Abstract

The coronavirus pandemic and measures to protect against the spread of infection have had a specific effect on individual age groups. This research is focused on adolescents (from 13 to 19 years old) because young people at that age are already going through a developmental crisis, which is further intensified by pandemic circumstances. The survey, conducted in Croatia from December 2020 to February 2021 (N = 857), sought to identify the possible personalizing of faith in adolescents as well as the impact of religiosity on their coping with the pandemic, especially in terms of social-emotional resilience and personal growth. In addition to descriptive indicators, the analysis used inferential procedures to check the statistical significance of differences (t-test, ANOVA), as well as connections and determinations between variables (correlation and regression analysis). The hypotheses were confirmed that the faith of religious adolescents became more personal and that it had a positive effect on psycho-social resilience and personal growth, but in combination with family cohesion, which on the one hand was stimulated by religiosity, and on the other, influenced personal growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 The crisis caused by the corona virus pandemic

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (2020), declared a pandemic of the disease COVID-19 and on the same day the Minister of Health of the Republic of Croatia made a decision to declare an epidemic of the disease COVID-19 caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus throughout the country (Beroš, 2020). At the end of March 2020, Croatia was among the countries that had the strictest protection measures against the spread of the infection, which included school closures, travel restrictions and a ban on gatherings. On March 16, 2020, all educational institutions in the country were closed. The younger grades of the elementary school (1–4) had lessons via public television, while other pupils and university students switched to distance learning. The strictest protection measures lasted until May 10, 2020 (Ministarstvo unutarnjih poslova, 2022), but when Zagreb was hit by a strong earthquake of magnitude 5.5 and 5.0 on the Richter scale on March 22, 2020 (Seizmološka služba, 2020), due to damage to buildings, many educational institutions in the city continued with distance learning until the end of the school or academic year 2019/2020.Footnote 1 After the easing of restrictions during the summer, the measures were tightened again at the end of October 2020, due to the increase in the number of infected and dead, but in a milder form than in the first phase of the lockdown. In the new school and academic year 2020/2021 classes were mostly held in hybrid form, depending on the state of infection in individual classes, schools and faculties. In the first half of April 2022, most measures to prevent the spread of the virus in Croatia were removed or reduced to recommendations (Vlada Republike Hrvatske, 2022).

The pandemic and the measures to prevent the spread of infection have changed the previous way of living, working, learning, communicating and spending leisure time. The changes required adaptation, resilience and creation of new life habits, which were especially marked by the use of communication media, work and schooling from home, extended stay indoors and socializing in a small circle of people. Fear of illness and death and direct encounters with them, as well as restrictions on the usual free movement and socializing, have had an unfavourable effect on the emotional and social life, and thus on the mental health of many people (Torales et al., 2020; Flynn et al., 2020). Parents were additionally burdened with helping their children in learning, and many citizens also questioned the rationale of restrictive measures, prompted by different interpretations spread throughout the media of the origin and goal of the pandemic, as well as the enforced protective measures.

However, the pandemic could manifest itself not only as a threat, but also as a challenge and an opportunity for a new connection and alliance of people in individual responsibility and joint action. The pandemic has given people the opportunity to become aware of the importance of health as something that is not necessarily implied, the benefit of slowing down in relation to the excessive acceleration of life in modern society, the importance of connection with others, with the community and with nature in a time of the predominance of individualism, economic interests and irresponsible exploitation of natural resources. In this sense, the circumstances of the pandemic were an existential challenge, requiring a new way of thinking and solving problems, a true time of crisis and discernment that required adaptation and resilience and provided an opportunity for personal growth (Pope Francis, 2020).

1.2 Consequences of the pandemic and adolescents

Researchers warn of the risk of permanent damage to mental health as a consequence of the pandemic, especially among vulnerable groups (Antičević, 2021; Jones et al., 2021). Research suggests that the pandemic could have long-term adverse effects on children and adolescents, although the negative effects depend on the specific circumstances of the pandemic threat and protective measures, as well as other individual and social characteristics of children and adolescents, and should be viewed intersectionally (Singh et al., 2020; Jiao et al., 2020; European Commission, 2022). According to some research, adolescents were more worried about the government’s anti-epidemic measures than about the possibility of contracting COVID-19, and this affected their mental health and reduced life satisfaction (Magson et al., 2021). Risk factors for the deterioration of mental health in children and adolescents are female gender, socio-economic background, attending high school, living near the epicenter of the pandemic, and poor coping strategies, such as the use of addictive substances (Flynn et al., 2020; Magson et al., 2021).

Research among adolescents in Croatia (Filipović & Rihtar, 2022) showed that the respondents (13–19 years old) coped relatively well with the challenges of the pandemic crisis. Nevertheless, about one quarter of the surveyed experienced states of listlessness, followed by sadness and anxiety during and because of the pandemic, to a fair extent or extremely. Girls experienced negative emotions more often than boys. However, no difference was observed in coping with the pandemic between younger and older adolescents. This paper will analyze the relationship between the social-emotional consequences of pandemic circumstances and the personal growth of adolescents with regard to the role of religiosityFootnote 2 as a possible factor of resilience. First, the basic constructs of “adolescence”, “religiosity” and “personal growth” will be explained.

2 Adolescence, religiosity, crisis and personal growth

2.1 Characteristics of adolescence and religiosity in adolescence

Adolescence is perceived in Western culture as a complex and turbulent period of life, associated with a large number of physical, psychological and social changes and tasks, challenges and risks (Rukavina & Nikčević-Milković, 2016). Physical changes are accompanied by rapid growth of brain structures, which enables the development of abstract thinking. Confronted with societal expectations, especially regarding education and achievement, young people must build their own autonomy and learn to live between sociocultural independence and economic dependence on parents (Flammer & Alsaker, 2002). New cognitive abilities help them develop a new concept of themselves (Kuzman, 2009; Novak et al., 2019), independently define their own identity and develop their personality. On the emotional level, the need to be understood is very pronounced (Fend, 2001). Young people rehearse their social roles through relationships with peers and the creation of the first affectional bonds. The understanding and realization of the aforementioned developmental tasks are influenced by the circumstances of the culture, society, social environment and time in which adolescents live. Some empirical research shows that adolescents today are more exposed to various psychological and social pathologies such as anxiety, depression and stress than previous generations (Poljak & Begić, 2016; Torralba et al., 2021). A UNICEF study conducted in 2019 among nine million adolescents aged 10–19 shows that 16.3% of adolescents in Europe and 13.2% worldwide suffer from a mental disorder. The percentage of adolescents in Croatia in that report amounts to 11.5% (UNICEF, 2021).

The changes that occur in adolescence also affect religiosity if it is part of the adolescent’s identity. Cognitively, adolescents are able to think about religious issues in a more complex way than children. The development of personality and independence contributes to their tendency to critically question religious ideas from childhood and everything that supported a religious view of the world. Reshaping religious ideas can lead to different forms of personal religiosity (Streib & Gennerich, 2011), and this usually happens in the interaction between religious autonomy and following role models (Dieterich, 2012). This process takes place within different social environments in which adolescents develop, and which shape not only individual lifestyles, but also value orientations and ideas about what is considered a good and fulfilling life and what they want to achieve (Ebertz, 1998). In Croatia, the religious values of the environment in which adolescents live are shaped by the historical and cultural significance of the Catholic Church, to which 80.3% of the population belongs, according to research carried out as part of the international research project European Values Study in 2018, and by institutional church religiosity. However, what is noticeable as well is the impact of secularization and individualization associated with the loss of meaning of religious institutions (Nikodem & Zrinščak, 2019). The formation of religiosity is also influenced by the social class and the youth culture to which adolescents belong. Research on the social milieus to which young people in Germany belong has shown that young people from traditional and civil environments gravitate towards Christian offers of meaning, while those from modern environments tend towards alternative spiritual offers with a greater degree of self-determination (Riegel & Faix, 2015).

2.2 Religiosity as a resource in crisis situations and personal growth

Research shows that both adolescents and adults experience also positive psychological changes in the face of crises and stressful life experiences, which they define as personal growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996; Kilmer et al., 2014). The concept of personal growth can take on different meanings in different cultures, as shown by Dominick and Taku’s research (2019) among Japanese and American adolescents (aged 13–19). Although there are common characteristics that the youth associate with personal growth, Japanese adolescents associate personal growth more with social connection, while American adolescents associate it with change. This brings to the fore that the concept of personal well-being and personal growth in the East Asian value system and way of thinking is more characterized by belonging to a community while in the Euro-American one it is determined more by the concept of one’s own independence.

Individual resources help people overcome crisis situations. Among the different subjective resources (physical, material, social and psychological) is also religiosity. Religiosity means a subjective attitude towards religion, the subjective formation of religious beliefs (teachings, rituals, communal and ethical consequences) and their expression in one’s own life and experience. Religiosity can be a source of personal well-being, strength in crisis situations and an incentive for personal growth and the formation of better social relations. Many studies show that religiosity has a positive effect on people’s physical and mental health (Koenig et al., 2001; Loewenthal, 2009; Unterrainer et al., 2014). The connection between religiosity and the psychological well-being of individuals is shown to be positive and statistically significant, although not big (Dilmaghani, 2018). Among the population in some countries, such as the United States of America, religiosity is shown to be positively related to psychological satisfaction (happiness), while in other countries, where the religiosity of the population is even higher, this is not the case (Cragun & Speed, 2022). Religiosity, however, proves to be a protective factor that contributes to identity stability in situations of threat to one’s identity (Phillips et al., 2021).

3 Research among Croatian adolescents

3.1 Aim and hypotheses

The aim of the analysis is to examine the relationship between religiosity and the social, emotional and developmental consequences of the pandemic among adolescents (13–19 years old) in Croatia.

In accordance with the goal, the following working hypotheses were set:

H1

Influenced by the pandemic, the faith (religiosity) of adolescents became more personal.

The hypothesis is based on the fact that the pandemic manifested itself as an existential crisis that encourages the search for one’s own solutions. In addition, faith is transformed in adolescence either to become more personal or to lose its meaning in life.

H2

Faith contributed to greater emotional and social resilience of adolescents.

The hypothesis is based on the fact that faith (religiosity) often proves to be a resource for coping with crises, including those of a social-emotional nature.

H3

Faith stimulated personal maturation and personal growth in adolescents.

The hypothesis is based on the knowledge that the pandemic circumstances could have contributed to a more intensive growth of maturity and that religion provided incentives for this.

3.2 Method

3.2.1 Sample, carry out and circumstances of the study

The research was conducted during the second half of the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Croatia, which lasted from October 2020 to February 2021, and when Croatia had somewhat milder measures compared to the very rigorous ones put in place during the first wave (Kratka povijest pandemije, 2022). The research was conducted through an online survey, for which participants were recruited with the help of religious education teachers in certain schools (with the permission of the principal and parents), in accordance with the ethical norms relating to research among minors, and with the approval of the Ethics Committee of the Catholic Theological Faculty of the University of Zagreb.

Due to multiple limitations, including circumstances caused by the pandemic, it was not possible to conduct the research on a representative sample of adolescents. Instead, an attempt was made to make the sample as heterogeneous as possible (according to gender, age, type of school and territorial dispersion) so that the variables used would be sufficiently discriminatory and enable a wider interpretation of their mutual relations.

The survey, conducted from December 20, 2020 to February 28, 2021, included students in the final grades (seventh and eighth) of primary schools, and high school students. A total of 28 schools from seven towns and smaller settlements from different parts of Croatia were contacted.Footnote 3 17 responded: eight primary, five vocational and four high schools. 857 students participated in the survey. The structure of the realized sample according to their relevant characteristics is shown in Table 1.

3.2.2 Selection of variables for the analysis

Considering the circumstances caused by the pandemic and the characteristics of the target population, an effort was made to make the questionnaire as short as possible in order to increase the response rate, reduce fatigue and possible attrition of the sample, that is, to preserve the validity of the research in general. Therefore, individual indicators or constructs are covered mainly with one or a smaller number of particles designed for this research instead of extensive psychological instruments and scales (Questionnaire, 2020). The following variables were selected for this analysis: religiosity, consequences for religious practice, social consequences, emotional consequences and consequences for personal growth.

Religiosity or the importance of religion in adolescents was examined with the question “How important is religion to you in your life?”, where they could answer on a scale from 1 (It is not important to me at all, I am not a believer) to 5 (It is extremely important to me). What was also examined was whether faith took on a more intrinsic quality during the pandemic by stating “My faith has become more of my personal relationship with God than an external obligation”. Answers were recorded on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely).

The subjective consequences of the pandemic on religious practice and its social aspects were examined with the following questions: “If you are a believer, how much did you miss or do you miss participating in mass in the church (or in the worship service of your religious community) during the restrictions due to the pandemic?” and “If you are a believer and if you previously participated in other activities in the church, how much did you miss or do you miss that live contact with the parish community?”, as well as the statement “We prayed more as a family”. In all three cases, it was possible to answer on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely), with a selection category referring to those who did not participate in such activities even before the pandemic.

The impact of the pandemic on social relationships was examined with the question: “How much has the coronavirus pandemic worsened your relationships with family members?“ and the statement “I have become closer to my family”, which could be answered from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely). In addition to family relationships, the impact on peer relationships was also examined with the question “How has the pandemic affected your relationships with your peers?“ with possible answers on a scale from 1 (it made them worse), to 3 (it didn’t change them) and 5 (it improved them a lot).

Emotional consequences were identified through two variables: “To what extent have you experienced or are experiencing the following conditions and feelings due to the coronavirus pandemic?”, with separate answers for “fear” and “concern” on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely).

Consequences for personal growth were examined through negative and positive aspects. The possible negative impact of the pandemic on learning was examined with the question “How much has the coronavirus pandemic worsened your learning?”, with possible answers from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely). Possible positive consequences were examined through three variables, i.e. the question “Did the pandemic have a positive impact on your life?”, with the following statements: “I became more independent”, “I became more creative” and “More than before, I cared about the well-being of others and I think that I became a better person”. Each could be answered on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Extremely).

4 Results and discussion

4.1 Prominence of the examined consequences of the pandemic

If the principle (theoretical) range of scales is taken into account, according to the recorded average answers shown in Table 2, it can be stated that the pandemic did not leave any serious negative consequences in the surveyed sample. On the contrary, they are mostly moderately positive when it comes to the variables included in the research.

As stated in the description of the realized sample, religion is on average moderately to quite important to the examined adolescents (M = 3.74). Expressed in percentages, 4.3% of those who took part in the research considered themselves atheists, 31.4% stated that their religion was little to moderately important, and 64.3% that it was quite or extremely important to them.

Although the participants were recruited by religious education teachers, the sample is not particularly biased towards religiosity. For example, if it is compared with the research on the religiosity of Zagreb adolescents conducted in 2016 on a sample of 1111 high school students, 10.4% of Zagreb adolescents consider themselves non-religious (Barić, 2019), while for 52.2% of them religion is very important or the most important (Tamarut, 2019). Although this is around 10% more than in our sample, we should take into account that the population of larger cities such as Zagreb, is less religious. In addition, the research conducted as part of the international research project European Values Study in 2018 shows that in the general population in Croatia, the percentage of convinced atheists is 5.4%, non-religious people are 9.5%, and religious people are 78.3% (Nikodem & Zrinščak, 2019). This is around 10% more than in our sample, but in this case it should be taken into account that the older population is more religious. Therefore, the share in our sample is within the range in which it should actually be expected, if the aforementioned studies are accepted as reference.

When it comes to intrinsic faith, during the pandemic the attitude towards God among the surveyed adolescents became, on average, moderately more personal (M = 2.86).

When it comes to the consequences for religious activities in the live social environment, believers moderately missed worship (M = 3.27), as well as activities in the parish for those who participated in them even before the pandemic (M = 2.94). During the pandemic, the frequency of common prayer in the family also increased to a small to moderate extent (M = 2.42).

The pandemic generally did not leave significant negative consequences for either family or peer relationships. It worsened family relationships only slightly (not at all in 88% of cases, an average of 1.48 on a scale from 1 to 5). On the contrary, it stimulated cohesion significantly more, on average 3.17 on the scale of the same range (t = 49.521; p = 0.000). The significant role of family support in the pandemic was also shown by research among adolescents in Moscow, conducted at the same time, which states that adolescents were able to achieve positive emotional experiences and fulfill the need for communication in the family circle (Egorov & Mart’yanova, 2021). According to our research and if you look at the average (M = 2.91), the pandemic slightly worsened relations with peers. Expressed in percentages, 60% of adolescents stated that their relationships with peers have not changed; 24% of them state that they have been impaired (20% somewhat, 4% strongly), and 15% that they have become better (11% somewhat, 4% strongly). The hierarchy of supporting roles of family and peers is also shown by the share of answers to the open question about who was their biggest support during the pandemic: family support was listed as the most important in 65% of cases, twice as much as relying on peers (in 33% of cases).

The pandemic, on average, elicited mild to moderate emotional reactions, to a greater extent concern and to a lesser extent fear (M concern = 2.79; M fear = 2.30; t = 17.075, p < 0.01).

In the end, the consequences for personal development were more positive than negative. Although, the difficult circumstances for teaching and the introduction of new forms of classes, according to the students' self-perception, decreased the quality of learning to some extent (M = 2.51), the surveyed adolescents became more creative (M = 2.63), more independent (M = 2.70) and more moral (M = 3.26, if increased social sensitivity is accepted as an indicator of morality). Examination of the statistical significance of the differences shows that the consequences were expressed differently (RM ANOVA = 75.987, p < 0.01). Only creativity increased to the same degree as the deterioration of learning (t = 1.833, p > 0.05); improvement in independence exceeded this deterioration, on average (t = 3.082, p < 0.01), while social sensitivity (morality) increased more than anything else (post-hoc t-tests range from 12.180 to 13.198 and respectively are significant with p < 0.01).

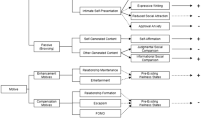

4.2 Consequences of the pandemic and religiosity

The correlations in Table 3 show the relationship between religiosity and the described (social, emotional and developmental) consequences of the pandemic. Both aspects of religiosity were taken into account: the importance of religion in general (which also includes a social component) and a more personal relationship with God (increased intrinsicness), caused by or prompted by the pandemic.

The correlation between these variables is moderately high (r = 0.601, p < 0.01), and the significance of the differences in the connection of each of those two aspects of religiosity with the included consequences of the pandemic was verified by transformation into Fisher’s z-values (last column in the table).

As expected, practicing faith in live social environment was missed by the more religious, both those for whom faith is more important in life in general, and those for whom, in addition, it has grown into a more personal relationship with God. But checking the statistical significance of the differences between the correlation coefficients shows that the live social environment for practicing religion was missed significantly more by those for whom religion is generally more important in their lives than for those for whom it became more personal during the pandemic (both in relation to worship services and parish activities). But families of the more religious adolescents began to pray together more often during the pandemic, which especially applies to those whose faith has grown into a more personal relationship with God.

It has already been stated that in this sample of adolescents, family relations are almost undisturbed. The negative correlation between the importance of religion and the deterioration of relationships shows that in the families of adolescents for whom religion is more important in their lives, these relationships have been even less threatened. On the contrary, cohesion has increased more in more religious families: this also applies to the families of adolescents for whom religion is important, and especially to the families of those for whom, in addition, it has become more intrinsic. Furthermore, in families whose members began to pray together more often, togetherness also increased (r = 0.408, p < 0.01). In contrast to the positive role of religion in preserving or improving the quality of family relationships during the pandemic, religion did not prove to be relevant for relationships with peers.

Correlations between religiosity and negative emotions caused by the pandemic show that more religious adolescents are simultaneously more emotionally sensitive, especially those whose relationship with God has become more personal. But despite the increased difficulty of emotional coping with the challenges of the pandemic and the possible negative impact of fear and anxiety on daily functioning and the fulfilment of obligations, the more religious adolescents did not give in. On the contrary, on average, more than those who are less religious, they used difficulties as an opportunity for personal growth.

Adolescents whose relationship with God increased in quality made the most progress in personal growth. Their quality of learning decreased somewhat less than those for whom religion is not so important, and in addition, they became more independent, more creative and, especially, more socially sensitive (more moral). Except when it comes to learning, they have also made more progress than adolescents for whom religion is important, but has not become so personal. The former have become somewhat more independent and, more than that, more socially sensitive than adolescents for whom religion is less important.

Here the question can be raised whether religiosity is in itself a stimulus to personal growth or it is only due to a correlation with an increase in family cohesion. Namely, in addition to religiosity, the increased quality of family relationships was also associated with selected growth indicators: preserving the quality of learning (r = − 0.117, p < 0.01), greater independence (r = 0.267, p < 0.01), creativity (r = 0.249, p < 0.01) and social sensitivity (r = 0.438, p < 0.01).

To answer this question, the variables most associated with growth (increase in family cohesion and intrinsic faith), along with gender and age due to possible interactions, were included in the regression analysis to test their independent contributions (Table 4).

As the tests of the statistical significance of the regression coefficients show, for the preservation of the quality of learning, an increase in family cohesion is more relevant than a more personal relationship with God. But this effect, despite its statistical significance, is minimal (R2 = 0.019). When it comes to the growth of independence and creativity, the effects, although somewhat greater, are still absolutely small. But in both cases, the contributions of family cohesion and a more personal relationship with God are independent of each other: greater independence and creativity can be attributed to a certain extent to a better family climate (regardless of religiosity), as well as to the increase of the intrinsic faith (regardless of the quality of family relations). Clearly, in the case of a favorable combination of both, the overall effect is greater than the individual effects. Similar findings about the favorable influence of faith on resilience, especially in combination with other positive resources such as happiness, are confirmed by other research (Gang & Torres, 2022).

When it comes to the increase in social sensitivity (morality), the same applies, and in addition, the effects of the predictors are significantly more substantial (R2 = 0.288). In addition, unlike previous cases where gender and age were shown to play no role, this one shows that girls have become even more sensitive than boys, thanks to the known fact that they are otherwise more sensitive, either dispositionally or based on upbringing. Taking everything into account, it can be said that moral progress, in combination with family and more personal religious incentives (moral imperatives of faith), can be attributed to greater emotional sensitivity, without which there is no empathy.

Likewise, it can be said that moral progress is more substantial because it depends on a decision, emotionally and/or rationally motivated from within or specifically socialized from without. In contrast, progress in the other examined areas is not possible only on the basis of a decision or choice, since it also implies relatively greater cognitive dispositions that do not depend on personal choice. In any case, religion, along with family, played a positive role: more religious adolescents, and especially those whose relationship with God became more personal, proved to be more self-responsible (despite the greater emotional load, they did not regress, even if they did not progress to a great extent either), as well as responsible towards others (thanks, among other things, to greater emotional sensitivity).

4.3 Conclusion

The research we conducted from December 2020 to February 2021 among adolescents in Croatia (N = 857) confirmed all three hypotheses: (1) that, influenced by the pandemic, the faith of adolescents became more personal; (2) that religiosity contributed to greater emotional and social resilience of adolescents; and (3) that religiosity encouraged personal maturation and personal growth in adolescents. In the families of more religious adolescents, and especially those whose faith has become more personal, they began to pray together more often during the pandemic. This further encouraged family cohesion, which proved to be important for adolescents for whom faith is important in their lives, and even more so for those whose faith has become more intrinsic during the pandemic.

The connection between religiosity and emotional and social sensitivity as well as personal growth was also shown. Nevertheless, personal maturation, which is especially manifested through the growth of creativity and morality, is also connected with family cohesion as well as with the growth of intrinsic faith. According to our research, girls proved to be more socially sensitive, and this correlation is even greater in the case of more intense family and religious incentives for faith and personal growth. In further research, it would be worthwhile to examine both the relationship between religiosity and gender differences, as well as the cultural conditioning of the relationship between gender affiliation and personal religiosity. For example, research among adolescents in Hong Kong shows that personal religiosity (both intrinsic and extrinsic) has a greater positive effect on self-esteem and life satisfaction and more strongly encourages the search for meaning in life in boys than in girls (Li & Liu, 2021).

Finally, we want to point to some possible limitations of the research. The sample on which this research was conducted is more gender-biased (almost three-quarters are girls, 72.8%), which makes the generalization to the adolescent population as a whole questionable, at least when it comes to moral progress due to its direct connection with gender. In addition, the effect could be indirect, as it turned out that the girls in this sample are also more religious, both when it comes to the importance of religion (M girls = 3.79; M boys = 3.61; t = 2.292; p < 0.05), as well as a more personal relationship with God (M girls = 3.93; M boys = 2.70; t = 2.344; p < 0.05). Furthermore, it was more difficult for them emotionally to cope with the threats of the pandemic: they were more afraid (M girls = 2.41; M boys = 2.01; t = 5.398; p < 0.01) and were more worried (M girls = 2.93; M boys = 2.40; t = 6.768; p < 0.01).

It should also be taken into account that the trends indicating a positive influence of religiosity on the examined phenomena, although consistent and clear, are relatively mild (correlation and determination coefficients are mostly low). It is possible that in the general adolescent population (balanced by gender) they would fade further. Despite this, as it is a sample that represents a non-negligible part of the adolescent population (three quarters, if only the gender bias is taken into account), the recorded trends can be considered sufficiently relevant even in this quantitative sense, although they do not have to apply to the entire population.

Notes

After several consecutive smaller earthquakes, a much stronger one, magnitude 6.2 on the Richter scale, hit the area around Petrinja, on December 28, 2020.

In this paper, the terms "faith" and "religiosity" are used interchangeably as synonyms.

According to data available on the website of the Ministry of Science and Education (Ministarstvo znanosti i obrazovanja, 2022), Croatia has 926 primary and 442 secondary schools.

References

Antičević, V. (2021). Učinci pandemija na mentalno zdravlje. Društvena istraživanja, 30(2), 423–443.

Barić, D. (2019). Identitet adolescenata. In B. V. Mandarić, R. Razum, & D. Barić (Eds.), Religioznost zagrebačkih adolescenata. Katolički bogoslovni fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu & Kršćanska sadašnjost (pp. 19–38).

Beroš, V. (2020, March 11). Odluka o proglašenju epidemije bolesti COVID-19 uzrokovana virusom SARS-CoV-2. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://zdravlje.gov.hr/UserDocsImages//2020%20CORONAVIRUS//ODLUKA%20O%20PROGLA%C5%A0ENJU%20EPIDEMIJE%20BOLESTI%20COVID-19.pdf

Cragun, R. T., & Speed, D. (2022). Religiosity and happiness: Much ado about nothing. In S. Sugirtharajah (Ed.), Religious and non-religious perspectives on happiness and wellbeing (pp. 167–191). Routledge.

Dieterich, V. J. (2012). Theologisieren mit Jugendlichen: Ein Programm. In V.-J. Dieterich (Ed.), Theologisieren mit Jugendlichen: Ein Programm für Schule und Kirche (pp. 31–50). Calwer.

Dilmaghani, M. (2018). Religiosity and subjective wellbeing in Canada. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(2), 629–647.

Dominick, W., & Taku, K. (2019). Cultural differences in the perception of personal growth among adolescents. Cross-Cultural Research, 53(4), 428–442.

Ebertz, M. (1998). Erosion der Gnadenanstalt: Zum Wandel der Sozialgestalt von Kirche. Knecht.

Egorov, I. V., & Mart’yanova, G. Y. (2021). Семья как ресурс социально-адаптивного поведения подростков в период пандемии: постановка проблемы [Family as a resource of socially adaptive behaviour of adolescents during the pandemic: Raising the question]. Vestnik Pravoslavnogo Sviato-Tikhonovskogo Gumanitarnogo Universiteta, 61(4), 11–25. https://periodical.pstgu.ru/ru/pdf/article/7554.

European Commission. (2022). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of young people: Policy responses in european countries. Publications Office of the European Union.

Fend, H. (2001). Entwicklungspsychologie des Jugendalters(2nd ed.). Leske & Budrich.

Filipović, A. T., & Rihtar, S. (2022). Utjecaj krize uzrokovane pandemijom koronavirusa na neke aspekte života, mentalnog zdravlja i vjere adolescenata. In J. Garmaz, & A. Šegula (Eds.), Probuditi kreativnost: Izazovi učenja i poučavanja u kontekstu pandemije i migracija: Zbornik radova / Inciting creativity: Learning and teaching challenges in the context of pandemic and migration: Conference proceedings. Katolički bogoslovni fakultet Sveučilište u Splitu (pp. 253–269).

Flammer, A., & Alsaker, F. D. (2002). Entwicklungspsychologie der Adoleszenz: Die Erschließung innerer und äußerer Welten im Jugendalter. Hans Huber.

Flynn, R., Riches, E., Reid, G., Rosenberg, S., & Niedzwiedz, C. (2020). Rapid review of the impact of COVID-19 on mental health. Public Health Scotland. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from: https://www.healthscotland.scot/media/3112/rapid-review-of-the-impact-of-covid-19-on-mental-health-july2020-english.pdf

Gang, G. C. A., & Torres, E. M. (2022). The Effect of Happiness and Religious Faith on Christian Youth’s Resiliency during the Covid-19 Pandemic. Psychological Applications and Trends. https://doi.org/10.36315/2022inpact085

Jiao, W. Y., Wang, L. N., Liu, J., Fang, S. F., Jiao, F. Y., Pettoello-Mantovani, M., & Somekh, E. (2020). Behavioral and emotional disorders in children during the COVID-19 epidemic. The Journal of Pediatrics, 221, 264–266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.03.013.

Jones, E. A. K., Mitra, A. K., & Bhuiyan. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on mental health in adolescents: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2470. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052470

Kilmer, R. P., Gil-Rivas, V., Griese, B., Hardy, S. J., Hafstad, G. S., & Alisic, E. (2014). Posttraumatic growth in children and youth: Clinical implications of an emerging research literature. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(5), 506–518.

Koenig, H. G., McCullough, M. E., & Larson, D. (2001). Handbook of Religion and Health. Oxford University Press.

Kratka povijest pandemije u Hrvatskoj (2022, March 20). Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://pandemijskirealizam.net/povijest-pandemije

Kuzman, M. (2009). Adolescencija, adolescenti i zaštita zdravlja / adolescence, adolescents and Healthcare. Medicus, 18(2), 155–172.

Li, A. Y. C., & Liu, J. K. K. (2021). Effects of intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity on well-being through meaning in life and its gender difference among adolescents in Hong Kong: A mediation study. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02006-w

Loewenthal, K. (2009). Religion, culture and mental health. Cambridge University Press.

Magson, N. R., Freeman, J. Y. A., Rapee, R. M., Richardson, C. E., Oar, E. L., & Fardouly, J. (2021). Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 50, 44–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9.

Ministarstvo unutarnjih poslova Republike Hrvatske, Ravnateljstvo civilne zaštite (2022). Epidemija koronavirusa u Republici Hrvatskoj. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://civilna-zastita.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/CIVILNA%20ZA%C5%A0TITA/PDF_ZA%20WEB/Bro%C5%A1ura-COVID2.pdf

Ministarstvo znanosti i obrazovanja (2022). Ustanove: Ustanove iz sustava. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://mzo.gov.hr/ustanove/103

Nikodem, K., & Zrinščak, S. (2019). Između distancirane crkvenosti i intenzivne osobne religioznosti: Religijske promjene u hrvatskom društvu od 1999. do 2018 godine. Društvena istraživanja, 28(3), 371–390.

Novak, M., Ferić, M., Kranželić, V., & Mihić, J. (2019). Konceptualni pristupi pozitivnom razvoju adolescenata. Ljetopis socijalnog rada, 26(2), 155–184.

Phillips, R., Connelly, V., & Burgess, M. (2021). Explaining the relationship between religiosity and increased wellbeing. Avoidance of identity threat as a key factor. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 42(2), 163–176.

Poljak, M., & Begić, D. (2016). Anksiozni poremećaji u djece i adolescenata. Socijalna psihijatrija, 44(4), 310–329.

Pope, F. (2020, March 27). Urbi et Orbi. Retrieved October 24, 2022, from https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/messages/urbi/documents/papa-francesco_20200327_urbi-et-orbi-epidemia.html

Questionnaire (2020, December 20) Retrieved October 24, 2022, from https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLSdSAEDp4AlMNzK4U5ANQHYX84ybVmeuUN2flDT-ZaM2HU8hw/viewform1

Riegel, U., & Faix, T. (2015). Jugendtheologie: Grundzüge und grundlegende Kontroversen einer relativ jungen religionspädagogischen Programmatik. In T. Faix, U. Riegel, & T. Künkler (Eds), Theologien von Jugendlichen: Empirische erkundungen zu theologisch relevanten Konstruktionen Jugendlicher. Lit (pp. 9–33).

Rukavina, M., & Nikčević-Milković, A. (2016). Adolescenti i školski stres. Acta Iadertina, 13(2), 159–169.

Seizmološka služba pri geofizičkom odsjeku PMF-a (2020, March 22). Dva snažna potresa u Zagrebu. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://www.pmf.unizg.hr/geof/seizmoloska_sluzba/izvjesca_o_potresima?@=1lppn#news_45225

Singh, S., Roy, D., Sinha, K., Parveen, S., Sharma, G., & Joshi, G. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: A narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113429. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429. Advance online publication.

Streib, H., & Gennerich, C. (2011). Jugend und Religion. Bestandsaufnahmen, Analysen und Fallstudien zur Religiosität Jugendlicher. Juventa

Tamarut, A. (2019). Vjerovati znači s Bogom prijateljevati. In B. V. Mandarić, R. Razum, & D. Barić (Eds.), Religioznost zagrebačkih adolescenata. Katolički bogoslovni fakultet Sveučilišta u Zagrebu & Kršćanska sadašnjost (pp. 83–106).

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9(3), 455–471.

Torales, J., O’Higgins, M., Castaldelli-Maia, J. M., & Ventriglio, A. (2020). The outbreak of COVID-19 coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(4), 317–320.

Torralba, J., Oviedo, L., & Canteras, M. (2021). Religious coping in adolescents: New evidence and relevance. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00797-8.

UNICEF (2021). Regional Brief: Europe: The State of the world’s children 2021: On my mind: Promoting, protecting and caring for children’s mental haelth. Retrieved October 12, 2022, from https://www.unicef.org/croatia/media/8446/file/Stanje_djece_-_Europa.pdf

Unterrainer, H. F., Lewis, A. J., & Fink, A. (2014). Religious/spiritual well-being, personality and mental health: A review of results and conceptual issues. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(2), 382–392.

Vlada Republike Hrvatske (2022). Aktualne mjere. Retrieved October 5, 2022, from https://www.koronavirus.hr/aktualne-mjere/1010

World Health Organization (2020). WHO Director-General’s opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19–11 March 2020 Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020

Funding

No funds, grants, or other support was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Concept and theory: ATF; Material preparation and data collection: both authors; Statistical data analysis and interpretation: SR. The first draft of the manuscript was written by ATF. Both authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Catholic Faculty of Theology of the University of Zagreb (No. 251-82/01-20-495, 18 December 2020). All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual study participants. For participants who were under 18 of age, parental consents were also collected beforehand.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Filipović, A.T., Rihtar, S. Religiosity as a factor of social-emotional resilience and personal growth during the COVID-19 pandemic in Croatian adolescents. j. relig. educ. 71, 123–137 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-023-00197-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40839-023-00197-x