Abstract

In this paper, we provide an explanation for why risk taking is related to optimism. Using a laboratory experiment, we show that the degree of optimism predicts whether people tend to focus on the positive or negative outcomes of risky decisions. While optimists tend to focus on the good outcomes, pessimists focus on the bad outcomes of risk. The tendency to focus on good or bad outcomes of risk in turn affects both the self-reported willingness to take risk and actual risk taking behavior. This suggests that dispositional optimism may affect risk taking mainly by shifting attention to specific outcomes rather than causing misperception of probabilities. In a second study we find evidence that dispositional optimism is related to elicited parameters of rank dependent utility theory suggesting that focusing may be among the psychological determinants of decision weights. Finally, we corroborate our findings with process data related to focusing showing that optimists tend to remember more and attend more to good outcomes and this in turn affects their risk taking.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Most decisions are taken under risk or uncertainty. Conventional wisdom suggests that one likely determinant of risk taking is whether people are optimistic with respect to risky outcomes. Some empirical studies document a positive correlation between psychometric measures of optimism and risky behaviors such as holding stocks, gambling, or being self-employed (Barber & Odean, 2001; Felton et al., 2003; Gibson & Sanbonmatsu, 2004; Puri & Robinson, 2007; Jacobsen et al., 2014; Weinstock & Sonsino, 2014; Angelini & Cavapozzi, 2017). Yet, little is known about the nature of the relationship between risk taking and optimism and the channels through which they are linked.

In this paper, we present evidence on the psychological processes that drive the relation between optimism and willingness to take risk. The psychology literature defines dispositional optimism as “the expectation that one’s own outcomes will generally be positive” and report evidence that “when optimists do think toward the future, they are able to generate more vivid mental images of positive events than are pessimists, a stronger sense of 'pre-experiencing' those events (despite not having more vivid imaginations in general)” (Carver & Scheier, 2014, p.295). In line with this, we present evidence that optimism determines what comes to people’s minds when thinking about risk and, in particular, whether people focus on favorable or unfavorable outcomes of risk. We therefore hypothesize that heterogeneity in the focus on either good or bad outcomes maps into heterogeneity in risk taking behavior. We investigate this relationship using the general risk question, which asks respondents to state their willingness to take risks on a 11-point Likert scale (Dohmen et al., 2011).

In line with our hypothesis, we find that dispositional optimism, a stable character trait of which importance has long been recognized in personality psychology (e.g., Carver et al., 2010; Carver & Scheier, 2014), is a predictor for respondents’ focus on favorable or unfavorable outcomes when answering the general risk question. We measure this focus by asking directly what people thought about when answering the question. While optimists tend to imagine good aspects of risk, pessimists tend to imagine bad ones. We also document that respondents’ tendency to focus on either positive or negative outcomes of risk when answering the general risk question is a strong predictor of their responses. Finally, we show that focus on good or bad outcomes is the main channel behind the association between optimism and responses to the general risk question. This channel also provides a possible explanation for the gender difference in willingness to take risk as our results show that women exhibit a lower tendency to think about the positive rather than the negative sides of risk.

Next, we assess whether dispositional optimism is correlated with actual risk taking behavior elicited in lottery choices in the laboratory and in real-life self-reported risky behaviors. We find that this is indeed the case, in line with the above cited studies that documented an association between optimism and risk taking. The fact that the general risk question also captures optimism might explain why it has been shown to be a good predictor of risk taking across domains.

Our results can be related to models of decision making under risk. While expected utility theory leaves no room for optimism to affect risk taking behavior, as risk preference is determined solely by curvature of the utility function, non-standard models can incorporate optimism in the form of decision weights that differ from objective probabilities (see Starmer, 2000, for a review). Prospect theory (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) assumes that decision makers distort objective probabilities, overweighting small probabilities and underweighting large ones. From a psychological point of view, overweighting and underweighting might stem from understanding and perception of probabilities. In rank-dependent utility (RDU) (Quiggin, 1982; Tversky & Kahneman, 1992) decision weights depend not only on the probability of the outcome but also on the rank of the outcome. In RDU, decision weights can also be interpreted as arising from the level of attention given to each outcome (see Diecidue & Wakker, 2001, for such an interpretation). For example, a pessimist devotes more attention to the worst outcome and thus assigns a weight which is higher than its objective probability. The opposite happens for an optimist who will assign a weight to the best outcome higher than its objective probability. Hence, the cognitive underpinnings of decision weights might be related either to the level of attention devoted to outcomes or to the perception of probabilities. Descriptive theories of choice under risk such as Prospect theory or RDU are agnostic about the exact psychological mechanisms causing the discrepancy between decision weights and objective probabilities. But it is clear that attention to outcomes and perception of probabilities are distinct processes.

In light of this, in a second study, we elicit parameters of the probability weighting function of a frequently used parameterization of the RDU model, and relate these to dispositional optimism. Our results show that dispositional optimism is related to the elevation of the estimated probability weighting function. As dispositional optimism determines heterogeneity in focusing as shown in our first study, the latter finding suggests that focusing on favorable or unfavorable outcomes likely is an important psychological foundation of decision weights.

Finally, we corroborate the findings from our first study shedding light on the cognitive processes behind the relation between optimism and risk taking. In one experimental task we measure how often people attend to good and bad outcomes in a lottery choice task and in another experimental task we measure how frequently participants recall good or bad outcomes. Using these process data, we show that optimists give more attention to and have better recall of the best outcome in incentivized lottery choices, which affects their subsequent risk taking. In sum, our findings indicate that focusing on advantageous outcomes in choices under risk is an important psychological mechanism through which optimism affects decision weights and hence risk taking behavior.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 introduces the design of our first experiment. Section 3 establishes the link between focusing on the positive or negative outcomes of risk taking, responses to the general risk question, and dispositional optimism. Section 4 investigates the relationship between dispositional optimism, the general risk question and actual risk taking behavior. Section 5 presents the results of our second study, while Section 6 discusses the results and concludes.

2 The experiment

Our first study consisted in a longitudinal experiment composed by three one-hour sessions run in three consecutive weeks. The experiment was computerized using z-Tree (Fischbacher, 2007). Participants were invited from the BonnEconLab subject pool using hroot (Bock et al., 2014). Most of the 348 participants were students (95%) from various fields of study. 61% of subjects were female, and the average age was 22.4 years. In what follows, we describe the variables relevant to our research question. Table 1 shows when and in which order these variables were measured.

General risk question

Our main variable of interest is the general risk question that was validated in Dohmen et al. (2011). We used the same wording as in the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP), that is, “Are you generally a person who is willing to take risks or do you try to avoid taking risks?” on an 11-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all willing to take risks” to “very willing to take risks”.Footnote 1 This question has been shown to predict risk taking behavior across different domains (e.g., Bonin et al., 2007; Caliendo et al., 2009; Grund & Sliwka, 2010; Jaeger et al., 2010; Dohmen et al., 2011; Lönnqvist et al., 2015). It was administered to subjects at the beginning of each session in each week.

Focus questions

In week 3, after subjects had responded to the general risk question, we asked them what aspects of risk they thought of while answering it.Footnote 2 We use the following four questions (7-point Likert scale).Footnote 3

-

Did you rather think of the negative or positive sides of risk? [Risk - neg/pos; scale: “[1] only of the negative sides” to “[7] only of the positive sides”]

-

Did you rather think of small everyday situations or large important ones? [Risk - stake size; scale: “[1] small everyday situations” to “[7] large important situations”]

-

Did you rather think of situations in which there are small or large gains? [Risk - stake size (gains); scale: “[1] small gains” to “[7] large gains”]

-

Did you rather think of situations in which there are small or large losses? [Risk - stake size (losses); scale: “[1] small losses” to “[7] large losses”]

Before responding to these questions, subjects reported in free-form text what they thought of when answering the general risk question. To code the free-form text, we used the following procedure: two research assistants independently coded the free-form answers on four scales along the dimensions of positive/negative valence and stake size (see Section A.3 in the online appendix for details on the coding procedure). For each dimension, we average between the two RAs’ codings (see Brandts & Cooper, 2007, for a similar approach). Spearman rank correlations between the resulting variables and the corresponding focus questions are \(\rho = .39\) for “Free form - neg/pos” and “Risk - neg/pos” (\(p <.001\)), \(\rho = .42\) for “Free form - stake size” and “Risk - stake size” (\(p <.001\)), \(\rho =.14\) for “Free form - stake size (gains)” and “Risk - stake size (gains)” (\(p = .007\)), and \(\rho =.14\) for “Free form - stake size (losses)” and “Risk - stake size (losses)” (\(p = .011\)).Footnote 4

Measures of dispositional optimism

Carver and Scheier (2014) define dispositional optimism as “the expectation that one’s own outcomes will generally be positive”. In accordance with this definition, our main measure is the German version of the so-called Subjects Overweight Probabilities (SOP) questionnaire introduced and validated as an appropriate measure of dispositional optimism by Kemper et al. (2015). It consists of two items eliciting self-reported degrees of optimism and pessimism (7-point Likert scale). The first item is: “Optimists are people who look to the future with confidence and who mostly expect good things to happen. How would you describe yourself? How optimistic are you in general?” The second item reads as “Pessimists are people who are full of doubt when they look to the future and who mostly expect bad things to happen. How would you describe yourself? How pessimistic are you in general?”.

The SOP scale was developed as an ultra-short version of the established (revised) Life Orientation Test (LOT) (Scheier et al., 1994; Herzberg et al., 2006), which we also include in our questionnaire. Similar to Kemper et al. (2015), we establish convergent validity of the two optimism measures as the Spearman rank correlation between SOP and LOT is \(\rho =.76\) (\(p<.001\)). In the main text of the paper, we restrict our analyses to the SOP measure, but results are virtually the same if LOT is used (see Sections A.4 and A.8 in the online appendix for the LOT questionnaire and these results, respectively).

Our design allows us to limit the concern of spillover effects between the risk-related questions and the optimism measures. First, dispositional optimism was elicited at the end of the session. Second, we also elicited SOP and LOT in another week of our longitudinal experiment (week 2). The Spearman rank correlation of measured optimism across weeks is \(\rho =.81\) for SOP and \(\rho =.84\) for LOT (\(p <.001\) for both). All results presented in the paper are robust to using these previously elicited optimism measures (see Section A.8 in the online appendix).

Risk taking behavior

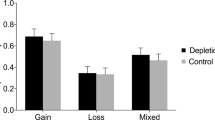

Our behavioral risk taking measure is based on the risk premia for three different lotteries. We elicited certainty equivalents of these lotteries in week 1 and week 3 using a multiple price list format. In both weeks, subjects went through the same three choice lists (see Fig. A1 Section A.5 in the online appendix). In all tables, subjects chose between a safe payment and a lottery paying 15 € with probability p and 0 € with probability \(1-p\). The probability p was 0.25, 0.5, and 0.75 in Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The safe payment increased from 0 € to 15 € in steps of 0.50 €. For each lottery, we average over the risk premia across weeks to reduce noise in our measure of risk taking. Furthermore, we construct a risk premium index aggregating the risk premia for the three lotteries for each subject.

Controls

We control for aspects that have been previously shown to be related to risk preferences. In particular, we control for gender and age (see for example, Croson & Gneezy, 2009, on gender and Dohmen et al., 2017, on age) and a proxy for cognitive ability (Dohmen et al., 2018). This proxy is based on ten Raven matrices (see Section A.6 of the online appendix for the distribution of responses). In addition, in some specifications we also use the Big Five personality characteristics using the 15 item questionnaire developed for the SOEP (Schupp & Gerlitz, 2008; see Nigel et al., 2005, for the relationship between personality and risk preferences). Finally, in some robustness checks, we use a question on current mood elicited at the beginning and at the end of each session, to ensure that our results are related to stable personality components rather than temporary changes in mood.

3 Focusing and the general risk question

To set the stage, we document the correlation between optimism and willingness to take risk in our sample (Spearman’s \(\rho = 0.251\), \(p<.001\)). This is well in line with previous evidence on optimism and risk taking (e.g., Barber & Odean, 2001; Felton et al., 2003; Weinstock & Sonsino, 2014).

Turning now to the channels through which this correlation manifests, we start by describing noticeable patterns in the data on focusing. First, there is considerable heterogeneity in answers to the focus questions, as is reflected by standard deviations in responses. Averages and standard deviations are 3.53 and 1.43, respectively, for “Risk - neg/pos”; 4.06 and 1.56 for “Risk - stake size”; 4.18 and 1.51 for “Risk - stake size (gains)”; as well as 4.49 and 1.58 for “Risk - stake size (losses)”. Second, the correlational pattern between the different focus questions suggests that valence and stake size are orthogonal, as “Risk - neg/pos” and “Risk - stake size” are uncorrelated (Spearman’s \(\rho = -.071\), \(p=.185\)), while all other focus questions are significantly correlated with one another (see Table A2 in the online appendix for details). Third, pairwise Spearman rank correlations between responses to the general risk question and each of the focus questions are significantly different from zero except for "Risk - stake size" (\(\rho = 0.63\) and \(p <.001\) for “Risk - neg/pos”,\(\rho = -.04\) and \(p=.488\) for “Risk - stake size”, \(\rho =.27\) and \(p <.001\) for “Risk - stake size (gains)”, \(\rho = -.28\) and \(p <.001\) for “Risk - stake size (losses)”

Ordinary least squares regressions confirm that answers to the focus questions are systematically related to responses to the general risk question, also when controlling for gender and cognitive ability. The regression results reported in column (1) of Table 2 indicate that subjects who focus on positive rather than negative sides of risk are significantly more willing to take risk. The effect sizes of answers to the other focus questions are smaller. Thinking about higher gains is associated with a significantly higher willingness to take risk and thinking about higher losses with a significantly lower willingness to take risk.Footnote 5

Whether subjects focus on the positive or negative aspects of risk also has by far the highest explanatory power. This is evident from comparing the \(R^2\) of the regressions in models (2) to (5), in which we successively regress the general risk question on one of the focus questions and the set of control variables (\(R^2 = 0.41\) for model (2) and \(R^2 = 0.03\), \(R^2 = 0.09\) and \(R^2 = 0.12\), respectively, for models (3) to (5)). These findings are robust to using responses to the general risk question elicited in weeks 1 or 2, in which we did not elicit the focus questions (see Tables A6 and A7 in the online appendix). In summary, this indicates that what people think of in terms of outcomes of risk is strongly related to self-assessed willingness to take risk.

Table 2 also reveals an interesting finding regarding the gender effect in willingness to take risk. Not controlling for the effects of focusing, women report to be significantly less willing to take risk than men (model (6)). This is consistent with the gender difference in willingness to take risk reported in many previous studies using representative population samples of specific countries (e.g., Dohmen et al., 2011 and across the globe (Falk et al., 2018) as well as in various non-representative population studies (Vieider et al., 2015).Footnote 6 However, once we condition on whether respondents focused on positive or negative aspects of risk when answering the general risk question, the gender difference becomes small and insignificant (models (1) and (2)), indicating that the gender difference in self-assessed willingness to take risk is largely driven by gender differences in the disposition to focus on positive or negative outcomes of risk taking, and not so much by gender differences in the curvature of the utility function.

Our findings are corroborated when we measure focusing in an alternative way, using the variables constructed from the free-form text question that was elicited before the closed-form focus questions (see Section 2 for details on variable construction).Footnote 7 When we replicate the regressions reported in Table 2 using variables derived from free-form text (see Table A4 in the online appendix), we find that subjects’ focus on positive or negative aspects of risk has by far the highest explanatory power. None of the three "free form - stake size" measures is significantly related to willingness to take risks. This confirms that the stake size dimension is somewhat less important than the positive/negative valence dimension. Finally, we find the same pattern regarding the gender effect, namely that the gender effect in willingness to take risks becomes insignificant once we condition on focusing on the positive or negative aspects of risk.

As a next step, we investigate to what extent subjects’ focus is systematically related to dispositional optimism. For this purpose, we regress answers to the focus questions on the SOP, controlling for gender and cognitive ability. The results are shown in Table 3. The coefficient associated with dispositional optimism is significantly different from zero only for the regressions using “Risk - neg/pos” and “Risk - stake size (losses)”, which were also the strongest predictors of answers to the general risk question. These results are robust using using SOP elicited in week 2 or an alternative measure for optimism, i.e., LOT elicited in weeks 2 or 3 (see Table A8 in the online appendix).

In line with the findings from Table 2, women exhibit a significantly lower propensity to think of the positive rather than the negative sides of risk, even when dispositional optimism is not controlled for (see Table A5 in the online appendix). This supports the conjecture that gender differences in risk taking are mainly due to systematic gender differences in what male and female focus on while thinking about risky situations.

The data enable us to perform a number of robustness checks on the relationship between focusing and dispositional optimism (see Tables A9, A10, A11 and A12 in the online appendix). A potential concern is that measurement error in optimism might be correlated with answers to the focus questions. For example, subjects’ mood might affect the optimism measure as well as answers to the focus questions, hence introducing a spurious relationship between the measures, which does not reflect a relationship between the trait component of dispositional optimism and focusing. We address this in several ways. First, we regress the answers to the focus questions on self-stated mood elicited at the beginning of the session (see model (5) in Tables A9 to A12 in the online appendix). Additionally, we regress the answers to the four focus questions on the optimism measures elicited one week prior to asking the focus questions (see model (2) in Tables A9 to A12). Further, to account for measurement error in the optimism measure we (i) average the SOP measures elicited in week 2 and 3 and (ii) we instrument SOP elicited in week 3 with SOP elicited in week 2 using a two stage least squares estimation (see models (3) and (4) of Tables A9 to A12). Finally, to validate the importance of dispositional optimism as a relevant personality characteristic in our context, we run the same specifications of models (3) and (4) adding the Big Five personality traits also corrected for measurement error (see models (6) and (7) of each table).Footnote 8 Similar to the results in Table 3, the coefficient associated with optimism is significantly different from zero across all additional specifications when we use ”Risk - neg/pos” and ”Risk - stake size (losses)” as dependent variables, while it is not for the other two focus questions.

To check whether the relationship between dispositional optimism and willingness to take risk is indeed mediated by attention and focusing, we compare the size of the coefficient on the SOP optimism measure in different regressions on the general risk question (Table 4). When we only include SOP and standard controls as explanatory variables (column (1)), the coefficient on the optimism measure is sizable and significantly different from zero. However, it decreases considerably, once “Risk - neg/pos” is added as an explanatory variable to the regression (columns (2) and (3) in Table 4). In fact, the coefficients on “Risk - neg/pos” are of the same order of magnitude as in Table 2, where the optimism measure was not included in the regression. This suggests that it is not dispositional optimism itself but rather its influence on subjects’ focus in terms of positive or negative outcomes of risk taking, that affects stated risk attitudes. Such a pattern is weaker or non-existent for the other focus questions (models (4) to (6)). These results are robust to using SOP elicited in week 2 or LOT elicited in weeks 2 or 3 (see Tables A13, A14 and A15 in the online appendix).

4 Dispositional optimism and risk taking behavior

So far, we have shown that responses to the general risk question are affected by aspects beyond parameters of a standard utility function. In fact, one crucial aspect is whether people have a disposition to focus on the positive or negative outcomes of risk taking. This disposition can be understood as manifestation of dispositional optimism, an important and stable character trait.

An intriguing question that extends beyond the relationship between focusing and self-assessed willingness to take risk is whether actual risk taking behavior is also affected by optimism as prior studies suggest (see Section 1). If this was not the case, answers to the general risk question would simply contain information irrelevant for risky behavior. Such information would generate measurement error in responses to the general risk question lowering its predictive power (Beauchamp et al., 2017).

Below, we analyze data from our experiment and from a representative sample, and show that dispositional optimism is in fact related to risk taking behavior.Footnote 9 As a measure of risk taking behavior among our student sample in the experiment, we use the risk premium index derived from three incentivized lottery choices (see Section 2). We regress this index on the SOP optimism measure, the general risk question, and basic control variables. Model (1) in Table 5 shows a significant association between risk taking behavior and the optimism measure. Model (2) replicates findings from the previous literature and shows that the general risk question is a significant predictor of risk taking in lottery choice. When we include both the optimism measure and the general risk question in the regression (model (3)), the coefficient on the optimism measure is smaller and not statistically significant. This indicates that the general risk question captures the optimism component, thus making it a useful predictor for risk taking behavior. A similar pattern arises when using each risk premium separately rather than the risk premium index as a dependent variable (see Tables A16 and A17 in the online appendix).

Next, we investigate whether the association between dispositional optimism and risk taking behavior extends to real-life behavior in a representative sample of the German population. For this purpose we use information on self-reported behaviors in the 2014 wave of the SOEP (see for example Wagner et al., 2007). In particular, we focus on two domains that are relevant for economics and directly related to risk taking: portfolio choice and career choice. As a proxy for portfolio choice, we use information about household stock holdings. The variable "Stocks" takes value 1 if at least one household member holds stocks, shares, or stock options and zero otherwise. Since the question is only administered to the household head, the regressions involving this variable use the subsample of household heads. The variable “Self-employed” takes value 1 if an individual is self-employed and 0 for individuals who are in other employment.

As a proxy for dispositional optimism we use the following question: “If you think about the future: Are you...?”(translated from German). Respondents could answer on a scale from 1 to 4, where 1 = “optimistic”, 2 = “rather optimistic than pessimistic”, 3 = “rather pessimistic than optimistic", and 4 = “pessimistic”. For the regression, we translate this into a binary optimism variable that takes value 1 if a respondent was “optimistic” or “rather optimistic than pessimistic” and 0 otherwise. The general risk question has the exact same wording as in our experiment.

In line with our experimental data, the correlation between willingness to take risk as measured by the general risk question and the optimism measure is positive and significant (Spearman rank correlation: \(\rho =.165\), \(p < .0001\)).

To investigate whether dispositional optimism is also predictive of real-life risk taking we run a series of linear probability models reported in Table 6 where we regress the aforementioned measures of risk taking on the optimism measure, the general risk question, and a set of control variables.Footnote 10 In line with the results from our experiment, models (1) and (4) show that the optimism measure is significantly related to both holding stocks and being self-employed. In particular, having an optimistic or rather optimistic view of the future is associated with an increase in the probability of holding stocks (being self-employed) of 4.6 (2.5) percentage points.

Likewise the general risk question (models (2) and (5)) is significantly related to holding stocks and being self-employed. We find that being more willing to take risk according to the general risk question is associated with a 2.3 (5.1) percentage points higher probability of holding stocks (being self-employed). These results are consistent with Dohmen et al. (2011), who find similar effects for the 2004 wave of SOEP.

5 Underlying mechanisms

In previous sections, we have shown that the relationship between dispositional optimism and willingness to take risk is mediated by people’s tendency to focus on good or bad outcomes of risky decisions. Our next steps are i) to relate our findings to a theory of decision under risk which explicitly models optimism, namely rank dependent utility and ii) to learn more about the psychology behind the relationship between optimism and risk taking using process data.

For this purpose, we conducted an additional experiment, in which we elicited measures of dispositional optimism (SOP and LOT) as well as two additional sets of measures. The first relates to decision weights as specified in RDU and the second to attention and memory. We invited 182 participants for a one-hour experimental session. Participants were recruited from the BonnEconLab subject pool via hroot (Bock et al., 2014) and earned on average 14.90 €.

5.1 Optimism and probability weighting

In rank dependent utility models, decision weights are determined both by probability weighting and by the ranking of outcomes (see Quiggin, 1982; Tversky & Kahneman, 1992). Take for example a lottery that yields \(x_1=15\)€, \(x_2=10\)€ and \(x_3=5\)€ with equal probabilities. An RDU decision maker ranks the outcomes according to their respective utilities: u(15€)>u(10€)>u(5€) (under the assumption of a monotonically increasing utility function). Optimism is then captured by the decision weights the agent gives to each outcome. An optimist assigns a weight to the high outcome greater than its objective probability, such as, for example, \(w_1=0.5> \frac{1}{3}\). Since the weights must sum to 1, the sum of the other two weights will be \(w_2+w_3=0.5\), and could be distributed as \(w_2=0.3\) and \(w_3=0.2\). In contrast, a pessimist could, for example, assign weights in the opposite way as \(w_1=0.2\), \(w_2=0.3\), and \(w_3=0.5\). Hence, from the perspective of the model, decision weights can be interpreted as attention to outcomes or misperception of probabilities (see Diecidue & Wakker, 2001). While these two psychological processes are not distinguishable in the model, it is interesting to know which of the two may be a plausible underlying determinant of decision weights. In light of this, we relate dispositional optimism, which we have shown to be mainly related to attention and focusing, with an estimate of the parameter governing optimism in RDU.

To investigate this relationship, we estimate probability weighting functions at the individual level using a series of choice list tables adapted from Fehr-Duda et al. (2006).Footnote 11 The procedure requires each subject to complete 25 choice tables. Each table consists of 20 rows, where each row is a choice between a lottery and a safe payment, with the safe payment decreasing from the high outcome to the low outcome of the lottery in equal steps moving down the rows (see Table A24 in the online appendix for a summary of the parametrization). We use the switching point from choosing the guaranteed amount to the lottery as our estimate of the subject’s certainty equivalent for the lottery. Hence, we can write the equivalence relation between the safe payment and lottery G as:

where \(x_{L}\), \(p_{L}\), \(x_{l}\), indicate the high outcome, its probability, the low outcome, respectively. In order to estimate \(U(\cdot )\) and \(w(\cdot )\), we specify functional forms as in Bruhin et al. (2010) and Murad et al. (2016) by assuming a simple CRRA power utility function:

This specification is parsimonious in modeling risk attitudes via a single curvature parameter.

Regarding the probability weighting function we assume the linear-in-log-odds function proposed by Goldstein and Einhorn (1987) and Lattimore et al. (1992):

The advantage of this specification is that the two parameters have a clear interpretation: the \(\delta\) parameter captures the elevation of the probability weighting function, while \(\gamma\) captures its curvature. Hence, \(\delta\) reflects to what extent subjects overweight probabilities and can be considered a measure of optimism (see, e.g., Lattimore et al., 1992; Bruhin et al., 2010).Footnote 12

We derive individual risk preference parameters (curvature of utility and probability weighting function) under rank-dependent utility theory through a maximum likelihood estimation. The estimation converges for all but one subject. Of the remaining 181 subjects 164 exhibit an inverse S-shaped weighting function, 10 have globally convex weighting functions, and 2 subjects have either a globally concave or an S-shaped weighting function. Only for 5 subjects in our sample the estimated parameters (\(\delta\) and \(\gamma\)) are consistent with expected utility theory, i.e., not significantly different from 1. The distributions of the estimated \(\delta\), \(\gamma\), and \(\alpha\) parameters are reported in the online appendix in Fig. A3.

As described above, \(\gamma\) governs the curvature of the probability weighting function, while the \(\delta\) parameter governs the elevation of the weighting curve and a high \(\delta\) can be generally interpreted as reflecting optimism (see, e.g., Bruhin et al., 2010).

When regressing dispositional optimism as measured by SOP on the estimated parameters of the probability weighting function (Table 7), the coefficient on \(\delta\) is significant and positive, independent of whether or not we include \(\gamma\) and/or the usual control variables. This indicates that the psychology underlying decision weights in RDU may be related to focusing and attention rather than misperception of probabilities.

5.2 Optimism and process data

In Section 4 we found that optimism predicts actual risk taking in lottery choices in the lab and risky behaviors in the field. While for the general risk question we could pin down the focusing channel through which optimism affects responses using the focus questions, for lottery choices and field behavior we have so far only presented evidence on the link between optimism and risk taking behavior. In this section, we show that this link also runs through focusing and attention by providing process data from two novel tasks implemented in our second study.

The first task is designed to capture selective attention in a setup where subjects have complete information about the risky environment. Subjects decide between a lottery with equal probabilities assigned to each of two outcomes (5 € and 20 €) and a safe payoff (13 €). The payoffs of the lottery are initially not displayed but hidden behind gray boxes on the screen. Subjects can see each outcome when they move the cursor onto the respective box. As soon as the cursor leaves the box, the outcome disappears again. They can move the cursor on both outcomes as long and as often as they like. On average subjects locate their cursor on the box containing the high outcome significantly more often than on the one containing the low outcome (3.4 times vs. 2.5 times, Wilcoxon signed rank test: \(p < .0001\)). As an individual measure of selective attention, we compute the difference between the number of times the high outcome and the low outcome are viewed.

The second task we introduce refers to a more automatic process: memory. During the experiment, participants read two short vignettes where a risky choice is made. For one of the vignettes a good, for the other a bad outcome arises. Both the order and the outcomes of the vignettes are balanced across subjects (see Section 10 for the text of the vignettes and further details). In an online survey that subjects completed one week after the experiment, we asked them to state which of the vignettes came to their mind first.Footnote 13 They answer this question in a free-form text first and then as a binary choice between the general topics of the two vignettes (see Section 10). Although reading the vignettes was not incentivized, we are confident that subjects actually read the texts since they spent on average 43 (39) seconds on the first (second) vignette and no one spent less than 21 (15) seconds. According to the free-form text measure 36% of subjects recall the vignette with the negative outcome, and 37% of subjects recall the vignette with the positive outcome. The others state they do not remember or give unclear answers. In the binary measure, recall is also evenly distributed between the two vignettes (50% each). Our measure of selective memory is whether subjects remember the vignette where the good or the bad outcome arises.Footnote 14

In Table 8, we regress the measures derived from the two tasks above on our measure of dispositional optimism controlling for other observable individual characteristics.

Both the measures of selective attention and memory are significantly correlated with SOP (see Table 8 columns (1) and (2)). These findings parallel with the association between optimism and the focus questions in the realm of the general risk question. This evidence further strengthens our interpretation that optimism determines which portion of the environment people focus on.

In Section 4, we have shown that dispositional optimism explains subjects’ risky choices in choice list tables and in real-life behavior. Here, we can move a step further and, having established that optimism is associated with focusing, we can check whether focusing in turn explains risky choices for the same risky task. We do so by observing the choices people actually make in our first task. The more often subjects look at the high outcome relative to the low outcome, the less likely they are to choose the safe payoff (Pearson correlation coefficient: \(r = -.198\), \(p=.007\)). This indicates that dispositional optimism has an indirect effect on risk taking via focusing, similar to the one hypothesized for the general risk question and reported in Tables 5 and 6.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we have investigated the psychology of the relation between optimism and risk taking. We have shown that optimism is correlated with the disposition to focus on good or bad outcomes. While optimists tend to focus on the positive outcomes associated with risk, pessimists tend to focus on the potential negative outcomes of risky decisions and this translates into differences in self-reported willingness to take risks. Moreover, our data strongly suggest that the disposition to focus on positive or negative aspects of risks also affects actual risk taking behavior. In a student sample and in a representative sample, we find that dispositional optimism is related to risk taking behavior. In the student sample it predicts lottery choices and in the representative sample investing in the stock market and being self-employed.

In our second study, we have investigated how our results relate to RDU theory, which explicitly models the effect of optimism on risk taking. Being a descriptive theory of choice, RDU is agnostic regarding the psychological processes behind decision weights. The psychological determinants of decision weights can be either related to misperception/distortion of probabilities or to differential focus on outcomes. These two psychological processes may well be distinct as someone could be directing their attention on one of the outcomes while still having a perfect understanding of the probability associated with that outcome. The correlation between dispositional optimism and the parameter governing the elevation of the probability weighting function suggests that at least part of the psychological foundation of decision weights may be related to focusing.

A different theory, which we have not considered, but that can be conceptually related to our findings is the theory of salience proposed by Bordalo et al. (2012). Similarly to them and previous psychological research, we interpret focus or salience as “the phenomenon that when one’s attention is differentially directed to one portion of the environment rather than to others, the information contained in that portion will receive disproportionate weighting in subsequent judgments (Taylor & Thompson, 1982)”. In the theory of Bordalo et al. (2012), one outcome in a lottery becomes salient in comparison with other lotteries in the choice set, i.e., salience arises from the relative comparison of the size of the outcomes. Our findings deviate from their theory in two main respects. First, salience of outcomes is not evaluated relative to other lotteries but with respect to other outcomes within the same lottery. Second, people will display heterogeneity in the degree to which they focus on the positive or negative outcomes of risky prospects. Hence, while in Bordalo et al. (2012) there is no room for heterogeneity across individuals in the salience of a given lottery, our notion uncovers the heterogeneity that may exist in the weights given by different people to the upside and downside of risky prospects.

Finally, we have linked optimism to process data related to focusing such as attention and memory. In particular, optimists spend more time observing the high outcome of a lottery and end up taking more risk while pessimists do the opposite. Also, optimists tend to remember more vividly a scenario in which they had a positive outcome compared to one where they experienced a negative one. This is remarkable as the outcomes in the memory task were only hypothetical. This confirms that the psychological link between optimism and risk taking seem to be based mainly on the differential focus people devote to outcomes.

Overall, our results shed light on the psychology of the relation between optimism and risk taking and can inform economic theory on the underlying psychological determinants of decision under risk. Our results are also important from a policy perspective. Attempts to align the choices of decision makers (for example managers or politicians) with those of a rational risk neutral decision maker may turn out ineffective if these attempts target probability perception or distortion. For example, attempts to reduce overweighting/underweighting of probabilities may not lead to the desired results if behavior in fact stems from focusing on outcomes. In this respect, one important question which we leave for future research is whether focusing can be nudged in order to obtain the desired amount of risk taking in firms and organizations.

Notes

Arslan et al. (2020) provide insights into how people know their risk preferences.

These questions were only asked in week 3 to avoid that responses to the general risk question would be distorted by asking the focus questions before and thereby potentially priming respondents.

All questions are translated from German.

Not all free-form answers were classifiable along the dimensions of positive/negative valence and stake size. This happens in case the two coders do not agree on the relevant category or when they judge the answers as not classifiable in any of the categories. The percentage of non-classifiable answers is 42% for positive/negative valence, 50% for stake size, 56% for stake size gains, and 62% for stake size losses (see Table A3 in the online appendix for details).

We use ordinary least squares regressions throughout the paper for their ease of interpretation. An issue that arises using OLS with variables that were elicited on a Likert scale is that ordinal variables are treated as having cardinal significance. To avoid this issue, throughout the paper we transform both the general risk question and the focus questions into indicator variables that take value 1 if the response is equal or above the median and 0 otherwise. Results of OLS regressions using ordinal variables can be found in a working paper version of the current study (Dohmen et al., 2022). An alternative strategy to deal with ordinal variables is to use ordered probit regressions which we do in Section A.9 in the online appendix (see Tables A19-A23). All results are robust to these alternative models.

The Spearman rank correlation between the general risk question and “Free form - neg/pos” is positive and significant (\(\rho = .265\), \(p < .001\)), while this is not the case for “Free form - stake size” (\(\rho =-.024\), \(p = .652\)), “Free form - stake size (gains)” (\(\rho =-.003\), \(p = .949\)) and “Free form - stake size (losses)” (\(\rho =.043\), \(p = .420\)).

In personality psychology, dispositional optimism is viewed as a distinct trait that cannot be readily mapped into the Big Five inventory, even though there is a partial overlap between dispositional optimism and some dimensions of the Big Five (in particular agreeableness and extraversion; see Carver and Scheier (2014)). In our setup, optimism seems ex-ante an aspect of personality that can be used as a reliable proxy people’s disposition to focus on favorable or unfavorable outcomes of risk taking. The models reported in Tables A9 to A12 confirm this.

We rely on optimism rather than its manifestation in the form of focusing on good or bad sides of risk to ensure comparability between both samples as data on focusing are clearly not available in the representative dataset. For the data from our experiment a more direct test of the relationship between focusing and risk taking behavior using “Risk - neg/pos” is also possible and yields virtually identical results (see Table A18).

We control for gender, age, and height, which have been shown to be related to risk taking in the previous literature (Dohmen et al., 2011) We also control for parents’ education (Abitur mother and Abitur father) rather than own education to avoid reverse causality problems. These variables are equal to 1 if a parent has “Abitur” or “Fachabitur”, high school degrees that are awarded after 12 or 13 years of schooling and that grant access to (specific types of) university education. Further controls are logarithmic household wealth, logarithmic household debt, and logarithmic net household income. We also control for the number of adults (defined as older than 17) in the household in the stock-holding regression.

See also Bruhin et al. (2010), Epper et al. (2011), and Murad et al. (2016) for applications of the same elicitation procedure. In particular, the tables and the estimation procedures we use are a one-to-one replication of Murad et al. (2016). We thank the authors for providing their instructions and estimation code.

We frame the online survey as part of the experiment. To incentivize participation, at the end of the lab session we distributed a lottery ticket which is valid only if the corresponding participant fills in the online survey. The lottery prize is 50 € but there are no performance-dependent incentives for the online survey. Due to this mechanism, attrition is very low (178 subjects out of 182 complete the online survey). To track subjects while still preserving anonymity we used subject IDs that could not be traced to subjects’ names to match their responses across weeks. Of the 178 participants, 175 could unequivocally be matched with the data from the laboratory.

Another possible way to investigate this mechanism rather than looking at process data would have been to use priming techniques to show that if people are primed with positive outcomes they tend to take more risk than when primed with negative outcomes. Evidence along these lines is offered by Cohn et al. (2015) who show that financial professionals primed with a stock market boom tend to take more risk than the ones primed with a bust.

References

Angelini, V., & Cavapozzi, D. (2017). Dispositional optimism and stock investments. Journal of Economic Psychology, 59, 113–128.

Arslan, R. C., Brümmer, M., Dohmen, T., Drewelies, J., Hertwig, R., & Wagner, G. G. (2020). How people know their risk preference. Scientific Reports, 10, 1–14.

Barber, B. M., & Odean, T. (2001). Boys will be boys: Gender, overconfidence, and common stock investment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 261–292.

Beauchamp, J. P., Cesarini, D., & Johannesson, M. (2017). The psychometric and empirical properties of measures of risk preferences. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 54, 203–237.

Bock, O., Baetge, I., & Nicklisch, A. (2014). hroot: Hamburg registration and organization online tool. European Economic Review, 71, 117–120.

Bonin, H., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2007). Cross-sectional earnings risk and occupational sorting: The role of risk attitudes. Labour Economics, 14, 926–937.

Bordalo, P., Gennaioli, N., & Shleifer, A. (2012). Salience theory of choice under risk. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 127, 1243–1285.

Brandts, J., & Cooper, D. J. (2007). It’s what you say, not what you pay: An experimental study of manager-employee relationships in overcoming coordination failure. Journal of the European Economic Association, 5, 1223–1268.

Bruhin, A., Fehr-Duda, H., & Epper, T. (2010). Risk and rationality: Uncovering heterogeneity in probability distortion. Econometrica, 78, 1375–1412.

Buser, T., Niederle, M., & Oosterbeek, H. (2014). Gender, competitiveness, and career choices. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129, 1409–1447.

Caliendo, M., Fossen, F. M., & Kritikos, A. S. (2009). Risk attitudes of nascent entrepreneurs-new evidence from an experimentally validated survey. Small Business Economics, 32, 153–167.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2014). Dispositional optimism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 18, 293–299.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 879–889.

Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2012). Strong evidence for gender differences in risk taking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83, 50–58.

Cohn, A., Engelmann, J., Fehr, E., & Maréchal, M. A. (2015). Evidence for countercyclical risk aversion: An experiment with financial professionals. American Economic Review, 105, 860–885.

Crosetto, P., & Filippin, A. (2013). The “bomb’’ risk elicitation task. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 47, 31–65.

Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47, 448–474.

Diecidue, E., & Wakker, P. P. (2001). On the intuition of rank-dependent utility. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 23, 281–298.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Golsteyn, B. H., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2017). Risk attitudes across the life course. The Economic Journal, 127, 95–116.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2018). On the relationship between cognitive ability and risk preference. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 32, 115–134.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants, and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9, 522–550.

Dohmen, T., Quercia, S., & Willrodt, J. (2022). On the psychology of the relation between optimism and risk taking. IZA Discussion Paper Series (15763).

Dohmen, T., Quercia, S., & Willrodt, J. (2023). A note on salience of own preferences and the consensus effect. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 209, 15-21.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Men, women and risk aversion: Experimental evidence. Handbook of Experimental Economics Results, 1, 1061–1073.

Epper, T., Fehr-Duda, H., & Bruhin, A. (2011). Viewing the future through a warped lens: Why uncertainty generates hyperbolic discounting. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 43, 169–203.

Falk, A., Becker, A., Dohmen, T., Enke, B., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2018). Global evidence on economic preferences. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133, 1645–1692.

Fehr-Duda, H., De Gennaro, M., & Schubert, R. (2006). Gender, financial risk, and probability weights. Theory and Decision, 60, 283–313.

Felton, J., Gibson, B., & Sanbonmatsu, D. M. (2003). Preference for risk in investing as a function of trait optimism and gender. The Journal of Behavioral Finance, 4, 33–40.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10, 171–178.

Gibson, B., & Sanbonmatsu, D. M. (2004). Optimism, pessimism, and gambling: The downside of optimism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 149–160.

Goldstein, W. M., & Einhorn, H. J. (1987). Expression theory and the preference reversal phenomena. Psychological Review, 94, 236.

Grund, C., & Sliwka, D. (2010). Evidence on performance pay and risk aversion. Economics Letters, 106, 8–11.

Herzberg, P. Y., Glaesmer, H., & Hoyer, J. (2006). Separating optimism and pessimism: A robust psychometric analysis of the revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R). Psychological Assessment, 18, 433.

Jacobsen, B., Lee, J. B., Marquering, W., & Zhang, C. Y. (2014). Gender differences in optimism and asset allocation. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 107, 630–651.

Jaeger, D. A., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., & Bonin, H. (2010). Direct evidence on risk attitudes and migration. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 92, 684–689.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 263–291.

Kemper, C. J., Wassermann, M., Hoppe, A., Beierlein, C., & Rammstedt, B. (2015). Measuring dispositional optimism in large-scale studies. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 33, 403–408.

Lattimore, P. K., Baker, J. R., & Witte, A. D. (1992). The influence of probability on risky choice: A parametric examination. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 17, 377–400.

Lönnqvist, J. E., Verkasalo, M., Walkowitz, G., & Wichardt, P. C. (2015). Measuring individual risk attitudes in the lab: Task or ask? An empirical comparison. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 119, 254–266.

Murad, Z., Sefton, M., & Starmer, C. (2016). How do risk attitudes affect measured confidence? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 52, 21–46.

Nigel, N., Soane, E., Fenton-O’Creevy, M., & Willman, P. (2005). Personality and domain-specific risk taking. Journal of Risk Research, 8, 157–176.

Puri, M., & Robinson, D. T. (2007). Optimism and economic choice. Journal of Financial Economics, 86, 71–99.

Quiggin, J. (1982). A theory of anticipated utility. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3, 323–343.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063.

Schupp, J., & Gerlitz, J. Y. (2008). BFI-S: Big Five Inventory-SOEP (p. 12). In Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen: ZIS Version, vol.

Starmer, C. (2000). Developments in non-expected utility theory: The hunt for a descriptive theory of choice under risk. Journal of Economic Literature, 38, 332–382.

Taylor, S., & Thompson, S. (1982). Stalking the elusive vividness effect. Psychological Review, 89, 155–181.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5, 297–323.

Vieider, F. M., Lefebvre, M., Bouchouicha, R., Chmura, T., Hakimov, R., Krawczyk, M., & Martinsson, P. (2015). Common components of risk and uncertainty attitudes across contexts and domains: Evidence from 30 countries. Journal of the European Economic Association, 13, 421–452.

Wagner, G. G., Frick, J. R., & Schupp, J. (2007). The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) - evolution, scope and enhancements. SOEPpapers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research: No. 1.

Weinstock, E., & Sonsino, D. (2014). Are risk-seekers more optimistic? Non-parametric approach. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 108, 236–251.

Acknowledgements

We thank Robin Cubitt, Dirk Engelmann, Armin Falk, Felix Kuebler, Zahra Murad, and Peter Wakker as well the audience at the EEA-ESEM Cologne 2018 for helpful comments and suggestions. We also thank anonymous reviewers and the editor for valuable comments. Carina Lenze, Luis Wardenbach, Leon Sieverding and Maximilian Blesch provided excellent research assistance.

Funding

Funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) through CRC TR 224 (Project A05) and under Germany’s Excellence Strategy – EXC 2126/1– 390838866 is gratefully acknowledged. Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Verona within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dohmen, T., Quercia, S. & Willrodt, J. On the psychology of the relation between optimism and risk taking. J Risk Uncertain 67, 193–214 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-023-09409-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-023-09409-z