1. Introduction

The taxonomy of copular clauses in 1, as originally proposed by Higgins (Reference Higgins1979), and the general nature of copular verbs and copular constructions have been the subject of lively debate in syntactic and semantic studies (see Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen, von Heusinger, Maienborn and Portner2011, Heycock Reference Heycock and den Dikken2013, Reference Heycock, Gutzmann, Matthewson, Meier, Rullmann and Ede Zimmerman2021, den Dikken & O’Neill Reference Dikken, O’Neill and Aronoff2017, and Arche et al. Reference Arche, Fábregas and Marín2019b for some recent surveys).

(1)

Various attempts have been made to modify, reduce, or extend the typology in 1 and to clarify the relevant semantic and syntactic principles behind it. While it is commonly agreed that sentences with a postcopular AP (and other bare XPs) are predicational, the question of whether sentences with intentional postcopular DPs, such as Alice is the winner, or sentences with classifying postcopular NumPs, such as Alice is a clever girl, belong here as well is controversial.Footnote 1 Although many consider these to be predicational as well, others would rather classify them as equative (Carnie Reference Carnie1997, Beyssade & Dobrovie-Sorin Reference Beyssade and Dobrovie-Sorin2012). Specificational copular clauses are analyzed by some as inverted predicate constructions that are derived from basic predicational (or equative) copular clauses by raising of the predicate to the subject position (Moro Reference Moro1997, Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen2005, den Dikken Reference Dikken2006). Others consider them as a kind of predicational clause with an intensional subject (Romero Reference Romero2005, Arregi et al. Reference Arregi, Francez and Martinović2021) or as equative clauses (Heycock & Kroch Reference Heycock and Kroch1999, Rothstein Reference Rothstein2001). Identificational copular clauses have been analyzed as predicational (Heller & Wolter Reference Heller, Wolter and Grønn2008), specificational (Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen2005) or equative (Heycock & Kroch Reference Heycock and Kroch1999).

The aim of this paper is not to discuss the taxonomy of copular clauses in detail but to examine it in the light of novel historical data from the now extinct Frisian dialect of the island of Wangerooge. These data suggest a principled distinction between predicational copular clauses and identificational copular clauses in a wider sense, that is, as comprising classificational, specificational, and equative ones (compare Carnie Reference Carnie1997, Heycock & Kroch Reference Heycock and Kroch1999, Beyssade & Dobrovie-Sorin Reference Beyssade and Dobrovie-Sorin2012).

The Frisian language consists of three dialect branches: West, East, and North. East Frisian, as (originally) spoken in the north of Germany between the rivers Ems and Weser and in the Wursten district on the east side of the Weser, is further divided into the western Ems-Frisian and the eastern Weser-Frisian dialects. This paper is concerned with the now extinct Weser-Frisian dialect of the island of Wangerooge.Footnote 2 The 19th-century language of Wangerooge has been documented in considerable detail by Heinrich Georg Ehrentraut (1798–1866), who did fieldwork on the island in the years 1837–1844. Ehrentraut provided not only sophisticated grammatical notes and extensive lists of words and phrases, but also a number of texts on the insular geography and way of life, as well as a small, recorded collection of folk tales from the oral tradition (Mitth. I, II, III). On the night of New Year’s Eve in 1854/1855, a storm surge swept away large parts of the sole village on the island of Wangerooge, which in those days had only a few hundred inhabitants. This led to the disintegration of the Wangerooge linguistic community and the decline of the language. Most of the population moved to the settlement Neu-Wangerooge near the village of Varel on the mainland, where Frisian was given up after one or two generations. Those who remained on Wangerooge and rebuilt the island were linguistically assimilated by (Low and High German speaking) newcomers from the mainland. The last speakers of Wangerooge Frisian are said to have died in 1950 in Varel.

The phenomenon of interest here—that is, the grammaticalization of the naming verb heit ‘to be called’ into a copular verb ‘to be’—is only found in Eherentraut’s records from the first half of the 19th century; the grammaticalization process probably stopped and was reversed during the century of language attrition that followed. In the few Wangerooge Frisian texts from the second half of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century I have not found a single occurrence of the copula heit. In Ehrentraut’s material, it is, however, robustly represented, so that one may safely assume that in his days it was a well-established linguistic phenomenon, maybe even still an ongoing grammaticalization process. The corpus contains well over 100 sentences exemplifying the copular use of heit.Footnote 3 In section 2, I give a general description of the copula heit ‘to be’ in Wangerooge Frisian. Next, in section 3, I try to account for the grammaticalization of the naming verb into the copula. In section 4, I consider what the development of this special Wangerooge Frisian copula might teach one about the taxonomy of copular clauses, and how the distribution of heit and wízze should be analyzed. Section 5 offers conclusions.

2. The Copular Verb Heit ‘To Be’ in Wangerooge Frisian

The strong verb heit in Wangerooge Frisian was originally a naming verb cognate with German heißen, Dutch heten, etc.; in fact, it still occurred in the language in the sense of both ‘to call’ and ‘to be called’ after the emergence of the copula heit. In the following example, the verb occurs in both its copular and its original naming sense.

(2)

Consider the following paradigm (Mitth. I, 37; Mitth. III, 251):Footnote 4

(3)

Both syntactic analysis and semantic intuition suggest, however, that, alongside its original naming function (see section 3 for further discussion), heit had acquired the function of the common copula BE normally performed by the verb wízze (common Germanic + wesan-) in Wangerooge Frisian.Footnote 6 The use of heit (next to wízze) was particularly common in copular clauses introduced by the demonstrative pronoun dait ‘that’, which, following Higgins Reference Higgins1979, are usually referred to as identificational copular clauses.Footnote 7 In fact, some 90% of the corpus consists of identificational copular clauses, as in the following examples:

(4)

In many cases, the copular complement involves a NumP with an evaluative adjective or noun, as shown in 5.Footnote 8

(5)

The demonstrative pronoun dait in identificational copular clauses has a number of extraordinary properties with respect to its phonological form, agreement behavior, and reference. It has been analyzed in various ways in the literature. For example, Diessel (Reference Diessel, Ashlee, Kevin and Jeri1997, Reference Diessel1999:58, 78–86) proposes a special type of “predicative demonstratives”, or “demon-strative identifiers.” Scholars who take identificational copular clauses to be a type of specificational copular clause with an inverted predicate consider the demonstrative as a (pro-)predicate (Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen2005); Rullmann & Zwart (Reference Rullmann, Zwart, Jonkers, Kaan and Wiegel1996) analyze it as a subject having the semantic type of a predicate (that is, <e,t>); Heller & Wolter (Reference Heller, Wolter and Grønn2008) argue that it denotes an individual concept; and Moltmann (Reference Moltmann2013) treats it as a trope-referring element. I do not analyze dait in detail here, but I assume that in identificational copular clauses, it is a regular DP subject rather than an (inverted) predicate, and that its special properties are part of the broader phenomenon that 3rd person neuter singular pronouns in Germanic and other languages are underspecified.Footnote 9 The demonstrative dait can take the default gender value (neuter) and the default number value (singular), and refer to a neuter singular DP/NumP, as in 6a. However, it can also evoke an abstract object (Asher Reference Asher1993) in the linguistic or discourse context, as in 6b, or some salient entity in it, as in 6c,d.Footnote 10 In the latter two cases, dait need not agree in gender and number with the DP/NumP that denotes this entity (masculine dan óoberst and feminine djuu íGen), but it must be referentially identified by the postcopular DP/NumP (’n góoden mon and de druuch kant fon Wangeróoch).Footnote 11

(6)

If dait agrees with a neuter singular DP/NumP or if it refers to an abstract object, it may also occur with an AP, NP, or PP predicate and the copula wízze. This is illustrated by the examples in 7a with neutral dait fät and 7b with abstract object all ding mit mait. However, if dait refers to a non-neuter DP/NumP, it is restricted to copular clauses with a DP/NumP predicate. Examples such as the constructed one in 7c, in which the left-dislocated DP dan fúugel is masculine, are not found in the material and were probably ungrammatical in Wangerooge Frisian.Footnote 13

(7)

The combination of the demonstrative and the copula in identi-ficational copular clauses seems to have become fixed to some degree in that it shows special phonological reduction: The demonstrative may lose its final t, as shown in 8.

(8)

In many cases, the demonstrative is completely dropped, as pointed out by Ehrentraut (Mitth. I, 37): “dait hat steht oft für: dait is, wobei denn gewöhnlich der Artikel ausgelassen wird, z. B.: hat ’n a’infolt, das ist ein Einfaltspinsel” [Dait hat often substitutes dait is, in which case the article is usually omitted, for example, hat ’n a’infolt ‘he/she is a simpleton’.]Footnote 14 Topic drop of dait is found in somewhat more than half of the identificational copular clauses with heit in the corpus. Here are some further examples:

(9)

Similar phenomena, that is, phonological reduction, as in 10a,b, and topic drop, as in 10c,d, occur in identificational copular clauses with the copula wízze ‘to be’.Footnote 15

(10)

As the above examples show, all cases of copular heit involve the 3rd person singular present form hat. In fact, the corpus contains only one case of a 3rd person plural present form of the copula (with topic drop of dait):

(11)

Here the copula shows plural agreement with the postcopular DP. At the same time, one example is found in which singular hat is combined with a plural copular complement and where it seems to agree with the singular dropped demonstrative dait:

(12)

The scarcity of examples with a plural postcopular DP/NumP makes it impossible to say anything more about the agreement behavior of copular heit.Footnote 16

The use of heit as a copula seems to have been rather common; yet, as has been noticed before, it was still in competition with the far more frequent original copula wízze. Ehrentraut explicitly points this out in his examples a few times:

(13)

The copula heit seems to have been used nearly exclusively in the 3rd person singular present form hat; with other persons (as in 14), in past tense (as in 15) and with nonfinite verb forms (as in 16), the copula wízze is found.Footnote 17

(14)

(15)

(16)

Moreover, heit only occurs in declarative main clauses in this corpus; in the embedded declarative clauses, as in 17, as well as in the interrogative and exclamative clauses, as in 18, the copula wízze is used.

(17)

(18)

The restriction of heit to the 3rd person singular present form, that is, the unmarked person, number, and tense, in declarative main clauses and the reduction phenomena found in dait + hat (and dait + is) suggest that the introductory pronoun-copula cluster in identificational copular clauses tends to grammaticalize into some sort of presentational particle, that is, a particle highlighting the presentation of new information. Hoeksema (Reference Hoeksema1985) argues, for example, that Dutch das (< dat is ‘that is’) should be listed in the lexicon and inserted in the complementizer position. Below (in section 4) I account for the restricted use of heit as a copula by analyzing hat as a copular particle and as a suppletive allomorph of wízze.

Heit occurs predominantly in identificational copular clauses—the context in which it presumably originated (see section 3); but it clearly spread to copular clauses with a full DP/NumP subject and a DP/NumP complement, that is, to classificational sentences such as 19a,b and specificational sentences such as 19c,d.

(19)

However, copular heit is never found in predicational copular clauses, that is, in sentences with an NP, AP or PP copular complement; in these cases wízze seems to be the only option:

(20)

There are no examples of equative copular clauses in the corpus, either with heit or with wízze, either because equative copular clauses are rare in the first place or because they were not used in Wangerooge Frisian at all.Footnote 18 After this survey of the primary data, the question is addressed how the copular verb heit could arise in the first place.

3. From Naming Verb to Copula

There can be no doubt that the copula heit in Wangerooge Frisian derives from the naming verb heit. This gives rise to the following questions: First, which syntactic and semantic properties of the naming verb may have been conducive to its development into a copular verb? Second, what was the specific syntactic context in which heit could have become competitive with the original copula wízze ‘to be’?

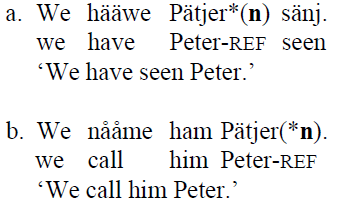

The naming verb heit was used in the sense of both ‘to call’, as in 21, and ‘to be called’, as in 22.Footnote 19

(21)

(22)

I assume that heit ‘to call’ is a causative verb taking a small clause as its complement, whereas heit ‘to be called’ is its unaccusative counterpart, in which the small clause subject is raised to the matrix clause subject position (see Cornilescu Reference Cornilescu2007, Matushansky Reference Matushansky2008, Fara Reference Fara2015).Footnote 20 The assumed structures are illustrated in the following (constructed) examples:

(23)

Here I adopt a quotational view of proper names (Geurts Reference Geurts1997, Bach Reference Bach2002, Matushansky Reference Matushansky2008): First, Ehrentraut sometimes uses quotation marks, which provides a superficial orthographic cue that Wangerooge Frisian proper names in the complement position of heit are quotations. Another, more substantial piece of evidence comes from the fact that the name may be preceded by the prepositional quotative marker fon (on quotative van in Dutch, see Broekhuis & Corver Reference Broekhuis and Corver2015:703–717 and the literature mentioned there; on quotative fan in West Frisian, see E. Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra2011):Footnote 21

(24)

Quotative fon is only recorded in the corpus with causative heit ‘to call’, not with unaccusative heit ‘to be called’.Footnote 22 Note that the definite article in the hydronym de híngstswommels in 24b is part of the name and therefore part of the quotation (“de hingstswommels”).

As quotations, proper names are NP predicates (see Pafel Reference Pafel, Brendel, Meibauer and Steinbach2007, Reference Pafel, Brendel, Meibauer and Steinbach2011). In argument position, they are embedded in a DP with a covert or overt reference marker (for example, a proprial article), so that the name X in argument position denotes something like “the individual named X” (see Matushansky Reference Matushansky2008, Muñoz Reference Muñoz2019). In contrast, the proper name as the complement of the naming verb is clearly a bare NP predicate. In languages in which proper names in argument position must be referentially marked overtly by a proprial article or a proprial suffix this marking is absent in the naming construction. The examples in 25 are from southern German dialects; the examples in 26 are from Mooring, a Mainland North Frisian dialect (Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra, Dammel, Kürschner and Nübling2010).

(25)

(26)

The question is this: How could the naming verb heit ‘to be called’ become a copula and intrude on the domain of wízze ‘to be’? Syntac-tically, both heit and wízze are raising verbs taking a small clause complement (see Stowell Reference Stowell, Farkas, Jacobsen and Todrys1978 and subsequent work), with heit being originally a (semi)lexical (semicopular) verb and wízze a functional (purely copular) verb. Semantically, heit ‘to be called’ differs from the copula wízze only in that it has additional naming lexical content. More specifically, I assume that the naming verb is a copula (BE) that incorporates a name qualifier containing the proprial classifier name (by name), so that it might be paraphrased as ‘to be by name’.Footnote 23 Due to the name qualifier inherent in the semantics of the naming verb, a proper name can be attributed to an individual entity in its particular capacity as a name bearer.Footnote 24 At the same time, if somebody is by name X, he or she necessarily has the name X; that is, the naming verb entails a possessive relationship between the name bearer and his or her name (as in iik heit Wiltert ‘I am called W.’ = ‘I am by name W.’ ⇒ ‘My name is W.’).

Both the name qualifier inherent in the naming verb’s semantics and the possessive entailment can be expressed syntactically. It can be argued that they occur independently (that is, without the support of a copula) in the following postmodifying naming constructions in Germanic languages:

(27)

The English example in 27a contains the name qualifier. In 27b, German namens, a genitive of Name ‘name’ used as a preposition, might be interpreted in the same way. Alternatively, German may use a (comitative-)possessive with-PP, as in 27c, which is also found in West Frisian, as in 27d.

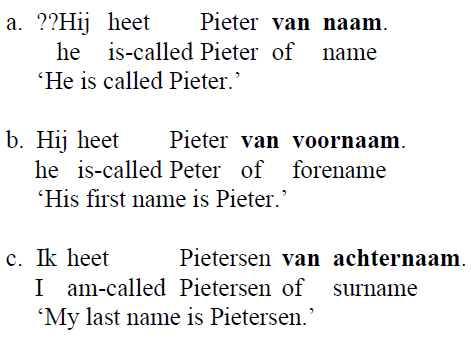

The name qualifier inherent in the naming verb and its possessive entailment can also be expressed using adverbial modifier PPs that occur in the naming construction with the verb to be called. In Dutch, an overt name qualifier van naam can appear in the naming construction with heten ‘to be called’. The use of a simple proprial classifier normally leads to a tautology, as in 28a, but a modified classifier is fine, as in 28b,c.Footnote 24

(28)

It might be argued that the name qualifier is “repeated” overtly here, in order to render modification with voor- and achter- possible.Footnote 26

Alongside the name qualifier one can also find a met-PP in Dutch, expressing the possessive entailment of the naming verb heten ‘to be called’. Again, a possessive PP with a simple propial classifier is felt to be tautological and is hardly acceptable, as in 29a, but a PP with a modified classifier is allowed, as in 29b–d.Footnote 26

(29)

In German, the possessive mit-PP is the only option in this construction:

(30)

It was noted in the previous section that heit as a copula was very frequent in Wangerooge Frisian in identificational copular clauses. Higgins (Reference Higgins1979:237) actually states that these sentences “are typically used for teaching the names of people or of things.” In West Frisian (and in other Germanic languages), a sentence such as 31a with the naming verb hjitte ‘to be called’ can at first sight be paraphrased with an identificational copular clause as in 31b.Footnote 29

(31)

There is, however, a crucial difference between these sentences (see Hengeveld Reference Hengeveld1992:43–45): In 31a, Piter is a quotation (NP predicate), as has been argued above and as the possibility of the quotative fan indicates, whereas in 31b, Piter is a referential DP. This contrast is clearly manifested in languages in which the referentiality of the name is explicitly marked; the reference marker is obligatory in copular sentences:

(32)

Moreover, the constructions in 31 differ in the kind of subject they allow: The naming verb cannot be used with a demonstrative subject, but it is acceptable with a personal pronoun, as in 33a. In contrast, the use of a personal pronoun subject is marked with the copula, but the demon-strative pronoun in the subject position is fine, as shown in 33b.

(33)

In 33a, dat in 33a is ungrammatical because the predicate Piter cannot referentially identify the underspecified demonstrative.Footnote 30 In contrast, the demonstrative is perfect with the referential DP Piter in 33b. In this case, the personal pronoun is infelicitous (note, however, that in English He is Peter is acceptable).Footnote 31 Considering the lack of syntactic overlap it is unlikely that this is the context in which the naming verb found its way to copular sentences in Wangerooge Frisian.

The naming verb is not only used with proper names, however; it can also take kind names as its complements.Footnote 32 Consider the following examples from Wangerooge Frisian, with causative and unaccusative heit in 34 and 35, respectively.

(34)

(35)

Kind names as complements of naming verbs can be nonreferential quotations (NP predicates) like proper names, as quotative fon in 34 clearly indicates, but there is evidence from Wangerooge Frisian and other West Germanic languages that they can also be referential (kind-referring) NumPs or rather NumPs embedding a quotation (see Härtl Reference Härtl, Franke, Kompa, Liu, Mueller and Schwab2020). This is suggested by the fact that they can be accompanied by an indefinite article, as in ’n wárpanker ([’n “warpanker”]) in 35b.Footnote 33 Consider also the following examples from German (which I owe to an anonymous referee):

(36)

In 36a, one finds a bare nonreferential NP predicate (which cannot have accusative case marking), while 36b involves a (case-marked) NumP.

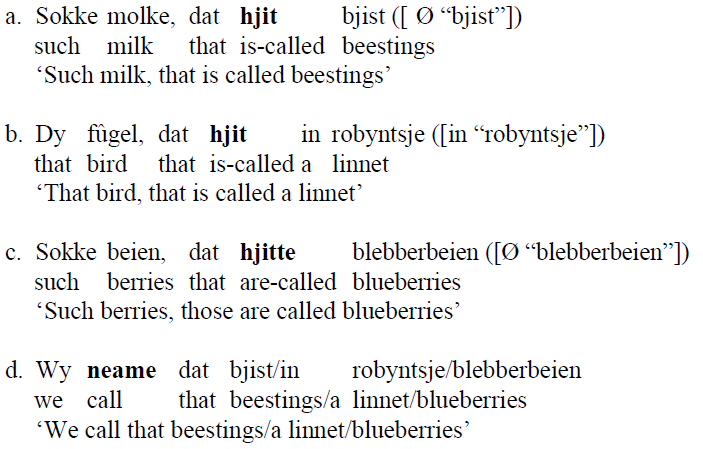

Moreover, in West Frisian, kind names in the predicate position can have an underspecified demonstrative as their subject, unlike proper names (see 33a). This suggests that the predicate qualifies to referentially identify the demonstrative and, therefore, must be a NumP:Footnote 34

(37)

The use of the quotative marker fan is not allowed in such cases, as shown by the contrast in 38.

(38)

In 38a, the NP predicate robyntsje (with an optional quotative marker) cannot referentially identify the underspecified demonstrative dat; only the specified (common gender, singular) demonstrative dy may occur here. In 38b, the NumP in robyntsje can referentially identify dat; here the quotative marker is disallowed and dy is infelicitous. In 38a, one is dealing with attributive predication; the name robyntsje is attributed to dy (fûgel). In 38b, one is dealing with identificational predication; dy (fûgel) is identified as an instance of the kind named robyntsje. This means that naming can be either name-attribution (with a bare NP) or identification by name (with kind-referring NumPs). On the distinction between attributive and identificational predication in copular clauses, see section 4.

In Ehrentraut’s corpus, there is one example with both the unac-cusative and the causative naming verb heit occurring in contexts comparable to those in 37:Footnote 35

(39)

Note that the quotative marker is missing with causative heit in this case, although it is quite common when the small clause subject is not dait (as one can observe in the examples in 34). This is expected, considering the fact that fláskwurst (like ’n métwurst) must be a NumP in order to referentially identify dait (’t) and that the quotative marker can only appear with NP predicates.Footnote 36

When the complement of the naming verb heit is a kind name, there can be a syntactic overlap with wízze in identificational copular clauses:

(40)

To call x “y”, where y is the name of a kind, is to state that x is an instance of y (see Härtl Reference Härtl, Franke, Kompa, Liu, Mueller and Schwab2020). It may have been this semantic entailment that has led to the use of kind-referring NumPs as complements of a naming verb next to nonreferential quotations (NP predicates) in the first place. In order to account for their use with kind-referring expressions, Härtl (Reference Härtl, Franke, Kompa, Liu, Mueller and Schwab2020) assumes that predicates such as call may introduce a copular relation in addition to their naming semantics. I claim that naming verbs such as Wangerooge Frisian heit are basically copular verbs (BE) with an additional naming component (the name qualifier), both in their attributive-predicational use with nonreferential NPs (proper names or bare kind names) and in their identificational-predicational use with kind-referring NumPs. In the latter case, however, particularly in identificational copular clauses with the underspecified demonstrative, which, just like clauses with wízze, are typically used to introduce the names of people or things (Higgins Reference Higgins1979:237), the naming component of the naming verb can be backgrounded. In other words, the difference between naming (in this case: identification by name) and being (in this case: pure identification) can be blurred here. The development of copular heit in Wangerooge Frisian actually shows that in the final stage of the grammaticalization process the naming component can be lost completely.

One finds sentences in Wangerooge Frisian in which it is impossible to discern whether one is dealing with the naming verb heit ‘to be called’ or with the copula heit ‘to be’:

(41)

In ambiguous sentences such as these, heit may first have been reinterpreted as a pure copula (and its complement as a regular NumP instead of a NumP with an embedded quotation).

In cases such as 42, with phonological reduction, and 43, with topic drop of dait, hat can only be interpreted as a copula, since phonological reduction or topic drop of dait is restricted to identificational copular clauses in Wangerooge Frisian:

(42)

(43)

In 42 and 43, heit is unambiguously a copula, that is, it had definitely lost its naming component. On the basis of cases such as these, it may have established itself in all identificational copular clauses, including those in which a naming interpretation of heit is out of the question.Footnote 37

The final question is how the copula heit spread from identificational to other nonpredicational copular clauses (see 19). Here the fact that identificational copular clauses quite frequently show topic drop in Wangerooge Frisian (see 9) might come into play. If dait was deleted by topic drop, a left-dislocated DP could be reanalyzed as the subject of the copular clause. Thus, a sentence like the one in 44a might theoretically have developed from the (constructed) example in 44b with left dislocation and optional topic drop.

(44)

Generalizing from such cases, the use of heit was extended from identificational copular clauses with the demonstrative subject dait to clauses with a full DP subject, that is, to classificational and specifi-cational copular clauses.

4. Wangerooge Frisian Heit and the Taxonomy of Copular Clauses

Now it must be considered what the copula heit in Wangerooge Frisian, as restricted as its use may be, can tell one about the taxonomy of copular clauses. The distribution of heit in Wangerooge Frisian seems to show a distinction between predicational copular clauses, that is, copular clauses with an AP, NP, or PP predicate, and the other copular clause types (classificational, specificational, identificational, and equative); heit is only possible in the latter. Accordingly, the basic distinction would be between copular clauses in which the copula links a (referential) DP/NumP subject with a (nonreferential) lexical projection (AP/NP/PP) and those in which the copula links a (referential) DP/NumP subject with another (referential) DP/NumP. Following Beyssade & Dobrovie-Sorin (Reference Beyssade and Dobrovie-Sorin2012), I call the former attributive predication and the latter identificational predication.

(45)

Attributive copular clauses attribute the property denoted by the postcopular AP/NP/PP to the subject DP/NumP, whereas identificational copular clauses identify the referent of the subject DP/NumPs as the referent of the postcopular DP/NumP. In the latter case, both referents may be individual entities, as in the identificational-equating clause Alice is Miss Jones; but it is also possible for one of them to be an individual concept (an intensional individual) or a kind (a set of individuals).Footnote 38 Therefore, I consider sentences with a DP or NumP complement of the copula not as attributive-predicational but as identificational:

(46)

In identificational-specifying sentences such as 46a, the individual entity denoted by the subject is identified as the binder of the variable provided by the individual concept denoted by the copular predicate. In identificational-classifying sentences such as 46b, the indefinite NumP refers to a kind; the sentence is true if the individual entity denoted by the subject is identified as being an instance of the kind denoted by the copular predicate (Mueller-Reichau Reference Mueller-Reichau2008, Reference Mueller-Reichau2011; Beyssade & Dobrovie-Sorin Reference Beyssade and Dobrovie-Sorin2012; Seres & Espinal 2019).

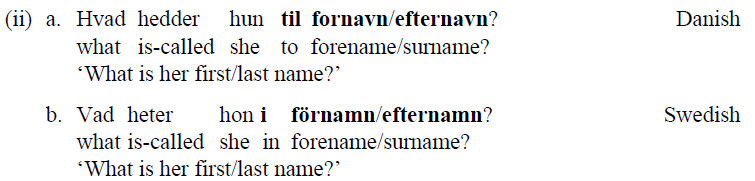

Identificational copular clauses in the sense of Higgins Reference Higgins1979, that is, copular clauses with an underspecified demonstrative subject, may, for the sake of presentation, be referred to as identificational-presentative. In the literature, this type of copular clause is often either left out of consideration or merged with one of the other types of copular clauses. The case of Wangerooge Frisian heit suggests that identificational-presentative copular clauses might be more central to our understanding of the typology of copular clauses than previously thought. They provided the breeding ground for the development of the copula heit from the naming verb heit and served as the springboard for its successive spread to other nonattributive copular clauses. The following data from West Frisian show that, in contrast to sentences with attributive predication, as in 47a, all sentences with identificational predication, including identificational-presentative clauses themselves, can be construed as identificational-presentative clauses with a left-dislocated subject, as in 47b–e.Footnote 39

(47)

The fact that identificational clauses with an underspecified demon-strative subject can stand in for classifying, specifying, and equating ones suggests, on the one hand, that all of them must be basically identi-ficational, and on the other hand that there is no room for an independent identificational-presentative reading (perhaps apart from cases of direct deixis). This, in turn, means that the spread of the copula heit in Wangerooge Frisian was from identificational clauses with an under-specified demonstrative subject to identificational clauses with a full DP subject, rather than from identificational-presentative clauses to the other nonpredicational copular clauses.

Identificational copular clauses do not necessarily have two referential DPs/NumPs on either side of the copula. First, in tautologies, as those in 48 brought up by Heycock & Kroch (Reference Heycock and Kroch1999) and the ones in 49 from German, both flanking elements can be predicates (bare XPs).

(48)

(49)

Second, there can be identificational clauses consisting of a DP/NumP and an NP, if the DP/NumP provides the classifier for the NP predicate:

(50)

(51)

Here the DP/NumP, either the subject or the identificational predicate, provides the classifier (name, profession). These sentences are inter-preted as Her name is the name Alice, The name Alice is a beautiful name, Her profession is the profession of doctor, The profession of doctor is a hard profession, so that one can maintain the claim that semantically, all identificational clauses contain either two referential or two nonreferential expressions.

It would be interesting to know if it were possible to use the copula heit in examples such as 48 and 49 or 50 and 51 in Wangerooge Frisian, as one might expect, if heit were generally used in identificational clauses. Unfortunately, there are no exact matches in the material. However, consider the example in 52.

(52)

In this clause, dait can only refer to a proper name, so in this sense it is comparable to 50b. The presence of heit in this example might thus suggest that in this type of identificational clause, this copula can occur as well (at least when the predicate is a DP/NumP).

How can one account for the fact that heit only occurs in identi-ficational copular clauses in Wangerooge Frisian? There are, in fact, several languages that use formally distinct variants of the copula BE (one of which can be zero) in attributive versus identificational clauses, for example, Chinese (Li & Thompson Reference Li, Thompson and Charles1977), Polish (Rothstein Reference Rothstein, Richard and James1986), Irish (Carnie Reference Carnie1997), Russian (Pereltsvaig Reference Pereltsvaig2007), Hebrew (Greenberg Reference Greenberg, Armon-Lotem, Danon and Rothstein2008), and Thai (Hedberg & Potter Reference Hedberg, Potter, Rolle, Steffman and Sylak-Glassman2010).Footnote 40 So the question extends to such complex copula systems in general.

One might argue that the copula BE is ambiguous between attributive and identificational meaning, and that it is this ambiguity that lies at the heart of the distinction between predicational and identi-ficational copular clauses (see Mikkelsen Reference Mikkelsen2005, Heller Reference Heller2005, Heller & Wolter Reference Heller, Wolter and Grønn2008). In that case, the copula heit in Wangerooge Frisian might make visible a distinction covertly present in the meaning of wízze as well; in other words, heit would be a special identificational copula. However, Heycock & Kroch (Reference Heycock and Kroch1999) convincingly argue that the distinction between predicational (attributive) and equative (identi-ficational) cannot be encoded in the copula BE. They show that there are more (semicopular) verbs that, like BE, can occur both in attributive and identificational copular clauses. They mention, for instance, aspectual verbs such as English become (inchoative BE) and remain (progressive BE).Footnote 41 It would certainly be an overgeneralization, if one were to assume that all these verbs have a homophonous attributive and identificational variant. Moreover, as far as I know, there are no languages with overtly distinct forms for attributive and identificational become and remain. Such a distinction and, more generally, complex copula systems seem to be limited to the semantically void copula BE.

If the attributive versus identificational distinction does not reside in the copula itself, it must be sought in the small clause selected by the copula. In the literature, there are in fact several proposals that posit different structures for attributive-predicational versus identificational small clauses (Carnie Reference Carnie1997, Heycock & Kroch Reference Heycock and Kroch1999) or a different featural make-up of the supposed small clause head (Citko Reference Citko2008). I do not discuss these proposals here but note that the semantic distinction between attributive-predicational and identificational copular clauses does not necessarily have to correspond with a difference in the structure or the featural make-up of the head of the small clause. Underlying all copular clauses might be a unique small clause, the interpretation of which is determined by the nature of both the small clause subject and the small clause predicate. If the small clause subject is referential (DP/NumP) and the small clause predicate nonreferential (AP/NP/PP), the structure is interpreted as attributive-predicational; in contrast, if the subject and the predicate are both referential or both nonreferential, the structure is interpreted as identificational. However, whatever the nature of attributive-predicational and identificational small clauses may be, is there any reason to believe that the copula heit selects an identificational small clause?

If the possibility that copular variants themselves lexically encode the distinction is dismissed (see above), one might consider accounting for their distribution in terms of selection. However, there do not seem to exist verbs other than BE that select either an attributive-predicational or an identificational small clause. Heycock & Kroch (Reference Heycock and Kroch1999:382) explicitly point this out for identificational (equative) small clauses. They (like many others) seem, however, to regard English consider as a verb that selects only attributive-predicational small clauses. The following data appear to confirm this:

(53)

In 53b,c, consider cannot embed the identificational small clause unless the copula be is inserted. Examples such as in 54 show, however, that certain identificational small clauses are possible as a complement of consider.

(54)

Small clauses with a predicate denoting an individual entity such as a proper name or a definite description (as in 53b–d) can never be the complement of consider; they seem to be possible only with the copula be or a semicopular verb that contains BE as part of its semantics (become, remain). Individual entities, which are fully saturated expres-sions, can only become syntactic predicates with the help of the vacuous predicate BE (Beyssade & Dobrovie-Sorin Reference Beyssade and Dobrovie-Sorin2012:80–81). Since the predicate of an “inverse” identificational-specifying small clause is always an individual entity, this type of small clause can never be embedded under consider (see 53b). However, identificational-classifying small clauses always contain a kind-referring predicate (see 54a), the predicate of “noninverted” identificational-specifying small clauses is an individual concept (see 54b), and identificational-presentative and identificational-equating small clauses can have not only an individual entity as their predicate (see 53c,d), but also a kind name (see 54c,d). Identificational small clauses with such unsaturated predicates are unproblematic as a complement of consider. Conse-quently, there seems to be no evidence that consider specifically selects a predicational small clause.

It would appear then that with verbs other than the copula BE, the distinction between attributive-predicational and identificational small clauses may not be captured in terms of selection. Indeed, this unique status of BE would be quite surprising, if one were really dealing with selection here. One would rather expect that a semantically void, functional verb such as BE can only c(ategory)-select a small clause, whereas lexical verbs such as consider might be able to s(emantic)-select either an attributive-predicational or an identificational small clause. At the same time, if the interpretation of a small clause as attributive-predicational or identificational is dependent on the referential status of both the subject and the predicate and not on any special (structural or semantic) properties of the small clause itself, as I suggested above, one would not expect selection to be so specific as to distinguish between different types of small clauses. It seems therefore unlikely that the occurrence of heit in indentificational copular clauses can be ascribed to selection.

If heit is neither an identificational copula nor a copula selecting an identificational small clause complement, how can one account for the distribution of heit and wízze in Wangerooge Frisian (or, for that matter, for variants of BE in other languages with complex copula systems)? The solution might lie in the fact that BE is one of the verbs that is most susceptible to suppletion crosslinguistically (Veselinova Reference Veselinova2006). In the Distributed Morphology framework (Halle & Marantz Reference Halle, Marantz, Hale and Jay Keyser1993 and subse-quent work), it is possible to spell out formally distinct copular variants in different morphosyntactic environments, without assuming that copulas have lexical content (den Dikken & O’Neill Reference Dikken, O’Neill and Aronoff2017:25). Following Myler’s (2018) approach of analyzing complex copula systems as suppletive allomorphy, I assume that the 3rd person singular present form of heit is encroaching on the paradigm of wízze in identificational copular clauses.Footnote 42 There is only one semantically vacuous copula BE in Wangerooge Frisian, which in the 3rd person singular present is spelled out as hat or is.Footnote 43

I assume with Myler (Reference Myler2018) that BE heads a vP (a light verb phrase) and that the small clause, which it selects, is a PredP (Predicate Phrase). Since (Wangerooge) Frisian is an OV language, the vP will be left-branching. I further assume that the PredP acquires a categorial feature by percolation from its predicate (N/A/P in the case of attributive-predicational small clauses, D/Num in the case of identificational small clauses). I have shown that copular heit is not only restricted to the 3rd person singular present, but also to declarative main clauses (see section 2), that is, it only occurs in the verb-second position. One might therefore analyze hat as an unmarked copular particle that is directly inserted in the C(omplementizer) position. However, for the suppletive allomorphy analysis to work in this case, it must still be local enough with respect to the identificational small clause. This is guaranteed by the fact that the copular particle, by virtue of its lexical specification, effectively “spans” the intermediate heads T(ense) (3rd person singular present) and v (BE), and thus can count as adjacent to PredD/Num.Footnote 44

(55)

The distribution of the suppletive 3rd person singular present allomorphs of BE can then be accounted for by the following simplified Vocabulary Insertion rules (neglecting the other paradigm members of BE here):

(56)

The 3rd person singular present of the copula BE in the context of an identificational small clause can be realized by the C-particle hat. Realization of the 3rd person singular present of BE as is is possible in all contexts. This means in effect, that hat and is can both occur in the C-position: hat by direct Vocabulary Insertion, is by movement and Vocabulary Insertion. If 3rd person singular present BE has moved to the C-position of an identificational copular clause, the rules in 56 enter into competition.Footnote 45 The variability of hat and is is thus encoded in the grammar; the sociolinguistic and other usage-related factors determining this variability remain external to grammar and are, in this particular case, virtually unknown.Footnote 46

A suppletive analysis of the copula heit in Wangerooge Frisian is attractive from the broader perspective of Frisian dialectology as well. The East Frisian dialects more generally show a somewhat higher amount of verbal suppletion than other Frisian dialects or other Germanic languages (see Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra2008). The most striking example is the common Germanic strong verb + sehan- ‘to see’, Old Frisian siā, Wangerooge Frisian sjoo. This verb has suppletive past tense and past participle forms in Wangerooge Frisian, which were provided by the weak verb + biilauk ‘to watch (to belook)’:Footnote 47

(57)

In another case, originally suppletive forms may have taken over the complete basic paradigm; thus, common Germanic + geban- ‘to give’, Old Frisian ieva, Wangerooge Frisian -gívve has been fully ousted by reik, originally ‘to reach’, in its normal use and is only preserved in a number of derivations and fixed expressions (such as fargívve ‘to forgive’, too hoo e p gívve ‘to unite in matrimony’ lit. ‘to give together’). One further case of suppletion, in the paradigm of the highly suppletive verb BE, might thus fit in quite well with this more general tendency to suppletion in East Frisian.

The Distributed Morphology approach to the distribution of the copular variants heit and wízze might also open another perspective on the analysis of the naming verb heit. Klein (Reference Klein, Kempf, Nübling and Schmuck2020) proposes to analyze the naming verb (German heißen) as a semantically void copula with narrow categorial restrictions with respect to its complement. It is somewhat unclear if a contentless copula can impose narrow categorial restrictions (see the discussion above), but one might recast Klein’s proposal in the Distributed Morphology framework and consider the naming verb as a variant of BE used with proper names. Above I analyzed the naming verb as a copula + a name qualifier (by name), but one could alternatively view the name qualifier not as part of the semantics of the verb, but as a function of predication with a proper name—the same function that seems to be active in DPs with a proper name (der Peter=the individual by the name of Peter) or in close appositions with a proper name (mein Freund Peter=the friend of mine by the name of Peter). If such an analysis is tenable, the spread of heit in Wangerooge Frisian would not be so much a case of grammaticalization of the naming verb (semicopula) heit into a copula, but rather the extension of the copular variant heit from the domain of proper names to the domain of appellative DPs/NumPs (with a limited range of use). However, since an analysis of the naming verb as either a pure copula (BE) or a semicopula (BE + name qualifier) would not fundamentally change my account of the development of the copula heit in Wangerooge Frisian, I leave the matter open here.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, I discussed the exceptional case of a verb intruding on the domain of the common Germanic copula + wesan-. In Wangerooge Frisian, the naming verb heit ‘to call; to be called’ developed into a copular verb ‘to be’ in the context of identificational clauses, thus entering into competition with the original copula wízze ‘to be’. From identificational-presentative copular clauses, that is, clauses with the underspecified demonstrative subject dait, heit was able to spread to identificational (classifying and specifying) clauses with a full DP/NumP subject, but it did not reach attributive-predicational copular clauses. This suggests a principled distinction between attributive and identi-ficational predication. It does not, however, force the conclusion that heit is an identificational copula or that it specifically selects an identi-ficational small clause complement; copular heit is probably best analyzed as a suppletive allomorph of wízze ‘to be’ used with identi-ficational small clauses. The historical data from Wangerooge Frisian are too limited to allow for any far-reaching conclusions to be drawn, but it might open some new perspectives on the analysis of naming verbs and naming constructions as well as on the typology of copular clauses in the Germanic languages.