Abstract

Estonian students achieved high scores in the latest Programme for International Student Assessment surveys. At the same time, there needs to be more knowledge about the teachers guiding these students, as this could provide insights into effective teaching methods that can be replicated in other educational contexts. According to the Teaching and Learning International Survey, Estonian teachers' average age is among the highest in the world, and the shortage of young, qualified mathematics teachers is well-documented. The present study aimed to map the motivating and demotivating factors for mathematics teachers to continue working in this profession. The effective sample comprised 164 Estonian mathematics teachers who responded to items regarding self-efficacy and job satisfaction and open-ended questions about motivating and demotivating factors regarding their work. The results showed that students, salary and vacation, and job environment are both motivating and demotivating for mathematics teachers. On the one hand, helping the students to succeed (and witnessing the progress), satisfying salaries and a good job climate motivate the teachers. And at the same time, students' low motivation, poor salary, and straining work conditions (e.g., very high workload) serve as demotivating factors. We showed that mathematics teachers' work experience is an essential factor to be considered when thinking about motivating and demotivating factors for teachers, as well as their self-efficacy and job satisfaction. The reasons, possible impact, and potential interventions on an educational policy level are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Learning and understanding mathematics is important for students of all ages, as it relates directly to acquiring the basic competencies needed for participating in human culture (Räsänen et al., 2019). Furthermore, mathematical thinking is associated with understanding how knowledge is formed (Rozgonjuk et al., 2022), and the role of mathematics in the vastly increasing technological world is highly relevant (Gravemeijer et al., 2017).

To this end, one cannot overstate the essential impact of mathematics teachers. They shape the development of students' mathematical thinking and skills, as well as motivation and enthusiasm for learning mathematics. The present work aims to investigate the motivating, demotivating, and contributing factors for teaching mathematics to Estonian students. In the current section we provide a review of motivation-related factors among teachers: first for teachers in general and then for mathematics teachers. Also, we give an overview of the Estonian educational landscape regarding mathematics teaching and why the knowledge from the present study could be helpful in other settings.

Factors related to teaching motivation: a more general perspective

In the following section, we will contextualize our study of mathematics teachers within the broader sphere of teaching by presenting an overview of general motivating factors, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction among teachers. Understanding the motivating factors, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction in general teaching can shed light on similar dynamics among mathematics teachers. This insight is crucial for improving mathematics teacher effectiveness, promoting their retention and professional development, and enhancing teacher-student interactions. Furthermore, gaining knowledge about the specific motivating and demotivating factors among mathematics teachers could provide valuable information for guiding educational policies and reform initiatives tailored to this specific group.

The average age of teachers has been shown to be between 36 and 50 years in OECD countries (OECD, 2019, p. 84). Georgia, Lithuania, Estonia, Portugal, and Bulgaria stand out as countries with the highest average age of teachers, which is around 50 years, while the OECD’s average is 44 years. Teachers’ higher age may be beneficial, as experienced teachers could support their younger colleagues by sharing their experience. On the other hand, the high average age of teachers could be a state-level indicator of potential staff shortage followed by a large number of retiring teachers. Therefore, teachers’ motivation to continue their work is essential for the functioning of the educational system.

Bretz and Judge (1994) have stressed the importance of how individuals fit into their organization. In general, better fit between employees and organization leads to higher degree of job satisfaction. According to the theory of work adjustment, both individuals as well as environments have requirements towards each other, and successful work relations are based on adjustments by both individuals and work environments (Dawis, 2002). Some indicators have been found to help in adapting to the work environment, for instance it has been shown that a person's sense of self-efficacy plays a role in fitting with work environment (Jimmieson et al., 2004).

It is essential to understand how teachers perceive their work environment and working conditions, which factors motivate them to continue teaching, and which part of their working environment they see as demotivating. For example, low motivation to teach may be caused by stressful work conditions, especially at the start of a teaching career, where teachers tend to experience a lot of stress (McCarthy et al., 2020). There can be many stressors at workplace, and they may be systemic (e.g., broader educational policies, such as curriculum), organizational (e.g., workload, leadership, technology, resources), relational (e.g., parental expectations, disruptive and disengaged students), as well as intrapersonal (e.g., work-life balance, health; Carroll et al., 2021). Understanding the potential external and internal factors that may play a role in stress experienced by teachers can also provide insights into what (de)motivates educators to give their best at work (Carroll et al., 2021). Previous research has demonstrated that experiencing constant stress over time decreases the desire to continue working in the educational system, and significantly decreased motivation to teach typically results in burnout (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2020). According to a recent systematic review study (Madigan & Kim, 2021), teacher burnout is associated with poorer academic outcomes and lower motivation in their students.

In her literature overview, Sinclair (2008) has outlined ten factors highly relevant to teacher motivation: students, altruism, the influence of others, perceived benefits, calling to teach, love of teaching the subject, nature of teaching work, the desire for a career change, perceived ease of teaching, the status of teaching. Additionally, for teachers, the feeling that their students are inspired to learn is essential to be motivated to continue their teaching (Orsini et al., 2020).

Higher teaching motivation is associated with higher self-efficacy which is a protective factor against burnout (Karakus et al., 2021; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017). Self-efficacy is one's belief in one's ability to succeed in specific situations (Bandura, 1997). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs are “teachers’ individual beliefs about their abilities to perform specific teaching successfully and learning-related tasks within the context of their classrooms” (Dellinger et al., 2008, p. 751). A teacher's higher self-efficacy is associated with better outcomes for the teacher's job and their students' performance (Thoonen et al., 2011; Zee & Koomen, 2016). Additionally, teachers' high self-efficacy is also associated with higher job satisfaction (Toropova et al., 2021). It has also been demonstrated that teachers with higher self-efficacy and job satisfaction are less motivated to resign (Madigan & Kim, 2021; Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2017). Teachers’ desire to resign may be increased by higher emotional exhaustion and workload (Saks et al., 2021) or many workplace stressors (Kyriacou & Kunc, 2007).

One factor that is naturally related to teachers' continued employment is the length of teachers' work experience. Interestingly, Topchyan and Woehler (2021) found that the length of teaching experience does not affect teachers' job satisfaction or work engagement. On the other hand, it has been shown that teachers' self-efficacy increases with teachers' work experience over time, and beginning teachers tend to report the lowest self-efficacy (Chung & Chen, 2018). Concerning motivating and demotivating factors, it is essential to know if teachers with different work experience are motivated or demotivated to continue by the same factors.

Factors related to teaching motivation: findings in mathematics education

Kandemir and Gür (2009) interviewed several mathematics teachers and reported that these teachers were generally more motivated to teach mathematics because of their students, affinity towards mathematics, and the act of teaching itself. Moreover, studies such as that of Baier et al., (2019) have demonstrated the high relevance of intrinsic motivation, including passion for teaching, among mathematics teachers. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting that experience in mathematics teaching is associated with various motivating and demotivating factors. For instance, less-experienced mathematics teachers have reported higher levels of stress related to teaching activities, while more experienced mathematics teachers have found administrative work to be demotivating (Forgasz & Leder, 2006).

Just like teachers in general, the self-efficacy of mathematics teachers is also positively associated with their job satisfaction, mathematics achievements of their students (Chang, 2008; Perera & John, 2020), as well as the students' self-efficacy (Chang, 2008). Conversely, lower self-efficacy among mathematics teachers is linked to a poorer self-perception of mathematical ability among students and a higher perceived difficulty of tasks (Corkin et al., 2018; Fackler et al., 2021; Prewett & Whitney, 2021). When considering mathematics teachers' teaching experience, Peker and colleagues (2018) found that self-efficacy is lowest among less-experienced mathematics teachers.

Knowledge about mathematics teachers' job satisfaction in relation to work experience is relatively understudied. Furthermore, research focusing on more experienced teachers, including mathematics teachers, is lacking. Studies examining teachers, particularly mathematics teachers, often include samples with relatively short working experience or a lower average age. For example in a study about mathematics teachers’ self-efficacy by Peker et al. (2018), 59% of the sample consisted of teachers with teaching experience ranging from 1 to 9 years of service. A key finding of that study was that less-experienced teachers had the lowest self-efficacy among mathematics teachers. In another study by Perera and John (2020), the self-efficacy of mathematics teachers has been linked to improved student academic outcomes. Notably, the average work experience of the teachers in that study’s sample was 15 years.

In some studies, the average age of mathematics teachers is relatively low. For instance, a study on teachers' self-efficacy by Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (2001) used two samples of in-service teachers with average ages of 31.6 and 33.5, respectively. Unfortunately, some studies, like the one by Thoonen et al. (2011), do not report the average age or length of teaching experience of the teachers. Given the aging of teachers and the potential long-term staff shortage problems in many countries, research investigating the links between teaching motivation and work experience is needed.

Understanding motivating and demotivating factors for mathematics teacher retention: implications for sustainability and policy

As mentioned earlier in this work, the average age of Estonian mathematics teachers is relatively high (i.e., every fifth mathematics teacher is over 60 years old; Mets & Viia, 2018). According to the TALIS survey (Taimalu et al., 2020), as many as 41% of teachers in Estonia under the age of 35 plan to work as a teacher for only five more years. In contrast, the corresponding average indicator for OECD is 16%. Furthermore, Estonia also has a shortage of qualified mathematics teachers: almost 30% of Estonian mathematics teachers have a qualification below a Master's degree, and 6.5% of mathematics teachers have a qualification below a Bachelor's degree (Mets & Viia, 2018). The constellation of these circumstances suggests that Estonia may potentially experience a critical shortage of trained mathematics teachers in the near future. Although the present work focuses on the Estonian context, there is reason to believe that several other countries may share a similar future scenario. According to (OECD, 2019), Italy, Portugal, Hungary, Lithuania, Latvia, Georgia, and Bulgaria seem to also have an aging mathematics teacher population with a low number of potential successors.

The present study's findings on the motivating factors, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction of mathematics teachers, based on their length of work experience, can provide valuable insights not only for countries experiencing a shortage of mathematics teachers but also for those without such issues. The study's generalizable insights can inform professional development programs aimed at enhancing teacher efficacy and job satisfaction, ultimately contributing to improved academic outcomes. Moreover, the study's results can inform policy decisions aimed at addressing broader issues in education, such as mathematics teacher retention and support.

The sustainability of mathematics teacher training requires a better understanding of how to keep motivated teachers in their jobs—as well as what could be modified to reduce the strain experienced by mathematics teachers that may lead them to resign from teaching. Therefore, mapping motivating and demotivating factors concerning mathematics teachers' continuing their work could provide valuable insights for describing the status quo and as a necessary input to combat mathematics teacher shortage. To decrease the likelihood of mathematics teacher attrition, it should be helpful to increase motivating and decrease the role of demotivating factors.

Factors that either motivate or demotivate mathematics teachers to continue their work can be individual or structural. Individual factors refer to characteristics and experiences of the teacher themselves, such as their job satisfaction, efficacy beliefs, work experience, feeling of burnout. Structural factors, on the other hand, refer to broader conditions and policies that impact the teaching profession. Some examples of structural factors include working conditions, salary and benefits, professional development, societal perceptions. Overall, understanding both individual and structural factors can help policymakers and educators develop strategies to attract and retain high-quality mathematics teachers.

Aims of the present study

As described above, Estonia and other countries have problems with the shortage of qualified mathematics teachers and senior teaching staff. To retain and support working teachers, it is essential to understand the factors in their work that motivate them to continue teaching—and which factors might influence their decision to leave. Although there is some research in this domain, the findings typically rely on interviews with a small number of study participants (Forgasz & Leder, 2006; Kandemir & Gür, 2009). On the other hand, there are quantitative studies with larger samples—but they have not typically specifically focused on mathematics teachers (Sinclair, 2008; Watt & Richardson, 2007). Additionally, there is relatively little research gauging the differential motivational factors based on mathematics teachers’ experience level. This is also the case in research focusing on the interplay between self-efficacy and job satisfaction in relation to (de)motivating factors. In many countries where the average age of mathematics teachers presents the potential threat of qualified teaching staff shortage, it is crucial to investigate the relationships between teacher self-efficacy, job satisfaction, motivating factors, and the length of working experience.

The aim of the current work is to (a) describe the factors that motivate or demotivate mathematics teachers to continue their jobs, (b) clarify if self-efficacy and job satisfaction are lower for beginning mathematics teachers than for more experienced ones, and (c) investigate the associations between the following factors: mathematics teachers’ motivating and demotivating factors, self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and work experience.

Methods

Sample and procedure

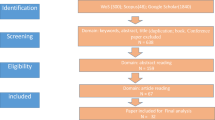

Estonian mathematics teachers were invited to take part in an online survey asking about their teaching and experience as teachers. The link to the survey was distributed through mailing lists that gather Estonian mathematics teachers from different counties; therefore, convenience sampling was used. The participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, and the participants had the possibility to terminate their study participation at any time. Electronic informed consent was obtained from study participants.

The initial sample comprised 181 mathematics teachers (age M = 49.17, SD = 12.28; 159 women, 21 men, one participant did not specify their gender). Some participants did not respond to all scales and questions; we excluded those participants who had missing values in self-efficacy or job satisfaction measures. This resulted in the sample size of 164 (age M = 48.86, SD = 11.98; 145 (88.4%) women, 18 men, one participant did not specify their gender). As the average age of Estonian teachers in general is 49.2 and 83.8% of teachers are female (Taimalu et al., 2019), the sample of the study is representative for Estonian teachers. As of the time of the survey, a total of 2,662 mathematics teachers worked in Estonia and, according to the TALIS survey (Taimalu et al., 2019), 6% of them had secondary education (or education equivalent to secondary education), 22% had a Bachelor’s degree, 71% had Master’s degree, and 0.8% had Doctoral degree. Within the sample, one teacher (0.61%) had secondary education, 24 (14.63%) had a Bachelor's degree, 138 (83.15%) had obtained a Master's degree, and one (0.61%) had a Doctoral degree. Among the participants, 84 (51%) mathematics teachers reported teaching at the primary education level (grades 5–9), while 80 (49%) reported teaching at the secondary education level (grades 10–12). In general, 77% of teachers in Estonia work in primary education, and 17% of teachers work at the secondary education level. Therefore, although the sample was somewhat biased towards teachers with a Master’s degree and those teaching at the secondary education level, it more or less reflects the population of mathematics teachers in the country.

Measures

The teachers were surveyed about their socio-demographics (age, gender), the length of teaching, as well as job-related self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and aspects of their job that would motivate (or demotivate) them to continue teaching.

Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy was assessed with an 11-item questionnaire where responses ranged from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree. The items regarded more general, as well as more mathematics-specific statements regarding teaching. Example items are: "I know how to compose a lesson", "I know how to handle difficult students", and "I can motivate a student who has no interest in mathematics". Both Cronbach's α = 0.88 and McDonald's ωtotal = 0.88 indicate that the scale has a good internal consistency. The questionnaire based on Ohio State Teacher Efficacy Scale (OSTES; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001), which includes 24 items, was shortened and adapted into Estonian to fit for mathematics teachers (Silm, 2016).

Job satisfaction

Job satisfaction was loosely based on the job satisfaction scale by (Brayfield & Rothe, 1951) and was adapted to Estonian for the current project. The job satisfaction scale used in the present study included four items on a five-point scale with responses ranging from 1 = completely disagree to 5 = completely agree. The items were: (1) "I am satisfied with the choice of my profession", (2) "My current job brings me satisfaction", (3) "I can handle stressful situations at work", and (4) "I go to work with a good feeling". The internal consistency of this scale was good, with Cronbach's α = 0.86 and McDonald's ωtotal = 0.87. A summed score was used as a measure of job satisfaction.

Motivating and demotivating factors

Motivating and demotivating factors were extracted from the teachers' responses from open-ended questions. Specifically, two questions were used: (1) "What motivates you to continue teaching?" and (2) "What decreases your motivation to continue teaching?" The free-text responses were then categorized into specific motivating and demotivating factors. Since these categories were not mutually exclusive, each motivating and de-motivating factor for each participant either received a "1" or "0" as a value, marking that the respondent outlined this factor or not, respectively. This categorization was performed by the authors of the current work whose combined experience includes research and practical work in (mathematics) education and psychology. The inter-rater reliability (calculated via intraclass correlations coefficients; ICCs) for motivating and demotivating factors categorization was 0.78-0.99 (please see Supplementary Table 1 for detailed results). ICC-s between 0.75 and 0.90 indicate good reliability, and values over 0.90 show excellent reliability for different raters’ categorizations (Koo & Li, 2016).

As a result of this coding, the responses were categorized into five motivating and six demotivating factors. The motivating factors were:

-

(M1) Students: joy of teaching the students.

-

(M2) Salary and vacation: remuneration-related, rather instrumental aspects such as good salary, plenty of vacation time, etc.

-

(M3) Work environment: enjoying the work environment, good relationships with colleagues.

-

(M4) Sense of mission: wanting to change the teaching situation, the level of mathematics in Estonia, etc.

-

(M5) Interest in the profession: interest in the job, mathematics, and self-improvement.

The six demotivating factors were the following:

-

(DM1) Students: the behavior or learning attitude is demotivating.

-

(DM2) Salary and vacation: the rather instrumental, remuneration-related aspects (insufficient/low salary, little vacation time, etc.).

-

(DM3) Work environment: e.g., work conditions are not good, too high workload, toxic social environment.

-

(DM4) Health and/or age: poor health and/or aging as reasons for not continuing teaching.

-

(DM5) Parents: the behavior and attitudes of parents, conflicts with parents.

-

(DM6) Societal aspects: poor attitude towards teachers in the society, major changes in teaching, curricular structure, etc.

Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using R software version 4.1.3 (R Core Team, 2022). The internal consistency statistics for scales as well as ICCs were computed with psych package v 2.1.9 (Revelle, 2021). The ggplot2 package v 3.3.5 (Wickham, 2016) was used for frequency plots. Spearman correlation analysis was used to investigate the associations between self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and age. Chi-square tests from R’s base package were used to compare the proportions of teachers with different work experience in motivating and demotivating factors responses. One-way analyses of variance (with Tukey post-hoc tests) were performed to investigate the differences in self-efficacy and job satisfaction in groups of teachers based on work experience with the rstatix v 0.7.0 (Kassambara, 2021) package. We also computed a series of logistic regression models with the stats v 4.1.3 (R Core Team, 2022) where a given motivating or demotivating factor was the (binary) outcome variable, and participants' age, self-efficacy, and job satisfaction scores were used as predictors.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations

Table 1 includes the descriptive statistics and correlations for the key variables.

Teachers’ age is highly (positively) correlated with the length of their work experience, but not correlated with their job satisfaction or self-efficacy. Nevertheless, the length of work experience is correlated with both self-efficacy and job satisfaction. The effect sizes are small but statistically significant. Teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction are correlated positively with large effect size.

Factors motivating and demotivating mathematics teachers to continue working

In the next section we describe how frequently mathematics teachers reported different motivating and demotivating factors. At first, we describe the frequencies for all participants, and then give an overview of response frequencies categorized by work experience.

Figure 1 depicts the count and answering percentage of responses for each motivating and demotivating factor.

Count responses for motivating and demotivating factors. Notes. M1 = students; M2 = salary and vacation; M3 = work environment; M4 = sense of mission; M5 = interest in profession; DM1 = students; DM2 = salary and vacation; DM3 = work environment; DM4 = health and/or age; DM5 = parents; DM6 = societal aspects

As we see from Fig. 1, two factors motivate mathematics teachers more than the other three factors: over 60 (38%) teachers have answered that they are motivated by students and 59 (36%) teachers have answered that interest in the profession motivates them to continue working as a teacher (many teachers have written that they enjoy teaching mathematics because they love the discipline). Sense of mission was the factor motivating relatively few teachers (8%). Regarding demotivating factors, three of them stand out more: students, work environment, and societal aspects. Parents was the factor that the smallest number (9%) of teachers answered to demotivating them.

Based on the results from former studies, we divided participating teachers into five groups based on the length of their work experience. The largest group, consisting of 62 teachers, comprised senior teachers with over 30 years of work experience. The longest reported work experience in this group was 54 years. The smallest group was made up of teachers with five to nine years of experience. Additionally, the group of beginner teachers, with less than five years of experience, was relatively small with only 22 teachers.

As can be seen from Table 2, the proportions of choosing motivating and demotivating factors are quite different in groups of teachers with different work experience. Chi-square tests of independence were performed (please see Supplementary table 2 for detailed results) to examine the relations between groups based on work experience and motivating and demotivating factors. More specifically, of 11 chi-squared tests computed, five were statistically significant: namely, three motivating factors and two demotivating factors answering patterns were different for different teachers based on work experience. Only 23% of senior and 32% of beginning mathematics teachers said that students motivate to continue their work, while the proportions for this category within the 10–19- and 20–29-years work experience groups were 54% and 51%, respectively, χ2(4, 164) = 12.81, p = 0.012. The motivating factor sense of mission was more prevalent in less experienced (0–4 and 5–9 years) teacher groups, χ2(4, 164) = 16.56, p = 0.002. For the motivating factor interest in profession, more experienced teachers, reported this motivating factor more frequently, χ2(4, 164) = 9.95, p = 0.041. Specifically, only 14% of beginning mathematics teachers found that they have interest in the profession, in contrast to 47% of senior teachers.

Regarding demotivating factors, the work environment was more frequently demotivating for groups with 5–9 and 10–19 years of work experience than for the senior teachers, χ2(4, 164) = 14.12, p = 0.007. 31% of the senior teachers said that age and health are demotivating factors for them, while other groups reported this reason far less frequently (less than 9%). It is also important to note that the highest dissatisfaction with the salary and vacation was in the group with 5–9 years of work experience (31% marked salary as demotivating factor for them). It could be generally observed that dissatisfaction with salary was more prevalent in teachers with less work experience.

Teachers’ self-efficacy and job satisfaction differences based on their work experience

As can be seen in Table 3, average self-efficacy and job satisfaction are different for different groups based on work experience.

One-way ANOVAs were performed to compare the group differences in self-efficacy and job satisfaction between teachers with varying work experience.

The results showed that there were statistically significant differences (Supplementary Table 3) in job satisfaction with regards to the length of work experience, F(4, 159) = 3.256, p = 0.013. Tukey’s HSD test for multiple comparisons found that teachers with less than five years of teaching experience had lower job satisfaction (M = 14.86, SD = 3.48) than teachers with 30 + years of teaching experience (M = 17.00, SD = 2.27).

Additionally, the results of one-way ANOVA also showed that there were statistically significant group differences (based on work/teaching experience) between teachers in self-efficacy, F(4, 159) = 4.036, p = 0.004. Tukey’s HSD test showed that teachers with less than five years of teaching experience reported lower self-efficacy (M = 38.59, SD = 5.76) than all other groups.

Predicting motivating and demotivating factors

Next, we were interested if a mathematics teacher's self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and the length of work experience predicted a teacher's response to a given motivating or demotivating factors. For that, we ran a series of logistic regression models where the outcome variable was binary (yes/no) on whether the response was given. The results of these models are depicted in Tables 4 and 5.

Results of logistic regression analyses in Table 4 show that teachers’ self-efficacy is not a statistically significant predictor in any model, but teachers’ job satisfaction is statistically significant predictor in two models (for M2 and M5). Teachers’ job satisfaction score is associated with increase in the likelihood of reporting interest of profession as a motivating factor (OR = 1.365) and decrease the likelihood of reporting salary and vacation as a motivating factor (OR = 0.748). Teachers’ work experience was statistically significant predictor in three models: for predicting motivating factors students, sense of mission, and interest in profession. More experienced teachers reported that they are less likely motivated by students and sense of mission and more likely motivated by interest in profession.

Results of logistic regression analyses in Table 4 show that teachers’ self-efficacy is a statistically significant predictor only in one model: for predicting societal aspects as a demotivating factor for teachers. Job satisfaction predicts statistically significantly two demotivating factors: health and/or age, and societal aspects where teachers with higher job satisfaction have less likely answered that health and/or age, and societal factors are demotivating factors for them. Teachers’ work experience was statistically significant in four models: more experienced teachers reported less likely that students, salary, and work environment are demotivating factors for them. On the other hand, more experienced teachers have reported more frequently that health and/or age as demotivating factor for them.

Discussion

The present work aimed to understand what motivates mathematics teachers to continue their work and how teachers' self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and work experience are related to the motives for continuing/not continuing. More specifically, the study had three objectives: (a) to describe the motivating and demotivating factors for mathematics teachers to continue their job, (b) to clarify if self-efficacy and job satisfaction are lower for beginner mathematics teachers than for more experienced teachers, and (c) to investigate the associations between motivating and demotivating factors, mathematics teachers’ self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and work experience.

Some previous studies have investigated motivating and demotivating factors related to the work of mathematics teachers, but these studies have relied on a small samples of interviewees (Forgasz & Leder, 2006; Kandemir & Gür, 2009; Santagata & Lee, 2021). Based on these studies, mathematics teachers with varying length of work experience report different (de)motivating factors: early-career teachers feel more stressed about teaching, while more experienced mathematics teachers find administrative tasks demotivating. Mathematics teachers in general are motivated to teach mathematics due to their students, love of mathematics, and teaching. There are studies with larger samples focusing on teaching-related stressors and motivational aspects but these studies are not typically mathematics teachers specific. For instance, Sinclair (2008) outlined ten factors highly relevant to teacher motivation: students, altruism, the influence of others, perceived benefits, calling to teach, love of teaching the subject, nature of teaching work, the desire for a career change, perceived ease of teaching, the status of teaching. Finally, some studies regarding motivational factors are carried out with participants training to be mathematics teachers (Chang, 2008) and may not generalize to more experienced teachers to continue their work. The present work addressed these potential limitations by surveying more than a hundred mathematics teachers who form a representative sample of the population of Estonian mathematics teachers.

To achieve the aims of the present study, we combined quantitative and qualitative analyses. Regarding the qualitative part, we asked Estonian mathematics teachers to describe the factors that motivate and demotivate them to continue their work as teachers with free answers. The categorization of these free responses revealed five motivating categories and six demotivating categories. Of note, there was an overlap between stressor categories (or demotivating factors) described by Carroll et al. (2021) and motivating aspects mentioned by Sinclair (2008). Specifically, we showed that, like teachers in general (Kandemir & Gür, 2009; Sinclair, 2008), students and interest in teaching their subject motivate mathematics teachers as well.

In our study, students were mentioned by mathematics teachers as motivating and, at the same time, demotivating factor. Mathematics teachers who reported that students motivate them specified that working with motivated students who follow the taught materials and study joyfully is excellent. Since a major part of a teacher’s work involves communication with students, it is unsurprising that they mentioned students as both motivating and demotivating factors for continuing their work as a mathematics teacher. However, it is alarming that students were often mentioned (27%) as a demotivating factor by mathematics teachers. They specified that working with misbehaving or unmotivated students is challenging.

It has been found in previous work that good communication skills (Kooloos et al., 2022) as well as skills for fostering at-risk students (Prediger et al., 2022) are needed for being a good mathematics teacher. Mathematics teachers should consider teaching methods to foster their students' motivation to learn mathematics. For example, research has shown that when students are given more autonomy and freedom to make decisions in their mathematics lessons, their motivation to learn the subject can increase (León et al., 2015). Using computer game-based learning is also an opportunity to increase students' motivation to learn mathematics (Partovi & Razavi, 2019). Of note, it is also crucial for teachers to remember that there is an optimal duration for students' use of ICT that correlates with beneficial outcomes (Przybylski & Weinstein, 2017; Rozgonjuk et al., 2021).

Our study results indicate that student successes serve as a motivating factor for mathematics teachers, while challenges with students can demotivate them. Therefore, working with improving the students’ motivation to learn mathematics may help to increase the motivation (and likely also job satisfaction) of mathematics teachers. Because the acquisition of mathematical knowledge involves a creative process, especially in the context of problem-solving, introducing creative approaches in the mathematics classroom could improve the mathematics attitudes as well as the performance of students. Consequently, in addressing students' low motivation to learn mathematics, it is important for teachers to possess techniques that enhance creativity and promote a creative approach to problem-solving exercises (Mróz & Ocetkiewicz, 2021). However, this suggestion warrants subsequent research and is not within the scope of the present study.

Interestingly, societal aspects were reported as the most frequently demotivating factor among mathematics teachers. On several occasions, these teachers mentioned a relatively poor attitude towards their profession by society. Additionally, some cited significant changes in teaching and mathematics curricula as contributing factors to their demotivation to teach mathematics. Societal aspects are somewhat similar to systemic stressors discussed in previous work (Carroll et al., 2021). A study in Croatia reported that mathematics teachers are overwhelmed with work, and additionally, they know that the public does not understand their workload at all (Boljat et al., 2021). This suggests that mathematics teachers may require additional training to adapt to changes in the educational system, but it also emphasizes the workload of mathematics teachers.

From a quantitative aspect, we analyzed the differences in mathematics teacher self-efficacy and job satisfaction between teachers' with different lengths of teaching experience. Our analysis revealed statistically significant differences in the self-efficacy and job satisfaction of mathematics teachers based on their work experience duration. Mathematics teachers who just started to teach (with less than five years of experience) reported the lowest self-efficacy compared to more experienced teachers. These results are coherent with findings by Peker et al. (2018) where self-efficacy of mathematics teachers was found to be the lowest among less-experienced teachers. Additionally, beginning mathematics teachers reported lower job satisfaction when compared to senior mathematics teachers. These findings slightly differ from Topchyan and Woehler (2021) study. Namely, they did not find a correlation between the length of teaching experience and teachers’ job satisfaction. This difference from the former study (carried out on with teachers in general) shows that more research on mathematics teachers' job satisfaction and work experience is needed.

Given the lower job satisfaction and the higher reporting of demotivating factors, there is a need to focus on the self-efficacy of beginning mathematics teachers. For instance, it has been shown that more mastery teaching experiences throughout the teachers preparation program and support of master teachers in the early years can positively impact less-experienced teachers' self-efficacy (Tschannen-Moran & Johnson, 2011). To support early-career mathematics teachers, educators and policymakers can create supportive work environments that value and recognize teachers' efforts, as well as encourage regular reflection and feedback to identify areas of strength and improvement.

Our study compared the responses to motivating and demotivating factors of mathematics teachers with varying levels of experience. We found that beginning teachers reported intrinsic interest in the profession as a less motivating factor compared to their more experienced peers. Moreover, a quarter of beginning teachers cited low salary as a demotivating factor. In contrast, senior teachers reported being motivated by their interest in the profession and high job satisfaction, but 31% indicated that age and health were factors to consider when contemplating leaving their job. These findings highlight the need for educational policymakers to address both the issue of an aging mathematics teacher population and the challenges faced by beginning mathematics teachers. For senior teachers, policymakers could intervene by offering higher salaries, additional benefits, and opportunities for professional development to retain experienced educators. The TALIS report suggests that similar challenges exist in Georgia, Lithuania, Portugal, and Bulgaria (OECD, 2019, p. 80), indicating that these policy actions may be necessary in multiple countries.

For early-career teachers, policymakers can address the issue of low intrinsic motivation and salary by offering support, such as mentoring programs, opportunities for collaboration and feedback, and higher starting salaries. Additionally, policies such as loan forgiveness programs, scholarships, and stipends for education majors can help attract new teachers to the profession.

Finally, we predicted the likelihood of mathematics teachers' responses to different motivating and demotivating factors from self-efficacy, job satisfaction, and the length of working experience. Results of the logistic regression analyses showed that teachers with higher job satisfaction and shorter work experience were more likely to report the motivating effects of students. This finding is somewhat in line with previous research which has shown that students are one of the primary sources of a teacher's job satisfaction (Admiraal et al., 2019). At the same time, students as a demotivating factor was predicted by the shorter work experience of a mathematics teacher, whereas other factors were not statistically significant in the model. These results indicate that mathematics teacher training should involve education of building relationships with students and motivating them to be able to learn with motivation. The conclusion follows previous research by Watson and Marschall (2019), in which authors have postulated that integrating cognitive and social factors within the learning trajectory of teacher training is needed.

Mathematics teachers with higher job satisfaction were less likely to be motivated by salary, and teachers with more extended work experience were less likely to be demotivated by salary. The latter is coherent with the literature, as higher job satisfaction is associated with higher intrinsic motivation (Shah et al., 2012), so the extrinsic motivation (salary) is less critical.

Less experienced teachers pointed out the working environment as a demotivating factor. This result suggests that when recruiting (younger) mathematics teachers, the work environment (e.g., manageable workload) should be keenly considered. For instance, establish reasonable workload expectations (to ensure that teachers are not overwhelmed with heavy workload), provide support and access to professional development opportunities and mentorship programs. It is also important to foster a positive workplace culture, promoting collaboration and open communication.

Interest in the profession (interest in the job, mathematics, and self-improvement) was more often mentioned by more experienced teachers and respondents with higher job satisfaction. These associations were expected, as older age and job satisfaction has been shown to predict intrinsic interest in teaching in previous work (Sinclair, 2008).

It was surprising that teachers with higher self-efficacy reported more frequently that societal attitudes towards teacher work are demotivating for them. This finding requires further attention, as the mismatch between a teacher’s view of their teaching and their perception of how society thinks of them may affect their willingness to continue teaching. Health and/or age was mentioned more frequently and—as could be expected—more likely by more experienced teachers. Naturally, senior mathematics teachers answered more frequently that health and/or aging are reasons for them not to continue teaching. Given that there are many aging teachers, this is an obvious risk for the sustainability of mathematics teaching. Importantly, we showed that 15% of mathematics teachers think it would be better not to work in the future as a teacher. Some even specified that the academic year, when they responded to the survey would be the last one for them to teach mathematics at school. A previous study about mathematics teachers’ attitudes and stressors have similarly found that every sixth mathematics teacher wants to have another job and would not choose to be a teacher again (Boljat et al., 2021).

Reducing teacher attrition is essential for maintaining a stable and effective educational system. To achieve this, policymakers and school administrators should focus on increasing motivating factors and decreasing demotivating factors for mathematics teachers. Changing higher-level systematic aspects, such as salary or working conditions are important, but there are additional aspects to change in order to increase mathematics teachers’ motivation: to include the topics related to communication, inclusive education, and mental health in mathematics teacher education curricula. By equipping mathematics teachers with communication skills, they can better communicate with students, colleagues, and parents, leading to more effective teaching and improved outcomes for students. Inclusive education training can help mathematics teachers develop the skills and knowledge needed to create an inclusive learning environment that accommodates diverse learning needs and styles. Additionally, taking care of one's mental health is essential for teachers to maintain a healthy work-life balance and avoid burnout.

Conclusions

The main contribution of this work is that, to our knowledge, this is the first study investigating motivating and demotivating factors alongside self-efficacy and job satisfaction of mathematics teachers with different lengths of work experience. Our analyses revealed that early-career mathematics teachers (with less than five years of experience) reported the lowest self-efficacy and job satisfaction compared to more experienced teacher groups. Early-career mathematics teachers may benefit from support to increase their self-efficacy, and that such support could come in the form of mentors and in-service training courses focused on communication skills and motivating students. According to our survey, early-career mathematics teachers show less intrinsic interest in their profession, and about a quarter of them mentioned that salary could be a stronger motivator for them to continue teaching. We also found that senior mathematics teachers are motivated by their interest in the profession and job satisfaction, as well as salary. However, 31% of senior mathematics teachers mentioned age and health as factors which make them consider leaving the job. These differences highlight the need for tailored actions to support and retain both beginning and senior mathematics teachers.

The limitations of the study include cross-sectional study design and relying on self-report measures. Even though we computed logistic regression models, causality cannot be established with these data. For that, we would need to investigate mathematics teachers across a longer period. Second, it could be useful to include other, more objective measures to teachers' responses. Self-report measures are often used in research to gather subjective data directly from individuals about their own experiences, perceptions, and beliefs. While self-report measures are subject to biases and limitations, they provide valuable insights into how individuals interpret and experience their own lives, which may not be accessible through other means. In addition to open-ended questions about motivating and demotivating factors associated with work, it may be helpful to include other, i.e., multiple-choice items assessing these factors.

The study's sample represented mathematics teachers in Estonia quite well. However, when drawing conclusions, it is essential to remember that the sample was nevertheless somewhat biased towards more highly educated teachers, with a higher percentage holding a master's degree, and those teaching at the higher level of secondary education.

In conclusion, we aimed to provide insights into motivating and demotivating aspects of mathematics teachers' work. The most frequently outlined motivating factors were intrinsic: (motivating) students and interest in the profession; on the other hand, lower salary, poorer work environment, and systemic stressors were outlined as demotivating factors. Some of these aspects were associated with job satisfaction as well as a teacher's work experience. As the teaching population in mathematics ages and the recruitment of new teachers becomes increasingly challenging, the findings of this study can provide valuable insights for motivating both beginning and senior teachers.

Data availability

The data are made available upon scholarly request.

References

Admiraal, W., Veldman, I., Mainhard, T., & van Tartwijk, J. (2019). A typology of veteran teachers’ job satisfaction: Their relationships with their students and the nature of their work. Social Psychology of Education, 22(2), 337–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-018-09477-z

Baier, F., Decker, A.-T., Voss, T., Kleickmann, T., Klusmann, U., & Kunter, M. (2019). What makes a good teacher? The relative importance of mathematics teachers’ cognitive ability, personality, knowledge, beliefs, and motivation for instructional quality. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(4), 767–786. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12256

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Boljat, I., Bubica, N., & Matana, A. (2021). Stressors and burnout symptoms of math teachers in Croatian primary and high schools. EDULEARN21 Conference. https://www.bib.irb.hr/1135019/download/1135019.STRESSORS_AND_BURNOUT_SYMPTOMS_OF_MATH_TEACHERS.pdf

Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35(5), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055617

Bretz, R. D., & Judge, T. A. (1994). Person–organization fit and the theory of work adjustment: Implications for satisfaction, tenure, and career success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 44(1), 32–54.

Carroll, A., Flynn, L., O’Connor, E. S., Forrest, K., Bower, J., Fynes-Clinton, S., York, A., & Ziaei, M. (2021). In their words: Listening to teachers’ perceptions about stress in the workplace and how to address it. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 49(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2020.1789914

Chang, Y.-L. (2008). Examining relationships among elementary mathematics teachers’ efficacy and their students’ mathematics self-efficacy and achievement. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 4(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.12973/ejmste/75299

Chung, T.-Y., & Chen, Y.-L. (2018). Exchanging social support on online teacher groups: Relation to teacher self-efficacy. Telematics and Informatics, 35(5), 1542–1552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.03.022

Corkin, D. M., Ekmekci, A., & Parr, R. (2018). The effects of the school-work environment on mathematics teachers’ motivation for teaching: A self-determination theoretical perspective. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(6), 50–66.

Dawis, R. V. (2002). Person-environment-correspondence theory. In Career choice and development (4th ed., pp. 427–464). Career choice and development.

Dellinger, A. B., Bobbett, J. J., Olivier, D. F., & Ellett, C. D. (2008). Measuring teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs: Development and use of the TEBS-Self. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(3), 751–766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.02.010

Fackler, S., Malmberg, L.-E., & Sammons, P. (2021). An international perspective on teacher self-efficacy: Personal, structural and environmental factors. Teaching and Teacher Education, 99, 103255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103255

Forgasz, H., & Leder, G. (2006). Work patterns and stressors of experienced and novice mathematics teachers. Australian Mathematics Teacher, 62(3), 36–40.

Gravemeijer, K., Stephan, M., Julie, C., Lin, F.-L., & Ohtani, M. (2017). What mathematics education may prepare students for the society of the future? International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 15(S1), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-017-9814-6

Jimmieson, N. L., Terry, D. J., & Callan, V. J. (2004). A Longitudinal study of employee adaptation to organizational change: The role of change-related information and change-related self-efficacy. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9(1), 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.9.1.11

Kandemir, M. A., & Gür, H. (2009). What motivates mathematics teachers? Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 1(1), 969–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2009.01.172

Karakus, M., Ersozlu, Z., Usak, M., & Ocean, J. (2021). Self-efficacy, affective well-being, and intent-to-leave by science and mathematics teachers: A structural equation model. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 20(2), 237–251.

Kassambara, A. (2021). rstatix: Pipe-friendly framework for basic statistical tests (0.7.0). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rstatix

Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

Kooloos, C., Oolbekkink-Marchand, H., van Boven, S., Kaenders, R., & Heckman, G. (2022). Building on student mathematical thinking in whole-class discourse: Exploring teachers’ in-the-moment decision-making, interpretation, and underlying conceptions. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 25(4), 453–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-021-09499-z

Kyriacou, C., & Kunc, R. (2007). Beginning teachers’ expectations of teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8), 1246–1257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2006.06.002

León, J., Núñez, J. L., & Liew, J. (2015). Self-determination and STEM education: Effects of autonomy, motivation, and self-regulated learning on high school math achievement. Learning and Individual Differences, 43, 156–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.08.017

Madigan, D. J., & Kim, L. E. (2021). Does teacher burnout affect students? A systematic review of its association with academic achievement and student-reported outcomes. International Journal of Educational Research, 105, 101714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101714

McCarthy, C. J., Fitchett, P. G., Lambert, R. G., & Boyle, L. (2020). Stress vulnerability in the first year of teaching. Teaching Education, 31(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2019.1635108

Mets, U., & Viia, A. (2018). Tulevikuvaade tööjõu- ja oskuste vajadusele: Haridus ja teadus. Uuringu lühiaruanne. [Future perspective on work force and skills needs: Education and science. Brief report summary.]. SA Kutsekoda. https://oska.kutsekoda.ee/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/oska_HT_veeb.pdf

Mróz, A., & Ocetkiewicz, I. (2021). Creativity for sustainability: How do Polish teachers develop students’ creativity competence? Analysis of Research Results. Sustainability, 13(2), 571. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13020571

OECD. (2019). TALIS 2018 results (Volume I): Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/1d0bc92a-en

Orsini, C. A., Tricio, J. A., Segura, C., & Tapia, D. (2020). Exploring teachers’ motivation to teach: A multisite study on the associations with the work climate, students’ motivation, and teaching approaches. Journal of Dental Education, 84(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1002/jdd.12050

Partovi, T., & Razavi, M. R. (2019). The effect of game-based learning on academic achievement motivation of elementary school students. Learning and Motivation, 68, 101592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lmot.2019.101592

Peker, M., Erol, R., & Gultekin, M. (2018). Investigation of the teacher self-efficacy beliefs of math teachers. MOJES: Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 6(4), 1–11.

Perera, H. N., & John, J. E. (2020). Teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs for teaching math: Relations with teacher and student outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101842

Prediger, S., Dröse, J., Stahnke, R., & Ademmer, C. (2022). Teacher expertise for fostering at-risk students’ understanding of basic concepts: Conceptual model and evidence for growth. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-022-09538-3

Prewett, S. L., & Whitney, S. D. (2021). The relationship between teachers’ teaching self-efficacy and negative affect on eighth grade U.S. students’ reading and math achievement. Teacher Development, 25(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2020.1850514

Przybylski, A. K., & Weinstein, N. (2017). A large-scale test of the goldilocks hypothesis: Quantifying the relations between digital-screen use and the mental well-being of adolescents. Psychological Science, 28(2), 204–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797616678438

R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (4.2.0). R Core Team.

Räsänen, P., Laurillard, D., Käser, T., & von Aster, M. (2019). Perspectives to technology-enhanced learning and teaching in mathematical learning difficulties. In A. Fritz, V. G. Haase, & P. Räsänen (Eds.), International handbook of mathematical learning difficulties (pp. 733–754). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97148-3_42

Revelle, W. (2021). psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research (2.2.3). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

Rozgonjuk, D., Konstabel, K., Barker, K., Rannikmäe, M., & Täht, K. (2022). Epistemic beliefs in science, socio-economic status, and mathematics and science test results in lower secondary education: A multilevel perspective. Educational Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2022.2144143

Rozgonjuk, D., Täht, K., & Vassil, K. (2021). Internet use at and outside of school in relation to low- and high-stakes mathematics test scores across 3 years. International Journal of STEM Education, 8(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-021-00287-y

Saks, K., Hunt, P., Leijen, Ä., & Lepp, L. (2021). To stay or not to stay: An empirical model for predicting teacher persistence. British Journal of Educational Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2021.2004995

Santagata, R., & Lee, J. (2021). Mathematical knowledge for teaching and the mathematical quality of instruction: A study of novice elementary school teachers. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 24(1), 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-019-09447-y

Shah, M. J., Ur-Rehman, M., Akhtar, G., Zafar, H., & Riaz, A. (2012). Job satisfaction and motivation of teachers of public educational institutions. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(8), Article 8.

Silm, G. (2016). Õpetajate enesetõhususe küsimustiku eesti keelde adapteerimine. [The Estonian adaptation of the teacher self-efficacy scale].

Sinclair, C. (2008). Initial and changing student teacher motivation and commitment to teaching. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 36(2), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660801971658

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2017). Motivated for teaching? Associations with school goal structure, teacher self-efficacy, job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 152–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.006

Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2020). Teacher burnout: Relations between dimensions of burnout, perceived school context, job satisfaction and motivation for teaching. A longitudinal study. Teachers and Teaching, 26(7–8), Article 7–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2021.1913404

Taimalu, M., Uibu, K., Luik, P., & Leijen, Ä. (2019). Õpetajad ja koolijuhid elukestvate õppijatena. OECD rahvusvahelise õpetamise ja õppimise uuringu TALIS 2018 uuringu tulemused. http://hdl.handle.net/10062/70213

Taimalu, M., Uibu, K., Luik, P., Leijen, Ä., & Pedaste, M. (2020). Õpetajad ja koolijuhid väärtustatud professionaalidena. OECD rahvusvahelise õpetamise ja õppimise uuringu TALIS 2018 uuringu tulemused 2., 1−114. http://www.innove.ee/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/TALIS2_kujundatud.pdf

Thoonen, E. E. J., Sleegers, P. J. C., Oort, F. J., Peetsma, T. T. D., & Geijsel, F. P. (2011). How to improve teaching practices: The role of teacher motivation, organizational factors, and leadership practices. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(3), 496–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X11400185

Topchyan, R., & Woehler, C. (2021). Do teacher status, gender, and years of teaching experience impact job satisfaction and work engagement? Education and Urban Society, 53(2), 119–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124520926161

Toropova, A., Myrberg, E., & Johansson, S. (2021). Teacher job satisfaction: The importance of school working conditions and teacher characteristics. Educational Review, 73(1), 71–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2019.1705247

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. W. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00036-1

Tschannen-Moran, M., & Johnson, D. (2011). Exploring literacy teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs: Potential sources at play. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(4), 751–761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.005

Watson, S., & Marschall, G. (2019). How a trainee mathematics teacher develops teacher self-efficacy. Teacher Development, 23(4), Article 4. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2019.1633392

Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2007). Motivational factors influencing teaching as a career choice: Development and validation of the FIT-Choice Scale. The Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.75.3.167-202

Wickham, H. (2016). ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer.

Zee, M., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2016). Teacher self-efficacy and its effects on classroom processes, student academic adjustment, and teacher well-being: A synthesis of 40 years of research. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 981–1015. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315626801

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception or design of the work: A1, A4; Data collection: A1, A4; Data analysis and interpretation: A1, A4; Drafting the article: A1, A2, A3, A4; Critical revision of the article: A1, A2, A3, A4; Final approval of the version to be published: A1, A2, A3, A4.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Täht, K., Mikkor, K., Aaviste, G. et al. What motivates and demotivates Estonian mathematics teachers to continue teaching? The roles of self-efficacy, work satisfaction, and work experience. J Math Teacher Educ (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-023-09587-2

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10857-023-09587-2