Abstract

On 8 January 2023, after 3 years of pandemic control, China changed its management of COVID-19, applying measures against class B infectious diseases instead of Class A infectious diseases. This signaled the end of the dynamic zero-COVID policy and the reopening of the country. With a population of 1.41 billion, China’s reopening policy during the COVID-19 pandemic has been characterized by a scientific, gradual, and cautious approach. Several factors contributed to the reopening policy, including an expansion of healthcare capacity, the widespread promotion and uptake of vaccination, and improved prevention and control mechanisms. According to the latest report from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the country reached a peak of 1.625 million on January 5, 2023, and has since continued to decline. As of February 13, the number decreased to 26,000: a reduction of 98.4%. Thanks to the efforts of healthcare workers and society as a whole, the country managed to get through the peak of the epidemic in a stable manner.

Zusammenfassung

Am 8. Januar 2023, nach 3 Jahren Pandemiebekämpfung, änderte China seinen Umgang mit COVID-19, indem es Maßnahmen gegen Infektionskrankheiten der Klasse B anstelle von Infektionskrankheiten der Klasse A ergriff. Dies bedeutete das Ende der dynamischen Null-COVID-Politik und die Wiederöffnung des Landes. Bei einer Bevölkerung von 1,41 Mrd. zeichnet sich Chinas Wiederöffnungspolitik während der COVID-19-Pandemie durch einen wissenschaftlichen, graduellen und vorsichtigen Ansatz aus. Verschiedene Faktoren trugen zur Politik der Wiederöffnung bei, dazu gehörten die Ausweitung der Kapazitäten des Gesundheitswesens, die umfassende Förderung und Inanspruchnahme von Impfungen sowie verbesserte Präventions- und Kontrollmechanismen. Dem neuesten Bericht des chinesischen Zentrums für Seuchenkontrolle und -prävention zufolge erreichte die Zahl der hospitalisierten COVID-19-Patienten im Land am 5. Januar 2023 einen Höchststand von 1,625 Mio. und ist seitdem kontinuierlich zurückgegangen. Am 13. Februar sank die Zahl auf 26.000. Das entspricht einer Abnahme von 98,4 %. Dank der Anstrengungen der Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter im Gesundheitswesen und der Gesellschaft als Ganzes gelang es dem Land, stabil durch diesen Höhepunkt der Epidemie zu kommen.

Similar content being viewed by others

On 8 January 2023, after 3 years of pandemic control, China changed its approach to managing COVID-19 with measures against class B infectious diseases, instead of Class A infectious diseases. This signaled the end of the dynamic zero-COVID policy and the reopening of the country.

Dynamic zero-COVID vs. zero-COVID

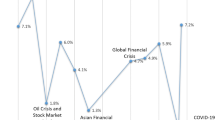

The COVID-19 pandemic hit China in late 2019. Since then, China has effectively brought the pandemic under control and reached a state of “dynamic zero” cases. It is important to note that a dynamic zero-COVID policy is not the same as a zero-COVID policy that seeks to completely eliminate the virus. A zero-COVID policy is not considered appropriate because it is unlikely to eradicate COVID-19; and even if it were possible, maintaining a completely virus-free society would require measures that are not sustainable in the long term. In comparison, a dynamic zero-COVID policy seeks to strike a balance between controlling the spread of the virus and allowing for economic and social activities, while continuously monitoring and adjusting measures as needed. In China, the dynamic zero-COVID policy was guided by a risk assessment system that classified municipal areas into different categories based on the level of risks, and imposed different levels of restrictions accordingly.

Reopening policy

It is challenging to strike a balance between epidemic prevention and control and economic and social development. Each country and city may have its own unique circumstances that require additional considerations and adaptations [1]. China has a population of 1.41 billion. Due to this huge population base, China’s reopening policy during the COVID-19 pandemic has been characterized by a scientific, gradual, and cautious approach. Preparations for the epidemic and changes in the external environment have created conditions for the reopening [2], including the evolvement of the external environment, gradual formation of the COVID-19 immune barrier, the increased awareness of virus prevention, the advancement in COVID-19 treatment, lower virulence of the Omicron variant [3], and the decreased severe COVID-19 rate and mortality rate [4].

Expansion of healthcare capacity

Several factors have contributed to the reopening policy, mainly in the following aspects: First, to prepare for potential risks of medical resource overloading associated with the reopening, in the past 3 years, the National Health Commission of China has taken measures to expand healthcare capacity and make progress in treating COVID-19. Common fever clinics have been opened and critical care beds have been expanded to alleviate medical overloading. Medical institutions across the country have strengthened their respiratory infectious disease prevention and control capabilities, with increased medical beds and equipment, as well as improved medical rescue abilities. Moreover, China’s medical grading diagnosis and treatment system plays an important role in meeting the needs of patients and effectively operating the primary medical system. Antiviral drugs for COVID-19 have been included in medical insurance through fast-approval channels, and maximum efforts are being made to provide drugs to patients in need. The government and health departments at all levels are providing human, financial, and material support to primary medical institutions to help establish an effective and efficient diagnosis and treatment mode.

During the reopening period, China focused on enhancing the ability to treat severe COVID-19 cases, improving the efficiency of transferring severe cases, and preventing mild cases from becoming severe. The collective efforts of the public governance system helped to meet medical needs and navigate the peak of infections.

Vaccination program

Second, SARS-CoV‑2 vaccines have played a critical role in controlling the COVID-19 pandemic in China [5]. With the widespread promotion and the national free vaccination policy, by early November 2022, over 90% of the total population had completed the full course of the new coronavirus vaccine. Research conducted by the National Major Scientific and Technological Infrastructure for Translational Medicine (Shanghai) and the Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center showed that among infected individuals aged 60 or older who received two to three doses of the inactivated coronavirus vaccine, the rate of severe illness protection reached 90.15% [6]. The rate of severe illness protection for all infected individuals was reported to be 96.02%. Data released by a research team from the University of Hong Kong also supported the efficacy of domestically produced inactivated vaccines in preventing severe illness and death [7].

Epidemic prevention and control mechanism

Third, over the past 3 years, China has improved its epidemic prevention and control mechanism for COVID-19. The “State Council Joint Prevention and Control Mechanism” was established as a multidepartment coordination platform to respond to the outbreak of COVID-19. Through this mechanism, many local outbreaks have been successfully controlled, and guidelines have been developed by the National Health Commission and experts in the fields of epidemiology, infectious diseases, medical treatment, and public health policy. The “Diagnosis and Treatment Plan for New Coronavirus Infection” has been updated ten times to provide up-to-date strategies and recommendations.

Weakened viral virulence

Last but not the least, the variant of SARS-CoV‑2 is accompanied by variable characteristics of the clinical picture, with disease severity appearing to be lower with the Omicron variant [8]. Some scientists warned that this does not necessarily reflect less intrinsic virulence. However, in animal experiments with mice and hamsters, Omicron infections also displayed less virulence than previous variants of concern and lung function was less compromised [9]. There is growing evidence to suggest that, with the protection of vaccines and improved treatment conditions, the harm of COVID-19 to the population has significantly decreased over time [10].

These are just some of the prerequisites for reopening during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, the virus is highly contagious, and the short-term surge in confirmed cases is an undoubtful challenge faced by medical institutions after the reopening. The 3‑year period of hard and effective epidemic prevention and control in China has won valuable time and experience for the comprehensive opening up of the country. It seems that the threat of the virus to the population has become more manageable; thus, ending the dynamic zero-COVID policy and reopening the country supports economic recovery and international cooperation. In 2022, Omicron became the dominant strain in China, with a weakened pathogenicity resulting in mostly mild symptoms and a small proportion of severe cases. With high vaccination rates and effective epidemic control measures, the focus shifted from “dynamic clearance” to “protecting vulnerable populations.” On January 7, 2023, the State Council issued the 10th edition of the prevention and control plan, which emphasized vaccination and personal protection, optimized testing strategies, and outlined emergency measures during the epidemic.

Current challenges

After the reopening, medical institutions in China faced a sudden increase in patients with fever and/or respiratory diseases in a short period of time. Healthcare workers dealt with the situation by providing free fever-reducing medication and converting regular care beds to severe care beds in a timely manner; high-risk patients were given antiviral drugs for COVID-19. According to the latest report from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, the number of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in the country reached a peak of 1.625 million on 5 January 2023, and has since continued to decline. As of 13 February, the number has decreased to 26,000, a reduction of 98.4% from the peak. With the efforts of healthcare workers and of society as a whole, the country managed to get through the peak of the epidemic in a stable manner.

The history of human development is also a history of struggle against diseases. During the epidemic stage of major infectious diseases, all individuals and countries worldwide are faced with a challenge. Currently, it can be said that the COVID-19 epidemic prevention and control in the past 3 years has been difficult but effective; in the “enduring battle” against the virus, medical and scientific researchers have continually improved our scientific understanding and moved from being passive to active.

Conclusion

In the past 3 years, the widespread use of vaccines, the availability of treatment drugs, the expansion of medical resources, and the weakened virulence of the virus have all contributed to reducing the deaths and harm caused by infectious diseases. Although we need to be patient and persistent in our efforts to combat infectious diseases, the rapid advances in medical science and technology have provided us with greater possibilities.

References

Zheng JX, Lv S, Tian LG et al (2022) The rapid and efficient strategy for SARS-CoV‑2 Omicron transmission control: analysis of outbreaks at the city level. Infect Dis Poverty 11(1):114

Cai J, Deng X, Yang J et al (2022) Modeling transmission of SARS-CoV‑2 Omicron in China. Nat Med 28(7):1468–1475

Iuliano AD, Brunkard JM, Boehmer TK et al (2022) Trends in disease severity and health care utilization during the early omicron variant period compared with previous SARS-coV‑2 high transmission periods—United States, december 2020–january 2022. Mmwr Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 71(4):146–152

Nyberg T, Ferguson NM, Nash SG et al (2022) Comparative analysis of the risks of hospitalisation and death associated with SARS-CoV‑2 omicron (B.1.1.529) and delta (B.1.617.2) variants in England: a cohort study. Lancet 399(10332):1303–1312

Altmann DM, Boyton RJ (2022) COVID-19 vaccination: The road ahead. Science 375(6585):1127–1132

Fu Z, Liang D, Zhang W et al (2023) Host protection against Omicron BA.2.2 sublineages by prior vaccination in spring 2022 COVID-19 outbreak in Shanghai. Front Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11684-022-0977-3

McMenamin ME, Nealon J, Lin Y et al (2022) Vaccine effectiveness of one, two, and three doses of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac against COVID-19 in Hong Kong: a population-based observational study. Lancet Infect Dis 22(10):1435–1443

Kenney PO, Chang AJ, Krabill L, Hicar MD (2023) Decreased clinical severity of pediatric acute COVID-19 and MIS‑C and increase of incidental cases during the omicron wave in comparison to the delta wave. Viruses 15(1):180

Shuai H, Chan JF, Hu B et al (2022) Attenuated replication and pathogenicity of SARS-CoV‑2 B.1.1.529 Omicron. Nature 603(7902):693–699

Flisiak R, Rzymski P, Zarebska-Michaluk D et al (2023) Variability in the clinical course of COVID-19 in a retrospective analysis of a large real-world database. Viruses 15(1):149

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J. Ge declares that he has no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies mentioned were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ge, J. The COVID-19 pandemic in China: from dynamic zero-COVID to current policy. Herz 48, 226–228 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-023-05183-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-023-05183-5