written as excerpts from news articles to mimic news consumption. The human rights message framed the necessity of tech regulation as important for fundamental human rights and invoked international human rights law and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). This vignette emphasized the right to privacy as a universal human right and its connections with other fundamental rights and freedoms, urging governments to review legislation and policies regarding personal data protection.

The antitrust message focused on anti-competitive practices and market power of large tech companies, calling for the enforcement of antitrust laws to prohibit monopolies within sectors. Both framings drew on language from real-world sources, such as the House Judiciary Committee's antitrust subcommittee, Privacy International's webpage, or the UN Rapporteur for Rights in the Digital Age's webpage. However, we adjusted the format and some wording to resemble a print news format. Below is the introduction shown to all subjects:

Introduction for all respondents: Recently, a number of concerns about the operation of U.S tech firms have arisen, ranging from how they use consumer data to lack of competition in the sector. In a moment, we will ask you whether you support more regulation on tech firms. Such regulation could include more rules about data privacy, actions that break up larger corporations, or new requirements for security of sensitive information, among other things. We will not ask about specific proposals, but rather whether you generally support or oppose increased regulation of tech firms.

We intentionally did not ask about either specific firms or regulations. However, since many respondents might not be familiar with the possible types of regulations, we listed some general categories. Our main interest was in whether respondents think more should be done with respect to regulation, rather than their opinion on specific regulatory options.

Below we present the human rights and antitrust vignettes. As noted above, respondents were randomly selected into receiving one type of framing, and then further randomized into seeing one of three message sources. A control group read no vignette.

Human Rights Frame:

Headline: Tech companies face scrutiny from RANDOMIZER (UN, NGO, or FTC) over human rights and privacy concerns.

Tech firms are receiving greater scrutiny both within and outside the United States, as human rights experts call for governments to protect the right to online privacy.

“The right to privacy is universally recognized under international human rights law, enabling the enjoyment of other fundamental political rights and freedoms,” said RANDOMIZER (the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy, a position appointed by the UN Human Rights Council; Privacy International, a London-based non-governmental organization dedicated to promoting digital privacy; a spokesperson for the Federal Trade Commission). “The capability of tech firms to gather, use and share personal data has grown exponentially, yet there isn’t a clear set of rules to prevent the arbitrary interference with individual privacy.”

While the right to privacy is not absolute, any instance of interference must be subject to a careful and critical assessment of its necessity, legitimacy, and proportionality. The RANDOMIZER (UN Special Rapporteur; Privacy International; Federal Trade Commission) urged governments to review legislation and regulatory policies for personal data protection, as states’ human rights obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political rights also extend to the digital world.

Antitrust Frame:

Headline: Tech companies face scrutiny from RANDOMIZER (UN, NGO, or FTC) over anti-competitive practices.

Tech firms are receiving greater scrutiny both within and outside the United States, as antitrust authorities call for measures to curb their market power.

“Lack of competition facing large tech firms has led to lower service quality and few options for consumers,” said RANDOMIZER (the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Privacy, a position appointed by the UN Human Rights Council; Privacy International, a London-based non-governmental organization dedicated to promoting tech regulation; a spokesperson for the Federal Trade Commission). “The central problem is that many of these firms are too large and control too great a market share.”

Many countries have laws that prohibit monopolies within sectors, which are harmful to consumers and the functioning of competitive markets. More recent debates involve the enforcement of antitrust laws targeting tech companies’ market power, due to their increasing dominance in online search and advertising. The RANDOMIZER (UN Special Rapporteur; Privacy International; Federal Trade Commission) called for effective enforcement of national competition laws and careful and critical assessment of tech firms’ operations.

Our 3 × 2 factorial design varies the framing (human rights vs. antitrust) and the source calling for more regulation. This is a relatively straightforward experimental design, allowing us to examine the direct effects of each dimension of manipulation as well as possible interaction effects. The design also allows us to test our subgroup hypotheses –- the main hypotheses of interest –- directly. Yet in a recent article, Grimmer and Fong (2021) point out that treatments using text often collapse “higher order” latent treatments, such framing, into text. The inferential danger is in identifying the causal effects of these latent treatments, which might be obscured by other, unmeasured latent treatments embedded in text wording. In order to identify the causal effect of a latent treatment, one must either assume that all unmeasured latent treatments do not interact with the intended treatment, or conduct auxiliary analysis to measure other latent treatments and treat them as potential confounders. The problem is analogous to ommitted variable bias in a regression framework.

Our treatment design takes the possibility of unmeasured latent treatments seriously. First, within each treatment framing (human rights vs. antitrust), we randomize only the source calling for more regulation. Otherwise our vignettes are exactly the same within issue framings. Across framings, our vignettes diverge somewhat, though we keep the length, phrasing, and style as identical as possible to limit the possibility of unmeasured latent treatments interacting with our intended treatment of framing.Footnote 17 Given that our treatment vignettes are nearly identical within each of our two issue framings, and given that the two framings are of relatively short and of similar length, style, and structure, we are comfortable assuming that any unmeasured latent treatments do not interact with our two dimensions of variation, source and framing.

3.2 Outcome measures

After random assignment to treatment or control groups, respondents were asked: "Do you agree or disagreement with the following statement? Big tech firms in the U.S. should be subject to more stringent regulations." We coded the answer on a five-point scale: strongly disagree (1), disagree(2), not sure(3), agree(4), strongly agree(5). In addition to the question on tech regulation, we asked respondents three questions about digital privacy: willingness to alter online privacy settings, willingness to read more about digital privacy concerns, and willingness to stop using services with unsatisfactory privacy policies.

3.3 Moderators

We hypothesize the ATE will be moderated by preexisting beliefs and policy preferences, such as partisanship, ideology, and internationalist orientation. We asked respondents to self-identify on a 7-point scale: strong Democrat, not very strong Democrat, lean Democrat, Independent, lean Republican, not very strong Republican, strong Republican, not sure. Then we created a 3-point variable based on the 7-point Party ID: Democrat, Independent, and Republican. Ideology is measured on a 5-point scale: very liberal, liberal, moderate, conservative, very conservative, not sure, and also collapsed into a 3-point variable: liberal, moderate, and conservative.

We constructed an index of internationalism based on five questions, including the role of the U.S. in world affairs, attitudes toward trade, immigration, military allies, and multilateral institutions. The questions are as follows:

-

1. Generally speaking, should the U.S. be more or less involved in world affairs?

-

More involved, No change, Less involved, Don’t know, not sure

-

2. In order to stimulate economic growth, do you think the United States should pursue more trade agreements with other countries, or seek to limit international trade in order to protect American-made products?

-

Pursue trade agreements, Limit imports, Don’t know, not sure

-

3. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: “Immigration is important for U.S. economic growth and cultural development.”

-

Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Don’t know/aren’t sure, Agree, Strongly Agree

-

4. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: “It is important for the United States to consult and work with allies when considering military action abroad."

-

Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Don’t know/aren’t sure, Agree, Strongly Agree

-

5. Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statement: “It is important for the United States to consult and cooperate with multilateral institutions, like the United Nations and World Trade Organization when conduction foreign policy.”

-

Strongly Disagree, Disagree, Don’t know/aren’t sure, Agree, Strongly Agree

We coded the respondents’ answer as 1 if they indicate positive attitudes toward internationalism, specifically "more involved", "pursue trade agreements", "strongly agree", and "agree." We coded the answer as 0 if they chose "no change", "less involved", "don't know/not sure", "limit imports", "disagree", "strongly disagree." We constructed an index of internationalism, adding up the scores of the five questions for each respondent. This index ranges from 0 to 5, with 3 as the median, and 2.525 as the mean. For the analyses below, we coded 0–2 as "low internationalism" and 3–5 as "high internationalism."

To measure political knowledge, we asked respondents four questions, adapted from Rathbun et al. (2016):

-

1. How many four-year terms can a U.S. President serve?

-

1, 2, 3 or unlimited.

-

2. Which is the largest economy in the world?

-

China, Germany, Japan, The United States

-

3. Which of the following is a responsibility of the United Nations Security Council? Conducting trials of indicted war criminals, enforcing international trade agreements, or authorizing the international use of military force

-

4. Which office does Anthony Blinken currently hold?

-

Secretary of Defense, Secretary of State, Attorney General, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations

We coded the correct answer as 1 and incorrect 0. We then added the scores of the four questions to construct an index of political knowledge. On a scale of 0–4, the political knowledge variable has a median of 2 and a mean of 2.307. We divided the respondents to "low political knowledge"(0–2 points) or high political knowledge (3–4 points).

We also collected information on respondents' demographics. Given the randomization of respondents across treatments, demographic factors should not pose inferential challenges as confounders. Nonetheless, we checked for covariate balance, and found that our treatment groups appeared similar on most demographics. The exception is the percent of black respondents in the human rights and domestic source treatment is somewhat lower than in other treatments. The percent of respondents who identified as “other race” is lower in the NGO antitrust treatment and in the domestic source and antitrust treatment. We don't have strong reasons to think these differences would bias our results. Table 1 in the Appendix reports summary demographic statistics.Footnote 18

4 Results

We fielded the survey in July, 2021, when antitrust investigations and lawsuits were getting frequent media coverage in the U.S. Our data reflect the growing momentum to regulate tech firms identified in public polling from this period. On the question “whether Big Tech should be subject to more rather than less regulation”, 850 out of 1200 respondents answered agree (4) or strongly agree (5). As a result, the variation in the dependent variable is somewhat limited, which may attenuate treatment effects. The public might have simply had less “room to move” during this period, which makes ours a somewhat conservative test of the effects of message source and framing. However, we find support for several of our subgroup hypotheses, both when examining average treatment effects (ATE) in the full sample and the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT), or those who were able to correctly answer post-treatment questions about the vignette they read.Footnote 19 As this survey experiment was pre-registered, we report both null and positive results in the following sections.

4.1 Average treatment effects

To begin, Fig. 1 displays the difference in means across all treatment and control groups. As is clear from the Figure, although the highest levels of support for regulation were observed in the IGO and Human Rights treatment condition, the difference between means across groups is statistically insignificant. Apart from the IGO and human rights treatment, the NGO and antitrust, U.S. and antitrust, and control groups cluster very close together. The groups with the lowest average support for regulation were in the NGO and human rights, the U.S. and human rights, and the IGO and antitrust groups. Figure 1 in the Appendix reports ATTs.

Figure 2 shows the difference in means across groups, comparing first, in the left panel, whether the group read a story citing an international source (The UN Special Rapporteur or Privacy International) or a domestic source (the FTC). In the left panel, the means of the groups that received international source treatments (IGO or NGO) are similar to the group that received a domestic source. The right panel compares groups that read a story emphasizing human rights with those that read an antitrust message. The mean across groups that received an antitrust treatment is higher than across groups that saw the human rights message, although the difference is not significant.

Figure 3 shows the ATT, also broken down by source. Once we restrict analysis to respondents who correctly answered the manipulation checks, the difference in means for respondents who read a human rights message and those who read an antitrust message is larger, but not statistically significant. Contrary to our expectations, respondents who read antitrust messaging expressed higher support for increasing tech regulations. It's possible that antitrust messaging resonates more with a U.S. sample, though we can only provide conjecture given the lack of significance.

One potential reason for the similarity across treatment groups might be that respondents did not view the source and message as independent. Figure 1 shows the highest mean support for increasing regulation in the treatment group that read a story citing the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights and emphasized fundamental human rights. The two other treatment groups that emphasized human rights showed the lowest support for increased regulation. As a result, the overall mean of the human rights treatments might be diluted, as the means of those three groups is averaged across highest and lowest. Why might be this be the case? It's possible that the human rights framing is most influential and compelling when it comes from (a) an authoritative institution and (b) when that institution's mission directly invoke rights. The FTC, on the other hand, is unlikely to emphasize human rights or appeal to instruments like the ICCPR, which might make that particular treatment seem discordant. In former case, the effect of the antitrust framing could be attenuated when the UN Special Rapporteur is mentioned, as the source invocation might imply that privacy rights are emphasized as well. In the latter, the effect of the human rights framing could be attenuated when the FTC is mentioned as the source, because the FTC is associated with fair business practices and thus might imply a more market-focused critique. Finally, Privacy International, though a prominent NGO, is relatively unknown to the general public, which might help explain the lack of a strong treatment effect from vignettes citing it as a source.

4.2 Sub-group analysis

When we group respondents based on ideology, partisanship, and attitudes toward internationalism, we begin to see significant treatment effects. The left panel of Fig. 4 displays the difference in means for respondents by high and low score on internationalism who received a treatment citing an international source (UN Special Rapporteur or Privacy International). The difference is significant, with respondents scoring high on internationalism indicating higher levels of support than those who scored low upon reading a treatment citing an international source. This is consistent with our supposition in H3 that perceptions of the source and pre-existing attitudes about multilateralism condition persuasiveness.

ATE of international vs. domestic source, moderated by internationalism. Note: The left panel displays groups that received treatment of international sources, and the right panel shows the groups that received the U.S. treatment. Regarding treatments that cite an international source, the t-test between high and low internationalism is statistically significant (p-value is 0.0001)

The right panel of Fig. 4 shows the difference in means across respondents that scored high and low on internationalism who read a treatment citing the FTC. This panel shows no significant difference across high and low internationalism. Figure 12 in the Appendix, reporting the ATT, shows similar patterns.

Figure 5 shows the difference of means by partisanship (Republican, Democrat, Independent), according to whether respondents read a vignette citing an international or domestic source. Figure 6 shows a similar comparison, broken down by ideology (conservative, liberal, moderate). Recall that H2 predicted Democrats and Liberals will be more likely to be persuaded by international sources, since the Democratic party in recent years has pursued multilateralism while Republican party elites have frequently attacked international institutions. The findings in Figs. 5 and 6 support this claim. Liberals and Democrats report the highest levels of support for increasing regulation after reading stories citing international sources, while conservatives and Republicans show the highest levels of support after reading a treatment vignette citing the FTC. These patterns appear, if anything, even starker when we examine the ATT's (Figs. 13} and 15 in the Appendix.

These findings, together with differences across high and low internationalism, support our expectation that the effectiveness of messaging from IOs and NGOs will be filtered by preexisting attitudes and partisan attachments.Footnote 20 International organizations and NGO campaigns seem to resonate with some individuals more than others, despite the overall high support for increasing tech regulations observed in our sample.

These patterns hold when we analyze other behavioral outcome measures. For instance, we asked respondents how likely they would be to alter their privacy settings after reading the treatments. Figure 7 shows the ATE of international and domestic source treatments, by internationalism, on the likelihood of altering one's privacy settings. Again, international sources seem to resonate more for those that score high on internationalism, consistent with H3.

In only a few instances we found slightly different treatment effects with respect to other outcome variables. For example, recall that when examining support for increasing regulation, we found no significant difference between human rights and antitrust treatments. We similarly found no significant differences across human rights and antitrust framings when broken down by ideology or partisanship, as H1 predicted. However, when we asked respondents whether they would read more about digital privacy after treatment, we observe a larger ATE among respondents who read an antitrust message. Figure 8 shows this comparison.

We also found that Republicans and Conservatives were more likely to stop using services with inadequate privacy policies regardless of treatment, as shown in Fig. 13 and 14 in the Appendix. This is likely due to the migration of many Republicans and conservatives from Twitter and Facebook during this period as a result of the de-platforming of President Trump.

Although we are agnostic about the effects of political knowledge, given the timing of our survey in July 2021 it is worth investigating whether respondents who are more politically aware responded differently to our treatments.Footnote 21 As noted above, we constructed an index of political knowledge, including questions about the following: the term limit of the U.S. President, the largest economy in the world, the role of the UN Security Council, and the title of Antony J. Blinken. Figure 9 shows comparisons of means across political knowledge groups. Compared to differences in means of international and domestic sources, the political knowledge subgroups show greater differentiation upon reading the antitrust framing. Respondents with high political knowledge (3–4 points) show higher support for tech regulation when they receive antitrust message framing, while the respondents with lower political knowledge (0–2 points) show few differences across message source or framing. Figure 9 also shows high political knowledge individuals express more support for increased tech regulation after reading messages from international sources, though this difference becomes statistically insignificant when we look at the ATTs in Fig. 17 in the Appendix.

These patterns are perhaps unsurprising, given reporting of antitrust actions in the U.S. during this period. More knowledgeable respondents are more likely to read news about these cases and understand the problem facing regulators as an antitrust issue. These antitrust cases do not appeal to international law or human rights treaties, nor do they frame the power of tech firms as fundamental threats to human rights or democracy. Therefore, treatments that emphasized sector competitiveness may resonate with individuals aware of these cases.

Finally, one of our political knowledge questions asked respondents to select the largest economy in the world, listing both the U.S. and China among the answers. Some recent work on trade preferences finds that mention of China or exposure to import competition from China can activate protectionist attitudes (e.g. Dorn et al., 2020; Kerner & Sumner, 2020; Kerner et al., 2020). Digital privacy is closely connected to support for trade wars with China, insomuch as U.S. legislators –- especially on the right –- have accused China of intellectual property theft and corporate espionage. Incorrectly identifying China as the world's largest economy may reflect respondents' sense of threat of economic competition from China. If this is the case, does it affect how respondents understand our treatments?

Figure 10 shows the difference in means for antitrust versus human rights framing across respondents who identified China as the world's largest economy and those who correctly identified the U.S. The two groups show little difference in support for increasing tech regulations when exposed to antitrust messaging. However, those that identified China as the largest economy were significantly more supportive of increasing tech regulation after reading a human rights framing relative to those who correctly identified the U.S.

This finding is purely exploratory,Footnote 22 but it may connect to larger themes about how attitudes toward China shape politics in the U.S. Respondents that view China as threatening may have read our human rights treatment as suggesting a contrast between the American system, prioritizing freedom from government surveillance and intervention, and the Chinese system. If so, calls for countries to abide by their human rights commitments may resonate strongly.

5 Conclusion

Our results speak to the conditional ability of IOs and NGOs to act as norm entrepreneurs. We did not observe large differences across individual treatment groups. However, we found significant differences across subgroups separated by attitudes toward internationalism, ideology, and partisanship. This is consistent with literature that suggests source credibility differs across individuals and the effectiveness of advocacy campaigns often depends on how audiences view the messengers.

We also found that Conservatives and self-identified Republicans are more likely to support increased tech regulation when exposed to antitrust messaging and when the source is the FTC. This is consistent with partisan attitudes that emphasize free –- and fair –- market competition, but a skepticism of international institutions.

The ability of private firms to collect, and make profit on, users' personal information raises significant ethical issues. Beyond ethics, the practice may pose very real threats to basic democratic freedoms. IOs and NGOs are at the vanguard of establishing norms of appropriate behavior and “best practices” for regulation. Our findings suggest these efforts can be persuasive, but only for particular groups.

Persuasion is a long-term process and survey treatments are a very short-term intervention. However, our findings suggest IO and NGOs campaigns may give even skeptics reason to rethink their current privacy practices or learn more about the issues. Those may seem modest goals, but are important steps toward the larger goal of shifting attitudes.

Finally, our research speaks to a wider debate about when IOs influence public opinion and when they do not. Some IOs are clearly authoritative in certain issue areas, and they utilize that expertise in how they craft messages. The UN Special Rapporteur for Privacy Rights in the Digital Age, embedded within the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, focuses on the implications of practices like collecting user data for fundamental rights. But it is a relatively new and unfamiliar office and respondents that dislike the UN –- either because they fear the sovereignty costs of supranational governance or cues from copartisan elites –- are unlikely to be very moved by its messaging. Other IOs, like the IMF, that deal in very technical issue areas where respondents have not formed strong predispositions against IOs, might be more broadly regarded as having relevant authority over their domains, and thus more influential in their messaging. Our research points to a need to move beyond looking for monocausal effects of IO messaging and instead suggests exploring how individual and group characteristics condition the influence of IO signals and messages.

Notes

Emily A. Vogels, June 21, 2021, “56% of Americans support more regulation of major technological companies,” Pew Research Center.

Megan Brenan, February 18, 2021, “Views of Big Tech Worsen; Public Wants More Regulation,” Gallup https://news.gallup.com/poll/329666/views-big-tech-worsen-public-wants-regulation.aspx.

See Silvia Amaro, "How Europe Became the World's Top Tech Regulator,'' CNBC, 25 March 2021, https://www.cnbc.com/2021/03/25/big-tech-how-europe-became-the-worlds-top-regulator.html.

Our survey design was registered with EGAP, study #20210616AB.

Page and Shapiro (1992) argue that public opinion moves in coherent ways, and others have pointed out that even when citizens lack information about specific policies, they can use elite cues and other heuristics to form attitudes (Lupia and McCubbins 1998).

In a recent paper employing a conjoint experiment in both the U.S. and Germany, Dellmuth and Tallberg (2022) provide evidence that perceptions of IO legitimacy are filtered through pre-existing attitudes. Individuals with a more “internationalist” orientation are more likely to perceive IOs as legitimate.

Authors' interview with Gus Hosein, Executive Director of Privacy International October 26, 2021.

United Nations (2020).

Indeed, Gus Hosein, Executive Director of Privacy International, attributes the traction of the antitrust movement to the U.S. having existing institutions to litigate trust cases, which is easier than creating a new regulatory body to protect consumers' privacy (authors interview October 26, 2021).

E.g. Jones et. al 2009 show the importance of public priorities for policy response.

Megan Brenan, February 18, 2021, "Views of Big Tech Worsen; Public Wants More Regulation,'' Gallup https://news.gallup.com/poll/329666/views-big-tech-worsen-public-wants-regulation.aspx.

See Sam Sabin, April 27, 2021, "States Are Moving on Privacy Bills. Over 4 in 5 Voters Want Congress to Prioritize Protection of Online Data," Morning Consult, https://morningconsult.com/2021/04/27/state-privacy-congress-priority-poll/.

H1-H3 were pre-registered with EGAP (#20210616AB).

Fong and Grimmer recommend using as many as 100 vignettes (or more) per treatment. This was infeasible for our study, so while we acknowledge the importance of potential unmeasured latent treatments, we rely on our traditional design of keeping treatment vignettes as similar as possible, except for the randomized element of interest, to minimize the possibility of unmeasured latent treatments.

The online appendix is available on the Review of International Organizations' webpage.

We asked respondents two post-treatment questions for a manipulation check: what message was emphasized, and what source of information was mentioned? Of 506 respondents who received a human rights treatment, 304 answered human rights; of 517 who read an antitrust treatment, 413 correctly identified antitrust. In terms of information sources, 233 out of 343 answered correctly about UN Special Rapporteur, 168 out of 345 answered correctly about Privacy International, and 207 out of 335 answered correctly about the Federal Trade Commission.

Dellmuth and Tallberg, in conjoint experients in the U.S. and Germany, reach similar conclusions.

We did not pre-register a hypothesis about the moderating effect of political knowledge.

We did not pre-register a hypothesis pertaining to this finding.

References

Abbott, K. W., & Snidal, D. (1998). Why states act through formal international organizations. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 42(1), 3–32.

Allen, M. O., Scheve, K., & Stasavage, D. (2021). Democracy, Inequality, and Antitrust. Working paper. Available at https://www.modallen.com/assets/papers/DemIneqAntitrust_Dec2021.pdf.

Barnett, M. N., & Finnemore, M. (1999). The politics, power, and pathologies of international organizations. International Organization, 53(4), 699–732.

Barnett, M., & Finnemore, M. (2005). The power of liberal international organizations. Power in Global Governance, 161, 163–171.

Berinsky, A. J. (2007). Assuming the costs of war: Events, elites, and American public support for military conflict. Journal of Politics, 69(4), 975–997.

Bowen, T. R. & Broz, J. L. (2021). The Domestic Political-Economy of the WTO Crisis: Lessons for Preserving Multilateralism. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3920630 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3920630.

Brutger, R., & Clark, R. (2022). At what cost? Power, payments, and public support of international organizations. Review of International Organizations, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-022-09479-9.

Chapman, T. L. (2012). Securing Approval: Domestic Politics and Multilateral Authorization for War. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Chaudoin, S. (2014). Promises or policies? An experimental analysis of international agreements and audience reactions. International Organization, 68(1), 235–256.

Chaudoin, S. (2016). How contestation moderates the effects of international institutions: The International Criminal Court and Kenya. Journal of Politics, 78(2), 557–571.

Dai, X. (2005). Why comply? The domestic constituency mechanism. International Organization, 59(2), 363–398.

Dellmuth, L., & Tallberg, J. (2022). Effects of Institutional Legitimation in International Organizations on Popular Legitimacy. Paper presented at the 14th annual conference on the Political Economy of International Organizations, Oxford, UK.

Dorn, D., Hanson, G., & Majlesi, K. (2020). Importing political polarization? The electoral consequences of rising trade exposure. American Economic Review, 110(10), 3139–3183.

Farrell, H., & Newman, A. L. (2019). Of Privacy and Power: The Transatlantic Struggle over Freedom and Security. Princeton University Press.

Farrell, J., & Rabin, M. (1996). Cheap talk. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 10(3), 103–118.

Finnemore, M. (1996). National interests in international society. Cornell University Press.

Finnemore, M. (2009). International organizations as teachers of norms the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization and science policy. International Organization, 47(4), 565–597.

Finnemore, M., & Sikkink, K. (1998). International Norm Dynamics and Political Change. International Organization, 52(4), 887–917.

Fong, C., & Grimmer, J. (2021). Causal inference with latent treatments. American Journal of Political Science, forthcoming.

Greenhill, B. (2020). How can international organizations shape public opinion? Analysis of a pair of survey-based experiments. Review of International Organizations, 15(1), 165–188.

Guisinger, A., & Saunders, E. N. (2017). Mapping the Boundaries of Elite Cues: How Elites Shape Mass Opinion Across International Issues. International Studies Quarterly, 61(2), 425–444.

Holsti, O. R. (2004). Public Opinion and American Foreign Policy. University of Michigan Press.

Jones, B. D., Larsen-Price, H., & Wilkerson, J. (2009). Representation and American Governing Institutions. Journal of Politics, 71(1), 1–14.

Kerner, A., & Sumner, J. L. (2020). Salvation by good works? Offshoring, corporate philanthropy, and public attitudes toward trade policy. Economics and Politics, 32(1), 1–27.

Kerner, A., Sumner, J., & Richter, B. (2020). Offshore Production’s Effect on Americans’ Attitudes Toward Trade. Business and Politics, 22(3), 539–571.

Kreps, S., & Maxey, S. (2018). Mechanisms of Morality: Sources of Support for Humanitarian Intervention. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 62(8), 1814–1842.

Lupia, A., McCubbins, M. D., & Arthur, L. (1998). The democratic dilemma: Can citizens learn what they need to know? Cambridge University Press.

Milner, H. V., & Tingley, D. (2013). The choice for multilateralism: Foreign aid and American foreign policy. Review of International Organizations, 8(3), 313–341.

Page, B. I., & Shapiro, R. Y. (2010). The rational public: Fifty years of trends in Americans’ policy preferences. University of Chicago Press.

Rapport, A., & Rathbun, B. C. (2021). Parties to an alliance: Ideology and the domestic politics of international institutionalization. Journal of Peace Research, 58(2), 279–293.

Rathbun, B. C. (2004). Partisan Interventions: European Party Politics and Peace Enforcement in the Balkans. Cornell University Press.

Rathbun, B. C., Kertzer, J. D., Reifler, J., Goren, P., & Scotto, T. J. (2016). Taking foreign policy personally: Personal values and foreign policy attitudes. International Studies Quarterly, 60(1), 124–137.

Solomon, J. M. (2010). New governance, preemptive self-regulation, and the blurring of boundaries in regulatory theory and practice. Wis. L. Rev. 2010(2): 591-626.

Soroka, S. N., & Wlezien, C. (2010). Degrees of Democracy: Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy. Cambridge University Press.

Stimson, J. A. (2015). Tides of consent: How Public Opinion Shapes American politics. Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, A. (2006). Coercion through IOs: The Security Council and the logic of information transmission. International Organization, 60(1), 1–34.

United Nations. (2020). Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights: Impact of new technologies on the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of assemblies, including peaceful protests. Annual report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights and reports of the Office of the High Commissioner and the Secretary-General A/HRC/44/24. Available at {https://undocs.org/A/HRC/44/24}.

Wallace, G. P. R. (2013). International law and public attitudes toward torture: An experimental study. International Organization, 67(1), 105–140.

Wlezien, C. (1995). The public as thermostat: Dynamics of preferences for spending. American Journal of Political Science, 39(4), 981–1000.

Funding

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Overall T.C. 50%, H.L. 50%; survey design T.C. 50%, H.L. 50%; Analysis T.C. 25%, H.L. 75%; writing T.C. 75%; H.L. 25%. The authors’ names are listed alphabetically.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Responsible editor: Axel Dreher

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The survey described in this paper was pre-registered with Evidence in Governance and Politics (EGAP) #20210616AB. The study was approved by the University of Texas IRB, STUDY00000760. We thank Bethany Albertson, Roman Hlatky, Mike Findley, Bryan Jones, Christoph Mikulaschek, Dan Nielsen, and Cleo O’Brien Udry for helpful suggestions.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chapman, T.L., Li, H. Can IOs influence attitudes about regulating “Big Tech”?. Rev Int Organ 18, 725–751 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-023-09490-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-023-09490-8