Abstract

We examine whether Audit Fee Regulation (AFR) enhances auditors’ bargaining power in setting audit fees, consequently leading to superior quality audit services using the Iranian audit environment. We posit two hypotheses of “symbolic” and “substance” compliance. We find that neither audit fees nor audit quality has increased in the post-AFR era, supporting the symbolic hypothesis. The results are robust to several sensitivity tests, including difference-in-difference analysis. Contrary to the regulator’s expectation, our findings suggest that arbitrarily stimulating suppliers’ incentives without considering the priority and importance of demand-side incentives in a compliance-driven audit market and the flexibility to bypass the regulation result in symbolic (de jure) compliance with the regulation. We provide policy, practice, and research implications by suggesting that positive intended consequences of regulations in a compliance-driven audit market can be achieved when the regulation is robust with less latitude for discretion symbolic compliance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

Auditing Standard No. 2 (AS 2) that requires auditors to audit a client’s internal control structure deemed to be an example of costly overregulation (Eierle et al. 2021).

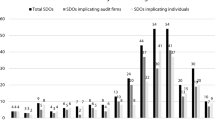

Descriptive statistics provided by MohammadRezaei et al. (2018) show that type II audit failure (1 if the audit opinion is unqualified in the prior year but financial statements were restated in the current year to correct the last year errors, and 0 otherwise) in the entire sample is 29%. If this error is calculated for observations with an unqualified opinion, the type II audit error will be 67%. This evidence indicates the supply of low-quality audit services in Iran. This empirical evidence is discussed in details by MohammadRezaei et al. (2015) based on anecdotal evidence.

Although in first look, it seems that no failure exists in the Iranian audit market since there is no incentives to provide differentiated audit services and it is a low-cost compliance process. However, according to DeFond and Zhang (2014), the intended goal of the audit market is the same as the ultimate goal of the auditing, to provide reasonable assurance regarding the quality of the information reported in the financial statements. Low audit fees are more likely to lead to budget pressures and reduced audit efforts, and ultimately reduced audit quality and low-quality financial reporting (Houston 1999). Therefore, audit failure can lead to capital market failure, for instance the scandal of Enron.

Langli and Svanstrom (2014) highlight the lack of sufficient evidence about the audit markets as same as Iranian audit market. In this line, Bianchi et al. (2019) argue that there is little evidence about the small audit firms market where their clients are also small and medium private firms.

For instance, the main purpose of mandatory auditor rotation is to prevent auditors from potential independence compromising and ultimately to maintain the quality of audit services.

That is, other players like minority shareholders, potential investors, government and other stakeholders is likely to have incentives for quality auditing. However, the controlling shareholders with no information asymmetry have voting and control rights in relation to auditor choosing and audit fees.

In case the audit firms and certified public accountants do not comply with AFR, in addition to affecting the class rating of certified public accountants and audit firms, they are subject to penalties such as reprimands, suspension of new contracts and suspensions that will be more than a year to five years.

Salehi et al. (2017) find that international economic sanctions in 2010 resulted in lower audit fees (fee pressure) in Iranian audit market.

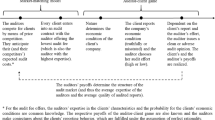

General knowledge is tied to the auditor’s work experience and is positively associated with the ability to detect material misstatements. Specialized knowledge comes from prior experience of auditing companies in the same industry (Langli and Svanström 2021). If auditors are allowed to charge a premium, they will invest in industry specialization (Casterella et al. 2004). Client-specific knowledge is the knowledge of the client’s accounting system and internal control structure, which gives auditors comparative advantages in detecting errors (Langli and Svanström 2014).

Salehi et al. (2017) provide evidence that fee pressure due to international economic sanctions imposed on Iran in 2010 results in lower audit quality.

Although this regulation was enforced near the end of the fiscal year 2015, we do not consider this year a transition period, since audit fees in Iran are established before the engagement begins and before the end of the fiscal year, which is the 20th of March for most firms. Additional sensitivity tests are performed to examine the impact of this practice on the results. Moreover, to address possible concerns about not treating 2015 as a transition period, main tests are repeated without 2015 observations in the section on sensitivity tests.

A significant percentage of listed firms disclose audit fees in the explanatory notes to financial statements (selling, general and administrative expense (SG&A) notes).

Additional sensitivity tests are performed to control for selection bias resulting from the choice of listed firms to separately disclose audit fees.

“In the Iranian audit market, AudFail seems to be a more accurate indicator than restatement of financial statements. This is the case because the ratio of audit report modification is high in Iran (MohammadRezaei et al. 2016). In this type of situation, if we use the restatements of financial statements in the next year as a measure of audit quality, this would result in misleading inferences” (MohammadRezaei et al. 2018: 300).

In the Iranian audit market, it is common practice to determine the audit fee before starting the engagement based on the auditor’s bargaining power over the client (MohammadRezaei and Faraji 2019). As such, the auditor may consider client characteristics (e.g., type of report, number of audit staff, client size, client business risk) that are available when determining the audit fee. Thus, there may be concerns that current audit fee is more closely related to last year’s client characteristics and audit report. To address these concerns, Model (1) is also estimated with lagged independent variables. Untabulated results are consistent with the main findings in Table 3 and indicate that AFR has not leads to an increase in audit fees.

We also estimated all models by controlling year and firm fixed effects and the untabulated results support the main findings in Tables 3 and 4. This suggests that our findings are robust to alternative approaches to model estimation.

20 Following MohammadRezaei et al. (2016) and Golmohammadi Shuraki et al. (2020), the number of audit qualification paragraphs (AQPN) before the audit opinion and absolute discretionary accruals in Dechow and Dichev’s (2002) model (EM-DD) are used as alternative measures of audit quality. The untabulated results are indicative of symbolic compliance with AFR. The estimated coefficients for AFR are (β = -0.487, P < 0.01) and (β = -0.012, P > 0.10) when dependent variables are AQPN and EM-DD, respectively. Such findings are consistent with main findings in Table 4 and indicate that our findings are not sensitive about different measures of audit quality.

MohammadRezaei and Faraji (2019) state that IACPA only makes public available the sentences that result in restrictions on the activities of audit firms and partners, and does not make public available the sentences that reduce only the quality control scores.

Iran Audit Organization (IAO), as state audit entity, as a counterpart of IACPA’s licensed private audit firms possess about %20 of Iranian audit market share. IAO is independent from IACPA and AFR is not effective for the state auditor. Although, in first look, such situation seems to be a good laboratory to employ a difference-in-differences analysis, prior studies demonstrate that IAO operate in an oligopolistic market in relation to auditing of state and semi-state-owned firms (Bagherpour et al. 2014: MohammadRezaei et al. 2016). In other words, determinants of audit fee model are likely to be different for the two auditors because private audit firms in their highly competitive audit market are price-takers, however IAO has a higher bargaining power in its oligopolistic market (MohammadRezaei et al. 2015). In addition, IAO is exempted from mandatory auditor rotation. Hence, auditor switching does not happened for the IAO. Hence, we believe that observations audited by IAO are less likely to be employed as a control group to apply a difference-in-differences analysis. Nonetheless, we conduct a difference-in-differences analysis in witch observations are classified in the treatment sample if the audit firm(s) of the company are all subject to comply with AFR (private audit firms as the members of IACPA). Observations are classified in the control sample if the audit firm of the company has not been subject to comply with AFR (IAO). Hence, \(\mathrm{PvtAud}\) takes a value of 1 for the treatment sample and 0 for control sample. The interaction of \(\mathrm{PvtAud}*\mathrm{AFR}\) is our variable of interest in Models (1), (2) and (3). Untabulated results reveal that \(\mathrm{PvtAud}*\mathrm{AFR}\) in Models (1), (2) and (3) has no positive relation with audit fees and audit quality. Such findings support the main findings in accordance with symbolic compliance and reveal that our main findings are robust to different specifications.

In Iran, according to the sample audit contracts issued by IACPA, the client must pay 50% of the audit fee when signing the contract as an advance payment, and the remaining 50% must be paid at the time of issuing the audit report. That is, as a common practice, audit firms try to receive audit fee before submitting an audit report to their client firms.

References

Afsharipour, A. 2009. Corporate governance convergence: lessons from the Indian experience, Northwestern journal of international law and business 29, [Internet document] (Social Science Research Network) [created 29 June 2009], available from SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1413859.

Amani, A., & Davani, H. 2010. The services, fees and ranking of auditors. Donya-e-Eqtesad, 20 January, 18–19 (In Persian).

Anthony, J.H., and K. Ramesh. 1992. Association between accounting performance measures and stock prices: A test of the life cycle hypothesis. Journal of Accounting and Economics 15: 203–227.

Averhals L., Caneghem T. V., & Willekens M 2020 Mandatory audit fee disclosure and price competition in the private client segment of the Belgian audit market. Journal of International Accounting Auditing and Taxation, 40: 10037

Azami, Z., and T. Salehi. 2017. The relationship between audit report delay and investment opportunities. Eurasian Business Review 7: 437–449.

Bagherpour, M., G. Monroe, and G. Shailer. 2014. Government and managerial influence on auditor switching under partial privatization. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 33 (4): 372–390.

Ball, R. 2006. International financial reporting standards (IFRS): Pros and cons for investors. Accounting and Business Research 36: 5–27.

Barnes, P., and M.A. Renart. 2013. Auditor independence and auditor bargaining power: Some Spanish evidence concerning audit error in the going concern decision. International Journal of Auditing 17 (3): 265–287.

Barth, M.E., W.R. Landsman, M. Lang, and C. Williams. 2012. Are IFRS-based and USGAAP-based accounting amounts comparable? Journal of Accounting and Economics 54 (1): 68–93.

Bedard, J.C., D. Falsetta, G. Krishnamoorthy, and T.C. Omer. 2010. Voluntary disclosure of auditor-provided tax service fees. The Journal of the American Taxation Association 32 (1): 59–77.

Bianchi, P., N. Carrera, and M. Trombetta. 2019. The Effects of auditor social and human capital on auditor compensation: Evidence from the Italian small audit firm market. European Accounting Review 29 (4): 693–721.

Bierstaker, J.L., and A. Wright. 2001. The effects of fee pressure and partner pressure on audit planning decision. Advances in Accounting 18 (1): 25–46.

Blankley, A.I., D.N. Hurtt, and J.E. MacGregor. 2012. Abnormal audit fees and restatements. Auditing A Journal of Practice & Theory 31 (1): 79–96.

Bozorg Asl, M. 2010. The audit quality and fees. Donya-e-Eqtesad, March 5, p. 17 (in Persian), available at: www.donya-e-eqtesad.com.

Casterella, J.R., J.R. Francis, B.L. Lewis, and P.L. Walker. 2004. Auditor industry specialization client bargaining power and audit pricing. Auditing A Journal of Practice and Theory 23 (1): 123–140.

Chan, K.H., K.Z. Lin, and P.L. Mo. 2006. A political-economic analysis of auditor reporting and auditor switches. Review of Accounting Studies 11: 21–48.

Chaney, P.K., D.C. Jeter, and P.E. Shaw. 2003. The impact on the market for audit services of aggressive competition by auditors. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 22: 487–516.

Chen, C.J.P., X. Su, and X. Wu. 2007. Market competitiveness and Big 5 pricing: Evidence from China’s binary market. The International Journal of Accounting 42 (1): 1–24.

Cho, M., S.Y. Kwon, and G.V. Krishnan. 2021. Audit fee lowballing: Determinants, recovery, and future audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 40 (4): 106787.

Cook, E., and T. Kelley. 1988. Auditor stress and time budgets. CPA Journal 57: 83–86.

Coram, P., J. Ng, and D.R. Woodliff. 2004. The effect of risk of misstatement on the propensity to commit reduced audit quality acts under time budget pressure. Auditing A Journal of Practice & Theory 23 (2): 161–169.

Craswell, A., and J. Francis. 1999. Pricing initial audit engagements: A test of competing theories. The Accounting Review 14 (2): 201–215.

Cunningham, L.M., C. Li, S.E. Stein, and N.S. Wright. 2019. What’s in a name? Initial evidence of U.S. audit partner identification using difference-in-differences analyses. The Accounting Review 94 (5): 139–163.

Danaifar, H., A. Azar, and A. Salehi. 2009. Lawlessness in Iran: explaining the role of political, economic, legal, managerial and socio-cultural factors. Journal of Research Police Science 11 (3): 7–65.

DeAngelo, L.E. 1981. Auditor size and audit quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics 3 (3): 183–199.

Dechow, P., and I. Dichev. 2002. The quality of accruals and earnings: The role of accrual estimation errors. The Accounting Review 77: 35–59.

DeFond, M., and J. Zhang. 2014. A review of archival auditing research. Journal of Accounting and Economics 58 (2–3): 275–326.

DeFond, M.L., T.J. Wong, and S.H. Li. 2000. The impact of improved auditor independence on audit market concentration in China. Journal of Accounting and Economics 28: 269–305.

Ding, Y., H. Zhang, and J. Zhang. 2007. Private vs. state ownership and earnings management: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Corporate Governance: An International Review 15: 223–238.

Dunn, K., M. Kohlbeck, and B.W. Mayhew. 2011. The impact of the Big 4 consolidation on audit market share equality. Auditing A Journal of Practice 30 (1): 49–73.

Eierle, B., S. Hartlieb, D. Hay, L. Niemi, and H. Ojala. 2021. External environment and the pricing of audit services: A systematic review of archival literature. Auditing A Journal of Practice and Theory, Accepted Manuscript,. https://doi.org/10.2308/AJPT-2019-510.

Elder, R.J., and A. Yebba. 2020. The introduction of state regulation and auditor retendering in school districts: Local audit market structure, audit pricing, and internal controls reporting. Auditing A Journal of Practice & Theory 39 (2): 81–115.

Eshleman, J.D., and B.P. Lawson. 2017. Audit market structure and audit pricing. Accounting Horizons 31 (1): 57–81.

Ettredge, M., E.E. Fuerherm, and C. Li. 2014. Fee pressure and audit quality. Accounting, Organizations and Society 39 (4): 247–263.

Faraji, O., M. Kashanipour, F. MohammadRezaei, K. Ahmed, and N. Vatanparast. 2020. Political connections, political cycles and stock returns: Evidence from Iran. Emerging Markets Review 45: 100766.

Faraji, O., F. MohammadRezaei, H. Yazdifar, K. Ahmed, and Y. Najafi Gadikelaei. 2022. Audit qualification paragraphs and audit report lag: Evidence from Iran. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting, Accepted Manuscript,. https://doi.org/10.1080/02102412.2022.2086731.

Ferguson, A., P. Lam, and N. Ma. 2019. Further evidence on mandatory partner rotation and audit pricing: A supply-side perspective. Accounting & Finance 59: 1055–1100.

Field, A. 2013. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics. Sage.

Francis, J.R. 2004. What do we know about accounting quality? The British Accounting Review 36 (4): 345–368.

Francis, J.R., P.N. Michas, and S.E. Seavey. 2013. Does audit market concentration harm the quality of audited earnings? Evidence from audit markets in 42 countries. Contemporary Accounting Research 30 (1): 325–355.

Ghosh, A., and S. Lustgarten. 2006. Pricing of initial audit engagements by large and small audit firms. Contemporary Accounting Research 23 (2): 333–368.

Gilson, R.J. 2001. Globalizing corporate governance: Convergence in form or function. The American Journal of Comparative Law 49: 329–357.

Golmohammadi Shuraki, M., Pourheidari, O. and Azizkhani, M. 2020. Accounting comparability, financial reporting quality and audit opinions: evidence from Iran. Asian Review of Accounting, ahead-of-print No. ahead-of-print. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARA-06-2020-0087.

Hay, D., and D. Jeter. 2011. The pricing of industry specialization by auditors in New Zealand. Accounting and Business Research 41 (2): 171–195.

Hay, D.C., W.R. Knechel, and N. Wong. 2006. Audit fees: A meta-analysis of the effect of supply and demand attributes. Contemporary Accounting Research 23 (1): 141–191.

Houston, R.W. 1999. The effect of fee pressure and client risk on audit seniors’ time budget decisions. Auditing A Journal of Practice and Theory 18 (2): 70–86.

Hovannisian Far, G. 2010. Forced auditing: Its quality and fees. Donya-e-Eqtesad, February 26, p. 12 (in Persian).

Huang, H., K. Raghunandan, and D. Rama. 2009. Audit fees for initial audit engagements before and after SOX. Auditing A Journal of Practice & Theory 28 (1): 171–190.

Huang, T.-C., H. Chang, and J.-R. Chiou. 2016. Audit market concentration, audit fees, and audit quality: Evidence from China. Auditing A Journal of Practice and Theory 35 (2): 121–145.

Ireland, J.C., and C.S. Lennox. 2002. The large audit firm fee premium: A case of selectivity bias? Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Finance 17 (1): 73–91.

Jain, P.K., and Z. Rezaee. 2006. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 and capital-market behavior: Early evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research 23 (3): 629–654.

Jing, Z. 2019. Two essays on auditing in China. PhD Dissertation. The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Johnson, L.E., S.P. Davies, and R.J. Freeman. 2002. The effect of seasonal variations in auditor workload on local government audit fees and audit delay. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 21: 395–422.

Kasai, N., & T. Takada, 2012. How do regulation and deregulation on audit fees influence audit quality?: Empirical Evidence from Japan. Working paper

Kenchel, W.R. 2016. Audit quality and regulation. International Journal of Auditing 20 (3): 215–223.

Khanna, T., J. Kogan, and K. Palepu. 2006. Globalization and similarities in corporate governance: A cross-country analysis. The Review of Economics and Statistics 88: 69–90.

Killough, L., and C. Ho. 1985. The race is on: Has competition changed the accounting profession? The National Public Accountants 30 (12): 20–24.

Kothari, S., A. Leone, and C. Wasley. 2005. Performance matched discretionary accrual measures. Journal of Accounting and Economics 39: 163–197.

Krishnan, G., and J. Zhang. 2019. Do investors perceive a change in audit quality following the rotation of the engagement partner? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 38 (2): 146–168.

Langli, J.C., and T. Svanström. 2014. Audits of private companies. In The Routledge Companion to Auditing, ed. D. Hay, W.R. Knechel, and M. Willekens. New York: Routledge.

Lennox, C.S. 1999. Non-audit fees, disclosure and audit quality. The European Accounting Review 8: 239–252.

Leuz, C. 2006. Cross listing, bonding and firms’ reporting incentives: A discussion of Lang, Raedy and Wilson. Journal of Accounting and Economics 42 (1): 285–299.

Mali, D., and H. Lim. 2021. Can audit effort (hours) reduce a firm’s cost of capital? Evidence from South Korea. Accounting Forum 45 (2): 171–199.

Moayedi, V., and M. Aminfard. 2012. Iran’s post-war financial system. International Journal of Islamic Middle Eastern Financing and Management 5: 264–281.

MohammadRezaei, F., and O. Faraji. 2019. The dilemma of audit quality measuring in archival studies: Critiques and suggestions for Iran’s research setting. Journal of Accounting and Auditing Review 26 (1): 87–122 ((In Persian)).

MohammadRezaei, F., and N. Mohd-Saleh. 2017. Auditor switching and audit fee discounting: The Iranian experience. Asian Review of Accounting 25 (3): 335–360.

MohammadRezaei, F., N. Mohd-Saleh, and M.J. Ali. 2015. Increased competition in an unfavourable audit market following audit privatisation: The Iranian experience. Asian Journal of Business and Accounting 8 (1): 115–149.

MohammadRezaei, F., N. Mohd-Saleh, R. Jaffar, and M.S. Sabri. 2016. The effects of audit market liberalisation and auditor type on audit opinions: The Iranian experience. International Journal of Auditing 20 (1): 87–100.

MohammadRezaei, F., N. Mohd-Saleh, and K. Ahmed. 2018. Audit firm ranking, audit quality and audit fees: Examining conflicting price discrimination views. The International Journal of Accounting 53 (4): 295–313.

MohammadRezaei, F., O. Faraji, and Z. Heidary. 2021. Audit partner quality, audit opinions and restatements: Evidence from Iran. International Journal of Disclosure and Governance 18 (2): 106–119.

Moore, D., P.E. Tetlock, L. Tanlu, and M. Bazerman. 2006. Conflicts of interest and the case of auditor independence: Moral seduction and strategic issue cycling. Academy of Management Review 31 (1): 10–29.

Niemi, L. 2004. Auditor size and audit pricing: Evidence from small audit firms. European Accounting Review 13 (3): 541–560.

Otley, D.T., and B.J. Pierce. 1996. Auditor time budget pressure: Consequences and antecedents. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 9 (1): 31–58.

Palmrose, Z. 1986. Audit fees and auditor size: Further evidence. Journal of Accounting Research 24: 405–411.

Petersen, M.A. 2009. Estimating standard errors in finance panel data sets: Comparing approaches. Review of Financial Studies 22 (1): 435–480.

Raghunathan, B. 1991. Premature signing-off of audit procedures: An analysis. Accounting Horizons 5 (2): 71–79.

Rodriguez-Perez, G., and S.V. Hemmen. 2010. Debt, diversification and earnings management. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 29: 138–159.

Roudaki, J. 2008. Accounting profession and evolution of standard setting in Iran. Journal of Accounting, Business & Management 15: 33–52.

Salehi, M., A. Jafarzadeh, and Z. Nourbakhshhosseiny. 2017. The effect of audit fees pressure on audit quality during the sanctions in Iran. International Journal of Law and Management 59 (1): 66–81.

Simon, D., and J. Francis. 1988. The effects of auditor change on audit fees: Test of price cutting and price recovery. The Accounting Review 63 (2): 255–269.

Simunic, D.A. 2014. The market for audit services. In The Routledge Companion to Auditing, ed. D. Hay, W.R. Knechel, and M. Willekens. New York: Routledge.

Soltes, E. 2014. Incorporating field data into archival research. Journal of Accounting Research 52 (2): 521–540.

Teoh, S.H., I. Welch, and T.J. Wong. 1998. Earnings management and the long run market performance of initial public offerings. Journal of Finance 53: 1935–1974.

Wong, R.M.K., M.A. Firth, and A.W.Y. Lo. 2018. The impact of litigation risk on the association between audit quality and auditor size: Evidence from China. Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting 29 (3): 280–311.

Xie, Z., C. Cai, and J. Ye. 2010. Abnormal audit fees and audit opinion – Further evidence from China’s capital market. China Journal of Accounting Research 3: 51–70.

Yaacob, N.M., and A. Che-Ahmad. 2012. Audit fees after IFRS adoption: Evidence from Malaysia. Eurasian Business Review 2: 31–46.

Zeghal, D., S. Chtourou, and Y.M. Sellami. 2011. An analysis of the effect of mandatory adoption of IAS/IFRS on earnings management. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 20 (1): 61–72.

Zhang, R., R.M.K. Wong, G. Tian, and M.M. Fonseka. 2021. Positive spillover effect and audit quality: A study of cancelling China’s dual audit system. Accounting & Finance. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12563.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support provided by the University of Memphis. We thank the participants at the 2021 American Accounting Association Annual Virtual Meeting for their helpful comments and suggestions. Fakhroddin MohammadRezaei is an assistant professor in accounting. Some of his papers have been published in international peer-reviewed journals such as Accounting & Finance, International Journal of Accounting, International Journal of Auditing and Emerging Markets Review. His research area includes auditing and financial reporting quality. Omid Faraji is an assistant professor in accounting. His manuscripts are newly accepted by some peer-reviewed international journals including Emerging Markets Review and Sustainability Accounting and Management Policy Journal. His research area includes auditing and financial reporting quality. Zabihollah Rezaee is the Thompson-Hill Chair of Excellence and Professor of Accountancy at the University of Memphis and has served a two-year term on the Standing Advisory Group (SAG) of the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB). Dr. Rezaee holds ten certifications, including Certified Public Accountant (CPA), Certified Fraud Examiner (CFE), Certified Management Accountant (CMA), Certified Internal Auditor (CIA), Certified Government Financial Manager (CGFM), Certified Sarbanes-Oxley Professional (CSOXP), Certified Corporate Governance Professional (CGOVP), Certified Governance Risk Compliance Professional (CGRCP), Chartered Global Management Accountant (CGMA) and Certified Risk Management Assurance (CRMA). He is currently serving as the 2012-2014 secretary of the Forensic & Investigative Accounting (FIA) Section of the AAA. Reza Gholami-Jamkarani is an associate professor in accounting. His manuscripts are under review by some peer-reviewed international journals. His research era is financial reporting quality. Mehdi Yari is newly obtained Ph.D. in accounting.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or non-profit sectors. Fakhroddin MohammadRezaei, Omid Faraji, Reza Gholami Jamkarani and Mehdi Yari declare that they have not received any Grants or financial supports from any Iranian institutions such as from Kharazmi University or the University of Tehran. On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author declares that Fakhroddin MohammadRezaeim Omid Faraji, Reza Gholami Jamkarani and Mehdi Yari are not employed by a government agency that has a primary function other than research and/or education. Fakhroddin MohammadRezaeim, Omid Faraji and Reza Gholami Jamkarani are just assistant professors in Kharazmi University, University of Tehran, and Islamic Azad University, and Mehdi Yari is a PhD candidate. These authors are not an official representative or on behalf of the government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix A: Evidence from interviews

To address the economic significance of our results and examine whether audit firms comply with AFR and whether that ‘symbolic compliance’ is actually used by Iranian auditors, we gathered additional evidence from two different sources. The first source was that we referred to the disciplinary sentences of the IACPA against its members and did not find sentences in relation to non-compliance with AFR.Footnote 23 In the second and most important step, we conducted short interviews with fifteen partners of audit firms. In these interviews, we ask three general questions; first, do audit firms comply with AFR? If not, we would ask the second and third questions, why do audit firms not comply with AFR? and how do audit firms bypass AFR without avoiding IACPA’s penalties?

Most of the interviewed partners state that they cannot comply substantially with AFR in the emerging audit market of Iran. Regarding the second question, the five main and frequent reasons for non-compliance with AFR include (1) intense competition in the audit market; (2) the lack of demand for quality audit services; (3) the poor economic situation of the country; (4) less precise counterparts’ quality control; and (5) significant available rooms in AFR. Furthermore, in the highly competitive audit market, if audit firms comply with AFR in determining their audit fees, there would be a high probability of losing clients. For instance, one of the partners states the following:

“In a market where client firms are maintained or transferred between the audit firms through intermediaries, by paying commissions to them, all the efforts of the audit firms are focused on maintaining their clients and there is competition among the audit firms for paying a higher percentage of commissions to the intermediaries.”

In addition, since in the Iranian audit market, the main purpose of the client firms is to recruit the auditor to comply with legal requirements, there is less incentive to demand quality audit services. Therefore, client firms prefer to perform this requirement by paying the least audit fee. For instance, one of the partners about the rooms in AFR states the following:

“AFR contains fundamental shortcomings and drawbacks, and the regulation suffers from the lack of clear guides to determine budgeted audit hours based on the client size.”

Regarding the third question, they came up with different ways to symbolically comply with the regulation. As mentioned, the most common strategy is calculating the audit fee from the bottom up. For instance, one of the partners states the following:

“After the final agreement of the audit fee with the client, the audit firms proceed to the inverse calculation of the audit fee.”

Taken together, the evidence from the interviews suggests that the audit fee, instead of being initially estimated in compliance with the regulation, is determined from the agreement between the auditor and the client. According to this strategy, the best way to bypass the regulation is to manipulate the budgeted hours. Another way used to symbolic compliance with AFR is that a number of audit firms, after determining audit fees based on the regulation and paying the fee by the client, return a part of the fee to the client’s accounts under various headings. Finally, according to the third strategy, the audit fee is determined in a way that it is not too minimum to seem like a case of non-compliance with AFR; then, they do not pay a part of the fee at all and record it in the account payable, and eventually, it may be applied as stagnant debts.22 The additional evidence provided by the interviews not only incorporates field data and results into our archival research (see Soltes 2014) but also supports the main findings, the non-efficiency of AFR and the ‘symbolic compliance’ view employed by the present study to explain why AFR is not effective in practice.

Appendix B: Definition of Variables

Variable | Measurement |

|---|---|

AudFee | The natural logarithm of total audit fees |

AudFail | 1 if the audit opinion is unqualified in the prior year but financial statements were restated in the current year to correct the last year errors, and 0 otherwise |

AudOpn | 1 if the audit opinion is qualified and 0 for unqualified audit opinion |

AbsDisAcc | Absolute discretionary accruals, as measured by the model developed by Kothari et al. (2005) |

AFR | 1 for period of Audit Fees Regulation (2016–2018), 0 otherwise |

Switch | 1 if auditor switched, 0 otherwise |

NQtoQ | 1 when the audit opinion is qualified for the current year, but not for the prior year |

QtoNQ | 1 when the audit opinion is unqualified for the current year, but not for prior year |

Size | Natural logarithm of a firm’s assets at the beginning of the year |

Lev | Debt-to-asset ratio of a firm at the beginning of the year |

InvRec | Proportion of inventory and receivables to total assets |

Liq | Ratio of total current assets to total current debts |

ROA | The return on assets |

LtoNL | 1 when a client reports a loss for the prior year, but not for the current year |

NLtoL | 1 when a client reports a loss for the current year, but not for the prior year |

FirstRank | 1 if the auditor is a private TAF and ranked as “First” (first-ranked), and 0 if it is other TAF ranked such as “Second”, “Third” and “Fourth” (non-first-ranked); |

StOwn | 1 if more than 50 percent of a firm’s share is owned by the state- or semi-state-owned firms, 0 otherwise |

TSE | 1 if a client firm is listed in Tehran Stock Exchange, 0 otherwise |

Sub | 1 if a firm has a subsidiary or subsidiaries, 0 otherwise |

Busy | 1 if the fiscal year-end of a firm is 20 March, 0 otherwise |

Age | Natural log of the number of years from the establishment of a client firm |

ConOwn | Percent of a firm’s outstanding shares that are owned by the largest shareholder |

Aturn | Asset turnover, computed as sales divided by total assets |

Issue | 1 if a firm issued common or preferred stocks, 0 otherwise |

OCF | Cash flow from operation deflated by total assets |

SG | One-year growth rate in sales |

Disclose | 1 if a client firm discloses audit fees, 0 otherwise |

Δ Management | 1 if chief executive officer or board of directors’ of a client firm have changes to prior year, 0 otherwise |

Post_AFR | 1 for period of Audit Fees Regulation (2016–2018), 0 otherwise |

Δ AudFee | Inflation-adjusted changes in current year audit fees relative to the previous years |

AbAuditFee | Residuals from audit fee regression model (Model 1) as a cross-sectional model in yearly-basis |

EM-DD | Absolute discretionary accruals, as measured by the model developed by Dechow and Dechiv (2002) |

AQPN | The number of audit qualification paragraphs in an audit report |

YearDum | Dummies for fiscal years |

IndustryDum | Dummies for 16 industry groups |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

MohammadRezaei, F., Faraji, O., Rezaee, Z. et al. Substantive or symbolic compliance with regulation, audit fees and audit quality. Int J Discl Gov 21, 32–51 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41310-023-00178-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41310-023-00178-4