Abstract

The idea that the problem of transfer price manipulation vanishes under global adoption of destination-based cash-flow taxation (DBCFT) is based on how firms behave in perfectly competitive or monopolistic markets. We show that the neutralizing effect DBCFT has on transfer price incentives can fail once multinational firms are multi-market oligopolists. Under imperfect competition, a multinational will delegate output decisions to its affiliates so that its transfer price can have a strategic role through its influence on competitors’ actions. Even if all countries adopt DBCFT, transfer prices will not equal arm’s length prices, and they will vary with changes in corporate tax rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Guvenen et al. (2017) calculate that MNEs shifted USD 280 billion in profits abroad in 2012. Heckemeyer and Overesch (2017) uses a meta-analysis to estimate a tax semi-elasticity of pre-tax affiliate profit of 0.8. They attribute approximately 80% of the profit shifting to transfer pricing, while Tørslov et al. (2020) estimate that 40% of multinational profits are shifted to tax havens annually. Clausing (2016) arrives at a similar figure using a regression-based method. Blouin and Robinson (2020) argue that the amount of base erosion is overestimated.

Azar and Vives (2021) reports that Alphabet, Apple, Facebook, Amazon, and Microsoft account for almost 15% of US market capitalization. Gabaix (2011) reports examples of even more extreme market concentration among a small number of firms in Finland, Japan, and Korea. The significant presence of high market concentrations is not a new phenomenon since, for close to five decades, the share of sales to GDP in the USA among the top 100 non-oil firms has been around 30%.

See for example the well-known papers by Vickers (1985), Fershtman and Judd (1987), Sklivas (1987), and Katz (1991). Beyond the IO literature, different strands of the economics literature have studied how the delegation principle affects the design of policy. International trade theory, for example, has studied the implication of delegation of price or quantity setting power to managers by firm owners or headquarters (HQs) for trade policy (see, e.g., Das (1997)). The literature on bureaucratic discretion has a long-standing tradition of analyzing delegation of policy-making authority from legislatures to bureaucrats (see, e.g., Gailmard (2002)).

One could interpret the cost function as exhibiting diseconomies of scope as it would be more efficient for two firms to produce separately since the merged cost per unit is higher than the sum of stand-alone costs.

In line with the literature and in order to bring forward the tax incentives in the simplest possible way, we assume that the MNE is able to price discriminate between the two markets.

We assume there exists a value of \(Q_A\) for which marginal revenue from direct sales in country A is equal to zero, for each value of \(Q_B^*\), there exists a value of \(Q_B\) for which the subsidiary’s marginal revenue is equal to zero, and for each value of \(Q_B\), there exists a value of \(Q_B^*\) for which the competitor’s marginal revenue is equal to zero.

The tax rates will still distort the firms’ output choices because we do not explicitly model capital trade. We omit modelling the capital market in order to focus on the issue of transfer price manipulation.

Our analysis assumes that MNEs do not hold two sets of books. The presumption that MNEs may assign one transfer price to provide managerial incentives and one to save tax payments on the same transaction does not fit with standard practice. “Most MNEs insist on using one set of prices both for simplicity and in order to avoid the possibility that multiple transfer prices become evidence in any disputes with the tax authorities” ( (Baldenius et al., 2004) p. 592). For example, Czechowicz et al. (1982) report that 89% of the US MNEs use the same transfer price for internal and external purposes. Even if the practice of two sets of books has increased since 1982, Eden (1998) (pp.295–299) finds that, at least for merchandise trade flows, MNEs do not keep two sets of books. An even more recent survey by Ernst and Young (2003) indicates that over 80% of parent companies use a single set of transfer prices for management and tax purposes. Their report adds that “alignment of transfer prices with management views of the business can enhance the defensibility of the transfer prices, ease the administrative burden, and add to the effectiveness of the transfer pricing program. In fact, in many countries management accounts are the primary starting point in the determination of tax liability and differences between tax and management accounts are closely scrutinized” (p. 17).

Since the affiliates and the local rival set their strategic choice (quantity) simultaneously, the local rival cannot observe either affiliate’s output before making its own choice. But by observing the transfer price, it can infer how affiliate B will behave. In many countries import prices are public knowledge due to the calculation of tariff payments, and in some industries such as the car industry, import prices are often announced (Schjelderup and Sørgard, 1997). In addition, the multinational has no incentive to offset the incentives conveyed through the transfer price with other managerial incentives because we will show below with eq. (6) that a strategically set transfer price increases the multinational’s profit.

It is common in the literature to use marginal cost as the correct market price. This choice is consistent with the OECD (2022) recommended cost-plus method for calculating an arm’s-length price. In our model, the "plus" is zero. Adding a mark-up would not change our results as it would simply reflect an opportunity cost of selling the intermediate good. The cost-plus method is also the simplest method of all the relevant OECD methods to use. Our adoption of the cost-plus method is a simplification that keeps the analysis tractable without affecting our results.

We use the two configurations of economic and strategic substitutes and economic and strategic complements to illustrate that direction of transfer price manipulation is independent of the tax rate differential because these two configurations arise most often in IO models. The direction of the transfer price manipulation is reversed with the other configurations.

References

Almeida, P. (1996). Knowledge sourcing by foreign multinationals: Patent citation analysis in the US semiconductor industry. Strategic Management Journal, 17(S2), 155–165.

Auerbach, A., & Devereux, M. P. (2017). Cash-flow taxes in an international setting. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 10(3), 69–94.

Auerbach, A. J., Devereux, M. P., Keen, M., & Vella, J. (2017). International tax planning under the destination-based cash flow tax. National Tax Journal, 70(4), 783–801.

Azar, J., & Vives, X. (2021). General equilibrium oligopoly and ownership structure. Econometrica, 89, 999–1048.

Baldenius, T., Melumad, N., & Reichelstein, S. (2004). Integrating managerial and tax objectives in transfer pricing. The Accounting Review, 79, 591–615.

Baldenius, T., & Ziv, A. (2003). Performance evaluation and corporate income taxes in a sequential delegation setting. Review of Accounting Studies, 8(2–3), 283–309.

Bauer, C. J., & Langenmayr, D. (2013). Sorting into outsourcing: Are profits taxed at a gorilla’s arm’s length? Journal of International Economics, 90(2), 326–336.

Becker, J., & Englisch, J. (2020). Unilateral introduction of destination-based cash-flow taxation. International Tax and Public Finance, 27, 495–513.

Bloom, N., Mahajan, A., McKenzie, D., & Roberts, J. (2010). Why do firms in developing countries have low productivity? American Economic Review, 100(2), 619–23.

Blouin, J., & Robinson, L. (2020). Double counting accounting: How much profit of multinational enterprises is really in tax havens (Unpublished paper)? Mimeo.

Bond, E., & Gresik, T. (2011). Efficient delegation by an informed principal. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 20, 887–924.

Bond, E. W., & Gresik, T. A. (2020). Unilateral tax reform: Border adjusted taxes, cash flow taxes, and transfer pricing. Journal of Public Economics, 184, 104160.

Bourgeois, L. J., III., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (1988). Strategic decision processes in high velocity environments: Four cases in the microcomputer industry. Management Science, 34(57), 816–835.

Brekke, K. R., Pires, A. J., Schindler, D., & Schjelderup, G. (2017). Capital taxation and imperfect competition: ACE vs. CBIT. Journal of Public Economics, 147, 1–15.

Bulow, J. I., Geanakoplos, J. D., & Klemperer, P. D. (1985). Multimarket oligopoly: Strategic substitutes and complements. Journal of Political economy, 93(3), 488–511.

Caillaud, B., & Rey, P. (1994). Strategic aspects of vertical delegation. European Economic Review, 39, 421–431.

Clausing, K. A. (2016). The effect of profit shifting on the corporate tax base in the United States and beyond. National Tax Journal, 69(4), 905–934.

Crivelli, E., De Mooij, R., & Keen, M. (2016). Base erosion, profit shifting and developing countries. FinanzArchiv: Public Finance Analysis, 72(3), 268–301.

Czechowicz, L., Choi, F., & Bavishi, V. (1982). Assessing foreign subsidiary performance systems and practices of leading multinational companies. Business International Corporation.

Das, S. P. (1997). Strategic managerial delegation and trade policy. Journal of international economics, 43(1–2), 173–188.

Devereux, M. P., Auerbach, A. J., Keen, M., Oosterhuis, P., Schön, W., & Vella, J. (2021). Taxing profit in a global economy. Oxford University Press.

Eden, L. (1998). Taxing multinationals: Transfer pricing and corporate income taxation in North America. University of Toronto Press.

Elitzur, R., & Mintz, J. (1996). Transfer pricing rules and corporate tax competition. Journal of Public Economics, 60(3), 401–422.

Ernst and Young. (2003). Transfer pricing 2003 global survey. International Tax Services.

Fershtman, C., & Judd, K. L. (1987). Equilibrium incentives in oligopoly. The American Economic Review, 77(5), 927–940.

Fudenberg, D., & Tirole, J. (1991). Perfect Bayesian equilibrium and sequential equilibrium. Journal of Economic Theory, 53(2), 236–260.

Gabaix, X. (2011). The granular origins of aggregate fluctuations. Econometrica, 79, 773–772.

Gailmard, S. (2002). Expertise, subversion, and bureaucratic discretion. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization, 18(2), 536–555.

Graham, J. R., Harvey, C. R., & Puri, M. (2015). Capital allocation and delegation of decision-making authority within firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 115(3), 449–470.

Grandstand, O., Hakanson, L., & Sjolander, S. (1992). Technology management and international business. Wiley & Sons.

Guvenen, F., Mataloni, R. J., Rassier, D. G., & Ruhl, K. J. (2017). Offshore profit shifting and domestic productivity measurement. National Bureau of Economic Research: Tech. rept.

Haufler, A., & Wooton, I. (2010). Competition for firms in an oligopolistic industry: The impact of economic integration. Journal of International Economics, 80(2), 239–248.

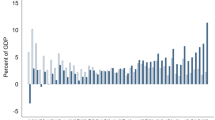

Hebous, S., Klemm, A., & Stausholm, S. (2020). Revenue implications of destination-based cash-flow taxation. IMF Economic Review, 68(4), 848–874.

Heckemeyer, J., & Overesch, M. (2017). Multinationals’ profit response to tax differentials: Effect size and shifting channels. Canadian Journal of Economics, 50(4), 965–994.

Katz, Michael L. (1991). Game-playing agents: Unobservable contracts as precommitments. The RAND Journal of Economics, 22, 307–328.

Keen, M., & Lahiri, S. (1998). The comparison between destination and origin principles under imperfect competition. Journal of International Economics, 45, 323–350.

Nielsen, S. B., Raimondos-Møller, P., & Schjelderup, G. (2003). Formula apportionment and transfer pricing under oligopolistic competition. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 5(2), 419–437.

Nielsen, S. B., Raimondos-Møller, P., & Schjelderup, G. (2008). Taxes and decision rights in multinationals. Journal of Public Economic Theory, 10(2), 245–258.

OECD. (2022). OECD transfer pricing guidelines for multinational enterprises and tax administrations. OECD Publishing.

Papanastasiou, M., & Pearce, R. (2005). Funding sources and the strategic roles of decentralized R &D in multinationals. R &D Management, 35(3), 89–99.

Schjelderup, G., & Sørgard, L. (1997). Transfer pricing as a strategic device for decentralized multinationals. International Tax and Public Finance, 4, 277–290.

Shome, P., & Schutte, C. (1993). Cash-flow tax. Staff Papers, 40(3), 638–662.

Sklivas, S. D. (1987). The strategic choice of managerial incentives. The RAND Journal of Economics, 18(3), 452–458.

Tørslov, T., Wier, L., & Zucman, G. (2020). The missing profits of nations. NBER Working Paper Series.

Vickers, J. (1985). Delegation and the theory of the firm. The Economic Journal, 95, 138–147.

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to David Agrawal, Ron Davies, Andreas Haufler, Kai Konrad, Mohammed Mardan, Maximillian Todtenhaupt, Michael Stimmelmayr and Evelina Gavrilova-Zoutman for constructive comments. We also thank participants of the 2022 IIPF Conference in Linz, Austria, for their questions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: comparative statics

Appendix: comparative statics

1.1 Appendix A. Comparative statics with respect to q on stage-2 quantities when affiliate A is the producer

Totally differentiating first-order conditions (4) yields

Let E denote the 3x3 matrix in (19). \(|E| < 0\) at any locally stable stage-2 equilibrium.

Solving (19) yields

Similar analysis shows that \(\textrm{d}Q_i/\textrm{d}t_A=0\) and \(\textrm{d}Q_i/\textrm{d}t_B=(q^*/(1-t_B)) \cdot \textrm{d}Q_i/\textrm{d}q\) for \(Q_i \in \lbrace Q_A,Q_B,Q_B^* \rbrace\).

1.2 Appendix B Comparative statics with respect to the tax rates on \(q^*\) when affiliate A is the sole producer

Totally differentiating (5), with all expressions evaluated at \(q^*\), yields

where

and

The \(\textrm{d}t_A\) term in (21) consists only of the direct effect of a change in \(t_A\) on (5) because \(\textrm{d}Q_A/\textrm{d}t_A=0\). The \(\textrm{d}t_B\) term in (21) includes indirect terms because \(\textrm{d}Q_i/\textrm{d}t_B \ne 0\) and \(\partial ^2 Q_i/\partial t_B \partial q \ne 0\), where \(Q_i \in \lbrace Q_A,Q_B,Q_B^* \rbrace\). From part A of this appendix, we know that \(\textrm{d}Q_i/\textrm{d}t_B=(q/(1-t_B))\textrm{d}Q_i/\textrm{d}q\) which also implies that

Substituting (24) into (23) then implies

According to (25), an increase in \(t_B\) generates two opposing effects on the marginal profitability of transfer pricing. The first effect reflects a decrease in the marginal benefits of using the transfer price to influence the B affiliate’s market share, while the second effect reflects a cost savings for the B affiliate from lowering its output in response to a higher transfer price.

Solving Eq. (21) we obtain

and

Because of the opposing effects identified in (25), the sign of \(dq^*/dt_B\) is ambiguous.

1.3 Appendix C. Comparative statics with respect to the tax rates on the amount of mis-pricing when affiliate A is the producer

Equation (6) defines not only the equilibrium transfer price but the amount of mis-pricing. We denote the amount of mis-pricing by \(\Delta (t_A,t_B) \equiv q^*-(1-t_A)c^\prime (Q_A(q^*)+Q_B(q^*))\).

Direct calculation shows that

and

From (20),

Inequality (30) implies that the strategic effect on the amount of mis-pricing has the same sign as \(dq^*/dt_x\) for \(x \in \lbrace A,B \rbrace\). Holding \(t_A\) fixed, an increase in \(q^*\) decreases \(Q_A+Q_B\). The reduction in multinational production lowers the multinational’s marginal cost and increases the amount of mis-pricing. However, an increase in \(t_A\) reduces the optimal transfer price and creates a negative strategic effect. At the same time, the direct effect of an increase in \(t_A\) increases the amount of mis-pricing as it lowers marginal cost holding all quantities fixed. Thus, the sign of \(\partial \Delta _A /\partial t_A\) is ambiguous. An increase in \(t_B\) only generates a strategic effect. The effect on the amount of mis-pricing will be ambiguous given the ambiguous effect of \(t_B\) on \(q^*\).

1.4 Appendix D. Comparative statics with respect to \(q^*\) on stage-2 quantities when affiliate B is the producer

Totally differentiating first-order conditions (4) yields

Let E denote the 3x3 matrix in (31). \(|E| < 0\) at any locally stable stage-2 equilibrium. Solving (31) yields

Furthermore, we have

Because the term in parentheses in (33) can be positive or negative, the sign of \(\textrm{d}(Q_A+Q_B)/dq\) is ambiguous. A larger transfer price will result in the multinational selling less in country B. At the same time, the diseconomies of scope between \(Q_A\) and \(Q_B\) will result in the multinational selling more in country A.

Similar analysis shows that \(\textrm{d}Q_i/\textrm{d}t_B=0\) and \(\textrm{d}Q_i/\textrm{d}t_A=(q^*/(1-t_A)) \cdot \textrm{d}Q_i/\textrm{d}q\) for \(Q_i \in \lbrace Q_A,Q_B,Q_B^* \rbrace\).

1.5 Appendix E. Comparative statics with respect to the tax rates on \(q^*\) when affiliate B is the sole producer

Totally differentiating (14), with all expressions evaluated at the equilibrium transfer price \(q^*\), yields

where

and

When \(Q_B\) and \(Q_B^*\) are economic and strategic substitutes or economic and strategic complements, \(d^2 \Pi /dt_B dq<0\) and (34) implies

and

Defining the amount of mis-pricing by \(\Delta _B(t_A,t_B) \equiv q^*-(1-t_B)c^\prime (Q_A(q^*)+Q_B(q^*))\), direct calculation yields

We can rewrite these equations as

where

There is only a direct effect following a change in \(t_A\), whereas there is a direct and an indirect effect following a change in \(t_B\).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Gresik, T.A., Schjelderup, G. Transfer pricing under global adoption of destination-based cash-flow taxation. Int Tax Public Finance 31, 243–261 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-023-09783-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-023-09783-z