Abstract

Migration can contribute to economic growth. Its impact on ethnic diversity may also generate socio-cultural tensions and political instability. Having said that, ethnic diversity can play a role in both promoting and hindering economic growth depending on its form and extent. This role often rests on the levels of either ethnic fractionalization (usually related to higher economic growth) or ethnic polarization (more commonly associated with lower economic growth). Such considerations raise a question about the ways ethnic diversity mediates the relationship between internal migration and economic growth. The following paper responds to that question by focusing on different regions of Indonesia. Drawing on comprehensive statistics and updated classification of Indonesia’s ethnic groups, it presents new evidence on the archipelago’s ethnic diversity which is cross-referenced with recent fractionalization and polarization indexes. This methodological enhancement allows the study to translate with a greater degree of accuracy the mediation of ethnic diversity on the relationship between internal migration and economic growth across Indonesia’s regions than previously carried out. What emerges is a rather mixed picture of the intermediating role of ethnic diversity. There is a significant influence in various regions, but different sets of variables also modulate the relationship in others. We can also discern an identifiable link between the economic region in question, the indicators of ethnic diversity referenced, and the given rate of migration. Placed in composite relief, the findings draw attention to the uneven and complex character of Indonesia’s regional development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

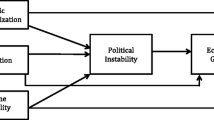

This paper uses data from Indonesia to contribute to debates on the role of ethnic diversity as a mediating variable in the relationship between internal migration and economic growth. Various studies have shown a positive relationship between immigration and economic growth in destination countries (OECD, 2014; Ehrlich & Kim, 2015; Akbari & Haider, 2018). As Coleman (2006) highlights, international migration plays a significant role in changing demographic diversity. That said, demographic diversity can have potentially undesirable consequences. Collier et al. (2001), Ahlerup and Olsson (2012), and Soroka et al. (2016) all argue that public attitudes toward immigration are often negative. This may result in forms of social and political instability and a subsequent downturn in economic growth.

Driven by the seminal work of Easterly and Levine (1997), there has been a significant amount of recent debate over the relationship between changing ethnic diversity and economic growth. Their findings on the negative economic impact of ethnic diversity among African countries have led many studies to go on to examine the link between ethnic diversity and economic growth (Alesina et al., 2003; Montalvo & Reynal-Querol, 2005; Masela, 2013; Gören, 2014; and Bove & Elia, 2017). Yet, as Bleaney and Dimico (2009) argue, an ethnically diverse region is not automatically more prone to severe internal tension and conflict with a subsequent impact on development. Rather, the likelihood of communal conflict can often revolve around the actual pattern of ethnic diversity and the extent to which a setting is either ethnically fractionalized or ethnically polarized.

On the one hand, a region is said to be highly ethnically fractionalized when there are many ethnic groups but they are mostly small. On the other, a region is deemed to have a high level of ethnic polarization when there are few (or only two) large ethnic groups of almost the same size. There are indications that a more ethnically fractionalized region may have a heightened likelihood of episodic tensions, but not necessarily of a severe variety. Whereas a more ethnically polarized region may be less prone to frequent incidents of communal discord but once ignited they can be intense. In other words, a more ethnically fractionalized region may not be harmful to economic growth; it may even promote it through increased differential patterns of activity and a greater openness and adaptability to new ideas and technologies. While, in contrast, a more ethnically polarized region with greater homogeneity of activity may potentially succumb to more intense conflict with deleterious consequences to economic growth and development.

Recent research by Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2021) on the varying relationships between ethnic diversity and economic growth does seem to suggest that ethnic diversity is beneficial to economic growth, although this may depend on the level of the administrative unit under analysis. If ethnic diversity is a spur to innovation, productivity, and trade among districts, then as Parachivescu (2013) and OECD (2014) both argue, immigration needs to be “managed” for countries to obtain economic benefits whilst minimizing potentially adverse social and political effects.

Despite studies being carried out on the relationships between migration and ethnic diversity; ethnic diversity and economic growth; migration and economic growth, much of the literature rarely considers levels of ethnic diversity as a mediating variable in the relationships between migration and economic growth. Additionally, existing empirical findings on the nexus between ethnic diversity and economic growth are often derived from cross-country studies that rely on the cross-referencing of country-specific data. An analytical drawback of the latter type of approach is that composites of data are drawn from a selection of different concepts of ethnicity, varying data collection methods, and distinct data collecting time frames (Benschop et al., 2006).

Moreover, studies examining the relationship between ethnic diversity, internal migration and economic growth using intra-region ethnic diversity within a country are limited in both number and scope (Alesina et al., 2019; Dincer & Wang, 2011; and Mavridis, 2015). For instance, the work of Mavridis (2015) and Alesina et al. (2019) in Indonesia concentrates almost exclusively on the relationship between ethnic diversity and economic growth by employing cross-sectional data based on the 2010 national population census without the benefit of full coverage or the most up-to-date classifications on Indonesia’s ethnic groups. As a result, they fail to capture with a great degree of accuracy the levels of diversity in Indonesia’s districts which unintentionally leads them to a less nuanced appreciation of the mediating role ethnic diversity plays relative to internal migration and economic growth. Auwalin’s (2019) use of data on ethnicity from the Indonesian Family Life Survey (IFLS) to draw out the ways ethnic identity influences migration decisions also disregards representative statistics on ethnicity at the district level. In fact, the IFLS was not even designed to produce representative statistics at that level. Lastly, although falling outside the focus of our paper, it would be remiss not to mention the importance of religion across the archipelago.

The integration of religions, especially Islam, is a significant part of the history, diversity and cultural self-understanding of the country. However, despite the range of religious expression and the multiple factions in each religion across Indonesia, there is very limited actual census data about this diversity (other than major religion classifications and percentages) for us to draw on. On a practical level, this places its consideration largely beyond the scope of our study’s data collection.

With the above limitations and parameters in mind, the following study aims to examine the role of ethnic diversity in mediating the relationships between internal migration and economic growth across Indonesia’s regions. To the best of our knowledge, no other studies have carried out such a detailed examination before with the district as the unit of analysis. Given Indonesia’s significant levels of internal migration and heterogeneous ethnic composition, the second innovation is the use of the comprehensive and refined classification of ethnic groups at the district level provided by Ananta et al. (2015), which is then cross-referenced with Arifin et al. (2015) on ethnic fractionalization and polarization indexes to reinforce the credibility and accuracy of our findings. An additional significance in employing the work of Ananta et al. (2015) and Arifin et al. (2015) is that they both use a complete data set (100% census data), rather than the more usual 10-percent census data sample of other studies. The reason this is important is that data on ethnicity are often clustered, and as a result, a 10-percent sample is likely to overlook some ethnic groups and skew the estimates of ethnic diversity at the district level. Furthermore, using data from one country, Indonesia, avoids the possible difficulties of trying to extrapolate from cross-country differences in culture, politics and institutions.Footnote 1

Background on ethnicity, migration, and development in Indonesia

Indonesia is a vast and diverse entity of land and sea with the fourth largest population in the world. As an archipelago, Indonesia has five main islands - Java, Sumatra, Sulawesi, Kalimantan (two-thirds of Borneo)Footnote 2, and Papua (the western half of New Guinea). Altogether it consists of about 16,000 other smaller islands (Badan Pusat Statistik 2021a), with only about 12.3%Footnote 3 being permanently inhabited. Java comprises only 6.7% of the country’s land area but is the most densely populated area. More than half (56.1%, or 151.6 million) of the 2020 population inhabit the island. Concurrently, more than half (58.8%) of Indonesia’s GDP is generated from Java (Badan Pusat Statistik 2021a). It is the centre of development, hosts the capital city (Jakarta for now, with a planned capital designate move to Ibu Kota Nusantara in East Kalimantan in the coming years), and enjoys more advanced transportation networks, business and trade infrastructure, industries and levels of health and education.

According to the 2020 population census, Indonesia’s population is approximately 270.2 million). However, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the (online) census could only collect information from roughly 13.05% of the total population (Badan Pusat Statistik 2021b). As mentioned, due to the tendency of clustering ethnic groups, the 2020 census data is simply not the most accurate representation of ethnic diversity in Indonesia, especially at the district level. Consequently, the 2010 population census remains the best data set on ethnicity in Indonesia with the proviso of reclassification. If we use the reclassified ethnic groups provided by Ananta et al. (2015), the majority ethnic groups in 2010 include Javanese (40.1%), Sundanese (15.5%), Malay (3.7%), Batak (3.6%), Madurese (3.0%), Betawi (2.9%), Minangkabau (2.7%), Buginese (2.7%), Bantenese (2.0%), Banjarese (1.7%), Balinese (1.7%), Acehnese (1.4%), Dayak (1.4%), Sasak (1.3%), Chinese (1.2%) and other (15.1%). ‘Other’ accommodated more than 600 different ethnic groups. As Carnegie (2019) notes, such statistics show fairly overwhelming diversity.

Historically, Indonesia’s ethnic diversity has had both negative and positive associations with development and this has been largely contingent on the country’s prevailing political and economic situation. It has certainly weighed on the political and bureaucratic organization of the archipelago. During Soeharto’s New Order era (1966–1998), the maintenance of political stability (through various repressive means) was positioned as a critical pillar of his economic development agenda above considerations toward ethnic or regional representation (Carnegie, 2010). On occasion, tensions have spilled over into inter-ethnic conflict alongside periodic demands for secession from certain regions Outside Java Island (OJI). Throughout Soeharto’s rule, ethnic issues and demands were mostly perceived as a political liability and a threat to his authority and legitimacy. The bulk of his legitimacy rested on the promise of stability and economic growth rather than representative plurality. This framing of New Order legitimacy around economic development rather than representation allowed President Soeharto to centralize his brand of authoritarian corporatism (MacIntyre, 1991; Bertrand, 2004).

Through a systematic combination of co-optation, indoctrination and repression, he was able to suppress the political expression and demands of an ethnically diverse polity in the name of national interest and imperatives of the developmental state. The subsequent effect was to largely de-politicise societal identities vis-à-vis the state. Although it should be mentioned that even before his rule, information on ethnicity in Indonesia had been unavailable since the 1930s. Only after the end of the New Order Era in 1998 and after 70 years, the government permitted Badan Pusat Statistik (Statistics-Indonesia) to collect and publish statistics on ethnicity from the 2000 Indonesia population census.

In the wake of reformasi (reform era) and the introduction of decentralization reforms,Footnote 4 more awareness of local contexts grew, including local languages and differences in ethnic identity (Goebel, 2013). From the outset, the 1999 decentralization legislation contained many inconsistencies and its effectiveness varied widely across the archipelago (Fitrani et al., 2005; Eckardt, 2008). The assumption that local government administrations are better placed at dealing with local needs and problems proved to be a rather sanguine expectation and the rapid proliferation (pemekaran) of administrative districts, in some instances, exacerbated rent-seeking behaviour and revenue mismanagement (Carnegie, 2008). Over a hundred sub-divisions of regencies took place between 1999 and 2004, increasing the total number by roughly 50%. By 2005, 33 provinces and some four hundred and fifty regencies and cities were in existence (Carnegie, 2008: 522).

Subsequently, these political reforms coupled with internal migration trends spurred the emergence of political discourses on “locality” in many provinces between putra daerah (sons of the soil) and pendatang (migratory newcomers) that have tested democratizing Indonesia (Barter & Côté, 2015). Political campaigns prioritizing putra daerah have often become a decisive factor in winning local elections (pilkada) for governors (at the provincial level) and mayors or regents (at the district level), and members of parliament at both levels (Cote, 2014; Gayatri, 2010).

To elaborate, following on from Dutch practice dating to 1905, the Soeharto era witnessed extensive programmes of transmigration (transmigrasi - a government-sponsored mass migration) that were promoted initially as a way to reduce the population density in Java to the less densely populated Lampung, a province in Sumatera Island. Later, since the 1980s, the orientation of transmigration shifted to regional development/poverty alleviation in other islands and the involvement of the private sector (Tirtosudarmo, 2018). By the 1990s, more than 3.6 million people had been resettled to outer islands, where they received a subsistence package for relocating, housing and a government allocation of land for cultivation (Carnegie et al., 2021). Over the years, the scale of transmigration in Indonesia and perceived preferential treatment has created tensions and varying degrees of animosity between putra daerah and pendatang, often over economic interests, land use, and access to subsidies, particularly in resource-rich regions such as Kalimantan Barat, Papua, Aceh, and Riau Archipelago or even the tourist magnet of Bali (Davidson, 2003; Duncan, 2007). Notably, in many cases, internal migrants make convenient scapegoats for other more disruptive developmental state and commercial activities. They are often easily “othered” as the unwitting proxies of various underlying political, economic, environmental, and scarcity issues (Barter & Côté, 2015; Carnegie et al., 2021).

Despite the scale of transmigration in Indonesia, ethnic fractionalization does not necessarily mean ethnic polarization.Footnote 5 Migration to Papua in Eastern Indonesia, for example, has increased ethnic fractionalization there, but interestingly, that has not translated into excessive levels of ethnic polarization. As mentioned, although migration has generated tensions between putra daerah and pendatang, the severity of periodic conflicts in Papua is more associated with a different set of longstanding political and resource extraction issues (Ananta et al., 2016). Having situated our study in the ethno-migration-developmental context of Indonesia, we now turn to examine ethnic diversity as a mediating variable in the relationship between migration and economic growth across the regions of the archipelago.

Materials and methods

There is no panel data for this kind of study in Indonesia due to the unavailability of yearly statistics on migration and ethnic diversity at national, provincial, and district levels. The statistics in this study are based on published data, derived mostly from the decennial 2010 population census. As mentioned earlier, the 2010 population census is the most efficacious in providing raw data on ethnicity and migration, especially at the district level. To reduce the possibility of endogeneity between migration and economic growth, we use data on recent migration, measuring whether a respondent’s residence in 2010 differs from the respondent’s residence in 2005, and data on economic growth from 2009 to 2010. This allows us to examine the possible relationship between migration in 2005–2010 and economic growth in 2009–2010. Furthermore, our focus on recent migrants (2005–2010) excludes the state-sponsored transmigrants, who moved from Java decades earlier. Accordingly, we adopt a recursive model (one-way relationship) to examine how ethnic diversity mediates the relationship between migration and economic growth.

The study uses three statistical equations employing multiple linear regression to empirically test the relationships among migration, ethnic diversity, and economic growth. Equation 1 regresses real economic growth on migration (MIG) and two indicators of ethnic diversity with control variables of fertility, urbanization level and per capita income. Ethnic diversity is measured with two common metrics, firstly ethnic fractionalization index / EFI (Alesina & Le Ferrara, 2005; Alesina et al., 2019; Easterly & Levine, 1997;) and second, ethnic polarization index /EPOI (Esteban & Ray, 2008, 2011).

The coefficient of MIG, \({\alpha }_{3},\) in Equation 1 shows the ‘direct’ relationship between migration and economic growth. This ‘direct’ relationship, \({\alpha }_{3},\)indicates that migration is related to economic growth through channels other than ethnic diversity, i.e., the quantity and quality of labour force (Akbari & Haider, 2016; Borsch-Supan et al., 2019; Ehrlick & Kim, 2015), tax revenue (Soroka et al., 2016), and aggregate demand in the host regions (Borjas, 2014; Card & Peri, 2016). The empirical testing for these channels is beyond the scope of this study.

Where \({G\_PCRGDP}_{i}\) is per capita real GDP growth at district i. EFIi is Ethnic Fractionalization Index and EPOIi is Ethnic Polarization Index, which are measured at district i. MIGi refers to the rate of recent in-migration to district i. As mentioned, this model has a set of control variables: Fertility (Feri), Urbanization (Urbi), and Per Capita Income (\({PCRGDP}_{i}\)). Urbi refers to urbanization level at district i.\({PCRGDP}_{i}\) is per capita real GDP at district i.

Fertility is used as a control variable because its differential may result in rising ethnic diversity. Fertility may also correlate to economic growth and impact future labour force without affecting ethnic diversity. Additionally, a more urbanized population may display a greater willingness to accept difference, and this may lessen the association between ethnic diversity and conflict with a corresponding influence on economic growth. Per capita income may also affect economic growth, as a region with a lower per capita income may be more likely to have a higher economic growth rate.

Equation 2 examines the relationship between migration and ethnic fractionalization. EFIi is regressed on Migration (MIGi), controlled by Fertility (Feri) and Urbanization level (Urbi). It analyses how ethnic fractionalization may mediate the relationship between migration and economic growth.

Equation 2 enables the calculation of indirect association between migration and economic growth intermediated by ethnic fractionalization. The indirect association is calculated from the multiplication of α1 in Equation 1 and β1 in Equation 2.

Equation 3 examines the relationship between migration and ethnic polarization (EPOI), in which EPOIi is regressed on Migration, controlled by Fertility (Feri) and Urbanization level (Urbi). This is to test whether and how ethnic polarization mediates the relationship between migration and economic growth.

The indirect association between migration and economic growth is intermediated by ethnic polarization with this equation. The indirect association can be estimated by multiplying \({\alpha }_{2}\) in Equation 1 and \({\gamma }_{1}\) in Equation 3.

The relationships shown in Equations 1, 2, and 3 are initially tested on whether they are linear or non-linear relationships. The non-linear relationship can take a quadratic or cubic form. These three equations are first applied to all districts to represent the analysis at the national level, which is called “Indonesia” in Tables 3, 4 and 5 of the findings section. Following Sharma (2016) and Montalvo and Reynal-Querol (2021), the relationships are then differentiated by economic regions to place emphasis on the importance of spatial variables to ethnicity analysis and incorporating those distinctions. Proceeding with the distinction by Bove and Elia (2017) between developed and developing regions, we test the three questions separately according to the stages of economic development. Districts located in Java Island belong to more economically and socially developed regions, while districts located in Outside Java Island (OJI) are grouped under relatively less developed regions. The statistical modelling is also conducted separately based on the type of districts: City and Regency. City is grouped under more developed regions, and Regency, less developed region.

Data and variables

Equation 1 to 3 are analysed using the most recent statistics on ethnicity and ethnic diversity in Indonesia to date (March 2022). We use the published statistics on the ethnic fractionalization index (EFI) and ethnic polarization index (EPOI) as calculated by Arifin et al. (2015). These indexes were calculated based on the most recent and more accurate classification of ethnic groups in Indonesia carried out by Ananta et al. (2015).Footnote 6 Their use of 100% enumeration reduces potential bias compared to the tendency in smaller samples on ethnicity to cluster data.

As mentioned, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, the 2020 population census falls short of a full enumeration, instead, it is more of a sample census. Therefore, the 2010 population census is still the best census for providing comprehensive and high-quality data on ethnicity in Indonesia, especially at the district level. The 2010 census was the second large-scale undertaking after the 2000 census that collected information on ethnicity since Indonesia gained its independence in 1945.Footnote 7 Significantly, the 2000 census suffered from missing data in several areas due to internal conflicts during the census period, and its ethnic categorization is not as comparable as 2010.

It is important to note that a self-identification approach is used for ethnicity in Indonesia’s population censuses. This means that there is a level of indeterminacy and fluidity whereby respondents can identify themselves with the ethnic group of their choosing. The chosen ethnic groups may also include those not listed by BPS-Statistics Indonesia. If a person cannot decide their ethnic grouping, they can indicate the ethnic group of their father. Interestingly, respondents may also change their ethnic identification over time for many reasons such as evolving self-identity, cost and benefit evaluations of being associated and identified with a specific ethnic group, migration trajectories, and inter-ethnic marriages. In the population census, the ethnicity question was only asked of Indonesian citizens living in Indonesia.

In our study, ethnic fractionalization measures diversity as a function of the number of ethnic groups in a district whilst ethnic polarization indicates the existence of two or more large ethnic groups in a district.Footnote 8 A higher ethnic fractionalization index usually indicates a higher probability of conflict, although the conflict in question may not be intense. On the other hand, a higher polarization index may indicate a probability of more severe conflict.

Given that the study uses district as the unit of analysis, all variables are measured accordingly. The district is the administrative level below province (provinsi) in Indonesia. Districts have become more important in the decentralisation era with a say in the formulation and implementation of development policies. Decentralization ushered in a broader range of representation to the political system than the previously over-centralized state structures allowed (See for example Ananta and Arifin, 2012; Fitrani et al., 2005). A district can be a city (kota) or regency (kabupaten). The difference between the two lies mostly in their stage of economic development. A city is not necessarily 100% urbanized. There are many cities with low urbanization levels in Indonesia. For example, the urbanization level of Subulussalam city in the Province of Aceh is only 19.0%.

Data from the 2010 census covers 497 districts. Fifteen districts are excluded mostly due to the unavailability of accurate data in the wake of decentralization’s administrative unit and boundary proliferation. Information on per capita real GDP growth (PCRGDP) is also unavailable for eight newly established districts, originating from six districts. As a result, these 14 districts are excluded from the analysis. The regency of Mimika in the Province of Papua is also excluded because it is an outlier. Mimika is the only regency experiencing contraction with negative economic growth (-14.6%) during 2009–2010.Footnote 9 In total, 482 districts, consisting of 98 cities and 384 regencies, were selected in the analysis.

Other variables used in the paper are compiled from information on the 2010 population census published online by Statistics-Indonesia. The 2010 population census measured migration in two ways: one is based on the place of birth and the other one is the place of residence in the past 5 years before the census. The latter is used instead of the former to capture recent migration (MIG). Migration (MIG) is expressed here as migration rate, which is the ratio between the number of in-migrants divided by the population aged 5 years and above multiplied by 100. The boundary of places of residence is the district’s boundary. Migrants coming into a district are therefore defined as people whose places of residence in 2005 are different from the districts they lived in 2010 with migration rate referring to the period 2005–2010.Footnote 10

As for fertility (Fert), it is measured as the ratio between the total number of children born to women aged 45–49 and the number of the women themselves, measuring completed or past fertility. The use of past fertility is a way to capture the possible lag effect of fertility on economic growth. Urbanization level (Urbi) refers to the percentage of population living in urban areas of a particular district in 2010.Footnote 11

The statistics on economic growth (R_PCRGDP) and per capita real GDP (PCRGDP) are not collected from the population census but rather from published data by Badan Pusat Statistik (2013). For the purposes of the study, economic growth refers to per capita real GDP growth without oil and gas at the 2000 constant price at each district between 2009 and 2010.

Results and analysis of variables

Before moving on to discuss our study findings, we provide summaries of the selected variables in the analysis, namely inter-district migration, economic growth, and ethnic diversity at the district level. The findings are then presented from regression models to assess the direct relationship between migration and economic growth, ethnic diversity and economic growth, migration and economic growth, and the indirect relationship between migration and economic growth mediated through ethnic diversity.

Inter-district migration and economic growth in Indonesia

Inter-district migration (a move to any other district) between 2005 and 2010 equated to 9.8 million or 4.6% of the Indonesian population aged 5 years and above. The migration rate varied among districts from as low as 0.24% to as high as 26.2% with the mean at 5.2%. The lowest percentage of migrants in Lanny Jaya regency, Papua province, may in part relate to its challenging topography as a hilly and mountainous inland area for settlement. In contrast, the highest migration rate in Tana Tidung regency, North Kalimantan, is more likely a reflection of it being the least populous district with only about 15 thousand people in 2010. The highest migration rate in this regency might not reflect a genuinely high migration inflow. Instead, it is down to a change in its administrative boundary after Tana Tidung was separated from Bulungan regency in 2007 to become its own district. These two districts are OJI. The lowest migration rate in Java Island was 0.3%, observed in Sumenep Regency, Madura Island. The highest migration rate was 17.4% in the city of Yogyakarta. On average, the migration rate into districts in Java Island was lower than OJI. The mean migration rate in City is higher than in Regency (Table 1).

Furthermore, districts in Java Island are more urbanized, with more than half of the population living in urban areas, in contrast to those living in OJI where urbanization levels were 31.3% on average. The urbanization level in Indonesia ranged from 0 to 100% with 20 fully rural districts and 10 fully urban districts. The mean urbanization level among districts was 31.6%, with a higher rate in Java Island than in OJI, and a much higher rate in City than in Regency. Fertility rates were lower in Java than elsewhere, 2.9 vs. 3.6 mean of children born per woman aged 45–49. Yet, the fertility rates were not much different between City and Regency.

Per capita real GDP (PCRGDP) –measuring per capita regional income at the district level –ranged widely from 0.02 million rupiahs to 102.9 million rupiahs in 2010. The economy grew at diverse speeds during 2009–2010 with the growth rate ranging from the slowest, 1.7%, to the highest 28.1%, indicating high diversity in district regional economic growth. The average economic growth (G_PCRGDP) was 6.6%. City economies grew slightly slower than in Regencies but with City income much higher than that in Regency; 9.5 million rupiahs compared to 2.8 million rupiahs respectively. Java is more advanced economically than elsewhere. Per capita real GDP in Java was about five times higher than that of OJI (10.9 million versus almost 2.0 million rupiahs, respectively). However, the economies among districts in Java grew slower than that of OJI, 5.6% compared to 6.9%, respectively.

Ethnic fractionalization and polarization indexes

As Arifin et al. (2015) detail, Indonesia is ethnically highly fractionalized but less polarized than sometimes assumed. Nonetheless, ethnic diversity does vary depending on the province. Central Java is almost a “completely” homogenous province, with a very small ethnic fractionalization index. West Papua is almost a “completely” heterogeneous province with a high fractionalization index. Central Java is also the least polarized province, and North Sumatera is the most polarized province.

Table 2 shows that the ethnic fractionalization index (EFI) among districts ranged from almost fully homogenous (EFI = 0.01) to almost fully heterogeneous districts (EFI = 0.94), with the mean of EFI at 0.40. Geographically, the districts in Java’s most densely populated and advanced economy are less ethnically fractionalized than those located OJI. Furthermore, data indicate that City is more fractionalized than Regency.

East Java, Central Java, and Yogyakarta are almost entirely Javanese. While in West Java, they are mostly Sundanese. In these largely ethnically homogeneous provinces, inter-district migration within a province may not significantly change ethnic diversity in the districts of destinations. For example, inter-district migration within the Province of Central Java will not have a significant impact on ethnic composition in the district as all districts in this province are for all intents and purposes homogenously Javanese. However, given the ubiquity of Javanese as an ethnic group, the migratory trajectories of Javanese may change ethnic composition in districts outside their home provinces (Ananta et al., 2015).

The ethnic polarization index (EPOI) among selected districts ranged widely from not polarized (EPOI = 0.01) to highly polarised districts (EPOI = 0.97). The overall mean of EPOI is 0.45. Districts in Java are less polarized than that of districts located in OJI. Furthermore, with similarities in language, religion, and culture among ethnic groups in Java, especially among Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese and Bantenese, a polarized district there may have low conflict risk. This can differ in a polarized district located in OJI. Table 2 above shows City as more polarized than Regency, but the variation of EPOI in Regency is wider than that in City.

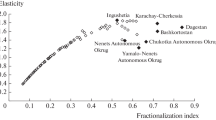

Arifin et al. (2015) conclude that EFI and EPOI among all districts in Indonesia had a cubic relationship, but the plot is closer to an inverted U-curve. The findings of this study indicate similar patterns of relationships between EFI and EPOI in City, Regency, and OJI. However, the pattern is not a fully inverted U-curve in Java, as shown in Fig. 1.

Scatter Plot between EFI and EPOI by Region. (Source: Graphs plotted by the authors based on data from Arifin et al. (2015)

Direct relationship between migration and economic growth

A central question posed by this study is how ethnic diversity mediates the relation between migration and economic growth. Yet, migration may also be related to economic growth “directly” and not necessarily through ethnic diversity. As such, the following sub-section applies Equation 1 to examine how migration is related to economic growth given the level of ethnic diversity, and how ethnic diversity is related to economic growth.

Without controlling the analysis with ethnicity, the result from the OLS model (results not shown in Table 3) indicates that migration is significantly associated with economic growth. The relationship takes a quadratic model forming an inverted U-curve with economic growth as the vertical axis. It displays a rather weak relationship as the coefficient of its quadratic term falls in p-value of 0.065. However, this non-linear relationship becomes stronger when the model factors per capita GDP, fertility rate, and urbanization rate. The coefficients of migration and migration squared are significant at p-value < 0.001, as such the inverted-U curve became stronger. An increase in migration rate is related to higher economic growth up to a peak, and then turns to lower economic growth. The peak of economic growth occurred when the migration rate reached 13.8%. After the peak, there may have been ‘too many’ migrants and a detrimental impact on economic growth. Here, the importance of managing migration rates may emerge.

Equation 1 is performed by adding ethnic diversity as one of the control variables to test the direct relationship between migration and economic growth. The results show that the inverted-U curve between migration and economic growth in Indonesia remained the same, with the p-value < 0.01 for \({\alpha }_{31}\) (Migration) = 0.301 and \({\alpha }_{32}\) (Migration square) = -0.012 (Table 3, column on Indonesia). Therefore, there is a significant relation between migration and economic growth through channels other than ethnic diversity. In other words, given ethnic diversity, migration initially benefits economic growth up to the migration rate of 12.4%.

Interestingly, the pattern is not necessarily the same among different economic regions. As shown in Table 3, an inverted-U curve seen in Indonesia as a whole is only visible in less developed regions: Regency and OJI, where the coefficients for Migration and Migration square are significant at p-value < 0.01. Economic growth peaks are achieved at different migration rates, 11.5%, and 12.3% for the respective regions. On the other hand, the relationship between migration and economic growth is not significant in the more developed regions: City and Java Island. In short, in more developed regions, ethnic diversity significantly mediates the relationship between migration and economic growth. In less developed regions, migration may be related to economic growth both indirectly through ethnic diversity and “directly” (through factors other than ethnic diversity).

Relationship between ethnic diversity and economic growth

Table 3 does show that ethnic diversity matters for economic growth in Indonesia. Ethnic fractionalization index (EFI) is positively related to economic growth, but ethnic polarization index (EPOI) is negatively associated with economic growth. This pattern is evidenced in almost all economic regions. An exception is Java, a more developed region, where EFI does not have a significant relationship with economic growth, but EPOI is positively related to economic growth. As mentioned, this may stem from the fact that districts in Java are relatively more homogeneous with fairly similar but distinct ethnic groups such as Javanese, Madurese, Bantenese, and Sundanese. Consequently, ethnic polarization will in all likelihood not result in significant violent conflicts there but may actually benefit economic growth.

Relationship between migration and ethnic diversity

This sub-section details the relationship between migration and ethnic diversity, measured by ethnic fractionalization index (EFI: Table 4, from Equation 2) and ethnic polarization index (EPOI: Table 5, from Equation 3), followed by an examination of the indirect relationship between migration and economic growth through ethnic diversity. First, the analysis is conducted for Indonesia as a whole and less developed regions, then second on the more developed regions.

Indonesia and less developed regions

Table 4 shows that migration is significantly associated with ethnic fractionalization in Indonesia. The relationship forms an inverted U-curve with \({\beta }_{11}\) (migration) = 0.073 and \({\beta }_{12}\) (migration square) = -0.002 at p-value < 0.001. The peak of ethnic fractionalization is found at a migration rate of 15.9%. Above 15.9%, an increase in migration is likely to be accompanied by declining ethnic fractionalization as migrant numbers are sufficiently large.

The same pattern is observed in less developed regions: Regency and OJI. However, the peaks of EFI are reached at higher migration rates: 16.4% in OJI and 17.3% in Regency. EFI is positively related to economic growth (Table 3). Therefore, the indirect relationship between migration and economic growth intermediated by EFI also follows an inverted U-curve, with the peaks of economic growth at the same migration rates for the respective regions.

Somewhat differently, as shown in Table 5, the relationship between migration and EPOI indicates a cubic curve, with a peak of EPOI followed with a bottom, for Indonesia and less developed regions. However, the peaks for Indonesia and Regency are estimated to occur at migration rates higher than 26.2%, which is very close to the maximum migration rate in the sample of Indonesia and Regency (see Table 1). This means that the relationship between migration and EPOI in Indonesia and Regency is mostly positive.

Having said that, the cubic curve is also seen in OJI, with the peak of EPOI at a migration rate of 8.0% and the bottom at a migration rate of 19.0%. That is, in OJI, migration is positively associated with EPOI until migration rate at 8.0%, and negatively at migration rates at the range of 8.0% and 19.0%, and positively again after 19.0%.

EPOI is negatively related to economic growth in Indonesia and less developed regions (see Table 3). The relationship between migration and economic growth intermediated by EPOI is negative for Indonesia and Regency. It is a cubic curve with minimum economic growth at migration of 8.0%, a maximum economic growth at migration rate of 19.0% in OJI.

More developed regions

The relationship between migration and EFI is significantly positive in both economically more developed regions: City and Java, with its coefficient of 0.05 and 0.03, respectively (see Table 4). As discussed earlier, EFI is not significantly related to economic growth in Java but promotes economic growth in City. Therefore, migration positively contributes to economic growth through ethnic fractionalization in City settings but has a limited relationship with economic growth in Java.

Moreover, the relationship between migration and EPOI differs between City and Java. There is little to no relationship between migration and EPOI in City (see Table 5). As a result, we can say migration does little to affect economic growth through EPOI in City settings. The relationship between migration and EPOI in Java follows a cubic curve, but closer to an inverted U-curve, with maximum EPOI reached at the migration rate of 16.0%. Yet, the maximum migration rate in the Java sample is only 17.4%. Therefore, the relationship between migration and EPOI in Java is mostly positive. As EPOI is positively related to economic growth in Java, we can say migration is positively associated with economic through ethnic polarization.

Discussion of findings

Our study presents new empirical evidence for understanding the role played by ethnic diversity in Indonesia’s regional economic development. We conclude that ethnic diversity is an intermediate variable in the relationship between migration and economic growth but with uneven and mixed results depending on the indicators of ethnic diversity and economic region. In developed regions, ethnic diversity is a primary intermediating variable between migration and economic growth. On the other hand, in Indonesia as a whole and less developed regions, other variables also intermediate the relation between migration and economic growth. Certainly, further study is required to gauge the significance of such intermediate variables.

Nonetheless, findings do show a clear relationship between ethnic diversity and economic growth. If measured via ethnic fractionalization, ethnic diversity is favourable to economic growth. The more diverse the ethnic mix in a district, the higher is the economic growth. Conversely, the data also shows that heightened ethnic polarization harms economic growth. This suggests that an ethnically polarized district is less likely to have high economic growth. One exception in the data is Java, where ethnic fractionalization plays a negligible role for economic growth, instead and rather counter-factually compared to other regions, levels of ethnic polarization can have a favourable impact. As mentioned, the relatively similar ethnic grouping composition on Java, including Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese, and Bantenese means that forms of ethnic polarization there do not necessarily incite severe conflict.

With the relationship between migration and ethnic diversity varying by region, our findings show that the relationship between migration and ethnic fractionalization follows an inverted U-curve in Indonesia and the two less developed regions (Regency and OJI). At a low level of migration, a higher migration is associated with a higher ethnic fractionalization. A peak is then reached when a further increase in migration is likely to be accompanied by lower ethnic fractionalization. The relationship is positive in the two developed regions (City and Java); a higher migration is accompanied by higher ethnic fractionalization.

Data, however, reveal a more complex relationship concerning ethnic polarization as an indicator of ethnic diversity. The relationship is positive for regency (a less developed region) and Java Island (a more developed region). Rising migration is accompanied by higher ethnic polarisation. In OJI (a less developed region), it is close to an inverted curve, where initially rising migration is accompanied by higher ethnic polarization. A threshold is then reached after which further increases in migration are accompanied by declining ethnic polarization. In City (a more developed region), there is little to no relationship between migration and ethnic polarization.

Combining the relationships between migration and ethnic diversity on the one hand and ethnic diversity and economic growth on the other, we conclude that the intermediary role of ethnic diversity in the relationship between migration and economic growth across Indonesia’s regions is as follows. The relationship between migration and economic growth through ethnic fractionalization follows an inverted-U curve in Indonesia and two less developed regions. Initially, rising migration is accompanied by higher economic growth. A peak of ethnic fractionalization is reached at a migration rate of around 16.0% and a further increase in migration is associated with lower economic growth. Measured through ethnic fractionalization, migration may promote economic growth in City settings but remains relatively insignificant for economic growth in Java.

Having said that, the relationship between migration and economic growth through ethnic polarization is more complex. It is negative in regency settings (a less developed region), Java Island (a more developed region) and negligible in City settings (a more developed region). It is a cubic relationship in OJI (a less developed region). Initially, rising migration is associated with lower economic growth until migration rate hits about 8.0%. It is then associated with higher economic growth until migration rate reaches about 19.0%, after which point that shifts again towards lower economic growth.

Conclusion

In sum, our study has shown that migration may not necessarily harm and in certain instances even promote economic growth through increased ethnic diversity in Indonesia. By employing comprehensive and refined classification of ethnic groups at the district level (which were cross-referenced with ethnic fractionalization and polarization indices) allowed the study to produce a more accurate rendering of Indonesia’s internal migration and the heterogeneous character of its ethnic composition than previously available.

The empirical findings draw a rather mixed picture of the role ethnic diversity plays in intermediating the relationship between internal migration and economic growth. There are significant roles played by ethnic diversity in various regions, but different sets of variables also modulate the relationship between migration and economic growth in others.

As the findings suggest, the relationship between ethnic diversity and economic growth varies depending on the indicators of ethnic diversity and regions. Measured on the basis of ethnic fractionalization, ethnic diversity is positively related to economic growth. Somewhat differently, measuring ethnic polarization indicates that ethnic diversity displays a negative relationship with economic growth. One exception in the data is the region, Island of Java, where ethnic fractionalization plays a negligible role in terms of economic growth and where levels of ethnic polarization can have a favourable impact for reasons detailed.

All of which implies that the relationship is largely dependent on the economic region in question, the indicators of ethnic diversity referenced, and the given rate of migration. Our study underscores the complex character and challenges of more equitable development in Indonesia’s regions with one final caveat. Living with ethnic diversity really is a given in a country like Indonesia. Our findings are predicated on a key analytical distinction about the existence of different ethnic groups there. One measure was ethnic fractionalization, where there are many relatively small ethnic groups, and the other was ethnic polarization, where there exist only a few large ethnic groups. As such, we did not address the interplay and implications of assimilation and integration levels in each district. It is a topic that demands further in-depth study and offers an inviting avenue for advancing our understanding of the mediating link of ethnic diversity on internal migration and economic growth in Indonesia.

Notes

See for example Acemoglu (2003) for a detailed discussion on the cross-country political and institutional differences of conflict situations.

See Taylor (2003) and Borneo Project at https://borneoproject.org/borneo-2/ accessed on 24 November 2021.

KOMINFO (Ministry of Communication and Information Technology) 2013 at http://www.kominfonewscenter.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3027:15337-pulau-87-di-indonesia-tak-berpenghuni&catid=36:nasional-khusus&Itemid=54 accessed on 20 November 2020.

Decentralization in Indonesia (desentralisasi) was enacted through Law no. 22/1999 (Regional Governance) and Law no. 25/1999 (Fiscal Arrangements) and formally implemented on 1 January 2001. These laws introduced political devolution of government authority and new fiscal and revenue-raising powers. They were designed to promote greater regional autonomy (otonomi daerah) and give provinces (provinsi), regency (kabupaten) and city (kota) greater says in a more devolved political structure. Legislative amendments enacted by Law no. 32/2004 (Regional Government) placed renewed emphasis on addressing administrative disputes and budget mismanagement, local accountability and closer monitoring by central government.

Ethnic fractionalization relates to the number of ethnic groups in a particular setting whilst ethnic polarization is an indication of the existence of two or more large ethnic groups that are mostly separate from one another.

Ananta et al. (2015) reclassify more than 1,300 ethnic categories into 630 ethnic groups.

See Arifin et al. (2015) for the formula in calculating the indexes.

Mimika is the most fractionalized district with EFI of 0.93.

Data on recent migrants compiled from Badan Pusat Statistik, Sensus Penduduk 2010 https://sp2010.bps.go.id/index.php/site/tabel?tid=272&wid=0.

Fertility data at the district level compiled from Badan Pusat Statistik, Sensus Penduduk 2010: https://sp2010.bps.go.id/index.php/site/tabel?tid=304&wid=0. Urbanization level compiled and calculated from Badan Pusat Statistik, Sensus Penduduk 2010: https://sp2010.bps.go.id/index.php/site/tabel?tid=264&wid=0.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2003). Why not a political coase theorem? Social conflict, commitment, and politics. Journal of Comparative Economics, 31(4), 620–652.

Ahlerup, P., & Ollson, O. (2012). The Root of ethnic diversity. Journal of Economic Growth, 17(2 (June), 71–102.

Akbari, A. H., & Haider, A. (2018). Impact of immigration on economic growth in Canada and its smaller provinces. International Migration & Integration, 19, 129–142.

Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth, 8, 155–194.

Alesina, A., La Ferrara, E., (2005). Ethnic diversity and economic performance. Journal of Economic Literature, XLIII(September), 762–800.

Alesina, A., Gennaioli, C., & Lovo, S. (2019). Public goods and ethnic diversity: Evidence from deforestation in Indonesia. Economica, 86, 32–66.

Ananta, & Aris and Evi Nurvidya Arifin. (2012). “Poverty in democratizing Indonesia”. In Poverty, Food, and Global Recession in Southeast Asia. Edited by Aris Ananta and Richard Barichello. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Ananta, A., Arifin, N., Hasbullah, S. M., Handayani, N. B., & Pramono, A. (2015). Demography of Indonesia’s ethnicity. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

Ananta, A., Utami, D. R. W. W., & Handayani, N. B. (2016). Statistics on ethnic diversity in the land of Papua, Indonesia. Asia & the Pacific Policy Studies, 3(3), 458–474.

Arifin, E. N., Ananta, A., Utami, D. R. W. W., Handayani, N. B., & Pramono, A. (2015). Quantifying Indonesia’s ethnic diversity: Statistics at national, provincial, and district levels. Asian Population Studies, 11(3), 233–256.

Auwalin, I. (2019). Ethnic identity and internal migration decision in Indonesia. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 46(13), 2841–2861.

Badan Pusat Statistik. (n.d.). Online Data Sensus Penduduk 2010. https://sp2010.bps.go.id/index.php/navigation/topik

Badan Pusat Statistik. (2010). Sensus Penduduk 2010. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik.

Badan Pusat Statistik. (2013). Produk Domestik Regional Bruto Kabupaten/Kota di Indonesia 2008–2012. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik.

Badan Pusat Statistik. (2021a). Statistical yearbook of Indonesia 2021. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik.

Badan Pusat Statistik. (2021b). Potret Sensus Penduduk 2020. Jakarta: Badan Pusat Statistik.

Barter, S. J., & Côté, I. (2015). Strife of the soil? Unsettling transmigrant conflicts in Indonesia. Journal of Southeast Asian Studies, 46 no(1), 60–85.

Bertrand, J. (2004). Nationalism and ethnic conflict in Indonesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bleaney, M., & Dimico, A. (2009). Ethnic diversity and local conflicts. Discussion Paper in Economics, University of Nottingham.

Borjas, G. J. (2014). Immigration economics. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Borsch-Supan, A., Leite, D. N., & Rausch, J. (2019). Demographic changes, migration and economic growth in Euro area. In Bank (Ed.), 20 years of European Economic and Monetary Union (pp. 193–290). Frankfurt: European Central Bank. (European Central).

Bove, V., & Elia, L. (2017). Migration, diversity, and economic growth. World Development, 89, 227–239.

Card, D., & Peri, G. (2016). Immigration economics by George J. Borjas: a review essay. Journal of Economic Literature, 54(4), 1333–1349.

Carnegie, P. J. (2008). Democratization and decentralization in post-Soeharto Indonesia. Pacific Affairs, 81(4), 15–25.

Carnegie, P. J. (2010). The Road from authoritarianism to democratization in Indonesia. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Carnegie, P. J. (2019). National imaginary, ethnic plurality and state formation in Indonesia. In S. Ratuva (Ed.), Palgrave Handbook of Ethnicity. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Carnegie, P. J., King, V. T., & Knudsen, M. (2021). Human security, marginality and precariousness in Southeast Asia. International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, 17(1), 1–28.

Coleman, D. (2006). Immigration and ethnic change in low-fertility countries: a third demographic transition. Population and Development Review vol, 32(3), 401–446.

Collier, P., Honohan, P., & Moene, K. O. (2001). Implication of ethnic diversity. Economic Policy, 16(32), 127–166.

Cote, I. (2014). Internal migration and the politics of place: A comparison analysis of China and Indonesia. Asian Ethnicity, 15(1), 111–129.

Davidson, J. (2003). The politics of violence on an Indonesian periphery. Southeast Asian Research, 11(1), 59–89.

Dincer, O., & Wang, F. (2011). Ethnic diversity and economic growth in China. Journal of Economic Policy Reforms, 14, 1.

Duncan, C. R. (2007). Mixed outcomes: The Impact of regional autonomy and decentralization on indigenous ethnic minorities in Indonesia, Development and Change, 38(4), 711–733.

Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (1997). Africa’s growth tragedy: policies and ethnic divisions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(4), 1203–1250.

Ehrlich, I., & Kim, J. (2015). Immigration, human capital, and endogenous economic growth. Journal of Human Capital, 9(4), 518–563.

Eckardt, S. (2008). Political accountability, fiscal conditions and local government performance - cross-sectional evidence from Indonesia. Public Administration and Development, 28(1), 1–17.

Esteban, J., & Ray, D. (2008). Polarization, fractionalization and conflicts. Journal of Peace Research, 45(2), 163–182.

Esteban, J., & Ray, D. (2011). Linking conflict to inequality and polarization. The American Economic Review, 1101, 1345–1374.

Fitrani, F., Hofman, B., & Kaiser, K. (2005). Unity in diversity? The creation of new local governments in a decentralizing Indonesia, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, vol. 41, no. 1, 57–79.

Gayatri, I. H. (2010). Nationalism, democratization and primordial sentiment in Indonesia: problems of ethnicity versus indonesianness (the cases of Riau, Aceh, Papua, and Bali). Journal of Indonesian Sciences in Humanity, 3, 189–203.

Goebel, Z. (2013). The Idea of ethnicity in Indonesia. Working Paper 71. Tilburg University, Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies.

Gören, A. (2014). How ethnic diversity affects economic growth. World Development, 59, 275–297.

Hull, T. (2010). Estimates of Indonesian population numbers: First Impressions from the 2010 census. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, vol. 46, no. 3, 371–375.

MacIntyre, A. (1991). Business and politics in Indonesia. Sydney: Allen & Unwin.

Mavridis, D. (2015). Ethnic diversity and social capital in Indonesia. World Development, 67, 376–395.

Montalvo, J., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2005). Ethnic polarization, potential conflict, and civil wars. American Economic Review, vol. 95, no. 3, 796–816.

Montalvo, J., & Reynal-Querol, M. (2021). Ethnic diversity and growth: Revisiting the evidence. The Review of Economics and Statistics, July 2021, vol. 103, no. 3, 521–532.

OECD (2014). Is migration good for the economy? Migration and Policy Debate, May.

Sharma, M. (2016). Spatial perspective on diversity and economic growth in Alabama, 1990–2011. Southeastern Geographer, vol. 56, no. 3 (Fall), 320–345.

Soroka, S. N., Johnston, R., Kevins, A., Banting, K., & Kymlicka, W. (2016). Migration and welfare state spending. European Political Science Review, 8(2), 173–194.

Taylor, J. G. (2003). Indonesia: peoples and histories. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Tirtosudarmo, R. (2018). The politics of migration in Indonesia and beyond. Singapore: Springer and LIPI.

Paraschivescu, C. (2013). Is migration a problem for EU welfare states? What role can the EU plain in “managing” migration? Revista Romana de Sociologie, 5–6, 402–409.

Benschop, A., Harrison, L. D., Karfi, D. J., & Ericksa, P. G. (2006). Different concepts of ethnicity in a cross-Atlantic study of violence and drug use among deviant youth. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 12, 61–78.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ananta, A., Arifin, E.N., Purbowati, A. et al. Does diversity matter for development? New evidence of ethnic diversity’s mediation between internal migration and economic growth across Indonesia’s regions. J Pop Research 40, 13 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-023-09304-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-023-09304-z